Abstract

Neurodegenerative tauopathies are characterized by the deposition of distinct fibrillar tau assemblies, whose rigid core structures correlate with defined neuropathological phenotypes. Essential tremor (ET) is a progressive neurological disorder that, in some cases, is associated with cognitive impairment and tau accumulation. In this study, we explored tau assembly conformation in ET patients with tau pathology using cytometry-based tau biosensor assays. These assays quantify the tau seeding activity present in brain homogenates by detecting the conversion of intracellular tau-fluorescent protein fusions from a soluble to an aggregated state. Pathogenic tau assemblies exhibit seeding barriers, where a specific assembly structure cannot serve as a template for a native monomer if the amino acid sequences are incompatible. We recently leveraged this species barrier to define tauopathies systematically by substituting alanine (Ala) into the tau monomer and measuring its incorporation into seeded aggregates within biosensor cells. This Ala scan precisely classified the conformation of tau seeds from various tauopathies. In this study, we analyzed 18 ET patient brains with tau pathology, detecting robust tau seeding activity in 9 (50%) of the cases, predominantly localized to the temporal pole and temporal cortex. We further examined 8 of these ET cases using the Ala scan and found that the amino acid requirements for tau monomer incorporation into aggregates seeded from ET brain homogenates were identical to those of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and primary age-related tauopathy (PART), and distinct from other tauopathies, such as corticobasal degeneration (CBD), chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). These findings indicate that in a pathologically confined subset of ET cases with significant tau pathology, tau assembly cores are identical to those seen in AD and PART. This could facilitate more precise diagnosis and targeted therapies for ET patients presenting with cognitive impairment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00401-024-02843-6.

Keywords: Essential tremor, Tau, Alzheimer’s disease, PART, Alanine scan

Introduction

Essential tremor (ET) is the most common movement disorder. Estimated 7 million people are affected in the United States representing 2.2% of the entire population [1, 2]. The pathophysiology of ET has not been fully elucidated, although there is mounting evidence that it is neurodegenerative, with postmortem changes observed primarily in the cerebellar cortex [3, 4]. The central clinical feature of ET is an 8–12 Hz kinetic tremor, although a variety of other forms of tremor and motor features are often present [5, 6]. Multiple studies indicate that individuals with ET have poorer cognitive performance than age-matched controls [7], and emerging evidence indicates that cognitive problems in ET progress more quickly than in controls [8]. Indeed, two prospective, population-based, epidemiological studies, in Madrid and New York, found an association between ET and dementia [9, 10]. In these studies, 11.4%–25.0% of ET cases (mean age 79.1–80.9 years) had prevalent dementia vs. only 6.0%–9.2% of controls [9, 10]. Furthermore, in both studies, the risk of incident dementia was higher among individuals with baseline ET vs. those without (relative risk [RR] = 1.64–1.89) [9, 10], and tau accumulation in ET was higher than in age-matched controls [11, 12]. The type of tau pathology in ET has not yet been clearly defined from a conformational standpoint, and the neuropathological exam of these patients has revealed patterns consistent with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and other disorders [11, 13, 14].

Brain deposition of tau assemblies defines tauopathies [15], and morphological and cellular features have been used to classify these disorders. Recently cryogenic-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has resolved the atomic structure of ex vivo tauopathy filaments, allowing the classification of tau assemblies based on their conformation [16, 17]. Cryo-EM reveals distinct tau core filament structures in AD, corticobasal degeneration (CBD), PSP, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Importantly, AD and primary age-related tauopathy (PART) uniquely share the same filament structures [17], and exhibit similar brain deposition patterns.

Cryo-EM offers atomic-level resolution of structure, yet it is expensive, labor intensive, requires significant tissue mass for extraction, and is biased because only particles chemically extracted and suitable for analysis can be studied. We recently established a rapid and unbiased in vitro approach to classify tauopathies from brain homogenates by exploiting tau seeding activity and functional genetics. Prions form “strains,” which are distinct amyloid structures that stably propagate in vivo, and drive unique patterns of neuropathology and clinical phenotypes. Variation in the amino acid sequence within the native protein recruited to a given assembly creates a “species barrier” with certain strains, such that they will not amplify in the absence of a compatible monomer. This stringency for amino acid sequence protects humans from being infected with prions derived from other species, e.g., cervids or ovines [18]. Indeed, polymorphism within the prion protein gene (PRNP) has protected individuals from contracting Kuru in New Guinea, where this transmissible prion disorder was endemic [19, 20].

Based on the concept of the species barrier, we have recently described how systematic alanine (Ala) substitution in the tau monomer (Ala scan), with subsequent measurement of its incorporation into seeded aggregates within biosensor cells, reliably classifies tau seeds derived from diverse tauopathies and correlates specifically with the protofilament folds (the single protein units of a fibril) [21]. Without defining structure per se, this approach matches the accuracy of cryo-EM in the classification of tau protofilaments, without the requirements for extraction and imaging of detergent-insoluble fibrils.

Because of the increased prevalence of cognitive impairment and tau pathology in ET, here, we aimed to determine the underlying tau seed conformation in a subset of ET patients with tau pathology. We used the Ala scan to test whether tau aggregates exhibit a unique conformation. Using cells seeded from ET cases, coupled with Ala scanning for monomer incorporation, we have found that in multiple ET cases, the amino acids required for monomer incorporation into aggregates seeded from ET brain are identical to those for AD and PART. This strongly indicates that tau seeds observed in a pathologically confined subset of patients with ET and tau pathology are fundamentally identical to those of AD and PART.

Materials and methods

Human brain samples

ET cases

The analyses included brains from 18 ET cases derived from the Essential Tremor Centralized Brain Repository (ETCBR), a longstanding collaboration between investigators at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Columbia University [4, 22, 23]. Established in 2003, the ETCBR banks brains from ET cases throughout the United States. ET diagnoses were carefully assigned by a neurologist specializing in tremor (E.D.L.), using three sequential methods, as has been our practice for 20 years, and as employed in over 50 publications [3, 22, 24]. First, the clinical diagnosis of ET was initially assigned by the treating neurologists, and second, confirmed by E.D.L. using semi-structured clinical questionnaires, medical records, and Archimedes spirals with the following criteria: (i) moderate or greater amplitude kinetic tremor (rating of 2 or higher [25]) in at least one of the submitted Archimedes spirals; (ii) no history of PD or dystonia; and (iii) no other etiology for tremor (e.g., medications and hyperthyroidism) [22, 24]. Third, a detailed, videotaped, neurological examination was performed, from which action tremor was rated and a total tremor score assigned (range 0–36 [maximum]) [22, 24]. These data were used to assign a final diagnosis of ET [22, 24], reflecting published diagnostic criteria [moderate or greater amplitude kinetic tremor (tremor rating ≥ 2) during three or more activities or a head tremor in the absence of PD or other known causes] [25], of demonstrated reliability and validity [26, 27]. No ET cases reported a history of traumatic brain injury, exposure to medications associated with cerebellar toxicity (e.g., phenytoin, chemotherapeutic agents), or heavy ethanol use [28]. Every 6–9 months, a follow-up semi-structured telephone evaluation was performed, and hand-drawn spirals were collected; a detailed, videotaped, neurological examination was repeated if there was concern about a new, emerging movement disorder.

