Abstract

One of the most popular instruments used to assess perceived social support is the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). Although the original structure of the MSPSS was defined to include three specific factors (significant others, friends and family), studies in the literature propose different factor solutions. In this study, we addressed the controversial factor structure of the MSPSS using a meta-analytic confirmatory factor analysis approach. For this purpose, we utilized studies in the literature that examined and reported the internal structure of the MSPSS. However, we used summary data from 59 samples of 54 studies (total N = 27,905) after excluding studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. We tested five different models discussed in the literature and found that the fit indices of the correlated 3-factor model and the bifactor model were quite good. Therefore, we also examined both models’ factor loadings and omega coefficients. Since there was no sharp difference between the two models and the theoretical structure of the scale was represented by the correlated three factors, we decided that the correlated three-factor model was more appropriate for the internal structure of the MSPSS. We then examined the measurement invariance for this model according to language and sample type (clinical and nonclinical) and found that metric invariance was achieved. As a result, we found that the three-factor structure of the MSPSS was supported in this study.

Keywords: social support, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, meta-analytic confirmatory factor analysis, measurement invariance, factor structure

Impact statement

There are various measurement tools that can measure different concepts of social support. The purpose of this study is to test the factor structure of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), one of the most frequently used instruments for measuring perceived social support, using meta-analytic confirmatory factor analysis. In this way, we sought to answer the debates about the internal structure of this measurement tool and obtained some evidence about its reliability and dimensionality. According to this evidence, the MSPSS has a three-factor structure. It has high internal consistency and measurement invariance according to language and sample type (clinical and nonclinical).

Introduction

Since anything that people can exchange can act as a source of social support (Waite, 2018), social support is considered a multifaceted concept. Therefore, there are different views in the literature on how to conceptualize this concept. The psychological perspective divides social support into two types: perceived and received social support (Vangelisti, 2009). The subjective assessment that one’s social networks will provide effective help when needed is known as perceived support (Lakey & Scoboria, 2005). Demonstrated support refers to actual and spontaneous helping behaviors (Norris & Kaniasty, 1996). Studies in the literature reveal that there is only a modest correlation between measures of these two types of support (Eagle et al., 2019; Haber et al., 2007; Lakey et al., 2010). However, compared to received support, perceived support is reported to be more strongly associated with positive health outcomes (Barrera, 2000; Eagle et al., 2019; Uchino, 2009). In a meta-analysis study by Prati and Pietrantoni (2010), it was found that not all forms of support have the same effect on mental health and perceived support has a greater effect than received support. In addition, Moreira et al. (2003) stated that perceived social support can best be seen as an individual difference variable because it remains relatively constant over long periods. Therefore, in the present study, the measurements of perceived social support, which is a more prominent substructure in addressing the concept of social support, were examined. Although there are different instruments for the measurement of perceived social support in the literature (e.g., Perceived Social Support, Friends and Perceived Social Support, Family (Procidano & Heller, 1983); Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (Malecki & Demaray, 2002); Student Social Support Scale (Malecki & Elliott, 1999), this study focussed on the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), which is considered to represent the construct of perceived social support more strongly and is widely used in international studies (Zimet et al., 1988). It has been determined that this measurement tool has received nearly 17,000 citations so far.

The multidimensional scale of perceived social support

The MSPSS was originally designed as a 24-item and 5-point Likert scale. It was created and piloted by American university students. Following several pilot studies, it was determined that the scale needed to be modified. The items were updated, and the scale’s final form was produced (Zimet et al., 1988). Following their research, the researchers concluded that the MSPSS only included 12 items and was broken down into three separate categories of social support: significant others (SO), friends (FRI) and family (FAM). This 12-item scale has a 7-point response format; with responses ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree) and is comprised of three 4-item subscales. A higher score on the subscale indicates a higher perception of support. It was determined that the original version of the MSPSS had a three-factor structure, and the internal consistency coefficient and stability coefficient were high. In addition, since MSPSS scores were negatively correlated with anxiety and depression scores, it was stated that it showed moderate construct validity (Zimet et al., 1988).

Due to its many advantages, the MSPSS has been used in many social support studies worldwide. The most important advantage of the scale is that while other scales measuring the perceived social support structure address the FAM, FRI and SO dimensions separately, MSPSS addresses these three dimensions together. While the FAM dimension includes parents, spouses, children and siblings, the SO dimension includes people other than family and friends (e.g., date, fiancee, relative, neighbor and doctor) (Eker et al., 2001). The short and comprehensible items of the scale and the fact that it is a self-report scale that is not time-consuming are also among its advantages. In addition, MSPSS is psychometrically sound (Zimet et al., 1988). However, alternative factor structures for the MSPSS, which have been adapted to other cultures and groups, have also been discussed in the literature.

Although the unidimensional model is not suitable for the theoretical infrastructure of the scale, Akhtar et al. (2010) in their study with Pakistani women determined that the Urdu version of the MSPSS showed a unidimensional structure. Two different models are proposed for the 2-factorial model. Chou (2000) expressed a separate FAM factor as a second factor in addition to a factor consisting of a combination of FRI and SO items. They claimed that the most comprehensible answer was obtained using this two-factor structure. In a similar vein, Cheng and Chan (2004) concluded that the original 3-factor model could be countered by the 2-factor structure created by combining the FRI and SO subscales. Wang et al. (2017) also determined the factor structure of the MSPSS with exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and determined the FAM factor as a separate factor in addition to a factor consisting of the items of the SO and FRI subscales. Other researchers suggested a 2-factor structure considering FAM and SO items in a single factor. Tonsing, Zimet and Tse (2012) determined that a 2-factor structure, FAM (FAM and SO items) and FRI, was appropriate for the Urdu version of MSPSS. Mohammad et al. (2015) found a very high correlation value between FAM and SO, so they combined these two factors under the FAM factor and determined that the 2-factor solution was confirmed. Other studies reached acceptable results for the 2-factor solution, with the first factor mainly consisting of the items in the FAM and SO subscales and the second factor mainly consisting of the items in the FRI subscale (Cobb & Xie, 2015; Stanley et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2015). In 2-factor structures, it is seen that the SO subscale is included in other subscales. It is suggested that this might be because the subjects were unable to differentiate between SO and other supportive individuals like FRI and FAM (Wongpakaran et al., 2011).

