By making CAR-T cells' cytotoxicity contingent on two-step target cell identification by CD33 then CD133 antigens, IF-THEN logical SynNotch circuit limits toxicity and exhaustion while preserving cytotoxicity against AML.

Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has remarkably succeeded in treating lymphoblastic leukemia. However, its success in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remains elusive because of the risk of on-target off-tumor toxicity to hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPC) and insufficient T-cell persistence and longevity. Using a SynNotch circuit, we generated a high-precision “IF-THEN” gated logical circuit against the combination of CD33 and CD123 AML antigens and demonstrated antitumor efficacy against AML cell lines and patient-derived xenografts. Unlike constitutively expressed CD123 CAR-T cells, those expressed through the CD33 SynNotch circuit could preserve HSPCs and lower the risk of on-target off-tumor hematopoietic toxicity. These gated CAR-T cells exhibited lower expression of exhaustion markers (PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3, and CD39), higher frequency of memory T cells (CD62L+CD45RA+), and enhanced expansion. Although targeting AML, the moderated circuit CAR signal also helped mitigate cytokine release syndrome, potentially addressing one of the ongoing challenges in CAR-T immunotherapy.

Significance:

Our study demonstrates the use of “IF-THEN” SynNotch-gated CAR-T cells targeting CD33 and CD123 in AML reduces off-tumor toxicity. This strategy enhances T-cell phenotype, improves expansion, preserves HSPCs, and mitigates cytokine release syndrome—addressing critical limitations of existing AML CAR-T therapies.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most prevalent acute leukemia in adults and the second most common in children, carrying a poor prognosis for patients with refractory or relapsed disease (1). CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has revolutionized treatment options for patients with chemorefractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; however, the success of CAR-T immunotherapy for AML is yet to be realized.

In AML, antitumor efficacy is often accompanied by hematopoietic toxicity because of the overlap in antigen expression within the hematopoietic system (2–4). CD33 is expressed in up to 90% of AML cells and on AML progenitors and has, therefore, been exploited as a target for therapeutic antibodies for many years. The anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody–drug conjugate, gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO), was first added to conventional chemotherapy to improve treatment efficacy (5–7). CD33 CAR-T cells engineered using GO single-chain variable fragment (scFv) showed lasting disease reduction up to 9 weeks after infusion (8–10). Following reports of liver disease from GO, CD33 CAR-T efforts slowed until recently when a few other studies using CD33 CAR-T cells with additional safety switches began recruiting patients (11, 12). Unfortunately, one of these trials was complicated recently by at least one fatal event when this article was being prepared, suggesting ongoing safety concerns for CD33 targeting CAR-T cells. Another well-known target of AML, CD123, is also widely expressed in most AML blasts with lower expression levels on normal hematopoietic cells (13–15). A constitutively expressed second generation of CAR-T cells targeting CD123 led to a marked reduction in myeloid colony formation, suggesting even the lower CD123 expression in donor hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSPC) is still sufficient to activate constitutively expressed CD123 CAR-T cells (16).

Recent advancements in synthetic biology and immune cell engineering have facilitated the integration of combinatorial antigen-sensing functionalities into therapeutic T-cell modalities (17–20). Leveraging SynNotch technology, originally developed in Lim’s laboratory, we designed the first effective and clinically relevant combinatorial targeting strategy, enabling customized gene regulation in response to disease-specific antigens (21). SynNotch receptors can be engineered to sense a tumor antigen and subsequently initiate the transcription of a CAR targeting a second tumor-related antigen. This inducible SynNotch CAR circuitry spatially restricts CAR expression, consequently confining T-cell activation to the disease site (21–23).

To develop an AML CAR-T strategy that addresses the toxicity concerns of using constitutively expressed AML CARs, we used the SynNotch system to engineer a logical circuit against the combination of CD33 and CD123 (17–23). These “IF–THEN” gated CAR-T cells efficiently eliminated AML disease in preclinical models without hematopoietic toxicity. We also show that gated expression of SynNotch CAR and its dampened tonic signaling maintains memory and nonexhausted T-cell phenotype. Additionally, we discovered that in humanized AML murine model, the SynNotch CAR circuit affects the cross-talk between human and mouse cells and diminishes the risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS).

Results

AML Can Be Targeted Using SynNotch CAR-T Cells

We first generated 4-1BB/CD3ζ-based second-generation (BBz) CAR-T cells targeting the abundant AML antigens CD123 and CD33 from publicly available scFvs (Supplementary Fig. S1A and S1B). To localize CAR expression specifically to AML cells, we engineered combinatorial gated CARs with SynNotch receptors targeting AML antigens CD33 and CD123, aiming to identify the superior circuit that would be able to selectively drive expression of the respective CARs when stimulated with AML cells expressing both antigens (Supplementary Fig. S1A and S1B). We then evaluated the “on” kinetics for these circuits in coculture with those AML cell lines; CD33 SynNotch was far more effective than CD123 in regulating BFP expression (Supplementary Fig. S2). Further optimizing the spacer between scFv and Notch core with CH2–CH3 improved the gate activation for the CD33 SynNotch sensor but caused unacceptable increased leaky expression and did not significantly improve cytotoxicity (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3A–S3C).

Knowing that CD33 SynNotch receptor and CD123-BBz formed the superior combination, we focused on CD33→CD123 (“IF–THEN” gate CAR) SynNotch Circuit for the most effective candidate against AML in which CD33-sensing SynNotch receptor drives the expression of CD123-BBz, killing AML cells (Fig. 1A). Both constitutively expressed CD123 and SynNotch CD33→CD123 CAR-T cells eliminate AML in culture at a low effector to target (E:T) ratio of 1:1 and 1:2 (Fig. 1B). We then evaluated the cytokine production of SynNotch-gated in comparison with constitutively expressed CAR-T cells, focusing on IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α. CD33→CD123 SynNotch CAR-T cells were comparable with CD123 CAR-T cells in their cytokine profile (Fig. 1C). To verify the efficacy of the CD33→CD123 gated CAR circuit, we then used two AML cell lines (MOLM13 and KG1) to establish AML disease in NOD/SCID gamma (NSG) mice. Animals received an intravenous injection of 1 × 106 of AML cells followed 7 days later by engineered T cells to constitutively express CD123 CAR, or CD33→CD123 gated CAR circuit, compared with untransduced T cells as control. Both constitutively expressed and gated CAR-T cells show disease control (Fig. 1D and E; Supplementary Figs. S4A, S4B, and S5A). However, mice treated with CD33→CD123 had more prolonged survival and a significantly higher number of T cells in the peripheral blood of mice 2 weeks after CAR-T treatment, suggesting superior expansion kinetics in the gated CAR-T group (Fig. 1F–I; Supplementary Fig. S5B and S5C). It is important to note that the improved expansion for circuit CAR was in the context of residual disease (Fig. 1D), and a few animals reached a terminal point with symptoms of GVHD, but there was no frank evidence of disease in either group of gated or constitutively expressed CAR-T cells.

Figure 1.

AML can be targeted using SynNotch CAR-T cells. A, Primary human T cells were engineered with CD33-sensing SynNotch with genetic circuit encoding for CD123 CAR. B, Growth kinetics of GFP+ AML cell lines (MOLM13, THP1, and KG1) cocultured with indicated T cells. Untransduced T (UT) cells were used as control. C, Cytokine levels were measured by ELISA in the supernatants of T cells expressing the specified constructs after 48 hours of coculture with the MOML13 AML cell line at a 1:1 E:T ratio. D–I, NSG mice were injected with 1 million luciferase-expressing MOLM13 or KG1 cells and, a week later, with 10 million of the indicated T cells. Surviving mice were followed for a minimum of 100 days after tumor inoculation. D and E, Quantified bioluminescence intensity of the mice. F and G, Mouse survival plotted by Kaplan–Meier graph. H and I, Human CD3 T-cell counts in peripheral blood (PB) 2 weeks after CAR-T infusion. B, At least two independent experiments. Data are means ± SEM. D and E, UT (n = 5 and 3), CD123 (n = 5 and 4), and CD33→CD123 (n = 5 and 4). Statistics were calculated using the unpaired Mann–Whitney t test (F and G) and Student t test (C, H, and I) *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. GFP, green fluorescent protein.

