Abstract

Summary

Hip fracture is a public health problem recognized worldwide and a potentially catastrophic threat for older persons, even carrying a demonstrated excess of mortality. Handgrip strength (HGS) has been identified as a predictor of different outcomes (mainly mortality and disability) in several groups with hip fracture.

Purpose

The aim of this study was to determine the association between low HGS and 1-year mortality in a cohort of older patients over 60 years old with fragility hip fractures who underwent surgery in the Colombian Andes Mountains.

Methods

A total of 126 patients (median age 81 years, women 77%) with a fragility hip fracture during 2019–2020 were admitted to a tertiary care hospital. HGS was measured using dynamometry upon admission, and data about sociodemographic, clinical and functional, laboratory, and surgical intervention variables were collected. They were followed up until discharge. Those who survived were contacted by telephone at one, three, and 12 months. Bivariate, multivariate, and Kaplan–Meier analyses with survival curves were performed.

Results

The prevalence of low HGS in the cohort was 71.4%, and these patients were older, had poorer functional and cognitive status, higher comorbidity, higher surgical risk, time from admission to surgery > 72 h, lower hemoglobin and albumin values, and greater intra-hospital mortality at one and three months (all p < 0.01). Mortality at one year in in patients with low HGS was 42.2% and 8.3% in those with normal HGS, with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.000). In the multivariate analysis, low HGS and dependent gait measured by Functional Ambulation Classification (FAC) were the factors affecting postoperative 1-year mortality in older adults with hip fractures.

Conclusion

In this study of older people with fragility hip fractures, low HGS and dependent gait were independent predictive markers of 1-year mortality.

Keywords: Aging, Colombia, Handgrip strength, Hip fracture, Mortality, Older persons

Introduction

Hip fracture is a clinical event that is considered a public health problem worldwide [1]. It also critically impacts the mortality, morbidity, quality of life, and disability of those affected [2, 3], as well as at the social level, due to the costs they entail for health systems and the associated disability [4]. The prognosis for older persons after a hip fracture is poor. The consequences from the functional perspective are also devastating, presenting a higher rate of disability and institutionalization [5]. The 1-year mortality in older people with hip fractures ranges from 15 to 36% [6], with rates that are 3–4 times higher than the general population [7].

Multiple studies have tackled the risk factors influencing short- and long-term mortality in patients with hip fractures. A recent meta-analysis of 18 studies demonstrated that older age, male gender, cognitive impairment, psychiatric disorders (delirium, dementia, and depression), living with a caregiver, two and three comorbidities, cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and malignancy were associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality in these patients [8]. More recently, highly prevalent geriatric conditions like frailty and sarcopenia have emerged as prognostic factors [9, 10].

The concept of sarcopenia has evolved over the years: it does not only include low muscle mass but also muscle function, as a variable that has been demonstrated to impact clinical outcomes [11]. The component of muscular function can be defined through strength, power, or performance [12]. Consequently, some authors have used the term dynapenia as the loss of muscle strength associated with age and not caused by neurological or muscular diseases [13]. Recently, the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO), a working group on frailty and sarcopenia, recommended the use of handgrip strength (HGS) to measure muscle strength [14].

HGS has been associated with various clinical outcomes in diverse populations, mainly with mortality and disability [15]. It has been identified as a mortality predictor in patients with cardiovascular disease [16], mortality in patients in chronic hemodialysis [17], and neurotoxicity induced by chemotherapy in patients with digestive cancer [18], among others. Regarding hip fractures, various studies have recognized its value as a predictor of functional recovery after the surgical intervention [19–22], development of pressure ulcers [23, 24], and recently, mortality after one year in Spanish [25], Mexican [26], and Taiwanese [27, 28] older adults.

HGS as a marker of muscle strength, which requires only the measurement using dynamometry and could be done at the patient’s bedside, surges as an option to identify the population at high risk of functional consequences and mortality. This might allow establishing intervention and prevention strategies in patients with hip fractures. This study aimed to determine the association between low HGS and 1-year mortality in a cohort of older patients with fragility hip fractures who underwent surgery in a tertiary care hospital in the city of Manizales, Colombia, in the Andes Mountains.

Materials and methods

Study design

An observational, analytical, longitudinal, and prospective study was performed in a tertiary hospital in Manizales, located in the Colombian Andes Mountains region, from May 2019 to May 2020. The inclusion criteria were older patients (60 years and older) diagnosed with a fragility hip fracture, who were previously ambulatory, and who had at least a 1-year postoperative follow-up if they survived. Patients with high-energy trauma (such as traffic accidents), pathological fractures, those who underwent resection arthroplasty (Girdlestone), who did not undergo surgery, who did not sign the informed consent form, or who were unable to follow dynamometry directions (mainly because of advanced cognitive impairment, severe sensory deprivation or injury in the dominant hand) were excluded. All patients were evaluated within 48 h of admission and always before surgery. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their proxies, and the local ethics committee of the hospital approved the study.