The original 3-factor structure of the scale was tested and validated in many studies (Bruwer et al., 2008; Calderón Garrido et al., 2021; Canty-Mitchell, & Zimet, 2000; Cartwright et al., 2022; Duru, 2007; Ebrahim & Alothman, 2022; Edwards, 2004; Eker et al., 2001; Ermis-Demirtas et al., 2018; Laksmita et al., 2020; Pedersen et al., 2009; Pérez-Villalobos et al., 2021; Robu et al., 2020; Tonsing, 2022; Tonsing et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2017). However, in some studies, the original 3-factor structure was confirmed by modifications (Başol, 2008; Martins et al., 2012; Sharif et al., 2021; Trejos-Herrera et al., 2018; Wongpakaran et al., 2011). It can be said that all these studies conducted in different languages (e.g., Arabic, Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, Swedish and Turkish) offer strong proof for the generalizability of the scale’s three-factor structure. However, the fact that some studies encountered different situations in the SO subscale (e.g., low factor saturation) (Cheng & Chan, 2004; Edwards, 2004) may indicate that the 3-factor solution is not a good-enough representation of the MSPSS. In addition, the correlation values of .80 and above between FAM, FRI and SO factors in some studies (e.g., Iwanaga et al., 2021; Merino-Soto et al., 2022; Pérez-Villalobos et al., 2021) suggest that there may be a general factor in addition to these three factors.

Later, the factor structure of the scale is also discussed through more recent models such as the bifactor and/or exploratory structural equation model (ESEM). For example, Osman et al. (2014) used the item response theory (IRT) bifactor method. The researchers concluded that there was insufficient empirical basis to calculate the subscale scores of any of the MSPSS-specific factors because the discrimination parameter of each MSPSS item was greater on the general factor than on a group-specific factor. They concluded that the MSPSS offers solid evidence in favor of its application as a unidimensional instrument based on these findings. On the other hand, Merino-Soto et al. (2022), and Yılmaz Koğar and Koğar (2023) investigated the MSPSS factor structure using bifactor and ESEM techniques in addition to the models previously presented. They concluded from the study that, except the unidimensional model, all other models demonstrated a high degree of model-data fit; nonetheless, the multidimensionality indicators corroborated the superiority of the bifactor-ESEM. Conversely, it was found that the inter-factorial correlations were significantly low, and the general factor was insufficiently strong. It was determined that separate but moderately correlated components might explain the MSPSS and that the presence of potential systematic variations might make it impossible to identify a general factor.

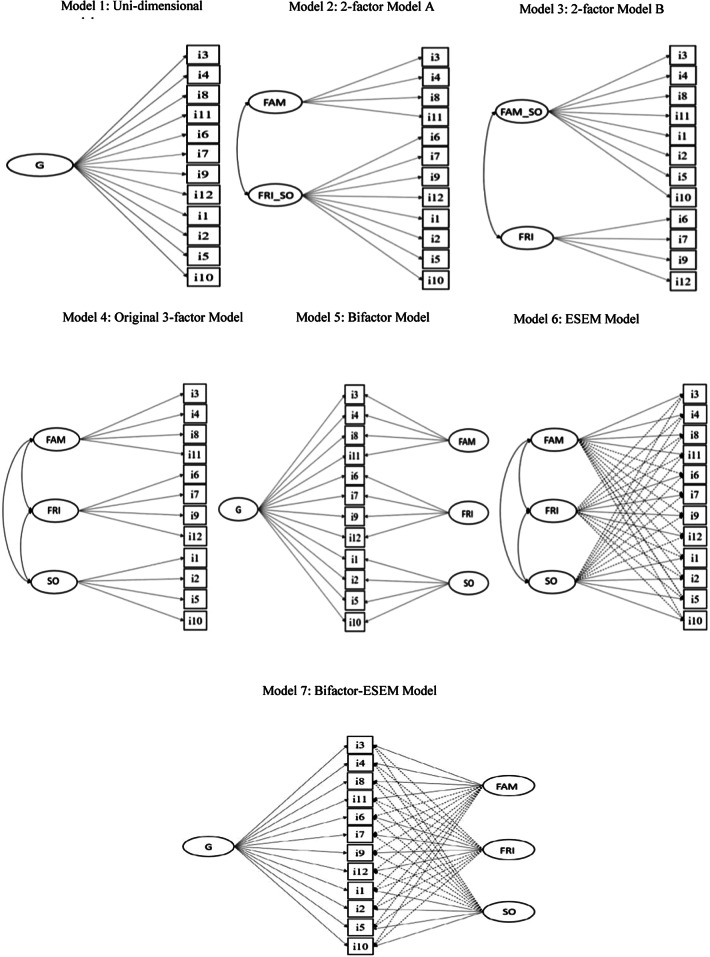

These studies collectively demonstrate that various conclusions are drawn regarding the scale’s factor structure. All models discussed for the MSPSS in the literature are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual representation of all models tested for MSPSS in the literature.

Note. G = general factor; FAM = family support; FRI_SO = friends and significant others support; FAM_SO = family and significant others support; SO = significant others support.

The current study

Although the MSPSS was created in 1988, the psychometric properties of the scale are still the focus of research in various cultures and groups. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the factor structure of the scale on a larger sample and to quantitatively synthesize the factor analysis results of previous studies with the help of meta-analytic confirmatory factor (MA-CFA) analysis. To our knowledge, this meta-analytic factor approach has not yet been evaluated for the MSPSS. The compatibility of the scale structure with the bifactor model has not been examined in the majority of studies evaluating the original factor structure. Examining the bifactor model, which has been widely used to address constructs in psychology, through the findings of these other studies may help to better determine the factor structure of the MSPSS. We think that it would be important for the literature to present a more general result of the structure emerging from this scale, which has been adapted in many cultures and used very frequently. We also examined whether the MSPSS is interpreted in a conceptually similar way using a test of measurement invariance (MI) across language and sample type because it is necessary to provide a prerequisite for meaningful comparisons between groups. The construct validity of the MSPSS may be affected by translations of the scale from the original language into other languages, as cultural differences are likely to affect how social support is perceived (Dambi et al., 2018). In this respect, we examined the invariance of the factor structure of the scale for the groups we formed according to the language. In addition, the fact that we determined that the MSPSS is frequently used in clinical and nonclinical samples in the literature led us to question whether these groups are comparable. For this reason, we also examined the invariance of the scale over the groups we formed according to the sample type variable. We designed the study to combine the results obtained from more recent studies with those obtained from previous studies. We aim that the findings of the study will provide some data that can help explain the theoretical foundations of the perceived social support structure and contribute to the accumulation of knowledge.

