Abstract

Background

The anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (anti-MDA5) antibody-positive dermatomyositis is known for its association with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease (RP-ILD) and ulcerative skin lesions, often presenting with or without muscle involvement. The aim of this study was to identify distinct clinical and laboratory features that could be used to evaluate disease progression in an ethnically diverse cohort of anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis patients at a U.S. academic center.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was conducted on dermatomyositis patients hospitalized at our institution between January 2014 and June 2023. The data were analyzed via Fischer’s exact test and a t test.

Results

Among the 195 dermatomyositis patients reviewed, 22 tested positive for the MDA5 antibody, comprising of thirteen adults and nine pediatric patients. Myositis was significantly more common in pediatric patients than in adult patients (p = 0.002). RP-ILD was more frequently observed in adult patients of African ancestry (including both Black Hispanic and Black non-Hispanic individuals) (p = 0.04). There was a significant association noted between Raynaud’s phenomenon and ILD (p = 0.02). The overall mortality rate of 13.6% was more favorable than the previously reported rates of 40–60%.

Conclusion

This study enhances our understanding of the disease by emphasizing potential racial and demographic variations, as well as delineating the similarities and differences between adult and pediatric populations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41927-025-00455-5.

Keywords: MDA5 autoantibody, Dermatomyositis, Race & ethnicity, Interstitial lung disease

Background

Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (anti-MDA5) antibody-positive dermatomyositis is an idiopathic inflammatory musculoskeletal disorder that is relatively rare and challenging to diagnose. The key distinguishing features include clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM) or hypomyopathic disease, characteristic deep skin ulcerations over joints often mirroring typical dermatomyositis lesions (Heliotrope rash, Gottron sign, Gottron papules, and Holster sign), and frequently rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease (RP-ILD) [1]. These features help differentiate it from other forms of dermatomyositis, including anti-synthetase syndrome, which is more likely to present with Raynaud’s phenomenon, mechanic’s hands, and anti-synthetase autoantibodies [2]. Patients may also exhibit nonspecific symptoms such as inflammatory arthritis, fever, fatigue, and weight loss, which are common in other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies [3, 4].

The association of RP-ILD myositis with antibodies against MDA5 (encoded by the gene interferon-induced helicase C domain [(IFIH]-containing protein 1) was first identified in a Japanese cohort, initially labeled anti-CADM 140 (anticlinically amyopathic dermatomyositis 140 kDa peptide), which was later recognized to share specificity with anti-MDA5 [5, 6]. While initially thought to be more prevalent in Asian populations, recent data indicate rising incidence rates in Europe and the U.S. across all ethnicities [7–9]. Notably, there is significant variability in disease presentation among ethnic groups, with a higher ILD risk observed in Asians, even in pediatric patients [10, 11]. RP-ILD, which is resistant to standard immunosuppressive therapy, is the primary cause of mortality in this population. The presence of anti-MDA5 antibodies has a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 86% for RP-ILD development [12], with associated 6-month mortality rates ranging from approximately 40–60% [13–16]. Early aggressive therapy and potential lung transplants have improved survival outcomes [1, 17]. Therefore, early clinical diagnosis is essential, particularly because anti-MDA5 autoantibody testing is not available in most centers and must be sent to a reference laboratory, resulting in processing delays that can hinder timely laboratory confirmation.

While early studies focused on Asian cohorts, information on disease presentation in diverse U.S. populations remains limited. Our study aimed to identify distinct clinical and laboratory features for assessing disease progression in individuals with anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis on the basis of serologic, histopathological, and radiographic status to aid in early diagnosis and treatment. We analyzed and compared the disease phenotypes of a racially diverse population of both juvenile and adult patients with anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis.

