Abstract

Anthranilate synthase (AS) is a key enzyme in the synthesis of tryptophan (Trp), indole-3-acetic acid, and indole alkaloids. Two genes, OASA1 and OASA2, encoding AS α-subunits were isolated from a monocotyledonous plant, rice (Oryza sativa cv Nipponbare), and were characterized. A phylogenetic tree of AS α-subunits from various species revealed a close evolutionary relationship among OASA1 and Arabidopsis ASA2, Ruta graveolens ASα2, and tobacco ASA2, whereas OASA2, Arabidopsis ASA1, and R. graveolens ASα1 were more distantly related. OASA1 is expressed in all tissues tested, but the amount of its mRNA was greater in panicles than in leaves and roots. The abundance of OASA2 transcripts is similar among tissues and greater than that of OASA1 transcripts; furthermore, OASA2 expression was induced by a chitin heptamer, a potent elicitor, suggesting that OASA2 participates in secondary metabolism. Expression of wild-type OASA1 or OASA2 transgenes did not affect the Trp content of rice calli or plants. However, transformed calli and plants expressing a mutated OASA1 gene, OASA1(D323N), that encodes a protein in which aspartate-323 is replaced with asparagine manifested up to 180- and 35-fold increases, respectively, in Trp accumulation. These transgenic calli and plants were resistant to 300 μm 5-methyl-Trp, and AS activity of the calli showed a markedly reduced sensitivity to Trp. These results show that OASA1 is important in the regulation of free Trp concentration, and that mutation of OASA1 to render the encoded protein insensitive to feedback inhibition results in accumulation of Trp at high levels. The OASA1(D323N) transgene may prove useful for the generation of crops with an increased Trp content.

In higher plants, the Trp biosynthetic pathway provides the essential amino acid Trp, as well as produces various secondary metabolites, including the hormone indole-3-acetic acid and plant defense compounds (Radwanski and Last, 1995). However, the mechanisms by which these two functions are regulated remain unknown.

Anthranilate is a common precursor of all these compounds and anthranilate synthase (AS) catalyzes the synthesis of anthranilate from chorismate and Gln. Purified plant AS proteins are heteromers that consist of two subunits termed α and β (Poulsen et al., 1993; Bohlmann et al., 1995; Romero and Roberts, 1996). Although the synthesis of anthranilate from chorismate and Gln requires α- and β-subunits of AS, the α-subunit is able to catalyze the synthesis of anthranilate from chorismate with ammonia as an amino donor in the presence of high concentrations of ammonium (Niyogi and Fink, 1992; Niyogi et al., 1993; Bohlmann et al., 1995). Specific amino acids in the α-subunit of bacterial AS are important for feedback inhibition of the enzyme by Trp (Matsui et al., 1987; Caligiuri and Bauerle, 1991).

Complementary DNAs encoding two nonallelic AS α-subunit genes have been isolated from Arabidopsis (ASA1 and ASA2) and Ruta graveolens (ASα1 and ASα2; Niyogi and Fink, 1992; Bohlmann et al., 1995). Tobacco appears to possess more than two different AS α-subunit genes, but only one cDNA, termed ASA2, has been cloned (Song et al., 1998). The enzymes encoded by R. graveolens ASα1 (Bohlmann et al., 1996) and tobacco ASA2 (Song et al., 1998) are Trp insensitive, with the former being implicated in alkaloid biosynthesis (Bohlmann et al., 1995, 1996). In a similar manner, the enzyme encoded by one of the two AS genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is feedback insensitive and is implicated in the production of pynocyanin, the characteristic phenazine pigment of this bacterium (Essar et al., 1990).

In addition to differences in feedback inhibition of the encoded proteins, the two different AS α-subunit genes appear to be subject to distinct mechanisms of transcriptional regulation. Accumulation of Arabidopsis ASA1 mRNA is induced by wounding and bacterial infection, whereas ASA2 mRNA is present in small amounts and does not respond to these stimuli. In a similar manner, the abundance of R. graveolens ASα1 transcripts increases by a factor of approximately 100 in response to treatment with a fungal elicitor, whereas the number of ASα2 transcripts is not affected and the gene is expressed constitutively. The marked increases in the steady-state amounts of ASA1 and ASα1 mRNAs induced by wounding or pathogen-related stimuli suggest a role for these genes in the production of defense-associated substances (Niyogi and Fink, 1992; Bohlmann et al., 1996).

Although ASA1 is thought to participate in the synthesis of secondary metabolites, ASA1 mutants of Arabidopsis exhibit increased concentrations of soluble Trp as a result of altered feedback regulation of AS activity (Kreps et al., 1996; Li and Last, 1996). The tobacco ASA2 enzyme is thought to be related to R. graveolens ASα1 because of its insensitivity to Trp. Overexpression of tobacco ASA2 in the forage legume Astragalus sinicus resulted in an increase of the concentration of free Trp (Cho et al., 2000). These observations indicate that despite their predicted role in alkaloid synthesis, feedback-insensitive AS enzymes mediate Trp accumulation. It might, therefore, be expected that the AS enzymes not linked to alkaloid synthesis, such as those encoded by ASα2 and Arabidopsis ASA2, may possess an even greater potential for inducing Trp accumulation.

Given that cereal crops such as rice, maize, wheat, and oats exhibit a relatively low content of Trp in seed storage proteins, an increase in the abundance of this amino acid would improve their nutritional value. We now describe the identification and characterization of two AS α-subunit genes (OASA1 and OASA2) from rice (Oryza sativa cv Nipponbare), a monocotyledonous plant, and we demonstrate an important role for OASA1 in Trp synthesis. We generated feedback-insensitive mutants of OASA1 whose expression resulted in the accumulation of free Trp at markedly increased concentrations in calli and plant leaves.

RESULTS

Isolation of Two AS α-Subunit Genes from Rice

To isolate rice AS genes we screened a rice cDNA library with a probe based on Arabidopsis ASA1. Of 900,000 clones screened, 11 positive clones were isolated, sequenced, and categorized. The positive clones corresponded to two distinct cDNA sequences showing similarity to Arabidopsis ASA1 or ASA2. The clone with the largest insert, number 5-1, contained a complete open reading frame (ORF), which we designated OASA1 because it showed greater sequence similarity to Arabidopsis ASA1 than it did to ASA2 from this plant. The other cDNA represented in the positive clones was designated OASA2; however, the nucleotide sequence corresponding to the NH2-terminal region of the encoded protein was missing from the OASA2 clones.

To determine the nucleotide sequence of the missing 5′ region of the OASA2 ORF we partially sequenced a genomic DNA clone. Digestion of genomic DNA with EcoRI yielded fragments of approximately 6.2 and 6.4 kb, which hybridized on Southern-blot analysis with the Arabidopsis ASA1 probe used for cDNA library screening. Size-fractionated EcoRI-generated DNA fragments of approximately 6.0 to 6.5 kb were cloned into a λZAPII vector; of 270,000 clones screened with the ASA1 cDNA probe, 23 positive clones were isolated and analyzed. Sequence analysis revealed that a clone corresponding to the 6.4-kb hybridizing fragment was derived from OASA1, whereas another clone corresponding to the 6.2-kb hybridizing fragment appeared to be derived from OASA2. Both clones contained the entire respective ORFs.

To clone the 5′ portion of the OASA2 ORF we designed primers to amplify the region containing the putative AUG start codon by reverse transcription and PCR. The resulting cDNA fragments were cloned into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and their sequences were confirmed to be consistent with the genomic DNA sequence, with the exception of the spliced introns. This 5′ region of the ORF was ligated to the cDNA fragment that lacked this region to generate the full-length OASA2 ORF.

Southern-blot analysis of EcoRI-digested rice genomic DNA with the Arabidopsis ASA1 cDNA probe yielded no signals other than the 6.2- and 6.4-kb fragments under low-stringency hybridization conditions. We, therefore, concluded that the rice genome possesses only two homologous AS α-subunit genes, OASA1 and OASA2, which encode proteins of 577 and 606 amino acids, respectively.

