Abstract

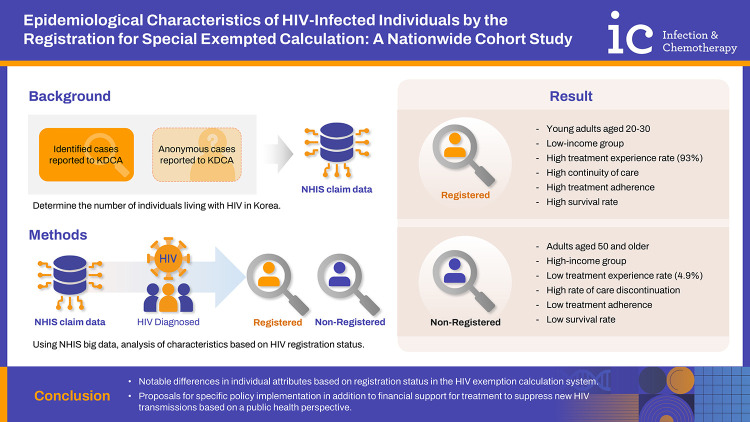

Background

The Korean government is implementing policy to reduce medical costs and improve treatment related for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients. The level of cost reduction and the benefits provided vary depending on how individuals with HIV utilize the system. This study aims to determine exact HIV prevalence by analyzing healthcare utilization patterns and examining differences in healthcare usage based on how individuals pay for their medical expenses.

Materials and Methods

We analyzed National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) claims data from 2002 to 2021. From a total of 106,675 individuals with at least one HIV-related claim, 22,779 participants were selected for this study.

Results

Data from Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency annual reports indicated that 93% of HIV patients were male, while NHIS data showed 84%. In the analysis of those exempted from registration, it was found that the registration rate for female patients is notably low, with adults between the ages of 20 and 40 making up 80% of the total. The registration rate in Gangwon State was lower than Seoul. The treatment experience rate was much higher in the registered group (93.0%) than the unregistered group (4.9%). Also, there was a big difference in treatment continuity rates: 76.2% for registered individuals and 2.8% for non-registered individuals.

Conclusion

The exempt calculation system for health insurance improves HIV care. However, those diagnosed anonymously or with reduced medical costs may be less likely to continue HIV treatment, so a new policy is needed to ensure anonymity and treatment continuity.

Keywords: HIV care continuum, Antiretroviral therapy, HIV transmission, Medical service utilization, Exempted calculation system of health insurance

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Global human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection rates have decreased due to various efforts, including prevention strategies [1]. However, HIV infections in Korea have consistently risen since 2013. Although the number of new infections in 2020–2021 were lower due to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic's impact on testing services at local health centers, experts suggest an increased risk of delayed diagnoses [2]. The Korean government oversees the health insurance system, allowing citizens to join the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) as employees, local subscribers, or medical benefit recipients. Foreign full-time workers or business owners in Korea can also enroll in NHIS as employees and local subscribers. Data from the Korea Institute of Health and Social Affairs and Statistics Korea indicate a 0.00% uninsured rate in 2021 [3]. As of 2004, Korea has implemented a unique calculation system allowing for exemptions for individuals with HIV. HIV positive beneficiaries receive a 90% subsidy on expenses out-of-pocket expenses from the health insurance agency. In order to obtain the specified benefit from the National Health Insurance Corporation, it is necessary to include the designated special exempted calculation code (V103) or the HIV-related diagnostic codes (B20-B24) with each claim. Patients may get a 90% reduction in out-of-pocket expenses if their treatment is found to be HIV-related by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Additionally, patients registered through real-name authentication with the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) will receive further support, as the remaining 10% of the costs will be shared by the government and local authorities. All HIV-infected individuals using their real names can access HIV medical services for free.

In Korea, HIV is a Class 3 legal communicable disease, necessitating hospitals or healthcare centers to promptly notify the KDCA of confirmed cases. Despite this reporting system’s structure, we anticipate instances of underreporting for various reasons [4]. HIV-infected individuals have the option to report anonymously during the procedure. Identified individuals must provide their sex, nationality, date of birth, test results, mode of transmission, clinical status, and confirmation date, while anonymous individuals only need to provide their sex, nationality, confirmation date, and confirming institution. The KDCA's annual HIV report may may overestimate the number of cases due to individuals who undergo multiple anonymous tests in a year. For this reason, the total number of new cases does not include anonymous cases, and the annual count of anonymous cases is presented separately.

The aim of this study is to analyze NHIS medical claims data to determine the precise number of individuals with HIV in Korea, and to investigate their demographic traits and patterns of healthcare usage.

Materials and Methods

1. Research participants

Four exclusion criteria were applied to determine the research participants. 1) No eligibility health insurance information, 2), those who first confirmed HIV infection at the time of death, 3) those who were unidentified at the time of HIV-related first medical claim (wash-out), and 4) with all HIV-related claims as rule-out cases or those with only one HIV-related claim in their lifetime, resulting in a total of 22,779 subjects (Supplementary Fig. 1).

2. Ethics statement

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Hanyang University (IRB No. HYU-2021-212), and due to its use of secondary data without conducting further investigation or causing harm to the research subjects, consent for the study was not required.

3. Operational definition

Reported people living with HIV are based on KDCA notification data and encompass characteristics of all HIV-related healthcare encounters (excluding ruled-out claims), including those with undiagnosed HIV. As of 2004, individuals are categorized as people living with HIV if they have been assigned the specific coding (V103) at least once or have received HIV-related diagnosis codes (B20-B24) two or more times in their lifetime. Experience with antiretroviral therapy (ART) means consistently taking ART medication for more than 30 days. ART adherence was classified according to the highest and mean levels recorded. ART adherence is calculated by dividing the total days of prescribed medication by the interval until the next prescription. A value of 1.0 indicates that the patient followed the treatment by getting their next prescription at the appropriate time. A score between 0.8 and 1.3 indicates good ART adherence, taking into account weekend and outpatient schedule availability. A value below 1.0 indicates a delay in taking prescribed ART. A value greater than 1.0 means the patient sought a prescription earlier than expected based on the prescription. The maximum ART adherence is the highest among all adherence measurements for each visit, while the average is the mean ART adherence calculated by the frequency of the prescription. The interpretation method stays the same. The diagnosis of HIV-related diseases and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illnesses has been defined through the claims of principal diagnoses (main diagnosis) that have not been considered ruled-out cases (Supplementary Table 1). Death and the cause of death were built by combining data from the NHIS with the cause of death database from Statistics Korea. The cause of death is officially determined by a death certificate, which may not accurately identify the specific direct or underlying cause of death.

