Abstract

Background/Aim

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) belongs to the perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) family. The relationship between LAM and tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is of particular concern in a subset of women with clinically occult LAM involving the pelvic lymph nodes. This study aimed to investigate the clinicopathological features of incidental nodal LAM detected during the surgical staging of gynecological tumors.

Patients and Methods

During the study period of 10 years, we identified 17 patients with pelvic nodal LAM that was incidentally detected during surgery for gynecological neoplastic lesions. We conducted immunostaining to assess the diagnostic utility of a panel of PEComa markers.

Results

Two of the 17 patients (11.8%) were diagnosed with TSC before surgery without any pulmonary symptoms. During the follow-up, both patients developed pulmonary and extrapulmonary LAMs. All affected nodes were multiple and unilateral in the pelvic region. The mean nodal size was 5.4 mm, and the mean proportion of the area involved in the LAM was 34.1%. In two patients with TSC, the largest affected node measured 19.3 mm and 7.6 mm, respectively, and the proportion of the area replaced by LAM was 99% and 90%, respectively. The most frequently expressed markers were human melanoma black 45 and cathepsin K, which showed 100% positivity in all the examined cases.

Conclusion

While most small nodal LAMs incidentally discovered during surgery have insignificant prognostic value, larger nodal LAMs occupying most of the nodal parenchyma at reproductive age should raise awareness of pulmonary and extrapulmonary LAMs as well as TSC.

Keywords: Lymph node, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, cervical carcinoma, endometrial carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a member of the family of lesions known collectively as perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) (1,2). Other members of this family include angiomyolipoma (AML), transcription factor E3 (TFE3) translocation-associated PEComa, and clear cell myelocytic tumors. LAM cells consistently express melanogenesis-related markers and smooth muscle markers, which are commonly observed in PEComas (1). Conventional and TFE3 translocation-associated PEComas arise in various organ systems, whereas LAM is restricted to specific anatomical locations (3-5). LAM most commonly affects the lungs, where it behaves as a low-grade but destructive disease, leading to progressive respiratory failure (6). Additionally, LAM can be found in the lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes of the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, and pelvic cavity (7). The clinical manifestations, behavior, and histological features of extrapulmonary LAM differ from those of pulmonary LAM, despite the similar immunophenotype of LAM cells (8).

Extrapulmonary LAM may be associated with PEComa family tumors or various manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). Notably, it remains unclear whether all patients with extrapulmonary LAM also have pulmonary LAM or are at risk of developing it. Therefore, the potential relationship between LAM and TSC is of particular concern in a unique subset of women with clinically occult LAM involving the pelvic lymph nodes, which is detected incidentally during the surgical staging of uterine and ovarian malignancies. In this study, to better understand the clinical behavior of nodal LAM, we investigated the clinicopathological characteristics of incidental pelvic nodal LAM detected during the surgical staging of gynecological neoplastic lesions. Additionally, we performed immunostaining for a panel of markers commonly employed in diagnosing PEComas to assess their utility in nodal LAM.

Patients and Methods

Case selection and data collection. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (protocol number: 2024-07-028; approval date: July 11, 2024). We searched institutional databases for cases matching the keywords “lymphangioleiomyoma” and “lymphangioleiomyomatosis” that occurred between January 2013 and December 2022. We identified 44 consecutive patients with LAM involving various organs. Two board-certified pathologists specializing in gynecological oncology (Y.L. and H.S.K.) thoroughly reviewed all available hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides to confirm the pathological diagnosis of LAM, collect pathological information, and assess the presence of sufficient lesional tissue for immunohistochemical staining. Seventeen of the 44 cases were confirmed as pelvic nodal LAM incidentally detected during surgical staging for gynecological malignancies and premalignant lesions, while 27 cases of LAM arising in the lungs (18 cases), retroperitoneum (three cases), pancreas (two cases), stomach (two cases), supraclavicular lymph node (one case), and recurrent laryngeal nerve lymph node (one case) were excluded from this study. The following clinical information was obtained from electronic medical records: patient age at the time of diagnosis; clinical history of TSC, pulmonary LAM, and extrapulmonary LAM; primary indication for surgical staging and procedure; current status and survival data; and postoperative follow-up duration. The following pathological data were also collected: number of sampled and affected nodes, laterality, location, and size of affected nodes; percentage of microscopic area replaced by LAM; microanatomical topography of LAM; concurrent nodal lesions; and concurrent uterine lesions.

Immunostaining. Immunostaining was performed using a Bond-max automated immunostainer (Leica Biosystems, Deer Park, IL, USA) and Bond Polymer Refine Detection (Leica Biosystems) (9-25). Briefly, 4-μm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated using a graded alcohol series. After antigen retrieval, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies against human melanoma black 45 (HMB45; dilution, 1:80; clone, HMB45; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), melan A (dilution, 1:80; clone, A108; Agilent Technologies), cathepsin K (dilution, 1:500; clone, EPR19992; Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA), microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MiTF; prediluted; clone, 34CA5; Biocare Medical, Pacheco, CA, USA), desmin (dilution, 1:200; clone, D33; Agilent Technologies), estrogen receptor (ER; dilution, 1:200; clone, 6F11; Leica Biosystems), progesterone receptor (PR; dilution, 1:1,800; clone, 16; Leica Biosystems), and D2-40 (dilution, 1:100; clone, D2-40; Agilent Technologies). After chromogenic visualization, slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted. Positive and negative controls were stained concurrently. Positive controls included cutaneous nodular malignant melanoma for HMB45, melan A, cathepsin K, and MiTF; uterine leiomyoma for desmin; luminal A-type invasive breast carcinoma for ER and PR; and peritoneal epithelioid malignant mesothelioma for D2-40. Negative controls were prepared by substituting non-immune serum for the primary antibodies, resulting in undetectable staining. Each immunostained slide was scored by two board-certified pathologists. Staining intensities for all examined proteins were designated as negative, weak, moderate, or strong, and staining proportions were determined in 5% increments across a 0%-100% range and classified as focal (<50%) or diffuse (≥50%).