Other tauopathy cases

The tauopathy cases used for comparison encompassed AD (N = 8), PART (N = 2), CBD (N = 8), PSP (N = 5), and CTE (N = 2) cases. The selected cases had a single confirmed histopathological diagnosis of either AD, PART, CBD, PSP, or CTE based on standard neuropathological evaluation using accepted neuropathologic consensus criteria [29–33]. The AD, PART, CBD, and PSP human brain tissue samples were obtained through the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Neuropathology Brain Bank with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Select AD, PSP, and CBD cases were also obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University in St Louis. The CTE cases were obtained from the CTE Center at Boston University. A summary of these tauopathy cases is detailed in Table 1S. The frontal gyrus was used for analysis in the AD, CBD, CTE, and PSP cases, except for three AD cases in which the parietal lobe was used (AD5, AD6, and AD7) and one case in which the temporal pole was used (AD8). The temporal lobe was used in the PART cases. Of note, the PART cases were analyzed and processed concurrently with the ET cases using the methods detailed below. The AD, CBD, PSP, and CTE tissue samples had been already prepared and analyzed in our prior work following the same protocols [21]. The results from these analyses were incorporated in this study for comparison with the ET samples.

Tissue processing and neuropathological examination of ET cases

ET brains from the New York Brain Bank had a complete neuropathological assessment with standardized measurements of brain weight and postmortem interval (hours between death and placement of brain in a cold room or upon ice) [26, 27]. Standardized blocks were harvested from each brain and processed, and 7 μm-thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections were stained with Luxol fast blue/hematoxylin and eosin (LH&E) [22, 34]. Additionally, selected sections were stained by the Bielschowsky method, and with mouse monoclonal antibodies to phosphorylated tau (clone AT8, Research Diagnostics, Flanders, NJ) and β-amyloid (clone 6F/3D, Dako, Carpenteria, CA) [22, 34]. All tissues were examined microscopically by a senior neuropathologist blinded to clinical information [22, 34]. Alzheimer’s disease staging for neurofibrillary tangles (Braak NFT) [35], Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD) ratings for neuritic plaques [26, 36], and Thal β-amyloid stages were assigned [37, 38]. For Braak NFT staging, stages I and II indicated NFTs confined to the entorhinal region, III and IV limbic region involvement (i.e., hippocampus), and V and VI moderate-to-severe neocortical involvement [35]. An additional classifier (PSP) was added for subjects that had AT8 immunohistochemical tau deposits including neurofibrillary tangles or pretangles in at least two of three regions (globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, and substantia nigra), and tufted astrocytes in at least one of two regions (peri-Rolandic cerebral cortex and putamen), according to the most recent diagnostic consensus criteria for PSP reported by Roemer et al. in 2022 [32]. The level of AD neuropathologic change (ADNC) was rated according to National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) guidelines using an “ABC” score as none, low, intermediate, or high [37].

One ET case with pathologically confirmed high ADNC was examined in this study as a positive control for detection of AD-type tau seeds (Table 1, case 1). The remaining ET cases were chosen based on the following criteria: (1) presence of no (Thal A0, CERAD C0) or few amyloid deposits (Thal A1 or CERAD C1); (2) higher Braak NFT stage (5–6), reflecting at least some extension into frontal association cortices and/or temporal pole; and/or (3) presence of PSP-type changes. Frozen samples from cerebral cortex regions including frontal (BA9), motor (BA4), parietal (BA7), occipital (BA31), temporal (BA37), and temporal pole (BA38) were assayed according to sample availability. In cases with PSP-type changes detected, cerebellar cortex and dentate nucleus were assayed, as available. Cases that had only focal PSP-type pathology not meeting current Rainwater criteria [32] were designated as “PSP-like.”

Table 1.

Demographic and neuropathologic data

| Case | Age | Sex | Neuropathologic diagnosis(es) | Thal | Braak NFT | CERAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 89 | F | ADNC, high | A3 | 6 | 3 |

| 2 | 97 | M | PSP, mild; infarcts, cortico-subcortical, old, left pre-frontal and right frontal | A1 | 6 | 0 |

| 3 | 92 | F | PSP, moderate; infarct, old, large, territory of the anterior cerebral artery, left | A0 | 6 | 0 |

| 4 | 74 | F | PSP, mild; ADNC, low | A1 | 5 | 1 |

| 5 | 91 | F | PSP, mild; ADNC, low | A1 | 3 | 1 |

| 6 | 102 | M | PSP, mild | A1 | 5 | 0 |

| 7 | 92 | M | PART; PSP-type changes, rare | A0 | 6 | 0 |

| 8 | 89 | F | PART | A0 | 5 | 0 |

| 9 | 91 | F | PSP, mild | A0 | 3 | 0 |

| 10 | 84 | F | PART; PSP-type changes, rare | A1 | 4 | 0 |

| 11 | 96 | M | PSP, moderate*; ADNC, low | A1 | 6 | 0 |

| 12 | 90 | F | PSP, mild | A1 | 5 | 0 |

| 13 | 87 | F | ADNC, low [possible PART] | A1 | 5 | 1 |

| 14 | 90 | M | PART | A0 | 5 | 0 |

| 15 | 75 | M | PART | A0 | 5 | 0 |

| 16 | 90 | F | ADNC, low [possible PART] | A1 | 5 | 1 |

| 17 | 79 | F | PART | A0 | 5 | 0 |

| 18 | 85 | F | ADNC, low [possible PART] | A1 | 5 | 0 |

ADNC Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes; Braak NFT Braak staging for neurofibrillary tangles; CERAD Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease; PART primary age-related tauopathy; PSP progressive supranuclear palsy

*PSP changes were more prominent in subcortical regions in this case

Tissue homogenization

Frozen brain was suspended in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing cOmplete mini protease inhibitor tablet (Roche) at a concentration of 10% weight/volume. Homogenates were prepared by probe homogenization using a Power Gen 125 tissue homogenizer (Fisher Scientific) in a vented hood. The homogenates were then centrifuged at 21,000×g for 20 min. The supernatant was collected as the total soluble protein lysate. Protein concentration was measured using a Pierce 660 assay (Pierce). Fractions were aliquoted into low-binding tubes (Thermo Fisher) and frozen at − 80 °C until future use.

Tau RD biosensor cell lines

The following tau repeat domain (RD) biosensor cell lines were used for tau seeding assays in this study.

Tau RD 3R-Cer/4R-Ruby (3R/4R) cells

HEK293T cells containing the 3-repeat (3R) version of the wild-type (WT) human tau RD (residues 246-408) C-terminally fused to mCerulean (Cer), and the 4R version fused to mRuby fluorescent protein (Rub) were used for tau seeding assays and the 3R/3R tau Ala scan. These biosensor cells exhibit high seeding after exposure to brain homogenates from certain tauopathies (e.g., AD) but not others (e.g., CBD) [21].

Tau RD 4R-Cer/4R-Ruby (4R/4R) cells

HEK293T cells containing the 4R version of the WT human tau RD (residues 246-408), C-terminally fused to monomeric Cerulean3 (Cer) and monomeric Ruby fluorescent protein (mRuby3) were used for tau seeding assays and the 4R/4R tau Ala scan. These biosensor cells exhibit high seeding after exposure to brain homogenates from certain tauopathies (e.g., CBD, PSP) but not others (e.g., AD) [21].

Tau (246-408) Ala scan library

The tau-(246-408)-Ala-mEOS3.2 point mutant library used in this study was previously generated and described in detail [21]. Twist Biosciences synthesized gene fragments encoding the human 2N4R tau sequence from residues 246 to 408 with Ala codon substitutions (GCC) at each position. These gene fragments were then conjugated to a common lentiviral plasmid harboring the mEOS3.2 fluorescent protein, thus generating an arrayed library of plasmids with the different sequential tau Ala point mutants fused to mEOS3.2. All plasmids were verified by Sanger sequencing.

