Abstract

Background/Aim

Immune checkpoint blockade has achieved great success as a targeted immunotherapy for solid cancers. However, small molecules that inhibit programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) binding are still being developed and have several advantages, such as high bioavailability. Previously, we reported a novel PD-1/PD-L1-inhibiting small compound, SCL-1, which showed potent antitumor effects on PD-L1+ tumors. These effects were dependent on CD8+ T-cell infiltration and PD-L1 expression on tumors. The present study investigated the in vivo antitumor activity of SCL-1 in various mouse syngeneic tumor models.

Materials and Methods

Twelve syngeneic mice models of tumors, such as colon, breast, bladder, kidney, pancreatic, non-small cell lung cancers, melanoma, and lymphomas, were used for in vivo experiments. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was analyzed by whole exome sequencing (WES) using reference DNA from mouse blood. The proportion of CD8+ T-cells infiltrating tumors before and after treatment was assessed using flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Results

SCL-1 had a markedly greater antitumor effect (11 sensitive tumors and 1 resistant tumor among the 12 tumor types) than the anti-mouse PD-1 antibody (8 sensitive tumors and 4 resistant tumors). In addition, the tumor growth inhibition rate (%) was more closely associated with TMB in the SCL-1 group than in the anti-PD-1 antibody group. Furthermore, in vivo experiments using PD-L1 gene knockout and lymphocyte-depletion technologies demonstrated that the antitumor activity of SCL-1 was dependent on CD8+ T-cell infiltration and PD-L1 expression in tumors.

Conclusion

SCL-1 has great potential as an oral immunotherapy that targets immune checkpoint molecules in cancer treatment.

Keywords: PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor, small chemical compound, mouse syngeneic tumors, tumor mutation burden (TMB), tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL)

More than 10 years have passed since the development of immune checkpoint inhibitor antibodies, and remarkable achievements in clinical trials have been obtained in the context of novel cancer immunotherapies (1-6). However, although extensive efforts have been dedicated to the development of novel small-compound inhibitors of programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) binding, effective compounds have yet to be identified. Generally, small chemical compounds have several advantages over existing immune checkpoint antibodies (7,8): 1) better bioavailability with oral administration, 2) superior in vivo distribution and metabolism in tumors, and 3) fewer adverse effects. Several therapeutic candidates, such as small compounds and peptide-based molecules, have been applied in early (phase I/II) clinical trials (9-15), but the value of these compounds has not yet reached the level of immune checkpoint antibodies.

Recently, researchers have developed an orally administered small-molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor, INCB086550, which has a biphenyl skeleton and has shown antitumor activity in phase I clinical trials against miscellaneous solid cancer (9,13). Interestingly, patients with mismatch repair enzyme deficiency (microsatellite instability-high) cancer were among the clinical responders. The progress of the clinical trial stage for INCB086550 and subsequent compounds have received much attention.

We developed a novel small compound that can inhibit PD-1/PD-L1 binding, SCL-1, via an ELISA system and in silico screening of 67395 compounds supplied by the Shizuoka small compound library. In addition, the potent antitumor activity of SCL-1 was observed in an HLA-matched humanized mouse model: this model can be used to evaluate the human immune responses in vivo (16).

In the present study, to assess the applicability of SCL-1 in a broader range of tumor types, we investigated its antitumor activity in vivo in twelve syngeneic mouse tumor models and dissected specific immunological mechanisms responsible for the antitumor effect.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and antibodies. Twelve mouse cancer cell lines were purchased or supplied as follows: The A20 (lymphoma, TIB-208), EL-4 (lymphoma, TIB-39), CT26 (colon cancer, CRL-2638), RENCA (kidney cancer, CRL-2947), EMT6 (breast cancer, CRL-2755), B16-F10 (melanoma, CRL-6475) and 4T1 (breast cancer, CRL-2539) cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Ex-3LL-luc (lung cancer, JCRB1716), MBT-2 (bladder cancer, IFO50041) and Colon26-luc (colon cancer, JCRB1496) were purchased from JCRB Cell Bank (Osaka, Japan). MC-38 (colon cancer) and PAN02 (pancreatic cancer) cell lines were obtained from the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis (DCTD) repository of the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-Frederich (Frederich, MD, USA).

The following antibodies were used for tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) analysis using flow cytometer. Anti-CD3-FITC (17A2), anti-CD4-PE (GK1.5), anti-CD8a-PerCP (53-6.7), anti-CD45-APC (30-F11), and anti-CD69-PE-Cy7 (H1.2F3) for the T cell subset; anti-CD44-FITC (IM7), anti-CD62L-PE-Cy7 (MEL-14), and anti-CD127-APC (A7R34) for the naïve/effector/memory T cell subset; and anti-CD279 (PD-1)-FITC (29F.1A12), anti-CD223 (LAG-3)-PE (C9B7W), anti-CD366 (TIM-3)-APC (B8.2C12), and anti-CD39-PE-Cy7 (Duha69) for the exhausted T cell subset; anti-B220-PE (RA3-6B2), anti-NK1.1-APC (PK136), and anti-CD19-PE-Cy7 (6D5) for the NK and B cell subset; anti-mouse I-A/I-E-PE (M5/114.15.2), anti-Ly-6G/Ly-6C (Gr-1)-PerCP (RB6-8C5), anti-CD11c-APC (N418), and anti-F4/80-PE-Cy7 (BM8) for myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) and dendritic cell (DC) subset; anti-CD25-APC (3C7), and anti-GARP (LRRC32)-PE-Cy7 (F011-5) for the regulatory T cell subset; all were purchased from BioLegend Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA).

The anti-PD-1 antibodies used for the in vivo experiments were purchased from Bio X Cell (Lebanon, NH, USA). For the in vivo CD4/CD8 antibody-depletion experiments, anti-CD4 (GK1.5) and anti-CD8 (53-5.8) antibodies were purchased from Bio X Cell.

For immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, the following antibodies were used: Anti-CD4 rabbit monoclonal antibody (D7D2Z) and anti-CD8 XP rabbit monoclonal antibody (D4W2Z); all were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-PD-1 goat polyclonal antibody (AF1021, R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), anti-F4/80 rat monoclonal antibody (C1:A3-1, Cedarlane Laboratories, Ontario, Canada), anti-FoxP3 rabbit monoclonal antibody (D6O8R, Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-CD205 mouse monoclonal antibody (ab124897, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were purchased from the indicated manufacturers.

Chemical reagents. The SCL-1 compound was synthesized in house as reported previously (16). BMS202 and INCB086550 were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA) and used as control reagents.

Establishment of PD-L1 knockout (KO) cell lines. The A20 and RENCA cell lines were subjected to CRISPR/Cas9-mediated KO of PD-L1. The specific method has been reported previously (16). Briefly, the Cells were transfected with TrueGuide™ synthetic gRNA (ID#CRISPR228292_SGM) and TrueCut™Cas9 protein v2 via the Neon™ Transfection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). Three days after transfection, the cells were sorted as single cells in 96-well plates. The proliferated clones were screened by flow cytometry using anti-mouse PD-L1 Ab (clone: 29E.2A3, BioLegend Inc.) and Sanger sequencing. A specific clone with a doubling time similar to that of the parental cells was selected and used for in vivo experiments (data not shown).

Cell proliferation assay. Cell proliferation was assessed using WST-1 assays (Dojin Kagaku Corp., Kumamoto, Japan) as reported previously (17). Briefly, 1×104 cells from each of the twelve mouse tumor cell lines were seeded on a 96-well microculture plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA), and compounds were added at concentrations ranging between 0.25 and 100 μM. After four days, the WST-1 substrate was added to the culture, and the OD was measured at 450 and 620 nm via a multimode plate reader (Nivo, PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

In vivo experiments using various syngeneic mouse tumor models. Seven- to nine-week-old female mice (C57BL/6J, BALB/cA and C3H/HeJ) were purchased from CLEA Japan, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). All the animals were cared for and treated according to the Guidelines for the Welfare and Use of Animals in Cancer Research and the experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shizuoka Cancer Center Research Institute. On day 0, 1×105 tumor cells suspended in 0.1 ml of physiological saline solution (PSS) were inoculated subcutaneously into the right flank of the mice. On day 7 or when the tumor volume reached 100-300 mm3, SCL-1 (25, 50 and 100 mg/kg) was orally administered for a total of 10 times over 14 days. Anti-PD-1 Ab was administered intraperitoneally at 2 mg/kg twice weekly for two weeks. Tumor volume and body weight were measured twice weekly; tumor dimensions were measured using a caliper. The tumor volume was calculated via the National Cancer Institute formula as follows: tumor volume (mm3)=length (mm)×[width (mm)]2×1/2. The tumor growth inhibition (TGI) rate was calculated as follows: TGI rate=(1-tumor volume of treated group/tumor volume control group)×100%. Three days after the last treatment, the spleens and tumors were harvested from the control group and small compound-treated group. Tumors from three mice were used for TIL analysis and IHC.

In the CD4 and CD8 antibody depletion experiment, an anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibody (Bio X Cell, 5 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally injected into the tumor-transplanted mice on days 2 to 4 after tumor transplantation, and SCL-1 administration was started on day 7. The antitumor effects of the SCL-1 compound were subsequently evaluated in T-cell-depleted mice. To investigate the influence of PD-L1 expression on the antitumor effects of SCL-1, PD-L1-KO mouse tumor cells (A20 or RENCA PD-L1-KO cells) were used.

Immunohistochemistry. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cancer tissue blocks and sections were made from twelve syngeneic mouse tumors and stained with various antibodies against immune cells. The number of positive cells in five fields of view at high magnification (×200) was calculated via the image analysis software WinRoof (Mitani Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with an in-house algorithm as reported previously (18).

Assessment of the tumor mutation burden (TMB) of syngeneic mouse tumor cells. Twelve mouse syngeneic tumor cells were transplanted subcutaneously into the right flank of the mice according to a standard method. Tumors were excised from each tumor-bearing mouse whose tumor size reached 50-1,000 mm3, and 25 mg of the tumor fragments were used for DNA extraction (Nucleospin Tissue, MACHEREY-NAGEL GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany). In addition, blood was collected from each mouse syngeneic tumor host and used for DNA extraction (NucleoSpin Blood, MACHEREY-NAGEL GmbH & Co. KG). The tumor mutations were identified using a NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The number of small variants per megabase was defined as the tumor mutation burden (TMB), which was determined as follows: TMB=N/L, where N and L represent the number of somatic variants and callable region size, respectively. A callable site was defined as a genomic position where the normal and tumor depths was ≥5 and 15, respectively. DAGEN’s output file named ‘’-somatic callable-regions.bed’’ was used for this analysis.

Statistical analysis. Significant differences in tumor volume were analyzed using the Steel test (multiple comparison), the Mann-Whitney U-test and Student’s t-test. Significant differences in survival duration were assessed by comparing Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Correlations between different parameters were analyzed using a Spearman correlation coefficient test. p-Values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Determination of TMB values of syngeneic mouse tumor cell lines. The SNV numbers and TMB values obtained following WES analysis of twelve syngeneic mouse tumor cell lines are shown in descending order in Table I. The Ex-3LL-luc cells presented a markedly high TMB. In addition, EL-4, MC-38, MBT-2 and CT26 cells presented high TMB (more than 100 mutations per megabase). Among all cell lines, 4T1 had the lowest TMB.

Table I. Single nucleotide variation (SNV) and tumor mutation burden (TMB) numbers in syngeneic mouse tumor cell lines.

Cell proliferation assay. SCL-1 did not cause significant cell cytotoxicity except in the A20 cell line, which exhibited minor growth inhibition, with an IC50 value of 54.8. In contrast, BMS202 strongly inhibited the growth of all the cell lines. Another PD-1/PD-L1 small molecular inhibitor, INCB086550, showed moderate cytotoxicity, except in the B16-F10 and PAN02 cell lines (data not shown).

