ABSTRACT

There is growing evidence that bacteria encountered in prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) form surface-attached biofilms on prostheses, as well as biofilm aggregates embedded in synovial fluid and tissues. However, in vitro models allowing the investigation of these biofilms and the assessment of their antimicrobial susceptibility in physiologically relevant conditions are currently lacking. To address this, we developed a synthetic synovial fluid (SSF2) model and validated this model by investigating growth, aggregate formation, and antimicrobial susceptibility using multiple PJI isolates belonging to various microorganisms. In this study, 18 PJI isolates were included belonging to Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Cutibacterium acnes, Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Candida spp. Growth and aggregate formation in SSF2 were evaluated using light microscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy. The biofilm preventing concentration (BPC) and minimal biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) of relevant antibiotics were determined using a resazurin-based viability staining. BPC and MBIC values were compared to conventional susceptibility parameters (minimal inhibitory concentration and minimal bactericidal concentration) determined with conventional approaches. The SSF2 medium allowed isolates to grow and form biofilm-like aggregates varying in size and shape between different species. For most isolates cultured in SSF2, a reduced susceptibility to the tested antibiotics was observed when compared to susceptibility data obtained in general media. These data indicate that the in vitro SSF2 model could be a valuable addition to evaluate the antimicrobial susceptibility of biofilm-like aggregates in the context of PJI.

IMPORTANCE

Infections after joint replacement are rare but can lead to severe complications as they are difficult to treat due to the ability of pathogens to form surface-attached biofilms on the prosthesis as well as biofilm aggregates in the tissue and synovial fluid. This biofilm phenotype, combined with the microenvironment at the infection site, substantially increases antimicrobial tolerance. Conventional in vitro models typically use standard growth media, which do not consider the microenvironment at the site of infection. By replacing these standard growth media with an in vivo-like medium, such as the synthetic synovial fluid medium, we hope to expand our knowledge on the aggregation of pathogens in the context of PJI. In addition, we believe that inclusion of in vivo-like media in antimicrobial susceptibility testing might be able to more accurately predict the in vivo susceptibility, which could ultimately result in a better clinical outcome after antimicrobial treatment.

KEYWORDS: prosthetic joint infection, synovial fluid, biofilms

INTRODUCTION

Due to an increased life expectancy, the number of total joint replacements, along with the risk on serious complications such as (peri)prosthetic joint infections (PJIs), continues to increase (1, 2). These infections are typically caused by unintentional inoculation during surgery or shortly thereafter and by hematogenous spread from adjacent tissues (3). The infecting pathogens most commonly found in PJI are Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci (e.g., Staphylococcus epidermidis). In addition, a smaller percentage of other microorganisms are also encountered in PJI, including Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., anaerobes (e.g., Cutibacterium acnes), Gram-negative rods such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli, and Candida spp. (4, 5). However, a considerable proportion of the cases remain culture negative, even when there are clear signs of infection (6).

PJIs are difficult to treat, as antibiotics often fail to reach the site of infection (7) and because of the ability of microorganisms to form surface-attached biofilms on prostheses (8), as well as biofilm-like aggregates embedded in synovial fluid and tissues (9). These biofilms are very hard to fully eradicate; hence, extraction of the prosthesis is often required (8). Components such as fibrinogen, hyaluronic acid, and albumin, present in human synovial fluid, induce biofilm-like aggregate formation in the synovial cavity (10, 11), and this biofilm phenotype, as well as the specific microenvironment (12), contributes to increased antimicrobial tolerance (13, 14). Several studies reported that biofilm-like aggregates formed by PJI pathogens in synovial fluid show a strongly reduced susceptibility toward antibiotics, both in in vitro and in ex vivo models (9, 11, 15, 16).

In clinical practice, the antimicrobial susceptibility of a pathogen is typically assessed by determining the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) using microbroth dilution or gradient strip methods or by disk diffusion; these assays are typically performed in standard growth media (17, 18). Whereas these tests can accurately predict the susceptibility of planktonic cells, they often fail to predict treatment success as they do not consider the impact of the biofilm phenotype and the infectious microenvironment on the antimicrobial susceptibility (12, 19). Indeed, the growth medium used is of great importance as it impacts gene expression profiles, and gene expression profiles of S. aureus differ markedly after cultivation in conventional growth media or in human synovial fluid (20). Furthermore, S. aureus gene expression in vitro differs from what is observed in vivo; e.g., genes involved in siderophore synthesis and multiple known virulence genes are upregulated in vivo (21).

One way to mimic the in vivo microenvironment in vitro is to use growth media that closely resemble the in vivo nutritional environment. In the present study, we developed a synthetic synovial fluid (SSF2) medium that simulates the microenvironment within the joints of PJI patients and can easily be integrated into in vitro testing. After initial optimization with an S. aureus PJI isolate, the model was further validated using multiple PJI isolates. Additionally, MICs and minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were determined using conventional approaches and compared to biofilm preventing concentrations (BPCs, i.e., the lowest concentration of an antibiotic required to fully prevent formation of a biofilm, including biofilm aggregates, starting from planktonic cells) and minimum biofilm inhibitory concentrations (MBICs, i.e., the lowest concentration of an antibiotic required to fully prevent the further development of a biofilm) (19) obtained in SSF2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates, culture conditions, and antibiotics

We included 18 clinical PJI isolates in the present study (Table S1), among which 7 isolates were recovered from PJI patients receiving care at the Ghent University Hospital. C. acnes isolates were cultured on reinforced clostridial medium (Lab M, Moss Hall, UK) for 48 h at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. Candida spp. were cultured on Sabouraud dextrose medium (Lab M) for 24 h at 37°C under aerobic conditions. The remaining isolates were grown on tryptic soy agar (TSA; Neogen, Heywood, UK), after cultivation at 37°C for 24 h or in Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB, Lab M) for 16 h at 37°C. For antimicrobial susceptibility testing, the following antibiotics were used: rifampicin, oxacillin, cefazolin, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, fluconazole, ciprofloxacin (all from Merck Life Science, Darmstadt, Germany), doxycycline (TCI, Europe, Zwijndrecht, Belgium), and vancomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For all antibiotics, stock solutions of 5 mg/mL were prepared, except for ciprofloxacin and rifampicin. For ciprofloxacin, a stock solution of 3.2 mg/mL with 70-µL 1-M HCl was prepared, and for rifampicin a stock solution of 0.5 mg/mL with 1% dimethylsulfoxide was prepared. All stock solutions were prepared in MilliQ water, filter sterilized (polyethersulfone (PES), 0.22 µm; VWR, Haasrode, Belgium) and stored at 4°C–7°C for a maximum of 1 week prior to use.

Development of the SSF1 and SSF2 medium

The composition of a first version of the SSF medium (SSF1) was based on the composition of human synovial fluid obtained from healthy individuals (22–26). Fibrinogen was subsequently added to the medium as it contributes to the synovial fluid-induced aggregate formation (10, 11, 27), leading to SSF2. Optimization was done by assessing the growth of S. aureus A1 in both media after 4, 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation at 37°C under aerobic, microaerophilic (3% O2, 5% CO2, 92% N2; Bactrox Hypoxic Chamber; SHEL-LAB, Cornelius, USA) and anaerobic conditions (5% H2, 5% CO2, 90% N2; Bactronez-2 Anaerobic Chamber, SHEL-LAB). Based on these results, the optimal composition (Table 1) and culture conditions for the SSF2 model were selected. A detailed protocol for the preparation of the SSF2 medium can be found in the supplemental data. When S. aureus A1 was cultured in SSF2, trypsin was required to disrupt the aggregates. To ensure that trypsin did not affect cell viability, planktonic cultures of all 18 PJI isolates were grown in MHB for 24 h at 37°C and were subjected to either a trypsin treatment (0.25%) or a conventional biofilm disruption by sonicating (5 min) and shaking (5 min, 900 rpm). Subsequently, a dilution series of both replicates (trypsin treatment and conventional biofilm disruption) were plated on the above-mentioned agar media. Colonies were counted after 24 h (48 h for C. acnes), and the number of CFU was calculated. Each experiment was conducted in duplicate and repeated three times, each time starting from a fresh pure culture.

