Highlights

-

•

Lysyl Oxidase (LOX) family is aberrantly expressed in a variety of tumors.

-

•

Aberrant expression of LOX family is associated with CRC progression.

-

•

Targeting LOX proteins by inhibitors may provide novel strategies for CRC treatment.

Keywords: Lysyl oxidase, Colorectal cancer, Therapeutic targets

Abstract

The lysine oxidase (LOX) family, consisting of LOX and LOX-like-1–4 (LOXL1–LOXL4), catalyses the cross-linking reaction of collagen and elastin in the extracellular matrix (ECM). Numerous studies have demonstrated that LOX family members are dysregulated in a variety of cancers, including colorectal cancer (CRC), and play a key role in cancer cell migration, proliferation, invasion and metastasis. Targeting LOX family proteins with specific inhibitors has therefore been developed as a new therapeutic strategy for cancer. In this paper, we review the role of LOX enzymes in the development and progression of CRC. In addition, we address recent advances in the development of LOX/LOXL inhibitors, highlighting the potential use of this inhibitor as an effective and complementary treatment for CRC.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The lysyl oxidase (LOX) family, a group of copper-dependent amine oxidases, is comprised of LOX and LOX-like-1 to 4 (LOXL1, LOXL2, LOXL3, LOXL4) [[1], [2], [3]]. The catalytic domain of the LOX family harbours a functional quinone group, generated through posttranslational cross-linkage between tyrosine residues and specific lysine, which is known as lysyl tyrosylquinone (LTQ). The main function of the LOX enzymes is to catalyse the covalent cross-linking of elastin and collagens in the extracellular matrix (ECM), which leads to an increase in tissue tensile strength and contributes to structural integrity by stabilising fibrous deposits [[4], [5], [6]]. The LOX family members are constitutively expressed in a variety of human tissues [7], and their catalysing process is closely involved in adult tissue remodelling and normal embryonic development. The abnormal expression and regulation of LOX family enzymes have been identified as the underlining cause of a wide range of diseases that are predominantly associated with ECM changes, such as liver fibrosis [8], cancers [9,10] and Wilson's disease [11]. In the context of cancer, LOX family proteins have been increasingly recognised for their critical roles in tumour progression. They contribute to cancer cell migration, proliferation, invasion and metastasis, making them significant players in the tumour microenvironment. Consequently, LOX family proteins have been evaluated as potential biomarkers for early cancer diagnosis and as novel therapeutic targets. In colorectal cancer (CRC), the dysregulation of LOX family members has been linked to various aspects of tumour development and progression [[12], [13], [14]]. In this study, we comprehensively review the role of LOX family members in CRC based on pathological (cancer specimens), biochemical (mechanism and cellular function) and physiological (animal models) evidence. Moreover, we highlight that specific inhibitors that target LOX family proteins may provide a promising strategy for CRC treatment.

Overview of the lysyl oxidase family and its role in cancer

Overview of the lysyl oxidase family

The LOX family's role in catalysing the formation of covalent cross-links in collagen and elastin fibres is essential for the stabilisation of the ECM [4]. This process is essential for the stabilisation of the ECM. In particular, LOX and LOXL2 are upregulated by hypoxia and are known to promote tumour cell invasion and metastasis. These enzymes also produce hydrogen peroxide as a byproduct, which can activate the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signalling pathway [9].The LOX family members share highly conserved C-terminal regions that contain their catalytic domains, featuring a copper-binding site and a unique LTQ structure, necessary for their enzymatic activity. The N-terminal regions are more diverse, dividing the family into two subgroups. Moreover, LOX and LOXL1 are synthesised as pro-enzymes activated by bone morphogenic protein-1 protease, whereas LOXL2, LOXL3 and LOXL4 contain scavenger receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) domains. These SRCR domains are associated with additional enzymatic functions, such as protein deacetylation and deacetylimination, which are particularly notable in LOXL3 through its interaction with Stat3 in the cell nucleus [2,3] (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

The structure of LOX family members. These members have a highly conserved C-terminal domain and a variable N-terminal domain. The composition of C-terminal domain contains copper binding domain, amino acid residues forming lysine tryosylquinone (LTQ), cofactor formation, and a cytokine receptor-like (CRL) domain. The N-terminal region of LOX and LOXL1 has the prodomains, whereas the N-terminal of LOXL2–4 has four scavenger-receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) domains.