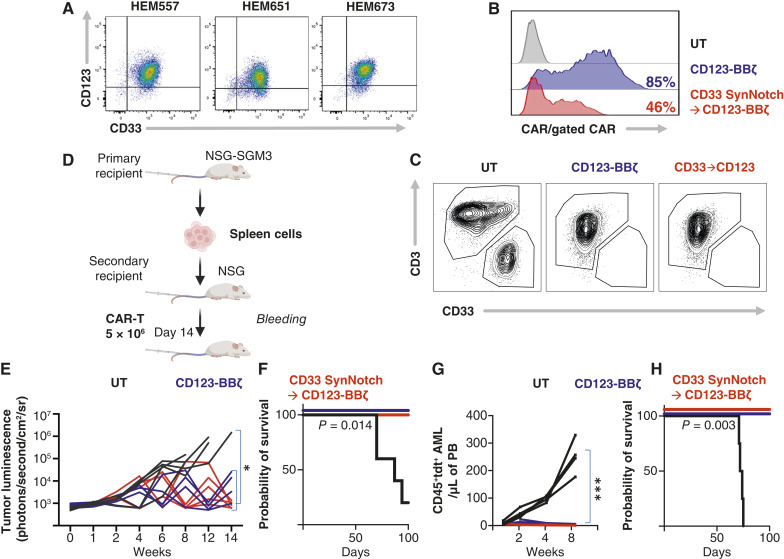

CD33→CD123 SynNotch-Gated CAR-T Cells Are Effective against Patient-Derived AML Disease

We asked if CD33→CD123 gated CAR-T cells would be effective against AML Patient-derived xenografts (PDX). First, we verified that these PDX AML blasts expressed CD33 and CD123 (Fig. 2A). We then used previously collected samples from these patients for whom we have established the PDX models to engineer autologous AML CAR-T cells for two patients (Fig. 2B; Institutional Review Board # 08-00141). Autologous CD33→CD123 gated CAR-T cells effectively eliminated AML blasts (Fig. 2C). We then tested the efficiency of these autologous CD33→CD123 gated CAR-T cells in the PDX model. We used the patient AML blasts harvested from the spleen of the third disease passage in NSG-SGM3 mice to establish PDX in NSG mice (Fig. 2D). Prior to mice implantation, patient AML blasts were transduced with lentivirus to express firefly luciferase allowing for bioluminescence imaging monitoring and TdTomato fluorescent protein to monitor the leukemic burden in the peripheral blood. NSG mice received intravenous injections of the patient AML blasts followed a week later by autologous constitutively expressed CD123 CAR-T cells, or CD33→CD123 gated CAR-T cells compared with control untransduced cells. PDX AML disease burden was significantly reduced in mice treated with CD33→CD123 gated CAR-T cells and fully cured in another one (Fig. 2E–H). These data support the feasibility of engineering gated CAR-T cells from patients with AML and show efficiency against human disease.

Figure 2.

CD33→CD123 SynNotch-gated CAR-T cells are effective against patient-derived AML disease. A, Color dot plot measuring CD123 and CD33 expression on three AML PDX samples. B, A representative histogram shows CAR expression on CAR-T cells engineered from patient with AML samples, detected with His-tagged CD123 for the CD123 CAR and His-tagged CD33 for the CD33→CD123 uniframe CAR. C, Representative contour plot of AML PDX sample cocultured with indicated patient’s autologous T cells. D, PDX AML samples were passaged in NSG-SGM3 before implantation into NSG mice and treatment with CAR-T cells. E, Spaghetti plot shows the bioluminescence of individual PDX1Luc+ mice treated with the indicated T cells. F, Mouse survival plotted by Kaplan–Meier graph from (E). G, AML detected in the peripheral blood (PB) of PDX2Tdtomato+ mice treated with the indicated T cells, assessed by flow cytometry. H, Mouse survival plotted by Kaplan–Meier graph from (G). Statistics were calculated using two-way ANOVA (E and G) and unpaired Mann–Whitney t test (F and H). E and G, UT (n = 5 and 4), CD123 (n = 4 and 5), and CD33→CD123 (n = 4 and 5). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001. UT, untransduced T cell.

CD33→CD123 SynNotch-Gated CAR-T Cells Exhibit a Favorable Phenotype

Maintaining multifunctional T cells and preventing their exhaustion/dysfunction is a limiting factor in CAR-T therapy. The constitutive expression of CARs induces an antigen-independent T-cell activation state known as tonic signaling (24, 25). The tonic signaling, however minimal, has been linked to unforgiving phenotype changes in CAR-T cells, like loss of long-lived memory T cells and upregulation of inhibitory receptors. Although various structural elements in CAR design—such as scFv conformation, hinge, and costimulatory domains—can contribute to tonic signaling, the primary culprit is its constitutive expression (26). Thus, we reasoned that the inducible, intermittent, and restricted expression of CARs through SynNotch circuits could mitigate tonic signaling and its harmful effects (21–23). We found that constitutive expression of CD123 CAR led to heightened antigen-independent activation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) reporter, suggestive of tonic signaling. In contrast, the CD33→CD123 gated circuit showed significantly lower NFAT activation despite both constructs having similar genomic integration levels, suggesting that SynNotch-regulated CAR expression can preserve the T-cell’s state by minimizing the adverse effects of tonic signaling (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Fig. S6A and S6B). Despite the existing tonic activation, constitutively expressed CD123 and the CD33→CD123 CAR-T cells generated from individual donors show similar antigen-independent expansion kinetics in culture with IL-2 (Fig. 3B). However, constitutive expression of the CD123 CAR skewed T-cell differentiation toward a smaller fraction of cells with an immunophenotype resembling long-lived T stem cell memory-like (TN/SCM) cells, identified as CD62L+CD45RA+. In contrast, it generated a higher proportion of T effector memory (TEM) cells, characterized as CD62L−CD45RA−, compared with T cells regulated by the CD33→CD123 SynNotch circuit (Fig. 3C–E). Aligned with our observations, constitutive CAR expression resulted in heightened expression and overlap of markers indicative of T-cell exhaustion, whereas it was prevented if expressed through the SynNotch circuit (Fig. 3F and G).

Figure 3.

CD33→CD123 SynNotch-gated CAR-T cells exhibit favorable phenotype. A, Representative histogram of basal NFAT reporter activation in Jurkat cells transduced with the specified CAR at an MOI of 60 per cell, sorted for CD123 CAR or CD33 SynNotch, and selected with drugs for NFAT reporter. B, Summary data representing two individual donors’ antigen-independent expansion kinetics of indicated T cells (IL-2 only). C, Gating strategy for immunophenotyping T cells. D, Pseudocolor plot showing the immunophenotype of sorted CAR-T cells engineered from a single donor. E, Proportions of TN/SCM and TEM CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from three donors, engineered to express the specified CAR 14 days after CD3/CD28 Dynabead stimulation. F, Histogram showing the expression of exhaustion markers in T cells from (E). G, Cumulative analysis of exhaustion marker expression in T cells from (E). Statistics were calculated using two-way ANOVA (B) and Mann–Whitney U tests (E). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001. ns, not significant; TEMRA, terminal effector memory T cells; UT, untransduced T cell.

SynNotch-Gated CAR-T Cells Remain in a Memory State during Chronic Tumor Exposure

We next evaluated whether SynNotch-gated CAR expression, compared with constitutive CD123 CAR-T cells, could sustain T-cell expansion and prevent unwanted differentiation. To test this, we exposed CAR-T cells—expressing CD123 either constitutively or through the CD33 SynNotch circuit—to chronic antigen stimulation over 4 weeks, replenishing AML cells every 4 days. Although the constitutive CD123 CAR-T cells exhibited a declining expansion rate over time, the CD33→CD123 SynNotch-gated CAR-T cells maintained a stable expansion comparable with baseline throughout the entire period of antigen exposure (Fig. 4A). We periodically assessed the differentiation status of the T cells to track changes in memory and effector populations over time. At baseline, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with constitutive CAR expression displayed a greater proportion of TEM and a smaller population of TN/SCM than those expressed via CD33 SynNotch circuit (Supplementary Fig. S7). With three rounds of stimulation with dual antigen-positive target cells, the SynNotch circuit CAR T cells retained a higher fraction of T central memory (TCM) (CD45RA−CD62L+) and significantly lower TEM (Fig. 4B). Notably, the gated CAR’s TN/SCM population decreased and increased after each stimulation, suggesting the bidirectional T-cell phenotype swings before and after each cycle of stimulation (Fig. 4B). Despite the superior T-cell phenotype of the SynNotch circuit during repetitive exposure, constitutively expressed CARs remained effective against the AML cell line with high CD123 expression (MOLM13) but lost effectiveness against THP1, the cell line with lower CD123 expression (Fig. 4C and D). This suggests a long-term balance favoring gated CAR-T cells if CD123 target density decreases below a certain threshold. Similarly reflected in RNA expression gene enrichment set analysis, these gated CAR-T cells enriched naïve-like, unstimulated, and resting T-cell gene sets after exposure to the target cells, in contrast to constitutively expressed 123 CARs that were emulating severe inflammation and ongoing immune responses (Fig. 4E; Supplementary Fig. S8). Importantly, constitutively expressed CD123 CAR-T cells showed enrichment of gene sets indicative of genes upregulated in hypoxia, glycolysis, and IFNg dependency related to terminal T-cell fate (Fig. 4E; Supplementary Fig. S8). To examine the CD123 CAR phenotype in vivo, we treated MOLM13 AML mice at medium and low T-cell doses (50% and 90% dose reduction) to boost antigen exposure and expansion kinetics. Both CAR-T groups showed disease control with partial loss of treatment effect at the lowest dose (Fig. 4F; Supplementary Fig. S9A). We observed significantly higher total T-cell counts (medium dose) and TN/SCM and TCM fractions in the peripheral blood of mice treated with CD33→CD123 compared with constitutively expressed counterparts 2 and 3 weeks after CAR-T infusion (Fig. 4G and H; Supplementary Fig. S9B and S9C). However, the absolute count of these subfractions was not statistically significant in most time points because of the small sample size and outliners (Supplementary Fig. S9D). Our data suggest that SynNotch-mediated CAR expression could be a promising approach for managing tonic signaling, preventing detrimental T-cell differentiation before antigen exposure, and maintaining T-cell functionality during long-term culture and repeated antigen exposure (21, 22).

