Abstract

Surgical site infections (SSIs) are a significant concern following posterior lumbar fusion surgery, leading to increased morbidity and healthcare costs. Accurate prediction of SSI risk is crucial for implementing preventive measures and improving patient outcomes. This study aimed to construct and validate a nomogram predictive model for assessing the risk of SSIs following posterior lumbar fusion surgery. A retrospective study was conducted on 1015 patients who underwent posterior lumbar fusion surgery at our hospital from January 2019 to December 2022. Clinical data, including patient demographics, comorbidities, surgical details, and postoperative outcomes, were collected. SSIs were defined based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria. Univariate analysis identified significant risk factors, which were then included in a binary logistic regression to develop the nomogram. The model’s performance was evaluated using the concordance index (C-index), calibration curves, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The incidence of SSIs was 5.02% (51/1015). The most common pathogens were Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Significant risk factors for SSIs included smoking history, diabetes, surgery duration ≥ 3 h, intraoperative blood loss ≥ 300 ml, ASA classification ≥ 3, postoperative closed drainage duration ≥ 5 days, incision length ≥ 10 cm, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and the presence of internal fixation. The nomogram demonstrated a C-index of 0.779 and an AUC of 0.845, indicating high predictive accuracy. The calibration curve closely matched the ideal curve, confirming the model’s reliability. The constructed nomogram predictive model demonstrated high accuracy in predicting SSI risk following posterior lumbar fusion surgery. This model can aid clinicians in identifying high-risk patients and implementing targeted preventive measures to improve surgical outcomes.

Keywords: Surgical site infections, Posterior lumbar fusion surgery, Nomogram predictive model, Risk factors, Receiver operating characteristic curve

Subject terms: Bone, Risk factors

Introduction

Posterior lumbar fusion surgery (PLFS) is a widely performed procedure to treat various spinal conditions, including degenerative disc disease, spondylolisthesis, and spinal stenosis. This surgical technique involves the fusion of two or more vertebrae in the lower spine to provide stability and alleviate pain1–3. Despite its effectiveness, PLFS is associated with several postoperative complications, among which surgical site infections (SSIs) are particularly concerning due to their impact on patient outcomes, prolonged hospital stays, and increased healthcare costs. SSIs are infections that occur at or near the surgical incision within 30 days of the procedure or within one year if an implant is placed4,5. The incidence of SSIs following PLFS generally ranges from 1 to 5%, with variations based on patient characteristics and surgical factors. Recent studies have shown that adopting care bundles, which include measures like antibiotic prophylaxis and enhanced aseptic techniques, can significantly reduce the incidence of SSIs, such as decreasing the rate from 3.8 to 0.7% (P < 0.01)6. The occurrence of SSIs can lead to severe consequences, such as the need for additional surgeries, long-term antibiotic therapy, and even chronic pain or disability7,8.

Identifying and understanding the risk factors for SSIs following PLFS is crucial for developing strategies to minimize their occurrence. Various patient-related and procedure-related factors have been implicated in the development of SSIs. Patient-related risk factors include advanced age, obesity, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, smoking, and immunosuppression. Procedure-related risk factors encompass the duration of surgery, blood loss, the extent of tissue dissection, and the use of instrumentation9,10. Additionally, environmental factors such as operating room sterility and adherence to aseptic techniques play a significant role. In recent years, predictive modeling has emerged as a valuable tool in clinical practice to estimate the risk of adverse outcomes and guide decision-making. Nomograms, a form of predictive model, are graphical representations that incorporate multiple variables to provide a personalized risk assessment. By integrating patient-specific factors and clinical data, nomograms can offer individualized risk predictions that are more accurate than traditional risk stratification methods11,12. These models are particularly useful in the context of SSIs, where the interplay of numerous risk factors necessitates a comprehensive assessment to identify patients at high risk and implement targeted preventive measures.

This study aims to construct and validate a nomogram predictive model for assessing the risk of SSIs following PLFS. By accurately predicting the likelihood of SSIs, this model can aid clinicians in identifying high-risk patients, optimizing perioperative management, and ultimately improving surgical outcomes.

Methods

Study design

A retrospective evaluation was conducted at our hospital to assess the risk factors leading to surgical site infections (SSIs) in individuals who underwent posterior lumbar fusion surgery. The timeframe of this inquiry extended from January 2019 to December 2022. A total of 1015 patients who underwent posterior lumbar fusion surgery were included in the study. The research methodology, intent, and protocols were meticulously designed in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines to ensure the highest standards of observational research13. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). The methodology, objectives, and protocols of this study were rigorously reviewed and approved by our hospital’s ethics committee. All procedures were conducted in strict adherence to relevant guidelines and regulations. This research was designed, executed, and reported in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research involving human subjects. Confidentiality was maintained rigorously, with all personal identifiers removed from the data prior to analysis to ensure participant privacy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion Criteria:

Age: patients aged 18 years and older.

Surgery Type: Patients who underwent posterior lumbar fusion surgery at our hospital between January 2019 and December 2022.

