Abstract

Luminescent gold(I) compounds have attracted intensive attention due to anticipated strong spin-orbit coupling (SOC) resulting from heavy atom effect of gold atoms. However, some mononuclear gold(I) compounds are barely satisfactory. Here, we unveil that low participation of gold in transition-related orbitals, caused by 6s-π symmetry mismatch, is the cause of low SOCs in monogold(I) compounds. To address this issue, we have developed a series of acceptor-donor organogold(I) luminescent compounds by incorporating a gem-digold moiety with various aryl donors. These compounds demonstrate wide-range tunable emission colors and impressive photoluminescence quantum yields of up to 78%, among the highest reported for polynuclear gold(I) compounds. We further reveal that the integration of the gem-digold moiety allows better interaction of gold 6s orbitals with aryl π orbitals, facilitates aryl-to-gold electron transfer, and reduces Pauli repulsion between digold units, finally engendering the formation of aurophilic interaction-based aggregates. Moreover, the strength of such intermolecular aurophilic interaction can be systematically regulated by the electron donor nature of aryl ligands. The formation of those aurophilic aggregates significantly enhances SOC from <10 to 239 cm−1 and mainly accounts for high-efficiency phosphorescent emission in solid state.

Subject terms: Excited states, Single-molecule fluorescence, Ligands

Some luminescent mononuclear gold(I) compounds have unexpectedly weak spin-orbit coupling, thus limiting their phosphorescence efficiency. Here, the authors develop a series of wide-range tunable acceptor-donor organodigold(I) luminescent compounds and investigate the relationship between structures, aurophilic interaction, and spin-orbit coupling.

Introduction

Luminescent gold(I) compounds have garnered significant attention due to their potential applications in phosphorescence1–5 and thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) materials6–10. The attraction arises from the anticipated high spin-orbit coupling (SOC) due to the heavy atom effect of gold(I) atoms11,12. Numerous polynuclear gold(I) complexes with excellent phosphorescence performance have been thus developed13–20. Nevertheless, some synthetically accessible mononuclear gold(I) complexes contrarily show sluggish phosphorescence emission rates and low photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY)21–28. In particular, phosphorescence emission rates of a few gold(I)-phosphine aryl and alkynyl coordination compounds remain unaffected upon the increase of gold atoms up to tetra- and penta-nuclear27–31. In general, the phosphorescence emission rate positively correlates with T1-S0 SOC11. Therefore, the presence of co-existing fluorescence emission and slow phosphorescence emission rates of these gold(I) complexes imply that SOCs in S1-T1 and T1-S0 transitions may not be as high as it seems. Although the recently reported mononuclear carbene-metal-amide gold(I) compounds show high PLQYs6,32–34, their fast reverse intersystem crossing is finally attributed to T1-S1 spin-vibronic interaction rather than SOC35–37. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to explore the influential factors to determine SOCs in Au(I) compounds and correlate its fine-tuning with the optimization of luminescent performance.

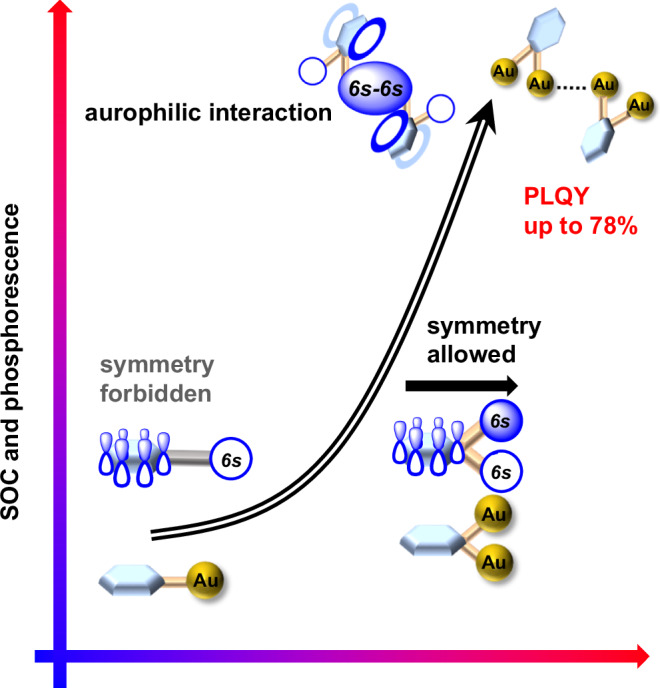

Previous theoretical investigations into excellent photo luminescent properties of cyclometalated Pt(II) complexes38 have discovered that high SOCs are closely related with significant charge transfer on the central Pt atom during the T1-S0 transition. Furthermore, in the well-known luminescent cyclometalated Ir(III) complexes39, such as fac-Ir(ppy)3 (ppy = phenylpyridinate anion)40, the pronounced participation of the Ir 5dz2 orbital in the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) promotes remarkable charge transfer on the central Ir atom and also leads to high SOCs11,41–43 during the T1-S0 transition. Therein, the typical octahedral coordination geometry of the Ir center facilitates substantial mixing between the Ir 5dz2 orbital and the aromatic ligand π orbitals. For aurophilic interaction-based aggregates of some Au(I) compounds, it is found that their ligand-to-metal-metal charge transfer (LMMCT) can significantly enhance the involvement of gold orbitals in transitions, thus promoting SOC and improving TADF properties44,45. In contrast, the common linear coordination mode of an Au(I) center hinders effective participation of Au 6s orbital in frontier orbitals upon mixing with π and π* molecular orbitals of aromatic ligands because of unmatched orbital symmetry (Fig. 1). This limitation mostly accounts for low T1-S0 SOC and the resulting poor phosphorescence performance of some mononuclear gold(I) complexes. To address the formidable challenge for the development of gold(I) complexes with excellent phosphorescence performance, we conceive that a gem-digold moiety with two gold atoms positioned on either side of an aromatic ring may potentiate the interaction of its group orbital, composed of two Au 6s orbitals, with the aromatic ring π orbitals as a result of matched orbital symmetry. Furthermore, intermolecular aurophilic linkage is also attempted to enhance SOC effect. These combinations may promote the participation of gold atoms in frontier orbitals and charge transfer, finally promoting T1-S0 SOC in emission-related transitions.

Fig. 1. Orbital reorganization and SOC enhancement.

Schematic of SOC and phosphorescence enhancement in organogold(I) compounds based on the reorganization of frontier orbitals in this work.

In this study, a series of gem-digold(I) aryls were synthesized through a stepwise transmetalation and saturated coordination process. By converting monogold(I) compounds into their gem-digold(I) counterparts, the orbital symmetry adaptation indeed enables efficient interaction of the digold group orbitals with the π orbitals of aryl donor ligands. Furthermore, electron transfer from the aryl donor ligands to gold atoms effectively reduces the Pauli repulsion between gold atoms and leads to ligand-dependent intermolecular aurophilic interaction, finally resulting in aurophilic interaction-based aggregation of digold compounds. Such aurophilic linkage reconstructs the HOMO and LUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital) frontier orbitals and significantly enhances the participation of 5d and 6s orbitals of gold atoms in phosphorescence emission. Consequently, the fluorescence-phosphorescence dual emission observed in monogold(I) compounds changes into the only phosphorescence emission in gem-digold(I) compounds. Accordingly, we observed a remarkable increase of T1-S0 SOC from 0.2–9.6 cm−1 in aryl monogold(I) compounds through 2.4–15.1 cm−1 in digold compounds to maximum 239.0 cm−1 in the dimer of digold compounds. More importantly, the PLQYs of aurophilic interaction-based aggregates reach up to 78% in the solid state, making it among the highest PLQYs observed in polynuclear gold(I) compounds to date (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Results

