Abstract

Early embryonic arrest (EEA) is a critical impediment in assisted reproductive technology (ART), affecting 40% of infertile patients by halting the development of early embryos from the zygote to blastocyst stage, resulting in a lack of viable embryos for successful pregnancy. Despite its prevalence, the molecular mechanism underlying EEA remains elusive. This review synthesizes the latest research on the genetic and molecular factors contributing to EEA, with a focus on maternal, paternal, and embryonic factors. Maternal factors such as irregularities in follicular development and endometrial environment, along with mutations in genes like NLRP5, PADI6, KPNA7, IGF2, and TUBB8, have been implicated in EEA. Specifically, PATL2 mutations are hypothesized to disrupt the maternal-zygotic transition, impairing embryo development. Paternal contributions to EEA are linked to chromosomal variations, epigenetic modifications, and mutations in genes such as CFAP69, ACTL7A, and M1AP, which interfere with sperm development and lead to infertility. Aneuploidy may disrupt spindle assembly checkpoints and pathways including Wnt, MAPK, and Hippo signaling, thereby contributing to EEA. Additionally, key genes involved in embryonic genome activation—such as ZSCAN4, DUXB, DUXA, NANOGNB, DPPA4, GATA6, ARGFX, RBP7, and KLF5—alongside functional disruptions in epigenetic modifications, mitochondrial DNA, and small non-coding RNAs, play critical roles in the onset of EEA. This review provides a comprehensive understanding of the genetic and molecular underpinnings of EEA, offering a theoretical foundation for the diagnosis and potential therapeutic strategies aimed at improving pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: Early embryonic arrest, Epigenetics, Embryonic genome activation, Mitochondrial DNA, Small non-coding RNA

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, there are currently 186 million people worldwide affected by infertility, making it a significant public health concern [1]. In China, up to 25% of women of childbearing age experience infertility, with female factors and unexplained causes accounting for more than 37% of infertility cases [2–4]. Studies have reported that over 40% of patients undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART) fail to obtain usable embryos due to early embryonic development arrest (EEA), resulting in the inability to obtain viable embryos. This condition has both physical and psychological implications for individuals undergoing ART procedures [3, 4].

Early embryonic arrest (EEA) is defined as growth arrest and developmental arrest of early embryos from zygote to blastocyst, and is one of the main causes of repeated failures in the IVF cycle [5]. The etiology of EEA includes genetic and environmental factors [2].

Among genetic factors, embryonic development is regulated by multiple genes and signaling pathways [3]. Several genes that affect embryonic development have been identified, and they are classified based on their molecular characteristics. These genes include nuclear factors (PATL 2, TRIP 1–3, WEE 2, TBPL 2, REC 114, MEI 1, and CDC 20), cytoplasmic factors (TLE 6, PADI 6, NLRP 2/5, FBXO 43, MOS, and BTG 4), primate-specific factors (TUBB 8), cell membrane factors (PANX 1), and zona pellucida factors (ZP1-3) [6]. Recent research highlights additional pathogenic genes for early embryonic development arrest, such as three functional loss variants of the BTG4 gene [7], four harmful variants of the CHK1 gene, and one harmful variant of the ACTL7A gene [8]. Furthermore, three new variants of the PLCZ1 gene have also been linked to embryonic development arrest [4]. However, the reported genetic variations are still insufficient to explain all cases of EEA, and the exact mechanisms through which genetic variations lead to EEA remain unclear.

This literature review provides a comprehensive analysis of genetic factors and potential mechanisms associated with EEA, focusing on three key dimensions: maternal factors, paternal factors, and embryonic factors. In terms of maternal factors, we categorized genetic factors based on abnormalities in epigenetic factors and genetic variation. The paternal factor was classified based on chromosomal abnormalities, epigenetic abnormalities, and genetic variations. The embryonic factor was classified based on chromosomal abnormalities, abnormal activation of embryonic genome, epigenetic abnormalities, small non-coding RNA, and mitochondrial DNA abnormalities.

In this review, by consolidating the existing knowledge and highlighting gaps, we aim to provide a foundation for future studies on EEA and contribute to the development of diagnostic and treatment approaches for affected individuals.

Genetic factors of EEA

Maternal factors

The initial events of early mammalian embryo development are predominantly regulated by maternal effect factors, which are encoded by maternal effect genes and accumulate during oogenesis. Maternal mRNA and proteins accumulate during oocyte growth, which is crucial for subsequent fertilization and early embryonic development. Recent studies have increasingly focused on the impact of maternal factors on early embryo development.

Maternal factors are the key factors that lead to EEA, which can be divided into two related factors: epigenetic factors and genetic variation. Chromosomal abnormalities leading to EEA mostly occur in elderly mothers, and there is limited research on this topic. Therefore, this review did not discuss it. The study will summarize the connections and mechanisms of maternal genetic factors that have been found to cause EEA.

Epigenetic factors

Studies have shown that both maternal and paternal specific factors in early embryos are involved in genome-wide reprogramming, and epigenetic marks related to them include histone modifications, DNA methylation, and small-molecule non-coding RNA [9].

The effect of DNA methylation on embryonic genome

The transformation of gene expression patterns from oocytes to early embryos, known as the material to zygotic transition, is a key event in early embryonic development. The large amount of maternal mRNA accumulated in human oocytes undergoes degradation in two waves during the mother to zygote transition, namely M-decay and Z-decay.

The NLRP (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing protein) family consists of 14 structurally similar members, with NLRP2, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 14 being associated with reproduction. Previous studies have shown that Nlrp5 (also known as MATER) knockout female mice are infertile due to a block at the two-cell stage. Recently, a study revealed a novel function of maternal NLRP14 in maintaining calcium homeostasis during early development, indicating that fertility issues and early embryonic development failure in Nlrp14mNull female mice are primarily attributed to impaired cytosolic Ca2 + homeostasis. UHRF1 is capable of recognizing hemimethylated DNA, subsequently recruiting DNMT1 to replication sites to maintain DNA methylation. NLRP14 interacts with NCLX, regulating its stability through K27-linked ubiquitination while reducing UHRF1 expression, ultimately leading to disrupted cytosolic Ca2 + homeostasis and triggering early embryonic arrest [10, 11].

During the maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT), the selective turnover and diversification of maternal mRNA are crucial for both the MZT and gametogenesis. Research indicates that NSUN5 encodes the NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 5, which utilizes 5-methylcytosine (m5C) for selective turnover and diversification of RNA modifications. m5C sites are predominantly found within the protein-coding regions (CDS) of RNA, with a peak concentration around the stop codon. A recent study has highlighted the significant role of dynamic m5C methylation in marking and regulating maternal mRNA during MZT, subsequently impacting embryonic development [12, 13].

-

(2)

The effect of histone modifications on embryonic genome

DCAF13 is one of the primary substrate adaptors of the DDB1/CUL4 complex, a type of E3 ubiquitin ligase. Recent studies have shown that DCAF13 connects the ubiquitin E3 ligase CRL4 with the histone methyltransferase SUV39H1, promoting multiubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of this enzyme. CRL4-DCAF13 facilitates the removal of H3K9me3 in preimplantation embryos, thereby enhancing zygotic gene expression [14, 15]. Consequently, in embryos lacking maternal DCAF13 during the two-cell stage, zygotic chromatin is observed to be decondensed, with a significant decrease in transcription, leading to embryonic development arrest.

Genetic variation

In addition to the regulatory role of epigenetic modifications on maternal gene expression, mutations in maternal genes associated with embryonic development can also lead to EEA. This includes genes related to cytoplasmic lattice, nucleoprotein transport, maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT), and follicular fluid. These studies aim to explore the mechanisms underlying EEA and provide new biomarkers for clinical diagnosis.

Cytoplasmic lattice–related genes

Cytoplasmic lattices are essential structures in oocytes that store proteins necessary for early embryonic development. Research has shown that these lattices are composed of high-surface-area filaments, containing proteins such as cysteine protease PADI6 and subcortical maternal complex (SCMC) proteins. The lattice is associated with many proteins crucial for embryonic development, including those involved in preimplantation embryo epigenetic reprogramming, such as UHRF1 (a protein with PHD and RING-like ubiquitin domains). Knocking out PADI6 or components of the subcortical maternal complex results in the loss of cytoplasmic lattices, preventing the accumulation of these key proteins and leading to EEA [16].

SCMC is composed of maternal-encoded proteins, including NLRP5 (also known as MATER), TLE6, OOEP (FLOPED), KHDC3 (FILIA), NLRP4f, and ZBED3. MATER interacts with TLE6 and FLOPED through its NACHT and LRR domains, forming a strong interaction in vitro via the two LRR domains of MATER, leading to further dimerization. FILIA is integrated into the SCMC by interacting with the carboxy-terminal region of FLOPED. This complex plays a crucial role in early embryonic development by facilitating the proper localization and function of essential proteins [16, 17].

