Abstract

Coal-burning fluorosis prevails in southwest China and other provinces. Although clay used as binder of briquettes was proven to cause coal-burning fluorosis, its enrichment processes remain unknown. The soils and rocks on typical geological units were sampled and simulation experiments were performed to detect the forming process of high-fluoride clay. The surface and mineral soils, farmland soils and rocks have fluoride levels of 157.9–1076.76, 334.58–1419.28, 227.52–1303.11 and 46.05–964.11 mg/kg respectively. Fluoride levels of surface soils, mineral horizon soils and farmland soils are significantly positively correlated, while those between soils and rocks are not significantly correlated. The soils overlying carbonates have substantially higher fluoride levels than those overlying non-carbonates although the carbonates have extremely lower fluoride levels. The fluoride levels in acid insoluble substances are significantly positively correlated with soil fluoride levels. The acid insoluble substances in carbonates have obviously higher fluoride levels than those in non-carbonates. High Ca(Mg) levels in carbonates restrict fluorine leaching into the water and facilitate fluorine deposition in soils. Fluoride enriches in soils with numerous Ca(Mg)CO3 leaching during carbonate weathering, which is a new insight into the cause of high-fluoride clay. An exposure pathway of fluoride is forwarded. The best prevention principle and policy are proposed.

Keywords: Acid insoluble substance, Carbonate, Coal-burning fluorosis, Fluoride source, Prevention principle, Southwest China

Subject terms: Biogeochemistry, Environmental sciences

Introduction

Fluorine (F) is an essential element for human health, and intake of appropriate fluoride is observed to prevent dental caries. However, the excess intake of fluoride causes chronic fluorosis, typically dental fluorosis and skeletal fluorosis1–4. Blood pressure, fertility, abortion, height and weight, and intelligence are also confirmed to be linked to fluoride in body5. The safe threshold of fluorine intake is very narrow6. 4 mg per day for adults and 2 mg per day for children were recommended as daily maximum allowances by the WHO7. A safe daily fluorine intake of 1.5-4.0 mg per day for adults and that of 1.5–2.5 mg for children are recommended in the USA8. The safe daily intake of < 3.5 mg per day for adults and that of < 2.4 mg per day for children are recommended in China9. Generally, intake of > 6 mg per day may be potentially toxic to the tooth and skeleton10,11.

Fluorosis can be categorized into three main types based on their origins: water-drinking fluorosis, coal-burning fluorosis and tea-drinking fluorosis. Additionally, breast milk, air, food and toothpaste are defined as chronic fluoride exposure routes12,13. Among these, coal-burning fluorosis is a typical type of fluorosis, prevailing in southwest China (northwestern Guizhou Province, northeastern Yunnan Province and southern Sichuan Province). Although the prevalence rate of endemic fluorosis declined recently, enormous local populations were still suffering from fluorosis, and even some new fluorosis areas are occurring14,15. A comprehensive understanding of coal-burning fluorosis is significant for its prevention principles and policies.

It has experienced a long journey regarding the exposure routes and causes of coal-burning fluorosis. Lyth16 first reported a fluorosis case in Shimenkan village of Guizhou Province, and ascribed it to drinking-water fluorosis because he found high fluoride water in two samples (one from a hot spring and one permeating from a coal layer). But this viewpoint was proven to be wrong by subsequent investigations17,18. Open stoves are used to roast peppers and corns in these areas. Since the 1980s, high-fluoride levels were found in these roasted foodstuffs17,19–21. The coals used for food roasting were initially considered to be the exposure routes, and labeled as “coal-burning fluorosis”. However, the later accumulated data realized the fluoride levels in the coal were modest22–24. Briquettes in the open stoves are actually the mixtures of coals and clay. Recent researches found that the clay was truly abundant in fluoride level25–27. The extremely high fluoride levels in the briquettes were verified to be more likely to stem from the clay, rather than from the coal itself, which is strongly supported by recent works15,25,26,28. The enrichment processes of high-fluoride soils in these areas are of great interest and importance for coal-burning fluorosis. But there is still no such information, and the fluoride source in clay remains unknown, which deeply impedes the prevention of fluorosis.

High-fluoride rocks are generally considered to be the primary sources of high-fluorine soils because fluoride mainly originates from fluoride-bearing minerals, such as granite, gneiss, basaltic lava, phosphorus-containing rocks, gypsum-bearing and carbonaceous rocks with high-fluoride levels are widely documented6,12,29–31. Mineral fluoride used as raw materials for extraction of aluminum, ceramics and lubes is also the important contamination sources of fluoride10. Carbonates widely distribute in southwest China, covering about 41.86% of the total area. Carbonates also have low fluoride levels because of the high ratio of Ca(Mg)CO3, and are paid no attention regarding the high-fluoride soils in this area. However, the fluorosis and high-fluoride soils are frequently documented in carbonate areas32–34.

Based on the above mentioned, typical rocks and the overlying soils in Zhengxiong and Weixin County were gathered and analyzed, with the aims to : (1) assess the soil fluoride levels overlying different rocks, and compare the soil fluoride levels in carbonate areas and non-carbonate areas; (2) simulate the fluoride enrichment process during soil-forming process by extraction experiments of acid insoluble substances; (3) discuss the cause of coal-burning fluorosis and its relationship with carbonate weathering; and (4) provide the adaption prevention principle and policy.

