Abstract

Patients with lateral lymph node metastasis (LLNM) may experience higher locoregional recurrence rates and poorer prognoses compared to those without LLNM, highlighting the need for effective preoperative stratification to reliably assess risk LLNM. In this study, we collected PTMC samples from Peking Union Medical College Hospital and employed data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry proteomics technique to identify protein profiles in PTMC tissues with and without LLNM. Pseudo temporal analysis and single sample gene set enrichment analysis were conducted in combination with The Cancer Genome Atlas Thyroid Carcinoma for functional coordination analysis and the construction of a prediction model based on random forest. Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) clustering was utilized to classify molecular subtypes of PTMC. Our findings revealed that the differential activation of pathways such as MAPK and PI3K was critical in enhancing the lateral lymph node metastatic potential of PTMC. We successfully screened biomarkers via machine learning and public databases, creating an effective prediction model for metastasis. Additionally, we explored the mechanism of metastasis-associated PTMC subtypes via NMF clustering. These insights into LLNM mechanisms in PTMC may contribute to future biomarker screening and the identification of therapeutic targets.

Keywords: papillary thyroid microcarcinoma, proteomics, lateral lymph node metastasis, biomarker, mass spectrometry

Introduction

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is a common malignant disease of the endocrine system, and its incidence has steadily increased in recent decades.1 Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) is defined as a PTC with a maximum diameter of 10 mm or smaller.2 Although most PTMCs have indolent biological behavior and a favorable prognosis, a proportion of patients have aggressive features, such as lymph node metastasis (LNM), invasion of adjacent organs, and distant metastasis.3,4 According to the neck classification, regional LNM can be divided into central LNM (CLNM) and lateral LNM (LLNM).5 Notably, PTMCs may metastasize to regional lymph nodes even at the early stage, with reported incidences of 24.4–64.1% for CLNM and 1.1–44.5% for LLNM.6,7

Numerous studies have shown that LLNM can increase the risk of locoregional recurrence rates and decrease tumor-free survival rates in patients with PTMC.5,6,8,9 Lateral neck dissection is widely assumed to be recommended for PTMC with LLNM, which is diagnosed via radiological imaging and fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Therefore, the detection of LLNM during primary surgical resection is very important for reducing the reoperation rate and complications related to reoperation. The American Thyroid Association guidelines suggest that ultrasound-guided FNA should be conducted only for suspicious lateral lymph nodes measuring 8–10 mm or larger.10 However, the size of the metastatic lateral lymph node in PTMC is usually less than 10 mm in diameter. The difficulty of performing FNA on such small suspicious lateral lymph nodes contributes to false-negative results, adding additional physical and psychological burdens on patients. Although several studies have proposed several risk factors for LLNM in patients with PTMC, identifying biomarkers that are predictive of LLNM development remains elusive.7,11 To effectively plan the extent of surgical resection and minimize disease burden, more specific and sensitive preoperative biomarkers are needed to improve the risk stratification of PTMC patients with LLNM.

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)–based proteomic analysis has recently emerged as the central focus in tumor biology and is an important complement to genomic and transcriptomic approaches. Proteomics technology has been applied extensively to identify the key biomarkers, elucidate molecular processes, and uncover therapeutic targets involved in LNM in various cancer types.12,13 Although the findings from several published studies have yielded valuable insights into the proteomic profiles of PTMC with LNM, studies exploring the molecular landscape of LLNM in PTMC are rare.14−17

Therefore, we conducted data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) proteomics to elucidate the protein profiles of PTMC with LLNM and to explore the specific biomarkers and underlying mechanisms of LLNM at the protein level via bioinformatics analysis. This study provides novel insight into how PTMC may progress to LLNM and will guide decision-making in PTMC management, leading to improved patient prognosis.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

PTMC patients with LLNM (N = 5) or non-LNM (NLNM, N = 5) were enrolled at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH, Beijing, China) from June 2021 to September 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) maximal diameter of the thyroid nodule ≤10 mm; (2) age ≥18 years; and (3) diagnosis based on ultrasonography, FNA, intraoperative frozing, and postoperative pathology, as confirmed by two pathologists. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) autoimmune, blood, diabetes, or infectious diseases; (2) a history of previous thyroid surgery or other malignancy surgery; and (3) a history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The tissue samples were collected from PTMCs from LLNM patients, including tumor tissues (LLNM-tumor), adjacent normal tissues (LLNM-normal), metastatic lymph node tissues (LLNM-mln), and nonmetastatic lymph node tissues (LLNM-nmln). These patients underwent total thyroidectomy with therapeutic lateral lymph node dissection. Additionally, the tissues samples were collected from PTMCs with NLNM patients, including tumor tissues (NLNM-tumor) and adjacent normal tissues (NLNM-normal). These patients underwent total thyroidectomy with central lymph node dissection. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of PUMCH (no. JS-3267).