Measurement of handgrip strength

Isometric grip strength, which is the maximum handgrip strength, was measured using a Takey Grip-A hydraulic dynamometer (Takei Scientific Instruments Co., Tokyo, Japan). Participants were instructed and verbally encouraged to grip the handle as hard as possible three times using their dominant hand [29]. Handgrip strength was obtained within 48 h after arrival at the hospital, which minimized the bias due to loss of strength related to bed rest. A handgrip strength of < 16 kg/F for women and < 27 kg/F for men was considered low, based on the threshold values recommended by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) [30].

Measurement of other clinical parameters

The sociodemographic data, fracture-related characteristics, and preoperative and postoperative clinical variables from medical charts and caregivers were collected for participants who met the inclusion criteria. The sociodemographic variables were age, gender, type of residence (urban or rural), health care affiliation (contributive scheme for formal workers and subsidized scheme for those without the ability to pay), and marital status (married, widowed, or single). The fracture-related variables included the type of fracture (extracapsular fractures such as intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures; intracapsular fractures such as femoral neck fractures and periprosthetic fractures) [31], with distinctions between the four types of fractures made through X-rays by orthopedic surgeons. The time from admission to surgery was also considered. Concerning the preoperative clinical variables, comorbidity was measured by the total number of self-reported physician-diagnosed chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, hypothyroidism, cognitive impairment, osteoporosis, lung diseases, psychiatric diseases, chronic kidney disease, and stroke). The Charlson comorbidity index score was determined.

Other preoperative variables obtained were the Functional Ambulation Classification (FAC) gait scale score, the New York Heart Association functional class (NYHA), and the surgical risk according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scale. For physical performance, we used the Barthel scale, and the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) was applied for nutritional status. Screening for cognitive impairment was determined by the revised version of the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and Depressive symptoms were measured using the 15-question version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). The laboratory preoperative clinical variables obtained were hemoglobin (cutoff 12 g/dL in women and 13 g/dL in men), calcium (normal value 8.5–10.1 mg/dL, corrected by albumin), phosphorus (normal value 2.5–4.5 mg/dL), 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (deficiency ≤ 20 ng/mL, insufficiency 21–29 ng/mL), parathormone (normal value 14.5–128 pg/mL), and albumin (normal value 3.5–5 g/dL).

Survival was recorded during hospitalization and at one, three, and 12 months. The information on death and its date were obtained through telephone contact or health insurance database.

Statistical analysis

The normality of quantitative variables was analyzed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; non-normality was accepted with p < 0.05. All variables were compared between the two groups (low and normal HGS). Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviations (SD), with an independent t-test performed to compare the differences between the two referred groups. To compare discrete variables, the chi-squared test (χ2) was used. When the expected value was less than five in one of the squares of the contingency table, Fisher’s exact test was used. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages, with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for comparisons, as was appropriate. The Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test was performed to compare the differences in mean survival time. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were performed to investigate which factors were associated with 1-year survival. Factors that had a significant association with survival were included in the multivariate analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical version 25.0 for macOS (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Values of p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

We evaluated a total of 132 patients over 60 years old who had a fragility hip fracture during the preoperatory. We excluded six patients (4.5%) since, due to various reasons, they were not taken to surgical management (decision by Orthopedics, or death prior to the intervention), or they were unable to perform the maneuver due to lack of comprehension, cognitive impairment, or an injury in the dominant hand, which left 126 people. The established follow-up plan was completed until month 12 in 124 participants; the other two were recorded as alive, according to the health insurance database. Their characteristics are presented in Table 1. The age median was 81 (60–99) years, and 97 (77%) were female. The most common type of fracture was extracapsular fracture (intertrochanteric fracture in 71.4%), followed by intracapsular fracture (basicervical fracture in 16.7%). Differences between the presence of low HGS regarding the time of surgery were found (5 vs. 3 days, p = 0.002). A median Charlson comorbidity index score of four was found, and hypertension was the most prevalent chronic disease (66%), followed by diabetes mellitus (30%), dyslipidemia (24%), osteoarthrosis (24.6%), and cognitive impairment (17.5%); the prevalence of osteoarthritis may have been underestimated.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics according to the presence of dynapenia

| Total | Handgrip strength | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | (n = 126) | Low (n = 90) | Normal (n = 36) | p-valuea |