Notably, SCMC is functionally conserved in humans, and accumulating evidence suggests that mutations in human SCMC genes are associated with female reproductive disorders and EEA. The transcripts of these genes accumulate during oocyte maturation, and although mRNA is degraded during meiosis, the homologous proteins continue to function into the early blastocyst stage of pre-implantation embryos.

Research indicates that the localization of the SCMC complex in the trophoblast cells of the blastocyst may suggest that the presence of SCMC directly or indirectly triggers the commitment of these external cell descendants to become trophoblasts. The expression of the genes encoding these proteins (FLOPED, MATER, TLE6, PADI6) is regulated by FIGLA (a germline factor, alpha), a bHLH transcription factor. FIGLA was initially identified as a transcription factor regulating the coordinate expression of zona pellucida genes (Zp1, Zp2, Zp3), which encode proteins that form the extracellular matrix surrounding the oocyte and pre-implantation embryo [18].

PADI6, as a component of the cytoplasmic lattice, is the fifth and least well-characterized member of the peptidyl arginine deiminases (PADIs) family, catalyzing the post-translational conversion of arginine to citrulline. It is primarily expressed in oocytes and early embryos and is critical for early embryonic development and female fertility in both humans and mice. Research has shown that the compound heterozygous variant S3Qfs*65/C666Lfs*53 in the PADI6 is associated with EEA. Additionally, two novel homozygous variants, c.487 T > C [p.Cys163Arg] and c.1425G > A [p.Trp475*], have been identified in a cohort of 75 women with EEA phenotypes [19]. Recent studies suggest that PADI6 may be involved in embryonic genome activation (EGA) and is related to trophoblast proliferation and invasion. These insights provide valuable directions for further research in this area [20, 21].

-

(2)

Nuclear protein translocation related genes

Nuclear protein transport from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is mediated by importins, with the importin α/β system being the primary pathway for cNLS cargo. KPNA7 encodes importin α7 (also known as importin α8), which facilitates protein transport between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Clinical studies have identified homozygous recurrent variants (c.C607T, p.L203F) and homozygous missense variants (c.G454A, p.V152M) [22]. It is hypothesized that these mutations result in reduced protein levels of KPNA7 and impaired transport activity, disrupting nuclear import of specific substrates and affecting the onset of zygotic genome activation (ZGA). RSL1D1, a downstream substrate of KPNA7, exhibits pathogenic variants that compromise the interaction between KPNA7 and RSL1D1. Additionally, mouse Kpna2 (mKpna2) is considered a homolog of human KPNA7 (hKPNA7), indicating a critical role for KPNA7 in human embryonic development, whereas mKpna2 functionally compensates in mice. Thus, Kpna2−/− mice represent a valid model for elucidating the pathogenesis of EEA related to KPNA7 dysfunction [23]. Therefore, EEA may result from impaired nuclear protein transport, although the specific mechanisms of interaction require further investigation.

-

(3)

Follicular fluid–related genes

Follicular fluid (FF) is produced during the follicular development process and acts as a microenvironment for oocyte maturation and differentiation. Ongoing research focuses on understanding the mechanisms associated with EEA and a particular emphasis on molecular markers present in FF. The insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) gene stands as the initial identified endogenous imprinted gene, showcasing its multifunctional role as a cell proliferation regulator. It significantly contributes to cell differentiation, proliferation, embryonic growth and development, and tumor cell proliferation [24]. Recent investigations have revealed that elevated levels of IGF-II, IGFBP-3, and IGFBP-4, coupled with reduced levels of PAPP-A in follicular fluid (FF) during oocyte retrieval, align with improved oocyte maturation and early embryonic development (within 48 h of post-oocyte retrieval). Conversely, heightened levels of IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-4, along with diminished levels of FF IGF-I, may positively influence late embryonic development (between 48 and 72 h of post-oocyte retrieval) [25, 26].

-

(4)

Other genes

During the maternal ovulation cycle, follicle development progresses through four stages: primordial follicle, primary follicle, secondary follicle, and mature follicle. Genetic mutations or chromosomal variations that occur during the development and maturation of follicles can result in abnormal development of eggs or an atypical composition of the follicular fluid. These anomalies may lead to abnormal development of early embryos following fertilization.

Conditions affecting the normal development of follicles include chromosomal abnormalities and gene mutations. Chromosomal abnormalities include aneuploidy, balanced and unbalanced chromosomal rearrangements, and mosaicism; gene mutations or genomic alterations include copy number variations (CNVs); and other pathogenic variants [27]. The misexpression of genes involved in fertilization, such as inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 (ITPR 1), CD9, ZP3, ZP4, REC114 [28], and various mutations in TUBB8 [29], PATL2 [30], TRIP13 [31], WEE2 [32], TBP2 [33], and MEI1 [34], and other genes may also lead to the arrest of oocyte development at different stages.

The TUBB8 gene is the most frequently implicated gene in oocyte development arrest. Classified as a maternal effect gene (MEG), this gene comprises four exons located on 10p15.3 and encodes a 444-amino acid protein. It is predominantly expressed during the human oocyte stage and early embryo division, with no presence in mature sperm. The TUBB8 protein falls within the tubulin family (β 8 class VIII), serving as a structural component of microtubules and playing a critical role in spindle formation during meiosis. Consequently, alterations in the protein structure resulting from TUBB8 gene variations can disrupt cell division, leading to oocyte maturation abnormalities and EEA [35]. In numerous instances, heterozygous variants of the TUBB8 gene induce a mid-metaphase I arrest in oocytes via a dominant negative effect. Additionally, certain studies have observed arrest during the early stages of embryonic development. The primary clinical phenotypes observed among individuals with homozygous and compound heterozygous variants, often exhibit milder phenotypes, encompass fertilization failure (MII arrest), and zygote cleavage failure [36, 37]. A recent study detected a novel compound heterozygous mutation in TUBB8, c.915_916delCC (p.Arg306Serfs*21), and c.82C > T (p.His28Tyr). Female patients with the mutation were infertile with EEA. The p.Arg306Serfs*21 mutation was predicted to cause large structural alteration in the TUBB8 protein and was confirmed to produce a truncated and trace protein by western blot analysis [38].

In addition, other maternal effector genes like PATL2 [30] can also cause EEA by interfering with oocyte maturation and embryonic genome activation. Analysis of publicly available data suggests that PATL2 displays high expression levels in both human and mouse oocytes, indicating its significant role in female gametogenesis. In contrast, its expression appears to be low in follicles and other tissues. Previous findings emphasize its crucial involvement in oocyte growth while having limited impact on maintaining the primordial follicle pool within the ovary. Recent studies suggest that PATL2 is involved in regulating the mRNA expression of essential proteins related to oocyte meiosis and early embryonic development [30]. This regulatory mechanism safeguards the integrity of a specific group of mRNAs produced during oocyte maturation, post-fertilization, and early embryonic stages. Interestingly, individuals with PATL2 mutations exhibit about half of their oocytes experiencing arrest in the germinal vesicle (GV) phase, contrasting with non-PATL2 patients where oocyte arrest predominantly occurs in the metaphase I (MI) phase [30, 39, 40]. Indeed, PATL2 plays a significant role in oocyte development and embryonic genome activation. The identified mutation sites of PATL2 and associated mechanisms require further exploration to better understand their impact on reproductive processes.

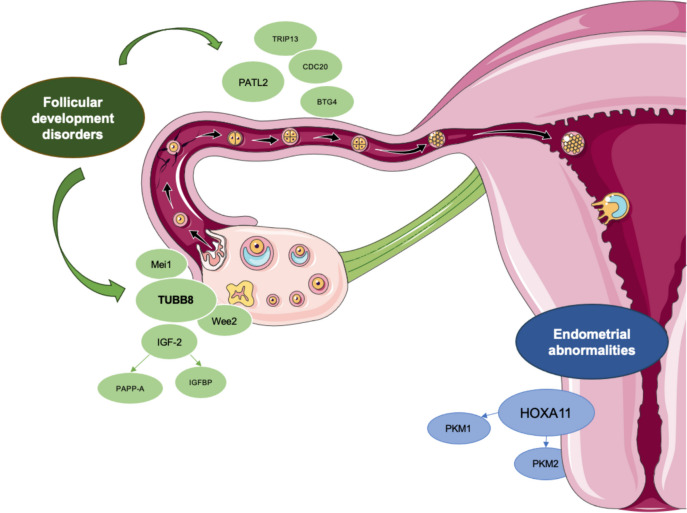

Considering from another perspective, the factors that affect follicle development include genes such as TUBB8, MEI1, and PATL2, while the factors that affect endometrium and implantation include genes such as HOXA11, PKM1, and PKM2 (Fig. 1). It is worth noting that these pathogenic genes play a role in all stages of oocyte and early embryonic development, and extend beyond the aforementioned early embryonic development stages.

