Abstract

The endocannabinoid signaling system is comprised of CB1 and CB2 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). CB2 receptor subtype is predominantly expressed in the immune cells and signals through its transducer proteins (Gi protein and β-arrestin-2). Arrestins are signaling proteins that bind to many GPCRs after receptor phosphorylation to terminate G protein signaling (desensitization) and to initiate specific G protein-independent arrestin-mediated signaling pathways via a “phosphorylation barcode”, that captures sequence patterns of phosphorylated Ser/Thr residues in the receptor’s intracellular domains and can lead to different signaling effects. The structural basis for how arrestins and G proteins compete with the receptor for biased signaling and how different barcodes lead to different signaling profiles is not well understood as there is a lack of phosphorylated receptor structures in complex with arrestins. In this work, structural models of β-arrestin-2 were built in complex with the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of the CB2 receptor. The complex structures were relaxed in the lipid bilayer environment with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and analyzed structurally and thermodynamically. The β-arrestin-2 complex with the phosphorylated receptor was more stable than the non-phosphorylated one, highlighting the thermodynamic role of the receptor phosphorylation. It was also more stable than any of the G protein complexes with CB2 suggesting that phosphorylation signals receptor desensitization (end of G protein signaling) and arrest of the receptor by arrestins. These models are beginning to provide the thermodynamic landscape of CB2 signaling, which can help bias signaling towards therapeutically beneficial pathways in drug discovery applications.

Keywords: GPCRs, Molecular dynamics, Signaling complexes, Endocannabinoid system, Phosphopeptide

1. Introduction

The Endocannabinoid system (ECS) is a complex physiological signaling system that controls many critical functions such as mood, learning and memory, pain control, and emotional processing [1]. The ECS signaling is mediated by cannabinoid G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) CB1, CB2, and putative cannabinoid receptors (GPR55, GPR18, GPR119) [2,3] activated by endocannabinoid ligands like Anandamide (AEA, arachidonoylethanolamide) and 2-arachidonoylglyerol (2-AG) and that are also activated by marijuana cannabinoids like Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) [4].

