Abstract

Background/Aim

Acute lung injury (ALI) is an important pathological process in acute respiratory distress syndrome; however, feasible and effective treatment strategies for ALI are limited. Recent studies have suggested that stem cell-derived exosomes can ameliorate ALI; however, there remains no consensus on the protocols used, including the route of administration. This study aimed to identify the appropriate route of administration of canine stem cell-derived exosomes (cSC-Exos) in ALI. Lipopolysaccharides were used to induce ALI.

Materials and Methods

Mice with ALI were treated with cSC-Exos by intratracheal instillation or intravenous injection. The efficacy of the route of administration was confirmed by determining the total cell count in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and histopathological changes. The treatment mechanism was confirmed by measuring cytokine levels and immune cell changes in M2 macrophages (CD206+ cells) and regulatory T cells (FOXP+ cells).

Results

When cSC-Exos were injected, inflammation was alleviated, pro-inflammatory cytokine levels were reduced, and FOXP3+ and CD206+ cells were activated. Following intratracheal instillation, an enhanced inflammation-relieving response was observed.

Conclusion

This study compared the effects of stem cell-derived exosomes on alleviating lung inflammation according to injection routes in an ALI mouse model. It was confirmed that direct injection of exosomes into the airway had a greater ability to alleviate lung inflammation than intravenous injection by polarizing M2 macrophages and increasing regulatory T cells.

Keywords: Acute lung injury, dog, exosome, inflammation, stem cell

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a life-threatening condition in which breathing is not performed smoothly because of damage to the capillaries or alveoli in the lungs caused by infection, trauma, or bleeding (1). ALI remains an important cause of mortality in critically ill patients in veterinary medicine, and even the long-term quality of life of patients who survive ALI is negatively affected. Management of ALI in general should focus on early recognition with treatment of the underlying disease and supportive care of the respiratory system. To date, various therapeutic strategies have been applied to treat ALI. However, there is a lack of strong clinical evidence regarding the best approach for these patients in veterinary medicine (2).

Several recent studies have focused on the therapeutic potential of stem cell-derived exosomes (SC-Exos). SC-Exos contain several soluble factors with recovery and regenerative properties that can protect the alveolar epithelium and endothelium from damage. For example, keratinocyte growth factor and angiopoietin-1 secreted by mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), interleukin (IL)-10, and other MSC soluble factors, such as prostaglandin E2, inhibit inflammation. In addition, exosomes are stable, can be stored frozen for a long time without changing their biological activity, and are small; therefore, they reach target organs quickly and avoid interference with microcirculation, and because the surface of exosomes is coated with a phospholipid membrane, various bioactive ingredients, such as proteins, lipids, mRNAs and microRNAs are present. Moreover, they are not easily decomposed by enzymes (3).

Preclinical studies have indicated that SC-Exos have significant healing potential in the regeneration and rehabilitation of several lung diseases via various molecular pathways and by influencing lung tissue target cells, such as immune, endothelial, and epithelial cells. Although substantial preclinical evidence suggests that the application of SC-Exos for ALI/acute respiratory distress syndrome therapy is effective and safe, further studies are required in this field and significant work needs to be conducted to fully determine the potential of SCs-Exos in clinical applications (3).

The exosome administration pathway is closely related to the therapeutic effects of various diseases and affects the biological distribution and rapid removal rate of exosomes in vivo. Therefore, for a successful treatment, it is important to select the most appropriate route of administration for each disease (4). However, further studies are required to determine the optimal route of exosome administration in veterinary field.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the efficient administration route to determine the effects of canine SC-Exos on inflammation and immune responses in a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced mouse model of ALI.

Materials and Methods

Caine stem cell-derived exosomes. Canine CS-Exos (cST-Exos) used in this study were supplied by GNG CELL Co., Ltd. (Seongnam, Republic of Korea). The stem cells and cST-Exos used in this study were characterized, as previously described (5).