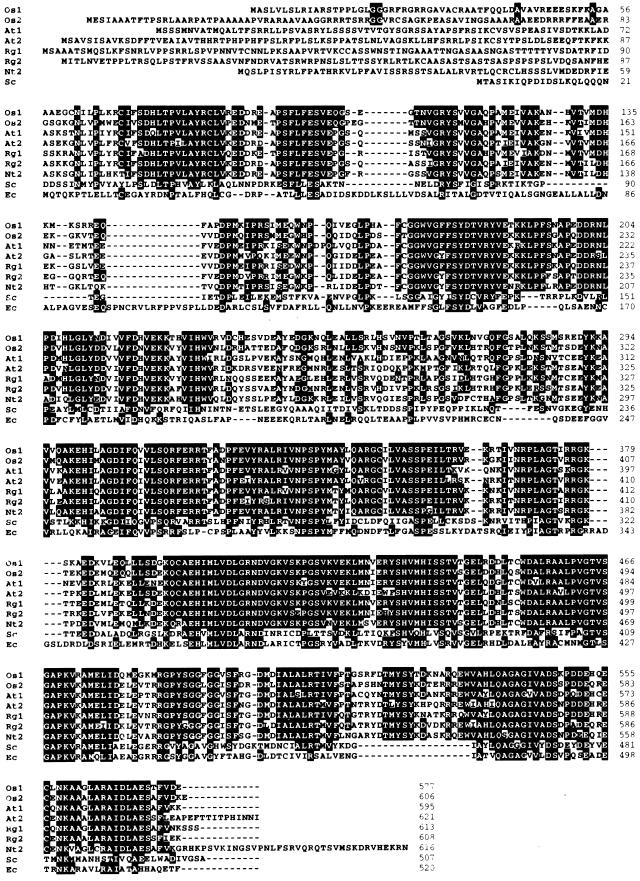

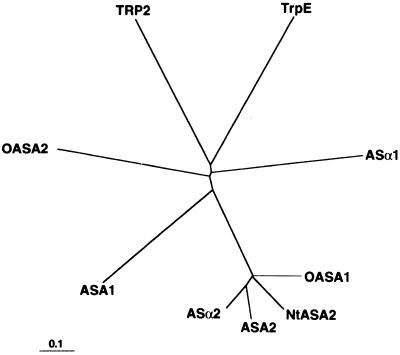

The amino acid sequences deduced from the OASA1 and OASA2 cDNAs were aligned with those of AS α-subunits of dicotyledonous plants and microorganisms (Fig. 1). The NH2-terminal regions of OASA1 and OASA2 exhibited almost no sequence similarity to each other. Likewise, the NH2-terminal sequences of other plant homologs are highly variable and are predicted to contain plastid-localization signals (Zhao and Last, 1995). These regions of OASA1 and OASA2 are relatively rich in specific amino acid residues, including Ser, Thr, Lys, and Arg, and are relatively deficient in acidic amino acids. These characteristics thus suggest that the NH2-termini of OASA1 and OASA2 also act as signal peptides for plastid localization (Gavel and von Heijne, 1990). The mature 521- and 523-residue OASA1 and OASA2 proteins (assuming cleavage to be determined by an Asn residue at positions 62 and 89, respectively) show extensive sequence homology to each other (72% identity) and to other AS α-subunits (71%–74%); the sequence identity shared with Saccharomyces cerevisiae TRP2 and Escherichia coli TrpE was only 23% and 33%, respectively. There was no significant difference in sequence identity between AS α-subunits of dicotyledons and those of the monocotyledon rice. However, a phylogenetic tree based on deduced amino acid sequences revealed a close evolutionary relationship among Arabidopsis ASA2, R. graveolens ASα2, tobacco ASA2, and rice OASA1 (Fig. 2). In contrast, Arabidopsis ASA1, R. graveolens ASα1, and rice OASA2 exhibited a level of evolutionary diversity similar to that of their microbial homologs.

Figure 1.

Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of rice OASA1 and OASA2 with those of other AS α-subunits. The sequences shown are encoded by the following genes: Os1 and Os2, rice OASA1 (GenBank accession no. AB022602), and OASA2 (AB022603), respectively; At1 and At2, Arabidopsis ASA1 (M92353) and ASA2 (M92354), respectively; Rg1 and Rg2, R. graveolens ASα1 (L34343) and ASα2 (L34344), respectively; Nt2, tobacco ASA2 (Song et al., 1998); Sc, S. cerevisiae TRP2 (X68327); and Ec, E. coli trpE (V00368). Hyphens indicate gaps introduced to optimize alignment. Residues shared by OASA1 and OASA2 are shaded, and residue numbers are shown on the right.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relations among AS α-subunits. The amino acid sequences of OASA1 (residues 57–577), OASA2 (residues 84–606), Arabidopsis ASA1 (residues 73–595), Arabidopsis ASA2 (residues 88–621), ASα1 (residues 91–613), ASα2 (residues 88–609), tobacco (Nt) ASA2 (residues 60–618), TRP2 (residues 22–507), and TrpE (residues 1–520) were analyzed (Fig. 1). The phylogenetic tree was constructed from the evolutionary distance data derived by the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The bootstrap procedure was sampled 1,000 times with replacement by CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al., 1994). The bar indicates the distance corresponding to 10 changes per 100 amino acid positions.

The OASA2 cDNA was expressed by transformation of the E. coli mutant strain B666 (ΔtrpE), which is deficient in the endogenous AS α-subunit. The Trp requirement of B666 cells was reduced by transformation with the plasmid pTASA2F, which contains the full-length OASA2 ORF. Complementation was apparent under the restricted conditions, with a requirement for 50 μm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, 100 mm NH4Cl, and 1% (w/v) casamino acids (data not shown).

Analysis of Gene Expression

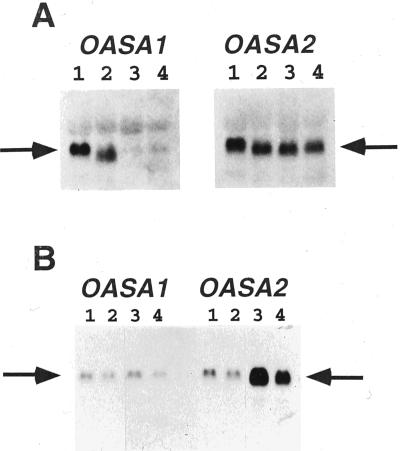

We examined the expression of OASA1 and OASA2 in rice tissue with the use of RNA gel-blot analysis and digoxigenin-labeled antisense riboprobes prepared from the corresponding cDNAs; hybridization was performed under high-stringency conditions to prevent cross-hybridization of OASA1 and OASA2 mRNAs with the two probes. The sizes of the OASA1 and OASA2 transcripts, estimated from the sizes of ribosomal RNAs, were 2.1 and 2.4 kb, respectively. The two genes were shown to be expressed differentially in adult plants (Fig. 3A). OASA1 mRNA was detected in immature panicles, but was ambiguous in leaves and root, when total RNA was used for analysis (Fig. 3). We confirmed the expression of OASA1 in leaves and roots using enriched poly(A)+ RNA samples (data not shown). The result of Figure 3 using total RNA presented different expression of OASA1 in tissues. In contrast, the amount of OASA2 mRNA was similar in all tissues analyzed and was greater than that of OASA1 mRNA. Both genes were expressed at a relatively high level in cultured cells.

Figure 3.

RNA gel-blot analysis of OASA1 and OASA2 expression. A, Tissue distribution of transcripts. Total RNA (10 μg) isolated from calli (lane 1), panicles (lane 2), roots (lane 3), and leaves (lane 4) of rice was subjected to RNA gel-blot analysis with digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes specific for OASA1 (left) or OASA2 (right) transcripts. The positions of the corresponding transcripts are indicated by arrows. B, Effects of an elicitor on transcript abundance. Suspension cultures of rice cells were incubated with chitin heptamer (1 μg mL−1) for 0 min (lane 1), 30 min (lane 2), 120 min (lane 3), or 180 min (lane 4), after which total RNA was isolated and analyzed as in A.