Results

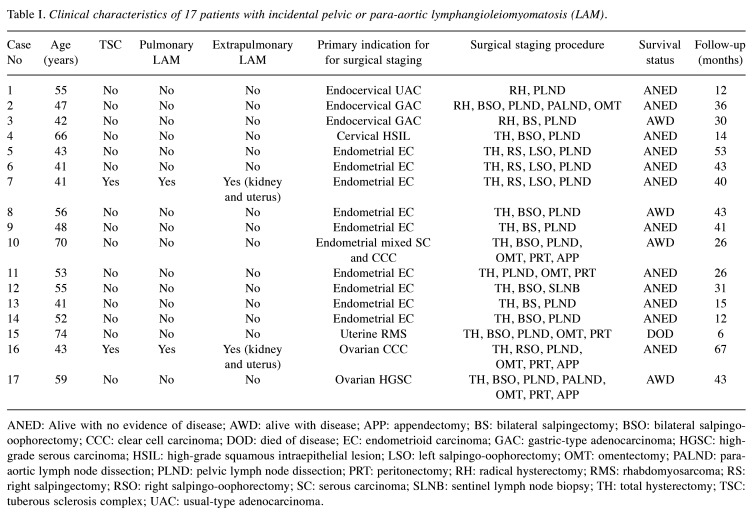

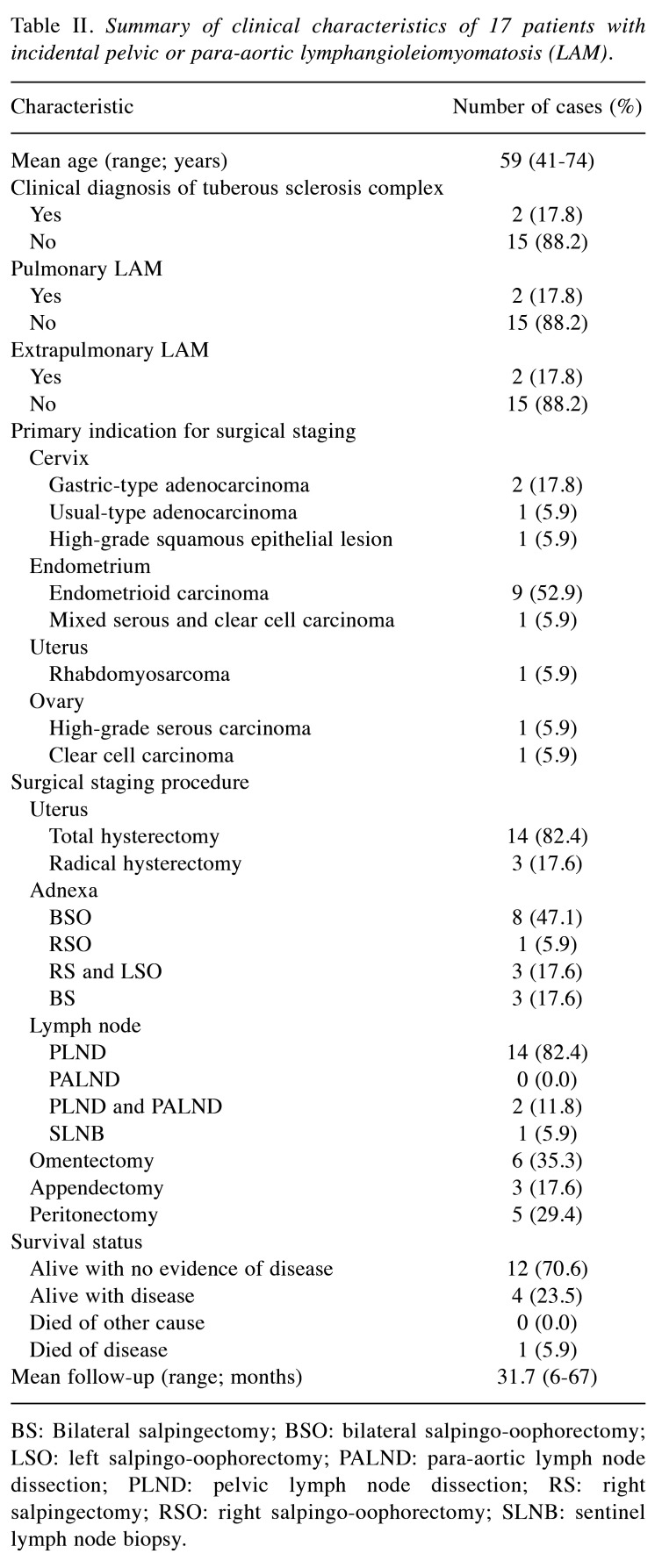

Clinical features. We identified 17 patients with pelvic nodal LAM that was incidentally discovered during surgical staging of gynecological malignancies. Table I presents the detailed clinical characteristics of the patients. The mean patient age was 52.1 years (range=41-74 years). Two of the 17 patients (11.8%; cases 7 and 16) had been diagnosed with TSC prior to undergoing gynecological surgery. None of the patients presented respiratory signs or symptoms related to pulmonary LAM at the time of diagnosis. However, during the follow-up period, these two patients developed both pulmonary and extrapulmonary LAM affecting the uterus and kidneys. Regarding the primary indications for surgical staging, 10 patients (58.8%) underwent total hysterectomy for endometrial carcinoma, and radical hysterectomy was performed in three patients with endocervical adenocarcinoma (17.6%). Additionally, two patients (11.8%) underwent surgical staging for ovarian carcinoma, and one patient (5.9%) for uterine rhabdomyosarcoma. Endometrioid carcinoma was the most common histological type (9/17, 52.1%). Other recorded types included two cases of human papillomavirus-independent gastric-type endocervical adenocarcinoma, one case of mixed serous and clear cell endometrial carcinoma, and one case of uterine rhabdomyosarcoma. Bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection was performed in all but one patient, who underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy. Postoperative follow-up information was available for all patients, with a mean follow-up period of 31.7 months (range=6-67 months). One patient (case 15), who died of uterine rhabdomyosarcoma six months after surgery, was the only mortality recorded during the follow-up period. The remaining 16 patients were followed up for more than a year and are currently alive. Twelve of these patients have shown no evidence of recurrent disease, while four experienced persistent systemic metastases. Table II summarizes the clinical features of these 17 patients.

Table I. Clinical characteristics of 17 patients with incidental pelvic or para-aortic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM).

ANED: Alive with no evidence of disease; AWD: alive with disease; APP: appendectomy; BS: bilateral salpingectomy; BSO: bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; CCC: clear cell carcinoma; DOD: died of disease; EC: endometrioid carcinoma; GAC: gastric-type adenocarcinoma; HGSC: high-grade serous carcinoma; HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; LSO: left salpingo-oophorectomy; OMT: omentectomy; PALND: para-aortic lymph node dissection; PLND: pelvic lymph node dissection; PRT: peritonectomy; RH: radical hysterectomy; RMS: rhabdomyosarcoma; RS: right salpingectomy; RSO: right salpingo-oophorectomy; SC: serous carcinoma; SLNB: sentinel lymph node biopsy; TH: total hysterectomy; TSC: tuberous sclerosis complex; UAC: usual-type adenocarcinoma.

Table II. Summary of clinical characteristics of 17 patients with incidental pelvic or para-aortic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM).

BS: Bilateral salpingectomy; BSO: bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; LSO: left salpingo-oophorectomy; PALND: para-aortic lymph node dissection; PLND: pelvic lymph node dissection; RS: right salpingectomy; RSO: right salpingo-oophorectomy; SLNB: sentinel lymph node biopsy.

