Abstract

A single intracellular carbonic anhydrase (CA) was detected in air-grown and, at reduced levels, in high CO2-grown cells of the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum (UTEX 642). No external CA activity was detected irrespective of growth CO2 conditions. Ethoxyzolamide (0.4 mm), a CA-specific inhibitor, severely inhibited high-affinity photosynthesis at low concentrations of dissolved inorganic carbon, whereas 2 mm acetazolamide had little effect on the affinity for dissolved inorganic carbon, suggesting that internal CA is crucial for the operation of a carbon concentrating mechanism in P. tricornutum. Internal CA was purified 36.7-fold of that of cell homogenates by ammonium sulfate precipitation, and two-step column chromatography on diethylaminoethyl-sephacel and p-aminomethylbenzene sulfone amide agarose. The purified CA was shown, by SDS-PAGE, to comprise an electrophoretically single polypeptide of 28 kD under both reduced and nonreduced conditions. The entire sequence of the cDNA of this CA was obtained by the rapid amplification of cDNA ends method and indicated that the cDNA encodes 282 amino acids. Comparison of this putative precursor sequence with the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified CA indicated that it included a possible signal sequence of up to 46 amino acids at the N terminus. The mature CA was found to consist of 236 amino acids and the sequence was homologous to β-type CAs. Even though the zinc-ligand amino acid residues were shown to be completely conserved, the amino acid residues that may constitute a CO2-binding site appeared to be unique among the β-CAs so far reported.

The aquatic environment is generally CO2 limiting for photoautotrophs mainly because of the limited capacity of water to hold gaseous CO2 and the slow diffusion rate of CO2(aq), which is about 10−4 times that in the atmosphere. It is well established that a number of algae and cyanobacteria actively take up and accumulate dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) intracellularly, which allows algal cells to photosynthesize efficiently even under atmospheric CO2. This DIC acquisition mechanism is termed a carbon concentrating mechanism (CCM) and a number of workers have suggested that carbonic anhydrase (CA) plays a key role in the CCM (Kaplan and Reinhold, 1999).

CA (EC 4.2.1.1) is a zinc-containing enzyme that catalyzes the reversible dehydration of HCO3− to CO2. This reaction is known to play important roles in various biological processes such as ion exchange, respiration, pH homeostasis, CO2 acquisition, and photosynthesis (Tashian, 1989; Badger and Price, 1994; Smith and Ferry, 2000, Moroney et al., 2001). CAs are widely distributed in living organisms and are categorized, on the basis of their amino acid sequence, into three distinct families designated as α-, β-, and γ-type (Hewett-Emmett and Tashian, 1996; Smith et al., 1999; Smith and Ferry, 2000), which do not share epitopes and are thought to have evolved independently (Smith et al., 1999). α-Type CA occurs in animals, eubacteria, green algae, and cyanobacteria (Smith et al., 1999) and is typified by mammalian forms and two periplasmic forms in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Hewett-Emmett and Tashian, 1996; Smith and Ferry, 2000). γ-Type CAs have been found in archaebacteria and eubacteria (Smith et al., 1999) and one has been purified from the methanogen Methanosarcina thermophilia (Alber and Ferry, 1994). A region of a gene for the cyanobacterial carboxysomal protein, ccmM is also known to be homologous to γ-type CAs (Price et al., 1993; Smith et al., 1999). Both α- and γ-type CAs have been shown to ligate with Zn by three His residues (Kisker et al., 1996).

β-Type CAs occur ubiquitously and have been separated into six phylogenetic clades (Smith and Ferry, 1999; Smith et al., 1999). β-CAs from monocots and dicots constitute independent groups. Another two clades are exclusively prokaryotic and the other two are composed of mixture of sequences from the eucarya to procarya domains, which include β-CAs from the green algae C. reinhardtii, and Coccomyxa sp., the red alga Porphyridium purpureum, and the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803 (Smith et al., 1999). A high consensus sequence among β-CAs, that is Cys-Xaan-His-Xaa2-Cys, is known to constitute the Zn coordination site (Hewett-Emmett and Tashian, 1996). X-ray crystallographic studies clarified the active site of β-CAs from pea (Pisum sativum; Kimber and Pai, 2000), the red algae P. purpureum (Mitsuhashi et al., 2000), Escherichia coli (Cronk et al., 2000), and Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (Strop et al., 2001). P. purpureum CA is thought to use an additional amino acid to constitute the Zn coordination site; Asp at two amino acids down toward the C-terminal end from the first Zn ligand, Cys, is also considered to ligate with Zn.

The intracellular location of CA seems to be a crucial factor for the operation of the CCM. One form of cyanobacterial β-CA is present in the carboxysome. Cells transformed to express human CAII in the cytoplasm resulted in a high CO2-requiring phenotype presumably due to stimulation of HCO3− dehydration in the cytoplasm and therefore an efflux of CO2 from the cells (Price and Badger, 1989). Inactivation of β-CA gene (icfA) was also found to induce a high-CO2-requiring phenotype (Fukuzawa et al., 1992). In eukaryotic algae, chloroplastic CAs are thought to be required to supply CO2 to Rubisco in the stroma and/or the pyrenoid where the predominant species of inorganic carbon is HCO3− because of the alkaline conditions of the stroma (Badger and Price, 1994). As a mechanism to enhance the rate of CO2 supply to Rubisco in C. reinhardtii, it has been suggested that α-type CA (Cah3) is associated with photosystem II at the lumenal side of the thylakoid membrane and catalyzes the dehydration of HCO3− in the lumen to give an ample efflux of CO2 to the stroma or the pyrenoid (Karlsson et al., 1998; Park et al., 1999, Moroney et al., 2001). These data clearly indicate that intracellular CA plays a key role in the CCM when it functions in particular cellular locations.

Diatoms are widespread in aquatic environments, and marine species are considered to be some of the most important CO2 fixers in the hydrosphere (Apt et al., 1996). Two strains of Phaeodactylum tricornutum have been documented to possess a CCM in that they can take up both CO2 and HCO3− actively (Colman and Rotatore, 1995; Johnston and Raven, 1996). John-McKay and Colman (1997) reported that all P. tricornutum strains they studied possessed internal CA but that some of them also possessed external CA. External CA in P. tricornutum was also shown to be essential for carbon acquisition under carbon-limited conditions (Iglesias-Rodriguez and Merrett, 1997). External CA therefore appears to operate to maintain equilibrium CO2 concentration in the periplasmic layer from HCO3−, predominant species of DIC in seawater. In contrast, the function of the internal form of CA in marine algae has not been studied extensively. Only one diatom CA has been isolated, that from the marine diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii (TWCA1; Roberts et al., 1997; Cox et al., 2000), and the structure of its Zn coordination site was determined by x-ray absorption spectrometry (Roberts et al., 1997; Cox et al., 2000). TWCA1 was shown to share no homology with other CAs but Zn coordination was made with three His ligands, which is a structure very similar to that of mammalian α-CAs (Roberts et al., 1997; Cox et al., 2000), suggesting a unique event of convergent molecular evolution. However, it is not clear whether or not the distinct structure of TWCA1 is common in the CAs of other diatom species.

