Abstract

Objective

Knowledge of intensive care unit (ICU) acquired hypernatremia (ICU-AH) has been hampered by the absence of granular data and confounded by variable definitions and inclusion criteria.

Design

Multicentre retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Twelve ICUs in Queensland (QLD), Australia.

Participants

Adult patients admitted to ICU from 2015 to 2021. Only the first ICU admission was considered, and we categorised patients into mild (146–150 mmol·L−1), moderate (151–155 mmol·L−1) and severe (>155 mmol·L−1) ICU-acquired hypernatremia.

Main outcome measure

We aimed to study the prevalence of ICU-AH, patient characteristics, trajectory, risk factors, and outcomes.

Results

Data from 55,255 ICU admissions were included in the analysis, of which 4146 (7.5 %) patients had ICU-AH. These were subcategorised into mild (n = 2,670, 4.8 %), moderate (n = 1,073, 1.9 %) and severe (n = 403, 0.73 %) forms. Median time to diagnosis was 4 (2–6) d after ICU admission, while median time to peak serum sodium level was 5 (3–8) d. The median maximum sodium level across the cohort was 149 (147–152) mmol·L−1. The sodium correction rate was 1 mmol·L−1 per day, taking a median of 3 d (1–5) for sodium levels to return below 145 mmol·L−1. APACHE III score, invasive ventilation, fever, and diuretic use on the day before hypernatremia were independent risk factors for moderate or severe ICU-AH. After adjusting for confounders, all levels of hypernatremia were independently associated with an increased risk of 30-d in-hospital mortality.

Conclusions

In a large multicentric study of critically ill patients, ICU-acquired hypernatremia occurred in one in eight admissions after a median of four days in the ICU and was preceded by identifiable and modifiable risk factors. If severe, its correction was slow, and normalisation was delayed. After adjusting for other factors, all levels of hypernatremia were an independent risk factor for 30-d in-hospital mortality.

Keywords: Critical illness, Electrolyte disturbance, Hypernatremia, Intensive care unit, Diuretics

1. Introduction

Hypernatremia, defined as sodium levels above 145 mmol·L−1, is a relatively common electrolyte disturbance in clinical settings.1 Its prevalence in hospital patients has been reported at around 0–2 %, but in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients, its prevalence appears to range from 6 to 47 %.[1], [2], [3], [4], [5] In this regard, in 2016, a large Dutch study reported a gradual shift in dysnatremia in ICUs, where over two decades, the prevalence of hyponatremia was halved while that of hypernatremia almost doubled from 13 % to 24 %.6

Hypernatremia may be related to net sodium gain from increased intake and/or reduced losses. However, it is most commonly due to net electrolyte-free water deficit due to reduced water intake and/or increased losses1,2 or both. This is particularly problematic in critically ill patients who are often unable to manage their fluid intake because of mechanical ventilation or altered consciousness, thus increasing the risk of ICU-acquired hypernatremia (ICU-AH).7

Hypernatremia is dangerous. It has been associated with a wide range of complications, including disturbed glucose utilisation, impaired gluconeogenesis, rhabdomyolysis, neurological deterioration, cardiomyopathy, and increased hospital and ICU length of stay.1 Some studies have reported an independent association with increased mortality of up to 30–48 %.1,2 However, while there are several studies of hypernatremia in ICU, many did not consider its varying degrees of severity or account for confounding variables.[7], [8], [9], [10] Furthermore, there was significant variation in the cutoff sodium levels and the day of ICU admission used by different research groups to diagnose hypernatremia.7 As a result, some of the conclusions drawn from these studies may not be truly representative of the whole ICU population in a given healthcare jurisdiction, thereby limiting their external validity.

Accordingly, we used a statewide ICU database in Queensland, Australia, to determine the prevalence, patient characteristics, trajectory, risk factors and outcomes for ICU-AH in an Australian ICU setting.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted a large multicentre statewide (Queensland, Australia) retrospective cohort study of patients with ICU-acquired hypernatremia.

2.2. Study population

We included patients from twelve ICUs across Queensland, Australia. All adult ICU patients admitted between the 1st of January 2015 and the 31st of December 2021 were included in the study, and only the first ICU admission was considered. Patients with no sodium measurements or with preexisting hypernatraemia (sodium levels >145 mmol·L−1) on the first day of ICU admission were excluded.

To avoid confounding variables, we also excluded patients transferred from other ICUs, under palliative care, or with a neurological, trauma, fulminant liver failure or post-cardiac arrest diagnosis, where hypernatremia might represent a therapeutic intervention aimed at decreasing cerebral oedema.

2.3. Data sources

We accessed routinely collected data from the statewide eCritical MetaVisionTM (iMDsoft, Boston, MA, USA) clinical information system, including patients’ demographics, admission diagnosis, laboratory data, medications, clinical observations and fluid balance.[11], [12], [13], [14], [15] The Australia and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) Centre for Outcome and Resource Evaluation (CORE) Adult Patient Database (APD) was used to extract data on the severity of illness and outcome prediction.14,16,17 The dosage of various vasopressor agents was standardised using the noradrenaline equivalent score (Supplemental Table S1).18

2.4. Definitions

ICU-acquired hypernatremia (ICU-AH) was defined as a sodium level above 145 mmol·L−1, which was not present on admission and, therefore, was acquired after ICU admission. ICU-AH was further subcategorised into mild (146–150 mmol·L−1), moderate (151–155 mmol·L−1) and severe (>155 mmol·L−1). Fever on the day before its occurrence was defined as the presence of a recorded body temperature ≥38 °C.