TABLE 1.

Composition of the SSF2 medium

| Compound | Concentration |

|---|---|

| Glucose (g/L) | 1 |

| MgSO4 (mM) | 1 |

| CaCl2 (mM) | 0.3 |

| Nicotinic acid (mg/L) | 2 |

| Thiamine (mg/L) | 2 |

| Calcium panthothenate (mg/L) | 2 |

| Biotin (mg/L) | 0.1 |

| Citric acid (mg/L) | 24 |

| Bovine serum albumin (g/L) | 25 |

| Hyaluronic acid (1.20–1.80 MDa) (g/L) | 3 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 0.100 |

| Amino acids (mg/L) | |

| Alanine | 50.0 |

| Arginine | 8.9 |

| Asparagine | 12.0 |

| Aspartic acid | 8.8 |

| Cysteine | 20.0 |

| Glutamic acid | 38.0 |

| Glutamine | 76.0 |

| Glycine | 29.0 |

| Histidine | 18.0 |

| Isoleucine | 13.0 |

| Leucine | 27.0 |

| Lysine | 35.0 |

| Methionine | 4.3 |

| Phenylalanine | 16.0 |

| Proline | 28.0 |

| Serine | 20.0 |

| Threonine | 19.0 |

| Tryptophan | 14.0 |

| Tyrosine | 14.0 |

| Valine | 2.7.0 |

| Trace elements (mg/mL) | |

| FeCl3 | 4.98 |

| ZnCl2 | 0.89 |

| CuCl2 | 0.13 |

| CoCl2 | 0.09996 |

| H3BO3 | 0.0992 |

| MnCl2 | 0.016 |

| M9 salts (g/L) | |

| Na2HPO4·2H2O | 7.52 |

| KH2PO4 | 3.0 |

| NaCl | 0.5 |

| NH4Cl | 0.5 |

Evaluation of aggregate formation using light microscopy

Isolates were inoculated in 1 mL of SSF2 in a 24-well plate (F-bottom; Greiner Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany) with a final inoculum of 5 × 107 CFU/mL. After 24 h and 48 h of incubation at 37°C under microaerophilic (3% O2) or anaerobic conditions, aggregate formation was evaluated using the EVOS FL Auto Imaging System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) equipped with a 20 x objective.

Evaluation of aggregate formation in SSF2 using confocal laser scanning microscopy

High-resolution imaging by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) was carried out on aggregates formed in SSF2 by a selection of staphylococci (S. aureus SAU060112, S. aureus A1, Staphylococcus capitis subsp. capitis CCUG 39451, S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2). The selected strains were grown for 24 h in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (VWR international, Radnor, Pennsylvania, USA) at 37°C under shaking conditions (200 rpm). The cultures were subsequently inoculated in 200 µL of SSF2 in a µ-plate 96 Well Round Glass Bottom (Ibidi GmbH, Grädelfing, Germany) with a final inoculum of 2.6 × 108 CFU/mL. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C under static, aerobic conditions, the biofilms were stained by adding Live/Dead staining (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to a total concentration of 0.3 µL/mL of SYTO9 and propidium iodide (PI). After incubation for 15 min in the dark, the stained biofilms were imaged using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope with 63 x oil-based objective (Plan-Apochromat 63 x/1.4 Oil DIC M27, Carl Zeiss) and an Airyscan Detector (Carl Zeiss NV, Zaventem, Belgium). Images were acquired with a resolution of 85 nm in the x- and y-direction and 182 nm in the z-direction in the FastAiryscan mode using 488 nm and 561 nm lasers for the SYTO0 and PI respectively.

Biofilm quantification in SSF2 model

Isolates were grown in SSF2 in a 96-well plate (U-bottom, Greiner Bio-One) with a final inoculum of 5 × 107 CFU/mL in a volume of 100 µL and incubated at 37°C under microaerophilic (3% oxygen) or anaerobic conditions for 24 or 48 h. Subsequently, aggregates were disrupted using a 0.25% trypsin EDTA solution (Life Technologies). To this end, the supernatant was removed after centrifuging the plates for 15 min at 3,700 rpm; 100 µL of trypsin was added to the pelleted aggregates; and the plates were incubated for 20 min at 37°C. Thereafter, the plates were centrifuged again for 15 min at 3,700 rpm. Trypsin was then removed and the bacterial cells were resuspended in physiological saline and dilution series were plated on the above-mentioned agar media. Colonies were counted after 24 h of incubation (48 h for C. acnes), and the number of CFU was calculated. Each experiment was conducted in duplicate and repeated three times, each time starting from a fresh pure culture.

Determination of MICs and MBCs

The MIC and MBC of all isolates were determined according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing guidelines (17) for a broad range of relevant antibiotics commonly used in the treatment of PJI (Table S2) (28). For the MIC determination, an inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/mL was incubated for 24 h at 37°C in the presence of a serial dilution of antibiotics in a final volume of 200 µL under static conditions. MBCs were determined by plating the entire contents of the wells containing the MIC and the four subsequent wells containing higher antibiotic concentrations on the above-mentioned agar media. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, the lowest antibiotic concentration that prevented growth was considered as MBC. The highest antimicrobial concentrations tested were based on solubility and clinical relevance and are shown in Table S3. Each experiment was conducted in duplicate and repeated three times, each time starting from a fresh pure culture. Median values of these triplicates were used as MIC and MBC values for subsequent data analysis.

