Abstract

Background

There is a growing importance of loneliness measurement through valid and reliable instruments. However, to establish valid and reliable measures, there is a need to explore their psychometric properties in different research settings and language environments. For this reason, this study aimed to validate the Three Item Loneliness Scale (TILS) in the Czech Republic within a Slavonic language environment.

Methods

A sample of Czech adults (n = 3236) was used consisting primarily of university students. We utilized Classical Test Theory to assess TILS internal consistency, temporal stability, and factor structure. Item Response Theory (IRT) was used to estimate Differential Item Functioning (DIF), the discrimination and difficulty of the TILS items and to estimate the measurement precision of the whole scale. Construct validity was explored through the Spearman correlation coefficient using personality traits, depression, and anxiety.

Results

The results showed satisfactory reliability and validity of the TILS in the Czech Republic. The scale’s internal consistency and temporal stability were found to be satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 0.81, McDonald’s ω = 0.82, ICC = 0.71). The parallel analysis supported the unidimensionality of the TILS. The IRT results indicated that the highest measurement precision was reached in individuals with lower and above-average levels of loneliness. Significant correlations between the TILS scores, anxiety, depression, and personality traits supported the construct validity of the scale. Although the DIF analysis identified statistically significant differences in responses to items TILS_2 and TILS_3 based on education level and employment status (with no significant differences observed for TILS_1), the effect sizes of these differences were small. This indicates that, despite statistical significance, the practical impact on the scale’s validity across these groups is minimal.

Conclusions

The validated TILS provides a reliable and valid tool for assessing loneliness in the Czech Republic. Its brevity makes it a practical option for researchers and clinicians seeking to measure loneliness time-efficiently. Future studies should explore how adding new items could increase the measurement precision of the TILS.

Keywords: Loneliness, Measurement, TILS, Psychometric Properties, Validation, Item response theory

Introduction

Loneliness can be defined as a subjectively perceived state of aversion resulting from a lack of interpersonal relationships that one would like to have and actually have [1]. For numerous individuals, loneliness manifests as a transient phenomenon. Nonetheless, a subset of the population encounters challenges in meeting their social requirements, leading to prolonged loneliness [2]. In the scholarly discourse on loneliness, a prevalent categorization delineates between emotional and social loneliness. This bifurcation stems from Weiss’s perspective on social needs, which posits that diverse social relationships cater to distinct social necessities [3]. Emotional loneliness emerges from an individual’s perceived absence of close emotional ties, encompassing elements such as emotional support, affection, and intimacy. It is characterized by sentiments of detachment, a perceived lack of individuals who truly comprehend and resonate with one’s feelings, and the absence of supportive figures in times of need. Conversely, social loneliness stems from a perceived deficiency in a broader social network, encapsulating facets of social integration and a sense of belonging. It manifests as a feeling of disconnection from one’s surroundings, a dearth of companions for casual interaction or seeking practical assistance, and an overall sense of not belonging to a particular group or community [4]. This bilateral nature of loneliness underscores the importance of discerning the extent to which individual facets are measured. This distinction is crucial for establishing criterion-related validity, allowing for meaningful comparisons on how accurately a measure is able to capture either emotional or social loneliness within the established theoretical framework.

Research on loneliness has been increasing in recent years. The primary reason for this increased research interest is probably associated with its widespread and increasing prevalence. In general, the prevalence of loneliness among young people ranges from 9 to 14% and among older people from 18 to 24% in the European area [5]. In more detail, the percentage of loneliness among older adults ranges from more than 25% in Italy to 8% in Germany and the Netherlands [6, 7]. More importantly, according to the findings of the Cigna health insurance company, there was a 13% increase in loneliness in the United States from 2018 to 2020 [8]. The COVID-19 pandemic has also had a particular impact on loneliness, with data showing an increase in feelings of loneliness in all age groups during the pandemic, but especially in young adults [9, 10].

Many studies have shown that loneliness is related with mental and physical health [11]. Moreover, loneliness is associated with mortality and morbidity [12, 13]. In the field of mental health, a number of studies have revealed that there is a negative relationship between loneliness and mental health among children [14] and adults [15]. In more detail, a large number of studies found that there is a positive link between loneliness and depression [16, 17], including meta-analyses [18]. Moreover, loneliness seems to be associated with cognitive impairment [19], or psychosis [20], schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder [21]. Research has also demonstrated positive links between loneliness and physical health, such as stroke and coronary heart disease [22, 23], and with various health risk behaviours [24]. In recent years, a number of studies have revealed a mutual relationship between obesity and loneliness [25]. In addition, among older adults, loneliness is positively linked with falls, meaning that higher levels of loneliness predict a higher likelihood of falling [26]. In summary, it can be concluded that loneliness is a social determinant of health in general [27, 28].

