ABSTRACT

Problem

Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) affects 5%−10% of all women, negatively impacting their reproductive health and quality of life. Herein, we investigated the molecular effects of RVVC on the vaginal mucosa of otherwise healthy women.

Method of Study

Gene expression analysis was performed on vaginal tissue biopsies from women with RVVC, including those with a current episode of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC, n = 19) and women between infections (culture negative RVVC [CNR], n = 8); women asymptomatically colonized with Candida albicans (asymptomatic [AS], n = 7); and healthy controls (n = 18). Gene expression profiles were compared between groups and correlated with clinical data retrieved from questionnaires and gynecologic examinations.

Results

Of 20 171 genes identified in vaginal biopsies, 6506 were differentially expressed in the RVVC group, compared to healthy controls. Gene expression pathway analysis revealed an association between RVVC and pathways of inflammatory responses, especially genes involved in neutrophil recruitment and activation. Expression of genes involved in inflammation and neutrophil recruitment increased with increasing clinical severity of VVC, whereas expression of some genes involved in epithelial integrity decreased with increasing clinical severity of infection. Gene expression profiles of both the CNR and AS groups were comparable to those of healthy controls.

Conclusions

The clinical severity of RVVC during active infection correlates with increased expression of genes involved in molecular inflammation and neutrophil activation in the vaginal mucosa. The lack of differences between healthy controls and women with RVVC who were between acute infections indicates that the molecular effects observed in the RVVC group are only present during active infection.

Keywords: candida, epithelium, inflammation, transcriptomics, vagina

1. Introduction

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is an inflammatory condition of the vagina caused by infection with yeast, most commonly Candida albicans. VVC affects 70%−75% of women at least once during their lifetime [1, 2, 3]. The main symptoms are vaginal itching and soreness, abnormal vaginal discharge, and pain or discomfort during urination and/or sexual intercourse [2], all of which can have pronounced negative effects on quality of life, reproductive health, and sexual wellbeing. Approximately 5%−10% of women develop recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC), defined as persistent VVC or three or more episodes of VVC per year [1]. In addition to symptoms of acute VVC, patients with RVVC often present with additional diagnoses, such as depression, anxiety, or vulvodynia [4, 5].

Known risk factors for VVC include elevated estrogen levels, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and use of antibiotics. However, the majority of women with RVVC lack any known triggers or risk factors for VVC and are thus diagnosed with idiopathic RVVC [2]. It has been hypothesized that women with idiopathic RVVC may have predisposing genetic alterations related to epithelial cell receptor function and inflammasome regulation, resulting in a hyperreactive inflammatory response that leads to VVC symptoms [6]. In VVC, an increased fungal burden, as well as the release of fungal toxins and proteases, triggers an innate immune response in vaginal epithelial cells through nuclear factor (NF)‐κB and mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways [6]. The subsequent production of proinflammatory cytokines and alarmins induces neutrophil recruitment and activation [7, 8]. The combination of high fungal burden and epithelial invasion, along with an aggressive innate immune response, is believed to result in the clinical symptoms of VVC, differentiating it from asymptomatic (AS) C. albicans colonization [9].

In our previous study, we investigated the transcriptional signatures of clinical VVC in the cervicovaginal mucosa of Kenyan sex workers and found that infection was associated with inflammation and neutrophil activation, but not with severe epithelial disruption [7]. Our present study aimed to further investigate the effects of culture‐verified VVC episodes on the vaginal mucosa of Swedish women with RVVC and to correlate these effects with the clinical severity of infection. Expanding our knowledge of the host molecular defense mechanisms in patients with RVVC is crucial to understanding the etiology of symptoms, as well as inadequate fungal clearance, in this condition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

Women diagnosed with RVVC were recruited via the gynecology clinic at Danderyd's Hospital and primary care clinics in Stockholm, Sweden, as well as through flyers and advertising on social media platforms. Healthy women were also recruited through flyers and advertising on social media. All women were recruited between March 28, 2022 and December 8, 2023. The inclusion criteria for all study participants were age 18−46 years, not pregnant, no serious medical or gynecologic conditions (other than RVVC), and no antibiotics or antifungal agents during the previous 2 weeks.

At the enrollment visit, potential study participants completed a medical and social questionnaire. In the questionnaire, RVVC was defined as ≥3 episodes of self‐reported VVC during the past 12 months. All women also underwent a routine gynecologic examination by a senior gynecologist, which included obtaining urine for pregnancy testing and vaginal swabs for fungal cultures and polymerase chain reaction detection of chlamydia and gonorrhea. Two wet mounts of vaginal discharge (wet smears) were prepared with potassium hydroxide or saline to assess for signs of VVC (e.g., visible hyphae), vaginal dysbiosis (e.g., clue cells, reduced number of lactobacilli), and inflammation (e.g., leukocytosis), according to routine clinical procedures. Bacterial vaginosis was further evaluated using the Whiff test and pH test of vaginal swab samples, according to routine clinical procedures. Based on these evaluations, women diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, or infection with a fungal species other than C. albicans were excluded from the study.

Symptom scores and clinical scores were also assessed at the enrollment visit. Symptom scores (range, 0−5 points) were obtained by asking study participants whether they were currently experiencing vulvovaginal discharge (1 point), itching (1 point), dryness (1 point), burn (1 point), or pain (1 point). Clinical scores (range, 0−5 points) were based on the presence of vulvovaginal redness (1 point), discharge (1 point), dryness (1 point), or fissures (1 point) on gynecologic examination, as well as the presence of visible hyphae in wet mount (1 point). Women with RVVC were divided into two groups: women with a current VVC episode (positive culture for C. albicans and symptom score ≥1) and women with a history of RVVC but negative fungal cultures. Similarly, healthy women were divided into two groups: women with no symptoms and negative fungal cultures and women asymptomatically colonized with C. albicans (fungal culture positive for C. albicans and symptom score of 0).

2.2. Fungal Cultures

Vaginal swabs were transported in liquid amies transport medium, cultured on CHROMagar Candida Plus and incubated at 37°C for 24–48 h. C. albicans typically appears as green colonies. To confirm species identification, MALDI‐TOF was done. Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed using YeastOne Sensititre (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's recommendation. When MIC‐values were classified as “Susceptible, increased exposure” (I) or “Resistant” (R), verification was performed using the EUCAST broth microdilution method [10].

2.3. Collection of Vaginal Biopsies

Following the collection of vaginal swab samples for diagnosing sexually transmitted infections (STIs), bacterial vaginosis, and VVC, vaginal biopsies were obtained. An experienced gynecologist used Schubert biopsy forceps to collect two 3‐mm biopsy specimens from the right vaginal wall, approximately 3 cm from the introitus. The specimens were placed in FluidX tubes (Brooks Life Sciences, Chelmsford, MA, USA) containing 0.8 mL DNA/RNA‐shield (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) [11], snap frozen in ice‐cold ethanol within 1 min, and subsequently stored at −80°C within 10 min.

2.4. Bulk RNA‐Sequencing

After the vaginal specimens preserved in DNA/RNA‐shield were thawed, total RNA was isolated. The RNA was subsequently purified using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and QIAcube Connect (QIAGEN). RNA quantities were determined using a NanoDrop ND‐1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the RNA integrity number (RIN) was assessed using the Agilent 2200 TapeStation System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Samples with RIN <7.0 were excluded from the analysis. TruSeq mRNA‐Seq library prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for mRNA purification and subsequent conversion into cDNA libraries (using reverse transcriptase, random primers, and DNA polymerase I). Barcoded cDNA libraries were pooled and loaded onto reagent cartridges (Illumina) and sequenced in a NextSeq 550 (Illumina).