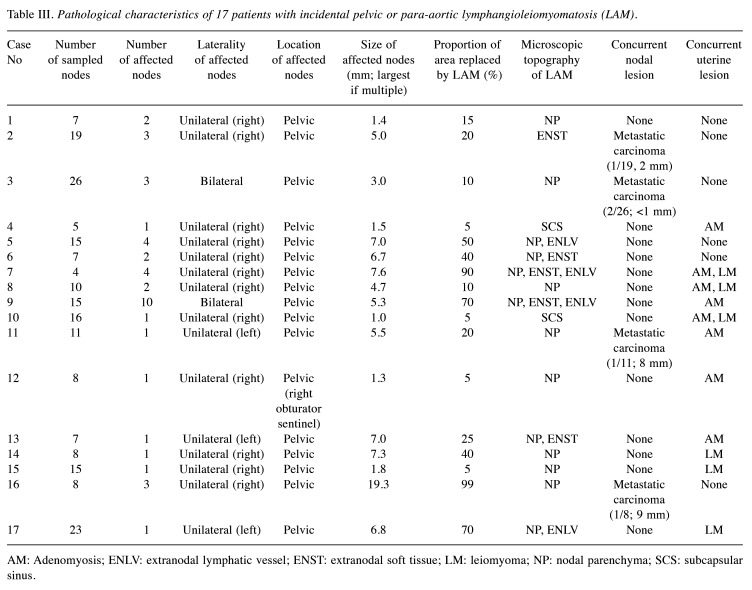

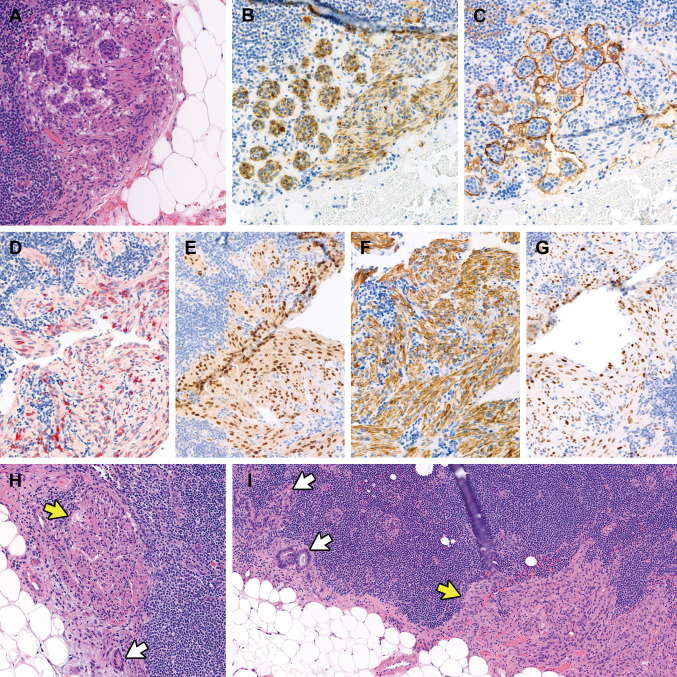

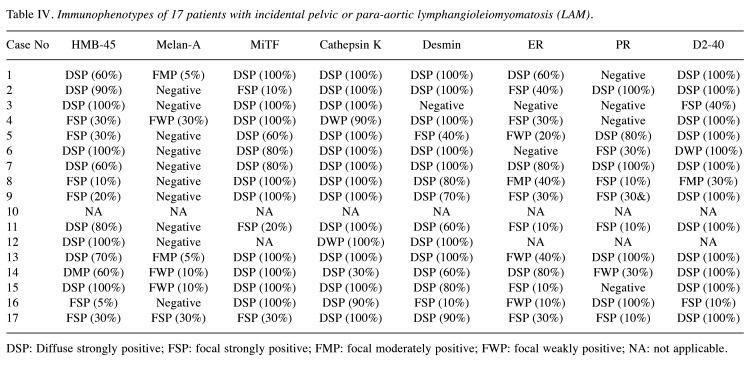

Pathological features. Table III details the pathological characteristics of the patients. The mean number of lymph nodes sampled was 12 (range=4-26). In over half of the patients (9/17, 52.1%), LAM affected multiple lymph nodes, with right-sided and unilateral involvement (15/17, 88.2% for both). The mean size of the affected nodes was 5.4 mm (range=1.0-19.3 mm), and the mean proportion of the intranodal microscopic area replaced by LAM was 34.1% (range=5%-99%). In the two patients with TSC, the greatest dimensions of affected lymph nodes were 19.3 mm and 7.6 mm, and the areas occupied by LAM were 99.0% and 90.0%, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the histological and immunohistochemical features of nodal LAM. LAM lesions consisted of bland epithelioid or spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, similar to normal smooth muscle cells. Epithelioid LAM cells exhibited a nested or nodular architecture (Figure 1A) and demonstrated varying degrees of cathepsin K immunoreactivity (Figure 1B). The nests of LAM cells were surrounded by cleft-like lymphatic spaces highlighted by D2-40 immunostaining (Figure 1C). Lesional cells showed reactivity for HMB45 (Figure 1D), MiTF (Figure 1E), desmin (Figure 1F), and ER (Figure 1G). In four cases (23.5%), LAM cell clusters were located adjacent to metastatic carcinoma cells and glands (Figure 1H and I), and it was considered possible that metastatic carcinoma cells could be overlooked due to their sparse presence. In one instance, metastatic endocervical adenocarcinoma cells were obscured by proliferating LAM cells. Spindle cell areas of LAM lesions displayed a fascicular growth pattern with a less distinct lymphatic endothelial lining. There was no evidence of nuclear enlargement, pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, or brisk mitotic activity. Additionally, no necrosis or hemorrhage was observed. Although LAM predominantly involved the nodal parenchyma, it also extended into the subcapsular sinus and extranodal lymphatic vessels or soft tissue in some cases.

Table III. Pathological characteristics of 17 patients with incidental pelvic or para-aortic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM).

AM: Adenomyosis; ENLV: extranodal lymphatic vessel; ENST: extranodal soft tissue; LM: leiomyoma; NP: nodal parenchyma; SCS: subcapsular sinus.

Figure 1.

Histological and immunophenotypical features of incidental nodal lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). (A) Epithelioid LAM exhibits a nested or nodular architecture and demonstrates varying degrees of immunoreactivities for (B) cathepsin K. (C) The LAM cell nests are surrounded by cleft-like lymphatic spaces, highlighted by D2-40 immunostaining. The lesional cells also react with (D) human melanoma black 45, (E) microphthalmia transcription factor, (F) desmin, and (G) estrogen receptor. (H and I) The LAM cell clusters (yellow arrows) are located closely adjacent to metastatic carcinoma cells and glands (white arrows), which can be overlooked because of their small quantity.

