Abstract

The human bowel is exposed to numerous biotic and abiotic external noxious agents. Accordingly, the digestive tract is frequently involved in malfunctions within the organism. Together with the commensal intestinal flora, it regulates the immunological balance between inflammatory defense processes and immune tolerance. Pathological changes in this system often cause chronic inflammatory bowel diseases including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. This review article highlights the complex interaction between commensal microorganisms, the intestinal microbiome, and the intestinal epithelium-localized local immune system. The main functions of the human intestinal microbiome include (i) protection against pathogenic microbial colonization, (ii) maintenance of the barrier function of the intestinal epithelium, (iii) degradation and absorption of nutrients and (iv) active regulation of the intestinal immunity. The local intestinal immune system consists primarily of macrophages, antigen-presenting cells, and natural killer cells. These cells regulate the commensal intestinal microbiome and are in turn regulated by signaling factors of the epithelial cells and the microbiome. Deregulated immune responses play an important role and can lead to both reduced activity of the commensal microbiome and pathologically increased activity of harmful microorganisms. These aspects of chronic inflammatory bowel disease have become the focus of attention in recent years. It is therefore important to consider the immunological-microbial context in both the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. A promising holistic approach would include the most comprehensive possible diagnosis of the immune and microbiome status of the patient, both at the time of diagnostics and during therapy.

Keywords: Mucosal immunology, intestinal mucosa, inflammatory intestinal diseases, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, review

The mucosa of the human body possesses protective and transport properties and plays a central role in mucosa-localized immunity. It facilitates strictly balanced processes that maintain the equilibrium of inflammatory defense processes and immune tolerance. The specific immunity of the mucosa in the vagina, oral cavity or intestine is therefore essential for the functionality of the organs and consequently for overall organism health (1,2).

In humans, the intestinal epithelium consists of a single layer of cells. Intestinal epithelial cells act as a physical barrier, regulate intestinal homeostasis, and coordinate the interactions of intestinal flora and immune cells (3,4). In a number of physiological processes, the immune system is confronted with the major challenge of tolerating external but positive factors without allowing pathogens to become a health risk to the organism (5). In the gastrointestinal tract, the immune system’s mission is to distinguish commensal intestinal bacteria and their products from pathogenic microorganisms (6). The mutual coordination of the intestinal flora with the host immune system is the result of a long co-evolutionary adaptation (7,8). Therefore, modulation of the gut microbiota by diet, antibiotics, prebiotics, probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation represents a potentially promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of chronic inflammatory bowel disease (9).

Pathological alterations to this finely tuned system, on the other hand, often result in inflammatory diseases of the digestive tract, which often develop into chronic conditions. Common chronic inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, both of which are characterized by a dysregulated mucosal immune system. The highest incidences are found in Northern Europe and North America, but they are increasing significantly in regions with previously lower incidences (10-12).

Crohn’s disease is a segmental transmural inflammation and can manifest itself in the entire gastrointestinal tract. However, the ileocecal junction with the terminal ileum and cecum are most frequently affected (13). In contrast to Crohn’s disease, the intestinal mucosa in ulcerative colitis is continuously involved, usually starting rectally and then spreading proximally in the colon. In more severe cases, the mucosa is edematous, inflammatory reddened and bleeds after contact (13).

A confirmed diagnosis is achieved in both entities by endoscopic biopsy and is supported by comprehensive imaging procedures and chemical laboratory examinations (13,14). The course of the disease is chronic and can be accompanied by extraintestinal manifestations, such as uveitis, arthritis and erythema nodosum. Therapies depend on the severity of the disease (15). Surgical interventions play a minor role and are used in cases of severe complications including intra-abdominal abscesses, intestinal stenosis, perforation, and drug treatment failure (13,14,16-18).

The incidence of colorectal cancer is significantly increased in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (19,20). In other malignancies, central mechanisms of carcinogenesis together with specific regulators such as oncogenic signaling proteins or microRNAs often lead to malignant transformation of cells (21-23). In colorectal cancer, these mechanisms are augmented by alterations in the intestinal microbiome and correlated mucosal immunity. On the one hand, bacterial metabolic products can directly trigger tumor growth (24). On the other hand, this is associated with additional inflammatory processes in the intestinal mucosa, which also contribute to the initiation of cancer (20).