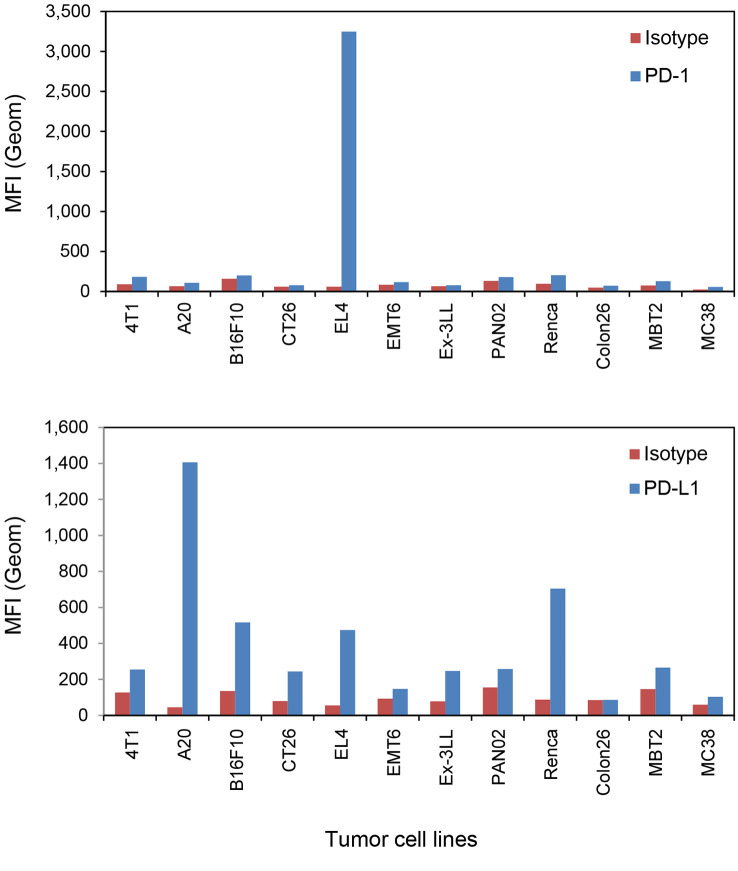

PD-1/PD-L1 expression levels in syngeneic mouse tumor cell lines. PD-1 and PD-L1 protein expression was assessed using flow cytometry, and CD8 and FoxP3 protein expression were evaluated using IHC staining. EL-4 cells presented markedly high PD-1 protein expression, and high PD-L1 expression was observed in A20, EL-4 and RENCA cells (Figure 1). In the comparison of PD-L1 levels and tumor growth inhibition by SCL-1 in vivo, PD-L1 levels was evaluated as the ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the anti-PD-L1 antibody to the MFI of the isotype antibody.

Figure 1.

Mouse PD-1 and PD-L1 expression levels in twelve mouse tumor cell lines determined using flow cytometry. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of mouse PD-1 and PD-L1 expression is shown. In the histogram data, the MFI from the isotype antibody stain is shown in red, and the MFI from anti-mouse PD-1 or anti-mouse PD-L1 antibody stain is shown in blue. Finally, the intensity ratio (test Ab intensity/isotype Ab intensity) was calculated and used for association analysis. Each column shows the mean value from two staining experiments.

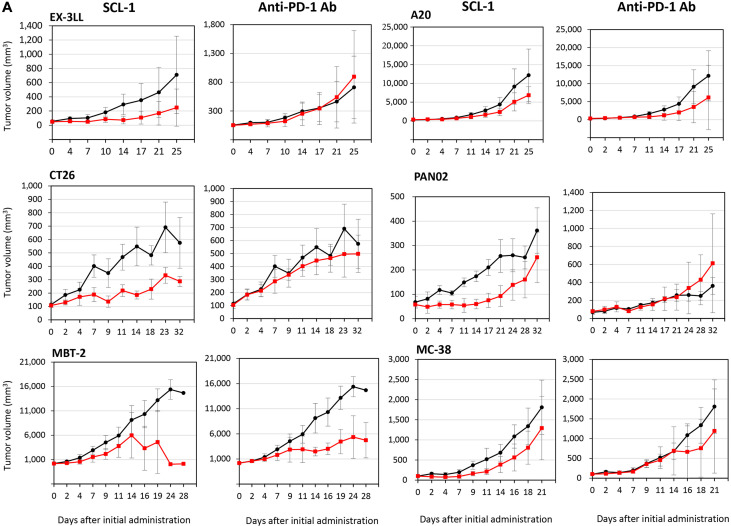

In vivo experiments using twelve syngeneic mouse tumor models. On the basis of the criteria for antitumor effects in vivo reported by Georgiev et al. in 2022, SCL-1 exhibited a markedly greater antitumor effect (11 sensitive tumors and 1 resistant tumor among of 12 tumor types) than did the anti-mouse PD-1 antibody (8 sensitive tumors and 4 resistant tumors; Figure 2 and Table II), indicating that the antitumor effect of SCL-1 alone might be comparable to that of the anti-PD-1 antibody. In particular, tumors were completely eradicated in a few mice transplanted with EMT6 or A20 tumor cells, and inoculated tumor cells in the rechallenge trial were rejected (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Antitumor effects of the SCL-1 compound and anti-mouse PD-1 monoclonal antibody against twelve syngeneic mouse tumors. The growth-inhibiting activity of SCL-1 or anti-PD-1 antibody is shown in Figure 2A (against Ex-3LL, CT26, MBT-2, A20, PANC02, and MC-38) and Figure 2B (against Colon26, RENCA, B16-F10, EMT6, EL-4, and 4T1). The black line represents control tumors without treatment and the red line indicates tumors treated with SCL-1 or anti-PD-1 antibody. While in most murine tumors, results at a dose of 50 mg/kg SCL-1 are shown, in RENCA tumors, results at a dose of 100 mg/kg are indicated. Anti-PD-1 Ab was administered intraperitoneally at 2 mg/kg twice weekly. Each point represents the mean±SD of six mice.

Table II. Antitumor effect of SCL-1 compound and anti-PD-1 antibody on syngeneic mouse tumor models.

TGI: Tumor growth inhibition; CR: complete response (>70%TGI); PR: partial response (30%-70% TGI); R: resistant (<30% TGI). Survival was analyzed using the log-rank test (Kaplan-Meier); *p<0.05 versus control group.