4. Statistical method

Characteristics of infected individuals are presented as frequency and percentage. Comparisons of categorical variables were made using the Chi-squared test. All analyses were performed using the SAS Enterprise Guide (7.1 version, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). Statistical significance was set at P=0.05.

Results

Using NHIS claims data (2002–2021) from the National Health Insurance Corporation, we analyzed 106,675 individuals with at least one HIV-related claim. A total of 83,896 subjects were excluded based on the criteria. Billing for HIV-related claims involves two categories: registration under the claim with an exempted calculation system and use of diagnostic codes (B20–B24) representing HIV diagnosis. Due to privacy concerns, medical expense support, including copayments, relies solely on diagnostic codes. Until 2004, there were 2,484 cumulative new infections, increasing to over 1,000 annually since 2014. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic led to 1,071 cases reported in 2020. As of 2020, cumulative infections were 22,779, with 19,365 surviving. Among them, 14,627 had HIV as the primary diagnosis, with the majority under the claim with an exempted calculation system (Table 1).

Table 1. Annualized healthcare utilization rate with HIV as main diagnosis for people living with HIV.

| Year | New infection | Cumulative N (A) | Cumulative death (B) | Cumulative survive N (C=A−B) | Total medical care user | Exempted calculation | HIV diagnosis code | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical care user (D) | Rate of medical care (D/C) | Medical care user (E) | Rate of medical care (E/C) | ||||||

| –2004 | 2,484 | 2,484 | 32 | 2,452 | 2,415 | 668 | 0.28 | 1,834 | 0.75 |

| 2005 | 1,013 | 3,497 | 84 | 3,413 | 2,263 | 1,843 | 0.54 | 420 | 0.12 |

| 2006 | 1,036 | 4,533 | 166 | 4,367 | 2,918 | 2,449 | 0.56 | 469 | 0.11 |

| 2007 | 1,228 | 5,761 | 297 | 5,464 | 3,858 | 2,958 | 0.54 | 900 | 0.16 |

| 2008 | 1,361 | 7,122 | 434 | 6,688 | 4,628 | 3,484 | 0.52 | 1,144 | 0.17 |

| 2009 | 1,361 | 8,483 | 599 | 7,884 | 5,355 | 4,073 | 0.52 | 1,282 | 0.16 |

| 2010 | 1,223 | 9,706 | 798 | 8,908 | 5,863 | 4,695 | 0.53 | 1,168 | 0.13 |

| 2011 | 1,350 | 11,056 | 1,004 | 10,052 | 6,756 | 5,259 | 0.52 | 1,497 | 0.15 |

| 2012 | 1,182 | 12,238 | 1,220 | 11,018 | 7,285 | 5,852 | 0.53 | 1,433 | 0.13 |

| 2013 | 1,273 | 13,511 | 1,467 | 12,044 | 8,052 | 7,103 | 0.59 | 949 | 0.08 |

| 2014 | 1,340 | 14,851 | 1,719 | 13,132 | 9,008 | 8,160 | 0.62 | 848 | 0.06 |

| 2015 | 1,326 | 16,177 | 2,016 | 14,161 | 10,008 | 9,101 | 0.64 | 907 | 0.06 |

| 2016 | 1,385 | 17,562 | 2,290 | 15,272 | 11,029 | 10,100 | 0.66 | 929 | 0.06 |

| 2017 | 1,383 | 18,945 | 2,558 | 16,387 | 12,030 | 11,101 | 0.68 | 929 | 0.06 |

| 2018 | 1,389 | 20,334 | 2,848 | 17,486 | 13,026 | 12,041 | 0.69 | 985 | 0.06 |

| 2019 | 1,374 | 21,708 | 3,135 | 18,573 | 14,058 | 13,042 | 0.70 | 1,016 | 0.05 |

| 2020 | 1,071 | 22,779 | 3,414 | 19,365 | 14,627 | 13,719 | 0.71 | 908 | 0.05 |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Approximately 68% of infected individuals were aged 20–40, with the registration rate notably higher for those in their 20s and 30s. The percentage of 20s to 30s registration rate is notably higher. However, more middle-aged adults aged 50 and above were found among unregistered infected individuals (P<0.0001). There was a significant difference in income distribution between registered and unregistered individuals, with more registered people earning below 50% of the income compared to unregistered people. Conversely, the percentage of high-income individuals in the top 25th percentile was greater in the group that was not registered (P<0.0001). Registered participants were more likely to enroll through their employer (subscriber) than unregistered participants, who had a higher percentage of dependents covered by the dependent subscriber by the employer (P<0.0001). Those with disabilities were more common in the unregistered group (P<0.0001). Among study population, 52.2% did not have stable employment or consistent income, with the unregistered group showing a slightly higher percentage. There was a similar in occupational categories based on registration status (P<0.0001). The registered group had more people from Seoul and Gyeonggi, while the unregistered group had more residents from Daegu/Gyeongbuk or Gangwon (P<0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2. General characteristics of people living with HIV in Korea by the type of HIV-related healthcare utilization.

