Keywords: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, serious mental health conditions, trauma, scoping review

Abstract

Background

There is a strong link between trauma exposure and serious mental health conditions (SMHCs), such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The majority of research in the field has focused on childhood trauma as a risk factor for developing an SMHC and on samples from high-income countries. There is less research on having an SMHC as a risk factor for exposure to traumatic events, and particularly on populations in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

This scoping review aimed to synthesize the nature and extent of research on traumatic events that adults with SMHCs face in LMICs. It was conducted across five databases: PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection and Africa-Wide Information/NiPad in December 2023 and by hand searching citation lists.

Findings

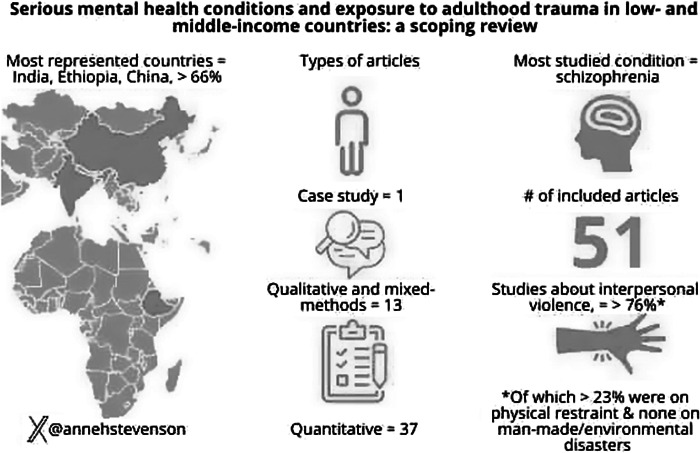

The database search returned 4,111 articles. After removing duplicates and following a rigorous screening process, 51 articles met criteria for inclusion. There was one case study, one mixed methods study, 12 qualitative studies and 37 quantitative studies. Ten countries were represented, with the most studies from India (n = 19), Ethiopia (n = 9) and China (n = 6). Schizophrenia was the most studied type of SMHC. Of the trauma exposures, more than 76% were on interpersonal violence, such as sexual and physical violence. Of the studies on interpersonal violence, more than 23% were on physical restraint (e.g., shackling) in the community or in hospital settings. There were no studies on man-made or natural disasters.

Implications

Much of our data in this population are informed by a small subset of countries and by certain types of interpersonal violence. Future research should aim to expand to additional countries in LMICs. Additional qualitative research would likely identify and contextualize other trauma types among adults with SMHCs in LMICs.

Impact statement

The impact of this scoping review, a type of analysis that looks at all the research on a specific topic, shows much of our data on adults with preexisting serious mental health conditions (SMHCs) who are then exposed to trauma in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) come from a small subset of countries and certain types of interpersonal violence.

History of the topic: Trauma exposure and SMHCs, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, have been shown to be interconnected. Most of the research in this area has focused on childhood trauma as a risk factor for developing an SMHC, and the bulk of this work has come from studies in high-income countries in North America and Western Europe. While it is often stated that people with SMHCs are more vulnerable to experiencing traumatic events than the general public, there is less research on having an SMHC as a risk factor for exposure to traumatic events, and particularly on populations in LMICs, which have been underrepresented in research to date. This scoping review aims to fill this gap and to synthesize what trauma types adults with SMHCs face in LMICs.

Main takeaways: After a thorough search, we found that studies on this topic came from only 10 countries (out of more than 130 LMICs) and two-thirds of these were from India, Ethiopia and China. The vast majority of these studies were about interpersonal violence, such as sexual violence, intimate partner violence and physical violence, and more than one-fifth of these were on physical restraint, such as chaining. There were no studies on man-made or natural disasters. The findings support that adulthood trauma exposure among people with SMHCs is an existing issue in LMICs and is a call to action to eradicate violent practices in both community and healthcare settings.

Introduction

There is an established link between trauma exposure and serious mental health conditions (SMHCs), such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder (Grubaugh et al., 2011; Mauritz et al., 2013). Many studies have shown that trauma exposure, often defined as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), poses a significant risk for the development of SMHCs (Read et al., 2005; Varese et al., 2012; Woolway et al., 2022). Most of the research on trauma and SMHCs has focused on childhood adversity and in samples from high-income countries in Europe, North America and Australasia (Read et al., 2005; Varese et al., 2012; Woolway et al., 2022).

Multiple models have been proposed to explain why exposure to trauma, and particularly childhood adversity, may increase the risk for developing an SMHC, including the stress-vulnerability model (Zubin and Spring, 1977). This model posits that some people have a biological vulnerability to SMHCs. While individuals may be able to withstand a certain amount of stress, once a certain threshold of stress is reached or a stressor is particularly intense, people become more susceptible to developing SMHCs.

Likewise, researchers have also argued that people with SMHCs may be more vulnerable to exposure to trauma than those without such conditions. Population studies have found people with SMHCs report more victimization than the general public (Maniglio, 2009; de Vries et al., 2019). One theory for this is that people with SMHCs may have cognitive impairments that impact their decision-making and problem-solving abilities, restricting their ability to navigate potentially dangerous situations (de Vries et al., 2019). People with SMHCs may also be exposed to trauma through settings due to their mental health conditions, such as inpatient and outpatient healthcare centers. Patients with SMHCs have reported high rates of trauma exposure in psychiatric settings, including physical and sexual assault by staff, police and other patients (Frueh et al., 2005; Lundberg et al., 2012a).

Like the childhood adversity literature, the research on having an SMHC as a risk factor for trauma exposure in adulthood has also primarily been from samples in high-income countries (Maniglio, 2009; de Vries et al., 2019). Deepening research in LMICs may shed light on the possibility of unique traumas in this population. Furthermore, identifying and codifying trauma exposure in this population may raise awareness about such incidents and lead to healthcare and human rights policy changes for people with SMHCs (Guan et al., 2015; Hidayat et al., 2023).

This scoping review aims to fill this gap by synthesizing the literature on trauma that adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder or depression with psychotic features are exposed to in LMICs, which have been less represented in research to date.

We framed this exploratory study around Peters et al.’s population, concept, context framework for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2021). Our primary research question aimed to establish the evidence base on adult trauma exposure experienced by people with SMHCs in LMICs. In other words, what is the extent, range, and nature of research about adults with SMHCs (population) being exposed to a traumatic event in adulthood (concept) in an LMIC (context)?

Our secondary research question was to ascertain whether there were any trends in the data; for example, whether there were trauma types or demographics that were more commonly studied than others. We expected most trauma exposures would be types of interpersonal violence (use of physical, sexual or psychological force against another person or small group of people) (Mercy et al., 2017) and human rights violations, such as solitary confinement for multiple years.

Methods

We followed the JBI updated guidelines for the conduct of scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2021). As part of the review, we developed an extensive search query, retrieved all articles, conducted multiple phases of screening, extracted the data and synthesized the results. We outline each step below.

Search strategy: We developed our search strategy to run in five databases: PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection and Africa-Wide Information/NiPad. We started with PubMed and used a combination of medical subject headings (MeSH), some of which were “exploded” to retrieve any citations that fell under its subheadings, title and abstract (tiab) fields, and keyword (kw) fields. We used Boolean operators to develop a search query based on more than 300 terms and phrases connected to SMHCs, traumatic events and LMICs.

For SMHCs, we included words that were often associated with this term, such as “schizophrenia,” “serious mental illness” and “psychotic disorder.”

For trauma exposure, we pulled terms from two commonly used measures that assess potentially traumatic events: the Life Events Checklist for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fifth Edition (LEC-5) (Weathers et al., 2013) and the posttraumatic stress disorder module of the World Mental Health Survey version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kessler and Üstün, 2004), which is based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). We then expanded the terms from the LEC-5 and the CIDI to include specific examples of the type of trauma in question. For example, for “natural disasters,” we listed this term and also listed typhoons, landslides, tsunamis, etc. A priori, on the basis of qualitative studies with people with SMHCs in LMICs and commentaries by leaders in the field (Alem, 2000; Ametaj et al., 2021), we included events that may be more common in LMICs than in high-income countries, although they can happen anywhere, including human rights violations, mob justice, chaining and restraining. Additionally, we included the term “idiom(s) of distress” to potentially retrieve articles that might have focused on expressions of trauma not typically captured in “Western” terminology.