Method

Database, coding and screening

To answer the research questions of this study, a literature search was conducted on many major scientific databases (PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science and Google Scholar). In September–October 2022, the literature was searched using the Boolean Operator (MSPSS OR “the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support”) AND (“valid*” OR “factor analysis” OR “factor structure” OR “psychometric” OR “adaptation”) to reach potential articles and 13,794 scientific studies were reached. The titles, abstracts and tables of these scientific publications were scanned and examined whether they had the following 5 criteria: Each study (a) should be written in English, (b) should be an original study (thesis and conference papers could not be found so all studies are articles), (c) should use the original MSPSS with 12 items and (d) should include loading patterns or covariance/correlation matrix (inter-item correlation matrices, etc.). (e) In the studies, the rotation method should be reported; if oblique rotation was used, correlations between factors should be included. If orthogonal rotation was used, the correlation between factors was accepted as zero.

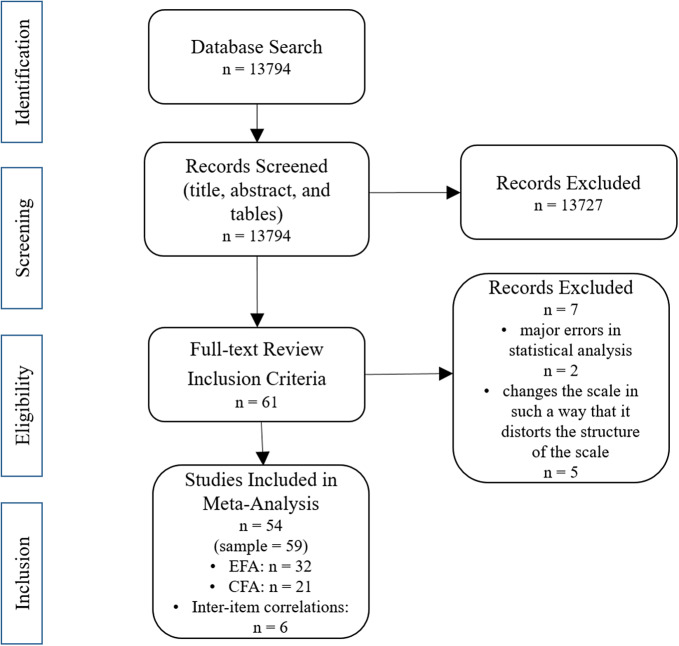

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Page et al., 2021) guidelines were adhered to during this procedure, and reporting was done under these guidelines. The PRISMA checklist is shown in supplementary files. A total of 61 different articles that met the relevant criteria were reached. However, studies that addressed the scale in a way that would change its structure addressing the general population were removed from the database. This situation was experienced in the “significant others” factor. It was observed that this factor was given different names according to the type of sample studied. While studies on the women sample gave this dimension names such as husband and spouse, studies conducted on students gave names such as school staff and professor. We decided to exclude these studies because we thought that the reduction of this factor to a person or specific individuals could affect the structure of the scale. In addition, studies that reported incomplete statistical analyses, that provided almost no information about how the factor analysis was applied, that did not report any reliability coefficients and whose model-data fit indices did not meet the criteria recommended in CFA were also excluded. In this case, the number of articles used for the study decreased to 54. We used the factor loadings obtained from the EFA findings of 32 studies, the standardized regression coefficients obtained from the CFA findings of 21 studies and the inter-item correlation values of 6 studies in 59 samples. More details can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Literature search summary.

However, some studies that altered the structure of the scale (e.g., different factor naming) or were found to have inadequate and/or incomplete reporting in statistical analyses were also excluded, reducing the number of articles used for the study to 54. Studies that used different factor naming also changed the item writing significantly. Since we think that this situation affects the factor structure of the scale, we decided to exclude these studies as well. Studies with a very small sample size (<50) and almost no information on how factor analysis was applied were also excluded from the database. Studies with reliability coefficients below 0.70 or model-data fit indices that did not meet the recommended criteria in CFA were also removed from the database. A database was created with a total of 59 samples from these 54 studies. The factor loadings obtained from the EFA findings from 32 studies, the standardized regression coefficients obtained from the CFA findings from 21 studies and the inter-item correlation values from 6 studies were used from 59 samples. More details are in Figure 2.

Inter-coder reliability for all variables was examined with Cohen’s kappa and inter-coding correlation. The median value of the inter-coding correlation was .98, and the median value of Cohen’s kappa was .99. In the event of a disagreement between the two coders, this disagreement was settled through conversation. If the inter-item correlation values were present in the article, they were undoubtedly used during the data coding process. Six studies have reported inter-item correlations. In other articles, the results of the EFA were prioritized over those of the CFA when they were applied to the same sample. Since there were no limitations in parameter estimation and factor structure testing in EFA, EFA findings were prioritized over CFA. If a rotation technique was used in studies presenting EFA findings, factor loadings of the factor structure obtained after rotation were taken into consideration. The results of the factor structure with the best model-data fit were included in the database if more than one CFA finding was applied to the same sample in an article (to test several factor structures). The multigroup CFA results that were used to test MI were not included in the analysis. Moreover, articles that lacked necessary details (such as model-data fit) were not included in the study. Also, descriptive data regarding the sample (such as the participants’ countries of origin, sample size and average age) and reported factor analysis were gathered (i.e., number of response options and rotation method). Access to the Excel file containing this data is available in the supplementary materials.

MA-CFA procedure

MA-CFA was developed by combining two different disciplines. These two discipline areas are meta-analysis and structural equation modeling (SEM). To apply the traditional meta-analysis, it is necessary to reach all published and unpublished studies. However, MA-CFA can also be used with a small number of samples and a sufficient sample size. According to Strunk and Lane (2017), at least 10 samples and a sample size of 1,500 people are needed to reproduce the population parameters. In our study, 59 different samples were reached and the total sample size was 27,905. For this reason, it was decided that MA-CFA could be applied to our database.

