SUMMARY

Efficient transformation systems are highly desirable for plant genetic research and biotechnology product development efforts. Tissue culture‐free transformation (TCFT) and minimal tissue culture transformation (MTCT) systems have great potential in addressing genotype‐dependency challenge, shortening transformation timeline, and improving operational efficiency by greatly reducing personnel and supply costs. The development of Arabidopsis floral dip transformation method almost 3 decades ago has greatly expedited plant genomic research. However, development of efficient TCFT or MTCT systems in non‐Brassica species had limited success until recently despite the demonstration of successful in planta transformation in many plant species. In the last few years, there have been some major advances in the development of such systems in several crops using novel approaches. This article will review these new advances and discuss potential areas for further development.

Keywords: tissue culture‐free system, high throughput, crop transformation, in planta regeneration, herbicide selection

Significance Statement

Efficient transformation systems are highly desirable for plant genetic research and biotechnology product development efforts. Tissue culture‐free transformation and minimal tissue culture transformation systems have great potential in addressing genotype‐dependency challenge, shortening transformation of timeline, and improving operational efficiency by greatly reducing personnel and supply costs. In the last few years, there have been some major advances in the development of such systems in several crops using novel approaches. This article will review these new advances and discuss potential areas for further development.

INTRODUCTION

Both conventional genetic modification (GM) and genome editing (GE) research efforts heavily rely on the use of efficient transformation systems. The ideal transformation system should be low cost, fast, high‐throughput, genotype‐flexible, and result in high‐quality heritable transgenic events with a high percentage of low copy intact inserts that express transgene well. For GE applications, it is highly desirable to have a transformation system that results in a high rate of heritable edits but free of transgene insert. Since the initial successes in demonstrating plant transformation with either Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated delivery or direct physical gene delivery including protoplast transfection and biolistics about 40 years ago, there have been numerous advances in developing transformation systems in different crops (Altpeter et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2022; Que et al., 2019; Su et al., 2023). Typically, these conventional transformation systems rely on lengthy tissue culture processes that may include explant preparation, gene delivery, callus induction, regeneration, selection, and rooting steps for recovery of transgenic events. Thus, they are often limited by low transformation efficiency, high genotype dependency, long timeline, and lower throughput (Chen et al., 2022; Mangena, 2022; Su et al., 2023) (Box 1).

Box 1. Bullet point summary.

Efficient genotype‐flexible tissue culture‐free transformation (TCFT) system is highly desirable for basic plant genetic research and commercial trait development.

In planta transformation systems have great potential in addressing genotype‐dependency issues and shortening transformation timeline.

Minimal tissue culture transformation (MTCT) systems apply different approaches including the use of different target tissues, regeneration methods, and selection systems

High‐throughput operation can be considered at different steps of transformation to achieve efficiency gain.

To address challenges associated with in vitro culture‐based transformation systems, various in planta transformation approaches that involve minimal or no tissue culture steps have been explored by various laboratories in different plant species (Bélanger et al., 2024; Kaur & Devi, 2019; Kojima et al., 2006). Since, in planta transformation involves directly transforming seeds, seedlings, cuttings, inflorescence, pollen, intact plants, or other plant tissues without the need for regeneration from detached explants through tissue culture, it is potentially an approach that can alleviate genotype‐dependence challenge, and thus greatly reduces transformation timeline and labor cost associated with in vitro culture techniques. The successful development of a highly efficient floral dip transformation method in Arabidopsis (Bechtold et al., 1993; Clough & Bent, 1998) has greatly advanced plant genomic research. It has also inspired many scientists to develop in planta transformation systems based on gene delivery to seeds, young shoot apexes, or inflorescence in many other plant species. However, except in a few species in planta transformation has been limited by low efficiency (Bélanger et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2022; Kaur & Devi, 2019).

In the last few years, there have been some major advances in the development of TCFT or MTCT systems in several crops using novel approaches (Cao et al., 2023; Mei et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023; Zhong et al., 2024) and in the development of high‐throughput transformation systems for explant preparation and herbicide selection (Valentine et al., 2024; Walker et al., 2023; Ye et al., 2022; Zhong et al., 2024). Also, several classes of developmental regulators and morphogenic factors have been discovered and used to broaden genotype and explant tissue flexibility, improve transformation efficiency, and shorten transformation timeline (Lian et al., 2022; Lowe et al., 2016; Maher et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022, 2023; Yu et al., 2024). This article will review these new progresses and discuss potential areas for further development.

APPROACHES FOR TISSUE CULTURE‐FREE TRANSFORMATION

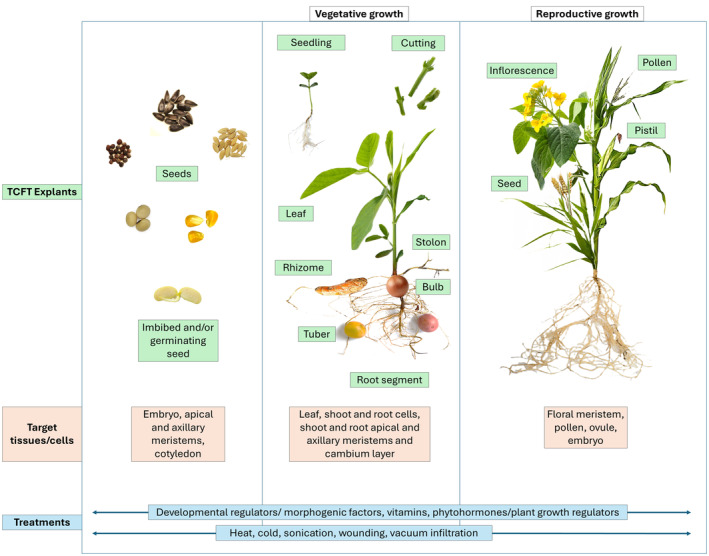

Transformation systems requiring minimal or no tissue culture manipulation allow direct introduction of foreign genes into plant cells or tissues without the need for labor‐intensive in vitro tissue culture steps. Incidentally, most of these TCFT or MTCT systems use the in planta transformation approach. In this review, if the transformation target tissue is part of an intact plant and a stable transgenic event is recovered from such an intact plant, the transformation method is classified as in planta transformation. These TCFT or MTCT methods are advantageous as they bypass the laborious and time‐consuming in vitro culture process that utilizes specialized tissue culture skillsets, dedicated laboratory space, expensive instruments, chemicals, and other consumables. In addition, these methods reduce the risk of off‐type plants resulted from the somaclonal variations due to lengthy in vitro culture and may provide increased event quality and transformation efficiency. Since many plant tissues can potentially serve as transformation targets (Figure 1), we will discuss recent progresses in different TCFT and MTCT methods based on target tissues used for gene delivery and regeneration of transgenic events.

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of commonly used explant materials and various tissues and cells targeted for gene delivery and regeneration in TCFT/MTCT systems. Various developmental regulators or morphogenic factors and target tissue treatments are used to enhance transformation efficiency.

