Abstract

KRAS-specific inhibitors have shown promising antitumor effects, especially in non-small cell lung cancer, but limited efficacy in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. Recent studies have shown that EGFR-mediated adaptive feedback mediates primary resistance to KRAS inhibitors, but the other resistance mechanisms have not been identified. In this study, we investigated intrinsic resistance mechanisms to KRAS inhibitors using patient-derived CRC cells (CRC-PDCs). We found that KRAS-mutated CRC-PDCs can be divided into at least an EGFR pathway-activated group and a PI3K/AKT pathway-activated group. In the latter group, PDCs with PIK3CA major mutation showed high sensitivity to PI3K+mTOR co-inhibition, and a PDC with Her2 amplification with PIK3CA minor mutation showed PI3K-AKT pathway dependency but lost KRAS-MAPK dependency by cytoplasmic localization of KRAS. In the PDC, Her2 knockout restored KRAS plasma membrane localization and KRAS inhibitor sensitivity. The current study provides insight into the mechanisms of primary resistance to KRAS inhibitors, including aberrant KRAS localization.

Subject terms: Targeted therapies, Colon cancer, Oncogenes, Chromosomes, Cancer therapeutic resistance

Introduction

The GTPase protein KRAS is commonly mutated in various cancer types, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC), colorectal cancer (CRC), and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), occurring in 90%, 40%, and 20% of cases in each cancer type, respectively1,2. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) positively and negatively regulate the KRAS GTPase cycle from its inactive state (GDP-KRAS) to its active state (GTP-KRAS), respectively3. Codon 12–13 mutations usually impair the KRAS-GTP–GAP interaction, leading to constitutive activation of KRAS and its downstream signaling, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) pathways4. While direct targeting of KRAS has long been challenging due to its high affinity for GTP binding and a lack of small pockets, recent efforts have succeeded in developing mutant KRAS-specific inhibitors5,6. For instance, KRAS-G12C, -G12D, and pan-KRAS inhibitors have been developed and evaluated in clinical settings7–10. These KRAS inhibitors mainly bind to GDP-KRAS to block it from transitioning from inactive form to active GTP form, leading to the suppression of the KRAS effector pathway and elicitation of the antitumor effect. Although the first-leading KRAS-G12C inhibitors Sotorasib (AMG510) and Adagrasib (MRTX849) showed promising response rates (37% and 45%, respectively) in patients with KRAS-G12C-positive NSCLC, these inhibitors demonstrated unsatisfactory response rates (7% and 18%, respectively) in patients with KRAS-G12C-positive CRC, necessitating impediment to their US FDA-based approval for CRC treatment11,12. This highlights the need for research into the intrinsic resistance mechanisms to KRAS inhibitors for improved clinical efficiency in patients with CRC.

Intrinsic, adaptive, and acquired resistance to molecular targeting therapies emerges due to genetic and/or nongenetic alterations. Activating receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) or the PI3K pathway, reactivating MAPK signaling, or inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition mediated intrinsic or adaptive resistance to KRAS inhibitors, which were able to enhanced therapeutic efficacy through the co-targeting of the essential molecules in these pathways in NSCLC or PDAC models13–16. Activating epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) conferred intrinsic resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibitor through MAPK pathway reactivation in CRC models; combining anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab with KRAS inhibitor (e.g., sotolasib) showed synergistic effect in a preclinical study17. Notably, a clinical trial revealed that adagrasib and cetuximab combination therapy resulted in a markedly improved response rate (from 19% to 46%) in patients with CRC harboring KRAS-G12C, suggesting that this combination therapy could be a powerful therapeutic tool for this patient population18. As over 50% of patients with CRC did not show marked responses to the combination therapy, further investigation is required to uncover other potential resistance mechanisms in those cases.

In this study, we evaluated the resistance mechanisms to KRAS inhibitors by establishing patient-derived cells (PDCs) harboring KRAS-G12C and -G12D mutations in CRC. Through inhibitor library screening and genomic profiling, KRAS-mutated CRC-PDCs were characterized, at least, into two groups from the aspect of intrinsic resistance mechanisms. More than half of PDCs showed EGFR-mediated MAPK feedback reactivation in the presence of the KRAS inhibitor (first group), and the PI3K pathway activation conferred resistance to the KRAS inhibitor (second group). Pharmacological and immunoblot analyses revealed that one PDC named JC261 in the latter group had Her2amp and PIK3CAK111E mutation in addition to the KRAS-G12C mutation. PI3K pathway hyperactivation was observed in JC261 cells, with the dual inhibition of PI3K and mTOR effectively suppressing JC261 cell growth. Furthermore, to uncover whether KRAS has oncogenic activity adjacent to the plasma membrane in the PI3K-activating mutation with Her2 amplification harboring cells, we examined KRAS localization. Immunofluorescence staining of KRAS revealed its localization at the cytoplasm in Her2 amplified with PIK3CA-activated cells, whereas this localization shifted to the plasma membrane in Her2 knockout PI3K low-dependency cells. In addition, Her2 knockout cells recovered KRAS–MAPK activity and were sensitive to sotorasib. Our findings highlight that Her2 amplification-mediated aberrant KRAS localization may regulate KRAS–MAPK dependency, indicating intrinsic resistance to KRAS inhibitors.

Results

KRAS-mutated CRC-PDCs were not solely dependent on KRAS

To uncover the intrinsic or acquired resistance mechanisms to KRAS inhibitors, we established new KRAS G12C- and G12D-positive PDCs from surgically resected specimens of patients with CRC, focusing on the analysis of genomic alterations and drug sensitivity profiles. The cell viability of multiple KRAS-mutated cancer cells was evaluated to examine whether the growth and survival of KRAS-mutated CRC cells depend on mutant KRAS, and PDCs were assessed by treating with the KRAS-G12C inhibitor (sotorasib) or KRAS-G12D inhibitor (MRTX1133). In H358, KRAS G12C-positive NSCLC cells, and SW1463, KRAS G12C-mutated CRC cells, 1 µM of sotorasib resulted in a 20% reduction in cell viability compared to the control (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). While SW837, KRAS G12C-mutated CRC cells exhibited intermediate sensitivity to sotorasib, KRAS-G12C PDCs demonstrated insensitivity. In the KRAS-G12D models, commercially available CRC (GP2d cells) were highly sensitive to MRTX1133 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1b). While LS180 CRC and AsPC-1 PDAC cells presented moderate sensitivity to MRTX1133, KRAS-G12D-mutated PDCs demonstrated resistance. Active RAS pull-down assay and immunoblot analysis were then performed to investigate the effect of KRAS inhibitors on these KRAS-mutated CRC-PDCs. The KRAS inhibitor treatment completely suppressed KRAS-GTP for 48 h, whereas suppression of the p-ERK level was temporary and time-dependently recovered until 48 h (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, all PDCs sustained the phospho-AKT levels for 48 h following KRAS inhibitor treatment. Cell viability assay was performed by knocking down KRAS using si-RNAs to examine whether PDCs’ survival depends solely on KRAS. Compared with SW1463, all PDCs tended to maintain cell viability of over 50% following KRAS knockdown, indicating the nonexclusive dependence of KRAS-mutated PDCs on KRAS. These results implied that a single agent of KRAS inhibitors may fail to inhibit cell viability completely in CRC-PDCs similar to the observation of KRAS inhibitor ineffectiveness in clinical trials involving patients with KRAS-mutated CRC, suggesting the activation of a compensatory cell survival pathway upon KRAS suppression.