For LMICs, we included the name of every country that was classified as an LMIC by the World Bank as of November 2023 (World Bank, 2023) (i.e., Afghanistan) as well as unrecognized countries or disputed territories that were not on the World Bank list but still met criteria as an LMIC (i.e., Somaliland). We also added overarching categories that are sometimes used to describe these groupings, such as “South Asia,” “developing country,” and “Global South.”

We then adapted the search string to Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Africa-Wide Information/NiPad using their controlled subject vocabulary. See Supplemental File 1 for the full search strings for each database.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Our inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

Inclusion:

Adults aged ≥18 years.

People with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder or depression with psychotic features.

Trauma exposure must have occurred after the psychiatric diagnosis.

Study population was in an LMIC.

Observational studies only.

Empirical studies in peer-reviewed journals, including case studies, qualitative studies and quantitative studies.

There were no restrictions on the language in which the article was written.

There were no restrictions on the date the article was published.

Exclusion:

Studies with data collected in high-income countries.

Studies where it was not clear when the trauma occurred and the diagnosis of the mental health condition occurred.

Studies where the trauma only occurred in childhood, adolescence or youth.

Children (people aged <18 years).

Intervention studies (i.e., randomized control trials).

Conference papers and abstracts, commentaries, letters, news articles, scoping reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and gray literature.

Biological process studies such as biomarkers, genetic studies, biospecimens and circuitry.

Animal studies.

There were a few caveats to these criteria. If we could not distinguish whether an article included participants with depression vs. depression with psychotic features, we kept the article in. If an article was about “psychiatric conditions,” but we could not split out data from the disorders that met our eligibility criteria (i.e., schizophrenia) from the overall grouping, we excluded the article. If an article included participants under 17.9 years and we could separate out data for participants ≥18, we included the article and only reported on data pertaining to adults. If we could not split out participants under 17.9 from ≥18 (for example, if the age range was 15–49), the article met all our other eligibility criteria and the mean age of participants was ≥18, we included the article.

Reviewing retrieved articles

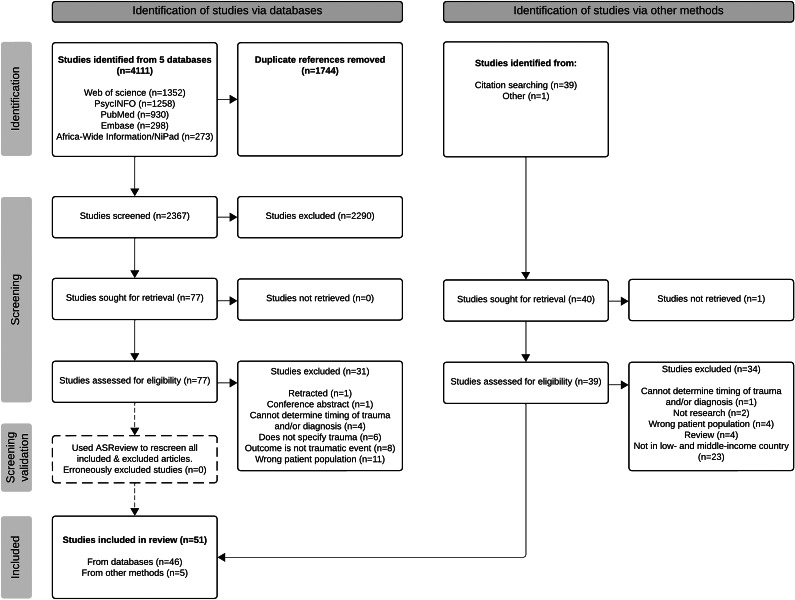

We ran our search on December 20, 2023, downloaded the citations from the retrieved articles and imported them into Covidence (www.covidence.org [Veritas Health Innovation Ltd, 2024]). Following the removal of duplicate articles in Covidence, we followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018) process and created a flowchart to capture each stage (see Figure 1).

We screened the remaining articles in two stages. First, two reviewers (AS and EG) independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The same reviewers then independently screened the full text of the remaining articles to assess eligibility. At both stages, for articles that were in conflict, the two reviewers discussed the articles and came to a consensus on whether they met eligibility. Following confirmation that an article met the criteria, we hand-searched its reference list to identify additional articles that should be reviewed (Dundar and Fleeman, 2017).

We then moved all articles into the data extraction pool. We created a Google Sheet to extract a range of fields from each article: article information (i.e., first author and title), study design, sample size, sex/gender of participants (% female), mean age, racial/ethnic composition, participant psychiatric diagnosis, method of assessment for the psychiatric condition, type of trauma exposure, tool used to assess trauma exposure, and country and municipality where the participants were recruited. AS extracted data for each article, and another reviewer independently extracted data from the same article. They then cross-checked each other’s work to ensure accuracy. We held group discussions when there were divergent decisions and came to a consensus on the final answer.

Search procedure validation

In order to validate our search procedure and to confirm that we did not exclude any articles in the screening stages that should have been included, we used a machine learning tool, ASReview version 1.6.2 (https://asreview.nl/ [van de Schoot et al., 2021]) to additionally re-check the excluded articles. ASReview is an open-source software that utilizes active-learning to screen large amounts of data primarily for scoping and systematic reviews. For this process, we uploaded all the articles from the original screening phase (following the removal of the duplicates). We then selected one article that met inclusion criteria and one that did not train the software on which articles should be included/excluded. We screened 407 articles in total, labeling each one as “relevant” (likely met inclusion criteria) and “irrelevant” (did not meet inclusion criteria). From the articles we labeled as relevant, we cross-checked these against our final list of included articles and reread the full text of any articles we had originally excluded to determine whether they met inclusion criteria.

Synthesis plan

The synthesis plan was a narrative summary following guidelines from (Cumpston et al., 2022) in which we focused primarily on the types of studies included, countries where the data collection took place and types of trauma reported. We presented the charting results as text in a table and graphical summaries of the research data.

We did not conduct a formal publication bias analysis as this is not typically done in scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2021).

Protocol deposit

The protocol for this study is available through Open Science Framework and can be found here: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/JRSQP.

Results

We ran our search in PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection and Africa-Wide Information/NiPad, which retrieved 4,111 articles. After uploading all search results into Covidence, we removed 1,744 duplicates and were left with 2,367 articles for title and abstract screening. AS and EG double screened all titles and abstracts and removed 2,290 irrelevant studies. Their agreement rate was 97.5%. We then reviewed the full text of 77 articles. Forty-six studies met the criteria for inclusion. For the hand-searching process, AS identified 39 citations for articles to screen; after going through the full screening process for these articles, AS found four that met eligibility. In addition, AS discovered an additional article that met the criteria during a separate literature review. AS added these five articles to the pool for extraction. Using ASReview, AS tagged 57 articles as relevant, of which 46 were already in our included pool. Upon rereading the additional 11, they still did not meet our inclusion criteria; thus, the software did not identify any erroneously excluded articles.

We were left with 51 articles that met the criteria. (See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram that captures the search and selection process.)

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the search and selection process for the scoping review.

We then extracted data from all the remaining articles into a Google document (see Table 1 for the articles that met eligibility and the data we extracted from each). There was 1 case study, 1 mixed-methods study (both qualitative and quantitative measures), 12 qualitative studies and 37 quantitative studies. Of the quantitative studies, the majority were cross-sectional. There were nine studies reporting on mortality, all of which were cohort studies, some of which followed patients for years and some which used national or regional health records to determine mortality rates. The number of participants in the studies ranged from 1 to 72,021,918. The percentage of female participants ranged from 0% to 100%. For studies that provided a mean age of participants (n = 42), the average age ranged from 26.7 to 51.9 years. The most represented countries were India (n = 19), Ethiopia (n = 9) and China (n = 6), which made up two-thirds of the studies. Additional countries represented in the studies were Indonesia (n = 5), Nigeria (n = 3), Uganda (n = 3), Brazil (n = 2), Egypt (n = 2), Ghana (n = 1) and South Africa (n = 1). The most studied mental health condition was schizophrenia. The most studied traumatic event was interpersonal violence (76.5%–84.3%) 1 including intimate partner violence and sexual and physical victimization types. Of the types of interpersonal violence, more than one-fifth were about physical restraint, which ranged from shackling people by their ankles to a tree to chemical restraint in a hospital (23.3%–34.9%) 1. There were no studies on man-made or natural disasters.