Detailed molecular studies of CA from more marine diatom species is certainly needed because it is one of the critical enzymes for carbon acquisition in marine microalgae. In this study, internal CA of the marine diatom P. tricornutum was related to the operation of the CCM physiologically and characterized molecular biologically.

RESULTS

Effects of Sulfonamide on Photosynthetic Affinity for DIC

The effect of two specific inhibitors of CA, ethoxyzolamide (EZA) and acetazolamide (AZA), was used to determine the function of P. tricornutum CA in acquiring high-affinity photosynthesis (Table I). EZA is highly permeable to biological membranes and will inhibit both internal and external CA, whereas AZA is only weakly permeable and inhibits only external CA. EZA of 0.4 mm completely abolished high-affinity photosynthesis for DIC and DIC concentration at one-half-maximum rate of photosynthesis (K0.5[DIC]) was 454 μm (Table I), whereas either 0.4 or 2 mm AZA did not (Table I, K0.5[DIC] value of 29 and 44 μm, respectively). K0.5[DIC] value without the addition of sulfonamide was found to be 27 μm (Table I). Although the maximum rate of photosynthesis (Pmax) was suppressed both by EZA treatment by about 39% and by 0.4 and 2 mm AZA treatment to 65% to 70% that of the control (Table I), photosynthetic rates at limited DIC was much lower in EZA-treated cells than those in AZA-treated cells (data not shown). The absolute values of O2 evolution rate at 100 μm of DIC in the medium were 20.0, 18.0, 14.9, and 2.2 nmol mL−1 min−1 with control cells, cells treated with 0.4 and 2 mm AZA, and 0.4 mm EZA, respectively.

Table I.

Photosynthetic parametersa determined in air-grown P. tricornutum in the presence and the absence of sulfonamides at pH 8.2 and 25°C

| Treatment | K0.5[DIC] | Pmax |

|---|---|---|

| μM | μmol O2 mg−1 Chl h−1 | |

| Control | 27 ± 1 | 209 ± 15 |

| 2 mm AZA | 44 ± 9 | 147 ± 24 |

| 0.4 mm AZA | 29 ± 6 | 135 ± 30 |

| 0.4 mm EZA | 454 ± 87 | 81 ± 16 |

Values are the mean ± sd of three separate experiments.

Measurement of CA Activity in Intact Cell or Cell Lysate of P. tricornutum

No CA activity was detected in intact cells of P. tricornutum grown in either air or high CO2 (Table II). However, CA activity was detected in cell lysates: 26 ± 9.5 Wilbur-Anderson (WA) units mg−1 Chl were detected in high-CO2-grown cells, whereas 114 ± 38.7 WA units mg−1 Chl were found in air-grown cells (Table II). In a similar manner, strong CA activity was detected on cellulose acetate plates after electrophoresis of extracts from air-grown cells, whereas those from high-CO2-grown cells contained very weak activity at the same mobility on the plate as that from air-grown cells (Fig. 1). There were no isoforms detected on cellulose acetate plates (Fig. 1).

Table II.

CA activitya of whole cells and supernatant of whole cell extracts of air- and high-CO2-grown P. tricornutum

| Cells | Whole Cells | Supernatant of Extract |

|---|---|---|

| Air grown | N.D.b | 114 ± 39 |

| High CO2 grown | N.D. | 26 ± 9.5 |

(Tc/T − 1) mg−1 Chl. Values are the mean ± sd of five separate experiments.

N.D., Not detected.

Figure 1.

CA activity after cellulose acetate electrophoresis of cell-free extracts of P. tricornutum grown in 5% (w/v) CO2 and air. CA activity was visualized by soaking the plate in the pH-indicating dye, bromocresol purple, and exposing the plate to gaseous CO2.

Purification of CA

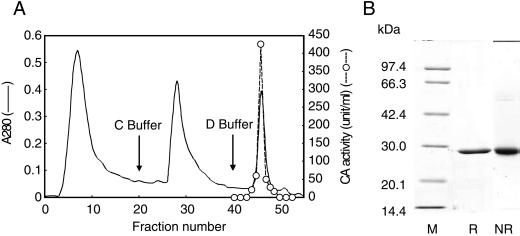

The purification procedure of P. tricornutum CA is summarized in Table III. By ammonium sulfate precipitation, about 42% of the activity of soluble CA was retrieved. The specific activity of CA at this stage was found to be 59 WA units mg−1 protein. Anion-exchange chromatography on a DEAE-sephacel column increased the specific activity up to 3-fold and CA was eluted at about 110 mm Na2SO4 (data not shown). The fraction with CA activity was then subjected to affinity chromatography on a p-aminomethylbenzene sulfone amide (p-AMBS) agarose column and was eluted as a single peak by 25 mm Tris-H2SO4 (pH 8.5) containing 0.3 m NaClO4 (Fig. 2A). This step improved the specific activity about 7.6-fold and the specific activity of CA was found to be 1,114 WA units mg−1 protein. CA was purified to 36.7-fold from the homogenate (Table III).

Table III.

Summary of purification procedure of CA from P. tricornutum

| Fraction | Total Protein | Total CA Activity | Specific Activity | Purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg | WAUa | WAUa mg−1 protein | fold | |

| Homogenate | 197.9 | 6,175 | 31 | 1.0 |

| (NH4)2SO4 | 44.4 | 2,617 | 59 | 1.9 |

| DEAE-sephacel | 8.9 | 1,444 | 163 | 5.2 |

| p-AMBS-agarose | 0.37 | 423 | 1,144 | 36.7 |

WA unit; Tc/T − 1.

Figure 2.

Purification of P. tricornutum CA on a p-AMBS agarose column (A) and subsequent SDS-PAGE analysis (B). A, The column (2 mL of bed volume) was pre-equilibrated with 50 mm Bicine-NaOH (pH 8.3) and washed with 25 mm Tris-H2SO4 containing 0.1 m Na2SO4. CA was eluted with 25 mm Tris-H2SO4 containing 0.3 m NaClO4 with the flow rate at 0.2 mL min−1. B, Molecular mass markers (lane M) and 10 μg of protein from the peak fraction (no. 46) was applied to 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel. CA was treated with 0.5% (w/v) SDS in the presence (lane R) and absence (lane NR) of 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol prior to the electrophoresis.

The purified CA gave a single band on SDS-PAGE under both reducing and nonreducing conditions, confirming uniformity of this protein (Fig. 2B). Treatment with the reducing agent did not cause any shift in the mobility of the band and the molecular mass estimated by SDS-PAGE was 28 kD (Fig. 2B). AZA concentration at one-half-maximum inhibition (I50[AZA]) of P. tricornutum CA was found to be 5 × 10−8 M.