Animal procedures. Seventy-five male 7-week-old C57BL/6N mice were purchased from Koatech (Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea), and this study was approved by the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of Ndic Co., Ltd. (Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) and performed in accordance with the Animal Protection Act (approval number: P234100). The mice were reared in a place where temperature, humidity, and illumination were maintained following a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle. The cage and feeder were replaced once a week, and the water bottle was replaced twice a week. They were acclimatized in the animal room for 7 days, and following a 7-day quarantine acclimatization period, their health and suitability for experimentation were confirmed. The animals that showed no abnormalities during the acclimatization period were randomly divided into groups.

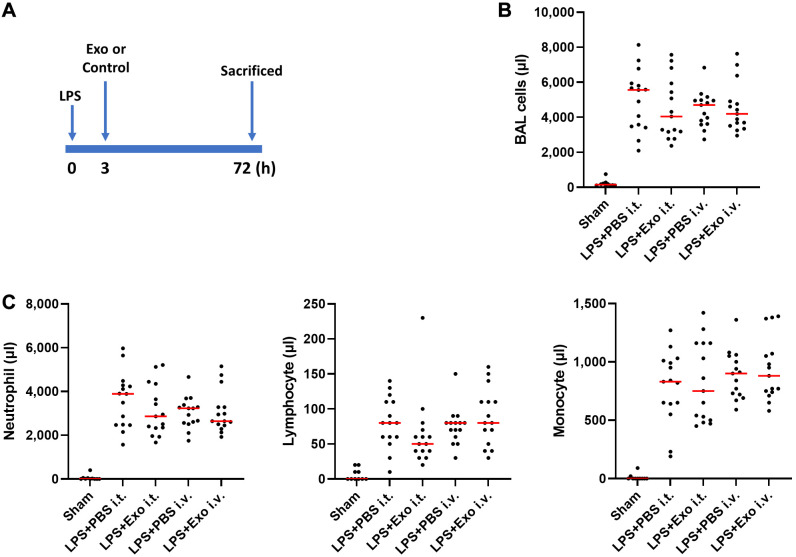

An ALI mouse model was established using LPS as previously described (2). Briefly, the procedures were as follows: ALI was induced by administering LPS (20 mg/kg) directly into the trachea. Three hours after LPS administration, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [PBS intravenous (i.v.) group, n=15; PBS intratracheal (i.t.) group, n=15] and exosomes (Exo i.v. group, n=15; Exo i.t. group, n=15) were intravenously and intratracheally administered in a 0.05 ml volume, depending on the group divided based on route of administration. Autopsy was performed in a non-fasting state 72 h after LPS administration (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome (Exo) administration resulted in a reduction in total cells present in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) in a mouse model of lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). (A) Experimental setup. The mice were subjected to intratracheal (i.t.) administration of LPS, followed by treatment with either Exo or vehicle (Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline) via i.t. and intravenous routes, 3 h post-LPS exposure. (B) BALF cell counts. Total cell count was determined 72 h after injury. (C) Counts of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes in BALF were assessed 72 h after injury. n=10-15 mice per group. Results are presented as means±standard deviations.

For collecting bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (BALF), after incising the tracheal area, 1 ml cold PBS was gently injected into the lung once into the trachea, and the lavage fluid was collected to obtain BALF, the BALF solution was centrifuged at 4˚C (100×g, 10 min), and the cells in the pellets were resuspended with 500 μl of 1X PBS (6). After floating, blood cells were counted using a CBC analyzer (Mindray BC-5000 Vet, Mindray, Shenzhen, PR China). In the case of the lungs, after extraction, the superior and inferior lobes were snap-frozen for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), and the left lung lobe was fixed in 10% neutral formalin to prepare a slide, which was then used for analysis.