Table 1. Clinical and Pathological Characteristics of Subjects in This Studya.

| characteristics | PTMC |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| with NLNM | with LNM | ||

| sample size | 5 | 5 | |

| age at operation [y, X̅ ± S] | 31.40 ± 10.43 | 45.40 ± 16.02 | 1.000 |

| sex [n (%)] | 0.140 | ||

| female | 3 (60.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| male | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

| family history of thyroid disease [n (%)] | 1.000 | ||

| no | 4 (80.0) | 4 (80.0) | |

| yes | 1 (20.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| tumor size [ cm, X̅ ± S] | 0.141 | ||

| ≤0.5 | 5 (100.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

| >0.5 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| clinical LNM [n (%)] | <0.001 | ||

| absent | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| present | 0 (0.0) | 5 (100.0) | |

| pathological subtype [n (%)] | 1.000 | ||

| classic | 5 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | |

| follicular variant | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| classic and follicular variant | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| tumor location [n (%)] | 1.000 | ||

| unifocal | 3 (60.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| multifocal | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

| tumor calcification [n (%)] | 0.545 | ||

| absent | 4 (80.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| present | 1 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

| microscopic capsular invasion [n (%)] | 0.168 | ||

| absent | 3 (60.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| present | 2 (40.0) | 5 (100.0) | |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [n (%)] | 1.000 | ||

| absent | 3 (60.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| present | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Protein Extraction and Quantification

The tissues were cut into sections and washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. The tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen and then digested with lysis buffer (8 M urea in phosphate-buffered saline, 1 × cocktail, and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, pH 8.0), followed by incubation in an ice bath for 30 min at 4 °C. The tissue homogenate was subsequently sonicated and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, and protein quantification was performed with a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each sample was reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol at 56 °C for 30 min and alkylated with 25 mM iodoacetamide in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The proteins were further digested via a trypsin/Lys–C mixture at a protein-to-protease ratio 50:1 and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Each sample was then desalted, dried, and resuspended in 20 μL of 0.1% formic acid for subsequent analysis.

DIA-MS Proteomics Analysis

Proteomic analysis was performed via an EASY-nLC 1200 UHPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Q-Exactive HF (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating in DIA-MS mode. The sample was transferred to a reversed-phase analytical column. The elution gradient was set from 5% to 30% buffer B (0.1% formic acid in 99.9% acetonitrile) over 120 min. An iRT kit was used to align the retention times across all the samples. The parameters were as follows: a full scan was performed at a resolution of 120,000 over a range of from 400 to 1200 m/z; the cycle time was set to 3 s; the automatic gain control target was 3 × 106; the injection time was limited to 100 ms; the charge state screening targeted precursors with a charge state of +2 to +6; and the dynamic exclusion duration was established at 10 s. Based on the precursor m/z distribution of the pooled sample, the number of precursor ions in each isolation window was equalized.

The raw data from the DIA-MS proteomics analysis were processed via Spectronaut Pulsar X with default parameters. For cross-run normalization, local regression was employed to facilitate local normalization. Peptide intensities were quantified by summing the peak areas of the corresponding fragment ions from the MS2 data. The k-nearest neighbors imputation method was implemented to address missing values in protein abundance. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited at Proteome Xchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository with the data set identifier PXD057473.

Data Processing and Differential Expression Analysis

The data used in this study were processed with R software (version 4.1.2). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to downscale the proteomic data of samples from the lymph node metastasis group and the nonlymph node metastasis group and to measure the variability between the two groups using the R package “prcomp” (version 3.6.2). Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) between multiple groups were calculated using the “limma” package (version 3.50.0) of R software.18P values < 0.05 and |log 2 FC| > 1 were adjusted as thresholds for significant differences. The ensemble analysis of DEPs was generated using the R package “VennDiagram” (version 1.7.3). The “ggplot2” package (version 3.4.2) was used to generate volcano plots of the DEPs.

Single Sample Gene Set Enrichment and Pseudotemporal Analysis

All the proteomics data were subjected to single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) using the R package “GSVA” (version 1.42.0) to calculate a functional pathway score for each sample. Furthermore, using the same ssGSEA framework, immune-related pathway scores were assessed for each proteomic sample on the basis of immune-related gene sets from the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) Web site. Differences in pathway enrichment scores between groups were calculated using the “limma” package (version 3.50.0) of R software, with significance thresholds set at P values < 0.05 and |log 2 FC| > 1.

Pseudotemporal analysis (PTA) is a clustering method based on fuzzy c-means clustering, which identifies potential phase sequence or time series patterns in expression profiles and clusters genes with similar patterns to help us understand the dynamic patterns of the expression profiles and their functional connections. PTA was conducted using the R software package Mfuzz (version 2.64.0). To ensure robust analysis, the mean expression values for each protein across the five replicates were calculated and used for subsequent analyses. To identify protein expression trends during the evolution from NLNM-tumor to LLNM-tumor and to LLNM-mln processes, clustering was performed with the number of clusters (K) ranging from 2 to 10. Optimal clustering (K = 6) revealed distinct protein expression trends, allowing us to capture the dynamic regulation of proteins involved in the studied conditions.

Database Processing and Construction of Predictive Models Based on Machine Learning

The gene expression and clinical follow-up data of The Cancer Genome Atlas-Thyroid Carcinoma (TCGA-THCA) cohort were downloaded from the TCGA. The data that did not contain clinical follow-up data and samples without LNM information were removed. After data preprocessing, 413 TCGA-THCA samples were obtained. A random forest dimensionality reduction prediction model was constructed via the “mlr3” package (version 0.13.4) in the TCGA-THCA cohort, which included a total of 479 DEPs (NLNM-tumor vs LLNM-tumor, LLNM-tumor vs LLNM-mln). The target variable was set to the lymph node metastasis status (N0–N1a) to accurately locate central genes related to metastasis. The machine learning task first calculates the importance index of each gene’s contribution to classification through the RANGER learner. The key parameters for the random forest algorithm included 100 trees, mtry set to the square root of the total number of features, a minimum node size of 1, and permutation methods for assessing feature importance. We selected genes with importance values exceeding 0.002 as transfer related genes. A random forest task was subsequently constructed on the basis of the expression levels of selected metastasis-related genes and the status of lymph node metastasis as the target variable.