Methods and materials

The study area

Zhengxiong and Weixin County were selected as the study area for this research. The area is located at the junction of Guizhou, Sichuan and Yunnan Provinces. The area is a typical karst mountain, with elevations of 480–2416 m and characterized by mountainous, semi-mountainous and alpine mountain areas, without plain areas. The weather is cool and rainy, belonging to a warm-temperate monsoon climate, with an annual temperature of 11–20 °C and an annual precipitation of 600–1200 mm35.

The residents severely suffer from fluorosis. The endemic fluorosis patients in Zhengxiong County occupied 88% of the total population in 2019. 350 thousand residents in 77 villages of 10 towns in Weixin County had fluorosis36. Ji et al.37 even recorded a 100% prevalence of fluorosis in Zhengxiong and Weixin County, with a fluorosis index of 3.49.

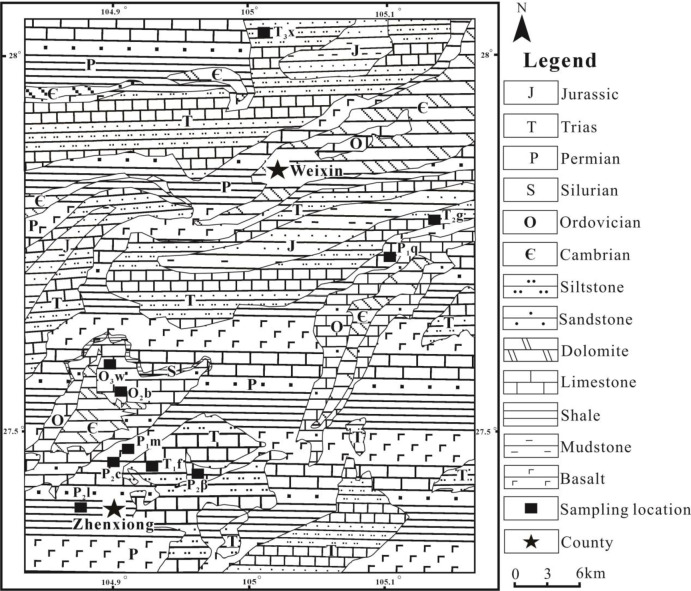

The area is located in the western Yangtze block, belonging to the north Guizhou stratigraphic minor region of the upper Yangtze continent. The area uplifted during the Devonian-Early Permian period. The widely exposed strata in this area mainly include the Ordovician, Permian, Triassic, Jurassic and Quaternary from old to new. Cambrian and Silurian strata sporadically occur on a relatively small scale. The lithologies of the Ordovician, Permian and Triassic are mainly marine carbonates interbedded with silt and coals, and those of the Jurassic and Quaternary are terrestrial clastic deposits (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Geological map and sampling sites (after Chen et al.35).

Sample gathering and analyzing

The soils and rocks were sampled based on different stratigraphic and rock units. The successive relationship between soils and rocks was estimated in field through the grain size, mineral composition, and residual texture. For every rock type, a non-farmland area and its neighbouring farmland area were selected. A surface soil (in the upper 10 cm layer) and a soil in mineral horizon (near the interface with the bedrock (within 10 cm)) in non-farmland area, a surface soil (the upper 10 cm layer) in farmland area, and the underlying rock were sampled, respectively. That is, 3 soil samples and 1 rock sample were taken for each lithological unit. The carbonate and non-carbonate units were both involved. The carbonates included: silty limestone in the Baota Formation of the Mid-Ordovician(O2b), argillaceous limestone in the Wufeng Formation of the Late-Ordovician(O3w), bioclastic limestone in the Maokou Formation of the Early-Permian (P1m), limestone interbedded with shale in the Changxing Formation of the Mid-Permian (P2c), and dolomite in the Guanling Formation of the Mid-Trias (T2g). The non-carbonates included: basalt in the Emeishan Formation of the Mid-Permian(P2β), shale in the Longtan Formation of the Mid-Permian (P2l), siltstone in the Feixianguan Formation of the Early-Trias(T1f), and siltstone and sandstone in the Xujiahe Formation of the Late-Trias (T3x). The samples covered the main stratigraphic and rock units in this area, and the detailed locations were shown in Fig. 1.

The soils and rocks were sent to the lab and dried at room temperature. The samples were ground into particles less than 200 mesh for element analysis. The fluoride levels were determined using combustion-hydrolysis/fluoride selective electrode referencing Feng et al.38. ICP-MS was used to analyze Ca and Mg levels in the soils and rocks using electric heating board digestion according to Fan et al.39.

For quality control, the standard samples (GBW07403 and GSB 07-1194-2000), parallel samples and blank samples were also analyzed, and the relative errors were less than 5%. The accuracy of F, Ca and Mg were evaluated by the recovery test, and the recoveries were between 96.4 and 104.6%. The obtained limits of determination (LOD) were 15.2 mg/kg for F level, 213.6 mg/kg for Ca level, and 192.8 mg/kg for Mg level.

Fluoride-leaching experiment

A 2500 ml beaker was baked at 105 °C for 6–8 h, and weighed after cooling. 1500–2000 mg carbonates or 50–100 mg non-carbonates were placed into the beakers. 1 mol/L HCl was added into every beaker and blended until the solution stopped bubbling. 1 mol/L HCl was repeatedly added to confirm the reaction was complete after the beaker was stewed for 30–40 min. The supernatant was pumped and its volume was recorded after the solution was stewed for one night. 150 ml supernatant was left for further analysis. The residue in the beaker was washed 3–4 times using re-distilled water until the solution was neutral. The beaker was again baked at 105 ℃ for 6–8 h and weighed after cooling. The residue was collected in a plastic bag for further analysis. The fluoride level in the supernatant was determined using a fluoride selective electrode method, and the level in the residue was measured using a combustion- hydrolysis/fluoride selective electrode method.