Fig. 1. Single inhibition of mutant KRAS was not sufficient to abrogate cell viability in CRC-PDCs.

a, b Evaluation of sensitivity to KRAS inhibitors. Cells were treated with 1 µM of sotorasib or 30 nM of MRTX1133 for 72 h. Cell viability was detected by CellTiter-Glo assay, and the relative cell viability to the non-treated condition was calculated. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. c Confirmation of the KRAS downstream signal in KRAS inhibitor treatment. KRAS-G12C and KRAS-G12D CRC cell lines were exposed to 1 µM of sotorasib or 100 nM of MRTX1133 treatment. The cell lysates were collected at each time point and immunoblotted to detect the indicated antibodies (left). d Evaluation of KRAS dependency in KRAS-mutated PDCs. The cell viability was measured by CellTiter-Glo assay, and the relative cell viability to si-ctrl cells was calculated. Data were expressed as mean ± SD.

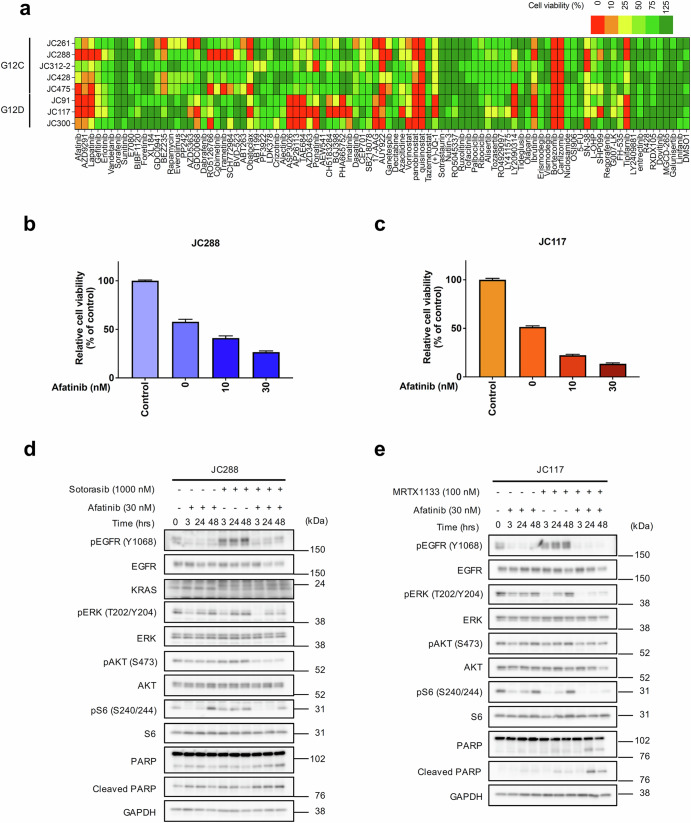

KRAS-G12C with EGFR inhibition proved effective in about half of KRAS-mutated CRC-PDCs

To uncover potential signaling pathways supporting PDC survival upon KRAS inhibition, drug screening was performed using a library of 91 targeted drugs in the presence of a KRAS inhibitor. Inhibitor screening revealed that EGF receptor family inhibitors with the KRAS inhibitor significantly suppressed cell viability in more than half of the CRC-PDCs (Fig. 2a). Next, we assessed cell viability following treatment with a combination of the KRAS inhibitor and the pan-Erbb family inhibitor afatinib. Both JC288 (KRAS-G12C) and JC117 (KRAS-G12D) CRC-PDCs demonstrated sensitivity to the KRAS inhibitor when treated with 10–30 nM of afatinib in combination (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Fig. 2a, 2b). Immunoblot analysis of the KRAS inhibitor with or without afatinib treatment for JC288 or JC117 revealed that single treatment with KRAS inhibitor induced temporal p-ERK suppression that recovered within 24–48 h, but the combination treatment induced continuous p-ERK suppression for 48 h (Fig. 2d, e). Cleaved PARP, an apoptosis marker, was observed to have strongly accumulated in the combination treatment. These results corroborated previously reported findings that MAPK signaling shutdown induced feedback reactivation of the MAPK pathway through EGFR activation in the KRAS-G12C CRC model or BRAF-mutated CRC model as an intrinsic/adaptive resistance mechanism to RAS or RAF inhibitors17,19. Thus, combining RAS or RAF with EGFR inhibitors, mainly anti-EGFR antibodies, has been reported and clinically applied to overcome resistance in patients with CRC harboring KRAS or BRAF mutations.

Fig. 2. Mutant KRAS and EGFR inhibition markedly suppressed cell viability in CRC-PDCs.

a Inhibitor library screening of KRAS-mutated PDCs. Cells were co-cultured with the indicated inhibitors (bottom), 1 µM of sotorasib or 100 nM of MRTX1133 for 72 h. Cell viability was detected by CellTiter-Glo assay, and relative cell viability to a single treatment of KRAS inhibitors was calculated. b Combination efficacy of KRAS-G12C inhibitor (sotorasib) plus Erbb family inhibitor (afatinib). KRAS-G12C PDC (JC288) was exposed to 1 µM of sotorasib with or without the indicated concentrations of afatinib for 72 h. Cell viability was detected by CellTiter-Glo assay, and relative cell viability to non-treated condition was calculated. c Combination efficacy of the KRAS-G12D inhibitor (MRTX1133) plus afatinib. KRAS-G12D PDC (JC117) was exposed to 100 nM of MRTX1133 with or without the indicated concentrations of afatinib for 72 h. Cell viability was detected by CellTiter-Glo assay, and relative cell viability to non-treated conditions was measured. d, e Immunoblotting analysis of the KRAS inhibitor plus afatinib. JC288 and JC117 cells were treated with sotorasib or MRTX1133 for the indicated time. Cell lysates were immunoblotted to detect the indicated antibodies (left).

Therapeutic efficacy of KRAS inhibitor with EGFR antibody in a 3D co-culture system and in vivo

Regarding feedback adaptation reports, we hypothesized that our PDCs could also be characterized into an EGFR feedback group. To explore the efficacy of combining the anti-EGFR antibody (cetuximab) with the KRAS-G12C inhibitor (sotorasib) beyond 2D culture conditions, we assessed cell viability using a 3D co-culture model that mimics tumor tissue with stromal tissues and cancer cells layered as well as in vivo xenograft models20,21. In the PDC (JC288) partially sensitive to sotorasib, a single treatment with sotorasib was ineffective, but sotorasib with cetuximab treatment markedly inhibited cell viability in the 3D coculture model (Fig. 3a). We then evaluated the antitumor efficacy of sotorasib-combined cetuximab in a PDC-xenograft model. Compared with the single sotorasib treatment, the combination therapy significantly suppressed tumor growth while preserving body weight (Fig. 3b). These results indicated that the 3D co-culture system showed better recapitulation of in vivo drug efficacy than the 2D culture model, suggesting that its utilization may present a better prediction of in vivo drug efficacy. In addition, we confirmed that feedback reactivation via EGFR was the main cause of the KRAS inhibitor’s intrinsic resistance mechanism in PDCs.

Fig. 3. KRAS-G12C inhibitor with cetuximab combination showed promising effects in PDCs in 3D and in vivo experiments.

a Evaluation of sotorasib plus cetuximab combination efficacy in a 3D culture. b JC288 cells were subcutaneously transplanted into BALB/c nu/nu mice. Once the average tumor volume reached approximately 150 mm3, the mice (N = 4) were treated once daily with sotorasib (100 mg/Kg), or sotorasib plus cetuximab (1 mg/body) for 5 days/week. Data were expressed as the mean ± SD, and the Mann–Whitney U-test was used between the control group and the sotorasib plus cetuximab group.