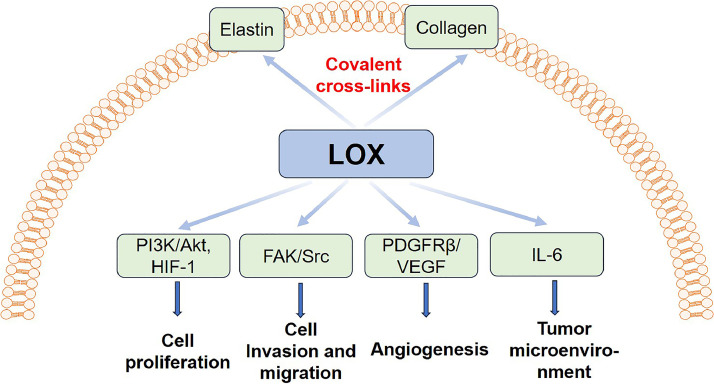

Fig. 2.

Molecular mechanisms of LOX promoting CRC development.

Lysyl oxidase family in cancer

Lysyl oxidases were first recognised for their role in promoting tumour progression in two key studies. The first study revealed that the overexpression of LOX or LOXL2 increased breast cancer cell invasion in vitro [9]. The second study demonstrated that LOXL2 overexpression in a breast cancer mouse model enhanced invasiveness, induced desmoplasia and led to the deposition of thick collagen bundles in tumours with high LOXL2 expression [10]. These effects are not limited to breast cancer, as LOX has been found to drive the progression of colorectal, cervical, ovarian, lung, gastric and renal cancers [2]. Similarly, LOXL2 promotes tumour progression in colorectal, gastric, oesophageal, cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular, lung and renal cancers [14]. Further research has determined that other LOX enzymes also contribute to cancer progression, with LOXL3 enhancing melanoma progression, working with BRAF in melanocyte transformation and increasing the invasiveness and metastasis of breast cancer cells [6]. These findings highlight the significant role of LOX enzymes in various cancers and emphasise their potential as therapeutic targets.

Lysyl oxidase family expression

The LOX family enzymes are widely distributed in human tissues and have a spatiotemporal expression pattern. They are expressed at relatively high levels in tissues, including fat, gall bladder, lung, skin and colon tissues, and at low levels in the brain, pancreas and bone marrow (Fig. 3) [7]. To understand the expression of the LOX family in CRC, their transcriptional and translational levels have been determined in patients with CRC as well as in CRC cell lines and animal models.

Fig. 3.

Transcript levels of LOX family members in mouse and normal human tissues. Data were extracted from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Blue, white, and red shades represent low, median, and high abundance, respectively. The deeper the blue, the lower the expression; the deeper the red, the higher the expression[7].

Lysyl oxidase family expression patterns

Studies on LOX expression levels in human CRC appear to be conflicting. Csiszar K et al. reported decreased LOX mRNA levels in colon tumour samples (75 %, 6/8) compared with matched normal colon, concluding that the loss of or decreased LOX function is associated with colon tumour pathogenesis [15]. However, the sample size of this study was relatively small (n = 8), and no relationship between LOX expression levels and CRC tumour stage was mentioned. Notably, Baker AM et al. identified a significantly increased expression of LOX protein levels in CRC primary tumour tissues (n = 66) compared with normal colon tissues [16]. Moreover, to assess the relative expression levels of LOX at each stage of CRC, the authors further demonstrated that LOX staining was significantly increased in normal versus tumour tissues and tumour versus metastatic tissues by using immunohistochemical staining assays. Similar studies have reached the same conclusion, that LOX expression is significantly increased in human CRC tissues, which is further supported by in vitro and in vivo experiments [[17], [18], [19]]. The significant downregulation of LOXL1 expression was found in CRC tissues. Lin Hu et al. evaluated the protein expression levels of LOXL1 in 30 paired CRC and adjacent normal tissues, revealing that LOXL1 expression was significantly lower in CRC samples than in adjacent non-tumour samples [20]. Consistent with this, the mRNA expression of LOXL1 was downregulated in CRC compared with adjacent normal tissues (n = 15), and LOXL2 mRNA expression levels were significantly elevated in CRC tissues compared with normal colon tissues [21]. Moreover, LOXL2 protein expression was upregulated in CRC and found to be associated with TNM stage and shortened patient survival time [22]. Similar results were found in another study, in which LOXL2 expression was increased in 44 % of CRC samples compared with normal tissues [23], and LOXL3 and LOXL4 were found to be upregulated in CRC tissues compared with adjacent normal colon tissues. In a study including 104 patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma who underwent curative surgery, LOXL3 and LOXL4 expression levels were found to be increased in primary tumour tissues [24]. In addition, the authors noted that LOXL4 exhibited a statistically significant upregulation in tumours without lymphovascular invasion. Notably, researchers have found that LOXL4 protein is expressed by neutrophils present in the tumour microenvironment, and their expression is higher in circulating neutrophils from patients with cancer compared with healthy controls [25]. In summary, with the exception of LOXL1, LOX family members (LOX, LOXL2, LOXL3, LOXL4) are upregulated in CRC tissues. However, studies with large sample sizes are needed to further elucidate the expression pattern of LOX family members in CRC, as some of the aforementioned reports contain relatively small sample sizes.

