Abstract

The advancement of safe nanomaterials for use as optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging and stem cell-labeling agents to longitudinally visually track therapeutic derived retinal stem cells to study their migration, survival rate, and efficacy is challenged by instability, intracellular aggregation, low uptake, and cytotoxicity. Here, we describe a series of hybrid lipid-coated gold nanorods (AuNRs) that could solve these issues. These nanomaterials were made via a layer-by-layer assembly approach, and their stability in biological media, mechanism, efficiency of uptake, and toxicity were compared with a commercially available set of AuNRs with a 5 nm mesoporous silica (mSiO2)-polymer coating. These nanomaterials can serve as stem cell labeling and OCT imaging agents because they absorb in the near-infrared (NIR) region away from biological tissues. Although both subtypes of AuNRs were taken up by retinal pigment epithelial, neural progenitor, and baby hamster kidney cells, slightly negatively charged hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs had minimal aggregation in biological media and within the cytoplasm of cells (~3000 AuNRs/cell) as well as minimal impact on cell health. Hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs modified with cell-penetrating peptides had the least toxicological impact, with >92% cell viability. In contrast, the more “sticky” AuNRs with a 5 nm mSiO2-polymer coating showed significant aggregation in biological media and within the cytoplasm with lower-than-expected uptake of AuNRs (~5400 of AuNRs/cell) given their highly positive surface charge (35+ mV). Collectively, we have demonstrated that hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs, which absorb in the NIR-II region away from biological tissues, with tuned surface chemistry can label therapeutic derived stem cells with minimal aggregation and impact on cell health as well as enhance uptake for OCT imaging applications.

Keywords: lipid-coated gold nanorods, optical coherence tomography imaging, stem cells, cell-penetrating peptides, cell uptake studies, toxicity

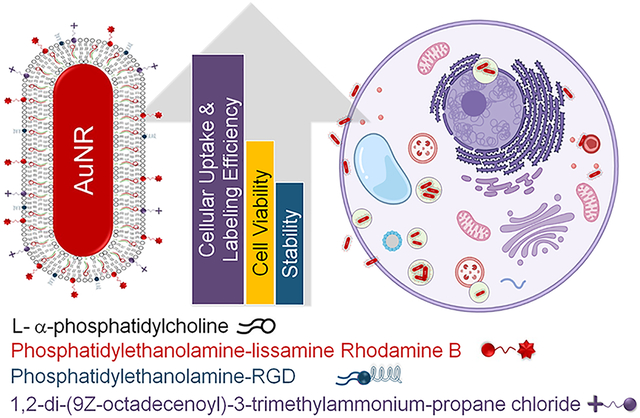

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cell transplantation is a promising therapy for retinal degenerative diseases and is currently being investigated in clinical trials as a neuroprotective strategy to treat geographic atrophy, the advanced form of dry age-related macular degeneration, for which there is no effective treatment,1 as well as diabetic retinopathy2 and glaucoma.3 Cell-based therapy can also be used as a cell replacement strategy for those who have already lost large regions of retinal cells by transplanting photoreceptor cells. However, the slow translation of cell-based therapies from bench to bedside is hindered by the lack of convincing data regarding their safety and efficacy in preclinical models before applying those therapies to humans. Current methods for evaluating cell-based therapies that rely on histological analysis of tissues post-mortem are costly and require many animals to be sacrificed at multiple time points to gain insight into cell migration, integration, and survival after transplantation. The ability to track these cells longitudinally in vivo using conventional imaging techniques is hampered by the inability to identify transplanted cells. Therefore, alternative strategies that allow researchers to label the cells to non-invasively track and monitor the transplanted retinal stem cells are critically needed.

While preclinical imaging modalities such as MRI, CT, optical imaging, and positron emission tomography (PET) exist for visualizing transplanted stem cells in vivo, they lack the resolution to quantify individual cells.4 Optical coherence tomography (OCT), a non-invasive and promising technique based on backscattering of light, provides real-time depth-resolved cross-sectional images of tissues with a spatial resolution of 1 μm and a depth of penetration of several millimeters.5 However, OCT is limited to the micron scale, is unable to provide information on molecular level processes within tissues, and requires exogenous contrast agents such as organic dyes,6 nanoparticles,7 and microscopic particles8 to enhance the scattering signal. While organic dyes such as indocyanine are strong absorbing agents that can be used for OCT imaging, they cast “shadows” on adjacent tissues, making it difficult to locate the labeled cell since the shadow cast could be close by or distal to the location of the absorbing agent. In addition, there are confounding sources of “shadows”, for example, blood vessels, and high concentrations of absorbing agents are required to provide sufficient contrast over background tissue scattering and absorption, which are impractical for labeling cells. In addition, molecular contrast agents exhibit negligible scattering compared to nanoparticles with high scattering that is already established for MRI,9 fluorescence imaging,10 and PAT.11

Several recent studies show that nanomaterials can also be used to label stem cells for in vivo tracking using X-ray, fluorescence, and OCT imaging.12 To date, most nanomaterials developed for OCT imaging are still at the laboratory stage, such as carbon,13 iron oxide,14 and silicon nanoparticles,15 that operate mainly in the NIR-I window (650–950 nm) with small scattering cross sections in the NIR-II window (1000–1700 nm), which limits the enhancement of OCT contrast from biological tissues. Hence, recent efforts are focused on developing contrast agents that operate in the NIR-II window with high reflectivity or scattering efficiency to fill this unmet need. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are of particular interest for OCT because they have strong localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) for interaction with light16 and can be tuned toward the NIR-I and NIR-II windows.17 Studies show that the size and shape of AuNPs, nanospheres,18 nanocages, nanoshells,19 nanoprisms,20 nanorods (AuNRs),21 and nanodisks22 have high scattering efficiencies and OCT contrast when the SPR band is within the central operating wavelength of the OCT.23 In efforts to utilize AuNPs as cell-labeling probes, AuNPs have been modified with epidermal growth factor receptor,24 HER-2,25 and targeting peptides26 to enhance their uptake and targeting of cells. While these studies show that AuNPs are potential cell labeling and OCT contrast agents in vitro,27 nanoparticle-based labels with high scattering efficiencies that can adhere to cells intracellularly or extracellularly to increase the signal intensity and improve resolution in vivo without inducing toxicity and with minimal probe leakage need to be developed.

Previously, we showed that lipid membranes anchored by long-chained hydrophobic thiols are biocompatible coatings that can stabilize various sizes and shapes of AuNPs28–32 and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) prone to surface oxidation.28–34 The hybrid lipid membranes surrounding the nanomaterial core do not undergo membrane rearrangement, unlike traditional liposomes. Furthermore, the hybrid lipid-coated AuNPs and AgNPs show minimal to no toxicity and instability under harsh biological environments, physiological salt concentrations, and low pH found in lysosomal compartments where nanoparticles typically end up in cells, making these ideal platforms for cell-labeling or imaging agents.34,35 Furthermore, the hybrid lipid-coating stabilizes a range of sizes (5–100 nm), shapes (spheres, rods, and triangles), and nanoparticles prone to surface oxidation such as AgNPs to minimize their biological impact in vivo.32,34,36 However, their use as OCT contrast agents and stem cell-labeling probes has not yet been explored. The hybrid lipid coating on the nanoparticles resembles that of natural membrane systems found in lysosomes of cells, which provides the nanoparticles with a “stealth” character. The tunable membrane architecture also makes it easy to modify the nanoparticle surface to increase the cellular uptake and labeling of stem cells to improve the OCT signal intensity. Lastly, the hybrid lipid membranes can be templated onto nanomaterials of any shape, size, or metal-core composition, particularly those with high scattering efficiencies or reflectivity that absorb in the NIR-II region away from biological tissues.

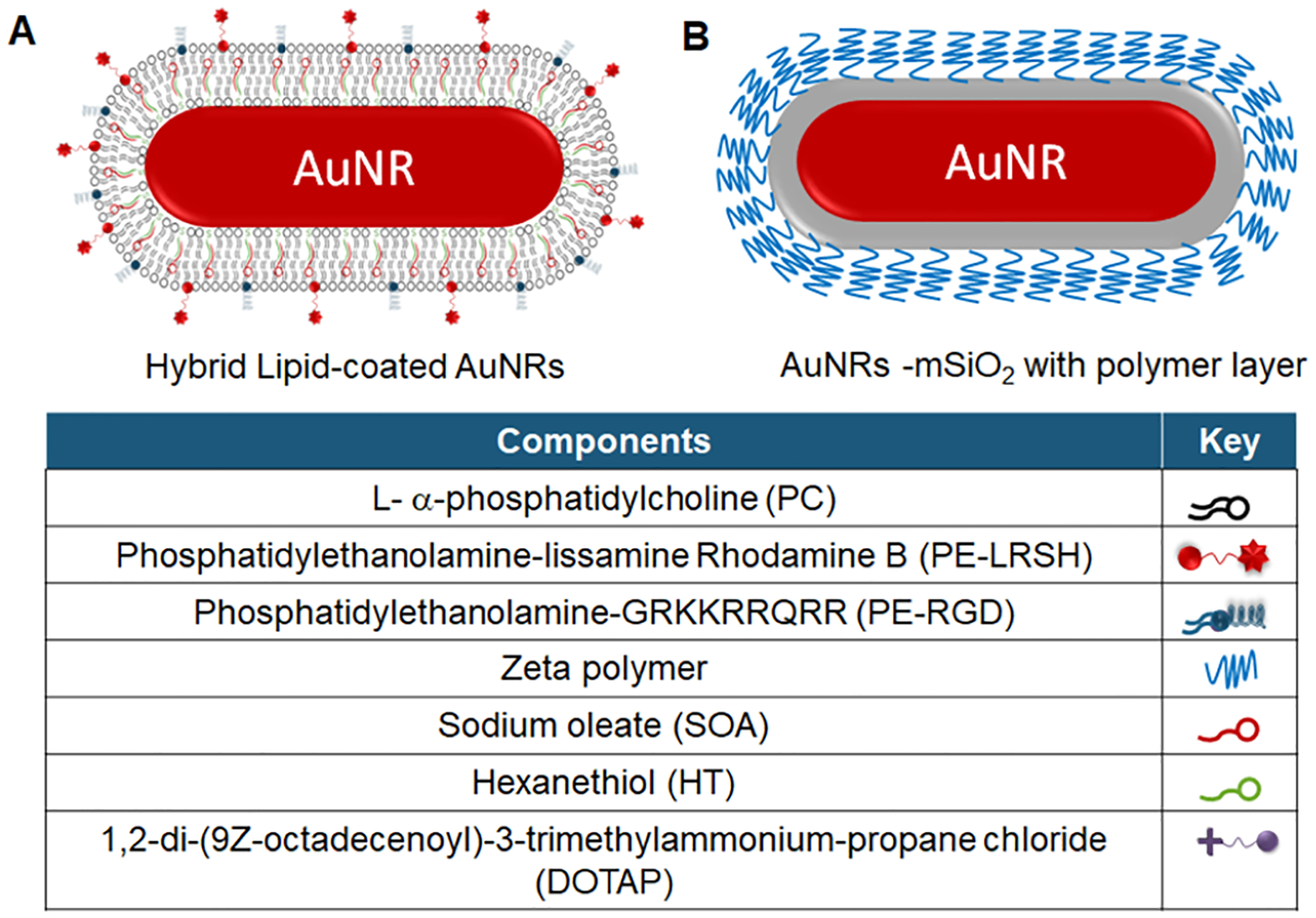

In this report, the hybrid lipid membrane strategy was used to coat AuNRs that absorb in the NIR region to evaluate their potential as cell-labeling agents for tracking by OCT imaging. Since the surface coatings of AuNRs significantly influence cellular uptake, growth, and viability, the membrane architecture was modified with ligands to minimize aggregation and increase the cellular labeling efficiency. The modified coatings are also expected to minimize toxicity to the stem cells and maintain the OCT contrast properties. Thus, we have studied the effect of the surface charge and membrane composition of hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs (Scheme 1A) on nanoparticle–biological interactions, cellular uptake, and cell viability in different cell lines and compared them to commercially available AuNRs with a 5 nm mesoporous silica (mSiO2) shell coated with a proprietary polymer coating (Scheme 1B).

Scheme 1.

Cartoon of Gold Nanorods with a (A) Hybrid Lipid Membrane or a (B) 5 nm mSiO2 and Polymer Layer

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials.

Aqueous solutions of gold citrate-capped nanorods (69 nm × 12 nm) were purchased from NanoComposix.com, and gold mSiO2-capped nanorods with zeta polymer (55 nm × 10 nm or 96 nm × 25 nm) were purchased from Nanopartz.com. Sodium oleate was from TCI America, while 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[4-p-(cysarginylglycylaspartate-maleimidomethyl)-cyclohexane-carboxamide] (PE-RGD), 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (PE-LRSH) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), 95% l-α-phosphatidylcholine (PC), Tween20, and 95% 1-hexanethiol (HT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate and sodium phosphate dibasic heptahydrate were from BDH Chemicals. Potassium cyanide (KCN) and chloroform were from Mallinckrodt. Methanol was from OmniSolv. Nanopure water was from a Milli-Q ultra-pure system. The baby hamster kidney (BHK) (ATCC), neural progenitor cells (NP) (Stem Cell Technologies), and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell lines generated at the Oregon National Primate Center were used for cell culture studies. All other reagents were used as received.

Liposome Preparation.