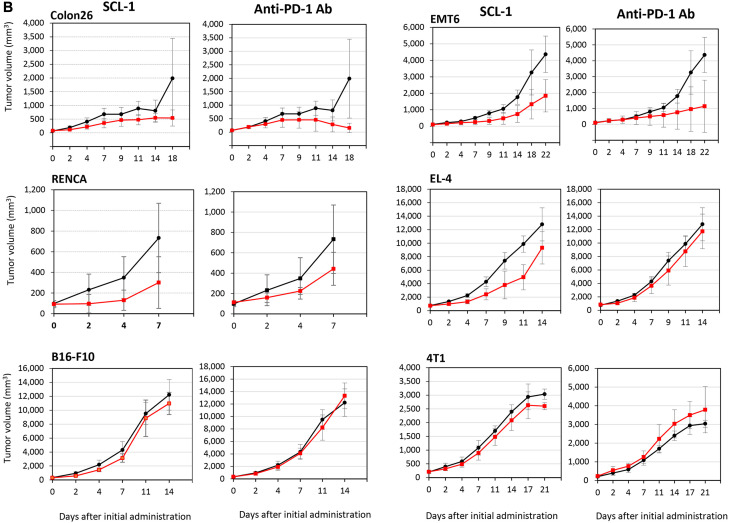

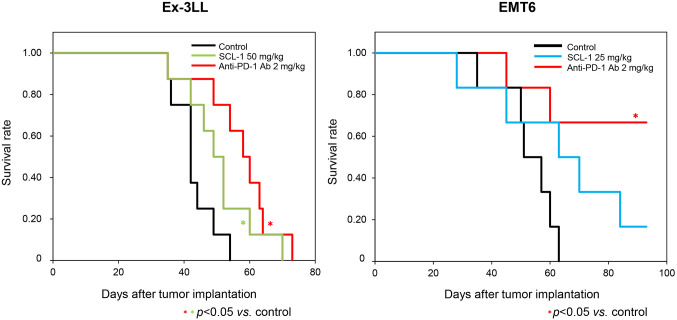

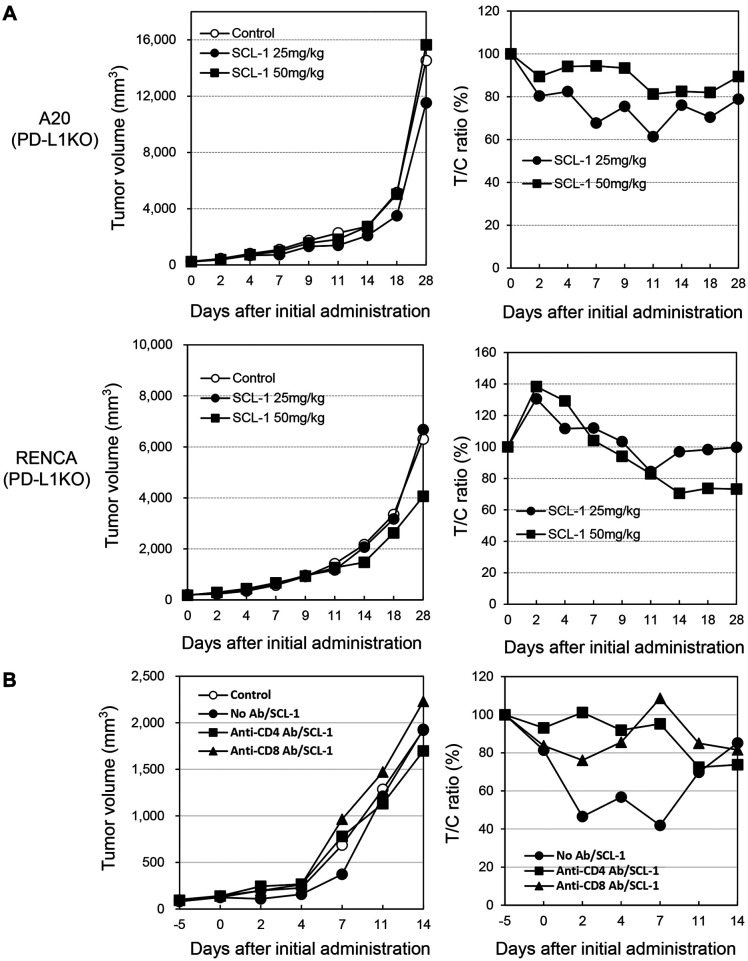

SCL-1 promoted the survival of Ex-3LL cells alone, and the anti-mouse PD-1 antibody improved survival in Ex-3LL and EMT-6 cells (Figure 3 and Table II). Furthermore, SCL-1 did not significantly inhibit the growth of PD-L1 KO A20 or PD-L1 KO RENCA tumors, while it affected wild-type tumors (Figure 4A). In addition, the administration of anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibodies in vivo significantly suppressed the antitumor effect of SCL-1 on RENCA tumors (Figure 4B). The suppressive effect of CD8+ T-cell depletion seemed to be greater than that of CD4+ T-cell depletion.

Figure 3.

Survival benefit of the SCL-1 compound and anti-mouse PD-1 antibody in mouse syngeneic tumor models. The effect of each reagent on overall survival in tumor-bearing mice was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method. In the Ex-3LL tumor model (left panel), the cohorts are indicated by the black line (control group), green line (SCL-1-treated group) and red line (anti-mouse PD-1 antibody-treated). For the EMT6 tumor model (right panel), the cohorts are indicated by the black line (control group), blue line (SCL-1-treated group) and red line (anti-mouse PD-1 antibody-treated). *Statistically significant, p<0.05. Each cohort consisted of eight tumor-bearing mice.

Figure 4.

Effect of PD-L1 gene knockout and T lymphocyte depletion on the antitumor effect of SCL-1 on mouse tumors in vivo. (A) Effect of PD-L1 gene knockout on SCL-1 antitumor activity in A20 and RENCA tumors. PD-L1 gene knockout cell clones were obtained using the CRISPR Cas9 method in clones #2 (A20) and #9 (RENCA). Tumor volumes and the ratio of tumor/control volumes are shown. (B) Impact of T-cell depletion on SCL-1 antitumor activity in RENCA tumors. Closed circle: no antibody treatment; closed square: anti-CD4 antibody treatment; closed triangle: anti-CD8 antibody treatment. *p<0.05. Each point represents the mean value of six mice.