Figure 4.

SynNotch-gated CAR T cells remain in a memory state during chronic tumor exposure. A, Summary plot of longitudinal expansion kinetics for indicated T cells in coculture with AML cell lines (MOLM13 and THP1). Cell count was documented using flow cytometry every 4 days, fold increase was calculated to baseline, and fresh AML was added after dilution at a 1:1 E:T ratio. B, Phenotypic evolvement for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for indicated T cells experimented similar to (A). C, Residual AML disease during repetitive tumor exposure measured using flow cytometry from (B). D, CD123 and CD33 antigen density per cell measured using flow cytometry. E, Enriched gene sets in indicated T cells after a 48-hour coculture with the MOLM13 AML. F, Spaghetti plot representing individual bioluminescence intensity of MOML13Luc+ mice treated with indicated T cells at a lower dose of 5 million T cells/mouse. G, Absolute count of human CD3 T-cell counts in peripheral blood of mice in (F). H, Pooled TN/SCM, and TCM frequency in peripheral blood of mice treated in (F) and Supplementary Fig. S9A (1 million T cells/mouse). Statistics were calculated using two-way ANOVA (A, C, F, and G), Mann–Whitney U, and stepdown Holm–Šidák tests (B and H). G and H, Statistics compared CD123 versus CD33→CD123 group. F, UT (n = 4), CD123 (n = 4), and CD33→CD123 (n = 4). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. CTRL, control; DN, down; PBMC, peripeheral blood mononuclear cell; STIM, stimulated; UNSTIM, unstimulated; UT, untransduced T cell.

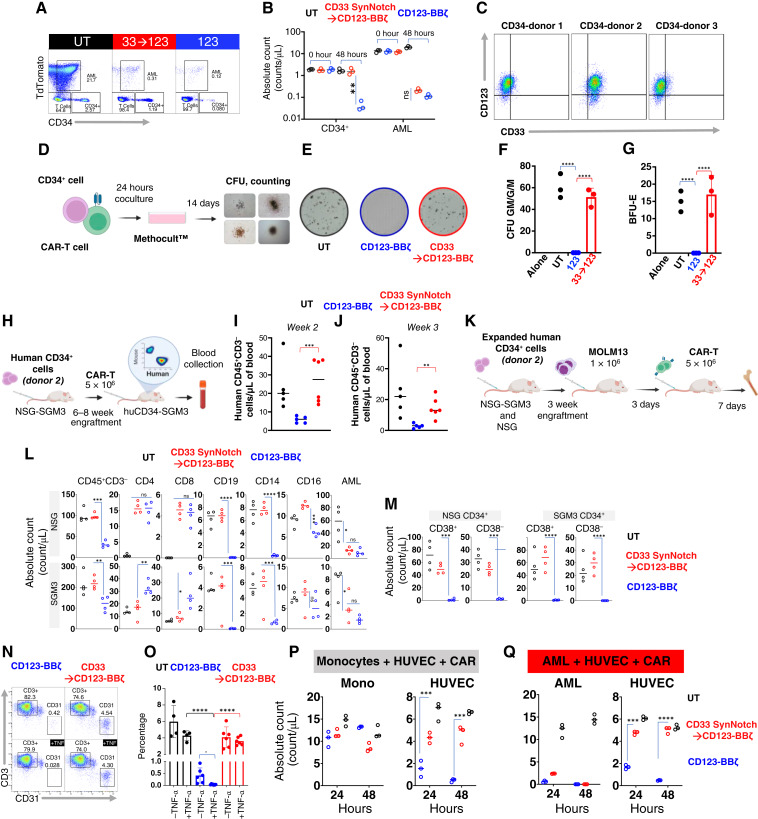

CD123 CAR Expressed through a SynNotch Circuit Alleviates the Risk for Hematopoietic Toxicity

CD33 and CD123 are expressed on hematopoietic stem cells at significantly lower and variable antigen densities in our patient population (Fig. 5A). We hypothesized that CD33 antigen density at low levels does not engage CD33 SynNotch sufficiently to express the CD123 CAR nor gated expression of CD123 CAR is adequate to engage forceful signaling at the density expressed on HSPCs. First, we confirmed that cells expressing only CD123 even at high levels (Jurkat CD123trunc) are not killed by CD33→CD123 gated CAR-T cells even at a high effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 10:1, suggesting that the CD33→CD123 SynNotch circuit is not associated with leaky expression of the CD123 CAR in the absence of CD33 expression on-target cells (Fig. 5B). Then we generated a drug-inducible antigen expression system in which dose-dependent exposure to doxycycline induces the expression of CD33 to simulate the antigen expression heterogeneity between leukemia cells and the HSPCs (Fig. 5C; Supplementary Fig. S10A and S10B). To quantify the expression kinetics of the CD123 circuit CAR, we cocultured CD33→CD123 Jurkat cells with target cells exhibiting a range of CD33 antigen levels at a 5:1 E:T ratio, which reflects physiologic antigen exposure ratio in the marrow (10%–20% CD33-positive cells). We found that the CD33 SynNotch circuit’s response to lower CD33 antigen density was significantly dampened compared with that with AML cell lines or cells with artificially high expression of CD33 (Fig. 5D). We then cocultured normal donor bone marrow (BM) CD34+ cells with gated and constitutively expressed CAR-T cells. After 48 hours of coculture, remaining live CD34+ cells were significantly lower in the coculture with constitutively expressed CD123 CAR cells than with CD33→CD123 gated T cells (Fig. 5E and F; Supplementary Fig. S11A), demonstrating precision killing of the gated CAR circuit. However, to further evaluate the safety of CD33→CD123 gated CAR-T cells in relation to HSPCs, we investigated whether circuit CAR expression, immediately or shortly after the elimination of tumor cells (during the decay phase), could sustainably exceed the threshold necessary to eradicate CD34+ HSPCs (Fig. 5G). Initially, we measured the expression of CD123 CAR through the CD33 SynNotch receptor in the CAR-T and AML coculture. Notably, we observed that shortly after the AML was eliminated (approximately 18 hours), the expression of the circuit CAR significantly decreased (Fig. 5H and I). We then introduced human HSPCs to these cultured CAR-T cells expressing CD123 CAR in the decay phase to mimic physiologic exposure between these CAR-T cells and the marrow HSPCs. In coculture, HSPCs within the CD33→CD123 gated CAR-T cells were significantly preserved compared with the constitutively expressing CAR-T cells, exhibiting less toxicity to the HSPCs at later time points further away from AML exposure 24 and 36 hours (Fig. 5J and K; Supplementary Fig. S11B). Importantly, at 18 hours (immediately following tumor clearance), HSPCs were not eliminated, suggesting that the circuit CAR-T cells, in the decay phase, could not sustainably maintain CD123 CAR expression above the threshold needed to harm HSPCs. We then investigated whether antigen variability on HSPCs sourced from different donors negatively impacts the ability of these CD123 circuit CAR-T cells to preserve HSPCs when activated through the SynNotch receptor in response to CD33 expressed on AML cell lines or monocytes (major blood CD33-positive cells). We observed significantly lower expression of CD33 on HSPCs and monocytes compared with MOLM13 (Fig. 5L and M) and far fewer CAR-T cells expressed CD123 CAR through CD33 in exposure to monocytes compared with AML at the maximum activation 18 hours, suggesting that monocytes are less potent in initiating our SynNotch circuit (Fig. 5N–P; Supplementary Fig. S12A and S12B). The difference becomes less pronounced after 18 hours as AMLs are eliminated and CD123 circuit CARs lose expression. We demonstrated that the residual CD34+ HSPC counts in coculture with these circuit CAR-T cells were comparable with those with untransduced at most time points, and counts were highly significantly different from those with constitutively expressed CAR-T cells, regardless of activation in the presence of AML or monocytes. As expected, the constitutively expressed CD123 CAR-T cells universally eliminated these HSPCs (Fig. 5Q). We then evaluated off-tumor toxicity to HSPCs, in which HSPCs were exposed to CAR-T cells simultaneously with AML. At a 20:5:1 ratio of CAR-T cells to AML to HSPCs, which mimics a minimal disease BM environment, suggesting the ability of the circuit CAR to preserve HSPCs (Fig. 6A and B; Supplementary Fig. S13 and S14). These collective data support our hypothesis that gated expression of CD123 CAR from the CD33 SynNotch circuit does not mount over the cytotoxicity threshold for the lower CD33 and CD123 density targets. To probe the impact of gated CAR-T cells on HSPC proliferation and differentiation, additional BM-derived mobilized CD34+ cells were exposed to gated CD33→CD123 or CD123 CAR-T cells and were assessed for colony-forming ability. Similar to BM samples, there was variability in CD33 and CD123 expression among three donors. For these experiments, we chose the double-positive donor two (Fig. 6C). There was no difference among untreated or treated with untransduced or gated CD33→CD123 T cells in granulocyte–macrophage colony units (CFU-GM/G/M) or the erythroid colony units BFU-E (Fig. 6D–G); however, strikingly, these colonies were universally eliminated with constitutively expressed CD123 CAR-T cells (Fig. 6D–G). We then generated a humanized mouse model using these mobilized patient CD34+ stem cells to test if the gated CD33→CD133 CAR-T cells could prevent the degree of myelosuppression caused by CD123 CAR-T cells. In brief, NSG-SGM3 mice were injected with 1 × 106 CD33+CD123+CD34+ HSPCs isolated from patients undergoing stem cell mobilization (donor 2) after sublethal total body irradiation (200 cGy; Fig. 6H). Six to eight weeks later, we observed partial engraftment of the human hematopoietic system detecting dominantly B cells and a few monocytes (Supplementary Fig. S15). We then injected these humanized mice with T cells expressing CD123 CAR constitutively or through the CD33 SynNotch circuit. Compared with animals treated with CD123 CAR-T cells and their shrinking human CD45+ population, we observed significantly preserved human CD45+CD3− in the gated CD33→CD123 group, similar to the untransduced T-cell recipients (Fig. 6I and J). We then questioned if CD33→CD123 CAR-T cells would have preserved HSPCs in the humanized mice model if the AML or a larger monocyte population (CD33+) were present. Due to the limitations of the SGM3-based humanized model with skewed blood cell populations over a longer period after engraftment, we followed a recently described (27) experimental design in which NSG or SGM3 mice received expanded CD34+ cells, followed by AML and paired CAR-T cells (CAR-T cells engineered from T cells of the paired healthy marrow donor), on an expedited timetable (Fig. 6K). Similarly, we show significantly reduced CD45+CD3− populations in the marrow of mice treated with constitutively expressed CD123 CARs compared with CD33→CD123 or the UT (Fig. 6L). Although both CAR-T groups showed efficacy in disease reduction, we noted a significant depression of CD19, CD14, and CD16 positive populations in CD123 CAR-T–treated mice, unlike the CD33→CD123 group, which remained similar to the UT group in the BM of these mice (Fig. 6L; Supplementary Fig. S16A–S16C). More importantly, we showed significantly higher human CD34+ cells in the marrow of the mice treated with CD33→CD123 while demonstrating disease control (Fig. 6M; Supplementary Fig. S17A–S17C). The potential of the CD123 CAR in terms of efficacy and toxicity has not been fully realized. Early CD123 CAR-T trials suggested an exaggerated vascular leakiness, and recently, Richards and colleagues (28) described the upregulation of CD123 on vascular endothelial cells. We explored if, similar to HSPCs, endothelial cells could be spared from CD123 CAR-T toxicity if expressed through the CD33 SynNotch circuit. In agreement, we observed the upregulation of CD123 on the HUVEC endothelial cell line in the presence of inflammatory cytokine TNF-α (Supplementary Fig. S18A); however, even in the absence of TNFα exposure, constitutively expressing CD123 CAR T-cell eliminated HUVEC cells. In contrast, gated CD33→CD123 CAR-T cells, independent of exposure to TNFα, had no significant impact on HUVEC cells compared with untransduced T cells (Fig. 6N and O). Again, to explore physiological conditions, we cocultured HUVEC cells with CAR T cells in the presence of monocytes or AML and demonstrated significant on-target off-tumor toxicity from constitutively expressed CARs, whereas CD33→CD123 CAR-T cells eliminated AML and preserved endothelial cells (Fig. 6P and Q; Supplementary Fig. S18B). Circuit CAR expression through SynNotch receptor could help to protect hematopoietic stem cells and vascular endothelial cells from CD123-directed CAR T-cell toxicity.