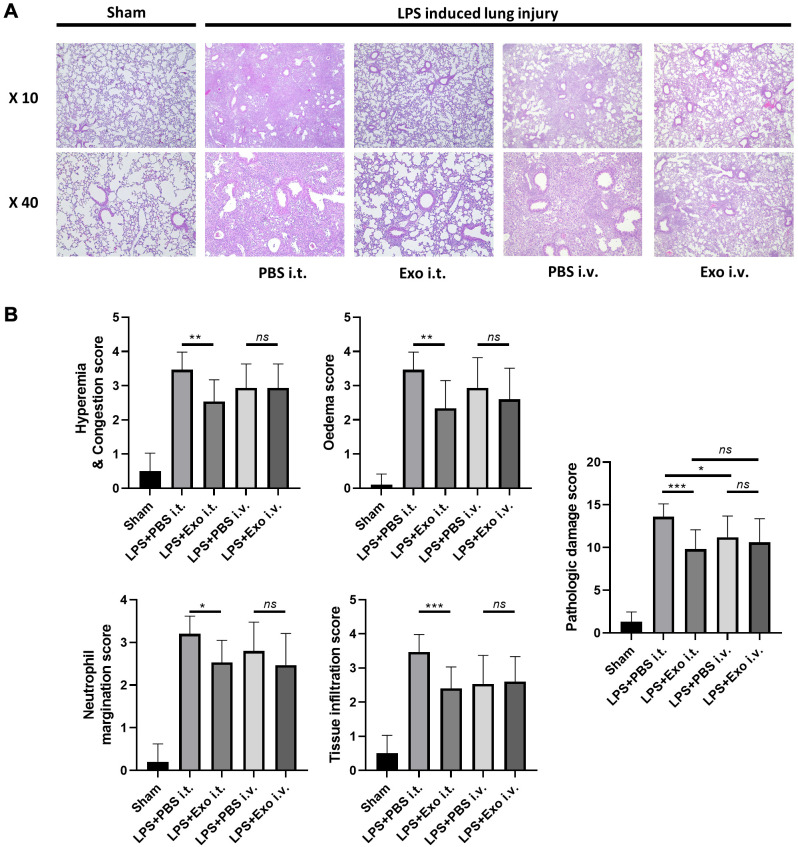

Histological analysis. Following alveolar lavage, the lungs were carefully removed using tweezers, gently extracted, and rinsed in a dish filled with pre-cooled Dulbecco’s PBS. Samples from the right upper pulmonary region were then immersed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for fixation over a period of 24 h, followed by embedding in paraffin and slicing into 5-μm-thick sections. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed according to established protocols, and the resulting pathological changes were observed under a light microscope in a blinded manner. The severity of lung injury was evaluated using a scoring system based on histological features (7), encompassing edema, hyperemia and congestion, neutrophil margination, and tissue infiltration. Each aspect was assigned a score ranging from 0 to 4 points (0, no injury; 1, injury in 25% of the observed field; 2, injury in 50%; 3, injury in 75%; and 4, injury throughout the entire field) (Table I). The cumulative sum of these scores constituted the total lung injury score.

Table I. Criteria for scoring histopathology injury of lung tissue.

RNA extraction, complementary DNA synthesis, and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. RNA was isolated from the mouse lung tissue using the Easy-BLUE Total RNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seoul, Republic of Korea). Subsequently, complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed using the CellScript cDNA Master Mix (CellSafe, Suwon, Republic of Korea), following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The resulting cDNA samples were analyzed in duplicate by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR using AMPIGENE qPCR Green Mix Hi-ROX with SYBR Green Dye (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The mRNA expression levels were standardized relative to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The details of the primer sequences used in this study are presented in Table II.

Table II. Sequences of PCR primers used in this study.

