ABSTRACT

Background and Purpose

Goal setting is a key aspect of patient‐centered physiotherapy, helping to motivate patients, align healthcare efforts, prevent oversight, and stop ineffective interventions. This study aims to identify facilitators and barriers for physiotherapists in hospitals to set and document patient treatment goals.

Methods

An explanatory sequential mixed‐methods approach was used. The survey, informed by systematic reviews of factors influencing shared decision‐making and the theoretical domains framework (TDF), included 25 statements to be rated. Two focus groups (n = 8) discussed (1) factors from the survey, (2) the goal‐setting processes, and (3) brainstormed facilitators and barriers for documenting physiotherapy goals.

Results

Survey findings showed mixed opinions but agreement on two factors, which indicate that the goal influences the therapeutic interventions and motivates the therapists. The focus group identified four themes: “Goal,” “Physiotherapeutic Self‐Conception,” “Interprofessionality”, and “Hospital Setting.” Issues included limited space and poor placement in documentation systems, mental rather than written goal conceptualization, and a perceived lack of interest from interprofessional team members, leading to deprioritization by physiotherapists. Finally, joint goal setting was deemed impractical for certain patients.

Discussion

Hospital physiotherapists set treatment goals with their patients. The process is influenced by various factors, including interprofessional dynamics and the hospital setting. The identified themes align with existing literature. Effective documentation of patient‐centered physiotherapy goals in hospitals requires well‐designed tools and interprofessional collaboration. Further, it is crucial to understand professional self‐conception and acknowledge situations where physiotherapists need to set goals independently.

Keywords: goals, hospitals, physiotherapy

1. Introduction

Goal‐setting is an integral part of physiotherapeutic care. During their education, physiotherapists worldwide learn to set an overall treatment goal and break it down into subgoals (Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium 2017; World Physiotherapy 2021). Recent studies investigate the effect of patient‐centered goal‐setting to secure patient‐focused care (Langford et al. 2007; Mozafarinia et al. 2024). Furthermore, different methods and frameworks to set treatment goals have been developed and are currently implemented and evaluated in several healthcare settings (Melin et al. 2021; Pritchard‐Wiart, Thompson‐Hodgetts, and McKillop 2019; Swann et al. 2021). In the implementation process, the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) can be utilized to identify and address the facilitating and hindering behaviors of relevant actors (Atkins et al. 2017). A jointly set treatment goal between clinicians and patients supports personalized care and motivates patients (Langford et al. 2007; Mozafarinia et al. 2024). Additionally, if an interprofessional team agrees on a joint goal, it can align the healthcare team's efforts, prevent oversight of crucial actions, and facilitate the prompt cessation of ineffective interventions (Doornebosch, Smaling, and Achterberg 2022; Gagliardi, Dobrow, and Wright 2011; Rose 2011). Despite physiotherapists being educated on goal setting and the benefits of goal setting, there is some indication that physiotherapeutic goals are not routinely set and/or documented in physiotherapeutic care in several countries (Harman et al. 2009; Paim et al. 2022; Stevens et al. 2017). This is also true for Germany. Bimonthly extractions in 2023 of the electronic health record (EHR) of our physiotherapeutic department at a university hospital showed that a physiotherapeutic treatment goal was documented for just 7% of the patients on average per month. However, to the best of our knowledge, the existing literature only addresses facilitators and barriers in the clinical shared decision‐making process, not the specific context of physiotherapeutic goal‐setting (Waddell et al. 2021). Therefore, this study aims to identify facilitators and barriers for physiotherapists in a university hospital setting, influencing the process of setting and/or documenting a treatment goal.

2. Methods

We conducted our study at a German university hospital with 15,300 employees, including 80 physiotherapists, who care for 550,000 patients annually, including 95,000 inpatients. At this hospital, all patient documentation is organized in the EHR. We used an explanatory sequential mixed‐method approach, starting with a quantitative survey and validating the findings in qualitative focus groups.