Biosensor cell transduction with brain homogenates and tau seeding assay

Tau RD 3R-Cer/4R-Ruby (3R/4R) and Tau RD 4R-Cer/4R-Ruby (4R/4R) cells were plated at a density of 20,000 cells per well of a 96-well plate. 24 h later, the cells were transduced with a complex of 10 μg of 10% w/v brain homogenate, 0.75 μl of lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and 9.25 μl of Opti-MEM for a final treatment volume of 20 μl per well. 72 h after transduction, cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin digestion for 5 min at 37 °C, quenched with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), and transferred to 96-well U bottom plates. They were then centrifuged for 5 min at 1500 rpm, the supernatant was aspirated, and the cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. The cells were then centrifuged and resuspended in 150 μl of PBS for analysis using flow cytometry.

Ala scan

For the Ala scan incorporation assay, 3R/4R or 4R/4R biosensor cells were plated at 20,000 cells per well in 96-well plates and treated with sonicated brain homogenates as described above. After 48 h, once seeded aggregates were observed, the cells were replated at a concentration ratio of 1:6 into 6 new 96-well plates to generate technical replicates. The cells were then treated with a library of tau-(246-408)-Ala-mEOS3.2 lentivirus. One tau Ala point mutant was added per well. 72 h after transduction, the cells were harvested and fixed in paraformaldehyde as described above. The Ala scan assay determines the tau residues that are critical for monomer incorporation into seeded aggregates in each tauopathy. If a residue in tau-(246-408) is critical for incorporation into a particular tauopathy fold, substitution of that residue with Ala will block monomer incorporation, resulting in no or low detectable seeding assessed by FRET between Cer and mEOS3.2. Conversely, if a residue is non-critical for incorporation, the Ala substitution at that position will have no effect, and FRET signal will be detected. This assay generates a barcode map of critical residues for each tau fold, which can be matched to the cryo-EM structure [21].

Flow cytometry

The BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer was used to perform Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) analysis. To measure CFP or Cer signal, and FRET, cells were excited with the 405 nm laser, and fluorescence was captured with a 488/50 nm and 525/50 nm filter. To measure YFP and mEOS3.2, cells were excited with a 488 nm laser and fluorescence was captured with a 525/50 nm filter. To measure Ruby, cells were excited with a 561 nm laser and fluorescence was detected using a 610/20 nm filter.

Data analysis

Seeded 3R/4R or 4R/4R biosensor cells transduced with the tau-(246-408) Ala scan library were analyzed by gating for homogeneous side-scatter and forward-scatter. The FRET signal between Cer and Ruby, measured in the Pacific Blue and Qdot605 channels, was used to gate for cells that contained seeded aggregates in these biosensors. Within this population, a narrow gate for cells positive for FITC (non-photoconverted mEOS3.2) was selected, which corresponded to cells expressing the tau-(246-408)-Ala-mEOS3.2 point mutants. The FRET signal between Cer and mEOS3.2 was plotted within this population, and a narrow subset of bright cells were selected to calculate the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) in the AmCyan channel. All gates were kept constant across the incorporation assay and across technical replicates. The fluorescence intensity of the FRET signal in the AmCyan channel was subsequently used for the incorporation assay analysis as it served as a marker of the degree of incorporation of each tau-(246-408) Ala point mutant to the seeded aggregates within the biosensor cells. Of note, Ala point mutants K274A, T386A, and P397A were eliminated from the scan analysis due to low transduction efficiency.

Data processing

FRET median fluorescence intensity (MFI) values between Cer and mEOS3.2 measured in the AmCyan channel were normalized by plate to prevent batch variation. Within our analysis, most Ala residues in the N- and the C-termini of the sequence did not impact incorporation. Thus, we used these values, and the lowest value in each plate to normalize the data and obtain the Incorporation Value for each residue position, following this formula:

where Residue MFI x is the FRET MFI in the AmCyan channel for each position, Minimum MFI is the minimum FRET value in the scan, and Average MFI is the Average MFI for the first 20 residues (on the first plate) or the last 10 residues (on the second plate). The average of three technical replicates was used for downstream analysis.

Results

Case characteristics

We studied 18 ET cases (Table 1). One exhibited prominent Aβ pathology and high Braak NFT stage, leading to a postmortem diagnosis of high ADNC (case 1). The other 17 cases consisted of cases with high NFT burden (Braak NFT ≥ 3) or PSP findings, and low-to-absent Aβ pathology as assessed by Thal and CERAD staging. These cases had received additional postmortem diagnoses of PSP and PART. Two cases had old infarcts, which were outside of the regions sampled in tau seeding analyses.

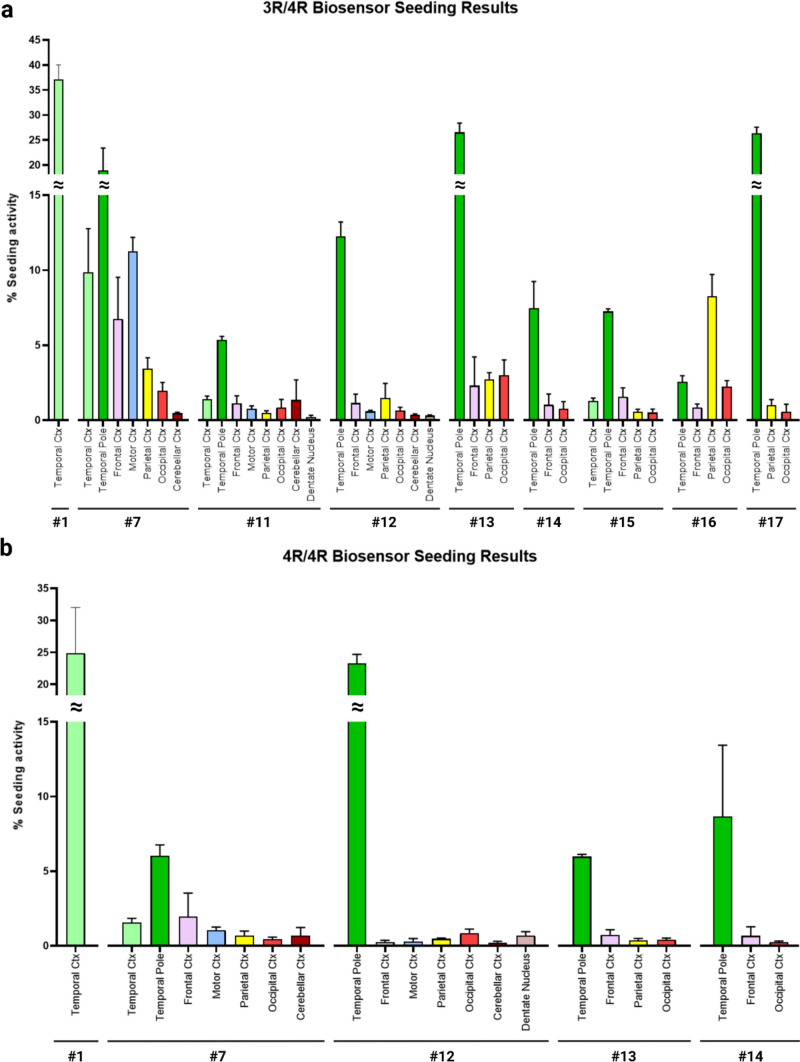

ET cases with high NFT burden exhibit tau seeding activity

We first tested whether ET brain homogenates (Table 2) from multiple brain regions seeded 3R/4R (as observed in AD or PART), or 4R/4R biosensors (as observed in CBD, CTE, and PSP) (Fig. 1S). Multiple cases (9/18, 50%) exhibited robust seeding activity at or above 5% FRET positive cells predominantly on 3R/4R biosensors. In these cases, the temporal cortex and temporal pole regions scored highest (cases 1, 7, 11–15, 17) (Fig. 1a). In case 16, the parietal cortex scored highest. For some, we observed equivalent seeding on 3R/4R and 4R/4R biosensors (cases 1, 7, 12–14) (Fig. 1b). Given that ET patients exhibit degenerative changes in and around Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex [3, 4, 39, 40], we also tested the cerebellar cortex and dentate nucleus, which had low or absent seeding in all cases. The other ET cases (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 18) exhibited no or low tau seeding (below 5%) that was insufficient to extract a reliable profile using the Ala scan (Fig. 1S).