Determination of BPCs and MBICs

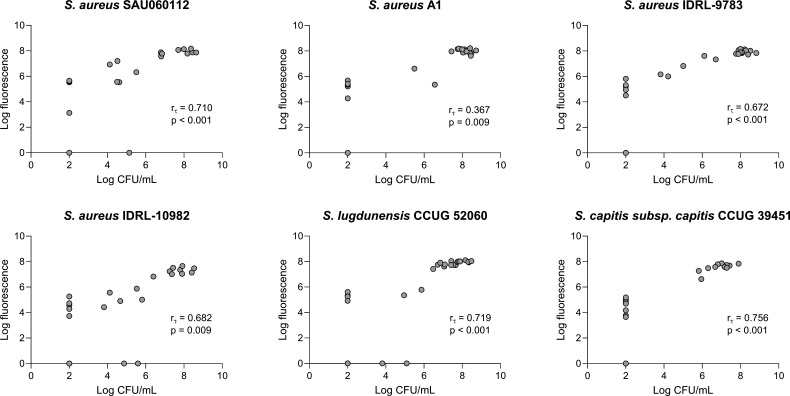

For the BPC determination, overnight cultures were diluted to a final inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/mL in a 96-well plate (U-bottom) containing serial twofold dilutions of the different antibiotics in SSF2, with a final volume of 200 µL. Non-treated controls (containing only bacteria in SSF2) and blanks (containing only SSF2) were included in each experiment. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, under microaerophilic (3% oxygen) conditions, biofilms were disrupted using trypsin treatment as described above. For the determination of the MBIC, biofilms were first grown in SSF2 for 24 h at 37°C, under microaerophilic (3% oxygen) conditions in the absence of antibiotics. The biofilms were then treated with serial twofold dilutions of the different antibiotics (prepared in SSF2 in a separate 96-well plate) and subsequently incubated for another 24 h. Staining with resazurin (CellTiter-Blue [CTB]) (Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands) was used to determine the BPC and MBIC. The resazurin solution was prepared by diluting 2.1-mL stock solution of CTB with 10.5-mL physiological saline (0.9% NaCl). One hundred twenty microliters of this CTB solution was added to each well. Plates were covered from the light and incubated for 20 min–1 h, depending on species, at 37°C under static conditions. Using a Viktor Nivo plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, USA), the fluorescence was measured (excitation wavelength: 560 nm and emission wavelength: 590 nm). The BPC and MBIC were defined as the lowest concentration of an antibiotic that reduces the resazurin-derived fluorescence with at least 90% compared to a non-treated control after 24 h of exposure to the antibiotics. To ensure that the resazurin staining is a reliable alternative to determine these biofilm parameters, a correlation analysis was performed on the fluorometric values and CFU counts of six isolates that were treated with oxacillin (ie., S. aureus A1, SAU060112, IDRL-9783, IDRL-10982, Staphylococcus lugdunensis CCUG52060, and S. capitis subsp. capitis CCUG39451). More specifically, after measuring the resazurin-derived fluorescence of all conditions, the content of all wells was plated in parallel on TSA. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, colonies were counted and the number of CFU was calculated. All experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated three times, each time starting from a fresh pure culture.

Statistical analysis

To check whether CFU counts obtained after incubation in the two different SSF media differed from each other and from the CFU counts obtained after trypsin treatment, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test (with Bonferroni correction) was performed for normally distributed data, and the non-parametric one-way ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis test was used for non-normally distributed data. To check whether CFU counts were affected by trypsin treatment, an independent sample t-test was performed for normally distributed data, and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data. Normal distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. To determine whether CTB-derived fluorescence can be used as an alternative to plating for determining the number of CFU, Kendall’s tau correlations (rτ) between fluorescence and CFU counts were calculated (29, 30). Values for non-treated controls were also included. Datapoints below the limit of detection, i.e., fluorescence values equal to 1 and CFU counts less or equal to 102 CFU/mL, were excluded. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software (version 28, IBM, New York, USA).

RESULTS

Fibrinogen as a key component in synovial fluid-induced aggregate formation of S. aureus

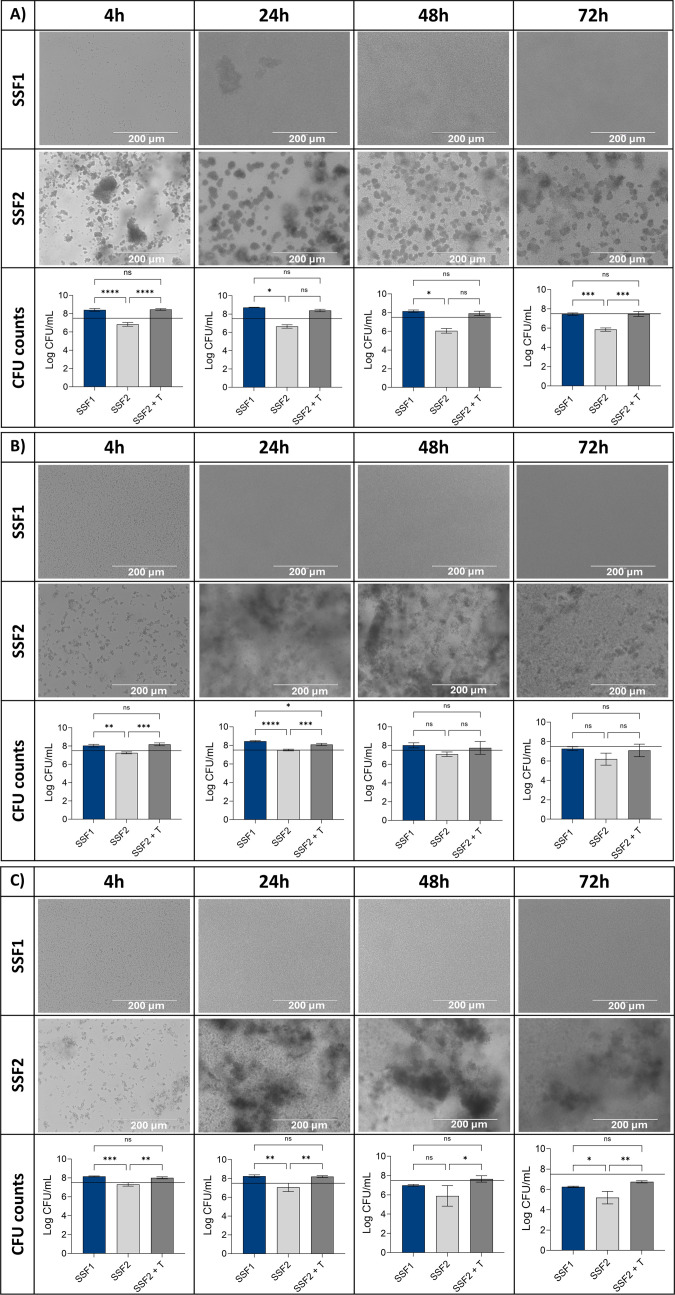

To assess the effect of including fibrinogen in the medium, growth and aggregate formation of S. aureus A1 were checked after 4, 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation in SSF1 (without fibrinogen) and SSF2 (supplemented with fibrinogen), at different oxygen levels (Fig. 1). S. aureus A1 showed growth in SSF1 at all oxygen levels after 4 and 24 h of incubation. Under microaerophilic and anaerobic conditions, CFU counts dropped below the inoculum size after 48 h of incubation in SSF1. After 72 h of incubation in SSF1, CFU counts dropped below the inoculum size at all oxygen levels tested. Light microscopy images show growth at all oxygen levels, at all timepoints; however, no aggregate formation was observed in SSF1. Surprisingly, when CFU counts were determined after incubation in SSF2 at varying oxygen levels, no growth was observed; however, light microscopy indicated the presence of S. aureus A1 aggregates in SSF2. We hypothesized that the intracellular interactions within the aggregates were too strong to disrupt the aggregates using conventional biofilm disruption approaches, and for this reason, a trypsin treatment was introduced. Following trypsin treatment, CFU counts after growth in SSF2 no longer significantly differed from the CFU counts found after incubation in SSF1. As a consequence, trypsin treatment was introduced in all further experiments to quantify aggregate formation in SSF2. We checked whether trypsin treatment affected the cell viability of all PJI isolates included in this study, but no significant differences were observed between CFU counts obtained after conventional biofilm disruption when compared to CFU counts obtained after trypsin treatment (Fig. S1).

Fig 1.

Light microscopy images of clinical S. aureus isolate A1 cultured in SSF without Fg (SSF1) and SSF with Fg (SSF2) under aerobic (A), microaerophilic (3% O2) (B), and anaerobic (C) conditions, evaluated at four different timepoints. The bars represent the average number (n = 3) of CFUs recovered after conventional biofilm disruption for biofilms grown in SSF1 (blue) and SSF2 (light gray) or after biofilm disruption using trypsin (0.25%) after growth in SSF2 (dark gray). Error bars indicate standard deviation; black line indicates the inoculum of 5 × 107 CFU/mL. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. ns, not significant (P ≥ 0.05).