2.5. Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the prevalence of ICU-acquired hypernatremia and its subgroups: mild, moderate, and severe.

Secondary outcomes were patient characteristics, timing, and risk factors.

Exploratory outcomes were the trajectory of serum sodium correction and the association of hypernatremia with hospital mortality.

The primary outcome was computed from the total number of patients, including those with the highest serum sodium level in the hyponatremic range (<135 mmol·L−1). Secondary analyses were performed excluding such patients. Similarly, patients with hypernatremia on their first sodium measurement on ICU admission were excluded.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics are reported as absolute values with percentages for categorical variables or median with the interquartile interval for quantitative variables. A linear mixed model was used to study the daily maximum serum sodium evolution across time. The model included a fixed effect for time, capturing the general trend in sodium concentration over time. Additionally, random effects were incorporated to allow for individual deviations from the overall pattern. Specifically, random intercepts and slopes for a time were modelled at the subject level, allowing each individual to have a unique baseline sodium concentration and rate of change over time. Furthermore, an additional random intercept was included for time, accounting for variability across the time points that were not explained by individual differences. Logistic regression models were fitted to assess moderate or severe ICU-acquired hypernatremia risk factors and hospital mortality. The first model was performed in the population of patients who experienced ICU-acquired hypernatremia, while the latest was applied to the overall cohort. Multivariable models were built using a full pre-specification method.19,20 Correlation and interaction were carefully checked within the final models. Results are given as odds ratios with 95 % confidence intervals (OR, 95 % CI). Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.4.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the packages 'dplyr’, 'ggplot2′, 'ggpubr’, 'gtsummary’, 'survey’, ‘nlme’ and 'mice’.

2.7. Missing data management

To handle missing data of baseline characteristics within our dataset, we used multiple imputations to create ten plausible substitute datasets and combined their estimates in a way that maintained statistical power and reduced bias. The amount of missing data for key variables is shown in Supplementary Table S2.

2.8. Statement of ethics

The study was approved, and a consent waiver was granted by the Metro South Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) under the reference number HREC/2022/QMS/82024.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

From the 1st of January 2015 to the 31st of December 2021, we collected data from 74,851 index ICU admissions from 12 ICUs. After removing those who met the exclusion criteria, we studied 55,255 patients (Supplemental Fig. S1). Their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 62 yrs, and 20,749 (38 %) were female. Most patients had a surgical admission (n = 33,513, 61 %), and sepsis was the leading condition among medical admissions (n = 10,857; 56 %). The median Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation III score (APACHE) was 51. On the day of ICU admission, 29,642 (54 %) patients were invasively ventilated, 23,974 (43 %) were on vasopressor support, and 1406 (2.5 %) were on renal replacement therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Overall N = 55,255a | Normal N = 46,412a | ICU-Acquired Hypernatremia |

Hyponatremia N = 4,697a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild N = 2,670a | Mod N = 1,073a | Severe N = 403a | ||||

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age – year | 62 (49–72) | 62 (49–72) | 61 (47–72) | 62 (49–70) | 60 (49–70) | 64 (51–73) |

| Sex female | 20,749 (38) | 17,266 (37) | 1,058 (40) | 411 (38) | 161 (40) | 1853 (39) |

| Body mass index – kg.m-2 | 28 (24–33) | 28 (24–33) | 28 (24–33) | 28 (24–34) | 28 (25–34) | 27 (23–32) |

| Body surface area – m2 | 1.95 (1.78–2.12) | 1.95 (1.78–2.12) | 1.94 (1.77–2.12) | 1.96 (1.78–2.13) | 1.96 (1.75–2.16) | 1.89 (1.72–2.07) |

| Admission | ||||||

| Hospital length of stay pre-ICU admission – hours | 14 (6–46) | 14 (6–45) | 8 (3–32) | 8 (3–30) | 8 (3–36) | 15 (6–72) |

| Admission source | ||||||

| Emergency department | 13,065 (24) | 10,193 (22) | 1004 (38) | 409 (38) | 151 (37) | 1308 (28) |

| Operating Theatre | 33,375 (60) | 29,672 (64) | 954 (36) | 344 (32) | 119 (30) | 2,286 (49) |

| Other hospital | 2147 (3.9) | 1658 (3.6) | 217 (8.1) | 99 (9.2) | 42 (10) | 131 (2.8) |

| Unknown | 10 (<0.1) | 8 (<0.1) | 1 (<0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (<0.1) |

| Ward | 6,658 (12) | 4881 (11) | 494 (19) | 221 (21) | 91 (23) | 971 (21) |

| Hospital type | ||||||

| Metropolitan | 5403 (9.8) | 4,249 (9.2) | 457 (17) | 161 (15) | 72 (18) | 464 (9.9) |

| Rural/Regional | 6,462 (12) | 4,907 (11) | 279 (10) | 105 (9.8) | 36 (8.9) | 1135 (24) |

| Tertiary | 43,390 (79) | 37,256 (80) | 1,934 (72) | 807 (75) | 295 (73) | 3,098 (66) |

| Medical/Surgical admission | ||||||

| Medical | 21,742 (39) | 16,624 (36) | 1,709 (64) | 725 (68) | 283 (70) | 2,401 (51) |