Fig. 1 .

Genetic factors affecting oocyte maturation and early embryonic development. This diagram depicts the genetic factors related to EEA that affect the process of oocyte maturation and early embryonic development. The factors that affect egg development include genes such as TUBB8, Mei1, and PATL2, while the factors that affect endometrium and implantation include genes such as HOXA11, PKM1, and PKM2. It is worth noting that these pathogenic genes play a role in all stages of oocyte and early embryonic development, and extend beyond the aforementioned early embryonic development stages

Paternal factors

Influenced by traditional ideas, the role of paternal factors on embryo and fetal development is often ignored. However, studies have shown that about 40–50% of infertility cases are caused by “male factors.” Male infertility is a complex multifactorial pathological condition, which is clinically characterized by low sperm quantity and poor sperm quality, affecting about 7% of the male population [41].

Upon entering the female reproductive tract, sperm undergoes a series of steps for complete fertilization, including sperm capacitation, acrosome reaction, gamete fusion, oocyte activation, and the initiation of embryonic development [42]. Following the sperm-egg fusion, a process called paternal mtDNA elimination (PME) takes place where the paternal mitochondria are eliminated in the embryo. However, the sperm still contributes DNA, centrioles, some cytoplasm, and organelles to support the development of the offspring [43]. The integrity of the sperm genome is essential for the quality and viability of embryos [44]. Paternal genetic factors that impact embryonic development can be categorized into chromosome abnormalities, gene variations, and infertility etiology. These factors play a significant role in determining the successful development of the embryo and can influence various aspects of early embryogenesis.

Chromosomal abnormalities

Chromosomal abnormalities usually include chromosome number and morphological abnormalities [44]. Diseases caused by common karyotype abnormalities include non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) and oligospermia. The most common chromosomal aberrations in infertile men with NOA are Klinefelter syndrome (KS; 47, XXY) and its variants (46, XY/47, XXY) [44]; in contrast, balanced ectopic chromosomes are more common in infertile men with oligospermia [45].

Epigenetic factors

The effect of histone modification on paternal genome activation

Studies have highlighted over ten histone modifications that are critical in embryonic development, such as acetylated H4K12 and H3K27me3 modifications [46]. Abnormal processes like mutations in the histone methyltransferase M112 and decreased expression levels of genes methylated at H3K4 (like BRG1 and KDM1A) can disrupt the modification process [47]. These abnormalities may result in a decreased level of paternally inherited DNA post-embryonic genome activation, ultimately causing the fertilized egg to remain stagnant and impacting further development.

-

(2)

The effect of histone modification on genomic imprinting

DNA methylation is a crucial epigenetic modification that plays a key role in regulating gene expression. Following transcription, DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) facilitates DNA methylation in CpG islands. During early embryonic development, the demethylation process shows an asymmetry between the maternal and paternal genomes. Maternally imprinted genes are often passively demethylated during DNA replication, while paternally imprinted genes undergo rapid and active demethylation [48]. Research indicates that in fertilized eggs, DNA demethylation is driven by the enzyme dioxygenase TET3 [49]. TET3, primarily present in the male pronuclei, converts 5-methylcytosine (5mC) into 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC). The maternal genome inhibits TET3-mediated 5mC oxidation by forming a specific complex with developmental pluripotency-associated 3 (DPPA3), preventing TET3 binding through interaction with the H3K9me2-associated H3 variant [50]. Conversely, the paternal genome lacks H3K9me2 nucleosomes and cannot associate with DPPA3, making it susceptible to the TET3-mediated demethylation [50]. Aberrations in sperm DNA methylation and demethylation processes may lead to a decline in embryo quality, underscoring the importance of proper epigenetic regulation in embryonic development [51].

-

(3)

The effect of small molecule non-coding RNA on embryonic genome

During mammalian fertilization, sperm not only contributes the paternal genome but also carries RNA that may provide essential signals for the developing embryo. The human sperm delivers miR-34c to oocytes that lack this microRNA. Increasing evidence indicates that miRNAs play a critical role in regulating key developmental events in embryos. miR-34c, part of the highly conserved miR-34 family across different species, is preferentially expressed in the mouse testes and is involved in spermatogenesis by modulating relevant targets. Recent studies have highlighted the impact of miR-34c on embryonic development, showing an association between sperm miR-34c levels and outcomes of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) [52].

Experimental results demonstrate that the microinjection of miR-34c inhibitors leads to upregulation of maternal miR-34c-targeted mRNA and classical maternal mRNA expression in zygotic embryos. This suggests that sperm-borne miR-34c downregulates the expression of genes associated with embryonic development (including ALKBH4, SP1, MAPK14, and SIN3A) during the cleavage stage [53].

Genetic variation

The genetic etiology of male infertility can be categorized into mutations affecting sex chromosomes and autosomes. The human Y chromosome is distinguished by three distinct segments: the pseudoautosomal region, the heterochromatic region, and the male-specific region (MSY) [54]. The amplified sequences within the MSY region are highly repetitive, primarily consisting of palindromic or inverted repeats, and harbor a multicopy gene family crucial for spermatogenesis [44]. Alterations, such as deletions, duplications, and inversions of these sequences, can lead to severe phenotypic consequences, including azoospermia and oligospermia [55, 56].

A retrospective cohort study followed patients from January 2017 to August 2019, during which patients were divided according to the cause of infertility to male factor (study group) and unexplained infertility (control group). The result is that intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) was conducted more often in the study group compared to the control group (94% vs. 47%, p < 0.0001) and more embryos were discarded (47% vs. 43%, p = 0.016) [57–59]. Consequently, the paternal genome may have an earlier impact on embryo development than previously surmised and may also account for faster morphokinetics.

During spermatogenesis, significant changes occur in round spermatids, including chromatin condensation, acrosome formation, elongation of the sperm head, and assembly of the flagellum [60]. The acrosomal structure contains actin-like protein 7A (ACTL7A), which belongs to the highly conserved actin-related protein (ARP) family, sharing 17–45% sequence homology with actin [60]. Loss of ACTL7A results in teratospermia. Recent studies indicate that ACTL7A may not participate in acrosome assembly but plays a crucial role in the biogenesis of acrosomes, specifically in the formation and fusion of Golgi-derived vesicles. Patients with the ACTL7A missense mutation c.733G > A (p.Ala245Thr) experienced early embryonic arrest (EEA) during intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), with embryo development halting at the four- or five-cell stage. Research has shown that homozygous ACTL7A mutations lead to acrosomal defects associated with the disruption of the perinuclear theca, resulting in reduced and mislocalized phospholipase C zeta (PLCζ) [4, 61]. Fortunately, recent findings demonstrate that artificial oocyte activation (AOA) can successfully bypass the embryo developmental arrest caused by this mutation, allowing offspring from Actl7a mutant mice. This discovery provides valuable insights for improving clinical practices related to in vitro fertilization (IVF) and ICSI and offers potential guidance for appropriate therapeutic interventions.

Sperm DNA fragmentation arises from the breakdown and accumulation of single-stranded and double-stranded DNA within the sperm genome. Failure to repair these DNA aberrations can result in abnormal embryonic development. Various intrinsic factors contribute to SDF, including defective histone replacement with protoamines [62], chromatin-packaging defects, nuclease-mediated enzymolysis, abortive apoptosis–like changes, and oxidative stress [63]. Some studies suggest that the limited DNA repair mechanisms in oocytes can lead to residual DNA aberrations, increasing the mutation load of embryos and adversely affecting blastocyst formation [64]. However, the detection of DNA fragmentation is influenced by methodological sensitivities, and the degree of fragmentation has varying effects on embryo development. Consequently, this detection method has not been routinely employed to predict embryo viability in clinical settings. This underscores the need for standardized identification methods and further research into the underlying mechanisms.

Based on the above content, we can conclude that among the genetic factors that lead to EEA, maternal and paternal factors can be classified according to chromosomal abnormalities, epigenetic modification abnormalities, and gene mutations. Various factors lead to different effects, ultimately resulting in developmental arrest due to abnormal genome activation in early embryos or affecting the progression of MZT(Table 1).

Table 1.