2.5. Differential Gene Expression, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), and Clinical Score Analysis

Genes differentially expressed between study groups were assessed using a generalized linear model (glm) from the EdgeR package (19910308) [12]. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a false‐discovery rate (FDR)—adjusted p value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. GSEA was performed on all DEGs to predict functional pathways. Upregulated and downregulated genes were analyzed both separately and in combination. The DEGs underwent GSEA against the databases gene ontology (GO) [13, 14], kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) [15, 16], WikiPathways [17], Reactome [18], and the molecular signatures database (MSigDB) [19]. Furthermore, to assess clustering of samples based on gene expression, hierarchical clustering analysis and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) analysis were performed based on all DEGs. Clinical data were compared between UMAP clusters using the Mann–Whitney U‐test for continuous variables, and Fisher's exact test for binary variables.

To assess correlations between gene expression and clinical severity of RVVC, the clinical score was used as a continuous variable, and the glm model was used to identify genes with expression rates following the same trend as the clinical score of the study participants. Genes with an FDR‐adjusted p value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. GSEA was performed on all genes following the clinical score trend against the databases GO, KEGG, WikiPathways, Reactome, and MSigDB, as described above for all DEGs.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

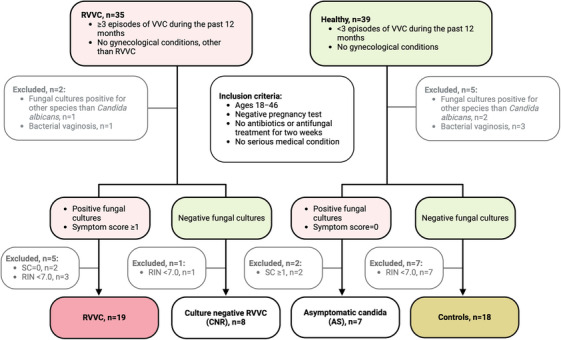

A total of 74 women were recruited for this study and attended the enrollment visit. Eighteen women were subsequently excluded because of vaginal cultures positive for fungal species other than C. albicans (n = 3), bacterial vaginosis (n = 4), or low quality (RIN <7.0) of RNA isolated from biopsy samples (n = 11) (Figure 1). Women with a fungal culture positive for C. albicans, symptom score ≥1, and history of ≥3 episodes of self‐reported VVC during the past 12 months were defined as the RVVC group (n = 19). Women with a negative fungal culture and no history of RVVC were defined as the healthy control group (CTRL group, n = 18). Women initially recruited as healthy controls (i.e., no history of RVVC) who had a current symptom score of 0 but a fungal culture positive for C. albicans were defined as the asymptomatically colonized study group (AS group, n = 7). Women initially recruited for the RVVC group (history of ≥3 episodes of self‐reported VVC during the past 12 months) but whose current fungal culture was negative were defined as the culture‐negative RVVC study group (culture negative RVVC [CNR] group, n = 8) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Inclusion criteria and stratification of study groups. Symptom score (0−5): vulvovaginal discharge = 1p, itching = 1p, dryness = 1p, burn = 1p, pain = 1p, self‐reported. RIN indicates RNA integrity number; RVVC, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis; SC, symptom score; VVC, vulvovaginal candidiasis.

The median age of study participants was 30 years (range, 20−46 years), and the age did not differ significantly between study groups (Table 1). Body mass index based on self‐reported height and weight also did not differ significantly between groups. All women were generally healthy, except for two women in the CTRL group: one was diagnosed with asthma and the other with depression. Regular menstruations were more commonly reported in the AS group as compared to the CTRL group (86% and 33%, respectively, p = 0.03), and use of hormonal intrauterine device (IUD) as method of contraception was less common in the CNR group as compared to the CTRL group (0% and 50%, respectively, p = 0.03). Based on self‐reported symptoms, the median symptom score was four in the RVVC group (range, 2−5 [women with symptom score = 0 were not included in the RVVC group]) and 0 (range, 0−1) in the CTRL group. The median gynecologist‐assessed clinical score was three in the RVVC group (range, 0−5), whereas the clinical score was 0 for all women in the CTRL group (Table S1).

TABLE 1.

Clinical data based on self‐report through questionnaires. Women with positive fungal cultures and ≥3 episodes of VVC per year were defined as an RVVC group, while women with negative fungal cultures and <3 episodes of VVC per years were defined as controls. Women with positive fungal cultures, symptom score = 0, and <3 episodes of VVC per year were defined as an asymptomatic group. Women with negative fungal cultures and ≥3 episodes of VVC per year were defined as a culture negative RVVC group.

| Median or number (range or %) | p value a | Data n/a | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

RVVC n = 19 |

CTRL n = 18 |

AS n = 7 |

CNR n = 8 |

RVVC/Cntrl | AS/Cntrl | CNR/Cntrl | RVVC/CNR | RVVC Ctrls AS CNR | ||||

| Age (years) | 32 (21−46) | 32 (23−42) | 27 (20−37) | 29 (26−45) | 0.75 | 0.32 | 0.82 | >0.9 | 1 | |||

| BMI | 22 (19−27) | 24 (16−36) | 22 (18−23) | 22 (20−24) | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.42 | >0.9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Smoker | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.23 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | 2 | |||

| Healthy | 19 (100) | 16 (89) | 7 (100) | 7 (100) | 0.23 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | 1 | |||

| Married/stable relationship | 15 (79) | 14 (78) | 4 (57) | 5 (83) | >0.9 | 0.36 | >0.9 | >0.9 | 2 | |||

| No. of pregnancies | 2 (0−5) | 1 (0−5) | 0 (0−1) | 1 (0−2) | 0.64 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| No. of children | 1 (0−3) | 1 (0−3) | 0 (0−1) | 0 (0−1) | 0.53 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Regular menstruations | 13 (68) | 6 (33) | 6 (86) | 3 (50) | 0.05 | 0.03* | 0.63 | 0.63 | 2 | |||

| Contraceptive use | ||||||||||||

| Hormonal IUD | 6 (32) | 9 (50) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.03* | 0.15 | 1 | |||

| Birth controll pills | 6 (32) | 3 (17) | 3 (43) | 3 (43) | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.66 | 1 | |||

| No contraceptive | 7 (37) | 5 (28) | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 1 | |||

| History of sexually transmitted infections | ||||||||||||

| Chlamydia | 6 (32) | 4 (22) | 1 (14) | 3 (50) | 0.71 | >0.9 | 0.31 | 0.63 | 2 | |||

| Herpes | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | >0.9 | >0.9 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 2 | |||

| Condyloma | 4 (21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.11 | >0.9 | >0.9 | 0.54 | 2 | |||

| Foul‐smelling vaginal discharge | 5 (26) | 4 (22) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) | >0.9 | 0.30 | 0.62 | >0.9 | 2 | |||

| Cervical dysplasia | 6 (32) | 3 (17) | 1 (14) | 2 (33) | 0.45 | >0.9 | 0.57 | >0.9 | 2 | |||

| RVVC | ||||||||||||

| Duration of RVVC (years) | 5 (0.4−20) | na | na | 5 (4−13) | na | na | na | 0.67 | 1 | 4 | ||

Abbreviations: AS, asymptomatic; BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); CNR, culture negative RVVC; CTRL, controls; IUD, intrauterine device; n/a, not available (excluded from statistical analysis); no, number; RVVC, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis.