| Surgical | 33,513 (61) | 29,788 (64) | 961 (36) | 348 (32) | 120 (30) | 2,296 (49) |

| Elective surgery | 24,570/33,513 (73) | 22,568/29,788 (76) | 371/961 (39) | 111/348 (32) | 44/120 (37) | 1,476/2296 (64) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 2,247 (4.1) | 1,788 (3.9) | 191 (7.2) | 48 (4.5) | 24 (6.0) | 196 (4.2) |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 1,997 (3.6) | 1,657 (3.6) | 91 (3.4) | 34 (3.2) | 11 (2.7) | 204 (4.3) |

| End stage kidney disease | 1,211 (2.2) | 945 (2.0) | 13 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) | 245 (5.2) |

| AIDS/HIV | 28 (<0.1) | 23 (<0.1) | 2 (<0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (<0.1) |

| Cancer with metastasis | 1,767 (3.2) | 1501 (3.2) | 49 (1.8) | 20 (1.9) | 4 (1.0) | 193 (4.1) |

| Chronic liver disease | 1,232 (2.2) | 821 (1.8) | 108 (4.0) | 68 (6.3) | 38 (9.4) | 197 (4.2) |

| Immunosuppression | 4,658 (8.4) | 3,751 (8.1) | 276 (10) | 96 (8.9) | 41 (10) | 494 (11) |

| Haemopathy | 1,054 (1.9) | 820 (1.8) | 74 (2.8) | 34 (3.2) | 15 (3.7) | 111 (2.4) |

| Prognostic scores | ||||||

| APACHE III risk of death | 0.05 (0.02–0.13) | 0.04 (0.01–0.11) | 0.15 (0.05–0.34) | 0.22 (0.09–0.43) | 0.24 (0.10–0.48) | 0.07 (0.03–0.19) |

| APACHE III Score | 51 (39–65) | 50 (38–63) | 66 (51–83) | 74 (57–89) | 74 (60–90) | 54 (41–68) |

| Total SOFA score | 4.0 (2.0–7.0) | 4.0 (2.0–7.0) | 7.0 (5.0–10.0) | 8.0 (5.0–10.0) | 9.0 (5.0–11.0) | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) |

| Day of ICU admission | ||||||

| Max serum creatinine at day one, μmol.L−1 | 80 (63–110) | 79 (63–105) | 92 (68–139) | 98 (72–150) | 112 (75–170) | 84 (63–129) |

| Max white count cells at day one, x109.L−1 | 12 (9–17) | 12 (9–17) | 13 (9–18) | 14 (9–19) | 14 (10–19) | 13 (9–18) |

| Max serum lactate at day 1 mmol·L-1 | 1.80 (1.20–2.80) | 1.80 (1.20–2.70) | 2.60 (1.50–4.60) | 2.80 (1.70–5.10) | 3.10 (1.90–5.50) | 1.70 (1.20–2.70) |

| Minimum pH at day one | 7.32 (7.26–7.36) | 7.32 (7.27–7.36) | 7.27 (7.18–7.34) | 7.24 (7.16–7.32) | 7.24 (7.14–7.33) | 7.34 (7.28–7.39) |

| Max bilirubin at day one, μmol.L−1 | 15 (11–21) | 15 (11–20) | 16 (11–26) | 18 (12–29) | 19 (12–30) | 16 (11–24) |

| Max noradrenaline equivalent dose at day one | 0.04 (0.01–0.11) | 0.04 (0.01–0.10) | 0.09 (0.03–0.19) | 0.13 (0.04–0.25) | 0.12 (0.05–0.27) | 0.05 (0.01–0.12) |

| Invasive ventilation at day one | 29,642 (54) | 25,224 (54) | 1,988 (74) | 851 (79) | 308 (76) | 1,271 (27) |

| Renal replacement therapy at day 1 | 1,406 (2.5) | 1079 (2.3) | 93 (3.5) | 39 (3.6) | 24 (6.0) | 171 (3.6) |

AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome; APACHE-III: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-III; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; kg.m-:2 kilogram per meter;2 m2 = meter,2 SD: standard deviation; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; μmol.L−1: micromoles per litre; L: litre; mmol.L−1: millimoles per litre.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (Q1-Q3). Categorical variables are presented as n/N (%).

3.2. Prevalence of hypernatremia

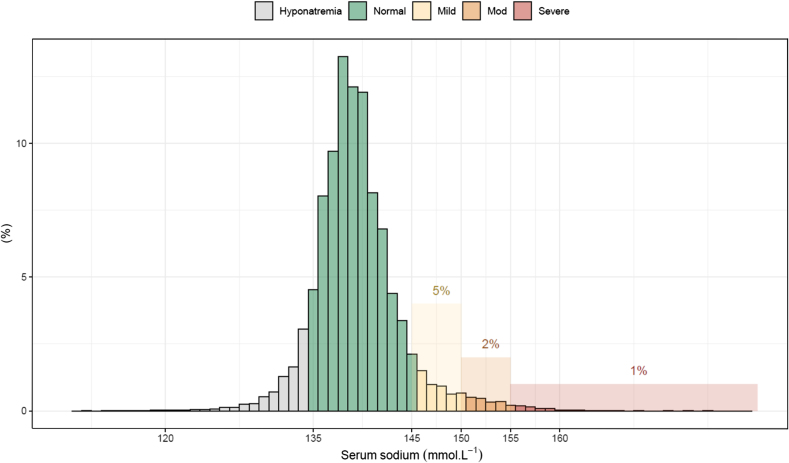

Overall, 4146 (7.5 %) patients experienced at least one episode of ICU-acquired hypernatremia. Of these, 2670 (4.8 %) patients were mild, 1073 (1.9 %) patients were moderate, and 403 (0.73 %) patients were severe ICU-AH (Fig. 1). An analysis that included patients who had only one ICU admission (Supplemental Fig. S4) and another that included all ICU admissions (Supplemental Fig. S5) displayed similar results.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution plot of maximum serum sodium levels in ICU.