Transformation with germinating seeds or explants from seeds

Imbibed and germinating seeds were used as transformation targets in the first successful attempt of tissue culture‐free Agrobacterium‐mediated stable transformation (Feldmann & Marks, 1987). Other plants including cotton, Medicago truncatula, peanut, safflower, sunflower, and watermelon have also been successfully transformed using explants derived from imbibed seeds with minimal in vitro manipulation or whole plant transformation (see review by Kaur & Devi, 2019). Exposed shoot apical meristems of imbibed mature embryos after removing coleoptiles and leaf primordia were used as targets for particle bombardment and chimeric transgenic plants were generated from both elite and elite wheat varieties in a very short timeline; some of the transgenic events obtained via this in planta transformation method were heritable (Hamada et al., 2017). Recently, we also developed a high‐throughput genotype‐independent fast transformation (GiFT) system in soybean using imbibed seed explants in combination with in planta regeneration of transgenic shoots from axillary meristems and herbicide selection to eliminate chimeras (Zhong et al., 2024).

Young seedling and whole plant transformation

Infiltration of young seedlings and developing plants with Agrobacterium suspensions has been attempted for developing in planta transformation method in many plant species, e.g., Trieu et al. (2000) described an efficient method to transform M. truncatula via infiltration of seedlings with Agrobacterium. However, the frequency of heritable transgenic events is usually very low for most plant species since most of the transformed cells are somatic and do not give rise to heritable transgenic events. Wounding of the apical and axillary meristematic regions has been used to improve in planta transformation efficiency (Kojima et al., 2006). Even so, the transformation efficiency is still limited since usually little additional treatment such as selection is applied to the infiltrated plants to allow preferential proliferation and growth of transgenic meristems. A major recent progress in the whole plant transformation was the demonstration that vegetatively propagated cuttings and soil‐grown whole plants injected with Agrobacterium strain carrying vectors expressing developmental regulators (DRs) including Wus2, ipt and STM, and CRISPR‐Cas9 editing machinery directly induced de novo meristem and subsequent shoot formation in several plant species including tobacco, tomato, grape, and potato (Maher et al., 2020). Similar success of in planta transformation with DR‐induced de novo shoot formation was also shown in snapdragon, tomato, and Brassica cabbage (Lian et al., 2022). Lian et al. (2022) further tested several alternative DRs including PLETHORA (PLT5), WOUND INDUCED DEDIFFERENTIATION 1 (WIND1), ENHANCED SHOOT REGENERATION (ESR1), WUSHEL (WUS), and a fusion of WUS and BABY‐BOOM (WUS‐P2A‐BBM) for in planta transformation and demonstrated manipulation of PLT5 expression was one of the most effective DRs for achieving high in planta transformation efficiency in snapdragon and tomato.

Shoot and stem cutting transformation

Recently, Mei et al. (2024) describe an efficient, easy‐to‐use A. tumefaciens‐mediated transformation system called regenerative activity‐dependent in planta injection delivery (RAPID) in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), potato (Solanum tuberosum), and bayhops (Ipomoea pes‐caprae). This RAPID is based on the active in planta regeneration capacity of excised shoot cuttings in these plants, and A. tumefaciens is delivered to plant meristems via injection to induce transgenic nascent tissues. Using this method, stable transgenic plants were obtained by subsequent vegetative propagation of the positive nascent tissues. The method is simple to use, does not require tissue culture, and has a high transformation rate and short duration. The study also tested several Agrobacterium strains and found that the disarmed strain AGL1 resulted in the highest transformation efficiency in sweet potato using the RAPID method.

Agrobacterium rhizogenes strains carrying Ri plasmid are used routinely to generate adventitious transgenic roots from infected seed explants and shoots for gene function testing in dicot plants such as soybean, sunflower, and Medicago (Kereszt et al., 2007). If seed explants or stem sections are used, A. rhizogenes can elicit the formation of a composite plant comprising a transgenic hairy root system attached to the nontransformed shoots and leaves. Production of hairy roots using A. rhizogenes is fast, highly efficient, and genotype independent. However, usually, no heritable transgenic plants can be recovered using such hairy root systems. Recently, a simple and highly efficient one‐step A. rhizogenes‐mediated transformation method was established for sweet potato by inoculating shoot cuttings with A. rhizogenes and then planting the cuttings in soil to develop tubers that geminate to form transgenic shoots (Zhang et al., 2023). Similarly, Cao et al. (2023) described a simple cut‐dip‐budding (CDB) delivery system, which uses A. rhizogenes to inoculate apical stem cuttings, generating transformed roots and tubers that produce transformed buds without the need for tissue culture. The CDB method was tested in several other plant species that can form buds and shoots from root cuttings and obtained stable transgenic plants in two herbaceous plants (Taraxacum kok‐saghyz and Coronilla varia) and three woody plant species (Ailanthus altissima, Aralia elata, and Clerodendrum chinense). Most of these plants were recalcitrant to transformation, but the CDB method enabled their efficient transformation and gene editing using a simple explant dipping protocol under non‐sterile conditions.

Root, rhizome, and tuber transformation

It was shown many years ago that Arabidopsis root explants could be efficiently transformed using A. tumefaciens‐mediated transformation for generating transgenic plants using in vitro culture (Valvekens et al., 1988). Other plants such as eggplant and M. truncatula were also successfully transformed with root as explants (Crane et al., 2006; Franklin & Lakshmi Sita, 2003). However, the use of root as in planta transformation target tissue is less explored for TCFT probably due to its limited accessibility and inconvenience for manipulation, since it is usually buried in soil. Recently, it was shown that the roots of Russian dandelion (Taraxacum kok‐saghyz), a plant with root‐sucking capability, can be transformed efficiently with A. rhizogenes, and transgenic plants were generated from transgenic root segments through budding without the use of tissue culture (Cao et al., 2023). Interestingly, the utility of A. rhizogenes for inducing transgenic hairy roots and recovery of stable transgenic plants from induced transgenic hairy roots have also been extended to citrus fruit trees (Ramasamy et al., 2023). Thus, A. rhizogenes might be a very useful tool for genetic engineering of tree species that are typically recalcitrant to transformation. In another study, potato tubers were also used as targets for TCFT, and transgenic and edited plants were successfully generated from the tuber by injecting Agrobacterium strain carrying the mScarlet and RUBY reporter genes into the skin of the tuber around the buds (Mei et al., 2024). In this study, Agrobacterium cells were co‐injected with exogenous growth regulators 6‐BA (6‐benzyladenine) and NAA (naphthyl acetic acid) to induce sprouting without causing potential undesirable phenotypes associated with the use of A. rhizogenes. Transgenic nascent shoots emerged from the tubers after 2–3 weeks and exhibited strong mScarlet and RUBY phenotypes in the leaves and stems. Regenerated nascent potato shoots also showed efficient editing of PDS genes (Mei et al., 2024). Recently, it was shown that meristematic regions of Panax notoginseng rhizome and Lilium regale bulb could be injected and transgenic plants regenerated from injected tissues directly (Deng et al., 2024).