Role of the lysyl oxidase family in colorectal cancer progression

Lysyl oxidase acts as an oncoprotein, promotes proliferation, invasion and metastasis, and is involved in poor survival

The role of the LOX protein in CRC has been extensively studied. Its expression is increased in CRC tissues and correlates with tumour progression, including tumour grade, tumour stage, T stage and metastasis. Wei B et al. [17]. discovered that LOX promoted CRC progression and metastasis by enhancing ECM stiffening. Moreover, P-selectin-mediated platelet accumulation acted as an upstream regulator and increased LOX expression, whereas P-selectin deficiency markedly decreased tissue stiffness through the inhibition of LOX expression. Furthermore, ECM stiffening enhancement and tumour growth were counteracted by the LOX inhibitor β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN) [17]. Another mechanism through which LOX increased ECM stiffness was the activation of the FAK/SRC signalling pathway [26]. The FAK/SRC signalling pathway plays a key role in tumour development, particularly in promoting proliferation, migration and the invasion of tumour cells. Activation of the FAK/SRC signalling pathway can promote the expression of multiple cytokines, such as cyclin D1 and cyclin D3, which promote tumour development [26]. Moreover, LOX is closely associated with blood vessel density in CRC samples and enhances angiogenesis in CRC mouse models through the platelet-derived growth factor receptor β-mediated activation of Akt, leading to the upregulation of VEGF transcription and secretion. The VEGF class of proteins support tumour growth and metastasis by promoting angiogenesis [10]. The enhanced expression of LOX in CRC cells facilitates cancer proliferation and metastasis by activating SRC [16]. Moreover, LOX and hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1 act in synergy to foster tumour formation by activating phosphoinositide 3-kinase [27]. The nuclear localisation of LOX correlates with CRC lung/hepatic metastasis and is strongly associated with poor survival. In addition, LOX is a potential target gene of Yes-associated protein (YAP) and TEAD4, which are components of the Hippo signalling pathway [28]. It also triggers CRC tumour cell colonisation in bone by inducing interleukin 6 production, which results in osteoclast differentiation, creating an imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation [18]. Interleukin 6 plays a key role in the tumour microenvironment and can promote the M2-type polarisation of tumour-associated macrophages and inhibit antitumour immune responses, thereby providing tumour cells with the opportunity for immune evasion and promoting the further development of tumours [18]. Although one study indicated that LOX expression was decreased in CRC and acted as a tumour suppressor [15], a meta-analysis with a total of 2377 patients with cancer and 2499 controls revealed that LOX was upregulated in CRC and LOX polymorphism, playing a role in cancer risk in Asian populations [29]. Taken together, LOX acts as an oncoprotein by promoting CRC proliferation, invasion and metastasis through various mechanisms, such as enhancing ECM stiffening, promoting angiogenesis and inducing impaired bone homeostasis.

Several reports support a role for LOX as a tumour suppressor, noting decreased LOX expression at both mRNA and protein levels in tumour tissues compared with matched normal tissues and in vitro cell lines. This downregulation is thought to be controlled through promoter methylation. Silencing LOX is associated with a more aggressive tumour phenotype and decreased patient survival, suggesting its function as a metastasis promoter [1]. However, the tumour suppressor activity of LOX is believed to reside in the propeptide domain, released after extracellular cleavage from the mature enzyme. The LOX propeptide re-enters the cell, potentially directed to the nucleus, where it can repress the oncogenic bcl-2 gene in breast cancer and inhibit FGF-2 signalling in prostate cancer. It also inhibits signalling pathways that activate nuclear factor-B in prostate and lung cancers, indicating multiple mechanisms by which it may exert its tumour suppressor effects [29].

Lysyl oxidase-like-1 suppresses the progression of colorectal cancer

At present, there are comparatively few studies on LOXL1 in CRC, and its effect remains largely unknown. Hu L et al. [20] discovered that LOXL1 expression was increased in healthy colon tissues compared with CRC tissues, silencing the LOXL1-enhanced invasion, migration and colony formation of CRC cells in vivo and in vitro, whereas the opposite effects were identified in LOXL1 overexpression assay. Furthermore, LOXL1 exerted antitumour effects by downregulating YAP activity [20]. However, more studies are needed to further validate the expression and role of LOXL1 in CRC.