Statistical analysis

The statistics of average, minimum and maximum were calculated using software Excel 2019. Correlation analysis was done using software IBM SPSS Statistic 22, and correlation coefficient (r) was used to measure correlation degree, with P values less than 0.05 considered.

Results and discussion

Fluoride levels in soils and rocks

The fluoride levels in the soils and rocks are illustrated in Table 1; Fig. 2. The fluoride levels in the surface soils, soils in mineral horizons, farmland soils, and rocks are 157.9-1076.76, 334.58-1419.28, 227.52-1303.11 and 46.05-964.11 mg/kg, with average of 642.48, 727.25, 647.55 and 335.98 mg/kg respectively. Pan et al.40 recorded fluoride levels of 274–3663 mg/kg (1103 mg/kg) in surface soils and 246–3695 mg/kg (1382 mg/kg) in deep soils in Guizhou Province. The survey in 2007–2008 observed a mean soil fluoride level of 929 mg/kg in Guizhou Province41. The soil fluoride levels in this area are slightly lower than those in Guizhou. Yang et al.42 reported fluoride levels of 378.79-1576.13 mg/kg (mean of 648.90 mg/kg) in agricultural soils in southwest China, which is comparable to our investigation.

Table 1.

The F, ca and mg levels in soils and rocks (mg/kg).

| Stratum | Lithology | Non-farmland area | Farmland area | Bedrock | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface soil | Soil in the mineral horizon | Surface soil | |||||||||||

| F | Ca | Mg | F | Ca | Mg | F | Ca | Mg | F | Ca | Mg | ||

| Baota Formation of the Mid-Ordovician (O2b) | Silty limestone | 595.72 | 63,693 | 8490 | 699.55 | 11,492 | 9751 | 468.77 | 28,555 | 9096 | 79.05 | 137,547 | 1785 |

| Wufeng Formation of the Late-Ordovician (O3w) | Argillaceous limestone | 880.44 | 5641 | 12,514 | 1419.28 | 14,083 | 12,933 | 1303.11 | 2462 | 10,634 | 131.45 | 291,528 | 3611 |

| Maokou Formation of the Early-Permian (P1m) | Bioclastic limestone | 585.94 | 6599 | 8373 | 682.37 | 8448 | 10,881 | 322.46 | 12,398 | 14,749 | 74.25 | 258,746 | 2467 |

| Emeishan Formation of the Mid-Permian (P2β) | Basalt | 567.04 | 2300 | 2134 | 476.34 | 8492 | 8858 | 481.4 | 3225 | 2662 | 964.11 | 54,474 | 18,618 |

| Longtan Formation of the Mid-Permian (P2l) | Shale | 433.95 | 823 | 6591 | 480.2 | 2147 | 8232 | 399.7 | 6914 | 16,807 | 648.34 | 1551 | 8425 |

| Changxing Formation of the Mid-Permian (P2c) | Limestone interbedded with shale | 936.09 | 6773 | 12,180 | 1278.01 | 5830 | 12,897 | 1216.95 | 4647 | 18,102 | 121.89 | 192,235 | 3547 |

| Feixianguan Formation of the Early-Trias (T1f) | Siltstone | 157.9 | 1678 | 13,844 | 334.58 | 7334 | 3718 | 227.52 | 5122 | 11,339 | 744.28 | 25,094 | 27,091 |

| Guanling Formation of the Mid-Trias (T2g) | Dolomite | 1076.76 | 2891 | 15,967 | 709.4 | 7372 | 8969 | 880.27 | 2668 | 13,217 | 46.05 | 215,647 | 4382 |

| Xujiahe Formation of the Late-Trias (T3x) | Siltstone and sandstone | 548.5 | 1722 | 10,932 | 465.47 | 4668 | 9125 | 527.81 | 393 | 5103 | 223.44 | 4601 | 5473 |

Fig. 2.

The comparison of fluoride levels in different geological units.

All the samples, except the surface soils overlying T1f siltstone, exceed the world average of soil fluoride level (200 mg/kg). The average soil fluoride level in China is 440 mg/kg43, and all the soils except those overlying T1f siltstone have fluorine levels beyond this value. Li and Wu44 reported an average soil fluoride level of 800 mg/kg in fluorosis areas in China, and the soils overlying O3w argillaceous limestone, P2c limestone interbedded with shale, and T2g dolomite have higher fluoride levels than this average value. According to GB15618-2008, 1000 mg/kg is recommended as the criteria for residential land. The soils in the mineral horizon and farmland overlying O3w argillaceous limestone and P2c limestone interbedded with shale, and surface soil overlying T2g dolomite are beyond this criterion. The soil fluoride levels are generally in the following order: carbonates (including limestone and dolomite) area > basalt area ≈ siltstone and sandstone > shale area > siltstone area. So, it seems that the soils developing from the carbonates are responsible for the fluorosis, especially those from O3w argillaceous limestone, P2c limestone interbedded with shale, and T2g dolomite. However, the fluoride levels in carbonates are only in the range of 46.0-131.45 mg/kg, which is obviously lower than those found in non-carbonates.