For plants that can be propagated through stem or root cutting and suckering, the tissue culture‐free CDB‐like delivery method has great potential despite the need to remove A. rhizogenes oncogenes associated with hairy root induction from transgenic plants (Cao et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023). Conceivably, the CDB‐like method can be further improved by incorporating an inducible system for removing oncogene insert (Cho et al., 2022; Hoerster et al., 2020). In contrast, the system of RAPID (Mei et al., 2024) and similar methods (Deng et al., 2024) were demonstrated recovery of transgenic and/or edited plants using injection of stem segments, rhizome, or bulb meristems with disarmed A. tumefaciens strains. Thus, the RAPID‐type methods overcome the disadvantages of CDB method in having to use A. rhizogenes, but may result in lower TCFT efficiency.

Floral tissue transformation

The floral dip transformation method was first described for Arabidopsis by Bechtold et al. (1993) and later optimized by Clough and Bent (1998). It involves dipping the flowering inflorescences into Agrobacterium suspension carrying the desired gene construct. The Agrobacterium cells directly enter the ovule and deliver the transgene into the plant's reproductive cells, resulting in the production of transgenic seeds. This technique revolutionized the way the model plant Arabidopsis could be genetically transformed to generate transgenic events quickly with much higher efficiency. Besides Arabidopsis, a growing number of plant species have been transformed using the floral dip transformation method, including green foxtail (Setaria viridis), M. truncatula, Brassica napus, Indian mustard (Brassica juncea), Camelina sativa, and tomato (see reviews by Kaur & Devi, 2019 and Bélanger et al., 2024). However, progress is limited in many economically important crops and high efficiency is still limited to model plant species that have relatively small stature with many small flowers. A method for transferring foreign DNA into newly pollinated flowers, known as the pollen‐tube pathway, was first reported in cotton by Zhou et al. (1983). Similar method was later reported in rice using florets; the pollen tube method is fast to get transgenic seeds (Wang et al., 2013); however, its use is limited due to low efficiency and consistency. Recently, it was shown that efficient production of transgenic peanut plants was achieved by pollen tube transformation mediated by A. tumefaciens using simple injection into pollen tube pathway (Zhou et al., 2023). Yang et al. (2017) also reported a method of transforming maize by delivering genes to pollen through sonication treatment and showed reporter gene expression in pollen tubes, embryos, and stable transgenic insertion. The study showed that the aeration at 4°C treatment of pollen grains in sucrose prior to sonication significantly improved the pollen viability, leading to improved kernel set and transformation efficiency.

ACHIEVING HIGH IN PLANTA TRANSFORMATION EFFICIENCY AND EVENT QUALITY

To establish an efficient transformation system, that is, genotype flexible requires minimal tissue culture and results in high event quality, these important factors must be considered: (1) Target tissue that is highly receptive to DNA delivery has efficient regeneration competency across different genotypes and gives rise to meristematic tissue or germline cells. (2) Efficient gene delivery to the target cells that can regenerate into stable transgenic plants. (3) Effective selection condition for recovery of transformants with high rate of transgene inheritance. (4) Transgene vector design or use of Agrobacterium strains that generate high rate of events with heritable backbone‐free single copy intact transgene insert.

Competency for gene delivery and regeneration

High competency of target tissue for gene delivery and regeneration is the prerequisite for establishing any efficient transformation process, no matter in vitro or in planta. Selecting a transformation target explant is also crucial in achieving high genotype flexibility. Target explants' competency for gene delivery and regeneration are plant species‐ and developmental stage specific. The morphogenetic plasticity and transformable competency of shoot meristems in major cereal and dicot crops have been extensively demonstrated in in vitro tissue culture studies. Shoot apical meristem is a common target for in planta transformation (Chen et al., 2020; Ganguly et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2018; Kesiraju et al., 2021). However, the shoot apical meristem is comprised of densely packed cells, with only a few undifferentiated stem cells distributed across different zones underneath the L1 cell layers (Agata, 2021). Consequently, delivering genes to the meristematic cells in the inner cell layers poses a technical challenge, leading to inefficiency in heritable transformation, especially when no selection is applied after gene delivery to enhance proliferation of transformed cells. As a result, large‐scale screening must be undertaken in subsequent generations to identify stable and heritable transformation lines. The inherent inefficiency and the additional efforts required for screening progeny populations render this approach less suitable for large‐scale transformation. Seedling or stem axillary meristem is another target commonly used for transformation. The totipotency of axillary meristematic tissues to rapidly regenerate new shoots through organogenesis poses an opportunity for developing high‐throughput and genotype‐flexible transformation methods with minimum tissue culture operation. For example, the cotyledonary areas of germinated seeds have been used for high efficiency transformation in peanut and soybean (Karthik et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2024).

Recent progress in incorporating developmental regulators (DRs) into transformation methods provides a new approach to improve transformation competency of target tissues. Incorporating DRs like WUS and STM enables meristem induction from somatic cells (Lowe et al., 2016). Overexpressing DRs like Baby Boom (BBM), Wuschel2 (Wus2), TaLAX1, TaWOX5, and PLT5 enhanced regeneration and transformation frequency in dicots and monocots (Hoerster et al., 2020; Lian et al., 2022; Lowe et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2024). Co‐delivering DRs with gene‐editing reagents via Agrobacterium injections into dicots generated meristems in somatic tissues, enabling de novo shoot formation and tissue culture‐free gene‐editing (Maher et al., 2020). This DR‐mediated approach overcomes regeneration barriers, offering the potential for enabling efficient in planta transformation across diverse species, e.g. to improve in planta transformation of woody species, such as orange, Chinese tea, longan, and passion fruit (Rizwan et al., 2021). Another interesting development is the use of CRISPR‐COMBO system to simultaneously activate expression of DRs for improving transformation by activating morphogenic genes and editing of target genes in rice and poplar (Pan et al., 2022). The authors also used CRISPR‐COMBO to shorten the plant life cycle and reduce the efforts in screening of transgene‐free genome‐edited plants by activation of a florigen gene in Arabidopsis (Pan et al., 2022).

Gene delivery

An efficient transgene delivery method is considered one of the most challenging factors in developing TCFT and MTCT systems. Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation method is still the most used for gene delivery due to its low cost, simplicity, and high efficiency. However, Agrobacterium‐mediated delivery method can be limited by the hypersensitive response caused by plant's defense response in comparison with direct DNA delivery. To achieve efficient gene delivery to the target cells MTCT and TCFT methods often use one or more treatments that were found to enhance gene delivery and improve recovery of transgenic materials in conventional in vitro transformation methods (Karthik et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2024). These treatments typically include more virulent Agrobacterium strains and helper plasmids, wounding, sonication, vacuum infiltration, pressure, centrifugation force, surfactant, acetosyringone, hormone, darkness, and more recently, co‐expression of developmental regulators or morphogenetic factors (Altpeter et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2022; Que et al., 2019; Su et al., 2023). The vacuum infiltration technique allowed for the efficient introduction of foreign genes directly into the plant tissues, bypassing the need for tissue culture and regeneration steps, which can be time consuming and prone to somaclonal variations (e.g., Clough & Bent, 1998). The vacuum infiltration technique has facilitated numerous transient and stable transformation studies. Sonication‐assisted Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation (SAAT) method combines the use of Agrobacterium with ultrasound treatment (sonication), it is also widely used to enhance the delivery of the transgene into plant cells (Trick & Finer, 1997). The sonication step helps to create transient pores in the plant cell walls, allowing Agrobacterium to penetrate and transfer the genetic material more efficiently. The SAAT method can be applied to improve the TCFT and MTCT efficiency in various plant species, e.g., in our recently developed soybean GiFT method (Zhong et al., 2024).