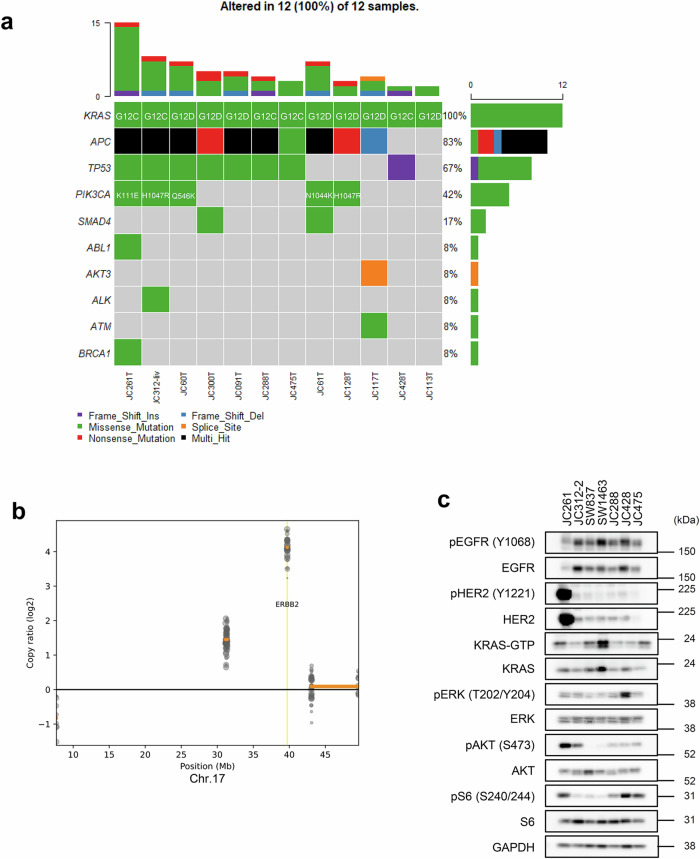

Genomic profiling revealed PI3K mutation and Her2 amplification in the PDCs resistant to KRAS–EGFR inhibition

To identify other resistance mechanisms to KRAS inhibitors besides EGFR reactivation and new therapeutic targets, we focused on PDCs exhibiting high resistance to KRAS–EGFR inhibitor combination therapy. Among these resistant PDCs, JC261 showed marked resistance to the combination therapy, both in vitro and in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 2a and 2c). Despite harboring KRASG12C mutation, JC261 seemed to present exclusive independence on KRAS for its viability (Fig. 1a and d). Therefore, to investigate the genomic aberration in the KRAS-mutated PDCs, target sequencing analysis was performed using 12 surgically resected CRC tumors and normal paired samples with KRAS-G12C or -G12D mutations (Fig. 4a). APC and TP53 mutations were found in 83% and 67% of all samples, respectively. Following these genes, the PIK3CA mutation was the third most frequently mutated in KRAS-mutated CRC samples, including JC261. To gain deeper insights into the genetic alterations, including gene amplification in JC261, target-sequencing data were analyzed. Copy number variation analysis revealed ERBB2 amplification on chromosome 17 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 3a, 3b). Compared with the normal sample, Erbb2 was 16-fold amplified. DNA sequencing analysis identified APC, TP53, KRAS, and ERBB2 gene alterations in JC261. Furthermore, immunoblot analysis was performed to confirm the expression and activation of molecules in the Her2 and PI3K signaling pathways. Extremely high expression levels of total Her2 and phosphorylated Her2, and relatively high level of phosphorylated AKT were detected in JC261 cells compared with the other KRAS-mutated PDCs (Fig. 4c). These data suggested that Her2 amplification and PIK3CA mutation primarily contributed to resistance to sotorasib through the continuous activation of Her2-PI3K signaling in JC261.

Fig. 4. Her2-PI3K pathway gene alterations were detected in KRAS-G12C inhibitor plus cetuximab combination-resistant PDCs.

a Genomic profiling of KRAS-mutated PDCs. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was purified from surgically resected clinical samples, and NGS was executed using 108 cancer-related gene-focused libraries. OncoPlot revealed alterations of the indicated gene (left) in each sample (bottom). b CNV alterations of JC261 cells. The copy ratio was analyzed by CNVkit using target re-sequencing data in Fig. 4a and visualized in the ERBB2 region. c Confirmation of Her2 expression and PI3K signaling. Cell lysates were immunoblotted to detect the indicated antibodies (left).

Triple inhibition of PI3K, mTOR, and KRAS-G12C robustly induced apoptosis in Her2amp, PI3K, and KRAS-mutated-positive PDCs

In addition to genomic profiling, inhibitor library screening of JC261 revealed its vulnerability to PI3K and mTOR inhibition by BEZ235 (PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitor). Therefore, the efficacy of PI3K and/or mTOR inhibition against the cell viability of JC261 was investigated. To inhibit PI3K and/or mTOR, the cell viability of JC261 cells was evaluated by treatment with BEZ235, GDC0941, a PI3K inhibitor, and PP242, an mTOR inhibitor. Pharmacological analysis revealed that a single treatment with BEZ235 or GDC0941 plus PP242 combination significantly reduced cell viability (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, adding sotorasib to BEZ235 or GDC0941 in combination with PP242 intensively inhibited the cell viability of JC261 cells. Next, we assessed cell viability by PIK3CA-specific silencing with/without mTOR inhibition. The cell viability assay indicated that PIK3CA silencing and mTOR inhibition markedly suppressed cell viability more than single PIK3CA silencing in JC261, but not in JC288 (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). To confirm the PI3K signaling alterations in the PI3K pathway inhibitor treatment, we performed immunoblot analysis. The single treatment of GDC0941 or PP242 resulted in a 24-h abrogation of p-AKT and p-S6 levels but failed to induce PARP cleavage (Fig. 5c). In contrast, dual inhibition of PI3K and mTOR resulted in decreased p-AKT and p-S6 levels and the accumulation of PARP cleavage. In addition, triple inhibition of PI3K, mTOR, and KRAS-G12C suppressed p-AKT and pS6 levels, leading to a greater suppression of p-mTOR and accumulation of cleaved PARP than dual inhibition of PI3K and mTOR. These results indicated that dual inhibition of PI3K and mTOR is necessary to suppress cell viability, but incorporating sotorasib treatment can induce robust apoptosis. Consistently, cell viability of JC261 was significantly suppressed by PI3K and mTOR inhibition, and additive growth suppression was observed by adding sotorasib, indicating that PIK3CA and mTOR inhibition with KRAS-G12C inhibition significantly suppressed cell viability more than PI3K and mTOR inhibition in JC261 (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5. Efficacy of dual inhibition of PI3K and mTOR in PIK3CA, ERBB2-amplified KRAS-G12C PDC.

a Pharmacological analysis of PI3K pathway inhibitors in JC261 cells. The cells were treated with the indicated 1 µM inhibitors with or without 1 µM of sotorasib for 72 h. Cell viability was analyzed by CellTiter-Glo assay, and the relative cell viability to DMSO treatment was calculated. Data were shown as mean ± SD. b Cell viability analysis of PI3K knockdown and mTOR inhibition. 20 nM of each siRNA was introduced to cells for 48 h. The cell viability was analyzed using the CellTiter-Glo assay, and the relative cell viability to si-control treated condition was calculated. Data were shown as mean ± SD. c Immunoblotting analysis of PI3K, mTOR, and KRAS inhibition. JC261 cells were incubated with the indicated inhibitors. Cell lysates were collected at each time point and immunoblotted to detect the indicated antibodies (left). d Sensitivity to BEZ235 with or without sotorasib (upper) or PP242 with or without GDC0941 and sotorasib in JC261 cells. The cells were treated with the serially diluted BEZ235 or PP242 and the indicated concentration of GDC0941 and sotorasib for 3 days.

