Abstract

Objective(s)

To evaluate the otolaryngology surgical capacity in Harare, Zimbabwe by analyzing procedural volumes across four hospitals, one private and three public, from 2019 to 2022.

Methods

A retrospective review of hand‐written surgical case logs was conducted at Harare Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Institute (HEENT), Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals (PGH), Sally Mugabe Children's Hospital (SMCH), and Sally Mugabe Adult's Hospital (SMAH). Patient age and surgical intervention for all otolaryngology surgeries performed in the operating room from 2019 to 2022 were recorded. Procedures were categorized into six groups: head and neck malignancy, laryngeal surgery, oropharyngeal surgery, otologic surgery, rhinology/sinus surgery, and other. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to identify trends in surgical volume and types of procedures across hospitals.

Results

A total of 2626 procedures were recorded: 1470 at HEENT, 377 at PGH, 625 at SMCH, and 154 at SMAH. Of these, 39.5% were performed on pediatric patients and 60.5% on adult patients. The most common procedures were adenotonsillectomy/adenoidectomy/tonsillectomy (38.9%), diagnostic endoscopies (10.4%), and endoscopic sinus surgery (8.3%). HEENT performed the highest volume and widest range of procedures. HEENT had higher surgical volumes across all groups of procedure, except for laryngeal surgery.

Conclusion

This study found disparities in otolaryngology surgical capacity between a private hospital, HEENT, and three public tertiary hospitals—SMCH, SMAH, and PGH, the largest hospital in the country—in Harare, Zimbabwe. Additionally, it highlights areas for targeted interventions in capacity building. This study establishes a foundation for understanding otolaryngologic surgical capacity in the country, supporting international collaboration, guiding future research, and serving as a model for similar assessments in other LMICs.

Level of evidence

Level VI.

Keywords: capacity building, global surgery, otolaryngology, surgical capacity, Zimbabwe

Providing surgical care for ear, nose, and throat (ENT) conditions is a major challenge in countries like Zimbabwe, where many people lack access to necessary medical services. This study aims to understand the current capacity for ENT surgical services in Zimbabwe by examining surgical records from private and public hospitals. By identifying the types and volume of surgeries performed, we can highlight areas where improvements are needed and inform efforts to improve surgical care.

1. INTRODUCTION

The provision of surgical care in the field of otolaryngology‐head and neck surgery poses a significant challenge in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs). Limited or nonexistent access to otolaryngologic care has resulted in a disproportionate burden of morbidity and mortality from otolaryngologic disease in these regions. For instance, hearing loss was identified as the third most common cause of disability in the global burden of disease in 2019, with nearly 80% of those affected residing in LMICs. 1 , 2 For patients requiring specialized care and procedures, access is further constrained by the lack of necessary surgical infrastructure and operative equipment. It has been reported that over 5 billion people worldwide lack access to timely, safe, and affordable surgical care, with a significant portion of this population in LMICs. 3 , 4 The estimated percentage of people without access to surgical care ranges from 68.3% in upper‐middle‐income countries to 99.3% in low‐income countries. 4

In Zimbabwe, a lower‐middle income country, the challenges associated with improving the provision of adequate surgical services are compounded by a healthcare system that has been consistently underfunded due to economic hardships over the past few decades. 5 Constraints in Zimbabwe's surgical resources have lasting impacts on the overall health of the country's population. 6 While efforts have been made to improve the standard of care, Zimbabwe continues to work toward achieving its patient care goals, as outlined by the national Ministry of Health and Child Care. 7 Consequently, access to surgical subspecialty care, such as otolaryngology, is limited. According to a 2023 study, Zimbabwe had 0.11 otolaryngologists per 100,000 people, compared to 3.31 per 100,000 people in the US. 8 This disparity highlights the urgent need to build capacity in this field.

Understanding the capacity and delivery of otolaryngology surgical services in Zimbabwe through healthcare capacity assessments can identify unmet needs in surgical care, inform efforts to expand access, and reduce preventable patient morbidity and mortality. 9 To date, limited data are available on the capacity of otolaryngology surgical services in Zimbabwe. In this study, we conduct an evaluation of otolaryngologic surgical capacity in Zimbabwe by presenting the volume of otolaryngology surgical procedures performed in several government and private hospitals. The analysis of these results will provide a greater perspective into the surgical volume, surgical diversity, and overall capacity within the country, as well as highlight which unmet surgical needs remain.