It should be noted that direct delivery methods including particle bombardment (biolistics) and whisker‐mediated wounding have been used for transformation and genome editing for many years (Que et al., 2019). Biolistic delivery is especially useful for delivering ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex or RNA molecules for transgene‐free genome editing. Also, biolistic delivery does not have the complication of host range and host defense response associated with Agrobacterium‐mediated delivery methods. In planta particle bombardment (iPB) of meristematic tissues has been successfully used to generate transgenic plants and edited materials in barley and wheat with relatively short timeline (Hamada et al., 2017; Tezuka et al., 2024). One of the major limitations of the biolistic method is the number of target tissues that can be bombed. Improvements in the biolistic device to increase capacity should facilitate its broader use in tissue‐culture applications. An example of such improvement is the recent development of a double‐barrel device and associated cell counting software to reduce errors and increases throughput (Miller et al., 2021).

Transgenic event selection

A proper and effective selection method is another critical factor that impacts transformation efficiency and event quality. Organogenesis often originated from a group of cells forming new shoot or root meristems during the regeneration process (Long et al., 2022). Selection is the most critical strategy to mitigate chimerism. If no adequate selection pressure is applied during shoot regeneration and development, most of the regenerated shoots are chimeric, posing significant challenges on event quality and throughput for TCFT and MTCT systems. Without effective selection, both transgenic or non‐transgenic meristematic tissue will proliferate and regenerate, forming transgenic, non‐transgenic, and chimeric organs. Since the number of transgenic meristematic cells are only a small fraction of total meristematic cell population and generation of shoots in TCFT and MTCT systems relies on organogenesis process, without selection most of the regenerated tissues will be non‐transgenic or chimeric, requiring generation and screening of a large number of plants, thus resulting in low efficiency in recovering heritable transgenic events. On the other hand, unlike the in vitro tissue culture‐based transformation process, the organogenesis in TCFT and MTCT systems also heavily relies on the continuous growth of mother explants, which will provide a nurturing base for continuous development of transgenic cells and rapid growth of regenerated organs. Therefore, a delicate balance between proliferation and inhibition in transgenic versus non‐transgenic cells becomes essential requiring careful application and timing of selection, including the use of sublethal or nonlethal selection levels. Herbicide provides a cost effective and efficient way of selecting transgenic plants in planta. For example, the meristem tissue of germinated watermelon seeds was wounded and inoculated with an Agrobacterium suspension. The explants were then transferred to a selection medium, and transgenic shoots were regenerated with 17% transformation efficiency (Vasudevan et al., 2021). Very similar methods have produced transgenic plants in peanuts, snake gourd, okra, bitter gourd, sugarcane, and other plant species. These methods are simple and reliable. However, a large portion of these protocols, including selection, is carried out on solid media under sterile tissue culture conditions in the lab, which limits its throughput (Karthik et al., 2018). The efficiency could be significantly enhanced by applying selection to soil‐grown plants (Guo et al., 2018). We also recently demonstrated achieving robust selection and high‐efficiency production of high‐quality soybean events within planta herbicide selection (Zhong et al., 2024). In this soybean GiFT method, 1‐week nonlethal liquid preselection was implemented to promote the organogenesis from transgenic meristematic cells over the growth of non‐transformed cells and the formation of chimeric shoot primordia before the process of soil‐based in planta selection. This step was found to be essential for high transformation frequency and high‐quality event production. Similar selection strategy can probably be adopted to improve efficiency of different TCFT methods including the previously described CDB and RAPID methods. For direct shoot formation from soil‐grown plants, such as the approach described by Maher et al. (2020), it is possible that the application of nonlethal selection on the Agrobacterium inoculation region can significantly improve the recovery of quality transgenic events.

Event quality and inheritance

It should be noted that not all herbicide markers are the same. EPSPS, ALS, PAT, and PPO are some of the commonly used herbicide selectable marker genes. It is also important to understand the mode of action of the herbicide compound. Each of the selectable markers has one or more corresponding herbicides that may behave quite differently in terms of potency and mobility in different plant species. For example, there are at least five classes of herbicides that bind to different parts of the ALS enzyme (Shimizu et al., 2002). We have used both bensulfuron‐methyl (Class: sulfonylurea herbicides) and imazapyr (Class: imidazolinone herbicides) for in planta selection (Zhong et al., 2024). To reduce chimera rate in TCFT methods, it is critical to use a systemic or translocated herbicide such as glyphosate for EPSPS and bensulfuron‐methyl for ALS marker. The use of contact or nonsystemic herbicide such as glufosinate for PAT or BAR marker genes and butafenacil for PPO marker gene is likely to result in higher percentage of periclinal chimeric events where transgenes are not inherited to the next generation.

Last, it is important to consider vector design that generates high rate of events with heritable single copy backbone‐free intact transgene insert, e.g., by including a barnase expression cassette in the backbone to reduce backbone‐containing events that may be present in a higher percentage in TCFT method where a selection is not used (Hanson et al., 1999). For developing high‐efficiency TCFT systems, it is also critical to use an Agrobacterium strain with a supervirulent helper plasmid that results in high delivery efficiency for the crop. The substantial progress on improving Agrobacterium–plant interaction for more effective and broader spectrum infection has been reviewed and summarized (Chen et al., 2022; de Saeger et al., 2021). These accomplishments surely will further exploit the extensive application of Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation method.

APPROACHES TO ACHIEVE HIGH‐THROUGHPUT TRANSFORMATION

Over the past few decades, many MTCT or TCFT in planta protocols have emerged as simpler alternatives to laborious and time‐consuming in vitro techniques. However, these in planta methods have not been widely adopted as the primary transformation approach for commercially important crops due to their overall low transformation efficiency and throughput compared to in vitro techniques. To establish an efficient high‐throughput TCFT or MTCT system, the following factors should be considered.

Availability of abundant and cheap target tissues

Explant availability and easy preparation are significant factors impacting transformation throughput. As discussed in the previous section, various recipient materials have been used as explants for TCFT or MTCT systems. Among these, seeds, embryos, and leaves are the most abundant materials. Seeds or the resulting embryos are the most often used starting materials for both in vitro and in planta due to their year‐round availability, small size, and consistency, thus allowing large‐scale experiments and high throughput. In addition, seeds and embryos have vigorous growing axillary or apical meristems that can be effectively infected by Agrobacterium for efficient gene delivery (Chen et. al, 2014; Cho et al., 2022; Valentine et al., 2024; Zhong et al., 2024). Floral tissues are another commonly used recipient material for in planta transformation in certain species. Although pollen is abundant and artificial pollination is straightforward for plant species, such as maize, efficient gene delivery to pollen has not been reported so far. Another factor to consider is the number of explants producing stable transformants that can be processed per time unit. From this perspective, leaf explants, protoplasts, and somatic embryos are very attractive targets, since it is relatively easy to produce a large number of these target explants. For some species like tobacco and poplar, leaf explants have excellent totipotency and can produce transgenic plants in a short time. Protoplast systems can produce millions of single cells in a single experiment for transfection with DNA, RNA, or RNP complex for GM and GE purposes (Rigoulot et al., 2023; Walker et al., 2023). However, for most crops, protoplast systems are still limited by low microcalli conversion efficiency, low efficiency of microcalli regeneration, and somaclonal variation of regenerated plants.