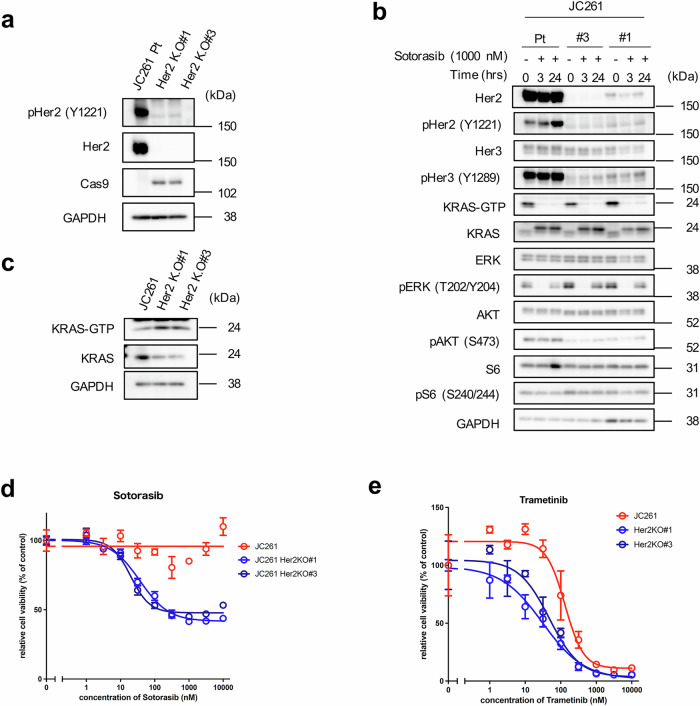

Her2 amplification conferred resistance to the KRAS inhibitor

Then, the mechanisms underlying JC261 cells’ dependence on the PI3K pathway rather than on the MAPK pathway was investigated, although JC261 harbors KRASG12C mutation. Immunoblot analysis revealed that JC261 had a higher relative signal intensity of p-AKT/total AKT level than PIK3CAH1047R-mutated KRASG12C-positive PDC (JC312-2) (Fig. 4c). Moreover, previous studies indicated that PIK3CAK111E mutation activated p-AKT more significantly than PIK3CAWT in USO2 osteosarcoma cell models22. However, p-AKT levels were not as elevated as those in PIK3CAH1047R (a well-known hotspot mutation). Collectively, Her2 amplification may have contributed to high PI3K axis activation and the dependency of JC261 cell viability on PI3K/mTOR. Therefore, we introduced two individual guide RNAs (gRNA) and established Her2 knockout JC261 cell lines (Her2 KO#1, Her2 KO#3) (Fig. 6a). Immunoblot analysis revealed that Her2 KO resulted in reduced total and phosphorylated Her2 expression while suppressing p-Her3 and p-AKT levels in both Her2 KO cells (Fig. 6b). In contrast, p-ERK levels were upregulated in Her2 KO cells compared with parental JC261 cells. These results suggest that Her2 KO induced Her2-Her3-PI3K pathway downregulation and p-ERK activation. To clarify whether p-ERK upregulation was elicited by KRAS activation, we assessed the amount of GTP form of KRAS in parent and Her2 KO cells. Active RAS pull-down assay demonstrated that GTP-KRAS was slightly upregulated in Her2 knockout cells, and completely suppressed by sotorasib treatment for 3 to 24 hr (Fig. 6b and c). As the KRAS–MAPK pathway seemed to be activated in Her2 knockout cells, we evaluated their sensitivity to sotorasib. Long-term cell proliferation assay showed that Her2 knockout cells recovered sensitivity to sotorasib (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig 5). In addition, Her2 knockout cells were more sensitive to MEK inhibitor trametinib than parental JC261 cells (Fig. 6e). These data indicated that the PI3K dependency and resistance to the KRAS inhibitor was mainly attributed to Her2 amplification in JC261 and that the dependency of the survival pathway transferred to the KRAS–MAPK pathway by Her2 knockout.

Fig. 6. Her2 knockout induced suppression of the Her2-Her3-PI3K pathway and recovered sensitivity to sotorasib.

a Certification of Cas9-mediated Her2 knockout. JC261 cells transduced sgHer2 and established Her2 knockout (KO) cell lines. Cell lysates were collected to perform immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. b Comparison of KRAS downstream signaling between JC261 parent cells and Her2 KO cells in KRAS-G12C inhibition. Cells were exposed to 1 µM of sotorasib each time; cell lysates were then collected and immunoblotted to detect the indicated antibodies. c Evaluation of GTP-KRAS by Ras pull-down assay. Cell lysates were collected, and Ras pull-down assay was performed to detect GTP-KRAS. d Sensitivity to sotorasib in Her2 KO cells. The cells were treated with each concentration of sotorasib for 6 days. e Sensitivity to trametinib in Her2 KO cells. The cells were treated with each concentration of trametinib for 6 days. Cell viability was calculated by CellTiter-Glo assay, and relative cell viability to nontreatment conditions was calculated. Data were shown as mean ± SD.

KRAS was localized at the cytoplasm in Her2-amplified PDCs

We then sought to determine how the Her2 knockout upregulated the activity of the KRAS–MAPK pathway. As plasma membrane localization of KRAS is crucial for its catalytic activity, we focused on KRAS localization and performed immunofluorescence staining to evaluate intracellular KRAS localization23. Notably, immunofluorescence staining of KRAS in JC261 demonstrated that KRAS was mainly localized at the cytoplasm in parental JC261 cells, while its localization changed to the plasma membrane in Her2 knockout cells (Fig. 7a). To confirm whether aberrant KRAS localization was exclusive to JC261 cells, we performed immunofluorescence staining of KRAS in other driver oncogene-positive cell lines. In SW48 CRC cells harboring EGFR-activating mutation, and JC288, a KRAS-G12C-positive PDC, KRAS was observed in the plasma membrane (Fig. 7b). In contrast, KRAS was localized at the cytoplasm in JC69 cells, a Her2-amplified KRAS WT PDC. These results suggested that Her2 amplification may trigger aberrant KRAS localization, resulting in low dependency and sensitivity to the KRAS–MAPK pathway.

Fig. 7. KRAS was mainly localized at the cytoplasm in Her2-positive CRC.

a, b Immunofluorescence analysis of KRAS in various cell lines. Representative immunofluorescence images are shown for KRAS (red), E-cadherin, p-Her214, and Hoechst (blue). Scale bar: 20 μm. c Graphical image of Her2-amplified-mediated KRAS localization in this study.