Molecular Cloning of Full-Length cDNA and Determination of Nucleotide Sequence

The protein sequence of 50 amino acid residues from the N terminus of the purified CA revealed that this CA may be homologous to β-type CAs, which prompted us to clone the CA gene of P. tricornutum with the aid of the published sequences of β-type CAs (Mitsuhashi and Miyachi, 1996; Hiltonen et al., 1998). The first PCR gave a mixture of hetero-sized products ranging from 50 to 2,000 bp (data not shown). The second PCR gave several sizes of products but the major one corresponded in size to approximately 250 bp (data not shown). This 250-bp fragment was cloned into the plasmid vector and was sequenced. The deduced amino acid sequence of the 250-bp fragment included a part of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of purified P. tricornutum CA (data not shown).

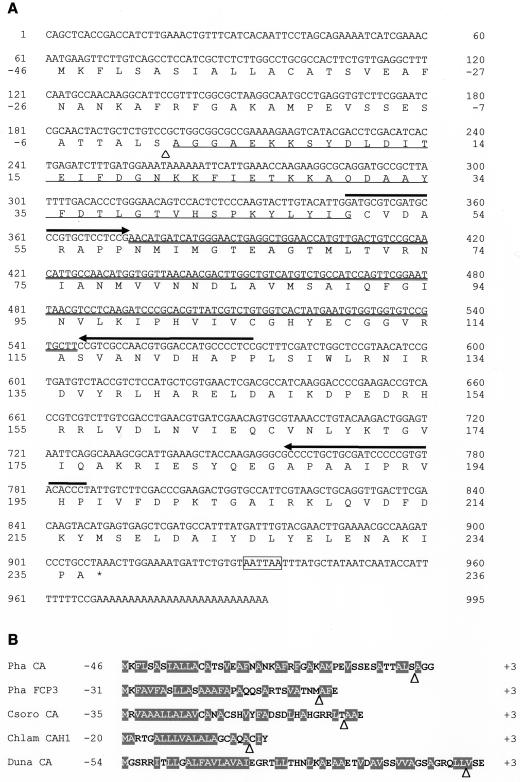

Utilizing the 250-bp fragment as a “core” sequence, the full-length cDNA sequence was determined by a RACE method with high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Fig. 3A). The full-length cDNA of P. tricornutum CA was 995 bp and was shown to comprise 61 bp of a 5′-untranslated region, 846 bp of an open reading frame, a termination codon, 58 bp of a 3′-untranslated region, and 27 bp of poly(A+) tail (Fig. 3A). The open reading frame (Fig. 3A, 62–907) encodes a polypeptide of 282 amino acids (Fig. 3A, −46–236), whereas the N-terminal amino acid sequence of purified CA started at Ala 46 amino acids down toward C terminus from the initial Met (Fig. 3A). These data indicate that the mature CA in P. tricornutum can be categorized as a β-type and is composed of 236 amino acids (Fig. 3A, +1–236) whose molecular mass was calculated to be 26,354 D. The 46 amino acids at the upstream of N terminus of mature CA appear to be a signal sequence (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Sequences of cDNA and deduced amino acids of P. tricornutum CA (A) and a comparison of N-terminal sequence with those of some algal proteins (B). A, The amino acid sequence is numbered from the N terminus of the mature protein. The putative cleavage site of signal peptide is indicated by a white triangle. The single-underlined region was initially sequenced at protein bases upon purification of P. tricornutum CA. Double underline indicates an overlapped sequence between the 5′-RACE and the 3′-RACE products. Arrows indicate primers used for the RACE. The termination codon and the putative polyadenylation signal are indicated by an asterisk and a box, respectively. B, Forty-six amino acids of the N terminus of P. tricornutum CA (Pha CA) were compared with fucoxanthin chlorophyll protein 3 of P. tricornutum (Pha FCP3), internal CA of Chlorella sorokiniana (Csoro CA), periplasmic CA, CAH1, of C. reinhardtii (Chlam CAH1), and plasma membrane CA of Dunaliella salina (Duna CA). Hydrophobic amino acid residues are indicated by white letters on a gray background. The white triangles indicate putative cleavage sites of signal peptides.

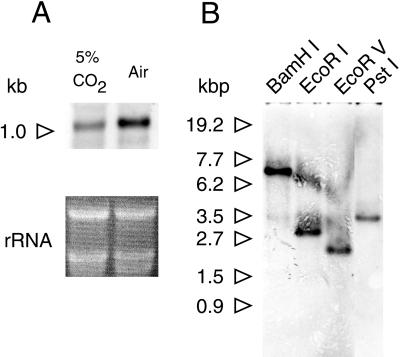

RNA and Genomic DNA Gel-Blot Analysis

The size of CA mRNA was found to be 1.0 kb by RNA gel-blot analysis (Fig. 4A), which agreed well with the size of CA cDNA (995 bp). The same hybridization signal was clearly detected for transcripts from high-CO2-grown cells, but its intensity was significantly lower than that of air-grown cells (Fig. 4A). The number of CA genes in the genome was estimated by Southern-blot analysis (Fig. 4B). CA cDNA did not possess any recognition sites for any of the four restriction enzymes used. The 5′-RACE product of CA cDNA (1–574) was prepared as a probe. One or two hybridization bands with different mobilities were detected in the four digests; one band was observed in BamHI, EcoRV, and PstI digest, whereas two bands were observed in EcoRI digest (Fig. 4B), suggesting the presence of at least one intron that contains an EcoRI site.

Figure 4.

RNA (A) and DNA (B) gel-blot analyses of cloned CA. A, Total RNA (15 μg) obtained from P. tricornutum grown in 5% (v/v) CO2 and air was separated on 1.0% (w/v) agarose gel, blotted onto nylon membrane, and hybridized with the 5′-RACE product of CA labeled by alkaline-phosphatase. Hybridization signal was visualized by fluorography using CDPstar (top half). Quantities of RNAs were normalized with rRNA (bottom half). The molecular size corresponds to 1.0 kb and is indicated by a white arrow. B, Ten micrograms of genomic DNA was digested independently with four restriction enzymes, BamHI, EcoRI, EcoRV, and PstI, and was separated by 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel, blotted onto nylon membrane, and hybridized with the CA probe described above. Hybridization signal was visualized as described above. The molecular sizes are indicated by white arrows.