There exist significantly positive correlations of fluoride levels between surface soils and soils in the mineral horizon (r = 0.7199, P < 0.01), surface soils and farmland soils (r = 0.8310, P < 0.01), soils in the mineral horizon and farmland soils (r = 0.9185, P < 0.01). However, no significant correlations between soil fluoride levels and rock fluoride levels were observed, indicating the fluoride levels in the rocks themselves can not well explain the soil fluoride levels and fluorosis. Zheng et al.44 also found there were no positive correlations between the fluoride levels in the rocks and in the soils.

The fluoride-leaching of different rocks

The results of the fluoride-leaching simulation experiments are listed in Table 2. The fluoride levels in acid insoluble substances are 402.02-1243.64 mg/kg, with a mean of 759.22 mg/kg. The average in acid insoluble substances is slightly higher than those in the soils, possibly because of the different fluoride amounts leaching from the soils during soil maturation.

Table 2.

The acid-soluble and acid insoluble fluoride levels in different rocks.

| Stratum | Lithology | Percentage of acid insoluble substance (%) | Percentage of acid soluble substance (%) | Fluoride level in acid soluble substance (mg/kg) | Percentage of acid soluble fluoride (%) | Fluoride level in acid insoluble substance (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baota formation of the Mid-Ordovician (O2b) | Silty limestone | 1.93 | 98.07 | 4.71 | 6.72 | 832.34 |

| Wufeng formation of the Late-Ordovician (O3w) | Argillaceous limestone | 2.26 | 97.74 | 9.3 | 7.07 | 1243.64 |

| Maokou formation of the Early-Permian (P1m) | Bioclastic limestone | 1.73 | 98.27 | 14.62 | 19.69 | 995.01 |

| Emeishan formation of the Mid-Permian (P2β) | Basalt | 78.56 | 21.44 | 8.75 | 0.91 | 517.13 |

| Longtan formation of the Mid-Permian (P2l) | Shale | 94.3 | 5.7 | 2.35 | 0.36 | 468.07 |

| Changxing formation of the Mid-Permian (P2c) | Limestone interbedded with shale | 4.84 | 95.16 | 0.8 | 0.66 | 1040.58 |

| Feixianguan formation of the Early-Trias (T1f) | Siltstone | 94.66 | 5.34 | 5.54 | 0.74 | 459.73 |

| Guanling formation of the Mid-Trias (T2g) | Dolomite | 4.61 | 95.39 | 8.85 | 19.22 | 874.48 |

| Xujiahe formation of the Late-Trias (T3x) | Siltstone and sandstone | 91.62 | 8.38 | 28.72 | 12.85 | 402.02 |

All the acid insoluble substances have fluoride levels exceeding the average soil fluoride levels in China (440 mg/kg) except that of T3x siltstone and sandstone. Specifically, O2b silty limestone, O3w argillaceous limestone, P1m bioclastic limestone, P2c limestone interbedded with shale, and T2g dolomite have fluoride levels of > 800 mg/kg in acid insoluble substances. And even fluoride levels in acid insoluble substances of O3w argillaceous limestone, and P2c limestone interbedded with shale are more than 1000 mg/kg, which is in accordance with the overlying soil fluorine levels. While the acid insoluble substances of non-carbonates (basalt, shale, siltstone and sandstone) have relatively lower fluoride levels. Such phenomenon implies fluorine in carbonates excessively enriches in soil during the soil-forming although the carbonates have low fluoride levels, and soils developing from carbonates may be the key to the high-fluoride soils and fluorosis in this area.

The significantly positive correlations (P < 0.01) of fluoride levels in acid insoluble substances with those in surface soils, mineral soils and farmland soils (r = 0.7120, 0.8899 and 0.7264 respectively) (Table 3) indicate the acid insoluble substances deeply govern the soil fluoride levels. No significant correlations between fluoride levels in acid insoluble substances and bedrocks are observed, but fluoride levels in acid insoluble substances and in non-carbonates are significantly positively correlated (r = 0.9421). The soil-forming process in carbonate areas affects soil fluoride levels, together with the fluoride levels itself in rocks.

Table 3.

Correlations of fluoride levels in acid insoluble substances with those in soils and non-carbonates.

| Correlation coefficient | Surface soil | Soil in the mineral horizon | Farmland soil | Non-carbonates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | 0.7120** | 0.8899** | 0.7264** | 0.9421** |

**Indicate correlation at P < 0.01.

The new insight into the cause of high-fluoride soils

Coal-burning fluorosis was documented not only in southwest China, but also in other areas such as Shaanxi, Hunan, Chongqing, Guangxi, and Hubei provinces45,46. It was estimated that 16.1 million dental fluorosis patients and 1.8 million skeletal fluorosis patients due to coal-burning in China were affected15.

Some high-fluoride rocks in these areas were mentioned to be fluoride sources. Li et al.47 documented basalt, phosphorite and coal-bearing series were the fluoride sources of endemic fluorosis in Guizhou province, which was also supported by Zheng et al.41. Wang and Liu48 argued that high-fluoride rocks such as coal and shale were the primary sources of fluoride in the west of Guizhou province. Bai49 reported sandstone and shale were the fluoride sources in the Yulin region. Our investigation also recorded relatively higher fluoride levels in basalt, siltstone and shale than in carbonates, but their overlying soils contrarily have lower fluoride levels (Fig. 2). So, the fluoride migration during the soil-forming process is another factor controlling soil fluoride levels in carbonate areas.