Lysyl oxidase-like-2 exerts an oncogenic function in colorectal cancer

The upregulation of LOXL2 was identified in the ECM as well as CRC cells and associated with TNM stage [22]. The downregulation of LOXL2 not only diminished the migratory and proliferative abilities of CRC cells in vitro and in vivo but also induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [22]. One of the underlying mechanisms of LOXL2-mediated EMT is through the activation of the FAK/SRC signalling pathway and stabilisation of SNAIL [30]. Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) was discovered to be an upstream transcriptional molecular of LOXL2, promoting LOXL2 transcription and expression by binding directly to its promoter, leading to increased CRC cell invasion and disease progression [31]. Torres S et al. [23]. followed 12 patients with CRC at stage II and III for more than 5 years to investigate the relationship between LOXL2 expression and recurrence, demonstrating that high expression of LOXL2 was associated with increased recurrence rates. Moreover, the authors demonstrated that LOXL2 could be used as an independent and highly predictive prognostic factor for relapse and survival in patients with CRC [23]. Similarly, LOXL2 was discovered to play a role in abnormal collagen remodelling in CRC and associated with metastasis and tumourigenesis, leading to poor prognosis [3]. The expression of LOXL2 was found to increase with rising concentrations of 5-FU in CRC cells, leading to the inhibition of 5-FU-induced apoptosis and augmenting the proliferation of CRC cells [32]. Furthermore, LOXL2 reduced 5-UF sensitivity in CRC through the activation of the Hedgehog signalling pathway by promoting GLI1, GLI2 and SMO, leading to the increased expression of BCL2 [32], and LINC01347 promoted LOXL2 expression by sponging miR-328–5p, contributing to 5-FU-based chemotherapy resistance in CRC [33]. In summary, high LOXL2 expression levels in CRC are associated with poor prognosis and increased recurrence and contribute to 5-FU-based chemotherapy resistance.

Lysyl oxidase-like-3 increases migration and invasion in colorectal cancer cells and is associated with poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer

Ren J et al. [34]. discovered that LOXL3 expression was elevated in CRC cells, leading to increased migration and invasion [34]. The high expression of LOXL3 augmented SNAIL, VIM and ZEB1 and repressed E-cadherin. The upregulation of LOXL3 expression was associated with lymph node metastasis and poor survival in CRC. Moreover, LOXL3 was a direct target of miR-34a, and the deregulation of the miR-34/ LOXL3 axis led to desflurane-induced EMT [34]. However, more studies are needed to further validate the oncogenic role of LOXL3 in CRC.

Lysyl oxidase-like-4

Palmieri V et al. [25] reported that LOXL4 was significantly upregulated in CRC with lymphovascular invasion, but its mechanisms were not fully investigated. The expression of LOXL4 was increased in the circulating neutrophils of patients with CRC compared with healthy controls, which could be caused by the stimulation of TNF-α and lipopolysaccharide [25]. However, the role of LOXL4 in CRC has not been fully clarified; thus, more studies are required to verify its function in CRC tumourigenesis (Table 1).

Table 1.

LOX family expression and their role in CRC.

| LOX family members | Expression level | Sample | Function | Mechanism/regulators | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOX | upregulated | CRC tissues (n = 255) | Correlated CRC progression and CRC poor prognosis. with and | P-selectin-mediated platelet aggregation up-regulate LOX expression. | [17] |

| upregulated | CRC tissue microarray, CRC cell lines | Promotes angiogenesis | Enhance the remodeling and stiffening of the tumor ECM activates Akt through platelet derived (PDGFRβ) stimulation, which leads to increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression | [10] | |

| - | CRC cell lines | promote tumor cell proliferation and progression | Activate PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase)–Akt signaling pathway to increase HIF-1a protein synthesis | [27] | |

| Upregulated | CRC tissues (n = 510) | Increase tumor growth and metastasis | Activation of SRC | [16] | |

| Upregulated | CRC tissues (n = 201) | Associated with poor survival, nuclear LOX expression correlated with synchronous or postoperative lung/hepatic metastasis. | Potential target gene of YAP and TEAD4 | [28] | |

| downregulated | CRC tissues (n = 552) | Triggers CRC tumor cell colonization in bone | - | [18] | |

| - | CRC tissues (n = 8) | Tumor suppressor | Inducing IL-6 production | [15] | |

| Upregulated | CRC cell lines and animal models | Promote CRC progression | Mutations of LOX gene | [26] | |

| Upregulated | CRC tissues | Increased risk of CRC | Activation of the FAK (focal adhesion kinase)/SRC-signaling pathway | [29] | |

| Upregulated | CRC cells | Contributes to 5-FU chemotherapy resistance | LOX polymorphism that with the AA or AG genotype had higher susceptibility to CRC occurrence LINC01347/miR-328–5p axis | [33] | |

| LOX-1 | Downregulated | CRC tissues (n = 30) | tumour suppressor | Negative regulation of Yes-associated protein (YAP) activity. | [20] |