Pathogenicity classification of EEA-associated genetic variants from maternal of paternal factors

| Genes | Variants | Amino acid changes | ACMG* pathogenicity | Evidential rules | Maternal/paternal factor | Variants reported from references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLRP14 | c.1282_1283delTG | p.Cys428Profs ∗ 28 | VUS** | PM2 supporting | Maternal | [11] |

| c.2660delinsGCTA | p.Leu887delinsArgTyr | Likely benign | BP4, BP3, PM2 supporting | Maternal | [11] | |

| PADI6 | c.487T > C | p.Cys163Arg | VUS | PM2 supporting, PP3 supporting | Maternal | [19] |

| c.1425G > A | p.Trp475* | Likely pathogenic | PVS1, PM2 supporting | Maternal | [19] | |

| KPNA7 | c. 607C > T | p.L203F | Likely benign | BP4, BS3, BP1, PM2 supporting | Maternal | [22] |

| c. 454G > A | p.V152M | VUS | PM2 supporting, PP3 supporting, BP1 supporting | Maternal | [22] | |

| TUBB8 | c.915_916delCC | p.Arg306Serfs*21 | Likely pathogenic | PVS1, PM2 supporting | Maternal | [38] |

| c.82C > T | p.His28Tyr | VUS | PP3 strong, PP2 supporting, BS2 strong | Maternal | [38] | |

| PATL2 | c.223-14_223-2del | p.R75Vfs*15 | Likely pathogenic | PVS1, PM2 supporting | Maternal | [39] |

| c.716delA | p.N239fs*9 | Likely pathogenic | PVS1, PM2 supporting | Maternal | [40] | |

| PLCZ1 | c.1208_1213del | p.403_404del | Likely pathogenic | PM1 strong, PM4 moderate, PM2 supporting | Paternal | [4] |

| c.1466T > G | p.I489S | Likely pathogenic | PM5 moderate, PP3 moderate, PM1 supporting, PM2 supporting | Paternal | [4] | |

| c.1607C > T | p.W536X | VUS | PP3 moderate, PM1 supporting, PM2 supporting | Paternal | [4] | |

| ACTL7A | c.733G > A | p.Ala245Thr | Likely benign | BS2 strong, PP3 moderate, BP1 supporting | Paternal | [60] |

*ACMG American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

**VUS variant of uncertain significance

Embryo factors

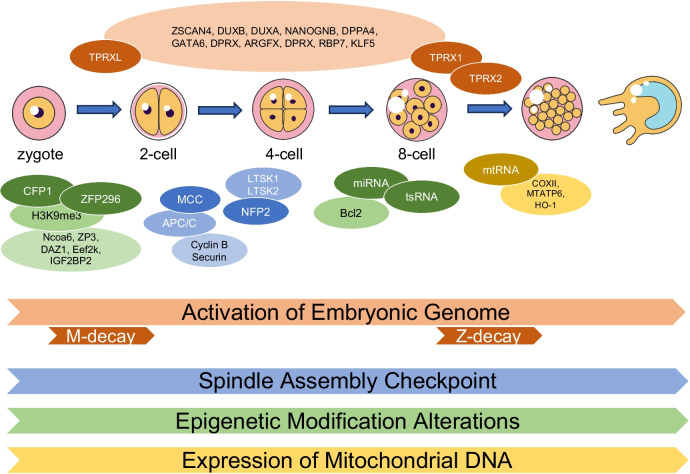

Research has revealed that multiple factors, such as chromosomal abnormalities, disrupted activation of the embryonic genome, irregular patterns of DNA methylation, genetic variations, abnormalities in mitochondrial DNA copy numbers, malfunctioning of small non-coding RNA, and other correlated factors, have been identified as potential contributors to the cessation of early embryonic development (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Embryonic factors associated with EEA during embryonic development. Early embryos in mitosis undergo key events such as embryonic genome activation, mitotic checkpoints, epigenetic modifications, and mtDNA expression. The relevant factors that play a role in these events are indicated by orange, blue, green, and yellow respectively. The transformation of gene expression patterns from oocytes to early embryos, known as the material to zygotic transition, is the first key event in early embryonic development. The large amount of maternal mRNA accumulated in human oocytes undergoes degradation in two waves during the mother to zygote transition, namely M-decay and Z-decay. The transformation factor TPRXL plays a role in M-decay, while TPRX1 and TPRX2 play a role in Z-decay and activate related genes such as ZSCAN4, DUXB, and DPPA4 in embryonic development. In mitotic checkpoint events, the spindle checkpoint is activated by MCC, and NFP2 activates the Hippo pathway. In epigenetic modification events, the interaction between CFP1 and ZFP296 proteins and regulatory factors causes differential methylation of gDMRs in the control region, thereby regulating the expression of imprinted genes. MtDNA affects mitochondrial metabolic activity by affecting the expression of mitochondrial genes

Chromosomal abnormalities

Chromosomal abnormalities are commonly encountered in preimplantation embryos, with over 50% of embryos arrested exhibiting such aberrations [65]. Even embryos exhibiting optimal morphology and development from patients below 35 years old displayed a significant aneuploidy rate of 56% [66]. Concurrent studies using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) have demonstrated a considerable proportion of embryos manifesting mosaicism, highlighting a noteworthy association between aneuploidy and developmental arrest [67–72]. For cleavage-stage embryos, more than 80% exhibit chromosomal abnormalities, with approximately one-fourth harboring meiotic abnormalities and around 70% demonstrating postzygotic chimeric abnormalities [73–77, 27, 78]. Notably, a recent study revealed that 18.7% of over 6000 clinical large trophoblastic ectoderm (TE) biopsies were chimeric [29]. These findings underscore the significance of chromosomal integrity in embryonic development and the need for advanced genetic screening methods to enhance embryo selection and ultimately improve pregnancy outcomes.

The spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) consists of a sensory apparatus that monitors the state of the chromosome attached to the mitotic (or meiotic) spindle and an effector system targeting the basic cell cycle machinery, and reversible protein phosphorylation is an important regulator of its signaling pathway and its downstream effector [79–81]. The SAC monitors chromosome biorientation on the mitotic spindle, whose main role is to prevent cell division with improper chromosome attachment, a function that protects the genome from chromosome copy number changes and protects cells from the dire consequences [82]. In addition, SAC effectors are known as the mitotic checkpoint complex (MCC), which target the anaphase promoting complex or cyclic osomes (APC/C). This ubiquitin ligase triggers mitotic exit by polyubiquitination of two key substrates, cyclin B and securin, which in turn promotes their rapid destruction by proteasomal [83, 84]. By inhibiting the APC/C, the MCC stabilizes these substrates, effectively preventing mitotic exit. Abnormalities in any part of this process can lead to chromosome abnormalities, which in turn triggers EEA [85].

Beyond the spindle assembly checkpoint, multiple molecular signaling pathways, specifically the Wnt, MAPK, and Hippo pathways, play roles in embryo aneuploidy, potentially leading to developmental arrest and/or implantation failure. Additionally, nerve fiber protein 2, an upstream factor in the Hippo pathway responsible for the regulation of large tumor suppressor kinases 1 and 2, is implicated in centrosome localization and spindle orientation during mitosis. In addition to the various pathways described above, there is a hypothesis that defects in the mRNA and protein reserves inherited from oocytes in mitotic aneuploid embryos may not be able to adequately maintain the activation of the primary embryonic genome. Aneuploid cells are systematically removed from the epidermis in a process dependent on p53, achieved through autophagy-mediated apoptosis. The compensatory mechanism involves a heightened proliferation of euploid cells [86]. Intriguingly, the autophagy observed in this context is found to be independent of the mammalian targets of the rapamycin pathway. The authors hypothesize that the cascade reaction connecting autophagy and apoptosis may be facilitated through the interaction of p62 and caspase-8, involving the degradation of cellular components or even mitochondria, either directly or indirectly [87].

Factors such as the abnormal embryonic cell cycle [88], blastomere lysis, heightened expression of anti-apoptotic agents [89], and unstable mRNA and protein reserves and the intricate interplay between them like appear to contribute to chromosomal chaos in human embryos [90]. Furthermore, the uneven distribution of mRNA in sister blastomeres leading to cells of different lineages could also contribute significantly to numerous chromosomal abnormalities [91].

It is noteworthy to consider the genetic perspective, where certain chromosomal abnormalities exhibit varying impacts on early embryonic development at the genetic level, such as gene loss or integrity damage and variants at the level of certain genes can also lead to chromosomal anomalies, for example, scholars have studied the polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4) gene, which is involved in centromere replication. Variants in this gene have been linked to an elevated occurrence of mitotic errors during the lysis of blastomeres in anaphase. However, one aspect that remains unverified by the researchers is the absence of an apparent correlation between chromosome fragility and genome activation. This is an area that requires in-depth exploration to better understand the underlying mechanisms and potential interactions between these factors in EEA [87].