Synthesis and structural characterization

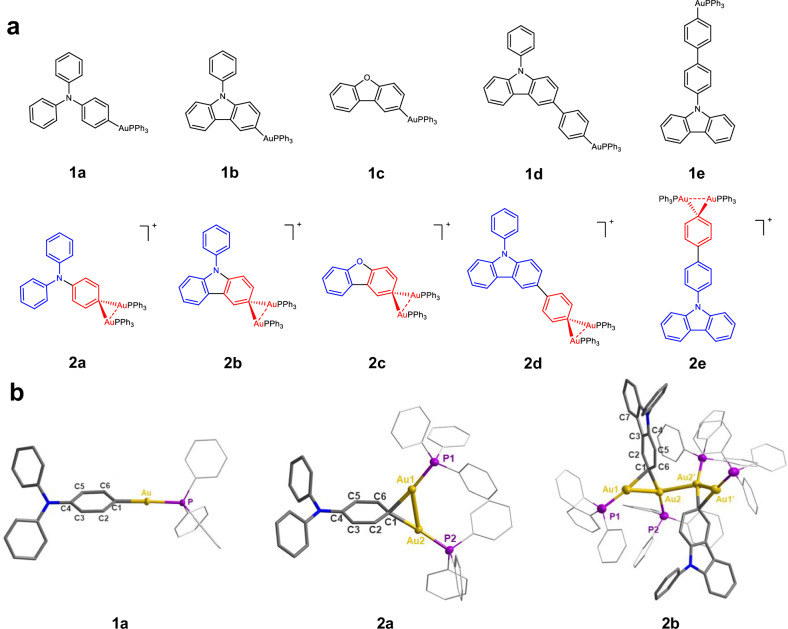

Geminally diaurated organogold(I) compounds as intermediates widely exist in gold-catalyzed organic transformations46–54. In view of the similarity of aryl digold complexes with the Wheland intermediate in electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions55, it is expected that the diauration may diminish the electron density of aromatic rings. Accordingly, gem-digold(I) compounds are much more stable when they feature electron-rich aryl or alkenyl ligands56,57, suggesting that the positive charge of a digold(I) species can be efficiently dispersed from the gold(I) centers to the ligands. Therefore, the gem-digold moiety should be properly considered as an electron-withdrawing group. Inspired by organic TADF materials, wherein the combination of electron-rich donor and deficient acceptor groups results in balanced fluorescence oscillator strength58, a narrow S1-T1 energy gap, and enhanced luminescence, we conceive that the coupling of the electron-deficient gem-digold moiety with electron-rich aryl ligands may yield a new type of organometallic donor-acceptor architectures. We hope that such organometallic donor-acceptor structures own high metal atom participation and T1-S0 SOC, and ultimately show strong phosphorescence emission. Accordingly, a series of monogold(I) and gem-digold(I) aryl complexes have been designed and synthesized (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Structural characterization of gem-digold(I) aryls.

a Chemical structures of mono- and di-gold(I) aryl compounds in this work. b Crystal structures of 1a, 2a and 2b. Hydrogen atoms and bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide counter anions are omitted for clarity. Color code: yellow, Au; gray, C; blue, N; purple, P. Selected bond lengths (Å) of 1a: Au-C1 2.045(4). 2a: Au1-Au2 2.769(1); C1-Au1 2.150(5); C1-Au2 2.119(5). 2b: Au1-Au2 2.751(1); Au2-Au2’ 2.877(1); C1-Au1 2.180(5); C1-Au2 2.133(5).

Aryl monogold(I) compounds 1a to 1c were synthesized by transmetalation of aryl boronic acids according to a reported method59. However, this method was not applicable to the synthesis of 1d and 1e. 1d and 1e were then synthesized by direct transmetalation of corresponding organometallic lithium reagents28 and were purified by recrystallization. Attempts to directly acquire gem-diaurated aryl compounds from aryl boronic acids were unsuccessful due to rapid decomposition. We next tried to achieve gem-digold compounds by saturated coordination of monogold(I) aryl compounds. With the 1e-to-2e transformation as an example, the 1:1 mixed solution of 1e and [PPh3Au](NTf2) (NTf2 = bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide anion) in dichloromethane (DCM) gradually turned black, and gold mirror meanwhile formed. Besides the identification of [(PPh3)2Au](NTf2) in the mixed solution via 31P NMR (Supplementary Fig. 1), an isolated colorless crystalline product was determined as a C-C coupling organic compound through X-ray crystallography analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). In order to inhibit this decomposition process, the gem-diaurated aryls 2a to 2e were finally obtained through rapid precipitation from the 1:1 mixed DCM solution of aryl monogold(I) compounds and [PPh3Au](NTf2) by adding petroleum ether. The purity of these products was confirmed by 1H and 31P NMR, as well as electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) (Supplementary Spectra 26–44). Notably, the proton NMR signals corresponding to C2-H and C7-H shift downfield from 8.39 and 8.14 ppm in 1b to 8.96 and 8.26 ppm in 2b, respectively, supporting the electron-withdrawing nature of the digold unit (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Our attempts to crystallize 2a-2e only deposited single crystals of 2a, 2b, and 2c, by layering diethyl ether onto the concentrated chloroform solutions of corresponding precipitate samples at −15 °C (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3). Similar procedure on 2d and 2e resulted in only dark precipitates due to rapid decomposition. As shown in X-ray crystallographic analysis, the gem-digold unit in 2a is almost equally divided by the phenyl plane (126.4° and 142.8° for the dihedral angles of C3 − C2 − C1 − Au1/Au2, respectively). In addition, an alternating single and double bond pattern of the diaurated benzene ring in 2a (1.414(8) Å for C1-C6; 1.366(7) Å for C5-C6; 1.409(8) Å for C4-C5). implies that the diauration allows the digold positive charge to delocalize onto the amino-substituted benzene ring and thus weakens its aromaticity. In contrast to 2a, the digold unit attached on the carbazole ring of 2b is tilted to one side with the dihedral angles of 118.6° and 153.9° for C3 − C2 − C1 − Au1/Au2, respectively. It should be ascribed to the steric hindrance between PPh3 and the carbazole group (Fig. 2b). To our surprise, the gem-digold unit in 2b forms a dimer structure via an intermolecular Au-Au linkage of 2.877(1) Å, which represents one of the shortest unsupported intermolecular aurophilic interactions60–63. Such short Au-Au interaction is strong enough to overcome the Coulomb repulsion between two digold(I) units.

Photophysical studies

The stability of 2a-2e in solution was confirmed by UV-vis absorption spectral monitoring. As shown in the time-dependent UV-vis spectra in DCM (Supplementary Fig. 4), 2a-2e all show negligible changes over one hour. The emission spectra of 2a-2e exhibits luminescence 0-0 bands at 457 nm [τ1 = 0.48 ns (89.6%) and τ2 = 4.19 ns (10.4%)], 409 nm [τ1 = 1.60 ns (97.6%) and τ2 = 10.19 ns (2.4%)], 330 nm [no measured lifetime], 447 nm [τ1 = 0.04 ns (95.1%) and τ2 = 1.03 μs (4.9%)] and 487 nm [τ1 = 0.18 ns (97.3%) and τ2 = 0.94 ns (2.7%)], respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 3). The emission lifetime of 2c cannot be determined because of its extremely weak emission. The nanosecond lifetimes of these compounds indicate a fluorescence emission nature. We tried to measure the PLQYs for 2a-2e. However, only the values of 2b, 2d, and 2e can be determined as 0.6%, 1.1%, and 2.7%, respectively, due to their relatively strong emission. Such low PLQYs of 2a-2e should be attributed to their flexible gem-digold structures as reported in several gem-digold compounds56,57,64, which likely cause high non-radiative decay rates. The relatively faster emission rates of 2 d and 2e over 2a, 2b, and 2c are probably ascribed to the extended phenyl π bridges in 2d and 2e, which may enhance HOMO-LUMO overlap58 and thereby increase fluorescence oscillator strength (Supplementary Table 3). To verify the donor-acceptor nature of these gem-digold(I) aryls, we next carried out the studies on solvent-dependent UV-Vis absorption spectra (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Upon the decrease of solvent polarity from DCM to chloroform, we observed a remarkable blue shift of absorption peaks for 2a (Δλ = 61 nm), 2 d (Δλ = 80 nm), and 2e (Δλ = 50 nm). This result indicates a charge transfer transition with the ground-state dipole being smaller in magnitude than the excited-state dipole65. In contrast, the absorption of 2b and 2c show negligible shifts upon solvent change, suggesting a local excitation nature. These results are consistent with the observed blue shift in emission spectra along with the decrease of solvent polarity by tuning the DCM/n-hexane ratio in mixed solutions (Supplementary Fig. 8).