2.1. Survey Study

2.1.1. Development of the Survey

The first part of the survey contains seven background questions, including the physiotherapist's sex and work experience. The core part builds on the findings of two systematic reviews (Lau et al. 2016; Waddell et al. 2021), one focusing on identifying factors influencing the successful implementation of evidence into practices (Lau et al. 2016) and the second focusing on influencing factors to shared decision‐making in hospitals (Waddell et al. 2021). The latter is based on the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (Atkins et al. 2017). These reviews were utilized to create statements for the survey study. We agreed on 25 statements to which the participants could “agree,” “partly agree,” “be neutral,” “partly disagree,” or “disagree.” They could also indicate that they did not want to reply. The first 19 statements focused on facilitators and barriers to joint goal‐setting. The last six statements focused on factors relating to the patient‐centered goal‐setting tool, which was designed in focus groups and is implemented in the hospital's EHR system. This tool is on the first page of the physiotherapeutic documentation and allows physiotherapists to document a “free‐text” goal for the stay, as defined by the patient. The survey statements were developed and discussed by four trained physiotherapists with research experience in several meetings; we secured that all identified facilitator and barrier categories from the two reviews were covered. Finally, the survey was tested using the “think out loud” method by two physiotherapists to secure the understandability and validity of the statements (Buber 2009). Consequently, minor wording changes were performed to improve understanding. Supporting Information S1 contains the final survey version.

2.1.2. Sample

All 64 physiotherapists at the university hospital, without additional inclusion criteria, were invited to participate in the survey, except for those working in the pediatric or intensive care units. At these units, the goal‐setting process differs, as goals are mostly not set with the patient (alone) but with the patient's legal guardian.

2.1.3. Data Collection and Analyses

During a regular monthly meeting in 2022, the survey was distributed on paper to the physiotherapist, and a reminder was sent via email two weeks later. We present the survey data descriptively and utilized Excel and R Version 2023.12.1+402 to perform the analyses.

2.2. Qualitative Focus Group Discussion Study

To present the focus group discussion findings, we follow the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig 2007).

2.2.1. Research Team and Reflexibility

The physiotherapists S.K. and L.B. conducted the focus group interviews. Both have years of experience as physiotherapists and health researchers in quantitative and qualitative research. S.K. has worked in the physiotherapy department for 10 years as a colleague of the participants. L.B. is affiliated with another department and did not know any of the participants. L.B. and S.K. briefly introduced themselves and their backgrounds at the beginning of the focus groups. Afterward, L.B. led the discussions while S.K. supported her but otherwise stayed in the background.

2.2.2. Participant Selection

Participants were recruited during a monthly physiotherapy department meeting in 2023. Interested physiotherapists registered on a list at the meeting or in the following weeks. No additional inclusion criteria were applied. Participants were split into two discussion groups to form two balanced groups regarding age and work experience. One participant got sick and did not participate.

2.2.3. Setting

Both focus group interviews were conducted in a “teaching room” at the university hospital. S.K. and L.B. guided the interviews. L.B. moderated and facilitated the discussion, while S.K. supported the facilitation and took field notes. No one else attended the focus groups.

2.2.4. Data Collection and Analyses

An interview guide was created prior to the focus group discussions (Supporting Information S2) with three parts focusing on (1) discussing two identified factors from the survey, (2) describing the goal‐setting process, and (3) brainstorming facilitators and barriers for documenting treatment goals.

The focus group discussions were audiotaped. Materials used to visualize goal‐setting (Supporting Information S3) and notecards with identified facilitators and barriers were collected. The audiotapes were transcribed using the f4x software and cross‐checked by W.F.

S.K. and L.B. used an inductive approach to analyze the focus group interviews. They independently analyzed the transcripts, discussed their identified themes, and grouped them into main subthemes. These themes were then mapped to the TDF domains. W.F. translated key quotations into English, which were reviewed and revised by L.B. and S.K. and back‐translated into English by a native English speaker before inclusion in this manuscript. The original quotes in German and their translation in English can be found in Supporting Information S4. Finally, the results were presented to all practicing physiotherapists, including the participants of the study at the university hospital, with room for discussion.

