Abstract

Background/Aim

The use of hypnotic drugs can lead to accidents and injuries. However, few reports have shown their association with these events after adjusting for many concomitant medications. This study aimed to determine whether the use of hypnotic drugs was associated with accidents and injuries.

Patients and Methods

Using the Japanese Adverse Event Reporting Database, 772,387 reports published between September 2023 and April 2004 were analyzed. Reporting odds ratios (RORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for accidents and injuries associated with each hypnotic drug were calculated after adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

Of the total, 12,484 reports indicated association of hypnotic drugs with accidents and injuries. The use of each hypnotic drug was associated with accidents, injuries, and other adverse events. However, a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, reporting year, and concomitant medications showed a considerable decrease in ROR for melatonin receptor agonists (adjusted ROR=1.26; 95%CI=1.03-1.55) and dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs) (adjusted ROR=1.04; 95%CI=0.86-1.25). Particularly in DORAs, a loss of signal for accidents and injuries was observed.

Conclusion

The risk of accidents and injuries may vary with hypnotic drug use; however, DORAs may be less frequently associated with these events. The results of this study provide useful information for the selection of hypnotic drugs.

Keywords: Accident, adverse drug event, hypnotics, injury

Hypnotics are widely prescribed worldwide for the treatment of insomnia. Sedative pharmacological interventions include benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRAs), benzodiazepine-related drugs (Z-drugs), melatonin receptor agonists (MRAs), and dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs). Several leading organizations have recommended not to administer BZRAs and Z-drugs to elderly individuals (1,2). Dependence and cognitive decline are particularly problematic with these drugs (3,4). Previous studies have also shown that BZRAs are risk factors for falls (5,6). In contrast, several studies have reported that DORAs are not associated with falls (7-9). Thus, it has been shown that the risk of falls varies with each hypnotic drug.

Many medications should be used with caution while driving; hence, all hypnotics are banned in Japan. In particular, BZRAs and Z-drugs have been associated with traffic accidents (10,11). However, DORAs showed no difference in the driving ability of patients the next morning compared to the placebo (12,13). Similar to falls, the risk related to a decrease in driving ability may vary according to the hypnotics. Such events can lead to injury; however, few reports have shown an association between relatively new hypnotics, such as DORAs, and accidents or injuries. In addition, analyses with large sample sizes are desirable because of the need to adjust for the effects of concomitant medications as covariates.

The Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report (JADER) database contains data obtained during the post-marketing surveillance phase of a drug and is a valuable tool provided by the Japanese regulatory authorities; it reflects the reality of clinical practice. This database is similar to the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database of the United States. Several studies using the JADER database have reported an association between drugs and adverse events (14-16). Although these results alone do not lead to definitive conclusions, they do suggest a possible correlation between drug use and adverse events.

In this study, we aimed to determine whether the use of hypnotic drugs is a risk factor for accidents and injuries after adjusting for potential confounders using the JADER database.