DFT calculations were then performed to investigate the luminescence mechanism of the gem-diaurated gold(I) aryls. 1a and 2a were taken as an example. Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis indicates that the frontier molecular orbitals of 1a are mainly contributed by the aryl and phosphine ligands (Supplementary Fig. 9). The HOMO orbital is composed of 98.2% 2p orbitals from the aryl ligand and 1.0% 5d orbitals from gold atoms, and the LUMO orbital arises from 97.4% 2p and 3p orbitals from the phosphine ligands and 1.2% 5d orbitals from gold atoms. Molecular orbital isosurface diagram together with orbital composition analysis reveals that there is no combination between the 6s orbital of gold atom (A1 irreducible representation in C2v group) and the ligand π orbitals (B1 irreducible representation in C2v group) due to the unmatched symmetry55,66. As to 2a, the 6s orbitals of two gold atoms could form a group orbital (B1 irreducible representation in C2v group), which nicely combines with the ligand π orbitals to enhance the gold participation in frontier orbitals. The LUMO orbital of 2a comprises of 39.4% π orbitals of aryl ligand and 17.2% 6s orbitals of gold atoms with the remaining contribution from the PPh3 ligands (Supplementary Fig. 9). Such symmetry change of frontier orbitals from 1a to 2a potentiates the aryl(π)-to-gold(6s) electron transfer. This hypothesis is supported by the Hirshfeld atomic charge of aryl ligand decreasing from −0.29 in 1a to 0.03 in 2a. Meanwhile, the introduction of the digold unit causes the decrease of the LUMO from −1.22 eV of 1a to −3.59 eV of 2a.

To understand the reason of weak phosphorescence emission in solution, we carried out the hole-electron analysis of T1-to-S0 transition based on the T1 energy minimum structure (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). The Sr, D, and t indices are defined as following to provide a profile of electron transition during the T1-S0 phosphorescence emission. Sr (Sr ∈ [0, 1]) and D represent the overlap and distance between hole and electron in T1 state, respectively. t indicates the degree of separation between hole and electron (t > 0: relatively separated in the charge transfer direction; t < 0: less separated in the charge transfer direction)67. The Sr, D, and t indices of aryl monogold(I) compounds show a complete overlap of the hole and electron primarily within the aromatic ring (Supplementary Fig. 10). This result suggests that the phosphorescence emission of monogold compounds is predominantly contributed by 3LC (ligand-centered) transitions. In addition, the overall contribution of gold atoms to the hole and electron for monogold(I) aryl compounds is mostly less than 10% (Supplementary Table 5), which finally accounts for their slow emission rates and low T1-S0 SOC values (Supplementary Table 6). In contrast, the hole-electron analysis of 2a shows a larger D and smaller Sr as a result of a more separated hole and electron distribution primarily on the Ph2N and [PhAu2] moieties (Supplementary Fig. 10, Supplementary Table 4). 2b and 2c that lack rotatable single bonds exhibit a similar hole-electron distribution as their monogold(I) counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 10), but they show a larger D and smaller Sr (Supplementary Table 4). The participation of gold orbitals in digold compounds is increased by approximately four times larger than monogold ones. As to 2d and 2e that feature a more distant donor and acceptor due to the presence of a rotatable single bond and a π-bridge (Supplementary Fig. 10), the nature of the T1-S0 transition changes from a 3LC (ligand-centered) transition to a 3ILCT (intraligand charge transfer) mixed with 3LMCT (ligand-to-metal charge transfer) transition. The smaller Sr and larger D indices of 2d and 2e compared with 2a, 2b, and 2c (Supplementary Table 4) are consistent with the solvent polarity-dependent experiments (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). To investigate the impact of T1-S0 SOC on phosphorescence, the T1-S0 transition rates of monogold(I) and gem-digold(I) aryl compounds were evaluated using quadratic response theory (Supplementary Table 7). From monogold(I) to gem-digold(I) aryl compounds, the T1-S0 transitions of each pair of compounds all experience an increase of the gold atom participation in the hole-electron separation (Supplementary Table 5). Despite significant participation of gold(I) atoms in transition-related molecular orbitals in gem-digold(I) complexes, their components remain much lower than the dominant aryl π orbitals, resulting in low T1-S0 SOC values (Supplementary Table 6), slow phosphorescence emission rates of 102-103 s−1 (Supplementary Table 7) and low PLQYs as well (Supplementary Table 3).