2. METHODS

2.1. Settings

Study exemption was obtained from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB 22‐006024). A retrospective review was conducted from hand‐written otolaryngology surgical case logs at four hospitals, including one private hospital—Harare Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Institute (HEENT)—and three government‐funded hospitals—Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals (PGH), Sally Mugabe Children's Hospital (SMCH), and Sally Mugabe Adult's Hospital (SMAH)—from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2022. These data were collected during a short‐term surgical trip to Harare in October 2022. Neurosurgical, general surgery, and plastic surgery case logs were not included in our review, though there is some overlap in transsphenoidal hypophysectomy, thyroidectomy, and cleft lip and palate repair, respectively. There is no oral and maxillofacial surgery available as a specialty. Our inclusion period was chosen to provide a recent 4‐year snapshot of otolaryngology surgical capacity and to capture both pre‐ and post‐COVID‐19 impacts on procedural volumes and hospital capacity. Additionally, no prior data were available.

The three public hospitals were selected for our study because they are the only public hospitals with otolaryngology providers in Harare, where the surgical trip took place. HEENT was included by invitation of the principal investigator (JPW) from the local study team. It is a private specialty hospital with access to specialized equipment and better funding than public hospitals. All three public hospitals are tertiary hospitals with PGH, which is affiliated with the University of Zimbabwe, being the largest hospital in the country. These hospitals operate under resource constraints, including equipment shortages, understaffing (nurses, physicians, allied staff), limited access to water, electricity, and oxygen, and outdated infrastructure. In addition, patients are not scheduled for surgery but instead are treated as service is available.

2.2. Data collection

Patient age and surgical intervention for surgeries conducted in the operating room were included. Data on minor surgeries performed under local anesthesia in clinics were unavailable. Other perioperative information including surgical outcomes were unavailable due to lack of patient follow‐up and record keeping.

Procedures were categorized into one of six groups: head and neck malignancy, laryngeal surgery, oropharyngeal surgery, otologic surgery, and rhinology/sinus surgery, and “other”. The classification of procedures is shown in Table 1. During data collection, several assumptions were made to address some limitations in the available data. First, we assumed that the procedure recorded in the surgical logs as planned was indeed the procedure performed, given that only the planned procedures were documented in the logs. Second, in cases where the surgical approach was unspecified, we defaulted to the most common approach; for example, sinus surgeries were assumed to be performed endoscopically, as this is the prevalent method. Lastly, we assumed that all surgeries conducted were recorded in the logs.

TABLE 1.

Classification of procedures into groups.

| Procedural group | Procedures |

|---|---|

| Oropharyngeal |

Adenotonsillectomy Quinsy incision and drainage Frenotomy |

| Rhinology/Sinus |

Endoscopic sinus surgery Open sinus surgery Polypectomy Turbinate reduction Septoplasty Nasal cauterization Endoscopic dacrocystorhinotomy |

| Head and neck malignancy |

Incision and drainage of head or neck mass Lymph node biopsy Soft tissue biopsy Excision of congenital mass Excision of soft tissue mass Skin excision (Keloid, Fistula, Lesion) Thyroidectomy Parotidectomy Neck dissection Neck exploration Maxillectomy Laryngectomy |

| Otologic |

Grommets insertion/removal Tympanoplasty Mastoidectomy/tympanomastoidectomy Microotoscopy (diagnostic/therapeutic) cholesteatoma Cochlear implant |

| Laryngeal |

Endoscopic laryngeal surgery Tracheostomy Supraglottoplasty Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty Laryngotracheal reconstruction |

| Other |

Direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy Nasopharyngoscopy Esophagoscopy Foreign body removal (ear/nose/throat) |

2.3. Data analysis

De‐identified data were exported to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the types and number of surgeries performed, patient demographics, and procedural distribution across hospitals. The data were analyzed to identify trends and differences in surgical volume and types of procedures performed at each hospital.