Documentation: complete medical records, including preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data, are available.

Follow-up: Patients with a minimum follow-up period of 12 months post-surgery to monitor for the development of SSIs.

Exclusion Criteria:

Other Surgical Procedures: Patients who underwent additional or concurrent spinal surgeries other than posterior lumbar fusion during the same hospital admission.

Previous Infections: Patients with pre-existing infections at the surgical site or ongoing antibiotic treatment for any infection at the time of surgery.

Immunocompromised State: Patients with severe immunocompromised conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, chemotherapy for cancer, long-term steroid use, or treatment with biological agents, which could significantly alter the risk profile for SSIs.

Lost to Follow-up: patients who were lost to follow-up within the 12-month postoperative period.

Clinical data collection

The clinical data of the included patients encompassed basic patient information and medical history, including chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), long-term medication use, coronary artery disease, anemia, cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular diseases, and autoimmune diseases, as well as lifestyle factors like smoking and alcohol consumption. Perioperative Antibiotic Protocol: All patients received a single prophylactic dose of cefuroxime administered within one hour prior to the incision to minimize the risk of surgical site infections. Prophylactic antibiotics were discontinued within 24 h postoperatively, in accordance with established guidelines. No additional intra-wound antibiotics, such as vancomycin powder, were applied. Surgical characteristics were also meticulously recorded: preoperative clinical data included preoperative diagnosis, duration of preoperative hospitalization, history of previous surgeries, preoperative blood glucose levels, preoperative serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, white blood cell (WBC) count, and the type and duration of antibiotic use. Intraoperative clinical data included the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, incision classification, duration of surgery, and intraoperative blood loss. Postoperative clinical data encompassed serum CRP and WBC count on postoperative days 1 and 3, wound status on postoperative day 3 for signs of spontaneous dehiscence, redness, swelling, pain, pus, or exudate, specimen examination, and duration of postoperative closed drainage. Post-discharge data included the length of postoperative hospital stay, discharge date, suture removal date, and the condition of the surgical site after discharge. These comprehensive data points were essential for constructing a predictive model to assess the risk of surgical site infections following posterior lumbar fusion surgery.

Definition of surgical site infections

In accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria for diagnosing SSIs following spinal surgery, and considering the specific characteristics of spinal procedures, postoperative SSIs were comprehensively evaluated based on factors such as surgical site pain, temperature changes, imaging findings, laboratory test results, pathological examination, and wound condition (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Typical manifestations of surgical site infections following posterior lumbar fusion surgery.

Superficial Incisional SSI: Defined as an infection occurring within 30 days postoperatively, involving only the skin or subcutaneous tissue of the incision, and meeting at least one of the following criteria:

The presence of redness, heat, swelling, pain, or purulent drainage from the superficial incision.

A diagnosis of superficial incisional infection made by a clinician.

Deep Incisional SSI: Defined as an infection occurring within one year postoperatively, related to the surgical procedure and involving the deep soft tissues (such as fascia and muscle), meeting at least one of the following criteria:

Purulent drainage from the deep incision but excluding drainage from an organ/space infection

A deep incision that spontaneously dehisces or is deliberately opened by a surgeon when the patient has at least one of the following: fever (> 38 °C), localized pain, or tenderness.

An abscess or other evidence of infection involving the deep incision found on direct examination, during reoperation, or by histopathologic or radiologic examination.

Statistical analysis

Clinical data were analyzed using SPSS software version 22.0. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages (%), and comparisons between groups were made using the chi-squared (χ2) test. Continuous variables that followed a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation (X ± S), and comparisons between groups were performed using the independent samples t-test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To identify risk factors for surgical site infections (SSIs) following PLFS, a binary logistic regression analysis was conducted. Additionally, a nomogram predictive model for assessing the risk of SSIs post-PLFS was developed using the R software version 4.1.3 and the rms package. The predictive performance of the nomogram was evaluated by the concordance index (C-index), calibration curves, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. These measures provided a comprehensive assessment of the model’s accuracy and reliability in predicting SSIs after PLFS.

Results

A total of 1,079 patients were initially screened for eligibility in this study. Of these, 64 patients were excluded for the following reasons: 9 patients had undergone additional or concurrent spinal surgeries during the same hospital admission, 12 patients had pre-existing infections at the surgical site or were receiving antibiotic treatment for other infections (e.g., pulmonary or urinary infections) at the time of surgery, 7 patients were immunocompromised due to conditions such as HIV/AIDS (1 patient) or long-term steroid use (6 patients), and 36 patients were lost to follow-up within 12 months postoperatively. The final cohort comprised 1,015 patients who were then allocated into the Infection Group (n = 51) and the Non-Infection Group (n = 964) for further analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

flowchart of patient selection and allocation process.