Table 1.

Articles and their characteristics included in the scoping review

| First author – year of publication | Article title | Country | Region | Study design | Population description | # of participants | % Female | Mean age (years) | Race/ethnicity of participants | Type of trauma(s) assessed | How traumas were assessed | % of participants with SMHC who experienced traumatic event | Mental health diagnosis | How mental health diagnosis was assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afe 2016 (Afe et al., 2016) | Intimate partner violence, psychopathology and the women with schizophrenia in an outpatient clinic South–South, Nigeria | Nigeria | Cross River State, South–South | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Female outpatients with SCZ | 77 | 100% | 38.3 | Efik/Ibibio (49.0%), Ibos (34.0%), Yoruba (16.0%) and Hausas (1.0%) | IPV | WHO Violence Against Women Instrument | 75% | SCZ | SCID |

| Aluh 2022 (Aluh et al., 2022) | Experiences and perceptions of coercive practices in mental health care among service users in Nigeria: a qualitative study | Nigeria | Not reported | Qualitative | Mental health service users at two major psychiatric hospitals | 30 | 36.7% | 34.67 | Not reported | Coercive practices in hospitals, for example, use of ropes, chains and handcuffs for mechanical restraint, being whipped | Focus group discussions | 40% chaining and 16.6% whipping | SCZ, SZA, BD, depression and other mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance | Not reported |

| Ametaj 2021 (Ametaj et al., 2021) | Traumatic Events and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Individuals with Severe Mental Illness in a Non-Western Setting: Data from Rural Ethiopia | Ethiopia | Sodo District, Gurage Zone | Qualitative | Patients with SMI, their caregivers, healthcare providers, and community and religious leaders in a rural community | 48 in full sample; 13 with SMI | 46.15% of people with SMI | 35.15 years for people with SMI | Gurage (100%) | Multiple, including chaining, animal attacks, rape and physical assault | Semi-structured interview | N/A | SMI: SCZ, BD and depression with psychotic features | OPCRIT conducted by psychiatric nurses |

| An 2016 (An et al., 2016) | Physical restraint for psychiatric patients and its associations with clinical characteristics and the National Mental Health Law in China | China | Beijing | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Patients with psychiatric conditions | 1,364 | 63.9% | 36.2 | Not reported | Physical restraint, for example, use of belts to fix a patient to a bed | Chart review and confirmed during interviews | 35.2% of people with SCZ and 42.1% with mood disorders | SCZ, mood disorders and other | Confirmed in a clinical interview |

| Asher 2017 (Asher et al., 2017) | “I cry every day and night, I have my son tied in chains”: physical restraint of people with schizophrenia in community settings in Ethiopia | Ethiopia | Sodo and Butajira districts, Gurage Zone | Qualitative | People with SCZ, their caregivers, community leaders, and primary and community health workers in rural community | 50 in full sample; 4 with SCZ | 52.0% of full sample; 25% of people with SCZ | Not reported | N/A | Physical violence and restraint in community settings, for example, beating, use of handcuffs, chains and iron bars | Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews | N/A | SCZ | OPCRIT conducted by a psychiatric nurse |

| Bagewadi 2016 (Bagewadi et al., 2016) | Standardized Mortality Ratio in Patients with schizophrenia – Findings from Thirthahalli: A Rural South Indian Community | India | Thirthahalli, Karnataka | Quantitative: cohort | Patients with SCZ who live in a community setting who are alive and those who died | 943 in full sample;12 deceased | 33.3% of the deceased patients | 45.1 for the deceased patients | Not reported | Accidents leading to death | Chart review and/or verbal report from family members | 0.11% of the full cohort; 8.3% of the deceased patients | SCZ | Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist, followed by the MINI |

| Belete 2017 (Belete, 2017a) | Leveling and abuse among patients with bipolar disorder at psychiatric outpatient departments in Ethiopia | Ethiopia | Addis Ababa | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Outpatients with BD | 411 | 57.4% | 34.35 | Amhara (34.55%), Oromo (32.85%), Gurage (20%), Tigray (5.8%) and others (6.8%) | Verbal or physical abuse | Chart review and by asking the patients and/or from family members | 37.7% | BD | Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist or mental health professional specialist |

| Belete 2017 (Belete, 2017b) | Use of physical restraints among patients with bipolar disorder in Ethiopian Mental Specialized Hospital, outpatient department: cross-sectional study | Ethiopia | Addis Ababa | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Outpatients with BD | 400 | 57.2% | 32 | Amhara (34.7%), Oromo (33.0%), Gurage (19.7%), Tigray (5.8%) and others (6.8%) | Physical restraint | Chart review and/or verbal report from family members | 65% | BD | Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist or mental health professional specialist |

| Bhattacharya 2022 (Bhattacharya, 2022) | “The Day I Die Is the Day I Will Find My Peace”: Narratives of Family, Marriage, and Violence Among Women Living with Serious Mental Illness in India | India | Not reported | Qualitative | Current or former female inpatients with SMI living in an urban setting | 11 | 100% | Mid‑30s to early 60s, no mean age provided | Not reported | Domestic and sexual violence | In-depth interviews | N/A | SMI: SCZ, SZA or BD | Not reported |

| Chandra 2003 (Chandra et al., 2003) | A Cry from the Darkness: Women with Severe Mental Illness in India Reveal Their Experiences with Sexual Coercion | India | Bangalore | Mixed-methods (qualitative and structured interviews) | Female inpatients with SMI | 50 | 100% | 30 | Not reported | Sexual coercion, that is, forced sexual intercourse, unwanted sexual play and sexual experiences involving threats or use of physical force | Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) and semi-structured interview | 34% coercive experiences after onset on mental illness | SMI: recurrent depressive disorder, SCZ spectrum disorder, BD and other disorders | Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist |

| Chandra 2003 (Chandra et al., 2003) | Sexual coercion and abuse among women with a severe mental illness in India: An exploratory investigation | India | Bangalore | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Female inpatients with SMI | 146 | 100% | 31.6 | Not reported | Sexual coercion, that is, forced sexual intercourse, unwanted sexual play, and sexual experiences involving threats or use of physical force | Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) | 16% of adult sexual coercion and 7% of both adult sexual coercion and child sexual abuse | SCZ-spectrum disorders, BD and depression | Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist |

| de Oliveira 2013 (de Oliveira et al., 2013) | Physical violence against patients with mental disorders in Brazil: sex differences in a cross-sectional study | Brazil | National | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Patients with SMI using public mental health services | 2,475 | 51.6% | 44.9 women and 51.9 men | Not reported | Physical violence | Semi-structured interview | 12.0% of women and 16.0% of men experienced physical violence within health institutions by other patients, employees or health professionals. (Other physical violence reported could not be split out from lifetime exposure.) | SCZ and other psychosis, BD, depressive disorder and others | Chart review |

| El Missiry 2019 (El Missiry et al., 2019) | Rates and profile of victimization in a sample of Egyptian patients with major mental illness | Egypt | Cairo | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Inpatients and outpatients with major mental illness | 300 | 52.0% of full sample | 34.3 for victimized sample | Not reported | Covert/relational victimization or physical victimization, that is, threatened or subjected to corporeal damage | Victimization Questionnaire (VQ) | 43.3% | Major mental illness: SCZ, BD and major depression | SCID |

| Fekadu 2015 (Fekadu et al., 2015) | Excess mortality in severe mental illness: 10-year population-based cohort study in rural Ethiopia | Ethiopia | Butajira District, Gurage Zone | Quantitative: cohort | People with SMI and those without in a rural community | 919 in full cohort; 121 patients who died | 37.8% | 15–49 at baseline, no mean age provided | Not reported | Accidents leading to death and homicides | Verbal autopsy | 9.10% | SMI: SCZ, BD and severe depression | SCAN conducted by a psychiatrist or mental health professional |

| Fekry 2012 (Fekry, 2011) | Clinical and sociodemographic profile of victimized versus nonvictimized Egyptian patients with bipolar mood disorder | Egypt | Cairo | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Inpatients and outpatients with BD | 100 | 36.0% of full sample; 41.7% of victimized group | 31 | Not reported | Covert/relational victimization or physical victimization, that is, threatened or subjected to corporeal damage | Victimization Questionnaire (VQ) | 48% | BD | SCID |