The median maximum sodium level across the cohort was 149 (147–152) mmol·L−1. The prevalence of hypernatremia was stable from 2015 to 2019 but increased from 6.8 % to 9.4 % from 2020 to 2021 (p < 0.001 for change in slope) (Supplemental Fig. S2). This increase was mainly driven by an increase in the mild hypernatremia category.

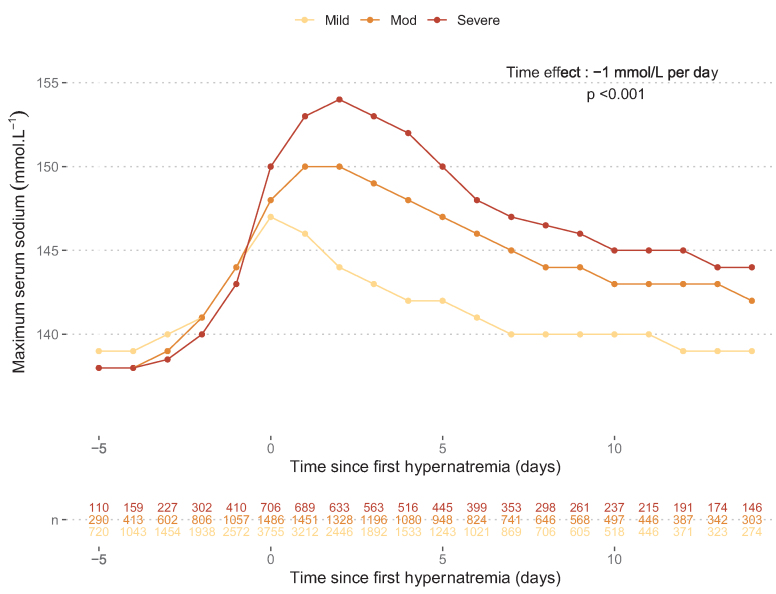

3.3. Trajectory of hypernatremia

ICU-acquired hypernatremia was first diagnosed at a median of day 4 (2–6) after ICU admission, while the peak serum sodium was reached on day 5 (3–8). The course of hypernatremia correction is displayed in Fig. 2. After the first day of hypernatremia, the correction rate was −1 mmol·L−1 per day according to the linear mixed model, and the median duration of hypernatremia was 3 d (1–5). Patients with severe and moderate ICU-acquired hypernatremia experienced a longer median duration of hypernatremia of 7 d (4–10) and 5 d (3–8), respectively, compared to 2 d (1–3) for those with mild hypernatremia. The distribution of residuals with the QQ-plot is provided in the supplemental material (Supplemental Fig. S6).

Fig. 2.

Daily maximum serum sodium evolution across time according to severity groups.

Points represent the median daily maximum serum sodium level for each ICU-acquired hypernatremia subgroup. The time effect was estimated with a linear mixed model. The model was fitted with time as a fixed effect and a random intercept and slope for each subject to account for multiple measurements per subject. The model included the following specifications: . Where and are the fixed effect, and are random intercept and slope for the subject , respectively and the residual error. is a categorical variable representing the different subgroups of ICU-Acquired hypernatremia and its interaction with the random slope allow for varying effect of time on daily maximum sodium levels across the different groups.

Daily maximum serum sodium levels were associated with the daily maximum chloride level with a steeper slope among those with severe hypernatremia (Supplemental Fig. S3).

3.4. Risk factors for moderate or severe ICU-acquired hypernatremia

For 4135 (99.7 %) patients, information about the day before the first hypernatremia day was available. Before the first onset of hypernatremia, 81 % of patients were invasively ventilated, 35 % had at least one fever episode, 41 % were exposed to diuretics, and the median volume of crystalloid administered was 1262 ml (692-1952).

As shown in Table 2, on multivariable analysis, chronic liver disease (OR = 1.57, 95 % CI [1.18 to 2.09]), diuretic use (OR = 1.26, 95 % CI [1.08 to 1.48]), the amount of crystalloid fluid given (OR = 1.03 per 500 ml, 95 % CI [1.00 to 1.07]), sepsis (OR = 1.35, 95 % CI [1.16 to 1.57]), invasive ventilation (OR = 1.83, 95 % CI [1.52 to 2.20]) and fever on the previous day (OR = 1.57, 95 % [1.37 to 1.81]) were independently associated with increased risk of moderate or severe hypernatremia. The unadjusted logistic regression model is shown in the Supplemental Table S3.

Table 2.