3. Results/Findings

3.1. Survey Study

Eight physiotherapists participated in the survey, six of whom were female (75%) with 22–31 years of experience. They treated patients in orthopedic, surgical, neurological, oncological, and internal medical units. They reported to set treatment goals for 5%–90% (mean 68%) and documenting them for 0%–90% (mean 47%) of their patients.

There was agreement on two statements: (1) the goal influences the therapeutic interventions and (2) therapists are motivated by the goal. Conflicting responses were observed for all the remaining statements. Details can be found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the survey results.

| Statement | Response (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) I disagree | ||||||

| (2) I rather disagree | ||||||

| (3) Partly, partly | ||||||

| (4) I rather agree | ||||||

| (5) I agree | ||||||

| (6) I can not/do not want to answer | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| (1) I have the opportunity to set/discuss a goal with patients undisturbed | 1 | — | 2 | 2 | 3 | — |

| (2) I record the treatment goal during the initial contact | — | — | 3 | 1 | 4 | — |

| (3) I set the treatment goal for the patients | — | 2 | 5 | 1 | — | — |

| (4) It is important to record treatment goals in writing | — | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | — |

| (5) I find the physiotherapeutic treatment more important than physiotherapeutic goal setting in the hospital | 3 | 1 | 3 | — | 1 | — |

| (6) I take my time for goal setting | — | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | — |

| (7) I set the treatment goal together with the patients | — | — | 3 | 2 | 3 | — |

| (8) During decision‐making, I am on equal terms with the patients | — | — | 1 | 2 | 5 | — |

| (9) The patients have realistic ideas regarding the goals | — | 2 | 4 | 2 | — | — |

| (10) Relatives have an influence on the goals of the patients | — | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | — |

| (11) My colleagues from other professions tell me what the treatment goal is | 2 | 2 | 4 | — | — | — |

| (12) The information gathered through goal setting influences the treatment content | — | — | — | 3 | 5 | — |

| (13) It motivates me when I work toward a goal with patients | — | — | — | 3 | 5 | — |

| (14) Patients with whom I have jointly set a treatment goal are more motivated in treatment | — | — | 4 | 3 | 1 | — |

| (15) I receive feedback from patients regarding goal setting | 1 | — | 4 | 2 | 1 | — |

| (16) Once a goal is set, it can have an impact on the lives of patients beyond their hospital stay | — | — | 4 | 4 | — | — |

| (17) Patient goal setting is part of the culture at your hospital | 1 | 1 | 4 | — | 2 | — |

| (18) I have an understanding of the complexity of goal setting | — | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | — |

| (19) I would like to learn more about effective goal setting | 1 | — | 1 | 3 | 3 | — |

| (20) It is easy to find the goal‐setting questions in the documentation system | — | 1 | — | 4 | 3 | — |

| (21) It was explained to me how the goal‐setting questions should be used | 3 | — | — | 2 | 3 | — |

| (22) I would like to have a different goal‐setting question to document goals for patients a | 2 | 2 | 2 | — | — | 1 |

| (23) I have had good experiences with the goal‐setting questions a | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | — |

| (24) There is sufficient effort from the physiotherapy management team to use the goal‐setting questions | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | — | — |

| (25) Treatment goals that I have written down are also of interest to the other professions | — | — | 3 | 2 | 3 | — |

One participant did not respond.

3.2. Qualitative Focus Group Discussion Study

Two approximately one‐hour lasting focus groups with eight physiotherapists in total were conducted to verify and deepen the findings of the survey study. Six participants were female (75%), with professional experience ranging from 15 to 40 years (median 32 years). Their primary fields included intensive care, internal medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, orthopedics, and psychiatry.