Figure 5.

The expression of CD123 CAR through a SynNotch circuit remains below the threshold for eliminating stem cells. A, Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) plot representing the CD33 and CD123 expression on our patient’s AML blast and their concurrent normal HSPCs compared with the negative control (CTR−). B, Kinetics of Jurkatmcherry+ cells expressing truncated CD123 only (CD33−) cocultured with indicated T cells at low 1:1 and high 10:1 E:T ratios, monitored using the IncuCyte platform. C, Histograms representing CD33 expression on Jurkat cells with Tet-inducible CD33 expression, various AML cell lines, and Jurkat cells forced expressing truncated CD33. D, Histograms representing CD123 CAR expression through CD33 SynNotch receptor in coculture (E:T of 5:1) with Jurkat cells from (C). E and F, Representative pseudocolor plot and summary data from three normal BM donors showing the remaining CD34+ cells 48 hours after coculture with the indicated T cells at an exaggerated 20:1 ratio. G, Schematics of AML coculture with indicated T cells followed by addition of HSPCs at 18, 24, and 36 hours of AML exposure. H and I, Histogram and summary data (three T-cell donors) representing kinetics of CD123 CAR expression on indicated T cells in coculture with MOLM13 AML at E:T of 1:2. J and K, Pseudocolor plot and summary data representing coculture experiments in which CD34+ HSPCs were added to T cells from (J) at indicated decay time points, and the live HSPC population was measured 48 hours later. L and M, Histogram and summary data representing the expression of CD33 and CD123 on monocytes and HSPCs from three normal donors compared with MOLM13 AML. N, Schematics of Monocytes and AML coculture with indicated T cells followed by addition of HSPCs (three different donors) at 18, 24, and 36 hours of AML exposure. O, Representative color plot showing the CD123 CAR expression constitutively or through CD33 SynNotch in coculture with monocytes or AML as in (P). P, Plots representing individual CD123 CAR+ T-cell count in coculture with monocytes (Mono) or AML at 18, 24, and 36 hours. Q, Plots representing coculture experiments in which CD34+ HSPCs were added to CAR-T cells from the top at 18, 24, and 36 circuit CAR decay, and the live HSPC population was measured 48 hours later. Statistics were calculated using the Student t test (A, F, and M), Mann–Whitney U test (P and Q), and two-way ANOVA with the multiple paired t test (I and K). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Dox, doxycycline; ns, not significant; UT, untransduced T cell.

Figure 6.

CD123 CAR expressed through a SynNotch circuit reduces the risk for hematopoietic toxicity. A and B, Pseudocolor flow cytometry dot plot (48 hours) and the summary data (three normal BM donors) representing the experiment in which indicated T cells were simultaneously cocultured with AML and HSPCs at an exaggerated CAR:AML:HSPC ratio of 20:5:1. C, Pseudocolor flow cytometry dot plot demonstrating CD33 and CD123 expression on peripherally mobilized stem cells. D, Experimental design for colony-forming unit (CFU) assay. Indicated T cells were cocultured with human CD34+ cells (donor 2) at a 1:1 E:T ratio for 24 hours before plating those stem cells on MethoCult for 14 days for the CFU assay. E, Snapshot image of CFU field representing colonies devolved from human CD34+ after coculture with indicated T cells. F and G, Summary bar graph representing CFU and BFU (burst-forming units) counts from CD34+ cells cocultured with three T-cell donors. H, Experimental design of humanized NSG-SGM3 AML CAR toxicity. Six- to eight-week-old NSG-SGM3 were transplanted with human CD34+ stem cells, followed by intravenous injection of indicated T cells at 12 weeks. I and J, Bar graph demonstrating individual mice blood counts 2 and 3 weeks after receiving indicated T cells. K–M, humanized NSG or NSG-SGM3 AML CAR toxicity study: 6–8-week-old NSG or NSG-SGM3 mice were transplanted with expanded human CD34+ stem cells, followed by AML injection in week 3. The indicated T cells were administered 3 days later, and BM was assessed 7 days after by flow cytometry staining. L–M, Individual absolute counts of gated BM populations of lymphocyte subsets (L) and CD34+ cells (M). Please see Supplementary Figs. S16A and S17A for the full gating schemes. N and O, Representative plot (left) and quantification of flow cytometry assay of HUVEC cells (CD31+) cocultured for 48 hours with the indicated T cells (CD3+) at a 20:1 ratio, with or without TNF-α. P and Q, Plots showing absolute cell counts at 48 hours from cocultures of HUVEC with monocytes or AML with the indicated T cells from three healthy donors. Statistics were calculated using ANOVA and post hoc analysis using the Student t test (B, F, G, I, J, L, M, and O), two-way ANOVA with the multiple paired t test (P and Q). I and J, UT (n = 5), CD123 (n = 5), and CD33→CD123 (n = 6). L and M, UT (n = 4), CD123 (n = 4), and CD33→CD123 (n = 4). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Mono, monocyte; UT, untransduced T cell.