We then divided the TCGA-THCA queue into a training set and a validation set (2:1 ratio), and the same parameters were used to perform the random forest task again for probability prediction. Using the same parameters, we performed feature screening and key feature prediction on the accuracy of the classification results for samples with a lymph node metastasis status of N0–N1b. The area under the curve (AUC) was used to evaluate the classification performance of the N0–N1a and N0–N1b groups. Correlation analysis of transfer related genes was conducted via the “PEARSON” method using the CORR package (version 0.92).

Non-negative Matrix Factorization Clustering and Functional Enrichment Analysis

NMF is a dimensionality reduction and clustering technique that is suitable for analyzing data with nonnegative values, allowing the decomposed features to maintain their original biological interpretability. NMF performs well in maintaining data sparsity, which enables the decomposed gene or protein features to have a strong correspondence with actual biological functions. We analyzed the underlying mechanisms by which metastasis related genes affect the biological behavior of lymph node metastasis via NMF and the R package “nmf” (version 0.24.0). It was applied to thyroid cancer samples from the TCGA-THCA cohort, and patients in the cohort were classified based on identified metastasis related genes. We adopted the “brunet” standard with 100 iterations and explored the number of clusters from 2 to 6. The optimal number of clusters was determined to be 3 based on co-occurrence correlation.

Gene ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis was subsequently performed using the “clusterProfiler” package (version 4.6.2) and “org.Hs.eg.db” package (version 3.16.0) to identify differentially expressed genes and their related functions among the three identified subtypes. For the GO analysis, a significance threshold of P values < 0.05 was used. Three subtypes of samples were subjected to ssGSEA based on the same method described above to identify activation or inhibition pathways in each subtype, and a heatmap was generated using the R package “pheatmap” (version 1.0.12).

Results

Proteomic Characteristics of Primary and Metastatic Lesions of PTMC

The protein profiles of the tumorous, adjacent, and lymph node tissues were obtained using the DIA-MS proteomics technique. A total of 4619 credible proteins with at least two unique peptides were identified in 10 samples (Supporting Information Table S1). The PCA results indicated that LNM and NLNM could be separated from each other, confirming a significant difference between the two groups (Figure 1A). Compared with those in the NLNM-normal group, there were 59 downregulated proteins and 607 upregulated proteins in the NLNM-tumor group. There were 472 DEPs between the LLNM-tumor and LLNM-normal groups and 666 DEPs between the NLNM-tumor and NLNM-normal groups. A total of 105 DEPs were obtained from the intersection of the two regions (Figure 1B). Compared with those in the LLNM-nmln group, there were 34 downregulated proteins and 104 upregulated proteins in the LLNM-mln group. By taking the intersection of these two data sets (LLNM-tumor vs LLNM-normal and LLNM-mln vs LLNM-nmln), 21 DEPs were screened (Figure 1C). The differential protein distribution patterns of LLNM-tumor vs LLNM-normal, NLNM-tumor vs NLNM-normal, and LLNM-mln vs LLNM-nmln are described via volcano plots (Figure 1D–F).

Figure 1.

General features of PTMC proteomics. (A) Principal component analysis of metastatic vs nonmetastatic groups. (B) Pooled analysis of cancer tissues in metastatic vs nonmetastatic groups. (C) Pooled analysis of cancer tissues in metastatic groups vs metastatic cancer tissues in lymph nodes. (D) Difference volcano plots of LLNM-tumor vs LLNM-normal groups. (E) Difference volcano plots of NLNM-tumor vs NLNM-normal groups. (F) Difference volcano plots of LLNM-mln vs LLNM-nmln groups. (G) Comparison heatmap of classic tumor pathway ssGSEA scores among NLNM-tumor, LLNM-tumor, and LLNM-mln groups. (H) Differences in immune infiltration were calculated based on ssGSEA.

Owing to the presence of LLNM in the AT group, we believe that the AT group had greater metastatic potential than the BT group. A previous high-quality literature review summarized what is currently known about ten classic tumor pathways, including the TP53-PATHWAY, CELL Cycle, WNT-PATHWAY, PI3K-PATHWAY, RAS-PATHWAY, NOTCH, TGF-β HIPPO, HIPPO, MYC, and the MAPK pathway.19 We performed ssGSEA on all samples to calculate pathway scores for each sample and then extracted ten classic tumor-related pathways using regular expression (Supporting Information Table S2). The analysis revealed that nearly all tumor-related pathway scores exhibited a sequential upward trend from the NLNM-tumor to the LLNM-tumor and then to the LLNM-mln. Notably, pathways such as the MAPK, PI3K, and cell cycle pathways showed particularly significant changes (Figure 1G). These findings suggested that a synergistic interaction among multiple tumor-related pathways might increase the metastatic potential of PTMC.

In addition, the ssGSEA algorithm was used to assess variations in immune infiltration across the samples (Supporting Information Table S3). Several immune-related pathways, including activated CD4 T cells, activated CD8 T cells, effector memory CD4 T cells, gamma delta T cells, and type 1 T helper cells, were significantly different (Figure 1H). The overall trend in immune infiltration indicated was greater in the LLNM-mln group, than in the LLNM-tumor group, with the NLNM-tumor group showing the lowest levels. Interestingly, most of these differences in immune infiltration pathways were predominantly associated with functions related to helper T cells.