Thin films composed of a 9:1 ratio of PC/PE-LRSH (45 μL of 21.6 mM PC and 285 μL of 379 μM PE-LRSH in CHCl3), 6:3:1 ratio of PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP or PC/PE-LRSH/CTAB (30 μL of 21.6 mM PC, 285 μL of 379 μM PE-LRSH, 27 μL of 11.9 mM DOTAP or 35 μL of 9.15 mM CTAB in CHCl3), 8:1:1 ratio of PC/RGD/PE-LRSH (40 μL of 21.6 mM PC, 157 μL of 171 μM RGD in methanol, and 285 μL of 379 μM PE-LRSH in CHCl3), or 7:1:1:1 ratio of PC/RGD/PE-LRSH/DOTAP (35 μL of 21.6 mM PC, 157 μL of 171 μM RGD in methanol, 285 μL of 379 μM PE-LRSH, and 9 μL of 11.9 mM DOTAP in CHCl3) were prepared by solvent evaporation under N2 gas. The total number of moles of lipids in each film was 1.08 μmol. Following N2 evaporation, the thin films were dried under vacuum for 12 h before the addition of 2 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 8.0. The film was vigorously shaken to resuspend the lipids, followed by sonication for 90 min, until the cloudy solution turned transparent.

Preparation of Hybrid Lipid-Coated AuNRs.

Sodium oleate (SOA) (2.2 μL of 9.3 mM in H2O) was added to 1 mL of AuNRs with an optical density (OD) of 1.1 in H2O and stirred for 20 min. To the AuNR-SOA solution, 7.4 μL of 0.54 mM of the liposome solution was added and then incubated for 40 min. This was followed by the addition of 0.2 μL of 5 mM hexanethiol (HT) in ethanol that was stirred for 30 min. The resulting hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs were buffered with 10 μL of 1 M sodium phosphate buffer at pH 8.0. To purify the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs, the sample was incubated with 10 μL of 10 mM Tween20 for 20 min at 25 °C to disrupt and destabilize any “nanoparticle-free” liposomes with lipid-dye conjugates. A Thermo Scientific Sorvall ST 40R at 4700 rpm using GE Healthcare ultracentrifuge concentrators with a PES membrane (Vivaspin 20, MWCO = 10 kDa) for 10 rounds at 4 min each was used to remove free lipids, sodium oleate, and thiol. The fluorescence spectra of the filtrates were monitored for PE-LRSH to determine if free-dye lipid-conjugates were still present with the AuNPs. Samples were washed until no fluorescence was observed in the filtrate and were used to indicate if the AuNPs were pure. The final hybrid AuNR-SOA-Liposome-HT was resuspended in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 8.0.

Stability Studies.

To determine if the AuNRs are completely covered by the hybrid lipid membrane, the AuNR-SOA-Liposome-HT was exposed to KCN (20 μL of 307 mM in H2O) at a final concentration of 6 mM for 24 h. The percent change in the λmax and absorbance was monitored with UV–vis to assess the hybrid AuNR membrane stability. For stability studies, AuNRs were incubated at 5 × 1010 AuNRs/mL in either BHK and RPE cell culture media [DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin streptomycin (PS)], water, 1% PBS pH 7.4, or serum-free NP media. Following 24 h at 37 °C, samples were imaged using a bright-field microscope.

Optical Measurements and Fluorescence Imaging.

UV–vis spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-3600 UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer using a 1 cm quartz cuvette. Fluorescence measurements were conducted on samples containing the LRSH fluorophore using a PTI spectrophotometer with FeliX32 software with a quartz cuvette at an excitation of 568 nm and an emission of 580 nm to check for free lipid-dye conjugates after purification. For evaluation of the AuNR uptake into the cells, a Leica TCS SP5 Confocal Microscope with fluorescence and bright-field imaging was used.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

For TEM imaging, 500,000 BHK cells were plated into 24-well culture plates and treated with 5 × 105 AuNRs, #8, #9, #10, and 1 untreated well for 24 h. Cells were washed 3× with 1× 10 mM PBS at pH 7.4, dissociated with 0.25% trypsin, centrifuged, and fixed with 4% PFA. For visualization of nanoparticle uptake in cells, specimens were prepared via microwave fixation and traditional embedding in Eponate 12 (Ted Pella; Redding CA). Fixation, dehydration, and resin infiltration were conducted in a BioWave microwave processor (Ted Pella Inc., Redding CA). Specimens were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde buffered with 0.1 M cacodylate and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide buffered with 0.1 M cacodylate. Samples were then dehydrated in a graded water/acetone series, resin-infiltrated in a graded acetone/resin series, and cured overnight in a 60 °C oven. After ultrathin sectioning to <100 nm, one split of samples was left unstained to minimize contrast due to staining and maximize contrast due to the presence of metal nanoparticles. The second split of ultrathin specimens was stained using standard protocols (Dykstra 1993) for uranyl acetate and lead citrate to allow for typical ultrastructural imaging. Ultrathin section ribbons were floated onto carbon-coated (300 Å) Formvar films on copper grids from Ted Pella. Transmission electron micrographs were acquired on a Tecnai F-20 FEI microscope using a CCD detector at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. Images were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Cell Culture and AuNR Uptake Studies.

BHK and RPE cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS and 1% PS at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, while the NP cell lines were cultured in STEMdiff medium. To evaluate cell uptake, 150,000 cells were seeded into each well of a four-well chamber slide (Lab-Tek). After 24 h of incubation, the culture medium was replaced with a fresh medium containing different AuNR samples with concentrations ranging from 1.6 × 109 to 4.0 × 1012 AuNRs/mL depending on the study herein. After the cells were further incubated for 24 h, they were washed three times with 1× PBS buffer pH 7.4 to remove any AuNRs adsorbed on the cell surface. The cells were subsequently fixed for 5 min using 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) to evaluate AuNR uptake in the varying cell lines using a Leica confocal microscope under fluorescence and bright field.

Cell Viability Studies.

To determine the cytotoxic effects of AuNR uptake, the viability of cells after AuNR uptake was compared. 10,000 BHK cells were seeded into each well on a 96 well-plate and incubated for 24 h in a medium (DMEM with 5% FBS) that is replaced with a fresh medium containing the AuNRs #1, #3, #8, #9, and #10 (Table S1) at three concentrations of each AuNR type (1.0 × 108, 1.0 × 109, and 1.0 × 1010) in each well. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline, and a fresh medium (100 μL) was added to each well. MTS solution (20 μL) was subsequently added to each well, and after 3 h of incubation, absorbance was measured using a SpectraMax M5 multi-mode plate reader at 490 nm. A well with only media and 20 μL of MTS solution was used to determine and subtract out background noise from the readings. The cell viability (%) for each nanoparticle type relative to control was calculated.

Inductively Coupled Mass Spectroscopy.

For quantitative determination of AuNR uptake, BHK and RPE cell lines were cultured in six-well plates (Corning). When the cells reached 80% confluence, the culture medium was replaced with fresh DMEM containing the AuNR samples at a concentration of 5 × 1010 AuNRs/mL at 37 °C. After 24 h of incubation, the samples were collected in a centrifuge tube and washed three times with 1× PBS buffer at pH 7.4 by centrifugation at 200g for 5 min and then frozen until ICP-analysis. The frozen cell pellets were submitted to the Elemental Analysis Core at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) to determine the concentration of Au. Samples were digested directly in the provided centrifuge tubes by adding 100 μL of aqua regia [75 μL of HCl (trace metal grade, Fisher) and 25 μL of HNO3 (trace metal grade, Fisher)] to each cell pellet and briefly heating them to 90 °C for 45 min. Samples were cooled down to an ambient temperature, and digestion was continued at room temperature overnight. The samples were then diluted with 1% HCl (trace metal grade, Fisher) containing 1% cysteine to a total volume of 1 mL. Samples were vortexed to check for complete digestion after dilution. For inductively coupled mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS), measurements were further diluted with 1% cysteine in 1% HCl into 15 mL metal-free polypropylene tubes. ICP-MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 7700x equipped with an ASX 500 autosampler. The system was operated at a radio frequency power of 1550 W, an Ar plasma gas flow rate of 15 L/min, and an Ar carrier gas flow rate of 0.9 L/min. Au was measured in a NoGas mode. Data were quantified using a 10-point [0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 50 ppb (μg/kg)] calibration curve. For each sample, data were acquired in triplicates and averaged. A coefficient of variance was determined from frequent measurements of a sample containing 10 ppb Au. An internal standard (Sc, Ge, and Bi) continuously introduced with the sample was used to correct for detector fluctuations and to monitor plasma stability.

Statistical Analysis.

Data were expressed as means and standard errors. Statistical significance was determined using analysis of variance or t-test. P < 0.5 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Gold Nanorods with Modified Surface Coatings.

In this study, hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs with modified membrane architectures were prepared to study the effects of surface chemistry on stability, cellular uptake, and viability. Following established protocols, the hybrid lipid membranes were anchored to the AuNR core with HT through a layer-by-layer approach (Scheme 1).28–33,35 Briefly, SOA was added to a 1 mL aqueous solution of minimally citrate-capped AuNR [1.0 optical density (O.D.)] for 20 min. The citrate-capped AuNRs (1.8 × 1011 AuNRs/mL) had an average length of 69.7 ± 7.3 nm, a width of 12.1 ± 0.8 nm, and an overall zeta potential of −38.5 mV. The AuNR-SOA solution was incubated with preformed liposomes for 40 min before the addition of HT. The AuNR-SOA-lipid-HT solution was then incubated for a minimum of 30 min to ensure that the membrane was tightly packed and completely covered the AuNR surface. A minimal amount of lipids is used to cover the AuNR surface, thereby reducing the “nanoparticle-free” liposomes in the solution and the purification time. The number of lipids needed to completely coat each AuNR was determined from the number of nanoparticles and the dimensions of the AuNR (see Supporting Information). A variety of liposome formulations with fluorescent dyes, cationic or anionic ligands, and cell-penetrating peptides are used for modifying the membrane architecture surrounding the AuNRs. A fluorophore-labeled lipid, PE-LRSH, is incorporated for visual confirmation of cellular uptake by confocal fluorescence microscopy, while CTAB and DOTAP ligands are expected to tune the surface toward a more neutral or slightly positive surface charge, which is expected to enhance the cellular uptake of the AuNRs compared to negatively charged nanoparticles. DOTAP is a well-known cationic transfection agent that is used to enhance the delivery of liposomes37 and liposome-coated38 nanomaterials for drug delivery, and although excess CTAB is toxic, only a small amount was integrated into the membrane scaffold to enhance cellular uptake. Similarly, the lipid-conjugated cell-penetrating peptide, PE-RGD, is also expected to enhance cellular uptake and labeling. After assembly, the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs were purified by ultracentrifugation to remove any excess lipids, thiol, dye-conjugated lipids, or SOA. It is important to remove any excess fluorescent dye from the solution after synthesis to ensure that the dye-labeled species being visualized is that of the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs and not “nanoparticle-free” liposome formulations containing PE-LRSH. Fluorescence spectra were taken from the first wash and the subsequent washes until no fluorescence in the washes of fluorescent-labeled hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs was observed to confirm that the hybrid AuNR solutions contained no free PE-LRSH dye (Figure S1). Lastly, AuNRs with dimensions between 10 × 55 and 25 × 96 nm were used because they had tuned surface plasmon resonance with absorption characteristics between 925 and 980 nm to match the operating wavelength of some commercially available OCT imaging systems and because AuNRs absorb in the NIR-II region.

The addition of a hybrid lipid-membrane to the AuNR does not change the optical properties of the AuNR as no significant shift in the LSPR band is observed. TEM confirmed that there was no change in the size or shape of the AuNRs after coating, and the particles were unaggregated (Figure S2). The zeta potential measurements for all purified hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs and commercially purchased AuNRs used in this study are reported in Table S1. The commercially purchased mSiO2/polymer-coated AuNRs all had a positive surface charge varying from +5 to +50 mV, while the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs had a slightly negative zeta potential at −5 to −7 mV even when cationic ligands such as DOTAP were incorporated into the platform. The DOTAP, CTAB, PE-LRSH, and PC ligands have an overall neutral or positive charge; therefore, the negative arises from the SOA molecules incorporated into the membrane architecture since the ratio of lipids/SOA/HT is 4:2:1, where there is a greater amount of SOA than ligands with cationic charges.