The expression of Arabidopsis ASA1 and R. graveolens ASα1 is induced by an elicitor or by pathogen invasion (Niyogi and Fink, 1992; Bohlmann et al., 1995). To test the inducibility of the two rice AS α-subunit genes, we added N-acetylchitohepalose (1 μg mL−1), a potent elicitor (Yamada et al., 1993), to suspension cultures of rice calli. The elicitor induced a time-dependent increase in the abundance of OASA2 mRNA, but had no effect on that of OASA1 mRNA (Fig. 3B); the maximal effect of chitin heptamer was apparent after approximately 2 h.

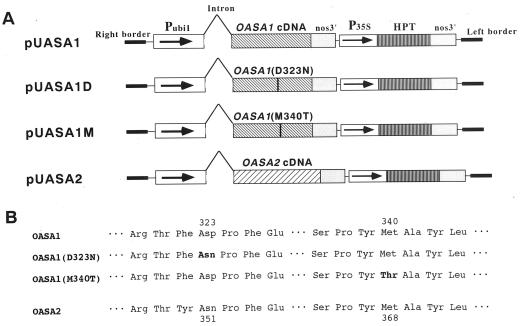

Generation of Transgenic Rice

Two types of mutated OASA1 cDNAs were constructed by PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 4). One mutated cDNA, OASA1(D323N), was designed to encode a protein in which Asp-323 was replaced by Asn. This Asp residue is well conserved among plant AS α-subunits, with the only exception of OASA2, and the same mutation in ASA1 was previously shown to render Arabidopsis resistant to 5-methyl-Trp (5MT; Kreps et al., 1996; Li and Last, 1996). The second mutated OASA1 cDNA, designated OASA1(M340T), was designed to encode a protein in which Met-340 was replaced by Thr; the corresponding mutation has been identified in a mutant of Salmonella typhimurium (Caligiuri and Bauerle, 1991). Each mutated cDNA as well as wild-type OASA1 and OASA2 cDNAs were introduced individually into the T-vector using the maize Ubi1 promoter for high-level expression in rice (Fig. 4). Transformed calli and regenerated plants were established by transfection with Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA101 harboring each of the four cDNA constructs.

Figure 4.

Construction of binary vectors for rice transformation. A, Structure of the T region of each vector. pUASA1 was constructed for expression of wild-type OASA1 cDNA, pUASA1D for a mutated OASA1 cDNA [OASA1(D323N)] encoding a protein in which Asp-323 is replaced by Asn, pUASA1M for a mutated OASA1 cDNA [OASA1(M340T)] encoding a protein in which Met-340 is replaced by Thr, and pUASA2 for wild-type OASA2 cDNA. A 2-kb maize Ubi1 fragment including the promoter region (PUbil) and 1-kb intron of the 5′-untranslated region was ligated to each rice cDNA at a point immediately downstream of the 3′ side of the intron junction. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription. See “Materials and Methods” for further details. B, Alignment of the amino acid sequences surrounding the mutated residue (bold) of each transgene product. The mutated gene OASA1(D323N) and wild-type OASA2 each encode Asn at the corresponding positions 323 and 351, respectively.

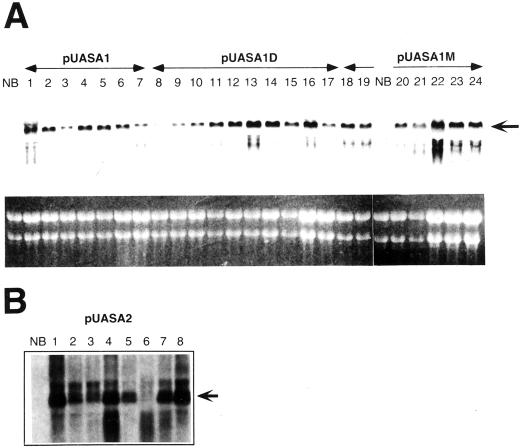

Many independent transformants and transgenic plants were generated. Expression of the introduced cDNAs was examined by RNA gel-blot analysis (Fig. 5). Almost all calli and regenerated plants analyzed exhibited a high level of expression of the transgenes; one exception was number D5 in which the abundance of OASA1(D323N) mRNA was low, although hygromycin resistance was maintained. Because of high-level expression of the transgenes, film-exposing time of Figure 5 was shorter than that of Figure 3. In Figure 5, this time was not enough for capturing endogenous OASA1 and OASA2 signals.

Figure 5.

Expression of OASA transgenes in transformants. A, Expression of wild-type or mutated OASA1 transgenes in transformed calli. Total RNA (10 μg) was subjected to RNA gel-blot analysis with a digoxigenin-labeled OASA1 riboprobe (top); the ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel is also shown (bottom). NB, Untransformed Nipponbare callus; lanes 1 through 7, Transformants expressing the wild-type OASA1 transgene (nos. W1, W2, W3, W4, W5, W9, and W10, respectively); lanes 8 through 17, Calli expressing the OASA1(D323N) transgene (nos. D5, D11, D13, D16, D17, D18, D19, D20, D25, and D26, respectively); lanes 18 through 24, Calli expressing the OASA1(M340T) transgene (nos. E1, E2, E3, E10, E12, E15, and E16, respectively). B, Expression of the OASA2 transgene in the leaves of pUASA2 transformants. Lanes 1 through 8, Regenerated plants from callus line numbers 25-2, 22 -1, 47-3, 38-1, 49-1a, 46-1, 28-2, and 49-1b, respectively. Arrows in A and B indicate the transgene-derived transcripts.

5MT Resistance of Transformed Calli and Progeny Seedlings

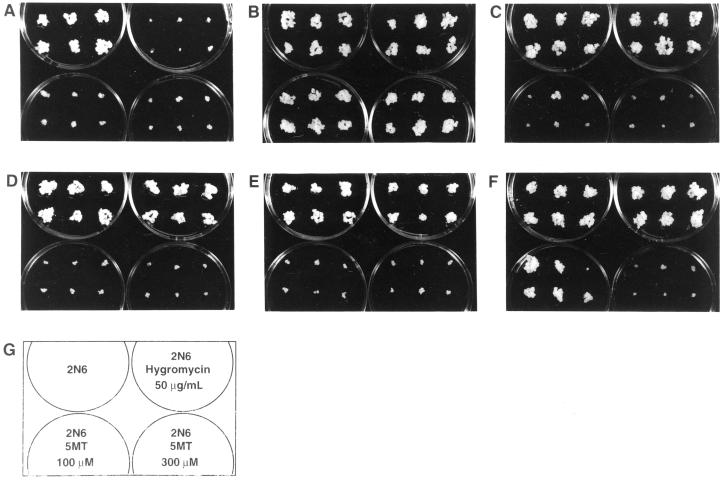

The various types of transformed calli were tested for their sensitivity to 100 and 300 μm 5MT (Fig. 6). Those expressing the OASA1(D323N) transgene exhibited marked resistance to 5MT. Calli that had been maintained on hygromycin-containing medium during subculture exhibited growth on medium containing 300 μm 5MT that was 30% to 70% of that apparent on control medium without 5MT or hygromycin (N6 medium [Chu et al., 1975] supplemented with 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid [2,4-D] and casamino acid [2N6]; data not shown). Calli that had been maintained on medium without hygromycin showed the same amount of growth on medium containing 300 μm 5MT as they did on 2N6 medium (Fig. 6B). In contrast, untransformed calli (Fig. 6A) as well as calli expressing OASA1 (Fig. 6C) or OASA1(M340T) (Fig. 6D) transgenes did not grow in the presence of 100 or 300 μm 5MT. Of 61 transformed callus lines expressing the OASA2 transgene examined, 31 lines grew on medium containing 100 μm 5MT (Fig. 6, E and F; Table I); however, none of the calli was able to grow in the presence of 300 μm 5MT. Thus, only approximately 50% of the calli transformed with the OASA2 transgene exhibited resistance to 5MT, and the level of resistance shown was moderate. Given that RNA gel-blot analysis showed that all OASA2-transformed calli examined expressed the transgene at a similar level (Fig. 5B), the difference in resistance did not reflect a difference in the level of transgene expression.