Pseudotemporal Analysis Reveals Sustained Activation of the MAPK and PI3K Pathways

To further clarify the potential mechanism of increased metastatic potential in PTMC, we conducted a pseudotemporal analysis of the proteins in these three groups. Based on the expression levels of proteins in different groups, we classified the samples into six clusters (Figure 2A). To narrow our focus, we concentrated on the protein sets exhibiting increasing expression across the three groups, which are specifically identified as Cluster 1 (Supporting Information Table S4). The results of GSEA for these proteins revealed significant sequential increases in pathways such as the MAPK, cell cycle checkpoints, and posttranscriptional protein modification pathways (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Proteomics pseudotemporal analysis and pathway protein expression differences. (A) Clustering of protein expression trends based on the Mfuzz package, with better clustering at K = 6. (B) GSEA of Cluster 1. (C) Expression trends of MAPK pathway genes in Cluster 1. (D) Expression trends of PI3K pathway genes in Cluster 1.

Previous studies have reported that activation of the MAPK pathway plays a crucial role in the formation of approximately 90% of PTMCs, making PTMCs a typical solid tumor with a single genetic feature.20 Although most PTMCs are formed by activation of the MAPK pathway caused by BRAF mutations, synergistic changes in multiple pathways during the development of PTMC are still key factors in the differential biological behavior of PTMCs, such as their metastatic characteristics. We collected gene sets related to the MAPK and PI3K pathways on the Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes Web site and mapped them to our proteomic data. We found a very clear and meaningful trend in which the hub genes of multiple MAPK pathways, such as PRKCB, RAP1B, and CDC42, were mostly expressed in LLNM-mln, followed by the AT group, with lower in the BT group. This finding indicated that the activation level of the MAPK pathway may be directly related to the metastatic potential of PTMC (Figure 2C). With respect to the PI3K pathway, the expression of various hub proteins, such as PIK3CD, GNG2, MTOR, and PKN1, which play key roles in this pathway, was significantly elevated in the LLNM-mln group than in the LLNM-tumor and NLNM-tumor groups (Figure 2D). These results demonstrated the varying degrees of activation of the MAPK and PI3K pathways in the transformation of PTMC to metastatic potential.

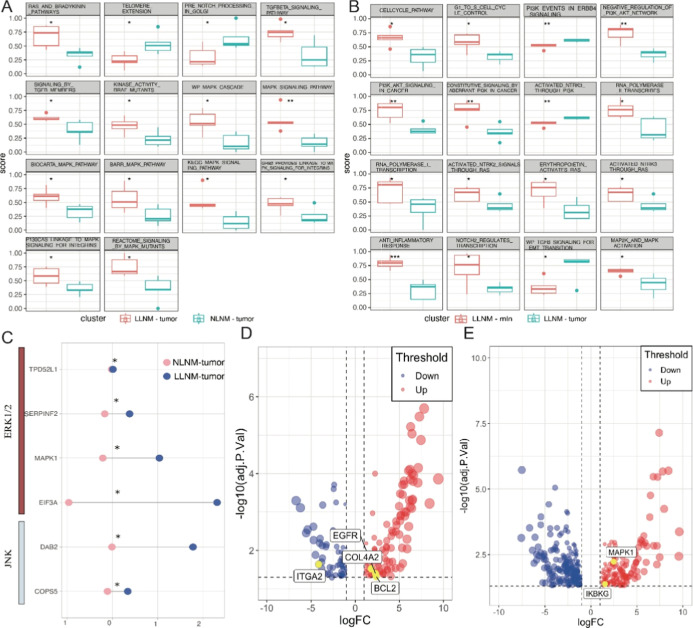

Role of the MAPK and PI3K Pathways in LLNM of PTMC

To further validate the above conclusions, we assessed the pathways with the greatest differences between the two groups (LLNM-tumor vs NLNM-tumor and LLNM-mln vs LLNM-tumor) via the ssGSEA pathway score. One of the most notable features between the LLNM-tumor and NLNM-tumor groups was the activation of multiple MAPK-related pathways, including the MAPK signaling pathway, P130CAS-LINKAGE-TO-MAPK signaling-FOR-INTEGRINS, REACTOME-SIGNALING-BY-MAPK MUTANTS, and WP-MAPK-CASCADE (Figure 3A). Among the differences between the LLNM-mln and LLNM-tumor groups, we observed not only further activation of MAPK-related pathways (such as MAP2K-AND-MAPK-ACTIVATION) but also significant changes in the PI3K and cell cycle-related pathways (Figure 3B). Overall, the PI3K pathway and those involved in cell cycle regulation exhibited high activation levels in LLNM-mln. Compared with the NLNM group, the LNM group exhibited sustained activation of the MAPK pathway (Figure 3B). The process of PTMC metastasizing to lymph nodes involved not only continued activation of the MAPK pathway but also the critical involvement of PI3K and cell cycle-related pathways (Figure 3B). These results indicated that the MAPK pathway played an essential role not only in the formation of PTMC but also in its sustained metastatic potential.

Figure 3.