Incidence and timing of surgical site infections

Among the 1015 patients who underwent posterior lumbar fusion surgery, 51 developed surgical site infections (SSIs), resulting in an incidence rate of 5.02% (51/1015). Among these 51 patients, 10 (19.61%) exhibited signs of SSIs during their hospital stay, characterized by the presence of abscesses, redness, swelling, heat, and pain at the superficial incision site. Following discharge, 41 patients (80.39%) experienced SSIs, of which 28 presented with fever and exhibited similar signs of redness, swelling, heat, and pain at the incision site. Additionally, 6 patients not only displayed these symptoms but also had purulent drainage. Furthermore, 7 patients had dehiscence of the incision with purulent drainage from the deep tissues. The timing of SSI onset varied among the 51 affected patients. Within the first week postoperatively, 5 patients (9.80%) developed SSIs. Between postoperative days 8 to 14, 10 patients (19.61%) experienced SSIs. The majority of SSIs (31 patients, 60.78%) occurred between 15 and 30 days postoperatively. Lastly, 5 patients (9.80%) developed SSIs more than one month after surgery.

Microbiological profile of surgical site infections

In this study, we analyzed the microbiological profile of purulent discharge samples from 51 patients with SSIs following posterior lumbar fusion surgery. A total of 39 pathogenic isolates were cultured from these samples. Among the 51 patients, 36 (70.59%) had single bacterial infections, while 3 patients (5.88%) had polymicrobial infections. Notably, 12 patients (23.53%) had no bacterial growth in their cultures. The overall pathogen isolation rate was 76.47% (39/51). Of the 39 isolated pathogens, 27 (69.23%) were Gram-positive bacteria. The most frequently isolated Gram-positive organism was Staphylococcus aureus, accounting for 14 isolates (35.90%), including 5 strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Other Gram-positive bacteria included 5 isolates (12.82%) of Staphylococcus epidermidis, 2 isolates (5.13%) of Enterococcus faecalis, 2 isolate (5.13%) of Staphylococcus haemolyticus, and 4 isolates (10.26%) of Staphylococcus capitis. Gram-negative bacteria constituted 12 isolates (30.77%) of the total. These included 1 isolate (2.56%) of Enterobacter aerogenes, 6 isolates (15.38%) of Escherichia coli, 1 isolate (2.56%) of Klebsiella pneumoniae, 2 isolates (5.13%) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and 2 isolates (5.13%) of Acinetobacter baumannii (Table 1).

Table 1.

Microbiological profile of pathogens isolated from surgical site infections.

| Pathogen type | Number of Isolates | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 14 | 35.90 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 5 | 12.82 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 2 | 5.13 |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 2 | 5.13 |

| Staphylococcus capitis | 4 | 10.26 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 | 2.56 |

| Escherichia coli | 6 | 15.38 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 | 2.56 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2 | 5.13 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 2 | 5.13 |

Comparison of clinical characteristics between infection and non-infection groups

A univariate analysis was conducted to compare the clinical characteristics between patients with SSIs and those without. The analysis revealed no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05) between the infection and non-infection groups concerning the following variables: age, sex, history of alcohol consumption, hypertension, coronary artery disease, COPD, autoimmune diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, liver diseases, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular events. However, several clinical variables showed statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between the two groups. These variables included BMI, smoking history, ASA classification, anemia, diabetes mellitus, duration of surgery, surgical approach, intraoperative blood loss, presence of internal fixation devices, duration of postoperative closed drainage, and incision length (Table 2). The findings suggest that these factors may contribute to an increased risk of developing SSIs following posterior lumbar fusion surgery.

Table 2.

Comparison of general data, basic diseases and surgical characteristics between the two groups.

| Characteristic | Infection group (n = 51) | Non-infection group (n = 964) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 65 years | 35 | 560 | 2.361 | 0.125 |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 16 | 404 | - | - |

| Male | 23 | 470 | 0.391 | 0.532 |

| Female | 28 | 494 | - | - |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 6 | 35 | 9.874 | 0.002 |

| BMI < 30 | 45 | 929 | - | - |

| History of alcohol consumption | 7 | 112 | 0.838 | 0.360 |

| No history of alcohol consumption | 44 | 852 | - | - |

| Smoking history | 21 | 221 | 11.279 | 0.001 |

| No smoking history | 30 | 743 | - | - |

| ASA grade ≥ 3 | 21 | 163 | 29.823 | 0.000 |

| ASA grade < 3 | 30 | 801 | - | - |

| Hypertension | 11 | 226 | 0.079 | 0.779 |

| No hypertension | 40 | 738 | - | - |

| Diabetes | 18 | 191 | 10.616 | 0.001 |

| No diabetes | 33 | 773 | - | - |

| Anemia | 4 | 38 | 3.902 | 0.025 |

| No anemia | 47 | 926 | - | - |

| Coronary artery disease | 2 | 22 | 0.922 | 0.147 |

| No coronary artery disease | 49 | 942 | - | - |

| COPD | 1 | 5 | 0.232 | 0.139 |

| No COPD | 50 | 959 | - | - |

| Autoimmune diseases | 2 | 8 | 1.442 | 0.219 |

| No autoimmune diseases | 49 | 956 | - | - |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 1 | 12 | 0.187 | 0.658 |