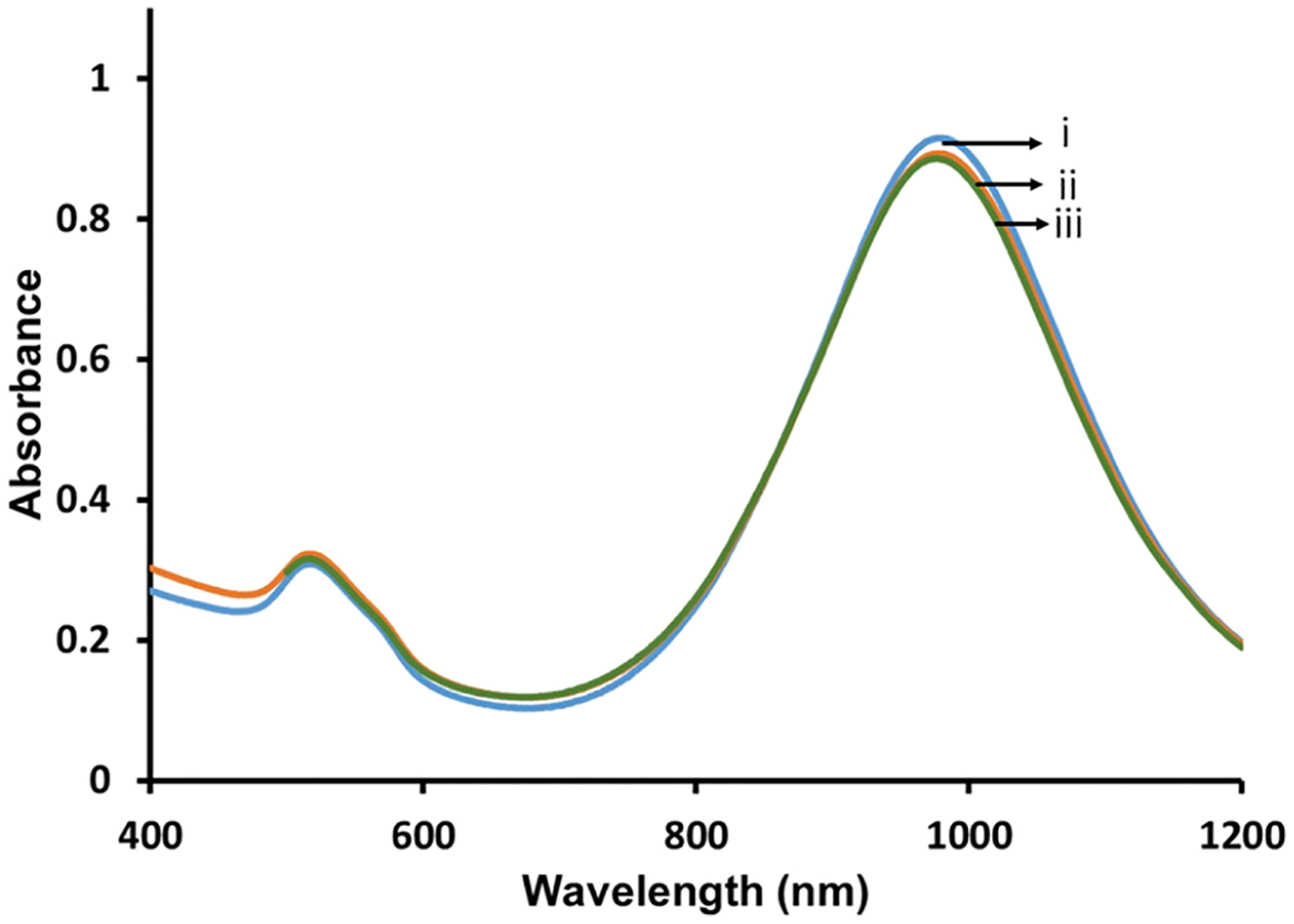

Previous studies show that hybrid lipid-coated AuNPs and AgNPs are resistant to strong oxidants only when the membrane is tightly packed around the nanoparticle surface.28,29,34 Therefore, to ensure that the AuNRs are completely covered by an intact hybrid bilayer, KCN, a well-known etchant, is added to every batch of hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs prepared. Briefly, a 700-fold excess of KCN was added to 1 mL of hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs (1.1 O.D.), and the LSPR band at λmax 980 nm was monitored over 24 h (Figure 1). No shift in the λmax or change in the O.D. was observed before (Figure 1i) or after 24 h of incubation with CN− (Figure 1ii). This indicates that the AuNRs are completely covered with a tightly packed membrane arrangement, which is consistent with what was previously observed.28,29 Similarly, when citrate-capped AuNRs without a hybrid lipid-coating are exposed to CN−, there is a rapid change in color from red to colorless within seconds and a disappearance of the LSPR band (Figure S3). Hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs that are completely shielded and stable in the presence of strong oxidants are expected to have minimal interactions with biomolecules that could destabilize the nanoparticles in vitro or in vivo by undergoing ligand exchange or by binding directly with the gold surface. Consequently, these hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs are less likely to induce toxicity.

Figure 1.

Representative UV–vis spectra of 1 mL AuNR-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP (6:1:3) (i) before and (ii) after 1 h and (iii) 24 h of incubation with 20 μL of 307 mM KCN. All samples were in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 8.0.

Cellular Uptake Studies of Hybrid Lipid-Coated AuNRs.

Before AuNRs can be employed as cell-labeling or OCT contrast agents, it is necessary to evaluate their uptake in cells and potential toxicity. An increasing number of studies during the last decade show that the physicochemical properties of nanomaterials, size, shape,39 surface chemistry,40,41 and charge42 influence their cellular uptake, which is also dependent on the cell type.43–45 Therefore, it is important to screen each new type of nanomaterial for its impact on cellular uptake and toxicity. Here, a comparative study of a variety of hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs and the commercially purchased AuNRs coated with a 5 nm mSiO2 layer and a proprietary polymer from Nanopartz.com was carried out to evaluate how the surface coatings and their charge influence their efficiency of uptake, biocompatibility, and localization in baby hamster kidney cells (BHK), the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE), and neural progenitor (NP) cells. BHK cells are stable, non-pigmented, and inexpensive cells that are routinely maintained and are easy for screening and visualizing nanomaterial uptake. RPE cells are highly pigmented from melanin and are phagocytotic; therefore, a great number of nanoparticles are expected to be taken up in this cell type. NP cells are of interest because these cells are transformed into glial and neuronal cell types. Furthermore, both RPE and NP cells rescue vision in clinical studies at different developmental stages and do not need to undergo differentiation for therapeutic efficacy.46 These cell lines are important for our study to demonstrate the potential of AuNRs for stem cell labeling and tracking using OCT imaging.47,48

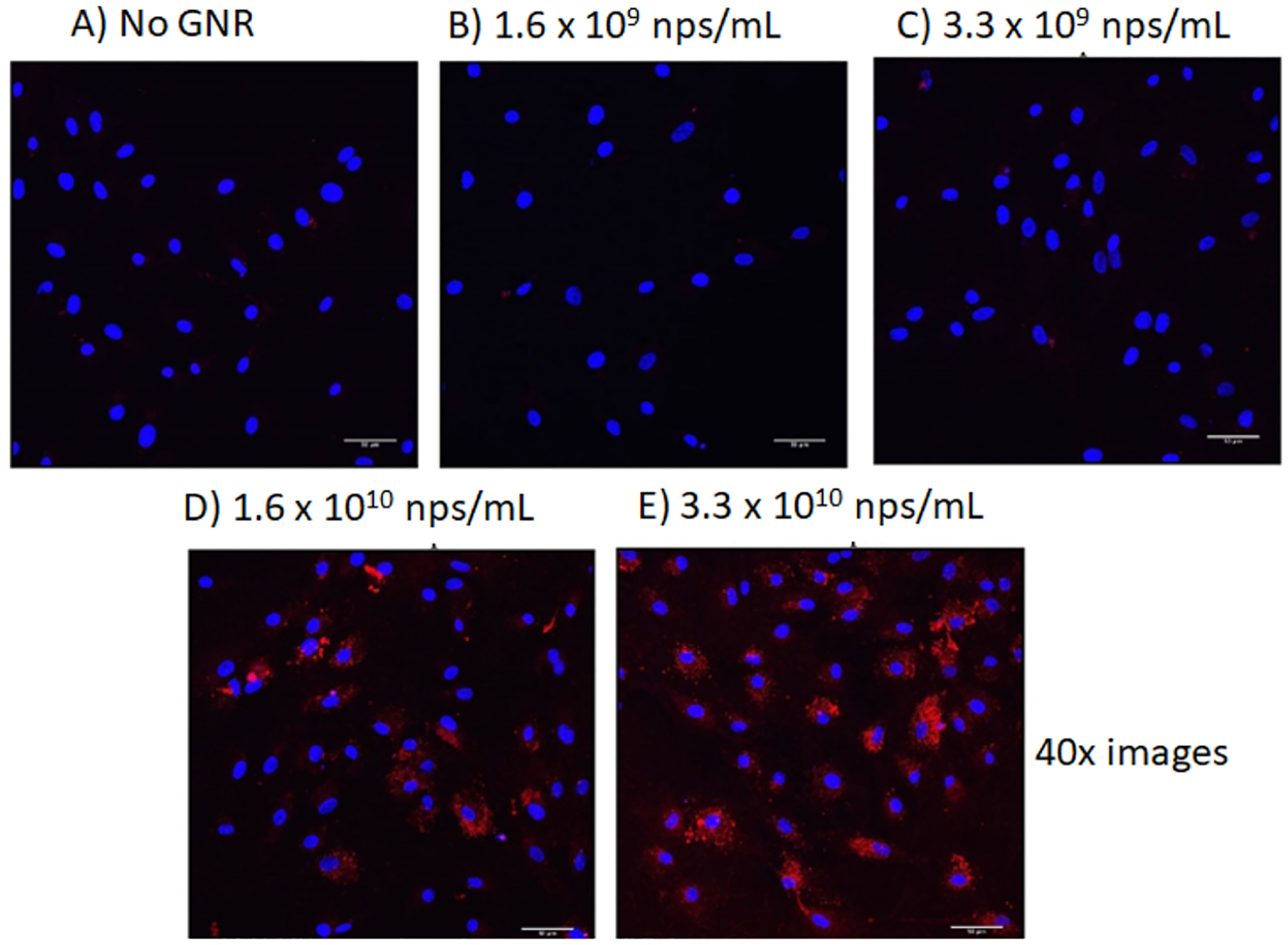

The two subtypes of AuNRs were applied to BHK, RPE, and NP cell lines. The BHK and RPE cells were grown and incubated in DMEM media with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in 24-well plates in triplicate, while the NP cell lines were cultured in STEMdiff medium. Cellular uptake was visualized by confocal microscopy using fluorescently labeled AuNRs. Briefly, AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT (PC/PE-LRSH ratio of 9:1) was incubated with 150,000 RPE cells (Figure 2) for 24 h in DMEM media. Confocal microscopy images at 40× magnification show that on increasing the concentrations of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT from 1.6 × 109 to 3.3 × 1010 AuNRs/mL, there is an increase in red fluorescence of the AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT indicating higher AuNR uptake as more nanoparticles enter the cell (Figure 2). No fluorescence is observed in control samples without AuNR (Figure 2A) and at lower applied AuNR concentrations at 1.6 × 109 nanoparticles/mL (Figure 2B). The blue fluorescence observed is from the DAPI dye used to stain the nucleus of the cell. Similarly, when AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT was incubated with BHK cells for 24 h at applied concentrations ranging from 3.3 × 108 to 3.3 × 1010 nanoparticles/mL, a proportional increase in the fluorescence is observed with an increase in AuNR concentrations (Figure S4), and no fluorescence is observed when AuNRs are absent or present in low concentrations. The observed fluorescence in BHK and RPE cells is not due to free PE-LRSH because before cell studies, the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs are extensively washed until no free lipid-conjugated LRSH is observed by fluorescence in the filtrate (Figure S1). Therefore, the observed fluorescence in the cells is because of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT internalization into the cell.

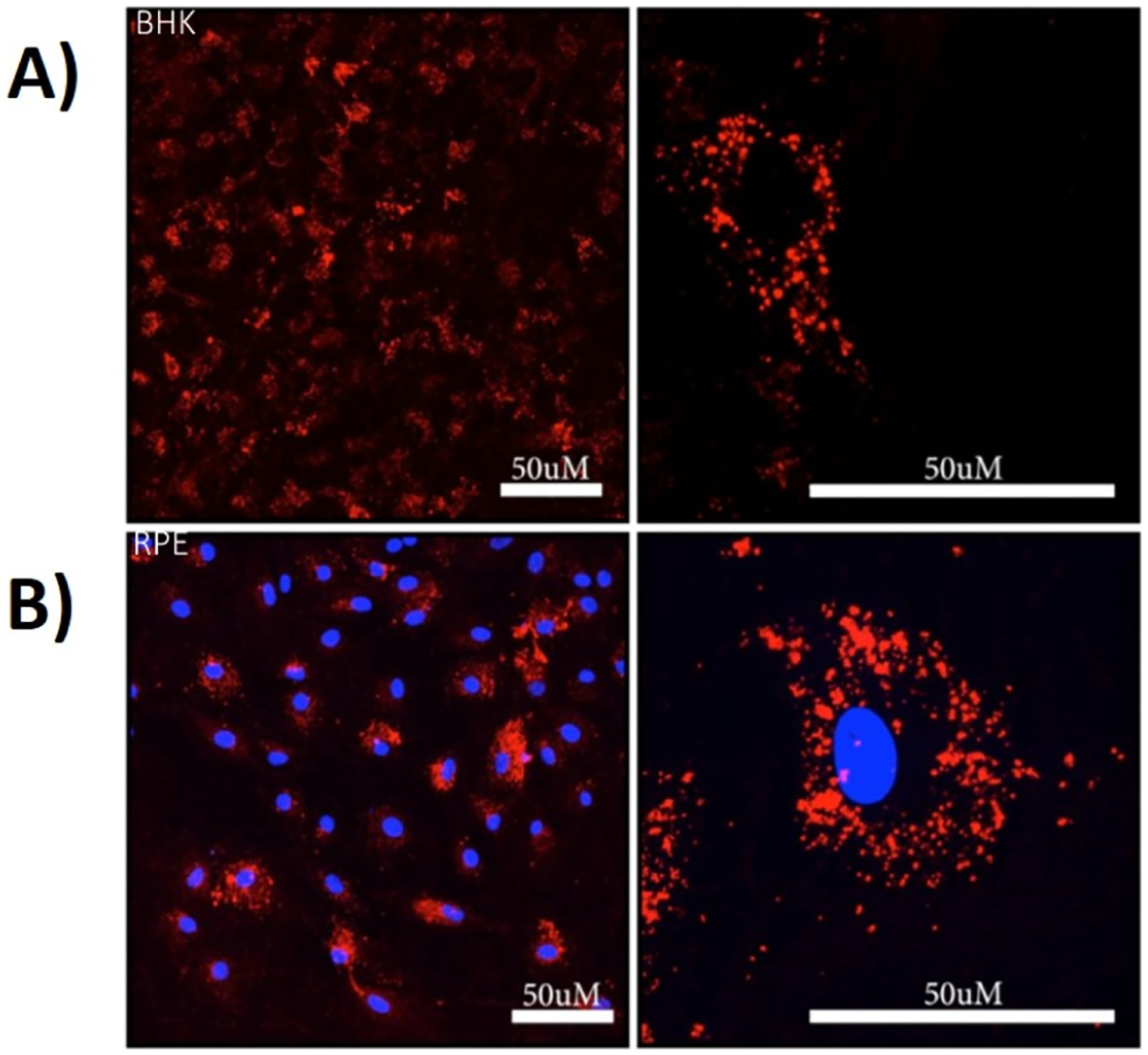

Figure 2.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images at 40× magnification of RPE cells (A) before and (B) after the addition of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT at an applied concentration of 1.6 × 109 AuNRs/mL, (C) 3.3 × 109 nanoparticles AuNRs/mL, (D) 1.6 × 1010 AuNRs/mL, and (E) 3.3 × 1010 AuNRs/mL. Blue fluorescence is from the DAPI-stained nuclei, and red is from the LRSH-labeled AuNRs. The scale bars indicate 50 μm. Cell concentration is 150,000 cells/mL.