3. RESULTS

Data on the number of procedures performed and demographic information by age were analyzed. Due to a loss of hospital records, data for PGH during 2019 and 2020, and for SMAH during 2020, were unavailable for analysis. Additionally, data regarding surgical outcomes for all hospitals were unavailable.

3.1. Demographics

Of the surgeries performed, 39.5% were on pediatric patients (0–18 years old), while 60.5% of procedures were on adult patients. HEENT and PGH had nearly an equal distribution of adult and pediatric cases, with HEENT performing 48.8% of procedures on adults and PGH 49.5%. In contrast, SMAH had a higher proportion of adult procedures at 84.9%.

3.2. Trends in surgical procedures

A total of 2626 procedures were recorded across the four hospitals within the available time frames: 1470 at HEENT, 377 at PGH, 625 at SMCH, and 154 at SMAH. Across these hospitals, 34 distinct types of procedures were documented. The type and number of procedures across all hospitals are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Otolaryngology procedural volume across all hospitals from 2019 to 2022. Note the number of adenotonsillectomy/adenoidectomy/tonsillectomy performed is graphed on a separate axis. DLB, Direct laryngoscopy with bronchoscopy; HEENT, Harare Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Institute; PGH, Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals; SMAH, Sally Mugabe Adult Hospital; SMCH, Sally Mugabe Children's Hospital.

The most common procedures were adenotonsillectomy/adenoidectomy/tonsillectomy (38.9%), diagnostic endoscopy (10.4%), endoscopic sinus surgery (8.3%), open or endoscopic septoplasty (5.4%), and endoscopic laryngeal surgery (5.1%). The least commonly performed procedures were soft tissue biopsies (0.23%), supraglottoplasty (0.19%), endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy (0.19%), uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (0.15%), and cholesteatoma surgery (0.04%). Notably, no transsphenoidal skull base surgeries were recorded in the surgical case logs, however neurosurgical logs were not included in the data collection.

Among pediatric patients, adenotonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, and tonsillectomy were the predominant surgeries, constituting 58.4% of cases (Figure 2). For adults, there was more variety in surgeries performed with the most common being endoscopic sinus surgery (17.1%), diagnostic endoscopy (15.1%), and septoplasty (12.1%) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Otolaryngology procedural volume performed on pediatric patients across all hospitals from 2019 to 2022. Note the number of adenotonsillectomy/adenoidectomy/tonsillectomy performed is graphed on a separate axis.

FIGURE 3.

Otolaryngology procedural volume on adult patients across all hospitals from 2019 to 2022.

Volumes across all procedural groups declined from 2019 to 2020 at SMCH and HEENT, the two hospitals with available data for both years (Figure 4). SMCH experienced a 75.5% reduction in overall volume (n = −185), while HEENT saw a 40.2% reduction (n = −164). The three procedures with the largest absolute volume decreases at HEENT were adenotonsillectomy (n = −70, 59.3% decrease), grommet insertions (n = −23, 58.9% decrease), and septoplasty (n = −16, 39.0% decrease). At SMCH, these were adenotonsillectomy (n = −139, 89.7% decrease), diagnostic endoscopy procedures (n = −10, 90.1% decrease), and excision of soft mass (n = −8 decrease, 100% decrease).

FIGURE 4.

Otolaryngology procedural volumes from 2019 to 2022. Panel A shows overall procedural volume by year for each hospital. Panels B–G display the private hospital's (HEENT) and the combined public hospitals' procedural volumes across the six procedural categories. ‡ indicates that 2019 public volumes reflect SMCH and SMAH volume only, due to unavailable PGH data. * indicates that 2020 public volumes reflect SMCH volume only, as PGH and SMAH data were unavailable.

The largest increase in absolute procedural volume from 2021 to 2022 at both HEENT and public hospitals was in oropharyngeal surgeries, with HEENT performing 52 more oropharyngeal procedures (43.0% increase) and public hospitals performing 61 more (41.5% increase). This growth was largely due to a resurgence in adenotonsillectomy cases. The laryngeal and “other” groups of procedures saw the largest absolute volume reductions among the public hospitals with a decrease of 57 procedures (76.0% decrease) and 31 procedures (44.9% decrease), respectively. The decrease in the laryngeal group was largely due to a drop in endoscopic laryngeal surgery volume at SMCH. The decrease in the “other” group was due to decreases in diagnostic endoscopic procedures (e.g., direct laryngoscopy with bronchoscopy) and foreign body removal from the ears, nose, or throat. The other groups of procedure across all hospitals had comparatively stable volumes from 2021 to 2022.