Characterization of TIL profile in SCL-1-treated mouse tumors using flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. TIL profiling using flow cytometry was performed in Colon26 and RENCA tumors treated with SCL-1. In RENCA tumors, SCL-1 promoted the accumulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells inside the tumors, and the fold increases were 2.7 and 5.4, respectively, compared with those in the control tumors (Table III). In contrast, in Colon26 tumors, the TIL-increasing effect was not remarkable, but there was a tendency toward a reduction in PD-1+Tim3+ exhausted T-cells in SCL-1-treated tumors (Table IV).

Table III. Flow cytometry analysis performed on tumors from control or -treated mice bearing RENCA tumors.

Tumors were harvested from the control group and treated group. Each value shows the mean±SD of three mice. *p<0.05, statistically significant using unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Table IV. Flow cytometry analysis in control or treated mice bearing Colon26 tumors.

Tumors were harvested from the control group and treated group. Each value shows the mean±SD of three mice. NE: Not evaluated. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired two-tailed t-test.

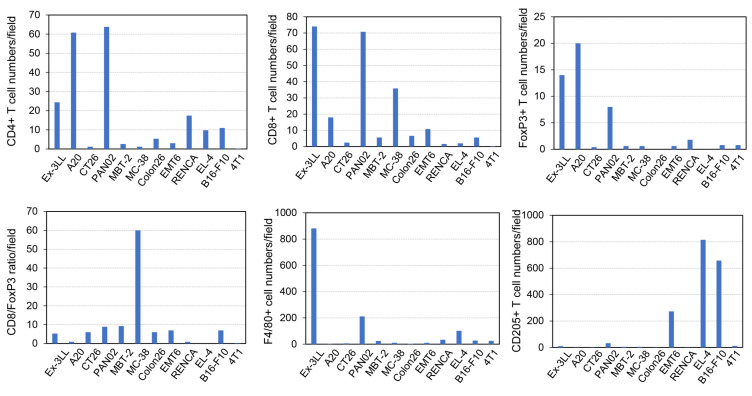

Furthermore, IHC analysis was performed on all twelve tumors treated with SCL-1. The numbers of immune cells positive for CD4, CD8, FoxP3, F4/80 and CD205 according to IHC were counted using a semiautomated in-house algorithm. In addition, the specific ratio of the number of CD8+ cells to the number of Foxp3+ cells in each visual field was calculated, and the association of the ratio with tumor growth inhibition was analyzed.

The infiltration of T-cells and FoxP3+ cells was increased in tumors derived from the Ex-3LL, A20 and Pan02 cell lines (Figure 5). Interestingly, MC-38 cell-derived tumors presented the highest ratio of CD8+/Foxp3+ cells, and Ex-3LL cell-derived tumors also exhibited high infiltration of F4/80+ macrophages.

Figure 5.

Characterization of tumor-infiltrating immune cells before treatment using immunohistochemistry and image-analysis software. Various antibodies, such as anti-CD4, anti-CD8 and anti-FoxP3 antibodies for T-cells; anti-F4/80 antibody for macrophages; and anti-CD205 antibody for dendritic cells, were used for immune cell staining. Five fields of view in sections of each tumor at high magnification (×200) were selected, and positive cell numbers were assessed using image-analysis software. The mean positive cell count per field is shown in the blue column. Finally, the CD8+ number/FoxP3+ number ratio was calculated and used for association analysis.

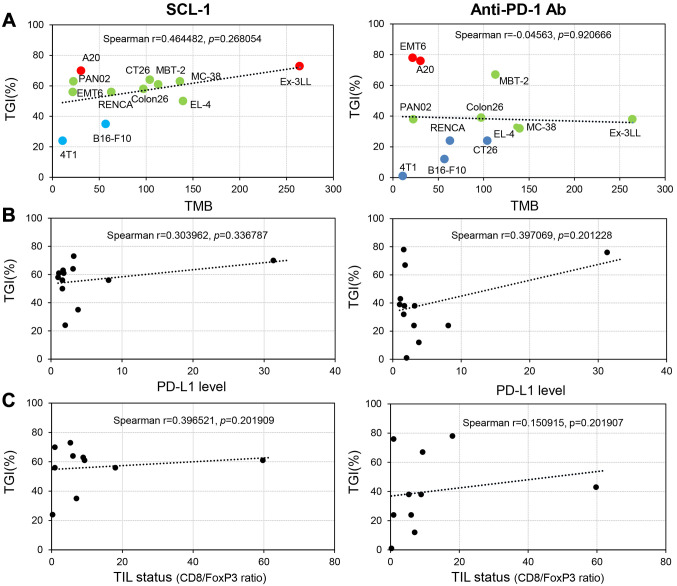

Associations of the TMB, PD-L1 expression level and TIL status with tumor growth inhibition. In the SCL-1-treated mice, there was a moderate (r=0.464) association between TMB and the tumor growth inhibition rate and a weak (r=0.397) association between TMB and the TIL status (CD8+/FoxP3+ cell ratio) (Figure 6). In contrast, in the anti-PD-1 Ab-treated mice, there was a weak (r=0.397) association only between the PD-L1 level and the tumor growth inhibition rate. Importantly, no significant association between TMB and the tumor growth inhibition rate was identified in the anti-PD-1 Ab therapy group.

Figure 6.

Associations of in vivo tumor-growth inhibition (TGI) by SCL-1 compound or anti-PD-1 antibody with various tumor microenvironment (TME) parameters, such as the tumor mutation burden (TMB), mouse PD-L1 level and tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) status. (A) Moderate association with TMB (r=0.464482). Mouse tumor TMB was assessed via whole-exome sequencing (WES) using tumor-derived DNA. (B) PD-L1 level and (C) TIL status were weakly associated with the TGI rate (r=0.303962 and 0.396521, respectively). TME parameter data were collected from 12 mouse tumor tissues, and the associations with the TGI rate of SCL-1 or anti-PD-1 antibody were analyzed using a Spearman coefficient test.