SSF2 model allows growth and aggregate formation of different PJI isolates

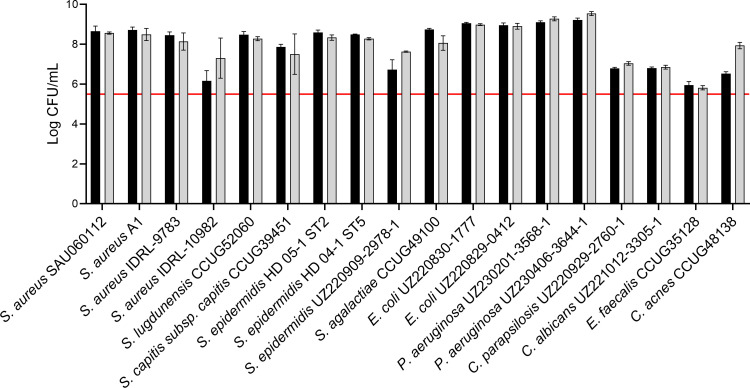

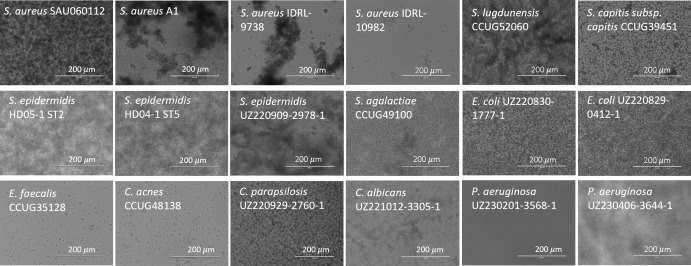

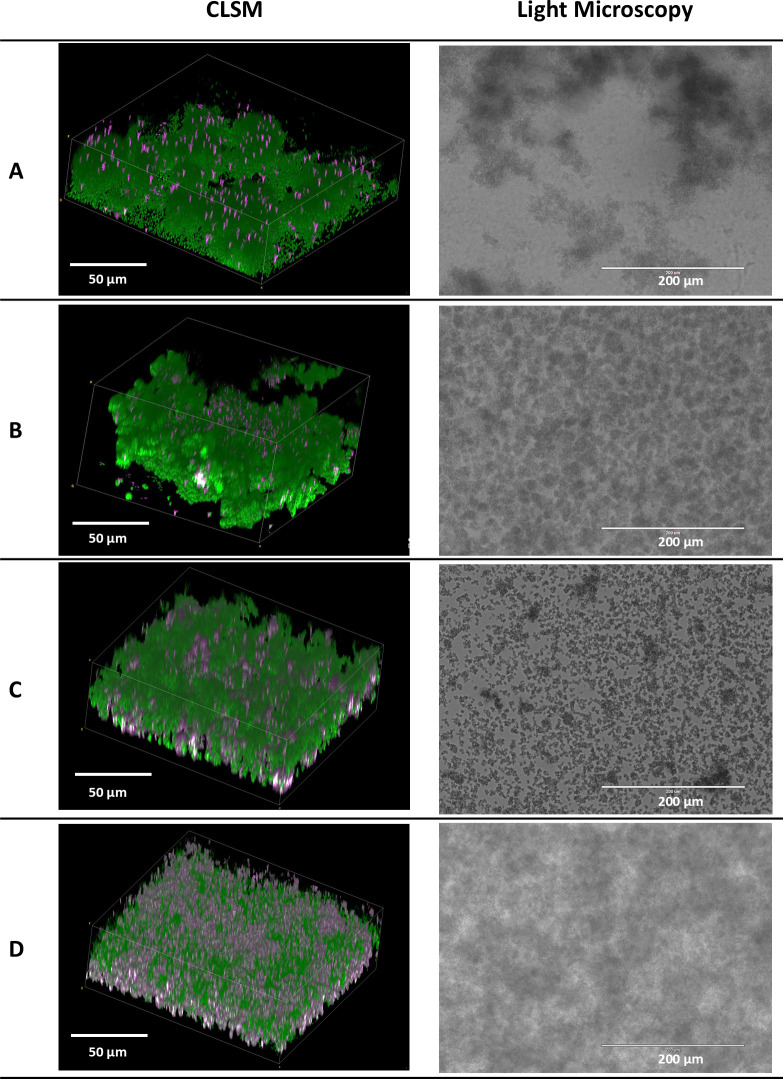

Subsequently, growth and aggregate formation of the 18 isolates included in this study were assessed in the SSF2 medium. Fifteen out of the 18 isolates grew well in SSF2 after 48 h of incubation under microaerophilic conditions (anaerobic conditions for C. acnes), with an increase of at least 2 log CFU/mL (Fig. 2) compared to the inoculum. The Gram-negative bacteria included, as well as some of the staphylococci (S. aureus SAU060112 and A1, S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2 and HD04-1 ST5), showed the strongest increase of at least 3 log CFU/mL after 48 h of incubation compared to the inoculum. For the other staphylococci, Streptococcus agalactiae and C. acnes, an increase between 2.0 and 2.5 log CFU/mL was observed after 48 h of incubation. The growth of the Candida spp. was less pronounced (increase of 1.5 CFU/mL). No growth was observed only for Enterococcus faecalis after 48 h. Light microscopy showed that all staphylococci form large, clustered aggregates, except S. aureus IDRL-10982, for which a lower number of small aggregates was observed (Fig. 3). The number of aggregates formed by E. faecalis and C. acnes was lower, and their volume was less dense than for the other isolates. For the remaining isolates, a high density of cells was observed, and aggregates differed in size and shape from the staphylococcal aggregates. P. aeruginosa UZ230201-3568-1 was the only isolate for which no aggregate formation was observed (Fig. 3). A more detailed morphological evaluation was carried out on a selection of staphylococci cultured in SSF2, using CLSM following Live/Dead staining (Fig. 4). Overall, the CLSM images corroborate the findings using light microscopy. S. aureus A1, S. aureus SAU060112, and S. capitis formed dense clusters interspersed with regions of lower cell density, whereas S. epidermidis formed a confluent layer covering the entire surface. The biofilms consisted mostly of live cells, with dead cells primarily found in the bottom layer of the S. capitis and S. epidermidis biofilms.

Fig 2.

Log CFU per milliliter values of 18 clinical PJI isolates after 24 h (black bars) and 48 h (gray bars) of incubation in SSF2 under microaerophilic conditions (3% O2), except for C. acnes (anaerobic conditions). Inoculum size: 5 × 105 CFU/mL (red line). Data shown are mean values of biological replicates; error bars represent standard deviations (n = 3).

Fig 3.

Light microscopy images of 18 clinical PJI isolates after 24 h of incubation in SSF2 under microaerophilic conditions (3% O2), except for C. acnes (anaerobic conditions). Scale bars 200 µm.

Fig 4.

CLSM (left) and light microscopy (right) images of four of the staphylococci. (A) S. aureus A1, (B) S. aureus SAU060112, (C) S. capitis subsp. capitis CCUG 39451, and (D) S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2, after 24 h of incubation in SSF2. CLSM: scale bars 50 µm; light microscopy: scale bars 200 µm. The contrast was adjusted to improve visualization. The light microscopy images shown (on the right) are the same as the ones shown in Fig. 3 for the four strains mentioned.

Resazurin staining as a reliable alternative quantification approach

Subsequently, we investigated whether resazurin could be used for quantification of growth in SSF2. This was done using biofilm aggregates formed by S. aureus A1, SAU060112, IDRL-9783, IDRL-10982, S. lugdunensis CCUG52060, and S. capitis subsp. capitis CCUG39451 that were exposed to increasing oxacillin concentrations (ranging from 0.25 to 256 µg/mL). A significant (P < 0.05) and strong (rτ ≥0.3) correlation between the fluorescence values and CFU values (both log-transformed) was found (Fig. 5) (30).

Fig 5.

Relation between log CFU per milliliter values and log fluorescence values after resazurin staining. Data are shown for all the replicates tested (n = 3).