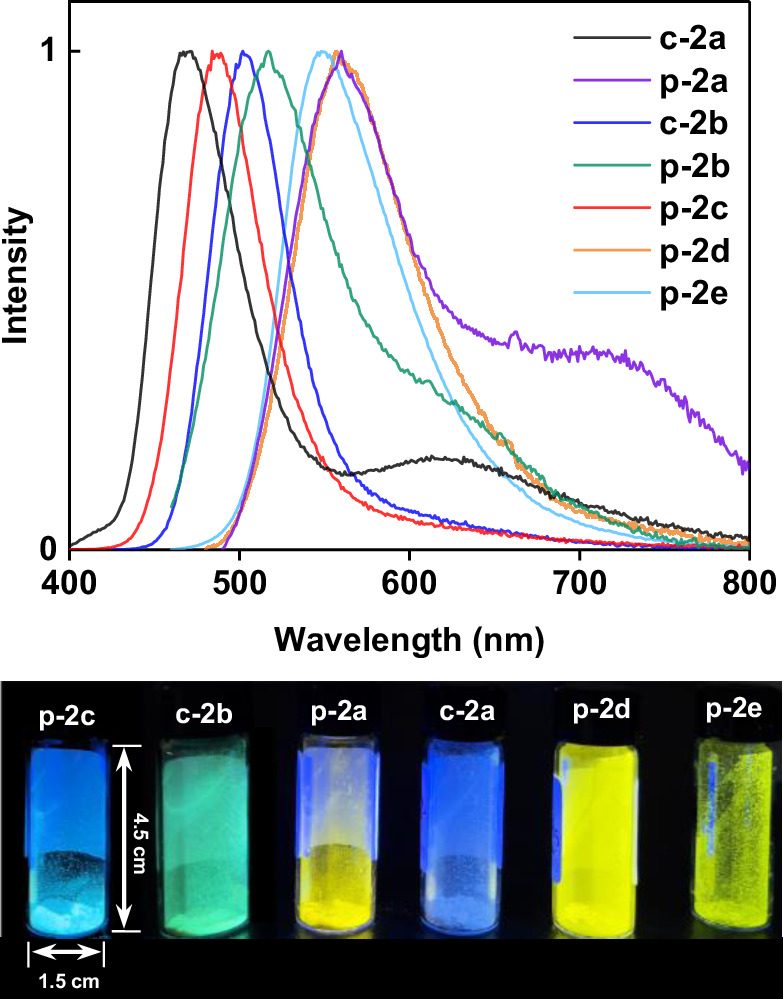

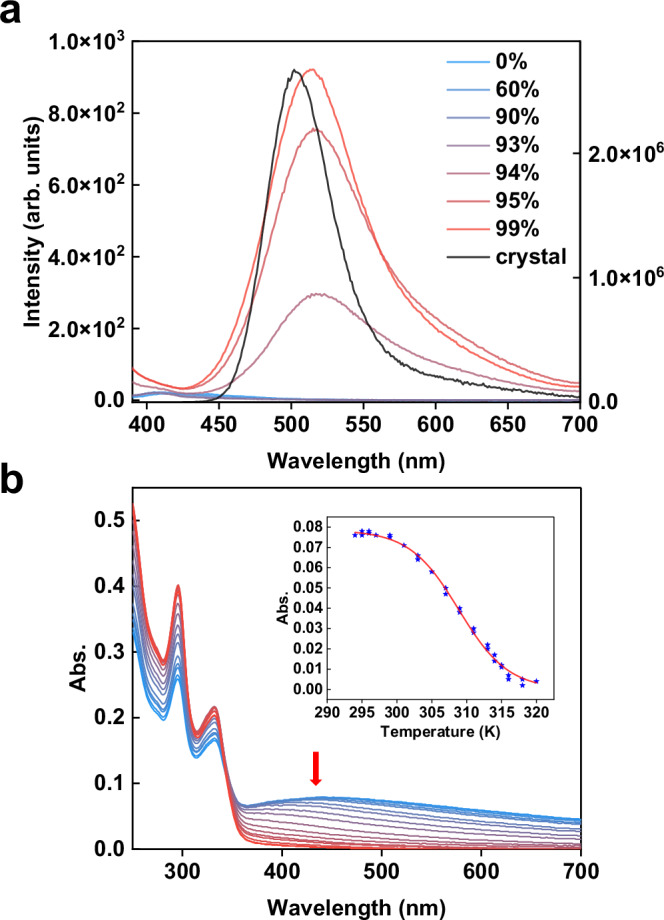

While 2a-2e exhibits weak emission in solution, they display strong luminescence in both crystalline and amorphous precipitate solid states. The precipitate of 2b generated by adding petroleum ether into its dichloromethane solution exhibits strong luminescence with the emission wavelength as similar as the crystalline sample of 2b (Supplementary Fig. 11a). In contrast, the emission band of the crystalline 2a experiences a large blue shift relative to the precipitate sample of 2a (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 11b). We subsequently collected the photophysical parameters of crystalline and precipitate samples to further investigate the luminescence mechanism. The crystalline 2a exhibits two phosphorescence emissions with similar lifetimes at 471 nm [τ1 = 4.98 μs (35.7%) and τ2 = 20.7 μs (64.3%)] and 623 nm [τ1 = 3.35 μs (43.8%) and τ2 = 17.2 μs (56.2%)] (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Table 1). The T1-S0 SOC of 2a is deduced as 4.42 cm−1. This small SOC value accounts for its low phosphorescence radiative rate (kp ~ 103 s−1) and low PLQY of 3.6%. In sharp contrast, the precipitate sample of 2a shows an emission peak at 560 nm with a short life time [τ1 = 3.16 μs (25.3%) and τ2 = 5.27 μs (74.7%)], a high PLQY of 60% and a kp as high as 105 s−1 (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Table 1). The precipitate sample of 2b shows an emission peak at 518 nm [τ1 = 3.06 μs (37.1%) and τ2 = 4.76 μs (62.9%)] with a fast kp ~ 105 s−1 and a high PLQY of 78% (Supplementary Fig. 14), which is similar with the crystalline 2b sample (λem = 506 nm, kp ~ 105 s−1 and knr = 2.46×105 s−1). The other three precipitate samples of 2c [τ1 = 2.05 μs (44.8%) and τ2 = 4.58 μs (55.2%)], 2 d [τ1 = 4.60 μs (30.4%) and τ2 = 10.9 μs (69.6%)] and 2e [τ1 = 4.40 μs (31.5%) and τ2 = 13.0 μs (68.5%)] all show fast kp values around 104-5 s−1 and moderate PLQYs of 22%, 31%, and 24%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 13). The kp values of the precipitate samples of 2a-2e and the crystalline 2b are around 104-5 s−1, which are much faster than the predicted values of 102-3 s−1 by computational simulations (Supplementary Table 7). In contrast, the kp of crystalline 2a is about 103 s−1, much slower than its precipitate samples but in good agreement with the calculations. The scrutiny of crystal structure difference between crystalline 2a and crystalline 2b highlights the dimer structure of 2b linked by intermolecular aurophilic interaction. Therefore, the T1-S0 SOC values of precipitate samples were recalculated considering intermolecular aurophilic interaction-bridged structures (Table 1). Relative to low T1-S0 SOC values of digold monomer structures (Supplementary Table 6), intermolecular aurophilic interaction in digold(I) dimers largely enhances the T1-S0 SOC values by one or two orders of magnitude. We then conducted a poor solvent-induced aggregation experiment to verify the formation of intermolecular aurophilic interaction in precipitate samples. Upon mixing the dichloromethane solution of 2b with n-hexane, an emission peak at 408 nm was observed as the volume fraction of n-hexane below 94%, which should be assigned to the 2b monomer according to ESI-MS (Fig. 4a). When the n-hexane fraction is above 94%, a new green emission band at 513 nm gradually escalates and its intensity is proportional to the n-hexane fraction. The redshift of the emission peak from 408 to 513 nm can be ascribed to the formation of aurophilic interactions, which narrow the HOMO-LUMO gap as reported in previous literatures68,69. The wavelength and peak shape of this new emission band is highly consistent with both the crystalline and precipitate samples of 2b (λem = 506 nm) and the simulated 2b-dimer (λem = 497 nm) (Supplementary Fig. 15). This poor solvent-induced aggregation and similar luminescence were also observed in the other four compounds (2a, 2c, 2d and 2e), which are consistent with the simulated emission spectra of optimized dimer structures (Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17). These results confirm that the enhanced luminescence of precipitate samples arise from the intermolecular aurophilic interaction-caused aggregation.

Fig. 3. Solid emission spectra studies.

Normalized emission spectra of precipitate samples of 2a (p-2a), 2b (p-2b), 2c (p-2c), 2 d (p-2d), 2e (p-2e), and crystalline samples of 2a (c-2a), 2b (c-2b). Inset: photographs of photoluminescence samples under the excitation of λex = 365 nm.

Table 1.

Measured and deduced photophysical data of crystalline and precipitate samples

| Compoundsa | Wavelength (nm) | lifetime (τ/μs) | PLQYb | kp (s−1)c | knr (s−1)c | SOC (cm−1)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystalline 2a | 471 | 4.98 (35.7%), 20.7 (64.3%) | 3.6% | 2.39 × 103 | 6.39 × 104 | 4.42 |

| 623 | 3.35 (43.8%), 17.2 (56.2%) | 3.22 × 103 | 8.64 × 104 | |||

| Precipitate 2a | 560 | 3.16 (25.3%), 5.27 (74.7%) | 60% | 1.27 × 105 | 8.44 × 104 | 9.62 × 101 |

| Crystalline 2b | 506 | 2.63 (99.4%), 18.6 (0.6%) | 33% | 1.21 × 105 | 2.46 × 105 | 2.39 × 102 |

| Precipitate 2b | 516 | 3.06 (37.1%), 4.76 (62.9%) | 78% | 1.89 × 105 | 5.33 × 104 | 2.39 × 102 |

| Precipitate 2c | 487 | 2.05 (44.8%), 4.58 (55.2%) | 22% | 6.38 × 104 | 2.26 × 105 | 1.85 × 102 |

| Precipitate 2d | 560 | 4.60 (30.4%), 10.9 (69.6%) | 31% | 3.45 × 104 | 7.69 × 104 | 6.56 × 101 |

| Precipitate 2e | 550 | 4.40 (31.5%), 13.0 (68.5%) | 24% | 2.33 × 104 | 7.38 × 104 | 3.76 × 101 |

aCrystalline samples were obtained by layering Et2O on the CHCl3 solution of corresponding digold(I) compounds. Precipitate samples were acquired by adding petroleum ether into dichloromethane solutions of 2a-2e.

bTotal photoluminescence quantum yield.

ckp: phosphorescence radiative rates; knr: non-radiative decay rates. Calculation method see the “Methods” section.

dSOC values of T1-to-S0 transition calculated by TD-DFT. The models used for crystalline samples are based on their corresponding single crystal structures, and those for precipitate samples are based on aurophilic interaction dimer structures.

Fig. 4. Aurophilic interaction-caused aggregation.

a Emission spectra of 2b in pure DCM and a mixed solvent of DCM/n-hexane with different volume fractions. c = 1 × 10−5 M. λex = 365 nm. Left axis: emission intensity of solution (arb. units). Right axis: emission intensity of crystals in solid (arb. units). b Temperature-dependent UV-Vis absorption spectral changes of 2b from 286 to 316 K (c = 1 × 10−5 M, CHCl3/n-hexane v/v = 6:94). Inset: the fitting curve of the isodesmic aggregation model calculated by the absorbance at 420 nm. Blue star: Absorbance data at 420 nm at different temperatures.

In order to clarify the strength of intermolecular aurophilic interaction, temperature-dependent UV/vis spectra were applied to experimentally determine the binding enthalpies (Fig. 4b). Since 2d and 2e decompose in solution upon the temperature variation, only the binding enthalpies of 2a, 2b, and 2c were determined. By monitoring the temperature-dependent new absorbance peaks at 450, 420, and 360 nm for 2a, 2b, and 2c, respectively, the enthalpy values of intermolecular aurophilic interaction for 2a, 2b and 2c were deducted as −42.6, −59.1, −35.9 kcal/mol, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 18). The broad absorption peaks together with the excellent fit to the supramolecular polymerization mathematical model suggest the possible formation of aurophilic interaction-based oligomers70. Such significant binding enthalpies compensate the entropy loss in the aggregation process and overcomes the Coulombic repulsion between two positive digold species. Moreover, different aggregation enthalpy values of 2a, 2b, and 2c suggest that the strength of intermolecular metallophilic interaction can be tailored by the central ligands, and electron-rich ligands enhance the aurophilic interaction.