Based on the supplied factor pattern matrices, we computed the item-level correlations that the model implies. Since Monte Carlo simulations showed that this method produces unbiased estimates of meta-analytic factor patterns, missing values were handled via imputed factor loadings, which were given a value of zero in the case of missing values (Gnambs & Staufenbiel, 2016). However, our database does not include any study with missing factor loadings or not reported because the factor loading is too small. In the first stage of MA-CFA, using random-effects meta-analysis, a pooled correlation matrix was produced. Because random-effects meta-analysis yields more accurate parameter estimates than fixed-effects techniques, it was selected as the method of choice (Field, 2005; Hunter & Schmidt, 2004). The generated pooled correlation matrix was put through factor analytic models in the second MA-CFA stage. EFA was used for this, and Horn’s (1965) parallel analysis tests and the minimal average partial (MAP) test were used to find the ideal factor number. In the third stage, CFA was applied to 5 different competitive models, taking into account the dimensionality analysis findings and factor structures tested for the MSPSS in the literature (see Figure 1, Models 1–5). According to Schermelleh-Engel et al.’s (2003) suggested cutoff points, the overall model fit for each tested model was evaluated using the following metrics: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) (≥ .97, desirable, and ≥ .95, acceptable), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; ≤ .05, good fit; ≤ .08, acceptable fit) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; ≤ .05, good fit; ≤ .10, acceptable fit). Model fit was determined by taking into consideration the values of CFI, TLI, RMSEA and SRMR, as the chi-square test is highly sensitive to sample size. Furthermore, the factor loadings derived from every model were scrutinized to ascertain the degree of well-definedness of the pertinent component. According to Gaskin and Happell (2014), factor loadings of at least ± .40 were recognized as a sign of a well-defined factor. As long as the factor loadings are .40 and above, the model with the best model-data fit will be accepted as the “actual” factor structure of MSPSS. All CFAs were conducted with the weighted least squares (WLS) estimator. After determining the factor structure that best describes the factor structure of MSPSS from these 5 competitive models, factor loadings, omega coefficients and the explained common variance (ECV) coefficient were calculated for the relevant factor structure. The scale is effectively unidimensional because the subscales’ omega coefficients are small (<.50) and the general factor’s omega coefficient is bigger than .75 (Reise, Bonifay et al., 2013). The scale can be regarded as almost unidimensional when the ECV, or the percentage of common variance in a bifactor model attributed to the general factor, is high (>.60) (Reise, Scheines et al., 2013). The Bifactor Indices Calculator Excel file was utilized to compute the omega coefficients and ECV values (Dueber, 2017).

Follow-up analyses were initiated when the best factor structure for the scale was chosen. MI was examined for this aim using language samples as well as clinical and nonclinical samples. MI was tested between English (k = 9, n = 2,710), and the 5 other most used languages (Chinese, Spanish, Malay, Turkish and Urdu [k = 20, n = 10,849]). This approach aims to identify structural deterioration brought on by adaptations and the data set gathered from the clinical setting. The testing of a group of hierarchically nested models, each with a distinct set of constraints on the measurement parameters examined, is the basis of the MI process. The only invariance models that have been tested for MI are the configural model (Model 1), which has the same number of factors and item-factor loading patterns, and the metric model (Model 2), which has identical factor loadings. This is because strong MI is based on comparing factor variance, covariance and mean. With strong factorial invariance, the means of the factors can be meaningfully compared across the groups. However, in this MI study conducted on summary data (correlation matrix), only configural and metric MI was tested since the mean information was not included. Next, the CFI differences between the more constrained and less constrained models (ΔCFI = CFIconstrained model – CFIunconstrained model) and RMSEA differences (ΔRMSEA = RMSEAconstrained model – RMSEAunconstrained model) were analyzed. MI would be indicated by an RMSEA difference of less than .015 and an absolute difference in CFI of less than or equal to .01 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

All the R codes of this study were written by reconsidering the R codes in Schroeders et al.’s (2022) study. Analysis of dimensionality, pooled correlation matrix and all MASEM procedures were performed with psych package 2.2.9 (Revelle, 2022), metaSEM package 1.2.5.1 (Cheung, 2022) and lavaan package 0.6 (Rosseel, 2012). MI was tested on Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017).

Findings

Study descriptions

As stated in the method section of our study, the findings of a total of 59 samples included in 54 unique articles formed the database of this research. These studies were published between 1988, when MSPSS was developed, and 2022. The total sample size of the database is 27,905 (min = 50; max = 2,105; median = 310). Women constitute 59.2% of the whole group. The average age is 32.7. Of the 59 samples, 16 were clinical sample data. This finding shows that cross-cultural studies of MSPSS are mostly carried out on nonclinical samples. While 53 of the 59 samples used 7 response options, which is the number of response options belonging to the original MSPSS, 3 of the studies preferred to use the 4-point response option, 2 of the studies preferred to use the 5-point response option, and one study preferred to use the 6-point response option.

While 7 of the samples were in the USA, 5 of the samples were in Malaysia and 3 of the samples were in China, Singapore, Romania and Türkiye. The most used languages are English (9), Chinese (5), Spanish (5), Malay (4), Turkish (3), Urdu (3) and Romanian (3). The list of included articles and more information about study characteristics can be found in the supplementary files.

Dimensionality analysis

A pooled correlation matrix was produced utilizing factor loadings, normalized regression coefficients and inter-item correlation values derived from various database samples prior to the analyses performed to ascertain the number of dimensions of the MSPSS. In the pooled correlation matrix, the correlation coefficients vary from .196 to .841. The correlation coefficients had an average value of .380.

The factor structure of MSPSS was determined as 3 factors in 47 samples according to EFA and CFA findings, which were applied to 59 samples in the database (since only inter-item correlations were used, EFA and CFA findings of 6 samples were not taken into account). The original factor structure of MSPSS also includes 3 factors. A 2-factor structure was obtained in 5 samples, and a unidimensional structure was obtained in only 1 sample. In this case, it was necessary to perform dimensionality analyses first with the obtained pooled correlation matrix. Auerswald and Moshagen’s (2019) simulation study suggests traditional parallel analysis. For this purpose, the MAP test and Horn’s (1965) parallel analysis tests were applied. Both dimensionality analysis tests showed that a 3-factor structure had the best fit with the data. Although this finding is preliminary evidence that the MSPSS has a 3-factor structure, some recent studies (see Merino-Soto et al., 2022; Yılmaz Koğar & Koğar, 2023) have shown that there may be different alternatives in the 3-factor structure (i.e., bifactor-CFA, ESEM and bifactor-ESEM). However, since ESEM could not be tested on the summary data (in our study: inter-item correlation matrix), ESEM models were excluded from this study. For this reason, CFA was applied to 5 competitive models to test the factor structure of MSPSS.