The interaction of the intestinal microbiome, the intestinal mucosal immunity and the carcinogenesis of intestinal epithelial cells has so far been underestimated. Low-grade chronic inflammation leads to the formation of cytokines and reactive oxygen species and thus to an oncogenic microenvironment that supports the transformation of cancer cells (25,26). Furthermore, the composition of the intestinal microbiome also changes during carcinogenesis. Commensal intestinal bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, Escherichia faecalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum and Streptococcus gallolyticus occur more frequently, while bacteria of the Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, Faecalibacterium and Roseburia groups decrease in colorectal cancer patients (27). This is often accompanied by an increased pro-inflammatory environment and the production of oncogenic factors, e.g., genotoxins (28,29). Initial studies have shown that changes to the gut microbiome can lead to a better response to cancer therapy. Therapy with microbial metabolites alone can also lead to a reduction in tumor volume (28). Furthermore, chemotherapy itself causes modification of the intestinal immune response. The induction of antibacterial T cell responses and the accumulation of Th1 helper cells in the tumor tissue cause antioncogenic effects in the intestine (30). As a consequence, dietary measures and the administration of antibiotics may be suitable to support colorectal cancer therapy (27,28).

Pathogenic as well as commensal microorganisms interact with the human intestinal system and thus with the entire organism in many different ways. This can alter physiological functions and even lead to pathological manifestations. The number of gastrointestinal diseases is comparatively high. In most cases, immunological and inflammatory mechanisms play a significant role; hence, the interaction between the immune system and microorganisms in the intestinal mucosa is of outstanding importance for understanding and subsequently treating such diseases.

Intestinal Microbiome

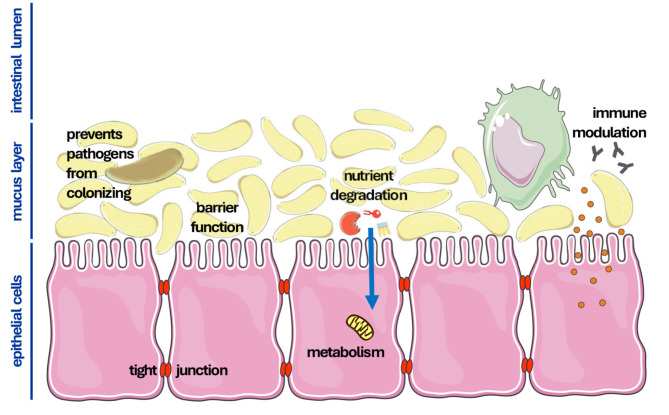

The entirety of the commensal microorganisms existing in the human bowel is referred to as the intestinal microbiome. The intestinal microbiome of a human being contains approximately 103 different microorganism species. The density of microorganisms in this colonization varies considerably. In the stomach there are about 102 microorganisms/g, in the small intestine 108 microorganisms/g, and in the large intestine even up to 1012 microorganisms/g (31). The microbiome contributes to the nutrition and metabolism of the host organism and influences the activity of the intestinal immune system (32). In humans, the fetal and originally sterile intestine is microbially colonized immediately after birth. Nutrition, hygiene, and the potential administration of medication influence the composition of the primary intestinal flora, which is predominantly composed of the phylogenetic groups Enterobacteriae and Bifidobacteriae (33). These pioneer bacteria secrete immunomodulatory factors and in turn influence the activity of the intestinal immune system, giving them a selection advantage over other potentially harmful microorganisms. This mutual adaptation leads to an individual intestinal flora, the composition of which can change continuously over the course of an individual’s life due to various influences, such as diet, stress and age (34-36). The intestinal microbiome supports intestinal function in a variety of ways, which can be divided into four areas of functionality: (i) protection against colonization by pathogens, (ii) support of the barrier function of the intestinal epithelium, (iii) absorption, production and metabolism of nutrients, and (iv) regulation of the immune system (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The intestinal epithelium is the central barrier and regulator of nutrient absorption of the gastrointestinal tract. Cells of the epithelium are tightly connected to each other by tight junctions and other cellular structures and prevent the unregulated diffusion of low-molecular compounds. Towards the intestinal lumen there is a further compartment on the intestinal epithelium, the intestinal mucus layer. This layer contains the commensal microbiome of the intestine, which fulfills important physiological intestinal functions. Commensals reduce colonization with pathogenic bacteria and form an additional diffusion barrier due to their biomass. Furthermore, the microbiome metabolizes nutrients and makes them accessible to the human organism. Commensal bacteria are also able to absorb ions and synthesize essential factors, e.g. vitamins, which are supplied to the host metabolism. Finally, commensals and epithelial cells of the intestine interact with the cells of the local intestinal immune system. These are primarily macrophages, antigen-presenting cells (APC), and natural killer cells. Epithelial cells, immune cells and commensal bacteria regulate each other and determine physiological digestion, as well as the immunological defense against exogenous pathogens.