| Gilmoor 2020 (Gilmoor et al., 2020) | “If somebody could just understand what I am going through, it would make all the difference”: Conceptualizations of trauma in homeless populations experiencing severe mental illness | India | Kanchipuram and Chennai | Qualitative | People with SMI who were previously homeless or at risk of homelessness | 26 | 76.9% | 47 | Not reported | Multiple, including abuse, man-made accidents, natural disasters, violence, illness and death | In-depth interviews and questions based on previous culturally relevant free listing exercise | N/A | SMI: SCZ, BD, psychosis NOS, substance induced delirium and major depressive disorder | Self-report |

| Gowda 2018 (Gowda et al., 2018) | Restraint prevalence and perceived coercion among psychiatric inpatients from South India: A prospective study | India | Bangalore | Quantitative: cohort | Inpatients with SCZ or mood disorders | 200 | 45% | 33.5 | Not reported | Restraint measures: physical restraints, chemical restraints, seclusion/isolation and involuntary medication | Interviews with participants and health records | 66.5% experienced 1+ restraint measures; 20% physical restraint, 58% chemical restraint, 18% seclusion and 32% involuntary medication | SCZ or other psychotic disorders and mood disorders | MINI |

| Hu 2022 (Hu et al., 2022) | A Retrospective Analysis of Death Among Chinese Han Patients with schizophrenia from Shandong | China | Shandong | Quantitative: cohort | Patients with SCZ who are alive and those who died | 72,102 in full sample; 11,766 deceased | 48.21% | 47.21 | Han (100%) | Accidents leading to death and homicides | Death certificates or forensic specialist | 6.97% | SCZ | Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist |

| Jakhar 2015 (Jakhar et al., 2015) | A cross sectional study of prevalence and correlates of current and past risks in schizophrenia | India | New Delhi | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Patients with SCZ from the psychiatric ward of large mental hospitals | 270 | 35.2% | 34.0 | Not reported | “Risk from others” | Ram Manohar Lohia Risk Assessment Interview | 11% | SCZ | Referral by treating a clinician followed by Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies – Hindi version (DIGS) |

| Lundberg 2012 (Lundberg et al., 2012b) | Sexual Risk Behaviors and Sexual Abuse in Persons with Severe Mental Illness in Uganda: A Qualitative Study | Uganda | Kampala | Qualitative | Inpatients cleared for discharge and outpatients | 20 | 65% | 18–49, no mean age provided | Not reported | Sexual abuse | Semi-structured interview | N/A | SMI: SCZ, BD or depression | Chart review |

| Lundberg 2015 (Lundberg et al., 2015) | Sexual Risk Behavior, Sexual Violence, and HIV in Persons with Severe Mental Illness in Uganda: Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study and National Comparison Data | Uganda | Kampala | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Former inpatients with SMI | 602 | 57.0% (note: only women assessed for sexual violence) | 18–49, no mean age provided | Not reported | Sexual violence | WHO Violence Against Women Instrument | 24.2% of women experienced sexual violence by a partner; 10.5% of women experienced sexual violence by a non-partner | SMI: BD, nonaffective psychosis and major depression | Chart review |

| Manjunatha 2019 (Manjunatha et al., 2019) | Mortality in schizophrenia: A study of verbal autopsy from cohorts of two rural communities of South India | India | Thirthahalli and Turuvekere, Karnataka | Quantitative: cohort | People with SCZ from rural communities who died | 53 | 47.1% | 50.5 | Not reported | Death due to road traffic accidents | Verbal autopsy | 5.6% | SCZ | Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist, followed by the MINI |

| Melo 2022 (Melo et al., 2022) | All-cause and cause-specific mortality among people with severe mental illness in Brazil’s public health system, 2000–2015: a retrospective study | Brazil | National | Quantitative: cohort | Inpatients with SMI and those without in the public health system | 72,021,918 in full sample; 749,720 with SMI | 56.9% of the full sample and 50.5% of the people with SMI | 41.1 for full sample | Not reported | Injuries including interpersonal violence and unintentional causes such as fires, drowning, foreign body, road injuries and falls | Chart review | 19.9% of deaths in the population with SMI | SMI: SCZ, SZA, BD or depressive disorder | Chart review |

| Minas 2008 (Minas and Diatri, 2008) | Pasung: Physical restraint and confinement of the mentally ill in the community | Indonesia | Samosir | Quantitative: cross-sectional | People with SMI in the community | 15 | 46.7% | 25–56 years, no mean age provided | Not reported | Physical restraint and confinement, that is, by wooden stocks, confined in a small room or hut, tied with rope or chained | Physical identification (case finding) | 100% | SCZ and other | Self-report and reports by family or community members |

| Mojtabai 2001 (Mojtabai et al., 2001) | Mortality and long-term course in schizophrenia with a poor 2-year course: A study in a developing country | India | Urban and rural Chandigarh | Quantitative: cohort | Patients with SCZ in an urban and a rural setting | 171; 24 participants who died | 47% of full sample | 26.7 at baseline | Not reported | Death due to traffic accidents | Verbal autopsy and/or medical records | 0.58% of full sample; 4.2% of the deceased group | SCZ | Present State Examination (PSE) |

| Moodley 2023 (Moodley et al., 2023) | The missed pandemic: Intimate partner violence in female mental-health-care-users during the COVID‑19 pandemic | South Africa | KwaZulu-Natal | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Female outpatients with SMI | 154 | 100% | 42.7 | Black (50.3%), White (17.2%), Indian (21.2%) and colored (11.3%) | Interpersonal violence | Women Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) | 46.6% | SMI: SCZ spectrum disorder, BD, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders and personality disorders | Diagnoses were confirmed clinically using DSM‑5 criteria by the researcher and chart reviews provided by the treating doctor |

| Mpango 2023 (Mpango et al., 2023) | Physical and sexual victimization of persons with severe mental illness seeking care in central and southwestern Uganda | Uganda | Kampala and Masaka | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Outpatients with SMI | 1,201 | 54.5% | 36 | Not reported | Physical and sexual victimization | Adverse life events module of the European Para-suicide Interview Schedule (EPSIS I) | 13.6% physical victimization and 8.6% sexual victimization in the last 12 months | SMI: SCZ, BD and recurrent major depressive disorder | Chart review followed by the MINI |

| Nair 2020 (Nair et al., 2020) | Prevalence and clinical correlates of intimate partner violence (IPV) in women with severe mental illness (SMI) | India | “Southern part of India” | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Female inpatients with SMI who cohabitate with a partner | 100 | 100% | 34.2 | Not reported | IPV | Indian Family Violence and Control Scale (IFVCS) | 20% in the last 12 months | Psychosis and BD | Chart review |

| Ng 2019 (Ng et al., 2019) | Trauma exposure, depression, suicidal ideation, and alcohol use in people with severe mental disorder in Ethiopia | Ethiopia | Sodo District, Gurage zone | Quantitative: cross-sectional | People with severe mental disorders in a rural community | 300 | 43% | 36 | Not reported | Physical restraint, assault, being beaten, rape, and more | List of Threatening Experiences scale (LTE); 2 questions on restraint; 13 questions on locally established traumatic events, for example, rape, beaten and hit by car | 26.76% serious illness/injury-self; 46.33% restrained; 35.67% locally relevant traumatic events | Primary psychosis, BD and depression with psychotic features | OPCRIT conducted by psychiatric nurses |

| Opekitan 2017 (Opekitan et al., 2017) | Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Partner Characteristics, Socioeconomic Variables, and Intimate Partner Violence in Women with schizophrenia in South–South Nigeria | Nigeria | South–South | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Female outpatients with SCZ | 79 | 100% | 38.3 | Efik/Ibibio (51.0%), Ibos (33.0%), Yorubas (15.0%) and Hausas (1.0%) | IPV | WHO Violence Against Women Instrument | 73.0% | SCZ | SCID |

| Paul 2018 (Paul, 2018) | Are we doing enough? Stigma, discrimination and human rights violations of people living with schizophrenia in India: Implications for social work practice | India | Mumbai | Qualitative | People with SCZ or SCZ-related disorders, family members and mental health professionals | 40 in full sample; 20 with SCZ-related disorder | 50% of people with SCZ | 40.85 for people with SCZ | Not reported | Stigma, discrimination and human rights violations, including physical and emotional violence | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | N/A | SCZ and/or a SCZ-related disorder | Not reported |