Abnormal activation of embryonic genome

Embryonic genomic activation (EGA) stands as the pivotal initial event in early embryonic development [69, 86]. This process is characterized by the accumulation of maternal mRNA in human oocytes, culminating in the completion of maternal degradation during the cleavage stage (M-decay) and zygotic degradation during blastocyst formation (Z-decay) [68, 70]. Studies underscore that mammalian EGA is notably influenced by alterations in epigenetic modifications and exhibits a certain degree of conservation across species [92]. Inhibition of EGA can result in the arrest of early embryonic development and failure in embryo implantation [72, 77].

A study employing the combined techniques of ultrasensitive Ribo-lite and Smart-seq2 identified a subset of PRD-like homeobox transcription factors (TFs) that undergo heightened translation either before or during EGA. The motifs of these TFs were found to be enriched in the distal open chromatin region, acting as a hypothetical enhancer located near the activating gene on ZGA. Notably, the collective knockdown of TPRX1/2, referred to as TPRX triple KD (TKD), resulted in severe defects in both development and EGA [93]. Within the TPRX TKD group, downregulated EGA genes (both major and minor), encompass ZSCAN4, DUXB, DUXA, NANOGNB, Dppa4, GATA6, DPRX, ARGFX, DPRX, RBP7, and KLF5. Notably, Dppa4 has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in activating developmental genes in mice, while GATA6 is known for its pivotal role in regulating early lineage specification [72, 94]. Moreover, research highlights that ectopic expression of TPRX can lead to the activation of a specific subset of EGA genes in human embryonic stem cells(hESCs) [93]. These findings indicate that both TPRXL and TPRX1/2 contribute significantly to EGA and may activate downstream transcription factors, initiating a cascade of transcriptional events.

In subsequent investigations, it is imperative to comprehend the involvement of TFs in EGA and elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms of interaction. Such insights lay the foundation for prospective interventions in addressing human infertility disorders. Moreover, according to our unpublished data, the mechanism of abnormal EGA is still being explored, and the role of genes such as PATL2 in the activation of the embryonic genome also needs to be further elucidated.

Epigenetic modification alterations

The effect of DNA methylation on embryonic genome

Genomic imprinting is a pivotal epigenetic mechanism enabling certain genes to exhibit parent-specific expression, distinct from the coordinated regulation by both chromosomes. This mechanism holds immense significance for the typical growth and development of early embryos and individuals [95]. Imprinted genes crucially influence embryonic development and are governed by distinct methylation-specific DNA sequences known as the imprinting control region (ICR). The regulation of most imprinting domains occurs through germline differential methylation regions (gDMRs). Among the confirmed 23 gDMRs, 20 display methylation on the maternal allele and three on the paternal allele. Within the multi-gene imprinting domain, there exist patterns of maternal, paternal, and biallelic gene expressions, indicating that gDMRs regulate chromatin structure extensively, affecting the expression of multiple target genes [96]. Another study highlighted the nuclear localization of the zinc finger protein ZFP296, which interacts with a spectrum of epigenetic regulators including KDM 5B, SMARCA 4, DNMT 1, DNMT 3B, HP 1β, and UHRF 1. Specifically, the Cys 2-His 2 (C2H2) zinc finger domain of ZFP296, specifically the TYPE 2 and TYPE 3 domains, co-regulates the trimethylation level of lysine 9 on the histone H3 protein subunit (H3K9me3) [92]. In the context of genome activation (EGA) and ZFP296 knockout embryonic stem cells (mESC), there were observed alterations in the expression of gene subgroups including Ncoa6, ZP3, DAZ1, Eef2k, and IGF2BP2 (IMP2), pivotal in EEA. These results underscore the essential role of Zfp296 as an H3K9me3 regulator crucial for initiating embryonic genome activation [97, 98].

Furthermore, there has been a proposition regarding the methylation pattern of autophagy-related (ATG) genes in early embryonic cells [99]. The epigenetic status of ATG genes during the early stages of embryonic development was investigated using the scCOOL-seq dataset. This analysis aimed to infer the level of genomic methylation. Examination of the methylation levels in the promoter region revealed distinctive patterns at various stages. When compared with all detected non-autophagy-related genes, the ATG promoter exhibited a decrease in methylation (average ratio, 35.69% in the four-cell stage, 56.93% in human embryonic stem cells; all ratios were less than 100%) [99]. Furthermore, it has been observed that the methylation levels of specific ATG genes exhibit stage-specific variations during EEA. This finding may provide insights into the transcription kinetics of these genes at different developmental stages [99].

Methylation patterns serve as epigenetic modifications governing gene expression. Rapid alterations in genetic and epigenetic traits represent a pivotal aspect of early human embryonic development. Importantly, under laboratory settings, cultural conditions and methodologies exert a substantial influence on epigenetic modifications. Therefore, there is still considerable progress required to effectively employ epigenetic modifications as markers for identifying delays in EEA and unraveling the underlying mechanisms.

-

(2)

The effect of histone modification on embryonic genome expression

The transcription factor (TF) binding to DNA is fundamental for gene regulation. Studies have shown that the pluripotency TFs Oct4 and Sox2 exhibit more stable DNA binding in embryonic pluripotent cells than in extra-embryonic cells. In four-cell embryos, Sox2 interacts for a longer duration compared to Oct4, with this prolonged binding varying among embryonic cells and being regulated by H3R26 methylation. Methylation of H3R26, mediated by the histone arginine methyltransferase CARM1, regulates the longevity of paGFP-Sox2 binding, subsequently influencing the transcription of genes related to embryonic development and determining the cleavage orientation in the two- to fur-cell stage [100, 101].

Decreased fertility in older women and older mice has been reported to be closely associated with decreased H3K4 methylation in oocytes, revealing a critical role of H3K4 methylation in female fertility [102, 103]. However, how H3K4 methylation regulates oocyte development remains largely unexplored. In a study investigating the role of H3K4 by constructing a dominant-negative mutant H3.3-K4M model, it was observed that the level of H3K4 methylation was decreased in oocytes from transgenic mice and oocyte development and maturation, as well as overall transcriptional activity, were significantly affected. Moreover, mitochondrial function was impaired in H3.3 to K4M oocytes. Early embryos from H3.3 to K4M oocytes showed developmental arrest and reduced syncytial genome activation. These results suggest that H3K4 methylation in oocytes is critical for orchestrating gene expression profiles, driving oocyte developmental programs, and ensuring oocyte quality. This study also improves the understanding of how histone modifications regulate organelle dynamics in oocytes [104]. In addition, it has been shown that Cxxc finger protein 1 (CFP1) deletion in oocytes leads to a decrease in H3K4 methylation levels, which alters the normal distribution of mitochondria, Golgi, endoplasmic reticulum, and other organelles, suggesting that H3K4 methylation controls cytoplasmic maturation of oocytes [105]. During meiotic maturation, Cxxc1-deficient oocytes exhibited reduced rates of germinal vesicle rupture and polar body 1 firing, revealing an important role of H3K4 methylation in the process of oocyte nuclear maturation [106].

H3.3 to K4M transgenic mice showed developmental blockage of early embryos mainly occurring at the two- to four-cell stages, researchers found that in early two-cell embryos, the levels of H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9me3, H3K27me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac, H3K64ac, and H4K16ac levels were all significantly reduced, while none of the total H4 levels were affected, which suggests that methylation of H3K4 in oocytes ensures the establishment of other histone modifications [104].

-

(3)

The effect of small-molecule non-coding RNA on embryonic genome

The intricate modifications that small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs) undergo significantly influence their roles in diverse biological functions [107]. Recent research has shed light on the role of sperm sncRNA as a molecular carrier, capable of transmitting the effects of paternally acquired characteristics or environmental exposures to offspring [65, 66]. In particular, studies have indicated that sperm transfer RNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) may play a role in the regulation of early embryonic development [93]. Additionally, microRNA-34C carried by sperm has been implicated in participating in the first cleavage of embryos by regulating the expression of Bcl2.

Examining other sncRNAs, studies have noted differential expression of 13 sncRNAs in stagnant blastocysts compared to good-quality blastocysts. However, when comparing high-quality blastocysts to low-quality blastocysts, only hsa-let-7i-5p showed differential expression [27]. Despite these findings, the understanding of the impact of sncRNAs on EEA is still limited, and further experiments and data are crucial to rigorously validate and fully elucidate these results. More comprehensive studies are needed to reveal the molecular mechanisms underlying this aspect of related diseases. The complexity of sncRNA modifications and their diverse roles in biological processes make them intriguing subjects for further exploration in the context of reproductive biology and embryonic development.

Interestingly, in recent years, studies have indicated that alcohol consumption can also induce changes in epigenetic markers, encompassing alterations in DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA [108].