Figure 6.

5MT resistance of transformed rice calli. Calli of NB (A), transformant number D10-5 expressing OASA1(D323N) (B), transformant number W9 expressing OASA1 (C), transformant number E1 expressing OASA1(M340T) (D), and transformants numbers 25-2 (sensitive) (E) and 49-1 (moderately resistant) (F) expressing OASA2 were photographed after cultivation for 3 weeks. The medium conditions are shown in G.

Table I.

Sensitivity to 5MT and free Trp content of transformants expressing the OASA2 transgene

| Line | Growth Rate of Callusa | Sensitivity to 5MTb | Trp

|

Relative Trp Content

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calli | Leaves | Calli | Leaves | |||

| % | nmol g−1 fresh wt | |||||

| Control | ||||||

| NB | 6.0 | S | 35 | 102 | 1 | 1 |

| Transformed | ||||||

| 3-1 | 4.8 | S | 56 | 59 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| 22-1 | 2.8 | S | 71 | 79 | 1.6 | 0.8 |

| 24-2c | 98.0 | MR | 49 | 1.1 | ||

| 25-2 | 7.9 | S | 48 | 48 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| 28-2 | 64.1 | MR | 39 | 30 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| 30-1c | 47.2 | MR | 31 | 0.7 | ||

| 38-1 | 45.5 | MR | 55 | 153 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| 46-1 | 75.8 | MR | 56 | 160 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| 47-3 | 43.9 | MR | 70 | 28 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 49-1 | 77.0 | MR | 77 | 50 | 1.7 | 0.5 |

Growth rate represents the fresh wt of calli grown in the presence of 100 μm 5MT expressed as a percentage of that of calli grown in the absence of 5MT.

S, Sensitive; MR, moderately resistant.

Transformed calli of lines no. 24-2 and 30-1 did not regenerate plants.

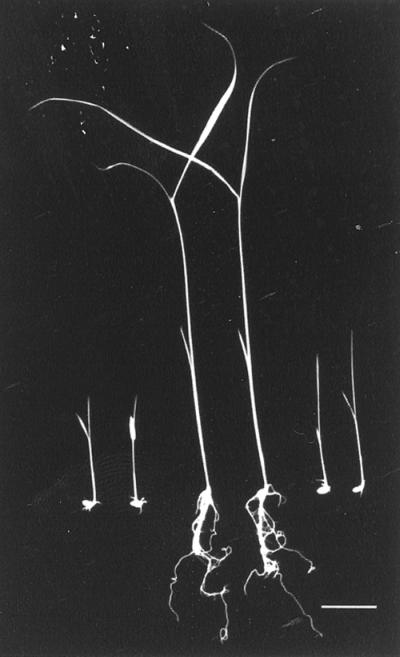

The inheritance of 5MT resistance in OASA1(D323N) transgenic rice was confirmed by a germination test. Growth of resistant seedlings in transgenic line number D1-1-5 was thus vigorous on medium containing 300 μm 5MT (Fig. 7). There was no difference in growth of seedlings on medium without 5MT between parental variety Nipponbare and line number D1-1-5. The progeny seeds of all tested transgenic plants showed segregation of the 5MT sensitivity trait. Calli derived from resistant progeny seeds also exhibited resistance to 5MT (data not shown). These observations indicated that only the OASA1(D323N) transgene conferred 5MT resistance to transformed calli and progeny seedlings.

Figure 7.

Segregation of 5MT resistance in progeny. Growth after 14 d of control cv Nipponbare seedlings (left two) and of segregants of transgenic line number D1-1-5 expressing OASA1(D323N) (right four) on medium containing 300 μm 5MT. The segregation ratio for resistance and sensitivity to 5MT in this line was 20:5. Bar = 2 cm.

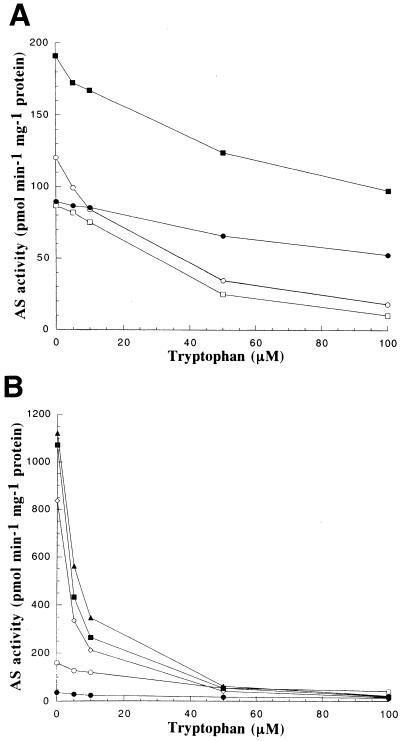

AS Activity of Transformants

The 5MT resistance of transgenic lines expressing OASA1(D323N) suggested that the D323N mutation affected feedback regulation of OASA1. To characterize the mutant enzyme we performed in vitro AS activity assays with calli expressing OASA1(D323N), OASA1, or OASA2 transgenes. Extracts were prepared from calli growing on 2N6 plates and were subjected to gel filtration chromatography to remove endogenous Trp, chorismic acid, Gln, and other low Mr molecules. The AS activity of untransformed calli and of transformed calli with a high level of expression of the OASA1 transgene was inhibited by 71% in the presence of 50 μm Trp, compared with the activity apparent in the absence of this amino acid (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the AS activity of calli expressing the OASA1(D323N) transgene was inhibited by only 26% in the presence of 50 μm Trp and by 47% in the presence of 100 μm Trp. The latter calli thus exhibited substantial Trp-insensitive AS activity. The AS-specific activity of these calli was, however, similar to that of untransformed cells or OASA1-expressing lines.

Figure 8.

Relative AS activities of transformants expressing OASA1, OASA1(D323N), or OASA2 transgenes. A, Untransformed calli (○) as well as calli of transformant number W2 expressing OASA1 (□), and transformant numbers D17 (●) and D13 (▪) expressing OASA1(D323N) were assayed for AS activity in the presence of various concentrations of Trp. B, Untransformed calli (○) and OASA2-expressing calli numbers 14-1 (▴), 25-2 (●), 46-2 (▪), and 49-1 (⋄) were assayed for AS activity. Data are expressed as picomoles of anthranilate produced per minute per milligram of protein, and are means of triplicates from a representative experiment.

Transformants expressing OASA2 showed two patterns of AS activity (Fig. 8B). One line, number 25-2, exhibited a level of AS activity substantially less than that of untransformed calli, whereas others (nos. 14-1, 46-2, and 49-1) showed markedly increased levels of AS activity in the presence of low concentrations of Trp. The AS activity of these latter transgenic lines was, however, inhibited by Trp in an apparently normal manner; activity in the presence of 50 μm Trp was only approximately 5% of that in its absence.

Trp Content of Transformants

The feedback-insensitive AS activity as well as 5MT resistance of calli expressing the OASA1(D323N) transgene might be expected to result in Trp accumulation. We, therefore, next measured the soluble amino acids of calli after culture on 2N6 medium for 2 weeks. The soluble Trp content of transformed calli expressing OASA1(D323N) was increased by a factor of up to 180 compared with that of control calli (Fig. 9; Table II). The abundance of the other 19 amino acids or of anthranilate was not affected in the transformed calli. A high Trp content was also detected in the leaves of progeny seedlings from transgenic rice expressing OASA1(D323N) (Table III). Compared with untransformed plants, the soluble Trp content of the transgenic rice was increased by a factor of approximately 25 to 35, whereas transgenic plants expressing OASA1 (W) did not increase the level of Trp. All progeny seedlings analyzed were selected on medium containing 40 mg L−1 hygromycin and were grown under the same condition. These results revealed that supplement of hygromycin in medium did not cause increased level of soluble Trp in transgenic plants expressing OASA1(D323N).