Pathway expression differences in metastasis and nonmetastasis groups. (A) Multiple MAPK-related pathways were activated in the LLNM-tumor group relative to the NLNM-tumor group. (B) MAPK and PI3K pathways were activated in the LLNM-mln group relative to the LLNM-tumor group. (C) Expression of MAPK subfamily hub proteins in the differential proteins. (D) Expression of MAPK pathway hub proteins in the differential proteins uniquely present in the LLNM-tumor vs LLNM-normal relative to the NLNM-tumor vs NLNM-normal. Pathway hub proteins. (E) The expression of PI3K pathway hub proteins is uniquely present in LLNM-mln vs LLNM-nmln differential proteins relative to LLNM-tumor vs LLNM-normal. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The members of the MAPK family are composed mainly of the ERK1/2, p38, JNK, and ERK5 subfamilies.21 These pathways have different functions in cells. For example, the most extensively studied ERK1/2 pathway is activated by the Raf kinase EGFR, which binds to downstream MEK1/2 and activates ERK1/2. Activated ERK1/2 can continue to phosphorylate transcription factors such as ELK1, ETS, FOS, JUN, MYC, and SP1, inducing the expression of genes related to the cell cycle and proliferation. This pathway is involved mainly in malignant tumor proliferation and metastasis. Our study found that compared with the NLNM group, the p38 and ERK5 subfamilies showed no significant differences. Concurrently, TPD52L1, SERPINF2, MAPK1, EIF3A in the ERK1/2 pathway, and DAB2 and COPS5 in the JNK pathway were significantly upregulated in the LNM group (Figure 3C). Based on the DEPs among the groups (LLNM-tumor vs LLNM-normal and NLNM-tumor vs NLNM-normal), we screened for unique differential proteins in the former group to identify MAPK-related proteins that play a unique role in the LNM group. The results revealed that MAPK family genes (EGFR, COL4A2, and BCL2) were significantly upregulated in the metastatic PTMC group compared with adjacent tissues (NLNM-tumor vs NLNM-normal). Moreover, there were no significant changes in the NLNM group compared with adjacent tissues (LLNM-tumor vs LLNM-normal) (Figure 3D). Similarly, the expression of PI3K pathway genes (MAPK1 and IKBKG) was significantly increased in patients with lymph node metastatic carcinoma, whereas there was no significant change in patients with PTMC with LNM (Figure 3E). This result clarified the overall trend of pathway changes and hub protein expression changes within the metastatic potential of PTMC.

Random Forest Algorithm-Based Screening of Metastasis-Associated Genes and Construction of Predictive Models

To accurately identify the genes that might play crucial roles in the process of metastatic progression and to construct a metastasis prediction model, the samples from the TCGA-THCA data set were filtered based on the status of the lymph nodes, including the N0, N1a, and N1b classifications. We subsequently validated the DEPs identified in the NLNM-tumor, LLNM-tumor, and LLNM-mln groups. Employing the random forest algorithm, we calculated and ranked the importance values of these DEPs in classifying the N0 and N1a samples. The five proteins with the highest importance values (SLC34A2, FN1, KRT19, TMEM38A, and ANXA1) were identified (Figure 4A). These five hub proteins were then utilized to construct a random forest prediction model (Supporting Information Figure S1A). We randomly divided N0 and N1a samples from the TCGA-THCA cohort into training and validation sets at a 2:1 ratio. In the training set, these five genes demonstrated high classification efficiency (Figure 4B). The five-gene model also performed well in the validation set, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.823 for predicting CLNM (Figure 4C). The accuracy of the model is 0.78, precision is 0.96, recall is 0.78, F1 Score is 0.86, OOB-Error is 0.22 (Supporting Information Figure S1B–D).

Figure 4.

Random forest algorithm-based screening of metastasis-associated genes and constructing of predictive models. (A) Metastasis-associated proteins in the N0–N1a group, with importance greater than 0.002 as the threshold. (B) The five-gene model with high predictive efficacy in the N0–N1a group training set. (C) ROC of the model in the N0–N1a group validation set. (D) N0–N1b group of metastasis-associated proteins with importance greater than 0.002 as the threshold. (E) The five-gene model with high prediction efficacy in the training set of the N0–N1b group. (F) ROC of this model in the validation set of the N0–N1b group. (G) Expression differences of the nine metastasis-associated genes in N0, N1a, and N1b.

Next, the same methodology and threshold were applied to screen the N0 and N1b groups, identifying five additional proteins (FN1, OGDHL, LGALS3, MFGE8, and COL8A1, Supporting Information Figure S2A). Notably, FN1 was significant in classifying both transition states (Figure 4D). The five-gene model effectively distinguished the N0 and N1b samples in the training set (Figure 4E). In the validation set, the prediction performance reached an AUC of 0.821 (Figure 4F). Meanwhile, multiple classification performance indicators also showed good performance of the model (Accuracy: 0.81, Precision: 0.95, Recall: 0.83, F1 Score: 0.88, OOB-Error: 0.19, Supporting Information Figure S1B–D). We also demonstrated the differential expression levels of these nine genes, revealing that TMEM38A and OGDHL presented relatively high expression levels in PTMC without LNM. In contrast, the remaining seven genes were significantly upregulated in the LNM group (Figure 4G). These results suggested that the nine metastasis-associated genes might play important roles in the metastasis of PTMC.

NMF Clustering of Metastasis-Related Hub Genes Reveals Potential Mechanisms of Intergroup Metastasis

To further investigate the intrinsic relationships among these genes, we conducted a correlation analysis of the nine metastasis-associated genes (Figure 5A,B). SLC34A2 and COL8A1 were highly correlated with FN1, with values of 0.72 and 0.57, respectively (Figure 5A,B). These findings suggested that these three genes might influence the biological behaviors of PTMC to some extent through synergistic effects. Next, we performed NMF clustering of the TCGA-THCA cohort on the basis of these nine metastasis-related genes. By utilizing cophenetic and other metrics, we determined that the optimal number of clusters was three (Figure 5C and Supporting Information Table S5). The C1 subtype had the highest proportion of NLNM, whereas both N1a and N1b had relatively high proportions in the C3 subtype (Figure 5D). The functional differences among the three PTMC subgroups were explored. The GO analysis of the differentially expressed genes across these clusters revealed significant enrichment in various immune-related functions, including the production of molecular immune mediators, the humoral immune response, and the regulation of B–cell activation (Figure 5E). In terms of molecular functions, we observed enrichment in antibody binding, immunoglobulin receptor binding, and several signaling pathways (Figure 5F). Additionally, the cellular components associated with these pathways included immunoglobulin complexes and cell–cell junctions (Figure 5G). The key distinctions among the three subgroups were centered primarily on activating B-cell immune responses and immunoglobulin binding.