Table 2.

Regions used for Tau seeding analysis

| Case | Age | Sex | TC (BA37) | TP (BA38) | FC (BA9) | MC (BA4) | PC (BA7) | OC (BA31) | Cbl Ctx | DN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 89 | F | X | |||||||

| 2 | 97 | M | X | X | ||||||

| 3 | 92 | F | X | X | X | |||||

| 4 | 74 | F | X | X | X | |||||

| 5 | 91 | F | X | X | ||||||

| 6 | 102 | M | X | X | X | |||||

| 7 | 92 | M | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 8 | 89 | F | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| 9 | 91 | F | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 10 | 84 | F | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 11 | 96 | M | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 12 | 90 | F | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 13 | 87 | F | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 14 | 90 | M | X | X | X | |||||

| 15 | 75 | M | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| 16 | 90 | F | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 17 | 79 | F | X | X | X | |||||

| 18 | 85 | F | X |

TC temporal cortex; BA Brodmann area; TP temporal pole; FC frontal cortex; MC motor cortex; PC parietal cortex; OC occipital cortex; Cbl Ctx cerebellar cortex; DN dentate nucleus

Fig. 1.

ET cases exhibit seeding in tau biosensor cells. Brain homogenates from ET patients were transduced into 3R/4R (a) and 4R/4R (b) biosensor cells. ET cases with tau seeding are reported. Strong seeding was recorded primarily in the temporal pole and the temporal cortex, except in case 16 (parietal cortex). Cases 1, 7, 12–14 had similar seeding in 3R/4R and 4R/4R biosensors. Ctx cortex

Ala scan in ET cases is identical to AD and PART

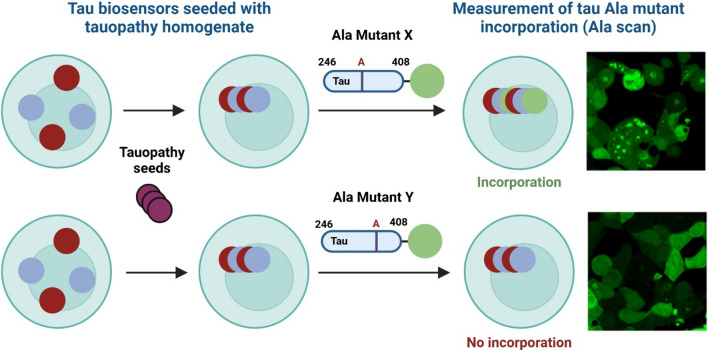

To evaluate the conformation of the tau assemblies in ET cases, which varied widely in their postmortem diagnoses, we used the recently validated Ala scan. We analyzed 8 ET cases where sufficient tissue with seeding activity was available (Table 3). Case 16 could not be completed due to insufficient tissue availability despite having ≥ 5% seeding on 3R/4R biosensors. The Ala scan is based on a two-step process in which brain homogenates are seeded into appropriate biosensors containing 3R/4R or 4R/4R tau RD, followed by exposure to lentiviruses individually expressing 4R tau monomer with Ala substitutions through the RD (246-408) (Fig. 2). Prior data indicated that tauopathies may be discriminated in part by whether they seed more efficiently onto 3R/4R biosensors (e.g., AD) vs. 4R/4R biosensors (e.g., PSP, CBD) [21, 41, 42]. The effect of each Ala point substitution on the incorporation of tau monomers into seeded aggregates serves as a conformational 'fingerprint' of the underlying tau aggregate. This fingerprint can accurately identify the specific type of tauopathy [21].

Table 3.

Cases selected for 3R/4R Ala scan

| Case # | Age | Sex | ≥ 5% Seeding on 3R/4R | Region for 3R/4R Ala scan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 89 | F | Yes | Temporal cortex |

| 2 | 97 | M | No | – |

| 3 | 92 | F | No | – |

| 4 | 74 | F | No | – |

| 5 | 91 | F | No | – |

| 6 | 102 | M | No | – |

| 7 | 92 | M | Yes | Temporal pole |

| 8 | 89 | F | No | – |

| 9 | 91 | F | No | – |

| 10 | 84 | F | No | – |

| 11 | 96 | M | Yes | Temporal pole |

| 12 | 90 | F | Yes | Temporal pole |

| 13 | 87 | F | Yes | Temporal pole |

| 14 | 90 | M | Yes | Temporal pole |

| 15 | 75 | M | Yes* | – |

| 16 | 90 | F | Yes | Parietal cortex |

| 17 | 79 | F | Yes | Temporal pole |

| 18 | 85 | F | No | – |

*An Ala scan was not completed for Case #15 despite > 5% seeding due to insufficient tissue availability

Fig. 2.

Tau Ala scan diagram. Biosensor cells (i.e., 3R/4R or 4R/4R) were seeded with brain homogenate from different tauopathies. Once tau seeding was detected, the cells were then transduced with lentivirus containing a library of tau Ala point mutants (e.g., Mutant X, Mutant Y) spanning residues 246–408 in 2N4R tau conjugated to fluorophore mEOS3.2. The appropriate positive and negative controls were also added. If a residue in tau-(246-408) is critical for incorporation into a particular fold, substitution of that residue with Ala will block monomer incorporation, resulting in no or low detectable FRET signal (Mutant Y). Conversely, if a residue is non-critical for incorporation, the Ala substitution at that position will have no effect, and FRET signal will be detected (Mutant X). This assay generates a barcode map of critical residues for each tau fold, which can be faithfully mapped to critical residues in the cryo-EM structure of each fold (generated with Biorender)