| LOX-2 | Upregulated | Colon cancer tissues (n = 12) | Associate with poor survival | - | [23] |

| Upregulated | Paired CRC and normal adjacent tissues (n = 40) | Promotes the development of CRC and act as an independent prognostic factor | - | [22] | |

| Upregulated | CRC tissues (n = 56) | Associated with the tumorigenesis and metastasis, affecting the prognosis | - | [3] | |

| Upregulated | CRC cell lines | Promotes CRC metastasis | Activation of FAK/Src signaling and the stabilization of Snail | [30] | |

| Upregulated | CRC cell lines | Increase CRC cell migration and invasion, but not proliferation | ZEB1 enhances LOXL2 transcription and expression through direct binding to its promoter. | [31] | |

| Upregulated | CRC cell lines and CRC tissues | Elevated LOXL2 increases the resistance to 5-FU | Activate Hedgehog/ BCL2 signaling | [32] | |

| LOX-3 | Upregulated | CRC cells | Increase migration and invasion | miR-34/ LOXL3 axis | [34] |

| LOX-4 | Upregulated | CRC tissues (n = 104) | Associate with lymphovascular invasion | - | [24] |

Lysyl oxidase family as therapeutic targets for colorectal cancer

As detailed above, many studies have revealed that LOX family members, in particular LOX and LOXL2, augment the progression of CRC. This indicates that LOX inhibitors may be promising therapeutic agents for the treatment of CRC.

Lysyl oxidase/lysyl oxidase-like-2 inhibitors

β-aminopropionitrile

β-aminopropionitrile was the first non-specific and irreversible LOX inhibitor [35]. It exerts anti-cancer effects by covalently binding to LTQ cofactors in proteins, inhibiting the catalytic activity of the LOX family [36]. For example, Payne SL et al.[37] discovered that treating invasive breast cancer cells with BAPN led to a significant decrease in cell migration and adhesion formation. In animal models, BAPN administration significantly reduced the frequency of metastases [38]. Notably, when BAPN treatment was initiated the day before or the same day as the injection of tumour cells, the number of metastases decreased by 44 % and 27 %, respectively, whereas BAPN had no effect on the growth of established metastases [38] but did inhibit the invasion and migration capacities of cervical carcinoma cells in vitro [39]. In addition, BAPN impeded the progression of gastric cancer, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and oral squamous cell carcinoma [[40], [41], [42], [43]]. However, because BAPN lacks amenable sites for chemical modification and variable selectivity, it cannot be used effectively in clinical drug development.

Simtuzumab

Simtuzumab is a humanised IgG4 monoclonal antibody to LOXL2. In a phase I study, simtuzumab was given to patients with advanced solid tumours, including five patients with CRC, at doses of 1, 3, 10 and 20 mg/kg every 2 weeks to evaluate its safety and pharmacokinetics [44]. No drug-related severe adverse events (AEs) were observed, and the mean terminal T1/2 was approximately 20 days [44]. The authors continued with a phase IIa study; 11 patients with CRC with a KRAS mutation were given 700 mg of simtuzumab combined with 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) intravenously every 2 weeks. The results revealed that simtuzumab was well tolerated, and the most common treatment-emergent AEs were diarrhoea, fatigue and nausea. Thus, simtuzumab combined with FOLFIRI demonstrated promising efficacy in patients with KRAS-mutant CRC in the phase IIa study [44]. However, the following phase II study produced contradictory results [14]. In this study, 249 patients with metastatic KRAS-mutant CRC were recruited and randomly treated with 700 mg of FOLFIRI/simtuzumab (n = 84), 200 mg of FOLFIRI/simtuzumab (n = 85) or FOLFIRI/placebo (n = 80) every 2 weeks in cycles of 28 days. Overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR) and safety were assessed. The results revealed a median OS of 11.4 (p = .25), 10.5 (p = .06) and 16.3 months, respectively. The median PFS for each of the respective treatment groups was 5.5 (p-value versus placebo; p = .10), 5.4 (p = .04) and 5.8 months, respectively. The ORR was 11.9 %, 5.9 % and 10 %, respectively. Consistent with the phase I and IIa studies, simtuzumab was well tolerated in patients with metastatic KRAS-mutant CRC [14].