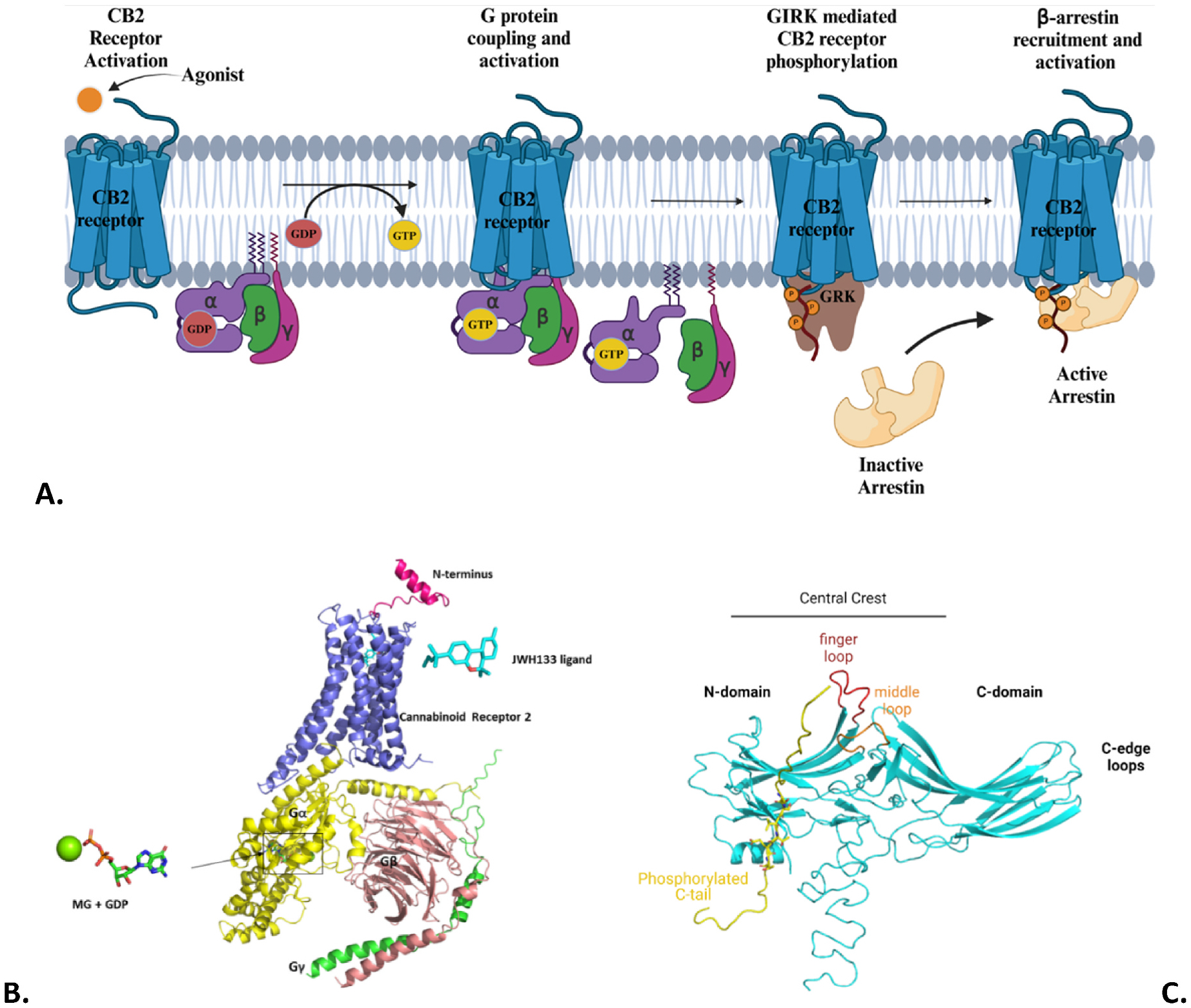

CB1 receptor is expressed predominantly in the central nervous system (CNS) and CB2 receptor is primarily expressed in the immune system without CB1’s psychoactive effects [5]. These receptors mainly signal through Gi/o proteins (Fig. 1A), where the α5 helix of GDP-bound Gαi subunit engages with the receptor’s intracellular-facing TM pocket (Fig. 1B) also called the G protein coupling site as this coupling site is utilized by all receptor G protein complexes observed so far. The agonist-induced receptor activation causes a GDP/GTP exchange in the Gi/o protein resulting in its dissociation (Fig. 1A), such that the GTP-bound Gαi/o subunit inhibits Adenylyl cyclase (AC) and lowers cAMP levels while the Gβγ subunit recruits G protein receptor kinases (GRKs) that phosphorylate the receptor at multiple specific Ser/Thr locations in its C-terminus and/or intracellular loops. The sequence motif of phosphorylated Ser/Thr residues in a receptor is referred to as the “phosphorylation barcode” [6]. The phosphorylated receptor binds to arrestin proteins (Fig. 1A) signifying the end of G protein signaling (called receptor desensitization) that results in receptor internalization into endosomes followed by receptor’s endosomal signaling or recycling or lysosomal degradation [7]. CB1 and CB2 receptors engage with β-arrestin-1/−2 [8,9], which trigger their own signaling cascades and when balanced with Gi/o-dependent signaling pathways can provide a dynamic range to cannabinoid signaling from Gi/o-biased to arrestin-biased to everything in-between [8].

Fig. 1.

A. GPCR mediated G-protein-dependent signaling and G-protein-independent (β-arrestin) signaling complexes; B. Structure of CB2:Gi-GDP protein complex based on PDB 6KPF; C. PDB structure 6TKO of β-arrestin-1 (Blue) interacting with a phosphorylated peptide (Yellow).

A mechanistic basis for this dynamic range of biased signaling is lacking for cannabinoid receptors and GPCRs in general but advances in membrane protein crystallography [10] and cryo-EM [11] have begun to provide snapshots of receptors bound to different transducers (G proteins or arrestins) that can be used to map the energy landscape and mechanisms underlying biased signaling. This understanding will lay the groundwork for a rational design of biased drugs with minimal side-effects as drug candidates with balanced signaling have been shown to cause on-target side-effects [12]. The structure of arrestins consists of two lobes: the N-domain and the C-domain (Fig. 1C). Each of these lobes form a β-sandwich fold (like in Immunoglobulins) that are connected by a hinge region. The N-domain and C-domain lobes meet at a central crest region made up of some loop regions (like finger loop, middle loop, Fig. 1C). The finger loop region of arrestins interacts with the receptor’s transmembrane (TM) domain in the G protein coupling site, so arrestin binding to the receptor can directly compete with the G protein. In addition, the N-domain of β-arrestins interacts with the phosphorylated carboxyl terminus site or PhosphoC site of the receptor that is not utilized by the G protein [6]. So, the “phosphorylation barcode” is expected to play an important role in biased signaling profiles [13].

A structural understanding of CB2 receptor’s biased signaling will need receptor complexes with GDP-bound Gi protein (not yet available), with nucleotide-free Gi protein (available), and with β-arrestin-2 engaging the receptor through both the G protein coupling site and the PhosphoC site (not yet available). Supplementary Table S1 and Table S2 have a summary of available complex structures for CB1 and CB2.

So, in this study, we first generated the complexes of the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated CB2 receptor with β-arrestin-2 and of the unphosphorylated CB2 receptor with GDP-bound G protein. The arrestin-bound complexes required a new structural bioinformatics-based structure building protocol as described in the methods section. The complexes were relaxed in the lipid-bilayer environment through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and assessed using two mutants of the CB2 receptor (Q6312.49R and L1333.52I, superscripts are Ballesteros-Weinstein (BW) numbers [14]) with different abilities to recruit β-arrestin-2 but with no differences in Gi protein coupling or ligand binding [15]. A thermodynamic comparison of these signaling complexes has provided a starting energy landscape of CB2 receptor activation, the role of the phosphorylation barcode, and how arrestin recruitment signals the end of G protein signaling from the plasma membrane or receptor desensitization. Such energy landscapes are needed for different GPCRs to understand the diversity of mechanisms at play in receptor-mediated biased signaling.