| Characteristics | N (col %) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | With exempted calculation | Only diagnostic code | |||

| N | 22,779 (100) | 17,549 (77.0) | 5,230 (23.0) | ||

| Sex | <0.0001 | ||||

| Men | 18,921 (83.1) | 15,950 (90.9) | 2,971 (56.8) | ||

| Women | 3,858 (16.9) | 1,599 (9.1) | 2,259 (43.2) | ||

| Age at first HIV claim | <0.0001 | ||||

| <20 | 841 (3.7) | 448 (2.6) | 393 (7.5) | ||

| 20–29 | 5,238 (23.0) | 4,624 (26.3) | 614 (11.7) | ||

| 30–39 | 5,543 (24.3) | 4,664 (26.6) | 878 (16.8) | ||

| 40–49 | 4,773 (21.0) | 3,819 (21.8) | 954 (18.2) | ||

| 50–59 | 3,375 (14.8) | 2,519 (14.4) | 856 (16.4) | ||

| 60–69 | 1,799 (7.9) | 1,050 (6.0) | 749 (14.3) | ||

| ≥70 | 1,211 (5.3) | 425 (2.4) | 786 (15.0) | ||

| Income level | <0.0001 | ||||

| Low income class with assistanta | 1,263 (5.5) | 766 (4.4) | 497 (9.5) | ||

| 25% | 5,003 (22.0) | 4,075 (23.2) | 928 (17.7) | ||

| 26–50% | 5,693 (25.0) | 4,671 (26.6) | 1,022 (19.5) | ||

| 51–75% | 5,301 (23.3) | 4,083 (23.3) | 1,218 (23.3) | ||

| 76–100% | 5,132 (22.5) | 3,696 (21.1) | 1,436 (27.5) | ||

| Missingb | 387 (1.7) | 258 (1.5) | 129 (2.5) | ||

| Insurance type | <0.0001 | ||||

| Local subscriber | 5,626 (24.7) | 4,637 (26.4) | 989 (18.9) | ||

| Local subscriber (dependent) | 3,923 (17.2) | 3,036 (17.3) | 887 (17.0) | ||

| Employee | 6,707 (29.4) | 5,520 (31.5) | 1,187 (22.7) | ||

| Employee (dependent) | 5,260 (23.1) | 3,590 (20.5) | 1,670 (31.9) | ||

| Medical benefic | 994 (4.4) | 600 (3.4) | 394 (7.5) | ||

| Medical benefit (dependent) | 269 (1.2) | 166 (0.9) | 103 (2.0) | ||

| Disability grade | <0.0001 | ||||

| None | 21,192 (93.0) | 16,790 (95.7) | 4,402 (84.2) | ||

| 1 | 93 (0.4) | 44 (0.3) | 49 (0.9) | ||

| 2–5 | 1,122 (4.9) | 474 (2.7) | 648 (12.4) | ||

| 6–13 | 372 (1.6) | 241 (1.4) | 131 (2.5) | ||

| Disability type | <0.0001 | ||||

| None | 21,192 (93.0) | 16,790 (95.7) | 4,402 (84.2) | ||

| Physical disability | 574 (2.5) | 341 (1.9) | 233 (4.5) | ||

| Renal disability | 352 (1.6) | 36 (0.2) | 316 (0.6) | ||

| Visual impairment | 176 (0.8) | 108 (0.6) | 68 (1.3) | ||

| Hearing impairment | 163 (0.7) | 117 (0.7) | 46 (0.9) | ||

| Brain lesion | 94 (0.4) | 58 (0.3) | 36 (0.7) | ||

| Other disability | 228 (1.0) | 99 (0.6) | 129 (0.2) | ||

| Occupation | <0.0001 | ||||

| Manufacturing | 2,985 (13.1) | 2,307 (13.1) | 678 (13.0) | ||

| Real estate activities and renting and leasing | 1,742 (7.7) | 1,417 (8.1) | 325 (6.2) | ||

| Wholesale and retail trade or repair services | 1,369 (6.0) | 1,100 (6.3) | 269 (5.1) | ||

| Public-social or personal service activities | 785 (3.5) | 644 (3.7) | 141 (2.7) | ||

| Human health and social work activities | 739 (3.2) | 513 (2.9) | 226 (4.3) | ||

| Transportation,storage, telecommunications | 660 (2.9) | 527 (3.0) | 133 (2.5) | ||

| Construction | 660 (2.9) | 478 (2.7) | 182 (3.5) | ||

| Accommodation and food service activities | 489 (2.1) | 430 (2.5) | 59 (1.1) | ||

| Education | 446 (2.0) | 350 (2.0) | 96 (1.8) | ||

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 392 (1.7) | 308 (1.8) | 84 (1.6) | ||

| Financial and insurance activities | 383 (1.7) | 266 (1.5) | 117 (2.2) | ||

| Other | 244 (1.1) | 178 (1.0) | 66 (1.3) | ||

| Missingc | 11,885 (52.2) | 9,031 (51.5) | 2,854 (54.6) | ||

| Region | <0.0001 | ||||

| Seoul | 7,061 (31.0) | 5,985 (34.1) | 1,076 (20.6) | ||

| Gyeonggi/Incheon | 6,020 (26.4) | 4,971 (28.3) | 1,049 (20.1) | ||

| Busan/Ulsan/Gyeongnam | 2,649 (11.6) | 2,234 (12.7) | 415 (7.9) | ||

| Daegu/Gyeongbuk | 1,528 (6.7) | 1,128 (6.4) | 400 (7.6) | ||

| Gwangju/Jeolla | 1,964 (8.6) | 1,236 (7.0) | 728 (13.9) | ||

| Daejeon/Sejong/Chungcheong | 1,931 (8.5) | 1,456 (8.3) | 475 (9.1) | ||

| Gangwon | 1,333 (5.9) | 305 (1.7) | 1,028 (19.7) | ||

| Jeju | 225 (1.0) | 179 (1.0) | 46 (0.9) | ||

| Missingd | 68 (0.3) | 55 (0.3) | 13 (0.2) | ||

aThe demographic group that receives governmental living subsidies.

bIndividuals whose accurate income levels were not ascertained at the time of their initial HIV claim (those lacking income associated with health insurance).

cIndividuals without prior business-related health insurance data at the time of their initial HIV claim may encompass dependents subscribers, self-employed individuals, or freelancers.