CD33→CD123 CAR-T Does not Cause Systemic Cytokine Release Syndrome

CAR-T therapy for high-risk patients has been complicated by severe CRS, characterized by an intense immune storm, hemodynamic instability, and vascular leakage, often leading to respiratory failure (29–31). CRS generally develops within days of T-cell infusion, aligning with the peak expansion of CAR-T cells. Its severity is associated with heightened levels of blood cytokines like IL-6 and IL-1 produced by recipient myeloid cells, including macrophages (32, 33). We hypothesized that less intense gated CARs with less tonic signaling could avoid CRS. To simulate human CRS in AML in the presence of human myeloid cells, we used humanized NSG-SGM3 mice inoculated with AML cell line MOLM13 followed by CD33→CD123 or CD123 CAR-T treatment (Fig. 7A). Low-burden AML model (0.2 × 106 MOLM13 cells) showed minimal clinical change, yet controlled the disease with either CARs (Supplementary Fig. S19A–S19C). However, unlike gated CD33→CD123, high-burden humanized AML mice (established from 1 × 106 MOLM13 cells) treated with constitutively expressed CD123 CARs triggered a severe systemic inflammatory syndrome. This response closely resembled human CRS, marked by significant weight loss, piloerection, and elevated levels of systemic cytokines (Fig. 7B and C), including significantly elevated levels of human IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1, and mouse G-CSF, IL-1R, MCP-1, and CXCL10 (Fig. 7C; Supplementary Fig. S20). To define the cellular determinants of CRS without bias, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on human (n = 14,866) and mouse (n = 13,766) CD45+ leukocytes isolated from humanized SGM3 AML mice’s spleen treated with constitutively expressing CD123 (n = 2) or CD33→CD123 CAR T cells (n = 3) at the time of CRS (day 7 after CAR T-cell injection). Pooled single-cell data during CRS showed that splenic cells of the mice treated with gated and constitutively expressed CARs formed distinct human and mouse clusters (Fig. 7D). Using our best effort to perform supervised annotation of these clusters, we identified human cells to include mainly T and B cells lineage in addition to mast cells, plasma cells, and mouse cells included two major populations of macrophage/monocytes and neutrophils (Fig. 7D; Supplementary Fig. S21A and S21B; Supplementary Data S1). We then performed ingenuity pathway analysis pathway discovery analysis between each cluster’s gated versus constitutively expressed compartments. We found evidence of RIG-I–dependent IFN-γ response in human B cells and STAT1 upregulation in plasma and mast cells (Fig. 7E; Supplementary Fig. S21C). In agreement with the findings in previous models of CRS, in our humanized model, we also found strong universal involvement of IL-1 and TNF-α in mouse myeloid, neutrophil, and plasmacytoid dendritic cell subsets (Fig. 7E; Supplementary Fig. S21D). Noticeable separation of the cell clusters in gated versus constitutively expressed CAR-T–treated mice signals fundamentally different T-cell behavior between SynNotch-mediated and constitutively expressing CAR-T cells and how they communicated with their immune environment. In addition, here, for the first time, we demonstrate the alteration of the cross-talk between human and mouse cells to drive CRS in response to SynNotch-gated CAR-T cells.

Figure 7.

CD33→CD123 CAR-T does not cause systemic cytokine release syndrome. A, Experimental design for humanized NSG-SGM3 AML CAR-T CRS toxicity: 6–8-week-old NSG-SGM3 mice were transplanted with CD34+ stem cells, followed by MOLM13 AML injection. After 6–8 weeks, mice received the indicated T cells and were sacrificed 7 days later. B, Plot representing individual mouse weight loss from (A) 7 days after CAR-T infusion. C, Summary bar graphs representing human (h) and mouse (m) cytokines measured in blood using ELISA. D, Pooled t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot displays of scRNA-seq data from human (left) and mouse (right) CD45+ cells isolated from the spleens of five humanized AML mice treated with CD123 (n = 2) or CD33→CD123 (n = 3), as shown in (A). Distinct clusters of splenic human and mouse cells, identified at peak CRS, were annotated with biomarkers from the Partek Flow platform (Supplementary Data S1) and labeled accordingly using CellMarker. E, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of splenic cell transcriptome from mice in (D): network and canonical pathway analyses were performed for genes showing significant changes in splenic cells of humanized SGM3 AML mice treated with CD123 versus CD33→CD123. These analyses were conducted separately for the human B cells and mouse myeloid clusters. Additional network analysis data are presented in Supplementary Fig. S21C and S21D. Statistics were calculated using the Student t test (B and C). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001. pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; UT, untransduced T cell.

Discussion

The use of CAR-T cells for treating AML has faced challenges, primarily because of the absence of antigens exclusive to the tumor. Various approaches have been developed to minimize the unintended toxic effects of AML-specific CAR-T cells on healthy cells. Examples include gene-edited stem cells (CD33 KO HSPCs) designed to reduce toxicity from CD33 CAR-T treatment, a novel NOT-gated CAR approach aimed at counteracting CD93 CAR-T’s toxic impact on normal endothelial cells, and CAR-T targeting a conformationally specific form of an integrin protein predominantly expressed in AML (28, 34, 35). Although these approaches are innovative, they come with limitations. For instance, using CD33-edited HSPCs as a recovery mechanism after CAR-T treatment raises questions about the long-term consequences of eradicating CD33 protein from blood cells. Similarly, the NOT-gated CAR protects only a particular tissue or organ from unintended toxicity, complicating the design if more tissues require protection. Conformationally specific protein targets are also subject to AML heterogeneity and significant changes in gene expression, especially during treatments (36). These changes could alter the conformational structure, risking treatment efficacy. Additionally, the possible transient presence of these conformationally altered proteins in normal cells could increase the risk of toxicity in clinical scenarios. Interestingly, some argue that the off-target hematopoietic toxicity effects of CAR-T cells targeting AML antigens could be advantageous, serving as a bridge to stem cell transplantation. However, we acknowledge that replacing traditional pre-transplant treatments with cell-based approaches could benefit some but not everyone. Specifically, older patients or those with additional health issues may not be eligible for transplants because of the unavailability of compatible stem cell donors or other complications. If a backup plan involving transplantation fails, the sustained decrease in blood cell counts due to CAR-T toxicity poses an unacceptable risk. Therefore, it is crucial to develop AML CAR-T therapies that are both safe and effective, irrespective of the potential for stem cell transplantation.

Here, we selected CD33 and CD123, frequently targeted but nonspecific markers in AML, to construct a SynNotch receptor for CD33 that triggers the expression of CD123 CAR-T cells. We demonstrated both in coculture and animal models that the gated expression of CD123 from the CD33 SynNotch receptor significantly limits toxicity against HSPC while remaining effective against AML. The circuit expression of CD123 CAR in response to low-density CD33, similar to that found in HSPCs and monocytes, was significantly lower compared with their response to higher-density CD33 targets, such as those present in AML blasts. Additionally, we observed that the expression of CD123 immediately after disengaging from leukemia cells was below the threshold required to harm HSPCs. We propose that the rapid decay kinetics of our CD33→CD123 CAR-T cells, along with the lower target density and the temporal–spatial separation between leukemia cells and HSPCs, especially in scenarios involving minimal residual disease in human BM, further support the notion that the cumulative exposure (circuit CD123 CAR density × time) may remain below the toxicity threshold for HSPCs. However, this temporal–spatial separation can vary depending on the type of AML, disease burden, and marrow cellularity. The prolonged and repeated coexistence of leukemia and HSPCs in patients, as opposed to the conditions modeled in our study, adds further complexities. Additionally, the variability of CD33 expression on monocytes and other blood cells in different clinical contexts, along with the time required to clear the disease, could exacerbate vulnerabilities in our SynNotch-gated system, increasing the risk of toxicities that might only be accurately assessed in human patients. We recognize the limitations of our preclinical model in fully replicating human conditions and reference the findings from Srivastava and colleagues (37) and Tousley and colleagues (38), who reported unintended killing of single-antigen tumor cells during the decay phase of SynNotch-gated CAR expression. Given the differences in the SynNotch gate, CAR target antigens, antigen densities (including the use of forced-expressed targets in cells that exhibited unintended killings), expression and decay kinetics of the circuit CAR, and the distinct characteristics of off-tumor targets—along with various structural design and manufacturing differences—it is difficult to make direct comparisons between our model and the ROR1 SynNotch CAR circuits described in these studies. Nonetheless, considering these observations and the recently reported clinical toxicities associated with targets like ROR1, we acknowledge that distinguishing between double-positive CD33/CD123 and single-positive CD123 cells may be imperfect, underscoring the need for further validation in clinical settings.

Others have described additional sets of target antigens through proteomic-genomic methods, aiming for comprehensive coverage of AML antigens. Nevertheless, the existing computational model was structured to identify targets suitable for a dual CAR system composed of two separate traditional CARs (2–4). The foundational premise of this model was that the antigens should be specific to the tumor and that two distinct antigens are necessary to account for tumor heterogeneity. These stringent criteria have considerably narrowed the range of viable AML targets, hindering advancements in AML-specific cell therapies. In a recent study, Haubner and colleagues (27) integrated the output of this model that combined two AML antigens, ADGRE2 and CLEC12A, into a novel combinatorial CAR based on the split CAR concept. The two components of this CAR work synergistically, generating a strong signal only when the antigen density surpasses a specific threshold. This design relies heavily on antigen density to drive CAR-T cell activity and reduce off-target toxicity. Unlike the “IF-BETTER” CAR-T cells, in which both antigens simultaneously contribute to CAR signaling, the CD33→CD123 “IF-THEN” CAR temporally separates the signaling from the gate antigen, eliminating the risk of toxicity against cells that only express CD33. Additionally, in contrast to the dual CAR system, which requires the presence of multiple tumor-specific antigens, our approach utilizes a semispecific but highly expressed SynNotch gate antigen combined with a nonspecific but universally expressed CAR antigen. This offers greater flexibility, as the logical gating of the SynNotch system reduces the need for strict tumor specificity and expands the pool of potential target antigens.