Theoretical studies on enhanced aurophilic interactions and T1-S0 SOC

We subsequently carried out density functional theory (DFT) calculation to clarify the strong unsupported intermolecular aurophilic interactions and intense phosphorescence enhancement in 2a-2e. Five model compounds were designed according to the dimeric crystal structure of 2b by changing aryl ligands from electron-rich (2f-dimer) to electron-deficient (2h-dimer) (Fig. 5a). The resulting donor-enhanced intermolecular aurophilic interaction was evaluated by Au(I)-Au(I) distances and dimerization free energies (Fig. 5b). With the increase of Hirshfeld charge of the C-Au2 fraction from 2f-dimer to 2h-dimer, the intermolecular Au-Au length gradually increases from 2.89 to 2.98 Å. Meanwhile, the dimerization free energy decreases from −6.1 to 1.5 kcal/mol. Furthermore, the interaction region indicator (IRI) analysis indicates that ligand dispersion and strong Au(I)-Au(I) interaction both play an important role in the donor-enhanced intermolecular aurophilic interaction (Supplementary Fig. 19). Further energy decomposition analysis was applied to quantify the contribution of each interaction to the intermolecular aurophilic interaction (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 20). At the set Au(I)-Au(I) distance of 2.89 Å, the Pauli repulsion of 2b-dimer (166.3 kcal/mol) is much lower than that of 1b-dimer (252.7 kcal/mol). As consequence, the balanced Au(I)-Au(I) distance of 1b-dimer is 3.21 Å, in sharp contrast to 2.89 Å for 2b-dimer.

Fig. 5. Theoretical studies on aurophilic interaction and T1-S0 SOC enhancement.

a Chemical structures of aurophilic interaction-linked dimer model compounds. b Balanced aurophilic interaction distances calculated at PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP level (data point) and Gibbs free energy calculated at PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP//PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP level (blue bar) along with the variation of Hirshfeld charge. c Energy decomposition analysis on intermolecular aurophilic interaction in five dimer model compounds at PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP level. Etot, total interaction energy; Eels, electrostatic interaction component; Ex, exchange energy component; Eorb, orbital interaction component; EDFTc, DFT correlation energy component.; Edc, dispersion correction component.; Erep, Pauli repulsion energy component. d T1-S0 SOC values calculated at DKH2-PBE0/DKH-def2-TZVP (C, H, O, N, P, F), SARC-DKH-TZVP (Au) level (blue bar) and hole-electron participation calculated at PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP level (data point) of aryl gold(I) compounds. e Diagrams of HOMO and LUMO orbitals for 2b and 2b-dimer calculated at PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP level (isovalue:0.03).

The relationship between the hole-electron participation of gold atoms and T1-S0 SOC values was also evaluated. As shown in Fig. 5d, the enhancement of hole-electron participation of gold atoms by dimerization indeed causes the increase of T1-S0 SOC values relative to corresponding monogold(I) and gem-digold(I) aryl compounds. Meanwhile, the simulated phosphorescence emission rates for 2a-dimer, 2b-dimer, and 2c-dimer are 1.81 × 104, 1.12 × 105, and 2.72 × 104 s−1 respectively, which have been greatly improved relative to the values of monomer complexes 2a, 2b and 2c (Supplementary Table 7). In addition, such calculated values are consistent with the experimental phosphorescence radiative rates of 1.27 × 105, 1.89 × 105, and 6.38 × 104 s−1, respectively. For the dimer structures, the hole in T1 state is predominantly distributed on the electron-rich donor group, and the electron is majorly located on the intermolecular Au-Au as well as the diaurated aromatic ring. Finally, the origin of the T1 excited state could be assigned to 3LMMCT with some gold(I)-gold(I) d-s transitions (Supplementary Fig. 21). The aurophilic interactions increase the participation of gold atoms in the hole-electron by 2–10 times (Supplementary Table 5). The 2b and 2b-dimer was chosen as an example to make clear the orbital recombination during dimerization. As shown in charge decomposition analysis (CDA) (Fig. 5e), the 2b-to-2b-dimer transformation leads to the recombination of HOMO and LUMO orbitals of monomer 2b (M-HOMO and M-LUMO) by mixing 5d-5d and 6s-6s orbitals of gold atoms. The reorganized orbitals become the major contributor for the dimer HOMO/LUMO orbitals, rather than the aryl ligand orbitals in monomer. The orbital composition analysis by natural atomic orbital (NAO) method indicates that the HOMO of 2b-dimer is composed of 4.2% 6s plus 11.1% 5d orbitals of gold atoms, and 80.6% of the aryl ligand. The LUMO comprises of 16.7% 6s orbitals of gold atoms and 41.1% of the aryl ligand (Supplementary Table 8). Consequently, the aggregation enhances the participation of gold atoms in transition-related frontier orbitals and potentiates the T1-S0 SOC effect (Table 1 and Fig. 5d). The high T1-S0 SOC finally accounts for rapid phosphorescence radiative rates of 104~5 s−1 and high PLQYs up to 78%.

In summary, we have successfully achieved a new class of highly efficient phosphorescent gold(I) compounds by constructing gem-digold(I) aryl donor-acceptor structures and promoting the formation of intermolecular aurophilic interaction-based aggregates. The emission color can be effectively tuned from blue to yellow with high PLQYs up to 78% in solid state, which is among the highest PLQYs observed in polynuclear gold(I) compounds to date. This study demonstrates that, compared to monogold(I) aryl compounds, the gem-digold unit allows for better integration of the π orbitals of aryl ligands with the gold 6s orbitals, thereby enhancing the participation of gold orbitals in the LUMO orbital. This diauration also facilitates electron transfer from the central aryl ligand to the empty 6s orbital of gold atoms and thus make the digold(I) species as an acceptor group. Importantly, the donor ligand reduces the Pauli repulsion of digold(I) aryls and engenders the formation of aurophilic interaction-linked structures. The aurophilic interactions exponentially enhance T1-S0 SOC and lead to high-efficiency phosphorescent emission. This work opens up a new avenue to achieve high-efficiency phosphorescent organometallic compounds and provides insights into the modulation of T1-S0 SOC by tuning metallophilic interaction.

Methods

General information

(9-phenyl-9H-carbazol-3-yl)boronic acid, (4-(9H-carbazol-9-yl)phenyl)boronic acid, dibenzo[b,d]furan-2-ylboronic acid and (4-(diphenylamino)phenyl)boronic acid were purchased from Bide Pharmatech. Anhydrous isopropanol, [Au(PPh3)Cl], 1-bromo-4-iodobenzene, and AgNTf2 were purchased from Energy Chemical. All other reagents and solvents were used without further purification. The solvents used in this study were dried by standard procedures. For photophysical measurements, all solvents used were spectroscopic grade.

1H, 13C, 31P, 2D 1H-1H COSY, and 2D 1H-1H NOESY NMR were carried out on a JEOL ECX-400 MHz instrument. High resolution electrospray ionizationmass spectrometry (ESI-MS) were obtained on a Thermo Scientific Exactive Orbitrap instrument. UV-vis spectra were recorded on a Cary 7000 UV-vis-NIR spectrophotometer. The fluorescence spectra were measured using an Agilent Cary Eclipse apparatus.

Photophysical experiment

The photoluminescence absolute quantum yields were measured on an Edinburgh FLS980 spectrometer and defined as the number of photons emitted per photon absorbed by the systems and measured with an integrating sphere. Luminescent decay experiments were measured on an Edinburgh FLS980 spectrometer using time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC). The photophysical parameters were calculated using the following equations71:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where Φp is the phosphorescence quantum yield. Φisc is the quantum efficiency of intersystem crossing from S1 to Tn states. kf and kic are the radiative and internal conversion decay rates of S1 → S0, respectively. In our system, there is no fluorescence, therefore, Φisc is estimated to be approximately equal to 1. τ is the phosphorescence lifetime, kp is the phosphorescence emission rate, and knr is the non-radiative decay rates.

Measurement of aurophilic interaction-caused aggregation enthalpy

To measure the binding enthalpy of 2a, 2b, and 2c during the aurophilic interaction-caused aggregation process, an isodesmic self-assembly model was applied and used in the work70,72:

| 4 |

where a is the degree of aggregation, ΔH is the entropy release during the aurophilic interaction-caused aggregation process, Tm is the melting temperature. ε(T) is the measured extinction coefficient at temperature T; εM and εA are the extinction coefficients of the monomer and fully aggregated state, respectively. In general, the absorption wavelength is chosen to make εM = 0. The equation can be written as:

| 5 |

where Abs(T) is the absorbance at temperature T, and AbsA is the absorbance when fully aggregated. The absorbance Abs(T) versus temperature was obtained by measuring the UV/Vis absorption spectra at different temperatures: from 279 K to 303 K for 2a, 294 K to 320 K for 2b, and 276 K to 304 K for 2c. These measurements were conducted in a mixed solution (n-hexane/CHCl3, 94:6 v/v). At least two data points were collected at each temperature, with some invalid data points excluded from analysis due to water mist precipitation occurring during the experiment at temperatures below 285 K. Due to the low temperatures required for 2c aggregation, we could not collect enough data points for fitting within the temperature range allowed by the instrument. Consequently, AbsA was estimated as 0.1 based on the structurally similar compound 2b.