MA-CFA analysis

To compare the 5 different competitive models, we applied CFA. The obtained results are given in Table 1. The CFA showed that the model-data fit values of Model 1, Model 2 and Model 3 show sufficient model fit according to CFI and TLI values (> .90). However, in all these models, the RMSEA value is above .08. In this case, it can be said that the model-data fit of these models is not sufficient. It has been mentioned in previous sections that these models have been validated by very few studies. When the model-data fit values obtained for these first three models are examined, it is seen that the factor structure of MSPSS in this study is far from being unidimensional and two-factorial. The original 3-factor model (Model 4), proposed by Zimet et al. (1988), fitted the data excellent, as in many studies (CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.000; RMSEA = .008, 95% CI [.007, .010]; SRMR = .007). Besides, Model 5 (proposed by Merino-Soto et al., 2022) was found to have excellent model-data fit values (CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.000; RMSEA = .006, 90% CI [.004, .007]; SRMR = .003). It can be said that these two competitive models are successful in explaining the factor structure of MSPSS.

Table 1.

Fit indices of all the competitive models

| χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | 95% CI for RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 24,866.7 | 54 | .919 | .900 | .124 | [.123, .125] | .360 | 24,698.7 | 24,267.7 |

| Model 2 | 11,977.8 | 53 | .961 | .950 | .087 | [.086, .088] | .207 | 11,871.9 | 11,439.2 |

| Model 3 | 11,794.1 | 53 | .961 | .949 | .086 | [.085, .087] | .202 | 11,598.1 | 11,155.4 |

| Model 4 | 158.0 | 51 | 1.000 | 1.000 | .008 | [.007, .010] | .007 | 56.8 | −368.0 |

| Model 5 | 84.1 | 42 | 1.000 | 1.000 | .006 | [.004, .007] | .003 | 1.2 | −347.6 |

Note. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval; df = degrees of freedom; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; Model 1 = unidimensional model; Model 2 = 2-factor correlated model (FR/SO and FA); Model 3 = 2-factor correlated model (FA/SO and FR); Model 4 = 3-factor correlated model; Model 5 = bifactor CFA model; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

For Model 4 and Model 5, the model fit indices indicated good fit. Therefore, factor loadings, omega coefficient and ECV results for both models were examined and a more valid decision was tried to be made (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings (λ), omega and ECV coefficients for Model 4 and Model 5

| Items | Three-factor CFA (Model 4) | Bifactor-CFA (Model 5) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λFAM | λFRI | λSO | λG | λFAM | λFRI | λSO | |

| FAM | |||||||

| I3 | .851 | .522 | .673 | ||||

| I4 | .886 | .541 | .701 | ||||

| I8 | .789 | .489 | .626 | ||||

| I11 | .812 | .492 | .643 | ||||

| ω | .902 | .564 | |||||

| ECV | – | .208 | |||||

| FRI | |||||||

| I6 | .845 | .512 | .673 | ||||

| I7 | .862 | .506 | .701 | ||||

| I9 | .860 | .522 | .683 | ||||

| I12 | .841 | .502 | .682 | ||||

| ω | .914 | .589 | |||||

| ECV | – | .223 | |||||

| SO | |||||||

| I1 | .815 | .606 | .547 | ||||

| I2 | .853 | .641 | .572 | ||||

| I5 | .802 | .623 | .511 | ||||

| I10 | .801 | .632 | .489 | ||||

| ω | .890 | .657 | .372 | ||||

| ECV | – | .434 | .134 | ||||

Note. FAM = family; FRI = friends; SO = significant others; G = general factor; ω = hierarchical omega coefficient for general factor and hierarchical subscale omega coefficient for specific factors; ECV = explained common variance for general factor and explained common variance subscales for specific factors.

Factor loading values of Model 4 range from .789 to .886. The findings in Table 2 show that each item has a high factor loading on the relevant factor. In addition, it can be said that hierarchical omega coefficients are also quite high as an indicator of composite reliability (ω = .890 to .914, M = .902). However, statistically significant inter-factorial correlations in this model (rfam-fri = .362, rfam-so = .468 and rfri-so = .452; M = .427; p < .001) may indicate a general factor. These correlation coefficients also indicate moderate and positive relationships.

It was determined that the factor loadings of the general factor of Model 5 (λ = .489 to .641, M = .549) were lower than the factor loadings of the specific factor (λ = .489 to .701, M = .625). This finding shows that the variance explained by specific factors is higher. Omega and ECV values were also evaluated to decide which of the general or specific factors were more dominant. In our study, the omega coefficient for the general factor is below .75; also the omega coefficient for subscales is above .50. This shows that MSPSS is not essentially unidimensional. Besides, all ECV values are below .60.

Factor loading values for both models are .30 and above. In this case, model-data fit values were compared to determine the most appropriate factor structure. These findings show that the scale does not have a strong general factor. In addition, the fact that the model-data fit between Model 4 and Model 5 is very close to each other shows that the model-data fit has not improved significantly with the bifactor model. At the end of these reviews, it was decided that the original three-factor correlated CFA model was the “actual” factor structure of MSPSS. Besides all other findings show that the MSPSS has three dominant specific factors.

Measurement invariance testing

In the database we created in our study, it was determined that MSPSS was culturally adapted to 28 different languages. There may be language and translation biases in these cross-cultural studies. Therefore, besides English, 5 different languages that are used most in the research were selected and a pooled correlation matrix of each language was obtained. Then, multigroup CFA was applied for language groups over this correlation matrix. The same evaluation was applied to nonclinical and clinical samples, and the findings are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fit indices of measurement invariance models

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔTLI | ΔRMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Configural | 186.2 | 102 | 1.000 | 1.000 | .007 | |||

| Metric | 230.1 | 111 | 1.000 | .999 | .008 | .000 | .001 | .001 | |

| Language | Configural | 116.1 | 306 | 1.000 | 1.000 | .000 | |||

| Metric | 393.3 | 351 | 1.000 | 1.000 | .007 | .000 | .000 | .007 |

Note. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; ΔCFI = CFI values’ difference; ΔTLI = TLI values’ difference; ΔRMSEA = RMSEA values’ difference.

Table 3 lists the MI results of the correlated three-factor MSPSS model investigated concerning language and clinical status. The language and clinical status variables have been found to give configural and metric MI. Depending on the clinical status, configural and metric MI was also ensured.