dThe administrative address was not ascertainable at the onset of the HIV claim.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Clinics and general hospitals accounted for 45.5% of initial HIV claims, and 54.5% of cases were from institutions with missing data. HIV individuals without registration, 63.5% of claims from institutions did not identify as clinics or general hospitals. There was a difference in the rate of initial HIV claims at clinics or hospitals among registered cases compared to other groups (P<0.0001). Seventy-three percent of the subject's first HIV claims were in internal medicine, increasing to eighty-one percent within the registered group, compared to only forty-four percent among those not registered. Notably, institutions without specific treatment specialties accounted for 22.3% of claims among unregistered participants (P<0.0001). During the initial HIV-related claim, 72.3% were outpatient visits, 19.4% were inpatient care, and 8.3% were unverifiable. No subjects had surgery on their first visit, 68.1% received continued care and 14.6% terminated. In the unregistered group, 32.9% of subjects had missing outcome data, showing a significant difference. Initial claims for HIV as the primary diagnosis accounted for 65.5% of the total, with 77.6% of registered individuals. compared to 74.9% of unregistered individuals who received bills for non-HIV-related disease as a main disease (P<0.0001). Before switching to exempted calculation, 71.6% of individuals had not filed HIV claims, and 28.4% had filed an HIV claim. 37% of individuals who had been diagnosed with HIV-related disease before their first HIV claims, had discrepancies by registration status 39.3% for registered subjects and 29.3% for unregistered subjects (P<0.0001). Before being diagnosed with HIV, 32.9% of individuals had an AIDS-defining illness, with differences between those registered (35.2%) and those not registered (25.3%), showing a lower rate in the non-registered group (P<0.0001). The treatment experience rate was significantly higher among registered individuals (93.0%) compared to unregistered individuals (4.9%) (P<0.0001). Among unregistered patients, 40.8%-received treatment within 3 months, while 43.6% of registered patients received treatment over 10 years or more (P<0.0001). In the registered patient group, 81.9% followed treatment compared to 43.5% in the unregistered group, showing a significant difference (P<0.0001). Patients demonstrated an ART adherence rate (treatment compliance) of over 97.3% for scheduled appointments. Among unregistered patients, 31% didn't return for follow-up visits, and only 52.9% stuck to their medical schedule or attended appointments early. Registered individuals had a 75.2% adherence rate to scheduled visits, while the unregistered cohort had a 31.0% non-return rate and attended visits as scheduled only 29.0% of the time, showing lower ART adherence in the unregistered group (P<0.0001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Timing at HIV first claim and the ART-related characteristics by the type of HIV-related healthcare utilization.

| Characteristics | N (column %) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | With exempted calculation | Only diagnostic code | ||||

| N | 22,779 (100) | 17,549 (77.0) | 5,230 (23.0) | |||

| Healthcare provider | <0.0001 | |||||

| General hospital | 4,442 (19.5) | 3,613 (20.6) | 829 (15.9) | |||

| Clinic | 5,927 (26.0) | 4,849 (27.6) | 1,078 (20.6) | |||

| Missinga | 12,410 (54.5) | 9,087 (51.8) | 3,323 (63.5) | |||

| Medical subject | <0.0001 | |||||

| Internal medicine | 16,656 (73.1) | 14,327 (81.6) | 2,329 (44.5) | |||

| General | 779 (3.4) | 584 (3.3) | 195 (3.7) | |||

| General surgery | 493 (2.2) | 316 (1.8) | 177 (3.4) | |||

| Dermatology | 415 (1.8) | 230 (1.3) | 185 (3.5) | |||

| Orthosurgery | 359 (1.6) | 168 (1.0) | 191 (3.7) | |||

| Neurosurgery | 348 (1.5) | 146 (0.8) | 202 (3.9) | |||

| Otorhinolaryngology | 324 (1.4) | 157 (0.9) | 167 (3.2) | |||

| Neuropsychiatry | 224 (1.0) | 182 (1.0) | 42 (0.8) | |||

| Family medicine | 220 (1.0) | 119 (0.7) | 101 (1.9) | |||

| Emergency medicine | 208 (0.9) | 152 (0.9) | 56 (1.1) | |||

| Other | 861 (3.8) | 441 (2.5) | 420 (8.0) | |||

| Missingb | 1,892 (8.3) | 727 (4.1) | 1,165 (22.3) | |||

| Type of initial HIV claims | <0.0001 | |||||

| Inpatient | 4,423 (19.4) | 3,889 (22.2) | 534 (10.2) | |||

| Outpatient | 16,464 (72.3) | 12,933 (73.7) | 3,531 (67.5) | |||

| Unknownc | 1,892 (8.3) | 727 (4.1) | 1,165 (22.3) | |||

| Result of initial HIV claim | <0.0001 | |||||

| Follow up | 15,501 (68.1) | 12,361 (70.4) | 3,140 (60.0) | |||

| Transfer/forwarding | 200 (0.9) | 178 (1.0) | 22 (0.4) | |||

| Termination | 3,314 (14.6) | 3,035 (17.3) | 279 (5.3) | |||

| Death | 211 (0.9) | 141 (0.8) | 70 (1.3) | |||

| Missingd | 3,553 (15.6) | 1,834 (10.5) | 1,719 (32.9) | |||

| Main disease at initial HIV claim | <0.0001 | |||||

| HIV | 14,928 (65.5) | 13,616 (77.6) | 1,312 (25.1) | |||

| Non-HIV | 7,851 (34.5) | 3,933 (22.4) | 3,918 (74.9) | |||

| HIV claims before diagnosise | - | |||||

| None | 17,793 (78.1) | 12,563 (71.6) | 5,230 (100) | |||

| 1 | 2,223 (9.8) | 2,223 (12.7) | 0 | |||

| 2–10 | 1,820 (8.0) | 1,820 (10.4) | 0 | |||

| >10 | 943 (4.1) | 943 (5.4) | 0 | |||

| HIV-related disease before the HIV first claim | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0 | 14,357 (63.0) | 10,660 (60.7) | 3,697 (70.7) | |||