| Ponnudurai 2006 (Ponnudurai et al., 2006) | Assessment of mortality and marital status of schizophrenic patients over a period of 13 years | India | Tamil Nadu | Quantitative: cohort | Outpatients with SCZ who died | 60 | 11.67% | 27 for men and 26.7 for women at baseline | Not reported | Death due to accidents | Case notes at the hospital and verbal autopsies confirmed by police reports | 1.67% | SCZ | Independently confirmed by two psychiatrists |

| Ran 2007 (Ran et al., 2007) | Mortality in people with schizophrenia in rural China: 10-year cohort study | China | Xinjin County, Chengdu | Quantitative: cohort | Patients with SCZ in a rural community who are alive and those who died | 500; 98 participants who died | 53.4% of full sample | 44.7 | Not reported | Death due to accidents | Death certificates and verbal autopsies | 2.6% of full sample; 13.3% of the deceased group | SCZ | Present State Examination (PSE) |

| Rani 2023 (Rani et al., 2023) | A Qualitative Study to Understand the Nature of Abuse Experienced by Persons with Severe Mental Illness | India | Bengaluru | Qualitative | Outpatients with SMIs, their caregivers and experts from the community | 51 in full sample; 14 with SMI | 50% of people with SMI | 18–60+, no mean age provided | Not reported | Physical abuse, psychological abuse, sexual abuse, social abuse and trauma in formal care | Key informant interviews and focus group discussions | N/A | SMI: BD, SCZ, SZA and recurrent depressive disorder | Not reported |

| Rani 2023 (Rani et al., 2023) | Profiles of Victimized Outpatients with Severe Mental Illness in India | India | Not reported | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Outpatients with SMI | 150 | 56% | 36.16 | Not reported | Emotional abuse, severe combined abuse, physical abuse and harassment | Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) | 100% experienced emotional abuse, 94% severe combined abuse, 92.7% physical abuse and 54% harassment in the past 12 months | SMI: BD, SCZ, SZA and recurrent depressive disorder | Chart review |

| Read 2009 (Read et al., 2009) | Local suffering and the global discourse of mental health and human rights: An ethnographic study of responses to mental illness in rural Ghana | Ghana | Kintampo | Qualitative and ethnographic methods | People with SMI, their families, healing practitioners and religious leaders within rural communities | 67 in full sample; 25 with SMI | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Chaining, beating and withholding of food | Observation, semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions | N/A | SMI | Not reported |

| Reddy 2020 (Reddy et al., 2020) | Childhood abuse and intimate partner violence among women with mood disorders | India | Bangalore | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Women with SMI vs. healthy women with intimate partners | 251 with SMI and 72 healthy women | 100% | 35.35 for people with SMI | Not reported | Childhood abuse and IPV | Composite Abuse Scale to assess the adulthood IPV | 29.1% severe combined abuse; 37.5% emotional abuse; 47.8% physical abuse; 25.9% harassment in the population with SMI | SMI: unipolar depression and BD | Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist, followed by the MINI |

| Sadath 2014 (Sadath et al., 2014) | Human rights violation in mental health: A case report from India | India | “South India” | Case report | Man with SCZ | 1 | 0% | 41 | Not reported | Solitary confinement in a single room/terrace with no ventilation, sanitary facilities, fed through window and personal care not given for >15 years | Physical identification (case finding) | 100% | Paranoid SCZ | Not reported |

| Sam 2019 (Sam et al., 2019) | Stressful Life Events and Relapse in Bipolar Affective Disorder: A Cross-Sectional Study from a Tertiary Care Center of Southern India | India | Kolenchery, Kerala | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Inpatients with BD | 128 | 43.0% | 40.19 | Not reported | Major personal illness or injury | Presumptive Stressful Life Events Scale (PSLES) | 3.4% | BD: mania and depression | Not reported, beyond stating “ICD‑10 criteria” |

| Subramanian 2017 (Subramanian et al., 2017) | Role of stressful life events and kindling in bipolar disorder: Converging evidence from a mania-predominant illness course | India | “Southern India” | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Inpatients and outpatients with BD | 149 | 52.3% | 37.7 | Not reported | Major personal illness or injury | Presumptive Stressful Life Events Scale (PSLES) | 0.8% | BD | SCID |

| Suryani 2011 (Suryani et al., 2011) | Treating the untreated: Applying a community-based, culturally sensitive psychiatric intervention to confined and physically restrained mentally ill individuals in Bali, Indonesia | Indonesia | Karangasem regency, Bali | Quantitative: cross-sectional | People with SCZ-spectrum disorders in the community | 23 | 13% | 45.1 | Not reported | Restraint with iron shackles, ropes, wooden stocks or wooden cages | Physical identification (case finding) | 91.3% restraint with iron shackles, ropes and wooden stocks; 8.7% confined to wooden cages | SCZ-spectrum disorder | Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist |

| Teferra 2011 (Teferra et al., 2011) | Five-year mortality in a cohort of people with schizophrenia in Ethiopia | Ethiopia | Butajira District, Gurage zone | Quantitative: cohort | Patients with SCZ in a rural community who are alive and those who died | 307; 38 participants who died | 17.9% of the full sample; 10.5% of the deceased group | 35 for the deceased group | Not reported | Death due to traffic accidents | Verbal autopsy | 0.7% of full sample; 5.3% of the deceased group | SCZ | SCAN conducted by a psychiatrist or mental health professional |

| Tsigebrhan 2014 (Tsigebrhan et al., 2014) | Violence and violent victimization in people with severe mental illness in a rural low-income country setting: A comparative cross-sectional community study | Ethiopia | Butajira District, Gurage Zone | Quantitative: cross-sectional | People with SMI and those without in a rural community | 401 in full sample; 201 with SMI and 200 without | 38.8% in the full sample | 40 for the full sample; 40.3 for people with SMI | Not reported | Violent victimization, for example, being kicked, dragged, chained or beaten; threatened or attacked with a weapon; forced to have sexual intercourse | Adapted version of the McArthur Violence Interview | 17.4% in the past 12 months | SMI: SCZ, SZA and BD | SCAN conducted by a psychiatrist or mental health professional |

| Vijayalakshmi 2012 (Vijayalakshmi et al., 2012) | Gender-Related Differences in the Human Rights Needs of Patients with Mental Illness | India | Not reported | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Asymptomatic outpatients with SCZ or mood disorders | 100 | 47.0% | 34.68 | Not reported | Torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; not allowed to leave home; sexual advances by family members | Needs assessment questionnaire based on Universal Declaration of Human Rights | 61.0% sexual advances by family members and 35.0% not allowed to leave their home | Mood disorders or SCZ disorders | Not reported |

| Wang 2020 (Wang et al., 2020) | Frequency and correlates of violence against patients with schizophrenia living in rural China | China | Luoding County, Guangdong | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Outpatients with SCZ in a rural community | 487 | 35.9% | 42.36 | Not reported | Violent victimization in the past 6 months, for example, sexual assault with violence, sexual harassment with physical contacts, verbal harassment with sexual content, nonsexual physical violence and verbal threat and abuse by family members or others | Asked participants | 18.9% experienced 1+ event in the past 6 months | SCZ | Chart reviewed followed by a clinical interview |

| Windarwati 2021 (Windarwati et al., 2021) | A Journey of Hidden Outburst of Anger Shackling a Person with schizophrenia: The Indonesian Context | Indonesia | East Java | Qualitative | People with SCZ, family members, volunteers, prominent figures and nurses | 23 in full sample; 5 with SCZ | 0% of people with SCZ | > 40, no mean age provided | Not reported | Shackling by ankles | Records from regional health office and grounded-theory approach | 100% | SCZ | Not reported |

| Yosep 2021 (Yosep et al., 2021) | How patients with schizophrenia “as a Victim” cope with violence in Indonesia: a qualitative study | Indonesia | West Java | Qualitative | Patients with SCZ from the psychiatric ward of large mental hospitals | 40 | 35.0% | 35.8 | Not reported | Pushing, punching, kicking and restraining | Semi-structured interview | 100% | SCZ | Confirmed diagnosis by a physician |