The commensal flora adapts to the intestinal environment, making it difficult for pathogenic microorganisms to colonize the intestinal epithelium (37). Pathogens also compete for nutrients with commensals, which makes colonization even more difficult (38,39). Furthermore, the intestinal flora produces antimicrobial peptides (40,41) as well as lactate, which originates from anaerobic metabolism and also exhibits growth-inhibiting properties (42). One treatment option for chronic inflammatory bowel disease and in particular for maintaining remission, especially in patients with ulcerative colitis, could be the administration of probiotics (43). These are generally non-pathogenic lactate-producing bacteria that have an inhibitory effect on microbial growth (44,45).

The barrier function of the intestinal epithelium is primarily ensured by the cell-cell contacts of the epithelial cells, the tight junctions. These are formed from various membrane-bound proteins including claudin and occludin and close the intracellular space between two epithelial cells. This diffusion barrier directs the uptake of low molecular weight substances across the epithelial cells. The regulation of tight junction composition and functionality is regulated by cytokines and chemokines, some of which are also provided by the intestinal flora (40,46). While nutrients are absorbed by the epithelial cells, microorganisms cannot pass through the epithelial layer and remain on the luminal side of the intestine (47). The commensal intestinal bacteria colonize the mucosa of the intestinal epithelium and thus form a further physical barrier. Furthermore, they secrete signaling molecules that are taken up by the epithelial cells and activate intracellular signaling cascades, leading to improved intestinal barrier function (48). Under pathological, particularly inflammatory conditions, soluble factors such as chemokines and cytokines can also influence the permeability of the intestinal wall (49). However, so-called adherent invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) strains can adhere to the epithelium and sometimes even migrate into it (50). The administration of antibiotics to reduce the total bacterial load or to specifically eliminate pathogenic bacteria is therefore a therapeutic option to alleviate inflammatory bowel diseases (44,51).

The absorption of low-molecular substances, on the other hand, is promoted by the intestinal flora. Microbial hormones stimulate the epithelial cells to adsorb nutrients (40). Food components that are indigestible for humans are only made accessible for adsorption through microbial metabolism in the gut (52-54). Intestinal bacteria degrade indigestible carbohydrates to acetate, propionate and butyrate, which epithelial cells can use for energy production (55,56). Intestinal bacteria are also involved in the conversion of drugs and drug precursors (57,58).

Intestinal Immune System

The mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract is in constant contact with the microbial antigens of the intestinal flora, but also with antigens from food. Mucosal immunity therefore plays a significant role in the defense against diseases. This concerns both innate and adaptive immunity and takes place both locally in the intestine and systemically in the entire organism.

Immune cells constantly interact with the antigens of the intestinal lumen and differentiate into symbionts and pathogens (59). Macrophages, antigen-presenting cells (APC) and natural killer cells play an essential role here (60-63). The differentiation and activation of immune cells also depends on the intestinal flora, for example through antimicrobial secreted interleukins (40). In germ-free laboratory animals, the absence of intestinal flora leads to lower cytokine and immunoglobulin levels and fewer epithelial-associated lymphocytes (42). However, the resulting reduced intestinal immunity can be restored by recolonization with intestinal bacteria (52). Symbiotic factors control the development of mucosal immunity (64-67), in particular the humoral components of the intestinal mucosal immune system (68). The composition and fine-tuning of T cells and T helper cells are also modulated by the intestinal flora (53,69). In the intestinal mucosa, bacterial antigens are identified by the factors toll-like receptor (TLR) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 (NOD2) (36,70,71). Other epithelial factors, such as multidrug resistance 1 (MDR1), Drosophila discs large homologue 5 (DLG5), and organic cation transporters (OCTN) have also been identified as immunomodulators (72-74).

Disregulation of the involved immune cells plays an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Various mucosal and epithelial immune cells lead to tissue damage as part of the adaptive immune response (60). In Crohn’s disease, type 1 T helper cells (Th1) dominate the immune response, resulting in the release of interferon γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrofactor (TNF), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-2, and IL-12. Ulcerative colitis correlates with a Th2 immune response and leads to the release of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 (62,75). However, other immune cells such as Th17 cells and regulatory T cells (Treg) are also involved in the inflammatory processes, which lead to the secretion of other inflammatory factors [transforming growth factor- β (TGF-β), IL-10, IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23, IL-26] (60,75,76).