| 1 | 5,805 (25.5) | 4,713 (26.9) | 1,092 (20.9) | |||

| 2 or more | 2,617 (11.5) | 2,176 (12.4) | 441 (8.4) | |||

| AIDS defining illness before the HIV first claim | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0 | 15,276 (67.1) | 11,369 (64.8) | 3,907 (74.7) | |||

| 1 | 5,593 (24.6) | 4,468 (25.5) | 1,125 (21.5) | |||

| 2 or more | 1,910 (8.4) | 1,712 (9.8) | 198 (3.8) | |||

| ART experience | <0.0001 | |||||

| No | 6,195 (27.2) | 1,220 (7.0) | 4,975 (95.1) | |||

| Yes | 16,584 (72.8) | 16,329 (93.0) | 255 (4.9) | |||

| ART duration | <0.0001 | |||||

| 3 months | 434 (2.6) | 330 (2.0) | 104 (40.8) | |||

| 6 months | 419 (2.5) | 380 (2.3) | 39 (15.3) | |||

| 12 months | 723 (4.4) | 681 (4.2) | 42 (16.5) | |||

| 3 years | 2,667 (16.1) | 2,629 (16.1) | 38 (14.9) | |||

| 5 years | 2,494 (15.0) | 2,479 (15.2) | 15 (5.9) | |||

| 10 years | 2,716 (16.4) | 2,708 (16.6) | 8 (3.1) | |||

| Over 10 years | 7,131 (43.0) | 7,122 (43.6) | 9 (3.5) | |||

| ART retention in caref | <0.0001 | |||||

| Continuation | 13,520 (81.5) | 13,376 (81.9) | 144 (56.5) | |||

| Interruption | 3,064 (18.5) | 2,953 (18.1) | 111 (43.5) | |||

| ART adherence (Max)g | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0 | 339 (2.0) | 260 (1.6) | 79 (31.0) | |||

| <0.5 | 92 (0.6) | 77 (0.5) | 15 (5.9) | |||

| <0.8 | 130 (0.8) | 104 (0.6) | 26 (1.2) | |||

| <1.3 | 6,649 (40.1) | 6,573 (40.3) | 76 (29.8) | |||

| ≥1.3 | 9,374 (56.5) | 9,315 (57.0) | 59 (23.1) | |||

| ART adherence (Mean)h | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0 | 339 (2.0) | 260 (1.6) | 79 (31.0) | |||

| <0.5 | 137 (0.8) | 116 (0.7) | 21 (8.2) | |||

| <0.8 | 2,835 (17.1) | 2,782 (17.0) | 53 (20.8) | |||

| <1.3 | 12,350 (74.5) | 12,276 (75.2) | 74 (29.0) | |||

| ≥1.3 | 923 (5.6) | 895 (5.5) | 28 (11.0) | |||

aThe data concerning the medical institutions in which the initial HIV cases were reported is unavailable. Possible indicators could comprise hospitals, convalescent hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, midwife centers, maternal and child health centers, public health centers, community health centers, local public health clinics, and public health clinics.

bThe precise medical subjects at the initial visit for HIV claims cannot be identified. This may encompass hospitals or clinics offering various medical services, including those where specific medical specialties are not delineated.

cIf a healthcare facility was accessed for reasons beyond outpatient care or hospitalization during the initial HIV claim stage, such as for emergency services or examinations, this scenario may be relevant. Nevertheless, the exact reasons cannot be differentiated.

dIf a healthcare facility was accessed for reasons except outpatient care or hospitalization during the initial HIV claim stage, such as for emergency services or examinations, this scenario may be relevant. Nevertheless, the exact reasons cannot be differentiated.

eUnlike the initial HIV claim, the first time of HIV diagnosis refers to a claim for a primary illness (main diagnosis) where HIV-related diagnostic codes are included and are not defined as ruled-out cases. This may occur on the same day as the initial claim or may represent a subsequent claim made after the date of the initial claim.

fThe ART retention in care by analyzing whether the medication was consistently prescribed until the final observation period or cessation due to mortality post the initial ART prescription. If treatment was prescribed regularly, even if not administered consecutively, it falls under the category of 'continuation.'

g , The highest ART adherence across all treatment sessions.

, The highest ART adherence across all treatment sessions.

h , The average ART adherence across all treatment session.

, The average ART adherence across all treatment session.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

In total, 15% of infected individuals were deceased, and the registration rate under the claim with an exempted calculation system for deceased individuals (12.4%) is significantly lower than that for unregistered individuals (23.6%) (P<0.0001). AIDS-related deaths constitute 48%, with higher percentages among claims with exempted calculation system registrants (62.8%) compared to non-registrants (21.8%) (Table 4). Examining HIV medical utilization periods, 75.3% receive diagnoses on the same day as the initial claim. Immediate ART initiation occurs in 23.7%. Delayed initiation was more common among individuals registered under the exempted calculation system (P<0.0001). Similar patterns are observed for the period from HIV confirmation to ART prescription. Survival periods of less than 1-month account for 2.4%, slightly higher in the diagnosis code group (P<0.0001). Individuals surviving for more than 5 years are 7.4 percentage points higher in the diagnosis code group (P<0.0001). Similar trends are noted for the period from initial confirmation to death or the last visit (P<0.0001). A significantly higher proportion of survivors who underwent initial treatment for more than five years were recorded in the exempted calculation, compared to those who were not registered, with survival rates of 61.1% and 25.1% respectively (P<0.0001) (Table 5).