3.3. Hospital capacity

HEENT showed the highest volume of procedures every year (Figure 4). Additionally, HEENT performed a wider range of procedures than all public hospitals (Table 2). Certain procedures were observed to be exclusively performed at HEENT. These included endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy, cochlear implants, frenotomy, and cholesteatoma surgery, although these were performed at low volumes. Furthermore, HEENT performed 75% or more of several other procedures, such as uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, mastoidectomy/tympanomastoidectomy, tympanoplasty, turbinate reduction, and septoplasty (Table 3). In contrast, many fewer procedures were exclusively or predominantly performed by public hospitals. PGH performed all six cases of neck exploration, nearly all laryngectomies, and the majority of open sinus surgeries.

TABLE 2.

Procedural volume and number of distinct procedures at each hospital.

| Hospital | Total procedural volume | Number of distinct procedures |

|---|---|---|

| HEENT | 1470 | 32 |

| PGH | 377 | 27 |

| SMCH | 625 | 22 |

| SMAH | 154 | 21 |

TABLE 3.

Procedures exclusively or predominantly (≥75%) performed by a hospital.

| Procedure | Hospital | Hospital's number of cases | Total number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Septoplasty | HEENT | 135 | 141 | 95.7 |

| Tympanostomy tube insertion/removal | HEENT | 116 | 133 | 87.2 |

| Turbinate reduction | HEENT | 114 | 122 | 93.4 |

| Microotoscopy | HEENT | 51 | 61 | 83.6 |

| Tympanoplasty | HEENT | 34 | 44 | 77.3 |

| Mastoidectomy/Tympanomastoidectomy | HEENT | 15 | 19 | 78.9 |

| Nasal cauterization | HEENT | 18 | 19 | 94.7 |

| Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty | HEENT | 3 | 4 | 75.0 |

| Supraglottoplasty | HEENT | 4 | 5 | 80.0 |

| Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy | HEENT | 5 | 5 | 100.0 |

| Frenotomy | HEENT | 12 | 12 | 100.0 |

| Cochlear implants | HEENT | 9 | 9 | 100.0 |

| Cholesteatoma surgery | HEENT | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| Open sinus surgery | PGH | 24 | 28 | 85.7 |

| Laryngectomy | PGH | 9 | 10 | 90.0 |

| Neck exploration | PGH | 6 | 6 | 100.0 |

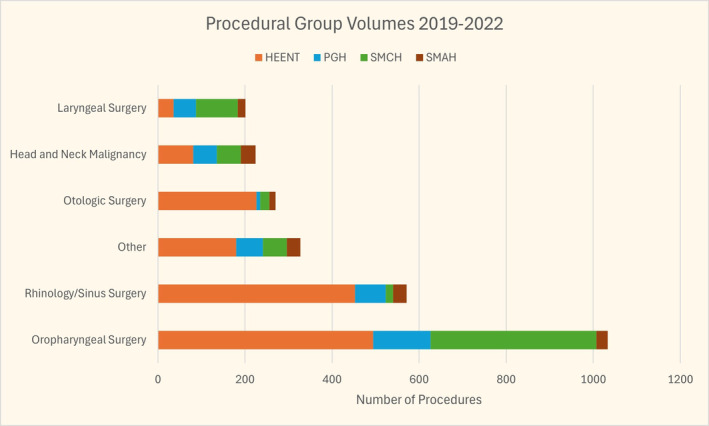

When procedures were grouped, oropharyngeal surgeries were found to be the most frequently performed across all hospitals except SMAH (Figure 5). After excluding adenotonsillectomies, the highest volume procedural group became rhinology/sinus. Laryngeal surgeries were the least common group of procedures. HEENT had higher surgical volumes across all categories compared to the public facilities, except for laryngeal surgery. Despite being a single facility, HEENT consistently had higher volumes in rhinology/sinus and otologic surgeries than the combined public hospital volumes. HEENT accounted for 79.3% of all rhinology/sinus and 69.1% of all otology surgeries performed across the four hospitals during the study period.