Discussion

Since the discovery of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) antibodies, despite intensive efforts to develop small compound-based ICI therapeutics by BMS or other researchers (19-21), effective compounds have yet to be identified. There are several potential reasons: 1) few mouse tumor models have been used to evaluate the antitumor effects of ICI compounds other than the MC-38 cell line, in which the ICI antibody has a significant antitumor effect (22-24): 2) the small molecule ICI with a biphenyl skeleton does not bind to mouse PD-L1 (25,26): and 3) a specific humanized mouse tumor model (27) is needed.

Previously, we reported that the novel small compound SCL-1, which inhibits PD-1/PD-L1 binding, had a potent antitumor effect on a humanized mouse model in which human PBMCs and HLA-A2 matched lymphoma cell line SCC-3 with a high PD-L1 expression level were transplanted (16). In addition, the antitumor activity of SCL-1 was diminished in PD-L1 gene knockout (KO) SCC-3 tumors and in a T-cell depletion tumor model. These results suggested that the antitumor activity of SCL-1 was dependent on PD-L1 expression and T-cell infiltration.

In the present study, we investigated the in vivo antitumor activity of SCL-1 in twelve mouse syngeneic tumor models and demonstrated that SCL-1 had a markedly greater antitumor effect (11 sensitive tumors and 1 resistant tumor among 12 tumor types) compared to anti-mouse PD-1 antibody (8 sensitive tumors and 4 resistant tumors). Among the SCL-1-treated tumors, 10 tumors showed more than 50% growth inhibition and only one tumor (4T1) was resistant to SCL-1. Remarkably, the strongest antitumor activity and the highest TMB were observed in the tumors derived from Ex-3LL cells, a KRAS-mutant mouse lung cancer cell line (28), among the 12 tumor types. However, among the SCL-1-treated tumors, there were still four tumors resistant to the anti-mouse PD-1 antibody. In addition, TIL analysis using flow cytometry revealed that the infiltration of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, including CD8+PD-1+ T-cells, were significantly greater in the SCL-1-treated group than in the anti-PD-1 Ab-treated group. These results indicate that SCL-1 has obviously stronger antitumor activity than the commercially available anti-mouse PD-1 antibody, which is frequently used for mouse in vivo experiments. In addition, the tumor growth inhibition rate (%) was more closely associated with TMB in the SCL-1 group than in the anti-PD-1 antibody group. Furthermore, in mouse PD-L1-KO tumors (A20 and RENCA tumors) and mouse T-cell depleted tumors (RENCA), the antitumor activity of SCL-1 disappeared. These observations suggest that SCL-1 acts on mouse PD-L1 molecules and that the antitumor activity of SCL-1 is dependent on mouse PD-L1 levels and mouse T-cell-mediated immune responses.

To the best of our knowledge, the most potent anti-mouse PD-1 antibody is considered to be muDX400, a rodent-surrogate pembrolizumab antibody, which was reported by Georgiev et al. (29). They demonstrated that muDX400 exhibited moderate or increased antitumor activity in many syngeneic mouse tumor models and that its antitumor effect was associated with high TMB and neoantigen numbers. These results suggest that the SCL-1 compound has significant in vivo antitumor effects comparable to those of the potent muDX400 antibody and has a similar association with high TMB.

In addition, the TIM3 molecule could be involved in the mechanism of the antitumor effect of SCL-1. The PD-1+TIM3+ exhausted T-cell population tended to decrease in SCL-1-treated mouse tumors, such as Colon26 and RENCA tumors (Table III). Previously, we reported that the TIM3 gene was identified as a bad prognostic factor in patients with cancer who were classified into PD-L1+CD8+ or had immunologically hot tumor microenvironment (30). Considering that TIM3 is a late exhaustion marker, an irreversible turning point, which resulted in T-cell apoptosis and cell death (31), the immunological effect of SCL-1 on TIM3 expression is very impressive and promising for precise analysis of the SCL-1 antitumor mechanism.

Recently, an oral small-molecule PD-1/PD-L1 binding inhibitor, INCB086550, which was developed by Incyte Inc. (Wilmington, DE, USA), has shown a clinical response in cancer patients with microsatellite instability-H (MSI-H) and mismatch-repair-deficient (dMMR) in a phase 1 clinical trial (13), but the response rate is still low, and adverse effects, such as neurotoxicity, are a concern. MSI-H or dMMR solid cancers (high TMB) are good responders to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy (32-36) in combination with chemoradiation therapy; therefore, those cancers could be good targets for oral small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 binding inhibitors.

In the present study, we identified a significant antitumor effect of SCL-1 on twelve mouse syngeneic tumors and verified that its antitumor effect was dependent on the PD-L1 expression level and T-cell immune response. Considering that the antitumor activity of SCL-1 alone is comparable to that of anti-mouse PD-1 antibodies, SCL-1 could be an unprecedented and promising compound. In addition, there are several advantages of SCL-1 over immune checkpoint antibodies: 1) good absorption according to absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADMET) score, 2) oral administration route, 3) good intratumoral retention (10 μM or higher), 4) few adverse effects and 5) low cost.

Various biological characteristics of SCL-1 have been investigated so far and compared with those of other PD-1/PD-L1 small compounds with antitumor activity in vivo, as reported in Table V (22-24). In particular, several compounds have been applied in clinical trials (9-15). In the meantime, SCL-1 has shown potent antitumor effects against many different mouse tumor cells and a specific association of antitumor effects with TMB and PD-L1 expression, which have not been identified for other small compounds. In particular, this is the first report of the association of tumor growth inhibition by a small chemical compound, specifically SCL-1, with TMB.

Table V. List of compounds with PD-1/PD-L1 binding inhibition.