| No cerebrovascular diseases | 50 | 952 | - | - |

| Liver diseases | 8 | 107 | 0.976 | 0.319 |

| No liver diseases | 43 | 857 | - | - |

| Osteoporosis | 7 | 131 | 0.011 | 0.905 |

| No osteoporosis | 44 | 833 | - | - |

| Cardiovascular events | 3 | 85 | 0.109 | 0.721 |

| No cardiovascular events | 48 | 879 | - | - |

| Duration of surgery ≥ 3 h | 23 | 590 | 8.032 | 0.005 |

| Duration of surgery < 3 h | 28 | 374 | - | - |

| Anterior approach | 4 | 670 | 71.101 | 0.000 |

| Posterior approach | 38 | 590 | - | - |

| Combined approach | 9 | 19 | - | - |

| Intraoperative blood loss ≥ 300 ml | 21 | 410 | 19.985 | 0.000 |

| Intraoperative blood loss < 300 ml | 30 | 554 | - | - |

| Internal fixation present | 49 | 858 | 6.438 | 0.011 |

| Internal fixation absent | 2 | 106 | - | - |

| Postoperative closed drainage ≥ 5d | 9 | 60 | 13.877 | 0.000 |

| Postoperative closed drainage < 5d | 42 | 904 | - | - |

| Incision length ≥ 10 cm | 9 | 78 | 8.744 | 0.003 |

| Incision length < 10 cm | 42 | 886 | - | - |

Statistical Notes: For expected counts (T) ≥ 5, Pearson’s χ2 value was used. For expected counts (1 ≤ T < 5), the continuity-corrected χ2 value was used. For expected counts (T < 1), Fisher’s exact test was directly applied.

BMI = Body Mass Index; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for surgical site infections

To identify the risk factors associated with SSIs following posterior lumbar fusion surgery, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis. The independent variables included in this analysis were factors found to be statistically significant in univariate analyses: BMI, smoking history, ASA classification, anemia, diabetes, duration of surgery, surgical approach, intraoperative blood loss, presence of internal fixation, duration of postoperative closed drainage, and incision length. The occurrence of SSI was set as the dependent variable. The logistic regression analysis identified several significant risk factors for SSIs (P < 0.05). These included smoking history, diabetes, surgery duration ≥ 3 h, intraoperative blood loss ≥ 300 ml, ASA classification ≥ 3, postoperative closed drainage duration ≥ 5 days, incision length ≥ 10 cm, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and the presence of internal al fixation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with postoperative complications.

| Variables | Regression coefficient (B) | Standard error (SE) | Wald value | P Value | Odds ratio (OR) | 95% confidence interval (CI) lower limit | 95% confidence interval (CI) upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal fixation | 1.011 | 0.558 | 3.281 | 0.037 | 2.747 | 1.920 | 8.200 |

| History of smoking | 1.005 | 0.301 | 3.704 | 0.044 | 2.786 | 1.989 | 4.223 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.193 | 0.307 | 15.061 | 0.000 | 3.297 | 1.805 | 6.023 |

| Body mass index | 0.831 | 0.286 | 8.426 | 0.004 | 2.296 | 1.310 | 4.024 |

| Incision length | 0.737 | 0.287 | 6.586 | 0.010 | 2.090 | 1.190 | 3.671 |

| ASA classification | 1.055 | 0.300 | 12.397 | 0.000 | 2.872 | 1.596 | 5.166 |

| Surgery duration | 1.135 | 0.637 | 3.170 | 0.035 | 3.110 | 2.892 | 10.843 |

| Postoperative drain duration | 0.995 | 0.474 | 4.400 | 0.036 | 2.705 | 1.067 | 6.855 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 1.127 | 0.439 | 6.588 | 0.010 | 3.088 | 1.305 | 7.303 |