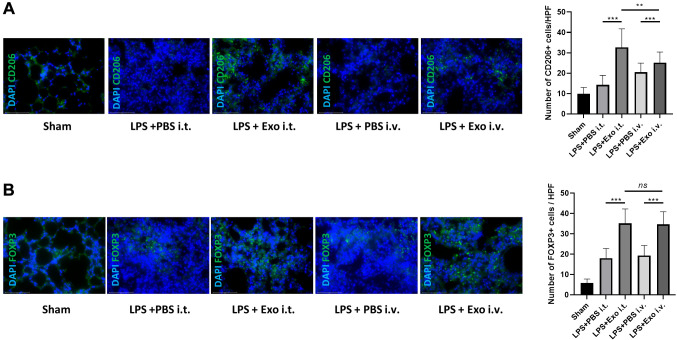

Immunofluorescence analysis. The lung sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, followed by antigen retrieval in 10 mM citrate buffer. Subsequently, the sections were rinsed and blocked with a blocking buffer consisting of 5% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h. Next, the sections were left to incubate overnight at 4˚C with mouse monoclonal fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated FOXP3 (dilution: 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and FITC-conjugated CD206 (dilution: 1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The colon sections were washed thrice. All samples were mounted using Vectashield mounting medium supplemented with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and observed using an EVOS M7000 microscope (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany). Immunoreactive cells were tallied in 20 random fields per group, and the proportions of CD206+ and FOXP3+ cells were computed in colon sections sourced from the same mice.

Statistical analyses. Data are expressed as means±standard deviations. Group means were compared using the t-test and one-way analysis of variance with the GraphPad Prism version 7.01 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

Inflammatory cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. We used an established model to investigate the effects of canine SC-Exos on LPS-induced lung inflammation, depending on the route of administration. Following the administration of exosomes via i.v. or i.t. injection in an acute lung disease model, cellular analysis was performed using BALF. Although not significant, it was confirmed that in the ALI model group injected with exosomes, the median number of total cells was lower compared with that in the control group (LPS+PBS i.t. group vs. LPS+Exo i.t. group, LPS+PBS i.v. group vs. LPS+Exo i.v. group), regardless of the administration route (Figure 1B). A similar trend was observed regarding neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes (LPS+PBS i.t. group vs. LPS+Exo i.t. group, LPS+PBS i.v. group vs. LPS+Exo i.v. group) (Figure 1C).

Histopathology of the lung of a lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury mouse model. In this study, we used H&E staining to assess the pathological changes in lung tissue and evaluate the effect of canine stem cell exosomes on LPS-induced pathological changes in lung tissue depending on the administration route. Hyperemia, congestion, edema, neutrophil margination, and tissue infiltration were evaluated according to scores. In the group intravenously injected with exosomes, a tendency for lung damage to be alleviated was confirmed, but the difference was not significant (LPS+PBS i.v. group vs. LPS+Exo i.v. group). However, when the groups intratracheally injected were compared, significant histological damage relief was confirmed (LPS+PBS i.t. group vs. LPS+Exo i.t. group) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The efficacy of exosomes in mitigating pathological lung effects induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) administration varies depending on the route of administration. (A) Lung sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and histologically examined 72 h after LPS instillation. The representative sections are shown at ×10 and ×40 original magnification. The phosphate-buffered saline group showed normal lung tissue. (B) Lung injury scores, including hyperemia and congestion, edema, neutrophil migration, tissue infiltration, and histological damage scores, were assessed. n=10-15 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; ns: not significant. Results are presented as means±standard deviations.