Factors associated with moderate or severe ICU-acquired hypernatremia on unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression.

| Variable | N | Unadjusted |

Multivariable |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | p-value | OR | 95 % CI | p-value | ||

| Chronic liver disease | 4,135 | 1.83 | 1.39 to 2.42 | <0.001 | 1.57 | 1.18 to 2.09 | 0.002 |

| Diabetes | 4,135 | 1.01 | 0.74 to 1.38 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.72 to 1.38 | >0.99 |

| Sepsis | 4,135 | 1.62 | 1.41 to 1.85 | <0.001 | 1.35 | 1.16 to 1.57 | <0.001 |

| Fever the day before the first hypernatremia day | 4,135 | 1.71 | 1.50 to 1.95 | <0.001 | 1.57 | 1.37 to 1.81 | <0.001 |

| Diuretics use the day before the first hypernatremia day | 4,135 | 1.44 | 1.27 to 1.64 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 1.08 to 1.48 | 0.004 |

| Urine output the day before the first hypernatremia day - per 500 ml | 4,135 | 1.05 | 1.03 to 1.08 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 0.99 to 1.04 | 0.37 |

| APACHE Score III | 4,135 | 1.01 | 1.01 to 1.01 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1.01 to 1.01 | <0.001 |

| Crystalloid fluid - per 500 ml | 4,135 | 1.06 | 1.03 to 1.09 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 1.00 to 1.07 | 0.044 |

| Type of admission | 4,135 | ||||||

| Medical | – | – | – | – | |||

| Surgical | 0.82 | 0.72 to 0.94 | 0.005 | 0.92 | 0.79 to 1.06 | 0.26 | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation on the day before the first hypernatremia day | 4,135 | 2.00 | 1.67 to 2.39 | <0.001 | 1.83 | 1.52 to 2.20 | <0.001 |

APACHE-III: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-III; CI: Confidence Interval; ml: milliliter; OR: Odds Ratio.

Only patients who experienced ICU-acquired hypernatremia were included in the model. 11 patients with ICU-Acquired hypernatremia were excluded from this analysis due to the absence of complete information of the day before hypernatremia onset. All 4135 remaining observations have been included. No imputation was performed on these 11 patients as information for the day before the first hypernatremia day was considered not missing at random. The total number of events (moderate or severe ICU-acquired hypernatremia) was 1470.

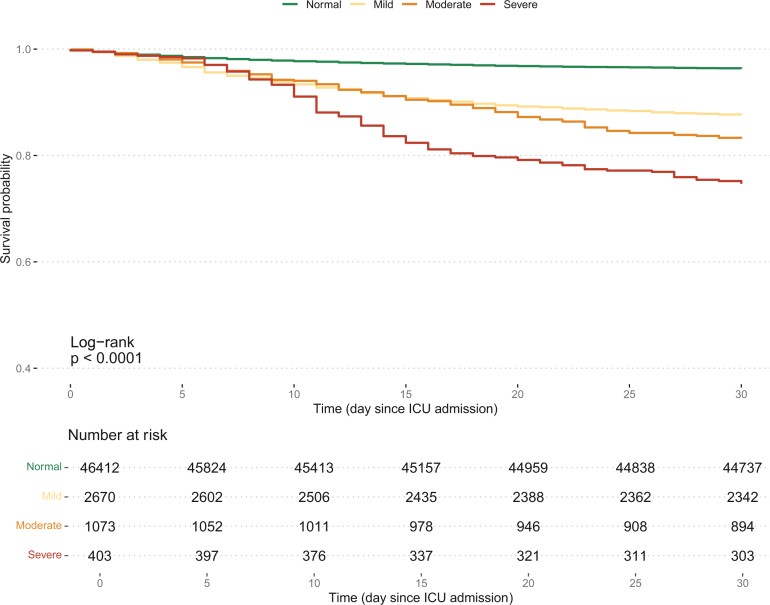

3.5. Association of ICU-acquired hypernatremia with 30-day hospital mortality

Kaplan Meier survival plots displayed a gradual increase in 30-d hospital mortality (Fig. 3) according to the severity of hypernatremia. After adjustment for multiple confounders by the Logistic regression model, mild, moderate, and severe ICU-acquired hypernatremia were all independently associated with a progressively increasing risk of 30-day hospital mortality (OR = 1.61, 95 % CI [1.40 to 1.86], OR = 2.44, 95 % CI [2.04 to 2.92], and OR = 3.61, 95 % CI [2.78 to 4.7], respectively) (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan Meier survival curve for 30-day hospital mortality according to ICU-acquired hypernatremia severity.

Table 3.

Factors related to hospital mortality by unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted |

Multivariable |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | p-value | OR | 95 % CI | p-value | |

| Age - per 10 years | 1.42 | 1.38, 1.46 | <0.001 | 1.30 | 1.26, 1.34 | <0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 2.97 | 2.60, 3.40 | <0.001 | 2.26 | 1.93, 2.65 | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 4.84 | 4.14, 5.67 | <0.001 | 2.35 | 1.94, 2.85 | <0.001 |

| Immunosuppression | 2.83 | 2.56, 3.14 | <0.001 | 1.15 | 0.99, 1.33 | 0.060 |

| Hematological cancer | 4.96 | 4.22, 5.85 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 1.08, 1.67 | 0.009 |