Construction of a nomogram predictive model for SSI risk

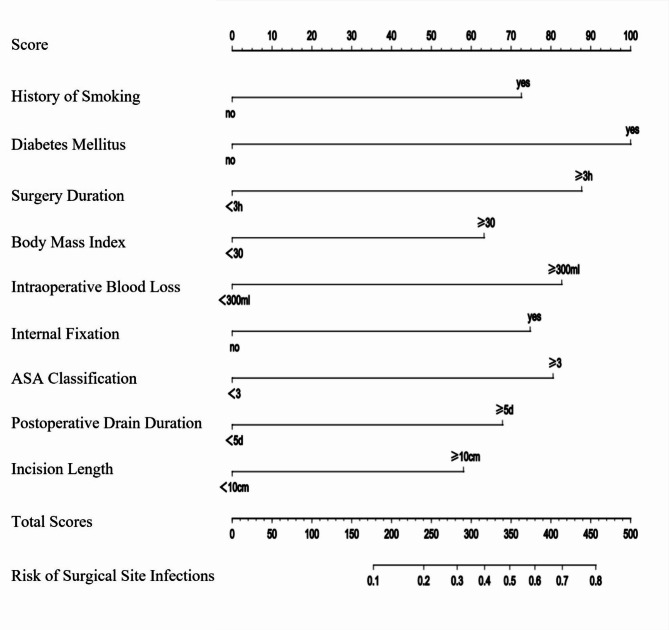

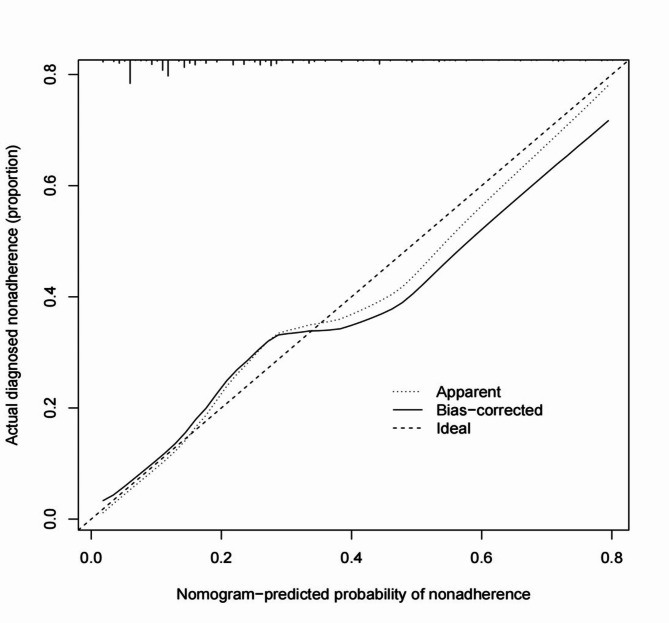

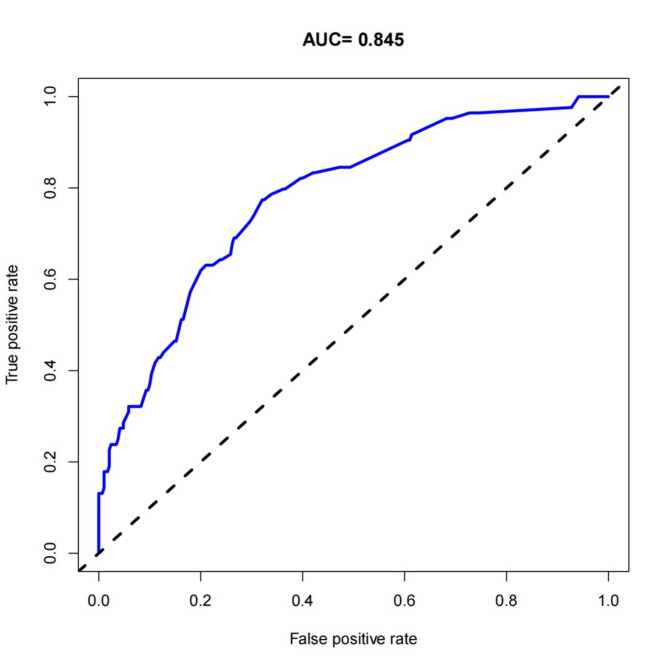

To predict the risk of SSIs following posterior lumbar fusion surgery, a nomogram predictive model was constructed using the nine identified risk factors. These factors included smoking history, diabetes, surgery duration ≥ 3 h, intraoperative blood loss ≥ 300 ml, ASA classification ≥ 3, postoperative closed drainage duration ≥ 5 days, incision length ≥ 10 cm, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and the presence of internal fixation. The nomogram model, depicted in Fig. 3, assigns a total score ranging from 180 to 455 points, corresponding to an SSI probability of 0.1 to 0.8. The performance of the model was evaluated using several metrics. The concordance index (C-index) was 0.779, with a 95% CI of 0.741 to 0.824, indicating a good level of discrimination. Additionally, the calibration curve closely matched the ideal curve, demonstrating the model’s accuracy in predicting SSI risk (Fig. 4). The AUC for the nomogram was 0.845, further confirming the model’s strong predictive capability (Fig. 5). These results validate the effectiveness of the nomogram in assessing the risk of SSIs in patients undergoing posterior lumbar fusion surgery, providing clinicians with a reliable tool for individualized risk stratification and management.

Fig. 3.

Nomogram predictive model for SSI risk following posterior lumbar fusion surgery. The nomogram displayed in this figure predicts the probability of surgical site infections (SSIs) following posterior lumbar fusion surgery (PLFS) based on nine significant risk factors. Each variable is assigned a score, with the total score calculated by summing the points corresponding to the patient’s specific characteristics. The total score ranges from 180 to 455, translating to an SSI probability between 0.1 (10%) and 0.8 (80%). For example, a total score of 180 points indicates an estimated SSI probability of 10%, while a score of 455 points indicates an SSI probability of 80%. This tool aids clinicians in assessing SSI risk, allowing for more personalized patient management.