Recent trials in AML using CAR-T cells have yielded only modest success, with many patients showing signs of disease progression during the initial stages of CAR-T therapy. Likewise, real-world data on CAR-19 therapy indicates a strong correlation between CAR T-cell expansion and sustained remission. In this context, we investigated the potential benefits of SynNotch CAR-T cells in models that closely resemble human AML conditions, using both PDX and humanized models. Our work demonstrated the specificity of SynNotch CAR circuits and their potential to sustain a long-lasting T-cell phenotype with enhanced expansion kinetics, positioning SynNotch CAR-T cells as a promising alternative to overcome some of the existing limitations of CAR-T therapies for AML. Notably, alternative strategies to our CD33→CD123 IF-THEN SynNotch logical circuit primarily rely on the constitutive expression of CARs, leaving them susceptible to tonic signaling, early exhaustion, and short-lived CAR-T cells. Using drugs like dasatinib to mitigate this issue and avoid T-cell exhaustion in constitutively expressed CARs is an interesting approach that resembles the self-regulating behavior of the SynNotch circuit (39). However, temporary relief from tonic signaling only during the drug’s active period overlooks the ongoing need to prevent T-cell exhaustion in the face of chronic tumor exposure. The broader effects of drugs like dasatinib remain largely unknown, especially about their impact on T-cell function. Therefore, the true consequences of such drug interventions on T cells should be rigorously assessed through human clinical trials.

Our study revealed that gated CARs not only enhanced T-cell characteristics but also resulted in reduced cytokine production in vivo. Significantly, animals treated with these SynNotch circuit CAR-T cells did not exhibit CRS. Additionally, in alignment with recent studies from Mackall’s laboratory, which discussed the impact of inflammatory conditions on gene expression in tissues with similar origins of HSPCs, such as endothelial cells, we also observed an upregulation of CD123 in endothelial-derived cell lines when TNF-α was added to the culture media. However, unlike constitutively expressed CD123 CAR-T cells, gated CD33→CD123 CARs reduced toxicity to endothelial cells. Moreover, attenuated CRS response in gated CAR-T could dampen pro-inflammatory drive and reduce the risk of off-tumor toxicity against these endothelial cells. Additionally, preventing a pro-inflammatory microenvironment, which has been long suggested to play a role in AML progression, could enhance the efficacy of circuit CAR-T cells (40). This contrasts the potentially self-damaging impact of constitutively expressed CARs and their intense hyper-inflammatory CRS response, which could inadvertently promote AML progression.

We acknowledge additional limitations in our study, including gaps in data related to antigen heterogeneity and the risk of antigen escape from AML-gated CAR-T cells. Further research is essential to fully comprehend the effects of antigen downregulation on gated CAR circuits and to develop approaches to minimize such risks. Additionally, AML presents challenges in mouse modeling because of remaining innate immune cells that affect the disease’s engraftment. Utilizing the NSG-SGM3 mouse strain, which provides human cytokine support for AML engraftment, could also impact AML biology and diminish the results of our animal experiments. Despite these constraints, our findings illustrate some advantages of the SynNotch circuit over existing CAR T-cell therapies, particularly about precision and safety. It is notable that SynNotch-gated CAR-T cells are not a one-size-fits-all solution, and we caution against generalizing our findings to other combination antigens and disease models, as the complexity is influenced by CAR design, delivery methods, receptor density, binding affinity, and target density.

In summary, SynNotch’s dynamic antigen-dependent control of CAR expression allows T-cell therapies that maintain persistent antitumor activity while enhancing target specificity. Given these attributes, SynNotch CAR-T cells could offer therapeutic advantages for patients with AML who have not responded well to conventional treatment.

Methods

Primary Human Samples

AML samples were obtained according to the Administrative Panel on Human Subjects Research Institutional Review Board–approved protocols (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Institutional Review Board numbers 21-00319 and 08-00141) after written informed consent.

Cell Lines

Packaging cell lines, Jurkat, 293T, and human AML cell lines KG1 and THP1 were purchased from ATCC. MOLM13 was purchased from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen. iHUVECs were a gift from Dr. Yong-Mi Kim (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles). MOLM13, KG1, and THP1 were transduced with lenti-eGPF for cytotoxicity assays. MOLM13, KG1, and THP1 were transduced with lenti-Luciferase-T2A-puromycin or lenti-Luciferase-T2A-TdTomato for in vivo bioluminescence and cell tracking. Jurkat cells were transduced with LNFAT→ZsGreen first, followed by constitutive or SynNotch-gated CD123 CARs for reporter assay. Jurkat cells were transduced with Lenti-CD33truncated for SynNotch receptor activation and with Lenti-Tet-CD123 for antigen density assays. Transduced cells underwent flow cytometry-based sorting on a BD FACSAria or BD FACSymphony to isolate a uniform population of sorted cells. All cell lines were verified by short tandem repeat analysis and confirmed to be Mycoplasma negative by PCR every 12 months.

Generation of Human CAR Constructs and CAR-T Cells

The second-generation constitutively expressed CD33 and CD123 CARs feature anti-CD123 scFv (US patent # US9657105B2), anti-CD33 scFv (US patent # WO2019178382A1), D8 hinge (UniProtKB—P01732), 4-1BB costimulatory domain (UniProtKB—Q07011), and CD3-ζ (UniProtKB—P20963) signaling domain (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Production of CAR-expressing T cells was performed, as previously described. In brief, lentiviral supernatants were produced via transient transfection of the 293T cell line and concentrated using ultra-centrifugation. Human T cells were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy donors (EasySep Human T Cell Isolation Kit). CAR-T cells were produced from PBMC of at least two unique healthy donors for all experiments. T cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads (Life Technologies) in a 3:1 bead: cell ratio with 50 IU/mL IL-2 for 24 hours. Anti-CD3/CD28-activated T cells were transduced by placing cells on plates pre-coated with Retronectin (20 ng/mL, Takara) and concentrated lentivirus with the addition of 6 μg/mL polybrene. Media and IL-2 were changed every 2 days until harvesting cells 10 to 14 days after transduction. Transduction efficiencies were routinely 50% to 70% for all constructs. T cells co-expressing SynNotch receptors and responding genes were generated by transducing a 50:50 mixture of both viruses simultaneously for double-hit products. CAR-T cells were flow-sorted for 100% of the population on day 5 after transduction and expanded as described.

SynNotch receptors were constructed by linking signal peptide derived from the human CD8 to an anti-CD33 or anti-CD123 scFv. All sequences were reverse-translated, codon-optimized, and synthesized (by Integrated DNA Technologies). The resulting product was subcloned into pHR_PGK_antiCD19_SynNotch_Gal4VP64 (Addgene plasmid #79125), replacing the anti-CD19 region. The CAR construct for the gated system was generated by subcloning CD33-BBz or CD123-BBz in pHR_Gal4UAS_IRES_mC_pGK_tBFP (Addgene plasmid #79123) upstream of IRES. Subsequently, the IRES_mC_pGK_tBFP was removed to generate tag-free UAS-CD33-BBz or UAS-CD123-BBz. The extracellular portion of the human CD19 gene (UniProtKB—P15391) with pGK promoter was added to the UAS-B7H3-BBz to generate UAS-CD33-BBz-tCD19 or UAS-CD123-BBz-tCD19 that was subsequently used for enrichment and detection. Uniframe constructs were designed placing UAS-CAR at the 5′ position of the PGK-SynNotch sensor to prevent expression of the PGK-promoter_pHR_Gal4UAS_tBFP_PGK_mCherry (Addgene plasmid# 79130) was used for reporter BFP studies.

Flow Cytometry and Cell Enrichment

All samples were analyzed using an LSR II, CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter), FACSymphony or FACSAria II using FACSDiva software (v8.0.; BD Bioscience) and CytExpert (v2.5; Beckman Coulter) and data were analyzed using FlowJo X 10.6. CD33 and CD123 SynNotch receptors and the CARs were detected using goat anti-mouse F(ab′)2 fragment-specific antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) or for high precision using histag-CD33 and histag-CD123 proteins (Sino Biological). Expression of upstream activation sequence (UAS) B7H3-PgK-tCD19 was detected using an anti-CD19 antibody (BioLegend) for the double-hit products and the SynNotch receptor for the single frame constructs. For cell number quantitation, CountBright beads (Invitrogen) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antigen density for CD33 and CD123 was measured using Quantibrite beads (BD Biosciences) and 1:1 PE-conjugated CD33 and CD123 antibodies (BD Biosciences) per the manufacturer’s recommendation. In all analyses, the population of interest was gated based on forward and side scatter characteristics, followed by singlet gating. Live cells were gated using Live Dead Fixable. DAPI or Zombie UV (BioLegend). In vitro, experiments were performed on sorted CAR-T cells CAR+ or SynNotch+/UAS_CAR+ population. T cells were sorted and expanded for 2 weeks on day 5 after transduction. A histogram depicting the antigen density of CD33 and CD33 was performed using identical cell counts and identical antibody concentrations to maintain reliable comparisons between measurements. We used monocytes isolated from three healthy PBMC donors (EasySep isolation kit).