2. Methods

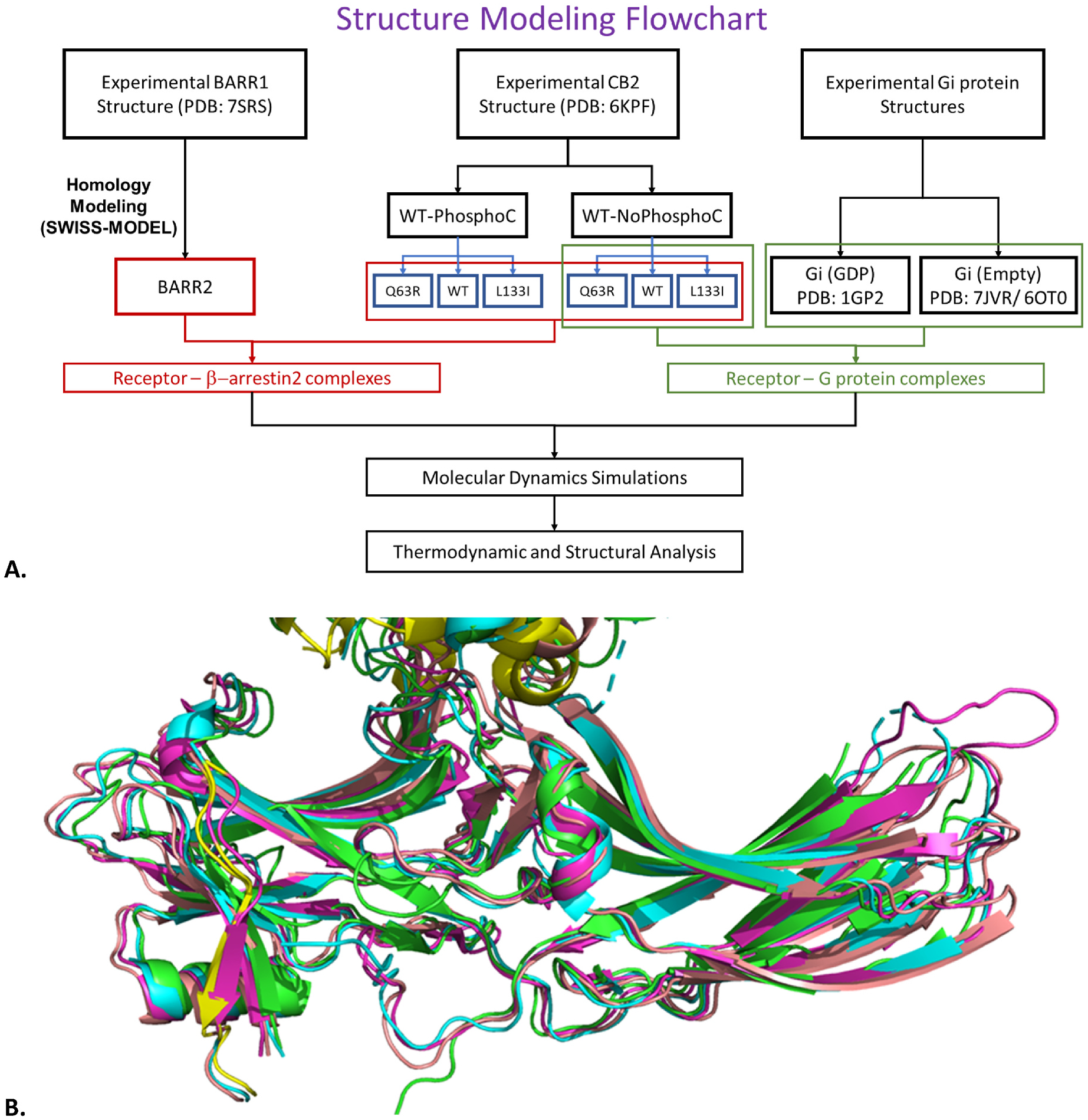

This study utilized structural bioinformatics and homology-based modeling to build the complexes of the CB2 receptor with β-arrestin-2 and Gi-protein, followed by biophysical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MMPBSA) based free-energy analysis of transducer (Gi protein or β-arrestin-2) binding to the receptor to characterize those complexes structurally and thermodynamically. The overall structure modeling and simulation/analysis workflow is shown in Fig. 2A. The individual steps are described below along with their rationale and the detailed protocol followed for each step is described in the supplementary Section S4.

Fig. 2.

A. The structure building and simulation protocol; B. Alignment of available β-arrestin-1 structures in complex with receptors; PDB: 7R0C (cyan), 6TKO (green/yellow), 6U1N (pink), 7SRS (salmon).

Step 2.1 CB2 receptor structures: Wild-Type and Mutant Receptors without Phosphorylated C-terminus tail (NoPhosphoC)

The 6KPF PDB structure of CB2 was missing the extracellular N-terminus (Nterm), the intracellular loop 3 (ICL3), and the intracellular C-terminus tail (Ctail) (Supplementary Fig. S1, also see Table S3 for CB2 domain residues and BW TM anchor n.50 residues). The AlphaFold2 (AF2) [16] structure of CB2 receptor (Uniprot: P34972) was used to fill the missing regions as described in Section S4, except for the Ctail for the following reasons: a) This domain is usually unstructured when the receptor binds to G protein and has been shown to mainly slow down the association of the receptor with the G-protein [17]; b) This domain will be built carefully later when the receptor is modeled with β-arrestin-2, as then it is structured in its phosphorylated form and expected to play an important role in β-arrestin-2 recruitment. The mutant receptors (Q6312.49R and L1333.52I) were generated from the wild-type (WT) using PyMOL’s mutagenesis wizard. The 6KPF PDB used as a template for CB2 was bound to ligand AM12033. The biochemical studies on wild-type and mutant CB2 receptors were done with another agonist JWH133 [15]. The two ligands (AM12033 and JWH133) share a structural scaffold (Supplementary Fig. S2), so it was reasonable to assume that the shared scaffold would be oriented the same way in the CB2 receptor’s orthosteric site. The Ligand Reader and Modeller module [18] of CHARMM-GUI [19] was used to convert AM12033 into JWH133 while preserving the atomic coordinates of the shared scaffold.

Step 2.2 β-arrestin-2 structure

There is no β-arrestin-2 structure bound to the G protein coupling site in a receptor. Supplementary Table S4 summarizes the available β-arrestin-1 PDB structures in complex with any receptor. A structure-based alignment of CB2 from 6KPF to the receptors in these β-arrestin-1 complexes (Fig. 2B) showed that the α-helical finger loop conformation of arrestin in complex with 5-HT2B receptor (PDB: 7SRS) maximizes interaction with CB2’s G protein coupling site. So, a structural model for β-arrestin-2 was built using 7SRS chain D (β-arrestin-1) on the SWISS-MODEL server [20] and missing residues added by MODELLER (see Section S4).

Step 2.3 GDP-bound and nucleotide-free Gi protein structures (Gi-GDP and Gi-Empty)

The full-length Gi protein models were taken from our G protein models collection called GandalphMD, where the GDP-bound model used PDB 1GP2 as a template and the Gi-Empty model used PDB 7JVR and 6OT0 as templates. The latter will be morphed in step 2.5 below into the Gi-Empty protein present in CB2’s 6KPF complex by replacing its own Gαi’s last 19 residues with the 6KPF Gαi’s last 19 residues as those provide the most accurate G protein coupling site interaction surface for the CB2 receptor.