Mitochondrial DNA copy number abnormalities

To address the limitations in selection criteria for intrauterine transfer embryos, such as the inability to capture dynamic processes, the lack of precise criteria, and variability related to subjective scoring systems, researchers have explored alternative methods, and one promising approach involves assessing mitochondrial RNA (mtRNA) content in the culture medium. This non-invasive biomarker has shown a significant association with the fragmentation rate of embryos developing for 2–3 days [109]. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations can potentially disrupt continuous mitochondrial metabolic activity crucial for oocyte maturation [110]. In particular, a study investigated the permeability of cells to K_2Tl + and K_2K + and found them to be approximately equal. This is attributed to the similar valence state and crystal radius of K_2Tl + and K_2K + . Once inside the cell, K + -ATP-dependent channels may play a role in transporting Tl + across the mitochondrial inner membrane, potentially leading to mitochondrial dysfunction through a series of cascade reactions [111, 112]. Studies suggest a significant association between high Tl exposure, mtDNA 16,519 gene variants, and an increased risk of EEA. The interaction between thallium exposure and 16,519 mtDNA gene polymorphisms amplifies the association strength, underscoring the impact of this interplay on in vitro oogenesis and EEA [27, 113]. Additionally, Research pointed out that a downregulation in the expression levels of cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (COXII) and ATP synthase subunit 6 (MTATP6) in cumulus cells (CC) within non-viable embryos. This underscores the significance of optimal mitochondrial function during the initial stages of development [114]. Given the potential detriment of extensive oxidative stress on oocyte ability, heightened expression of the heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) gene in stagnant embryos also serves as an indicator of mitochondrial dysfunction [114, 115].

The utility of mtDNA copy number as a non-invasive biomarker for selecting embryos with optimal competence has been a subject of investigation. Several studies have explored the correlation between mtDNA levels and in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle outcomes. However, the effectiveness of mtDNA quantification as a valuable adjunct to embryo selection remains a matter of controversy [27]. A study highlighted that the overall levels of mtDNA were essentially comparable among blastocysts categorized by factors such as ploidy, age, or implantation potential. Notably, survival blastocysts did not exhibit significantly different levels of mtDNA compared to non-survival blastocysts [116]. The reported heterogeneity has been attributed to variations in research settings, laboratory conditions, limited data, and inconsistent results in investigating the role of mtDNA in EEA. Hence, it is crucial to emphasize the need for comprehensive validation and evaluation of experimental conditions, data, and results before considering the implementation of mtDNA quantification as a biomarker in clinical settings. This calls for further well-designed experiments that can assure the reliability and reproducibility of findings across diverse contexts.

Conclusion, discussion, and perspectives

In recent years, researchers have made significant progress in genetic research related to early embryonic arrest (EEA), and studies have identified genetic factors associated with EEA. This review provides an integrated overview of genetic factors and molecular mechanisms implicated in EEA, categorizing them into maternal factors, paternal factors, and embryonic factors. Maternal factors, including abnormalities in epigenetic modifications and gene mutations, have been found to cause EEA. Abnormal epigenetic modifications include mutations in NLRP14 and NSUN5, which result in the dysregulation of DNA methylation, as well as mutations in DCAF13 that lead to abnormal histone modifications. Genetic mutations encompass specific loci in maternal genes such as SCMC, PADI6, KPNA7, and TUBB8, which impact the zygotic genome activation (ZGA) or maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) processes, ultimately affecting normal embryonic development. Paternal factors contribute to EEA through chromosomal abnormalities, epigenetic modifications, and gene mutations. Studies have reported that the absence of H3K9me2 nucleosomes can affect TET3 demethylation through interactions with DPPA3, playing a role in EEA. Additionally, research has demonstrated the significant role aneuploidy plays in EEA, through mechanisms embodying spindle assembly checkpoints and signaling pathways including Wnt, MAPK, and Hippo. It is worth noting that novel variants in ACTL7A can lead to acrosomal defects, resulting in EEA. Embryonic factors, such as genes involved in EGA, ZSCAN4, DUXB, DUXA, NANOGNB, DPPA4, GATA6, DPRX, ARGFX, RBP7, and KLF5, have been identified. Epigenetic modifications of genomic DNA also impact the expression of specific target genes. Moreover, factors which induce disruption in mtDNA functions can contribute to EEA.

Despite these advancements, certain aspects of EEA research remain unresolved. The detailed mechanisms of many candidate genes associated with EEA are not fully understood. Further investigations are needed to understand the effects of follicular fluid biomarkers like aquaporin and luteinizing hormone on embryonic development, as well as the mechanisms underlying PATL2 mutations in EEA. The mechanism of miRNA abnormalities affecting embryonic development requires deeper exploration. While some studies are still in the animal experimental stage, the role of genetic research in humans needs further clarification. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific mechanisms by which genes operate at various stages of embryonic development. Additionally, exploring underlying molecular mechanisms of EGA represents a promising area in the future. These efforts aim to enhance our understanding of the causes and mechanisms for EEA and provide potential targets for genetic counseling, diagnosis, and treatment.

In conclusion, this review comprehensively examines the intricate interplay between diverse genetic factors and embryonic development, serving as a theoretical framework for genetic exploration in this field and offering research directions for investigating future mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editors and reviewers for their significant contributions during the revision period.

Author contribution

ZH and MW conceived the manuscript. JZ, JL, and JQ drafted the manuscript. JZ drew the figures. JY, JL, JQ, and MW collected the references. MW, ZH, MZ, XH, BM, JW, and YG proofread the manuscript and made revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No.82301817 to MW and No. 82071659 to MZ) and Knowledge Innovation Program of Wuhan-Shuguang Project (No.2022020801020492 to MW).

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jinyi Zhang, Jing Lv, and Juling Qin shared first authorship and contributed equally in this article.

Contributor Information

Mei Wang, Email: wangmei1990@whu.edu.cn.