Discussion

The mutant KRAS gene has recently become a targetable oncogene, which can be achieved by directly inhibiting KRAS-G12C with several covalent inhibitors or G12D with non-covalent inhibitor(s). In addition, pan-KRAS inhibitors have been developed and are awaiting future clinical validation. However, KRASG12C inhibitors’ clinical trials have revealed clinical efficiency variations between patients with KRAS G12C-positive NSCLC and those with CRC. EGFR, PI3K, mTOR, or CDK4/6 have been implicated in adaptive resistance to KRAS inhibitors14,15,17,24. Although co-targeting KRAS inhibitors with these inhibitors resulted in an enhanced antitumor effect in NSCLC or PDAC models, further investigation is needed to understand the resistance mechanisms to KRAS inhibitors in CRC. In this study, we analyzed our original KRAS G12C and G12D-mutated CRC-PDCs to identify the intrinsic resistance mechanisms to KRAS inhibitors. Consequently, we categorized PDCs into MAPK-reactivation and PI3K-dependent groups regarding pathway activation under KRAS inhibitor treatment. We also provided insights into the aberrant localization of KRAS-conferred intrinsic resistance to the KRAS inhibitor in Her2 amplification-mediated PI3K-dependent CRC.

EGFR-mediated MAPK-reactivation is a common occurrence due to KRAS, BRAF, and MEK inhibitor treatment, resulting in resistance to single MAPK inhibitors in patients with BRAF V600E and KRAS G12C-positive CRC17,19,25. To overcome this primary resistance, clinical trials have evaluated combination therapy of the KRAS-G12C inhibitor (adagrasib) and anti-EGFR antibody (cetuximab) in patients with KRAS-G12C CRC, revealing a markedly improved response rate (46%) compared to the limited rate of adagrasib monotherapy (19%)18. Notably, we also found here that sotorasib or MRTX1133 monotherapy failed to constantly suppress MAPK and PI3K signaling activity, resulting in limited antitumor efficacy in vitro and in vivo. In contrast, afatinib or cetuximab combination therapy triggered the suppression of MAPK-reactivation and PI3K signaling and decreased cell viability, suggesting that the combination strategy could overcome the intrinsic resistance to the KRAS inhibitor in KRAS-G12C and -G12D models. This may also indicate that a combination therapy can prove effective in other KRAS-mutated CRC models, including G13D, G12V, and G12S CRC. In this study, we focused on the combined inhibition of EGFR and mutant KRAS while considering that multiple RTKs can potentially confer resistance to KRAS inhibitors, as previously reported. Therefore, to prevent feedback reactivation via RTK activation, SHP2 or SOS1 could be a co-target for CRC treatment26–29.

Although adagrasib-combined cetuximab treatment markedly showed favorable results in clinical trials, approximately half of the patients with CRC showed resistance to the combination therapy, and the primary resistance mechanisms remain unknown. In this study, we discovered that PIK3CA hotspot mutations with ERBB2 amplification could confer intrinsic resistance to combination therapy in CRC models. PIK3CA mutations are found in 10–20% of CRC cases but are not mutually exclusive with KRAS mutations in CRC30. KRAS and PIK3CA concomitant mutations were found in 26.7% of CRC cases in the MSK-IMPACT study, although our genomic analysis showed 42% due to the small sample size31. In particular, the occurrence of E545K at exon 9 and H1047R at exon 20 is prevalent in cancers, and these mutations can constitutively activate PI3K signaling32,33. Previous reports have shown that PIK3CA mutations can confer acquired resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitor and KRAS G12C inhibitor–cetuximab combination therapy in patients with NSCLC and CRC34–36. We also confirmed that PIK3CA H1047R-mutated KRAS-G12C PDC (JC312-2) presented primary resistance to combination therapy. Although the PIK3CA K111E mutation may induce resistance to combination therapy, the contribution of Her2 amplification seemed to be considerable. PI3K-activating mutations, particularly H1047R, could serve as predictive markers for resistance to both KRAS inhibitor monotherapy and KRAS plus Erbb family inhibitor combination therapy.

In this study, to overcome PIK3CAK111E and Her2amp-positive KRAS-G12C CRC cells, we discovered that triple inhibition of PI3K, mTOR, and KRAS-G12C markedly suppressed cell viability in the in vitro experiment. However, a previous report uncovered severe toxicity when MEK and PI3K inhibitors were used for treatment in patients with RAS and PIK3CA-mutated CRC37. Although BEZ235 showed satisfactory antitumor activity against various cancer types in a preclinical model, poor tolerability and high adverse events were observed in clinical trials38–41. Thus, the challenges associated with dual PI3K and MAPK pathway inhibition persist in clinical settings. Hence, further research is necessary to explore therapeutic strategies capable of overcoming the activation of both MAPK and PI3K pathways in CRC.

Post-translational modification of KRAS plays an important role in KRAS–MAPK pathway activation. In particular, farnesylation at the position 185 cysteine residue results in KRAS anchoring at the plasma membrane, initiating the activation of KRAS and its downstream signaling42. Inhibiting plasma membrane KRAS localization using farnesyltransferase inhibitors suppressed MAPK activity, showing an antitumor effect on cancers driven by KRAS mutations43,44. Intriguingly, we observed that KRAS was mainly localized at the cytoplasm in Her2 amplification with KRAS-G12C mutation-positive cells, and KRAS was localized at the plasma membrane in the Her2 KO cells. However, mRNA expression of farnesyltransferase-related genes remained unchanged between the Her2 amp and Her2 KO cells. Thus, Her2 amplification-mediated aberrant KRAS localization may occur in a farnesyltransferase-independent manner. Moreover, Her2 amplification with KRAS WT cells demonstrated cytoplasmic KRAS localization, suggesting that Her2 mainly affected aberrant KRAS localization. KRAS localization remained unaltered following phosphoryrated-Her2 inhibition by pan-Erbb family inhibitor (afatinib) treatment. These results indicate that KRAS cytoplasmic localization may not necessarily be elicited via downstream signaling of Her2 and that Her2-interacting or -related scaffold proteins may be involved in blocking KRAS anchoring at the plasma membrane. Other than that, Her2–EGFR driven signaling may evoke the other signaling pathway or effector proteins, contributing the intracellular KRAS localization. According to the changing KRAS localization to the plasma membrane by Her2 KO, we detected the activation of KRAS–MAPK signaling and the downregulation of PI3K signaling. These results suggest that cytoplasmic KRAS localization suppresses KRAS–MAPK pathway activity at low levels in JC261. Furthermore, a JC261 in vivo study demonstrated that sotorasib treatment resulted in a faster tumor growth rate than control treatment. Because cytoplasmic KRAS localization suppresses KRAS–MAPK pathway activity at low levels, activating the MAPK pathway by mutant KRAS and the PI3K pathway by PIK3CA mutation with Her2 amplification may be harmful due to too much oncogene signaling45,46. In this study, we identified the alteration in KRAS localization as a resistance mechanism to KRAS inhibitors. This phenomenon may also be associated with resistance to Her2-targeted therapy in patients with Her2 amplification-positive CRC. In such cases, KRAS is presumed to localize in the cytoplasm in Her2-PI3K dependency while shifting to the plasma membrane when KRAS–MAPK signaling is essential for cell survival during Her2-targeted therapy. Thus, KRAS dislocalization may promote resistance to both KRAS inhibitors and other resistance mechanisms.

Future studies should investigate how to directly regulate KRAS localization from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm. Related to this, the intracellular EML4-ALK fusion protein has been shown to recruit RTK adaptor proteins, resulting in the elicitation of cytoplasmic KRAS localization47. This might suggest that exploring cytoplasmic KRAS-interacting proteins could provide better insights into the regulation of KRAS localization. Recent reports indicate that mislocalization of the Scribble protein leads to YAP-mediated MRAS-MAPK activation, causing adaptive resistance to KRAS-G12C inhibitors48. Overall, considering protein localization in the context of adaptive drug resistance mechanisms is crucial.