Discussion

The objective of this study is to evaluate the latent factor structure of the MSPSS, the most popular tool in the literature for measuring perceived social support. Since the year it was created, the MSPSS has been modified for hundreds of different cultures. The associated 3-factor structure, which is the MSPSS’s original factor structure, was mostly derived in these adaptation investigations. However, in recent years, various MSPSS factor structures (including bifactor-CFA, ESEM and bifactor-ESEM) have also been investigated (Merino-Soto et al., 2022; Osman et al., 2014; Yılmaz Koğar & Koğar, 2023). The results of these studies suggest that the 3-factor structure of the scale requires new examination. The motivation for this study came from looking at the novel factor structures investigated for MSPSS utilizing the pooled correlation matrix.

By combining individual studies examining competing models for the dimensionality of MSPSS, the factor structure of MSPSS can be better understood from a more general perspective. In our research, 59 samples from 54 unique articles were used for the database. The average sample size of these 59 samples is 473. This sample size average (N < 500) can produce inaccurate factor loadings (Auerswald & Moshagen, 2019). Furthermore, depending on the sample, different subgroups (age, gender, clinical sample, etc.) may also have an impact on the factor structure. Therefore, our research aimed to use an MA-CFA to remove any potential influence that sample size and sample subgroups may have had on the factor structure of MSPSS to more correctly evaluate the factor structure of MSPSS. Factor loadings, standardized regression coefficients, inter-factorial correlation coefficients and inter-item correlation coefficients were used in 59 samples to conduct a random-effects meta-analysis for this purpose. In this manner, an item-level pooled correlation matrix was produced. Dimensionality tests performed on the pooled correlation matrix showed that the best representation of the structure was achieved through a three-factor model. However, since there are unidimensional and 2-factor MSPSS factor structure solutions in the literature, 5 different competitive models (details are in the introduction) have been tested with MA-CFA.

The MA-CFA determined that all unidimensional and 2-factor structures (Model 1–Model 3) applied to determine the MSPSS factor structure produced very insufficient model-data fit values. Model-data fits show a perfect fit for both correlated 3-factor CFA (Model 4) and bifactor-CFA (Model 5) models, which is the main focus of this research. Factor loading values for both models are .40 and above. In this case, model-data fit values were compared to determine the most appropriate factor structure. It was decided that the three-factor correlated CFA model with the better model fit was the “actual” factor structure of the MSPSS. These findings are similar to most of the MSPSS’s cultural adaptation studies (e.g., Bruwer et al., 2008; Calderón Garrido et al., 2021; Canty-Mitchell, & Zimet, 2000). Twenty-one of the cross-cultural studies examined the factor structure of MSPSS with CFA.

It can be said that the MSPSS has a nondominant general factor according to hierarchical omega, hierarchical omega for subscales and ECVs for the bifactor models. Besides, all three factors of the MSPSS are quite strong and dominant. Although the correlation values between the factors are statistically significant, this relationship is at a moderate level. All these findings show that the multidimensional structure of MSPSS still exists today.

Lastly, the internal consistency was high based on the omega values, and the metric MI of the structure of the correlated three-factor model of MSPSS was attained based on clinical status and language. Therefore, it may be concluded that the structure of the correlated three-factor model of MSPSS is strong.

Limitations, future directions and conclusion

The inability to test the ESEM and bifactor-ESEM factor structures for MSPSS is the first and most significant limitation of our research. The bifactor-ESEM model was found to be the model that best characterized the factor structure of the MSPSS in the sole cross-cultural study in which these factor structures were examined (Merino-Soto et al., 2022). This circumstance suggests that a factor structure analysis will be done by taking into account new MSPSS models in various cultural contexts. As a result, more study is required on this topic. It is useful to interpret the results of this study according to the information that all other studies, except the study by Merino-Soto et al., (2022), did not consider cross-factor loadings. Another drawback is that the publications we used to build our database offer insufficient details and do not employ enough samples for factor analysis. The majority of the publications lacked information on the method of factor extraction they employed. Several articles lack or have insufficient information on certain fundamental demographic factors, such as age and gender. Only 30.5% of the reviewed articles reached the recommended sample size to obtain more stable results in factor analysis (N > 500) (Hirschfeld et al., 2014). This raises questions about the validity of the factor analysis’s conclusions. Another disadvantage of this study is that it utilizes the findings of studies that use factor loadings instead of raw data. It was claimed that the research based on MA-CFA, which is scarce in the literature, used a small amount of raw data (i.e., Gnambs & Staufenbiel, 2016). To effectively perform studies like ours, it is crucial to share the raw data or the inter-item correlation matrix while considering the ethical constraints, especially in cross-cultural investigations. For this reason, it is recommended to include values showing the correlations between the items of the scale in studies examining the psychometric properties of the scales.

The structure of the SO factor of the scale is more controversial than the other factors. The reason for this situation was that the expression “special person” in the items in the SO subscale was not fully understood by the participants (Eker et al., 2001; Wongpakaran & Wongpakaran, 2012). For this reason, additional explanations were given for the items of this subscale and the overlap of the SO items with the other subscale items was tried to be minimized. The way the scale is administered may affect the responses of the participants. Verbally collected responses may provide different information than that collected in a written or online questionnaire, because the practitioner may provide clarifying information to the participant or question the participant to clarify their response (Soszynski & Bliss, 2022). For this reason, future studies that will use the MSPSS may proceed to the data collection phase after explaining the scale to the participants or collect the data verbally. Thus, non-substantive responses of the participants regarding the SO factor can be prevented and the three-factor structure of the scale can be clarified.