Figure 9.

HPLC Profiles of soluble amino acids in untransformed calli and calli expressing OASA1(D323N). Untransformed calli (A) and OASA1(D323N)-expressing calli (B) of transformant number D13 were analyzed for soluble amino acid content by HPLC. Retention times for each amino acid and anthranilate were determined with standard samples. Peak numbers: 1, Asp; 2, Glu; 3, Ser; 4, Asn; 5, Gly; 6, Gln; 7, His; 8, Thr; 9, Ala; 10, Arg; 11, Pro; 12, Tyr; 13, Val; 14, Met; 15, Cys; 16, anthranilate; 17, Ile; 18, Leu; 19, Phe; 20, Trp; and 21, Lys.

Table II.

Free amino acid profiles of transformed calli

| Line | Free Amino Acid Content

|

Relative Trp Content | Trp | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp | Glu | Ser | Asn | Gly | Gln | His | Thr | Ala | Arg | Pro | Tyr | Val | Met | Cys | Anthranilate | Ile | Leu | Phe | Trp | Lys | Total | |||

| nmol g−1 fresh wt | % of total amino acids | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| NB | 211 | 696 | 174 | 329 | 199 | 879 | 875 | 214 | 91 | 111 | 169 | 60 | 124 | 11 | 473 | 28 | 63 | 45 | 47 | 16 | 84 | 4,889 | 1 | 0.4 |

| NB | 166 | 607 | 133 | 196 | 168 | 522 | 651 | 225 | 123 | 137 | 83 | 51 | 142 | 15 | 453 | 16 | 88 | 64 | 74 | 16 | 79 | 4,009 | 1 | 0.4 |

| W4 | 206 | 924 | 134 | 81 | 158 | 381 | 651 | 135 | 371 | 203 | 44 | 41 | 91 | 18 | 349 | 40 | 45 | 40 | 32 | 40 | 50 | 4,034 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| D 13 | 207 | 494 | 180 | 163 | 232 | 458 | 1,135 | 186 | 204 | 560 | 202 | 110 | 162 | 27 | 411 | 45 | 101 | 85 | 67 | 1,795 | 116 | 6,940 | 112 | 25.9 |

| D 16 | 255 | 774 | 185 | 221 | 183 | 602 | 1,601 | 215 | 175 | 197 | 376 | 70 | 115 | 23 | 472 | 26 | 75 | 63 | 81 | 1,518 | 84 | 7,311 | 95 | 20.8 |

| D 17 | 233 | 502 | 127 | 166 | 126 | 291 | 546 | 205 | 75 | 94 | 92 | 43 | 95 | 18 | 383 | 17 | 64 | 43 | 72 | 675 | 55 | 3,922 | 42 | 17.2 |

| D 19 | 199 | 873 | 184 | 162 | 209 | 579 | 2,095 | 229 | 375 | 134 | 190 | 103 | 162 | 29 | 470 | 83 | 106 | 115 | 75 | 2,832 | 120 | 9,324 | 177 | 30.4 |

| D 20 | 94 | 331 | 105 | 52 | 170 | 247 | 473 | 317 | 109 | 223 | 44 | 37 | 79 | 15 | 302 | 18 | 53 | 45 | 28 | 996 | 51 | 3,789 | 62 | 26.3 |

W4 is a transformed callus line expressing the OASA1 transgene. D13, D16, D17, D19, and D20 are independent transformed lines expressing the OASA1 (D323N) transgene.

Table III.

Free Trp content of leaves from progeny plants

| Progeny | Total Free Amino Acids | Trp | Relative Trp Content | Trp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol g−1 fresh wt | % of total free amino acids | |||

| NB | 6,128 | 153 | 1 | 2.5 |

| W4-2 | 11,459 | 256 | 1.7 | 2.2 |

| W4-7 | 10,012 | 235 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| D13-5 | 12,740 | 5,354 | 35 | 42.0 |

| D13-6 | 11,941 | 3,653 | 24 | 30.6 |

| D17-4 | 12,516 | 4,842 | 32 | 38.7 |

| D17-5 | 8,718 | 3,842 | 25 | 44.1 |

| D19-1 | 12,829 | 4,619 | 30 | 36.0 |

Progeny seeds of transgenic lines were selected by growth for 2 weeks on germination medium containing hygromycin (40 mg L−1) and control NB seed was grown on germination medium without hygromycin.

The Trp content of 10 callus lines expressing the OASA2 transgene was not increased, even though three of these lines (nos. 24-2, 46-1, and 49-1) showed resistance to 100 μm 5MT (Table I). Thus, the moderate resistance to 5MT induced by expression of the OASA2 transgene did not result from altered feedback regulation of AS.

DISCUSSION

Two Rice Genes Encoding AS α-Subunits

We have isolated two rice genes, OASA1 and OASA2, that encode AS α-subunits. The predicted proteins contain putative plastid transit peptides at their NH2-termini. Although we have not demonstrated that the two proteins are localized in plastids, fusion proteins comprising the respective putative transit peptides linked to green fluorescent protein exhibited a plastid localization in transformed calli (Y. Tosawa and K. Wakasa, unpublished data). The mature rice AS α-subunits shared marked (72%) sequence identity; however, they occupied distinct positions in a phylogenetic tree. Whereas rice OASA1, Arabidopsis and tobacco ASA2, and R. graveolens ASα2 appeared to constitute a monophyletic group, rice OASA2, Arabidopsis ASA1, and R. graveolens ASα1 were more distantly related.

Expression and Predicted Function of OASA1 and OASA2

The abundance of OASA1 transcripts was greater in immature panicles than in leaves and roots. This distribution differs from that of Arabidopsis ASA2 mRNA, which is not detectable in flowers (Niyogi and Fink, 1992). The amount of OASA2 mRNA was similar in all tissues analyzed and was greater than that of OASA1 mRNA. Furthermore, transcription of OASA2, but not that of OASA1, appeared to be induced by chitin heptamer. This N-acetylchitohepalose has been shown to possess elicitor activity; it induces phytoalexin production (Yamada et al., 1993) and jasmonate synthesis (Nojiri et al., 1996) by rice cells in suspension culture. Maximal induction of OASA2 expression was apparent after exposure of cells to the elicitor for 2 h, a time course similar to that for induction of chitinase and Phe-ammonia lyase genes (He et al., 1998; Nishizawa et al., 1999). These results thus suggest that OASA2 is a defense-related gene induced by this elicitor.

Induction of gene expression by defense-related stimuli appears to be a characteristic that differentiates between the members of each pair of genes that encode AS α-subunits in higher plants. On the basis of this criterion, OASA1, Arabidopsis ASA2, and R. graveolens ASα2 belong to the same family of constitutively expressed genes, and OASA2, Arabidopsis ASA1, and R. graveolens ASα1 belong to the same family of inducible genes (Niyogi and Fink, 1992; Bohlmann et al., 1995, 1996). This classification is thus consistent with the phylogenetic relations of these genes.