| Yosep 2021 (Yosep et al., 2021) | Experiences of Violence Among Individuals With schizophrenia in Indonesia a Phenomenological Study | Indonesia | West Java | Qualitative | Patients with SCZ recruited from referral hospitals | 40 | 37.5% | 35.6 | Not reported | Victimization by nurses and family members, including physical and verbal violence | Focus group discussions | N/A | SCZ | Not reported |

| Zerihun 2021 (Zerihun et al., 2021) | Intimate partner violence among reproductive-age women with chronic mental illness attending a psychiatry outpatient department: cross-sectional facility-based study, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | Ethiopia | Addis Ababa | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Female outpatients of reproductive age | 422 | 100% | 32.1 | Not reported | IPV | WHO Violence Against Women Instrument | 44.1% in the past 12 months | SCZ, BD, and severe major depression | Participants recruited from outpatient departments, but diagnosis process not stated |

| Zhang 2018 (Zhang et al., 2018) | Long-Term Outcomes of Unlocking Chinese Patients with Severe Mental Illness | China | Hebei | Quantitative: cohort | Patients with SMI | 107 | 16.82% at baseline | 35.9 at baseline | Not reported | Physical restraint, for example, use of iron chains, iron cage, rope or a separate room or shed | Not reported | 100% at baseline; 19.6% at Time 2 (year 2012); 17.8% at Time 3 (year 2016) | SMI: SCZ, paranoid psychosis and BD | Not reported, beyond stating “ICD‑10 criteria” |

| Zhu 2014 (Zhu et al., 2014) | Frequency of Physical Restraint and Its Associations with Demographic and Clinical Characteristics in a Chinese Psychiatric Institution | China | Hunan | Quantitative: cross-sectional | Inpatients with psychiatric conditions | 160; 85 with SCZ and BP | 50.6% of full sample | 30.0 | Not reported | Physical restraint | Medical records and confirmed by interview | 51.3% | Of the full sample: SCZ, mood disorders and others | Chart review and confirmed by clinical interview |

Acronyms: BP = bipolar disorder; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; IPV = intimate partner violence; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; N/A = not applicable; OPCRIT = Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness; PSE = Present State Examination; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SCZ = schizophrenia; SMI = severe mental illness or serious mental illness; SZA = schizoaffective disorder; WHO = World Health Organization.

Note: the terminology in the table reflects the language the researchers used in their articles, such as SMI.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to synthesize the existing literature on trauma exposure experienced by adults with preexisting SMHCs in LMICs. By including multiple types of studies, we captured a breadth of trauma types and SMHCs that inform the different ways we conceptualize trauma exposure across mental health diagnoses in LMIC settings. The range of sample sizes, sexes represented, age of participants and variation in diagnoses also illustrates the diversity of studies in the field, which may make the findings more reflective of real-world experiences of patients with SMHCs.

Of the 51 included articles, India, Ethiopia and China made up more than 66% of the studies; thus, even though there was a broad range of types of studies and demographics, our understanding of the field derives from a small subset of countries. For example, eight of the nine mortality studies were from India, Ethiopia and China, providing data on traumas that led to death in these populations. Furthermore, with only 10 countries represented in total, there were no data from the more than 120 other LMICs. Though the additional articles outside of India, Ethiopia and China included studies from Southeast Asia, South America and Africa, these regions and the countries within them have diverse populations, geographies and cultures. As such, the studies included may not reflect the full scope of types and frequencies of traumas that people with SMHCs face within and across such heterogeneous LMICs.

Interpersonal violence, which accounted for the majority of studies, emerged as a significant category of traumatic events. Such studies support the notion that people with SMHCs are at additional risk for victimization given their mental health conditions. For example, having an SMHC is associated with social and physical isolation and potential cognitive impairments and/or symptoms (i.e., positive and negative symptoms), which increase the likelihood of being targeted by a perpetrator (de Vries et al., 2019). Alternatively, in many studies family members said they had tied up their loved ones in order to protect them from harm in the community and had no other options given the lack of treatment options and accessible and affordable health care (Asher et al., 2017).

One type of interpersonal violence, “chaining” and “restraining,” represented a significant percentage of events. However, the type of restraint differed widely. While some participants were kept in wooden cages in their community for years, some were in solitary isolation as inpatients for a short period. In both high-income countries (the United States) and in LMICs (Ethiopia and China), people with SMHCs have described restraint as traumatizing (Frueh et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2014; Ametaj et al., 2021). In Uganda, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has described the use of physical, mechanical and chemical restraints and isolation/seclusion in psychiatric facilities in conflict with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ Article 15 (“Freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment” for all people) (OHCHR, 2016).

Even in nonpsychiatric contexts, there is evidence that physical restraint can lead to physical and psychological harm, including PTSD (Franks et al., 2021). The concept of restraint can be controversial, however, because it can be deemed necessary by hospital staff for a patient’s safety depending on an institution’s clinical guidelines. Restraint is also not captured by measures that are often used to assess trauma exposure such as the LEC and the CIDI. Such standardized measures can sometimes fail to capture a wider range of exposures as well as the subjective nature of what is considered traumatic. This may have affected how participants reported traumatic events in these countries.

This is particularly relevant in non-Western settings. Some researchers maintain that the acknowledgment of traumatic events and subsequent traumatic stress is not simply a response to objective experiences, but is shaped by the culture in which one exists and is understood through what is considered traumatic in their setting (Chentsova-Dutton and Maercker, 2019). The value of including qualitative research is that it can augment quantitative reports by offering insights into personal trauma experiences and contextual factors in these settings.

Surprisingly, there were no studies about man-made or natural disasters, such as war, fires and landslides. There is literature about vulnerable populations being left behind in dangerous situations because they are incapable of fleeing, such as the elderly in conflict zones (Murthy and Lakshminarayana, 2006) or during environmental crises like Hurricane Katrina (Dosa et al., 2010). However, none of these trauma types were elicited in this search. It is possible that this is because it is harder to conduct research during events like wars (Cohen and Arieli, 2011), and this absence partially reflects a survival bias. That is, people with SMHCs who died during disasters may not be represented in studies. Despite this, there were mortality studies in the scoping review that captured types of traumas that led to death, somewhat counterbalancing this potential survival bias. Such studies were conducted in more controlled environments in which populations could be followed for years or in countries where there were strong national or regional electronic medical records where accurate patient outcome data could be pulled more easily.

Limitations

There are some limitations that should be noted here. Although we tried to capture an extensive range of trauma types, we know that there are traumas that are culturally relevant in the countries we looked at that might not meet DSM-5 or ICD-11 criteria. While we tried to account for this by including “idioms of distress” and terminology about human rights violations and chaining/restraint, it is likely that there were trauma types that have not been studied by researchers in these contexts or that used different terms from ours that we did not retrieve. In addition, if an article did not include the name of the country in its title or abstract or a grouping term for the countries that met our criteria (i.e., “LMIC” or “East Africa”), we would likely have missed it. We may have missed articles that were not indexed in the American or European databases used here, as some articles from LMICs do not get included in these databases. However, we included Africa-Wide Information/NiPad in order to capture some of the articles that might have been otherwise missed. We limited inclusion to published studies in the interest of completing this scoping review in a timely manner. We acknowledge that excluding gray literature may potentially introduce publication bias. Inclusion of gray literature to address this research question should be considered in a future systematic review. Lastly, we did not include articles with potential mediators between SMHCs and trauma exposure, such as substance use or economic disadvantage. Studies with mediators would be worthwhile to look at in the future.

Conclusion

Future research on trauma types that people with SMHCs are exposed to in LMICs should expand beyond 10 countries to more than 120 additional countries that qualify as LMICs. Research on man-made and natural disasters in this population is warranted. Additional qualitative research may help identify locally relevant trauma types as well as understand people’s lived experiences.

Supporting information

Stevenson et al. supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Supriya Misra, Carol Mita, Carrie G. Wade, Lucia Fernandez, Almalina Gomes and Sofia Paredes.

Footnotes

The ranges here (76.5%–84.3% and 23.3%–34.9%) reflect that some studies collapsed many trauma types into one field. Thus, types of interpersonal violence could not always be teased out from non-interpersonal violence, such as sexual violence vs. road traffic accidents and physical restraint could not always be teased out from non-physical restraint.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.123.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found as a Word document, which is attached to this article.