While bright-field imaging is not possible with RPE cells because of their highly pigmented nature, the bright-field images of AuNRs in BHK cells showed that observed red fluorescence overlaps where the presence of AuNRs is observed to be physically localized in the cells. Note that the fluorescence observed is not due to individual dye molecules or many dye molecules conjugated onto a single AuNR. Instead, the observed fluorescence is due to many dye molecules on a cluster of nanoparticles as the microscopy images are taken at 40× magnification where single nanoparticles cannot be differentiated at a microscale resolution. Z-stack analysis of single cells shows that fluorescence is observed throughout the cell, confirming that AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT is internalized into the cells and not only located on the surface of the cell (Figure S5). Furthermore, magnification at the micron scale of a single cell shows that the AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT clusters are localized in the cytoplasm of the cell surrounding the nucleus in both BHK and RPE cells (Figure 3). BHK cells in the absence of DAPI nuclear staining show that the AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT are in the cytoplasm surrounding a dark center where the nucleus should be present (Figure 3A). Similarly, in the RPE cells, when the nucleus is stained with DAPI, fluorescence is observed surrounding the nucleus (Figure 3B) with little to no overlap of PE-LRSH fluorescence overlapping the blue DAPI dye, confirming that the AuNRs are mostly localized in the cytoplasm of the cell. Furthermore, the incubation of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT with RPE and BHK cells shows that no morphological changes or visible signs of cell death are observed within 24 h, indicating that AuNRs are biocompatible in vitro. Lastly, while the mechanism of uptake was not evaluated in these preliminary studies, it is expected that the AuNRs with a slightly negative to neutral charge enter the cell through endocytosis and accumulate in the cytoplasm as visualized by the red fluorescence surrounding the blue DAPI-stained nucleus (Figure 3B) compared to cationic nanoparticles that likely enter by diffusing into cells by generating holes or other disruptions to the cell membrane.49 These studies demonstrate large (70 × 12 nm) hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs with zwitterionic lipids that can enter BHK and RPE cells easily with minimal impact on cell health, which is confirmed from cytotoxicity studies, vide infra.

Figure 3.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images (left 40× and right 63× magnification) of (A) BHK and (B) RPE cells after incubation with an applied concentration of 5 × 1010 AuNRs/mL of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT for 24 h in DMEM with 150,000 cells/mL. Blue fluorescence is from DAPI-stained nuclei, and red is from PE-LRSH-labeled AuNRs. The scale bars equal 50 μm resolution.

Effect of Surface Charge of Modified AuNRs.

To evaluate the effect of surface charge on the efficiency of uptake, AuNRs of the same size and varying charges were studied. AuNRs with hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs modified with cationic DOTAP or CTAB ligands were compared to the AuNRs with the mSiO2 layer with the proprietary polymer conjugated to LRSH or cyanine (Cy3) dyes and with varying zeta potentials purchased from Nanopartz.com (Table S1). Liposomes prepared with PC, PE-LRSH, and DOTAP or CTAB in a 6:1:3 ratio were coated onto AuNRs and anchored with HT to yield AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/CTAB-HT. The AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT was incubated with BHK cells with varying concentrations of AuNRs/mL in DMEM for 24 h. Qualitative inspection of the confocal microscopy images taken at 40× magnification revealed an increase in red fluorescence surrounding the DAPI-stained nucleus with increasing concentrations of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT (Figure 4A). That is, when comparing AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT at 4.1 × 1010 AuNRs/mL (Figure 4A) to a similar concentration of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT (5 × 1010 AuNRs/mL) (Figure 3B) without DOTAP, there is a noticeable increase in the red fluorescence of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT around the cell nuclei suggesting more AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT uptake. A similar increase in fluorescence is observed when AuNRs are prepared with CTAB, another cationic ligand (Figure S7). Confocal and bright-field images of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/CTAB-HT with a 6:3:1 ratio of PC/PE-LRSH/CTAB show a similar enhancement in fluorescence and clustering of AuNRs in the cellular cytoplasm of BHK cells (Figure S7) compared to AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT (Figure 3A) at similar concentrations (5 × 1010 AuNRs/mL). This confirms that when cationic ligands are present, there is an increased uptake of hybrid lipid-coated AuNR into cells. The increased cellular uptake of lipid-coated hybrid AuNRs containing DOTAP or CTAB suggests different mechanisms are responsible for cellular uptake and need to be investigated further. Lastly, visual inspection showed noticeable cell death with AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-CTAB-HT compared to AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/CTAB-HT. This is not surprising as CTAB is known to be toxic and is not an ideal ligand for coating nanoparticles.50

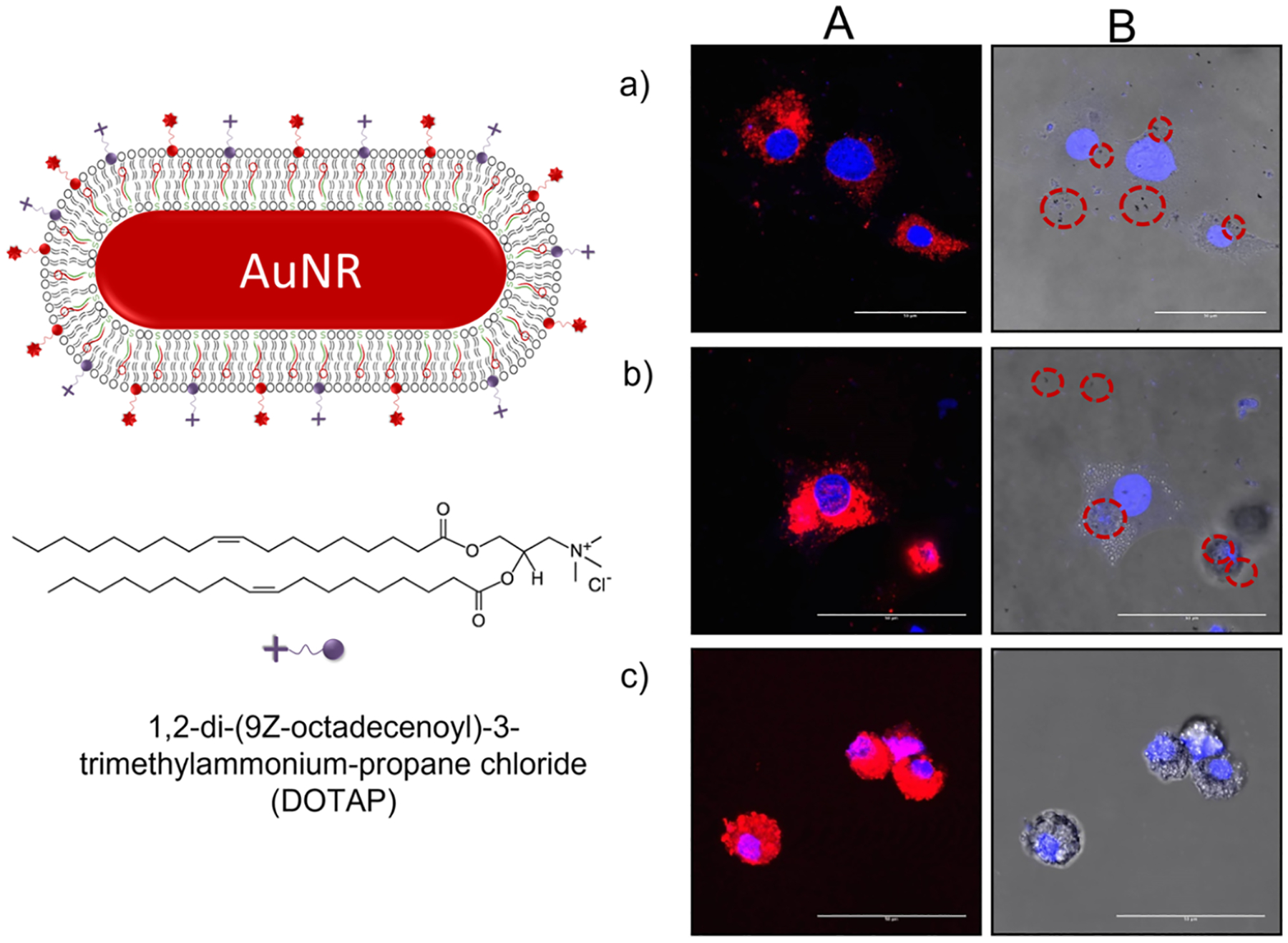

Figure 4.

(A) Confocal laser scanning microscopy images at 40× magnification with a 4× digital zoom and (B) bright-field images of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH-HT incubated at (a) 4.1 × 1010 nps/mL, (b) 8.3 × 1010 nps/mL, and (c) 4.1 × 1011 nps/mL incubated with 150,000 RPE cells per mL for 24 h in DMEM. Blue fluorescence is the DAPI-stained nuclei, and red is PE-LRSH-labeled AuNRs. The scale bars indicate 50 μm. Red circles indicate where large aggregates of AuNRs are seen in the bright field.

In contrast, incubation of AuNR-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 nanoparticles with an average length of 55 nm and a width of 10 nm, a zeta potential of +5 mV, and an applied concentration of 8 × 1010 AuNRs/mL with BHK cells in DMEM for 24 h showed an increase in red fluorescence surrounding the DAPI-stained nucleus from the Cy3-conjugated onto the polymer on the AuNR surface (Figure 5A). This suggests that slightly positively charged AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 are also being taken up into the cytoplasm of the cells. With increasing applied concentrations of the AuNR-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 from 8 × 1010 AuNRs/mL to 4 × 1012 AuNRs/mL, there is an increasing appearance of red fluorescence that eventually overlaps with the DAPI-stained nucleus [Figure 5A(b–e)]. This overlap in fluorescence suggests that the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 are localized in the cytoplasm as well as on the exterior cell surface, as supported in the bright-field images where an abundance of AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 nanoparticles completely cover the cell body [Figure 5B(e)]. In both BHK and RPE cells, there is an accumulation of AuNRs inside and outside of the cells, and the AuNRs appear aggregated (Figure S8). The aggregation of nanomaterials is known to play a significant role in hindering the cellular uptake of nanomaterials.51,52 While the confocal and bright-field images appear to show greater uptake of AuNR-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 with a zeta potential of +5 mV compared to hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs with an overall slightly negative zeta potential, in general, at higher concentrations of 4 × 1012 AuNRs/mL there is a loss of cell adhesion to the culture dish and globular GNR aggregation.

Figure 5.

Representative (A) confocal laser scanning microscopy images and (B) bright-field images at 40× magnification of BHK cells (a) without AuNRs and BHK cells incubated with increasing concentrations of AuNR-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 at (b) 8.0 × 1010 nps/mL, (b) 4.0 × 1011 nps/mL, (c) 8.0 × 1011 nps/mL and (d) 4.0 × 1012 nps/mL. All AuNR samples were incubated with 150,000 cells/mL for 24 h in DMEM. Blue fluorescence is the DAPI-stained nuclei, and red is Cy3-labeled polymer-coated mSiO2-layered AuNRs. The scale bars indicate 50 μm.