Simtuzumab was also used to treat other diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) [45], pancreatic adenocarcinoma [46] and primary sclerosing cholangitis [47]. Raghu G et al. [45] evaluated the efficacy and safety of simtuzumab in IPF in a randomised, double-blind, phase II trial. In this study, 544 patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive placebo or 125 mg/mL of simtuzumab injected subcutaneously once a week. The results demonstrated that simtuzumab was well tolerated but did not improve PFS in patients with IPF [45]. In another clinical trial, 240 patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (mPaCa) were randomly assigned to receive 1000 mg/m2 of gemcitabine intravenously combined with 200 or 700 mg of simtuzumab or placebo. The authors determined that simtuzumab together with gemcitabine did not improve clinical outcomes in patients with mPaCa [46]. Muir AJ et al. [47] investigated the safety and efficacy of simtuzumab in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. The study included 234 patients randomised (1:1:1) to receive weekly subcutaneous injections of 75 or 125 mg of simtuzumab or placebo for up to 96 weeks. Compared with placebo, simtuzumab treatment did not improve the Ishak fibrosis score, frequency of clinical events or progression to cirrhosis [47]. Similarly, simtuzumab treatment was ineffective in decreasing hepatic collagen content or hepatic venous pressure gradient in patients with bridging fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [48]. In general, simtuzumab demonstrated positive results in preclinical studies and was well tolerated in phase I studies. However, simtuzumab did not improve clinical outcomes in the phase II studies of various cancers and fibrotic diseases. The underlining causes of ineffective treatment using simtuzumab have not been determined; thus, further studies are required to elucidate its mechanisms and develop more effective treatments.

PXS compounds

The PXS compounds are haloallylamine-based inhibitors that are mechanism-based and possess amenable sites for chemical modification [49]. The first generation of PXS compounds that displays similar activity and selectivity to BAPN is PXS-S1A. To improve LOXL2 potency, structural modifications based on PXS-S1A were performed, leading to the discovery and generation of PXS-S2A, a highly selective and potent LOXL2 inhibitor [49]. Both PXS-S1A and PXS-S2A inhibited proliferation, migration and cancer-associated fibroblast activation in a triple negative human breast cancer model [49]. Moreover, PXS-5120A, an irreversible inhibitor of LOXL2 and LOXL3, demonstrated promising anti-fibrotic activity in lung and liver fibrosis models [50]. However, few studies have focused on the application of PXS compounds in CRC (Table 2).

Table 2.

LOX family member inhibitors.

| Agents | Characterization | Targets | Cancers | Cell/animal models | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAPN | Small-molecule inhibitor | LOX | breast cancer | MDA-MB-231 | Inhibits metastatic colonization | [38] |

| LOX | cervical cancer | HeLa and SiHa | inhibits invasion and migration capacities of cervical carcinoma cells in vitro | [39] | ||

| LOX | gastric cancer | HGC27 and N87 | hamper outgrowth of GC liver metastasis | [42] | ||

| LOX | Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma | 8505C | Suppresses the proliferation, migration, and invasion of ATC cells | [41] | ||

| LOX | hepatocellular carcinoma | HuH-7 | Impedes angiogenesis in HCC cell lines | [43] | ||

| LOX | oral squamous cell carcinoma | SAS and SVEC4–10 | Impedes proliferation and angiogenesis | [40] | ||

| Simtuzumab | humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody | LOXL 2 | metastatic KRAS mutant CRC | 249 patients | ddition of simtuzumab to FOLFIRI did not improve clinical outcomes | [14] |

| LOXL2 | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 544 patients | did not improve progression-free survival | [45] | ||

| LOXL 2 | Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma | 240 | The addition of simtuzumab to gemcitabine did not improve clinical outcomes in patients with mPaCa | [46] | ||

| LOXL 2 | Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis | 234 patients | Treatment with simtuzumab did not provide clinical benefit in patients with PSC | [47] | ||

| LOXL 2 | patients with advanced fibrosis caused by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. | 219 | did not improve clinical outcomes | [48] | ||

| PXS-S1A and PXS-S2A | Small-molecule inhibitor | LOX/ LOXL2 | Breast cancer model | MDA-MB-231 | inhibited proliferation, migration and cancer-associated fibroblast activation | [49] |

| PXS-512 0A | Small-molecule inhibitor | Loxl2 /LOXL 3 | liver and lung fibrosis models | - | anti-fibrotic activity | [50] |

Conclusion

The LOX family is dysregulated in CRC tissues and plays a critical role in cancer cell migration, proliferation, invasion and metastasis. The expression of LOX is increased in CRC tissues and correlates with the progression of tumours, including tumour grade, tumour stage, T stage and metastasis. Moreover, LOXL1 suppresses the progression of CRC by downregulating YAP activity. The high expression levels of LOXL2 in CRC is associated with poor prognosis and increased recurrence rates and contributes to 5-FU-based chemotherapy resistance. The expression of LOXL3 is elevated in CRC cells, leading to increased migration and invasion. In addition, LOXL4 is significantly upregulated in CRC with lymphovascular invasion, but its mechanisms have not been fully investigated. However, the function of LOXL1, LOXL3 and LOXL4 in CRC carcinogenesis remains undetermined. Therefore, more studies are needed to identify the role of LOXL1, LOXL3 and LOXL4 in CRC development and progression. The development of LOX family inhibitors (except for LOXL1) is beneficial for patients with CRC with LOX family overexpression. A growing number of LOX family inhibitors have been developed in recent years, some of which have demonstrated positive results in different types of cancers. However, clinical studies evaluating the efficacy of LOX family inhibitors in CRC remain scarce. High-throughput screening of small molecular inhibitors for the suppression of LOX family members is needed to identify specific inhibitors for each member.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Muxian Liu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Jie Wang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis. Meihong Liu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding in any form.