A Mann–Whitney U test was applied for continous variables, and Fischer's exact test was applied for binary variables. p < 0.05 was considered statisticaly significant, significant p values are marked with an asterisk.

3.2. RVVC is Associated With Gene Expression Profiles Consistent With Neutrophil Recruitment and Immune Activation

To investigate gene expression associated with RVVC, we used RNA‐sequencing analysis to define the host transcriptomic profile of 52 vaginal tissue samples. A total of 20 171 genes were detected in the dataset. Genes with an FDR‐adjusted p value <0.05 were considered significantly differentially expressed between study groups. The RNA expression profiles were first stratified for the two main study groups (RVVC, n = 19; CTRL, n = 18). The transcriptional analysis revealed 6506 DEGs between the RVVC and CTRL groups. Among these DEGs, 3649 were upregulated (log2 fold change [FC] range, 0.12–9.4) and 2857 were downregulated (log2FC range, −0.12 to −4.8) in the RVVC group, compared to the CTRL group (Tables 2 and S2).

TABLE 2.

Number of differentially expressed genes identified when comparing the study groups, and number of genes following the same trend as the clinical score. Genes were identified using the glm pipeline from the EdgeR package.

| Upregulated genes | Downregulated genes | Non‐significant genes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RVVC (n = 19) versus CTRL (n = 18) | 3649 | 2857 | 13 665 |

| AS (n = 7) versus CTRL (n = 18) | 3 | 0 | 20 168 |

| CNR (n = 8) versus CTRL (n = 18) | 0 | 0 | 20 171 |

| RVVC (n = 19) versus CNR (n = 8) | 947 | 602 | 18 622 |

| Genes following the same trend as the clinical score | 4421 | 4565 | 10 523 |

Genes with an FDR‐adjusted p value <0.05 were considered statistically significant genes.

Abbreviations: AS, asymptomatic; CNR, culture negative RVVC; FDR, false discovery rate; GLM, generalized linear model; RVVC, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis.

The upregulated DEGs in the RVVC group included genes involved in immune activation and neutrophil recruitment, such as genes encoding pathogen recognition receptors (e.g., CLECs, TLRs, NLRs, MCR1), proinflammatory mediators (e.g., IL1B, IL17A, IFNG, NOS2, CSF3), neutrophil‐attracting chemokines (e.g., CXCL1−3, CXCL6, CLXCL8−11, CXCL13, CXCL16, CCL2, CCL7−8), and the neutrophil receptor CXCR1, as well as antimicrobial peptides and enzymes (e.g., LTF, DEFB4A, DEFB4B, LYZ, S100A7A) (Table S2). The downregulated genes in the RVVC group included genes involved in epithelial integrity (CDSN, KPRP, KRT1, and FLG), as well as several genes encoding cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP2A6‐7, CYP2C9, CYP2C18, CYP2C19, CYP2J2, CYP2W1, CYP3A4, CYP4F12, CYP4F22, CYP46A1) (Table S2). The 15 most upregulated and downregulated DEGs according to log2FC values are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

The most differentially expressed genes between the RVVC (n = 19) and CTRL (n = 18) group, according to log2FC. Genes without HGNC ID are presented with ensembl ID.

| HGNC ID | Gene name | Uniprot ID | Log2FC | FDR‐adj. p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 15 most upregulated genes in the RVVC group | ||||

| CXCL1 | C‐X‐C motif chemokine ligand 1 | P09341 | 9.4 | 4.7x‐1012 |

| CXCL8 | C‐X‐C motif chemokine ligand 8 | P10145 | 9.0 | 2.2x‐1010 |

| IL19 | Interleukin 19 | Q9UHD0 | 8.5 | 2.5x‐108 |

| IL22 | Interleukin 22 | Q9GZX6 | 7.9 | 1.3x‐106 |

| LTF | Lactotransferrin | P02788 | 7.7 | 1.4x‐1010 |

| CXCL6 | C‐X‐C motif chemokine ligand 6 | P80162 | 7.6 | 3.7x‐109 |

| NOS2 | Nitric oxide synthase 2 | P35228 | 7.3 | 5.5x‐108 |

| CSF3 | Colony stimulating factor 3 | P09919 | 6.6 | 1.0x‐107 |

| S100A7A | s100 calcium binding protein A7A | Q86SG5 | 6.5 | 7.7x‐107 |

| MMP7 | Matrix metallopeptidase 7 | P09237 | 6.5 | 2.7x‐107 |

| TRIM40 | Tripartite motif containing 40 | Q6P9F5 | 6.3 | 6.1x‐105 |

| CXCL13 | C‐X‐C motif chemokine ligand 13 | O43927 | 6.2 | 1.2x‐105 |

| OSM | Oncostatin M | P13725 | 6.2 | 3.8x‐1010 |

| LILRA5 | Leukocyte immunoglobulin like receptor A5 | A6NI73 | 5.9 | 2.3x‐108 |

| CLEC4D | C‐type lectin domaine family 4 member D | Q8WXI8 | 5.8 | 1.2x‐106 |

| Top 15 most downregulated genes in the RVVC group | ||||

| CDSN | Corneodesmosin | Q15518 | −4.8 | 7.3x‐107 |

| Ensembl ID: ENSG00000263427 | — | −3.2 | 5.3x‐103 | |

| Ensembl ID: ENSG00000258837 | — | −3.1 | 1.7x‐103 | |

| CYP2F2P | Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily F member 2, pseudogene | — | −3.0 | 5.0x‐103 |

| KRT36 | Keratin 36 | O76013 | −2.8 | 9.3x‐105 |

| HTR2C | 5‐Hydroxytryptamine receptor 2C | P28335 | −2.8 | 6.4x‐103 |

| CYP2A6 | Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily A member 6 | P11509 | −2.7 | 5.3x‐103 |

| C5orf46 | Chromosome 5 open reading frame 46 | Q6UWT4 | −2.6 | 1.6x‐103 |

| CHGA | Chromogranin A | P10645 | −2.5 | 9.8x‐103 |

| SERPINA12 | Serpin family A member 12 | Q8IW75 | −2.5 | 3.0x‐103 |

| TMEM72 | Transmembrane 72 | A0PK05 | −2.4 | 5.5x‐104 |

| GDNF‐AS1 | GDNF antisense RNA 1 | — | −2.4 | 8.8x‐105 |

| ELFN2 | Extracellular leucine rich repeat and fibronectin type III domain containing 2 | Q5R3F8 | −2.4 | 6.7x‐107 |

| CYP2A7 | Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily A member 7 | P20853 | −2.3 | 2.5x‐102 |

| SULT1C3 | Sulfotransferase family 1C member 3 | Q6IMI6 | −2.3 | 5.2x‐103 |

Abbreviations: CTRL, controls; FDR adj., false discovery rate adjusted; HGNC, HUGO gene nomenclature committee; log2FC, log2(fold change); RVVC, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis.