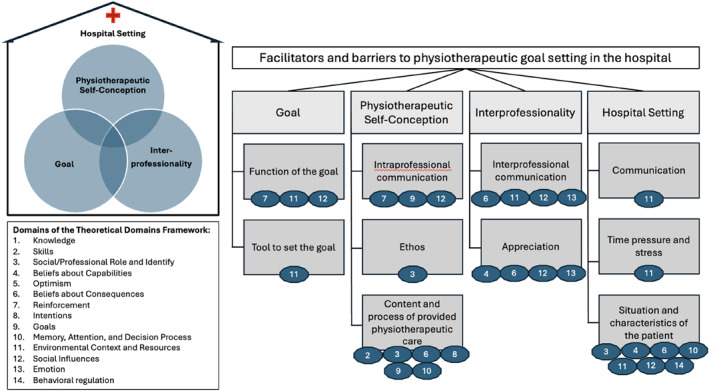

Our inductive analyses yield four main themes “Goal”, “Physiotherapeutic Self‐Conception”, “Interprofessionality”, and “Hospital Setting”. The three former main themes overlap, while the final “Hospital Setting” encompasses them and sets the overall context, as visualized by the house symbol in Figure 1. Additionally, Figure 1 shows our 10 subthemes grouped under our main themes.

FIGURE 1.

Link between the main themes of the facilitators and barriers identified in the focus group and their sub‐themes, including an indication of the areas of TDF that are covered.

3.2.1. “Goal”

The codes of this main theme were divided into two subthemes “Function of the goal” and “Tool to set the goal”.

Physiotherapists indicated that the goal and method influence goal‐setting. Participants described that developed and measured goals can motivate or demotivate both themselves and the patients.

And then we were both frustrated after two weeks because we couldn't measure the goals. […] And then I learned to develop better goals […] with the patient.

[18_PT4_00:39:45]

Furthermore, a participant indicated that medical doctors set discharge goals, influencing the physiotherapeutic goal‐setting process.

The second subtheme involves the documentation system, which was identified as a barrier to documenting goals. The designated field for physiotherapeutic goals is too small and lacks space for updates. Additionally, it is placed at the beginning, where physiotherapists typically do not make entries, so they often skip directly to the treatment documentation site.

We don't enter anything upfront, […] and then you automatically click on [the next page for the documentation of the] treatment.

[18_PT5_00:11:18]

Finally, physiotherapists suggested adding goal suggestions as selectable text blocks in the software to facilitate documentation.

3.2.2. “Physiotherapeutic Self‐Conception”

This main theme included three subthemes: “Content and process of the provided physiotherapeutic care”, “Ethos”, and “Intraprofessional communication”.

Some participants perceived physical activity as an inherent goal of physiotherapy, so they felt it did not need to be documented.

I think mobility is a goal anyway. That's in the back of my mind; you don't write it down all the time.

[18_PT3_00:44:23]

Furthermore, they mentioned that the goal was often in their head, and they only documented actions taken to achieve it. Additionally, they noted having daily, weekly, and treatment goals to reach during the physiotherapeutic process.

Patient inclusion in the goal‐setting process varied according to the physiotherapeutic ethos. Some participants see it as important, supporting an active patient role, but recognize challenges in patient participation. It was also acknowledged that, in the past, physiotherapists were taught to set goals for the patient.

But it was learnt in the past that as a therapist you set treatment goals…

[18_PT2_00:42:32]

Another code under the “Ethos” subtheme addresses why the treatment goal is documented. One participant emphasized that documenting the treatment goal is part of professional self‐conception, regardless of its value to other professions.

Communicating with the patient was another challenge mentioned for goal‐setting. The patient's communication ability and unrealistic treatment expectations can complicate the process. However, adjusting these unrealistic expectations was assumed to be part of the physiotherapist's duties.

Well, ultimately it's about communicating with the patient about these perhaps not entirely realistic goals.

[19_PT4_00:15:18]

However, a participant mentioned feeling guilty when “not doing” something with the patient, indicating that talking and adjusting patients' unrealistic goals is not seen as a duty by all physiotherapists.

