Abstract

Background

Karyotype 46, XY female disorders of sex development (46, XY female DSD) are congenital conditions due to irregular gonadal development or androgen synthesis or function issues. Genes significantly influence DSD; however, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. This study identified a Chinese family with 46, XY female DSD due to the CUL4B gene.

Methods

The proband medical history and pedigree were investigated. Whole-exome sequencing was performed to analyze different variations. Transiently transfected testicular teratoma (NT2/D1), KGN ovarian cells with either mutant or wild-type CUL4B gene, and knock-in Cul4b mouse models were confirmed. The expression levels of sex-related genes were analyzed.

Results

A 9.5-year-old girl was diagnosed with 46, XY DSD. A hemizygous variant c.838 T > A of the CUL4B gene was detected. The mRNA and protein levels of WNT4 and FOXL2 genes were higher than those in the wild-type group; however, CTNNB1, SOX9, and DMRT1 were lower in the wild-type group in NT2/D1 cells. In KGN ovarian cells of the mutant group, the mRNA and protein levels for WNT4 and CTNNB1 were elevated. Damaged testicular vasculature and underdeveloped seminal vesicles were observed in Cul4bL337M mice.

Conclusions

A missense CUL4B variant c.838 T > A associated with 46, XY female DSD was identified, and may activate the Wnt4/β-catenin pathway. Our findings provide novel insights into the molecular mechanisms of 46, XY female DSD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40659-024-00583-1.

Keywords: CUL4B, Disorders of sex development, Complete gonadal dysplasia, Gene, Wnt4/β-catenin

Introduction

Karyotype 46, XY female disorders of sex development (46, XY female DSD) are congenital conditions resulting from atypical gonadal development. This can be due to conditions, including Swyer syndrome (also known as complete gonadal dysgenesis) or issues with the production or function of androgens. Variation or abnormal expression of testicular or ovarian development genes is one of the primary causes of 46, XY female DSD. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) is the standard clinical examination for investigating known or novel genes associated with DSD. However, only 13% to 43% of DSD patients with specific disease-causing genes (including SRY, AR, SRD5A2, and SF1) have been identified [1–3]. Although an increasing number of novel causative genes are being discovered, their specific roles in the network of gonadal development remain unclear.

The development of the gonads is a dynamic and sophisticated process orchestrated by complex regulatory networks with multiple genes involved. SRY is expressed in the somatic gonad of XY individuals at the onset of the sex-determination period, upregulates SOX9, and results in the formation of testes. SOX9 promotes normal testicular differentiation and inhibits ovarian pathways through fibroblast growth factor and its receptors (FGF9/FGFR2) and testicular regulators, including double sex and mab-3-related transcription factor 1 (DMRT1) [4–7]. If the SRY/SOX9 pathway is not activated, factors including WNT family member 4 (Wnt4), β-catenin, and forkhead box protein L2 (FOXL2) promote the development of the primordial gonad to the ovary and inhibit the development of testis [8].

The Cullin 4B protein (CUL4B, encoded by the CUL4B gene, OMIM*300304) belongs to the cullin family. It is a scaffold protein forming the RING ubiquitin E3 ligase complex. Mutations of the CUL4B ubiquitin ligase gene are causally associated with syndromic X-linked mental retardation. Recently, it was reported that variants of CUL4B in the human germline could cause intellectual disability, short stature, central obesity, and other abnormalities in humans. Affected 46, XY individuals are frequently associated with reproductive tract abnormalities, including undescended and/or small testes, hypospadias, and small penis. CUL4B is reportedly involved in spermatogenesis through ubiquitination modification [9, 10]. However, information regarding the 46, XY DSD caused by the CUL4B genetic variants remains limited. Existing studies cannot explain the DSD phenotype in male patients with CUL4B gene variants.

This study analyzed clinical features, laboratory results, ultrasonographic data, and surgical and pathological reports for a girl with 46, XY female DSD. Sequencing data on the CUL4B gene revealed a missense variant, c.838 T > A. (p.L280M). Functional assays were performed to elucidate pathogenic mechanisms associated with the CUL4B variant.

Materials and methods

Clinical evaluations

The patient’s past medical history and symptoms were evaluated. Additionally, a physical examination, particularly of the external genitalia, was conducted. Following the laparoscopy, laboratory tests were performed, including hormonal analysis, karyotypic analysis, imagological examinations, and gonadal biopsy with histopathology.

Cytogenetic and molecular studies

Standard techniques were used for karyotype analysis. Using standard methods, genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes of the proband and her parents. Subsequently, trio-WES was performed following the guidelines outlined in the NCBI record NG_009388.1 (NM_001079872.2) [11, 12]. The Illumina HiSeq platform was used for WES following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) nomenclature was used to name the variants [13].

Analysis of the variant’s conservation and pathogenicity

Multiple CUL4B protein sequences were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). ClustalX was used for sequence alignment, and results were visualized online using ConSurf (http://consurf.tau.ac.il/) [14].

Molecular modeling

To investigate the effect of the identified mutations on protein conformation, the 3D arrangement of human CUL4B (PDB code 4A0C) was used [15]. For structural representation, PyMOL 2.5 (http://www.schrodinger.com/pymol/) was used as the molecular visualization system. The interactions between amino acid residues were analyzed using DynaMut (http://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/dynamut/) [16] and Project HOPE (https://www3.cmbi.umcn.nl/hope/) [17].

Plasmid construction

Human CUL4B complementary DNA (cDNA) (NM_003588) was cloned into a pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro vector. The c.838 T > A variation was introduced into the CUL4B sequence through seamless cloning (Tsingke, China).

Cell culture of HEK293T, NT2/D1, and KGN cells

HEK293T cells (ATCC® CRL-11268) and NT2/D1 cells (ATCC® CRL-1973TM) were cultured in HG-DMEM (Hyclone®) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. A granulosa cell tumor line (KGN, RIKEN Cell Bank® RCB1154) of ovarian origin was cultured in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. NT2/D1 and KGN cells stably overexpressing the CUL4B gene were constructed by lentivirus infection. Cells were infected with lentivirus for 72 h and then used in subsequent experiments, wherein lentiviral transfection efficiency exceeded 95%.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent and reverse transcribed into cDNA using HRbio™ III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Heruibio, China, Cat# HRF0191). The primers are listed in Table S1.