Fig. 4.

Calibration curve for the nomogram predictive model of SSI risk. This calibration curve assesses the predictive accuracy of the nomogram model for estimating the probability of surgical site infections (SSIs) following posterior lumbar fusion surgery. The x-axis represents the probability of SSI as predicted by the nomogram, while the y-axis shows the actual observed proportion of SSI occurrence in the study population.

The “Ideal” line (dashed) represents perfect agreement between predicted and observed probabilities. The “Apparent” line (dotted) reflects the nomogram’s predictive performance without correction, and the “Bias-corrected” line (solid) represents the model’s performance after internal validation via bootstrapping. The close alignment of the bias-corrected line to the ideal line indicates that the nomogram accurately predicts SSI risk, demonstrating good calibration and supporting its reliability as a clinical tool for risk stratification.

Fig. 5.

ROC curve for the nomogram predictive model. This ROC curve demonstrates the diagnostic performance of the nomogram predictive model for assessing the risk of surgical site infections (SSIs) following posterior lumbar fusion surgery. The x-axis represents the false positive rate (1 - specificity), and the y-axis represents the true positive rate (sensitivity). The area under the curve (AUC) is 0.845, indicating strong discriminative ability, meaning there is an 84.5% chance that the model will correctly distinguish a randomly selected patient who developed an SSI from one who did not. The high AUC value reflects the model’s effectiveness as a predictive tool for SSI risk stratification, supporting its use in clinical practice for accurate SSI risk assessment. The dashed diagonal line represents a random classifier (AUC = 0.5), while the blue line shows the performance of our model.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to construct and validate a predictive nomogram model for assessing the risk of SSIs following PLFS. This predictive tool is designed to aid clinicians in identifying high-risk patients, facilitating personalized perioperative management, and potentially improving surgical outcomes14,15. Our research uniquely concentrates on identifying specific risk factors associated with SSIs to support clinical risk stratification and targeted preventive strategies. The novelty of this study lies in the development of a nomogram that integrates multiple clinically relevant factors, including patient comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, smoking history), surgical characteristics (e.g., duration of surgery, intraoperative blood loss, use of internal fixation), and procedural specifics (e.g., incision length, ASA classification, postoperative drainage duration). This comprehensive model provides a practical tool that enables precise SSI risk prediction in PLFS patients and can be applied in diverse clinical settings to optimize surgical planning and postoperative care16,17. Regarding the scope of PLFS in our study, “Posterior Lumbar Fusion Surgery” is used as a general term encompassing various posterior lumbar fusion techniques. Detailed treatment data for each patient were not collected, we offer a brief overview of the standard management approach for SSIs at our institution. For cases diagnosed with SSIs, treatment typically involves surgical wound debridement, re-suturing in the operating room, and intravenous antibiotic therapy based on susceptibility testing. For patients lacking specific susceptibility results, empirical treatment often includes third-generation cephalosporins to cover common pathogens. This study provides a validated, clinically applicable predictive model for SSI risk following PLFS. This tool contributes to the body of knowledge on SSI prevention in spinal surgery by offering a method for early identification of at-risk patients, thus supporting more tailored perioperative strategies to reduce SSI incidence.

The main risk factors identified in this study for SSIs following posterior lumbar fusion surgery include smoking history, diabetes mellitus, prolonged surgery duration, intraoperative blood loss, ASA classification, extended postoperative drainage, large incision length, high body mass index (BMI), and the presence of internal fixation devices. One of the primary risk factors was smoking history. Smoking impairs wound healing and increases infection risk due to vasoconstriction and reduced immune response, highlighting the importance of smoking cessation in preoperative care. Diabetes mellitus emerged as another significant predictor. Hyperglycemia impairs neutrophil function and promotes bacterial growth, making perioperative glucose control crucial for reducing SSI risk18,19. Surgery duration ≥ 3 h was associated with a higher SSI risk20,21, as prolonged procedures increase tissue exposure to contaminants and trauma22. Minimizing surgery time and handling tissues carefully may help mitigate this risk. Intraoperative blood loss ≥ 300 ml was also significant, as blood loss can lead to hypovolemia and the need for transfusions, which may have immunomodulatory effects increasing infection susceptibility23.

ASA classification ≥ 3, reflecting poorer preoperative health, was identified as a predictor24, emphasizing the importance of optimizing patient health before surgery25,26. Postoperative drainage duration ≥ 5 days posed a risk for SSIs, as prolonged drainage can serve as a bacterial entry point27. Minimizing drainage duration and ensuring proper wound care are critical for postoperative infection control. Incision length ≥ 10 cm correlated with a higher SSI risk, likely due to greater tissue exposure28. Techniques to limit incision length, where feasible, could reduce this risk. BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 was also a key predictor, as obesity is linked to compromised blood supply in adipose tissue and increased wound complications29,30. Addressing weight management and nutrition preoperatively can improve outcomes for obese patients. Finally, the presence of internal fixation devices was associated with higher SSI risk, as these can serve as a bacterial nidus31,32. Proper aseptic techniques and prophylactic antibiotics are essential during implantation to reduce infection risks33,34.