Step 2.4 Building CB2:β-arrestin-2 complexes

Step 2.4.1 Receptor without phosphorylated C-terminus (CB2-NoPhosphoC:β-arrestin-2)

The CB2 model without phosphorylated Ctail (step 2.1) and β-arrestin-2 model (step 2.2) were aligned to the PDB 7SRS to capture the receptor-arrestin interface at the G protein coupling site and sidechains optimized using SCWRL4 [23].

Step 2.4.2 Receptor with phosphorylated C-terminus (CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2)

First, CB2 receptor’s phosphorylation barcode was identified by using the PhosphoSitePlus server [21], as Ser335, Ser336, Thr338, and Thr340, abbreviated as SSxTxT, where “x” can be a variable residue. This barcode motif sequence was aligned to all arrestin structures in Supplementary Table S4 that had the receptor G protein coupling site as well as the phosphopeptide (PhosphoC site) resolved structurally. The PDBs 6TKO and 6U1N were both equally viable templates as they both had the highest number of conserved charged residues (Table S4) interacting with Ser/Thr in the PhosphoC site. The PDB 6TKO was chosen as a template:

The N-domain of β-arrestin-1 structure in PDB 6TKO was aligned to the N-domain of β-arrestin-2 structure in the CB2-NoPhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 complex (from step 2.4.1), the 6TKO phosphopeptide TTxSSS was copied over to the complex and mutated to corresponding CB2 sequence using PyMOL. The Modeller program inside PyMOD module of PyMOL was then used to fill the CB2 residues between its helix8 and its PhosphoC site. These steps are further detailed in Section S4.

Step 2.5 Building CB2:Gi-protein complexes

The CB2 complex with Gi-Empty is built by aligning the CB2 receptor model from step 2.1 and the RAS domain of the Gi-Empty structure from step 2.3 to 6KPF. To capture the G protein coupling site accurately, the last 19 residues from 6KPF’s Gαi (F336G.H5.8- F354G.H5.26) are kept in the final complex in place of the corresponding residues from the Gi-Empty structure from step 2.3. The CB2 complex with Gi-GDP is built by aligning the CB2 receptor model from step 2.1 and the RAS domain of the Gi-GDP structure from step 2.3 to 6KPF. The Gi-GDP α5 helix from Gαi subunit was completely straight, which could cause steric clashes with the receptor, so the α5 helix was dragged downwards minimally.

Step 2.6 MD Simulations, thermodynamics analysis and structural analysis

The two CB2 receptor complexes with β-arrestin-2 (with and without receptor PhosphoC) and two CB2 receptor complexes with Gi protein (Gi-GDP and Gi-Empty) were embedded into the lipid bilayer environment using CHARMM-GUI server [19] and relaxed for 2 μs using the MD protocol that has been described previously [22]. The MMPBSA method was used for thermodynamics analysis of the complexes as described previously [22] to capture the free-energy of receptor:transducer binding interaction in each of the complexes. The receptor:transducer contact analysis that provides interacting residue pairs was done with the CPPTRAJ module of AMBER. The residue-residue distance analysis, RMSD, and RMSF analysis were done with VMD. All these analyses are detailed in Section S4.

3. Results and discussion

In this study, explicit lipid-bilayer MD simulations were performed for the four models, CB2-β-PhosphoC: β-arrestin-2, CB2-NoPhosphoC:β-arrestin-2, CB2-NoPhosphoC:Gi-GDP, and CB2-NoPhosphoC:Gi-Empty for the wild-type and mutant CB2 (Q6312.49R and L1333.52I) with four MD replica runs for each complex, totaling 48 MD simulations to relax the complexes in their physiological environments (Supplementary Table S5). The resulting ensembles of conformations for each complex then enabled a detailed thermodynamic and structural analysis to map the energy landscape of G protein and β-arrestin-2 coupling to CB2 that leads to receptor desensitization, as the CB2-NoPhosphoC:Gi-GDP, CB2-NoPhosphoC:Gi-Empty, CB2-NoPhosphoC:β-arrestin-2, and CB2-PhosphoC: β-arrestin-2 models all represent distinct sequential stages of the CB2 signaling landscape.