Patients and Methods

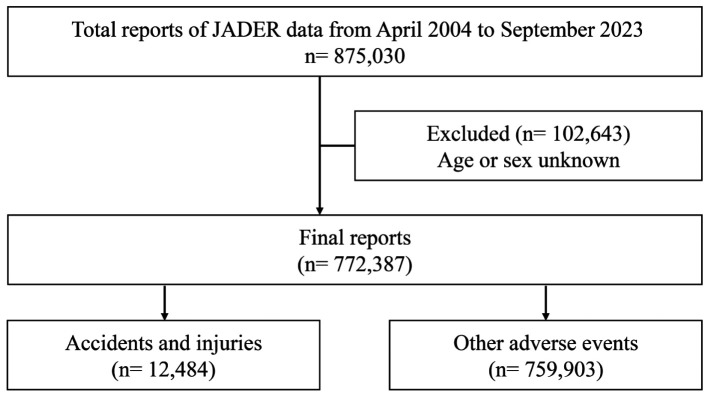

Study population. In this study, adverse event reports submitted to the JADER database between September 2023 and April 2004 were downloaded from the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency website. The JADER database, established by this agency, contains millions of adverse event reports voluntarily submitted by healthcare professionals and pharmaceutical companies. The database consisted of four data tables: patient attribute information (demo), drug information (drug), adverse events (reac), and underlying diseases (hist). These data provide information on patient attributes, such as sex and age, and clinical characteristics, such as the presence or absence of underlying diseases and drug use. These tables were combined to extract 875,030 reports, of which 772,387 were analyzed (Figure 1). Of the total, 102,643 reports with missing sex and age data were excluded from the analysis. This was an observational study using anonymized patient data recorded in the JADER database. The Ethics Committee of the Saga University Hospital confirmed that ethical approval and patient consent were not required due to the nature of the study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of data analysis.

Detection of signal for accidents and injuries. In the JADER database, adverse events were coded based on the terms recommended by the Japanese version of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA/J) version 26.1. Accident and injury events were identified using the related preferred terms (PTs) in the Standardized MedDRA Query (SMQ) for accidents and injuries (20000135). The hypnotics included in this study were BZRAs, Z-drugs, MRAs, and DORAs. In addition to these drugs, we also focused on antipsychotics, antidepressants, anti-anxiety, antiepileptic, opioids, antihypertensive, antidiabetic, antihistamines, and neuropathic pain drugs; each drug was classified according to its pharmacological action. The names of the drugs registered in each class are listed in Table I. In the JADER database, drugs contributing to adverse events are categorized into three groups: “suspicious drugs”, “concomitant drugs”, and “interactions”. All drugs were extracted from all categories used in this study. The reproducibility of the analysis results was confirmed by the co-authors.

Table I. Drugs used in the analysis.

ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI: angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor; BZRA: benzodiazepine receptor agonist; CCB: calcium channel blocker; FGA: first-generation antipsychotic; NaSSA: noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic; SNRI: selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant; TeCA: tetracyclic antidepressants.

Statistical analyses. Analyses were performed as previously described (17,18). The reports were divided into four groups: a) cases identified as accidents and injuries with the target medication, b) cases identified as accidents and injuries without the target medication, c) cases not identified as accidents and injuries with the target medication, and d) cases not identified as accidents and injuries without the target medication. The reported odds ratios (RORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the following formulas:

ROR=(a/b)/(c/d); 95%CI=exp [log (ROR) ± 1.96 √1/a + 1/b + 1/c + 1/d]

For the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the calculated RORs (crude RORs) for each hypnotics were adjusted for age; sex; reporting year; antipsychotic drugs divided into first-generation antipsychotics and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs); antidepressant drugs divided into tricyclic antidepressants, tetracyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant, trazodone, and vortioxetine; anti-anxiety drugs divided into BZRAs and others; antiepileptic drugs; opioids; antihypertensive drugs divided into angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, α blockers, β blockers, and αβ blockers; antidiabetic drugs divided into biguanides, sulfonylureas, grinides, α-glucosidase inhibitor, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors, thiazolidine, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, and insulin; antihistamines divided into 1st and 2nd generations; and neuropathic pain treatment. In addition, each hypnotic was included in the model as an explanatory variable to examine whether the targeted drugs were associated with accidents and injuries independent of other hypnotics. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to ensure that there was no multicollinearity among the different hypnotics. Statistical significance was defined as a lower 95%CI limit of ROR >1. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP®16 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Of the total, 12,484 analyzed reports indicated an association of hypnotics with accidents and injuries, and 759,903 indicated association with other adverse events. When several factors were compared, a higher percentage was found in accidents and injuries than in other adverse events for patients ≥70 years. Signals for accidents and injuries were detected using SGAs, antidepressant drugs (except SSRIs), anti-anxiety drugs (BZRAs), and neuropathic pain treatments (Table II).

Table II. Comparison of accidents, injuries, and other adverse events.

ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI: angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor; BZRA: benzodiazepine receptor agonist; CCB: calcium channel blocker; CI: confidence interval; FGA: first-generation antipsychotic; NaSSA: noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant; ROR: reporting odds ratio; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic; SNRI: selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant.

The association between hypnotics, accidents, injuries, and other adverse events is shown in Table III. Signals for accidents and injuries were detected for all hypnotics (BZRAs: crude ROR=1.19; 95%CI=1.10-1.29; Z-drugs: crude ROR=1.50; 95%CI=1.37-1.64; MRAs: crude ROR=2.05; 95%CI=1.68-2.50; DORAs: crude ROR=1.79; 95%CI=1.50-2.15). However, the multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, reporting year, and concomitant medications showed a considerable decrease in the ROR for MRAs (adjusted ROR=1.26; 95%CI=1.03-1.55) and DORAs (adjusted ROR=1.04; 95%CI=0.86-1.25). Particularly in DORAs, loss of signal for accidents and injuries was observed. The same results were observed when examining each drug within DORAs, such as suvorexant (adjusted ROR=1.05; 95%CI=0.85-1.28) and lemborexant (adjusted ROR=1.10; 95%CI=0.72-1.68) that showed a loss of signal for accidents and injuries after adjustment.

Table III. Association between hypnotics, accidents, and injuries.

Adjusted for age, sex, reporting year, antipsychotic drugs (FGAs and SGAs), antidepressant drugs (TCAs, TeCAs, SSRIs, SNRIs, NaSSA, trazodone, and vortioxetine), anti-anxiety drugs (BZRAs and others), antiepileptic drugs, opioids, antihypertensive drugs (ACE inhibitors, ARBs, CCBs, ARNI, MR inhibitors, α blockers, β blockers, and αβ blockers), antidiabetic drugs (biguanides, SUs, grinides, α-GIs, DPP-4 inhibitors, SGLT-2 inhibitors, Thiazolidine, GLP-1, and insulin), antihistamines (1st and 2nd generations), neuropathic pain treatment, and each hypnotic. ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; ARNI: angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor; BZRA: benzodiazepine receptor agonist; CCB: calcium channel blocker; CI: confidence interval; DORA: dual orexin receptor antagonist; DPP-4: dipeptidyl peptidase-4; FGA: first-generation antipsychotic; GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; MRA: melatonin receptor agonist; NaSSA: noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant; ROR: reporting odds ratio; SGA: second-generation antipsychotic; SGLT-2: sodium-glucose co-transporter-2; SNRI: serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SU: sulfonylureas; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant; TeCA: tetracyclic antidepressant; α-GIs: α-glucosidase inhibitor.

Discussion

This study used the JADER database to examine the associations of hypnotics with accidents and injuries. The results showed that after adjusting for confounding factors, each hypnotic was differentially associated with accidents and injuries. We believe that the decrease in the adjusted RORs in the MRAs and DORAs for accidents and injuries supports the results of previous reports. The accidents and injuries (SMQ: 20000135) used in this study included falls (PT: 10016173). A study of elderly patients in acute care hospitals found an association between falls and BZRAs but not with MRAs or DORAs (9). Studies with relatively large sample sizes have also suggested that MRAs and DORAs may not be associated with falls (19). In contrast, the use of BZRAs and Z-drugs is a known risk factor for falls, particularly in the elderly population (20). The mechanism of action of hypnotics depends on their type; MRAs and DORAs do not engage the gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor (21). Therefore, these drugs are less likely to induce sedation or muscle relaxation and may minimize the risk of falls.