Western blot analysis

Western blots were performed as previously described [11]. Antibodies against Phospho-β-catenin (p-β-catenin) (Cat#5961), β-catenin (Cat#8480), SOX9 (Cat#82630 T), and FLAG-tag (Cat#14,793) were procured from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverley, MA, USA). Abcam (Shanghai, China) provided Wnt4 (Cat#ab91226), FOXL2 (Cat#ab188584), DMRT1 (Cat#ab126741), and α-Tublin (Cat#ab52866).

Development of Cul4bL337M mouse model

The CUL4B gene is highly conserved over evolutionary time. Mouse Cul4bL337M is a homozygous variant of human CUL4BL280M. To investigate the role of the L280M mutant in vivo, we established a mouse model for precise editing of the CUL4B gene using the CRISPR-Cas9 system combined with fertilized egg microinjection. Briefly, the gRNA of the CUL4B gene (TCAAAAAGATCGATAGATGC) was designed to construct a homologous recombinant vector. The fertilized eggs of C57BL/6 J mice were injected with Cas9, gRNA, and a homologous recombination vector. The fertilized eggs that survived the injection were transplanted into pseudo-pregnant female mice, which were allowed to conceive and bear offspring. Genome DNA was extracted from the F0 generation mice born from the recipient mice for genotype identification, PCR, and sequencing. Zhejiang University Animal Ethics Committee granted animal ethics approval.

Histology

To investigate the role of the L280M mutant in vivo, mouse testis was harvested after male mice were sacrificed. The entire testis was immersed in modified Bouin’s fixative solution for 16 h at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, the samples were then dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol before being encased in paraffin wax. The sections were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and placed on glass slides.

Statistical analyses

The western blot images were analyzed using the Fiji/Image J program. GraphPad Prism software (version 8) was used for statistical analysis. Statistical significance was determined through various t-tests, including paired, independent, and Welch’s t-tests. All findings were confirmed by a minimum of three separate experiments. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) with a sample size of at least three.

Results

Clinical evaluation

A 9.5-year-old girl was hospitalized due to growth retardation for five years. Her height and body weight were 126.7 cm (– 1.88 SD) and 39 kg (+ 3 SD), and her BMI was 24.3 kg/m2. She was observed to have mild obesity and no distinguishing facial features. Her chest and pubic hair were evaluated as Tanner stage I. She had no pubic hairs or axillary hairs. External genitalia appeared typical female with no clitoromegaly. The size of the right ovary was about 0.75 × 0.63 cm, and the size of the left ovary was 0.73 × 0.38 cm. Pelvic ultrasound revealed that the uterus was about 1.45 × 0.76 × 0.97 cm, the endometrial line was unclear, the endometrial thickness was about 0.11 cm, and the muscle layer was echogenic. There were no abnormal findings in the serum adrenal hormone levels. The blood testosterone and estradiol levels were low, and blood gonadotropin levels were elevated. Table 1 summarizes the hormonal traits of the proband.

Table 1.

Blood biochemical and hormonal characteristics of the proband

| Items | Patient | Normal value |

|---|---|---|

| ATCH | 15.9 | 0.00–46.00 pg/mL |

| LH | 29.1↑ | 0.33–6.10 mIU/mL |

| FSH | 2.96 | 1.37–6.97 mIU/mL |

| Progesterone | <0.21↓ | 0.4–1.2 ng/ml |

| Testosterone | 14.4 | 14.0–76.0 ng/dl |

| Estradiol | <11.8↓ | 37.25–85.8 pg/ml |

| Cortisol8:00am | 10.20 | 5.00–25.00 ug/dL |

ACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone, LH luteinizing hormone, FSH follicularstimulating hormone

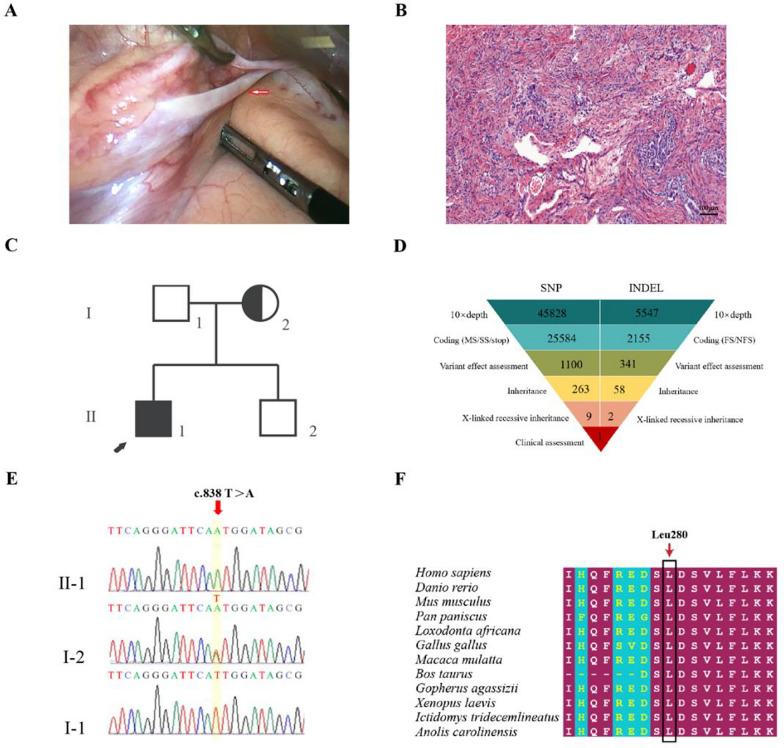

Further diagnostic tests revealed a 46, XY karyotype. A laparoscopic bilateral gonadectomy was performed following genetic testing. Intraoperatively, a 1.5 × 0.7 × 0.5 cm streak of uterus-like tissue was observed. The bilateral fallopian tubes were thin, and no significant abnormalities were present at the umbilical ends of the fallopian tubes. Streak gonads were found below the bilateral fallopian tubes, and the size was about 1.0 × 0.5 × 0.2 cm. Based on pathological analysis, the bilateral streak gonads comprised ovarian interstitial cells and fibrous tissue without malignant transformation (Fig. 1A, B).