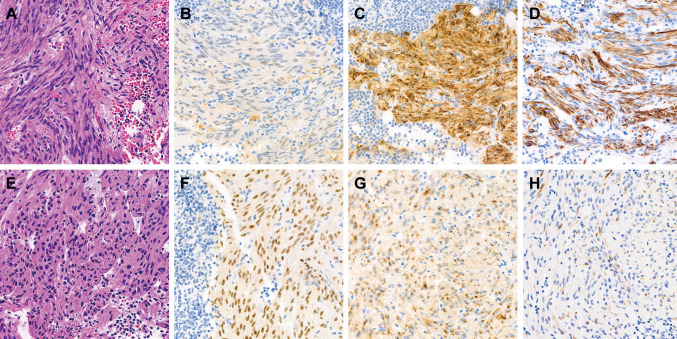

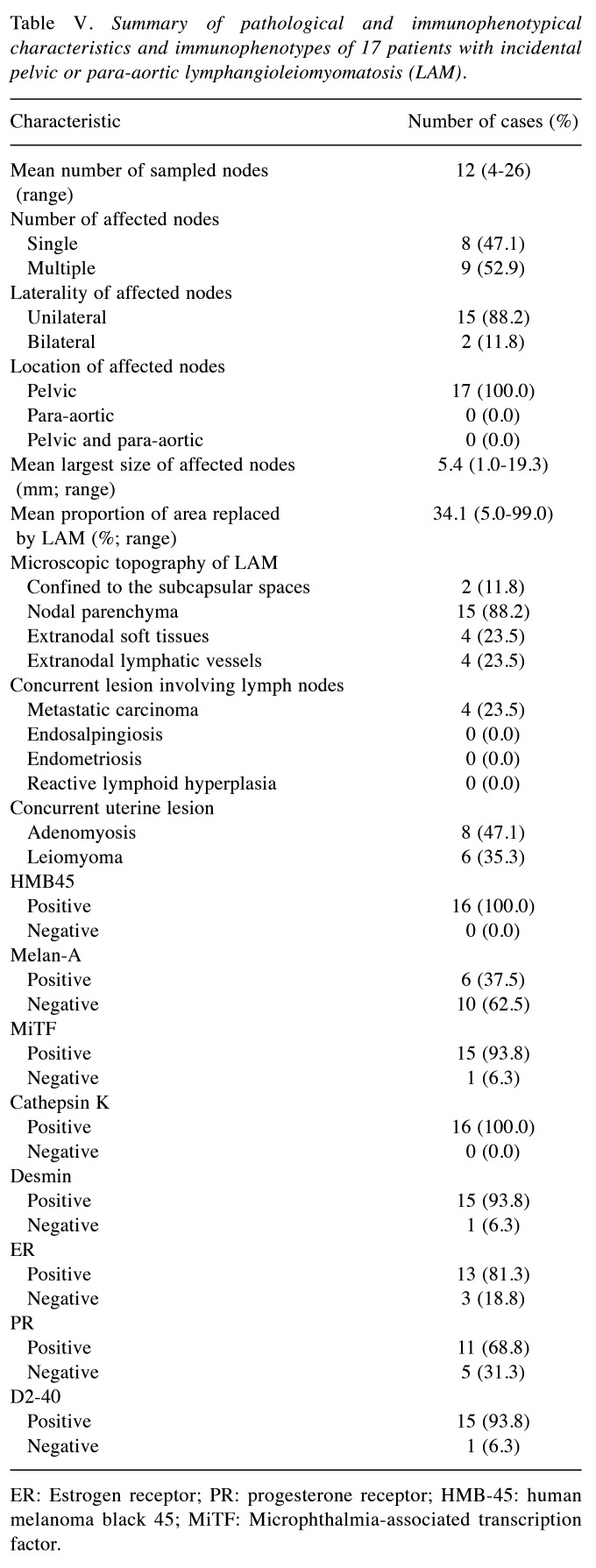

Immunostaining results. Table IV presents the results of immunostaining, which was performed in all but one case due to an insufficient nodal tissue sample. The most commonly expressed markers in LAM were HMB45 and cathepsin K, with 100% positivity in the 16 cases analyzed. LAM cells displayed diffuse and strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for both markers, with a granular staining pattern. The mean staining proportion for cathepsin K (94.4%; range=70%-100%) was higher than that for HMB45 (59.1%), which had a wider proportional range (5%-100%). High positivity rates were also noted for MiTF and desmin (93.8% for both). MiTF showed nuclear and cytoplasmic expression, while desmin was confined to the cytoplasm. D2-40 staining highlighted the lymphatic endothelial lining in all but one case (93.8%). The positivity rates for ER and PR were 81.3% and 68.8%, respectively, with variable staining intensities and proportions. Melan A was the least frequently expressed marker, showing focal weak-to-moderate immunoreactivity in six cases (37.5%). Differences in immunostaining patterns were noted between epithelioid and spindle cell lesions. Spindle LAM cells (Figure 2A) exhibited faint MiTF immunoreactivity (Figure 2B) but strong cytoplasmic expression of cathepsin K (Figure 2C) and desmin (Figure 2D). In contrast, epithelioid LAM cells (Figure 2E) showed uniform and strong nuclear MiTF expression (Figure 2F), moderate-to-strong perinuclear cathepsin K immunoreactivity (Figure 2G), and weak desmin expression (Figure 2H). Table V summarizes the pathological and immunophenotypic features of incidental nodal LAM cases.

Table IV. Immunophenotypes of 17 patients with incidental pelvic or para-aortic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM).

DSP: Diffuse strongly positive; FSP: focal strongly positive; FMP: focal moderately positive; FWP: focal weakly positive; NA: not applicable.

Figure 2.

Distinct immunostaining patterns between areas of (A-D) spindle cell and (E-H) epithelioid morphology in nodal lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). (A) Spindle-shaped LAM cells demonstrate (B) subtle immunoreactivity for MiTF and diffuse and strong cytoplasmic expression for (C) cathepsin K and (D) desmin. Conversely, (E) epithelioid LAM cells exhibit (F) consistent and strong nuclear expression for MiTF, (G) perinuclear dot-like immunoreactivity for cathepsin K, and (H) focal and weak expression for desmin.

Table V. Summary of pathological and immunophenotypical characteristics and immunophenotypes of 17 patients with incidental pelvic or para-aortic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM).

ER: Estrogen receptor; PR: progesterone receptor; HMB-45: human melanoma black 45; MiTF: Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor.