Unfortunately, owing to infrequence in Her2-amplified CRC cases ( ~ 2 or 3% of CRC) and failure to establish Her2-overexpressed KRAS-G12C cells, we could not identify the detailed mechanism of aberrant KRAS localization. In this study, we discovered several KRAS-mutated PDC cell lines showing intrinsic resistance to KRAS inhibitor-combined EGFR inhibitor treatment. Inhibitor screening and genomic profiling revealed Her2 amplification and PI3K mutation in a resistant PDC, as well as vulnerability to KRAS-G12C, PI3K, and mTOR triple inhibition. Furthermore, we emphasize that cytoplasmic KRAS localization driven by Her2 amplification maintains a low dependency on KRAS–MAPK, leading to intrinsic resistance to KRAS inhibitors. This represents a novel mechanism of resistance. Altogether, the study findings show that KRAS localization may regulate the balance between MAPK and PI3K signaling intensity while providing valuable information for predicting KRAS–MAPK signaling dependency.

Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

KRAS-G12C and -G12D-positive CRC-PDCs and Her2-amplified CRC-PDCs were established from surgically resected tumor specimens. Tumor specimens were provided with informed consent for genetic and cell biological analyses, which were performed following the protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (#2013-1093). KRAS-G12C-positive-PDCs were cultured in DMEM/F-12, GlutaMAX medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 1×STEMPRO hESC SFM (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1.8% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 8 ng/ml bFGF (BPS Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Wako, Osaka, Japan), 10 μM Y-27632 (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA, USA), and Penicillin-Streptomycin-AmphotericinB Suspension (x 1) (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) (ESC + Y medium). G12D-PDCs were cultured in medium containing equal proportions of Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI1640) (Wako) and Ham’s F12 (Wako) with 10% FBS, 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES; Nacalai Tesque), and 1× antibiotic-antimycotic mixed stock solution (Wako). HCT116, GP2d, LS180, and AsPC-1 cells purchased from ATCC were cultured in RPMI1640 with 10% FBS and 100 µg/mL of kanamycin (Meiji Seika Pharma, Tokyo, Japan). H358, SW837, and SW1463 purchased from ATCC were cultured in DMEM low glucose (Wako) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 µg/mL of kanamycin (Meiji Seika Pharma). All cell lines were authenticated.

Reagents

MedChem Express (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) and Shanghai Biochempartner (Shanghai, China) supplied sotorasib. While afatinib was purchased from ChemiTek (Esposende, Portugal), cetuximab was purchased from MERCK (Darmstadt, Germany). BEZ235, GDC0941, and PP242 were purchased from Adooq BioScience (Irvine, CA, USA). Supplementary Table 1 contains detailed information on the inhibitor library screening drugs.

Cell viability assay

Commercial cells were seeded in triplicate into 96-well plates (IWAKI, Shizuoka, Japan) at 3000 cells/well for 24 h. PDCs were seeded in triplicate into 96-well collagen-coated plates (IWAKI, Shizuoka, Japan) at 3000 cells/well for 24 h, after which serially diluted inhibitors were cultured in media for an additional 72 h. Cells were then incubated with CellTiter-Glo assay reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and luminescence was measured using a Tristar LB941 microplate luminometer (Berthold Technologies, La Jolla, CA, USA). To calculate cell viability and the nonlinear regression model with a sigmoidal dose-response curve, we used GraphPad Prism version 8.0 or 9.0 (GraphPad software).

3D cell viability assay

3D layered co-culture system was prepared in our previous paper. In brief, 9.0 × 105 NHDFs and 1.35 × 104 HUVECs were added to a mixture of 150 μL of 0.1 mg/mL heparin/100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) solution and 150 μL of 0.1 mg/mL collagen/acetic acid (pH 3.7) solution, and centrifuged at 1000 ×g for 2 min at room temperature to obtain viscous material. After suspending the obtained viscous material in DMEM culture medium, the suspension was seeded in 96-well cell culture inserts (#7369, Corning Inc.) and centrifuged at room temperature and 400 ×g for 1 min. Then, incubated in a CO2 incubator (37 °C, 5%) for 24 h. Then, 0.5 × 104 or 1.0 × 104 cancer cells were suspended in DMEM culture medium and seeded in 96-well cell culture inserts and incubated in a CO2 incubator (37 °C, 5%) for 7 days.

Then, anticancer drugs or antibodies were added to the cancer co-culture 3D models and incubated for at least 72 h. The effect of the drugs was evaluated by counting the cancer cells as follows. The remaining proliferative cancer cell number was evaluated by measuring a fluorescent intensity by a high-content confocal microscope analysis system (Operetta CLSTM, PerkinElmer Corp.) after immune-fluorescent staining of CK8/18, and Ki67.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were seeded in 6-well or 12-well collagen-coated plates (IWAKI) at 3–5 × 105 cells/well for 24 h, followed by incubation with each concentration of inhibitors. Cell lysates were then collected at the indicated time points by lysis buffer containing 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol (Wako), and 1% SDS (Nacalai Tesque) and boiled at 100 °C for 5 min. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cell lysates were adjusted to 1 µg/µl using lysis buffer, and a 20% volume of sample buffer containing 0.65 M Tris (pH 6.8), 20% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 3% SDS, and 0.01% bromophenol blue was added. Then, 10 μg of each sample was loaded to perform SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting using following antibodies.

Total S6 ribosomal protein (#2217, 1:2000), phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (#5364, 1:2000), total p42/44 ERK/MAPK (#9102, 1:2000), phospho-p42/44 ERK/MAPK (#9101, 1:2000), total AKT (#4691, 1:1000), phospho-AKT (T308) (#2965, 1:1000), phospho-AKT (S473) (#4060, 1:1000), total EGFR (#2646, 1:1000), Her2 (#2165, 1:1000), phospho-Her2 (#2243, 1:1000), Her3 (#12708, 1:1000), phosphor-Her3 (#2842, 1:1000), PI3 Kinase p110α (#4249, 1:1000), poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (#9542, 1:1000), cleaved PARP (#9541, 1:1000), Cas9 (#14697, 1:1000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. phospho-EGFR (Y1068) antibody (GTX132810, 1:1000) was purchased from Gene Tex (Irvine, CA, USA), KRAS antibody (WH0003845M1, 1:1000) was purchased from Sigma (SIGMA ALDRICH, St. Louis, MO, USA) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody (MAB374, 1:10000) was purchased from Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA). For signal detection, ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) and SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fischer Scientific) were used. Amersham Imager 600 (GE Healthcare) or Amersham Imager 800 (GE Healthcare) was used to detect chemiluminescent signals.

Ras pull-down assay

In total 3–5 × 106 cells were seeded in 10 cm collagen-coated dish for 24 h. Sotorasib or MRTX1133 was then treated for an indicated time point. Total proteins were collected using a Ras-Activating Assay Kit (Millipore), and GTP-Ras detection was conducted as follows: Briefly, cell lysates were collected with lysis buffer, protein concentration was measured by BCA protein assay kit, and 500 µg of the protein lysates were incubated with Raf1-RBD agarose beads for 1. The beads were washed with lysis buffer and resuspended SDS sample buffer, after which GTP-Ras proteins were collected by boiling.

siRNA knockdown

Cells were transfected with 20 nM of each siRNA using Lipofectamin RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and OPTI-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For the cell viability assay, cells were seeded in triplicate into 96-well collagen-coated plates at 3000 cells/well and incubated with siRNA mixture for 72 h. Cell viability was measured using the CellTiter-Glo assay reagent (Promega). For immunoblot analysis, cells were seeded at 5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well collagen-coated and incubated with siRNA mixture for 48 h. Cell lysate was collected and analyzed by immunoblotting. The following siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA).