Methods

Following Institutional Review Board approval, we accessed the electronic health records at Montefiore Medical Center, NY, via Epic Systems Corporation (Verona, WI, USA; 2022). Our search identified 195 dermatomyositis patients based on ICD coding. Twenty two of these tested positive for anti-MDA5 autoantibodies between January 2014 and June 2023 and were included in the final analyses. A retrospective chart review of both inpatient and outpatient records was conducted to extract clinical data. This included demographic data such as age at encounter with our department, age at diagnosis, and race; comorbidities including malignancies and smoking status; signs and symptoms at presentation; serological markers, radiographic details, and treatment used. Skin rashes were characterized through physical exam findings, nail fold capillaroscopy and/or biopsy based on clinical need. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) was confirmed through high-resolution computed tomography of the thorax. Myositis was identified through physical exam, muscle enzymes, and/or through biopsy. Adult patients were subjected to anti-MDA5 antibodies (CADM-140) testing as part of the Myomarker Panel (Reporting Detection Limit by the Laboratory Corporation of America, Burlington, NC, USA) which uses Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The pediatric patients’ myositis-specific antibody testing was performed by the Oklahoma Myositis Testing Laboratory in Oklahoma City, OK, USA which used immunoprecipitation-blotting methods for detection. Patients were followed from initial encounter with our rheumatology department up to June 2023 or until they were lost to follow up, whichever occurred first.

Fischer’s exact test and two sample t test were used to compare disease features between adult and pediatric patients with anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted via Statistical Analysis System software version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

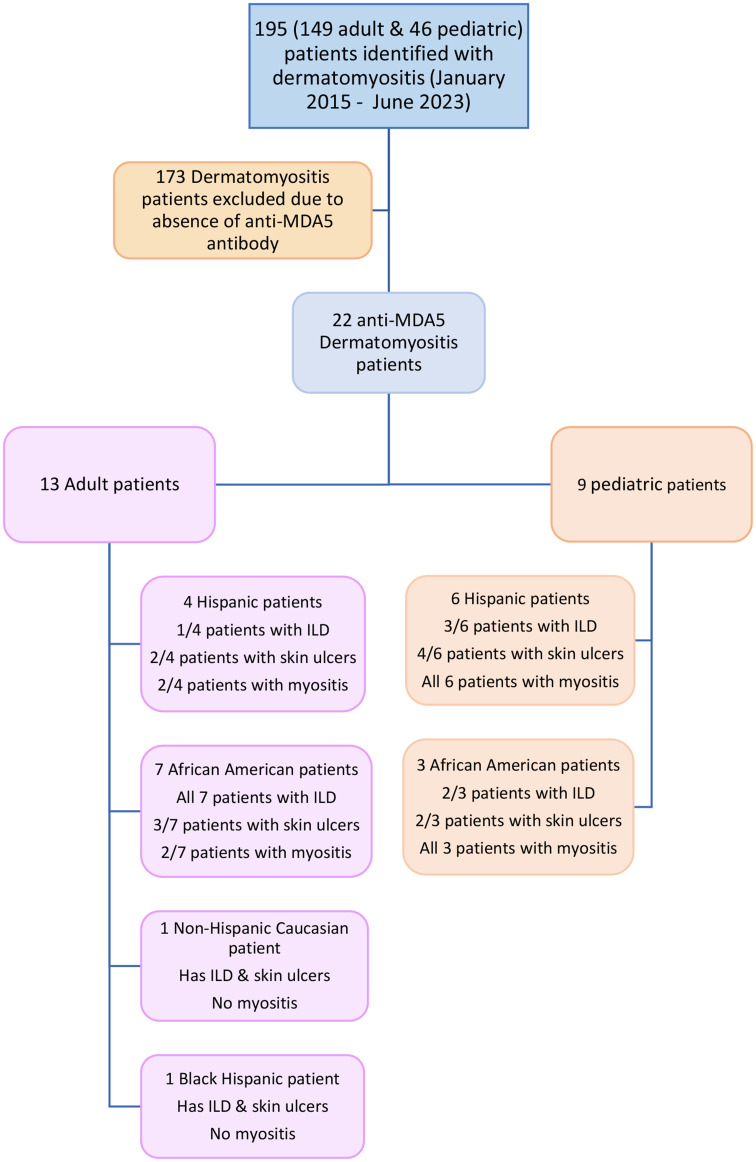

Among the 195 dermatomyositis patients reviewed, 22 tested positive for anti-MDA5 autoantibodies. The group comprised 13 adult patients (8.7% of all adult patients; 13/149) and 9 pediatric patients (19% of pediatric patients; 9/46), with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 2:1 in both groups. The median age for adult-onset DM was 40 years (Q1 35 years, Q3 61.5 years), with a mean follow-up duration of 2.40 years (SD 1.95 years). The median age of onset in children was 5 years (Q1 2.5 years, Q3 10 years). Among adults, the majority were African American (53.8%), followed by non-Black Hispanic (30.8%), Black Hispanic (7.7%), and Caucasian (7.7%) (Table 1; Supplementary Table 1). In the pediatric group, three African Americans (33.3%) and six nonblack Hispanics (66.6%) were included (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Study patient characteristics