Table 4. Mortality rates and causes of death by the type of HIV-related healthcare utilization.

| Characteristics | N (column %) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | With exempted calculation | Only diagnostic code | |||

| Death | <0.0001 | ||||

| No | 19,365 (85.0) | 15,369 (87.6) | 3,996 (76.4) | ||

| Yes | 3,414 (15.0) | 2,180 (12.4) | 1,234 (23.6) | ||

| Cause of Death | <0.0001 | ||||

| AIDS-related | 1,639 (48.0) | 1,370 (62.8) | 269 (21.8) | ||

| Non-AIDS related cancer | 408 (12.0) | 174 (8.0) | 234 (19.0) | ||

| Accidents, self-harm, and damage | 307 (9.0) | 218 (10.0) | 89 (7.2) | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 100 (2.9) | 46 (2.1) | 54 (4.4) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 88 (2.6) | 10 (11.4) | 78 (6.3) | ||

| Endocrine-related disorder or disease | 86 (2.5) | 17 (0.8) | 69 (5.6) | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease orpathogenic pneumonia | 86 (2.5) | 35 (1.6) | 51 (4.1) | ||

| Due to unexplained causes | 84 (2.5) | 42 (1.9) | 42 (3.4) | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | 75 (2.2) | 37 (1.7) | 38 (3.1) | ||

| Mental and neurocognitive disorders, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's | 58 (1.7) | 12 (0.6) | 46 (3.7) | ||

| Liver disease | 56 (1.6) | 23 (1.1) | 33 (2.7) | ||

| Other heart diseasea | 50 (1.5) | 23 (1.1) | 27 (2.2) | ||

| Other bacterial/viral infections | 49 (1.4) | 22 (1.0) | 27 (2.2) | ||

| Frailty (aging) | 34 (1.0) | 9 (0.4) | 25 (2.0) | ||

| Others | 163 (4.8) | 59 (2.7) | 104 (8.4) | ||

| Missingb | 131 (3.8) | 83 (3.8) | 48 (3.9) | ||

aMyocarditis, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, cardiac arrest, etc.

bIndividuals for whom the cause of death could not be ascertained based on the mortality data provided by the Statistics Korea.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

Table 5. Characteristics of duration indicators related to HIV care linkage and persistence by the type of HIV-related healthcare utilization.

| Characteristics | N (column %) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | With exempted calculation | Only diagnostic code | |||

| N | 22,779 (100) | 17,549 (77.0) | 5,230 (23.0) | ||

| First claim to diagnosis | <0.0001 | ||||

| Same day | 17,150 (75.3) | 11,920 (67.9) | 5,230 (100) | ||

| Within 1 month | 2,809 (12.3) | 2,809 (16.0) | 0 | ||

| 2–12 months | 1,571 (6.9) | 1,571 (9.0) | 0 | ||

| 1–3 years | 855 (3.8) | 855 (4.9) | 0 | ||

| Over 3 years | 394 (1.7) | 394 (2.3) | 0 | ||

| First claim to initial ARTa,b | <0.0001 | ||||

| Same day | 3,928 (23.7) | 3,764 (23.1) | 164 (64.3) | ||

| Within 1 month | 6,290 (37.9) | 6,244 (38.2) | 46 (18.0) | ||

| 2–12 months | 2,887 (17.4) | 2,858 (17.5) | 29 (11.4) | ||

| 1–3 years | 1,576 (9.5) | 1,569 (9.6) | 7 (2.8) | ||

| Over 3 years | 1,903 (11.5) | 1,894 (11.6) | 9 (3.5) | ||

| First diagnosis to initial ARTa,b,c | <0.0001 | ||||

| Same day | 4,232 (25.5) | 4,059 (24.9) | 173 (67.8) | ||

| Within 1 month | 6,198 (37.4) | 6,158 (37.7) | 40 (15.7) | ||

| 2–12 months | 2,753 (16.6) | 2,726 (16.7) | 27 (10.6) | ||

| 1–3 years | 1,555 (9.4) | 1,548 (9.5) | 7 (2.8) | ||

| Over 3 years | 1,846 (11.1) | 1,838 (11.3) | 8 (3.1) | ||

| First claim to death or last visit | <0.0001 | ||||

| Within 1 month | 552 (2.4) | 380 (2.2) | 172 (3.3) | ||

| 2–12 months | 1,977 (8.7) | 1,528 (8.7) | 449 (8.6) | ||

| 1–3 years | 3,178 (14.0) | 2,577 (14.7) | 601 (11.5) | ||

| 3–5 years | 2,969 (13.0) | 2,504 (14.3) | 465 (8.9) | ||

| Over 5 years | 14,103 (61.9) | 10,560 (60.2) | 3,543 (67.7) | ||

| First diagnosis to death or last visitc | <0.0001 | ||||

| Within 1 month | 566 (2.5) | 387 (2.2) | 179 (3.4) | ||

| 2–12 months | 1,989 (8.7) | 1,541 (8.8) | 448 (8.6) | ||

| 1–3 years | 3,193 (14.0) | 2,588 (14.8) | 605 (11.6) | ||

| 3–5 years | 2,974 (13.1) | 2,502 (14.3) | 472 (9.0) | ||

| Over 5 years | 14,057 (61.7) | 10,531 (60.0) | 3,526 (67.4) | ||

| Initial ART to death or last visita | <0.0001 | ||||

| Within 1 month | 166 (1.0) | 151 (0.9) | 15 (5.9) | ||

| 2–12 months | 1,480 (8.9) | 1,360 (8.3) | 120 (47.1) | ||

| 1–3 years | 2,502 (15.1) | 2,463 (15.1) | 39 (15.3) | ||

| 3–5 years | 2,400 (14.5) | 2,383 (14.6) | 17 (6.7) | ||

| Over 5 years | 10,036 (60.5) | 9,972 (61.1) | 64 (25.1) | ||

a16,584 people who were prescribed ART medications as a combination for 30 days or more.

bThe recommendations for ART therapy have changed over time, however, by the regulations governing the use of National Health Insurance Corporation data, results cannot be disclosed or utilized when the frequency of any cell is less than 2. This limitation has hindered our ability to distinguish between the diagnosis year and the treatment initiation year.

cUnlike the initial HIV claim, the first time of HIV diagnosis refers to a claim for a primary illness (main diagnosis) where HIV-related diagnostic codes are included and are not defined as ruled-out cases. This may occur on the same day as the initial claim or may represent a subsequent claim made after the date of the initial claim.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Discussion