Figure 5.

New PTMC subtypes and mechanism exploration based on metastasis-related genes. (A,B) Correlation analysis of metastasis-related genes in the two 5-gene models. (C) NMF clustering of TCGA-THCA samples based on the nine metastasis-related genes, and the clustering was the most stable at K = 3. (D) Proportion of different LN metastasis states in the new PTMC subtypes. (E–G) GO analysis of the differential expression genes among the three subtypes. (H) GSEA of differentially expressed genes among the three subtypes. (I) The 30 pathways with the greatest differences among the three subtypes. (J) Significant differences in immune infiltration among the three subtypes.

The GSEA of the differential genes among the three subtypes highlighted the notable role of RHO GTPase, which was distinct across the groups (Figure 5H). We further identified the 30 pathways with the most significant differences in ssGSEA pathway scores among the three PTMC subtypes (Figure 5I). Most of these pathways were highly activated in the C3 subtype and less expressed in the C1 subtype, encompassing various cellular functional pathways related to apoptosis, autophagy, signaling, and immunity. Interestingly, some pathways, such as the RIOCARTA CHRERP pathway, which is linked to glycogen metabolism, displayed the opposite trend. Given the significant differences in immune profiles revealed by the functional enrichment analysis, we analyzed the variations in 28 immune-related pathways among the three subtypes via ssGSEA. Remarkably, almost all immune pathways exhibited a consistent trend of sequential elevation from C1 to C2 to C3, including pathways related to cytotoxic T lymphocytes, helper T cells, B cells, and nonspecific immunity (Figure 5J). These findings suggested that the functional roles of the nine metastasis-related genes were closely linked to varying degrees of immune activation.

Discussion

Compared with those in other malignancies, the functional pathways in PTMC are relatively simple.22,23 Constitutive stimulation of MAPK signaling caused by BRAF mutations is the initiating factor for most PTMCs.24 Moreover, LNM is a common event in PTMC and the surgical approach and postoperative treatment options for patients with PTMC need to be determined.25,26 Defining the type of PTMC with a potential propensity to metastasize before the occurrence of a definitive metastatic event is important. However, the currently identified genetic alterations in PTMC cannot distinguish tumors with aggressive features.27 Functional alterations in metastasis involve the synergistic action of multiple pathways. The advent of proteomics technology has largely compensated for the high throughput of protein alterations in different states of PTMC. Proteomic techniques have been used to clarify the proteomic differences in PTMC.28−31 However, further studies on LLNM in PTMC are still needed to clarify which pathways and proteins play key roles in transforming primary to metastatic PTMC.

In this study, we used a DIA-MS proteomic technique to explore the PTMC tissue with and without LLNM from our center. For the 4680 protein expression data obtained, we performed a comprehensive analysis to identify the key pathways and proteins responsible for the increased metastatic potential of PTMC. Activation of the MAPK pathway is a key event in initiating PTMC.32 Our results revealed that sustained activation of this pathway not only affected in the formation of PTMC but might also play a key role in the process of increased metastatic potential. This pathway functions mainly as part of the hub proteins of the ERK1/2 and JNK subfamilies, which promote the progression of PTMC by regulating the proliferative behavior of cells. Another interesting phenomenon was that the PI3K-related pathway was significantly upregulated during the metastasis of tumor tissues to lymph nodes. Some of the key effectors of the PI3K pathway are enriched in anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC).33,34 In ATC, a notable genetic alteration is the trend of altered expression of PI3K pathway effectors in specific combinations with MAPK activation drivers.35 Our findings demonstrated a similar trend in PTMC during metastasis to the lymph nodes. These findings led to the speculation that the protein alterations associated with the metastatic progression of PTMC were similar to those associated with ATC, even though these two types of thyroid cancer exhibited distinctly different biological behaviors. In our previous study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms of CLNM in PTMC through proteomic analysis, particularly how sex differences affect the occurrence of LNM.14 We found that metastasis-related DEPs might also promote tumor progression by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Therefore, we speculated that the PI3K-related pathway was likely one of the key mechanisms mediating LNM in PTMC.

Conversely, we performed machine learning downscaling of key proteins against metastatic phenotypes in public databases to identify biomarkers that play a key role in the metastatic process. Our results showed that the five-gene metastasis prediction model had good predictive performance (AUC > 0.82) in the validation set for CLNM and LLNM. Based on the IMPORTANCE metrics, FN1, SLC43A2, and OGDHL were considered to play key roles in the metastatic process. The role of FN1 in thyroid cancer has been demonstrated; i.e., TGM2 can transcriptionally activate FN1 by promoting nuclear factor κB p65 nuclear translocation, which ultimately promotes the invasion and metastasis of PTMC.36 Moreover, FN1 was found to be associated with immune infiltration in the microenvironment of thyroid cancer, and promoter hypermethylation of FN1 may be a potential mechanism by which it regulates the infiltration of M2 macrophages and resting memory CD4+ T cells.37 Another key gene, SLC34A2, was found to bind to the actin-binding repeat structural domain of corticotropin, which induces the formation of invasive pseudopods in tumor cells in PTC, thereby increasing the metastatic potential. Moreover, the major signaling pathway downstream of SLC34A2 regulation of cell growth is the PI3K/AKT pathway, which is consistent with our results above. To some extent, the roles of FN1 and SLC43A2 in thyroid cancer have been preliminarily clarified. However, more importantly, we have attempted to combine these genes to comprehensively predict LNM and have achieved good results. Conversely, the high correlation between these two genes implies a potential synergistic effect, which has not yet been reported in the above-mentioned report. Therefore, one of the next steps is to clarify its role in synergistically promoting the LNM process of PTMC. In contrast, OGDHL was found to be associated with PTMC survival only via bioinformatics analysis.38 The mechanism of these genes in metastasis merits further exploration.