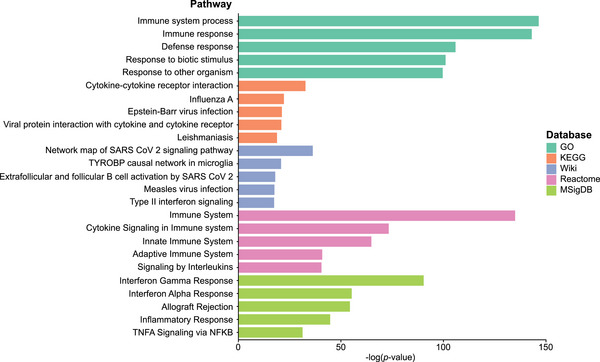

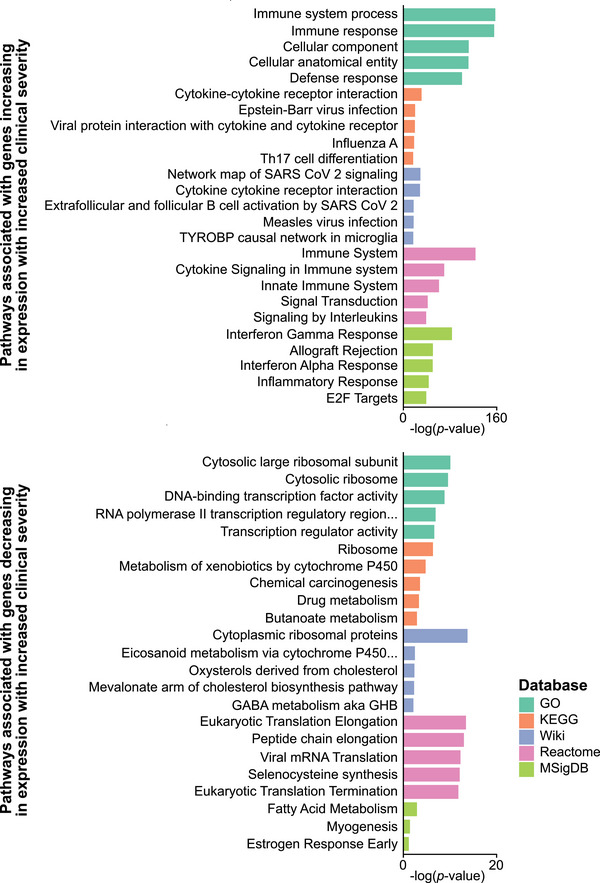

3.3. RVVC is Associated With Functional Pathways of Immune Activation and Response to Infection

GSEA was performed on all 6506 DEGs identified between the RVVC and CTRL groups, using the GO, KEGG, WikiPathways, Reactome, and MSigDB databases to identify functional pathways associated with the gene expression profile of the RVVC group. Upregulated and downregulated genes were analyzed both separately and in combination (Table S3). The most significant pathways associated with upregulated genes in the RVVC group (compared to the CTRL group) were immune response pathways, inflammatory pathways, and pathways involved in responses to infectious diseases. The downregulated genes were mainly associated with metabolic pathways. The five most significant pathways according to p values from each database were all associated with upregulated genes and are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Gene set enrichment analysis of all differentially expressed genes. Top five pathways most significantly associated with the 3649 upregulated genes (FDR‐adjusted p value <0.05, log2FC >0) between the RVVC (n = 19) and CTRL (n = 18) group when compared against the databases GO, KEGG, WikiPathways, Reactome, and MsigDB. CTRL indicates controls; GO, gene ontology; KEGG, Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes; MSigDB, the molecular signatures database; RVVC, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis; Wiki, WikiPathways.

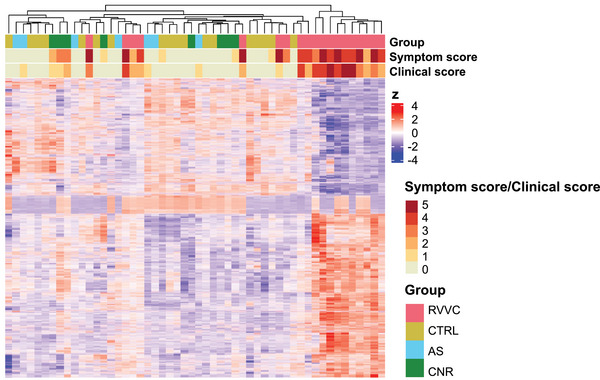

3.4. Clustering Analysis Based on DEGs

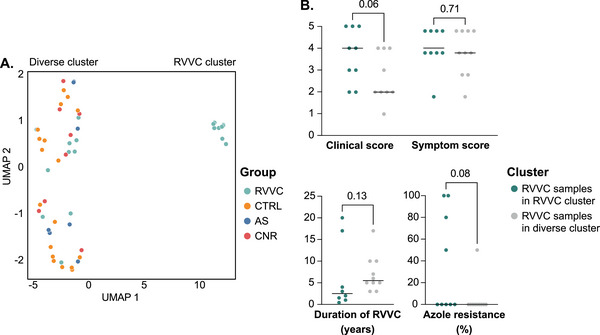

Hierarchical clustering analysis based on differential gene expression between the RVVC and CTRL groups revealed one group containing samples from women in the RVVC group with varying symptom and clinical scores and one group consisting of samples from all four study groups (Figure 3). UMAP analysis was performed based on all DEGs between the RVVC and CTRL groups to further assess clustering of samples. This analysis revealed two distinct clusters: one cluster consisted of nine samples from the RVVC group, and the other cluster contained the remaining 10 RVVC samples interspersed with all samples from the CTRL, AS, and CNR groups (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 3.

Hierarchial clustering of differentially expressed genes. Heatmap of all 6506 DEGs (FDR‐adjusted p value <0.05) between the RVVC (n = 19) and CTRL (n = 18) group. Each study participant is represented by a vertical column and each gene is represented by a horizontal row. The expression of each gene is standardized (z) to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Red: above average expression, blue: below average expression. AS indicates asymptomatic; CNR, culture negative RVVC; CTRL, controls; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; FDR, false‐discovery rate; RVVC, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis.

FIGURE 4.

UMAP of all samples based on gene expression. UMAP based on all 6506 DEGs (FDR‐adjusted p value <0.05) between the RVVC (n = 19) and CTRL (n = 18) group (A). Statistical comparison of clinical score (assessed by gynecologist), symptom score (self‐reported), duration of RVVC (self‐reported) and azole resitance (assessed according to clinical routine, and measured as the percentage of tested azoles the yeast proved resistant against) between RVVC samples in the RVVC cluster and RVVC samples in the diverse cluster (B). AS indicates asymptomatic; CNR, culture negative RVVC; CTRL, controls; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; FDR, false‐discovery rate; RVVC, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis; UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

To investigate differences between RVVC samples in the RVVC cluster and RVVC samples clustering with the CTRL group, statistical analyses were performed to compare clinical features between these two groups based on data retrieved from the enrollment questionnaires and gynecologic examinations (Table S4). These analyses revealed that the samples in the RVVC cluster were obtained from women with higher clinical scores than the women whose samples clustered with the CTRL group, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). Symptom scores were similar between RVVC samples in the two clusters. Azole resistance was trending toward higher in the unique RVVC cluster (p = 0.08), while duration of RVVC was similar between clusters (Figure 4B, Table S4).

3.5. Dynamic Expression of Inflammatory Genes Correlates With Clinical Severity of VVC

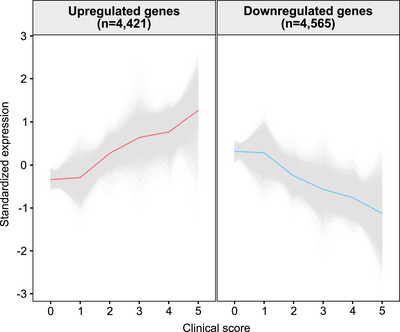

As a trend toward higher clinical scores was observed in the RVVC cluster, the clinical score of the study participants was used as a continuous variable to identify genes with expression rates following the same trend as the clinical score. In this way, the relationship between gene expression and clinical severity of RVVC could be assessed. The analysis revealed 4421 upregulated genes with expression rates positively correlating with clinical score (log2FC range, 0.02–2.29), and 4565 downregulated genes negatively correlating with clinical score (log2FC range, −0.02 to −1.62) (Tables 2 and S5, Figure 5). The upregulated genes included genes encoding neutrophil‐attracting chemokines (CXCL1‐3, 6, 8‐11, 13, and 16), the neutrophil receptor CXCR1, proinflammatory mediators (IL1B, IL17A, IFNG, NOS2, and CSF3), and antimicrobial peptides (LTF, LYZ, and S100A7). The downregulated genes included epithelial barrier marker genes (CDSN, KPRP, KRT1, and FLG) (Table S5). GSEA of the genes following the clinical score trend revealed the upregulated genes to be associated with pathways of immune system processes, while the downregulated genes were associated with mainly metabolic and structural pathways (Figure 6, Table S6). Collectively, these results highlight the dynamic nature of proinflammatory gene expression, which correlated with the degree of inflammation visualized clinically.