| Adult MDA5 Dermatomyositis N = 13 |

Pediatric MDA5 Dermatomyositis N = 9 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at disease onset Years, (SD) | 44.6 (13.9) | 6.5 (4.9) | |

| Sex (Male, Female) | 5,8 | 3,6 | ns |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 1 | 0 | |

| Hispanic | 4 | 6 | 0.50 |

| African American | 7 | 3 | |

| Black Hispanic | 1 | 0 | |

| ILD | |||

| Absent | 3 | 4 | |

| Stable ILD | 7 | 4 | 0.61 |

| RP-ILD | 3 | 1 | |

| Skin ulcers | 7 | 6 | 0.67 |

| Arthritis | 9 | 7 | ns |

| Myositis | 4 | 9 | 0.002 |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 8 | 3 | 0.39 |

| ANA | 6 | 4 | ns |

| Ro 52 | 8 | 3 | 0.39 |

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing study population. Anti-MDA5: Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5; ILD: Interstitial lung disease

Skin rash was the most common symptom at presentation in adults, followed by dyspnea and inflammatory arthritis (Supplementary Table 1). In pediatric patients, muscle weakness was the predominant presenting symptom (9/9 pediatric patients vs. 4/13 adult patients; p = 0.002), although all of them presented with skin manifestations at some stage during the disease course. (Table 1; Supplementary Table 2).

Ten adult and five pediatric patients presented with interstitial lung disease (ILD). Among adult patients, ILD was significantly more prevalent in the Black Hispanic and African American populations (100% vs. 40% in other ethnic groups; p = 0.035). However, this difference was not detected when the entire cohort of adult and pediatric patients was considered (p = 0.064) (Tables 1 and 2). Of the four cases of RP-ILD, three involved African American patients (2 adults, 1 child) and one involved a Black Hispanic patient (1 adult). The group experienced a high mortality rate of 75%.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients by race/ethnicity

| Study characteristic | Hispanic (N = 10) | Race/Ethnicity | Black Hispanic (N = 1) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American (N = 10) | Non-Hispanic White (N = 1) | ||||

| ILD | |||||

| Absent | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Stable | 4 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0.06§ |

| RP-ILD | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0.04* |

| Myositis | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.28 |

| Skin ulcers | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.81 |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.67 |

| Arthritis | 8 | 7 | 1 | 0 | ns |

| ANA | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.81 |

| Ro 52 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | ns |

Note * - Black Hispanic or African American compared to other for ILD among the adult patients only; § - Black Hispanic or African American compared to other for ILD among the adult and pediatric patients

The presence of the anti-Ro52 antibody was noted in all adult RP-ILD patients but did not significantly differ across the entire cohort (Supplementary Tables 1 and 3). Data was adjusted for missing values. Raynaud’s phenomenon was associated with the presence of ILD (p = 0.02) (Table 3), whereas skin ulcers were not (p = 0.38) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship of ILD to clinic and laboratory characteristics

| ILD, N = 15 | No ILD, N = 7 | P value | RP-ILD, N = 4 | Stable/No ILD, N = 18 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin ulcers | 10(66.7%) | 3(42.9%) | 0.38 | 1(25%) | 12(66.7%) | 0.26 | |

| Raynaud’s | 10(71.4%) | 1(14.3%) | 0.02 | 1(33.3%) | 10(55.6%) | 0.59 | |

| Ro 52 | 8(53.3%) | 3(42.9%) | ns | 3(75%) | 8(44.4%) | 0.59 |

Although MDA5 dermatomyositis is not strongly linked to malignancy [18], two adult patients had ovarian malignancies. The overall mortality rate of 13.6% in our cohort was lower than the reported rate of 40–60% [19].