We explored the genes included in the predictive model. Clustering of the PTMC samples based on these genes revealed substantial differences in immune infiltration among the 3 PTMC subtypes. More PTMC with LNM was present in the C3 subtype, which had highly activated immune pathways. In contrast, the C1 subtype with lower immune infiltration had the lowest percentage of LNM. During LNM in differentiated thyroid cancer, immune escape pathways are suppressed, and the metastatic microenvironment is characterized by a favorable antitumor immune response.39 Our results consistently revealed that various immune cells, including those involved in nonspecific and specific immunity (B cells, CD4+ T cells, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes), were infiltrated with increased infiltration in C3, a subtype with a high percentage of LN metastasis. Further research is needed to investigate the mechanism underlying the relationship between immune infiltration and the metastasis characteristics in the PTMC microenvironment.

Conclusion

On the basis of proteomics technology, we comprehensively demonstrated the biological pathway alterations that occurred during PTMC metastasis. Persistent activation of MAPK with PI3K is a key factor of LLNM in PTMC. A predictive model of LNM in PTMC was constructed via machine learning, which exhibited high predictive efficacy and identified a series of valuable biomarkers. We believe that the results of this study are significant for exploring the mechanism of LN metastasis in patients with PTMC.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the helpful suggestion from our team members.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its Supporting Information files. The corresponding author can be contacted to request the raw data.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jproteome.4c00737.

Figure S1: Performance indicators of N0–N1a prediction model. (A) The details of the random forest model with 5 features constructed based on the N0 and N1a samples of TCGA-THCA. (B) PR curve of the random forest. (C,D) FPR and accuracy across all possible thresholds. Figure S2: Performance indicators of N0–N1b prediction model. (A) The details of the random forest model with 5 features constructed based on the N0 and N1b samples of TCGA-THCA. (B) PR curve of the random forest. (C,D) FPR and accuracy across all possible thresholds (PDF)

Table S1: Protein profiles of tumors, adjacent tissues, and lymph node tissues obtained using DIA-MS proteomics technology (XLSX)

Table S2: Pathway scores for all samples calculated based on ssGSEA (XLSX)

Table S3: Immune infiltration score of all samples calculated based on ssGSEA (XLSX)

Table S4: The pseudo temporal analysis identified the protein sets whose expression levels increased sequentially in NLNM tumor, LLNM tumor, and LLNM mln (XLSX)

Table S5: Non-negative matrix factorization identified the optimal clustering information based on metastasis-related genes (XLSX)

Author Contributions

§ Q.Z., Z.C., and Y.W. have made equal contributions to this work and share the first authorship. Qiyao Zhang: Data curation, Writing—Original draft. Zhen Cao: Conceptualization, Writing—Reviewing and Editing, Methodology. Yuanyang Wang: Investigation. Hao Wu: preparation, Software. Ziwen Liu: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration. Zejian Zhang: Supervision, Validation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 82172727) and the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (no. 7202164).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (no. JS3267). All patients have signed informed consent forms.

Notes

Consent for publication: All authors have approved the final manuscript for publication.