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age, median (range), years | 81 (60–99) | 82 (62–95) | 75.5 (60–92) | 0.010* |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 97 (77) | 68 (75.6) | 29 (80.6) | 0.547 |

| Male | 29 (23) | 22 (24.4) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Residence, n (%) | ||||

| Urban | 75 (59.5) | 49 (54.4) | 26 (72.2) | 0.066 |

| Rural | 51 (40.5) | 41 (45.6) | 10 (27.8) | |

| Health care affiliation, n (%) | ||||

| Subsidized | 68 (54) | 47 (52.2) | 21 (58.3) | 0.698 |

| Contributive | 57 (45.2) | 42 (46.7) | 15 (41.7) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Married | 66 (52.4) | 44 (48.9) | 22 (61.1) | 0.051 |

| Widowed | 37 (29.3) | 31 (34.4) | 6 (16.7) | |

| Single | 19 (15.1) | 14 (15.6) | 5 (13.9) | |

| Fracture-related | ||||

| Type of fracture, n (%) | ||||

| Extracapsular (intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric) | 103 (81.7) | 75 (83.4) | 28 (77.8) | 0.216 |

| Intracapsular | 21 (16.7) | 13 (14.4) | 8 (22.2) | |

| Periprosthetic | 2 (1.6) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Time to surgery, mean (range), hours | 96 (24–408) | 120 (24–408) | 72 (24–240) | 0.002* |

| Preoperative clinical | ||||

| Charlson index, median (range) | 4 (2–12) | 5 (2–12) | 3 (2–6) | 0.000* |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 84 (66.7) | 66 (73.3) | 18 (50) | 0.012* |

| Diabetes | 38 (30.2) | 33 (36.7) | 5 (13.9) | 0.012* |

| Hyperlipidemia | 31 (24.6) | 26 (28.9) | 5 (13.9) | 0.077 |

| Osteoarthritis | 31 (24.6) | 29 (32.2) | 2 (5.6) | 0.002* |

| Hypothyroidism | 22 (17.5) | 17 (18.9) | 5 (13.9) | 0.504 |

| Cognitive impairment | 22 (17.5) | 21 (23.3) | 1 (2.8) | 0.06 |

| Osteoporosis | 22 (17.5) | 17 (18.9) | 5 (13.9) | 0.609 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 19 (15.1) | 15 (16.7) | 4 (11.1) | 0.431 |

| Psychiatric disease | 18 (14.3) | 17 (18.9) | 1 (2.8) | 0.020* |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16 (12.7) | 14 (15.6) | 2 (5.6) | 0.22 |

| Stroke | 5 (4) | 5 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 0.348 |

| Functional Ambulation Classification, n (%) | ||||

| Independent (4–5) | 99 (78) | 64 (71.1) | 35 (97.2) | 0.001* |

| Dependent (0–3) | 27 (21.3) | 26 (28.9) | 1 (2.8) | |

| Functional Class (NYHA), n (%) | ||||

| I | 41 (32.5) | 19 (21.1) | 22 (61.1) | 0.000* |

| II–IV | 85 (67.5) | 71 (78.9) | 14 (38.9) | |

| ASA Physical Status Classification, n (%) | ||||

| I–II | 67 (53.2) | 38 (42.2) | 29 (80.6) | 0.000* |

| III–IV | 59 (46.8) | 52 (57.8) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) n (%) | ||||

| Positive for malnutrition | 39 (31) | 33 (36.7) | 6 (16.7) | 0.028* |

| Negative for malnutrition | 87 (69) | 57 (63.3) | 30 (83.3) | |

| Mini–Mental State Examination, n (%) | ||||

| Positive for cognitive impairment | 61 (48.4) | 53 (58.9) | 8 (22.2) | 0.000* |

| Negative for cognitive impairment | 65 (51.6) | 37 (41.1) | 28 (77.8) | |

| Barthel index, median (range) | 100 (5–100) | 90 (5–100) | 100 (55–100) | 0.000* |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) n (%) | ||||

| Positive for depression | 15 (11.9) | 13 (14.4) | 2 (5.6) | 0.228 |

| Negative for depression | 111 (88.1) | 77 (85.6) | 34 (94.4) | |

| Laboratory variables | ||||

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD), g/dL | 11.8 (1.95) | 11.4 (2.01) | 12.8 (1.90) | 0.049* |

| Calcium, median (range), mg/dL | 8.6 (6.8–10.2) | 8.6 (6.8–10.2) | 8.7 (7.9–9.2) | 0.986 |

| Phosphorus, mean (SD), mg/dL | 3.66 (0.76) | 3.7 (0.80) | 3.4 (0.77) | 0.262 |

| Albumin, mean (SD), g/dL | 3.46 (0.46) | 3.3 (0.45) | 3.5 (0.37) | 0.016* |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3, median (range), ng/mL | 19.7 (4–78.7) | 18.6 (4–75.7) | 22.4 (6.9–77) | 0.153 |

| Parathormone, median (range), pg/ml | 57.56 (12.6–819) | 59.6 (12.6–819) | 51.4 (18.5–148.2) | 0.182 |

aAssociation between dynapenia, yes and no

*Statistically significant difference

FAC, Functional Ambulation Classification; NYHA, New York Heart Association; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale

We found that 28 (22%) had a history of prior fragility fractures: hip eight (6.3%), radius-ulna six (4.8%), humerus five (4%), tibia-fibula three (2.4%), and vertebral two (1.6%); four (3.2%) patients had had more than one. Despite this, 22 (17.5%) patients had an osteoporosis diagnosis, 16 (12.7%) had been evaluated using bone densitometry. Regarding laboratory values, 70 (55.6%) had hemoglobin levels of 12 g/dL or less, 63 (50%) had vitamin D levels of 20 ng/mL or less, and 71 (56.3%) had albumin levels of less than 3.5 g/dL.

In total, 90 (71.4%) had low HGS with a median of 13 (3–35) kg/F. When discriminating by gender, 22 were male (75.9% of the male participants), with a median of 18 (range 6–35) kg/F, and 68 were female (70.1% of the female participants), with a median of 12 (range 3–22) kg/F. There was no statistically significant difference when comparing them. Patients with low HGS were older and had worse baseline functional and cognitive statuses. They had a higher comorbidity index, increased surgical risk, and malnutrition. Furthermore, low HGS values were associated with lower hemoglobin and albumin levels.

The bivariate analysis allowed us to identify a total of 12 predictive factors of 1-year mortality. The factors associated with 1-year mortality after surgery in patients with low HGS are as follows which are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors related to low HGS and their RR

| Characteristic | Risk ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent gait (FAC) | 14.22 | (1.85–109.28) | 0.001 |

| Barthel index < 90 | 13 | (2.94–57.43) | 0.000 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 8.15 | (1.04–63.73) | 0.022 |

| Osteoarthritis | 8.08 | (1.81–35.96) | 0.002 |

| Charlson comorbidity index score > 3 | 6.4 | (2.52–16.21) | 0.000 |

| Functional class (NYHA) III–IV | 5.87 | (2.53–13.61) | 0.000 |

| High surgical risk (scale ASA ≥ III) | 5.67 | (2.24–14.30) | 0.000 |

| Cognitive impairment | 5.01 | (2.05–12.21) | 0.000 |

| Hemoglobin level ≤ 10 g/dL | 4.86 | (1.07–21.99) | 0.036 |

| Albumin ≤ 3,3 g/dL | 4.74 | (1.67–13.35) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.59 | (1.27–10.12) | 0.012 |

| Time from admission to surgery > 72 h | 2.86 | (1.124–7.277) | 0.039 |

At the 1-year follow-up after surgery, 41 patients (32.5%) had died. When comparing the occurrence of death between patients with low and normal HGS, statistically significant differences were found (Table 3). In-hospital mortality in patients with low HGS reached 17.8%, 1-month mortality reached 28.9%, and 3-month mortality reached 35.6%. Mortality rates were higher for the low HGS group than those with normal HGS for in-hospital, 30-day, 3-month, and 12-month mortality with significant differences.

Table 3.

Mortality according to handgrip strength

| Total | Handgrip strength | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality, n (%) | (n = 126) | Low (n = 90) | Normal (n = 36) | p-value |

| In-hospital | 16 (12.7) | 16 (17.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.016 |

| 1 month | 26 (20.6) | 26 (28.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 |

| 3 months | 33 (26.2) | 32 (35.6) | 1 (2.8) | 0.000 |

| 12 months | 41 (32.5) | 38 (42.2) | 3 (8.3) | 0.000 |

Lastly, we carried out a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis using Wald’s equation, in which we included vital status at 12 months as a dependent variable and those with statistical significance identified in the bivariate analysis as covariables. From the model, two variables with statistical significance were obtained: low HGS and dependent gait according to the FAC scale (Table 4), with 90.4% specificity, 45% sensitivity, and a global percentage to predict the result of 75.6%.

Table 4.