Fig. 1.

Pathologic and genetic testing of the proband. A Streak gonads are below the bilateral fallopian tubes (1.0 × 0.5 × 0.2 cm). B Pathological section analysis of proband (HE, 40 ×). Pathological evaluation revealed that the bilateral streak gonads were ovarian interstitial-like cells and fibrous-like tissue. C The pedigree with 46, XY female DSD. The arrowhead denotes the proband. Squares represent XY individuals, and circles represent XX individuals. Affected individuals are indicated as filled black symbols. Dot-filled symbols represent the unaffected heterozygous carriers. Unfilled symbols indicate clinically unaffected subjects harboring the wild-type sequence. D Schematic representation of the exome-data-filtering approach assumes dominant inheritance in the family. The following abbreviations are used: MS, missense variant; SS, splice-site variant; stop, stop-codon variant; FS, frameshift indel; and NFS, non-frameshift indel. E Sanger sequencing chromatograms exhibit that the proband (II-1) carried the c.838 T > A (p.L280M) hemizygous variant, and her mother (I-2) harbored a heterozygous variant of the CUL4B gene. F Interspecific conservation analysis of CUL4B. Color code bars are used to indicate the conservation of amino acids

Genetic diagnoses

The core pedigree members of 46, XY DSD, including her parents, were sequenced using trio-WES and Sanger (Fig. 1C). Within the exome region, there were 27,739 variants, with 65.15% being nonsynonymous (Fig. 1D). After filtering, the 1441 nonsynonymous variants were reduced to 11 rare variants. Finally, a variant site was identified in the CUL4B gene (c.838 T > A) (Fig. 2E). The Sanger sequencing indicated that the proband carried the c.838 T > A (p.L280M) hemizygous variant, and her mother had a heterozygous c.838 T > A variant of the CUL4B gene. Additionally, WES and Sanger sequencing confirmed a missense variant of the CUL4B gene, which was not present in the public population database gnomAD (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/), Chinese Millionome Database (https://db.cngb.org) or Human Gene Mutation Database (http://www.hgmd.org/) [18].

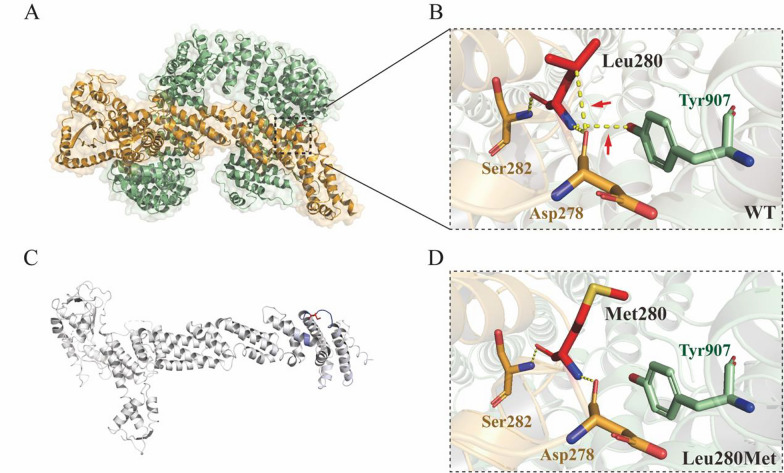

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional structure analysis and the protein dynamics of CUL4B. A Three-dimensional structure of CUL4B protein and its interacting protein CAND1. The black dotted box marks the position of the Leu280Met variant. B Prediction of interactions between amino acid residues of wild-type. Wild-type residue is represented with red sticks. These are placed alongside surrounding residues, which are also involved in other types of interactions. Red arrows indicate interactions between altered amino acids. Hydrogen bonding is represented with a yellow dotted line. C Δ Vibrational Entropy Energy | Visual representation of variant: Amino acids colored according to the vibrational entropy change of the variant. Blue represents a rigidification of the structure. D Prediction of interactions between amino acid residues of Leu280Met variant. Leu280Met residue is represented as red sticks

To further analyze the genetic testing data, we evaluated the interspecific conservation and pathogenicity of the c.838 T > A variant. We compared the CUL4B protein sequences of representative vertebrates, including Homo sapiens, apes, and mice (Fig. 1F). Leu280 residues in CUL4B exhibited a high conservation level among all vertebrates (100%) (Fig. 1F).

Three-dimensional structure modeling

The impact of the identified mutations on the protein shape was examined using the 3D structure of human CUL4B (PDB code 4A0C) to determine the structural alterations in CUL4B. The DynaMut webserver was used to analyze and visualize protein dynamics and determine the effects of the variant. The DynaMut web server was also used to evaluate the local interactions among wild-type and variant amino acid residues. In both the PDB file and in the Protein Interfaces Surfaces and Assemblies (PISA server, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/), Leu280 residue was found to be involved in a multimer contact. The PISA database contains protein assemblies with a high probability of being biologically relevant. This strongly suggests that the residue is in contact with other proteins (Fig. 2A, B). Structural protein analysis through the HOPE protein analysis server indicated that the Leu280Met variant introduces a bigger residue at this position, which can disturb the multimeric interactions. The p.L280M variant also decreases molecule flexibility (ΔΔSVibENCoM: –0.146 kcal.mol–1.K–1) (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the data indicated that this variant resulted in the conversion of leucine (Leu) to methionine (Met), which not only reduces hydrogen bonding with Asp287 but also disrupts its interaction with Cullin-associated NEDD8-dissociated protein 1 (CAND1) (Fig. 2D).