Data availability

No new data were created as part of this manuscript. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Author contribution

Study conceptualization: AS; Search query development: AS with input from Carol Mita and Carrie G. Wade at Countway Library; First draft of the manuscript: AS; Revising it critically for important intellectual content: AS, EG, BK, BH, KCK and SS; Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work: AS, EG, BK, BH and SS; Final approval of the version to be published: AS, EG, BK, BH, KCK and SS; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: AS, EG, BK, BH, KCK and SS.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

None.

References

- Afe, T. O., Emedoh, T. C., Ogunsemi, O., & Adegbohun, A. A. (2016). Intimate partner violence, psychopathology and the women with schizophrenia in an outpatient clinic south-south, Nigeria. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 197. 10.1186/s12888-016-0898-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alem, A. (2000). Human rights and psychiatric carein Africa with particular referenceto the Ethiopian situation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 101(399), 93–96. 10.1111/j.0902-4441.2000.007s020[dash]21.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluh, D. O., Ayilara, O., Onu, J. U., Pedrosa, B., Santos-Dias, M., Cardoso, G., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., & Grigaite, U. (2022). Experiences and perceptions of coercive practices in mental health care among service users in Nigeria: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 16(1). 10.1186/s13033-022-00565-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ametaj, A. A., Hook, K., Cheng, Y. H., Serba, E. G., Koenen, K. C., Fekadu, A., & Ng, L. C. (2021). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in individuals with severe mental illness in a non-Western setting: Data from rural Ethiopia. Psychological Trauma-Theory Research Practice and Policy, 13(6), 684–693. 10.1037/tra0001006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An, F. R., Sha, S., Zhang, Q. E., Wu, P. P., & Jin, X. (2016). Physical restraint for psychiatric patients and its associations with clinical characteristics and the National Mental Health Law in China. Psychiatry Research, 241 (An F.-R.; Sha S.; Zhang Q.-E.; Wu P.-P.; Jin X.) National Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders & Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University, China(Ungvari G.S.) The University of Notre Dame Australia/Marian Centre, Perth, Australia(Ungv), 154–158. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher, L., Fekadu, A., Teferra, S., De Silva, M., Pathare, S., & Hanlon, C. (2017). “I cry every day and night, I have my son tied in chains”: Physical restraint of people with schizophrenia in community settings in Ethiopia. Globalization and Health, 13. 10.1186/s12992-017-0273-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagewadi, V. I., Kumar, C. N., Thirthalli, J., Rao, G. N., Suresha, K. K., & Gangadhar, B. N. (2016). Standardized mortality ratio in patients with schizophrenia – Findings from Thirthahalli: A rural south Indian community. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(3), 202–206. 10.4103/0253-7176.183083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belete, H. (2017a). Leveling and abuse among patients with bipolar disorder at psychiatric outpatient departments in Ethiopia. Annals of General Psychiatry, 16, 29. 10.1186/s12991-017-0152-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belete, H. (2017b). Use of physical restraints among patients with bipolar disorder in Ethiopian mental specialized hospital, outpatient department: Cross-sectional study. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 5. 10.1186/s40345-017-0084-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, A. (2022). “The day I die is the day I will find my peace”: Narratives of family, marriage, and violence among women living with serious mental illness in India. Violence Against Women, 28(3–4), 966–990. 10.1177/10778012211012089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, P. S., Carey, M. P., Carey, K. B., Shalinianant, A., & Thomas, T. (2003). Sexual coercion and abuse among women with a severe mental illness in India: An exploratory investigation. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 44(3), 205–212. 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00004-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, P. S., Deepthivarma, S., Carey, M. P., Carey, K. B., & Shalinianant, M. P. (2003). A cry from the darkness: Women with severe mental illness in India reveal their experiences with sexual coercion. Psychiatry-Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 66(4), 323–334. 10.1521/psyc.66.4.323.25446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chentsova-Dutton, Y., & Maercker, A. (2019). Cultural scripts of traumatic stress: Outline, illustrations, and research opportunities [Hypothesis and theory]. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, N., & Arieli, T. (2011). Field research in conflict environments: Methodological challenges and snowball sampling. Journal of Peace Research, 48(4), 423–435. 10.1177/0022343311405698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cumpston, M., Lasserson, T., Flemyng, Ella., & Page, M.J., (2022). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3: Chapter III: Reporting the review. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-iii. Accessed March 19, 2023.