The cells of the mucosal immune system not only ward off pathogens, but also control and regulate the symbiotic organisms of the intestinal flora. Depending on the colonized bacterial strains, more Th17 or more Treg cells are produced (77). If the ratio of the two T cell populations shifts too much, Th cells increasingly express specific T cell receptors (TCR) to bind symbiotic bacteria and stimulate a pro-inflammatory immune response (78). However, the inflammatory reaction remains within physiological limits, for example due to a reduced expression of bacteria-specific TLR and NOD2 in the epithelial cells. In this scenario, the composition of the symbiotic part of the intestinal flora can be kept largely constant (79).

The immune response is different in the case of inadequate contact with pathogenic microorganisms. These stimulate a significantly stronger inflammatory reaction, including the release of a large number of inflammatory mediators (80). One consequence of such significant inflammatory reactions can be a shift in the microbial spectrum of the intestine. Species that were previously prevented from growing by the symbiotic bacterial community can now proliferate. There is often a shift from anaerobic to facultative anaerobic strains (81). This quantitative and qualitative transformation of the intestinal flora is generally accompanied by changes in functionality and leads to various diseases, including chronic inflammatory diseases of the intestine (82). A similar situation arises when the composition of the intestinal flora is altered as part of antibiotic therapy (83,84). Eradication of symbiotic bacteria can cause previously inhibited pathogens such as Clostridioides difficile (until 2016 Clostridium difficile) to proliferate and, depending on the severity of the disease and predisposing factors, can lead to diarrhea, ileus, pseudomembranous colitis (PMC), toxic megacolon, intestinal perforations or sepsis (85).

Summary and Conclusion

The human body is dependent on commensal organisms. This interaction of the digestive system with endosymbiotic microorganisms has been optimized over the course of evolution. The human host benefits from the microbial support of the digestive process. In some cases, mammals are even essentially dependent on factors and precursors of microbial origin. Vice versa, organisms of the intestinal microbiome utilize the nutrient availability of the host organism and have survival advantages over foreign, potentially pathogenic microorganisms in the digestive tract habitat due to the symbiotic interaction of host and commensals.

The local immune system of the intestine is essential in the interaction between intestinal cells, immune cells, and commensal microorganisms. Immune cells are activated by intestinal bacterial substances and soluble factors of epithelial origin. In parallel, immunomodulatory factors and immune cells determine the composition and thus the functionality of the intestinal microbiome. This is particularly important in a clinical context, as this complex regulatory network influences not only physiological but also pathological mechanisms. On the one hand, deregulation of these gastrointestinal control mechanisms may be the cause of the disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are often caused by pathological changes in the immune-controlled intestinal host-microbiome system. Such conditions can then also correlate with subsequent infections and even the development of colorectal cancer. Solid tumors are always accompanied by non-physiological inflammatory processes. On the other hand, such pathological conditions can also be triggered by medical intervention itself. Systemic antimicrobial treatment, for example, can potentially harm commensal microorganisms and thereby promote pathogens. The consequences would affect almost the entire balanced network of intestinal (protective) functions. Other drugs, e.g., chemotherapeutics, may also affect intestinal microbiome and the finely tuned system of intestinal functionality.

These aspects of inflammatory bowel disease have only been brought into focus in recent years and are therefore not yet understood in detail for the most part. Subject to the need for further research, however, a key point for everyday clinical practice can already be derived from this. The immunological-microbial context should be taken into account in both the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. This provides additional conclusions about the causes of pathological conditions. However, the fact that therapeutic modulation of the microbiome and the local immune system can indirectly support inflammatory bowel disease therapy appears to be much more important at present. The same is also becoming apparent in the treatment of bowel cancer. The prerequisite for such a promising holistic approach is the most precise possible diagnosis of the immune and microbial status of the patient, which should be done both during diagnosis and treatment.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: AH and MBS; writing original draft: AH and MBS; original draft review and editing: AH, AB and MBS.