General synthetic method of 2a to 2e

Aryl gold(I) compounds (0.02 mmol, 1.0 equiv), [PPh3AuNTf2] (14.8 mg, 0.02 mmol, 1.0 equiv), and DCM (3 mL) were added to a 50 mL round bottom flask. The solvent was vigorously shaken to ensure thorough mixing within one minute. Petroleum ether (40 mL) was then added to the solution, and DCM was slowly removed under reduced pressure at 0 °C. The mixture was allowed to stand for 15 min at 0 °C to ensure complete precipitation of the product. Then the product precipitate was filtered.

2a: Yellow solid, yield: 91% (26 mg). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 7.83 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.56-7.46 (m, 8H), 7.43-7.33 (m, 30H), 7.23 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 4H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H). 31P-NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 37.13. HR-MS (ESI): calcd. for [2a-NTf2]+ (C54H44Au2NP2+) 1162.2275, found 1162.2284.

2b: Yellow solid, yield: 87% (25 mg). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 8.97 (s, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.59-7.48 (m, 13H), 7.43-7.33 (m, 26H). 31P-NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 37.31. HR-MS (ESI): calcd. for [2b-NTf2]+ (C54H42Au2NP2+) 1160.2118, found 1160.2126.

2c: White solid, yield: 77% (21 mg). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 8.81 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.58-7.48 (m, 8H), 7.47-7.30 (m, 24H). 31P-NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 37.19. HR-MS (ESI): calcd. for [2c-NTf2]+ (C48H37Au2OP2+) 1085.1645, found 1085.1643.

2d: Yellow solid, yield: 87% (25 mg). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 8.46 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 3H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.60-7.47 (m, 12H), 7.46-7.31 (m, 27H). 31P-NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 37.28. HR-MS (ESI): calcd. for [2d-NTf2]+ (C60H46Au2NP2+) 1236.2431, found 1236.2423.

2e: Yellow solid, yield: 82% (24 mg). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 8.18 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 8.15 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.94 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.90 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.56-7.37 (m, 34H), 7.30 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H). 31P-NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 37.58. HR-MS (ESI): calcd. for [2e-NTf2]+ (C60H46Au2NP2+) 1236.2431, found 1236.2419.

Computational details

The structures of aryl gold(I) compounds 1a to 1e for calculation were built based on their single-crystal structures. The structures of gem-diaurated gold(I) aryl monomers 2a and 2c were also built based on their corresponding single-crystal structures. The structures of 2b, 2d, and 2e were built based on the single-crystal structure of 2b. The gem-diaurated gold(I) aryl dimers 2a to 2h were constructed based on the single crystal structure of 2b. Geometry optimizations of the S0 and T1 states in the gas phase were performed using the ORCA 5.0.3 program73,74 with DFT and UDFT, respectively. The hybrid functional PBE075,76 with Grimme GD3(BJ) dispersion correction77,78 and the def2-SVP basis set79,80, was used for geometry optimization. To speed up the calculations, density fitting together with the chain of spheres approximations as implemented in ORCA (RIJCOSX)81 was used, with the auxiliary basis def2/J82. The geometry of models was visualized by CYLview20 software83.

The hole-electron analysis67 for T1 → S0 excitations was conducted by the Multiwfn 3.8 program84 in the optimized T1 structures. The wavefunction and configuration coefficients were calculated by Gaussian 16 program85 with time-dependent DFT at PBE075,76-D3(BJ)77,78/def2-SVP79,80 level in the gas phase. The UV-Vis absorption spectrum was calculated at the PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP level in the SMD (dichloromethane) solvent model, using optimized S0 structures, and 80 singlet states were considered for the calculations.

Spin-orbit coupling of singlet and triplet states calculations are carried out with the ORCA 5.0.3 program in the optimized T1 structures. All-electron calculation for spin-orbit coupling was performed with PBE0 functional75,76, DKH2 Hamiltonian86–89, DKH-def2-TZVP basis sets79,90 for C, H, N, O, F, P atoms, SARC-DKH-TZVP basis sets90 for Au atoms. To speed up the calculations, density fitting together with the chain of spheres approximations as implemented in ORCA (RIJCOSX)81 was used, with the auxiliary basis SARC/J82,90. The Dalton 2020.1 program91,92 was employed for the calculations of the T1 - S0 phosphorescence transition rates at the B3LYP93,94/6–31 g*95/SDD80 theoretical level.

Molecular thermochemistry properties of 2f-dimer, 2b-dimer, 2c-dimer, 2g-dimer, and 2h-dimer were evaluated using the Gaussian 09 program96. Geometry optimizations as well as frequency calculations for all species considered here were optimized with the hybrid functional PBE0 with Grimme GD3(BJ) dispersion correction and the def2-SVP basis sets in the gas phase. The optimized structures were confirmed to have no imaginary vibrational mode for all species. Thermal corrections were obtained by frequency calculations using the same method on optimized structures within the harmonic potential approximation under 298.15 K and 1 atm pressure. Single point energy was calculated based on the optimized structures with the hybrid functional PBE0 with Grimme GD3(BJ) dispersion correction and def2-TZVP basis sets79,80 in the solvent chloroform. The integral equation formalism polarizable continuum (IEFPCM) solvation model with SMD radii97 was used for solvent effect corrections. The basis set superposition error correction was considered by counterpoise method at PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP level in the gas phase.

Wavefunction analysis was performed based on the structures optimized in molecular thermochemistry properties calculation and at PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP level. Natural Bond Orbital analysis for orbital compositions were performed by NBO 6.098 and Multiwfn 3.8 software. Hirshfeld atomic charges99, interaction region indicator (IRI)100, and charge decomposition analysis (CDA)101 were performed using Multiwfn 3.8 software. Energy decomposition analysis (EDA) was performed using the most recently proposed sobEDA method102, which is based on Gaussian 16 at PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP level, in conjunction with the Multiwfn program. The molecular orbitals and hole and electron distributions were visualized by Multiwfn 3.8 and VMD 1.9.3103.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22025105, 22350002, and 21821001) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank the Tsinghua Xuetang Talents Program for providing computational resources.

Author contributions

L.Z. and X.-Y.Z. conceived the project. The synthetic experiments, structural characterizations, photophysical experiments, and DFT calculations were performed by X.-Y.Z. X.-Y.Z. and L.Z. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Osamu Tsutsumi, Xiao-Ping Zhou, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Full characterization data including high-resolution ESI-MS, NMR, UV-vis spectra, emission spectra, emission lifetime experiments, and experimental details are listed in the supplementary information. Coordinates of the optimized structures are provided as source data in the Supplementary Data 1 Excel file. All raw data are available on Figshare 10.6084/m9.figshare.26885434. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC-2368909 (1a), CCDC-2368912 (1b), CCDC-2368910 (1c), CCDC-2368911 (1d), CCDC-2368906 (1e), CCDC-2368907 (2a), CCDC-2368914 (2b), CCDC-2368913 (2c), CCDC-2368908 (2e-decomposition). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-55842-w.