The nomogram predictive model based on these nine risk factors demonstrated good accuracy with a C-index of 0.779 and an AUC of 0.845. This model provides clinicians with a valuable tool for individualized risk assessment, enabling targeted interventions to reduce SSI incidence and improve patient outcomes. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the stability of the model’s coefficients and overall performance. The original model’s AUC was 0.845, and key predictors such as Smoking History, Diabetes, Surgery Duration, and Incision Length demonstrated consistent scaling. Bootstrap analysis yielded a mean AUC of 0.935 (SD = 0.064), with low to moderate coefficient variability, indicating slight sensitivity to sampling. Excluding 20% of events slightly increased the AUC to 0.878, and coefficients remained largely stable. These findings confirm the model’s robustness and reliability in predicting surgical site infection risk, even with a reduced sample size.

In this study, most patients undergoing PLFS received internal fixation to enhance stability. However, for select cases with inherently stable spines, direct posterior lumbar interbody fusion (DPLIF) was performed. This method involves removing the intervertebral disc and filling the space with bone graft material to achieve fusion, avoiding unnecessary hardware and optimizing outcomes. Our postoperative wound care protocol includes an initial dressing change on the first day, followed by changes every two days, with thorough wound examination at each interval. This approach supports early infection detection, reduces SSI risk, and promotes effective healing. Closed drainage is generally maintained for 2–3 days, depending on fluid volume and characteristics. Extended drainage beyond three days is rare, reserved only for cases requiring extra fluid management. Shorter drainage durations help minimize infection risks while ensuring wound healing and early mobilization, contributing to improved recovery in PLFS patients. This study’s SSI risk nomogram provides essential insights for preoperative risk mitigation. Identifying a high risk of SSI allows clinicians to address modifiable factors, such as controlling diabetes and advising smoking cessation. While the decision to operate on higher-risk patients remains individualized, the nomogram enhances risk counseling by enabling discussions about potential complications and preoperative optimization strategies. By quantifying SSI risk, the model aids in personalized patient management and may improve outcomes through targeted preoperative preparation. The nomogram supports clinical decision-making by facilitating risk discussions, especially for patients with modifiable risks. This tool reinforces the importance of proactive risk reduction, underscoring the value of optimizing modifiable factors to improve patient outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, it is retrospective in nature, which may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the data were collected from a single institution, potentially affecting the model’s applicability to other settings or populations. Third, the study did not account for all possible confounding factors, such as variations in surgical techniques and postoperative care protocols. Future research should prioritize prospective, multicenter studies to validate and improve the nomogram’s predictive accuracy by incorporating a broader range of clinical and procedural variables, such as bone grafting, as well as genetic and microbiome data. Examining the effects of targeted interventions based on nomogram risk assessments could further enhance patient outcomes and reduce SSI rates in posterior lumbar fusion surgery. These additional factors represent potential unknowns that may enrich the model’s scope and applicability in clinical settings.

Conclusions

The incidence of surgical site infections (SSIs) following posterior lumbar fusion surgery was 5.02%, with Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli being the most common pathogens. Identified risk factors include smoking history, diabetes, surgery duration ≥ 3 h, intraoperative blood loss ≥ 300 ml, ASA classification ≥ 3, postoperative closed drainage duration ≥ 5 days, incision length ≥ 10 cm, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and the presence of internal fixation. The constructed nomogram predictive model demonstrated high accuracy in predicting SSI risk.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank every patient who participated in this study and every staff member for their efforts.

Author contributions

The overall integrity of this study is guaranteed by J.L. and C.Z. C.Z. conceptualized the study, while Jinzhou Luo was responsible for the study design and defining the intellectual content. Literature research was conducted by J.L., J.L., C.Y., and Q.C. J.L. also handled clinical studies, data acquisition, data analysis, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation, and editing. The manuscript was reviewed by C.Z.