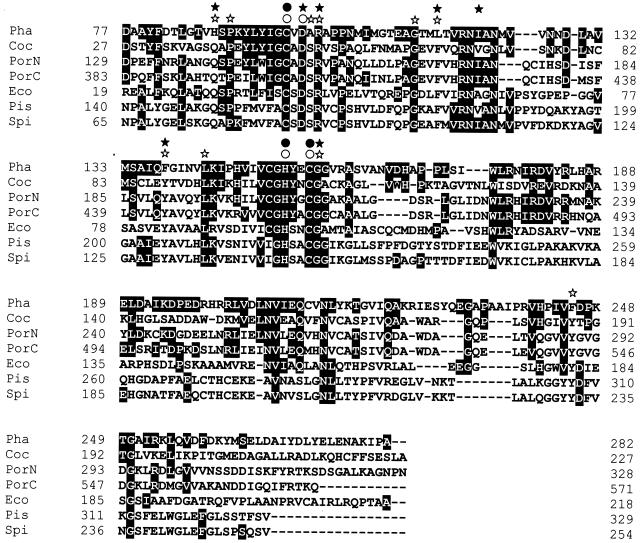

Comparison of Deduced Amino Acid Sequence of P. tricornutum CA with CAs in Other Species

The sequence similarity analysis of P. tricornutum CA was carried out with the DNA Data Bank of Japan homology search system. Eight sequences that were moderately homologous to P. tricornutum CA were retrieved, namely CA in Coccomyxa sp. (Hiltonen et al., 1998), N and C halves of CA1 in P. purpureum (Mitsuhashi and Miyachi, 1996), CynT product in E. coli (Guilloton et al., 1992), and CAs in pea (Majeau and Coleman, 1991), Spinacea oleracea (Burnell et al., 1989), M. thermoautotrophicum (Smith and Ferry, 1999), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The identities of the amino acid were 25.9% (Coccomyxa sp.), 20.0% (P. purpureum), 26.2% (E. coli), 20.1% (pea), 25.5% (S. oleracea), 20.9% (M. thermoautotrophicum), and 22.3% (S. cerevisiae), respectively (Fig. 5). These sequences are aligned at their maximum match in Figure 5 and amino acid residues that have been shown either to constitute Zn ligands or to orient toward Zn (Kimber and Pai, 2000; Mitsuhashi et al., 2000) are indicated by circles and asterisks, respectively. Given the alignment, Zn-binding residues were found to be highly conserved, whereas amino acids possibly related to the catalytic site (Kimber and Pai, 2000; Mitsuhashi et al., 2000) appeared to be different in P. tricornutum CA (Fig. 5). The amino acid, Leu70, does not correspond to any other known β-CAs and Phe92 does not correspond to β-CAs of either algal or higher plant origin but it corresponds to that in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of sequences of β-CAs from several different origins. β-CA of P. tricornutum (Pha) was compared with that of Coccomyxa sp. (Coc; accession no. U49976), N and C half of P. purpureum β-CA (PorN and PorC, respectively; accession no. D86050), E. coli Cyn T product (Eco; accession no. M23219), chloroplastic β-CA of pea, (Pis; accession no. M63627), chloroplastic β-CA of S. oleracea (Spi; accession no. M27295), β-CA of S. cerevisiae (Sac; accession no. Z71312), and β-CA of M. thermoautotrophicum (Met; accession no. AE000918). The row of Pha is numbered from the N terminus amino acid sequence of the putative β-CA precursor deduced from the full-length cDNA. Sequences were aligned with CLUSTAL W at their maximum match and the amino acids identical with those of P. tricornutum CA are shown as white letters on black background. Circles and asterisks indicate putative zinc-ligand residues and residues orient toward Zn, respectively. White and black symbols are marked to the alignment based upon the information from the x-ray crystallographic analyses of P. purpureum CA and pea CA, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The marine environment differs from that of freshwater primarily in salinity and alkalinity, which creates distinct DIC equilibria in seawater (Goyet and Poisson, 1989) and stable pH at slightly above 8.0. The DIC equilibrium at this pH gives rise to a low CO2 concentration that may cause CO2 limitation to photoautotrophs. However, it has been shown in most of the marine microalgae so far investigated that under light-saturating conditions, photosynthesis is saturated at air equilibrium CO2 concentrations, presumably due to an efficient use of HCO3−, which is abundant in seawater (Raven, 1997; Tortell et al., 1997). The occurrence of direct HCO3− uptake has been shown in various marine microalgae (Burns and Beardall, 1987; Colman and Rotatore, 1995; Nimer et al., 1997, Raven, 1997). The data obtained in the present study also showed that photosynthetic O2 evolution rate at limited [DIC] greatly exceeded the actual CO2 formation rate in the bulk medium, strongly suggesting a direct uptake of HCO3−; irrespective of the presence of AZA, O2 evolution rate at 100 μm DIC was about 15 to 20 nmol mL−1 min−1, which is about 30-fold the un-catalyzed rate of CO2 formation (Matsuda et al., 2001) in artificial seawater enriched with one-half-strength of Guillard's “F” solution (f/2; F2AW; Harrison et al., 1980) at pH 8.2. An HCO3−-dependent photosynthesis was also observed in another strain of P. tricornutum (UTEX640; Matsuda et al., 2001).

As an alternative mechanism for HCO3− use from the bulk medium, CA, located in the periplasmic space, has been shown to facilitate an indirect use of HCO3− by catalyzing CO2 formation close to the plasmalemma. This external CA has been shown to occur both in marine algae (including P. tricornutum) and in freshwater algae (Aizawa and Miyachi, 1986; Williams and Colman, 1993; Iglesias-Rodriguez et al., 1997; Nimer et al., 1999). However, recent studies have shown that external CA is not necessarily essential for growth under CO2 limitation in C. reinhardtii (Moroney and Somanchi, 1999; Van and Spalding 1999) but rather that internal CA activity may be crucial under these conditions (Funke et al., 1997). P. tricornutum UTEX642 was previously shown to lack external CA (John-Mckay and Colman, 1997). In the present study, no external CA activity was detected either in air- or high-CO2-grown cells of P. tricornutum. This was confirmed further by sulfonamide inhibition experiments in which up to 2 mm AZA did not lower the photosynthetic affinity for DIC (Table I). A single major band of CA activity, detected on cellulose acetate plates after electrophoresis of lysates of both air- and high-CO2-grown cells (Fig. 1), thus appeared to be an intracellular form of CA, which is encoded by a single gene, and no other isoform was detected (Fig. 1) in this study. However, these data do not exclude the possibility of the occurrence of trace levels of other CA isoforms that may also have a role in the CCM in P. tricornutum.

The function of internal CA in the CCM of marine microalgae is largely unknown. The data in the present study demonstrate that EZA drastically inhibited high-affinity photosynthesis repeat and confirm the results of previous studies on P. tricornutum (Badger et al., 1998). Because EZA is also believed to possess direct inhibitory effects on photosystem II and DIC uptake (Badger et al., 1998), the reason for the EZA inhibition of high-photosynthetic affinity for DIC is not clear at present. Nevertheless, it has been shown in most of the freshwater algae studied that CA plays a crucial role in the operation of the CCM and this may hold true also in the case of marine diatoms. In the present study, EZA reduced Pmax to about 40% that of the control and a similar, but weaker effect was also observed by prolonged treatment with high concentrations of AZA, presumably due to permeation of AZA at trace concentration into the cells. Therefore, it is plausible that internal CA may also take part in supplying CO2 to photosynthesis and determine the Pmax in P. tricornutum. EZA treatment of the green alga Chlorella ellipsoidea also lowered the cells' affinity for DIC to the level that resembled that of high-CO2-grown cells, but Pmax was not affected by EZA (Y. Matsuda, unpublished data).