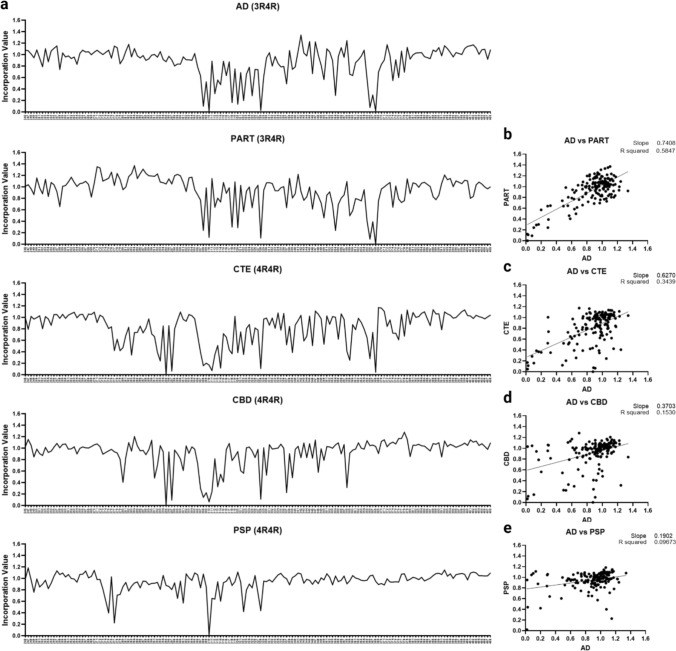

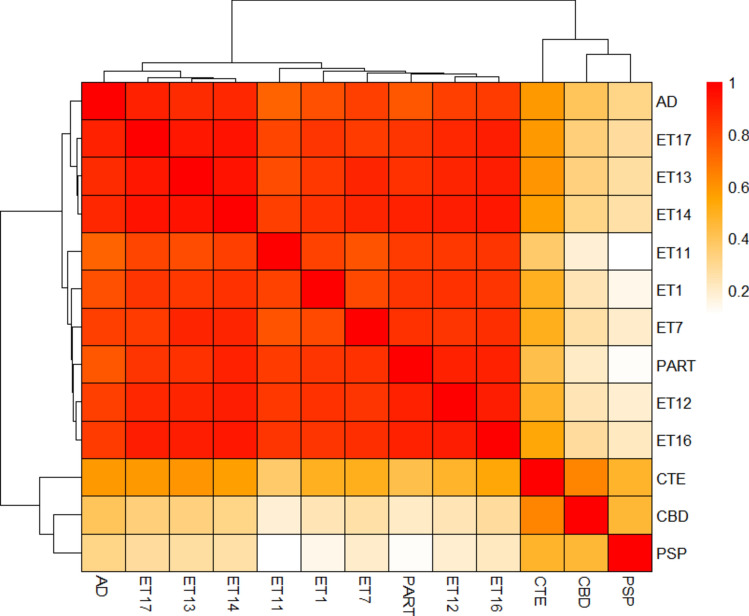

To first confirm the Ala scan fidelity, we scanned PART cases, which feature identical cryo-EM filament structures to AD cases [21]. The PART (N = 2) and AD cases (N = 8) showed preferential seeding on 3R/4R biosensors and their 3R/4R Ala scan average profiles were indistinguishable (Fig. 3). This contrasted with the Ala scan profiles observed for other tauopathies (CTE, PSP, and CBD), which correspond to different cryo-EM structures [21].

Fig. 3.

Tau Ala scan for AD, PART, CTE, PSP, and CBD cases. AD, PART, CTE, CBD, and PSP case brain homogenates were incubated with 3R/4R (AD, PART) or 4R/4R (CTE, PSP, CBD) biosensors based on preferential seeding. After 48 h (to allow inclusion formation), cells were plated in triplicate and incubated with the tau-(246-408)-Ala-mEOS3.2 mutant lentivirus library. a Line plots of the average tau Ala scans for AD (N = 8), PART (N = 2), CTE (N = 2), CBD (N = 8), and PSP (N = 5). Y axis: incorporation value: normalized incorporation value (Cer-mEOS3.2 FRET MFI) for each residue position. X axis: residue positions. b AD and PART scans were highly correlated. AD scans did not correlate with c CTE; d CBD; e PSP

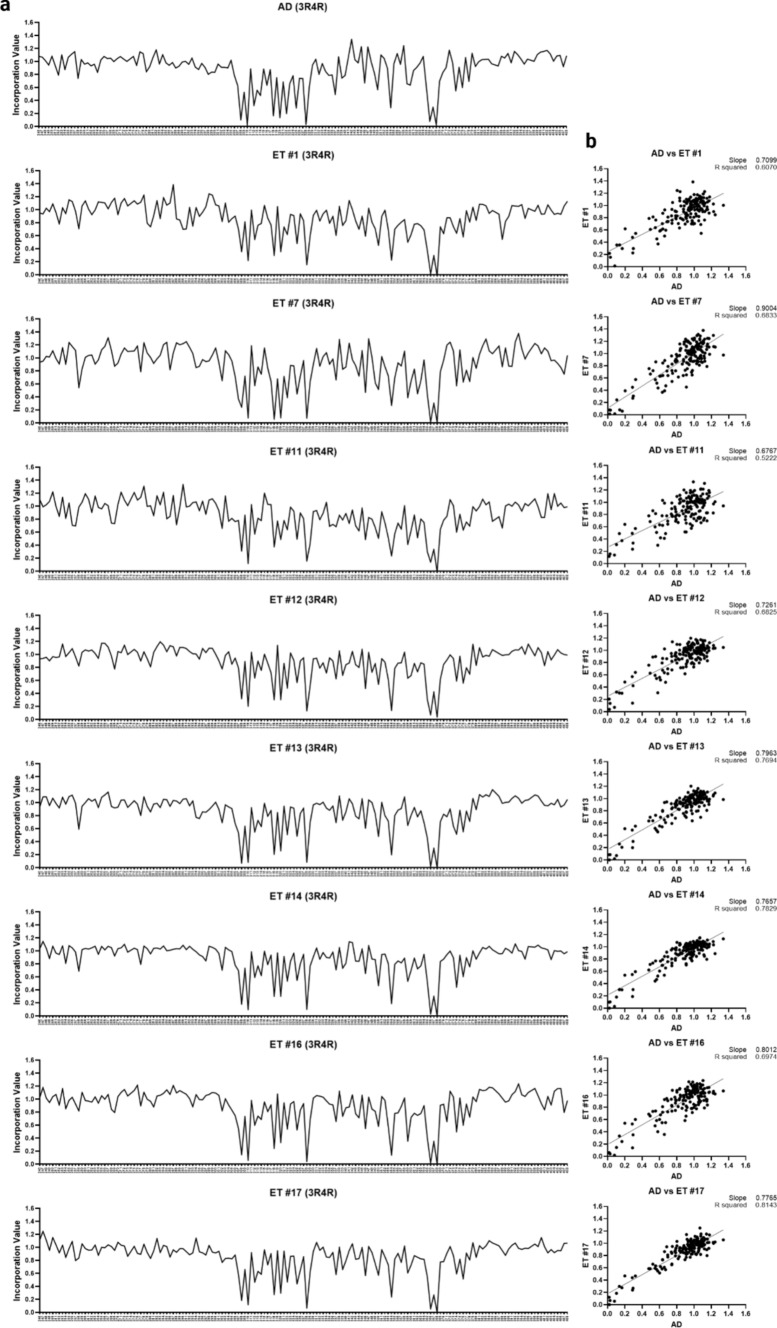

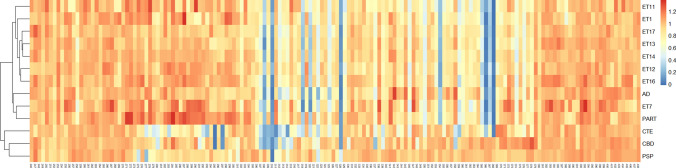

All ET homogenates seeded on 3R/4R biosensors. To obtain signal sufficient for the 3R/4R Ala scan, we selected brain regions with the highest level of seeding. We used the temporal cortex of case 1; the temporal pole of cases 7, 11–14, and 17; and the parietal cortex of case 16. The Ala scan of each ET case was identical to AD and PART (Fig. 4). To assess this in an unbiased fashion, we used cluster analysis to group cases according to similarity (Fig. 5). Confirming their similarity, the average AD and PART Ala scan profiles were admixed with the ET cases, and distinct from other tauopathies. The CTE case exhibited a partial correlation with these cases, consistent with the structural similarity of the CTE vs. AD and PART protofilament folds [17, 21]. We observed poor correlation with the CBD and PSP cases (Fig. 5). When all the individual cases across tauopathies were compared, the AD, PART, and ET were also found to be admixed (Fig. 2S). To compare the residue hits across cases, we used heat map analysis, which also highlighted the similarities between ET, AD, and PART, with hits at positions I308, Y310, V318, S320, I328, I354, G366, and N368 (Fig. 6). As a supplementary analysis, we performed a cluster analysis including only the ET cases (Fig. 3S). The results showed a high agreement between the cases. When the average Ala scan profiles for each tauopathy were mapped including the standard deviation (SD) of the samples, the residue hits were found to be consistent across cases for each diagnosis, including in ET (Fig. 4S).