Cytokine Analysis and Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytokine Analysis

Cytokine production was assayed by ELISA of supernatant harvested from wells containing CAR-T cells co-incubated with target tumor cells at a 1:1 ratio (1 × 106 cells each) for 48 hours. Harvested supernatants were analyzed using Human Cytokine Array Pro-Inflammatory Focused 13-Plex (HDF13; Eve Technologies).

Cytotoxicity Assay

Calculated T-cell E:T ratios were based on the transduction efficiency of CAR-T cells. The total number of T cells in cytotoxicity experiments was adjusted to remain the same across experimental groups by adding untransduced T cells. GFP-labeled tumor cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2.5 × 103 cells/well), followed by the addition of CAR-T cells in defined E:T ratios (n = 4 per E:T evaluation) in a final well volume of 200 μL of T-cell media and placed in an Incucyte S3 Live-Cell Analysis System (v2018B, Essen BioScience). The integrated green fluorescent intensity or green fluorescent–positive cell count per well was calculated using Incucyte software and standardized to baseline wells.

In Vivo Studies

Xenograft studies were performed using NSG mice (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid ILrgtm1Wjl/SzJ, The Jackson Laboratory) at 6 to 12 weeks of age. Only female mice were used in AML experiments. The NSG mice were inoculated intravenously with MOLM13, KG1 luciferase-expressing AML cells. Mice were injected with 1 to 10 × 107 transduced or untransduced T cells, depending on the experiment. NOD Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl Tg (CMV-IL3, CSF2, and KITLG) 1Eav/MloySzJ (NSG-SGM3) mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were conditioned with sublethal (1.2 Gy) total body irradiation. Human CD34+ mobilized BM-derived stem cells (5 × 105–1 × 106) were injected intravenously into the mice within 8 to 24 hours after total body irradiation. Six to eight weeks later, mice were treated with 3 to 5 × 106 CAR-T cells as described in the individual experiments. Humanized NSG and SGM3 experiments at expedited schedule were established from expanded CD34 cells from healthy donors and followed the methods and inoculation schedule for AML, CAR-T cells, and marrow evaluation as described (27). Like in vitro experiments, the total number of T cells given to animals was the same across the treatment cohorts, and untransduced T cells were added to CAR-T cells based on their transduction efficiency. Xenogen IVIS Lumina (Caliper Life Sciences) or LagoX II (Spectral Instruments Imaging) was used to monitor disease burden and progression. Xenogen images of mice were taken 15 minutes after injecting 1.5 mg D-luciferin (Caliper Life Sciences) intraperitoneally. For all experiments, the Xenogen exposure time was set at autocollection. Luminescence images were analyzed using Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences) or Aerus software for images obtained using LagoX. Peripheral blood was collected from the retro-orbital venous system or tail vein. All mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions and housed in the Saban Research Institutes’ Animal Facility. All animal studies were conducted in accordance with and approved by the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals injected with tumor cell lines were monitored weekly until they developed clinical symptoms, which were monitored daily. Animals meeting study criteria, including weight loss >15%, significant change in behavior, seizure, or decreased mobility, were euthanized according to the approved procedures. The primary endpoint of all animal studies was survival, which was analyzed using the log-rank Mantel–Cox test.

Methylcellulose Colony-Forming Assay

Mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells were obtained from the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles biorepository with written informed consent according to protocols approved by the institutional review board. After incubation without CAR or with untransduced or constitutively expressed CD123 CAR-T or the CD123 CAR expressed through the CD33 SynNotch sensor for 24 hours. CD34+ cells were then sorted on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences) and resuspended in 400 μL Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium with 4 mL MethoCult H4435 (STEMCELL Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and plated in triplicate in six-well SmartDish (STEMCELL Technologies) plates at 1 × 103 cells per well. Plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 14 days. After 14 days, colonies were scored on an inverted microscope (brand, magnification) for the quantity of erythroid (BFU-E/CFU-E) or CFU-G/M/GM colonies.

Analysis of scRNA-seq Data

The splenic cells of the humanized mice treated with constitutively expressing UT, CD123, or the CD33→CD123 CAR-T cells were enriched using the mouse or human CD45 mojosort (BioLegend). Enriched human and mouse cells were then remixed back at a 1:1 ratio for the Hashing (BioLegend) before being loaded to the 10× genomics platform performed at SC2 core at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Processed scRNA-seq data (cell by gene counts table) were analyzed using Seurat v5. In brief, low-quality cells containing fewer than 200 genes, fewer than 500 counts, or more than 40% (human) or 35% (mouse) mitochondrial reads, or more than 30,000 UMI (human), 50,000 UMI (mouse) were removed. Counts were depth-normalized to a sum of 10,000 per cell and then log-transformed with a pseudocount of 1. The top 2,000 variable genes were identified, and the effects of the number of genes detected per cell were regressed. Variable genes defined by Seurat as follows: FindVariableGenes (mean.function = ExpMean, dispersion.function = LogVMR, x.low.cutoff = 0.0125, x.high.cutoff = 3, y.cutoff = 0.5). Cell cycle regression was done as described (41). PCA was performed with default settings on highly variable genes using FindClusters (reduction.type = “pca,” dims.use = 1:10, resolution = 1). Gene expression was then visualized via the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection as the log depth-normalized counts. Using Partek Flow, we analyzed gene expression data to develop biomarkers for each splenic cluster within the human and murine CD45+ populations of humanized mice. These biomarkers were then input into the CellMarker algorithm https://uncurl.cs.washington.edu/db_query to annotate the cell clusters. For further characterization, we then performed hurdle differential gene expression analysis between gated versus constitutively expressed compartments of each collective cellular cluster, followed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (version 01-22-01). The outcome was displayed as the organic view of predicted activated or inhibited cellular pathways.

Bulk RNA-seq

Bulk RNA was isolated from constitutively expressed CD123 or gated SynNotch CD33→CD123 CAR-T cells 48 hours after coculture with the MOLM13 AML cell line. We performed CD3+ cell (mojosort, BioLegend) enrichment to ensure any AML cell contamination despite cytotoxicity data suggesting leukemia cells have been eliminated at a 48-hour time point. Total RNA was isolated from 5 × 106 cells using Qiagen RNeasy Isolation Kit. Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed by Novogene using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, 150-bp paired-end reads, at 18 to 34 million reads per sample. RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy Mini Plus Kit (Qiagen). RNA quality was verified, and next-generation sequencing was performed by Novogene. Reads were quantified using Salmon (v1.2.0) using the human transcriptome (GRCh38.p13, Ensembl release 99) as the reference. Transcript annotation was performed, and differentially expressed genes were identified using DESeq2 (v1.28.1). Genes were selected at ≥twofold difference and P value ≤ 0.05. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using default parameter settings using published gene sets (MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb). Including Significance was defined as FDR < 0.05. R (ver 3.4) was used to visualize the data.

Viral Copy Number Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from 1 to 2 million T cells using the Invitrogen PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit. The DNA was diluted to 25 ng/µL in low EDTA buffer. PCR reactions were prepared by combining 4× Probe Master Mix, Primer Probe Master Mixes for the target gene (HIV U3) and reference gene (RPP30), EcoRI, diluted DNA, and ddH2O. After vortexing and a 10-minute incubation at room temperature, the reactions were transferred to a nanoplate, sealed, and run on a PCR machine. The viral copy number was determined by comparing the amplification of the target gene to the reference gene.

Statistical Analysis

All statistics were performed as indicated using GraphPad Prism version 10.0. The two-tailed Student t test was used to compare two groups; in an analysis in which multiple groups or timelines were compared, a one-way ANOVA was performed. When multiple groups at multiple time points/ratios were compared, Student t tests or ANOVAs for each time point/ratio were used. Each graph represents three biological replicates unless otherwise noted in the figure legend. The P value of each experiment is inserted in the graph when applicable.

Data Availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Raw RNA-seq data supporting the findings of this study was deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus accession numbers GSE282690 and GSE282431. The primary constructs will be available for researchers under an appropriate Material Transfer Agreement.