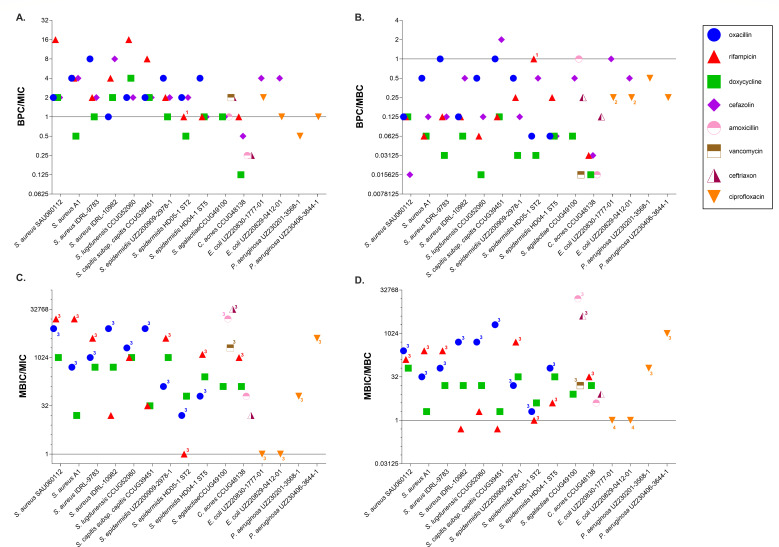

Biofilm susceptibility parameters (BPC and MBIC) differ markedly from conventional susceptibility parameters (MIC and MBC)

MIC, MBC, BPC, and MBIC values of the different antibiotics for the 18 PJI isolates investigated are shown in Table 2. For cefazolin, the MBIC was not determined, as this antibiotic is traditionally administered as prophylactic before surgery; hence, only the BPC was determined. Due to intrinsic resistance of P. aeruginosa and Candida spp. to cefazolin, corresponding BPCs and MBICs were not determined. Likewise, given that the MIC and MBC of fluconazole for both Candida spp. strains exceeded the highest test concentration (512 µg/mL), the BPC and MBIC were not determined. Finally, for E. faecalis, BPCs and MBICs were not determined as this isolate did not grow in the SSF2 medium. The biofilm susceptibility data are expressed relative to the planktonic susceptibility data (i.e., relative to MIC and MBC) (Fig. 6). In some cases, an exact ratio could not be determined as at least one of the parameters had a value that was outside the testing range (i.e., higher than the highest test concentration or lower than the lowest test concentration).

TABLE 2.

Overview of median MICs, MBCs, BPCs, and MBICs (in µg/mL) of the different antibiotics for the 18 clinical PJI isolates investigateda

| MIC | MBC | BPC | MBIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxacillin | ||||

| S. aureus SAU060122 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.5 | >1,024 |

| S. lugdunensis CCUG 52060 | 1 | 2 | 1 | >1,024 |

| S. capitis subsp. capitis CCUG 39451 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | >1,024 |

| S. aureus A1 | 4 | 32 | 16 | >1,024 |

| S. aureus IDRL-9783 | 2 | 16 | 16 | >1,024 |

| S. aureus IDRL-10982 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.25 | >1,024 |

| S. epidermidis UZ220909-2978-1 | 8 | 64 | 32 | >1,024 |

| S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2 | 64 | 512 | 32 | >1,024 |

| S. epidermidis HD04-1 ST5 | 16 | 256 | 64 | >1,024 |

| Rifampicin | ||||

| S. aureus SAU060122 | 0.001953 | 0.25 | 0.03125 | >32 |

| S. lugdunensis CCUG 52060 | 0.000977 | 0.25 | 0.015625 | 0.5 |

| S. capitis subsp. capitis CCUG 39451 | 0.003906 | 0.25 | 0.03125 | 0.125 |

| S. aureus A1 | 0.001953 | 0.125 | 0.0078125 | >32 |

| S. aureus IDRL-9783 | 0.0078125 | 0.125 | 0.015625 | >32 |

| S. aureus IDRL-10982 | 0.003906 | 0.125 | 0.015625 | 0.0625 |

| S. epidermidis UZ220909-2978-1 | 0.0078125 | 0.0625 | 0.015625 | >32 |

| S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2 | 32 | 32 | >32 | >32 |

| S. epidermidis HD04-1 ST5 | 0.025 | 0.5 | 0.03125 | >32 |

| C. acnes CCUG 48138 | 0.03125 | 1 | 0.015625 | >32 |

| Doxycyclin | ||||

| S. aureus SAU060122 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.5 | 256 |

| S. lugdunensis CCUG 52060 | 0.125 | 8 | 0.125 | 128 |

| S. capitis subsp. capitis CCUG 39451 | 4 | 64 | 8 | 128 |

| S. aureus A1 | 16 | 128 | 8 | 256 |

| S. aureus IDRL-9783 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.25 | 128 |

| S. aureus IDRL-10982 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.5 | 128 |

| S. epidermidis UZ220909-2978-1 | 0.125 | 4 | 0.125 | 32 |

| S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2 | 2 | 32 | 1 | 128 |

| S. epidermidis HD04-1 ST5 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.25 | 128 |

| S. agalactiae CCUG 49100 | 8 | 128 | 8 | 1,024 |

| E. faecalis CCUG 35182 | 4 | 128 | ND | ND |

| C. acnes CCUG 48138 | 2 | 16 | 0.25 | 256 |

| Cefazolin | ||||

| S. aureus SAU060122 | 0.25 | 32 | 0.5 | ND |

| S. lugdunensis CCUG 52060 | 0.5 | 8 | 1 | ND |

| S. capitis subsp. capitis CCUG 39451 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ND |

| S. aureus A1 | 1 | 32 | 4 | ND |

| S. aureus IDRL-9783 | 2 | 32 | 4 | ND |

| S. aureus IDRL-10982 | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | ND |

| S. epidermidis UZ220909-2978-1 | 4 | 64 | 8 | ND |

| S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2 | 64 | 256 | 128 | ND |

| S. epidermidis HD04-1 ST5 | 4 | 64 | 4 | ND |

| S. agalactiae CCUG 49100 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | ND |

| E. faecalis CCUG 35182 | 32 | 1024 | ND | ND |

| C. acnes CCUG 48138 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.25 | ND |

| E. coli UZ300822-0412-1 | 8 | 32 | 32 | ND |

| E. coli UZ290822-1777-1 | 8 | 64 | 32 | ND |

| P. aeruginosa UZ230201-3568-1 | >1,024 | >1,024 | ND | ND |

| P. aeruginosa UZ230406-3644-1 | >1,024 | >1,024 | ND | ND |

| Candida parapsilosis UZ220929-2760-1 | >1,024 | >1,024 | ND | ND |

| Candida albicans UZ221012-3305-1 | >1,024 | >1,024 | ND | ND |

| Amoxicillin | ||||

| S. agalactiae CCUG 49100 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 | >1,024 |

| E. faecalis CCUG 35182 | 4 | 4 | ND | ND |

| C. acnes CCUG 48138 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.0625 | 16 |

| Vancomycin | ||||

| S. agalactiae CCUG 49100 | 0.5 | 64 | 1 | >1,024 |

| E. faecalis CCUG 35182 | 1 | 1 | ND | ND |

| Ceftriaxon | ||||

| S. agalactiae CCUG 49100 | 0.03125 | 0.25 | 0.0625 | >1,024 |

| E. faecalis CCUG 35182 | 512 | >1,024 | ND | ND |

| C. acnes CCUG 48138 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.125 | 8 |

| Ciprofloxacin | ||||

| E. coli UZ300822-0412-1 | 128 | >1,024 | 256 | >1,024 |

| E. coli UZ290822-1777-1 | 256 | >1,024 | 256 | >1,024 |

| P. aeruginosa UZ230201-3568-1 | 16 | 16 | 8 | >1,024 |

| P. aeruginosa UZ230406-3644-1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | >1,024 |

| Fluconazole | ||||

| C. parapsilosis UZ220929-2760-1 | >512 | >512 | ND | ND |

| C. albicans UZ221012-3305-1 | >512 | >512 | ND | ND |

ND, not determined.