- de Oliveira, H. N., Machado, C. J., & Guimaraes, M. D. C. (2013). Physical violence against patients with mental disorders in Brazil: Sex differences in a cross-sectional study. Revista de Psiquiatria Clinica, 40(5), 172–176. 10.1590/S0101-60832013000500002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, B., van Busschbach, J. T., van der Stouwe, E. C. D., Aleman, A., van Dijk, J. J. M., Lysaker, P. H., Arends, J., Nijman, S. A., & Pijnenborg, G. H. M. (2019). Prevalence rate and risk factors of victimization in adult patients with a psychotic disorder: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 45(1), 114–126. 10.1093/schbul/sby020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosa, D., Feng, Z., Hyer, K., Brown, L. M., Thomas, K., & Mor, V. (2010). Effects of hurricane Katrina on nursing facility resident mortality, hospitalization, and functional decline. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 4 Suppl 1(0 1), S28–32. 10.1001/dmp.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundar, Y., & Fleeman, N. (2017). Developing my search strategy. In Boland A., Dickson R., & Cherry G. (Eds.), Doing a Systematic Review (pp. 61–78). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- El Missiry, A., El Meguid, M. A., Abourayah, A., El Missiry, M., Hossam, M., Elkholy, H., & Khalil, A. H. (2019). Rates and profile of victimization in a sample of Egyptian patients with major mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 65(3), 183–193. 10.1177/0020764019831315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekadu, A., Medhin, G., Kebede, D., Alem, A., Cleare, A. J., Prince, M., Hanlon, C., & Shibre, T. (2015). Excess mortality in severe mental illness: 10-year population-based cohort study in rural Ethiopia. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(4), 289–296. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.149112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekry, M. (2011). Clinical and psychodemographic profile of victimized versus nonvictimized Egyptian patients with bipolar mood disorder. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 19, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, Z. M., Alcock, J. A., Lam, T., Haines, K. J., Arora, N., & Ramanan, M. (2021). Physical restraints and post-traumatic stress disorder in survivors of critical illness. A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 18(4), 689–697. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-738OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueh, C., Knapp, R. G., Cusack, K. J., Grubaugh, A. L., Sauvageot, J. A., Cousins, V. C., Yim, E., Robins, C. S., Monnier, J., & Hiers, T. G. (2005). Special section on seclusion and restraint: Patients’ reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatric Services, 56(9), 1123–1133. 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmoor, A. R., Vallath, S., Regeer, B., & Bunders, J. F. G. (2020). “If somebody could just understand what I am going through, it would make all the difference”: Conceptualizations of trauma in homeless populations experiencing severe mental illness. Transcultural Psychiatry, 57(3), 455–467. 10.1177/1363461520909613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda, G. S., Lepping, P., Noorthoorn, E. O., Ali, S. F., Kumar, C. N., Raveesh, B. N., & Math, S. B. (2018). Restraint prevalence and perceived coercion among psychiatric inpatients from South India: A prospective study. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 36, 10–16. 10.1016/j.ajp.2018.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh, A. L., Zinzow, H. M., Paul, L., Egede, L. E., & Frueh, B. C. (2011). Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in adults with severe mental illness: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 883–899. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, L., Liu, J., Wu, X. M., Chen, D., Wang, X., Ma, N., Wang, Y., Good, B., Ma, H., Yu, X., & Good, M. J. (2015). Unlocking patients with mental disorders who were in restraints at home: A national follow-up study of china’s new public mental health initiatives [Article]. PLoS One, 10(4). 10.1371/journal.pone.0121425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidayat, M. T., Oster, C., Muir-Cochrane, E., & Lawn, S. (2023). Indonesia free from pasung: A policy analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 17(1), 12. 10.1186/s13033-023-00579-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. L., Wang, Q., Wang, Y. H., Gu, L. X., & Yu, T. G. (2022). A retrospective analysis of death among Chinese Han patients with schizophrenia from Shandong. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 15, 403–414. 10.2147/RMHP.S351523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakhar, K., Bhatia, T., Saha, R., & Deshpande, S. N. (2015). A cross sectional study of prevalence and correlates of current and past risks in schizophrenia. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 14, 36–41. 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C., & Üstün, T. B. (2004). The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(2), 93–121. 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, P., Johansson, E., Okello, E., Allebeck, P., & Thorson, A. (2012a). Sexual risk behaviours and sexual abuse in persons with severe mental illness in Uganda: A qualitative study. PLoS One, 7(1), e29748. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, P., Nakasujja, N., Musisi, S., Thorson, A. E., Cantor-Graae, E., & Allebeck, P. (2015). Sexual risk behavior, sexual violence, and HIV in persons with severe mental illness in Uganda: Hospital-based cross-sectional study and National Comparison Data. American Journal of Public Health, 105(6), 1142–1148. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglio, R. (2009). Severe mental illness and criminal victimization: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 119(3), 180–191. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjunatha, N., Kumar, C. N., Thirthalli, J., Suresha, K. K., Harisha, D. M., & Arunachala, U. (2019). Mortality in schizophrenia: A study of verbal autopsy from cohorts of two rural communities of South India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(3), 238–243. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_135_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauritz, M. W., Goossens, P. J. J., Draijer, N., & van Achterberg, T. (2013). Prevalence of interpersonal trauma exposure and trauma-related disorders in severe mental illness. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 19985. 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.19985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, A. P. S., Dippenaar, I. N., Johnson, S. C., Weaver, N. D., Acurcio, F. D. A., Malta, D. C., Ribeiro, A. L. P., Guerra, A. A., Jr., Wool, E. E., Naghavi, M., & Cherchiglia, M. L. (2022). All-cause and cause-specific mortality among people with severe mental illness in Brazil’s public health system, 2000-15: A retrospective study. Lancet Psychiatry, 9(10), 771–781. 10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercy, J., Hillis, S., Butchart, A., Bellis, M., Ward, C., Fang, X., & Rosenberg, M. (2017). Interpersonal Violence: Global Impact and Paths to Prevention (3rd ed.). The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. 10.1596/978-1-4648-0522-6_ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minas, H., & Diatri, H. (2008). Pasung: Physical restraint and confinement of the mentally ill in the community [Article]. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 2. 10.1186/1752-4458-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai, R., Varma, V. K., Malhotra, S., Mattoo, S. K., Misra, A. K., Wig, N. N., & Susser, E. (2001). Mortality and long-term course in schizophrenia with a poor 2-year course: A study in a developing country. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 178(1), 71–75. 10.1192/bjp.178.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moodley, L., Ntlantsana, V., Tomita, A., & Paruk, S. (2023). The missed pandemic: Intimate partner violence in female mental-health-care-users during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology Health & Medicine. 10.1080/13548506.2023.2206143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpango, R. S., Ssembajjwe, W., Rukundo, G. Z., Amanyire, P., Birungi, C., Kalungi, A., Rutakumwa, R., Tusiime, C., Gadow, K. D., Patel, V., Nyirenda, M., & Kinyanda, E. (2023). Physical and sexual victimization of persons with severe mental illness seeking care in central and southwestern Uganda. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1167076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, R. S., & Lakshminarayana, R. (2006). Mental health consequences of war: A brief review of research findings. World Psychiatry, 5(1), 25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair, S., Satyanarayana, V. A., & Desai, G. (2020). Prevalence and clinical correlates of intimate partner violence (IPV) in women with severe mental illness (SMI). Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, L. C., Medhin, G., Hanlon, C., & Fekadu, A. (2019). Trauma exposure, depression, suicidal ideation, and alcohol use in people with severe mental disorder in Ethiopia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(7), 835–842. 10.1007/s00127-019-01673-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHCHR (2016) CRPD/C/UGA/CO/1: Concluding observations on the initial report of Uganda. United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/concluding-observations/crpdcugaco1-concluding-observations-initial-report-uganda

- Opekitan, T., Emedoh, T. C., Ogunsemi, O. O., & Adegohun, A. A. (2017). Socio-demographic characteristics, partner characteristics, socioeconomic variables, and intimate partner violence in women with schizophrenia in south-South Nigeria. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(2), 707–720. 10.1353/hpu.2017.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S. (2018). Are we doing enough? Stigma, discrimination and human rights violations of people living with schizophrenia in India: Implications for social work practice. Social Work in Mental Health, 16(2), 145–171. 10.1080/15332985.2017.1361887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 19(1), 3–10. 10.1097/xeb.0000000000000277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnudurai, R., Jayakar, J., & Sathiya Sekaran, B. W. (2006). Assessment of mortality and marital status of schizophrenic patients over a period of 13 years. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 48(2), 84–87. 10.4103/0019-5545.31595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran, M. S., Chen, E. Y., Conwell, Y., Chan, C. L., Yip, P. S., Xiang, M. Z., & Caine E. D. (2007). Mortality in people with schizophrenia in rural China: 10-year cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 237–242. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani, A., Raman, K. J., Antony, S., Thirumoorthy, A., & Basavarajappa, C. (2023). Profiles of victimized outpatients with severe mental illness in India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 48(6), 920–925. 10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_915_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani, A., Raman, K. J., Antony, S., Thirumoorthy, A., & Chethan, B. (2023). A qualitative study to understand the nature of abuse experienced by persons with severe mental illness. Violence and Gender. 10.1089/vio.2022.0046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Read, J., van Os, J., Morrison, A. P., & Ross, C. A. (2005). Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: A literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112(5), 330–350. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read, U. M., Adiibokah, E., & Nyame, S. (2009). Local suffering and the global discourse of mental health and human rights: An ethnographic study of responses to mental illness in rural Ghana. Globalization and Health, 5, 13. 10.1186/1744-8603-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, P. V., Tansa, K. A., Raj, A., Jangam, K., & Muralidharan, K. (2020). Childhood abuse and intimate partner violence among women with mood disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 272, 335–339. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadath, A., Narasimha, V. M., Rao, M., Kumar, V., Muralidhar, D., Varambally, S., Gangadhar, B. N., Kori, A., & Supraja, A. (2014). Human rights violation in mental health: A case report from India. African Journal of Psychiatry, 17(3), 1–2. http://ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2014-36342-006&site=ehost-live&scope=siteani00711@yahoo.com [Google Scholar]

- Sam, S. P., Nisha, A., & Varghese, P. J. (2019). Stressful life events and relapse in bipolar affective disorder: A cross-sectional study from a tertiary Care Center of Southern India. Indian Journal of Psychology Medicine, 41(1), 61–67. 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_113_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, K., Sarkar, S., Kattimani, S., Philip Rajkumar, R., & Penchilaiya, V. (2017). Role of stressful life events and kindling in bipolar disorder: Converging evidence from a mania-predominant illness course. Psychiatry Research, 258, 434–437. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryani, L. K., Lesmana, C. B. J., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2011). Treating the untreated: Applying a community-based, culturally sensitive psychiatric intervention to confined and physically restrained mentally ill individuals in Bali, Indonesia [article]. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 261(SUPPL. 2), S140–S144. 10.1007/s00406-011-0238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teferra, S., Shibre, T., Fekadu, A., Medhin, G., Wakwoya, A., Alem, A., Kullgren, G., & Jacobsson, L. (2011). Five-year mortality in a cohort of people with schizophrenia in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry, 11, 165. 10.1186/1471-244x-11-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., & Hempel, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/m18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigebrhan, R., Shibre, T., Medhin, G., Fekadu, A., & Hanlon, C. (2014). Violence and violent victimization in people with severe mental illness in a rural low-income country setting: A comparative cross-sectional community study. Schizophrenia Research, 152(1), 275–282. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Schoot, R., de Bruin, J., Schram, R., Zahedi, P., de Boer, J., Weijdema, F., Kramer, B., Huijts, M., Hoogerwerf, M., Ferdinands, G., Harkema, A., Willemsen, J., Ma, Y., Fang, Q., Hindriks, S., Tummers, L., & Oberski, D. L. (2021). An open source machine learning framework for efficient and transparent systematic reviews. Nature Machine Intelligence, 3(2), 125–133. 10.1038/s42256-020-00287-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]