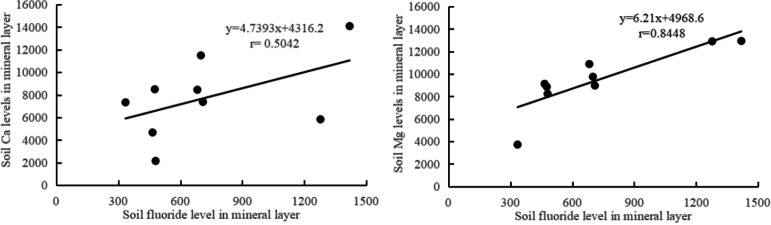

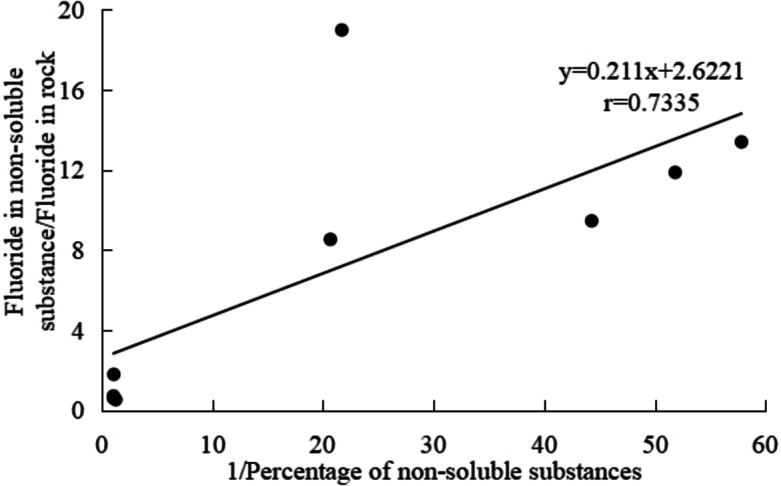

Carbonates widely distribute in southwest China, a typical karst area. The weathering products of carbonates were affirmed to be the soil sources in these areas by the analysis of trace elements, REE, minerals, isotopes, grain sizes, susceptibilities and sporopollenin50,51. An important process of numerous Ca(Mg)CO3 leaching occurs during carbonate weathering, which is unique to carbonates and different from non-carbonates. The carbonates have only acid insoluble substances of 1.73–4.84% in this work (Table 2), which is comparable to the previous researches by Li et al.52 and Feng et al.53. This means fluorine in carbonates can concentrate 20–60 times if all fluorine enters into the soils during weathering. But the ratios of fluoride levels in acid insoluble substances and carbonates are less than 20 (Table 2), implying that only less than 20 times the concentration levels are needed to form such soil fluoride levels in carbonate areas. The significantly positive correlation (P < 0.01) between fluoride in insoluble substances/fluoride in rocks and 1/percentage of insoluble substances also supports such a viewpoint (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Relationship between fluoride in insoluble substances/fluoride in rocks and the 1/percentage of insoluble substances.

Massive Ca2+(Mg2+) ions leach into the water during carbonate weathering, which hinders the F ions leaching into the water because it is restricted by CaF2 or MgF2 solubility5,30,35. The investigations in carbonate areas of southwest China also indicated the low fluoride levels in the water54,55. Moreover, the massive Ca(Mg) ions in soils can combine with F ions and deposit as CaF2 and MgF2 in carbonate areas. The significantly positive correlations (P < 0.01) between mineral soil Ca(Mg) levels and fluoride levels in this area were also observed, with r = 0.5042 (Ca) and 0.8448 (Mg) respectively (Fig. 4). The average Ca and Mg levels in the mineral soils of the carbonate areas are 9587.39 mg/kg and 11450.96 mg/kg respectively, while those in the non-carbonate areas are 4515.66 mg/kg and 7913.94 mg/kg respectively. Briefly, the high Ca(Mg) levels in carbonate areas may be another cause of the high fluoride levels in soils.

Fig. 4.

Correlations of Ca and Mg levels with fluoride levels in soil in the mineral horizon.

In fact, the high-fluoride soils overlying carbonates in coal-burning fluorosis areas have been widely documented. Li32 reported a fluorosis rate of 43.6% in Ganba village, where limestone (fluoride level of 132 mg/kg) of the Maokou Formation dominates. Ji56 found Permian limestone and dolomite have fluoride levels of 100–200 mg/kg, and the overlying red soils have average fluoride levels of 2300 mg/kg. But basalt has fluoride levels of 760–1300 mg/kg, and its overlying soils have only fluoride levels of 500–600 mg/kg. Zhu et al.33 recorded fluoride levels of 1000–2650 mg/kg in Pingba village with the underlying dolomite having fluoride levels of 430 mg/kg. Xie et al.26 also concluded the soils developing from Permian-Trias carbonates have higher fluoride levels than those from mudstone and sandstone. Huang et al.34 reported residual fluoride levels of 896–1667 mg/kg, 897–2827 mg/kg and 1386–2852 mg/kg in three soil profiles developing from carbonates in Guizhou province. Meng et al.57 documented average soil fluoride levels of 958.5 mg/kg in argillaceous limestone area and of 2298 mg/kg in argillaceous dolomite area. Huang et al.58 recorded residual fluoride levels of 896–1667, 897–2827, and 1386–2852 mg/kg in three carbonate areas. These observations also strongly imply that high-fluoride soils possibly result from carbonate weathering.