In the near future, we need to investigate which types of cancer are suitable for SCL-1 compounds via a humanized mouse model in which human PBMCs and HLA-matched human cancer cell lines are transplanted and potentially advance this compound to the early phase of human clinical trials of cancer immunotherapy.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

Tadashi Ashizawa designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Tadashi Ashizawa, Akari Kanematsu and Kouji Maruyama performed the in vivo experiments and organized the animal studies. Takayuki Ando designed and synthesized the chemical compounds. Akira Iizuka, Haruo Miyata, Kazue Yamashita and Yasufumi Kikuchi performed the immunological assays and in vitro experiments. Chie Maeda performed a FACS analysis of TILs and spleens from tumor-bearing mice. Tomoatsu Ikeya examined TIL numbers using IHC analysis. Kenichi Urakami and Takeshi Nagashima performed whole-exome sequencing via murine tumor-derived DNA and measured TMB levels. Ken Yamaguchi reviewed the manuscript. Yasuto Akiyama supervised the entire study and was responsible for completing the study. All the Authors read and approved the final draft.

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank Dr. Koji Maruyama and Mr. Koji Takahashi for excellent assistance in maintaining the tumor-bearing mice in the animal facility.

References

- 1.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, Leming PD, Spigel DR, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Drake CG, Pardoll DM, Chen L, Sharfman WH, Anders RA, Taube JM, McMiller TL, Xu H, Korman AJ, Jure-Kunkel M, Agrawal S, McDonald D, Kollia GD, Gupta A, Wigginton JM, Sznol M. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, Pitot HC, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Martins R, Eaton K, Chen S, Salay TM, Alaparthy S, Grosso JF, Korman AJ, Parker SM, Agrawal S, Goldberg SM, Pardoll DM, Gupta A, Wigginton JM. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, Ariyan CE, Gordon RA, Reed K, Burke MM, Caldwell A, Kronenberg SA, Agunwamba BU, Zhang X, Lowy I, Inzunza HD, Feely W, Horak CE, Hong Q, Korman AJ, Wigginton JM, Gupta A, Sznol M. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sham NO, Zhao L, Zhu Z, Roy TM, Xiao H, Bai Q, Wakefield MR, Fang Y. Immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: current agents and potential molecular targets. Anticancer Res. 2022;42(7):3275–3284. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, Chau I, Ernstoff MS, Gardner JM, Ginex P, Hallmeyer S, Holter Chakrabarty J, Leighl NB, Mammen JS, McDermott DF, Naing A, Nastoupil LJ, Phillips T, Porter LD, Puzanov I, Reichner CA, Santomasso BD, Seigel C, Spira A, Suarez-Almazor ME, Wang Y, Weber JS, Wolchok JD, Thompson JA, National Comprehensive Cancer Network Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1714–1768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Magid AF. Inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway can mobilize the immune system: an innovative potential therapy for cancer and chronic infections. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6(5):489–490. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aungst BJ. Optimizing oral bioavailability in drug discovery: an overview of design and testing strategies and formulation options. J Pharm Sci. 2017;106(4):921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conner KP, Devanaboyina SC, Thomas VA, Rock DA. The bio-distribution of therapeutic proteins: mechanism, implications for pharmacokinetics, and methods of evaluation. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;212:107574. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koblish HK, Wu L, Wang LS, Liu PCC, Wynn R, Rios-Doria J, Spitz S, Liu H, Volgina A, Zolotarjova N, Kapilashrami K, Behshad E, Covington M, Yang YO, Li J, Diamond S, Soloviev M, O’Hayer K, Rubin S, Kanellopoulou C, Yang G, Rupar M, DiMatteo D, Lin L, Stevens C, Zhang Y, Thekkat P, Geschwindt R, Marando C, Yeleswaram S, Jackson J, Scherle P, Huber R, Yao W, Hollis G. Characterization of INCB086550: a potent and novel small-molecule PD-L1 inhibitor. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(6):1482–1499. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai F, Ji M, Huang L, Wang Y, Xue N, Du T, Dong K, Yao X, Jin J, Feng Z, Chen X. YPD-30, a prodrug of YPD-29B, is an oral small-molecule inhibitor targeting PD-L1 for the treatment of human cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(6):2845–2858. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MAX-10181 given orally to patients with advanced solid tumor. Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/ NCT04122339. [Last accessed on September 16, 2022]