The biggest contribution of our study to the literature is that it shows that the MSPSS can better adapt to the three-factor correlated CFA factor structure through a sample of 27,905. More studies are needed on the compatibility of MSPSS with the bifactor-CFA and ESEM structures. The importance of performing statistical analyses correctly is another issue that emerged in this study. While deciding on the number of factors in EFA, a dimensionality analysis like parallel analysis is required. It has been determined that the ML estimation method is generally used in CFA studies. However, studies on estimation methods show that using WLS instead of ML provides more accurate estimations as long as there are enough samples for CFA (Li, 2016). However, as Bonifay, Lane and Reise (2017) stated, high model-data fit of bifactor models can be “overfitting.” Overfitting is defined as the tendency of bifactor models to have higher model-data fit compared to other CFA models (Bonifay et al., 2017). Making a profile of the person’s perceived social support with scores from only 3 factors of the MSPSS may lead to a suitable assessment. Considering the situations created by the SO factor, the theoretical structure of the scale can be reviewed and an improvement can be made, especially on the SO factor. Or, more studies can be carried out testing the factor structure of MSPSS with current models. However, the fact that the MSPSS has a robust factor structure in different subsample groups is proof of how strong the scale’s structure is. In this way, MSPSS is a multidimensional scale that measures perceived social support with its different factors, as well as a useful measurement tool that can create a perceived social support profile and can do this with only 12 items.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.118.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://osf.io/6efq3/?view_only=8e25985f3a15465a908dee36fe4b3f07

Data availability statement

The studies, coding and analyses used in the current research can be accessed by following this link: https://osf.io/6efq3/?view_only=8e25985f3a15465a908dee36fe4b3f07

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Author-2; also material preparation, data collection and data analysis were performed by Author-1. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Ethics statement

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

References

- Akhtar A, Rahman A, Husain M, Chaudhry IB, Duddu V and Husain N (2010) Multidimensional scale of perceived social support: Psychometric properties in a South Asian population. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 36(4), 845–851. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerswald M and Moshagen M (2019) How to determine the number of factors to retain in exploratory factor analysis: A comparison of extraction methods under realistic conditions. Psychological Methods 24(4), 468. 10.1037/met0000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M (2000) Social support research in community psychology. In Rappaport J and Seidman E (eds), Handbook of Community Psychology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, pp. 215–245. 10.1007/978-1-4615-4193-6_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Başol G (2008) Validity and reliability of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support-revised, with a Turkish sample. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 36(10), 1303–1313. 10.2224/sbp.2008.36.10.1303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifay W, Lane SP and Reise SP (2017) Three concerns with applying a bifactor model as a structure of psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science 5(1), 184–186. 10.1177/2167702616657069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer B, Emsley R, Kidd M, Lochner C and Seedat S (2008) Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in youth. Comprehensive Psychiatry 49(2), 195–201. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón Garrido C, Ferrando Piera PJ, Lorenzo Seva U, Gómez Sánchez D, Fernández Montes A, Palacín Lois M, … Jiménez Fonseca P (2021) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) in cancer patients: Psychometric properties and measurement invariance. Psicothema 33(1), 131–138. 10.7334/psicothema2020.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canty-Mitchell J and Zimet GD (2000) Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology 28(3), 391–400. 10.1023/A:1005109522457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright AV, Pione RD, Stoner CR and Spector A (2022) Validation of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS) for family caregivers of people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health 26(2), 286–293. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1857699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ST and Chan AC (2004) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: Dimensionality and age and gender differences in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences 37(7), 1359–1369. 10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW and Rensvold RB (2002) Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling 9(2), 233–255. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung MW-L (2022) metaSEM (Version 1.2.5.1) [Computer software]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/metaSEM/

- Chou KL (2000) Assessing Chinese adolescents’ social support: The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Personality and Individual Differences 28(2), 299–307. 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00098-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb CL and Xie D (2015) Structure of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support for undocumented Hispanic immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 37(2), 274–281. 10.1177/0739986315577894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dambi JM, Corten L, Chiwaridzo M, Jack H, Mlambo T and Jelsma J (2018) A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the cross-cultural translations and adaptations of the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 16(1), 1–19. 10.1186/s12955-018-0912-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueber DM (2017) Bifactor Indices Calculator: A Microsoft Excel-Based Tool to Calculate Various Indices Relevant to Bifactor CFA Models. 10.13023/edp.tool.01 Available at http://sites.education.uky.edu/apslab/resources/. [DOI]