ON-TARGET plus Non-targeting Pool (D-001810-10-05)

UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA,

UGGUUUACAUGUUGUGUGA,

UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCUGA,

UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCCUA

ON-TARGET plus Human KRAS (3845) siRNA (LQ-005069-00-0005)

si-KRAS#1: GGAGGGUUUCUUUGUGUA

si-KRAS pool: GAAGUUAUGGAAUUCCUUU, GAGAUAACACGAUGCGUAU

ON-TARGET plus Human PIK3CA (5290) siRNA (LQ-003018-00-0005)

si-PIK3CA#1: GCGAAAUUCUCACACUAUU

si-PIK3CA#4: GACCCUAGCCUUAGAUAAA

Inhibitor library screening

Cells were seeded in duplicate into 96-well collagen-coated plates at 3000 cells/well for 24 h, after which indicated inhibitors with KRAS inhibitors were co-cultured for an additional 72 h. Subsequently, cell viability was measured using the CellTiter-Glo assay reagent. Relative cell viability to a single treatment of KRAS inhibitors was calculated.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were cultured in a Lab-tec chamber slide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 24 h and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Wako) for 20 min at room temperature. Cells were then permeabilized for 1 h by blocking and permeabilizing buffer containing Blocking One (Nacarai Tesque) and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) with PBS (Wako). Subsequently, the cells were incubated with an antibody solution containing primary antibodies with 0.1% BSA (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.3% Triton-X-100 (Sigma), and PBS (Wako) at 4°C overnight. Cells were washed with PBS three times and incubated with secondary antibody and antibody solution at room temperature for 1 h, followed by Hoechst staining for 10 min. The chamber slide was washed and mounted by mounting media (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were captured with confocal microscopy LSM880 with 60x or 100x objective (Zeiss) and analyzed using ImageJ. The following primary and secondary antibodies were used in immunofluorescence staining: Anti-KRAS (WH0003845M1, SIGMA, 1:1000), E-cadherin (#3195, CST, 1:1000), Her2 (ab214275, Abcam, 1:1000), Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (A11008, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:1000), and Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (A21236, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:1000); Hoechst 33342 (H1399, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:5000).

Establishment of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated Her2 knockout cells

The sgRNA sequence for ERBB2 was designed using CRISPR Knockout Pooled Library (GeCKO v2) and target sequence cloned into LentiCRISPRv2, which was received from Addgene (#52961). Lentivirus mixtures were produced by ViraPower (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using 293FT cells. Cells were infected using a lentivirus-containing medium supplemented with polybrene (8 mg/ml). After 24 h, the infected cells were selected by puromycin (10 µg/ml).

Target sequencing analysis

Genomic DNA was obtained from surgically resected tumor specimens using DNeasy® Blood&Tissue kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). For cancer-related gene-focused sequencing, a Haloplex custom panel was used, and the details are listed in Supplementary Table 2 (illumine, San Diego, CA, USA). Paired-end sequencing was executed in the NovaSeq6000 platform. Illumina adapter sequences and low-quality bases were trimmed using Trimmomatic-0.39 with LEADING:20 TRAILING:20 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:30 MINLEN:4049. Then, passed-reads were mapped onto the human genome (GRCh38/hg38) using HISAT2 (Version 2.1.0) and a BAM file was obtained using SAMtools (Version 1.8)50,51. More than 1% of SNPs and indels were detected from GATK (Version 4.1.8.0) and VarScan (Version 2.4.4)52,53. A graphical image of gene mutations was obtained from maftools54. The BAM file was also used for copy number calling, and a graphical image of Chr17 was obtained from CNVkit (Version 0.9.8).

Exome sequencing analysis

Genomic DNA was obtained from surgically resected tumor specimens using DNeasy® Blood&Tissue kit (QIAGEN). Library preparation was performed using SureSelect Human V6 (illumine, San Diego, CA, USA), and paired-end sequencing NGS was executed in the NovaSeq6000 platform. Illumina adapter sequences and low-quality bases were trimmed using Trimmomatic-0.39 with LEADING:20 TRAILING:20 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:30 MINLEN:4049. Then, passed-reads were mapped onto the human genome (GRCh38/hg38) using HISAT2 (Version 2.1.0) and a BAM file was obtained using SAMtools (Version 1.8)50,51. The BAM file was used for copy number calling, and a graphical image of Chr17 was obtained from CNVkit (Version 0.9.8).

In vivo study

All in vivo studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved and conducted according to the institutional guidelines. 5–10 × 106 cells for JC288 and JC261 cells were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c-nu/nu mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA). After the tumor volumes reached 100–200 mm3, the mice were orally administered (sotorasib) or intraperitoneally administered (cetuximab) for the indicated days. The drugs were dissolved with the following solution: 2 w/v % HPMC (SIGMA ALDRICH) and 1% Tween80 (Nacalai Tesque). Tumor size and body weight were measured more than twice a week. The tumor volume was calculated as 0.5 × length × width2. The mice were sacrificed when tumor volume reached humane endpoint (1000 mm3) by cervical dislocation. Significant differences in tumor volume were calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test with GraphPad Prism version 9.0.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ai Takemoto (JFCR) for the in vivo study and Ms. Akiko Uotu, Ms. Ramu Inoue, and Ms. Mai Suzuki for the preparation of patient derived cells, and Dr. Yosuke Seto for helping NGS analysis. This study was supported in part by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI grant number JP23KJ0562 (to K.M.), and JP22K18383 and JP24K02333 (to R.K.), and the grant from the AMED grant number JP24am0521012s0101, JP24ama221231h0001, JP24ama221210h0003 and JP24ck0106795h0002 (to R.K.) and the grants from the Naito Foundation (to R.K.), Chugai Foundation for Innovative Drug Discovery Science (to R.K.), Mitsubishi Foundation (to R.K), and the grant from Nippon Foundation and Takeda Science Foundation.

Author contributions

K.M., Y.S., S.N., N.F., and R.K. designed the study. K.M., Y.S., Y.N., T.O., Y.T., and R.K. conducted the experiments and collected data. K.M., Y.S., Y.N., T.O., Y.T., S.N. and R.K. analyzed the data. S.N. served as surgery and take informed consent from patients, and collected colorectal surgical specimens. K.M., Y.T., S.N. and R.K. wrote the manuscript. All the authors have provided a critical review of the manuscript. K.M., N.S., N.F., and R.K. prepared research grants for this study.

Data availability

We have deposited the original fastq files in this article to the DNA DataBank of Japan (NBDJ) ; JGAS000767. The original fastq files within the article are available upon reasonable request. All the somatic mutation data from target re-sequence was attached as the Supplementary data.

Code availability

No code or scripts are used in this study.

Competing interests

R. Katayama is an Associate Editor for npj Precision Oncology. R. Katayama received research grants from Chugai, TOPPAN Inc. N. Fujita received research grants from TOPPAN Inc. Yuki Takahashi and Yumi Nomura belong to TOPPAN Inc. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41698-024-00793-6.