Use of mechanized or automated processes

Mechanization and automation can be used in different steps of transformation. Automation has been explored for many years to reduce the labor cost of tissue culture in plant propagation with stem or nodal cuttings, meristem micropropagation, and somatic embryogenesis (reviewed in Vasil, 1994). These existing automation technologies can probably be applied to transgenic event‐generation processes with some modifications. Use of somatic embryos (SE) has great potential, since unlimited number of SEs can be generated from one original seed embryo and SE cultures can be cryopreserved for many years. The automation of SE platforms has been reviewed extensively by Egertsdotter et al. (2019). Protoplast systems can produce millions of target cells at one time. Protoplasts can be efficiently transfected by DNA, RNA, or RNP complex using an automated process (Rigoulot et al., 2023). Partially automated industrial‐scale genome editing system using protoplast was reported for generation of edited high oleic oil and pod shattering tolerance traits in canola (Walker et al., 2023). High‐throughput systems for industrial‐scale preparation of transformation explants were reported for embryo extraction in soy, cotton, wheat, and maize with a roller machine (Chen et al., 2014; Martinell et al., 2002; Valentine et al., 2024; Ye et al., 2022). In these methods, extracted embryos can be used directly or stored for extended time before use for transformation, thus providing flexibility in large‐scale transformation operations (Chen et al., 2014; Valentine et al., 2024; Ye et al., 2022). It should be noted that automation has already been used routinely in many labs for culture media preparation, DNA isolation, herbicide spray, and event molecular analysis besides the core tissue culture processes. For in planta transformation, event selection is critical to reduce the occurrence of chimeras. We have used automatic herbicide spray for effective selection of soil‐grown composite soybean plants, enabling a high‐throughput GiFT process in soybean (Zhong et al., 2024).

Efficient use of space and short timeline

These are two other factors to consider for high‐throughput transformation operations. Procedures that produce more transgenic events per unit of lab or greenhouse space can greatly reduce transgenic event generation costs. Therefore, smaller size of starting explants, cultures, and transgenic plants in combination with a short event generation turnaround time would lead to high‐efficiency operation. Arabidopsis floral dipping is a good example of an efficient transformation system with a high number of transgenic events per space unit (Clough & Bent, 1998). Our recently developed high‐throughput soybean GiFT system can generate thousands of transgenic events in less than 2 months, and they can be directly used for performance evaluation of resistance gene expression vectors for Asian soybean rust disease (Zhong et al., 2024). In the GiFT method, the Agrobacterium‐infected explants undergo preselection for a few days and then are transplanted directly into soil, where an automated spraying system applies herbicide for 3 weeks to facilitate further selection and regeneration of transgenic events with minimal effort. This method is very efficient in utilizing growth chamber space, capable of high‐density planting with 150 preselected explants in a standard soil flat, and 6000 explants in a 400 square feet chamber for one 4‐week in planta selection and regeneration cycle. A single small growth chamber can annually generate more than 20 000 transgenic soybean events.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Fast, efficient, and genotype‐flexible transformation systems are critical to translate knowledge gained from genetic discovery and biotechnological innovation into new crop varieties through conventional transgenic (GM) or the newly developed GE approach. Recent developments in high‐throughput conventional in vitro tissue culture‐based techniques and in planta methods will greatly accelerate agricultural biotechnology research and product development efforts, especially genome‐edited traits for testing and deployment in wide genetic backgrounds. Table 1 summarizes some of the recent progresses in TCFT or MTCT systems. Apparently, the establishment of such TCFT or MTCT systems still highly depends on the biology of the target plant species. Therefore, the existing knowledge on a crop's in vitro transformation is very useful since it can be applied directly to the development of TCFT systems. Some of major factors that impact tissue culture‐free systems such as in planta regeneration and selection have not been explored extensively. For example, in planta regeneration can be greatly enhanced by overexpressing developmental regulators or morphogenetic factors such as BBM, WOX, WUS, PLT5, WIND1, GRF‐GIF, or their homologous genes (Debernardi et al., 2020; Lian et al., 2022; Maher et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2024) or activation of endogenous morphogenic factors and developmental regulators (Pan et al., 2022). Incorporation of in planta selection with systemic herbicidal agent should greatly reduce the occurrence of chimera and improve event quality by eliminating events with silenced multicopy transgenes, especially for recovering events from organogenesis (Zhong et al., 2024). Further incorporation of inducible or developmentally regulated excision of developmental regulator gene cassette after generation of transgenic shoots should further reduce plant off‐types (Cho et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023).

Table 1.

Recently developed TCFT and MTCT methods for GM and GE applications

| Method | Delivery target | Demonstrated species | Advantage | Potential improvement | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GiFT (Genotype‐independent fast transformation) | Seed explants | Soybean |

High regeneration potential Genotype flexible Low chimera rate Scalable/high throughput |

Apply to other crop species Test non‐seed explants |

Zhong et al. (2024) |

| CDB (cut‐dip‐budding) | Stem or root cutting |

Sweet potato Ailanthus altissima Aralia elata Clerodendrum chinense Coronilla varia, etc. |

High transformation efficiency via hairy‐root formation Genotype flexible Applicable to multiple tissues |

Use disarmed Agrobacterium strain Use excision system to remove integrated oncogenes |

Cao et al. (2023) Zhang et al. (2023) Lu et al. (2024) |

| RAPID (Regenerative Activity‐dependent in planta injection delivery) |

Stem segment Tuber cutting Rhizome Bulb |

Sweet potato Potato Bay hops Panax notoginseng Lilium regale |

Genotype flexible May be applicable to different explants Short time to transgenic plants |

Use herbicide selection Reduce chimeric issue |

Mei et al. (2024) Deng et al. (2024) |

| Developmental regulator (DR)‐induced de novo shoot formation |

Young seedling Stem Leaf |

Tobacco, tomato, grape Potato, snapdragon Brassica cabbage |

High regeneration potential Genotype flexible Scalable/high throughput |

Identify DR applicable to broad spectrum of plant species Reduce chimeric issue Remove DR with an excision system |

Maher et al. (2020) Lian et al. (2022) |

| Hi‐Edit (Haploid Induction Editing) | Zygote |

Maize Arabidopsis thaliana Wheat |

Genotype flexible Only need to transform the inducer line Hi‐Edit lines are homozygous |

Develop an efficient haploid induction system in target crops Improve editing and haploid doubling efficiency |