Results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis

| Death at 12 months | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | p | OR | 95% CI |

| Low HGS | 0.015 | 4.96 | (1.359–18.084) |

| Dependent gait by FAC | 0.001 | 4.83 | (1.848–12.610) |

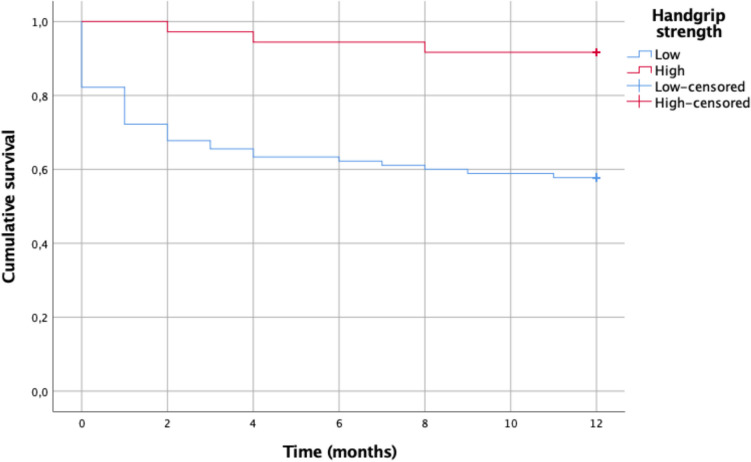

Cumulative survival for fragility hip fracture patients in the low HGS group was lower (Fig. 1). A statistically significant difference was seen between low and normal HGS patients in the log-rank statistical analysis (p, 0.003) and Breslow analysis (p, 0.002).

Fig. 1.

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve shows 1-year mortality after fracture among low and normal HGS in older patients

Discussion

The results confirm the association of low HGS with 1-year mortality, in a cohort of patients with fragility hip fracture from the community. In our population-based hip fracture study, patients with low HGS (< 27 kg for men and < 16 kg for women) suffered exceptionally high mortality at 1-year follow-up after the event compared to normal HGS (42% vs. 8%, respectively). Low HGS and dependent gait measured by FAC were the factors that predicted postoperative 1-year mortality in older adults with hip fractures. The factors related to the functional status and factors related to surgery (high surgical risk, time from admission to surgery over 72 h, and a decrease in hemoglobin and albumin at admission) are the risk factors associated with mortality 1 year after surgery in patients with low HGS.

The higher mortality risk of the people with low HGS compared with normal HGS and the higher incidence of deaths during the first months after fragility hip fracture surgery revealed by our study are consistent with the results of other authors [25–28]. Our study corroborated that similar characteristics have been reported associated with low with low HGS: over 80 years old, previously institutionalized, greater gait dependence by the FAC scale, lower Barthel index, cognitive impairment, ≥ 3 Charlson index, ASA classification III–IV, malnutrition according to the BMI, anemia, and hypoalbuminemia [25, 26]. Similar to our results, Cox regression models indicated that being male, handgrip strength, long surgical delay after a falling accident, and high Charlson comorbidity index were considerably associated with a high 1-year mortality risk in the geriatric hip fracture population [27]. Our study reinforced previous findings about the significant role of HGS measurement and 1-year mortality in older people. Thus, it can be concluded that HGS could be an excellent measure to predict 1-year mortality in older adults with fragility hip fractures. Nevertheless, more research is needed to confirm our results.

HGS as an indicator of overall muscle strength, together with frailty assessment, have emerged in recent years as important predictors of poor functional consequences and mortality in patients with hip fractures. In a meta-analysis that included 34 articles, the prognostic value of HGS was evaluated with different vulnerability markers in community older adults. Regarding mortality, akin to our study, the predictive factors they found were cognitive and movement and functional status impairment. The authors suggest broadening the use of HGS in a generalized manner in older patients [32]. Subsequently, another systematic review of predictors of poor functionality and mortality in older adults with hip fracture classified the predictive factors into groups as follows: medical (comorbidities, ASA scores, sarcopenia), surgical (surgery delay, type of fracture), socioeconomic (age, gender, ethnicity), and inherent to the system (centers with a low volume of cases). Our results agree with them. Like in the previous study, in this systematic review, the authors highlight HGS as one of the emergent predictors (along with frailty), which could be used as a marker that makes early interventions in older adults with hip fractures possible [10]. Overall, our results provide additional knowledge useful for developing preventive strategies to reduce the very high mortality after hip fracture in the Andes Mountains. Thus, strategies to identify and treat medical conditions including malnutrition, anemia, and hypoalbuminemia in old people with low HGS and dependent gait should be prioritized in quality improvement efforts that target this patient population.