Transformed Rice Expressing Mutated OASA1 Transgenes

The sequence element Leu-Leu-Glu-Ser (LLES) participates in feedback inhibition of microbial AS α-subunits by Trp (Matsui et al., 1987; Caligiuri and Bauerle, 1991; Graf et al., 1993). This element is highly conserved in AS α-subunits of plants, and the sequence surrounding the LLES element has been implicated in feedback inhibition of tobacco ASA2 (Song et al., 1998). However, substitution of Ser-115 or Ser-129 of Arabidopsis ASA1, which correspond to Ser-65 or Ser-76 of the LLESX10S element in yeast, by Arg did not result in an increase in the Trp content of or in resistance to 5MT in transformed rice calli (Y. Tozawa, H. Hasegawa, T. Terakawa, and K. Wakasa, unpublished data). In contrast, transformed rice calli expressing the OASA1(D323N) transgene were resistant to 300 μm 5MT and exhibited a marked (up to 180-fold) increase in the concentration of free Trp. The AS activity of these transformed calli was also inhibited by only approximately 50% in the presence of 100 μm Trp. We, therefore, concluded that Trp-insensitive AS activity was responsible for the high level of Trp accumulation in these transgenic lines. Inheritance of 5MT resistance was demonstrated by germination tests on medium containing 300 μm 5MT, and the leaves of resistant progeny also manifested a high Trp content. Transformed calli expressing OASA1(M340T) or wild-type OASA1 transgenes were not resistant to 100 μm 5MT and did not exhibit an altered Trp content or AS sensitivity to Trp, suggesting that overproduction of the AS α-subunit itself was not responsible for the observed changes in feedback regulation or Trp synthesis in OASA1(D323N) transformants. The mutation of the Asp residue at position 323 of OASA1 to Asn thus appears to render the enzyme insensitive to Trp and 5MT.

Transformed Rice Expressing an OASA2 Transgene

Asp-323 of OASA1 is well conserved in other plant AS α-subunits, with the exception of OASA2. OASA2 contains an Asn at the corresponding position (residue 351), although the surrounding residues are virtually identical to those of OASA1. This observation suggested that overexpression of OASA2 might result in Trp accumulation. However, transformed calli expressing an OASA2 transgene did not exhibit Trp accumulation or altered sensitivity of AS activity to Trp. Thus, the Arg at position 351 of OASA2 is not sufficient to render the enzyme insensitive to feedback inhibition.

Only some of the transformed callus lines expressing the OASA2 transgene were resistant to 100 μm 5MT and showed an increased level of AS activity in the absence of Trp. These two properties appeared related in that callus line numbers 14-1, 46-2, and 49-1 showed increased AS activity and were resistant to 100 μm 5MT, whereas line 25-2 exhibited a reduced level of AS activity and was sensitive to 5MT. The increased level of AS activity apparent in some of these lines in the absence of Trp might result from the increase in gene dosage for OASA2. The occasional and moderate resistance to 5MT manifested by calli overproducing OASA2 might also be attributable to the increase in the number of AS α-subunit molecules compensating for the presence of inhibitory molecules of Trp or 5MT at low concentrations.

Potential Utility of the OASA1(D323N) Transgene

Various feedback-insensitive AS α-subunits cause Trp accumulation in higher plants. The Arabidopsis mutants trp-5 and amt-1 manifest a free Trp content that is three and five times, respectively, that of wild-type plants; this increase in Trp accumulation is attributable to altered feedback regulation of the AS α-subunit encoded by ASA1 (Kreps et al., 1996; Li and Last, 1996). Expression of the feedback-insensitive tobacco ASA2 protein in the forage legume A. sinicus resulted in a 1.3- to 5.5-fold increase in the amount of free Trp in roots (Cho et al., 2000). Arabidopsis ASA1 and tobacco ASA2 are thought to contribute to the synthesis of secondary metabolites, given that ASA1 transcription is inducible by wounding and the Trp insensitivity of tobacco ASA2 is similar to that of R. graveolens ASα1. In contrast, expression of the Trp-insensitive AS α-subunit encoded by OASA1(D323N) induced up to an approximately 35-fold increase in the amount of free Trp in rice leaves. The Trp content of calli and leaves expressing OASA1(D323N) reached a maximum of 2,832 and 12,829 nmol per gram of fresh weight, respectively, whereas the corresponding mean ± se values for parental variety Nipponbare were 34.8 ± 19.0 and 70.2 ± 49.5 nmol per gram of fresh weight, respectively. Such high levels of Trp accumulation support the notion that OASA1 is important in Trp synthesis, and suggest that AS α-subunits that contribute to Trp synthesis may be more effective in inducing Trp accumulation than are homologs whose primary function is the synthesis of secondary metabolites. Analysis of transgenic plants expressing feedback-insensitive forms of OASA2 is necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Mutation of rice OASA1 appears to affect only Trp accumulation, with no changes in the content of anthranilate or other amino acids having been detected, even though anthranilate is the immediate product of AS activity. The 5MT-resistant rice mutant MTR1 exhibits increased concentrations of not only Trp (87-fold increase in calli), but also Phe (8-fold increase in calli; Wakasa and Widholm, 1987). Chorismate mutase, which is subject to feedback control, is stimulated by Trp (Gilchrist and Kosuge, 1980); however, transformed rice cells expressing OASA1(D323N) contained the same amount of Phe as did control cells. Rice plants that manifest an increase only in Trp content may prove beneficial for breeding.

Cultured rice cells and rice plants that accumulated Trp grew normally. Although a tendency toward reduced seed fertility was apparent in the OASA1(D323N) transgenic plants compared with control Nipponbare plants, enough seeds to obtain progeny were produced by many of the transformed plants. Given that nutritional improvement is an important goal of gene manipulation in plants (Falco et al., 1995; Goto et al., 1999; Ye et al., 2000), the OASA1(D323N) transgene may prove useful for generating a crop with increased Trp content. The free Trp content was also increased in mature seeds of many of the OASA1(D323N) transgenic rice lines (Y. Tozawa, H. Hasegawa, T. Terakawa, and K. Wakasa, unpublished data).

The Trp biosynthetic pathway also provides indole compounds. For example, anthranilate is a precursor for a class of phytoalexins referred to as avenanthramides in oats (Ishihara et al., 1999). The biosynthetic pathway for 2,4-dihydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (DIBOA) and 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (DIMBOA), which contribute to defense against insects and microbial pathogens, branches off the Trp pathway and utilizes indole as a direct intermediate in maize (Frey et al., 1997; Melanson et al., 1997). The presence of phytoalexins and defense compounds derived from the Trp pathway in the Gramineae suggests the importance of studying coordinated regulation of primary and secondary metabolism by the two AS α-subunit genes in monocotyledonous species. In addition to Trp, manipulation of other aromatic compounds such as alkaloids and auxin might also prove to be possible as a result of analyses of transgenic rice plants expressing OASA1(D323N) or OASA2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plants

Rice (Oryza sativa cv Nipponbare) seeds or plants were used for callus induction and isolation of RNA or DNA. Seed calli were induced from scutella by incubation for 3 weeks in the dark at 28°C on 2N6 medium supplemented with 2,4-D (2 mg L−1), casamino acids (1 g L−1), and 0.2% (w/v) Gelrite (Wako Chemicals, Osaka). Total RNA was isolated from calli subcultured on 2N6 medium. For elicitor treatment, calli were subcultured in R2 liquid medium (Ohira et al., 1973) as described previously (Urushibara et al., 2001). Transformed and control calli were subcultured at intervals of 3 weeks on 2N6 medium with or without hygromycin (40 mg L−1). All cultures with the exception of primary seed cultures were maintained in a culture room at 28°C with 16 h of light per day, and regenerated rice plants were grown in a culture room or greenhouse at 30°C under natural light conditions.