Kelliher et al. (2019) |

| Biolistic delivery |

Embryos Meristems Young seedling |

Wheat Barley |

Fast timeline Genotype flexible RNP/transgene‐free editing |

Increase efficiency Reduce chimera and improve transmission rate |

Hamada et al., 2017 Tezuka et al., 2024 |

| Nanoparticle delivery |

Seedling, leaf Inflorescence Embryo, pollen |

Arugula, watercress Tobacco, spinach Cotton, maize |

Genotype flexible Transgene‐free genome editing |

Delivery to meristematic cells Stable and heritable transformation or edits |

Lv et al. (2020) |

| Virus‐based gene delivery |

Seedling Leaf, stem Inflorescence Embryos |

Nicotiana benthamiana Wheat |

Transgene‐free genome editing Delivery to meristematic cells with mobile RNA High‐efficiency delivery |

Larger cargo size Genotype limitation due to virus host range Stable transgene integration and inheritance |

Ellison et al. (2020) Ma et al. (2020) Li et al. (2021) |

| Grafting | Scion |

Arabidopsis thaliana Brassica rapa |

Transgene‐free genome editing Genotype flexible |

Many plants cannot be grafted easily, especially monocots Editing efficiency in other crops |

Yang et al. (2023) |

It should be further noted that there have been many attempts to develop simple gene delivery technologies that are suitable for genome editing purposes where transgene integration is not desirable or needed, e.g., through direct DNA transfer using nanoparticles (Lv et al., 2020) or viral vector‐mediated gene delivery, which is simple and results in high‐efficiency gene expression (e.g. Ellison et al., 2020; Li et al, 2021; Ma et al., 2020; Mahmood et al., 2023). These new gene delivery systems are particularly attractive for genome editing purposes, since they bypass sophisticated tissue culture process and integration of editing machinery, and thus may qualify as transgene‐free techniques by the regulatory agencies. However, both the nanoparticle and viral vector delivery methods are still limited by payload capacity or recovery of stable plants with heritable edits. Encouragingly, recent development of a grafting‐based method may address the payload and heritable editing issue (Yang et al., 2023). Combination of viral vector, mobile RNA, and grafting should enable high‐efficiency generation of transgene‐free heritable edits (Ellison et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2023). We have also developed an alternative minimal tissue culture technology for carrying out genome editing in broad germplasms via haploid induction (Hi‐Edit) in which CRISPR‐Cas editing machinery is delivered through simple crossing but eliminated through the subsequent haploid induction process (Kelliher et al., 2019). The breakthrough in current or emerging delivery systems will have a significant impact on the application of transformation technology for crop improvement (Box 2).

Box 2. Open questions.

Can efficient TCFT/MTCT methods be developed in important monocot field crops like corn, rice, and wheat with the help of developmental regulators?

Is there a universal developmental regulator that can be used for promoting in planta regeneration for both monocot and dicot plant species?

Is it possible to develop a broad host range viral vector delivery system expressing mobile editing machineries for efficient heritable genome editing of major monocot and dicot crop species?

How to regenerate plants efficiently from transformed protoplasts with minimal tissue culture?

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

HZ, SE, CL, SD, WL, and QQ wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest associated with this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our Syngenta Seeds Research plant transformation colleagues for their helpful discussion and suggestions. Leadership support from Drs. Gusui Wu, Ian Jepson, and Mikyong Lee in the writing of this manuscript is greatly appreciated.

Contributor Information

Heng Zhong, Email: heng.zhong@syngenta.com.

Qiudeng Que, Email: qiudeng.que@synegnta.com.