References

- 1.Pylayeva-Gupta, Y., Grabocka, E. & Bar-Sagi, D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat. Rev. Cancer11, 761–774 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh, H., Longo, D. L. & Chabner, B. A. Improving prospects for targeting RAS. J. Clin. Oncol.33, 3650–3659 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li, S., Balmain, A. & Counter, C. M. A model for RAS mutation patterns in cancers: finding the sweet spot. Nat. Rev. Cancer18, 767–777 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos, J. L., Rehmann, H. & Wittinghofer, A. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell129, 865–877 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore, A. R., Rosenberg, S. C., McCormick, F. & Malek, S. RAS-targeted therapies: is the undruggable drugged? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.19, 533–552 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostrem, J. M., Peters, U., Sos, M. L., Wells, J. A. & Shokat, K. M. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature503, 548–551 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canon, J. et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature575, 217–223 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallin, J. et al. The KRAS(G12C) inhibitor MRTX849 provides insight toward therapeutic susceptibility of KRAS-mutant cancers in mouse models and patients. Cancer Discov.10, 54–71 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallin, J. et al. Anti-tumor efficacy of a potent and selective non-covalent KRAS(G12D) inhibitor. Nat. Med.28, 2171–2182 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, D. et al. Pan-KRAS inhibitor disables oncogenic signalling and tumour growth. Nature619, 160–166 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong, D. S. et al. KRAS(G12C) inhibition with sotorasib in advanced solid tumors. N. Engl. J. Med.383, 1207–1217 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ou, S. I. et al. First-in-human phase I/IB dose-finding study of Adagrasib (MRTX849) in patients with advanced KRAS(G12C) solid tumors (KRYSTAL-1). J. Clin. Oncol.40, 2530–2538 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adachi, Y. et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is a cause of both intrinsic and acquired resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitor in KRAS G12C-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.26, 5962–5973 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misale, S. et al. KRAS G12C NSCLC models are sensitive to direct targeting of KRAS in combination with PI3K inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 796–807 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown, W. S. et al. Overcoming adaptive resistance to KRAS and MEK inhibitors by co-targeting mTORC1/2 complexes in pancreatic cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 1, 100131 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki, S. et al. KRAS Inhibitor Resistance in MET-Amplified KRAS (G12C) Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Induced By RAS- and Non-RAS-Mediated Cell Signaling Mechanisms. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 5697–5707 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amodio, V. et al. EGFR Blockade Reverts Resistance to KRAS(G12C) Inhibition in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov.10, 1129–1139 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaeger, R. et al. Adagrasib with or without Cetuximab in Colorectal Cancer with Mutated KRAS G12C. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 44–54 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corcoran, R. B. et al. EGFR-mediated re-activation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer Discov.2, 227–235 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suezawa, T. et al. Ultra-Rapid and Specific Gelation of Collagen Molecules for Transparent and Tough Gels by Transition Metal Complexation. Adv Sci (Weinh), e2302637 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Takahashi, Y. et al. In vitro throughput screening of anticancer drugs using patient-derived cell lines cultured on vascularized three-dimensional stromal tissues. Acta Biomater.183, 111–129 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lou, H. et al. Genome Analysis of Latin American Cervical Cancer: Frequent Activation of the PIK3CA Pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 5360–5370 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson, J. H. et al. Farnesol modification of Kirsten-ras exon 4B protein is essential for transformation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA87, 3042–3046 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue, J. Y. et al. Rapid non-uniform adaptation to conformation-specific KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature577, 421–425 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prahallad, A. et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature483, 100–103 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan, M. B. et al. Vertical Pathway Inhibition Overcomes Adaptive Feedback Resistance to KRAS(G12C) Inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 1633–1643 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, C. et al. Combinations with Allosteric SHP2 Inhibitor TNO155 to Block Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 342–354 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hao, H. X. et al. Tumor Intrinsic Efficacy by SHP2 and RTK Inhibitors in KRAS-Mutant Cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther.18, 2368–2380 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofmann, M. H. et al. BI-3406, a Potent and Selective SOS1-KRAS Interaction Inhibitor, Is Effective in KRAS-Driven Cancers through Combined MEK Inhibition. Cancer Discov.11, 142–157 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cathomas, G. PIK3CA in Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol.4, 35 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zehir, A. et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med. 23, 703–713 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, Y. et al. A Pan-Cancer Proteogenomic Atlas of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway Alterations. Cancer Cell31, 820–832.e823 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madsen, R. R., Vanhaesebroeck, B. & Semple, R. K. Cancer-Associated PIK3CA Mutations in Overgrowth Disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 24, 856–870 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao, Y. et al. Diverse alterations associated with resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature599, 679–683 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yaeger, R. et al. Molecular Characterization of Acquired Resistance to KRASG12C-EGFR Inhibition in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov.13, 41–55 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Awad, M. M. et al. Acquired Resistance to KRAS(G12C) Inhibition in Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2382–2393 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pongas, G. & Fojo, T. BEZ235: When Promising Science Meets Clinical Reality. Oncologist21, 1033–1034 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maira, S. M. et al. Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol. Cancer Ther.7, 1851–1863 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serra, V. et al. NVP-BEZ235, a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, prevents PI3K signaling and inhibits the growth of cancer cells with activating PI3K mutations. Cancer Res. 68, 8022–8030 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Temraz, S., Mukherji, D. & Shamseddine, A. Dual Inhibition of MEK and PI3K Pathway in KRAS and BRAF Mutated Colorectal Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci.16, 22976–22988 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Migliardi, G. et al. Inhibition of MEK and PI3K/mTOR suppresses tumor growth but does not cause tumor regression in patient-derived xenografts of RAS-mutant colorectal carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 2515–2525 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simanshu, D. K., Nissley, D. V. & McCormick, F. RAS Proteins and Their Regulators in Human Disease. Cell170, 17–33 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.End, D. W. et al. Characterization of the antitumor effects of the selective farnesyl protein transferase inhibitor R115777 in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Res. 61, 131–137 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baranyi, M., Buday, L. & Hegedus, B. K-Ras prenylation as a potential anticancer target. Cancer Metastasis Rev.39, 1127–1141 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinstein, I. B. & Joe, A. Oncogene addiction. Cancer Res. 68, 3077–3080 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amin, A. D., Rajan, S. S., Groysman, M. J., Pongtornpipat, P. & Schatz, J. H. Oncogene Overdose: Too Much of a Bad Thing for Oncogene-Addicted Cancer Cells. Biomark. Cancer7, 25–32 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tulpule, A. et al. Kinase-mediated RAS signaling via membraneless cytoplasmic protein granules. Cell184, 2649–2664.e2618 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adachi, Y. et al. Scribble mis-localization induces adaptive resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitors through feedback activation of MAPK signaling mediated by YAP-induced MRAS. Nat. Cancer4, 829–843 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siren, J., Valimaki, N. & Makinen, V. Indexing Graphs for Path Queries with Applications in Genome Research. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput Biol. Bioinform11, 375–388 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koboldt, D. C. et al. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics25, 2283–2285 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mayakonda, A., Lin, D. C., Assenov, Y., Plass, C. & Koeffler, H. P. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28, 1747–1756 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

We have deposited the original fastq files in this article to the DNA DataBank of Japan (NBDJ) ; JGAS000767. The original fastq files within the article are available upon reasonable request. All the somatic mutation data from target re-sequence was attached as the Supplementary data.

No code or scripts are used in this study.