- 12.Wang Y, Liu X, Zou X, Wang S, Luo L, Liu Y, Dong K, Yao X, Li Y, Chen X, Sheng L. Metabolism and interspecies variation of IMMH-010, a programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitor prodrug. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(5):598. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13050598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Custem E, Prenen H, Delafontaine B, Spencer K, Mitchell T, Burris H, Kotecki N, Kristeleit R, Pinato D, Sahebjam S, Graham D, Karasic T, Daniel J, O’Hayer K, Geschwindt R, Piha-Paul S. Phase I study of INCB086550, an oral PD-L1 inhibitor, in immune-checkpoint naïve patients with advanced solid tumors. Abstract 529. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9 (Suppl 2):A1–A1052. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-SITC2021.529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odegard JM, Othman AA, Lin KW, Wang AY, Nazareno J, Yoon OK, Ling J, Lad L, Dunbar PR, Thai D, Ang E, Waldron N, Deva S. Oral PD-L1 inhibitor GS-4224 selectively engages PD-L1 high cells and elicits pharmacodynamic responses in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12(4):101960. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2023-008547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasikumar PG, Sudarshan NS, Adurthi S, Ramachandra RK, Samiulla DS, Lakshminarasimhan A, Ramanathan A, Chandrasekhar T, Dhudashiya AA, Talapati SR, Gowda N, Palakolanu S, Mani J, Srinivasrao B, Joseph D, Kumar N, Nair R, Atreya HS, Gowda N, Ramachandra M. PD-1 derived CA-170 is an oral immune checkpoint inhibitor that exhibits preclinical anti-tumor efficacy. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):699. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akiyama Y, Ashizawa T, Iizuka A, Ando T, Ishikawa Y, Kondou R, Miyata H, Maeda C, Kanematsu A, Sugino T, Yamaguchi K. Development of novel small antitumor compounds inhibiting PD-1/PD-L1 binding. Anticancer Res. 2022;42(11):5233–5247. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.16030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashizawa T, Iizuka A, Tanaka E, Kondou R, Miyata H, Maeda C, Sugino T, Yamaguchi K, Ando T, Ishikawa Y, Ito M, Akiyama Y. Antitumor activity of the PD-1/PD-L1 binding inhibitor BMS-202 in the humanized MHC-double knockout NOG mouse. Biomed Res. 2019;40(6):243–250. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.40.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyata H, Akiyama Y, Iizuka A, Kondou R, Maeda C, Kanematsu A, Watanabe K, Ashizawa T, Nagashima T, Urakami K, Ohshima K, Kawata T, Muramatsu K, Shiomi A, Terashima M, Sugino T, Notsu A, Mori K, Yamaguchi K. Development of an automatic measurement method for CD8 and PD-1 positive T cells using image analysis software. Anticancer Res. 2022;42(1):419–427. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasikumar PG, Ramachandra M. Small-molecule immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and other emerging checkpoint pathways. BioDrugs. 2018;32(5):481–497. doi: 10.1007/s40259-018-0303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zak KM, Grudnik P, Guzik K, Zieba BJ, Musielak B, Dömling A, Dubin G, Holak TA. Structural basis for small molecule targeting of the programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) Oncotarget. 2016;7(21):30323–30335. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zarganes-Tzitzikas T, Konstantinidou M, Gao Y, Krzemien D, Zak K, Dubin G, Holak TA, Dömling A. Inhibitors of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1): a patent review (2010-2015) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2016;26(9):973–977. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2016.1206527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JJ, Thi EP, Carpio VH, Bi Y, Cole AG, Dorsey BD, Fan K, Harasym T, Iott CL, Kadhim S, Kim JH, Lee ACH, Nguyen D, Paratala BS, Qiu R, White A, Lakshminarasimhan D, Leo C, Suto RK, Rijnbrand R, Tang S, Sofia MJ, Moore CB. Checkpoint inhibition through small molecule-induced internalization of programmed death-ligand 1. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1222. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Yao Z, Wang S, Xie T, Wu G, Zhang H, Zhang P, Wu Y, Yuan H, Sun H. Syntheses, biological evaluations, and mechanistic studies of Benzo[c][1,2,5]oxadiazole derivatives as potent PD-L1 inhibitors with in vivo antitumor activity. J Med Chem. 2021;64(12):8391–8409. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng B, Ren Y, Niu X, Wang W, Wang S, Tu Y, Liu S, Wang J, Yang D, Liao G, Chen J. Discovery of novel resorcinol dibenzyl ethers targeting the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 interaction as potential anticancer agents. J Med Chem. 2020;63(15):8338–8358. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magiera-Mularz K, Kocik J, Musielak B, Plewka J, Sala D, Machula M, Grudnik P, Hajduk M, Czepiel M, Siedlar M, Holak TA, Skalniak L. Human and mouse PD-L1: similar molecular structure, but different druggability profiles. iScience. 2020;24(1):101960. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surmiak E, Magiera-Mularz K, Musielak B, Muszak D, Kocik-Krol J, Kitel R, Plewka J, Holak TA, Skalniak L. PD-L1 inhibitors: Different classes, activities, and mechanisms of action. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11797. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashizawa T, Iizuka A, Nonomura C, Kondou R, Maeda C, Miyata H, Sugino T, Mitsuya K, Hayashi N, Nakasu Y, Maruyama K, Yamaguchi K, Katano I, Ito M, Akiyama Y. Antitumor effect of programmed death-1 (PD-1) blockade in humanized the NOG-MHC double knockout mouse. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(1):149–158. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He Q, Sun C, Pan Y. Whole-exome sequencing reveals Lewis lung carcinoma is a hypermutated Kras/Nras-mutant cancer with extensive regional mutation clusters in its genome. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):100. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-50703-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Georgiev P, Muise ES, Linn DE, Hinton MC, Wang Y, Cai M, Cadzow L, Wilson DC, Sukumar S, Caniga M, Chen L, Xiao H, Yearley JH, Sriram V, Nebozhyn M, Sathe M, Blumenschein WM, Kerr KS, Hirsch HA, Javaid S, Olow AK, Moy LY, Chiang DY, Loboda A, Cristescu R, Sadekova S, Long BJ, McClanahan TK, Pinheiro EM. Reverse translating molecular determinants of anti-programmed death 1 immunotherapy response in mouse syngeneic tumor models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022;21(3):427–439. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kondou R, Akiyama Y, Iizuka A, Miyata H, Maeda C, Kanematsu A, Watanabe K, Ashizawa T, Nagashima T, Urakami K, Shimoda Y, Ohshima K, Shiomi A, Ohde Y, Terashima M, Uesaka K, Onitsuka T, Nishimura S, Hirashima Y, Hayashi N, Kiyohara Y, Tsubosa Y, Katagiri H, Niwakawa M, Takahashi K, Kashiwagi H, Nakagawa M, Ishida Y, Sugino T, Notsu A, Mori K, Takahashi M, Kenmotsu H, Yamaguchi K. Identification of tumor microenvironment-associated immunological genes as potent prognostic markers in the cancer genome analysis project HOPE. Mol Clin Oncol. 2021;15(5):232. doi: 10.3892/mco.2021.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(6):492–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(25):2500–2501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Li J. Correlation of tumor mutational burden with prognosis and immune infiltration in lung adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1128785. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1128785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niknafs N, Balan A, Cherry C, Hummelink K, Monkhorst K, Shao XM, Belcaid Z, Marrone KA, Murray J, Smith KN, Levy B, Feliciano J, Hann CL, Lam V, Pardoll DM, Karchin R, Seiwert TY, Brahmer JR, Forde PM, Velculescu VE, Anagnostou V. Persistent mutation burden drives sustained anti-tumor immune responses. Nat Med. 2023;29(2):440–449. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02163-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho YA, Lee H, Kim DG, Kim H, Ha SY, Choi YL, Jang KT, Kim KM. PD-L1 expression is significantly associated with tumor mutation burden and microsatellite instability score. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(18):4659. doi: 10.3390/cancers13184659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manca P, Corti F, Intini R, Mazzoli G, Miceli R, Germani MM, Bergamo F, Ambrosini M, Cristarella E, Cerantola R, Boccaccio C, Ricagno G, Ghelardi F, Randon G, Leoncini G, Milione M, Fassan M, Cremolini C, Lonardi S, Pietrantonio F. Tumour mutational burden as a biomarker in patients with mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2023;187:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]