Discussion

In patients without signs or symptoms of pulmonary LAM, some studies suggest that nodal LAM presence indicates a high likelihood of developing pulmonary LAM (26,27). Matsui et al. (26) analyzed 22 Japanese patients with nodal LAM and reported that the diagnosis preceded that of pulmonary LAM by 1-2 years, with half of the patients being asymptomatic. Similarly, Chu et al. (27) found that in 27 out of 35 patients (77.1%) with pulmonary LAM, imaging revealed retro-peritoneal lymphadenopathy. In contrast, Rabban et al. (8) reported that in all 26 patients studied, the nodal LAM was occult with a mean size of 3.5 mm, and none had a history of pulmonary LAM or respiratory failure. They concluded that nodal LAM does not necessarily correlate with TSC or pulmonary LAM when incidentally detected during staging surgery for gynecological or urinary tumors (8). Similarly, Schoolmeester and Park (7) also showed that none of their 19 patients had a history of TSC, renal AML, or pulmonary LAM, and none exhibited clinical manifestations of pulmonary LAM. This suggests that incidentally discovered nodal LAM may not predict the development of pulmonary LAM. Taken together, the clinical relevance of nodal LAM in predicting pulmonary LAM remains controversial. Although a few studies have examined the prognostic significance of small incidental LAM detected in lymph nodes resected for unrelated purposes, nodal LAM still appears to exhibit two distinct clinical behaviors (7). In most patients, it is a non-aggressive, incidental finding with insignificant prognostic value, while in a few cases, it represents a precursor to destructive LAM, such as pulmonary LAM or multiple extrapulmonary LAMs. Therefore, we aimed to analyze the clinicopathological characteristics of incidental pelvic nodal LAM with respect to its association with the development of pulmonary LAM.

In this study, among the 17 patients with incidental nodal LAM, two (11.8%) developed pulmonary, renal, and uterine LAM. This proportion was higher than that in a previous study (2/61; 3.3%) (28). However, our findings do not necessarily indicate a direct association between pelvic LAM and the development of TSC, pulmonary LAM, or multiple extrapulmonary LAMs. Both affected patients (41 and 43 years old) were younger than the mean age of 52.1 years, and their affected nodes (19.3 mm and 7.6 mm) were much larger than those of other patients. The proportions of microscopic areas replaced by LAM were 99.0% and 90.0%, respectively. In a previous study by Schoolmeester and Kay (7), the largest nodal LAM (25 mm) was also locally aggressive. The authors emphasized lesion size as a key clinical prognostic factor, rather than the total number or distribution of lesions. Similarly, Matsui et al. (26) found that patients who developed pulmonary LAM had nodal LAMs measuring at least 10 mm. A review by Jaiswal et al. (29) also highlighted that patients with nodal LAMs of at least 10 mm either had concurrent pulmonary LAM or developed it later. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that larger LAM lesions, extensive (≥90%) involvement of the nodal area, or both may help predict the development of pulmonary LAM or other PEComa family tumors. Given the locally destructive nature of pulmonary LAM and its association with respiratory failure, screening and early detection of large nodal LAM could improve patient outcomes by facilitating earlier intervention.

Histologically, LAM involving extranodal soft tissue can resemble intravenous leiomyomatosis and angiomyomatous hematoma (8), as all three exhibit benign spindle cell proliferation with smooth muscle differentiation. The presence of large dilated veins surrounding leiomyomatous nodules favors the diagnosis of intravenous leiomyomatosis. Nodal angiomyomatous hamartoma is characterized histologically by the partial replacement of normal nodal parenchyma with proliferating smooth muscle cells and disorganized blood vessels. The presence of irregularly distributed, thick-walled vessels within a dense fibrocollagenous stroma supports the diagnosis of angiomyomatous hamartoma. Concurrently, nodal LAM cells frequently coexist with metastatic carcinoma cells, which might be overlooked due to their minimal quantity or because they are obscured by proliferating LAM cells. In this study, two cases of endocervical adenocarcinoma, one case of endometrial endometrioid carcinoma, and one case of ovarian clear cell carcinoma metastasized to the pelvic lymph nodes, where LAM lesions were incidentally detected. While the histological diagnosis of nodal LAM is generally straightforward, immunostaining for melanocytic and smooth muscle markers can further confirm the diagnosis (30). Previous studies have shown that HMB45 and MiTF exhibit higher diagnostic sensitivity than other markers, such as melan A (7,8). In this study, we performed immunostaining for cathepsin K, which has recently been recognized as a sensitive marker for pulmonary LAM and PEComas (31,32). Although Uehara et al. (33) reported that varying degrees of cathepsin K immunoreactivity were observed in less than 50% of the lesion areas, moderate-to-strong cathepsin K immunoreactivity was observed in more than 50% of the lesion areas in most cases. More importantly, cathepsin K was found to be more consistently expressed in LAM cells than in MiTF and desmin cells, which exhibited different expression patterns between epithelioid and spindle cell morphologies. Moreover, MiTF expression was more diffuse and strongly positive in epithelioid LAM cells, whereas spindle cell lesions displayed faint MiTF expression. Desmin was uniformly positive in areas of spindle cell morphology with strong intensity; however, in epithelioid lesions, desmin immunoreactivity was focal and weak. Conversely, cathepsin K was strongly and diffusely expressed in both areas. These findings support the notion that a panel of multiple markers is necessary for the definitive diagnosis of LAM. Further investigations using larger cohorts of nodal LAM are necessary to clarify the positive rates, sensitivities, and specificities of markers and to evaluate the differences in their expression patterns.