Mycophenolate was the preferred Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drug (DMARD), followed by Rituximab and Intravenous Immunoglobulin therapy (IVIG) in adults (Supplementary Table 3). Some uncommon DMARDs that were tried in adults included tacrolimus, leflunomide and azathioprine.

Methotrexate was the primary choice of DMARD in pediatric patients, with Rituximab being a common alternative (Table 1; Supplementary Table 4). Common agents used for treating pediatric disease included steroids, methotrexate, mycophenolate, IVIG, rituximab, and hydroxychloroquine. Less common agents that were tried include dapsone and cyclophosphamide (used for cardiac involvement). For ILD, the preferred agents of choice were Rituximab and Mycophenolate mofetil in our cohort (Supplementary Tables 2 and 4).

Discussion

Anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis is a relatively rare condition that can be difficult to diagnose. It has been reported to affect both sexes at a female-to-male ratio of 2:1, which is consistent with our population demographics [7, 20]. In this study, we aimed to define disease characteristics in a diverse adult and juvenile U.S. patient population to help with early disease identification and treatment, leading to improved outcomes. Overall, we found that the disease characteristics were similar between adult and pediatric patients, except for a higher prevalence of myositis in the pediatric group, as noted in other studies [18].

Additionally, the pediatric cohort generally experienced milder disease than did the adult cohort, with less severe ILD [21]. African descent was associated with worse pulmonary outcomes due to a greater association with RP-ILD. This phenomenon has been reported frequently in Japanese and Chinese patients [6–27] as well as in predominantly Caucasian population studies conducted in the U.S [28, 29]. These results, however, were not reproduced in the study performed in the Brazilian White population [22].

When comparing our cohort to the cluster classifications for MDA-5 dermatomyositis (DM) proposed by Allenbach et al. [17], we identified both parallels and notable differences. In the first group of patients described as the MDA-5 RP-ILD type, both studies observed poor prognoses among patients with RP-ILD. However, unlike Allenbach’s findings, mechanic’s hands were absent in our RP-ILD patients, potentially reflecting differences due to our smaller sample size or variations in demographic and genetic factors. These patients, despite aggressive treatment strategies, succumbed to complications related to therapy, underscoring the challenging prognosis associated with this group. Additionally, all adults in our study with RP-ILD were positive for anti-Ro 52 autoantibodies, a marker associated with poor prognosis in other studies as well [30].

The second group of patients noted to be the rheumatic DM type, demonstrated strong similarities between our study population and Allenbach’s cohort. In both studies, patients—predominantly women—had mild arthritis, stable ILD, favorable outcomes, and gradual improvement in skin manifestations. They responded well to single DMARDs combined with IVIG or rituximab, as reflected by stable ILD disease activity and improvement in skin symptoms.

However, the last group of patients, the vasculopathy DM type, did not show consistency with Allenbach’s characterization, especially with regards to the correlation of skin findings to pulmonary changes. Allenbach et al. described a male predominance, severe vasculopathy, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and ulcerative skin lesions in this cluster. Our study revealed ulcerative skin lesions were not associated with ILD, unlike findings in other prior studies [31, 32]. In contrast, Raynaud’s phenomenon was associated with the presence of ILD. Notably, one patient in our cohort presented with overlapping features of RP-ILD, mechanic’s hands, and vasculopathy but could be classified within this last group due to the predominance of skin and vasculopathy symptoms, highlighting potential overlap between clusters. These patients often required more intensive treatment regimens, involving combinations of two DMARDs and IVIG and/or rituximab to manage disease activity for clinical response. Despite this, ulcerative skin lesions were notably resistant to treatment, sometimes requiring additional interventions such as Botox for severe Raynaud’s, highlighting the complex management needs of patients with extensive vasculopathy.

These observations suggest that while Allenbach’s classifications provide a useful framework, clinical variability influenced by demographic, genetic, or sample-size specific factors may result in differences in presentation and outcomes, underscoring the need for incorporating these parameters into our clinical decision making tools. An additional dimension in our study involved the observation of these features among pediatric patients as well, who tended to exhibit milder skin disease when they had RP-ILD.