FIGURE 5.

Otolaryngology procedural volume by group from each hospital from 2019 to 2022.

4. DISCUSSION

This study provides an analysis of otolaryngology procedural volumes across four hospitals in Harare, Zimbabwe from 2019 to 2022. These hospitals likely represent a significant portion of the otolaryngology service available in the country. Outside of the three public hospitals included in this study, only three other public hospitals in the country—Mpilo Hospital, United Bulawayo Hospital, and Bindura Provincial Hospital—offer otolaryngology services. These hospitals are all located outside of Harare and are staffed with only one otolaryngologist per hospital. Among private hospitals, HEENT is also one of the few hospitals offering otolaryngology services.

4.1. Private vs. public hospital capacity

There were differences in surgical capacities when comparing HEENT to the three public hospitals. HEENT demonstrated the highest surgical volume overall, as well as in many specific procedures, and performed the greatest variety of procedures. Documentation of certain procedures, although at a low volume, like endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy, cholesteatoma surgery, and cochlear implants exclusively, and the majority of cases for procedures such as uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, supraglottoplasty, and various otology and rhinology/sinus surgeries, demonstrates its relatively advanced capabilities. As a private hospital, HEENT has access to specialized and functional equipment for certain procedures, particularly in the fields of rhinology/sinus and otology, which were performed at much higher volumes compared to the public hospitals.

Furthermore, differences in patient populations served by public versus private hospitals contribute to the variation in procedure types and volumes. The public hospitals serve a broader socioeconomic range, including the country's most impoverished populations. This includes patients who may not afford less elective and non‐urgent otolaryngologic procedures, such as some sinonasal and otologic surgeries. 10 HEENT performed 71.0% of endoscopic sinus surgery, which are often indicated for not life‐threatening conditions. Consequently, patients seeking care at public hospitals might forego evaluations for such conditions due to cost or perceived necessity. Many patients with lower socioeconomic status in Zimbabwe wait until their condition becomes advanced and debilitating before seeking care, often at public hospitals. This is exemplified by the high volume of open sinus surgery at public hospitals (26 cases) compared to HEENT (two cases) which were performed due to advanced sinus disease.

Differences in accessibility and quality care offered by public and private hospitals is part of a broader challenge observed in LMICs. 11 One of the primary implications of this is the financial burden on patients, which can be seen in Zimbabwe. The country does not have a publicly funded insurance system, and only approximately 10% of Zimbabweans are reported to have private health insurance. 12 It should be noted that public hospitals provide free care, including surgery, to patients younger than 5 years and older than 65 years as well as to some patients with difficult social circumstances through the Social Welfare department. However, this still leaves most Zimbabweans with the burden of financing their healthcare through out‐of‐pocket payments. This burden is especially high at private hospitals where most patients cannot afford the payments, though certain services are only available at those hospitals. 13 A previous study reported that in 2015, 7.6% of Zimbabwean households incurred catastrophic health expenditure, with this rate being 13.4% for the poorest quintile of patients. 14 Uninsured high‐income, and some middle‐income, patients could afford and seek otolaryngology services from private hospitals. This has created a gap where generally the wealthier narrower segment of the population has access to specialized higher quality care.

The observed disparities between private and public hospitals in Zimbabwe may be attributed to economic, historical, and political factors. Economic challenges that resulted in hyperinflation in the 2000s have significantly strained the public health system in Zimbabwe. Public hospitals face significant challenges, including insufficient funding, high staff turnover, and resource shortages. 5 , 10 , 15 Zimbabwe has one of the lowest public healthcare expenditures as a share of its government spending, even when compared to countries in similar income groups. 14 In contrast, the private sector benefits from a substantial proportion of Zimbabwe's private health insurance expenditure and private funding sources, resulting in better‐resourced facilities. 12