References

- 1.Yam, V. W.-W. & Lo, K. K.-W. Luminescent polynuclear d10 metal complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev.28, 323–334 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 2.López-de-Luzuriaga, J. M., Monge, M. & Olmos, M. E. Luminescent aryl–group eleven metal complexes. Dalton Trans.46, 2046–2067 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yam, V. W.-W. & Cheng, E. C.-C. Highlights on the recent advances in gold chemistry—a photophysical perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev.37, 1806–1813 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinto, A., Svahn, N., Lima, J. C. & Rodríguez, L. Aggregation induced emission of gold(i) complexes in water or water mixtures. Dalton Trans.46, 11125–11139 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pujadas, M. & Rodríguez, L. Luminescent phosphine gold(I) alkynyl complexes. Highlights from 2010 to 2018. Coord. Chem. Rev.408, 213179 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di, D. et al. High-performance light-emitting diodes based on carbene-metal-amides. Science356, 159–163 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li, T.-Y., Zheng, S.-J., Djurovich, P. I. & Thompson, M. E. Two-coordinate thermally activated delayed fluorescence coinage metal complexes: molecular design, photophysical characters, and device application. Chem. Rev.124, 4332–4392 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jazzar, R., Soleilhavoup, M. & Bertrand, G. Cyclic (Alkyl)- and (Aryl)-(amino)carbene coinage metal complexes and their applications. Chem. Rev.120, 4141–4168 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrera, R. P. & Gimeno, M. C. Main avenues in gold coordination chemistry. Chem. Rev.121, 8311–8363 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amouri, H. Luminescent complexes of platinum, iridium, and coinage metals containing n-heterocyclic carbene ligands: design, structural diversity, and photophysical properties. Chem. Rev.123, 230–270 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baryshnikov, G., Minaev, B. & Ågren, H. Theory and calculation of the phosphorescence phenomenon. Chem. Rev.117, 6500–6537 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koseki, S., Schmidt, M. W. & Gordon, M. S. Effective nuclear charges for the first- through third-row transition metal elements in spin-orbit calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A102, 10430–10435 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Che, C.-M., Chao, H.-Y., Miskowski, V. M., Li, Y. & Cheung, K.-K. Luminescent μ-ethynediyl and μ-butadiynediyl binuclear gold(i) complexes: observation of 3(ππ*) emissions from bridging Cn2− units. J. Am. Chem. Soc.123, 4985–4991 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu, W.-F., Chan, K.-C., Miskowski, V. M. & Che, C.-M. The intrinsic 3[dσ*pσ] emission of binuclear gold(I) complexes with two bridging diphosphane ligands lies in the near UV; emissions in the visible region are due to exciplexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.38, 2783–2785 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma, Y. et al. High luminescence gold(I) and copper(I) complexes with a triplet excited state for use in light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater.11, 852–857 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yam, V. W.-W., Lai, T.-F. & Che, C.-M. Novel luminescent polynuclear gold(I) phosphine complexes. Synthesis, spectroscopy, and X-ray crystal structure of [Au3(dmmp)2]3+[dmmp = bis(dimethylphosphinomethyl)methylphosphine]. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 12, 3747–3752 (1990).

- 17.Pei, X.-L. et al. Single-gold etching at the hypercarbon atom of C-centred hexagold(I) clusters protected by chiral N-heterocyclic carbenes. Nat. Commun.15, 5024 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foianesi-Takeshige, L. H. et al. Reversible luminochromism of an n-heterocyclic carbene-protected carbon-centered hexagold(I) cluster by solvent and mechanical stimuli. Adv. Opt. Mater.11, 2301650 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 19.He, X. & Yam, V. W.-W. Luminescent gold(I) complexes for chemosensing. Coord. Chem. Rev.255, 2111–2123 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yam, V. W.-W., Au, V. K.-M. & Leung, S. Y.-L. Light-emitting self-assembled materials based on d8 and d10 transition metal complexes. Chem. Rev.115, 7589–7728 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Partyka, D. V., Esswein, A. J., Zeller, M., Hunter, A. D. & Gray, T. G. Gold(I) pyrenyls: excited-state consequences of carbon-gold bond formation. Organometallics26, 3279–3282 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao, L. et al. Mono- and di-gold(I) naphthalenes and pyrenes: syntheses, crystal structures, and photophysics. Organometallics28, 5669–5681 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Partyka, D. V. et al. Copper-catalyzed Huisgen [3 + 2] cycloaddition of gold(I) alkynyls with benzyl azide. syntheses, structures, and optical properties. Organometallics28, 6171–6182 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogt, R. A., Gray, T. G. & Crespo-Hernández, C. E. Subpicosecond intersystem crossing in mono- and di(organophosphine)gold(I) naphthalene derivatives in solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 14808–14817 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogt, R. A., Peay, M. A., Gray, T. G. & Crespo-Hernández, C. E. Excited-state dynamics of (organophosphine)gold(I) pyrenyl isomers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.1, 1205–1211 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mihaly, J. J. et al. Synthetically tunable white-, green-, and yellow-green-light emission in dual-luminescent gold(I) complexes bearing a diphenylamino-2,7-fluorenyl moiety. Inorg. Chem.61, 1228–1235 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen, M.-H. & Yip, J. H. K. Gold(I) and platinum(II) tetracenes and tetracenyldiacetylides: structural and fluorescence color changes induced by σ-metalation. Organometallics29, 2422–2429 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heng, W. Y., Hu, J. & Yip, J. H. K. Attaching gold and platinum to the rim of pyrene: a synthetic and spectroscopic study. Organometallics26, 6760–6768 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gutiérrez-Blanco, A., Fernández-Moreira, V., Gimeno, M. C., Peris, E. & Poyatos, M. Tetra-Au(I) complexes bearing a pyrene tetraalkynyl connector behave as fluorescence torches. Organometallics37, 1795–1800 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang, J., Zhang, S., Zhou, B.-W., Wang, W. & Zhao, L. Hyperconjugative aromaticity-based circularly polarized luminescence enhancement in polyaurated heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 23442–23451 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao, K., Xue, Y., Yang, B. & Zhao, L. Ion-pairing chirality transfer in atropisomeric biaryl-centered gold clusters. CCS Chem.3, 555–565 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamze, R. et al. “Quick-Silver” from a systematic study of highly luminescent, two-coordinate, d10 coinage metal complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 8616–8626 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conaghan, P. J. et al. Highly efficient blue organic light-emitting diodes based on carbene-metal-amides. Nat. Commun.11, 1758 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muniz, C. N., Schaab, J., Razgoniaev, A., Djurovich, P. I. & Thompson, M. E. π-extended ligands in two-coordinate coinage metal complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 17916–17928 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson, S., Eng, J. & Penfold, T. J. The intersystem crossing of a cyclic (alkyl)(amino) carbene gold (I) complex. J. Chem. Phys.149, 014304 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song, X.-F., Peng, L.-Y., Chen, W.-K., Gao, Y.-J. & Cui, G. Theoretical studies on thermally activated delayed fluorescence of “carbene-metal-amide” Cu and Au complexes: geometric structures, excitation characters, and mechanisms. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.25, 29603–29613 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eng, J., Thompson, S., Goodwin, H., Credgington, D. & Penfold, T. J. Competition between the heavy atom effect and vibronic coupling in donor-bridge-acceptor organometallics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.22, 4659–4667 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, Y., Peng, Q. & Shuai, Z. A computational scheme for evaluating the phosphorescence quantum efficiency: applied to blue-emitting tetradentate Pt(II) complexes. Mater. Horiz.9, 334–341 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, T.-Y. et al. Rational design of phosphorescent iridium(III) complexes for emission color tunability and their applications in OLEDs. Coord. Chem. Rev.374, 55–92 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sprouse, S., King, K. A., Spellane, P. J. & Watts, R. J. Photophysical effects of metal-carbon.sigma. bonds in ortho-metalated complexes of iridium(III) and rhodium(III). J. Am. Chem. Soc.106, 6647–6653 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jansson, E., Minaev, B., Schrader, S. & Ågren, H. Time-dependent density functional calculations of phosphorescence parameters for fac-tris(2-phenylpyridine) iridium. Chem. Phys.333, 157–167 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Minaev, B., Ågren, H. & Angelis, F. D. Theoretical design of phosphorescence parameters for organic electro-luminescence devices based on iridium complexes. Chem. Phys.358, 245–257 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brahim, H. & Daniel, C. Structural and spectroscopic properties of Ir(III) complexes with phenylpyridine ligands: Absorption spectra without and with spin–orbit-coupling. Comp. Theor. Chem.1040-1041, 219–229 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ando, A. et al. Aggregation-enhanced direct S0–Tn transitions and room-temperature phosphorescence in gold(I)-complex single crystals. Aggregate3, e125 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang, H. et al. Achiral Au(I) cyclic trinuclear complexes with high-efficiency circularly polarized near-infrared TADF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202310495 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weber, D., Tarselli, M. A. & Gagné, M. R. Mechanistic surprises in the gold(I)-catalyzed intramolecular hydroarylation of allenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.48, 5733–5736 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seidel, G., Lehmann, C. W. & Fürstner, A. Elementary steps in gold catalysis: the significance of gem-diauration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.49, 8466–8470 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hashmi, A. S. K. et al. Simple gold-catalyzed synthesis of benzofulvenes—gem-diaurated species as “instant dual-activation” precatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.51, 4456–4460 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown, T. J., Weber, D., Gagné, M. R. & Widenhoefer, R. A. Mechanistic analysis of gold(I)-catalyzed intramolecular allene hydroalkoxylation reveals an off-cycle bis(gold) vinyl species and reversible C–O bond formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 9134–9137 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hashmi, A. S. K., Braun, I., Rudolph, M. & Rominger, F. The role of gold acetylides as a selectivity trigger and the importance of gem-diaurated species in the gold-catalyzed hydroarylating-aromatization of arene-diynes. Organometallics31, 644–661 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansmann, M. M., Rudolph, M., Rominger, F. & Hashmi, A. S. K. Mechanistic switch in dual gold catalysis of diynes: C(sp3)–H activation through bifurcation-vinylidene versus carbene pathways. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.52, 2593–2598 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weber, D. & Gagné, M. R. σ-π-Diauration as an alternative binding mode for digold intermediates in gold(i) catalysis. Chem. Sci.4, 335–338 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang, Y., Li, J., Zhu, Y., Li, Y. & Yu, B. Mechanistic insights into the gold(I)-catalyzed activation of glycosyl ortho-alkynylbenzoates for glycosidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.135, 18396–18405 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larsen, M. H., Houk, K. N. & Hashmi, A. S. K. Dual gold catalysis: stepwise catalyst transfer via dinuclear clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 10668–10676 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heckler, J. E., Zeller, M., Hunter, A. D. & Gray, T. G. Geminally diaurated gold(I) aryls from boronic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.51, 5924–5928 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weber, D., Jones, T. D., Adduci, L. L. & Gagné, M. R. Strong electronic and counterion effects on geminal digold formation and reactivity as revealed by gold(I)-aryl model complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.51, 2452–2456 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhdanko, A. & Maier, M. E. Quantitative evaluation of the stability of gem-diaurated species in reactions with nucleophiles. Organometallics32, 2000–2006 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Im, Y. et al. Molecular design strategy of organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. Chem. Mater.29, 1946–1963 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Partyka, D. V., Zeller, M., Hunter, A. D. & Gray, T. G. Relativistic functional groups: aryl carbon-gold bond formation by selective transmetalation of boronic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.45, 8188–8191 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmidbaur, H. & Schier, A. A briefing on aurophilicity. Chem. Soc. Rev.37, 1931–1951 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidbaur, H. & Schier, A. Aurophilic interactions as a subject of current research: an up-date. Chem. Soc. Rev.41, 370–412 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmidbaur, H. & Raubenheimer, H. G. Excimer and exciplex formation in gold(I) complexes preconditioned by aurophilic interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 14748–14771 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Browne, A. R., Deligonul, N., Anderson, B. L., Rheingold, A. L. & Gray, T. G. Geminally diaurated aryls bridged by semirigid phosphine pillars: syntheses and electronic structure. Chem. Eur. J.20, 17552–17564 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Osawa, M., Hoshino, M. & Hashizume, D. Photoluminescent properties and molecular structures of [NaphAu(PPh3)] and [μ-Naph {Au(PPh3)}2] ClO4 (Naph = 2-naphthyl). Dalton Trans. 17, 2248–2252 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Reichardt, C. Solvatochromic dyes as solvent polarity indicators. Chem. Rev.94, 2319–2358 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cotton, F. A. Chemical Applications of Group Theory. (Wiley India, 2003).