References

- 1.Zhu Z. Serum LOXL2 is elevated and an independent biomarker in patients with coronary artery disease. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024;17:4071–4080. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S478044. Sep 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox TR, Erler JT. Lysyl oxidase in colorectal cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013;305(10):G659–G666. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00425.2012. Nov 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Wang X, Liu R, et al. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) family proteins: key players in breast cancer occurrence and progression. J. Cancer. 2024;15(16):5230–5243. doi: 10.7150/jca.98688. Aug 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox TR, Gartland A, Erler JT. Lysyl oxidase, a targetable secreted molecule involved in cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:188–192. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YM, Kim EC, Kim Y. The human lysyl oxidase-like 2 protein functions as an amine oxidase toward collagen and elastin. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011;38:145–149. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye M, Song Y, Pan S, et al. Evolving roles of lysyl oxidase family in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;215 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Yang A, Jia J, et al. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) family members: rationale and their potential as therapeutic targets for liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2020;72:729–741. doi: 10.1002/hep.31236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harlow CR, Wu X, van Deemter M, et al. Targeting lysyl oxidase reduces peritoneal fibrosis. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Min C, Kirsch KH, Zhao Y, et al. The tumor suppressor activity of the lysyl oxidase propeptide reverses the invasive phenotype of Her-2/neu-driven breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1105–1112. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker AM, Bird D, Welti JC, et al. Lysyl oxidase plays a critical role in endothelial cell stimulation to drive tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:583–594. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vadasz Z, Kessler O, Akiri G, et al. Abnormal deposition of collagen around hepatocytes in Wilson's disease is associated with hepatocyte specific expression of lysyl oxidase and lysyl oxidase like protein-2. J. Hepatol. 2005;43:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong L, Zhang Y, Yang Y, et al. Inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like 2 overcomes adhesion-dependent drug resistance in the collagen-enriched liver cancer microenvironment. Hepatol. Commun. 2022;6:3194–3211. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leeming DJ, Willumsen N, Sand JMB, et al. A serological marker of the N-terminal neoepitope generated during LOXL2 maturation is elevated in patients with cancer or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2019;17:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hecht JR, Benson AB, 3rd, Vyushkov D, et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of simtuzumab in combination with FOLFIRI for the second-line treatment of metastatic KRAS mutant colorectal adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2017;22(3):243. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0479. e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Csiszar K, Fong SF, Ujfalusi A, et al. Somatic mutations of the lysyl oxidase gene on chromosome 5q23.1 in colorectal tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 2002;97:636–642. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker AM, Cox TR, Bird D, et al. The role of lysyl oxidase in SRC-dependent proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011;103:407–424. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei B, Zhou X, Liang C, et al. Human colorectal cancer progression correlates with LOX-induced ECM stiffening. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017;13:1450–1457. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.21230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynaud C, Ferreras L, Di Mauro P, et al. Lysyl Oxidase is a strong determinant of tumor cell colonization in bone. Cancer Res. 2017;77:268–278. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward ST, Weston CJ, Hepburn E, et al. Evaluation of serum lysyl oxidase as a blood test for colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014;40:731–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu L, Wang J, Wang Y, et al. LOXL1 modulates the malignant progression of colorectal cancer by inhibiting the transcriptional activity of YAP. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020;18:148. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00639-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu J, Tang W, Du P, et al. Identifying microRNA-mRNA regulatory network in colorectal cancer by a combination of expression profile and bioinformatics analysis. BMC Syst. Biol. 2012;6:68. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui X, Wang G, Shen W, et al. Lysyl oxidase-like 2 is highly expressed in colorectal cancer cells and promotes the development of colorectal cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2018;40:932–942. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torres S, Garcia-Palmero I, Herrera M, et al. LOXL2 is highly expressed in cancer-associated fibroblasts and associates to poor colon cancer survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:4892–4902. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Differential expression of the LOX family genes in human colorectal adenocarcinomas. Oncol. Rep. 2009;22 doi: 10.3892/or_00000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmieri V, Lazaris A, Mayer TZ, et al. Neutrophils expressing lysyl oxidase-like 4 protein are present in colorectal cancer liver metastases resistant to anti-angiogenic therapy. J. Pathol. 2020;251:213–223. doi: 10.1002/path.5449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker AM, Bird D, Lang G, et al. Lysyl oxidase enzymatic function increases stiffness to drive colorectal cancer progression through FAK. Oncogene. 