Another major event within the accidents and injuries category (SMQ: 20000135) is road traffic accidents (PT: 10039203). Many drugs are known to increase the risk of road traffic accidents (22). The United States has the highest rate of death from motor vehicle accidents, with sedative use accounting for more than 30% of these accidents (23). Among them, BZRAs and Z-drugs have been epidemiologically shown to increase the risk of traffic accidents (10,11). However, epidemiological studies on MRAs and DORAs for traffic accidents are currently scarce. Studies examining the ability to drive the next morning after taking hypnotic drugs the night before have also found that BZRAs and zopiclone use decrease the driving ability of the user (24,25). Ramelteon et al. similarly reported reduced driving ability (26). In contrast, DORAs have been shown to have no effect on the driving ability of the user in the morning when administered before bedtime (12,13). However, these studies did not investigate the effects of concomitant medications. The concomitant medications used as covariates in this study were selected because of their potential impact on driving. Our results showed an association between accidents and injuries for all hypnotics before adjustment; however, the association between MRAs and DORAs weakened considerably after adjustment for these drugs or other hypnotics. In particular, DORAs lose their signals for these events, which may support existing studies reporting the lack of detrimental effects on the driving ability of patients taking DORAs.

This study has several strengths, including its large sample size and the ability to detect an association after adjusting for confounding factors, including concomitant medications. However, this study has some limitations. JADER is a voluntary reporting database. When using this database, the risks of accidents and injuries cannot be quantified without information on the total number of patients using hypnotics. In addition, this system has several biases, including under-reporting, over-reporting, missing data, exclusion of healthy participants, and the presence of confounding factors. However, we believe that large sample size data with drug information, in addition to accidents and injuries, are limited and useful for statistically adjusting covariates. The findings of this study can support future clinical studies.

Conclusion

Our study showed that the association of hypnotic dug use with accidents and injuries may vary depending on the specific hypnotic used. Among them, DORAs may be less frequently associated with these events. We believe that the results of this study provide useful information for the selection of hypnotics. However, further research is required to validate these results.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: R.S., F.N., J.N., and C.S.; Methodology: R.S., H.M., and C.S.; Formal analysis: R.S. and H.M.; Writing – Original Draft: R.S.; Writing – Review & Editing: R.S., A.M., K.S., H.Y., and C.S.; Supervision: H.T., Y.M., and A.M.; Resources: C.S. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank Koji Takeuchi, Akiko Emoto, and Sakiko Kimura (Saga University Hospital, Japan) for their advice on this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Nakatani Foundation Grant for Technology Development Research.