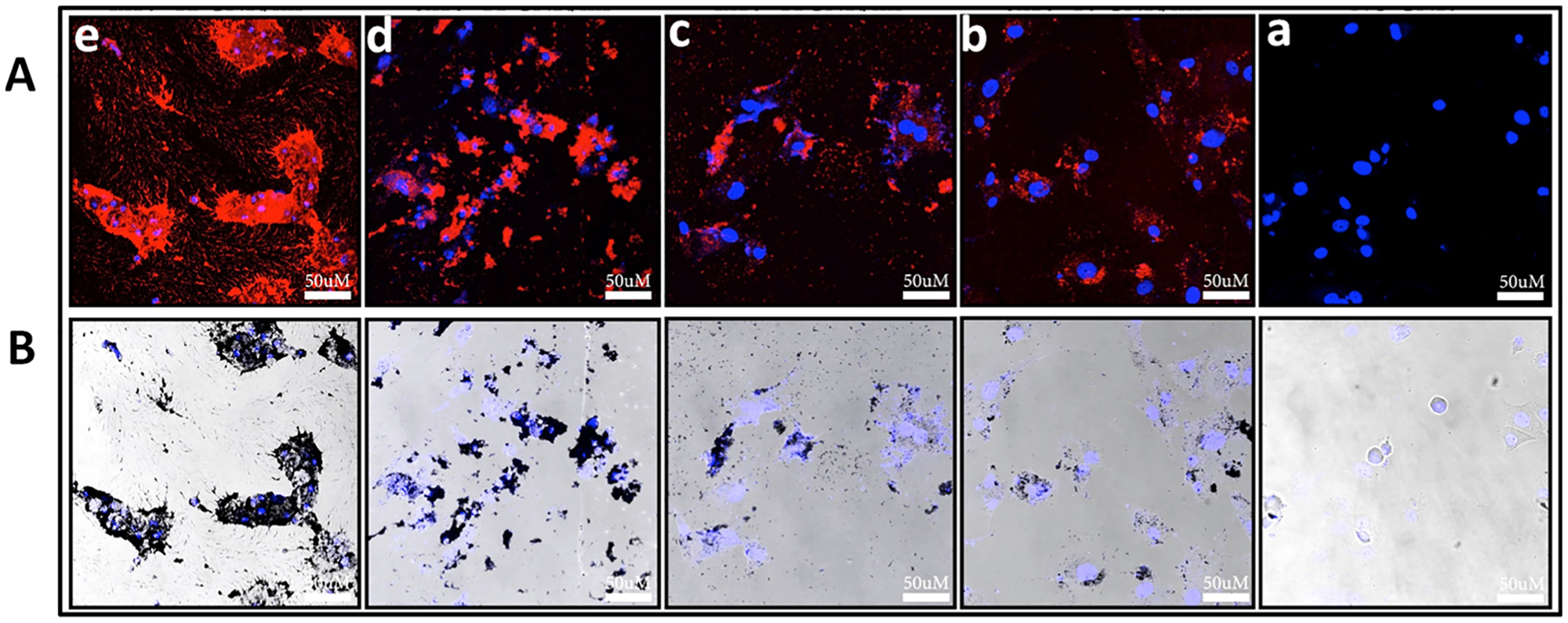

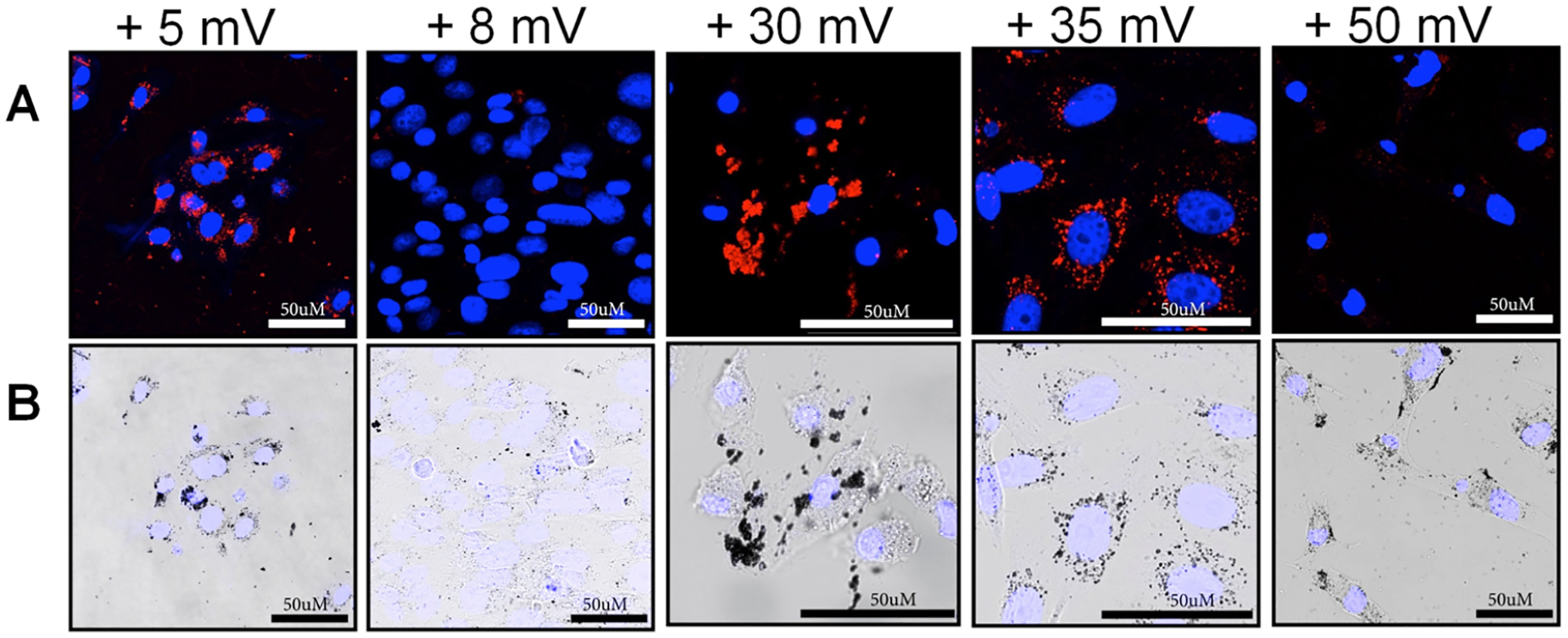

To further investigate the impact of increasing the cationic charge of the mSiO2 polymer-coated AuNRs, a series of AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH nanoparticles with an average length of 95 nm and a width of 25 nm with increasing positive zeta potential from +5 to +50 mV (Table S1) were incubated with BHK cells (Figure 6). The applied AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH concentration (5 × 1010 AuNRs/mL) is the same in each sample with 150,000 cells/mL. Representative confocal and bright-field microscopy images show that all AuNRs are taken up into the BHK cells to varying degrees based on the variable amount of fluorescence observed for AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH with zeta potentials of +8, +30, +35, and +50 mV (Figure 6). Bright-field images show significant nanoparticle aggregates (Figure 6B) with diminished fluorescence as the cationic charge of AuNRs (Figure 6A). Minimal or no fluorescence is observed with AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH at +8 and +50 mV (Figure 6A). Closer inspection of images shows punctate fluorescence staining from AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 at +5 mV and AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH at +30 mV zeta potential (Figure 6B), indicating some internalization of the AuNRs in the cytoplasm of the cells surrounding the DAPI-stained nucleus. In contrast, globular fluorescence is observed with AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH with a +30 mV zeta potential (Figure 6A), suggesting a lack of internalization as confirmed in the bright-field images where the AuNRs appear to be agglomerated on the surface (Figure 6B). Based on these observations, the cationic AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH nanoparticles have a greater propensity for nanoparticle–nanoparticle interactions and the agglomerates observed are most likely due to the interaction of the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH with proteins in the media affecting nanoparticle stability and cellular uptake.

Figure 6.

Representative (A) confocal laser scanning microscopy images and (B) bright-field images at 40× magnification with a 4× digital zoom of BHK cells incubated with 5.0 × 1010 AuNRs/mL of AuNR-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH with increasing the positive charge (right to left). All AuNR-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH samples were incubated with 150,000 cells/mL for 24 h in DMEM. Blue fluorescence is the DAPI-stained nuclei, and red is LRSH-labeled polymer-coated mSiO2-layered AuNRs. The scale bars indicate 50 μm.

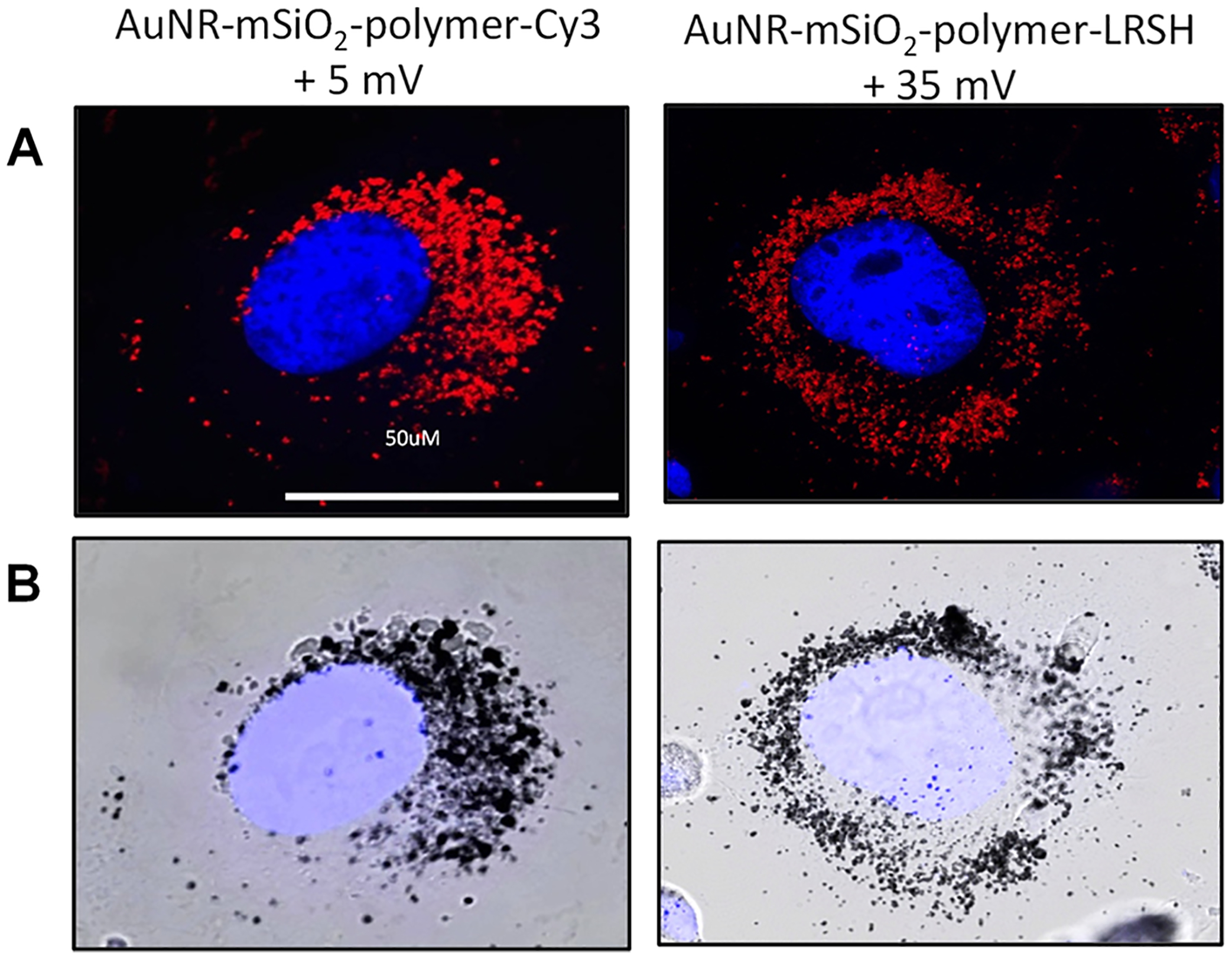

Interestingly, in a qualitative comparison with the number of AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH nanoparticles visibly present in the BHK cells (Figures 7B and 8B), it is interesting to note that the fluorescence is not as bright compared to the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs of a similar concentration and magnification (Figures 2 and 3). In some cases, there is minimal or no fluorescence observed particularly with AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH with a zeta potential of +50 mV (Figure 6A). A major difference between the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH and the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs is the surface charge and ligand coating on the AuNR surface. The AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH are coated with a proprietary positively charged polymer coating that is very “sticky” such that it interacts with the pipette tips and cell culture plates compared to the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs. Their inherent “sticky” nature is the driving force behind nanoparticle–nanoparticle, nanoparticle-protein, and nanoparticle–cell interactions. The level of nanoparticle–nanoparticle and nanoparticle–cell interactions is seen in Figure 7, where the AuNRs are internalized into the cytoplasm as aggregates surrounding the nucleus and are on the surface of the cell. The resultant nanoparticle–nanoparticle interactions observed here are hypothesized to induce a fluorescence quenching effect and are consistent with the aggregation of polymeric and metal-based nanomaterials.53–55 The level of nanoparticle aggregation observed with the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH on the surface of cells would not be a concern for applications where the goal is to visualize the delivery of therapeutics and monitor cell death; however, it could be problematic if their dissociation from the cell surface and migration to non-transplanted cells in the eye leads to false positives. In addition to impacting cell function, significant aggregation inside of the cell would change their optical properties, which might affect our ability to track them using OCT at specific operating wavelengths.

Figure 7.

Representative (A) confocal fluorescence microscopy and (B) bright-field images at 63× magnification of BHK cells incubated with 5.0 × 1010 AuNRs/mL of the AuNR-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 (55 × 10 nm) with +5 mV zeta potential and the AuNR-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH (96 × 25 nm) with a +35 mV zeta potential. All mSiO2-polymer-AuNR samples were incubated with 150,000 cells/mL for 24 h in DMEM. Blue fluorescence is the DAPI-stained nuclei, and red is Cy3 or LRSH dye-labeled polymer-coated mSiO2-layered AuNRs. The scale bars indicate 50 μm.