Fig 6.

BPC:MIC ratios (A), BPC:MBC ratios (B), MBIC:MIC ratios (C), and MBIC:MBC ratios (D) for all antibiotics tested. The solid black line indicates a ratio of 1. Data points for which an exact ratio could not be determined because one or both parameters are outside the testing range are labeled: (1) BPC >testing range, (2) MBC >testing range, (3) MBIC >testing range, and (4) MBIC >testing range and MBC <testing range.

In most cases, the BPC:MIC ratio was higher than 1 (64%) (fold difference between 2 and 16) (Fig. 6A). In 24% of the susceptibility tests, the BPC:MIC ratio was equal to 1 (i.e., the BPC equaled the MIC). The BPC was lower than the MIC in 12% of the cases, more specifically for S. aureus A1 and S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2 and doxycycline (BPC twofold lower than MIC): the BPCs of all antibiotics tested for C. acnes CCUG48138 were smaller than corresponding MICs (two- to fourfold difference), and finally, the BPC of ciprofloxacin for P. aeruginosa UZ230201-3568-1 was two times lower than its MIC. The BPC was lower than the MBC in 86% of the cases, and the extent of this difference varied between 2- and 64-fold (Fig. 6B). The BPCs of oxacillin for S. capitis subsp. capitis CCUG39451 and S. aureus IDRL-9783, of rifampicin for S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2, of amoxicillin for S. agalactiae CCUG49100, and of cefazolin for E. coli UZ220830-1777-1 were equal to the MBC (12%). The BPC of cefazolin exceeded the MBC (2%) (twofold difference) only for S. capitis subsp. capitis.

In the majority of the cases, the MBIC exceeded the MIC (91.5%), except for the combinations rifampicin/S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2, ciprofloxacin/E. coli UZ220830-1777-01, and ciprofloxacin/E. coli UZ220829-0412-01 (Fig. 6C). For these combinations (8.5%), at least one of the susceptibility parameters was outside the testing range, and as a consequence, an exact ratio could not be determined. The extent to which the MBIC differed from the MIC in the other cases was much larger than the difference between BPC and MIC, ranging from 16- to 16,384-fold differences. The MBIC exceeded the MBC in most of the cases (86.5%), and the extent of this difference varied between 2- and 4,096-fold (Fig. 6D). However, for 13.5% of the combinations (rifampicin/S. epidermidis HD05-1 ST2, rifampicin/S. lugdunensis CCUG52060, rifampicin/S. aureus IDRL-9783 ciprofloxacin/E. coli UZ220830-1777-01, and ciprofloxacin/E. coli UZ220829-0412-01), at least one of the susceptibility parameters was outside the testing range, and as a consequence, an exact ratio could not be determined.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to develop an SSF model that closely mimics the nutritional microenvironment within the joints of patients with PJI and to validate this model in terms of growth, aggregate formation, and antimicrobial susceptibility. To do so, growth and aggregate formation of the clinical isolate S. aureus A1 were determined after incubation in SSF media with and without fibrinogen, at different oxygen levels, and with/without trypsin treatment. Aggregate formation of S. aureus A1 was only observed in the SSF2 medium supplemented with fibrinogen, indicating fibrinogen is crucial for the aggregatory phenotype of bacteria in synovial fluid. Previous studies have shown that the presence of fibrinogen in human synovial fluid causes bacterial aggregation (15, 31), and proteolytic enzymes are required to disrupt these aggregates (10). Indeed, after treating the aggregates with trypsin, a statistically significant increase in CFU counts was observed. For this reason, we selected the SSF2 medium with fibrinogen and included trypsin treatment in further experiments to disperse aggregates before quantifying bacteria post-incubation. At the site of infection, bacteria are typically exposed to hypoxic conditions, impacting bacterial properties (32). Therefore, microaerophilic conditions (3% O2) were chosen to better mimic the in vivo situation for further experiments (except for C. acnes, for which anaerobic conditions were used). Light microscopy demonstrated that nearly all isolates formed aggregates after incubation in SSF2, varying in size, shape, and density across isolates. Only P. aeruginosa UZ230201-3568-1 did not form aggregates, possibly due to its mucoid phenotype. Furthermore, analysis of the three-dimensional structures of a selection of staphylococci by CLSM confirmed the light microscopy findings. Whereas multiple studies showed that synovial fluid induced aggregation of S. aureus (31, 33), only a few studies demonstrated aggregate formation in synovial fluid of other PJI pathogens, including coagulase-negative staphylococci, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa (9, 16). CFU counts indicated all isolates grew well in SSF2, except for E. faecalis CCUG35128. Nevertheless, light microscopy revealed small aggregates of E. faecalis CCUG35128 were present after 24 h of incubation in SSF2. Recently, a study demonstrated that simulated synovial fluid induces aggregate formation but reduces growth of E. faecalis when compared to standard media. These findings suggest synovial fluid media compromise the viability of E. faecalis or prohibit acquisition of critical nutrients for their survival (34). Resazurin staining was used to determine the BPC and MBIC, offering a rapid alternative to plating. Our results show there is a significant and strong correlation between CFU counts and resazurin-derived fluorescence for staphylococci, which is consistent with findings from prior research (35, 36). Over the past years, multiple studies on susceptibility testing in synovial fluid media have been reported, all concluding that the use of synovial fluid media alters the antimicrobial efficacy in vitro when compared to conventional susceptibility testing (9, 11, 16, 20, 34, 37). Comparing results across studies is difficult because different types of synovial fluid media were used. Besides human and animal synovial fluid (9, 11, 16, 20, 37) that are typically used for in vitro experiments, other synthetic synovial fluid media have been developed to better mimic the in vivo microenvironment in PJI, including simulated synovial fluid (34) and artificial synovial fluid (38). However, both of these lack fibrinogen, while the latter medium, derived from human plasma, also lacks hyaluronic acid, essential for the viscous properties of synovial fluid. In the present study, we have confirmed that fibrinogen plays an essential role in synovial fluid-induced aggregation and therefore should be included in synthetic media mimicking synovial fluid. One of the limitations of this medium is the fact that its composition does not perfectly reflect the composition of synovial fluid encountered in the diseased joints of PJI patients. It is well established that the proteome (including albumin and fibrinogen expression) (39, 40) and hyaluronic acid structure (41) in healthy joints is distinct from the ones observed in osteoarthritic joints and fluctuates in osteoarthritic joints as well (39). This makes that these concentrations are hard to duplicate in vitro. Therefore, we opted for a composition based on healthy synovial fluid, incorporating only the minimal fibrinogen concentration required for bacterial aggregation, as this aligns with our research focus. As mentioned above, it is also possible to use human or animal synovial fluid, which may more closely resemble the in vivo proteome. Nevertheless, their use comes with several disadvantages, such as the risk of contamination and the burden of ethical concerns. In addition, the exact composition of these synovial fluids is not known and is likely to vary from individual to individual, making standardization very difficult (42, 43). Using the resazurin-based viability staining and SSF2, we observed BPC values were mostly higher than MIC values, while this was always the case for MBIC values. BPC values were almost always lower than the MBC, while MBIC values were consistently higher than the MBC (with a few exceptions). Notably, for C. acnes CCUG48138, the BPC of the five antibiotics tested was consistently lower than the MIC; however, the corresponding MBIC values were much higher than MIC (and BPC) values. To date, only data on surface-attached C. acnes biofilms, established in general growth media in in vitro models, are available. These data indicate that C. acnes biofilms contribute to a reduced antimicrobial susceptibility in vivo (44). Yet, why antimicrobial concentrations to prevent biofilm formation by C. acnes in our SSF2 medium are lower than the one to inhibit planktonic growth remains unclear. For the staphylococci included, the BPC:MIC ratios and MBIC:MIC ratios of rifampicin were not significantly lower than the ratios of the other antibiotics tested, while rifampicin is considered as a “biofilm-active” antibiotic, typically recommended for the treatment of difficult-to-treat PJI caused by staphylococci (45). Nevertheless, there has been some debate concerning the added value of rifampicin for the treatment of PJI (46, 47). It should be noted that exact MBIC values could not be determined in several cases, as they exceeded the highest test concentrations, which were already much higher than concentrations achievable in vivo.