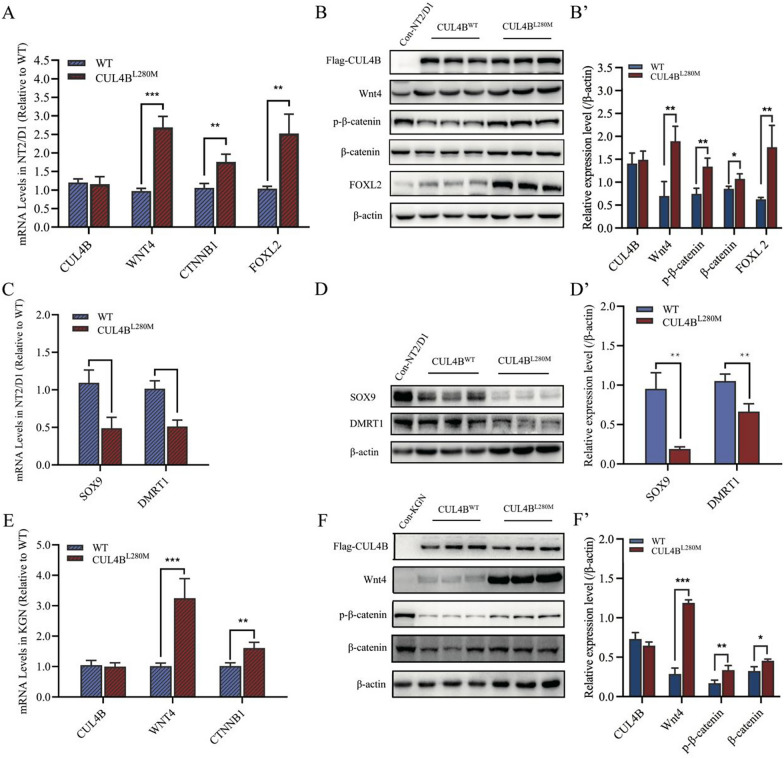

CUL4BL280M leads to hyperactivation of Wnt4/β-catenin signaling pathway

We examined how the CUL4BL280M variant impacts sex-specific signaling pathways by investigating its influence on the expression of key genes associated with testicular and ovarian development. The wild-type or mutant CUL4B gene in the NT2/D1 testicular teratoma cells line and KGN ovarian cells was overexpressed by lentiviral infection. We observed no significant difference between the wild-type and mutant groups in CUL4B mRNA and protein expression. In NT2/D1 cells, the mRNA expressions of WNT4 in the mutant group were 2.6 folds higher compared with the wild-type group (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the protein expressions had increased to 2.8 folds of those of the wild-type (Fig. 3B and B′). The mRNA expressions of CTNNB1 in the mutant group were 1.7 folds higher than those in the wild-type group. The p-β-catenin and β-catenin protein expressions increased to 1.8 and 1.3 folds of the wild-type, respectively (Fig. 3A, B). The mRNA and protein expression of FOXL2 in the mutant group was 2.4 and 2.7 folds higher, respectively, than in the wild-type group (Fig. 3A, B, and B′). Then, we analyzed the expression of key genes, including SOX9 and DMRT1, for testis development. The mRNA expressions of SOX9 and DMRT1 in the mutant group were 44.7% and 50.7% of those in the wild-type group (Fig. 3C). The protein expressions were reduced to 19.9% and 63.0% of the wild-type, respectively (Fig. 3D and D′).

Fig. 3.

Upregulated expression of ovary pathways. A–D NT2/D1 cells transfected with empty vector plasmids expressing either wild-type (WT) or mutant (CUL4BL280M) CUL4B genes. A mRNA levels of CUL4B, WNT4, CTNNB1, and FOXL2 measured using quantitative PCR. B Western blot analysis of CUL4B, Wnt4, p-β-catenin, β-catenin and FOXL2. (B′) Quantified analysis of western blots of CUL4B, Wnt4, β-catenin, and FOXL2. C mRNA levels of SOX9 and DMRT1 were measured through quantitative PCR. D Western blot analysis of SOX9 and DMRT1. (D′) Quantified analysis of western blots of SOX9 and DMRT1. E and F KGN cells transfected with empty vector plasmids expressing either wild-type (WT) or mutant (CUL4BL280M) CUL4B genes. E mRNA levels of CUL4B, WNT4, and CTNNB1 in KGN cells were measured using quantitative PCR. F Western blot analysis of CUL4B, Wnt4, p-β-catenin, and β-catenin. (F′) Quantified analysis of western blots of CUL4B, Wnt4, p-β-catenin, and β-catenin. For western blotting, results were normalized to β-actin as a reference (n = 3; mean ± SD; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001)

Additionally, the mRNA levels of WNT4 and CTNNB1 in KGN ovarian cells of the mutant group were 3.19 and 1.58 folds of the wild-type group, respectively (Fig. 3E). The mutant group exhibited increased Wnt4, p-β-catenin, and β-catenin protein levels of 4.0, 1.9, and 1.4 folds compared to the wild-type group (Figs. 3F and F′). These results suggested that the CUL4BL280M variant activates the ovarian pathway (Wnt4/β-catenin) in testicular and ovarian cells.