Isolation of cDNA

Standard recombinant DNA techniques were performed basically as described (Sambrook et al., 1989). To prepare a probe for library screening we performed PCR with an Arabidopsis cDNA library and the oligonucleotide primers ASA1-a (5′-CATATGTCTTCCTCTATGAAC-3′) and ASA1-b (5′-GGATCCTCATTTTTTCACAAATGC-3′), which were based on the Arabidopsis ASA1 genomic DNA sequence (GenBank accession no. M92353). The PCR product was purified with a Nick spin column (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) and was used to prepare a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled probe with an enhanced chemiluminescence random prime labeling system (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). A rice cv Nipponbare cDNA library described previously (Tozawa et al., 1998) was screened with the labeled probe. Purified phage DNA from isolated clones was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, and the resulting DNA fragments were subcloned into the Bluescript phagemid vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and were sequenced with the use of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled primers, an AutoRead sequencing kit (Pharmacia Biotech), and an ALF II DNA sequencer (Pharmacia Biotech). To recover the 5′ region of the OASA2 ORF, we performed reverse transcription-PCR with primers based on genomic DNA sequence analysis. Analysis of amino acid sequences was performed with CLUSTAL W software (Thompson et al., 1994).

Isolation of Genomic DNA Clones

Genomic DNA was prepared from rice seedlings as described previously (Tozawa et al., 1998). The DNA (15 μg) was digested with various restriction enzymes and was subjected to Southern-blot hybridization with the probe used for isolation of cDNA clones. Genomic DNA digested with EcoRI was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis and fragments of approximately 6.0 to 6.5 kb were recovered from excised gel slices with a Gene Clean Kit (BIO 101, Vista, CA). The DNA fragments were ligated into the λZAPII/EcoRI/CIP cloning vector (Stratagene), and the resulting genomic DNA library was screened with the probe used for cDNA screening. The DNA fragments prepared from isolated clones were digested with restriction enzymes and subcloned into a phagemid vector for sequencing.

RNA Gel-Blot Hybridization

Total RNA was prepared as previously described (Tozawa et al., 1998) from cv Nipponbare or transgenic rice plants. For sampling of RNA from elicitor-treated cells, chitin heptamer, N-acetylchitohepalose (1 μg mL−1), was added to rice calli in suspension culture (He et al., 1998). For the detection of OASA1 and OASA2 transcripts, digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes were prepared with a DIG RNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Basel). A 710-bp fragment of OASA1 cDNA (nucleotides 503–1,212) amplified by PCR with primers 5MT-1 (5′-ACCGCTGCCTCGTCAGGGAGGACG-3′) and RAS4 (5′-CTCAAAACGCTGGCTTAAGAC-3′) was cloned into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen). A 695-bp HindIII-EcoRV fragment of OASA2 cDNA (nucleotides 898–1,592) was subcloned into the pSPT18 vector (Boehringer Mannheim). The corresponding antisense RNA probes were then synthesized by in vitro run-off transcription with T7 RNA polymerase and digoxigenin-labeled UTP. RNA gel-blot hybridization was performed as described previously (Tozawa et al., 1998).

Complementation Analysis

Escherichia coli strain B666, which is deficient in TrpE, was used for complementation tests. The NcoI-BamHI fragment of OASA2 cDNA clone OASA2 number 1, which lacks the 5′ region of the ORF, was cloned into the same sites of the pTrc99A vector (Pharmacia Biotech), giving rise to pTASA2NB. For construction of an expression vector for full-length OASA2, an NcoI site was created by PCR with OASA2 number 1 as template and the primers 2FNCO (5′-CGCCATGGAGTCCATCGCCG-3′) and 5MT-4 (5′-GCTCCTGGGGATCTGCATAGGATC-3′). The PCR product was cloned into the pCRII vector. Clones harboring the OASA2 cDNA fragment, the incorporation of which results in the creation of an ApaI site at the 5′ side, were isolated and sequenced. The ApaI-ApaI fragment of a selected clone (the second ApaI site is located within the OASA2 cDNA sequence) was excised and substituted for the ApaI-ApaI fragment of pTASA2NB, yielding the full-length OASA2 expression vector pTASA2F. This vector was introduced into B666 cells by the standard transformation method (Sambrook et al., 1989). The growth tests for each transformant were performed on M9 plates.

Construction of Binary T-Vectors

T-vectors were constructed from pIG121-Hm (Ohta et al., 1990; Hiei at al., 1994). A DNA fragment containing the sequence from the 5′ end of the nopaline synthase gene (nos) promoter to the 3′ end of the β-glucuronidase gene intron was removed from pIG121-Hm and was replaced with an artificial DNA fragment containing multiple cloning sites, yielding pYT8C-Hm (Urushibara et al., 2001). The maize ubiquitin 1 gene (Ubi1) promoter (Toki et al., 1992; Cornejo et al., 1993) and test gene fragments were inserted into this multicloning region to generate high-level expression vectors (Fig. 4). PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis for construction of mutated OASA1 cDNAs was performed with the primers OsAsN2 (sense, 5′-GTACATTTGCTAACCCCTTTGAGG-3′) and OsAsC1 (antisense, 5′-CAAAGGGGTTAGCAAATGTACGC-3′) for pUASA1D, and OsAsC3 (sense, 5′-CCTAGTCCTTATACGGCCTATCTACAG-3′) and OsAsN3 (antisense, 5′-CTGTAGATAGGCCGTATAAGGACTAGG-3′) for pUASA1M. The cauliflower mosaic virus 35S-hygromycin phosphotransferase (HPT)-3′nos (Ohta et al., 1990) was included as a selection marker in each vector construct. The vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA101 (Hood et al., 1986).

Transformation

Calli induced from seeds during a 3-week incubation were transferred to 2N6, and, after 1 week, were harvested for transformation, which was performed as described previously (Hiei et al., 1994). Selection and plant regeneration were performed as described (Urushibara et al., 2001).

Assay of 5MT Resistance

All transformed callus lines were tested for 5MT resistance on 2N6 solid medium containing 0, 100, or 300 μm 5MT. Sensitivity to 5MT was assessed on the basis of the ratio of the growth after 3 weeks of calli cultivated on medium containing 100 or 300 μm 5MT to that of calli cultivated in the absence of 5MT. Prior to the test, calli were cultured on 2N6 plates without hygromycin or 5MT for 14 d, after which nine pieces of tissue (10–20 mg per piece) were transferred to each plate. The sensitivity of seedlings to 5MT was tested by allowing husked seeds to germinate on Murashige-Skoog medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1963) without hormones but containing 300 μm 5MT. Seedling growth was examined after incubation for 2 weeks.

Amino Acid Analysis

A third or fourth foliage leaf was harvested from each rice plant grown in a greenhouse. Leaves of regenerated plants from transformed calli with the OASA2 gene were harvested 53 d after transferring to a pot. Leaves of parental variety Nipponbare were harvested 58 d after germination. Leaves of progenies of transgenic plants with the OASA1 (D323N) transgene or the OASA1 transgene were harvested 55 d after transferring to a pot from selection medium containing 40 mg L−1 hygromycin for 2 weeks. Leaves of cv Nipponbare were harvested 55 d after transferring to a pot from germination medium without hygromycin for 2 weeks. Transformed calli and cv Nipponbare callus were precultured for 2 weeks on 2N6 medium. Cell extracts were prepared from approximately 500 mg of fresh leaf or 1 g of callus, as previously described (Wakasa and Widholm, 1987), and free amino acids were analyzed with an amino acid analysis system (PICO•TAG, Waters, Milford, MA).