The frailties of the underfunded public health sector and the inequities in access to private care were further exposed by the COVID‐19 pandemic. 16 , 17 During the pandemic, the public health sector was overwhelmed, facing shortages of human resources, consumables, and admission space. 18 The private sector, though better resourced, remained inaccessible to most of the population due to high costs. This disparity in resources is apparently reflected in our surgical capacity data. Comparison of SMCH and HEENT shows that most procedure categories in both hospitals experienced a decline in volume in 2020, reflecting the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on surgical services. This trend has been observed in other specialties with pediatric surgery in Zimbabwe having a reported 65.3% reduction in weekly procedural volume during the pandemic. 19 The differences in the decrease of procedural volumes between SMCH and HEENT (75.5% vs. 40.2%), however, suggest differences in how these different sectors managed surgical services during the pandemic. The public hospital faced significant reductions in most elective surgeries, most notably adenotonsillectomies, due to limited resource re‐allocation during the pandemic and additionally likely due to differences in the patient demographics served by public hospitals. HEENT showed recovery to near pre‐pandemic overall procedural volumes in 2021 and even surpassed pre‐pandemic volumes in 2022. In contrast, SMCH showed lower volumes for 2021 and 2022 compared to pre‐pandemic levels.

Investing in capacity building for public hospitals is essential to decentralize care and improve access for a broader patient population. Addressing these disparities would require coordinated investments from both the public and private sectors. Public‐private partnerships have been increasingly recognized as a potential solution to enhance healthcare delivery in Zimbabwe and other LMICs. 20 , 21 By leveraging the strengths of both sectors these partnerships can improve healthcare infrastructure, resource allocation, medical education, and service delivery. Such collaborations could involve investments in infrastructure, resource sharing, workforce training, and financial mechanisms to improve the volume and availability of procedures for patients in the public healthcare sector. Ultimately though, providing safe and affordable surgery to those with limited access is the responsibility of the country's government and without horizontal funding of national hospitals, quality will likely not improve.

4.2. Using capacity to direct surgical education and capacity building

Adenotonsillectomy, diagnostic endoscopy, and endoscopic sinus surgery were consistently the three most frequently performed procedures at HEENT, PGH, and SMAH. Adenotonsillectomy was also the most performed procedure at SMCH, making up 61.0% of all procedures performed at the hospital over 4 years. This is consistent with findings from our previous needs assessment of Zimbabwean otolaryngologists which found adenotonsillectomy and chronic rhinosinusitis as the two most common procedures they reported performing. 22 Though these procedures were performed at relatively high volumes, we do not currently have data on their short‐term or long‐term outcomes. Thus, future capacity‐building efforts should focus on improving quality of existing care by tracking surgical outcomes in addition to teaching surgeons novel surgical skills and techniques.

There were 14 procedures which were documented a total of 10 times or less across all hospitals. Among these are laryngotracheal reconstruction, with only eight cases documented, and several head and neck malignancy surgeries. The low volumes of these procedures do not reflect the global burden of disease and suggests the need for targeted education for airway and head and neck surgeries. The data also revealed opportunities for highly impactful capacity building through improving resource availability. For instance, there is a low volume of procedures for pediatric airway foreign body cases, particularly among the public hospitals, despite the high incidence of airway foreign body worldwide and their associated mortality rates. 23 Due to lack of appropriate resources and training in national hospitals, airway foreign body cases that present to these hospitals may not be offered treatment.

Additionally, there were no transsphenoidal skull base surgeries documented, which was among the three most common procedures Zimbabwean otolaryngologists desired to perform in our previous needs assessment. 22 However, a limitation of this study is that neurosurgical registries were not reviewed to include endoscopic endonasal approaches to the pituitary. One otolaryngologist in Zimbabwe, who is fellowship trained in rhinology and skull base surgery, performs transsphenoidal surgery alongside a neurosurgery team. However, these cases are less common than open approaches to the pituitary in government hospitals, and they are not performed at the private otolaryngology hospital due to a lack of neurosurgical equipment. The rarity of endonasal skull base approaches limits trainee exposure and experience, restricting capacity development. Addressing these gaps through targeted surgical education and resource allocation will be necessary for improving surgical capacity and outcomes.