FIGURE 5.

Genes significantly associated with clinical severity of RVVC. The clinical score was used as a continuous variable to identify up‐ and downregulated genes, respectively, with expression rates following the same trend as the clinical score. Genes with an FDR‐adjusted p value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All genes are in grey, and the average expression is shown in red/blue. FDR indicates false‐discovery rate; RVVC, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis.

FIGURE 6.

Gene set enrichment analysis of genes associated with clinical severity of RVVC. Top five pathways most significantly associated with the genes following the clinical score trend, when compared against the databases GO, KEGG, WikiPathways, Reactome, and MsigDB. GO indicates gene ontology; KEGG, kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes; MSigDB, the molecular signatures database; Wiki, WikiPathways.

3.6. The Vaginal Transcriptome in Women With Asymptomatic Colonization is Comparable to That of Healthy Controls

To investigate the effects of asymptomatic colonization with C. albicans on the vaginal mucosa, the group of women asymptomatically colonized with C. albicans (AS group, n = 7) was compared to the CTRL group (n = 18). Transcriptional analysis revealed only three DEGs (MTCO3P12, IGHV3‐74, MTCO1P12) between the AS and CTRL groups, all of which were upregulated in the AS group (log2FC range, 1.7–4.8) (Tables 2 and S2). In the hierarchical clustering and UMAP analyses, the AS group clustered with the CTRL group (Figures 3 and 4A).

3.7. The Vaginal Transcriptome Between VVC Episodes is Comparable to That of Healthy Controls

To investigate the state of the vaginal mucosa between episodes of infection in women with RVVC, the group of women with a history consistent with RVVC but whose current fungal culture was negative (CNR, n = 8) was compared to the CTRL group. Transcriptional analysis revealed no DEGs between the CNR and CTRL groups (Tables 2 and S2), and in the hierarchical clustering and UMAP analyses, the CNR group clustered with the CTRL group (Figures 3 and 4A). When comparing the RVVC group (n = 19) to the CNR group, analysis revealed 1549 DEGs between the groups. Among these DEGs, 947 were upregulated (log2 FC range, 0.2–7.2) and 602 were downregulated (log2FC range, −0.2 to −4.2) in the RVVC group, compared to the CNR group. Out of these 1549 genes, 1417 genes were also found among the DEGs between the RVVC and CTRL groups (Tables 2 and S2).

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of C. albicans cultur—positive RVVC on the vaginal mucosa of otherwise healthy women. Analysis of vaginal tissue biopsies from women currently experiencing an episode of RVVC showed upregulation of genes involved in neutrophil recruitment and immune activation, as assessed through transcriptomic profiling.

Among the upregulated genes associated with RVVC, we found several genes encoding C‐type lectin receptors (CLRs), the most predominant fungal‐sensing pathogen recognition receptors in humans [20]. The most upregulated CLR gene was CLEC4D, which encodes C‐type lectin/dectin‐3, a receptor that recognizes a‐mannans on the surface of C. albicans hyphae [21]. CLR binding stimulates an inflammatory response, including activation of the NF‐kB pathway and formation of the NOD‐like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, leading to the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [20]. In VVC, the NLRP3 inflammasome is important for neutrophil recruitment and cytokine production [22, 23, 24]. In the current study, we observed upregulation of the genes for several NLRs, including the NLRP3 gene. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in VVC is inhibited by the interleukin (IL)‐22/NLRC4/IL‐1 receptor antagonist (IL‐1Ra) axis, and reduced levels of IL‐1Ra and IL‐22 have been observed in vaginal fluid from women with RVVC [24]. Interestingly, we found upregulation of both IL22 and NLRC4 in vaginal tissue samples from women with RVVC but no difference in IL1RN expression (the gene encoding IL‐1Ra) between women with RVVC and healthy controls. These discrepancies may reflect differences between gene expression in tissues and cytokine secretion in vaginal fluids. Activation of inflammasomes leads to proteolytic cleavage of IL‐1b and gasdermin D [25], the genes for which (IL1B and GSDMD) were both upregulated in our RVVC group. Subsequently, IL‐1b, together with other proinflammatory mediators (IL‐17, interferon‐gamma, and nitric oxide synthase 2), may induce the secretion of antimicrobial peptides, such as lactoferrin and S100‐A7A [26]. The genes for all of these proinflammatory mediators and peptides were upregulated in the RVVC group. The protective role of IL‐17 in oral candida infections is well established [27, 28], while the role of IL‐17 in VVC remains more controversial. In mice models, IL‐17 has been reported to play a protective role in RVVC through neutrophil regulation in some studies [29, 30], while others have shown no effect of IL‐17 on fungal burden or vaginal neutrophil infiltration [31, 32]. In our study, we found IL17A (the gene encoding IL‐17) to be among the most upregulated genes in women suffering from RVVC as compared to controls, indicating that IL‐17 plays an important role in human VVC.

Several genes encoding neutrophil‐attracting chemokines in the CXC‐ligand family were upregulated in the RVVC group. Among these was the gene encoding C‐X‐C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8), which is the most potent human neutrophil‐attracting chemokine. It is produced by various cells in response to infectious or inflammatory stimuli [26, 33]. Additionally, we observed upregulation of C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), CCL7, and CCL8. The proteins encoded by these genes are all weak neutrophil attractants by themselves but have been shown in vitro to synergize with CXCL8 to effectively stimulate neutrophils [34]. CXC‐ligands activate neutrophils through the CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors, leading to chemotaxis, degranulation, and autocrine CXC‐ligand secretion [33, 35]. The upregulated genes in our RVVC group included CXCR1, as well as genes encoding antimicrobial peptides within neutrophil granules, such as lactoferrin (LTF gene), human β‐defensin‐4 (DEFB4 gene), and lysozyme (LYZ gene), all of which have antifungal activity against C. albicans [36, 37, 38, 39]. Furthermore, one of the most upregulated genes in our study participants with RVVC was CSF3, which encodes colony‐stimulating factor 3, a cytokine essential for neutrophil production and function [40]. Interestingly, it has previously been reported that neutrophils from women with RVVC have reduced fungicidal activity and proliferative capacity, compared to healthy controls [41], which may explain why activation of a neutrophil‐driven immune response does not lead to fungal clearance in patients with RVVC. The mechanism of neutrophil dysfunction has, in mice, been shown to be due to inhibiting factors present in the vaginal microenvironment and has further been linked to increased vaginal tissue damage [42]. Upregulation of genes involved in inflammatory responses and immune signaling was broadly reflected in the pathways found in the GSEA. The most significant pathways found in all five databases were related to immune system processes.