REFERENCES

- Agata, B. (2021) Does shoot apical meristem function as the germline in safeguarding against excess of mutations? Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 707740. Available from: 10.3389/fpls.2021.707740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altpeter, F. , Springer, N.M. , Bartley, L.E. , Blechl, A.E. , Brutnell, T.P. , Citovsky, V. et al. (2016) Advancing crop transformation in the era of genome editing. Plant Cell, 28, 1510–1520. Available from: 10.1105/tpc.16.00196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold, N. , Ellis, J. & Pelletier, G. (1993) In planta Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer by infiltration of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie Des Sciences Serie III Sciences de la Vie, 316, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger, J.G. , Copley, T.R. , Hoyos‐Villegas, V. , Charron, J.B. & O'Donoughue, L. (2024) A comprehensive review of in planta stable transformation strategies. Plant Methods, 20, 79. Available from: 10.1186/s13007-024-01200-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X. , Xie, H. , Song, M. , Lu, J. , Ma, P. , Huang, B. et al. (2023) Cut‐dip‐budding delivery system enables genetic modifications in plants without tissue culture. Innovations, 4, 100345. Available from: 10.1016/j.xinn.2022.100345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. , Lange, A. , Vaghchhipawala, Z. , Ye, X. & Saltarikos, A. (2020) Direct germline transformation of cotton meristem explants with no selection. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 575283. Available from: 10.3389/fpls.2020.575283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. , Rivlin, A. , Lange, A. , Ye, X. , Vaghchhipawala, Z. , Eisinger, E. et al. (2014) High throughput Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated germline transformation of mechanically isolated meristem explants of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Plant Cell Reports, 33, 153–164. Available from: 10.1007/s00299-013-1519-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. , Debernardi, J.M. , Dubcovsky, J. & Gallavotti, A. (2022) Recent advances in crop transformation technologies. Nature Plants, 8, 1343–1351. Available from: 10.1038/s41477-022-01295-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.J. , Moy, Y. , Rudnick, N.A. , Klein, T.M. , Yin, J. , Bolar, J. et al. (2022) Development of an efficient marker‐free soybean transformation method using the novel bacterium Ochrobactrum haywardense H1. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 20, 977–990. Available from: 10.1111/pbi.13777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J. & Bent, A.F. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Journal, 16, 735–743. Available from: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane, C. , Dixon, R.A. & Wang, Z.Y. (2006) Medicago truncatula transformation using root explants. In: Wang, K. (Ed.) Agrobacterium protocols. Methods in molecular biology, Vol. 343. New York, NY: Humana Press, pp. 137–142. Available from: 10.1385/1-59745-130-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Saeger, J. , Park, J. , Chung, H.S. , Hernalsteens, J.P. , van Lijsebettens, M. , Inzé, D. et al. (2021) Agrobacterium strains and strain improvement: present and outlook. Biotechnology Advances, 53, 107677. Available from: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debernardi, J.M. , Tricoli, D.M. , Ercoli, M.F. , Hayta, S. , Ronald, P. , Palatnik, J.E. et al. (2020) A GRF‐GIF chimeric protein improves the regeneration efficiency of transgenic plants. Nature Biotechnology, 38, 1274–1279. Available from: 10.1038/s41587-020-0703-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J. , Li, W. , Li, X. , Liu, D. & Liu, G. (2024) A fast, efficient, and tissue‐culture‐independent genetic transformation method for Panax notoginseng and Lilium regale . Plants, 13, 2509. Available from: 10.3390/plants13172509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertsdotter, U. , Ahmad, I. & Clapham, D. (2019) Automation and scale up of somatic embryogenesis for commercial plant production, with emphasis on conifers. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 109. Available from: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, E.E. , Nagalakshmi, U. , Gamo, M.E. , Huang, P. , Dinesh‐Kumar, S. & Voytas, D.F. (2020) Multiplexed heritable gene editing using RNA viruses and mobile single guide RNAs. Nature Plants, 6, 620–624. Available from: 10.1038/s41477-020-0670-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann, K.A. & Marks, D.M. (1987) Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of germinating seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana: a non‐tissue culture approach. Molecular and General Genetics, 208, 1–9. Available from: 10.1007/BF00330414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, G. & Lakshmi Sita, G. (2003) Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation of eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) using root explants. Plant Cell Reports, 21, 549–554. Available from: 10.1007/s00299-002-0546-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, S. , Ghosh, G. , Ghosh, S. , Purohit, A. , Chaudhuri, R.K. , Das, S. et al. (2020) Plumular meristem transformation system for chickpea: an efficient method to overcome recalcitrant tissue culture responses. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 142, 493–504. Available from: 10.1007/s11240-020-01873-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.W. , Wang, K.Y. , Wang, N. , Li, J. , Li, G.Q. & Liu, D.H. (2018) Rapid and convenient transformation of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) using in planta shoot apex via glyphosate selection. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 172, 196–2203. Available from: 10.1016/S2095-3119(17)61865-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, H. , Linghu, Q. , Nagira, Y. , Miki, R. , Taoka, N. & Imai, R. (2017) An in planta biolistic method for stable wheat transformation. Scientific Reports, 7, 11443. Available from: 10.1038/s41598-017-11936-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, B. , Engler, D. , Moy, Y. , Newman, B. , Ralston, E. & Gutterson, N. (1999) A simple method to enrich an Agrobacterium‐transformed population for plants containing only T‐DNA sequences. The Plant Journal, 19, 727–734. Available from: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerster, G. , Wang, N. , Ryan, L. , Wu, E. & Anand, A. (2020) Use of non‐integrating Zm‐Wus2 vectors to enhance maize transformation. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. Plant, 56, 265–279. Available from: 10.1007/s11627-019-10042-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karthik, S. , Pavan, G. , Sathish, S. , Siva, R. , Kumar, P.S. & Manickavasagam, M. (2018) Genotype‐independent and enhanced in planta agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated genetic transformation of peanut [Arachis hypogaea (L.)]. 3 Biotech, 8, 202. Available from: 10.1007/s13205-018-1231-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, R.P. & Devi, S. (2019) In planta transformation in plants: a review. Agricultural Reviews, 40, 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, T. , Starr, D. , Su, X. , Tang, G. , Chen, Z. , Carter, J. et al. (2019) One‐step genome editing of elite crop germplasm during haploid induction. Nature Biotechnology, 37, 287–292. Available from: 10.1038/s41587-019-0038-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kereszt, A. , Li, D. , Indrasumunar, A. , Indrasumunar, A. , Nguyen, C.D.T. , Nontachaiyapoom, S. et al. (2007) Agrobacterium rhizogenes‐mediated transformation of soybean to study root biology. Nature Protocols, 2, 948–952. Available from: 10.1038/nprot.2007.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesiraju, K. , Tyagi, S. , Mukherjee, S. , Rai, R. , Singh, N.K. , Sreevathsa, R. et al. (2021) An apical meristem‐targeted in planta transformation method for the development of transgenics in flax (Linum usitatissimum): optimization and validation. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 562056. Available from: 10.3389/fpls.2020.562056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, M. , Suparthana, P. , Teixeira da Silva, J.A. & Nogawa, M. (2006) Development of in planta transformation methods using Agrobacterium tumefaciens . In: Teixeira da Silva, J.A. (Ed.) Floriculture, ornamental and plant biotechnology: advances and topical issues, Vol. 2. East Sussex, United Kingdom: Global Science Books, pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T. , Hu, J. , Sun, Y. , Li, B. , Zhang, D. , Li, W. et al. (2021) Highly efficient heritable genome editing in wheat using an RNA virus and bypassing tissue culture. Molecular Plant, 14, 1787–1798. Available from: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Z. , Nguyen, C.D. , Liu, L. , Wang, G. , Chen, J. , Wang, S. et al. (2022) Application of developmental regulators to improve in planta or in vitro transformation in plants. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 20, 1622–1635. Available from: 10.1111/pbi.13837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y. , Yang, Y. , Pan, G. & Shen, Y. (2022) New insights into tissue culture plant‐regeneration mechanisms. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 926752. Available from: 10.3389/fpls.2022.926752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, K. , Wu, E. , Wang, N. , Hoerster, G. , Hastings, C. , Cho, M.‐J. et al. (2016) Morphogenic regulators Baby boom and Wuschel improve monocot transformation. Plant Cell, 28, 1998–2015. Available from: 10.1105/tpc.16.00124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J. , Lu, S. , Su, C. , Deng, S. , Wang, M. , Tang, H. et al. (2024) Tissue culture‐free transformation of traditional Chinese medicinal plants with root suckering capability. Horticulture Research, 11(2), uhad290. Available from: 10.1093/hr/uhad290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z. , Jiang, R. , Chen, J. & Chen, W. (2020) Nanoparticle‐mediated gene transformation strategies for plant genetic engineering. The Plant Journal, 104, 880–891. Available from: 10.1111/tpj.14973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X. , Zhang, X. , Liu, H. & Li, Z. (2020) Highly efficient DNA‐free plant genome editing using virally delivered CRISPR–Cas9. Nature Plants, 6, 773–779. Available from: 10.1038/s41477-020-0704-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher, M.F. , Nasti, R.A. , Vollbrecht, M. , Starker, C.G. , Clark, M.D. & Voytas, D.F. (2020) Plant gene editing through de novo induction of meristems. Nature Biotechnology, 38, 84–89. Available from: 10.1038/s41587-019-0337-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, M.A. , Naqvi, R.Z. , Rahman, S.U. , Amin, I. & Mansoor, S. (2023) Plant virus‐derived vectors for plant genome engineering. Viruses, 15, 531. Available from: 10.3390/v15020531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangena, P. (2022) Plant transformation via Agrobacterium tumefaciens: culture conditions, recalcitrance and advances in soybean, 1st edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Martinell, B. , Julson, L.S. , Emler, C.A. , Huang, Y. , McCabe, D.E. & Williams, E.J. (2002) Soybean Agrobacterium transformation method. US Patent number 6384301.