Assay of AS Activity

AS activity was assayed as described by Niyogi et al. (1993), but with several modifications. Cell extracts were prepared from 1 to 2 g of fresh calli. The concentration of glycerol in the grinding buffer was reduced from 60% to 30% (w/v). Ground frozen callus powder was added to 2.5 mL of grinding buffer containing 75 mg of polyvinylpyrrolidone (Sigma, St. Louis), and the mixture was then subjected to vigorous vortex mixing to ensure complete suspension. The suspension was then centrifuged (15,000g for 10 min at 0°C) to remove insoluble material. The resulting supernatant (2.5 mL) was applied to a PD-10 column (Pharmacia Biotech) that had been equilibrated with column buffer (Niyogi et al., 1993), and proteins were eluted with 5 mL of column buffer. Gln-dependent AS activity was assayed in a reaction volume of 1 mL, including 500 μL of column eluate. The reaction was performed at 32°C for 0 and 30 min and was terminated by the addition of 100 μL of 1 n HCl. The anthranilate produced was then extracted into 4 mL of ethyl acetate and was quantified with a spectrofluorometer (FP-777, JASCO, Tokyo; excitation, 338 nm; emission, 440 nm). The protein concentration of the column eluate was measured with a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) to calculate the specific activity of AS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Roy H. Doi for critical reading of the manuscript, Erin Yoshida and Makiko Kawagishi-Kobayashi for helpful discussions, and Satoko Miyauchi for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan for the Development of Next Generation Recombinant DNA Techniques.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bohlmann J, DeLuca V, Eilert U, Martin W. Purification and cDNA cloning of anthranilate synthase from Ruta graveolens: modes of expression and properties of native and recombinant enzymes. Plant J. 1995;7:491–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.7030491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann J, Lins T, Martin W, Eilert U. Anthranilate synthase from Ruta graveolens: duplicated ASα genes encode tryptophan-sensitive and tryptophan-insensitive isoenzymes specific to amino acid and alkaloid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:507–514. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri MG, Bauerle R. Identification of amino acid residues involved in feedback regulation of the anthranilate synthase complex from Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8328–8335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Brotherton JE, Song HS, Widholm JM. Increasing tryptophan synthesis in a forage legume Astragalus sinicus by expressing the tobacco feedback-insensitive anthranilate synthase (ASA2) gene. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:1069–1076. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Wang C, Sun C, Hsu C, Yin K, Chu C, Bi F. Establishment of an efficient medium for anther culture of rice through comparative experiments on the nitrogen sources. Scientia Sinica. 1975;18:223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo MJ, Luth D, Blankenship KM, Anderson OD, Blechl AE. Activity of a maize ubiquitin promoter in transgenic rice. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;23:567–581. doi: 10.1007/BF00019304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essar DW, Eberly L, Hadero A, Crawfold IP. Identification and characterization of genes for a second anthranilate synthase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: interchangeability of the two anthranilate synthases and evolutionary implications. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:884–900. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.884-900.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco SC, Guida T, Locke M, Mauvais J, Sanders C, Ward RT, Webber P. Transgenic canola and soybean seeds with increased lysine. Biotechnology. 1995;13:577–582. doi: 10.1038/nbt0695-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey M, Chomet P, Glawischnig E, Stettner C, Grün S, Winklmair A, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Meeley RB, Briggs SP. Analysis of a chemical plant defense mechanism in grasses. Science. 1997;277:696–699. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavel Y, von Heijne G. A conserved cleavage-site motif in chloroplast transit peptides. FEBS Lett. 1990;261:455–458. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80614-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist DG, Kosuge K. Aromatic amino acid biosynthesis and its regulation. In: Miflin BJ, editor. The Biochemistry of Plants: Amino Acids and Derivatives. Vol. 5. New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 507–531. [Google Scholar]

- Goto F, Yoshihara T, Shigemoto N, Toki S, Takaiwa F. Iron fortification of rice seed by the soybean ferritin gene. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:282–286. doi: 10.1038/7029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf R, Mehmann B, Braus GH. Analysis of feedback-resistant anthranilate synthases from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1061–1068. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1061-1068.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He DY, Yazaki Y, Nishizawa Y, Takai R, Yamada K, Sakano K, Shibuya N, Minami E. Gene activation by cytoplasmic acidification in suspension-cultured rice cells in response to the potent elicitor, N-acetylchitoheptaose. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:1167–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Hiei Y, Ohta S, Komari T, Kumashiro T. Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 1994;6:271–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6020271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood EE, Helmer GL, Fraley RT, Chilton MD. The hypervirulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens A281 is encoded in a region of pTiBo542 outside of T-DNA. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1291–1301. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1291-1301.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara A, Ohtsu Y, Iwamura H. Biosynthesis of oat avenanthramide phytoalexins. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kreps JL, Ponappa T, Dong W, Town CD. Molecular basis of α-methyltryptophan resistance in amt-1, a mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana with altered tryptophan metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:1159–1165. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.4.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Last RL. The Arabidopsis thaliana trp5 mutant has a feedback-resistant anthranilate synthase and elevated soluble tryptophan. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:51–59. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui K, Miwa K, Sano K. Two single-base-pair substitutions causing desensitization to tryptophan feedback inhibition of anthranilate synthase and enhanced expression of tryptophan genes of Brevibacterium lactofermentum. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5330–5332. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5330-5332.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melanson D, Chilton MD, Masters-Moore D, Chilton WS. A deletion in an indole synthase gene is responsible for the DIMBOA-deficient phenotype of bxbx maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13345–13350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog E. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassay with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol Plant. 1963;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa Y, Kawakami A, Hibi T, He DY, Shibuya N, Minami E. Regulation of the chitinase gene expression in suspension-cultured rice cells by N-acetylchitooligosaccharides: differences in the signal transduction pathways leading to the activation of elicitor-responsive genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;39:907–914. doi: 10.1023/a:1006161802334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi KK, Fink GR. Two anthranilate synthase genes in Arabidopsis: defense-related regulation of the tryptophan pathway. Plant Cell. 1992;4:721–733. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.6.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi KK, Last RL, Fink GR, Keith B. Suppressors of trp1 fluorescence identify a new Arabidopsis gene, TRP4, encoding the anthranilate synthase β subunit. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1011–1027. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.9.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nojiri H, Sugimori M, Yamane H, Nishimura Y, Yamada A, Shibuya N, Kodama O, Murofishi N, Omori T. Involvement of jasmonic acid in elicitor-induced phytoalexin production in suspension-cultured rice cells. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:387–392. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira K, Ojima K, Fujiwara A. Studies on the nutrition of rice cell culture: I. A simple, defined medium for rapid growth in suspension culture. Plant Cell Physiol. 1973;14:1113–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S, Mita S, Hattori T, Nakamura K. Construction and expression in tobacco of a β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene containing an intron within the coding sequence. Plant Cell Physiol. 1990;31:805–813. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen C, Bongaerts RJM, Verpoorte R. Purification and characterization of anthranilate synthase from Catharanthus roseus. Eur J Biochem. 1993;212:431–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwanski ER, Last RL. Tryptophan biosynthesis and metabolism: biochemical and molecular genetics. Plant Cell. 1995;7:921–934. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero RM, Roberts MF. Anthranilate synthase from Ailanthus altissima cell suspension cultures. Phytochemistry. 1996;41:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Song HS, Brotherton JE, Gonzales RA, Widholm JM. Tissue culture-specific expression of a naturally occurring tobacco feedback-insensitive anthranilate synthase. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:533–543. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.2.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S, Takamatsu S, Nojiri C, Ooba S, Anzai H, Iwata M, Christensen AH, Quail PH, Uchimiya H. Expression of a maize ubiquitin gene promoter-bar chimeric gene in transgenic rice plants. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1503–1507. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.3.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozawa Y, Tanaka K, Takahashi H, Wakasa K. Nuclear encoding of a plastid ς factor in rice and its tissue- and light-dependent expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:415–419. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urushibara S, Tozawa Y, Kawagishi-Kobayashi M, Wakasa K. Efficient transformation of rice suspension-cultured cells mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Breed Sci. 2001;51:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wakasa K, Widholm JM. A 5-methyltryptophan resistant rice mutant, MTR1, selected in tissue culture. Theor Appl Genet. 1987;74:49–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00290082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada A, Shibuya N, Kodama O, Akatsuka T. Induction of phytoalexin formation in suspension-cultured rice cells by N-acetylchitooligosaccharides. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Al-Babili S, Klöti A, Zhang J, Lucca P, Beyer P, Potrykus I. Engineering the provitamin A (β-carotene) biosynthetic pathway into (carotenoid-free) rice endosperm. Science. 2000;287:303–305. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Last RL. Immunological characterization and chloroplast localization of the tryptophan biosynthetic enzymes of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6081–6087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]