Internal CA detected in this study is clearly a low-CO2-inducible protein and this regulation occurs at the transcriptional level even though there was a constitutive level of accumulation of transcript observed in high-CO2-grown cells. The photosynthetic affinity of P. tricornutum cells for DIC appeared to increase concomitant with internal CA activity (data not shown). However, it has been indicated that the regulation of CA expression in response to CO2 is not necessarily related to the CCM. The thylakoid-lumenal form of CA, Cah3, in C. reinhardtii appeared to be expressed semiconstitutively despite changes in the ambient [CO2], whereas the expression of the periplasmic CAs, Cah1 and Cah2, and the mitochondrial CAs, β-CA1 and β-CA2, which are possibly less crucial isoforms with respect to the operation of the CCM, have been shown to be highly dependent on changes in the ambient [CO2] (Moroney and Chen, 1998). The regulation mechanism of internal CA expression in response to CO2 is yet to be studied and to be related functionally with CCM in P. tricornutum.

P. tricornutum CA was purified effectively by anion-exchange chromatography on DEAE-sephacel and on p-AMBS, an affinity column with a sulfonamide ligand. CA from P. tricornutum was eluted from the p-AMBS column with 0.3 m NaClO4 (Fig. 1), which is a lower concentration than that used for the α-type CAs in C. sorokiniana (Satoh et al., 1998) and C. reinhardtii (Yang et al., 1985; Rawat and Moroney, 1991). It should be noted that the affinity of P. tricornutum CA for sulfonamides might be lower than those in known α-CAs but higher than that of β-CA isolated from microalgae, i.e. AZA concentration at one-half-maximum inhibition (I50[AZA]) of P. tricornutum. CA was found to be about seven and 17 times higher than those observed in α-CA from C. sorokiniana (Satoh et al., 1998) and C. reinhardtii CAH1 and 2 (Tachiki et al., 1992), respectively, but 20 times lower than that of Coccomyxa β-CA (Hiltonen et al., 1995).

The primary structure of P. tricornutum CA shows that it can be classified as a β-type CA and is homologous to β-CAs in other algae and higher plants (Figs. 3A and 5). The molecular mass of P. tricornutum CA was estimated to be 28 kD by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2B), whereas it is calculated to be 26.4 kD from the primary structure of the mature protein (Fig. 3A). This difference in molecular mass of approximately 2 kD may indicate the possible occurrence of posttranslational modification such as glycosylation, but a potential attachment site for an N-linked carbohydrate chain (Asn-Xaa-Ser/Thr) was not found in the polypeptide sequence.

Although the subcellular location of P. tricornutum CA is not known, this enzyme is soluble and therefore seems to be located in the hydrophilic matrix of the cell and not in the membranes. This is in contrast to the internal CAs in C. reinhardtii of which about 95% of the total CA is insoluble (Funke et al., 1997) and one isoform, Cah3, was postulated to function in the CCM as a thylakoid membrane-associated form (Raven, 1997; Karlsson et al., 1998; Park et al., 1999). In contrast, the predominant form of internal CA in Chlorella spp. was shown to be soluble when the cells have an operational CCM (Williams and Colman, 1993; Satoh et al., 1998). The amino acid sequence of P. tricornutum CA may give some indication of its intracellular location. The N-terminal region, from the first Met to Ser (Fig. 3A, −46 to −1) shows the typical features of a signal sequence (von Heijne, 1983) which includes several hydrophobic core residues in the N termini,: the residues at the position −1 and −3 are small, and the position at −2 is bulky. This region has similarities to the signal peptide of the fucoxanthin-chlorophyll a/c proteins (FCPs) in P. tricornutum (Grossman et al., 1990), C. reinhardtii CAH1 (Fukuzawa et al., 1990), C. sorokiniana CA (Satoh et al., 1998), and the plasma membrane CA in D. salina (Fisher et al., 1996; Fig. 3B). This region was also predicted to be a signal for import to the endoplasmic reticulum by analysis with TargetP, which is a neural network algorithms (Emanuelsson et al., 2000) and several other analyses for predicting protein-targeting sites. It has been shown in P. tricornutum that three proteins in the fucoxanthin-chlorophyll a/c complex associated with photosystem II are encoded by the nuclear genome and have the endoplasmic reticulum signal peptide (Grossman et al., 1990). Bhaya and Grossman (1991) further suggested that some of the cytoplasmically synthesized proteins of P. tricornutum required an endoplasmic reticulum signal to be directed to the plastids because the signal peptide of FCP3, one of the FCPs, can be cotranslationally processed and transported into microsomes in vitro. This suggests that P. tricornutum CA could be located in organelles. The intracellular location of P. tricornutum CA needs to be determined cytochemically and physiologically to investigate its biochemical and cell structural organization when CA functions in relation to carbon acquisition in marine autotrophs.

The tertiary structures of β-type CAs have been determined by x-ray crystallography using enzymes obtained from the unicellular red algae, P. purpureum (Mitsuhashi et al., 2000), the pea plant (Kimber and Pai, 2000), and M. thermoautotrophicum (Strop et al., 2001). It is interesting that despite the striking similarity in the primary structures of the active site, their tertiary structures and proposed mechanisms of catalysis were quite different among these β-CAs. The subunit of P. purpureum CA was shown to be divided into two almost identical parts, i.e. N and C halves that revealed the typical primary structure of β-CA (Mitsuhashi et al., 2000). Each one-half contained a Zn coordination site constituted of four amino acid residues, Cys, Asp, His, and Cys, which forms an active center with a hydrophobic domain primarily composed of Pro, Phe, and Leu in the other one-half chain (Mitsuhashi et al., 2000). Binding of Zn by four amino acid ligands, including that of Asp, and a cooperative conformation to utilize trans-located subdomains are a unique feature of the active center of CA and hence the CO2 hydration mechanism is thought to use water, which does not bind to Zn directly (Mitsuhashi et al., 2000). In contrast to this unique structure of red algal β-CA, pea CA was shown to possess an active site that is a mirror image of that of α-CA and thus is assumed to share a similar mechanism of catalysis to α-CAs (Kimber and Pai, 2000).

The tertiary structure of P. purpureum β-CA was shown to be unique as described above and hence might not occur in P. tricornutum β-CA (Fig. 5). If the catalysis mechanism of P. tricornutum CA resembles that of α-CA as in the case of pea CA, the critical amino acid residues involved in the CO2 hydration may be quite different from that of pea. The residues His42, Leu70, and Phe92, which correspond to Gln151, Phe179, and Tyr205 in pea CA, may form a CO2-binding site, and the proton of the imidazole group in His42 would interact with the oxygen of CO2 in place of the amide group in Gln151 in pea CA (Kimber and Pai, 2000).

The subunit structure of β-CAs varies depending on species. Higher plant β-CA possess hexa- to octameric structures (Sültemeyer et al., 1993; Kimber and Pai, 2000) whereas those in Monera and Protista have been shown to possess di- to tetrameric structures (Hiltonen et al., 1998; Mitsuhashi et al., 2000). The molecular mass of the native form of P. tricornutum CA could not be determined by gel filtration because no distinct sharp peak was detected and the CA was distributed in a broad range of fractions that correspond to the molecular mass of 800 to 29 kD (data not shown). This result was always obtained with different batches of preparations (data not shown), suggesting that the quaternary structure of this enzyme may be very large and be disassembled during purification or by interaction with the matrix of the column. In an alternate manner, monomeric polypeptides might merely aggregate to form a large pseudo complex in vitro.