Fig. 4.

3R/4R tau Ala scan of ET cases. Brain homogenates from the highest seeding regions (cases 1, 7, 11–14, 16) were transduced into 3R/4R biosensors. After 48 h, the cells were incubated with the tau-(246-408)-Ala-mEOS3.2 mutant lentivirus library. a Line plots of the 3R/4R Ala scan replicates indicate effects of substitution for each residue in the average AD profile and each ET case. Y axis: incorporation value: normalized incorporation value for each residue position. X axis: residue positions. b Each ET case Ala scan correlated highly with the average AD 3R/4R Ala scan

Fig. 5.

Cluster analysis of ET cases, AD, PART, CTE, CBD, and PSP based on the tau Ala scan. Cluster analysis of the Ala scans for individual ET cases reveals clustering of these cases with the average Ala scans for AD and PART. In contrast, the average Ala scans for CTE, CBD, and PSP cases show poor correlation with the individual ET cases

Fig. 6.

Heatmap incorporation profile of the tau Ala scan for ET, AD, PART, CTE, CBD, and PSP. The heatmap shows the individual Ala scan incorporation profiles for the ET cases and the averaged profiles for AD, PART, CTE, CBD, and PSP. Similar tau Ala hits are observed in ET cases, AD, and PART at residue positions I308, Y310, V318, S320, I328, I354, G366, and N368

As mentioned above, five ET cases exhibited seeding (≥ 5%) on 4R/4R biosensors in addition to the 3R/4R biosensors (cases 1, 7, 12–14). As an additional analysis (Fig. 5S), we performed a 4R/4R Ala scan of these cases. For comparison, we also seeded an AD case on 4R/4R biosensors, where we were able to extract a profile, despite lower seeding efficiency compared to 3R/4R (Fig. 5S). Given that cases 7 and 12 had a neuropathological diagnosis of PSP, we also compared their profiles to the 4R/4R Ala scan of PSP. The results showed that, despite lower resolution than the 3R/4R Ala scan, the 4R/4R Ala scan profile of these ET cases resembled the pattern observed for AD. Meanwhile, the cases did not match the PSP profile.

Discussion

ET is recognized as a neurodegenerative disease primarily characterized by cerebellar cortical degeneration [3, 4, 43, 44]. A notable and poorly understood aspect of ET is the increased risk for developing Lewy body [45] and tau pathologies [11, 13, 14]. Clinically, this translates into a substantially higher risk for PD [46] and dementia [10] in ET patients compared to those without ET. It is well known that ET cases exhibit a higher pathological tau burden and cognitive impairment when compared to age-matched controls [11, 13, 14]. Our study revealed that in ET cases where tau seeding was present, the tau seed conformation assessed by the Ala scan matched the profile in AD and PART, and differed from other tauopathies, such as CBD, CTE, and PSP. This suggests that a subset of ET cases with tau pathology harbor tau assemblies indistinguishable from those in AD and PART.

A subset of ET patients exhibit tau seeding

Experimental and observational evidence suggests that progression and diversity of neurodegenerative tauopathies is based on prion mechanisms, whereby a pathological assembly that forms in one cell can escape, enter a connected cell, and serve as a template for its own replication [41]. This process has been replicated in simple biosensor cell models such as the ones used here [47, 48]. This study is the first to identify tau seeding across multiple brain regions in ET patients with tau pathology, indicating that a subset of these patients features tau assemblies capable of propagation. Tau seed deposition and propagation may explain the origin and progression of cognitive impairment in ET [49–52]. Our findings are supported by prior neuropathological studies which revealed that ET patients have a tau NFT burden greater than expected for age [11], including in cognitively normal cases [11, 12]. These subjects had a higher Braak NFT stage than controls, with similar CERAD scores for neuritic plaques [12]. Interestingly, although ET patients exhibit degenerative changes in and around Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex [3, 4, 39, 40], we observed no/low tau seeding in the cerebellar cortex and dentate nucleus of these patients. This is in line with our prior work that has identified no/low tau seeding in the cerebellum of tauopathy patients [53, 54], which may suggest a paucity of tau seeds in this region.

Tau assemblies in ET have conformational characteristics of AD and PART

We have recently determined that the amino acid requirements for monomer incorporation into a pre-existing tau aggregate seeded by brain homogenate (Ala scan) precisely classifies tauopathies [21]. Here, we determined that 8 ET brain homogenates exhibited Ala scans identical to AD and PART, and completely distinct from other major tauopathies. Without cryo-EM analysis, the current state-of-the-art, it is not possible to determine the structure of tau assemblies in ET, but the Ala scan is an unbiased, functional genetic analysis with proven power. Importantly, given the low requirements for brain tissue (approximately 1000 µg/scan), it can be applied in situations where a sufficient mass of tau assemblies may not be extractable for cryo-EM. Based on the conformation of tau seeds, our findings place ET patients with tau pathology in the same pathological category as AD and PART [17]. While AD typically does not seed efficiently onto 4R/4R biosensors, we observed a subset of ET cases that efficiently seeded both 3R/4R and 4R/4R biosensors (cases 1, 7, 12–14). However, when we performed a 4R/4R Ala scan analysis of these cases, the profile matched that observed for the 4R/4R Ala scan in AD, although the seeding efficiency for these cases in these biosensors was higher than that of AD. While Ala scans were identical, this could indicate that the tau isoform composition in some ET cases differs from that of AD and PART [13], as 4R tau aggregates typically seed efficiently onto 4R/4R biosensors. In ET, seeding primarily localized to the temporal pole and temporal cortex, matching a pattern that can be observed in AD and PART. However, in one case, seeding was primarily located in the parietal cortex (case 16), and in three cases, it was detected in the occipital cortex (cases 7, 13, 16), with minimal or absent Aβ pathology. This pattern is atypical for the distribution of NFT pathology typically observed in PART or AD [30], and, in line with prior work [13], may be a neuropathological indicator that the tau isoform composition varies in some of these ET patients.

Prior work has evidenced that ET patients may have an increased predisposition to developing PSP neuropathological changes when compared to the general population [14]. Notably, although some of the cases analyzed in our study had a concurrent neuropathological diagnosis of PSP (cases 7, 11, 12), the Ala scan profiles for these cases did not match that of PSP. Notably, in cases 7 and 12, we completed an Ala scan in 3R/4R and in 4R/4R biosensors, and in neither of them did the profile resemble PSP. However, one must consider that the area used for analysis in this study (temporal pole/temporal cortex) was not the optimal to detect PSP-type changes. The presence of AD and PSP co-pathology has been described in advanced dementia [55]. Given this, we cannot rule out that a PSP fold may be present in other brain regions that have not been sampled in this study. Thus, further assessment with sampling of additional regions will be necessary.