This paper was published November 27, 2024, with an error in the TOC/Abstract. The corrected version was reposted December 3, 2024.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lim H.; Devesa S. S.; Sosa J. A.; et al. Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 1974–2013. JAMA 2017, 317, 1338–1348. 10.1001/jama.2017.2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberger J.; Marienhagen J.; Agha A.; et al. Papillary microcarcinoma and papillary cancer of the thyroid < or = 1 cm: modified definition of the WHO and the therapeutic dilemma. Nuklearmedizin 2007, 46, 115–120. 10.1160/nukmed-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. S.; Lee J. S.; Yun H. J.; et al. Aggressive Subtypes of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Smaller Than 1 cm. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 1370–1375. 10.1210/clinem/dgac739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristos A.; Do K.; Tsang V. H.; et al. Outcomes of Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma Presenting with Palpable Lateral Lymphadenopathy. Thyroid 2022, 32, 1086–1093. 10.1089/thy.2022.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D. Z.; Qu N.; Shi R. L.; et al. Risk prediction and clinical model building for lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 5307–5316. 10.2147/OTT.S107913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan J.; Chen Z.; Chen S.; et al. Lateral lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a study of 5241 follow-up patients. Endocrine 2024, 83, 414–421. 10.1007/s12020-023-03486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Xu L.; Wang J. Clinical predictors of lymph node metastasis and survival rate in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: analysis of 3607 patients at a single institution. J. Surg. Res. 2018, 221, 128–134. 10.1016/j.jss.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back K.; Kim J. S.; Kim J. H.; et al. Superior Located Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma is a Risk Factor for Lateral Lymph Node Metastasis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 3992–4001. 10.1245/s10434-019-07587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. J.; Moon J. H.; Lee E. K.; et al. Active Surveillance for Low-Risk Thyroid Cancers: A Review of Current Practice Guidelines. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 39, 47–60. 10.3803/EnM.2024.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen B. R.; Alexander E. K.; Bible K. C.; et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue S.; Han Z.; Lu Q.; et al. Clinical and Ultrasonic Risk Factors for Lateral Lymph Node Metastasis in Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 436. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z.; Wang N.; Ji N.; et al. Proteomics technologies for cancer liquid biopsies. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 53. 10.1186/s12943-022-01526-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusinow D. P.; Szpyt J.; Ghandi M.; Rose C. M.; McDonald E. R. III; Kalocsay M.; Jané-Valbuena J.; Gelfand E.; Schweppe D. K.; Jedrychowski M.; et al. Quantitative Proteomics of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Cell 2020, 180, 387–402.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z.; Zhang Z.; Tang X.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of tissue proteomics in patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma uncovers the underlying mechanism of lymph node metastasis and its significant sex disparities. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 887977. 10.3389/fonc.2022.887977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S.; Bao W.; Yang Y. T.; et al. Proteomic analysis of the papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Ann. Endocrinol. 2019, 80, 293–300. 10.1016/j.ando.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matovinovic F.; Novak R.; Hrkac S.; et al. In search of new stratification strategies: tissue proteomic profiling of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma in patients with localized disease and lateral neck metastases. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 17405–17417. 10.1007/s00432-023-05452-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Mi L.; Ran B.; et al. Identification of potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) based on TMT-labeled LC-MS/MS and machine learning. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2023, 46, 1131–1143. 10.1007/s40618-022-01960-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie M. E.; Phipson B.; Wu D.; et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vega F.; Mina M.; Armenia J.; Chatila W. K.; Luna A.; La K. C.; Dimitriadoy S.; Liu D. L.; Kantheti H. S.; Saghafinia S.; et al. Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell 2018, 173, 321–337. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romitti M.; Ceolin L.; Siqueira D. R.; et al. Signaling pathways in follicular cell-derived thyroid carcinomas (review). Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 42, 19–28. 10.3892/ijo.2012.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks H. M.; Nassar V. L.; Lund J.; et al. The effects of Aurora Kinase inhibition on thyroid cancer growth and sensitivity to MAPK-directed therapies. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2024, 25, 2332000. 10.1080/15384047.2024.2332000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Jimenez F.; Muinos F.; Sentis I.; et al. A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 555–572. 10.1038/s41568-020-0290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. M.; Shih J.; Ha G.; Gao G. F.; Zhang X.; Berger A. C.; Schumacher S. E.; Wang C.; Hu H.; Liu J.; et al. Genomic and Functional Approaches to Understanding Cancer Aneuploidy. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 676–689.e3. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal N.; Akbani R.; Aksoy B.; Ally A.; Arachchi H.; Asa S.; Auman J.; Balasundaram M.; Balu S.; Baylin S.; et al. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell 2014, 159, 676–690. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulever A.; Pitoia F. Thirty years of active surveillance for low-risk thyroid cancer, lessons learned and future directions. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2024, 25, 65–78. 10.1007/s11154-023-09844-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. W.; Lang B. H. H.; McLeod D. S. A.; et al. Thyroid cancer. Lancet 2023, 401, 1531–1544. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00020-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.; Kwon C. H.; Kim B. H. The role of the tumor microenvironment in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma nodal metastasis. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2024, 31, e240040 10.1530/ERC-24-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damante G.; Scaloni A.; Tell G. Thyroid tumors: novel insights from proteomic studies. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2009, 6, 363–376. 10.1586/epr.09.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ucal Y.; Ozpinar A. Proteomics in thyroid cancer and other thyroid-related diseases: A review of the literature. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2020, 1868, 140510. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2020.140510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofiadis A.; Becker S.; Hellman U.; et al. Proteomic profiling of follicular and papillary thyroid tumors. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 166, 657–667. 10.1530/EJE-11-0856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho M.; Capela J.; Anjo S. I.; et al. Proteomics Reveals mRNA Regulation and the Action of Annexins in Thyroid Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14542. 10.3390/ijms241914542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kure S.; Wada R.; Naito Z. Relationship between genetic alterations and clinicopathological characteristics of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2019, 52, 181–186. 10.1007/s00795-019-00217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rostan G.; Costa A. M.; Pereira-Castro I.; et al. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in anaplastic thyroid cancer. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 10199–10207. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricarte-Filho J. C.; Ryder M.; Chitale D. A.; et al. Mutational profile of advanced primary and metastatic radioactive iodine-refractory thyroid cancers reveals distinct pathogenetic roles for BRAF, PIK3CA, and AKT1. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 4885–4893. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa I.; Ibrahimpasic T.; Boucai L.; et al. Genomic and transcriptomic hallmarks of poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 126, 1052–1066. 10.1172/JCI85271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W.; Qin Y.; Wang Z.; et al. The NEAT1_2/miR-491 Axis Modulates Papillary Thyroid Cancer Invasion and Metastasis Through TGM2/NFkappab/FN1 Signaling. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 610547. 10.3389/fonc.2021.610547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Q. S.; Huang T.; Li L. F.; et al. Over-Expression and Prognostic Significance of FN1, Correlating With Immune Infiltrates in Thyroid Cancer. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 812278. 10.3389/fmed.2021.812278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao M.; Huang R. Z.; Zheng J.; et al. OGDHL closely associates with tumor microenvironment and can serve as a prognostic biomarker for papillary thyroid cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 728–736. 10.1002/cam4.3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha L. L.; Nonogaki S.; Soares F. A.; et al. Immune Escape Mechanism is Impaired in the Microenvironment of Thyroid Lymph Node Metastasis. Endocr. Pathol. 2017, 28, 369–372. 10.1007/s12022-017-9495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its Supporting Information files. The corresponding author can be contacted to request the raw data.