Intracellular CA appears to play a major role in acquiring and supplying substrate for photosynthesis in marine diatoms. The P. tricornutum CA described in this study is the first β-CA to be detected in a diatom species. The other diatom CA so far isolated is from T. weissflogii (TWCA1), which showed no homology to the known algal CAs and therefore a fundamental difference of carbon acquisition among algal phyla was proposed by the authors (Roberts et al., 1997). In contrast, the present study indicates that the primary structure of CA in a diatom is not markedly distinctive as far as one of the major neritic species, P. tricornutum, is concerned.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Culture Condition

The marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum (UTEX 642) was obtained from the University of Texas Culture Collection (Austin) and was cultured axenically in F2AW (Harrison et al., 1980) under continuous illumination of photon flux density of 100 μmol m−2 s−1 at 20°C. The culture was aerated with 5% CO2 (high-CO2-grown cells) or air (air-grown cells).

Determination of Photosynthetic Affinity for DIC

Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1,500g for 10 min at 25°C, washed twice with 350 μm NaCl buffered with 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH6.8), and resuspended in CO2-free F2AW buffered with 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.2) under N2 at a chlorophyll a concentration of 10 μg mL−1. The rate of photosynthesis was measured with a Clark-type oxygen electrode as described previously (Matsuda and Colman, 1995) with or without the addition of CA inhibitors, EZA (0.4 mm; Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo) or AZA (0.4 or 2 mm; Sigma-Aldrich Japan). The apparent K0.5[DIC] was determined as described by Rotatore and Colman (1991). Cell suspension (1.5 mL) was placed in the O2 electrode chamber, illuminated with a fiber optic illuminator (Megalight100, Hoya-Schott Co., Tokyo) at a photon flux density of 2,600 μmol m−2 s−1 and the cells allowed to reach CO2 compensation concentration. The photon flux density was then increased to 6,400 μmol m−2 s−1 and aliquots of KHCO3 were added sequentially to the cell suspension to create increasing DIC concentrations. Chlorophyll a concentration was determined by the spectrophotometric method described by Jeffrey and Humphrey (1975).

Measurement of CA Activity

CA activity was measured by the potentiometric method described by Wilbur and Anderson (1948) with some modifications. Twenty microliters of enzyme solution or cell suspension was added to 1.48 mL of 20 mm Veronal buffer (pH 8.3) in a water-jacketed acrylic chamber maintained at 4°C. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 0.5 mL of ice-cold CO2-saturated water and the time required for the pH to drop from 8.3 to 8.0 was determined. The WA unit was defined as follows: WA unit = Tc/T − 1, where Tc and T are the time required for the pH drop in the absence and presence of enzyme solution, respectively. For the qualitative determination of CA activity, electrophoresis on cellulose acetate plates (Titan III Zip Zone, Helena Laboratories, Mississauga, Canada) was carried out as described by Williams and Colman (1993).

Extraction and Purification of CA

A culture of air-grown cells (20 L) at mid-logarithmic phase (OD730 0.2–0.4) was harvested by centrifugation at 1,500g for 10 min at 25°C. The cells were resuspended in a minimum volume of 50 mm Bicine (N, N-Bis 2-hydroxymethyl Gly)-NaOH buffer (pH 8.5) and then mixed with 400 g of glass beads (0.105–0.125 mm: 0.177–0.250 mm: 0.350–0.500 mm = 1: 1: 2, Iuchi Seieido, Osaka). Cells were homogenized by vigorous vortexing for 1 min and chilled on ice for 5 min. This procedure was repeated 15 times. A cell-free lysate was obtained from the homogenate by centrifugation at 26,000g for 60 min at 4°C. CA activity was recovered from the resulting supernatant by ammonium sulfate precipitation between 30% and 65% saturation. This CA fraction was subjected to a two-step purification using a DEAE-sephacel (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK) column (i.d. 1.0 × 6.3 cm) followed by affinity chromatography on a p-AMBS agarose (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis) column (i.d. 0.8 × 4 cm). The DEAE-Sephacel column was equilibrated with 50 mm Bicine-NaOH (pH 7.9) and protein was eluted with a linear gradient of Na2SO4 from 0 to 0.25 m. p-AMBS column was equilibrated by 50 mm Bicine-NaOH (pH 8.3) and protein was eluted with 25 mm Tris-H2SO4 buffer containing 0.1 m Na2SO4 and the same buffer containing 0.3 m NaClO4. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Determination of Molecular Mass

The CA fraction eluted from the p-AMBS agarose column was applied to SDS-PAGE under both nonreducing and reducing conditions with 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol using a 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel and molecular-mass standards (DAIICHI III, Daiichi Pure Chemicals, Co., Ltd., Tokyo). The molecular mass of CA was also determined by molecular sieving on a Superdex 200 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) column (i.d. 1.0 × 30 cm).

Determination of Amino Acid Sequence of N-Terminal End

CA was blotted electrophoretically onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon, Millipore, Bedford, MA) followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. The CA band was cut out of the membrane and subjected to amino acid sequencing analysis of the N-terminal end using PPSQ-23 (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto).

Extraction of Total RNA and Molecular Cloning of CA cDNA

Air-grown cells (3.0 L) at late logarithmic phase (OD730 = 0.4) were harvested as described above. The cells were frozen immediately, disrupted in liquid N2, and total RNA was extracted as described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (1987). cDNA was synthesized with M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (New England Bio Labs Inc., Beverly, MA) and oligo (dT)15 primer.

Degenerate primers were designed according to the amino acid sequence of the N-terminal end of the purified CA (PtCAF1: 5′-CGC GGA TCC GAY ATI ACI GAR ATH TTY GAY GG-3′) and according to two published nucleotide sequences of β-CAs from Coccomyxa sp. (Hiltonen et al., 1998) and P. purpreum (Mitsuhashi and Miyachi, 1996; PtCAR1: 5′-CCG GAA TTC CCA TNG CNK CYT GIA CHA T-3′), which corresponded to the sequences of DITEIFDG and IVQ(A/D) AW(A/D), respectively. A partial nucleotide sequence of CA cDNA was amplified by PCR, on the assumption that P. tricornutum CA is homologous to β-CAs. The PCR profile was as follows: five cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s. The resulting PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and the bands corresponding in size to approximately 400 to 600 bp were cut out of the gel and the extract was used as a template for a second PCR. The nested-degenerate primers were designed according to the amino acid sequence of the N-terminal end of purified CA (PtCAF2: 5′-CCG GAA TTC GAY GCI GCN TAY TTY GAY AC-3′) and according to the two published nucleotide sequences of β-CAs described above (PtCAR2: 5′-CCG GAA TTC TAR TGI CCR CAN ACI ARD ATR TG-3′), which corresponded to the sequences of DAAYFDT and HILVCGH, respectively. The PCR profile was as follows: three cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 53°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s, followed by 37 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s. The amplified fragment was purified by electrophoresis and cloned into a plasmid vector (pT7Blue T-Vector, Novagen, Madison, WI). Cloned cDNA was sequenced by using Thermo Sequenase Cycle sequence Kit and Cy5.5 labeled primers by the Long-Read Tower System (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

A full-length sequence of CA cDNA was determined by RACE method for the 5′ and 3′ ends of CA cDNA. SMART RACE cDNA Amplification Kit and high-fidelity DNA polymerase (CLONTECH Laboratories Inc., Palo Alto, CA) were used according to the manufacturer's protocols. CA gene-specific primers, PtCASP1: 5′-GGA TGC GTC GAT GCC CGT GCT CCT CCG-3′, were designed based upon the partial nucleotide sequence of CA cDNA. The 3′-RACE was carried out with PtCASP1 and the universal primer provided by manufacturer. The resulted PCR product was cloned into the plasmid vector and sequenced.