Furthermore, our cohort identified two adult female patients over 40 years of age who had ovarian cancer; one with a low titer of anti-TIF-1 g and SAE1 antibodies, whereas the other, interestingly, lacked additional autoantibodies, with the exception of anti-MDA-5 antibodies. While the association of the former antibodies with malignancy is well established [33], notably, the anti-MDA5 autoantibody has not been definitively linked to malignancy in previous studies, and the risk is less pronounced, which is consistent with our dataset [34].

Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for improving patient prognosis in anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis as RP-ILD, which is resistant to standard immunosuppresive therapy, is the leading cause of mortality in this population [35]. Recognizing the amyopathic or hypomyopathic nature of the disease, where weakness may not correlate with myopathy and muscle enzyme elevation, is particularly important. Assessment of inflammatory markers, myositis-specific autoantibodies, electromyography, imaging modalities, and muscle biopsy can assist in establishing a diagnosis. High clinical suspicion is needed, and the anti-MDA5 antibody provides critical diagnostic confirmation.

Our study adds to the growing body of knowledge by emphasizing the potential racial and demographic variations in anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis, as well as delineating similarities and differences between adult and pediatric populations. These findings are particularly important as no standardized treatment guidelines currently exist for this condition. Interventions include IVIG, calcineurin inhibitors, azathioprine, mycophenolate, biologics such as abatacept and rituximab, and targeted DMARD therapies such as tofacitinib, often with background steroid use [18, 36, 37]. Adjunctive therapies such as plasma exchange and Polymyxin-B direct hemoperfusion have also been employed [38]. Evidence suggests that rapidly escalating therapy, including rituximab often combined with mycophenolate, may improve outcomes compared to historical controls in patients with RP-ILD [39]. These findings suggest that early aggressive combination immunosuppression may enhance patient prognosis [40]. Poor prognostic factors include elevated bronchoalveolar lavage neutrophil counts; early pulmonary involvement with hypoxemia and traction bronchiectasis; and increased serum CX3CL1, CXCR4, and interleukin-18 levels [38, 41]. Anti-MDA5 antibody titers are correlated with disease severity and clinical response [42]. Serum Krebs von den Lungen-6 and ferritin levels have been used to monitor therapeutic response [38, 43].

We acknowledge the small sample size and the limitations inherent to this descriptive, single-center, retrospective study. While larger, more diverse cohorts are essential to confirm these findings and ensure generalizability, we believe it is important to share this data to highlight the worse prognosis observed in certain subgroups. Additionally, all patients self-identified as White, Black, African American, or Hispanic, with only one category selected except for one patient who identified as Black Hispanic, precluding a definitive assessment of the associations among race, age of onset, disease phenotype, and severity. Our study underscores the critical need for early diagnosis and proactive, intensive treatment to improve outcomes in these patients.

Conclusion

Our study highlights key demographic and clinical patterns, noting that pediatric patients more often present with myositis, while adults, particularly those of African descent or with anti-Ro52 antibodies, are at higher risk for RP-ILD and worse outcomes. These findings underscore that worse prognosis may be associated with certain subgroups of patients, stressing the need for appropriate recognition of risk factors, early diagnosis and aggressive initial treatment strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- Anti-MDA5

Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5

- RP-ILD

Rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease

- ILD

Interstitial lung disease

- IVIG

Intravenous immunoglobulin

- CADM

Clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis

- IFIH

Interferon-induced helicase C domain

- Anti-TIF-γ

Anti-Transcription intermediary factor 1 gamma

- Anti-SAE

Anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme

- CX3CL1

Chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1

- CXCR4

Chemokine receptor type 4

Author contributions

SK: Data collection, writing and editing of the tables and manuscript. FE: Data review, writing and editing the manuscript. DW: Writing and editing the manuscript. AK: Writing and editing the manuscript. XX: Worked on statistics, data analysis and editing the manuscript. CT: Data collection, writing and editing of the tables and manuscript. BA: Data collection, writing and editing the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for the study.