Nevertheless, goal‐setting was deemed part of the physiotherapist's responsibility and important for treatment planning and execution. Setting a physiotherapeutic goal allows for more purposeful treatment. However, communication within the physiotherapy team about the goal is needed to coordinate and harmonize care.

It would be good if all therapists… are working towards the same goal. … For that, of course, it's good if it's written down somewhere and somehow visible to everyone.

[19_PT6_00:30:32]

3.2.3. “Interprofessionality”

Under the theme “Interprofessionality,” two interconnected subthemes emerged: “Interprofessional communication” and “Appreciation.” Physiotherapists expressed a need for regular interprofessional communication for high‐quality patient care and effective goal‐setting. A related challenge highlighted was that sometimes doctors provide contradictory instructions regarding post‐surgical weight bearing, which, according to the participants, made it difficult to establish clear goals. An interprofessional goal was considered valuable.

…whether you might achieve something better with a common goal … if you work together towards a common goal, it is certainly more effective than if each profession sets its own goal without communicating with the other and also communicating with the patient.

[19_PT6_00:44:18]

In addition, communication between professions and knowledge of each other's goals were seen as appreciating and motivating for goal‐setting and documentation. However, participants assumed that medical doctors and nurses did not know where to find physiotherapists' documentation and that this information had no impact on the overall treatment process.

The things we write down, I always feel like nobody reads them anyway. … I think that's another frustration. … A lot of times you don't feel like taking the time to write it down properly because you feel like it's all for the birds anyway.

[18_PT4_00:13:27]

3.2.4. “Hospital Setting”

The “Hospital Setting” influences the physiotherapeutic process and goal‐setting. According to the participating physiotherapists, “Time pressure and stress,” “Communication,” and “Situation of the patients and their characteristics” were identified as three subthemes. The participants mentioned perceived lack of time as a barrier to goal‐setting and documentation.

But it's also often the case, we need to document at the hospital ward, do it quickly and then you don't have time. That's just another time issue. And then you have to decide, no, I'll do that, I'll fill it in properly now. It takes time and energy.

[18_PT4_00:12:06]

Regularly scheduled meetings with physiotherapy colleagues to discuss patients, challenges, and the physiotherapeutic process could facilitate goal‐setting. This was reported by one participant and desired by others in the focus groups.

We physiotherapists, exactly. Always at a quarter to 9 is the handover, where we sit there with five wards and simply exchange information. When there are questions about setting goals, we clarify them among ourselves.

[19_PT5_00:49:11]

Patients in the university hospitals often have complex health issues influencing goal‐setting. Physiotherapists stated that these issues might hinder patient engagement in goal‐setting. One challenge is the fluctuating health status, making it difficult for both patients and physiotherapists to determine goals. Rapid changes in health may require setting new goals daily or prioritizing other goals.

Well, quite often, especially in the intensive care unit, it's difficult to weigh things up. Where is the journey going? It can go this way or the other.

[19_PT4_01:00:35]

Moreover, patients' health conditions might prevent them from interacting with physiotherapists, affecting the goal‐setting process. Even when interaction is possible, participants sometimes find goal‐setting difficult due to patients’ expectations and preferences.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Results

Our focus group discussions confirmed indications from the survey that treatment goals influence the treatment and motivate the therapists. However, while the survey indicate that no other goal‐setting tool was needed, the focus groups highlighted limitations in the tool's location and available space. We identified four main themes influencing the physiotherapeutic goal‐setting process at a university hospital: “Goal”, “Physiotherapeutic Self‐Conception”, “Interprofessionality”, and “Hospital Setting”.