Cluster analysis of vaginal mucosal samples based on gene expression revealed that approximately half of samples from women in the RVVC group clustered separately from the other samples (including samples from the healthy controls and the remaining RVVC group women). When comparing clinical data between these two clusters, we found that, in addition to the trend of higher clinical scores in the unique RVVC cluster, the incidence of azole resistance was trending toward higher in this RVVC cluster. Higher azole resistance could be due to prolonged or inefficient use of antifungal agents; however, the duration of RVVC (i.e., self‐reported years since the onset of fungal infections) did not differ between cluster groups. Alternatively, these women may have been infected with resistant strains of C. albicans. In a recent study by Gerges et al. (2023), azole resistance was associated with increased biofilm formation and proteinase production (both of which are important virulence factors) in clinical C. albicans isolates from women with VVC in Egypt [43]. Conversely, a similar study on C. albicans isolates from women with VVC in India found no significant relationship between azole resistance and biofilm formation or proteinase production, and other studies on vaginal and nonvaginal C. albicans isolates have even shown an association between antifungal resistance and decreased virulence [44, 45, 46]. In the current study, azole resistance was measured as the number of azoles the yeast was resistant to during standard clinical resistance determination, and more comprehensive evaluation of azole resistance should be conducted in future studies to fully understand its role in RVVC.

When assessing gene expression in relation to clinical severity of RVVC, we found that expression of several genes increased as RVVC severity increased, including CXCL1−3, 6, 8, 13, and 16, as well as CXCR1 and genes encoding several proinflammatory mediators and antimicrobial peptides. These results suggest that recruitment and activation of neutrophils is a dynamic process, and that the severity of inflammation observed clinically in RVVC correlates with levels of proinflammatory gene expression. Furthermore, expression of CDSN, KPRP, KRT1, and FLG decreased with increasing clinical severity. These genes encode proteins demonstrated to have important roles in maintaining epithelial integrity at other mucosal sites [47, 48, 49, 50, 51], suggesting that the clinical severity of RVVC may correlate with a less robust epithelial barrier. Decreased epithelial integrity caused by genital inflammation is associated with an increased risk of acquiring STIs, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in endemic regions [52]. The neutrophil‐driven inflammation associated with bacterial vaginosis is minimally visible to clinicians (unlike that of RVVC) but has been linked to downregulation of epithelial junction proteins and an increased risk of acquiring HIV [53, 54, 55]. Epithelial disruption in RVVC may be further mediated by fungal release of proteolytic enzymes and toxins [56, 57, 58, 59], as well as through epithelial penetration of C. albicans hyphae [9, 60–62]. These observations highlight the importance of ensuring proper RVVC treatment and adequate fungal clearance in women at risk of acquiring STIs.

We also assessed vaginal tissue biopsies from women with RVVC who were not currently experiencing an episode of VVC (i.e., the CNR group). Transcriptomic profiling revealed that the vaginal mucosa of these women was comparable to that of healthy controls. Moreover, over 90% of the DEGs identified between the CNR and RVVC group were also found among the DEGs between the RVVC group and healthy controls. This suggests that the mucosa may recover between infections and that the molecular effects observed in our RVVC group are only present during active VVC episodes. The lack of difference between the CNR and control groups in this study indicates the need to look beyond gene expression to identify possible predisposing factors for idiopathic RVVC.

C. albicans is an opportunistic pathogen, and it is estimated that 10%−20% of women are asymptomatically colonized with the organism in the cervicovaginal mucosa [1]. Current knowledge is limited as to why C. albicans might asymptomatically colonize some women and cause symptomatic infection in others. Some studies suggest that the difference in symptomatology is primarily dependent on inherent fungal abilities, such as filamentation, immune evasion, or biofilm formation [62, 63]. Other research suggests that susceptibility to VVC depends more on host factors, such as a dysregulated immune response, impaired epithelial barrier function, or an imbalanced vaginal microbiome [8, 64–66]. Interestingly, we found that gene expression in the vaginal mucosa was similar between women asymptomatically colonized with C. albicans and healthy controls, whereas approximately one‐third of all detected genes were differentially expressed between women with symptomatic VVC and controls. Although these findings do not explain why C. albicans causes asymptomatic colonization in some women and symptomatic infection in others, we speculate that the local inflammatory response contributes to the appearance of symptoms.

This study has a number of strengths. For example, fungal cultures were used to confirm the presence of current VVC and to classify the study participants into four distinct groups (RVVC, CNR, AS, and CTRL). We also collected important clinical information (including clearly defined symptom scores and clinical scores) for each study participant from whom vaginal tissue samples were obtained to evaluate correlations between clinical data and gene expression profiles. This study also has some limitations. The temporal dynamics of changes in gene expression between active episodes could not be proven, as this was a cross‐sectional study. Moreover, the AS and CNR groups were considerably smaller than the RVVC and control groups. Further research is warranted to explore factors associated with susceptibility to RVVC, as well as differences between VVC and AS colonization. Another limitation was the exclusion of women with bacterial vaginosis. As bacterial vaginosis has been linked to both an increased risk of acquiring RVVC and an increased rate of AS vaginal colonization with C. albicans [67, 68, 69], it would be interesting to examine the role of this condition as a confounding factor in the future. Hormonal factors, including regular menstruations and choice of hormonal contraceptive, also differed significantly between some of the study groups. This can potentially influence gene expression patterns, however, the small sample size of the AS and CNR groups as well as the fact that this data was based on self‐report through questionnaires which is less reliable than hormone measurements make it hard to draw any conclusions.

Overall, our results provide important insights into the transcriptional effects of RVVC on the vaginal mucosa, as well as the relationship between clinical severity and molecular inflammation in this condition. We found that the clinical severity of RVVC correlated with upregulation of genes involved in molecular inflammation and neutrophil activation. Furthermore, the vaginal mucosal transcriptome of women with RVVC who were between VVC episodes was similar to that of healthy controls, indicating that the molecular findings observed in women with RVVC are only present during active infection.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was approved by The Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2022‐03126‐01). Each participant provided written informed consent prior to any study‐related procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

We thank the core facility at NEO, Bioinformatics and Expression Analysis, which is supported by the board of research at the Karolinska Institutet and the research committee at the Karolinska University Hospital. Funding was provided by the Swedish Research Council (VR‐MH 2022‐01001 to K.B.).

Funding: This study was supported by The Swedish Research Council (VR‐MH2022‐01001).

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data and clinical characteristics of study participants cannot be held in a public repository because of the sensitive nature of the data. Requests for data access can be made to the Karolinska Institutet Research Data Office (contact via rdo@ki.se), and access will be granted if the request meets the requirements of the institute's data policy. The processed sequencing data files can be accessed in the Gene Expression Omnibus public repository, accession ID GSE278036.