Furthermore, the median HGS was 13 kg/F in the present study (12 kg/F in females and 18 kg/F in male), which was much lower than the sarcopenia diagnostic criteria (< 16 kg/F in females and < 27 kg/F in males), implying a high prevalence of concomitant sarcopenia and hip fracture. Consequently, factors other than low HGS, including those found in this study, should be assessed in older people before surgical intervention to avoid the high mortality observed in this sample. In other words, older adults with hip fractures are more fragile and may thus require more healthcare resources [10]. As consequence, future studies with hip fracture patients should include a comprehensive geriatric assessment of different aspects related with medical, functional, and mental domains. It is also worth mentioning that our population has some characteristics that differ from other latitudes, including high percentage of rural precedence, high prevalence of frailty, and overall social determinants of health that contrast with those in developed countries (high multimorbidity, poverty, low education, difficult access to the healthcare system, among others) [31, 33, 34]. According to the study results and the orthogeriatric protocol applied, the main management recommendations for this population are summarized in Table 5 [1, 35–39].

Table 5.

Potential strategies of intervention in patients with low HGS

| Strategy | Action |

|---|---|

| Early CGA* | Comprehensive assessment within 24–48 h |

| Nutritional support | High-protein meals, vitamin, and mineral supplementation |

| Anemia management | Iron supplements, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, blood transfusions |

| Timely surgery | Surgery within 48 h of admission |

| Physical therapy | Early mobilization, individualized therapy programs |

| Multidisciplinary approach | Regular team meetings to adjust care plans |

| Cultural sensitivity | Respect local customs, engage family support |

| Service availability | Address transportation and financial constraints |

| Community education | Educate on nutrition, physical activity, and fall prevention |

| Policy implementation | Advocate for osteoporosis and fracture prevention policies |

*CGA, comprehensive geriatric assessment

Many strengths should be noted. One of the strengths of this study was the prospective and longitudinal design along with the 1-year follow-up that had few losses. The preoperative assessment protocol in the patients included multiple important variables in the geriatric population, which enriched the results and allowed for a better understanding of the cohort. Likewise, the statistical analysis included a multivariate component that enhanced and refined the findings, allowing us to control the effect of the other variables in regard to the association with mortality.

Some limitations to this study merit mention. First, our cohort was limited to one center, and extrapolation to a population outside this institution must be made cautiously. Second, we cannot exclude the presence of confounding factors that may affect results. As such, comorbidity conditions related to fractures are important avenues for future research to confirm their role in the evolution of hip fractures. Third, the associated factors in the study are not causal, so more studies are required to confirm what was observed. The impact of anticoagulation and hospital stay or osteoporosis previous treatment on health outcomes should also be explored.

In conclusion, fragility hip fractures have higher mortality in older people with low HGS at 1-year follow-up. The multivariate analysis proved that both low HGS and dependent gait were independent predictive factors associated with this excess mortality. Our study shows that HGS is a useful, fast, easy, and inexpensive tool as a screening test for older people with hip fractures and is highly related to increased mortality among older persons.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Colombia Consortium Open Access funding provided by Colombia Consortium.