Study limitations

One key limitation of our study is that it was restricted to ET patients with tau pathology. Therefore, these findings cannot be generalized to all patients with ET, but only to those in which tau pathology with seeding is present. A second limitation is the restricted access to different brain regions. For some of the patients, the temporal pole/cortex were the only cortical regions available for analysis. As mentioned, this may have limited the sensitivity to detect sufficient tau seeding to extract an Ala scan profile in some of these cases (9/18 cases). Future studies with more comprehensive regional sampling will help us better understand the spatial distribution of tau seeding in ET and compare it to AD and PART. Further analysis of insoluble tau isoform composition in ET will help clarify the proportion of tau isoforms involved in the pathological assemblies.

Additionally, although our study demonstrates that ET patients with tau pathology share a common tau fold with AD and PART, it does not directly address how ET may increase the susceptibility to develop this pathology, as noted in prior studies [11, 12]. More work is needed to determine whether and how ET plays a contributory role in the development of this pathology.

Clinical implications for ET patients with tau pathology

Our observations open new diagnostic and therapeutic avenues for ET with tau pathology and/or cognitive impairment. Given that a subset of cases appear to have the same underlying tau assembly conformation as AD and PART, we predict that tau positron emission tomography (PET) imaging radiotracers that are effective in AD [56–58] will also identify ET patients with tau pathology [59]. Similarly, if anti-tau therapies work in AD, they might ultimately also be effective in ET patients with tau pathology [60]. Taken together, our findings can potentially influence the care of these patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: NSC, EDL, and MID. Methodology: NSC, JVA, PLF, and CLW. Investigation: NSC, JVA, YT, PLF, and SC. Visualization: NSC, JVA, PLF, EDL, and MID. Supervision: EDL and MID. Writing—original draft: NSC, EDL, and MID. Writing—reviewing and editing: NSC, MID, JVA, PLF, and EDL.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1RF1AG065407-01A1) and the Hamon Foundation.