This study aimed to understand the characteristics of the target group and the difference between treatment persistence and management of HIV-infected individuals in Korea. A significant disparity was observed between the number of reported infected individuals from the KDCA and the NHIS (Supplementary Table 2). The first HIV case in Korea was reported in 1985, and medical coverage began in 1989, evolving over the years [2]. Selective coverage for non-reimbursable items was introduced in 2017 to reduce medical costs for HIV patients [4]. To benefit from the treatment cost reduction program, HIV-infected individuals need to enroll in the NHIS with a V103 code or receive benefits through HIV-related diagnosis codes B20 to B24. Registration allows recognition as eligible for benefit of medical cost, qualifying for medical benefit. Even without registration, HIV-infected individuals can submit a diagnosis certificate for medical benefit services. However, registered individuals receive exemptions for personal expenses, while non-registered individuals contribute to their expenses, supported by health maintenance expenses [4].

Comprehensive surveillance is conducted on HIV-infected individuals, and the claim with the exempted calculation system was initiated in 2004. The cumulative number difference until 2020 was approximately 10%, with only 84.7% of reported cases registered in the exempted calculation system, suggesting potential omissions. Healthcare utilization rates varied based on the registration of the system. Examining treatment continuity, the cumulative experience rate increased from 24.0% in 2004 to 73.3% in 2020 (Supplementary Table 3). Most individuals with treatment experience are system registrants. Those relying solely on HIV-related diagnosis codes without registration exhibit lower retention in care, impacting HIV prevention. Based on the findings, there has been a notable increase in the treatment rate for individuals infected within the country since 2011 [5], consistent with the recommended treatment protocols [6]. Following this, it now advocates for the timely initiation of treatment for infected individuals regardless of their immune status or viral load. This alteration is evident in a comparable distribution concerning the length of time from diagnosis to treatment, with the majority of individuals who received treatment promptly being newly diagnosed post-2015.

Results are based on medical claim data, which may either underestimate or overestimate outcomes. Evidence suggests more infected individuals than reported, attributed to anonymous reports lacking identifiable information. Over time, anonymous reports increased, surpassing reported cases. The evidence for confirming more infected individuals than reported in the surveillance infectious disease reporting data can be attributed to the lack of identifiable information, with anonymous reports increasing six-fold from 54 cases in 2003 to 642 cases in 2022. While acknowledging the possibility of duplicated anonymous reports, considering the cumulative number from 2003 to 2022 was 6,142 and comparing it with NHIS medical usage billing records, which exceeded reported data by 2,063 cases, it is reasonable to assume a higher actual number of claims.

This study is based on customized claims data from the NHIS up to 2020, and further analysis of the slight increase in the number of infected people after the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is limited by the fact that data cleaning and distribution conditions did not meet the study period. In a further study, given that the number of anonymous test subjects is steadily increasing every year, it is necessary to continue to compare the data from the KDCA notification and NHIS claims to use it as evidence to supplement relevant policies. In particular, to show the effectiveness of surveillance data, it is possible to manage infected people more effectively if we proceed in the direction of securing real-time data through inter-agency cooperation. However, it is necessary to improve awareness of HIV infection and deliver accurate information at the national level, as domestic infected persons tend to have high anxiety about social stigma depending on cultural sentiments [7,8,9,10,11,12,13], making it difficult for timely testing and management to be carried out. Moreover, the KDCA reporting materials have limitations as they do not include information on the geographic characteristics of the reporters or specifics on healthcare cost assistance, and the region of the individuals identified in the NHIS data is determined by their administrative addresses, which may not accurately reflect their living quarters. To effectively evaluate regional disparities and address this concern, it is necessary to conduct more thorough examinations and further analyses.

Based on the KDCA report, the yearly rise in individuals meeting criteria for anonymous HIV testing suggests an increasing number of people with HIV engaging in diagnostic testing, reflecting a beneficial outcome of HIV management strategies. Nevertheless, there is a lack of continuity in care or support for individuals following their anonymous testing. Although they have been promised anonymity and protection from stigma and discrimination, they are not receiving the necessary medical treatment, including adequate care. Previous research has indicated that addressing discrimination, stigma, inequality, and healthcare access, along with ensuring fundamental rights like housing and nutrition, is necessary to prevent HIV and halt the epidemic [14]. Additionally, sustained progress in HIV management models is imperative for the efficacy of these policies [15]. Delays in commencing treatment or lapses in treatment adherence and consistency attributable to stigma or health disparities may lead to outcomes such as treatment ineffectiveness [16,17]. To mitigate these challenges, it is crucial to implement a comprehensive treatment system that facilitates a seamless transition from HIV diagnosis to treatment. Indeed, the management of policies pertaining to HIV necessitates ongoing monitoring of relevant policies to align with shifting epidemiological characteristics and treatment guidelines, as well as the implementation of assessment of processes and impacts [18]. In Korea, where there are approximately 1,100 new cases of HIV each year and the growing life expectancy has resulted in an increasing number of people living with the virus, it is essential to consistently assess policy shortcomings and work towards implementing more systematic enhancements.

A viable suggestion is the development of a national HIV/AIDS management system that ensures confidentiality and includes tools for scheduling tests, managing treatments, and organizing medical records. Currently, patients must visit the specific hospitals where they typically receive treatment at their scheduled appointments. However, with this new system, individuals could access their medical records at healthcare facilities across the country, ensuring continuity of care even when treated in different locations. Moreover, infectious disease specialists in Korea are concentrated in large hospitals in major metropolitan areas, leaving those in smaller or rural cities with fewer healthcare options and less consistent care. Ensuring ongoing treatment through public health interventions at local public health centers, clinics, and hospitals is crucial to preventing new HIV infections. Results show that financial support alone is often insufficient to ensure adherence to treatment among people living with HIV. Therefore, it is essential to provide education on the importance of adhering to treatment protocols. Additionally, unverified information has been spreading widely online, making individuals vulnerable to misinformation. Providing reliable, up-to-date educational resources based on new treatment guidelines is critical. Due to societal stigma, individuals living with HIV may hesitate to disclose their condition publicly. Remote or online educational programs can offer anonymous participation, which may be more appropriate than public recruitment. Policymakers must also examine the factors behind low registration rates, particularly among women, older adults, high-income individuals, and residents of certain regions with HIV. Understanding the characteristics of undiagnosed or untreated individuals is vital to creating tailored policies for these populations.