Declarations

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Li L, Bennett-Brown K, Morgan C, Dattani R (2020) Hip fractures. Br J Hosp Med 81:1–10. 10.12968/hmed.2020.0215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orive M, Aguirre U, García-Gutiérrez S, Las Hayas C, Bilbao A, González N, Zabala J, Navarro G, Quintana JM (2015) Changes in health-related quality of life and activities of daily living after hip fracture because of a fall in elderly patients: a prospective cohort study. Int J Clin Pract 69:491–500. 10.1111/ijcp.12527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peeters CMM, Visser E, Van De Ree CLP, Gosens T, Den Oudsten BL, De Vries J (2016) Quality of life after hip fracture in the elderly: a systematic literature review. Injury 47:1369–1382. 10.1016/j.injury.2016.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caillet P, Klemm S, Ducher M, Aussem A, Schott AM (2015) Hip fracture in the elderly: a re-analysis of the EPIDOS study with causal Bayesian networks. PLoS ONE 10:1–12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrahamsen B, van Staa T, Ariely R, Olson M, Cooper C (2009) Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos Int 20:1633–1650. 10.1007/s00198-009-0920-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morri M, Ambrosi E, Chiari P, OrlandiMagli A, Gazineo D, D’ Alessandro F, Forni C (2019) One-year mortality after hip fracture surgery and prognostic factors: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 9:18718. 10.1038/s41598-019-55196-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubljanin-Raspopović E, Marković-Denić L, Marinković J, Nedeljković U, Bumbaširević M (2013) Does early functional outcome predict 1-year mortality in elderly patients with hip fracture? Clin Orthop Relat Res 471:2703–2710. 10.1007/s11999-013-2955-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Wang Z, Xiao W (2018) Risk factors for mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures: a meta-analysis of 18 studies. Aging Clin Exp Res 30:323–330. 10.1007/s40520-017-0789-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayama A, Olorunfemi O, Greenbaum S, Stone ME, McNelis J (2016) Impact of frailty on outcomes in geriatric femoral neck fracture management: an analysis of national surgical quality improvement program dataset. Int J Surg 28:185–190. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.02.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu BY, Yan S, Low LL, Vasanwala FF, Low SG (2019) Predictors of poor functional outcomes and mortality in patients with hip fracture: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20:1–9. 10.1186/s12891-019-2950-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong W, Cheng Q, Zhu X, Zhu H, Li H, Zhang X, Zheng S, Du Y, Tang W, Xue S, Ye Z (2015) Prevalence of sarcopenia and its relationship with sites of fragility fractures in elderly Chinese men and women. PLoS ONE 10:1–10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira A, Vaz C (2015) The role of sarcopenia in the risk of osteoporotic hip fracture. Clin Rheumatol 34:1673–1680. 10.1007/s10067-015-2943-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark BC, Manini TM (2012) What is dynapenia? Nutrition 28:495–503. 10.1016/j.nut.2011.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaudart C, Rolland Y, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bauer JM, Sieber C, Cooper C, Al-Daghri N, Araujo de Carvalho I, Bautmans I, Bernabei R, Bruyère O, Cesari M, Cherubini A, Dawson-Hughes B, Kanis JA, Kaufman J-M, Landi F, Maggi S, McCloskey E, Petermans J, Rodriguez Mañas L, Reginster J-Y, Roller-Wirnsberger R, Schaap LA, Uebelhart D, Rizzoli R, Fielding RA (2019) Assessment of muscle function and physical performance in daily clinical practice. Calcif Tissue Int 105:1–14. 10.1007/s00223-019-00545-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark BC, Manini TM (2010) Functional consequences of sarcopenia and dynapenia in the elderly. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 13:271–276. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328337819e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchida S, Kamiya K, Hamazaki N, Nozaki K, Ichikawa T, Nakamura T, Yamashita M, Maekawa E, Reed JL, Yamaoka-Tojo M, Matsunaga A, Ako J (2021) Prognostic utility of dynapenia in patients with cardiovascular disease. Clin Nutr 40:2210–2218. 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souweine J-S, Pasquier G, Kuster N, Rodriguez A, Patrier L, Morena M, Badia E, Raynaud F, Chalabi L, Raynal N, Ohresser I, Hayot M, Mercier J, Quintrec M Le, Gouzi F, Cristol J-P (2020) Dynapaenia and sarcopaenia in chronic haemodialysis patients: do muscle weakness and atrophy similarly influence poor outcome? Nephrol Dial Transplant:1–11. 10.1093/ndt/gfaa353 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Botsen D, Ordan MA, Barbe C, Mazza C, Perrier M, Moreau J, Brasseur M, Renard Y, Taillière B, Slimano F, Bertin E, Bouché O (2018) Dynapenia could predict chemotherapy-induced dose-limiting neurotoxicity in digestive cancer patients. BMC Cancer 18:1–9. 10.1186/s12885-018-4860-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selakovic I, Dubljanin-Raspopovic E, Markovic-Denic L, Marusic V, Cirkovic A, Kadija M, Tomanovic-Vujadinovic S, Tulic G (2019) Can early assessment of hand grip strength in older hip fracture patients predict functional outcome? PLoS ONE 14:1–10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C, De Toma E, Gardin L, Giordano S, Di Monaco R, Tappero R (2014) Handgrip strength but not appendicular lean mass is an independent predictor of functional outcome in hip-fracture women: a short-term prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 95:1719–1724. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C, De Toma E, Gardin L, Giordano S, Tappero R (2015) Handgrip strength is an independent predictor of functional outcome in hip-fracture women: a prospective study with 6-month follow-up. Med (United States) 94:1–6. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savino E, Martini E, Lauretani F, Pioli G, Zagatti AM, Frondini C, Pellicciotti F, Giordano A, Ferrari A, Nardelli A, Davoli ML, Zurlo A, Lunardelli ML, Volpato S (2013) Handgrip strength predicts persistent walking recovery after hip fracture surgery. Am J Med 126:1068-1075.e1. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gumieiro DN, Rafacho BPM, Gradella LM, Azevedo PS, Gaspardo D, Zornoff LAM, Pereira GJC, Paiva SAR, Minicucci MF (2012) Handgrip strength predicts pressure ulcers in patients with hip fractures. Nutrition 28:874–878. 10.1016/j.nut.2011.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez EDDL, Mendivil LLL, Garza DPS, Hermosillo HG, Chavez JHM, Corona RP (2018) Low handgrip strength is associated with a higher incidence of pressure ulcers in hip fractured patients. Acta Orthop Belg 84:284–291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Rodríguez P, Rabes-Rodríguez L, Sáez-Nieto C, Alarcón TA, Queipo R, Otero-Puime Á, Gonzalez Montalvo JI (2020) Handgrip strength predicts 1-year functional recovery and mortality in hip fracture patients. Maturitas 141:20–25. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutiérrez-Hermosillo H, de León-González ED, Medina-Chávez JH, Torres-Naranjo F, Martínez-Cordero C, Ferrari S (2020) Hand grip strength and early mortality after hip fracture. Arch Osteoporos 15:185. 10.1007/s11657-020-00750-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y-P, Kuo Y-J, Liu C, Chien P-C, Chang W-C, Lin C-Y, Pakpour AH (2021) Prognostic factors for 1-year functional outcome, quality of life, care demands, and mortality after surgery in Taiwanese geriatric patients with a hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 13:1759720X2110283. 10.1177/1759720X211028360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiang M-H, Huang Y-Y, Kuo Y-J, Huang S-W, Jang Y-C, Chu F-L, Chen Y-P (2022) Prognostic factors for mortality, activity of daily living, and quality of life in taiwanese older patients within 1 year following hip fracture surgery. J Pers Med 12:102. 10.3390/jpm12010102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts HC, Denison HJ, Martin HJ, Patel HP, Syddall H, Cooper C, Sayer AA (2011) A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing 40:423–429. 10.1093/ageing/afr051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Visser M, Zamboni M, Bautmans I, Baeyens JP, Cesari M, Cherubini A, Kanis J, Maggio M, Martin F, Michel JP, Pitkala K, Reginster JY, Rizzoli R, Sánchez-Rodríguez D, Schols J (2019) Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48:16–31. 10.1093/ageing/afy169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duque-Sánchez JD, Toro LÁ, González-Gómez FI, Botero-Baena SM, Duque G, Gómez F (2022) One-year mortality after hip fracture surgery: urban–rural differences in the Colombian Andes. Arch Osteoporos 17:111. 10.1007/s11657-022-01150-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rijk JM, Roos PRKM, Deckx L, Van den Akker M, Buntinx F (2016) Prognostic value of handgrip strength in people aged 60 years and older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr Gerontol Int 16:5–20. 10.1111/ggi.12508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curcio CL, Henao GM, Gomez F (2014) Frailty among rural elderly adults. BMC Geriatr 14:2. 10.1186/1471-2318-14-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.República de Colombia, Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (2016) Encuesta SABE Colombia: situación de Salud, Bienestar y Envejecimiento en Colombia. Colciencias. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/ED/GCFI/Resumen-Ejecutivo-Encuesta-SABE.pdf. Accessed 01-02-2024