Zhidan Hong, Email: ZN000998@whu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Inhorn MC, Patrizio P. Infertility around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:411–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solovova OA, Chernykh VB. Genetics of oocyte maturation defects and early embryo development arrest. Genes. 2022;13(11):1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sang Q, Zhou Z, Mu J, Wang L. Genetic factors as potential molecular markers of human oocyte and embryo quality. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:993–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin Y, Huang Y, Li B, Zhang T, Niu Y, Hu S, Ding Y, Yao G, Wei Z, Yao N, et al. Novel mutations in PLCZ1 lead to early embryonic arrest as a male factor. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1193248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCoy RC, Summers MC, McCollin A, Ottolini CS, Ahuja K, Handyside AH. Meiotic and mitotic aneuploidies drive arrest of in vitro fertilized human preimplantation embryos. Genome Med. 2023;15:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen BB, Li B, Li D, Yan Z, Mao XY, Xu Y, Mu J, Li QL, Jin L, He L, et al. Novel mutations and structural deletions in TUBB8: expanding mutational and phenotypic spectrum of patients with arrest in oocyte maturation, fertilization or early embryonic development. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu RY, Zhou YF, Li QL, Chen BB, Zhou Z, Wang L, Wang L, Sang Q, Jin L. A novel homozygous missense variant in BTG4 causes zygotic cleavage failure and female infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:3261–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou XP, Xi QS, Jia WM, Li Z, Liu ZX, Luo G, Xing CX, Zhang DZ, Hou MQ, Liu HH, et al. A novel homozygous mutation in ACTL7A leads to male infertility. Mol Genet Genomics. 2023;298:353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Yuan P, Yan Z, Yang M, Huo Y, Nie Y, Zhu X, Qiao J, Yan L. Single-cell multiomics sequencing reveals the functional regulatory landscape of early embryos. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng TG, Guo JN, Zhu L, Yin Y, Wang F, Han ZM, Lei L, Ma XS, Xue Y, Yue W, et al. NLRP14 safeguards calcium homeostasis via regulating the K27 ubiquitination of Nclx in oocyte-to-embryo transition. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10:e2301940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang W, Zhang R, Wu L, Zhu C, Zhang C, Xu C, Zhao S, Liu X, Guo T, Lu Y, et al. NLRP14 deficiency causes female infertility with oocyte maturation defects and early embryonic arrest by impairing cytoplasmic UHRF1 abundance. Cell Rep. 2023;42:113531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding C, Lu J, Li J, Hu X, Liu Z, Su H, Li H, Huang B. RNA-methyltransferase Nsun5 controls the maternal-to-zygotic transition by regulating maternal mRNA stability. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12:e1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu R, Sun C, Chen X, Yang R, Luan Y, Zhao X, Yu P, Luo R, Hou Y, Tian R, et al. NSUN5/TET2-directed chromatin-associated RNA modification of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine governs glioma immune evasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121:e2321611121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Zhao LW, Shen JL, Fan HY, Jin Y. Maternal DCAF13 regulates chromatin tightness to contribute to embryonic development. Sci Rep. 2019;9:6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higuchi C, Yamamoto M, Shin SW, Miyamoto K, Matsumoto K. Perturbation of maternal PIASy abundance disrupts zygotic genome activation and embryonic development via SUMOylation pathway. Biol Open. 2019;8(10):bio048652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jentoft IMA, Bäuerlein FJB, Welp LM, Cooper BH, Petrovic A, So C, Penir SM, Politi AZ, Horokhovskyi Y, Takala I, et al. Mammalian oocytes store proteins for the early embryo on cytoplasmic lattices. Cell. 2023;186:5308-5327.e5325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chi P, Ou G, Qin D, Han Z, Li J, Xiao Q, Gao Z, Xu C, Qi Q, Liu Q, et al. Structural basis of the subcortical maternal complex and its implications in reproductive disorders. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2024;31:115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Baibakov B, Dean J. A subcortical maternal complex essential for preimplantation mouse embryogenesis. Dev Cell. 2008;15:416–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y, Wang R, Pang Z, Wei Z, Sun L, Li S, Wang G, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Ye H, et al. Novel homozygous PADI6 variants in infertile females with early embryonic arrest. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:819667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams JPC, Walport LJ. PADI6: What we know about the elusive fifth member of the peptidyl arginine deiminase family. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2023;378:20220242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao G, Zhu X, Lin Y, Fang J, Shen X, Wang S, Kong N. A novel homozygous variant in PADI6 is associate with human cleavage-stage embryonic arrest. Front Genet. 2023;14:1243230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oostdyk LT, Wang Z, Zang C, Li H, McConnell MJ, Paschal BM. An epilepsy-associated mutation in the nuclear import receptor KPNA7 reduces nuclear localization signal binding. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, Miyamoto Y, Chen B, Shi J, Diao F, Zheng W, Li Q, Yu L, Li L, Xu Y, et al. Karyopherin α deficiency contributes to human preimplantation embryo arrest. J Clin Invest. 2023;133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Yang Y, Ren Z, Xu F, Meng Y, Zhang Y, Ai N, Long Y, Fok HI, Deng C, Zhao X, et al. Endogenous IGF signaling directs heterogeneous mesoderm differentiation in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep. 2019;29:3374-3384.e3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang TH, Chang CL, Wu HM, Chiu YM, Chen CK, Wang HS. Insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF-II), IGF-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3), and IGFBP-4 in follicular fluid are associated with oocyte maturation and embryo development. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kordus RJ, Hossain A, Corso MC, Chakraborty H, Whitman-Elia GF, LaVoie HA. Cumulus cell pappalysin-1, luteinizing hormone/choriogonadotropin receptor, amphiregulin and hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3 beta- and steroid delta-isomerase 1 mRNA levels associate with oocyte developmental competence and embryo outcomes. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:1457–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sfakianoudis K, Maziotis E, Karantzali E, Kokkini G, Grigoriadis S, Pantou A, Giannelou P, Petroutsou K, Markomichali C, Fakiridou M, et al. Molecular drivers of developmental arrest in the human preimplantation embryo: a systematic review and critical analysis leading to mapping future research. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(15):8353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Dong J, Chen B, Du J, Kuang Y, Sun X, Fu J, Li B, Mu J, Zhang Z, et al. Homozygous mutations in REC114 cause female infertility characterised by multiple pronuclei formation and early embryonic arrest. J Med Genet. 2020;57:187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng R, Sang Q, Kuang Y, Sun X, Yan Z, Zhang S, Shi J, Tian G, Luchniak A, Fukuda Y, et al. Mutations in TUBB8 and human oocyte meiotic arrest. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:223–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christou-Kent M, Kherraf ZE, Amiri-Yekta A, Le Blévec E, Karaouzène T, Conne B, Escoffier J, Assou S, Guttin A, Lambert E, et al. PATL2 is a key actor of oocyte maturation whose invalidation causes infertility in women and mice. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10(5):e8515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qu W, Liu C, Xu YT, Xu YM, Luo MC. The formation and repair of DNA double-strand breaks in mammalian meiosis. Asian J Androl. 2021;23:572–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sang Q, Li B, Kuang Y, Wang X, Zhang Z, Chen B, Wu L, Lyu Q, Fu Y, Yan Z, et al. Homozygous mutations in WEE2 cause fertilization failure and female infertility. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:649–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gazdag E, Santenard A, Ziegler-Birling C, Altobelli G, Poch O, Tora L, Torres-Padilla ME. TBP2 is essential for germ cell development by regulating transcription and chromatin condensation in the oocyte. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2210–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Li N, Ji Z, Bai H, Ou N, Tian R, Li P, Zhi E, Huang Y, Zhao J, et al. Bi-allelic MEI1 variants cause meiosis arrest and non-obstructive azoospermia. J Hum Genet. 2023;68:383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng W, Hu H, Zhang S, Xu X, Gao Y, Gong F, Lu G, Lin G. The comprehensive variant and phenotypic spectrum of TUBB8 in female infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:2261–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan P, Zheng L, Liang H, Li Y, Zhao H, Li R, Lai L, Zhang Q, Wang W. A novel mutation in the TUBB8 gene is associated with complete cleavage failure in fertilized eggs. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35:1349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Li Q, Xu X, Wang C, Hu K, Xu J. Novel mutations in TUBB8 and ZP3 cause human oocyte maturation arrest and female infertility. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022;279:132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, Li SP, Huang F, Xu R, Wang D, Song T, Liang BL, Liu D, Chen JL, Shi XB, Huang HL. A novel compound heterozygous mutation in TUBB8 causing early embryonic developmental arrest. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2023;40:753–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu L, Chen H, Li D, Song D, Chen B, Yan Z, Lyu Q, Wang L, Kuang Y, Li B, Sang Q. Novel mutations in PATL2: expanding the mutational spectrum and corresponding phenotypic variability associated with female infertility. J Hum Genet. 2019;64:379–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campos G, Sciorio R, Esteves SC. Total fertilization failure after ICSI: insights into pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management through artificial oocyte activation. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29:369–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krausz C, Riera-Escamilla A. Genetics of male infertility. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:369–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallet-Buisan M, Mecca R, Jones C, Coward K, Yeste M. Contribution of semen to early embryo development: fertilization and beyond. Hum Reprod Update. 2023;29:395–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang M, Zeng L, Su P, Ma L, Zhang M, Zhang YZ. Autophagy: a multifaceted player in the fate of sperm. Hum Reprod Update. 2022;28:200–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunes S, Esteves SC. Role of genetics and epigenetics in male infertility. Andrologia. 2021;53:e13586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chau MHK, Li Y, Dai P, Shi M, Zhu X, Wah Chung JP, Kwok YK, Choy KW, Kong X, Dong Z. Investigation of the genetic etiology in male infertility with apparently balanced chromosomal structural rearrangements by genome sequencing. Asian J Androl. 2022;24:248–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schon SB, Luense LJ, Wang X, Bartolomei MS, Coutifaris C, Garcia BA, Berger SL. Histone modification signatures in human sperm distinguish clinical abnormalities. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Molecular reproduction & development volume 84, issue 1, January 2017. Mol Reprod Dev. 2017;84(11):C1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Zhu P, Guo H, Ren Y, Hou Y, Dong J, Li R, Lian Y, Fan X, Hu B, Gao Y, et al. Single-cell DNA methylome sequencing of human preimplantation embryos. Nat Genet. 2018;50:12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Table of contents, volume 86, issue 3, March 2019. Mol Reprod Dev. 2019;86(3):249.