References

- 1. Gonçalves B., Ferreira C., Alves C. T., Henriques M., Azeredo J., and Silva S., “Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Epidemiology, Microbiology and Risk Factors,” Critical Reviews in Microbiology 42, no. 6 (2016): 905–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yano J., Sobel J. D., Nyirjesy P., et al., “Current Patient Perspectives of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Incidence, Symptoms, Management and Post‐Treatment Outcomes,” BMC Womens Health 19, no. 1 (2019): 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sobel J. D., “Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 214 (2016): 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aballéa S., Guelfucci F., Wagner J., et al., “Subjective Health Status and Health‐Related Quality of Life Among Women With Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidosis (RVVC) in Europe and the USA,” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes [Electronic Resource] 11, no. 1 (2013): 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas‐White K., Navarro P., Wever F., King L., Dillard L. R., and Krapf J., “Psychosocial Impact of Recurrent Urogenital Infections: A Review,” Women's Health 19 (2023): 17455057231216537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moyes D. L., Murciano C., Runglall M., Islam A., Thavaraj S., and Naglik J. R., “ Candida albicans Yeast and Hyphae are Discriminated by MAPK Signaling in Vaginal Epithelial Cells,” PLoS ONE 6, no. 11 (2011): e26580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hasselrot T., Boger M. F., Kaldhusdal V., et al., “Vaginal Candida Infection is Associated With Host Molecular Signatures of Neutrophil Activation in the Adjacent Ectocervical Mucosa in Kenyan Sex Workers,” American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 91, no. 2 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fidel P. L., Barousse M., Espinosa T., et al., “An Intravaginal Live Candida Challenge in Humans Leads to New Hypotheses for the Immunopathogenesis of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis,” Infection and Immunity 72, no. 5 (2004): 2939–2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobsen I. D., “The Role of Host and Fungal Factors in the Commensal‐to‐Pathogen Transition of Candida albicans ,” Current Clinical Microbiology Reports 10, no. 2 (2023): 55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rodriguez‐Tudela J. L., Arendrup M. C., Barchiesi F., et al., “EUCAST Definitive Document EDef 7.1: Method for the Determination of Broth Dilution MICs of Antifungal Agents for Fermentative Yeasts,” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 14, no. 4 (2008): 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hugerth L. W., Pereira M., Zha Y., et al., “Assessment of in Vitro and in Silico Protocols for Sequence‐Based Characterization of the Human Vaginal Microbiome,” mSphere 5, no. 6 (2020): e00448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J., and Smyth G. K., “edgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data,” Bioinformatics 26, no. 1 (2009): 139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ashburner M., Ball C. A., Blake J. A., et al., “Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology the Gene Ontology Consortium,” Nature Genetics 25, no. 1 (2000): 25–29, http://www.flybase.bio.indiana.edu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carbon S., Douglass E., Good B. M., et al., “The Gene Ontology Resource: Enriching a Gold Mine,” Nucleic Acids Research 49, no. D1 (2021): D325–D334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kanehisa M., Furumichi M., Sato Y., Ishiguro‐Watanabe M., and Tanabe M., “KEGG: Integrating Viruses and Cellular Organisms,” Nucleic Acids Research 49, no. D1 (2021): D545–D551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanehisa M. and Goto S., “KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes,” Nucleic Acids Research 28 (2000), http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Agrawal A., Balcı H., Hanspers K., et al., “WikiPathways 2024: Next Generation Pathway Database,” Nucleic Acids Research 52, no. D1 (2024): D679–D689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Milacic M., Beavers D., Conley P., et al., “The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase 2024,” Nucleic Acids Research 52, no. D1 (2024): D672–D678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liberzon A., Birger C., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Ghandi M., Mesirov J. P., and Tamayo P., “The Molecular Signatures Database Hallmark Gene Set Collection,” Cell Systems 1, no. 6 (2015): 417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nikolakopoulou C., Willment J. A., and Brown G. D., “C‐Type Lectin Receptors in Antifungal Immunity,” Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1204 (2020): 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhu L. L., Zhao X. Q., Jiang C., et al., “C‐Type Lectin Receptors Dectin‐3 and Dectin‐2 Form a Heterodimeric Pattern‐Recognition Receptor for Host Defense Against Fungal Infection,” Immunity 39, no. 2 (2013): 324–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bruno V. M., Shetty A. C., Yano J., Fidel P. L., Noverr M. C., and Peters B. M., “Transcriptomic Analysis of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Identifies a Role for the NLRP3 Inflammasome,” MBio 6, no. 2 (2015): e00182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roselletti E., Perito S., Gabrielli E., et al., “NLRP3 Inflammasome Is a Key Player in Human Vulvovaginal Disease Caused by Candida albicans ,” Scientific Reports 7, no. 1 (2017): 17877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Borghi M., De Luca A., Puccetti M., et al., “Pathogenic NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity During Candida Infection Is Negatively Regulated by IL‐22 via Activation of NLRC4 and IL‐1Ra,” Cell Host & Microbe 18, no. 2 (2015): 198–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Broz P. and Dixit V. M., “Inflammasomes: Mechanism of Assembly, Regulation and Signalling,” Nature Reviews Immunology 16, no. 7 (2016): 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cambier S., Gouwy M., and Proost P., “The Chemokines CXCL8 and CXCL12: Molecular and Functional Properties, Role in Disease and Efforts Towards Pharmacological Intervention,” Cellular & Molecular Immunology 20, no. 3 (2023): 217–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Conti H. R. and Gaffen S. L., “IL‐17‐Mediated Immunity to the Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans ,” Journal of Immunology 195, no. 3 (2015): 780–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jiang L., Fang M., Tao R., Yong X., and Wu T., “Recombinant Human Interleukin 17A Enhances the Anti‐Candida Effect of Human Oral Mucosal Epithelial Cells by Inhibiting Candida albicans Growth and Inducing Antimicrobial Peptides Secretion,” Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 49, no. 4 (2020): 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shao M., Hou M., Li S., and Qi W., “The Mechanism of IL‐17 Regulating Neutrophils Participating in Host Immunity of RVVC Mice,” Reproductive Sciences 30, no. 12 (2023): 3610–3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pietrella D., Rachini A., Pines M., et al., “Th17 Cells and IL‐17 in Protective Immunity to Vaginal Candidiasis,” PLoS ONE 6, no. 7 (2011): e22770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yano J., Kolls J. K., Happel K. I., Wormley F., Wozniak K. L., and Fidel P. L., “The Acute Neutrophil Response Mediated by S100 Alarmins During Vaginal Candida Infections is Independent of the Th17‐Pathway,” PLoS ONE 7, no. 9 (2012): e46311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peters B. M., Coleman B. M., Willems H. M. E., et al., “The Interleukin (IL) 17R/IL‐22R Signaling Axis is Dispensable for Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Regardless of Estrogen Status,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 221, no. 9 (2020): 1554–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rajarathnam K., Schnoor M., Richardson R. M., and Rajagopal S., “How Do Chemokines Navigate Neutrophils to the Target Site: Dissecting the Structural Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways,” Cell Signalling 54 (2019): 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gouwy M., Struyf S., Catusse J., Proost P., and Van Damme J., “Synergy Between Proinflammatory Ligands of G Protein‐Coupled Receptors in Neutrophil Activation and Migration,” Journal of Leukocyte Biology 76, no. 1 (2004): 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu Y., Wang R. R., Miao N. J., et al., “PD‐L1 Negatively Regulates Antifungal Immunity by Inhibiting Neutrophil Release From Bone Marrow,” Nature Communications 13, no. 1 (2022): 6857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Järvå M., Phan T. K., Lay F. T., Caria S., Kvansakul M., and Hulett M. D., “Human β‐Defensin 2 Kills Candida albicans Through Phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐Bisphosphate‐Mediated