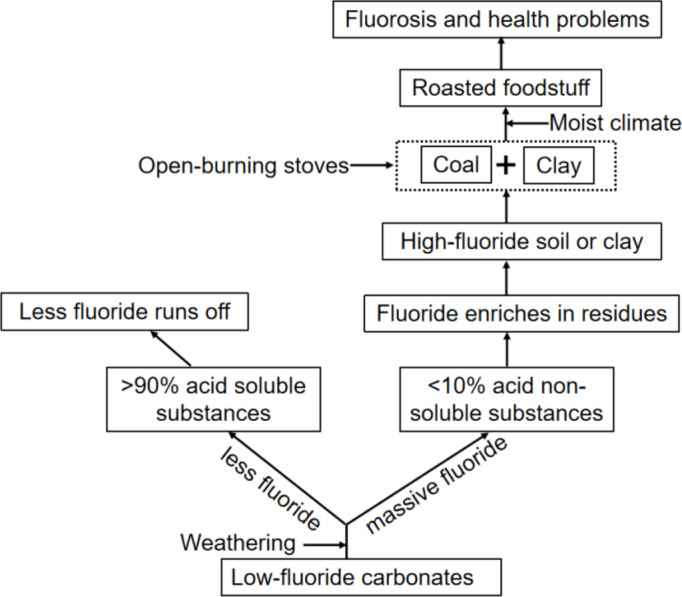

Open-burning stoves are used to roast the foodstuffs (mainly peppers and corns) hanging over the stoves. Some clay was added into the cheap dross coals as a binder, and the briquettes are actually mixtures of coals and clay. There are still some debates on the contribution of coals or clay to fluoride levels in foodstuffs. Some researchers argued that even though there is no clay, long roasting time also causes heavy contamination of fluoride in roasted foodstuffs considering the coals are extremely volatile and rich in sulfur59,60. But it is widely accepted that clay is high in fluoride level and is one of the culprits for coal-burning fluorosis. Although carbonates have low fluoride levels, they widely distribute and the vast majority of fluorine enters into the acid insoluble substances, forming high-fluoride soils. The fluorine enters the human body by digesting the roasted foodstuff, causing fluorosis (Fig. 5). So, the carbonates should be of concern when coal-burning fluorosis is discussed.

Fig. 5.

Exposure pathway of fluoride in carbonate areas.

The adaption prevention principle and policy

Some measures were tried to reduce the risk of fluorosis in these areas, such as using firewood or electricity to roast foodstuffs, altering the diet structure of pepper and corn into that of rice and flour, using other binders instead of clay, washing corn or peppers before cooking, and developing fluoride retention materials and so on. However, most residents cannot afford the cost of firewood, electricity, and binder or fluoride retention material. Even if local residents have changed their staple food, they still have traditional habits living on pepper and corn. Washing foodstuffs cannot remove fluoride to the standard level. Therefore, these measures are not practical and hard to spread across the fluorosis area. The best way to solve the problem of “coal-burning” fluorosis is to reveal soil fluoride origins and delimit the low-fluoride clay. Our research observed soils developing from carbonates had high fluoride levels although the bedrocks have low-fluoride levels, which is different from previous viewpoints and is a new insight. Nevertheless, only widely exposed strata and lithological types are noticed in this work, and a comprehensive and detailed investigation may be necessary. Also, the residents have no ability to make a distinction between high-fluoride clay and low-fluoride clay, and a professional aid from expert or government is helpful.

Conclusion

The soil and rock samples on different geological units were investigated and simulation experiments of acid insoluble substances were performed to detect the cause of coal-burning fluorosis in southwest China. The soils overlying O3w argillaceous limestone, P2c limestone interbedded with shale, and T2g dolomite have high fluoride levels. The soils developing from carbonates have higher fluoride levels than from other rocks although carbonates have relatively low fluoride levels. Furthermore, significantly positive correlations among fluoride levels in surface soils, mineral soils and farmland soils were observed, and there exist no significant correlations between fluoride levels in soils and rocks. The soil-forming process of carbonates is responsible for the high-fluoride clay although carbonates have low fluoride levels. Acid insoluble substances in carbonates are also observed to have higher fluoride levels than those in non-carbonates. The fluoride levels in insoluble substances are significantly correlated with those in soils, which well explains the high-fluoride soils developing from carbonates. Moreover, numerous Ca(Mg)CO3 in carbonate leaches, and the high Ca2+ (Mg2+) levels in carbonate areas restrict the fluorine-leaching into the water and deposit fluorine in the soil in carbonate areas. Consequently, excessive amounts of fluorine enrich in soils and high-fluoride soils form during the soil-forming process in carbonate areas. Therefore, the low-fluoride carbonates and their soil-forming processes should be of concern for the cause of coal-burning fluorosis in China. The exposure pathway of fluoride in carbonate areas is forwarded. On the basis of this, excluding high-fluoride clay and delimiting low-fluoride clay may be the best way to solve the problem of “coal-burning” fluorosis, and some information about the prevention principle and policy is provided in this research.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Natural Science Fund of Shandong Province (ZR2022MD032).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Qiao Chen. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Liping Zhang and Xuewenyu Wang. The manuscript was reviewed and revised by Qingcai Li, Juan Chen, Lin Zhu and Li Wang. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Data and analytical methods in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cui, J. et al. Effects of swine manure and straw biochars on fluorine adsorption–desorption in soils. PLoS ONE19 (5), e0302937 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao, N. S. Controlling factors of fluoride in groundwater in a part of South India. Arab. J. Geosci.10, 524 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, Q. et al. Geochemical process of groundwater fluoride evolution along global coastal plains: evidence from the comparison in seawater intrusion area and soil salinization area. Chem. Geol.552, 119779 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali, S. et al. Health risk assessment due to fluoride exposure from groundwater in rural areas of Agra, India: Monte Carlo simulation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol.18 (11), 3665–3676 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yousefi, M. et al. Northwest of Iran as an endemic area in terms of fluoride contamination: a case study on the correlation of fluoride concentration with physicochemical characteristics of groundwater sources in Showt. Desalin. Water Treat.155, 223–229 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu, Q. Q. et al. Continental-scale distribution and source identification of fluorine geochemical provinces in drainage catchment sediment and alluvial soil of China. J. Geochem. Explor.214, 106537 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization (WHO). Environmental Health Criteria 227 Fluorides (1996).