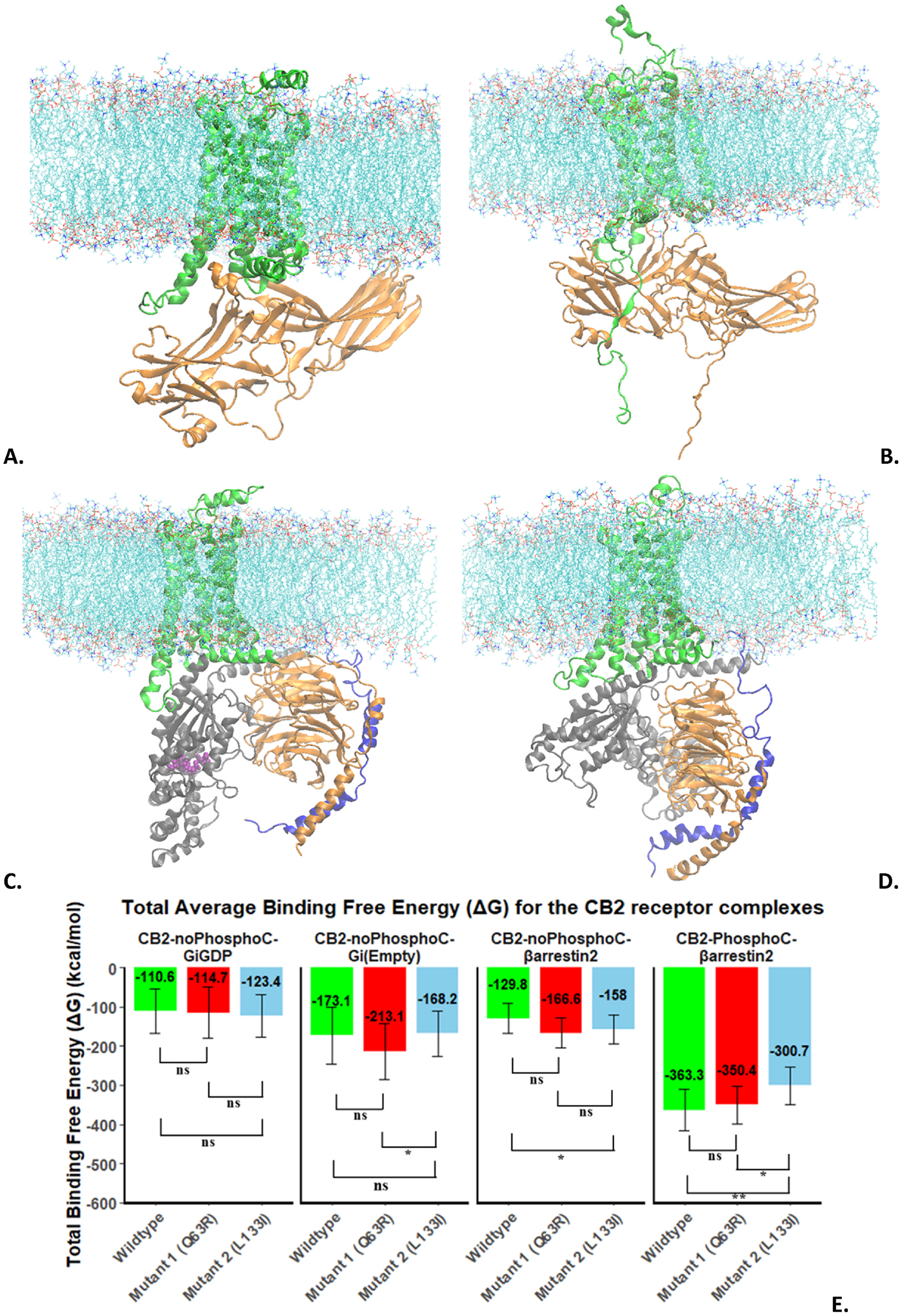

3.1. Structures of CB2:β-arrestin-2 complexes and CB2:G protein complexes

The average snapshots of the lipid-embedded CB2-NoPhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 and CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 complexes are shown in Fig.3A and B respectively. The root-mean-squared-deviation (RMSD) analysis of these complexes (Supplementary Fig. S3), which captures the conformational distance sampled during the simulation relative to the starting structure, shows that both complexes are stabilized in all 4 replicas. The complex with the PhosphoC site (Fig.S3B) is more dynamic than the one (Fig.S3A) that is without that site and also deviates the most from the starting structure (higher average RMSD in the second half of the simulation). This is not unexpected as there is no ideal template for the arrestin complex with both a PhosphoC site and a G protein coupling site, so simulation is expected to relax it further away from the starting structure.

Fig. 3.

A. CB2-NoPhosphoC:β-arrestin-2; B. CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2; C. CB2-NoPhosphoC:Gi-GDP; D. CB2-NoPhosphoC:Gi-Empty; E. MMPBSA-based free-energy of binding of transducer (G protein/β-arrestin-2) for CB2.

The average snapshots of the lipid-embedded CB2-NoPhosphoC:Gi-GDP and CB2-PhosphoC:Gi-Empty complexes are shown in Fig.3C and D respectively. The root-mean-squared-deviation (RMSD) analysis of these complexes (Supplementary Fig. S4), shows that both complexes are stabilized in majority of replicas. The complex with Gi-GDP (Fig.S4A) is more dynamic than the one with Gi-Empty (Fig.S4B), where the latter also deviates more from the starting structure. The Gi-GDP complex with CB2 being dynamic is expected as this encounter complex needs to undergo large conformational changes for GDP release.

3.2. Thermodynamic analysis (MMPBSA)

MMPBSA based thermodynamic analysis of the four complexes for the wild-type and two mutant receptors are shown in Fig. 3E. More negative numbers mean more stable complexes. The phosphorylated complex shows the strongest affinity (−363.3 kcal/mol) between CB2 and β-arrestin-2. The next strongest affinity for a transducer is for the Gi-Empty protein with CB2 (−173.1 kcal/mol) followed by CB2-noPhosphoC-β-arrestin-2 (−129.8 kcal/mol) and CB2-noPhosphoC:Gi-GDP (−110.6 kcal/mol). The difference between last two cases is not significant. The very strong affinity of β-arrestin-2 for the phosphorylated receptor compared to all other cases demonstrates one of the known functions of arrestin, which is to arrest the receptor (CB2 in this case) from the G protein (Gi in this case) and lead to receptor desensitization (end of G protein signaling). This observation also shows the functional importance of the phosphorylation that is necessary for many receptors to enable a successful recruitment of arrestin and a thermodynamic role of phosphorylation in arrestin coupling.

Comparing the free-energy of transducer binding of the mutants to the wild-type, we can see that mutant2 (L1333.52I) binds significantly weaker than the wild-type for the phosphorylated case. The mutant1 (Q6312.49R) is not significantly different from wild-type. This observation is consistent with the biochemical assays [15], that showed that the mutant2 (L1333.52I) was weak in recruiting arrestin and mutant1 (Q6312.49R) was only slightly better than wild-type. In the unphosphorylated case of interaction with arrestin, the mutant2 binds stronger to arrestin relative to the wild-type, which is not consistent with the biochemical assays and shows that phosphorylation is needed for arrestin recruitment. The thermodynamic data for Gi-GDP complexes shows no significant difference between wild-type and mutants for the Gi-GDP case, which is also consistent with the biochemical assays [15]. In the case of Gi-Empty complexes, mutant1 (Q6312.49R) binds stronger to Gi protein than mutant2 (L1333.52I). This is not consistent with the biochemical assays and points to the fact that the Gi-Empty complex state is an artificial state that has a very short lifetime in a cell due to high GTP concentration, so any experimental observations of G protein binding are expected to correlate better with GDP-bound G proteins that are responsible for initial engagement with the receptors.