4.2. Comparison to Existing Literature

Our identified factors sometimes influence the process of documenting a treatment goal and sometimes the goal‐setting process itself. Setting a treatment goal is a prerequisite for documenting it. While goal‐setting can be intuitive, documentation requires awareness. Theoretical frameworks can help with both processes, but they are particularly supportive for concise documentation (Angeli et al. 2021; Scobbie, Dixon, and Wyke 2011). Regardless of whether they relate to goal‐setting or documentation, the influencing factors identified for the physiotherapeutic goal‐setting process match those in the literature (Waddell et al. 2021). Time and stress in the hospital setting are already known as barriers to shared decision‐making, including joint goal‐setting and communication and interprofessional teamwork are also known influencing factors for patient‐centered and effective care provision (Waddell et al. 2021).

4.3. Interpretation and Comparison to the TDF

Investigating whether our identified themes match the TDF facilitators and barriers, we found that our themes and subthemes could not be grouped into a single TDF domain. Instead, our subthemes could be categorized under multiple domains depending on the observer's perspective. Finally, the following four TDF domains were not included in our focus group discussions: “Knowledge”, “Skills”, “Optimism”, and “Behavioral Regulation.”

Most codes of our main theme “Goal” can be categorized under the TDF domain “Environmental Context and Resources.” In particular, the tool, its location, and its design belong to the environmental context. The subtheme “Function of the Goal” could be categorized under “Reinforcement” since the participants mentioned that a well‐defined and documented goal was motivating. However, it could also be categorized under “Environmental Context and Resources“ or “Social Influences” since medical doctors provided their goals influencing the physiotherapeutic goal‐setting process.

The codes of “Physiotherapeutic Self‐Conception” addressed several TDF domains. Some codes of the subtheme “Content and Process of Provided Care” belong to the “Social and Professional Role” as when the participants intrinsically understand physical activity as a goal. However, they could also be grouped under the domain “intentions” since a participant described their process of setting a goal in the head and planning to document what was done during the therapy session.

The codes from “Interprofessionality” were categorized under the TDF domains “Emotions,” “Social Influences,” and “Beliefs about Consequences.” The feeling of frustration, when the documentation is not utilized was, for example categorized under “Emotions”. However, following the participant's assumption that the interest in other professions would increase the motivation to document, the subtheme “Appreciation” could also be categorized as “Beliefs about Consequences”. The subtheme “Interprofessional Communication” has codes belonging to the “Environmental Context,” “Social Influence,” “Emotions,” and “Beliefs about Consequences” domains of the TDF.

The subthemes in the “Hospital Setting” were often categorized under “Memory, Attention, and Decision Process,” but the domains of “Behavioral Regulation,” “Beliefs about Capabilities,” “Environmental Context and Resources,” “Professional and Social Role,” and “Social Influence” could also be found among the codes. The subthemes “Communication” and “Time Pressure and Stress” were seen as belonging solely to the “Environmental Context and Resource” domain.

4.4. Generalizability

The generalizability of our findings might be limited due to the small sample size and the fact that the study was conducted in one German university hospital with very experienced physiotherapists. German physiotherapy education is unique in the EU, being mostly non‐academic, which may affect “physiotherapeutic self‐conception” findings. Thus, our findings should be validated in larger national and international studies. Furthermore, they might not be generalized to settings where the goal is not set directly with the patients, as in pediatric care and intensive care units as the physiotherapists from these units were excluded from the present study. Nonetheless, our results might guide researchers and clinicians in other hospitals in evaluating relevant facilitators and barriers to goal‐setting. Since facilitators and barriers vary by setting, depending on the intervention, external context, professionals, and organization, they must be evaluated specifically (Lau et al. 2016). Our detailed pragmatic approach can help identify setting‐specific influencing factors.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

Though we respected factors identified in previous literature, the reliability of specific statements remains uncertain. To address this, we used the think‐out‐loud method before the survey and validated our findings in focus group discussions. Further, testing and validating the interview questions prior to the focus groups could have further improved our methodological quality. The translation of quotations could have been improved with forward and backward translation. However, our study provides the first insights into validated factors influencing the physiotherapeutic goal‐setting process in a university hospital setting.