| ICU-AH sodium category | ||||||

| Normal | – | – | – | – | ||

| Mild | 3.70 | 3.29, 4.17 | <0.001 | 1.61 | 1.40, 1.86 | <0.001 |

| Mod | 6.36 | 5.46, 7.40 | <0.001 | 2.44 | 2.04, 2.92 | <0.001 |

| Severe | 9.64 | 7.74, 12.0 | <0.001 | 3.61 | 2.78, 4.70 | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 6.01 | 5.52, 6.55 | <0.001 | 1.71 | 1.53, 1.90 | <0.001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 1.67 | 1.39, 2.01 | <0.001 | 1.49 | 1.19, 1.87 | <0.001 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation on the day of ICU admission | 1.19 | 1.10, 1.29 | <0.001 | 1.10 | 1.00, 1.22 | 0.062 |

| APACHE Score III | 1.06 | 1.06, 1.06 | <0.001 | 1.05 | 1.04, 1.05 | <0.001 |

| Chronic cardiovascular disease | 1.75 | 1.48, 2.08 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 0.97, 1.44 | 0.10 |

| Type of admission | ||||||

| Medical | – | – | ||||

| Surgical | 0.59 | 0.53, 0.66 | <0.001 | |||

APACHE-III: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-III; CI: Confidence Interval; OR: Odds Ratio, mmol.L−1: millimoles per litre.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key findings

We analysed granular data from over 50,000 unique patient admissions to the ICU and found several key findings. First, ICU-acquired hypernatremia occurs in >7 % of ICU patients. Second, we found that the peak level of hypernatremia occurred on day five. Third, we found that the correction of hypernatremia was slow at only 1 mmol·L−1 per day. Fourth, we found that the duration of hypernatremia was greater in moderate and severe cases, taking over 5 d to be corrected to normal levels. Fifth, we identified multiple risk factors associated with the development of ICU-acquired hypernatremia, including modifiable ones. Finally, after adjustment for confounders, we found that all levels of hypernatremia were associated with an increased risk of hospital mortality.

4.2. Relationship to literature

The prevalence of ICU-acquired hypernatremia varied in the literature, dependent on the timing and definitions used and was based on a limited number of large studies. A large retrospective Dutch study reviewing data from 80,571 patients collected over 21 yrs (1992–2012) from two ICUs reported that the prevalence of hypernatremia increased over a 21-y study period from 13 % to 24 %, with severe hypernatremia increasing from 0.7 to 6.3 %.6 Such findings suggest a much higher prevalence than that observed in our cohort and demonstrate the pervasiveness of this condition. However, the Dutch investigators did not exclude patients who had hypernatraemia before the ICU admission nor those with intentional therapeutic high sodium targets, such as head trauma patients. They, however, reported that overall mortality increased over the 21-y study period from 13 % to 16 % and that extremes of high and low sodium levels were significantly associated with mortality following a U-shaped relationship.6 They did not report on the use of fluids or diuretics, did not account for or adjust for risk factors, and did not report the rate of sodium correction. Thus, our study is the first to identify modifiable risk factors for hypernatremia, its slow correction and its adjusted association with mortality.

A study by Waite et al. reviewed data from 207,702 patients from 344 ICUs in the US over a 2-y period and reported a hypernatremia prevalence of 4.3 %.7 However, this study did not report data on fluids or diuretics use and limited inclusion criteria to patients with sodium >149 mmol·L−1 and only after 48 h of ICU admission. Our study showed that mild ICU-acquired hypernatremia (sodium 146–150 mmol·L−1) patients represented >60 % of all cases, implying that many patients would have been missed in such a study. However, our findings that patients developed hypernatremia after a median of 4 days and peaked on day 5 aligned with the study by Waite et al., who reported sodium levels >149 mmol·L-1 after a median of 5 days post-ICU admission7 and, once again, demonstrating the pervasive occurrence of this condition. This study also reported that, after controlling for illness severity and ICU-related conditions, ICU-acquired hypernatremia was an independent predictor of mortality and ICU length of stay, with a higher risk of mortality for the more severe hypernatremia.7 Our results confirm such findings in the Australian setting. However, the US investigators could only adjust for risk factors at admission and were unable to correct for events that occurred the day before the development of hypernatremia.

Ten years ago, an Australian study reviewed 10 years of ANZICS data and included 436,209 ICU patients. It reported that high levels of admission sodium were not associated with increased mortality.21 However, this study relied on admission sodium values and focused only on patients with respiratory diagnoses. Such patients likely did not have ICU-acquired hypernatremia, the subject of our investigation, which, as we show in our study, occurs on average four days after admission. Finally, they had no information available on the trajectory of hypernatremia or modifiable risk factors. Finally, several studies reported that hypernatremia was common among COVID-19 patients and was associated with increased mortality.[22], [23], [24], [25] We are the first to report on the increased prevalence of hypernatremia during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia.

4.3. Study implications

Our findings imply that, in Queensland (and likely elsewhere in Australia), ICU-acquired hypernatremia occurs in more than 7 % of patients. These also imply that the overall sodium correction rate in such patients is slow. In addition, they imply that crystalloid fluid administration, fever, and diuretic use are potentially modifiable factors for its occurrence. Finally, our data imply that there is an independent increase in mortality risk for all levels of hypernatremia and that such risk progressively increases with greater severity. As such, they provide a rationale for controlled studies of interventions aimed at the prevention and correction of hypernatremia prior to becoming moderate or severe.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. First, we collected seven years of data from a large cohort of ICU patients across the state of Queensland. This makes our data likely to be a robust representation of the overall ICU population in Australia and other resource-rich countries. Second, we used comprehensive granular data prospectively stored in a clinical database and then electronically extracted for the study. This helped to alleviate data errors and minimised potential recall bias. Third, our diagnosis of hypernatremia was clearly defined, and we categorised it by severity. This allowed us to study the association of different severity categories of hypernatremia. Moreover, for the first time, we were able to study the rate of correction of such hypernatremia and to demonstrate the slow rate of such correction. Finally, because of such granular data, we were able to adjust outcomes for major confounding variables, thus determining the independent association of hypernatremia with mortality.