CA gene-specific primers, PtCASP2: 5′-GGT GAC ACG GGG ATC GCA GCA GGG GCG-3′ and PtCASP3: 5′-GGA GGG GCA TGG TCC ACG TTG GCG ACG G-3′, were designed according to the cDNA sequence of 3′ region determined by 3′-RACE. The 5′-RACE was carried out with PtCASP2 and the universal primer provided by manufacturer. The second PCR was carried out with PtCASP3 and the universal primer provided by manufacturer as described above on the product of first PCR and the resulted PCR product was cloned into a plasmid vector and sequenced. The sequence data was analyzed by the GENETYX System (Software development Co., Ltd., Tokyo). A homology search was carried out using the DNA Data Bank of Japan homology search system (release 42, July 2000) and the deduced amino acid sequence of P. tricornutum CA was compared with several known CA sequences (Burnell et al., 1989; Majeau and Coleman, 1991; Guilloton et al., 1992; Mitsuhashi and Miyachi, 1996; Hiltonen et al., 1998; Smith and Ferry, 1999).

RNA Gel-Blot Analysis

Total RNA (15 μg) from 5% (v/v) CO2- and air-grown cells at mid-logarithmic phase was separated by 1.1% (v/v) formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis and blotted onto nylon membrane (Hybond N+, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The membrane was hybridized with the PCR product of 5′-RACE described above. The labeling of the probe and hybridization were carried out using Gene Images random prime labeling module (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Hybridized probe was reacted with CDPstar (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and visualized by fluorography.

Genomic DNA Gel-Blot Analysis

Two liters of high-CO2-grown cells (OD730 = 0.625) was harvested, frozen, and disrupted in liquid N2. The homogenate was resuspended in 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.1 m EDTA, and 0.5% (w/v) sarcosyl and was treated with 40 μg mL−1 RNaseA (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 2 h followed by treatment with 80 μg mL−1 proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich) at 50°C for 2 h. Protein was removed with dialysis method as described by Sambrook et al. (1989). Twelve micrograms of genomic DNA was digested separately with BamHI (Roche Diagnostics, Basel), EcoRI, EcoRV (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Otsu, Japan), or PstI (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka) and subjected to DNA gel-blot analysis. Probe preparation and visualization of hybridized band were carried out as described in RNA gel-blot analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Mr. Goro Hirozumi for his technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by a grant from Invitation for Research Institute of Innovative Technology for the Earth Research Proposals and in part by Kwansei-Gakuin University (Special Grant for Individual Researcher to Y.M. and a visiting professorship to B.C.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Aizawa K, Miyachi S. Carbonic anhydrase and CO2 concentrating mechanisms in microalgae and cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1986;39:215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Alber BE, Ferry JG. A carbonic anhydrase from the archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6909–6913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apt KE, Kroth-Pancic PG, Grossman AR. Stable nuclear transformation of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:572–579. doi: 10.1007/BF02172403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Andrews TJ, Whitney SM, Ludwig M, Yellowlees DC, Leggat W, Price GD. The diversity and coevolution of Rubisco, plastids, pyrenoids, and chloroplast-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in algae. Can J Bot. 1998;76:1052–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. The role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1994;45:369–392. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaya D, Grossman A. Targeting proteins to diatom plastids involves transport through an endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;229:400–404. doi: 10.1007/BF00267462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnell JN, Gibbs MJ, Mason JG. Spinach chloroplastic carbonic anhydrase: nucleotide sequence analysis of cDNA. Plant Physiol. 1989;92:37–40. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns BD, Beardall J. Utilization of inorganic carbon by microalgae. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1987;107:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate- phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman B, Rotatore C. Photosynthetic inorganic carbon uptake and accumulation in two marine diatoms. Plant Cell Environ. 1995;18:919–924. [Google Scholar]