One potential mechanism for LAM cell proliferation may be linked to sex hormones, potentially induced by an altered hormonal environment in patients with gynecological malignancies. Endometrial endometrioid carcinomas can induce a hyperestrogenic state. Given that endometrioid carcinoma and LAM typically show strong immunoreactivity for hormone receptors, sex hormones are believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of both conditions. Some researchers have hypothesized that pronounced ER and PR expression could correlate with the severity of pulmonary LAM in pregnant women (34). In this study, pulmonary LAMs in two patients with TSC exhibited strong immunoreactivity for hormone receptors, and metastatic carcinoma cells from the endometrium and ovary were detected in the lymph nodes impacted by LAM lesions. The frequent involvement of pelvic lymph nodes in LAM and its identification during gynecological surgery suggest that an altered hormonal environment may contribute to LAM pathogenesis. Further research is needed to elucidate the relationship between sex hormone levels and LAM development.

Study limitations. First, this study involved patients with incidental pelvic nodal LAM diagnosed and treated at a single institution, thereby constraining the reproducibility of the findings. A fundamental limitation of single-institution studies is their restricted external validity. Additionally, the exclusion of patients with LAM manifesting in other organs and tissues resulted in a relatively small cohort size, precluding a comparative analysis. Second, the molecular analysis required to investigate the pathogenic mechanisms of nodal LAM linked to gynecological malignancies was not within the scope of this research. Third, due to the limited sample size, the statistical significance of the expression status of the immunohistochemical markers could not be analyzed.

Conclusion

In summary, most small nodal LAM lesions, incidentally discovered during surgical staging for gynecological tumors, appear to have insignificant prognostic value. However, some cases with large nodal LAM occupying a substantial portion of the nodal parenchyma may raise awareness of the potential development of pulmonary and extrapulmonary LAM in women of reproductive age. A small number of metastatic carcinoma cells and glands might be overlooked in patients with nodal LAM. Immunostaining was conducted using eight melanocytic and smooth muscle markers; of these, cathepsin K was the most frequently expressed. While MiTF and desmin are also useful for diagnosis, variations in their expression patterns were observed depending on cellular morphology. Further research with larger cohorts is required to better understand the pathogenesis and clinical implications of NLAM.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the Authors declare conflicts of interest or financial ties regarding this study.

Authors’ Contributions

All Authors made substantial contributions to the conceptualization and design of this study, including collection, analysis, interpretation, and validation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final version to be published.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Samsung Medical Center Grant (SMO1240641) and a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (2023R1A2C2006223).