References

- 1.Ding G, Yang X, Li Y, Wang Y, Du Y, Wang M, Ye R, Wang J, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Zhang Y. Gut microbiota regulates gut homeostasis, mucosal immunity and influences immune-related diseases. Mol Cell Biochem. 2024 doi: 10.1007/s11010-024-05077-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balakrishnan SN, Yamang H, Lorenz MC, Chew SY, Than LTL. Role of vaginal mucosa, host immunity and microbiota in vulvovaginal candidiasis. Pathogens. 2022;11(6):618. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11060618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolev HM, Kaestner KH. Mammalian Intestinal development and differentiation-the state of the art. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;16(5):809–821. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2023.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Q, Lu Q, Jia S, Zhao M. Gut immune microenvironment and autoimmunity. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;124:110842. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stope MB, Mustea A, Sänger N, Einenkel R. Immune cell functionality during decidualization and potential clinical application. Life (Basel) 2023;13(5):1097. doi: 10.3390/life13051097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iebba V, Totino V, Gagliardi A, Santangelo F, Cacciotti F, Trancassini M, Mancini C, Cicerone C, Corazziari E, Pantanella F, Schippa S. Eubiosis and dysbiosis: the two sides of the microbiota. New Microbiol. 2016;39:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayres JS. Cooperative microbial tolerance behaviors in host-microbiota mutualism. Cell. 2016;165(6):1323–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies CS, Worsley SF, Maher KH, Komdeur J, Burke T, Dugdale HL, Richardson DS. Immunogenetic variation shapes the gut microbiome in a natural vertebrate population. Microbiome. 2022;10(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01233-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McIlroy J, Ianiro G, Mukhopadhya I, Hansen R, Hold GL. Review article: the gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease—avenues for microbial management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(1):26–42. doi: 10.1111/apt.14384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts SE, Thorne K, Thapar N, Broekaert I, Benninga MA, Dolinsek J, Mas E, Miele E, Orel R, Pienar C, Ribes-Koninckx C, Thomson M, Tzivinikos C, Morrison-Rees S, John A, Williams JG. A systematic review and meta-analysis of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease incidence and prevalence across Europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(8):1119–1148. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh K, Xiao SD. Inflammatory bowel disease: A survey of the epidemiology in Asia. J Dig Dis. 2009;10(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2008.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin D, Jin Y, Shao X, Xu Y, Ma G, Jiang Y, Xu Y, Jiang Y, Hu D. Global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease, 1990-2021: Insights from the global burden of disease 2021. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2024;39(1):139. doi: 10.1007/s00384-024-04711-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel CA, Sharma D, Griffith J, Doan Q, Xuan S, Malter L. Treatment pathways in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: understanding the road to advanced therapy. Crohns Colitis 360. 2024;6(3):otae040. doi: 10.1093/crocol/otae040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann JC, Autschbach F, Bokemeyer B, Buhr HJ, Herrlinger K, Höhne W, Krieglstein C, Kruis W, Moser G, Preiss JC, Reinshagen M, Rogler G, Schreiber S, Schreyer AG, Siegmund B, Stallmach A, Stange EF, Zeitz M. [Short version of the updated German S3 (level 3) guideline on diagnosis and treatment of Crohn’s disease] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:1924–1929. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wangchuk P, Yeshi K, Loukas A. Ulcerative colitis: clinical biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and emerging treatments. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2024;45(10):892–903. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2024.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henniger G, Galli R, Rosenberg R. [Modern surgery for inflammatory bowel disease] Ther Umsch. 2023;80:417–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suárez Ferrer C, Martín-Arranz MD, Martín-Arranz E, Rodríguez Morata F, López García A, Benítez Cantero JM, Mesonero Gismero F, Barreiro-de Acosta M. Current management of bowel failure due to Crohn’s disease in Spain: results of a GETECCU survey. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;46(6):439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2022.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adamina M, Bonovas S, Raine T, Spinelli A, Warusavitarne J, Armuzzi A, Bachmann O, Bager P, Biancone L, Bokemeyer B, Bossuyt P, Burisch J, Collins P, Doherty G, El-Hussuna A, Ellul P, Fiorino G, Frei-Lanter C, Furfaro F, Gingert C, Gionchetti P, Gisbert JP, Gomollon F, González Lorenzo M, Gordon H, Hlavaty T, Juillerat P, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Krustins E, Kucharzik T, Lytras T, Maaser C, Magro F, Marshall JK, Myrelid P, Pellino G, Rosa I, Sabino J, Savarino E, Stassen L, Torres J, Uzzan M, Vavricka S, Verstockt B, Zmora O. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: surgical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(2):155–168. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fanizza J, Bencardino S, Allocca M, Furfaro F, Zilli A, Parigi TL, Fiorino G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S, D'Amico F. Inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16(17):2934. doi: 10.3390/cancers16172943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faggiani I, D'Amico F, Furfaro F, Zilli A, Parigi TL, Cicerone C, Fiorino G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S, Allocca M. Small bowel cancer in Crohn’s disease. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16(16):2901. doi: 10.3390/cancers16162901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanahan D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(1):31–46. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stope MB, Koensgen D, Burchardt M, Concin N, Zygmunt M, Mustea A. Jump in the fire — heat shock proteins and their impact on ovarian cancer therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;97:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss M, Brandenburg LO, Burchardt M, Stope MB. MicroRNA-1 properties in cancer regulatory networks and tumor biology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;104:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shatova OP, Zabolotneva AA, Shestopalov AV. Molecular ensembles of microbiotic metabolites in carcinogenesis. Biochem (Mosc) 2023;88(7):867–879. doi: 10.1134/S0006297923070027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuzma J, Chmelař D, Hájek M, Lochmanová A, Čižnár I, Rozložník M, Klugar M. The role of intestinal microbiota in the pathogenesis of colorectal carcinoma. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2020;65(1):17–24. doi: 10.1007/s12223-019-00706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koustas E, Trifylli EM, Sarantis P, Papadopoulos N, Aloizos G, Tsagarakis A, Damaskos C, Garmpis N, Garmpi A, Papavassiliou AG, Karamouzis MV. Implication of gut microbiome in immunotherapy for colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;14(9):1665–1674. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v14.i9.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chattopadhyay I, Dhar R, Pethusamy K, Seethy A, Srivastava T, Sah R, Sharma J, Karmakar S. Exploring the role of gut microbiome in colon cancer. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2021;193(6):1780–1799. doi: 10.1007/s12010-021-03498-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zitvogel L, Daillère R, Roberti MP, Routy B, Kroemer G. Anticancer effects of the microbiome and its products. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(8):465–478. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yadav D, Sainatham C, Filippov E, Kanagala SG, Ishaq SM, Jayakrishnan T. Gut microbiome-colorectal cancer relationship. Microorganisms. 2024;12(3):484. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12030484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viaud S, Daillère R, Boneca IG, Lepage P, Langella P, Chamaillard M, Pittet MJ, Ghiringhelli F, Trinchieri G, Goldszmid R, Zitvogel L. Gut microbiome and anticancer immune response: really hot Sh*t! Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(2):199–214. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ball D, Athanasiadou S. Conference report: the importance of the gut microbiome and nutrition on health. Gut Microbiome (Camb) 2021;2:e4. doi: 10.1017/gmb.2021.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Thomas JP, Korcsmaros T, Gul L. Integrating multi-omics to unravel host-microbiome interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5(9):101738. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabo CM, Dumitrascu DL. Microbiota and the irritable bowel syndrome. Minerva Gastroenterol (Torino) 2022;67(4):377–384. doi: 10.23736/S2724-5985.21.02923-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lockyer S, Aguirre M, Durrant L, Pot B, Suzuki K. The role of probiotics on the roadmap to a healthy microbiota: a symposium report. Gut Microbiome (Camb) 2020;1:e2. doi: 10.1017/gmb.2020.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romano K, Shah AN, Schumacher A, Zasowski C, Zhang T, Bradley-Ridout G, Merriman K, Parkinson J, Szatmari P, Campisi SC, Korczak DJ. The gut microbiome in children with mood, anxiety, and neurodevelopmental disorders: An umbrella review. Gut Microbiome (Camb) 2023;4:e18. doi: 10.1017/gmb.2023.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White Z, Cabrera I, Kapustka I, Sano T. Microbiota as key factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1155388. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1155388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leatham MP, Banerjee S, Autieri SM, Mercado-Lubo R, Conway T, Cohen PS. Precolonized human commensal Escherichia coli strains serve as a barrier to E. coli O157:H7 growth in the streptomycin-treated mouse intestine. Infect Immun. 2009;77(7):2876–2886. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00059-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Momose Y, Hirayama K, Itoh K. Competition for proline between indigenous Escherichia coli and E. coli O157:H7 in gnotobiotic mice associated with infant intestinal microbiota and its contribution to the colonization resistance against E. coli O157:H7. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2008;94(2):165–171. doi: 10.1007/s10482-008-9222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Momose Y, Hirayama K, Itoh K. Effect of organic acids on inhibition of Escherichia coli O157:H7 colonization in gnotobiotic mice associated with infant intestinal microbiota. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2008;93(1-2):141–149. doi: 10.1007/s10482-007-9188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morici LA, McLachlan JB. Non-mucosal vaccination strategies to enhance mucosal immunity. Vaccine Insights. 2023;2(6):229–236. doi: 10.18609/vac.2023.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsai CJY, Loh JMS, Fujihashi K, Kiyono H. Mucosal vaccination: onward and upward. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2023;22(1):885–899. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2023.2268724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Hara AM, Shanahan F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(7):688–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glassner KL, Abraham BP, Quigley EM. The microbiome and inflammatory bowel disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bajaj A, Markandey M, Kedia S, Ahuja V. Gut bacteriome in inflammatory bowel disease: An update on recent advances. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2024;43(1):103–111. doi: 10.1007/s12664-024-01541-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun S, Xu X, Liang L, Wang X, Bai X, Zhu L, He Q, Liang H, Xin X, Wang L, Lou C, Cao X, Chen X, Li B, Wang B, Zhao J. Lactic acid-producing probiotic Saccharomyces cerevisiae attenuates ulcerative colitis via suppressing macrophage pyroptosis and modulating gut microbiota. Front Immunol. 2021;12:777665. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.777665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matter K, Balda MS. Epithelial tight junctions, gene expression and nucleo-junctional interplay. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(9):1505–1511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.005975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang K, Hornef MW, Dupont A. The intestinal epithelium as guardian of gut barrier integrity. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17(11):1561–1569. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ulluwishewa D, Anderson RC, McNabb WC, Moughan PJ, Wells JM, Roy NC. Regulation of tight junction permeability by intestinal bacteria and dietary components. J Nutr. 2011;141(5):769–776. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.135657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Camara-Lemarroy CR, Metz L, Meddings JB, Sharkey KA, Wee Yong V. The intestinal barrier in multiple sclerosis: implications for pathophysiology and therapeutics. Brain. 2018;141(7):1900–1916. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sivignon A, Chervy M, Chevarin C, Ragot E, Billard E, Denizot J, Barnich N. An adherent-invasive Escherichia coli-colonized mouse model to evaluate microbiota-targeting strategies in Crohn’s disease. Dis Model Mech. 2022;15(10):dmm049707. doi: 10.1242/dmm.049707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simon N, Moledina Z, Simpson R, Kirby L. Metronidazole for the treatment of cutaneous vulval Crohn disease: A systematic review. Skin Health Dis. 2023;3(3):e210. doi: 10.1002/ski2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ivanov II, Honda K. Intestinal commensal microbes as immune modulators. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(4):496–508. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shanahan F. The host-microbe interface within the gut. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16(6):915–931. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee JS, Wang RX, Alexeev EE, Colgan SP. Intestinal inflammation as a dysbiosis of energy procurement: new insights into an old topic. Gut Microbes. 2021;13(1):1–20. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1880241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Louis P, Duncan SH, Sheridan PO, Walker AW, Flint HJ. Microbial lactate utilisation and the stability of the gut microbiome. Gut Microbiome (Camb) 2022;3:e3. doi: 10.1017/gmb.2022.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimura I, Ichimura A, Ohue-Kitano R, Igarashi M. Free fatty acid receptors in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2020;100(1):171–210. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geller LT, Barzily-Rokni M, Danino T, Jonas OH, Shental N, Nejman D, Gavert N, Zwang Y, Cooper ZA, Shee K, Thaiss CA, Reuben A, Livny J, Avraham R, Frederick DT, Ligorio M, Chatman K, Johnston SE, Mosher CM, Brandis A, Fuks G, Gurbatri C, Gopalakrishnan V, Kim M, Hurd MW, Katz M, Fleming J, Maitra A, Smith DA, Skalak M, Bu J, Michaud M, Trauger SA, Barshack I, Golan T, Sandbank J, Flaherty KT, Mandinova A, Garrett WS, Thayer SP, Ferrone CR, Huttenhower C, Bhatia SN, Gevers D, Wargo JA, Golub TR, Straussman R. Potential role of intratumor bacteria in mediating tumor resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine. Science. 2017;357(6356):1156–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yue B, Gao R, Wang Z, Dou W. Microbiota-host-irinotecan axis: a new insight toward irinotecan chemotherapy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:710945. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.710945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elson CO, Cong Y, McCracken VJ, Dimmitt RA, Lorenz RG, Weaver CT. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease reveal innate, adaptive, and regulatory mechanisms of host dialogue with the microbiota. Immunol Rev. 2005;206(1):260–276. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Estevinho MM, Leão Moreira P, Silva I, Laranjeira Correia J, Santiago M, Magro F. A scoping review on early inflammatory bowel disease: definitions, pathogenesis, and impact on clinical outcomes. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221142673. doi: 10.1177/17562848221142673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramadan YN, Kamel AM, Medhat MA, Hetta HF. MicroRNA signatures in the pathogenesis and therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Med. 2024;24(1):217. doi: 10.1007/s10238-024-01476-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cannarozzi AL, Latiano A, Massimino L, Bossa F, Giuliani F, Riva M, Ungaro F, Guerra M, Brina ALD, Biscaglia G, Tavano F, Carparelli S, Fiorino G, Danese S, Perri F, Palmieri O. Inflammatory bowel disease genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metagenomics meet artificial intelligence. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Nimmo ER, Ho GT, Arnott ID, Wilson DC, Satsangi J. Genetics of the innate immune response in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(3):338–355. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garfias-López JA, Castro-Escarpuli G, Cárdenas PE, Moreno-Altamirano MMB, Padierna-Olivos J, Sánchez-García FJ. Immunization with intestinal microbiota-derived Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli reduces bacteria-specific recolonization of the intestinal tract. Immunol Lett. 2018;196:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weber JI, Rodrigues AV, Valério-Bolas A, Nunes T, Carvalheiro M, Antunes W, Alexandre-Pires G, da Fonseca IP, Santos-Gomes G. Insights on host-parasite immunomodulation mediated by extracellular vesicles of cutaneous Leishmania shawi and Leishmania guyanensis. Cells. 2023;12(8):1101. doi: 10.3390/cells12081101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krenzlin V, Schöche J, Walachowski S, Reinhardt C, Radsak MP, Bosmann M. Immunomodulation of neutrophil granulocyte functions by bacterial polyphosphates. Eur J Immunol. 2023;53(5):e2250339. doi: 10.1002/eji.202250339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen LW, Chen PH, Hsu CM. Commensal microflora contribute to host defense against escherichia coli pneumonia through toll-like receptors. Shock. 2011;36(1):67–75. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182184ee7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiong N, Hu S. Regulation of intestinal IgA responses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(14):2645–2655. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1892-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shi N, Li N, Duan X, Niu H. Interaction between the gut microbiome and mucosal immune system. Mil Med Res. 2017;4:14. doi: 10.1186/s40779-017-0122-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cario E, Podolsky DK. Differential alteration in intestinal epithelial cell expression of toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and TLR4 in inflammatory bowel disease. Infect Immun. 2000;68(12):7010–7017. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.12.7010-7017.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.El Hadad J, Schreiner P, Vavricka SR, Greuter T. The genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Diagn Ther. 2024;28(1):27–35. doi: 10.1007/s40291-023-00678-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Annese V, Valvano MR, Palmieri O, Latiano A, Bossa F, Andriulli A. Multidrug resistance 1 gene in inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(23):3636–3644. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i23.3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stoll M, Corneliussen B, Costello CM, Waetzig GH, Mellgard B, Koch WA, Rosenstiel P, Albrecht M, Croucher PJP, Seegert D, Nikolaus S, Hampe J, Lengauer T, Pierrou S, Foelsch UR, Mathew CG, Lagerstrom-Fermer M, Schreiber S. Genetic variation in DLG5 is associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36(5):476–480. doi: 10.1038/ng1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reinhard C, Rioux JD. Role of the IBD5 susceptibility locus in the inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(3):227–238. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000202413.16360.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Du L, Ha C. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(4):643–654. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):417–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441(7090):235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):845–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kos M, Bojarski K, Mertowska P, Mertowski S, Tomaka P, Dziki Ł, Grywalska E. New horizons in the diagnosis of gastric cancer: the importance of selected toll-like receptors in immunopathogenesis depending on the stage, clinical subtype, and gender of newly diagnosed patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(17):9264. doi: 10.3390/ijms25179264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haller D. Intestinal epithelial cell signalling and host-derived negative regulators under chronic inflammation: to be or not to be activated determines the balance towards commensal bacteria. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(3):184–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Winter SE, Winter MG, Xavier MN, Thiennimitr P, Poon V, Keestra AM, Laughlin RC, Gomez G, Wu J, Lawhon SD, Popova IE, Parikh SJ, Adams LG, Tsolis RM, Stewart VJ, Bäumler AJ. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science. 2013;339(6120):708–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1232467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kranich J, Maslowski KM, Mackay CR. Commensal flora and the regulation of inflammatory and autoimmune responses. Semin Immunol. 2011;23(2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, Kelly CP. Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile and serum levels of IgG antibody against toxin A. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(6):390–397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McFarland LV. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea: epidemiology, trends and treatment. Future Microbiol. 2008;3(5):563–578. doi: 10.2217/17460913.3.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pépin J, Valiquette L, Cossette B. Mortality attributable to nosocomial Clostridium difficile-associated disease during an epidemic caused by a hypervirulent strain in Quebec. CMAJ. 2005;173(9):1037–1042. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]