Data availability

All data are available without any restriction upon request to the authors or are already available in the main text and supplement.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Louis ED, McCreary M (2021) How common is essential tremor? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 11:28. 10.5334/tohm.632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis ED, Ottman R (2014) How many people in the USA have essential tremor? Deriving a population estimate based on epidemiological data. Tremor Other Hyperkinetic Mov (N Y) 4:259. 10.7916/D8TT4P4B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faust PL, McCreary M, Musacchio JB, Kuo S, Vonsattel JG, Louis ED (2024) Pathologically based criteria to distinguish essential tremor from controls: analyses of the human cerebellum. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 11:1514–1525. 10.1002/acn3.52068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louis ED, Martuscello RT, Gionco JT, Hartstone WG, Musacchio JB, Portenti M et al (2023) Histopathology of the cerebellar cortex in essential tremor and other neurodegenerative motor disorders: comparative analysis of 320 brains. Acta Neuropathol 145:265–283. 10.1007/s00401-022-02535-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louis ED (2023) Essential tremor. Handb Clin Neurol 196:389–401. 10.1016/B978-0-323-98817-9.00012-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagle Shukla A (2022) Diagnosis and treatment of essential tremor. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 28:1333–1349. 10.1212/CON.0000000000001181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghanem A, Berry DS, Burkes A, Grill N, Hall TM, Hart KA et al (2024) Prevalence of and annual conversion rates to mild cognitive impairment and dementia: prospective, longitudinal study of an essential tremor cohort. Ann Neurol 95:1193–1204. 10.1002/ana.26927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louis ED, Benito-León J, Vega-Quiroga S, Bermejo-Pareja F, Central Spain (NEDICES) Study Group (2010) Faster rate of cognitive decline in essential tremor cases than controls: a prospective study. Eur J Neurol 17:1291–1297. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03122.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bermejo-Pareja F, Louis ED, Benito-León J, Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) Study Group (2007) Risk of incident dementia in essential tremor: a population-based study. Mov Disord 22:1573–1580. 10.1002/mds.21553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thawani SP, Schupf N, Louis ED (2009) Essential tremor is associated with dementia: prospective population-based study in New York. Neurology 73:621–625. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b389f1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrell K, Cosentino S, Iida MA, Chapman S, Bennett DA, Faust PL et al (2019) Quantitative assessment of pathological tau burden in essential tremor: a postmortem study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 78:31–37. 10.1093/jnen/nly104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan JJ, Lee M, Honig LS, Vonsattel JP, Faust PL, Louis ED (2014) Alzheimer's-related changes in non-demented essential tremor patients vs. controls: links between tau and tremor? Parkinsonism Relat Disord 20(6):655–658. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SH, Farrell K, Cosentino S, Vonsattel J-PG, Faust PL, Cortes EP et al (2021) Tau isoform profile in essential tremor diverges from other tauopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 80:835–843. 10.1093/jnen/nlab073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louis ED, Babij R, Ma K, Cortés E, Vonsattel J-PG (2013) Essential tremor followed by progressive supranuclear palsy: postmortem reports of 11 patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 72:8–17. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31827ae56e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovacs GG (2015) Invited review: neuropathology of tauopathies: principles and practice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 41:3–23. 10.1111/nan.12208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzpatrick AWP, Falcon B, He S, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ et al (2017) Cryo-EM structures of Tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease brain. Nature 547:185–190. 10.1038/nature23002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Y, Zhang W, Yang Y, Murzin AG, Falcon B, Kotecha A et al (2021) Structure-based classification of tauopathies. Nature 598:359–363. 10.1038/s41586-021-03911-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groveman BR, Williams K, Race B, Foliaki S, Thomas T, Hughson AG et al (2024) Lack of transmission of chronic wasting disease prions to human cerebral organoids. Emerg Infect Dis 30:1193–1202. 10.3201/eid3006.231568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collinge J, Whitfield J, McKintosh E, Beck J, Mead S, Thomas DJ et al (2006) Kuru in the 21st century—an acquired human prion disease with very long incubation periods. The Lancet 367:2068–2074. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68930-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mead S, Whitfield J, Poulter M, Shah P, Uphill J, Campbell T et al (2009) A novel protective prion protein variant that Colocalizes with Kuru Exposure. N Engl J Med 361:2056–2065. 10.1056/NEJMoa0809716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaquer-Alicea J, Manon V, Bommareddy V, Kunach P, Gupta A, Monistrol J et al (2025) Functional classification of tauopathy strains reveals the role of protofilament core residues. Sci Adv. 10.1126/sciadv.adp5978 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louis ED, Kerridge CA, Chatterjee D, Martuscello RT, Diaz DT, Koeppen AH et al (2019) Contextualizing the pathology in the essential tremor cerebellar cortex: a patholog-omics approach. Acta Neuropathol 138:859–876. 10.1007/s00401-019-02043-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louis ED, Kuo S-H, Tate WJ, Kelly GC, Gutierrez J, Cortes EP et al (2018) Heterotopic purkinje cells: a comparative postmortem study of essential tremor and spinocerebellar ataxias 1, 2, 3, and 6. Cerebellum 17:104–110. 10.1007/s12311-017-0876-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babij R, Lee M, Cortés E, Vonsattel J-PG, Faust PL, Louis ED (2013) Purkinje cell axonal anatomy: quantifying morphometric changes in essential tremor versus control brains. Brain 136:3051–3061. 10.1093/brain/awt238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Louis ED, Ottman R, Ford B, Pullman S, Martinez M, Fahn S et al (1997) The washington heights-inwood genetic study of essential tremor: methodologic issues in essential-tremor research. Neuroepidemiology 16:124–133. 10.1159/000109681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louis ED, Ford B, Bismuth B (1998) Reliability between two observers using a protocol for diagnosing essential tremor. Mov Disord 13:287–293. 10.1002/mds.870130215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louis ED, Wendt KJ, Albert SM, Pullman SL, Yu Q, Andrews H (1999) Validity of a performance-based test of function in essential tremor. Arch Neurol 56:841–846. 10.1001/archneur.56.7.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harasymiw JW, Bean P (2001) Identification of heavy drinkers by using the early detection of alcohol consumption score. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25:228–235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bieniek KF, Cairns NJ, Crary JF, Dickson DW, Folkerth RD, Keene CD et al (2021) The second NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 80:210–219. 10.1093/jnen/nlab001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, Abisambra JF, Abner EL, Alafuzoff I et al (2014) Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol 128:755–766. 10.1007/s00401-014-1349-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickson DW, Bergeron C, Chin SS, Duyckaerts C, Horoupian D, Ikeda K et al (2002) Office of Rare Diseases neuropathologic criteria for corticobasal degeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61:935–946. 10.1093/jnen/61.11.935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roemer SF, Grinberg LT, Crary JF, Seeley WW, McKee AC, Kovacs GG et al (2022) Rainwater Charitable Foundation criteria for the neuropathologic diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy. Acta Neuropathol 144:603–614. 10.1007/s00401-022-02479-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hauw JJ, Daniel SE, Dickson D, Horoupian DS, Jellinger K, Lantos PL, McKee A, Tabaton M, Litvan I (1994) Preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy). Neurology 44(11):2015–2019. 10.1212/wnl.44.11.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louis ED, Zheng W, Mao X, Shungu DC (2007) Blood harmane is correlated with cerebellar metabolism in essential tremor: a pilot study. Neurology 69:515–520. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266663.27398.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K (2006) Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 112:389–404. 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS, Nelson PT, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Hyman BT, National Institute on Aging, & Alzheimer’s Association (2012) National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 123(1):1–11. 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW et al (2012) National institute on aging-Alzheimer’s association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 123:1–11. 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT (2011) Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 1:a006189. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Louis ED, Faust PL, Vonsattel J-PG, Honig LS, Rajput A, Robinson CA et al (2007) Neuropathological changes in essential tremor: 33 cases compared with 21 controls. Brain 130:3297–3307. 10.1093/brain/awm266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Louis ED, Lee M, Babij R, Ma K, Cortés E, Vonsattel J-PG et al (2014) Reduced Purkinje cell dendritic arborization and loss of dendritic spines in essential tremor. Brain 137:3142–3148. 10.1093/brain/awu314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaquer-Alicea J, Diamond MI, Joachimiak LA (2021) Tau strains shape disease. Acta Neuropathol 142:57–71. 10.1007/s00401-021-02301-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woerman AL, Aoyagi A, Patel S, Kazmi SA, Lobach I, Grinberg LT et al (2016) Tau prions from Alzheimer’s disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy patients propagate in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:E8187–E8196. 10.1073/pnas.1616344113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Louis ED, Honig LS, Vonsattel JPG, Maraganore DM, Borden S, Moskowitz CB (2005) Essential tremor associated with focal nonnigral lewy bodies: a clinicopathologic study. Arch Neurol 62:1004–1007. 10.1001/archneur.62.6.1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Louis ED, Iglesias-Hernandez D, Hernandez NC, Flowers X, Kuo S-H, Vonsattel JPG et al (2022) Characterizing lewy pathology in 231 essential tremor brains from the essential tremor centralized brain repository. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 81:796–806. 10.1093/jnen/nlac068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Louis ED, Faust PL (2023) Prevalence of Lewy pathology in essential tremor is twice as high as expected: a plausible explanation for the enhanced risk for Parkinson disease seen in essential tremor cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 82:454–455. 10.1093/jnen/nlad021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benito-León J, Louis ED, Bermejo-Pareja F, Neurological Disorders in Central Spain Study Group (2009) Risk of incident Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism in essential tremor: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80:423–425. 10.1136/jnnp.2008.147223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frost B, Jacks RL, Diamond MI (2009) Propagation of tau misfolding from the outside to the inside of a cell. J Biol Chem 284:12845–12852. 10.1074/jbc.M808759200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holmes BB, Furman JL, Mahan TE, Yamasaki TR, Mirbaha H, Eades WC et al (2014) Proteopathic tau seeding predicts tauopathy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111:E4376–E4385. 10.1073/pnas.1411649111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benito-León J, Louis ED, Bermejo-Pareja F, Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) Study Group (2006) Population-based case-control study of cognitive function in essential tremor. Neurology 66:69–74. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192393.05850.ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benito-León J, Louis ED, Mitchell AJ, Bermejo-Pareja F (2011) Elderly-onset essential tremor and mild cognitive impairment: a population-based study (NEDICES). J Alzheimers Dis 23:727–735. 10.3233/JAD-2011-101572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghanem A, Berry DS, Burkes A, Grill N, Hall TM, Hart KA et al (2024) Prevalence of and annual conversion rates to mild cognitive impairment and dementia: prospective, longitudinal study of an essential tremor cohort. Ann Neurol. 10.1002/ana.26927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thawani SP, Schupf N, Louis ED (2009) Essential tremor is associated with dementia. Neurology 73:621–625. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b389f1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.LaCroix MS, Artikis E, Hitt BD, Beaver JD, Estill-Terpack S-J, Gleason K et al (2023) Tau seeding without tauopathy. J Biol Chem 300:105545. 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stopschinski BE, Del Tredici K, Estill-Terpack S-J, Ghebremedhin E, Yu FF, Braak H et al (2021) Anatomic survey of seeding in Alzheimer’s disease brains reveals unexpected patterns. Acta Neuropathol Commun 9:164. 10.1186/s40478-021-01255-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coughlin D, Pizzo D, Salmon D, Galasko D, Hiniker A (2021) Co-occurring PSP pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: a case series (3029). Neurology 96:3029. 10.1212/WNL.96.15_supplement.3029 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunach P, Vaquer-Alicea J, Smith MS, Hopewell R, Monistrol J, Moquin L et al (2023) Cryo-EM structure of Alzheimer’s disease tau filaments with PET ligand MK-6240. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2023.09.22.558671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marquie M, Normandin MD, Vanderburg CR, Costantino I, Bien EA, Rycyna LG et al (2015) Validating novel tau PET tracer [F-18]-AV-1451 (T807) on postmortem brain tissue. Ann Neurol 78:787–800. 10.1002/ana.24517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marquié M, Siao Tick Chong M, Antón-Fernández A, Verwer EE, Sáez-Calveras N, Meltzer AC et al (2017) [F-18]-AV-1451 binding correlates with postmortem neurofibrillary tangle Braak staging. Acta Neuropathol 134:619–628. 10.1007/s00401-017-1740-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Petersen GC, Roytman M, Chiang GC, Li Y, Gordon ML, Franceschi AM (2022) Overview of tau PET molecular imaging. Curr Opin Neurol 35:230–239. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000001035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Congdon EE, Ji C, Tetlow AM, Jiang Y, Sigurdsson EM (2023) Tau-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease: current status and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol 19:715–736. 10.1038/s41582-023-00883-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available without any restriction upon request to the authors or are already available in the main text and supplement.