- 35.Prestmo A, Hagen G, Sletvold O, Helbostad JL, Thingstad P, Taraldsen K, Lydersen S, Halsteinli V, Saltnes T, Lamb SE, Johnsen LG, Saltvedt I (2015) Comprehensive geriatric care for patients with hip fractures: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet (Lond, Engl) 385(9978):1623–1633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoue T, Maeda K, Nagano A, Shimizu A, Ueshima J, Murotani K, Sato K, Tsubaki A (2020) Undernutrition, sarcopenia, and frailty in fragility hip fracture: advanced strategies for improving clinical outcomes. Nutrients 12(12):3743. 10.3390/nu12123743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang Y, Lin X, Wang Y, Li J, Wang G, Meng Y, Li M, Li Y, Luo Y, Gao Z, Yin P, Zhang L, Lyu H, Tang P (2023) Preoperative anemia and risk of in-hospital postoperative complications in patients with hip fracture. Clin Interv Aging 18:639–653. 10.2147/CIA.S404211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller MM, Van Remoortel H, Meybohm P, Aranko K, Aubron C, Burger R, Carson JL, Cichutek K, De Buck E, Devine D, Fergusson D, Folléa G, French C, Frey KP, Gammon R, Levy JH, Murphy MF, Ozier Y, Pavenski K, So-Osman C, …, ICC PBM Frankfurt 2018 Group (2019) Patient blood management: recommendations from the 2018 Frankfurt Consensus Conference. JAMA 321(10):983–997. 10.1001/jama.2019.0554 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.McDonough CM, Harris-Hayes M, Kristensen MT, Overgaard JA, Herring TB, Kenny AM, Mangione KK (2021) Physical therapy management of older adults with hip fracture. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 51(2):CPG1–CPG81. 10.2519/jospt.2021.0301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]