Data availability

Patient data were collected from the Epic electronic medical records via a search tool to identify all the myositis patients. The dataset was stored on Epic and deidentified patient information compiled into a spreadsheet and shared as supplementary charts/additional files for review.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Montefiore/Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. As this retrospective chart review study did not involve any active intervention, the requirement for consent to participate was waived.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sakamoto N, Ishimoto H, Nakashima S, Yura H, Miyamura T, Okuno D, et al. Clinical features of Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive Rapidly Progressive interstitial lung disease without signs of Dermatomyositis. Intern Med. 2019;58(6):837–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassius C, Amode R, Delord M, Battistella M, Poirot J, How-Kit A, et al. MDA5(+) Dermatomyositis is Associated with stronger skin type I Interferon Transcriptomic signature with Upregulation of IFN-kappa transcript. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(6):1276–9. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perron MM, Vasquez-Canizares N, Tarshish G, Wahezi DM. Myositis autoantibodies in a racially diverse population of children with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021;19(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li D, Tansley SL. Juvenile dermatomyositis-clinical phenotypes. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21(12):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakashima R, Imura Y, Kobayashi S, Yukawa N, Yoshifuji H, Nojima T, et al. The RIG-I-like receptor IFIH1/MDA5 is a dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen identified by the anti-CADM-140 antibody. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(3):433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato S, Hirakata M, Kuwana M, Suwa A, Inada S, Mimori T, et al. Autoantibodies to a 140-kd polypeptide, CADM-140, in Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(5):1571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiorentino D, Chung L, Zwerner J, Rosen A, Casciola-Rosen L. The mucocutaneous and systemic phenotype of dermatomyositis patients with antibodies to MDA5 (CADM-140): a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(1):25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parronchi P, Radice A, Palterer B, Liotta F, Scaletti C. MDA5-positive dermatomyositis: an uncommon entity in Europe with variable clinical presentations. Clin Mol Allergy. 2015;13:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceribelli A, Fredi M, Taraborelli M, Cavazzana I, Tincani A, Selmi C, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of anti-MDA5 antibodies in European patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(6):891–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sontheimer RD. MDA5 autoantibody-another indicator of clinical diversity in dermatomyositis. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(7):160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeung TW, Cheong KN, Lau YL, Tse KN. Adolescent-onset anti-MDA5 antibody-positive juvenile dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease and spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021;19(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao H, Xia Q, Pan M, Zhao X, Li X, Shi R, et al. Gottron Papules and Gottron sign with Ulceration: a distinctive cutaneous feature in a subset of patients with Classic Dermatomyositis and clinically Amyopathic Dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(9):1735–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurtzman DJB, Vleugels RA. Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) dermatomyositis: a concise review with an emphasis on distinctive clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(4):776–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gil B, Merav L, Pnina L, Chagai G. Diagnosis and treatment of clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM): a case series and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(8):2125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abe Y, Matsushita M, Tada K, Yamaji K, Takasaki Y, Tamura N. Clinical characteristics and change in the antibody titers of patients with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive inflammatory myositis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(9):1492–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, Cao M, Plana MN, Liang J, Cai H, Kuwana M, et al. Utility of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody measurement in identifying patients with dermatomyositis and a high risk for developing rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease: a review of the literature and a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(8):1316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allenbach Y, Uzunhan Y, Toquet S, Leroux G, Gallay L, Marquet A, et al. Different phenotypes in dermatomyositis associated with anti-MDA5 antibody: study of 121 cases. Neurology. 2020;95(1):e70–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nombel A, Fabien N, Coutant F. Dermatomyositis with Anti-MDA5 antibodies: Bioclinical features, pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Front Immunol. 2021;12:773352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He S, Zhou Y, Fan C, Ma J, Chen Y, Wu W et al. Differences in sex- and age-associated mortality in patients with anti-MDA5 positive Dermatomyositis. Mod Rheumatol. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Findlay AR, Goyal NA, Mozaffar T. An overview of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51(5):638–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mamyrova G, Kishi T, Shi M, Targoff IN, Huber AM, Curiel RV, et al. Anti-MDA5 autoantibodies associated with juvenile dermatomyositis constitute a distinct phenotype in North America. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(4):1839–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borges IB, Silva MG, Shinjo SK. Prevalence and reactivity of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (anti-MDA-5) autoantibody in Brazilian patients with dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(4):517–23. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato S, Kuwana M, Fujita T, Suzuki Y. Anti-CADM-140/MDA5 autoantibody titer correlates with disease activity and predicts disease outcome in patients with dermatomyositis and rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23:496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukae H, Ishimoto H, Sakamoto N, Hara S, Kakugawa T, Nakayama S. Clinical differences between interstitial lung disease associated with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis and classic dermatomyositis. Chest. 2009;136:1341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye S, Chen XX, Lu XY, Wu MF, Deng Y, Huang WQ. Adult clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with rapid progressive interstitial lung disease: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji SY, Zeng FQ, Guo Q, Tan GZ, Tang HF, Luo YJ. Predictive factors and unfavorable prognostic factors of interstitial lung disease in patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis: a retrospective study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123:517–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sontheimer RD. Clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis: what can we now tell our patients? Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moghadam-Kia S, Oddis CV, Sato S, Kuwana M, Aggarwal R. Antimelanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody: expanding the clinical spectrum in north American patients with Dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(3):319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moghadam-Kia S, Oddis CV, Aggarwal R. Anti-MDA5 antibody spectrum in Western World. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20(12):78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lv C, You H, Xu L, Wang L, Yuan F, Li J, et al. Coexistence of Anti-Ro52 antibodies in Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis is highly Associated with Rapidly Progressive interstitial lung disease and mortality risk. J Rheumatol. 2023;50(2):219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narang NS, Casciola-Rosen L, Li S, Chung L, Fiorentino DF. Cutaneous ulceration in dermatomyositis: association with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibodies and interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67(5):667–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma X, Chen Z, Hu W, Guo Z, Wang Y, Kuwana M, et al. Clinical and serological features of patients with dermatomyositis complicated by spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(2):489–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koga T, Okamoto M, Satoh M, Fujimoto K, Zaizen Y, Chikasue T et al. Positive autoantibody is associated with malignancies in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Biomedicines. 2022;10(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Mecoli CA, Igusa T, Chen M, Wang X, Albayda J, Paik JJ, et al. Subsets of idiopathic inflammatory myositis enriched for contemporaneous cancer relative to the general population. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75(4):620–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Wu J, Miao M, Gao X, Cai W, Shao M, et al. Predictors of poor outcome of Anti-MDA5-Associated rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease in a Chinese cohort with Dermatomyositis. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:2024869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabbagh S, Almeida de Jesus A, Hwang S, Kuehn HS, Kim H, Jung L, et al. Treatment of anti-MDA5 autoantibody-positive juvenile dermatomyositis using tofacitinib. Brain. 2019;142(11):e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hallowell RW, Paik JJ. Myositis-associated interstitial lung disease: a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and management. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;40(2):373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirakashi M, Nakashima R, Tsuji H, Tanizawa K, Handa T, Hosono Y, et al. Efficacy of plasma exchange in anti-MDA5-positive dermatomyositis with interstitial lung disease under combined immunosuppressive treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(11):3284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.So H, Wong VTL, Lao VWN, Pang HT, Yip RML. Rituximab for refractory rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease related to anti-MDA5 antibody-positive amyopathic dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(7):1983–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsuji H, Nakashima R, Hosono Y, Imura Y, Yagita M, Yoshifuji H, et al. Multicenter prospective study of the efficacy and safety of combined immunosuppressive therapy with high-dose glucocorticoid, Tacrolimus, and Cyclophosphamide in interstitial lung diseases accompanied by Anti-melanoma differentiation-Associated Gene 5-Positive Dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(3):488–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takada T, Aoki A, Asakawa K, Sakagami T, Moriyama H, Narita I, et al. Serum cytokine profiles of patients with interstitial lung disease associated with anti-CADM-140/MDA5 antibody positive amyopathic dermatomyositis. Respir Med. 2015;109(9):1174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koga T, Fujikawa K, Horai Y, Okada A, Kawashiri SY, Iwamoto N, et al. The diagnostic utility of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody testing for predicting the prognosis of Japanese patients with DM. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(7):1278–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mimori T, Nakashima R, Hosono Y. Interstitial lung disease in myositis: clinical subsets, biomarkers, and treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14(3):264–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Patient data were collected from the Epic electronic medical records via a search tool to identify all the myositis patients. The dataset was stored on Epic and deidentified patient information compiled into a spreadsheet and shared as supplementary charts/additional files for review.