In summary, by mimicking essential features of the nutritious microenvironment we can replicate the aggregatory phenotype of multiple pathogens in the context of PJI. Moreover, it is anticipated that the response of these PJI pathogens to antimicrobials using this approach is more predictive of real-life susceptibility. Whether the use of the SSF2 medium as an alternative culture medium for in vitro susceptibility testing will facilitate antimicrobial treatment selection and ultimately lead to a better clinical outcome remains to be evaluated by follow-up studies, including a larger number of isolates and linking this to clinical data. Studies investigating the relationship between biofilm susceptibility and clinical outcomes in staphylococcal PJI have yielded varied results. Increased antimicrobial tolerance observed in vitro does not consistently correlate with poorer clinical outcomes and vice versa (48–50). However, it is important to note that these studies were performed using the Calgary Biofilm device, where biofilms are grown on the surface of plastic pegs in standard growth media (51), which does not reflect the situation in vivo. The in vivo-like SSF2 medium developed in the present study enables the investigation of the biofilm-like aggregation of a variety of PJI pathogens, and it offers a robust alternative to conventional in vitro models for testing the antimicrobial susceptibility of these aggregates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Holger Rohde (Institute of Medical Microbiology, Virology and Hygiene, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for providing the Staphylococcus epidermidis HD04-1 ST2 and HD02-1 ST5 isolates, Trine Rolighed Thomsen (Center for Microbial Communities, Department of Chemistry and Bioscience, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark) for providing the Staphylococcus aureus SAU060112 isolate, and Robin Patel (Division of Clinical Microbiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA) for providing the S. aureus IDRL-9783 and IDRL-10982 isolates. In addition, we thank Petra Rigole, Inne Dhondt, Valérie Vandendriessche, and William Van Vlierberghe for help with the experiments.

This work was supported by Research Foundation–Flanders (FWO) (grant G066523N; to T.C., J.B., and H.S.) and a study group research grant from the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (to T.C. and F.R.). T.C. and H.S. are part of the FWO-funded Scientific Research Network "Biology and Ecology of Bacterial and Fungal Biofilms in Humans" (grant W000921N).

Contributor Information

Tom Coenye, Email: tom.coenye@ugent.be.

Cristina Solano, Navarrabiomed-Universidad Pública de Navarra (UPNA)-Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra (CHN), IdiSNA, Pamplona, Navarra, Spain.

ETHICS APPROVAL

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ghent University Hospital (registration number BC-08886 AM2).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01980-24.