We acknowledge some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study, and the quality of our results is reliant on the quality of the stored data. However, data were prospectively collected in the clinical database and routinely audited by independent clinical and technical staff to ensure its quality. Second, a few ICUs in Queensland did not use the electronic database for data collection. These were relatively smaller units, and given our vast sample size, their data would not materially alter our results. Third, the data were collected from several ICUs of different sizes and possibly different patient cohorts. This might pose the risk of a slight difference in practice; however, it also represents real-world clinical practice, making our data more realistic and representative of the general population. Fourth, our study was not designed to detect detailed data about the types of fluids administered, which could have contributed to the development of hypernatremia. Finally, our study is observational in design. Thus, the associations observed cannot be used to infer causality and are only hypothesis generating.

5. Conclusion

We conducted a large multicentric study using detailed electronic medical record-embedded data and found that ICU-acquired hypernatremia is common in critically ill patients and typically occurs on the fourth day of ICU admission. Moreover, diuretic use, fluid administration and fever are risk factors for its development, suggesting that measures could be taken to decrease risk. In addition, once hypernatremia occurs, its correction is slow, particularly when severe. Finally, after adjusting for multiple risk factors, all severities of hypernatremia are independently associated with an increased risk of mortality. These hypothesis-generating observations provide the necessary epidemiologic background and rationale for designing and powering interventional studies aimed at decreasing the prevalence and severity of ICU-acquired hypernatremia.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

The study conception and design (all authors); data acquisition (KW); analysis (AC); interpretation of data (all authors); article drafting (AN), article revision for important intellectual content (all authors); final approval of the version submitted for publication (all authors); agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved (KW, RB).

Data statement

Data cannot be shared publicly due to institutional ethics, privacy, and confidentiality regulations. Data released for the purposes of research under section 280 of the Public Health Act 2005 requires an application to the Director-General of Queensland Health (PHA@health.qld.gov.au).

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Prof Rinaldo Bellomo is on the Critical Care and Resuscitation Editorial Board If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the ANZICS CORE management committee and the clinicians, data collectors and researchers at the following contributing sites: Caboolture Hospital, Cairns Hospital, Gold Coast University Hospital, Logan Hospital, Mackay Base Hospital, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Redcliffe Hospital, Rockhampton Hospital, Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Sunshine Coast University Hospital, The Prince Charles Hospital, and The Townsville Hospital.

Collaborators - Queensland Critical Care Research Network Group.

Mahesh Ramanan, Prashanti Marella, Patrick Young, Philippa McIlroy, Ben Nash, James McCullough, Kerina J Denny, Mandy Tallott, Andrea Marshall, David Moore, Sunil Sane, Aashish Kumar, Lynette Morrison, Pam Dipplesman, Jennifer Taylor, Stephen Luke, Anni Paasilahti, Ray Asimus, Jennifer Taylor, Kyle White, Jason Meyer, Rod Hurford, Meg Harward, James Walsham, Neeraj Bhadange, Wayne Stevens, Kevin Plumpton, Sainath Raman, Andrew Barlow, Alexis Tabah, Hamish Pollock, Stuart Baker, Kylie Jacobs, Antony G. Attokaran, David Austin, Jacobus Poggenpoel, Josephine Reoch, Kevin B. Laupland, Felicity Edwards, Tess Evans, Jayesh Dhanani, Marianne Kirrane, Pierre Clement, Nermin Karamujic, Paula Lister, Vikram Masurkar, Lauren Murray, Jane Brailsford, Todd Erbacher, Kiran Shekar, Jayshree Lavana, George Cornmell, Siva Senthuran, Stephen Whebell, Michelle Gatton, Sam Keogh.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccrj.2024.09.003.

Contributor Information

Ahmad Nasser, Email: ahmad.nasser@health.qld.gov.au.

the Queensland Critical Care Research Network (QCCRN):

Mahesh Ramanan, Prashanti Marella, Patrick Young, Philippa McIlroy, Ben Nash, James McCullough, Kerina J. Denny, Mandy Tallott, Andrea Marshall, David Moore, Sunil Sane, Aashish Kumar, Lynette Morrison, Pam Dipplesman, Jennifer Taylor, Stephen Luke, Anni Paasilahti, Ray Asimus, Jennifer Taylor, Kyle White, Jason Meyer, Rod Hurford, Meg Harward, James Walsham, Neeraj Bhadange, Wayne Stevens, Kevin Plumpton, Sainath Raman, Andrew Barlow, Alexis Tabah, Hamish Pollock, Stuart Baker, Kylie Jacobs, Antony G. Attokaran, David Austin, Jacobus Poggenpoel, Josephine Reoch, Kevin B. Laupland, Felicity Edwards, Tess Evans, Jayesh Dhanani, Marianne Kirrane, Pierre Clement, Nermin Karamujic, Paula Lister, Vikram Masurkar, Lauren Murray, Jane Brailsford, Todd Erbacher, Kiran Shekar, Jayshree Lavana, George Cornmell, Siva Senthuran, Stephen Whebell, Michelle Gatton, and Sam Keogh