As suggested above, there are also differences in needs between the hospitals. HEENT appears to have a relatively high capacity for several otology procedures, such as tympanostomy tube insertions/removals, where it performed 116 compared to a combined total of 17 by the other three hospitals. Similarly, in rhinology/sinus surgery, HEENT performed 135 septoplasties, while the other three hospitals combined performed only six. These differences are due to shortages in equipment and consumable supplies, the cost and availability of surgeons and other staff, and the OR time available to surgeons at public hospitals. HEENT showed lower volumes of laryngeal surgeries, performing only 17.9% of all laryngeal surgeries. In contrast, laryngeal surgery is the second most common procedural group at SMCH, due to the high volume of pediatric patients with laryngeal papillomatosis, a life‐threatening condition. This highlights the need to increase the capacity for more elective laryngeal surgeries in both the public and private sectors.

4.3. Impact of data unavailability and strengthening data collection

Unfortunately, missing data for PGH from 2019 to 2020 (50% of the included time period) and SMAH from 2020 (25% of the included time period) provide us with an incomplete understanding. This data unavailability was because the physical, original surgical registries were unavailable for those certain years. This missing information leads to a potential underestimation of surgical capacity and potential procedural diversity. Consequently, comparisons between HEENT (with complete data) and the public hospitals (with some missing data) become less reliable, making it challenging to draw unbiased conclusions about the differences in operative capacities and trends. However, we have captured approximately 81% of the possible procedural data performed across our study hospitals over these 4 years, which gives a strong foundational understanding of the capacity in these hospitals.

In all four hospitals, surgical registries are kept by surgical administrators in large hand‐written books with variable information recorded for each case, typically including patient name, age, surgery performed and surgeon. The surgical registries are maintained in the administrator's offices for up to 4 years and then moved to protected storage. What is written in the logs is generally reliable as most of the time the procedure that was recorded in the log, that is, the planned procedure, was the procedure performed. Additionally, the logs often had complete information about each procedure. However, there were a few instances in which the logs went missing, and the surgeries performed during that period may not have been recorded and therefore may not be reflected in this study.

Improving data collection and reporting mechanisms in these hospitals is essential for accurate healthcare planning and evaluation. Our team begun addressing this issue by previously implementing an otolaryngology surgical registry in Zimbabwe, which not only collects surgical capacity data but also surgical outcomes. Strengthening data collection efforts through such registries can help in maintaining consistent and accurate records for future capacity assessments. Though future efforts will standardize data extraction and categorize procedures more consistently, the limitations discussed constrain the robustness of the present study's conclusions. As such, this study's findings should be viewed as an initial step toward understanding surgical capacity in Zimbabwe which further research could build on. Additionally, this study's methodology serves as a blueprint for similar capacity assessments in other LMICs, with adjustments tailored to local contexts.

5. CONCLUSION

Conducting capacity assessments of surgical services is important for identifying needs and disparities in otolaryngology care. These assessments directly complement assessment data collected from the perspective of practicing surgeons in the area. This study in Zimbabwe revealed a private hospital had a higher surgical volume and range of procedures compared to three public hospitals. The main driver of surgical volume was oropharyngeal surgery, primarily tonsillectomy/adenotonsillectomy. Besides oropharyngeal surgery, the private hospital also showed relatively higher volumes of certain rhinology/sinus and otology surgery, suggesting greater capacity. Such findings allow for targeted interventions for advancing surgical capacity and perhaps the need for private‐public collaboration to provide access to safe and affordable surgery to the population of Zimbabwe. The study also reinforces the need for strengthening data collection, maintenance and reporting mechanisms for more accurate future capacity assessments. Overall, this study provides a foundation for understanding otolaryngologic surgical capacity in Zimbabwe to foster international collaboration, promote further research, and serve as a guide for similar assessments in other LMICs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors significantly contributed to and agree with the content of this manuscript in its current state. All listed authors qualify according to the ICMJE standards.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Munyaradzi Kaitro, MB ChB and Tafadzwa Nyamurowa, MB ChB for assisting with the collection of procedural data for this study.