- 8.Malinowska, E., Inkielewicz, I., Czarnowski, W. & Szefer, P. Assessment of fluoride concentration and daily intake by human from tea and herbal infusions. Food Chem. Toxicol.46, 055–1061 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang, J. Y. & Gou, M. The research status of fluorine contamination in soils of China. Ecol. Environ. Sci.26 (3), 506–513 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smolentsev, B. A., Konarbaeva, G. A., Elizarov, N. V. & Popov, V. V. Content and distribution of fluorine in soil catenas of the Kulunda Plain. Contemp. Probl. Ecol.17 (3), 351–359 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu, Y. Q. et al. Co-existing metals, and potential health risk of fluorine in farmland soil in different anthropogenic activity dominated districts in a county-level city in Sichuan Province, Southwest China, in 2015. Environ. Geochem. Health44, 4311–4321. 10.1007/s10653-022-01200-4 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yousefi, M. et al. Spatial distribution variation and probabilistic risk assessment of exposure to fluoride in groundwater supplies: a case study in an endemic fluorosis region of northwest Iran. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub Health16, 564 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh, S. Y., Kim, H. & Yoon, H. O. Fluorine contamination, mobility, and risks in soils at a phosphate-gypsum waste landfill: a new analytical method and comparison with previous methods. Environ. Geochem. Health46, 170 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinese Health Statistics Yearbook. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic China (Beijing Union Medical University, 2019).