2013;32:1863–1868. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pez F, Dayan F, Durivault J, et al. The HIF-1-inducible lysyl oxidase activates HIF-1 via the Akt pathway in a positive regulation loop and synergizes with HIF-1 in promoting tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1647–1657. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Wang G, Liang Z, et al. Lysyl oxidase: A colorectal cancer biomarker of lung and hepatic metastasis. Thorac Cancer. 2018;9:785–793. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao X, Zhang S, Zhu Z. Lysyl oxidase rs1800449 polymorphism and cancer risk among Asians: evidence from a meta-analysis and a case-control study of colorectal cancer. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2015;290:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0896-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park PG, Jo SJ, Kim MJ, et al. Role of LOXL2 in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and colorectal cancer metastasis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:80325–80335. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang F, Sun G, Peng C, et al. ZEB1 promotes colorectal cancer cell invasion and disease progression by enhanced LOXL2 transcription. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2021;14:9–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiu Z, Qiu S, Mao W, et al. LOXL2 reduces 5-FU sensitivity through the Hedgehog/BCL2 signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2023;248(6):457–468. doi: 10.1177/15353702221139203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng GL, Liu YL, Yan ZX, et al. Elevated LOXL2 expression by LINC01347/miR-328-5p axis contributes to 5-FU chemotherapy resistance of colorectal cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021;11:1572–1585. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren J, Wang X, Wei G, et al. Exposure to desflurane anesthesia confers colorectal cancer cells metastatic capacity through deregulation of miR-34a/LOXL3. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2021;30:143–153. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barry-Hamilton V, Spangler R, Marshall D, et al. Allosteric inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like-2 impedes the development of a pathologic microenvironment. Nat. Med. 2010;16:1009–1017. doi: 10.1038/nm.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez HM, Vaysberg M, Mikels A, et al. Modulation of lysyl oxidase-like 2 enzymatic activity by an allosteric antibody inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:20964–20974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Payne SL, Fogelgren B, Hess AR, et al. Lysyl oxidase regulates breast cancer cell migration and adhesion through a hydrogen peroxide-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11429–11436. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bondareva A, Downey CM, Ayres F, et al. The lysyl oxidase inhibitor, beta-aminopropionitrile, diminishes the metastatic colonization potential of circulating breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X, Li S, Li W, et al. Inactivation of lysyl oxidase by β-aminopropionitrile inhibits hypoxia-induced invasion and migration of cervical cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2013;29:541–548. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shih YH, Chang KW, Chen MY, et al. Lysyl oxidase and enhancement of cell proliferation and angiogenesis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2013;35:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hed.22959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Zhang Y, Tan Z, et al. Lysyl oxidase promotes anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell proliferation and metastasis mediated via BMP1. Gland Surg. 2022;11:245–257. doi: 10.21037/gs-21-908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Q, Zhu CC, Ni B, et al. Lysyl oxidase promotes liver metastasis of gastric cancer via facilitating the reciprocal interactions between tumor cells and cancer associated fibroblasts. EBioMedicine. 2019;49:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang M, Liu J, Wang F, et al. Lysyl oxidase assists tumor- initiating cells to enhance angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2019;54:1398–1408. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.LoRusso P, Hecht JR, Thai DL, et al. Phase I and IIa studies of simtuzumab alone and in combination with FOLFIRI in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:554. 554. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raghu G, Brown KK, Collard HR, et al. Efficacy of simtuzumab versus placebo in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a randomised, double-blind, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017;5:22–32. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benson AB, 3rd, Wainberg ZA, Hecht JR, et al. A phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of simtuzumab or placebo in combination with gemcitabine for the first-line treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2017;22:241. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0024. e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muir AJ, Levy C, Janssen HLA, et al. Simtuzumab for primary sclerosing cholangitis: phase 2 study results with insights on the natural history of the disease. Hepatology. 2019;69:684–698. doi: 10.1002/hep.30237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrison SA, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, et al. Simtuzumab is ineffective for patients with bridging fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis caused by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1140–1153. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang J, Lucas MC, Leonte LE, et al. Pre-clinical evaluation of small molecule LOXL2 inhibitors in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:26066–26078. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Findlay AD, Foot JS, Buson A, et al. Identification and optimization of mechanism-based fluoroallylamine inhibitors of lysyl oxidase-like 2/3. J. Med. Chem. 2019;62:9874–9889. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.