- Cox EH, McLendon GL, Morel FMM, Lane TW, Prince RC, Pickering IJ, George GN. The active site structure of Thalassiosira weissflogii carbonic anhydrase 1. Biochem. 2000;39:12128–12130. doi: 10.1021/bi001416s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronk JD, O'Neill JW, Cronk MR, Endrizzi JA, Zhang KYJ. Cloning, crystallization and preliminary characterization of a β-carbonic anhydrase from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystal D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:1176–1179. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900008519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N- terminal amino acid sequence. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:1005–1016. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Gokhman I, Pick U, Zamir A. A salt-resistant plasma membrane carbonic anhydrase is induced by salt in Dunaliella salina. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17718–17723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa H, Fujiwara S, Yamamoto Y, Dionisio-Sese ML, Miyachi S. cDNA cloning, sequence, and expression of carbonic anhydrase in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: regulation by environmental CO2 concentration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4383–4387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa H, Suzuki E, Komukai Y, Miyachi S. A gene homologous to chloroplast carbonic anhydrase (icfA) is essential to photosynthetic carbon dioxide fixation by Synechococcus PCC7942. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4437–4441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke RP, Kovar JL, Weeks DP. Intracellular carbonic anhydrase is essential to photosynthesis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii at atmospheric levels of CO2. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:237–244. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyet C, Poisson A. New determination of carbonic acid dissociation constants in seawater as a function of temperature and salinity. Deep Sea Res. 1989;36:1635–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A, Manodori A, Snyder D. Light-harvesting proteins of diatoms: their relationship to the chlorophyll a/b binding proteins of higher plants and their mode of transport into plastids. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;224:91–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00259455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilloton MB, Korte JJ, Lamblin AF, Fuchs JA, Anderson PM. Carbonic anhydrase in Escherichia coli: a product of the cyn operon. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3731–3734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, Waters RE, Taylor FJR. A broad spectrum artificial seawater medium for coastal and open ocean phytoplankton. J Phycol. 1980;16:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett-Emmett D, Tashian RE. Functional diversity, conservation, and convergence in the evolution of the α-, β-, and γ-carbonic anhydrase gene families. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996;5:50–77. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltonen T, Björkbacka H, Forsman C, Clarke AK, Samuelsson G. Intracellular β-carbonic anhydrase of the unicellular green alga Coccomyxa: cloning of the cDNA and characterization of the functional enzyme overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:1341–1349. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.4.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltonen T, Karlsson J, Palmqvist K, Clarke AK, Samuelsson G. Purification and characterization of an intracellular carbonic anhydrase from the unicellular green alga Coccomyxa. Planta. 1995;195:345–351. doi: 10.1007/BF00202591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Rodriguez MD, Merrett MJ. Dissolved inorganic carbon utilization and the development of extracellular carbonic anhydrase by the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. New Phytol. 1997;135:163–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey SW, Humphrey GF. New spectrophotometric equations for determining chlorophylls a,b,c1, and c2 in higher plants, algae and natural phytoplancton. Biochem Physiol Pflanzen. 1975;167:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- John-McKay ME, Colman B. Variation in the occurrence of external carbonic anhydrase among strains of the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Bacillariophyceae) J Phycol. 1997;33:988–990. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston AM, Raven JA. Inorganic carbon accumulation by the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Eur J Phycol. 1996;31:285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, Reinhold L. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in photosynthetic microorganisms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:539–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J, Clarke AK, Chen ZY, Hugghins SY, Park YI, Husic HD, Moroney JV, Samuelsson G. A novel α-type carbonic anhydrase associated with the thylakoid membrane in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is required for growth at ambient CO2. EMBO J. 1998;17:1208–1216. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber MS, Pai EF. The active site architecture of Pisum sativum β-carbonic anhydrase is a mirror image of that of α-carbonic anhydrases. EMBO J. 2000;19:1407–1418. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisker C, Schindelin H, Alber BE, Ferry JG, Rees DC. A left-handed β-helix revealed by the crystal structure of a carbonic anhydrase from the archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. EMBO J. 1996;15:2323–2330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeau N, Coleman JR. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA coding for pea chloroplastic carbonic anhydrase. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:264–268. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.1.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y, Colman B. Induction of CO2 and bicarbonate transport in the green alga, Chlorella ellipsoidea: I. Time course of induction of the two systems. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:247–252. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.1.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y, Hara T, Colman B. Regulation of the induction of bicarbonate uptake by dissolved CO2 in the marine diatom, Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Cell Environ. 2001;24:611–620. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi S, Miyachi S. Amino acid sequence homology between N- and C-terminal halves of a carbonic anhydrase in Porphyridium purpureum, as deduced from the cloned cDNA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28703–28709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi S, Mizushima T, Yamashita E, Yamamoto M, Kumasaka T, Moriyama H, Ueki T, Miyachi S, Tsukihara T. X-ray structure of β-carbonic anhydrase from the red alga, Porphyridium purpureum, reveals a novel catalytic site for CO2 hydration. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5521–5526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroney JV, Bartlett SG, Samuelsson G. Carbonic anhydrases in plants and algae. Plant Cell Environ. 2001;24:141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Moroney JV, Chen ZY. The role of the chloroplast in inorganic carbon uptake by eukaryotic algae. Can J Bot. 1998;76:1025–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Moroney JV, Somanchi A. How do algae concentrate CO2 to increase the efficiency of photosynthetic carbon fixation? Plant Physiol. 1999;119:9–16. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimer NA, Brownlee C, Merrett MJ. Extracellular carbonic anhydrase facilitates carbon dioxide availability for photosynthesis in the marine dinoflagellate Prorocentrum micans. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:105–111. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimer NA, Iglesias-Rodriguez MD, Merrett MJ. Bicarbonate utilization by marine phytoplankton species. J Phycol. 1997;33:625–631. [Google Scholar]

- Park YI, Karlsson J, Rojdestvenski I, Pronina N, Klimov V, Öquist G, Samuelsson G. Role of a novel photosystem II-associated carbonic anhydrase in photosynthetic carbon assimilation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. FEBS Let. 1999;444:102–105. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR. Expression of human carbonic anhydrase in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7942 creates a high CO2-requiring phenotype. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:505–513. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.2.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Howitt SM, Harrison K, Badger MR. Analysis of a genomic DNA region from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC7942 involved in carboxysome assembly and function. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2871–2879. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2871-2879.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. CO2-concentrating mechanisms: a direct role for thylakoid lumen acidification? Plant Cell Environ. 1997;20:147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Rawat M, Moroney JV. Partial characterization of a new isoenzyme of carbonic anhydrase isolated from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9719–9723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SB, Lane TW, Morel FMM. Carbonic anhydrase in the marine diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii (Bacillariophyceae) J Phycol. 1997;33:845–850. [Google Scholar]

- Rotatore C, Colman B. The acquisition and accumulation of inorganic carbon by the unicellular green alga Chlorella ellipsoidea. Plant Cell Environ. 1991;14:377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Satoh A, Iwasaki T, Odani S, Shiraiwa Y. Purification, characterization and cDNA cloning of soluble carbonic anhydrase from Chlorella sorokiniana grown under ordinary air. Planta. 1998;206:657–665. doi: 10.1007/s004250050444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KS, Ferry JG. A plant-type (β-class) carbonic anhydrase in the thermophilic methanoarchaeon Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6247–6253. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6247-6253.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KS, Ferry JG. Prokaryotic carbonic anhydrases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:335–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KS, Jakubzick C, Whittam TS, Ferry JG. Carbonic anhydrase is an ancient enzyme widespread in prokaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15184–15189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strop P, Smith KS, Iverson TM, Ferry JG, Rees DC. Crystal structure of the “cab” type beta class carbonic anhydrase from the archaeon Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10299–10305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sültemeyer D, Schmidt C, Fock HP. Carbonic anhydrases in higher plants and aquatic microorganisms. Physiol Plant. 1993;88:179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Tachiki A, Fukuzawa H, Miyachi S. Characterization of carbonic anhydrase isozyme CA2, which is the CAH2 gene product in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1992;56:794–798. doi: 10.1271/bbb.56.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashian RE. The carbonic anhydrases: widening perspectives on their evolution, expression and function. Bioessays. 1989;10:186–192. doi: 10.1002/bies.950100603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortell PD, Reinfelder JR, Morel FMM. Active uptake of bicarbonate by diatoms. Nature. 1997;390:243–234. [Google Scholar]

- Van K, Spalding MH. Periplasmic carbonic anhydrase structural gene (Cah1) mutant in Chlamydomonas reihardtii. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:757–764. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.3.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G. Patterns of amino acids near signal-sequence cleavage sites. Eur J Biochem. 1983;133:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur KM, Anderson NG. Electrometric and colorimetric determination of carbonic anhydrase. J Biol Chem. 1948;176:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TG, Colman B. Identification of distinct internal and external isozymes of carbonic anhydrase in Chlorella saccharophila. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:943–948. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SY, Tsuzuki M, Miyachi S. Carbonic anhydrase of Chlamydomonas: purification and studies on its induction using antiserum against Chlamydomonas carbonic anhydrase. Plant Cell Physiol. 1985;26:25–34. [Google Scholar]