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lindner G., Funk G.-C. Hypernatremia in critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2013;28(2):11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.05.001. 216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chand R., Chand R., Goldfarb D.S. Hypernatremia in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2022;31(2):199–204. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tauseef A., Zafar M., Syed E., Thirumalareddy A., Sood N., Lateef N., et al. Prognostic importance of deranged sodium level in critically ill patients: a systemic literature to review. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2021;10(7):2477. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2291_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rugg C., Woyke S., Ronzani M., Markl-Le Levé A., Spraider P., Loveys S., et al. Catabolism highly influences ICU-acquired hypernatremia in a mainly trauma and surgical cohort. J Crit Care. 2023;76 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2023.154282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rugg C., Bachler M., Mösenbacher S., Wiewiora E., Schmid S., Kreutziger J., et al. Early ICU-acquired hypernatraemia is associated with injury severity and preceded by reduced renal sodium and chloride excretion in polytrauma patients. J Crit Care. 2021;65:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oude Lansink-Hartgring A., Hessels L., Weigel J., de Smet A.M.G., Gommers D., Panday P.V.N., et al. Long-term changes in dysnatremia incidence in the ICU: a shift from hyponatremia to hypernatremia. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waite M.D., Fuhrman S.A., Badawi O., Zuckerman I.H., Franey C.S. Intensive care unit–acquired hypernatremia is an independent predictor of increased mortality and length of stay. J Crit Care. 2013;28(4):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Donoghue S., Dulhunty J., Bandeshe H., Senthuran S., Gowardman J. Acquired hypernatraemia is an independent predictor of mortality in critically ill patients. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(5):514–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darmon M., Timsit J.-F., Francais A., Nguile-Makao M., Adrie C., Cohen Y., et al. Association between hypernatraemia acquired in the ICU and mortality: a cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(8):2510–2515. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stelfox H.T., Ahmed S.B., Khandwala F., Zygun D., Shahpori R., Laupland K. The epidemiology of intensive care unit-acquired hyponatraemia and hypernatraemia in medical-surgical intensive care units. Crit Care. 2008;12:1–8. doi: 10.1186/cc7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marella P., Ramanan M., Shekar K., Tabah A., Laupland K.B. Determinants of 90-day case fatality among older patients admitted to intensive care units: a retrospective cohort study. Aust Crit Care. 2024;37(1):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2023.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laupland K.B., Ramanan M., Shekar K., Edwards S., Clement P., Tabah A. Long-term outcome of prolonged critical illness: a multicentered study in North Brisbane, Australia. PLoS One. 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sieben N.A., Dash S. A retrospective evaluation of multiple definitions for ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) diagnosis in an Australian regional intensive care unit. Infection, Disease & Health. 2022;27(4):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2022.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White K., Tabah A., Ramanan M., Shekar K., Edwards F., Laupland K.B. 90-day case-fatality in critically ill patients with chronic liver disease influenced by presence of portal hypertension, results from a multicentre retrospective cohort study. J Intensive Care Med. 2023;38(1):5–10. doi: 10.1177/08850666221100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White K.C., Laupland K.B., See E., Serpa-Neto A., Bellomo R. Impact of continuous renal replacement therapy initiation on urine output and fluid balance: a multicenter study. Blood Purif. 2023;52(6):532–540. doi: 10.1159/000530146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raith E.P., Udy A.A., Bailey M., McGloughlin S., MacIsaac C., Bellomo R., et al. Prognostic accuracy of the SOFA score, SIRS criteria, and qSOFA score for in-hospital mortality among adults with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2017;317(3):290–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaukonen K.-M., Bailey M., Pilcher D., Cooper D.J., Bellomo R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1629–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna A., English S.W., Wang X.S., Ham K., Tumlin J., Szerlip H., et al. Angiotensin II for the treatment of Vasodilatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):419–430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahan B.C., Forbes G., Cro S. How to design a pre-specified statistical analysis approach to limit p-hacking in clinical trials: the Pre-SPEC framework. BMC Med. 2020;18:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01706-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Royston P., Sauerbrei W. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. Multivariable model-building: a pragmatic approach to regression anaylsis based on fractional polynomials for modelling continuous variables. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bihari S., Peake S.L., Bailey M., Pilcher D., Prakash S., Bersten A. Admission high serum sodium is not associated with increased intensive care unit mortality risk in respiratory patients. J Crit Care. 2014;29(6):948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirsch J.S., Uppal N.N., Sharma P., Khanin Y., Shah H.H., Malieckal D.A., et al. Prevalence and outcomes of hyponatremia and hypernatremia in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;36(6):1135–1138. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfab067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu W., lv X., Li C., Xu Y., Qi Y., Zhang Z., et al. Disorders of sodium balance and its clinical implications in COVID-19 patients: a multicenter retrospective study. Internal and Emergency. Medicine. 2021;16(4):853–862. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02515-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Y., Zhang P., Hou M. Association of hypernatremia with mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Immunity, Inflammation and Disease. 2023;11(12) doi: 10.1002/iid3.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrestha A.B., Sapkota U.H., Shrestha S., Aryal M., Chand S., Thapa S., et al. Association of hypernatremia with outcomes of COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2022;101(51) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000032535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.