- Duru E (2007) Re-examination of the psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support among Turkish university students. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 35(4), 443–452. 10.2224/sbp.2007.35.4.443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle DE, Hybels CF and Proeschold-Bell RJ (2019) Perceived social support, received social support, and depression among clergy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 36(7), 2055–2073. 10.1177/0265407518776134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim MT and Alothman AA (2022) The reliability and validity of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS) in mothers of children with developmental disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 92, 101926. 10.1016/j.rasd.2022.101926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM (2004) Measuring perceived social support in Mexican American youth: Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 26(2), 187–194. 10.1177/0739986304264374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eker D, Arkar H and Yaldız H (2001) Çok Boyutlu Algılanan Sosyal Destek Ölçeğinin gözden geçirilmiş formunun faktör yapısı, geçerlik ve güvenirliği [Factorial structure, validity, and reliability of revised form of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support]. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi 12(1), 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ermis-Demirtas H, Watson JC, Karaman MA, Freeman P, Kumaran A, Haktanir A and Streeter AM (2018) Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support within Hispanic college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 40(4), 472–485. 10.1177/0739986318790733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field AP (2005) Is the meta-analysis of correlation coefficients accurate when population correlations vary? Psychological Methods 10, 444–467. 10.1037/1082-989X.10.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin CJ and Happell B (2014) On exploratory factor analysis: A review of recent evidence, an assessment of current practice, and recommendations for future use. International Journal of Nursing Studies 51(3), 511–521. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnambs T and Staufenbiel T (2016) Parameter accuracy in meta-analyses of factor structures. Research Synthesis Methods 7(2), 168–186. 10.1002/jrsm.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber MG, Cohen JL, Lucas T and Baltes BB (2007) The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology 39, 133–144. 10.1007/s10464-007-9100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld G, von Brachel R and Thielsch M (2014) Selecting items for big five questionnaires: At what sample size do factor loadings stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality 53, 54–63. 10.1016/j.jrp.2014.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 30(2), 179–185. 10.1007/BF02289447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JE and Schmidt FL (2004) Methods of Meta-analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 10.4135/9781412985031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga K, Wu JR, Armstrong AJ, Kaya C, Dutta A, Kundu M and Chan F (2021) Assessing perceived social support among African American College students with disabilities: A confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 34(2), 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, Orehek E, Hain KL and Vanvleet M (2010) Enacted support’s links to negative affect isolated from trait influences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36, 132–142. 10.1177/0146167209349375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B and Scoboria A (2005) The relative contribution of trait and social influences to the links among perceived social support, affect, and self‐esteem. Journal of Personality 73(2), 361–388. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laksmita OD, Chung MH, Liao YM and Chang PC (2020) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in Indonesian adolescent disaster survivors: A psychometric evaluation. PLoS One 15(3), e0229958. 10.1371/journal.pone.0229958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CH (2016) Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods 48(3), 936–949. 10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki CK and Demaray MK (2002) Measuring perceived social support: Development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASS). Psychology in the Schools 39(1): 1e18. 10.1002/pits.10004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki CK and Elliott SN (1999) Adolescents’ ratings of perceived social support and its importance: Validation of the Student Social Support Scale. Psychology in the Schools 36, 473–483. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins MV, Peterson BD, Almeida V and Costa ME (2012) Measuring perceived social support in Portuguese adults trying to conceive: Adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Peritia 13, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Merino-Soto C, Boluarte Carbajal A, Toledano-Toledano F, Nabors LA and Núñez-Benítez MÁ (2022) A new story on the multidimensionality of the MSPSS: Validity of the internal structure through bifactor ESEM. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(2), 935. 10.3390/ijerph19020935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad AH, Al Sadat N, Loh SY and Chinna K (2015) Validity and reliability of the Hausa version of multidimensional scale of perceived social support index. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal 17(2), e18776. 10.5812/ircmj.18776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira JM, de Fátima Silva M, Moleiro C, Aguiar P, Andrez M, Bernardes S and Afonso H (2003) Perceived social support as an offshoot of attachment style. Personality and Individual Differences 34(3), 485–501. 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00085-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (2017) Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH and Kaniasty K (1996) Received and perceived social support in times of stress: A test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71(3), 498. 10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Lamis DA, Freedenthal S, Gutierrez PM and McNaughton-Cassill M (2014) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: Analyses of internal reliability, measurement invariance, and correlates across gender. Journal of Personality Assessment 96(1), 103–112. 10.1080/00223891.2013.838170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, … McKenzie JE (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews, BMJ 372. 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SS, Spinder H, Erdman RA and Denollet J (2009) Poor perceived social support in implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) patients and their partners: Cross-validation of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Psychosomatics 50(5), 461–467. 10.1016/S0033-3182(09)70838-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Villalobos C, Briede-Westermeyer JC, Schilling-Norman MJ and Contreras-Espinoza S (2021) Multidimensional scale of perceived social support: Evidence of validity and reliability in a Chilean adaptation for older adults. BMC Geriatrics 21(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s12877-021-02404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati G and Pietrantoni L (2010) The relation of perceived and received social support to mental health among first responders: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Community Psychology 38(3), 403–417. 10.1002/jcop.20371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME and Heller K (1983) Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology 11(1), 1–24. 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Bonifay WE and Haviland MG (2013) Scoring and modeling psychological measures in the presence of multidimensionality. Journal of Personality Assessment 95(2), 129–140. 10.1080/00223891.2012.725437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Scheines R, Widaman KF and Haviland MG (2013) Multidimensionality and structural coefficient bias in structural equation modeling: A bifactor perspective. Educational and Psychological Measurement 73(1), 5–26. 10.1177/0013164412449831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W (2022) psych (Version 2.2.9) [Computer software]. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/

- Robu V, Sandovici A and Ciudin M (2020) Measuring perceived social support in Romanian adolescents: Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Innovation in Psychology, Education and Didactics 24(1), 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H and Müller H (2003) Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research 8(2), 23–74. 10.23668/psycharchives.12784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeders U, Kubera F and Gnambs T (2022) The structure of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20): A meta-analytic confirmatory factor analysis. Assessment 29(8), 1806–1823. 10.1177/10731911211033894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif M, Zaidi A, Waqas A, Malik A, Hagaman A, Maselko J, … Rahman A (2021) Psychometric validation of the Multidimensional scale of perceived social support during pregnancy in rural Pakistan. Frontiers in Psychology 12, 601563. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.601563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soszynski M and Bliss R (2022) Does survey administration mode relate to non-substantive responses? A comparison of email versus phone administration of a residential utility-sponsored energy efficiency program survey. Survey Practice 15(1). 10.29115/SP-2022-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley MA, Beck JG and Zebb BJ (1998) Psychometric properties of the MSPSS in older adults. Aging & Mental Health 2(3), 186–193. 10.1080/13607869856669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strunk KK and Lane FC (2017) The Beck Depression Inventory, (BDI-II): A cross-sample structural analysis. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 50(1–2), 3–17. 10.1080/07481756.2017.1318636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonsing K (2022) Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support among resettled Burmese in the United States. The British Journal of Social Work 52(7), 4077–4088. 10.1093/bjsw/bcac036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonsing K, Zimet GD and Tse S (2012) Assessing social support among South Asians: The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 5(2), 164–168. 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trejos-Herrera AM, Bahamón MJ, Alarcón-Vásquez Y, Vélez JI and Vinaccia S (2018) Validity and reliability of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in colombian adolescents. Psychosocial Intervention 27(1), 56–63. 10.5093/pi2018a1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN (2009) Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science 4, 236–255. 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangelisti AL (2009) Challenges in conceptualizing social support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 26(1), 39–51. 10.1177/0265407509105520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ (2018, June) Social well-being and health in the older population: Moving beyond social relationships. In Majmundar, MK, Hayward, MD, Future Directions for the Demography of Aging: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, pp. 99–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wan Q, Huang Z, Huang L and Kong F (2017) Psychometric properties of multi-dimensional scale of perceived social support in Chinese parents of children with cerebral palsy. Frontiers in Psychology 8. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Yendork JS and Somhlaba NZ (2017) Psychometric properties of multidimensional scale of perceived social support among Ghanaian adolescents. Child Indicators Research 10(1), 101–115. 10.1007/s12187-016-9367-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wongpakaran T, Wongpakaran N and Ruktrakul R (2011) Reliability and validity of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS): Thai version. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health 7, 161. 10.2174/1745017901107010161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongpakaran, N., & Wongpakaran, T., (2012). A revised Thai multi-dimensional scale of perceived social support. The Spanish journal of psychology, 15(3), 1503–1509. 10.5209/rev_sjop.2012.v15.n3.39434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz Koğar, E., & Koğar, H., (2023). A Bifactor-ESEM Representation of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Psychological Reports, 00332941231206992. 10.1177/00332941231206992. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhou K, Li H, Wei X, Yin J, Liang P, Zhang H, … Zhuang G (2015) Reliability and validity of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Chinese mainland patients with methadone maintenance treatment. Comprehensive Psychiatry 60, 182–188. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG and Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment 52(1), 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]