Green KJ, Eyassu DG, Jain A, et al. Quantifying capacity of otolaryngology‐head and neck surgery in Zimbabwe. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. 2025;10(1):e70062. doi: 10.1002/lio2.70062

Katerina J. Green and Daniel G. Eyassu are co‐first authors of this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the results of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Haile LM, Kamenov K, Briant PS, et al. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990–2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet. 2021;397(10278):996‐1009. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00516-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Deafness and Hearing Loss . 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss

- 3. Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet. 2015;386(9993):569‐624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alkire BC, Raykar NP, Shrime MG, et al. Global access to surgical care: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(6):e316‐e323. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70115-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Manyika W, Gonah L, Hanvongse A, Shamu S, January J. Health financing: relationship between public health expenditure and maternal mortality in Zimbabwe between the years 1980 to 2010. Med J Zambia. 2019;46(1):61‐70. doi: 10.4314/MJZ.V46I1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guillon M, Audibert M, Mathonnat J. Efficiency of district hospitals in Zimbabwe: assessment, drivers and policy implications. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022;37(1):271‐280. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gage AD, Gotsadze T, Seid E, Mutasa R, Friedman J. The influence of continuous quality improvement on healthcare quality: a mixed‐methods study from Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2022(298):114831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Petrucci B, Okerosi S, Patterson RH, et al. The global otolaryngology‐head and neck surgery workforce. JAMA Otolaryngol: Head Neck Surg. 2023;149(10):904‐911. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2023.2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stewart BT, Gyedu A, Gaskill C, et al. Exploring the relationship between surgical capacity and output in Ghana: current capacity assessments may not tell the whole story. World J Surg. 2018;42(10):3065‐3074. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4589-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nyakutombwa CP, Nunu WN, Mudonhi N, Sibanda N. Factors influencing patient satisfaction with healthcare services offered in selected public hospitals in Bulawayo. Zimbabwe Open Public Health J. 2021;14(1):181‐188. doi: 10.2174/1874944502114010181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lewis TP, McConnell M, Aryal A, et al. Health service quality in 2929 facilities in six low‐income and middle‐income countries: a positive deviance analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(6):e862‐e870. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00163-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mhazo AT, Maponga CC, Mossialos E. Inequality and private health insurance in Zimbabwe: history, politics and performance. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22:54. doi: 10.1186/s12939-023-01868-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kamvura TT, Dambi JM, Chiriseri E, Turner J, Verhey R, Chibanda D. Barriers to the provision of non‐communicable disease care in Zimbabwe: a qualitative study of primary health care nurses. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-00841-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zeng W, Lannes L, Mutasa R. Utilization of health care and burden of out‐of‐pocket health expenditure in Zimbabwe: results from a National Household Survey. Health Syst Reform. 2018;4(4):300‐312. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2018.1513264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dzvairo T. Unpacking the effects of high staff turnover in Zimbabwean government hospitals. Am J Multidiscip Res Innov. 2023;2(2):51‐57. doi: 10.54536/ajmri.v2i2.1242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moyo I, Tshivhase L, Mavhandu‐Mudzusi AH. Caring for the careers: a psychosocial support model for healthcare workers during a pandemic. Curationis. 2023;46(1):2430. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v46i1.2430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kavenga F, Rickman HM, Chingono R, et al. Comprehensive occupational health services for healthcare workers in Zimbabwe during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0260261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murewanhema G. Public health sector capacity and resilience building in Zimbabwe: an urgent priority as further waves of COVID‐19 are imminent. S Afr Med J. 2022;112(4):249‐250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mazingi D, Shinondo P, Ihediwa G, Ford K, Ademuyiwa A, Lakhoo K. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on paediatric surgical volumes in Africa: a retrospective observational study. J Pediatr Surg. 2023;58(2):275‐281. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2022.10.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chikwawawa C, Bvirindi J. Exploring the feasibility of public private partnerships in the healthcare sector in Zimbabwe. Int J Sci Res Publ IJSRP. 2019;9(11):p9503. doi: 10.29322/IJSRP.9.11.2019.p9503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fanelli S, Salvatore FP, De Pascale G, Faccilongo N. Insights for the future of health system partnerships in low‐ and middle‐income countries: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):571. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05435-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Green KJ, Matinhira N, Jain A, et al. Bidirectional needs assessment of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery short‐term surgical trips in Zimbabwe. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2024;9(3):e1278. doi: 10.1002/lio2.1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lima JAB, Fischer GB. Foreign body aspiration in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2002;3(4):303‐307. doi: 10.1016/s1526-0542(02)00265-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the results of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.