3.2.1. Receptor-ligand binding affinity for CB2 complexes with β-arrestin-2 and Gi protein

MMPBSA method was also used to measure the binding affinity between CB2 and JWH133 ligand to measure how strongly the receptor and ligand interact with each other for wild-type and mutant receptors. The results are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. The ligand binding affinity is similar for the mutants compared to the wild-type for the CB2-NoPhosphoC:Gi-GDP case and the CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 cases, consistent with biochemical assays [15].

3.3. Structural analysis

3.3.1. Contact analysis of receptor-PhosphoC:βarrestin-2 for wild-type and mutants

The three CB2-PhosphoC:βarrestin-2 complexes for the wild-type and two mutants were analyzed using a distance cutoff of 4.5 Å to identify stable interactions between CB2 and β-arrestin-2. These interactions are summarized in Supplementary Table S6. The Total-Fraction column tells us how often the specific interactions occurred within the distance of 4.5 Å. If the TotalFraction for an interacting residue pair is greater than one, this means that these residues were in contact in every single frame. The sum of the TotalFraction for all interacting residue-residue pairs was calculated for wild-type, mutant 1 (Q6312.49R) and mutant2 (L1333.52I). This number was 1257 contacts for mutant2 (L1333.52I) much less than that for wild-type and mutant 1 (Q6312.49R), whose numbers were 1495 and 1499 respectively. This is consistent with mutant2 displaying weakest binding to arrestin [15]. The contacts that were conserved in all three CB2 forms [WT, mutant1 (Q6312.49R), mutant2 (L1333.52I)] are: p-S336Cter-K12, p-T340Cter-R8, V337Cter-K11, E339Cter-V9, E339Cter-K11. The distances of two of these contacts p-S336Cter-K12 and E339Cter-K11 are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6 combining all 4 replicas’ data. The p-S336Cter-K12 distance (Fig.S6A) remains low throughout the simulation at a distance range close to 5 Å indicating high stability for all three, except for mutant2 (L1333.52I) that shows transient fluctuations before stabilization. The distance between Glu339Cter-K11 remains overall quite stable (Fig.S6.B) across all the complexes maintaining a close distance range between 5 and 7 Å with the mutant1 (Q6312.49R) showing more fluctuations. The Supplementary Fig. S7 includes three different contacts that are shared between two out of three CB2 forms. S336Cter-R26 contact that is shared between the wild-type and mutant1 (Q6312.49R) remains very stable (Fig.S7A). The contact p-S335Cter-K295 common between wild-type and mutant 2 (L1333.52I) is more unstable in mutant2 (Fig.S7.B). The contact Trp349(Cter)-R104 shared between mutant1 (Q6312.49R) and mutant2 (L1333.52I) is more stable for mutant1 and very unstable for mutant2 (Fig.S7.C). These results highlight that single-point mutations can alter receptor:transducer interaction interfaces in different ways that will all contribute to observed binding affinities and can result in differently biased signaling.

3.3.2. Dynamics of arrestin in CB2:Arrestin complexes

β-arrestin-2 is recruited to prevent further G protein signaling via receptor desensitization, so it is useful to explore its dynamics using root-mean-square-fluctuation (RMSF), a per-residue measure that captures residue flexibility over the whole simulation time. This data is presented in Supplementary Fig. S8. For the β-arrestin-2 flexibility in wild-type and mutant 1 (Q6312.49R), the N-domain fluctuates less in mutant1 compared to WT. There is an increase in RMSF for the C-domain of β-arrestin-2 for both WT and mutant1 (Fig.S8A and Fig.S8.B). The N-terminal domain shows lower flexibility than the C-domain as it interacts with receptor’s PhosphoC site. For the β-arrestin-2 flexibility for mutant 2 (L133I), the N-domain and the middle loop have lower fluctuations across all the MD replica runs, indicating that the N-domain (N-terminal domain) and the middle loop are relatively stable (Fig.S8.C). The C-domain flexibility shows a distinct flexibility pattern in the wildtype and mutant1, almost like a breathing motion (alternating dynamic sequence motifs interspersed with less dynamic regions), which is not present in mutant2. This might be a signature of effective arrestin recruitment, as mutant2 shows weaker arrestin recruitment in biochemical assays [15], although this remains to be seen.