References

- 1.American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pottie K, Thompson W, Davies S, Grenier J, Sadowski CA, Welch V, Holbrook A, Boyd C, Swenson R, Ma A, Farrell B. Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(5):339–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khong E, Sim MG, Hulse G. Benzodiazepine dependence. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33(11):923–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Picton JD, Marino AB, Nealy KL. Benzodiazepine use and cognitive decline in the elderly. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(1):e6–e12. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartikainen S, Lönnroos E, Louhivuori K. Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(10):1172–1181. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, Patel B, Marin J, Khan KM, Marra CA. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torii H, Ando M, Tomita H, Kobaru T, Tanaka M, Fujimoto K, Shimizu R, Ikesue H, Okusada S, Hashida T, Kume N. Association of hypnotic drug use with fall incidents in hospitalized elderly patients: a case-crossover study. Biol Pharm Bull. 2020;43(6):925–931. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b19-00684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sogawa R, Emoto A, Monji A, Miyamoto Y, Yukawa M, Murakawa-Hirachi T, Tagomori Y, Kawasaki M, Kimura S, Shimanoe C. Association of orexin receptor antagonists with falls during hospitalization. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2022;47(6):809–813. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oda S, Takechi K, Hirai S, Takatori S, Otsuka T. Association between nocturnal falls and hypnotic drug use in older patients at acute care hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;79(6):753–758. doi: 10.1007/s00228-023-03485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dassanayake T, Michie P, Carter G, Jones A. Effects of benzodiazepines, antidepressants and opioids on driving. Drug Saf. 2011;34(2):125–156. doi: 10.2165/11539050-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustavsen I, Bramness JG, Skurtveit S, Engeland A, Neutel I, Mørland J. Road traffic accident risk related to prescriptions of the hypnotics zopiclone, zolpidem, flunitrazepam and nitrazepam. Sleep Med. 2008;9(8):818–822. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vermeeren A, Vets E, Vuurman EF, Van Oers AC, Jongen S, Laethem T, Heirman I, Bautmans A, Palcza J, Li X, Troyer MD, Wrishko R, McCrea J, Sun H. On-the-road driving performance the morning after bedtime use of suvorexant 15 and 30mg in healthy elderly. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016;233(18):3341–3351. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4375-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vermeeren A, Jongen S, Murphy P, Moline M, Filippov G, Pinner K, Perdomo C, Landry I, Majid O, Van Oers ACM, Van Leeuwen CJ, Ramaekers JG, Vuurman EFPM. On-the-road driving performance the morning after bedtime administration of lemborexant in healthy adult and elderly volunteers. Sleep. 2019;42(4):zsy260. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatano M, Yamada K, Matsuzaki H, Yokoi R, Saito T, Yamada S. Analysis of clozapine-induced seizures using the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report database. PLoS One. 2023;18(6):e0287122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koseki T, Horie M, Kumazawa S, Nakabayashi T, Yamada S. A pharmacovigilance approach for assessing the occurrence of suicide-related events induced by antiepileptic drugs using the Japanese adverse drug event report database. Front Psychiatry. 2023;13:1091386. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1091386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi A, Ikemura K, Wakai E, Kondo M, Okuda M. Proton pump inhibitors ameliorate oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy: retrospective analysis of two real-world clinical databases. Anticancer Res. 2023;43(12):5613–5620. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.16764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamo M, Sogawa R, Shimanoe C. Association of antiviral drugs for the treatment of COVID-19 with acute renal failure. In Vivo. 2024;38(4):1841–1846. doi: 10.21873/invivo.13637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishibashi Y, Sogawa R, Ogata K, Matsuoka A, Yamada H, Murakawa-Hirachi T, Mizoguchi Y, Monji A, Shimanoe C. Association between antidiabetic drugs and delirium: a study based on the adverse drug event reporting database in Japan. Clin Drug Investig. 2024;44(2):115–120. doi: 10.1007/s40261-023-01337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirata R, Katsuki NE, Shimada H, Nakatani E, Shikino K, Saito C, Amari K, Oda Y, Tokushima M, Tago M. The administration of lemborexant at admission is not associated with inpatient falls: a multicenter retrospective observational study. Int J Gen Med. 2024;17:1139–1144. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S452278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capiau A, Huys L, van Poelgeest E, van der Velde N, Petrovic M, Somers A, EuGMS Task, Finish Group on FRIDs Therapeutic dilemmas with benzodiazepines and Z-drugs: insomnia and anxiety disorders versus increased fall risk: a clinical review. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14(4):697–708. doi: 10.1007/s41999-022-00731-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madari S, Golebiowski R, Mansukhani MP, Kolla BP. Pharmacological management of insomnia. Neurotherapeutics. 2021;18(1):44–52. doi: 10.1007/s13311-021-01010-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elvik R. Risk of road accident associated with the use of drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence from epidemiological studies. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;60:254–267. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pagel JF. Drug-induced hypersomnolence. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12(3):383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verster JC, Veldhuijzen DS, Volkerts ER. Residual effects of sleep medication on driving ability. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8(4):309–325. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leufkens TR, Ramaekers JG, de Weerd AW, Riedel WJ, Vermeeren A. Residual effects of zopiclone 7.5 mg on highway driving performance in insomnia patients and healthy controls: a placebo controlled crossover study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231(14):2785–2798. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3447-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mets MA, de Vries JM, de Senerpont Domis LM, Volkerts ER, Olivier B, Verster JC. Next-day effects of ramelteon (8 mg), zopiclone (7.5 mg), and placebo on highway driving performance, memory functioning, psychomotor performance, and mood in healthy adult subjects. Sleep. 2011;34(10):1327–1334. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]