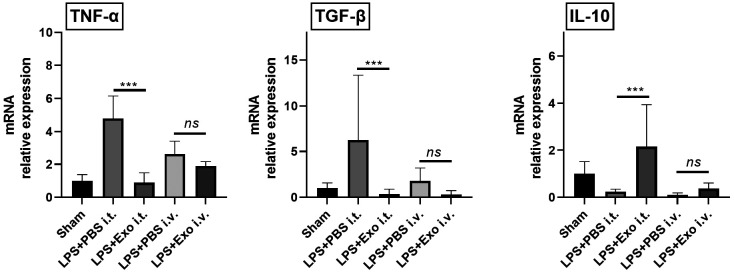

Expression levels of inflammatory cytokines in inflamed lung tissues. The expression levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, tumor growth factor (TGF)-β, and interleukin (IL)-10 were measured in LPS-induced inflamed lung tissues to assess the immunomodulatory capacity of canine stem cell exosomes, depending on the administration route. When comparing the groups intratracheally injected with exosomes (LPS+PBS i.t. group vs. LPS+Exo i.t. group), TNF-α and TGF-β expressions were found to be significantly decreased in the exosome injection group. However, when comparing the groups intravenously injected with exosomes (LPS+PBS i.v. group vs. LPS+Exo i.v. group), a decreasing trend was observed, but this was not statistically significant. Additionally, in the i.t. injection groups (LPS+PBS i.t. group vs. LPS+Exo i.t. group), IL-10 expression σας significantly increased when exosomes were injected. However, when comparing the groups intravenously injected with exosomes (LPS+PBS i.v. group vs. LPS+Exo i.v. group), an increasing trend was observed; however, this was not statistically significant (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in inflammatory cytokine expression according to exosome administration route. n=10-15 mice per group. ***p<0.001; ns: not significant. Results are presented as means±standard deviations.

Exosome intratracheal infusion increased the number of M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells in inflamed lung tissues. To determine whether the increase in the number of M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs) was associated with the route of administration, quantitative immunofluorescence analysis of CD206+ and FOXP3+ cells was performed in lung tissue sections. It was confirmed that in the ALI model group injected with exosomes, the numbers of CD206+ and FOXP3+ cells were significantly higher compared with those in the control group (LPS+PBS i.t. group vs. LPS+Exo i.t. group, LPS+PBS i.v. group vs. LPS+Exo i.v. group), regardless of the administration route. Notably, the LPS+Exo i.t. group had significantly higher number of M2 macrophages compared with the LPS+Exo i.v. group (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells (Tregs) after cST-Exo treatment according to route of administration. (A) The numbers of CD206+ M2 and (B) FOXP+Treg cells in the lungs were determined by immunofluorescence. n=10-15 mice per group. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; ns: not significant. Results are presented as means±standard deviations.

Discussion

Numerous studies have been conducted on the potential of SC-Exos as treatments for various lung diseases, and several methods have been proposed to maximize their therapeutic effects. One study showed that umbilical cord SC-Exos exerted significantly higher lung tropism than any other organ when administered via the jugular vein (8). However, the number of such studies is small, and other reports have argued that administering SC-Exos directly to target organs may have greater benefits. Therefore, in this clinical trial, we examined the treatment basis for efficient cST-Exo administration by comparing the therapeutic effects of i.t. instillation, which is direct administration to the affected area, and i.v. administration, which is a systemic administration. In particular, the feasibility of the administration route was evaluated by confirming lung inflammation by examining histological changes, inflammatory cytokine levels, and immune cell changes according to the administration route of cST-Exos.

Interestingly, we found that cST-Exos alleviated lung inflammation and regulated pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines more by tracheal instillation than by i.v. injection in an ALI model. The first and fundamental step of the immune system is to recognize dangerous stimuli and then react to factors that threaten the organism. The innate immune system is the most responsive, followed by lymphocyte activation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are important in mediating immune responses and play an important role in regulating the immune system (9-12). Among the pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α triggers the expression of vascular endothelial cells and enhances leukocyte adhesion molecules that stimulate immune cell infiltration (10). In our study, when exosomes were administered to LPS-induced ALI mice, the expression level of TNF-α was significantly lower compared with that in the control group, suggesting that treatment with exosomes in an acute lung inflammation model promotes an early inflammatory response. IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine, a set of immunomodulatory molecules that regulate pro-inflammatory cytokine responses, helping to stop or alleviate inflammation and preventing excessive immune responses that can lead to tissue damage (13). Our results showed that when exosomes were intratracheally administered to LPS-induced ALI mice, the level of IL-10 was higher compared with that in the control group, which can be understood to contribute to the regulation of the immune response. TGF-β, a multifunctional cytokine, exists in three isoforms. Of these, TGF-β is the most abundant, the most upregulated in response to tissue injury, and the most implicated in fibrosis (14,15). In a previous study, it was found that TGF-β level was increased in patients with ALI (14). The significance of finding active TGF-β in the lung in ALI is twofold. First, it suggests that the early increase in collagen turnover in ALI, as indicated by elevated procollagen levels, may be driven by activation of latent TGF-β. Second, active TGF-β may affect epithelial permeability, enhancing pulmonary edema, as was demonstrated in a murine model of ALI (16). Interestingly, through this study, it was confirmed that when cST-Exos were administered, TGF-β level, which had increased due to lung inflammation, was reduced, and when cST-Exos were intratracheally administered, TGF-β level was lower than when intravascularly administered.