One limitation of our study, which might also influence the generalizability, is the small sample size and the limited response of particularly unexperienced physiotherapists. Therefore, it is important that our findings are validated in future studies. Furthermore, the impact of our findings could be tested in future studies, for example how time pressure or different perceived self‐conceptions influence the length and quality of the documented goals. Finally, future studies could also focus on the interplay between goal‐setting and different documentation systems, which might support or hinder the goal‐setting process.

Additionally, some factors influencing the goal‐setting process are challenging to identify via surveys or focus groups, such as a lack of knowledge. We observed that while physiotherapists mentioned different types of goals, they did not conceptualize them as physiotherapeutic or medical doctor goals. Valued‐based goals were implied but not named, and the only theoretical approach mentioned was SMART goals. This lack of knowledge is hard to identify since participants may be unaware of additional knowledge on the goal‐setting process, and hence cannot articulate it as a barrier. This is reflected by the absence of a subtheme “knowledge” in the results as we have applied an inductive approach of coding. Our categories and subthemes are grounded in the data and supported by quotations from the participants. A subtheme “knowledge” could not be identified in the material as it was not recognized and named as an influencing factor. Nevertheless, to address this potential barrier, it should be covered in educational sessions for physiotherapists.

5. Implications of Physiotherapy Practice

We identified several factors influencing the goal‐setting and documentation process of physiotherapists working at a university hospital. These factors are at the professional level and relate to physiotherapeutic self‐conception. Thus, they could be best addressed in professional or further education. Additional factors related to the present documentation tool were at the organizational level. Tool adjustments and changes in the organizational processes can address them. When implementing and using goal setting in clinical practice, it is important to consciously decide on and use the different functions (e.g. motivation) and dimensions (e.g. time or hierarchies in goals) of goals to benefit from the full potential of goal setting. It should also address and involve interdisciplinary staff and respect the influence of the setting on the goal‐setting process.

Author Contributions

L.B.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. W.F.: methodology, formal analysis, writing–review and editing. F.G.: methodology, formal analysis, writing–review and editing. H.H.K.: methodology, writing–review and editing. A.H.: conceptualization, methodology, writing–Review and editing. S.K.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for our application “LPEK‐0452” was granted by the local ethical committee of the psychologist at the University Medical Center Hamburg‐Eppendorf on the eighth of March 2022.

Consent

All participants gave written informed consent before data collection began.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare any conflicts of interest.

Permission to Reproduce Material From Other Sources

Not applicable.