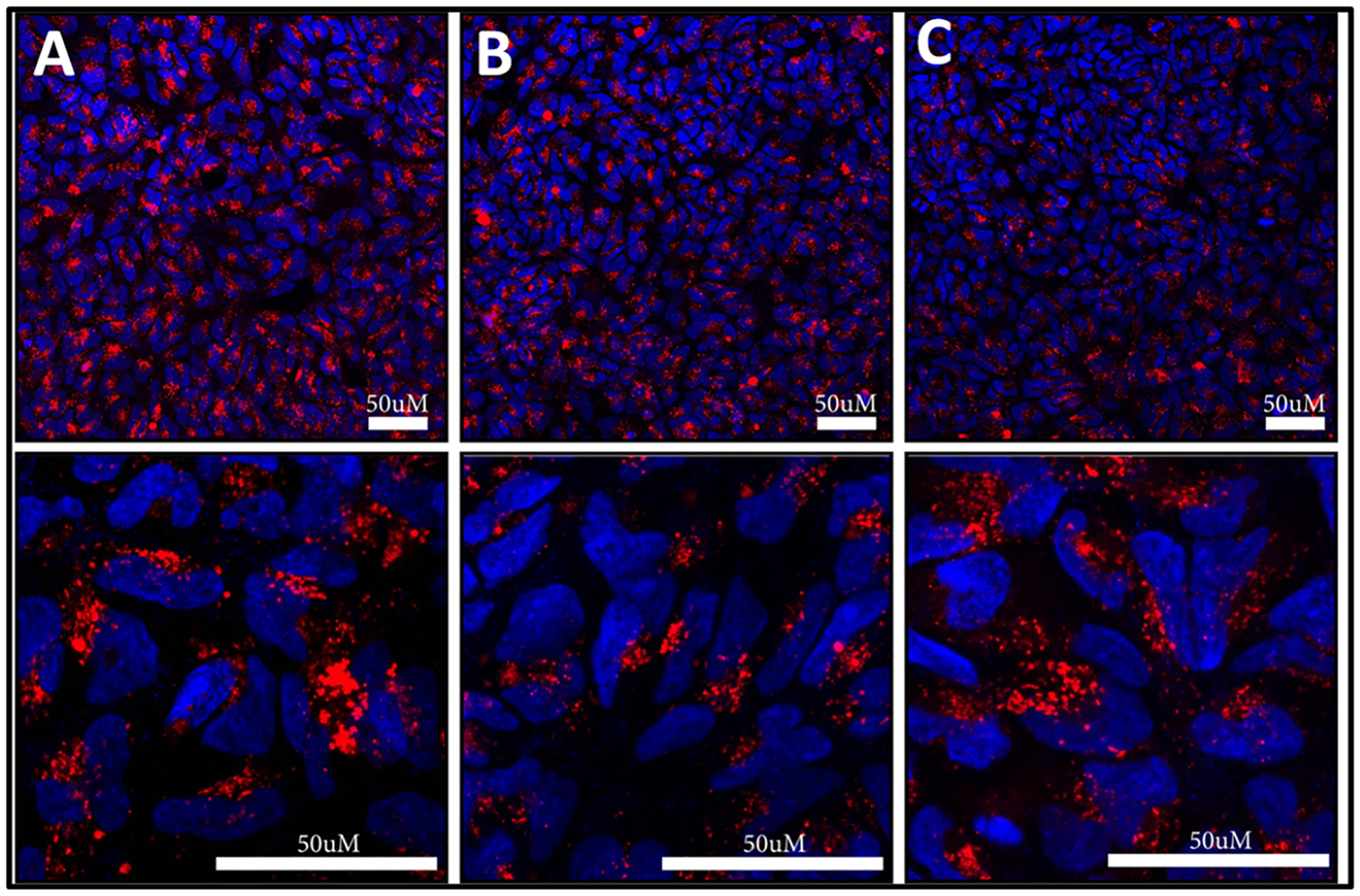

Figure 8.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy images of NP cells incubated with 5 × 1010 AuNRs/mL of (A) AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT, (B) AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/PE-RGD-HT, and (C) AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/PE-RGD/DOTAP-HT in DMEM for 24 h. Blue fluorescence is the DAPI-stained nuclei, and red is PE-LRSH-labeled AuNRs. The top panel is at 40× magnification, and the bottom panel is at 40× magnification with a 4× digital zoom. The scale bars indicate 50 μm.

Effect of Cell-Penetrating Peptides on Cellular Uptake.

The AuNRs were also modified with a cell-penetrating peptide, RGD, as another strategy for enhancing the cellular uptake and biocompatibility of the AuNRs. Hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs were prepared RGD peptides with and without DOTAP, AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT (lipid ratio of 8:1:1), and with AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT (lipid ratio of 7:1:1:1). The combination of the RGD peptide and DOTAP was employed to examine if the addition of the RGD and cationic agent further enhances cellular uptake than the cationic ligand or cell-penetrating peptide alone. A comparison of representative confocal microscopy images of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT shows a similar amount of red fluorescence in NP cells (Figure 8B,C) suggesting that a similar number of AuNRs are taken up into the NP cell. Furthermore, when AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT (5 × 1010 AuNRs/mL) are compared to AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT (4.1 × 1010 AuNRs/mL), which has threefold more DOTAP, a similar amount of red fluorescence is observed (Figure 8A). These studies suggest a similar amount of cellular internalization for AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT in cells (Figure S6), which is not surprising since their zeta potentials are similar and range from −7.8 to −4.4 mV. AuNRs modified with RGD peptides or with slightly negative to neutral charges will enhance their internalization in cells. Except for the AuNR platform with CTAB, the addition of RGD or DOTAP to the membrane composition did not have any visually observable adverse effects on cell health and is consistent with previous studies where hybrid lipid-coated spherical AuNPs (10–20 nm) and triangular plate-shaped AgNPs (32 nm) of various sizes and shapes with a similar hybrid lipid-coating were found to be non-toxic and biocompatible in vivo using an embryonic zebrafish model.28,32,33

Quantitative Cellular Uptake Studies (ICP-MS) and TEM.

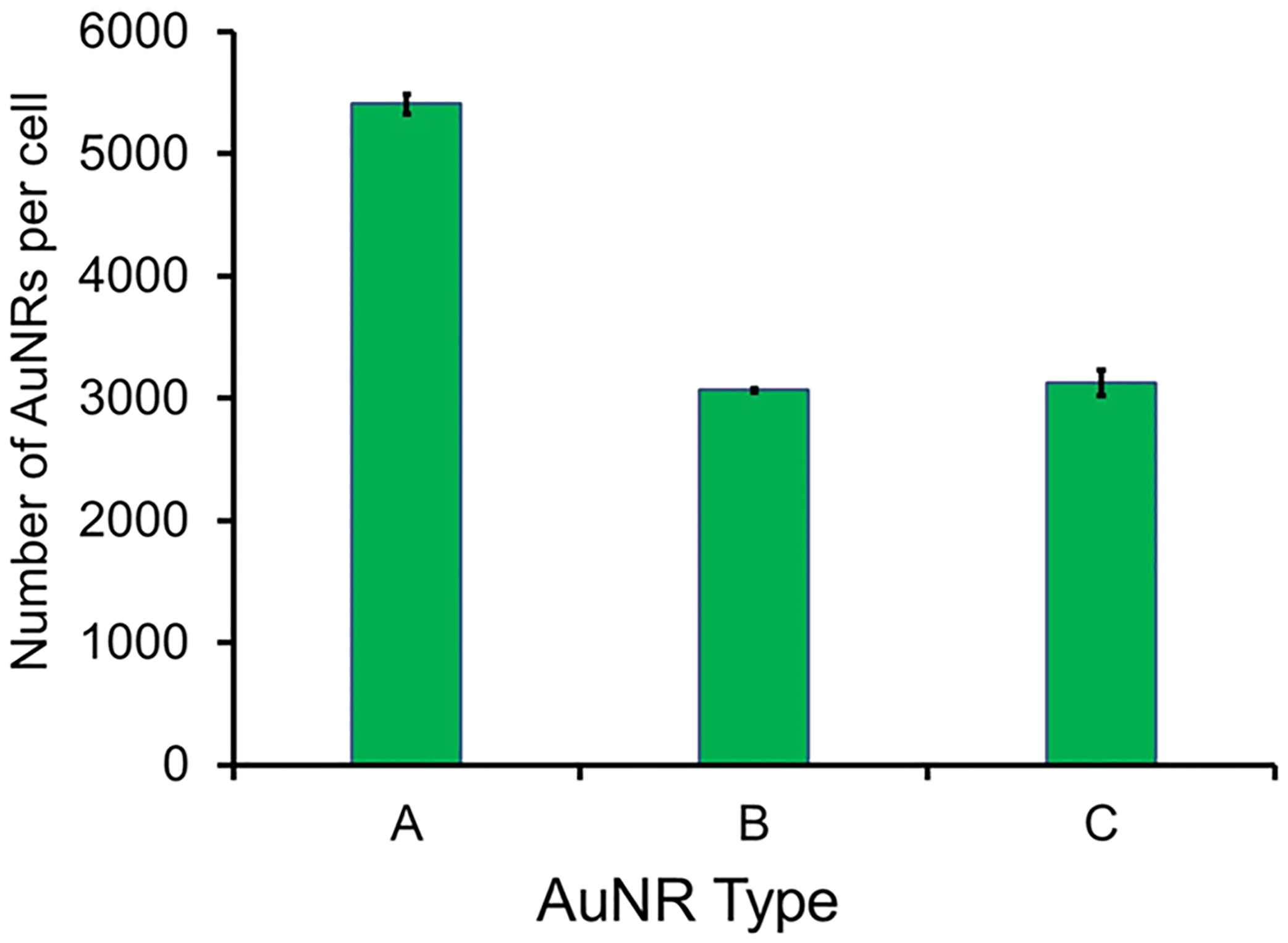

To confirm that the AuNR platforms are taken into the cytoplasm and not just adhering to the surface of the cell, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was used to quantify the number of AuNRs taken up per cell. Approximately 5 × 1010 AuNRs/mL of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT, AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT, or AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH with a +35 mV zeta potential were applied and incubated with 1 × 106 BHK cells/mL in DMEM media at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed with copious amounts of 10 mM PBS buffer at pH 7.4 to remove surface-bound AuNRs before digestion using standard protocols for ICP-MS analysis to detect the Au content left in the washed samples. The Au content and the dimensions of the AuNRs were used to estimate the number of AuNRs internalized per cell. After 24 h, approximately 5400 AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH with a +35 mV zeta potential were detected in the BHK cells (Figure 9). In contrast, about 3067 and 3126 of AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT, respectively, were found to be internalized into the BHK cells, which are non-phagocytotic (Figure 9). The similar amount of cellular uptake of the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs is consistent with comparable levels of fluorescence observed in the confocal fluorescence microscopy images (Figure 6A,B). While the ICP-MS analysis shows the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH with a +35 mV zeta potential had ~2300 more AuNRs than the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs, the fluorescence is not as bright because of the self-quenching from aggregation. Similar differences in uptake based on fluorescence are observed with AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH with a +50 mV zeta potential, AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT, and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT in phagocytotic RPE cells (Figure S9). The amount of aggregation and uptake observed for the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH nanoparticles is consistent with visual cellular assessment by bright-field microscopy in RPE and BHK cells. Since cell membranes are predominantly negatively charged and because of the “sticky” nature of these polymeric nanoparticles, it is not surprising that more cationic AuNRs are found inside the cells. However, the amount quantitatively determined by ICP-MS is less than what is expected based on the level of uptake observed by microscopy images (Figure 6), which suggests that a great majority of the polymeric nanoparticles were also on the surface of the cells.

Figure 9.

Quantification of AuNR uptake in BHK cells by ICP-MS. 5 × 10 AuNRs/mL of (A) AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH at +35 mV, (B) AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT, and (C) AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT were incubated with 106 BHK cells/mL for 24 h in DMEM at 37 °C. Data are reported as the average number of AuNRs/cell from triplicate trials.

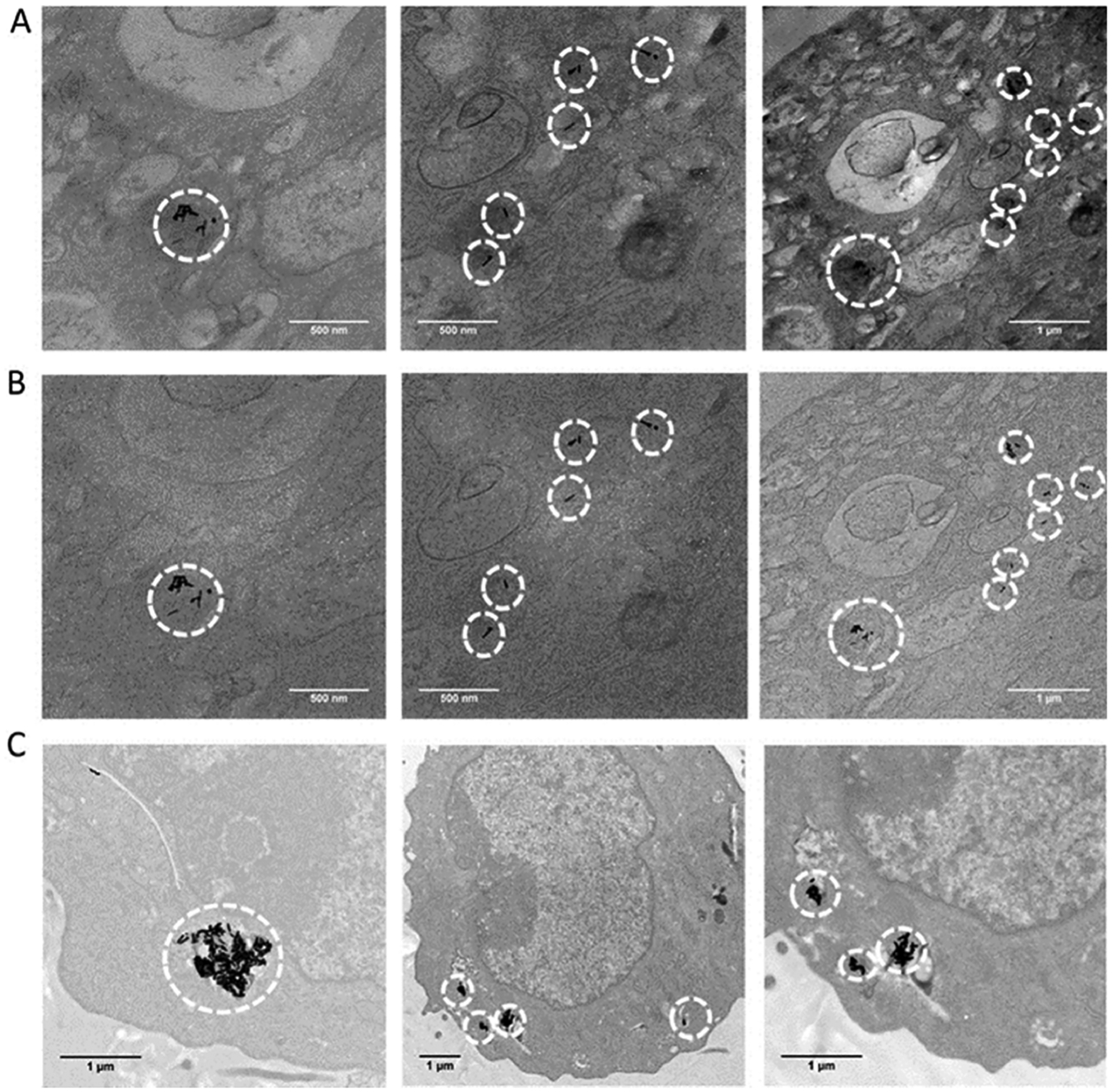

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was also used to visually confirm the intracellular localization of the AuNRs. The AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT was incubated with BHK cells for 24 h followed by TEM imaging with and without an objective aperture (Figure 10). The TEM images show gold nanorods inside of the BHK cell cytosol, further confirming that the AuNRs are taken up into the cells. The 69 × 12 nm AuNRs can be seen localized into lysosomal compartments in small clusters or as single nanoparticles (Figure 10A). Not surprisingly, the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH nanoparticles with +50 mV appeared glomerated inside of the cell and are consistent with the confocal and bright-field microscopy imaging (Figure 10B).