These cytokines are regulated by immune cells, such as macrophages and Tregs. Macrophages play an important role in innate and adaptive immune responses to particles and pathogens in various organ systems, including the lungs. Macrophages are abundant in the lung microenvironment and are mainly found as alveolar and interstitial macrophages. Alveolar macrophages are polarized into M1 and M2 phenotype macrophages, with M1 macrophages playing a pivotal role in the pro-inflammatory response of host defense and M2 macrophages contributing to anti-inflammatory responses and tissue remodeling (17). In particular, M2 macrophages are activated macrophages characterized by the production of cytokines, such as IL-10 (18,19). M2 macrophages promote the proliferation of lung endothelial cells and improve the survival rate of mice with sepsis (20). In our study, the cST-Exo administration group showed significantly higher CD 206+ cells after both i.t. and i.v. administration compared with the control group. In addition, the number of CD 206+ cells was significantly higher when cST-Exos were intratracheally administered compared with i.v. administration. Tregs are important for the maintenance of immune homeostasis and self-tolerance. Tregs play an anti-inflammatory role, and their failure can lead to inflammatory diseases. In several lung diseases, Tregs play an anti-inflammatory role, primarily through contact-dependent inhibition or the release of cytokines (21). The transcription factor Foxp3 is the best-established marker that defines Tregs, particularly in mice. It is believed to play an essential role in initiating inhibitory functions (22). Our study showed that the number of Foxp3+ cells increased significantly following cST-Exo administration. In particular, the number of Foxp3+ cells were significantly higher in the i.t. injection group than in the i.v. injection group. These results suggest that cST-Exo administration is effective in inducing the anti-inflammatory response by increasing the number of M2 macrophages and Tregs, and the anti-inflammatory response is thought to be more effective with i.t. instillation than with i.v. administration.

Study limitations. Standardization of the dosage of ST-Exo was not performed in this study. The biodistribution and cellular uptake of exosomes must be identified to further investigate their half-life, off-target organ accumulation, and surface modifications to minimize non-target cell interactions (23). Additionally, because this study applied cST-Exos to a mouse lung disease model, future studies applying it to dogs with naturally occurring ALI are required to apply it as a treatment.

Conclusion

This study compared the effects of stem cell-derived exosomes on alleviating lung inflammation according to injection routes in an ALI mouse model. By assessing the alleviation of lung inflammation, inflammatory cytokines, and immune cell alterations across different injection routes in an ALI mouse model, we determined that i.t. administration was more effective than i.v. administration in treating ALI. This study provides foundational information that can inform the appropriate cST-Exo administration methods for patients with naturally occurring canine ALI.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00240708).

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to report in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

HNO: Conception, design, analysis, interpretation of data and writing draft. YSK, GHL, JBM, THY, SYK: Analysis and review of this article. JHA: Conception, design, analysis, interpretation of data, project administration and supervision, writing, editing, and revising draft.