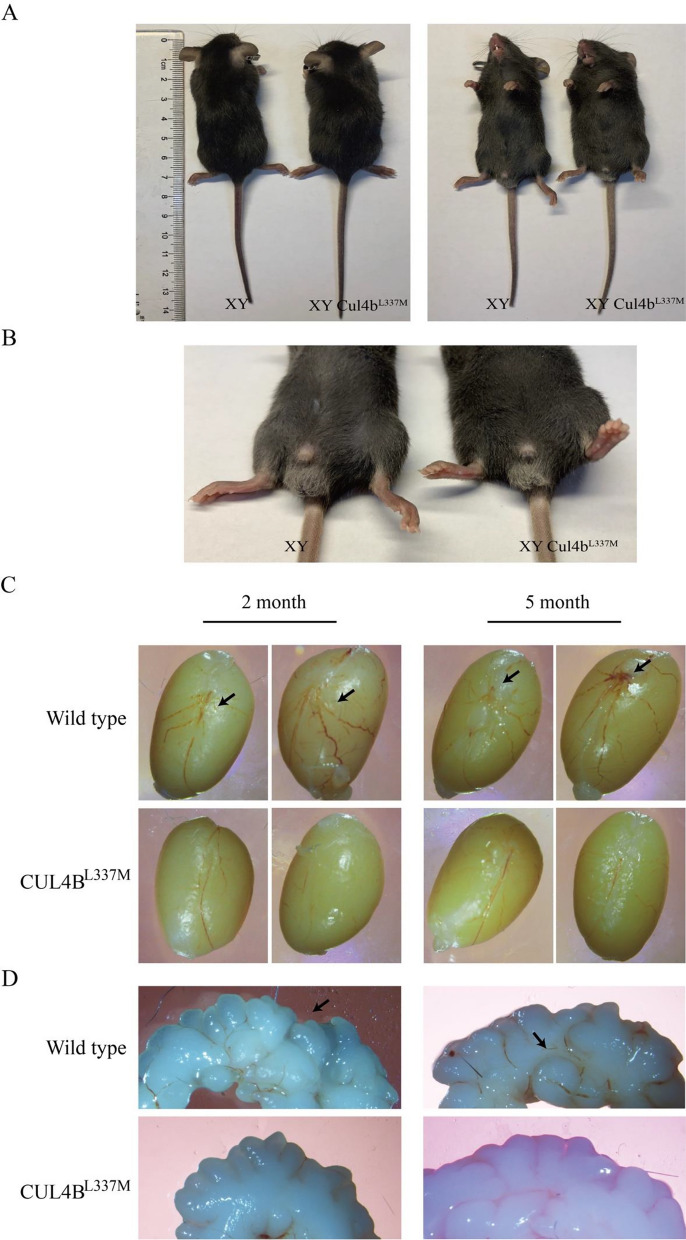

Cul4bL337M variant in mice disrupts testicular vasculature and reproductive function

To determine the effect of the gain of the CUL4B gene variant on gonadal development, we generated precision-edited mice (Cul4bL337M) carrying the homologous variant of human CUL4BL280M. The overall appearance of Cul4bL337M mice exhibited no significant difference from the control mice (Fig. 4A, B). We examined the mouse testicular vasculature (2- and 5-month-old), as this is a major feature of the testis, and found that the testicular vasculature had a disruption in male mice carrying the Cul4b gene variant. The testicular aortas of mutant mice were narrowed, and arterial branches were significantly reduced compared to the wild type (Fig. 4A). In Cul4bL337M males, the seminal vesicles were less developed compared to the wild-type organ, as evidenced by the absence of typical deep invaginations. Additionally, the vascular distribution of seminal vesicles of mutant mice was significantly less than that of wild-type mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Vasculature phenotype of testis and seminal vesicles in Cul4bL337M mice. The overall (A) and penises (B) appearance of Cul4bL337M and wild-type mice. C Vasculature of testis in wild-type and Cul4bL337M mice (2 and 5 months of age). The black arrow points to the testicular artery in wild-type mice. D Appearance of seminal vesicle in wild-type and Cul4bL337M mice (2 and 5 months of age). The seminal vesicles of wild-type mice are deeply invaginated; however, mutant mice lack this characteristic

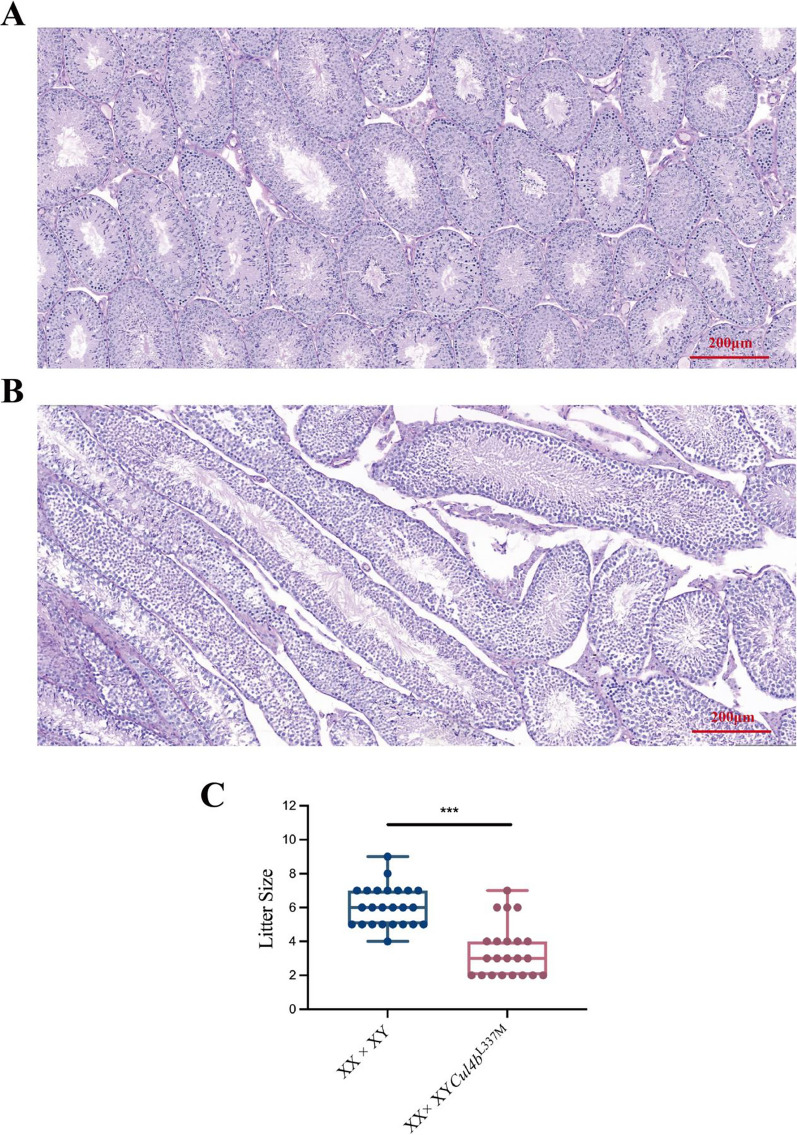

Furthermore, HE staining of testis tissue of mutant male mice exhibited elongation of seminiferous tubules, thinning of the epithelium, atrophy of the seminiferous tubules, and a modest reduction in round spermatids (Fig. 5A, B). These features were consistent with Wnt4 transgenic males. We determined fertility in males carrying the Cul4b gene variant (n > 10) by performing test crosses to wild-type female mice. At 2-month-old, the fecundity of wild-type mice (6.08 ± 1.15 neonatal mice per litter) was significantly higher than that of Cul4bL337M mutant male mice (3.45 ± 1.53 neonatal mice per litter), p < 0.001 (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Testicular pathology and fecundity in mice. A, B Testis by hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining. A HE staining of testis of wild-type mice. B HE staining of testis of Cul4bL337M male mice. C The numbers of pups per litter of wild-type mice and Cul4bL337M mutant male mice crossed with wild-type female mice (n > 20; mean ± SD; *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001)