Figure 10.

TEM imaging of BHK cells after 24 h incubated with AuNR-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT (8:1:1) (#9 Table S1) stained with 1% osmium tetroxide (A) with objective aperture and (B) without objective aperture. TEM images reveal accumulation of AuNRs as black granules in the cytosol (red arrows), and (C) AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH nanoparticles #5 unstained. The scale bars indicate 500 nm (2 left columns) and 1 μM (far right column and bottom).

Evaluating the Effect of Cell Culture Medium on Nanoparticle Stability.

The stability of nanomaterials is influenced by chemical and physical transformations upon contact with biological environments such as saliva, blood, and media. For example, when nanoparticles are exposed to the bloodstream, they interact with opsonin proteins that attach to the surface of the nanoparticles, forming a protein corona.52,56–59 Protein–nanoparticle interaction then triggers the mononuclear phagocytic system that recognizes the protein–nanoparticle complexes for clearance and accumulates them in the liver and spleen. Concomitantly, this results in low targeting efficiency, poor delivery of drug and imaging agents, and toxicity. The surface chemistry of the nanoparticles can also trigger aggregation resulting in nanoparticle–nanoparticle interactions from components of the media such as proteins.57,58 While aggregated nanoparticles in the cell can lead to longer intracellular retention of AuNRs and possess a desirable property for cell labeling and imaging,59 in most cases, nanoparticle aggregation in the media is not desired. Large aggregates formed outside of the cell are not expected to be taken up easily as seen with transferrin-coated AuNPs52 and can significantly affect uptake efficiency and cytotoxicity. Stability studies in cell culture media are important to examine the effect of the nanoparticle coating on nanoparticle stability resulting in aggregation from nanoparticle–nanoparticle interactions and nanoparticle–cell interactions, which affect cellular uptake efficiency and cytotoxicity.60 Therefore, to understand the impact of the media on the stability of the AuNRs, hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs and AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH were incubated in water, 10 mM PBS buffer at pH 7.4, NP media, and DMEM (Figure S10). AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH nanoparticles with zeta potentials at +50 and +35 mV show various levels of aggregation in all four media used in the study (Figure S10A,B). AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH (+50 mV) show significant aggregation in NP media, followed by 10 mM of PBS buffer at pH 7.4 (Figure S10A), while AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH (+35 mV) show a significant aggregation in water > NP media > DEMEM > 10 mM PBS buffer pH 7.4 (Figure S10B). Interestingly, the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH (+35 mV) are less aggregated in 10 mM PBS buffer at pH 7.4 and show more nanoparticle–nanoparticle interactions in DMEM < NP media. The hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs, the AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT (−4.8 mV), and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT (−6.6 mV), were mostly stable in all media except NP media where more significant aggregation was observed (Figure S10C,D). All subtypes of AuNRs show significant aggregation in NP media, which suggests that specific protein(s) or small molecules in this media type interact with the AuNR surface to drive nanoparticle–nanoparticle interactions. The AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT has a slightly more negative charge than AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT, allowing for more nanoparticle interactions with small molecules or proteins in the media. Similarly, the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH nanoparticles with a +50 mV zeta potential (Figure S10A) show more aggregation in the NP media than the subtype with a +35 zeta potential (Figure S10B). The aggregation observed in the media explains why many AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH nanoparticles surround the cell. Although less aggregation is observed for the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs, higher uptake is observed with the positively charged AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH (+35 mV) from ICP-MS studies. Although the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs have a slight overall negative charge that would hinder uptake into negatively charged cells, about ~3000 AuNRs are taken up in each cell. These observations suggest that a protein corona is formed around positively and negatively charged AuNRs to produce new surface chemistries with different cellular uptake efficiencies via receptor-mediated endocytosis.61–63 In studies with serum proteins, over 70 different proteins can be adsorbed with different grafting densities on the nanoparticle surfaces, which significantly influences their mechanism and amount of uptake.57 It is likely that the same type and several proteins in the DMEM are presented on the AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH, AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT, and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT nanoparticles that result in similar uptake in BHK and RPE cells.

Cytotoxicity Studies.

Despite the great potential of AuNRs for diagnostic, drug delivery, imaging, and therapeutic applications, their possible toxicity has become a concern that must be addressed if we are to advance them for in vivo applications. That is, their safety and biocompatibility are of paramount importance if they are to be used for stem cell labeling or imaging agents. Therefore, we carried out a comparative study of the effect of the surface coatings on the cytotoxicity of the two subtypes of AuNRs. Briefly, 10,000 BHK cells were exposed to varying concentrations of 5.0 × 108 to 5.0 × 1010 AuNRs/mL for 24 h (Figure S11). The AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-Cy3 (#1), AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH (#3), AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT (#8), and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD-PE/LRSH/DOTAP-HT (#10) decreased the cell viability to 80 ± 8% with increasing concentrations of AuNRs, indicating mild toxicity. In contrast, the AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT (#9) showed very minimal cell death (92 ± 7%) indicating that this platform with the least negative charge is the most biocompatible with increasing concentrations (Figure S11). Although the surface chemistry of the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs is different and the shape of the nanomaterials is rod-shaped, the results are consistent with previous in vivo embryonic zebrafish studies that show when spherical gold or triangular plate-shaped silver nanomaterials are coated with membranes anchored by long-chained hydrophobic thiols, the nanomaterials are biocompatible.32,33 These studies also suggest that nanoparticles with neutral or slightly negative charge might be more appropriate for long-term cell viability of stem cell-derived therapeutic cells and use as OCT contrast agents.

CONCLUSIONS

Cell-based therapy has amazing potential to be able to treat a myriad of human diseases. A critical component of the success of cell-based therapy is the continued survival of the transplanted cells after implantation into the body. Current technologies for tracking implanted cells are limited primarily to fluorescence-based approaches, which have significant limitations. Thus, our efforts have focused on the development of nanoparticles with optical properties that could be used for high-resolution visualization within the body. We have developed nanoparticles that are compatible with current OCT retinal imaging technology to label prospective therapeutic cells used for retinal disease. In the development of this technology, it became apparent that many variables impact the biological interaction between the nanoparticles and prospective therapeutic cells, which is the focus of our studies here.

We demonstrated that the surface coating on AuNRs can affect their stability, cellular uptake, and viability in RPE and NP cell lines. A greater uptake of hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs is observed with membrane compositions that have mixtures of cationic ligands such as DOTAP or cell-penetrating ligands such as RGD compared to hybrid lipid-membrane architectures with zwitterionic PC lipids alone. In contrast, while more positively charged AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH are taken up in BHK and RPE cell lines (5400 nanoparticles/cell) without causing cell death, they show significant nanoparticle–nanoparticle interaction in water and 10 mM PBS buffer at pH 7.4, which is enhanced greatly in the presence of small molecules and proteins in the cell media and the cytoplasm of cells. In general, the slightly negatively charged hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs show greater stability in cell media and minimal nanoparticle–nanoparticle interactions and are less susceptible to the protein–nanoparticle interactions. Overall, the cell viability was 80%, except for the least negatively charged hybrid lipid-coated AuNR, AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-RGD/PE-LRSH-HT (#9), which had a cell viability of 92%. Stability studies in media demonstrate that proteins in the media interact with the AuNRs to form a protein corona on the surface that dictates their stability and likely is different on positively and slightly negative AuNRs, which will govern their mechanism of uptake and stability inside the cells. Overall, our studies show that both AuNRs-mSiO2-polymer-LRSH and hybrid lipid membrane-coated AuNRs are good platforms for enhancing the cellular uptake of AuNRs into stem cell-derived therapeutic cells. However, the hybrid lipid-coated AuNRs have greater stability in media and do not aggregate inside of the cells, which could enhance their long-term retention inside the cytoplasm of the cells. In addition, the hybrid lipid membrane platform is versatile for easily producing libraries of AuNRs with tunable membrane compositions for controlling the charge and the concentration of targeting ligands that can adhere to the cell surface or subcellular organelles to improve cell-labeling and tracking of stem cells using OCT in vivo.

Current and future efforts to continue the development of this cell-labeling technology include confirmation of visualization in vivo and evaluation of the safety profile of the nanoparticles. While simple in principle, visualization of labeled cells in vivo will require a series of carefully executed studies that determine the number of nanoparticles per cell required to detect a signal, the minimum number of cells per transplant/per visualized area, impacts of other sources of light scatter or absorption such as in vivo pigmentation (use albino or pigmented animal models), and optimization of SPR of the nanoparticles in vivo (which may be different from in vitro), among a plethora of other critical components. Perhaps, the most critical component of understanding this technology is understanding what happens to the nanoparticles and the signal they provide if the transplanted cells die or are rejected by the immune system, which is another focus of our future efforts. Safety evaluations will include necessary biodistribution and toxicity evaluations of direct nanoparticle injection in a dose-related manner. Ultimately, the continued development of this technology may have a significant value for evaluating cell survival and migration after transplantation; however, critical steps in understanding the fundamental properties of the nanoparticles and their interactions with cells ex vivo must be thoroughly vetted before exploration in vivo, as we have tried to do there.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant # RL5GM118963, UL1GM118964, and TL4GM118965 and by the National Science Foundation grant # 2145427. It was also supported by the Integrated Pathology Core at the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC), which is supported by the NIH Award P51 OD 011092. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Authors G.W.M., K.K., R.H., and F.Z. received support from # RL5GM118963, UL1GM118964, and TL4GM118965. J.S., R.R., S.S., and T.M. received support for the project through the Integrated Pathology Core at the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC), which is supported by the NIH Award P51 OD 011092. M.R.M., received support from NIH grants # RL5GM118963, UL1GM118964, and TL4GM118965 and the National Science Foundation grant # 2145427.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PE-RGD

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[4-p-(cysarginylglycylaspartate-maleimidomethyl)-cyclohexane-carboxamide]

- DOTAP

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane

- PE-LRSH

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl

- CTAB

cetyltrimethylammonium bromide

- PC

l-α-phosphatidylcholine

- HT

hexanethiol (HT)

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- ICP-MS

inductively coupled mass spectroscopy

- AuNPs

gold nanoparticles

- AuNRs

gold nanorods

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- NP

neural progenitor

- BHK

baby hamster kidney

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PET

positron emission tomography

- SOA

sodium oleate

- KCN

potassium cyanide

- PES

polyethersulfone

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- PS

penicillin streptomycin

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsanm.2c00958

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsanm.2c00958.

Calculations for the number of lipids to coat a AuNR; cyanide etch tests for nanoparticle stability; confocal microscopy of PC/PE-LRSH in BHK cells and PC/PE-LRSH/CTAB in BHK cells; microscopy studies of BHK cells incubated with AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/DOTAP-HT, AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/PE-RGD-HT, and AuNR-SOA-PC/PE-LRSH/PE-RGD-DOTAP-HT; confocal and bright-field microscopy images of mSiO2-zeta polymer-Cy3-labeled AuNRs incubated in BHK and RPE cells; and ICP-MS studies of AuNR uptake in BHK cells (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Grant W. Marquart, Department of Chemistry, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon 97207, United States

Jonathan Stoddard, Casey Eye Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon 97239, United States.

Karen Kinnison, Department of Chemistry, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon 97207, United States.

Felicia Zhou, Department of Chemistry, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon 97207, United States.

Richard Hugo, Department of Chemistry, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon 97207, United States.

Renee Ryals, Casey Eye Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon 97239, United States.

Scott Shubert, Casey Eye Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon 97239, United States.