References

- 1.Johnson ER, Matthay MA. Acute lung injury: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2010;23(4):243–252. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaspi H, Semo J, Abramov N, Dekel C, Lindborg S, Kern R, Lebovits C, Aricha R. MSC-NTF (NurOwn®) exosomes: a novel therapeutic modality in the mouse LPS-induced ARDS model. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02143-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu B, Chen SS, Liu MZ, Gan CX, Li JQ, Guo GH. Stem cell derived exosomes-based therapy for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: A novel therapeutic strategy. Life Sci. 2020;254:117766. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Bi J, Huang J, Tang Y, Du S, Li P. Exosome: a review of its classification, isolation techniques, storage, diagnostic and targeted therapy applications. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:6917–6934. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S264498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SY, Yoon TH, Na J, Yi SJ, Jin Y, Kim M, Oh TH, Chung TW. Mesenchymal stem cells and extracellular vesicles derived from canine adipose tissue ameliorates inflammation, skin barrier function and pruritus by reducing JAK/STAT signaling in atopic dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4868. doi: 10.3390/ijms23094868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang Y, Zhang S, Li X, Jiang F, Ye Q, Ning W. Follistatin like-1 aggravates silica-induced mouse lung injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):399. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00478-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi ZA, Yu CX, Wu ZC, Chen CL, Tu FP, Wan Y. The effect of FTY720 at different doses and time-points on LPS-induced acute lung injury in rats. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;99:107972. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tieu A, Stewart DJ, Chwastek D, Lansdell C, Burger D, Lalu MM. Biodistribution of mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles administered during acute lung injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14(1):250. doi: 10.1186/s13287-023-03472-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvanová G, Duranková S, Bernasovská J. The role of cytokines and chemokines in the inflammatory response. Polish J Allergol. 2023;10(3):210–219. doi: 10.5114/pja.2023.131708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang JM, An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;45(2):27–37. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kany S, Vollrath JT, Relja B. Cytokines in inflammatory disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(23):6008. doi: 10.3390/ijms20236008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Z, Bozec A, Ramming A, Schett G. Anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15(1):9–17. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa Y, Duru EA, Ameredes BT. Role of IL-10 in the resolution of airway inflammation. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8(5):437–445. doi: 10.2174/156652408785160907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fahy RJ, Lichtenberger F, McKeegan CB, Nuovo GJ, Marsh CB, Wewers MD. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28(4):499–503. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0092OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez IE, Eickelberg O. The impact of TGF-β on lung fibrosis. Proc Am Thor Soc. 2012;9(3):111–116. doi: 10.1513/pats.201203-023AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pittet JF, Griffiths MJ, Geiser T, Kaminski N, Dalton SL, Huang X, Brown LA, Gotwals PJ, Koteliansky VE, Matthay MA, Sheppard D. TGF-beta is a critical mediator of acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(12):1537–1544. doi: 10.1172/JCI11963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JW, Chun W, Lee HJ, Min JH, Kim SM, Seo JY, Ahn KS, Oh SR. The role of macrophages in the development of acute and chronic inflammatory lung diseases. Cells. 2021;10(4):897. doi: 10.3390/cells10040897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu ZJ, Gu Y, Wang CZ, Jin Y, Wen XM, Ma JC, Tang LJ, Mao ZW, Qian J, Lin J. The M2 macrophage marker CD206: a novel prognostic indicator for acute myeloid leukemia. Oncoimmunology. 2019;9(1):1683347. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1683347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Saeed AFUH, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H, Xiao GG, Rao L, Duo Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):207. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen Y, Song J, Wang Y, Chen Z, Zhang L, Yu J, Zhu D, Zhong M. M2 macrophages promote pulmonary endothelial cells regeneration in sepsis-induced acute lung injury. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(7):142. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.02.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin S, Wu H, Wang C, Xiao Z, Xu F. Regulatory T cells and acute lung injury: cytokines, uncontrolled inflammation, and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1545. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299(5609):1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popowski K, Lutz H, Hu S, George A, Dinh PU, Cheng K. Exosome therapeutics for lung regenerative medicine. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9(1):1785161. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2020.1785161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]