Supplementary Material

Single cell data of the clusters, gene expresion, biomarker and called annotations

additional and extended data from stuying constituitive and gated CAR-T cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Hyundai Hope On Wheels (B. Moghimi), St. Baldrick’s Foundation (B. Moghimi), Couples Against Leukemia Foundation (B. Moghimi), CureSearch for Children’s Cancer (B. Moghimi), University of Southern California leukemia affinity group pilot fund (B. Moghimi), Saban Research Institute core pilot funds (B. Moghimi), and Saban Research Institute fellowship award (S. Jambon and S. Barman). The Saban Research Institute supports the small animal imaging core and flow cytometry core facilities at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. The University of Southern California bioinformatic core supports Partek Flow and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Blood Cancer Discovery Online (https://bloodcancerdiscov.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors’ Disclosures

B.L. Wood reports personal fees from Amgen outside the submitted work, and reports that his laboratory performs contract research testing to support clinical trials for the following biopharma companies: Novartis, Amgen, BioSight, Wugen, and Beam. A.S. Wayne reports other support from Kite, a Gilead company, outside the submitted work. M.A. Pulsipher reports personal fees from CARGO Therapeutics, Garuda, Autolus, Pfizer, Novartis, GentiBio, bluebird bio, Vertex, Medexus, and Equillium and nonfinancial support from Adaptive and Miltenyi outside the submitted work. Y.-M. Kim reports nonfinancial support and other support from OncoSynergy outside the submitted work. C. Parekh reports a patent for BCL11B Overexpression to Enhance Human Thymopoiesis and T-cell Function, PCT/US20/39414 (PCT application filed, June 24, 2020) pending and licensed to Pluto Immunotherapeutics Inc.; ownership of Amgen stock by his spouse; ownership of equity in Pluto Immunotherapeutics Inc.; and receiving royalty payments from Pluto for technology licensed to Pluto. B. Moghimi reports grants from Hyundai Hope On Wheels Foundation, Couples Against Leukemia Foundation, St. Baldrick’s Foundation, CureSearch for Children’s Cancer Foundation, The Saban Research Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, and University of Southern California during the conduct of the study. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Authors’ Contributions

S. Jambon: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, software, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing. J. Sun: Conceptualization, data curation, software, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. S. Barman: Formal analysis, investigation, visualization, methodology. S. Muthugounder: Data curation, validation, investigation. X.R. Bito: Data curation. A. Shadfar: Data curation. A.E. Kovach: Data curation, software, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, writing–original draft. B.L. Wood: Data curation, software, formal analysis, supervision, investigation, visualization, writing–original draft. V. Thoppey Manoharan: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, software, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing. A.S. Morrissy: Data curation, software, supervision, validation, visualization, methodology. D. Bhojwani: Resources, supervision, validation, methodology. A.S. Wayne: Resources, supervision. M.A. Pulsipher: Supervision. Y.-M. Kim: Resources, investigation. S. Asgharzadeh: Resources, supervision, investigation. C. Parekh: Data curation, software, formal analysis, supervision, validation, visualization, methodology. B. Moghimi: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, software, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration; Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdel-Rahman O, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of Life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990–2017. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:1749–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perna F, Berman SH, Soni RK, Mansilla-Soto J, Eyquem J, Hamieh M, et al. Integrating proteomics and transcriptomics for systematic combinatorial chimeric antigen receptor therapy of AML. Cancer Cell 2017;32:506–19.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perna F, Berman S, Mansilla-Soto J, Hamieh M, Juthani R, Soni R, et al. Probing the AML surfaceome for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) targets. Blood 2016;128:526. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haubner S, Perna F, Köhnke T, Schmidt C, Berman S, Augsberger C, et al. Coexpression profile of leukemic stem cell markers for combinatorial targeted therapy in AML. Leukemia 2019;33:64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thol F, Schlenk RF. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia revisited. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2014;14:1185–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amadori S, Suciu S, Selleslag D, Aversa F, Gaidano G, Musso M, et al. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin versus best supportive care in older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy: results of the randomized phase III EORTC-GIMEMA AML-19 trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:972–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sievers EL, Larson RA, Stadtmauer EA, Estey E, Löwenberg B, Dombret H, et al. Efficacy and safety of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in patients with CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:3244–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu Y, Wang S, Schubert M, Lauk A, Yao H, Blank MF, et al. CD33-directed immunotherapy with third-generation chimeric antigen receptor T cells and gemtuzumab ozogamicin in intact and CD33-edited acute myeloid leukemia and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Int J Cancer 2022;150:1141–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arndt C, Feldmann A, Koristka S, Cartellieri M, von Bonin M, Ehninger A, et al. Improved killing of AML blasts by dual-targeting of CD123 and CD33 via unitarg a novel antibody-based modular T cell retargeting system. Blood 2015;126:2565. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kenderian SS, Ruella M, Shestova O, Klichinsky M, Aikawa V, Morrissette JJD, et al. CD33-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells exhibit potent preclinical activity against human acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2015;29:1637–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reinhardt D, Zwaan CM, Sander A, Neuhoff C, Kaspers GJ, Creutzig U. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in refractory childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2010;116:1075. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hasle H, Abrahamsson J, Forestier E, Ha S-Y, Heldrup J, Jahnukainen K, et al. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin as postconsolidation therapy does not prevent relapse in children with AML: results from NOPHO-AML 2004. Blood 2012;120:978–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jin L, Lee EM, Ramshaw HS, Busfield SJ, Peoppl AG, Wilkinson L, et al. Monoclonal antibody-mediated targeting of CD123, IL-3 receptor alpha chain, eliminates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009;5:31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mardiros A, Forman SJ, Budde LE. T cells expressing CD123 chimeric antigen receptors for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol 2015;22:484–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Testa U, Pelosi E, Frankel A. CD 123 is a membrane biomarker and a therapeutic target in hematologic malignancies. Biomark Res 2014;2:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baroni ML, Sanchez Martinez D, Gutierrez Aguera F, Roca Ho H, Castella M, Zanetti S, et al. 41BB-based and CD28-based CD123-redirected T-cells ablate human normal hematopoiesis in vivo. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roybal KT, Rupp LJ, Morsut L, Walker WJ, McNally KA, Park JS, et al. Precision tumor recognition by T cells with combinatorial antigen-sensing circuits. Cell 2016;164:770–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morsut L, Roybal KT, Xiong X, Gordley RM, Coyle SM, Thomson M, et al. Engineering customized cell sensing and response behaviors using synthetic Notch receptors. Cell 2016;164:780–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roybal KT, Williams JZ, Morsut L, Rupp LJ, Kolinko I, Choe JH, et al. Engineering T cells with customized therapeutic response programs using synthetic Notch receptors. Cell 2016;167:419–32.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gordon WR, Zimmerman B, He L, Miles LJ, Huang J, Tiyanont K, et al. Mechanical allostery: evidence for a force requirement in the proteolytic activation of Notch. Dev Cell 2015;33:729–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moghimi B, Muthugounder S, Jambon S, Tibbetts R, Hung L, Bassiri H, et al. Preclinical assessment of the efficacy and specificity of GD2-B7H3 SynNotch CAR-T in metastatic neuroblastoma. Nat Commun 2021;12:511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hyrenius-Wittsten A, Su Y, Park M, Garcia JM, Alavi J, Perry N, et al. SynNotch CAR circuits enhance solid tumor recognition and promote persistent antitumor activity in mouse models. Sci Transl Med 2021;13:eabd8836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choe JH, Watchmaker PB, Simic MS, Gilbert RD, Li AW, Krasnow NA, et al. SynNotch-CAR T cells overcome challenges of specificity, heterogeneity, and persistence in treating glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med 2021;13:eabe7378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ajina A, Maher J. Strategies to address chimeric antigen receptor tonic signaling. Mol Cancer Ther 2018;17:1795–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Long AH, Haso WM, Shern JF, Wanhainen KM, Murgai M, Ingaramo M, et al. 4-1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat Med 2015;21:581–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Watanabe K, Kuramitsu S, Posey AD, June CH. Expanding the therapeutic window for CAR T cell therapy in solid tumors: the knowns and unknowns of CAR T cell biology. Front Immunol 2018;9:2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haubner S, Mansilla-Soto J, Nataraj S, Kogel F, Chang Q, de Stanchina E, et al. Cooperative CAR targeting to selectively eliminate AML and minimize escape. Cancer Cell 2023;41:1871–91.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Richards RM, Zhao F, Freitas KA, Parker KR, Xu P, Fan A, et al. NOT-gated CD93 CAR T cells effectively target AML with minimized endothelial cross-reactivity. Blood Cancer Discov 2021;2:648–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, Wierda W, Gutierrez C, Locke FL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy—assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15:47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maude SL, Barrett D, Teachey DT, Grupp SA. Managing cytokine release syndrome associated with novel T cell-engaging therapies. Cancer J 2014;20:119–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jain T, Litzow MR. Management of toxicities associated with novel immunotherapy agents in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ther Adv Hematol 2020;11:2040620719899897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Teachey DT, Lacey SF, Shaw PA, Melenhorst JJ, Maude SL, Frey N, et al. Identification of predictive biomarkers for cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Discov 2016;6:664–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Norelli M, Camisa B, Barbiera G, Falcone L, Purevdorj A, Genua M, et al. Monocyte-derived IL-1 and IL-6 are differentially required for cytokine-release syndrome and neurotoxicity due to CAR T cells. Nat Med 2018;24:739–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mandal K, Wicaksono G, Yu C, Adams JJ, Hoopmann MR, Temple WC, et al. Structural surfaceomics reveals an AML-specific conformation of integrin β2 as a CAR T cellular therapy target. Nat Cancer 2023;4:1592–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borot F, Wang H, Ma Y, Jafarov T, Raza A, Ali A, et al. Gene-edited stem cells enable CD33-directed immune therapy for myeloid malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:11978–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jayavelu AK, Wolf S, Buettner F, Alexe G, Häupl B, Comoglio F, et al. The proteogenomic subtypes of acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2022;40:301–17.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]