Supporting information

Supporting Information S1

Supporting Information S2

Supporting Information S3

Supporting Information S4

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Funding: A grant from the German Society for Physiotherapy Science (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Physiotherapiewissenschaften DGPTW) supported this project.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets of the current study might be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Angeli, J. M. , Schwab S. M., Huijs L., Sheehan A., and Harpster K.. 2021. “ICF‐Inspired Goal‐Setting in Developmental Rehabilitation: An Innovative Framework for Pediatric Therapists.” Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 37, no. 11: 1167–1176. 10.1080/09593985.2019.1692392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, L. , Francis J., Islam R., et al. 2017. “A Guide to Using the Theoretical Domains Framework of Behaviour Change to Investigate Implementation Problems.” Implementation Science: IS 12, no. 1: 77. 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buber, R. 2009. “Denke‐Laut‐Protokolle.” In Qualitative Marktforschung, 555–568. Wiesbaden: Gabler. 10.1007/978-3-8349-9441-7_35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doornebosch, A. J. , Smaling H. J. A., and Achterberg W. P.. 2022. “Interprofessional Collaboration in Long‐Term Care and Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review.” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 23, no. 5: 764–777.e2. 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi, A. R. , Dobrow M. J., and Wright F. C.. 2011. “How Can We Improve Cancer Care? A Review of Interprofessional Collaboration Models and Their Use in Clinical Management.” Surgical Oncology 20, no. 3: 146–154. 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman, K. , Bassett R., Fenety A., and Hoens A.. 2009. “‘I Think it, but Don’t Often Write it’: The Barriers to Charting in Private Practice.” Physiotherapy Canada 61, no. 4: 252–258. 10.3138/physio.61.4.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford, A. T. , Sawyer D. R., Gioimo S., Brownson C. A., and O’Toole M. L.. 2007. “Patient‐Centered.” Diabetes Educator 33, no. S6: 139S–144S. 10.1177/0145721707304475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, R. , Stevenson F., Ong B. N., et al. 2016. “Achieving Change in Primary Care—Causes of the Evidence to Practice Gap: Systematic Reviews of Reviews.” Implementation Science: IS 11, no. 1: 40. 10.1186/s13012-016-0396-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melin, J. , Nordin Å., Feldthusen C., and Danielsson L.. 2021. “Goal‐Setting in Physiotherapy: Exploring a Person‐Centered Perspective.” Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 37, no. 8: 863–880. 10.1080/09593985.2019.1655822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozafarinia, M. , Mate K. K. V., Brouillette M.‐J., Fellows L. K., Knäuper B., and Mayo N. E.. 2024. “An Umbrella Review of the Literature on the Effectiveness of Goal Setting Interventions in Improving Health Outcomes in Chronic Conditions.” Disability and Rehabilitation 46, no. 4: 618–628. 10.1080/09638288.2023.2170475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium . 2017. Rahmenrichtlinien für die Ausbildung im Bereich Physiotherapie. Hannover: Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium. https://www.nibis.de/nli1/bbs/archiv/rahmenrichtlinien/physio.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Paim, T. , Low‐Choy N., Dorsch S., and Kuys S.. 2022. “An Audit of Physiotherapists’ Documentation on Physical Activity Assessment, Promotion and Prescription to Older Adults Attending Out‐Patient Rehabilitation.” Disability and Rehabilitation 44, no. 8: 1537–1543. 10.1080/09638288.2020.1805644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard‐Wiart, L. , Thompson‐Hodgetts S., and McKillop A. B.. 2019. “A Review of Goal Setting Theories Relevant to Goal Setting in Paediatric Rehabilitation.” Clinical Rehabilitation 33, no. 9: 1515–1526. 10.1177/0269215519846220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, L. 2011. “Interprofessional Collaboration in the ICU: How to Define?” Nursing in Critical Care 16, no. 1: 5–10. 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2010.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scobbie, L. , Dixon D., and Wyke S.. 2011. “Goal Setting and Action Planning in the Rehabilitation Setting: Development of a Theoretically Informed Practice Framework.” Clinical Rehabilitation 25, no. 5: 468–482. 10.1177/0269215510389198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, A. , Köke A., van der Weijden T., and Beurskens A.. 2017. “Ready for Goal Setting? Process Evaluation of a Patient‐specific Goal‐Setting Method in Physiotherapy.” BMC Health Services Research 17, no. 1: 618. 10.1186/s12913-017-2557-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann, C. , Rosenbaum S., Lawrence A., Vella S. A., McEwan D., and Ekkekakis P.. 2021. “Updating Goal‐Setting Theory in Physical Activity Promotion: A Critical Conceptual Review.” Health Psychology Review 15, no. 1: 34–50. 10.1080/17437199.2019.1706616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury P., and Craig J.. 2007. “Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32‐Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups.” International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care/ISQua 19, no. 6: 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell, A. , Lennox A., Spassova G., and Bragge P.. 2021. “Barriers and Facilitators to Shared Decision‐Making in Hospitals From Policy to Practice: A Systematic Review.” Implementation Science: IS 16, no. 1: 74. 10.1186/s13012-021-01142-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Physiotherapy . 2021. Physiotherapist Education Framework. London: World Physiotherapy. https://world.physio/sites/default/files/2021‐07/Physiotherapist‐education‐framework‐FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information S1

Supporting Information S2

Supporting Information S3

Supporting Information S4

Data Availability Statement

The datasets of the current study might be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.