Discussion

The CUL4B gene is an important cullin-Ring E3 ligase gene family member. The CUL4B gene is located in Xq23 and consists of 22 exons with a full mRNA length of 5785 bp. CUL4B plays an important role in the cell cycle, embryo development, and spermatogenesis through ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation and epigenetic regulation. The CUL4B gene has been reported to cause intellectual developmental disorder, X-linked, syndromic, Cabezas type (OMIM#300354). The main clinical manifestations of CUL4B gene variant patients are neurological abnormalities, short stature, obesity, and reproductive tract abnormalities [19–21]. Reproductive tract abnormalities include cryptorchidism and/or small testes, hypospadias, micropenis, and spermatogenesis abnormalities [19, 22]. Here, we describe a patient presenting with 46, XY female DSD in a Chinese family. WES and Sanger sequencing identified a hemizygous missense variant c.838 T > A (p. Leu280Met) in the CUL4B gene. Segregation analysis in the family revealed that the affected patient had inherited the variant from her healthy mother (heterozygous), while the father and brother did not carry the variant. The CUL4B c.838 T > A variant was not identified through a comparison with population data from the Chinese Millionome Database (db.cngb.org/cmdb/). Moreover, the patient exhibited no significant neurological abnormalities. For the CUL4B gene, the c.838 T > A variant causes an amino acid change from leucine (Leu/L) to methionine (Met/M). Evolutionary conservation analysis revealed that the L280 residue was highly conserved among species. Furthermore, the PISA database and DynaMut online server predicted that there was a significant alteration in the local structure of the p.L280M variant. The Leu280Met variant introduces a larger residue at this position, which can interfere with the multimeric interactions and reduce molecule flexibility. This evidence supports the likely pathogenic nature of the Leu280Met variant. CUL4B is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that interacts with diverse substrates and ubiquitinates them. In addition to CAND1, several proteins interact with CUL4B; however, the mode of protein–protein interaction remains unknown.

Multiple genes are expressed simultaneously throughout human gonadal development [23, 24]. SRY is active in the somatic gonads of XY individuals during sex determination, resulting in an increase of SOX9 and the initiation of testis development [25]. Ovarian differentiation is promoted without SRY (XX individuals) by activating WNT/CTNNB1 through upregulating Rspo1 and Wnt4 [26]. Furthermore, in the human embryonic period, different sex-determining factors, including DMRT1 (OMIM*602424) and FOXL2 (OMIM*605597), are essential for regulating the formation and maintenance of either testicular or ovarian pathways [27–29]. The bipotential gonads’ differentiation is a critical phase in forming an embryo’s identity. A balance between transcriptional activation and repression determines this destiny specification. The CUL4BL280M variant in NT2/D1 cells resulted in increased expression of genes associated with ovarian development (including WNT4, CTNNB1, and FOXL2) and decreased expression of testicular development-related genes (SOX9 and DMRT1). Studies have reported that CUL4B activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling by repressing Wnt antagonists [30–32]. However, the effect of CUL4B’s interactions with its proteins on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway remains unclear. We hypothesized that ubiquitination could be associated with DSD.

WNT4 is a secretory protein essential for female sex development because it inhibits male sexual differentiation in humans [33, 34]. The Wnt4/β-catenin pathway is critical for the formation of ovaries during embryonic development in both mice and humans [35, 36]. Mutations in Wnt4 or Ctnnb1 in mouse XX gonads lead to the gradual development of ovotestes, exhibiting features of both testes and ovaries [35, 37]. Abnormal initiation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway or FOXL2 in XY reproductive organs results in reduced SOX9 expression, which can lead to the development of ovaries [35, 38–40]. Copy number gain or gain of function of the WNT4 gene in humans results in varying degrees of 46, XY DSD, with clinical manifestations ranging from severe complete gonadal dysgenesis to mild phenotypes including hypospadias, cryptorchidism, and micropenis [40, 41]. In cellular experiments, we demonstrated that the CUL4BL280M variant activates the Wnt4/β-catenin/FOXL2 signaling pathway [42]. Next, we tested our hypothesis using the precision-edited mice CUL4BL337M model. In the present study, the male mouse model exhibited that the CUL4BL337M variant interferes with the normal development of male gonadal vasculature and testosterone biosynthesis.

Additionally, the seminal vesicles of CUL4B males were underdeveloped and lacked the deep invagination characteristic of wild-type organs. Testicular histology exhibited spermatogenic tubule elongation, epithelial thinning, and moderate reduction of round sperm cells. These characteristics are consistent with the phenotype of WNT4 transgenic male mice [41]. Therefore, our results suggested that CUL4B gene variation can be involved in the pathogenesis and development of 46, XY DSD through abnormal activation of the Wnt4/β-catenin pathway. Moreover, the CUL4B gene transcript is highly expressed in placental cells, embryonic stem cell lines, and testes in mice [42]. Human CUL4B is highly expressed in pancreatic tissue, endocrine glands, cerebellum, digestive tract, bone marrow, and testes [43, 44]. Cul4b-deficient mice experience growth cessation and degeneration during the initial embryonic phases and die at E9.5, while our genetically modified mice remain unaffected [45, 46]. Consistent with our patient phenotype, our mice lacked neurological manifestations, indicating that the Cul4bL337M variant is tolerable for neurological development. The mouse model exhibited a relatively mild gonadal phenotype, with no sex reversal individuals. This could be due to differences between the murine and human systems regarding sex determination or sex differentiation. Moreover, it is necessary to collect additional gonadal phenotypes of patients with CUL4B gene variation to further clarify the correlation between genotype and phenotype.