Supplemental tables, figure, and full protocol.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Patel R. 2023. Periprosthetic joint infection. N Engl J Med 388:251–262. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2203477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. 2004. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med 351:1645–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barrett L, Atkins B. 2014. The clinical presentation of prosthetic joint infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:i25–i27. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tai DBG, Patel R, Abdel MP, Berbari EF, Tande AJ. 2022. Microbiology of hip and knee periprosthetic joint infections: a database study. Clin Microbiol Infect 28:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aggarwal VK, Bakhshi H, Ecker NU, Parvizi J, Gehrke T, Kendoff D. 2014. Organism profile in periprosthetic joint infection: pathogens differ at two arthroplasty infection referral centers in Europe and in the United States. J Knee Surg 27:399–406. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1364102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Palan J, Nolan C, Sarantos K, Westerman R, King R, Foguet P. 2019. Culture-negative periprosthetic joint infections. EFORT Open Rev 4:585–594. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shao H, Zhou Y. 2023. Management of soft tissues in patients with periprosthetic joint infection. Arthropl 5:52. doi: 10.1186/s42836-023-00205-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brooks JR, Chonko DJ, Pigott M, Sullivan AC, Moore K, Stoodley P. 2023. Mapping bacterial biofilm on explanted orthopedic hardware: an analysis of 14 consecutive cases. APMIS 131:170–179. doi: 10.1111/apm.13295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bidossi A, Bottagisio M, Savadori P, De Vecchi E. 2020. Identification and characterization of planktonic biofilm-like aggregates in infected synovial fluids from joint infections. Front Microbiol 11:1368. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knott S, Curry D, Zhao N, Metgud P, Dastgheyb SS, Purtill C, Harwood M, Chen AF, Schaer TP, Otto M, Hickok NJ. 2021. Staphylococcus aureus floating biofilm formation and phenotype in synovial fluid depends on albumin, fibrinogen, and hyaluronic acid. Front Microbiol 12:655873. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.655873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Staats A, Burback PW, Casillas-Ituarte NN, Li D, Hostetler MR, Sullivan A, Horswill AR, Lower SK, Stoodley P. 2023. In vitro staphylococcal aggregate morphology and protection from antibiotics are dependent on distinct mechanisms arising from postsurgical joint components and fluid motion. J Bacteriol 205:e0045122. doi: 10.1128/jb.00451-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bjarnsholt T, Whiteley M, Rumbaugh KP, Stewart PS, Jensen PØ, Frimodt-Møller N. 2022. The importance of understanding the infectious microenvironment. Lancet Infect Dis 22:e88–e92. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00122-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ciofu O, Moser C, Jensen PØ, Høiby N. 2022. Tolerance and resistance of microbial biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:621–635. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00682-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Acker H, Van Dijck P, Coenye T. 2014. Molecular mechanisms of antimicrobial tolerance and resistance in bacterial and fungal biofilms. Trends Microbiol 22:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dastgheyb S, Parvizi J, Shapiro IM, Hickok NJ, Otto M. 2015. Effect of biofilms on recalcitrance of staphylococcal joint infection to antibiotic treatment. J Infect Dis 211:641–650. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilbertie JM, Schnabel LV, Hickok NJ, Jacob ME, Conlon BP, Shapiro IM, Parvizi J, Schaer TP. 2019. Equine or porcine synovial fluid as a novel ex vivo model for the study of bacterial free-floating biofilms that form in human joint infections. PLoS One 14:e0221012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leclercq R, Cantón R, Brown DFJ, Giske CG, Heisig P, MacGowan AP, Mouton JW, Nordmann P, Rodloff AC, Rossolini GM, Soussy C-J, Steinbakk M, Winstanley TG, Kahlmeter G. 2013. EUCAST expert rules in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect 19:141–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kahlmeter G, Brown DFJ, Goldstein FW, MacGowan AP, Mouton JW, Osterlund A, Rodloff A, Steinbakk M, Urbaskova P, Vatopoulos A. 2003. European harmonization of MIC breakpoints for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:145–148. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coenye T. 2023. Biofilm antimicrobial susceptibility testing: where are we and where could we be going? Clin Microbiol Rev 36:e0002423. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00024-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steixner SJM, Spiegel C, Dammerer D, Wurm A, Nogler M, Coraça-Huber DC. 2021. Influence of nutrient media compared to human synovial fluid on the antibiotic susceptibility and biofilm gene expression of coagulase-negative Staphylococci in vitro. Antibiotics (Basel) 10:790. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10070790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu Y, Maltesen RG, Larsen LH, Schønheyder HC, Le VQ, Nielsen JL, Nielsen PH, Thomsen TR, Nielsen KL. 2016. In vivo gene expression in a Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection characterized by RNA sequencing and metabolomics: a pilot study. BMC Microbiol 16:80. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0695-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McNearney TA, Westlund KN. 2013. Excitatory amino acids display compartmental disparity between plasma and synovial fluid in clinical arthropathies. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 6:492–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Costello LC, Franklin RB. 2016. Plasma citrate homeostasis: how it is regulated; and its physiological and clinical implications. An important, but neglected, relationship in medicine. HSOA J Hum Endocrinol 1:005. doi: 10.24966/HE-9640/100005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cowman MK, Lee HG, Schwertfeger KL, McCarthy JB, Turley EA. 2015. The content and size of hyaluronan in biological fluids and tissues. Front Immunol 6:261. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cretu D, Diamandis EP, Chandran V. 2013. Delineating the synovial fluid proteome: recent advancements and ongoing challenges in biomarker research. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 50:51–63. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2013.802408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schmidt JA, Rinaldi S, Scalbert A, Ferrari P, Achaintre D, Gunter MJ, Appleby PN, Key TJ, Travis RC. 2016. Plasma concentrations and intakes of amino acids in male meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans: a cross-sectional analysis in the EPIC-Oxford cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr 70:306–312. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Staats A, Burback PW, Schwieters A, Li D, Sullivan A, Horswill AR, Stoodley P. 2022. Rapid aggregation of Staphylococcus aureus in synovial fluid is influenced by synovial fluid concentration, viscosity, and fluid dynamics, with evidence of polymer bridging. mBio 13:e0023622. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00236-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Izakovicova P, Borens O, Trampuz A. 2019. Periprosthetic joint infection: current concepts and outlook. EFORT Open Rev 4:482–494. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khamis H. 2008. Measures of association: how to choose? J Diagn Med Sonogr 24:155–162. doi: 10.1177/8756479308317006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gilpin AR. 1993. Table for conversion of Kendall’s tau to Spearman’s rho within the context of measures of magnitude of effect for meta-analysis. Educ Psychol Meas 53:87–92. doi: 10.1177/0013164493053001007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pestrak MJ, Gupta TT, Dusane DH, Guzior DV, Staats A, Harro J, Horswill AR, Stoodley P. 2020. Investigation of synovial fluid induced Staphylococcus aureus aggregate development and its impact on surface attachment and biofilm formation. PLoS One 15:e0231791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hajdamowicz NH, Hull RC, Foster SJ, Condliffe AM. 2019. The impact of hypoxia on the host-pathogen interaction between neutrophils and Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Mol Sci 20:5561. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Staats A, Burback PW, Eltobgy M, Parker DM, Amer AO, Wozniak DJ, Wang S-H, Stevenson KB, Urish KL, Stoodley P. 2021. Synovial fluid-induced aggregation occurs across Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates and is mechanistically independent of attached biofilm formation. Microbiol Spectr 9:e0026721. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.00267-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haeberle A, Greenwood-Quaintance K, Zar S, Johnson S, Patel R, Willett JLE. 2024. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of Enterococcus faecalis isolates from periprosthetic joint infections. bioRxiv:2024.02.06.579140. doi: 10.1101/2024.02.06.579140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35. Van den Driessche F, Rigole P, Brackman G, Coenye T. 2014. Optimization of resazurin-based viability staining for quantification of microbial biofilms. J Microbiol Methods 98:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Bleeckere A, Van den Bossche S, De Sutter P-J, Beirens T, Crabbé A, Coenye T. 2023. High throughput determination of the biofilm prevention concentration for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms using a synthetic cystic fibrosis sputum medium. Biofilm 5:100106. doi: 10.1016/j.bioflm.2023.100106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Isguven S, Fitzgerald K, Delaney LJ, Harwood M, Schaer TP, Hickok NJ. 2022. In vitro investigations of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in physiological fluids suggest that current antibiotic delivery systems may be limited. Eur Cell Mater 43:6–21. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v043a03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stamm J, Weißelberg S, Both A, Failla AV, Nordholt G, Büttner H, Linder S, Aepfelbacher M, Rohde H. 2022. Development of an artificial synovial fluid useful for studying Staphylococcus epidermidis joint infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12:948151. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.948151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gobezie R, Kho A, Krastins B, Sarracino DA, Thornhill TS, Chase M, Millett PJ, Lee DM. 2007. High abundance synovial fluid proteome: distinct profiles in health and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 9:R36. doi: 10.1186/ar2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mateos J, Lourido L, Fernández-Puente P, Calamia V, Fernández-López C, Oreiro N, Ruiz-Romero C, Blanco FJ. 2012. Differential protein profiling of synovial fluid from rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis patients using LC-MALDI TOF/TOF. J Proteomics 75:2869–2878. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Feeney E, Peal BT, Inglis JE, Su J, Nixon AJ, Bonassar LJ, Reesink HL. 2019. Temporal changes in synovial fluid composition and elastoviscous lubrication in the equine carpal fracture model. J Orthop Res 37:1071–1079. doi: 10.1002/jor.24281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Balazs EA, Watson D, Duff IF, Roseman S. 1967. Hyaluronic acid in synovial fluid. I. Molecular parameters of hyaluronic acid in normal and arthritic human fluids. Arthritis & Rheum 10:357–376. doi: 10.1002/art.1780100407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brandt JM, Brière LK, Marr J, MacDonald SJ, Bourne RB, Medley JB. 2010. Biochemical comparisons of osteoarthritic human synovial fluid with calf sera used in knee simulator wear testing. J Biomed Mater Res A 94:961–971. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Coenye T, Spittaels KJ, Achermann Y. 2022. The role of biofilm formation in the pathogenesis and antimicrobial susceptibility of Cutibacterium acnes. Biofilm 4:100063. doi: 10.1016/j.bioflm.2021.100063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rottier W, Seidelman J, Wouthuyzen-Bakker M. 2023. Antimicrobial treatment of patients with a periprosthetic joint infection: basic principles. Arthropl 5:10. doi: 10.1186/s42836-023-00169-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Renz N, Trampuz A, Zimmerli W. 2021. Controversy about the role of rifampin in biofilm infections: is it justified? Antibiotics (Basel) 10:1–9. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10020165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Karlsen ØE, Borgen P, Bragnes B, Figved W, Grøgaard B, Rydinge J, Sandberg L, Snorrason F, Wangen H, Witsøe E, Westberg M. 2020. Rifampin combination therapy in staphylococcal prosthetic joint infections: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Surg Res 15:365. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01877-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Trobos M, Firdaus R, Svensson Malchau K, Tillander J, Arnellos D, Rolfson O, Thomsen P, Lasa I. 2022. Genomics of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis from periprosthetic joint infections and correlation to clinical outcome. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0218121. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02181-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Svensson Malchau K, Tillander J, Zaborowska M, Hoffman M, Lasa I, Thomsen P, Malchau H, Rolfson O, Trobos M. 2021. Biofilm properties in relation to treatment outcome in patients with first-time periprosthetic hip or knee joint infection. J Orthop Translat 30:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2021.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Muñoz-Gallego I, Viedma E, Esteban J, Mancheño-Losa M, García-Cañete J, Blanco-García A, Rico A, García-Perea A, Ruiz Garbajosa P, Escudero-Sánchez R, et al. 2020. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections: insight on the pathogenesis and prognosis of a multicenter prospective cohort. Open Forum Infect Dis 7:ofaa344. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moskowitz SM, Foster JM, Emerson J, Burns JL. 2004. Clinically feasible biofilm susceptibility assay for isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 42:1915–1922. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.1915-1922.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental tables, figure, and full protocol.