- 67.Liu, Z., Lu, T. & Chen, Q. An sp-hybridized all-carboatomic ring, cyclo[18]carbon: Electronic structure, electronic spectrum, and optical nonlinearity. Carbon165, 461–467 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yip, S.-K., Cheng, E. C.-C., Yuan, L.-H., Zhu, N. & Yam, V. W.-W. Supramolecular assembly of luminescent gold(I) alkynylcalix[4]crown-6 complexes with planar η2,η2-coordinated gold(I) centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.43, 4954–4957 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.He, X., Cheng, E. C.-C., Zhu, N. & Yam, V. W.-W. Selective ion probe for Mg2+ based on Au(I)⋯Au(I) interactions in a tripodal alkynylgold(i) complex with oligoether pendants. Chem. Commun. 27, 4016–4018 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Wan, Q., Yang, J., To, W.-P. & Che, C.-M. Strong metal-metal Pauli repulsion leads to repulsive metallophilicity in closed-shell d8 and d10 organometallic complexes. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci.118, e2019265118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma, H., Peng, Q., An, Z., Huang, W. & Shuai, Z. Efficient and long-lived room-temperature organic phosphorescence: theoretical descriptors for molecular designs. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 1010–1015 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smulders, M. M. J. et al. How to distinguish isodesmic from cooperative supramolecular polymerisation. Chem. Eur. J.16, 362–367 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Neese, F. Software update: the ORCA program system-Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci.12, e1606 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neese, F., Wennmohs, F., Becker, U. & Riplinger, C. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. J. Chem. Phys.152, 224108 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adamo, C. & Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: the PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys.110, 6158–6170 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ernzerhof, M. & Scuseria, G. E. Assessment of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional. J. Chem. Phys.110, 5029–5036 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem.32, 1456–1465 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys.132, 154104 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.7, 3297–3305 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Andrae, D., Häußermann, U., Dolg, M., Stoll, H. & Preuß, H. Energy-adjustedab initio pseudopotentials for the second and third row transition elements. Theoret. Chim. Acta77, 123–141 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Neese, F., Wennmohs, F., Hansen, A. & Becker, U. Efficient, approximate and parallel Hartree–Fock and hybrid DFT calculations. A ‘chain-of-spheres’ algorithm for the Hartree–Fock exchange. Chem. Phys.356, 98–109 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.8, 1057–1065 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.CYLview20; Legault, C. Y. Université de Sherbrooke, 2020.

- 84.Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem.33, 580–592 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16, revision A.01 (Wallingford, CT, 2016).

- 86.Hess, B. A. Relativistic electronic-structure calculations employing a two-component no-pair formalism with external-field projection operators. Phys. Rev. A33, 3742–3748 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hess, B. A. Applicability of the no-pair equation with free-particle projection operators to atomic and molecular structure calculations. Phys. Rev. A32, 756–763 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Douglas, M. & Kroll, N. M. Quantum electrodynamical corrections to the fine structure of helium. Ann. Phys.82, 89–155 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wolf, A., Reiher, M. & Hess, B. A. The generalized Douglas–Kroll transformation. J. Chem. Phys.117, 9215–9226 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pantazis, D. A., Chen, X.-Y., Landis, C. R. & Neese, F. All-electron scalar relativistic basis sets for third-row transition metal atoms. J. Chem. Theory Comput.4, 908–919 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aidas, K. et al. The Dalton quantum chemistry program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci.4, 269–284 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dalton, a molecular electronic structure program, Release Dalton2022.0-dev (2022).

- 93.Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys.98, 5648–5652 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B37, 785–789 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Petersson, G. A. et al. A complete basis set model chemistry. I. The total energies of closed‐shell atoms and hydrides of the first‐row elements. J. Chem. Phys.89, 2193–2218 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 96.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, revision E.01 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2013).

- 97.Marenich, A. V., Cramer, C. J. & Truhlar, D. G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B113, 6378–6396 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Glendening, E. D., Landis, C. R. & Weinhold, F. NBO 6.0: Natural bond orbital analysis program. J. Comput. Chem.34, 1429–1437 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hirshfeld, F. L. Bonded-atom fragments for describing molecular charge densities. Theoret. Chim. Acta44, 129–138 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lu, T. & Chen, Q. Interaction region indicator: a simple real space function clearly revealing both chemical bonds and weak interactions. Chem.-Methods1, 231–239 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xiao, M. & Lu, T. Generalized charge decomposition analysis (GCDA) method. J. Adv. Phys. Chem.4, 111–124 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lu, T. & Chen, Q. Simple, efficient, and universal energy decomposition analysis method based on dispersion-corrected density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. A127, 7023–7035 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph.14, 33–38 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Full characterization data including high-resolution ESI-MS, NMR, UV-vis spectra, emission spectra, emission lifetime experiments, and experimental details are listed in the supplementary information. Coordinates of the optimized structures are provided as source data in the Supplementary Data 1 Excel file. All raw data are available on Figshare 10.6084/m9.figshare.26885434. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC-2368909 (1a), CCDC-2368912 (1b), CCDC-2368910 (1c), CCDC-2368911 (1d), CCDC-2368906 (1e), CCDC-2368907 (2a), CCDC-2368914 (2b), CCDC-2368913 (2c), CCDC-2368908 (2e-decomposition). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.