In conclusion, we have outlined the clinical features of a proband exhibiting 46, XY female DSD caused by a missense mutation in the CUL4B gene (c.838 T > A/p.L280M). Experiments on in vitro and in vivo animal models indicated that CUL4B gene variation is associated with 46, XY female DSD, which can be caused by activation of the Wnt4/β-catenin pathway. Our findings provide new insights into the clinical evaluation and molecular basis of CUL4B-associated 46, XY female DSD.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the family members and patients for their participation in this study.

Abbreviations

- ACMG

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

- CUL4B

Cullin 4B

- DSD

Disorders of sex development

- DMRT1

Double sex and mab-3-related transcription factor 1

- FOXL2

Forkhead box protein L2

- HE

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HGVS

Human Genome Variation Society

- trio-WES

Trio Whole exome sequencing

- WES

Whole-exome sequencing

- Wnt4

WNT family member 4

Author contributions

C.W., Q.Y.; Formal Analysis: H.C., Q.C., L.L.; Investigation: C.W., H.C.; Methodology: C.W., Q.Y., H.C. Y.Q., K.Y., Project Administration: C.W., H.C.; Supervision: Q.Y., C.W., Writing—original draft: C.W., H.C.; Writing—review and editing: C.W., Q.Y.

Funding

Research supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270837, 82300888).

Availiability of data materials

The variants have been submitted to ClinVar database [Accession numbers: SCV001737544 (CUL4B c.838 T > A: p. Leu280Met].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

A review and approval of the study were obtained from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital at Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China (approval number 2023–0898). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. The parents of the proband provided written informed consent. The ARRIVE guidelines and the Basel Declaration were followed during animal studies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chunlin Wang and Hong Chen have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Chunlin Wang, Email: hzwangcl@zju.edu.cn.