In conclusion, deteriorated HIV management continuity is evident in those not registering but using diagnosis codes, potentially leading to increased new infections. Policy improvements are crucial to ensure continuous treatment while safeguarding the confidentiality of individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was selected as a translational study in the Korea HIV/AIDS Cohort Study and was helped by the principal investigators, Dr. Sang Il Kim (Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea), Dr. Jun Yong Choi (Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine AIDS Research Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine), and the chair of research committee Dr. Joon Young Song (Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT, Ministry of Science and ICT) (grant no. NRF-2021R1A2C2094297), the National R&D Program for Cancer Control through the National Cancer Center, funded by grant HA21C0164 from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea, and supported by research (#2022-E1901-00, #2022-ER1907-00) of Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA).

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest.

- Conceptualization: YC, BYC.

- Data curation:.

- Formal analysis: KHA, YC.

- Methodology: YC, KHA, JC, SMK, BYC, BYP.

- Writing - original draft: YC, KHA, BYP, JC, SMK, BYC, JHK, SK, YJK, YHJ.

- Writing - review & editing: YC, BYP, KHA, JC, SMK, BYC, JHK, SK, YJK, YHJ.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Definition of HIV-related disease and AIDS-defining illnesses in the National Health Insurance Service big data

Comparing the number of people living with HIV in Korea by year: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency HIV notification data and National Health Insurance Service medical claim data

Cumulative survive people living with HIV who retention on ART by the type of HIV-related healthcare utilization

Exclusion criteria of research participants.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS DATA 2023. [Accessed 21 June 2024]. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2023/2023_unaids_data.

- 2.Kim Y, Park E, Jung Y, Kim K, Kim T, Kim HS. Impact of COVID-19 on human immunodeficiency virus tests, new diagnoses, and healthcare visits in the Republic of Korea: a retrospective study from 2016 to 2021. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2024;15:340–352. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2024.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.KOSIS. KIHASA 2021. [Accessed date 21 June 2024]. https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=331&tblId=DT_33109_N058&conn_path=I2 .

- 4.KDCA. HIV/AIDS management guideline in Korea. [Accessed 21 June 2024]. Available at: https://dportal.kdca.go.kr/pot/bbs/BD_selectBbs.do?q_bbsSn=1001&q_bbsDocNo=20220311456878346&q_clsfNo=0.

- 5.The Korean Society for AIDS. Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of HIV/AIDS in HIV-infected Koreans. Infect Chemother. 2011;43:89–128. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korean Society for AIDS. Summary of 2021 clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of HIV/AIDS in HIV-infected Koreans. Infect Chemother. 2021;53:592–616. doi: 10.3947/ic.2021.0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohn A, Park S. HIV/AIDS knowledge, stigmatizing attitudes, and related behaviors and factors that affect stigmatizing attitudes against HIV/AIDS among Korean adolescents. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2012;3:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi JY. HIV Stigmatization harms individuals and public health. Infect Chemother. 2014;46:139–140. doi: 10.3947/ic.2014.46.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim IO, Shin SH. The effect of social stigma on suicidal ideation of male HIV infected people: focusing on the mediating effect of hope and depression. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2014;26:563–572. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho HW, Chu C. Discrimination and stigma. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2015;6:141–142. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HJ, Kim DH, Na YJ, Kwon MR, Yoon HJ, Lee WJ, Woo SH. Factors associated with HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination by medical professionals in Korea: a survey of infectious disease specialists in Korea. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019;22:675–681. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_440_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shim MS, Kim GS. Factors influencing young Korean men's knowledge and stigmatizing attitudes about HIV infection. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8076. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi JP, Seo BK. HIV-related stigma reduction in the era of undetectable equals untransmittable: the South Korean perspective. Infect Chemother. 2021;53:661–675. doi: 10.3947/ic.2021.0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Person AK, Armstrong WS, Evans T, Fangman JJW, Goldstein RH, Haddad M, Jain MK, Keeshin S, Tookes HE, Weddle AL, Feinberg J. Principles for ending human immunodeficiency virus as an epidemic in the United States: a policy paper of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the HIV medical association. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76:1–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallant JE, Adimora AA, Carmichael JK, Horberg M, Kitahata M, Quinlivan EB, Raper JL, Selwyn P, Williams SB nfectious Diseases Society of America; Ryan White Medical Providers Coalition. Essential components of effective HIV care: a policy paper of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Ryan White Medical Providers Coalition. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1043–1050. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Allison JJ, Giordano TP, Willig JH, Raper JL, Wray NP, Cole SR, Schumacher JE, Davies S, Saag MS. Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: do missed visits matter? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:100–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5c37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Losina E, Schackman BR, Sadownik SN, Gebo KA, Walensky RP, Chiosi JJ, Weinstein MC, Hicks PL, Aaronson WH, Moore RD, Paltiel AD, Freedberg KA. Racial and sex disparities in life expectancy losses among HIV-infected persons in the united states: impact of risk behavior, late initiation, and early discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1570–1578. doi: 10.1086/644772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verani AR, Lane J, Lim T, Kaliel D, Katz A, Palen J, Timberlake J. HIV policy advancements in PEPFAR partner countries: a review of data from 2010-2016. Glob Public Health. 2021;16:390–400. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1795219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Definition of HIV-related disease and AIDS-defining illnesses in the National Health Insurance Service big data

Comparing the number of people living with HIV in Korea by year: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency HIV notification data and National Health Insurance Service medical claim data

Cumulative survive people living with HIV who retention on ART by the type of HIV-related healthcare utilization

Exclusion criteria of research participants.