Membrane Permeabilization,” Science Advances 4, no. 7 (2018): eaat0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tobgi R. S., Samaranayake L. P., and MacFarlane T. W., “In Vitro Susceptibility of Candida Species to Lysozyme,” Oral Microbiology and Immunology 3, no. 1 (1988): 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Velliyagounder K., Rozario S. D., and Fine D. H., “The Effects of Human Lactoferrin in Experimentally Induced Systemic Candidiasis,” Journal of Medical Microbiology 68, no. 12 (2019): 1802–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pawar S., Markowitz K., and Velliyagounder K., “Effect of Human Lactoferrin on Candida albicans Infection and Host Response Interactions in Experimental Oral Candidiasis in Mice,” Archives of Oral Biology 137 (2022): 105399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khouj E., Marafi D., Aljamal B., et al., “Human ‘Knockouts’ of CSF3 Display Severe Congenital Neutropenia,” British Journal of Haematology 203, no. 3 (2023): 477–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Consuegra‐Asprilla J. M., Rodríguez‐Echeverri C., Posada D. H., Gómez B. L., and González Á., “Patients With Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Exhibit a Decrease in Both the Fungicidal Activity of Neutrophils and the Proliferation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells,” Mycoses 67, no. 4 (2024): e13720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yano J., Noverr M. C., and Fidel P. L., “Vaginal Heparan Sulfate Linked to Neutrophil Dysfunction in the Acute Inflammatory Response Associated With Experimental Vulvovaginal Candidiasis,” MBio 8, no. 2 (2017): e00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gerges M. A., Fahmy Y. A., Hosny T., et al., “Biofilm Formation and Aspartyl Proteinase Activity and Their Association With Azole Resistance Among Candida albicans Causing Vulvovaginal Candidiasis, Egypt,” Infection and Drug Resistance 16 (2023): 5283–5293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ben‐Ami R., Garcia‐Effron G., Lewis R. E., et al., “Fitness and Virulence Costs of Candida albicans FKS1 Hot Spot Mutations Associated with Echinocandin Resistance,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 204, no. 4 (2011): 626–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. El‐Houssaini H. H., Elnabawy O. M., Nasser H. A., and Elkhatib W. F., “Correlation Between Antifungal Resistance and Virulence Factors in Candida albicans Recovered From Vaginal Specimens,” Microbial Pathogenesis 128 (2019): 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Graybill J. R., Montalbo E., Kirkpatrick W. R., Luther M. F., Revankar S. G., and Patterson T. F., “Fluconazole Versus Candida albicans: A Complex Relationship,” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 42, no. 11 (1998): 2938–2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dinh M. H., Okocha E. A., Koons A., Veazey R. S., and Hope T. J., “Expression of Structural Proteins in Human Female and Male Genital Epithelia and Implications for Sexually Transmitted Infections,” Biology of Reproduction 86, no. 2 (2012): 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Suga H., Oka T., Sugaya M., et al., “Keratinocyte Proline‐Rich Protein Deficiency in Atopic Dermatitis Leads to Barrier Disruption,” Journal of Investigative Dermatology 139, no. 9 (2019): 1867–1875. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roth W., Kumar V., Beer H. D., et al., “Keratin 1 Maintains Skin Integrity and Participates in an Inflammatory Network in Skin Through Interleukin‐18,” Journal of Cell Science 125, no. Pt 22 (2012): 5269–5279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dong X., Liu Z., Lan D., et al., “Critical Role of Keratin 1 in Maintaining Epithelial Barrier and Correlation of its Down‐Regulation With the Progression of Inflammatory Bowel Disease,” Gene 608 (2017): 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu J., Niu J., Li M., and Miao Y., “Keratin 1 Maintains the Intestinal Barrier in Ulcerative Colitis,” Genes Genomics 43, no. 12 (2021): 1389–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Galvin S. R. and Cohen M. S., “The Role of Sexually Transmitted Diseases in HIV Transmission,” Nature Reviews Microbiology 2, no. 1 (2004): 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Costa‐Fujishima M., Yazdanpanah A., Horne S., et al., “Nonoptimal Bacteria Species Induce Neutrophil‐Driven Inflammation and Barrier Disruption in the Female Genital Tract,” Mucosal Immunology 16, no. 3 (2023): 341–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Atashili J., Poole C., Ndumbe P. M., Adimora A. A., and Smith J. S., “Bacterial Vaginosis and HIV Acquisition: A Meta‐Analysis of Published Studies,” AIDS 22, no. 12 (2008): 1493–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mitchell C. and Marrazzo J., “Bacterial Vaginosis and the Cervicovaginal Immune Response,” American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 71, no. 6 (2014): 555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pericolini E., Gabrielli E., Amacker M., et al., “Secretory Aspartyl Proteinases Cause Vaginitis and Can Mediate Vaginitis Caused by Candida albicans in Mice,” MBio 6, no. 3 (2015): e00724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Richardson J. P., Willems H. M. E., Moyes D. L., et al., “Candidalysin Drives Epithelial Signaling, Neutrophil Recruitment, and Immunopathology at the Vaginal Mucosa,” Infection and Immunity 86, no. 2 (2018): e00645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schaller M., Bein M., Korting H. C., et al., “The Secreted Aspartyl Proteinases Sap1 and Sap2 Cause Tissue Damage in an in Vitro Model of Vaginal Candidiasis Based on Reconstituted Human Vaginal Epithelium,” Infection and Immunity 71, no. 6 (2003): 3227–3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Taylor B. N., Staib P., Binder A., et al., “Profile of Candida albicans Secreted Aspartic Proteinase Elicited During Vaginal Infection,” Infection and Immunity 73, no. 3 (2005): 1828–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sobel J. D., Myers P. G., Kaye D., and Levison M. E., “Adherence of Candida albicans to Human Vaginal and Buccal Epithelial Cells,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 143, no. 1 (1981): 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chow E. W. L., Pang L. M., and Wang Y., “From Jekyll to Hyde: The Yeast–Hyphal Transition of Candida albicans ,” Pathogens 10, no. 7 (2021): 859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Faria D. R., Sakita K. M., Akimoto‐Gunther L. S., Kioshima É. S., Svidzinski T. I. E., and de Bonfim‐Mendonça P. S., “Cell Damage Caused by Vaginal Candida albicans Isolates From Women With Different Symptomatologies,” Journal of Medical Microbiology 66, no. 8 (2017): 1225–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wu X., Zhang S., Li H., et al., “Biofilm Formation of Candida albicans Facilitates Fungal Infiltration and Persister Cell Formation in Vaginal Candidiasis,” Frontiers in Microbiology 11 (2020): 1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Odds F. C., “Genital Candidosis,” Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 7 (1982): 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rane H. S., Hardison S., Botelho C., Bernardo S. M., Wormley F., and Lee S. A., “ Candida albicans VPS4 Contributes Differentially to Epithelial and Mucosal Pathogenesis,” Virulence 5, no. 8 (2014): 810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Höfs S., Mogavero S., and Hube B., “Interaction of Candida albicans With Host Cells: Virulence Factors, Host Defense, Escape Strategies, and the Microbiota,” Journal of Microbiology 54, no. 3 (2016): 149–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pramanick R., Mayadeo N., Warke H., Begum S., Aich P., and Aranha C., “Vaginal Microbiota of Asymptomatic Bacterial Vaginosis and Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Are They Different From Normal Microbiota?,” Microbial Pathogenesis 134 (2019): 103599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sobel J. D. and Vempati Y. S., “Bacterial Vaginosis and Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Pathophysiologic Interrelationship,” Microorganisms 12, no. 1 (2024): 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tortelli B. A., Lewis W. G., Allsworth J. E., et al., “Associations Between the Vaginal Microbiome and Candida Colonization in Women of Reproductive Age,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 222, no. 5 (2020): 471. e1‐e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data and clinical characteristics of study participants cannot be held in a public repository because of the sensitive nature of the data. Requests for data access can be made to the Karolinska Institutet Research Data Office (contact via rdo@ki.se), and access will be granted if the request meets the requirements of the institute's data policy. The processed sequencing data files can be accessed in the Gene Expression Omnibus public repository, accession ID GSE278036.