Qingfeng Yan, Email: qfyan@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Baxter RM, Arboleda VA, Lee H, Barseghyan H, Adam MP, Fechner PY, Bargman R, Keegan C, Travers S, Schelley S, et al. Exome sequencing for the diagnosis of 46, XY disorders of sex development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):E333–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggers S, Sadedin S, van den Bergen JA, Robevska G, Ohnesorg T, Hewitt J, Lambeth L, Bouty A, Knarston IM, Tan TY, et al. Disorders of sex development: insights from targeted gene sequencing of a large international patient cohort. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulkarni V, Chellasamy SK, Dhangar S, Ghatanatti J, Vundinti BR. Comprehensive molecular analysis identifies eight novel variants in XY females with disorders of sex development. Mol Hum Reprod. 2023;29(2):gaad001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindeman RE, Murphy MW, Agrimson KS, Gewiss RL, Bardwell VJ, Gearhart MD, Zarkower D. The conserved sex regulator DMRT1 recruits SOX9 in sexual cell fate reprogramming. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(11):6144–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Major AT, Estermann MA, Smith CA. Anatomy, endocrine regulation, and embryonic development of the rete testis. Endocrinology. 2021;162(6):bqab046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croft B, Bird AD, Ono M, Eggers S, Bagheri-Fam S, Ryan JM, Reyes AP, van den Bergen J, Baxendale A, Thompson EM, et al. FGF9 variant in 46, XY DSD patient suggests a role for dimerization in sex determination. Clin Genet. 2023;103(3):277–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagheri-Fam S, Ono M, Li L, Zhao L, Ryan J, Lai R, Katsura Y, Rossello FJ, Koopman P, Scherer G, et al. FGFR2 mutation in 46, XY sex reversal with craniosynostosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(23):6699–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chassot A-A, Gillot I, Chaboissier M-C. R-spondin1, WNT4, and the CTNNB1 signaling pathway: strict control over ovarian differentiation. Reproduction. 2014;148(6):R97-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin Y, Liu L, Yang C, Lin C, Veith GM, Wang C, Sutovsky P, Zhou P, Ma L. Cell autonomous and nonautonomous function of CUL4B in mouse spermatogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(13):6923–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin Y, Zhu L, Li Q, Zhou P, Ma L. Cullin4 E3 ubiquitin ligases regulate male gonocyte migration, proliferation and blood-testis barrier homeostasis. Cells. 2021;10(10):2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Chen Q, Zhu Y, Yuan K, Li H, Zhang B, Jia Z, Zhou H, Fan M, Qiu Y, et al. Variant causes hyperactivation of Wnt4/β-catenin/FOXL2 signaling contributing to 46, XY disorders/differences of sex development. Front Genet. 2022;13:736988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Yuan K, Zhang B, Jia Z, Chen C, Zhu Y, Sun Y, Zhou H, Huang W, Liang L, et al. A novel compound heterozygous variant causes 17α-hydroxylase/17, 20-lyase deficiency. Front Genet. 2019;10:996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, McGowan-Jordan J, Roux A-F, Smith T, Antonarakis SE, Taschner PEM. HGVS recommendations for the description of sequence variants: 2016 update. Hum Mutat. 2016;37(6):564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashkenazy H, Abadi S, Martz E, Chay O, Mayrose I, Pupko T, Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W344–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer ES, Scrima A, Böhm K, Matsumoto S, Lingaraju GM, Faty M, Yasuda T, Cavadini S, Wakasugi M, Hanaoka F, et al. The molecular basis of CRL4DDB2/CSA ubiquitin ligase architecture, targeting, and activation. Cell. 2011;147(5):1024–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodrigues CH, Pires DE, Ascher DB. DynaMut: predicting the impact of mutations on protein conformation, flexibility and stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W350–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venselaar H, Te Beek TAH, Kuipers RKP, Hekkelman ML, Vriend G. Protein structure analysis of mutations causing inheritable diseases. An e-Science approach with life scientist friendly interfaces. BMC Bioinform. 2010;11:548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarpey PS, Raymond FL, O’Meara S, Edkins S, Teague J, Butler A, Dicks E, Stevens C, Tofts C, Avis T, et al. Mutations in CUL4B, which encodes a ubiquitin E3 ligase subunit, cause an X-linked mental retardation syndrome associated with aggressive outbursts, seizures, relative macrocephaly, central obesity, hypogonadism, pes cavus, and tremor. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(2):345–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritelli M, Palagano E, Cinquina V, Beccagutti F, Chiarelli N, Strina D, Hall IF, Villa A, Sobacchi C, Colombi M. Genome-first approach for the characterization of a complex phenotype with combined NBAS and CUL4B deficiency. Bone. 2020;140:115571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura Y, Okuno Y, Muramatsu H, Kawai T, Satou K, Ieda D, Hori I, Ohashi K, Negishi Y, Hattori A, et al. A novel splice site variant in a young male exhibiting less pronounced features. Hum Genome Var. 2019;6:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto N, Watanabe M, Naruto T, Matsuda K, Kohmoto T, Saito M, Masuda K, Imoto I. Genome-first approach diagnosed Cabezas syndrome via novel mutation detection. Hum Genome Var. 2017;4:16045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wisniewski AB, Batista RL, Costa EMF, Finlayson C, Sircili MHP, Dénes FT, Domenice S, Mendonca BB. Management of 46, XY differences/disorders of sex development (DSD) throughout life. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(6):1547–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baetens D, Verdin H, De Baere E, Cools M. Update on the genetics of differences of sex development (DSD). Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;33(3):101271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inkster AM, Fernández-Boyano I, Robinson WP. Sex differences are here to stay: relevance to prenatal care. J Clin Med. 2021;10(13):3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chassot A-A, Bradford ST, Auguste A, Gregoire EP, Pailhoux E, de Rooij DG, Schedl A, Chaboissier M-C. WNT4 and RSPO1 together are required for cell proliferation in the early mouse gonad. Development. 2012;139(23):4461–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang S, Ye L, Chen H. Sex determination and maintenance: the role of DMRT1 and FOXL2. Asian J Androl. 2017;19(6):619–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matson CK, Murphy MW, Sarver AL, Griswold MD, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. DMRT1 prevents female reprogramming in the postnatal mammalian testis. Nature. 2011;476(7358):101–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiménez R, Burgos M, Barrionuevo FJ. Sex maintenance in mammals. Genes. 2021;12(7):999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Yue D. CUL4B promotes aggressive phenotypes of HNSCC via the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Med. 2019;8(5):2278–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Liu HR, Zhao J. Effect and mechanism of miR-217 on drug resistance, invasion and metastasis of ovarian cancer cells through a regulatory axis of CUL4B gene silencing/inhibited Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(1):94–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miao C, Chang J, Zhang G, Yu H, Zhou L, Zhou G, Zhao C. CUL4B promotes the pathology of adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats through the canonical Wnt signaling. J Mol Med. 2018;96(6):495–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jameson SA, Lin Y-T, Capel B. Testis development requires the repression of Wnt4 by Fgf signaling. Dev Biol. 2012;370(1):24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jorgez CJ, Seth A, Wilken N, Bournat JC, Chen CH, Lamb DJ. E2F1 regulates testicular descent and controls spermatogenesis by influencing WNT4 signaling. Development. 2021;148(1):dev191189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang F, Richardson N, Albina A, Chaboissier M-C, Perea-Gomez A. Mouse gonad development in the absence of the pro-ovary factor WNT4 and the pro-testis factor SOX9. Cells. 2020;9(5):1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomizuka K, Horikoshi K, Kitada R, Sugawara Y, Iba Y, Kojima A, Yoshitome A, Yamawaki K, Amagai M, Inoue A, et al. R-spondin1 plays an essential role in ovarian development through positively regulating Wnt-4 signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(9):1278–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maatouk DM, Mork L, Chassot A-A, Chaboissier M-C, Capel B. Disruption of mitotic arrest precedes precocious differentiation and transdifferentiation of pregranulosa cells in the perinatal Wnt4 mutant ovary. Dev Biol. 2013;383(2):295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maatouk DM, DiNapoli L, Alvers A, Parker KL, Taketo MM, Capel B. Stabilization of beta-catenin in XY gonads causes male-to-female sex-reversal. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(19):2949–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicol B, Grimm SA, Gruzdev A, Scott GJ, Ray MK, Yao HHC. Genome-wide identification of FOXL2 binding and characterization of FOXL2 feminizing action in the fetal gonads. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27(24):4273–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jordan BK, Mohammed M, Ching ST, Délot E, Chen XN, Dewing P, Swain A, Rao PN, Elejalde BR, Vilain E. Up-regulation of WNT-4 signaling and dosage-sensitive sex reversal in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(5):1102–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan BK, Shen JHC, Olaso R, Ingraham HA, Vilain E. Wnt4 overexpression disrupts normal testicular vasculature and inhibits testosterone synthesis by repressing steroidogenic factor 1/beta-catenin synergy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):10866–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su AI, Wiltshire T, Batalov S, Lapp H, Ching KA, Block D, Zhang J, Soden R, Hayakawa M, Kreiman G, et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(16):6062–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hannah J, Zhou P. Distinct and overlapping functions of the cullin E3 ligase scaffolding proteins CUL4A and CUL4B. Gene. 2015;573(1):33–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen C-Y, Yu IS, Pai C-H, Lin C-Y, Lin S-R, Chen Y-T, Lin S-W. Embryonic Cul4b is important for epiblast growth and location of primitive streak layer cells. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7): e0219221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang B, Zhao W, Yuan J, Qian Y, Sun W, Zou Y, Guo C, Chen B, Shao C, Gong Y. Lack of Cul4b, an E3 ubiquitin ligase component, leads to embryonic lethality and abnormal placental development. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5): e37070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The variants have been submitted to ClinVar database [Accession numbers: SCV001737544 (CUL4B c.838 T > A: p. Leu280Met].