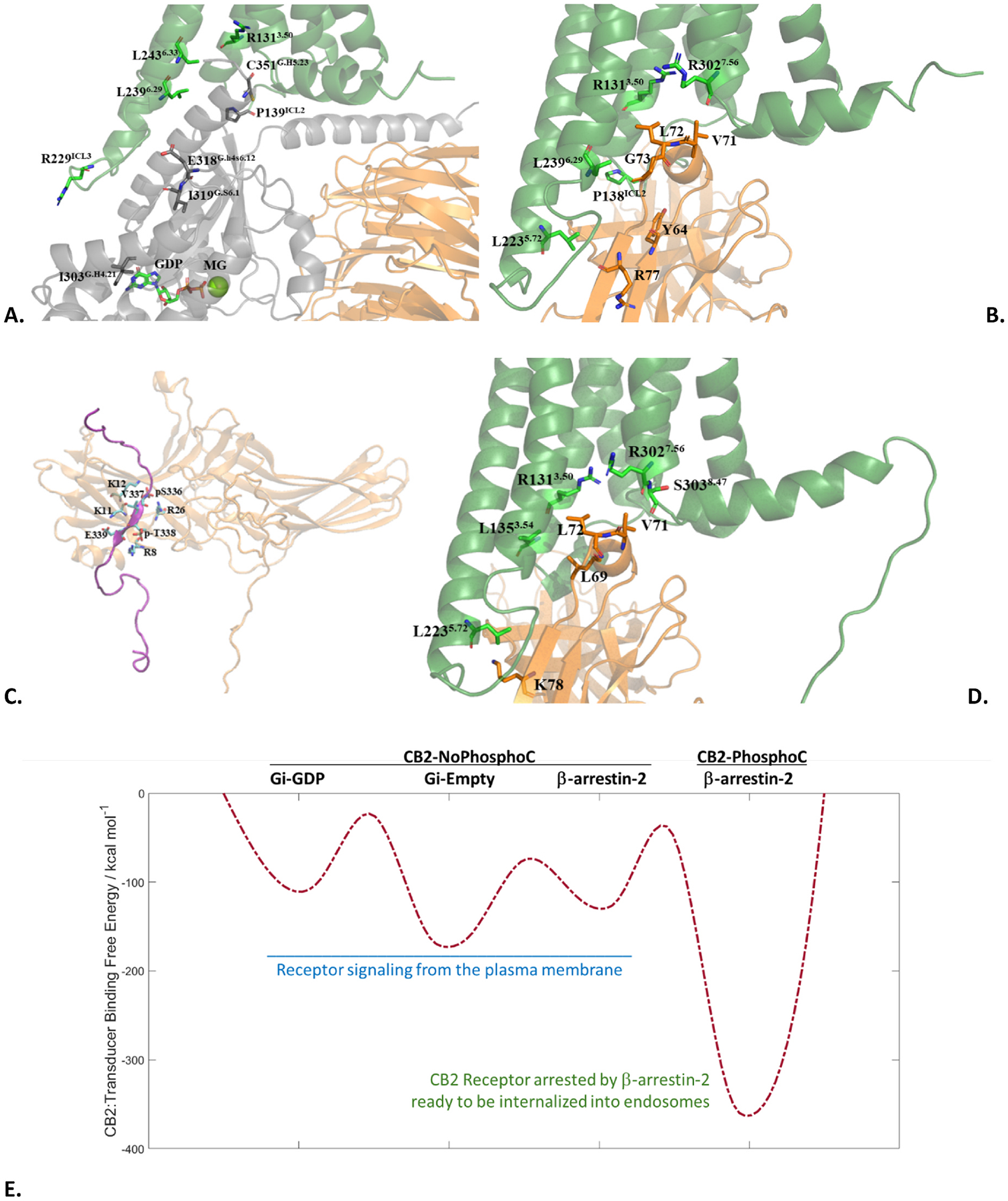

3.4. Structural and energy landscape of CB2 signaling

The average structures of CB2-NoPhosphoC:GiGDP, CB2-NoPhospoC:β-arrestin-2, and CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 were analyzed and compared to each other for the nature of the interface residues. These structures are shown in Fig. 4A through 4D. The first two complexes (Fig.4A and B) engage with the transducer (Gi protein or β-arrestin-2) only through the G protein coupling site. The interactions across this interface are predominantly hydrophobic. The third complex engages with β-arrestin-2 through both the PhosphoC site (Fig. 4C) and the G protein coupling site (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Average snapshots of the A. CB2-NoPhosphoC:Gi-GDP complex; B. CB2-NoPhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 complex; C. PhosphoC site interface of the CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 complex; D. G protein coupling site interface of the CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 complex. E. CB2:Transducer Binding Free-Energy Landscape of CB2 signaling. The connections between states and barriers are qualitative, hence shown with dashes.

The interactions at the G protein coupling site are again predominantly hydrophobic but those at the PhosphoC site are predominantly hydrophilic as they engage the receptor’s phosphorylation barcode. This is expected to be a general feature of GPCR:transducer couplings as all observed G protein coupling sites are predominantly hydrophobic and arrestin recruitment depends on receptor phosphorylation (addition of highly hydrophilic phosphate groups) in most cases. A free-energy landscape of CB2 signaling is presented in Fig. 4E with qualitative barriers between well-defined functional states that correspond to their potential energy wells based on previously presented thermodynamic data (Fig. 3E). The rightmost potential well corresponding to CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 is deep enough to create a kinetic barrier in the reverse direction that once the receptor is arrested, it cannot go back to G protein coupling. It also shows that in the absence of phosphorylation, arrestin cannot outcompete G protein coupling. The transitions between these states are hard to observe currently due to it being computationally prohibitive, however, this energy landscape provides a good starting framework to think about receptor signaling, dependence of successful arrestin recruitment on receptor phosphorylation, and the arrest of the receptor by arrestins (desensitization) that initiates receptor internalization into endosomes. This receptor-signaling landscape will look different for different ligands and cellular contexts providing unprecedented insight into receptor pharmacology, which can help characterize G protein biased signaling vs arrestin biased signaling vs balanced signaling. The corresponding structures/conformations can then provide a rational basis for drug design targeting only the subset of therapeutically-beneficial signaling pathways inside the cell to minimize on-target side-effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported in parts by two NIH grants (SC2GM130480 and R16GM153621) to RA. We thank Caesar Tawfeeq for providing the Gi protein structures and for helpful discussions. RA also thanks Debra Kendall for insightful discussions.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Eun Ha Heo: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Ravinder Abrol: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Ravinder Abrol reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. Ravinder Abrol reports a relationship with Phyteau Inc. that includes: equity or stocks. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.151100.

Data availability

The PDB structures of the complexes for the starting conformations and average structures from the trajectories are available from the Zenodo database under the DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14227796. The MD trajectory for CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 complex is available at GPCRmd resource [24], under entry 2091. The trajectories for other simulations will be available upon request.