Trevor J. McGill, Casey Eye Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon 97239, United States

Marilyn R. Mackiewicz, Department of Chemistry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Stone EM A very effective treatment for neovascular macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med 2006, 355, 1493–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zhou JY; Zhang Z; Qian GS Mesenchymal stem cells to treat diabetic neuropathy: a long and strenuous way from bench to the clinic. Cell Death Discovery 2016, 2, 16055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Limoli PG; Limoli C; Vingolo EM; Franzone F; Nebbioso M Mesenchymal stem and non-stem cell surgery, rescue, and regeneration in glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Stem Cell Res. Ther 2021, 12, 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Scarfe L; Brillant N; Kumar JD; Ali N; Alrumayh A; Amali M; Barbellion S; Jones V; Niemeijer M; Potdevin S; Roussignol G; Vaganov A; Barbaric I; Barrow M; Burton NC; Connell J; Dazzi F; Edsbagge J; French NS; Holder J; Hutchinson C; Jones DR; Kalber T; Lovatt C; Lythgoe MF; Patel S; Patrick PS; Piner J; Reinhardt J; Ricci E; Sidaway J; Stacey GN; Starkey Lewis PJ; Sullivan G; Taylor A; Wilm B; Poptani H; Murray P; Goldring CEP; Park BK Preclinical imaging methods for assessing the safety and efficacy of regenerative medicine therapies. npj Regener. Med 2017, 2, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Huang D; Swanson EA; Lin CP; Schuman JS; Stinson WG; Chang W; Hee MR; Flotte T; Gregory K; Puliafito CA; Fujimoto JG Optical coherence tomography. Science 1991, 254, 1178–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Frangioni J In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2003, 7, 626–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Weissleder R; Kelly K; Sun EY; Shtatland T; Josephson L Cell-specific targeting of nanoparticles by multivalent attachment of small molecules. Nat. Biotechnol 2005, 23, 1418–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Blomley MJK; Cooke JC; Unger EC; Monaghan MJ; Cosgrove DO Science, medicine, and the future: Microbubble contrast agents: a new era in ultrasound. Br. Med. J 2001, 322, 1222–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Mulder WJM; Strijkers GJ; Habets JW; Bleeker EJW; Schaft DWJ; Storm G; Koning GA; Griffioen AW; Nicolay K MR molecular imaging and fluorescence microscopy for identification of activated tumor endothelium using a bimodal lipidic nanoparticle. Faseb. J 2005, 19, 2008–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Rao J; Dragulescu-Andrasi A; Yao H Fluorescence imaging in vivo: recent advances. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2007, 18, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Yang X; Stein EW; Ashkenazi S; Wang LV Nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol 2009, 1, 360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ricles LM; Nam SY; Treviño EA; Emelianov SY; Suggs LJ A Dual Gold Nanoparticle System for Mesenchymal Stem Cell Tracking. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 8220–8230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tucker-Schwartz JM; Hong T; Colvin DC; Xu Y; Skala MC Dual-modality photothermal optical coherence tomography and magnetic-resonance imaging of carbon nanotubes. Opt Lett. 2012, 37, 872–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Oldenburg AL; Toublan FJ-J; Suslick KS; Wei A; Boppart SA Magnetomotive contrast for in vivo optical coherence tomography. Opt Express 2005, 13, 6597–6614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kirillin MY; Sergeeva EA; Agrba PD; Krainov AD; Ezhov AA; Shuleiko DV; Kashkarov PK; Zabotnov SV Laser-ablated silicon nanoparticles: optical properties and perspectives in optical coherence tomography. Laser Phys. 2015, 25, 075604. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jain PK; Lee KS; El-Sayed IH; El-Sayed MA Calculated absorption and scattering properties of gold nanoparticles of different size, shape, and composition: applications in biological imaging and biomedicine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 7238–7248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Link S; Mohamed MB; El-Sayed MA Simulation of the Optical Absorption Spectra of Gold Nanorods as a Function of Their Aspect Ratio and the Effect of the Medium Dielectric Constant. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 3073–3077. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Yguerabide J; Yguerabide EE Light-Scattering Submicroscopic Particles as Highly Fluorescent Analogs and Their Use as Tracer Labels in Clinical and Biological Applications: I. Theory. Anal. Biochem 1998, 262, 137–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Loo C; Lin A; Hirsch L; Lee M-H; Barton J; Halas N; West J; Drezek R Nanoshell-enabled photonics-based imaging and therapy of cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat 2004, 3, 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Si P; Yuan E; Liba O; Winetraub Y; Yousefi S; SoRelle ED; Yecies DW; Dutta R; de la Zerda A Gold Nanoprisms as Optical Coherence Tomography Contrast Agents in the Second Near-Infrared Window for Enhanced Angiography in Live Animals. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 11986–11994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Oldenburg A; Zweifel DA; Xu C; Wei A; Boppart SA Characterization of plasmon-resonant gold nanorods as near-infrared optical contrast agents investigated using a double-integrating sphere system. SPIE BiOS; SPIE, 2005; p 11. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Song HB; Wi J-S; Jo DH; Kim JH; Lee S-W; Lee TG; Kim JH Intraocular application of gold nanodisks optically tuned for optical coherence tomography: inhibitory effect on retinal neovascularization without unbearable toxicity. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med 2017, 13, 1901–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Agrawal A; Huang S; Wei Haw Lin A; Lee M-H; Barton JK; Drezek RA; Pfefer TJ Quantitative evaluation of optical coherence tomography signal enhancement with gold nanoshells. J. Biomed. Opt 2006, 11, 041121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Tkaczyk TS; Rahman M; Mack V; Sokolov K; Rogers JD; Richards-Kortum R; Descour MR High resolution, molecular-specific, reflectance imaging in optically dense tissue phantoms with structured-illumination. Opt. Express 2004, 12, 3745–3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Truffi M; Fiandra L; Sorrentino L; Monieri M; Corsi F; Mazzucchelli S Ferritin nanocages: A biological platform for drug delivery, imaging and theranostics in cancer. Pharmacol. Res 2016, 107, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Babič M; Horák D; Trchová M; Jendelová P; Glogarová K; Lesný P; Herynek V; Hájek M; Syková E Poly(l-lysine)-Modified Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Stem Cell Labeling. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 740–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Huang Y; Li M; Huang D; Qiu Q; Lin W; Liu J; Yang W; Yao Y; Yan G; Qu N; Tuchin VV; Fan S; Liu G; Zhao Q; Chen X Depth-Resolved Enhanced Spectral-Domain OCT Imaging of Live Mammalian Embryos Using Gold Nanoparticles as Contrast Agent. Small 2019, 15, 1902346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Mackiewicz MR; Hodges HL; Reed SM C-Reactive Protein Induced Rearrangement of Phosphatidylcholine on Nanoparticle Mimics of Lipoprotein Particles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 5556–5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Sitaula S; Mackiewicz MR; Reed SM Gold nanoparticles become stable to cyanide etch when coated with hybrid lipid bilayers. Chem. Commun 2008, 301–3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wang MS; Messersmith RE; Reed SM Membrane curvature recognition by C-reactive protein using lipoprotein mimics. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 7909–7918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Orendorff CJ; Murphy CJ Quantitation of Metal Content in the Silver-Assisted Growth of Gold Nanorods. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 3990–3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Engstrom AM; Faase RA; Marquart GW; Baio JE; Mackiewicz MR; Harper SL Size-Dependent Interactions of Lipid-Coated Gold Nanoparticles: Developing a Better Mechanistic Understanding Through Model Cell Membranes and in vivo Toxicity. Int. J. Nanomed 2020, 15, 4091–4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Engstrom AMW; Mackiewicz MR; Harper SL Controlling Silver Ion Release of Silver Nanoparticles with Hybrid Lipid Membranes with Long-Chain Hydrophobic Thiol Anchors Decreases in vivo Toxicity. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl 2020, 10, 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Miesen TJ; Engstrom AM; Frost DC; Ajjarapu R; Ajjarapu R; Lira CN; Mackiewicz MR A hybrid lipid membrane coating “shape-locks” silver nanoparticles to prevent surface oxidation and silver ion dissolution. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 15677–15693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Miesen TJE; Frost DC; Ajjarapu R; Ajjarapu R; Nieves Lira C; Mackiewicz MR A Hybrid Lipid Membrane Coating “Shape-Lock” Silver Nanoparticles to Prevent Surface Oxidation and Silver Ion Dissolution. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 15677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Cunningham B; Engstrom AM; Harper BJ; Harper SL; Mackiewicz MR Silver Nanoparticles Stable to Oxidation and Silver Ion Release Show Size-Dependent Toxicity In Vivo. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kim B-K; Hwang G-B; Seu Y-B; Choi J-S; Jin KS; Doh K-O DOTAP/DOPE ratio and cell type determine transfection efficiency with DOTAP-liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr 2015, 1848, 1996–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Qin C; Fei J; Wang A; Yang Y; Li J Rational assembly of a biointerfaced core@shell nanocomplex towards selective and highly efficient synergistic photothermal/photodynamic therapy. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 20197–20210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Xie X; Liao J; Shao X; Li Q; Lin Y The Effect of shape on Cellular Uptake of Gold Nanoparticles in the forms of Stars, Rods, and Triangles. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Chandran P; Riviere JE; Monteiro-Riviere NA Surface chemistry of gold nanoparticles determines the biocorona composition impacting cellular uptake, toxicity and gene expression profiles in human endothelial cells. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Mekseriwattana W; Srisuk S; Kriangsaksri R; Niamsiri N; Prapainop K The Impact of Serum Proteins and Surface Chemistry on Magnetic Nanoparticle Colloidal Stability and Cellular Uptake in Breast Cancer Cells. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Fröhlich E The role of surface charge in cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of medical nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed 2012, 7, 5577–5591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Xia Q; Huang J; Feng Q; Chen X; Liu X; Li X; Zhang T; Xiao S; Li H; Zhong Z; Xiao K Size- and cell type-dependent cellular uptake, cytotoxicity and in vivo distribution of gold nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed 2019, 14, 6957–6970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kettler K; Veltman K; van de Meent D; van Wezel A; Hendriks AJ Cellular uptake of nanoparticles as determined by particle properties, experimental conditions, and cell type. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 2014, 33, 481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Foroozandeh P; Aziz AA Insight into Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking of Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett 2018, 13, 339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).McGill TJ; Osborne L; Lu B; Stoddard J; Huhn S; Tsukamoto A; Capela A Subretinal Transplantation of Human Central Nervous System Stem Cells Stimulates Controlled Proliferation of Endogenous Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol 2019, 8, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Sheedlo HJ; Li L; Turner JE Photoreceptor cell rescue at early and late RPE-cell transplantation periods during retinal disease in RCS dystrophic rats. J. Neural Transplant. Plast 1991, 2, 55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Silverman MS; Hughes SE Photoreceptor rescue in the RCS rat without pigment epithelium transplantation. Curr. Eye Res 1990, 9, 18–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Arvizo RR; Miranda OR; Thompson MA; Pabelick CM; Bhattacharya R; Robertson JD; Rotello VM; Prakash YS; Mukherjee P Effect of nanoparticle surface charge at the plasma membrane and beyond. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2543–2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Wang S; Lu W; Tovmachenko O; Rai US; Yu H; Ray PC Challenge in understanding size and shape dependent toxicity of gold nanomaterials in human skin keratinocytes. Chem. Phys. Lett 2008, 463, 145–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Albanese A; Chan WCW Effect of Gold Nanoparticle Aggregation on Cell Uptake and Toxicity. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 5478–5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Durantie E; Vanhecke D; Rodriguez-Lorenzo L; Delhaes F; Balog S; Septiadi D; Bourquin J; Petri-Fink A; Rothen-Rutishauser B Biodistribution of single and aggregated gold nanoparticles exposed to the human lung epithelial tissue barrier at the air-liquid interface. Part. Fibre Toxicol 2017, 14, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Wu P-C; Chen C-Y; Chang C-W The fluorescence quenching and aggregation induced emission behaviour of silver nanoclusters labelled on poly(acrylic acid-co-maleic acid). New J. Chem 2018, 42, 3459–3464. [Google Scholar]

- (54).De S; Pal A; Jana NR; Pal T Anion effect in linear silver nanoparticle aggregation as evidenced by efficient fluorescence quenching and SERS enhancement. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2000, 131, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Chen W; Tu X; Guo X Fluorescent gold nanoparticles-based fluorescence sensor for Cu2+ ions. Chem. Commun 2009, 13, 1736–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Doorley GW; Payne CK Cellular binding of nanoparticles in the presence of serum proteins. Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 466–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Walkey CD; Olsen JB; Guo H; Emili A; Chan WCW Nanoparticle size and surface chemistry determine serum protein adsorption and macrophage uptake. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 2139–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Tedja R; Lim M; Amal R; Marquis C Effects of serum adsorption on cellular uptake profile and consequent impact of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on human lung cell lines. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 4083–4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Liu X; Chen Y; Li H; Huang N; Jin Q; Ren K; Ji J Enhanced Retention and Cellular Uptake of Nanoparticles in Tumors by Controlling Their Aggregation Behavior. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 6244–6257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Moore TL; Urban DA; Rodriguez-Lorenzo L; Milosevic A; Crippa F; Spuch-Calvar M; Balog S; Rothen-Rutishauser B; Lattuada M; Petri-Fink A Nanoparticle administration method in cell culture alters particle-cell interaction. Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Fleischer CC; Payne CK Secondary structure of corona proteins determines the cell surface receptors used by nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 14017–14026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Wang F; Yu L; Monopoli MP; Sandin P; Mahon E; Salvati A; Dawson KA The biomolecular corona is retained during nanoparticle uptake and protects the cells from the damage induced by cationic nanoparticles until degraded in the lysosomes. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med 2013, 9, 1159–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Zhu Z-J; Posati T; Moyano DF; Tang R; Yan B; Vachet RW; Rotello VM The interplay of monolayer structure and serum protein interactions on the cellular uptake of gold nanoparticles. Small 2012, 8, 2659–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data