- 15.Guo, J. Y., Wu, H. C., Zhao, Z. Q., Wang, J. F. & Liao, H. Q. Review on health impacts from domesti coal burning: emphasis on endemic fluorosis in Guizhou Province, Southwest China. Rev. Environ. Contam. Technol.258, 1–25 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyth, O. Endemic fluorosis in Kweichow, China. Lancet16, 233–235 (1946). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, F. & Yan, S. Investigation on coal-burning fluorosis in Liupanshui. Guizhou Chin. J. Endemiol.22, 360–361 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, X., Wu, P., Han, Z. & Shi, J. Sources, distributions of fluoride in waters and its influencing factors from an endemic fluorosis region in Central Guizhou. China Environ. Earth Sci.75, 981 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 19.An, D., Yao, Z. & He, G. The medium of fluorine carrier-chili in the pollution of fluorine in Guizhou. Endemic Dis. Bull.11, 55–57 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, D. et al. Epidemiology of endemic fluorosis in the town central and remote villages of Guizhou Province. Chin. J. Endemiol.23, 138–141 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, W., Li, J., Guo, X. & Jiang, W. Analysis of fluorine pollution situation and source in poor rural areas of Guizhou Province. Earth Environ.41, 138–142 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai, S., Ren, D. & Ma, S. The cause of endemic fluorosis in western Guizhou Province, Southwest China. Fuel83, 2095–2098 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong, X., Liang, H., Zhang, Y. & Xu, D. Distribution of acidity of late Permian coal in border area of Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan. J. China Coal Soc.41, 964–973 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong, F. & Luo, X. Research on the distribution of fluorine in coal and the occurrence regularity. Coal Qual. Technol.5, 13–16 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai, S., Li, W., Tang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Feng, P. The sources, pathway, and preventive measures for fluorosis in Zhijin County, Guizhou, China. Appl. Geochem.22, 1017–1024 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie, X., Yang, X., Yang, S., Zhang, J. & Bin, Z. A tentative discussion on the source of endemic fluorosis: geo-environmental evidence from three counties in Guizhou Province. China Geol.37, 696–703 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong, X., Liang, H., Lv, S., Wang, D. & Zhang, Y. Potential release of fluoride from clay used for coal-combustion in Hehua village, Zhijin County, Guizhou Province. Geol. Rev.61, 852–860 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou, D., Fu, Q., Wang, Z. & Zhou, C. Investigation on the relationship between fluorine content in coal mixed with clay and coal-burning fluorosis. Chin. J. Control Endemic Dis.6, 243–244 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, M., Chen, X. X., Hamid, Y. & Yang, X. E. Evaluating the response of the soil bacterial community and lettuce growth in a fluorine and cadmium co-contaminated yellow soil. Toxics12, 459 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saxena, V. K. & Ahmed, S. Dissolution of fluoride in groundwater: a water-reaction study. Environ. Geol.40, 1084–1090 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouzar, B., Mahfoud, B. & Abriak, N. Fluorine soil stabilization using hydroxyapatite synthesized from minerals wastes. Arab. J. Chem.16, 105261 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, X. J. Geological characteristics and prediction of endemic fluorosis in Guizhou Province. Geol. Geochem.12, 53–56 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu, L. J., Li, J. Y. & Mu, C. G. Study on environmental geochemistry of fluorine in rock soil water system in karst area of central Guizhou. Carsol. Sin.2, 9–15 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang, Y., Zhao, M., Wu, D. S. & Tang, Q. Z. Distribution characteristics of fluorine in soils profiles developed on carbonate rocks and its influencing factors. Earth Environ.45 (04), 472–477 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen, Q. et al. Soil organic carbon and geochemical characteristics on different rocks and their significance for carbon cycles. Front. Environ. Sci.9, 784868 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng, G. W., Tian, J. H. & Qin, Y. Study on the sources of endemic fluorosis in Weixin, Yunnan Province, China. J. China Univ. Min. Technol.36 (2), 241–245 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji, J. J. et al. Investigation of epidemic fluorosis and the current prosthodontical therapy status in coal-burning pollution area of Zhengxiong and Weixin. Int. J. Stomatol.37 (4), 382–385 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng, F. J., Liu, X. P., Yu, J. P., Wang, W. Y. & Luo, K. L. Determination of fluorine in the environmental samples by combustion hydrolysis-ion selective electrode method. J. Hygiene Res.33 (3), 288–290 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan, J. N., Zhang, Y., Li, G. P., Guo, L. & Wei, W. Determination of 22 metals in soil by ICP-MS based on different pretreatment methods. J. Anal. Sci.40 (4), 454–450 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan, Z. et al. Geochemical characteristics of fluorine in soils and its environmental quality in central district of Guiyang. Res. Environ. Sci.31, 87–94 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng, Y. C., Liao, L. P. & Liu, L. Y. Investigation and analysis on the background of soil fluoride in Guizhou province and its relationship with endemic fluorosis. Stud. Trace Elem. Health26 (05), 39–41 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang, J. Y. et al. Fluorine in the environment in an endemic fluorosis area in Southwest, China. Environ. Res.184, 109300 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu, D., Wu, T., Dong, R. & Li, P. Advance in absorption and enrichment of soil fluorine by plants. J. Nanchang Univ.30, 103–111 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li, D. P. & Wu, Z. J. Soil eco-environmental effects of chemical fertilizers. J. Appl. Ecol.19 (5), 1158–1165 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng, B. S. et al. Finkelman Robert. Main geochemical processes leading to the prevalence of coal-burning fluorosis. Chin. J. Endemiol.4, 468–471 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding, Z. Z. & An, C. J. Epidemic characteristics and control measures of endemic fluorosis in Hubei Province. Chin. J. Geol. Hazard. Control2, 85–87 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li, M. Q., Liu, Y. M. & Liao, L. P. Study on fluoride and iodine in the environment of endemic fluorosis and iodine deficiency areas in Guizhou. Res. Environ. Sci.6, 44–46 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, S. Y. & Liu, J. R. The fluorine sources in the endemic fluorosis areas, western Guizhou. Sediment. Geol. Tethyan Geol.26 (3), 72–76 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bai, G. L. Relationship between endemic fluorosis and geographical factors in Shaanxi province. Chin. J. Endemiol.1, 59–61 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu, Z. M., Huang, R. Q., Tang, Z. G. & Fei, W. S. A review of advances and outstanding issues in research on the forming mechanism of laterite in south China. Earth Environ.4, 33–40 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu, W. J. et al. The weathering and soil formation process in karstic area, southwest China: a study on strontium isotope geochemistry of yellow and limestone soil profiles. J. Earth Environ.2 (02), 331–336 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li, Y. B., Wang, S. J. & Luo, G. J. A discussion on the pedogenesis of carbonate and soil stratum genesis overlying it. Mod. Geogr. Sci. Guizhou Soc. Econ.1, 52–57 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feng, Z. G., Zhou, B. J., Ma, Q. & Han, S. L. Enrichment mechanism and environmental impact of heavy metals in soil of Karst area: a case study on Pingba profile in central Guizhou. J. Univ. S. China (Sci. Technol.)34 (05), 1–8 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pu, W., Ding, J. & Ying, W. High fluoride groundwater distribution characteristics and genetic analysis of water exploration engineering in Guizhou. Environ. Prot. Technol.19, 10–15 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang, X., Zhao, B., Tan, M., Zhou, B. & Sun, J. Water quality evaluation and environmental significance of ground water in Dafang area Guizhou Province. Ground Water38, 3–6 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ji, R. The local fluorine poisoning in Guizhou and its relations with environment. Geol. Guizhou3, 291–295 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meng, W. et al. Element geochemistry and fluoride enrichment mechanism in high-fluoride soils of endemic fluorosis-affected areas in Southwest China. Earth Environ.40 (2), 144–147 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang, Y., Zhao, M., Wu, D. S. & Tang, Q. Z. Distribution characteristics of fluorine in soils profiles developed on carbonate rocks and its influencing factors. Earth Environ.45 (4), 472–477 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liang, H., Liang, N., Gardella, J. A. J., He, P. & Yatzor, B. P. Potential release of F from coal in coal-burning fluorosis areas in Guizhou. Chin. Sci. Bull.56, 2301–2304 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duan, P. et al. Partitioning of hazardous elements during preparation of high-uranium coal from Rongyang, Guizhou, China. J. Geochem. Explor.185, 81–92 (2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and analytical methods in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.