References

- 1.Ando H, Ogawa M, Watanabe Y, Tsurunaga K, Nakamura C, Tamura H, Ikeda K, Takahashi R, Nakajima R, Yoshida S, Tsujie T, Doi R, Wakimoto A, Adachi S. Lymphangioleiomyoma of the uterus and pelvic lymph nodes: a report of 3 cases, including the potentially earliest manifestation of extrapulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2020;39(3):227–232. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0000000000000589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starbuck KD, Drake RD, Budd GT, Rose PG. Treatment of advanced malignant uterine perivascular epithelioid cell tumor with mTOR inhibitors: single-institution experience and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(11):6161–6164. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoolmeester JK, Dao LN, Sukov WR, Wang L, Park KJ, Murali R, Hameed MR, Soslow RA. TFE3 translocation-associated perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) of the gynecologic tract: morphology, immunophenotype, differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(3):394–404. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoolmeester JK, Howitt BE, Hirsch MS, Dal Cin P, Quade BJ, Nucci MR. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) of the gynecologic tract: Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical characterization of 16 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(2):176–188. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He W, Cheville JC, Sadow PM, Gopalan A, Fine SW, Al-Ahmadie HA, Chen YB, Oliva E, Russo P, Reuter VE, Tickoo SK. Epithelioid angiomyolipoma of the kidney: pathological features and clinical outcome in a series of consecutively resected tumors. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(10):1355–1364. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCormack FX, Travis WD, Colby TV, Henske EP, Moss J. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: calling it what it is: a low-grade, destructive, metastasizing neoplasm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(12):1210–1212. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0848OE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoolmeester JK, Park KJ. Incidental nodal lymph-angioleiomyomatosis is not a harbinger of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a study of 19 cases with evaluation of diagnostic immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(10):1404–1410. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabban JT, Firetag B, Sangoi AR, Post MD, Zaloudek CJ. Incidental pelvic and para-aortic lymph node lymphangioleiomyomatosis detected during surgical staging of pelvic cancer in women without symptomatic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis or tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(8):1015–1025. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu J, Chung Y, Chae SW, Choi Y, Kim H, Do SI. Clinicopathological factors influencing resection margin involvement during mohs micrographic surgery for skin tumors. Anticancer Res. 2023;43(6):2707–2715. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.16437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu J, Kim H, Do S. Clinicopathological significance and predictive value of high intratumoral tumor budding in patients with breast carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2023;43(5):2323–2332. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.16397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung Y, Kim S, Kim HS, Do SI. High receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 (RIP3) expression serves as an independent poor prognostic factor for triple-negative breast carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2022;42(5):2753–2761. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H, Kim HS. Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: comparison between mismatch repair protein immunostaining and microsatellite instability testing. Anticancer Res. 2023;43(4):1785–1795. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.16332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park S, Cho Y, Kim HS. Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: clinicopathological and prognostic significance of L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM) over-expression. Anticancer Res. 2023;43(10):4559–4571. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.16650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koh HH, Park E, Kim HS. Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: genomic and immunohistochemical profiling with comprehensive clinicopathological analysis of 17 consecutive cases from a single institution. Biomedicines. 2023;11(8):2269. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11082269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HG, Kim H, Yeo MK, Won KY, Kim YS, Han GH, Kim HS, Na K. Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: comprehensive analyses of clinicopathological, molecular, and prognostic characteristics with retrospective review of 237 endometrial carcinoma cases. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2022;19(4):526–539. doi: 10.21873/cgp.20338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park S, Park E, Kim HS. Mesonephric-like carcinosarcoma of the uterine corpus: clinicopathological, molecular and prognostic characteristics in comparison with uterine mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma and conventional endometrial carcinosarcoma. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2022;19(6):747–760. doi: 10.21873/cgp.20357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoo H, Kim HS. Clinicopathological and prognostic values of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations in ovarian clear cell carcinoma for predicting tumor recurrence, platinum resistance and survival. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2023;20(6):626–636. doi: 10.21873/cgp.20411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H, Kim H, Kim HS. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the vagina harboring TP53 mutation. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12(1):119. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12010119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu J, Yeo MK, Lee SH, Lee MY, Chae SW, Kim HS, DO SI. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of programmed death ligand-1 SP142 expression in 132 patients with triple-negative breast cancer. In Vivo. 2022;36(6):2890–2898. doi: 10.21873/invivo.13030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee Y, Choi S, Kim HS. Comprehensive immunohistochemical analysis of mesonephric marker expression in low-grade endometrial endometrioid carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2024;43(3):221–232. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park S, Kim J, Jang W, Kim KM, Jang KT. Clinicopathologic significance of the delta-like ligand 4, vascular endothelial growth factor, and hypoxia-inducible factor-2α in gallbladder cancer. J Pathol Transl Med. 2023;57(2):113–122. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2023.02.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Na JM, Jung W, Kim M, Cheon YH, Lee JS, Song DH, Yang JW. Intravascular NK/T-cell lymphoma: a case report and literature review. J Pathol Transl Med. 2023;57(6):332–336. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2023.10.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee M, Jo U, Song JS, Lee YS, Woo CG, Kim DH, Kim JY, Yoon SO, Cho KJ. Clinicopathologic characterization of cervical metastasis from an unknown primary tumor: a multicenter study in Korea. J Pathol Transl Med. 2023;57(3):166–177. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2023.04.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koh HH, Oh YL. Papillary and medullary thyroid carcinomas coexisting in the same lobe, first suspected based on fine-needle aspiration cytology: a case report. J Pathol Transl Med. 2022;56(5):301–308. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2022.08.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang S, Choi YL, Shim HS, Lee GK, Ha SY, Korean Cardiopulmonary Pathology Study Group Usefulness of BRAF VE1 immunohistochemistry in non-small cell lung cancers: a multi-institutional study by 15 pathologists in Korea. J Pathol Transl Med. 2022;56(6):334–341. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2022.08.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsui K, Tatsuguchi A, Valencia J, Yu Z, Bechtle J, Beasley MB, Avila N, Travis WD, Moss J, Ferrans VJ. Extrapulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM): Clinicopathologic features in 22 cases. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(10):1242–1248. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.18500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu SC, Horiba K, Usuki J, Avila NA, Chen CC, Travis WD, Ferrans VJ, Moss J. Comprehensive evaluation of 35 patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest. 1999;115(4):1041–1052. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao S, Chen Y, Tang Q, Xu L, Zhao L, Wang Z, Yu E. Pelvic lymph node lymphangiomyomatosis found during surgery for gynecological fallopian tube cancer: a case report and literature review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:917628. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.917628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaiswal VR, Baird J, Fleming J, Miller DS, Sharma S, Molberg K. Localized retroperitoneal lymphangioleiomyomatosis mimicking malignancy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127(7):879–882. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-879-LRLMM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grzegorek I, Lenze D, Chabowski M, Janczak D, Szolkowska M, Langfort R, Szuba A, Dziegiel P. Immunohistochemical evaluation of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(6):3353–3360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett JA, Braga AC, Pinto A, Van de Vijver K, Cornejo K, Pesci A, Zhang L, Morales-Oyarvide V, Kiyokawa T, Zannoni GF, Carlson J, Slavik T, Tornos C, Antonescu CR, Oliva E. Uterine PEComas: a morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 32 tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(10):1370–1383. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chilosi M, Pea M, Martignoni G, Brunelli M, Gobbo S, Poletti V, Bonetti F. Cathepsin-k expression in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Mod Pathol. 2009;22(2):161–166. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uehara K, Kawakami F, Hirose T, Morita H, Kudo E, Yasuda M, Märkl B, Zen Y, Itoh T, Imai Y. Clinicopathological analysis of clinically occult extrapulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis in intra-pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes associated with pelvic malignant tumors: A study of nine patients. Pathol Int. 2019;69(1):29–36. doi: 10.1111/pin.12749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oprescu N, McCormack FX, Byrnes S, Kinder BW. Clinical predictors of mortality and cause of death in lymph-angioleiomyomatosis: a population-based registry. Lung. 2013;191(1):35–42. doi: 10.1007/s00408-012-9419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]