Data availability

Due to the confidentiality agreement of the Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University and the proprietary data owned by the Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, the data sets generated and analyzed during this study are not public, but under reasonable requirements, the correspondence author can provide.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study or from their legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). Patients and/or families in the study provided consent for the publication of their data.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rathbone, J. et al. A systematic review of anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) versus posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), posterolateral lumbar fusion (PLF). Eur. Spine J.32(6), 1911–1926 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu, G. et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of oblique lumbar interbody fusion and posterior lumbar interbody fusion for treatment of cage dislodgement after lumbar surgery. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi34(6), 761–768 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeager, M. S. et al. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion with integrated fixation and adjunctive posterior stabilization: A comparative biomechanical analysis. Clin. Biomech.30(8), 769–774 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie, J. et al. Association between immediate postoperative hypoalbuminemia and surgical site infection after posterior lumbar fusion surgery. Eur. Spine J.32(6), 2012–2019 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freire-Archer, M. et al. Incidence and recurrence of deep spine surgical site infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976)48(16), E269–E285 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada, K. et al. Evidence-based care bundles for preventing surgical site infections in spinal instrumentation surgery. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976)43(24), 1765–1773 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, S. et al. Vancomycin use in posterior lumbar interbody fusion of deep surgical site infection. Infect. Drug Resist.15, 3103–3109 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura, S. et al. Treatment strategy for surgical site infection post posterior lumbar interbody fusion: A retrospective study. J. Orthop.31, 40–44 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan, S. A. et al. Current management trends for surgical site infection after posterior lumbar spinal instrumentation: A systematic review. World Neurosurg.164, 374–380 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu, J. M. et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after posterior lumbar spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976)43(10), 732–737 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ying, H. et al. Incidences and reasons of postoperative surgical site infection after lumbar spinal surgery: A large population study. Eur. Spine J.31(2), 482–488 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pei, H. et al. Surgical site infection after posterior lumbar interbody fusion and instrumentation in patients with lumbar degenerative disease. Int. Wound J.18(5), 608–615 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol.61(4), 344–349 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang, T., Lian, X., Chen, Y., Cai, B. & Xu, J. Clinical outcome of postoperative surgical site infections in patients with posterior thoracolumbar and lumbar instrumentation. J. Hosp. Infect.128, 26–35 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, J. S., Ahn, D. K., Chang, B. K. & Lee, J. I. Treatment of Surgical site infection in posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Asian Spine J.9(6), 841–848 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, J. H., Ahn, D. K., Kim, J. W. & Kim, G. W. Particular features of surgical site infection in posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Clin. Orthop. Surg.7(3), 337–343 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohl, D. D. et al. Malnutrition predicts infectious and wound complications following posterior lumbar spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976)41(21), 1693–1699 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sang, C., Ren, H., Meng, Z. & Jiang, J. Risk factors for surgical site infection following posterior lumbar intervertebral fusion. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao38(8), 969–974 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang, Y. F., Yu, J. C., Xiao, Z., Kang, Y. J. & Zhou, B. Role of pre-operative nutrition status on surgical site infection after posterior lumbar interbody fusion: A retrospective study. Surg. Infect.24(10), 942–948 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang, X., Liu, P. & You, J. Risk factors for surgical site infection following spinal surgery: A meta-analysis. Medicine101(8), e28836 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogihara, S. et al. Risk factors for deep surgical site infection after posterior cervical spine surgery in adults: A multicentre observational cohort study. Sci. Rep.11(1), 7519 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng, H. et al. Prolonged operative duration increases risk of surgical site infections: A systematic review. Surg. Infect.18(6), 722–735 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang, R. et al. Etiological analysis of infection after CRS + HIPEC in patients with PMP. BMC Cancer23(1), 903 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogihara, S. et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after lumbar laminectomy and/or discectomy for degenerative diseases in adults: A prospective multicenter surveillance study with registry of 4027 cases. PLoS One13(10), e0205539 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hikata, T. et al. High preoperative hemoglobin A1c is a risk factor for surgical site infection after posterior thoracic and lumbar spinal instrumentation surgery. J. Orthop. Sci.19(2), 223–228 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taree, A. et al. Risk factors for 30- and 90-day readmissions due to surgical site infection following posterior lumbar fusion. Clin. Spine Surg.34(4), E216–E222 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee, 2018 Ed. (World Health Organization, 2018).

- 28.Sganga, G. et al. Management of superficial and deep surgical site infection: An international multidisciplinary consensus. Updates Surg.73(4), 1315–1325 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He, Z. et al. Perioperative hypoalbuminemia is a risk factor for wound complications following posterior lumbar interbody fusion. J. Orthop. Surg. Res.15(1), 538 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng, S. et al. Association of modic changes and postoperative surgical site infection after posterior lumbar spinal fusion. Eur. Spine J.33(8), 3165–3174 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, Z. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and analysis of risk factors for surgical site infection after lumbar fusion surgery: ≥ 2-year follow-up retrospective study. World Neurosurg.131, e460–e467 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, T. Y., Back, A. G., Hompe, E., Wall, K. & Gottfried, O. N. Impact of surgical site infection and surgical debridement on lumbar arthrodesis: A single-institution analysis of incidence and risk factors. J. Clin. Neurosci.39, 164–169 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, D. R., Yoon, B. H., Ki Park, Y. & Moon, B. G. Significance of surgical first assistant expertise for surgical site infection prevention: Propensity score matching analysis. Medicine102(15), e33518 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaichana, K. L. et al. Risk of infection following posterior instrumented lumbar fusion for degenerative spine disease in 817 consecutive cases. J. Neurosurg. Spine20(1), 45–52 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the confidentiality agreement of the Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University and the proprietary data owned by the Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, the data sets generated and analyzed during this study are not public, but under reasonable requirements, the correspondence author can provide.