- 50.Mulholland CB, Nishiyama A, Ryan J, Nakamura R, Yiğit M, Glück IM, Trummer C, Qin W, Bartoschek MD, Traube FR, et al. Recent evolution of a TET-controlled and DPPA3/STELLA-driven pathway of passive DNA demethylation in mammals. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richard Albert J, Au Yeung WK, Toriyama K, Kobayashi H, Hirasawa R. Brind’Amour J, Bogutz A, Sasaki H, Lorincz M: Maternal DNMT3A-dependent de novo methylation of the paternal genome inhibits gene expression in the early embryo. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi S, Shi Q, Sun Y. The effect of sperm miR-34c on human embryonic development kinetics and clinical outcomes. Life Sci. 2020;256:117895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinto S, Pereira SC, Rocha A, Barros A, Alves MG, Oliveira PF. Sperm-borne miR-34c-5p and miR-191–3p as markers for sperm motility and embryo developmental competence. Andrology 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Seyedin A, Kazeroun MH, Namipashaki A, Qobadi-Nasr S, Zamanian M, Ansari-Pour N. Association of MSY haplotype background with nonobstructive azoospermia is AZF-dependent: a case-control study. Andrologia. 2021;53:e13946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tournaye H, Krausz C, Oates RD. Concepts in diagnosis and therapy for male reproductive impairment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:554–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abur U, Gunes S, Ascı R, Altundag E, Akar OS, Ayas B, Karadag Alpaslan M, Ogur G. Chromosomal and Y-chromosome microdeletion analysis in 1,300 infertile males and the fertility outcome of patients with AZFc microdeletions. Andrologia. 2019;51:e13402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong FN, Amiri-Yekta A, Martinez G, Saut A, Tek J, Stouvenel L, Lorès P, Karaouzène T, Thierry-Mieg N, Satre V, et al. Absence of CFAP69 causes male infertility due to multiple morphological abnormalities of the flagella in human and mouse. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:636–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peer A, Atzmon Y, Aslih N, Bilgory A, Estrada D, Abu Raya YS, Shalom-Paz E. Male genome influences embryonic development as early as pronuclear stage. Andrology. 2022;10:525–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wyrwoll MJ, Temel ŞG, Nagirnaja L, Oud MS, Lopes AM, van der Heijden GW, Heald JS, Rotte N, Wistuba J, Wöste M, et al. Bi-allelic mutations in M1AP are a frequent cause of meiotic arrest and severely impaired spermatogenesis leading to male infertility. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;107:342–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y, Tang J, Wang X, Sun Y, Yang T, Shen X, Yang X, Shi H, Sun X, Xin A. Loss of ACTL7A causes small head sperm by defective acrosome-acroplaxome-manchette complex. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2023;21:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xin A, Qu R, Chen G, Zhang L, Chen J, Tao C, Fu J, Tang J, Ru Y, Chen Y, et al. Disruption in ACTL7A causes acrosomal ultrastructural defects in human and mouse sperm as a novel male factor inducing early embryonic arrest. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshida K, Muratani M, Araki H, Miura F, Suzuki T, Dohmae N, Katou Y, Shirahige K, Ito T, Ishii S. Mapping of histone-binding sites in histone replacement-completed spermatozoa. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dorostghoal M, Kazeminejad SR, Shahbazian N, Pourmehdi M, Jabbari A. Oxidative stress status and sperm DNA fragmentation in fertile and infertile men. Andrologia. 2017;49:e12762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Middelkamp S, van Tol HTA, Spierings DCJ, Boymans S, Guryev V, Roelen BAJ, Lansdorp PM, Cuppen E, Kuijk EW. Sperm DNA damage causes genomic instability in early embryonic development. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz7602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ben Maamar M, Sadler-Riggleman I, Beck D, McBirney M, Nilsson E, Klukovich R, Xie Y, Tang C, Yan W, Skinner MK, Faulk C. Alterations in sperm DNA methylation, non-coding RNA expression, and histone retention mediate vinclozolin-induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of disease. Environ Epigenetics. 2018;4(2):dvy010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng X, Li Z, Wang G, Wang H, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Cheng CY, Qiao Y, Sun F. Sperm epigenetic alterations contribute to inter- and transgenerational effects of paternal exposure to long-term psychological stress via evading offspring embryonic reprogramming. Cell Discovery. 2021;7(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang Q, Lin J, Liu M, Li R, Tian B, Zhang X, Xu B, Liu M, Zhang X, Li Y, Shi H, Wu L. Highly sensitive sequencing reveals dynamic modifications and activities of small RNAs in mouse oocytes and early embryos. Sci Adv. 2016;2(6):e1501482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Wang ZD, Duan L, Zhang ZH, Song SH, Bai GY, Zhang N, Shen XH, Shen JL, Lei L. Methyl-CpG–binding protein 2 improves the development of mouse somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos. Cell Reprogram. 2016;18(2):78–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Asami M, Lam BYH, Ma MK, Rainbow K, Braun S, VerMilyea MD, Yeo GSH, Perry ACF. Human embryonic genome activation initiates at the one-cell stage. Cell Stem Cell. 2022;29:209-216.e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morita K, Hatanaka Y, Ihashi S, Asano M, Miyamoto K, Matsumoto K. Symmetrically dimethylated histone H3R2 promotes global transcription during minor zygotic genome activation in mouse pronuclei. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1):10146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vastenhouw NL. Cao WX. Lipshitz HD: The maternal-to-zygotic transition revisited. Development; 2019. p. 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zou Z, Zhang C, Wang Q, Hou Z, Xiong Z, Kong F, Wang Q, Song J, Liu B, Liu B, et al. Translatome and transcriptome co-profiling reveals a role of TPRXs in human zygotic genome activation. Science. 2022;378:abo7923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Desai NN, Goldstein J, Rowland DY, Goldfarb JM. Morphological evaluation of human embryos and derivation of an embryo quality scoring system specific for day 3 embryos: a preliminary study. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(10:2190–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Pelinck MJ, De Vos M, Dekens M, Van der Elst J, De Sutter P, Dhont M. Embryos cultured in vitro with multinucleated blastomeres have poor implantation potential in human in-vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(4):960–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Alikani M, Cohen J, Tomkin G, Garrisi GJ, Mack C, Scott RT. Human embryo fragmentation in vitro and its implications for pregnancy and implantation. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:836–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.De Iaco A, Coudray A, Duc J, Trono D. DPPA2 and DPPA4 are necessary to establish a 2C-like state in mouse embryonic stem cells. EMBO Rep. 2019;20(5):e47382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eckersley-Maslin M, Alda-Catalinas C, Blotenburg M, Kreibich E, Krueger C, Reik W. Dppa2 and Dppa4 directly regulate the Dux-driven zygotic transcriptional program. Genes Dev. 2019;33:194–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jiang X, Cai J, Liu L, Liu Z, Wang W, Chen J, Yang C, Geng J, Ma C, Ren J. Does conventional morphological evaluation still play a role in predicting blastocyst formation? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2022;20(1):68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Foley EA, Kapoor TM. Microtubule attachment and spindle assembly checkpoint signalling at the kinetochore. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lara-Gonzalez P, Westhorpe FG, Taylor SS. The spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R966-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.London N, Biggins S. Signalling dynamics in the spindle checkpoint response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:736–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Santaguida S, Amon A. Short- and long-term effects of chromosome mis-segregation and aneuploidy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:473–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chang L, Barford D. Insights into the anaphase-promoting complex: a molecular machine that regulates mitosis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;29:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Primorac I, Musacchio A. Panta rhei: the APC/C at steady state. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:177–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Musacchio A. The molecular biology of spindle assembly checkpoint signaling dynamics. Curr Biol. 2015;25:R1002–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Singla S, Iwamoto-Stohl LK, Zhu M, Zernicka-Goetz M. Autophagy-mediated apoptosis eliminates aneuploid cells in a mouse model of chromosome mosaicism. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Palmerola KL, Amrane S, De Los AA, Xu S, Wang N, de Pinho J, Zuccaro MV, Taglialatela A, Massey DJ, Turocy J, et al. Replication stress impairs chromosome segregation and preimplantation development in human embryos. Cell. 2022;185:2988-3007.e2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Radonova L, Svobodova T, Anger M. Regulation of the cell cycle in early mammalian embryos and its clinical implications. Int J Dev Biol. 2019;63:113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jacobs K, Van de Velde H, De Paepe C, Sermon K, Spits C. Mitotic spindle disruption in human preimplantation embryos activates the spindle assembly checkpoint but not apoptosis until Day 5 of development. MHR: Basic Sci Reprod Med. 2017;23:321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kermi C. Aze A. Maiorano D: Preserving genome integrity during the early embryonic DNA replication cycles. Genes; 2019. p. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Regin M, Spits C, Sermon K. On the origins and fate of chromosomal abnormalities in human preimplantation embryos: an unsolved riddle. Mol Human Reprod. 2022;28(4):gaac011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gao L, Zhang Z, Zheng X, Wang F, Deng Y, Zhang Q, Wang G, Zhang Y, Liu X. The novel role of Zfp296 in mammalian embryonic genome activation as an H3K9me3 modulator. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(14):11377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang Q, Lin J, Liu M, Li R, Tian B, Zhang X, Xu B, Liu M, Zhang X, Li Y, et al. Highly sensitive sequencing reveals dynamic modifications and activities of small RNAs in mouse oocytes and early embryos. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1501482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Redó-Riveiro A, Al-Mousawi J, Linneberg-Agerholm M, Proks M, Perera M, Salehin N, Brickman JM. Transcription factor co-expression mediates lineage priming for embryonic and extra-embryonic differentiation. Stem Cell Rep. 2024;19:174–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ferguson-Smith AC. Genomic imprinting: the emergence of an epigenetic paradigm. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:565–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]