References

- [1].Lu H-C, MacKie K, An introduction to the endogenous cannabinoid system, Biol. Psychiatr 79 (2016) 516–525, 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brown AJ, Novel cannabinoid receptors, Br. J. Pharmacol 152 (2007) 567–575, 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Irving A, Abdulrazzaq G, Chan SLF, Penman J, Harvey J, Alexander SPH, Chapter seven - cannabinoid receptor-related orphan G protein-coupled receptors, in: Kendall D, Alexander SPH (Eds.), Adv. Pharmacol, Academic Press, 2017, pp. 223–247, 10.1016/bs.apha.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lowe H, Toyang N, Steele B, Bryant J, Ngwa W, The endocannabinoid system: a potential target for the treatment of various diseases, Int. J. Mol. Sci 22 (2021), 10.3390/ijms22179472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li X, Hua T, Vemuri K, Ho JH, Wu Y, Wu L, Popov P, Benchama O, Zvonok N, Locke K, Qu L, Han GW, Iyer MR, Cinar R, Coffey NJ, Wang J, Wu M, Katritch V, Zhao S, Kunos G, Bohn LM, Makriyannis A, Stevens RC, Liu ZJ, Crystal structure of the human cannabinoid receptor CB2, Cell 176 (2019) 459–467.e13, 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kim K, Chung KY, Many faces of the GPCR-arrestin interaction, Arch Pharm. Res. (Seoul) 43 (2020) 890–899, 10.1007/s12272-020-01263-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marchese A, Paing MM, Temple BRS, Trejo J, G protein–coupled receptor sorting to endosomes and lysosomes, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 48 (2008) 601–629, 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ibsen MS, Connor M, Glass M, Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptor signaling and bias, Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2 (2017) 48–60, 10.1089/can.2016.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ibsen MS, Finlay DB, Patel M, Javitch JA, Glass M, Grimsey NL, Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptor-mediated arrestin translocation: species, subtype, and agonist-dependence, Front. Pharmacol 10 (2019), 10.3389/fphar.2019.00350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Blois TM, Bowie JU, G-protein-coupled receptor structures were not built in a day, Protein Sci 18 (2009) 1335–1342, 10.1002/pro.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ishchenko A, Gati C, Cherezov V, Structural biology of G protein-coupled receptors: new opportunities from XFELs and cryoEM, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 51 (2018) 44–52, 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Smith JS, Lefkowitz RJ, Rajagopal S, Biased signalling: from simple switches to allosteric microprocessors, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 17 (2018) 243–260, 10.1038/nrd.2017.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nobles KN, Xiao K, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lam CM, Rajagopal S, Strachan RT, Huang T-Y, Bressler EA, Hara MR, Shenoy SK, Gygi SP, Lefkowitz RJ, Distinct phosphorylation sites on the β2-adrenergic receptor establish a barcode that encodes differential functions of β-arrestin, Sci. Signal 4 (2011), 10.1126/scisignal.2001707 ra51–ra51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H, Integrated methods for the construction of threedimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors, Methods Neurosci 25 (1995) 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Turu G, Soltész-Katona E, Tóth AD, Juhász C, Cserző M, Misák Á, Balla Á, Caron MG, Hunyady L, Biased coupling to β-arrestin of two common variants of the CB2 cannabinoid receptor, Front. Endocrinol 12 (2021), 10.3389/fendo.2021.714561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Žídek A, Potapenko A, Bridgland A, Meyer C, Kohl SAA, Ballard AJ, Cowie A, Romera-Paredes B, Nikolov S, Jain R, Adler J, Back T, Petersen S, Reiman D, Clancy E, Zielinski M, Steinegger M, Pacholska M, Berghammer T, Bodenstein S, Silver D, Vinyals O, Senior AW, Kavukcuoglu K, Kohli P, Hassabis D, Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold, Nature 596 (2021) 583–589, 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Heng J, Hu Y, Pérez-Hernández G, Inoue A, Zhao J, Ma X, Sun X, Kawakami K, Ikuta T, Ding J, Yang Y, Zhang L, Peng S, Niu X, Li H, Guixà-González R, Jin C, Hildebrand PW, Chen C, Kobilka BK, Function and dynamics of the intrinsically disordered carboxyl terminus of β2 adrenergic receptor, Nat. Commun 14 (2023) 2005, 10.1038/s41467-023-37233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kim S, Lee J, Jo S, Brooks CL, Lee HS, Im W, CHARMM-GUI ligand reader and modeler for CHARMM force field generation of small molecules, J. Comput. Chem 38 (2017) 1879–1886, 10.1002/jcc.24829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W, CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM, J. Comput. Chem 29 (2008) 1859–1865, 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T, The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling, Bioinformatics 22 (2006) 195–201, 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hornbeck PV, Zhang B, Murray B, Kornhauser JM, Latham V, Skrzypek E, PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations, Nucleic Acids Res 43 (2015) D512–D520, 10.1093/nar/gku1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Understanding G Protein Selectivity of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors Using Computational Methods, (n.d.). https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/21/5290 (accessed November 16, 2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [23].Krivov GG, Shapovalov MV, Dunbrack RL, Improved prediction of protein sidechain conformations with SCWRL4, Proteins 77 (2009) 778–795, 10.1002/prot.22488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rodríguez-Espigares I, Torrens-Fontanals M, Tiemann JKS, et al. , GPCRmd uncovers the dynamics of the 3D-GPCRome, Nat. Methods 17 (8) (2020) 777–787, 10.1038/s41592-020-0884-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The PDB structures of the complexes for the starting conformations and average structures from the trajectories are available from the Zenodo database under the DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14227796. The MD trajectory for CB2-PhosphoC:β-arrestin-2 complex is available at GPCRmd resource [24], under entry 2091. The trajectories for other simulations will be available upon request.