- Mei, G. , Chen, A. , Wang, Y. , Li, S. , Wu, M. , Hu, Y. et al. (2024) A simple and efficient in planta transformation method based on the active regeneration capacity of plants. Plant Communications, 5, 100822. Available from: 10.1016/j.xplc.2024.100822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. , Eggenberger, A.L. , Lee, K. , Liu, F. , Kang, M. , Drent, M. et al. (2021) An improved biolistic delivery and analysis method for evaluation of DNA and CRISPR‐Cas delivery efficacy in plant tissue. Scientific Reports, 11, 7695. Available from: 10.1038/s41598-021-86549-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C. , Li, G. , Malzahn, A.A. , Cheng, Y. , Leyson, B. , Sretenovic, S. et al. (2022) Boosting plant genome editing with a versatile CRISPR‐Combo system. Nature Plants, 8, 513–525. Available from: 10.1038/s41477-022-01151-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que, Q. , Chilton, M.D.M. , Elumalai, S. , Zhong, H. , Dong, S. & Shi, L. (2019) Repurposing macromolecule delivery tools for plant genetic modification in the era of precision genome engineering. In: Kumar, S. , Barone, P. & Smith, M. (Eds.) Transgenic plants. Methods in molecular biology, Vol. 1864. New York, NY: Humana Press. Available from: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8778-8_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy, M. , Dominguez, M.M. , Irigoyen, S. , Padilla, C.S. & Mandadi, K.K. (2023) Rhizobium rhizogenes‐mediated hairy root induction and plant regeneration for bioengineering citrus. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 21, 1728–1730. Available from: 10.1111/pbi.14096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigoulot, S.B. , Barco, B. , Zhang, Y. , Zhang, C. , Meier, K.A. , Moore, M. et al. (2023) Automated, high‐throughput protoplast transfection for gene editing and transgene expression studies. In: Yang, B. , Harwood, W. & Que, Q. (Eds.) Plant genome engineering. Methods in molecular biology, Vol. 2653. New York, NY: Humana Press. Available from: 10.1007/978-1-0716-3131-7_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizwan, H.M. , Yang, Q. , Yousef, A.F. , Zhang, X. , Sharif, Y. , Kaijie, J. et al. (2021) Establishment of a novel and efficient Agrobacterium‐mediated in planta transformation system for passion fruit (Passiflora edulis). Plants, 10, 2459. Available from: 10.3390/plants10112459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, T. , Nakayama, I. , Nagayama, K. , Miyazawa, T. & Nezu, Y. (2002) Acetolactate synthase inhibitors. In: Böger, P. , Wakabayashi, K. & Hirai, K. (Eds.) Herbicide classes in development. Berlin, Germany: Springer‐Verlag, pp. 1–41. Available from: 10.1007/978-3-642-59416-8_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su, W. , Xu, M. , Radani, Y. & Yang, L. (2023) Technological development and application of plant genetic transformation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24, 10646. Available from: 10.3390/ijms241310646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezuka, D. , Cho, H. , Onodera, H. , Linghu, Q. , Chijimatsu, T. , Hata, M. et al. (2024) Redirecting barley breeding for grass production through genome editing of Photoperiod‐H1. Plant Physiology, 195, 287–290. Available from: 10.1093/plphys/kiae075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trick, H.N. & Finer, J.J. (1997) SAAT: sonication‐assisted Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation. Transgenic Research, 6, 329–336. Available from: 10.1023/A:1018470930944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trieu, A.T. , Burleigh, S.H. , Kardailsky, I.V. , Maldonado‐Mendoza, I.E. , Versaw, W.K. , Blaylock, L.A. et al. (2000) Transformation of Medicago truncatula via infiltration of seedlings or flowering plants with Agrobacterium . The Plant Journal, 22, 531–541. Available from: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00757.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, M. , Butruille, D. , Achard, F. , Beach, S. , Brower‐Toland, B. , Cargill, E. et al. (2024) Simultaneous genetic transformation and genome editing of mixed lines in soybean (Glycine max) and maize (Zea mays). aBIOTECH, 5, 169–183. Available from: 10.1007/s42994-024-00173-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valvekens, D. , Montagu, M.V. & Lijsebettens, M.V. (1988) Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana root explants by using kanamycin selection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 85(15), 5536–5540. Available from: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasil, I.K. (1994) Automation of plant propagation. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 39, 105–108. Available from: 10.1007/BF00033917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan, V. , Sathish, D. , Ajithan, C. , Sathish, S. & Manickavasagam, M. (2021) Efficient Agrobacterium‐mediated in planta genetic transformation of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus Thunb.). Plant Biotechnology Reports, 15, 447–457. Available from: 10.1007/s11816-021-00691-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A. , Narváez‐Vásquez, J. , Mozoruk, J. , Niu, Z. , Luginbühl, P. , Sanders, S. et al. (2023) Industrial scale gene editing in Brassica napus . International Journal of Plant Biology, 14, 1064–1077. Available from: 10.3390/ijpb14040077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. , Shi, L. , Liang, X. , Zhao, P. , Wang, W. , Liu, J. et al. (2022) The gene TaWOX5 overcomes genotype dependency in wheat genetic transformation. Nature Plants, 8, 110–117. Available from: 10.1038/s41477-021-01085-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. , Zhang, B. & Wang, Q. (2013) Cotton transformation via pollen tube pathway. In: Zhang, B. (Ed.) Transgenic cotton. Methods in molecular biology, Vol. 958. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. Available from: 10.1007/978-1-62703-212-4_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. , Ryan, L. , Sardesai, N. , Wu, E. , Lenderts, B. , Lowe, K. et al. (2023) Leaf transformation for efficient random integration and targeted genome modification in maize and sorghum. Nature Plants, 9, 255–270. Available from: 10.1038/s41477-022-01338-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. , Cui, G. , Wang, Y. , Hao, Y. , Du, J. , Zhang, H. et al. (2017) Expression of foreign genes demonstrates the effectiveness of pollen‐mediated transformation in Zea mays . Frontiers in Plant Science, 8, 383. Available from: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. , Machin, F. , Wang, S. , Saplaoura, E. & Kragler, F. (2023) Heritable transgene‐free genome editing in plants by grafting of wild‐type shoots to transgenic donor rootstocks. Nature Biotechnology, 41, 958–967. Available from: 10.1038/s41587-022-01585-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X. , Shrawat, A. , Williams, E. , Rivlin, A. , Vaghchhipawala, Z. , Moeller, L. et al. (2022) Commercial scale genetic transformation of mature seed embryo explants in maize. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 1056190. Available from: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1056190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y. , Yu, H. , Peng, J. , Yao, W.J. , Wang, Y.P. , Zhang, F.L. et al. (2024) Enhancing wheat regeneration and genetic transformation through overexpression of TaLAX1 . Plant Communications, 5, 100738. Available from: 10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. , Zuo, Z. , Zhu, Y. , Feng, Y. , Wang, Y. , Zhao, H. et al. (2023) Fast track to obtain heritable transgenic sweet potato inspired by its evolutionary history as a naturally transgenic plant. Plant Biotechnology Journal, 21, 671–673. Available from: 10.1111/pbi.13986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H. , Li, C. , Yu, W. , Zhou, H.‐p. , Lieber, T. , Su, X. et al. (2024) A fast and genotype‐independent in planta Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation method for soybean. Plant Communications, 5, 101063. Available from: 10.1016/j.xplc.2024.101063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G. , Weng, J. , Zheng, Y. , Huang, J. , Qian, S. & Liu, G. (1983) Introduction of exogenous DNA into cotton embryos. Methods in Enzymology, 101, 433–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M. , Luo, J. , Xiao, D. , Wang, A. , He, L. & Zhan, J. (2023) An efficient method for the production of transgenic peanut plants by pollen tube transformation mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens . Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 152, 207–214. Available from: 10.1007/s11240-022-02388-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]