In order to explore associations between loneliness and health further, there is a need to have valid and reliable methods for assessing loneliness. Loneliness is mostly measured by one of eight main questionnaires: the University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale (UCLA) [29, 30], the Children’s Loneliness Scale (CLS) [31], the Rasch-Type Loneliness Scale (RTLS, often referred to as DJGLS — the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale) [32], the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA) [33], the Differential Loneliness Scale (DLS) [34], the Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents (LACA) [35], the Relational Provisions Loneliness Questionnaire (RPLQ) [36], and the Peer Network and Dyadic Loneliness Scale (PNDLS) [37]. Among these questionnaires, the UCLA Loneliness Questionnaire appears to be the most widely used [4]. Designed in English for application among (young) adults consisting of 20 items, it is the predominant tool for assessing loneliness in the MASLO (“Meta-Analytic Study of Loneliness”) database, being utilized in 64.24% of all studies therein. Although the scale has undergone translations into numerous languages, its usage is primarily concentrated in North America (59.69%), followed by Europe (20.06%), and Asia (17.04%) [4]. Studies have shown measurement invariance across gender, age, and other factors like race, marital status, employment, income, and education. This indicates that the scale can be reliably used in different contexts. However, the scale’s factor structure lacks consensus, with various studies proposing different solutions. This inconsistency can create ambiguity in interpreting results and comparing studies [4]. The UCLA has been revised and abbreviated several times. These abbreviated versions usually consist of 8 items [38, 39]. The next two most popular measures are The Children’s Loneliness Scale (CLS) and The Rasch-Type Loneliness Scale (RTLS) consisting of 24 items and 11 items respectively. The CLS has been widely used, with 20.89% of studies in the MASLO database employing this scale. It is primarily used with children (65.73%) and adolescents (34.09%). While some studies have examined longitudinal invariance, the results are mixed, indicating that more work is needed to determine the stability of the scale over time [4]. The RTLS offers several response category configurations, ranging from a 3-point to a 5-point scale, providing flexibility in application. The RTLS has been used across different demographics, primarily with older adults (58.69%), but also with adults (36.62%). However, inconsistencies in factor structure and dichotomization methods, along with a lack of test-retest reliability data, suggest caution in interpretation and application [4].

However, there is also a version containing only three items [40]. This ultra-short version of the UCLA (i.e., Three Item Loneliness Scale: TILS) was designed to reduce respondent burden while keeping the psychometric properties of the original scale. The validity of this three-item version was supported using variables such as marital status, housing, depressive symptoms, and UCLA scores [40]. The TILS showed good factorial validity and good reliability in terms of internal consistency and test-retest measures [41]. Good psychometric properties have also been demonstrated for a specific group of respondents with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder [42]. The TILS, as a 3-item scale, is suitable for both larger surveys and for practical purposes. Moreover, there is strong empirical support for the construct validity of the scale [41].

The TILS has been validated on American, Japanese and Spanish populations [40, 43, 44]. However, evidence of the reliability and validity of the TILS remains scarce in Slavonic languages, in particular, neither the 8-item abbreviated version nor the 3-item version of the UCLA has been validated in the Czech environment thus far. Previous studies suggested that some psychometric parameters, such as reliability, can be changed depending on the language used [45]. For this reason, it is important to examine whether the high psychometric properties of the TILS will remain sufficiently high when used with participants speaking one of the Slavonic languages.

Although there is some preliminary evidence about the satisfactory reliability and validity of the TILS in Poland [41], further evidence is needed to support adequate measuring abilities of the TILS in countries speaking Slavonian languages. Moreover, there is a lack of validated scales measuring loneliness in the Czech environment. Thus, validating the TILS as the abbreviated version of the most widely used scales for assessing loneliness (i.e., UCLA) would have wide implications for research on loneliness in the Czech Republic. For these two reasons, our study aimed to examine the psychometric properties (including reliability, construct, concurrent and factorial validity) of the TILS in another Slavonic language environment and aimed to adapt the TILS for use in the Czech cultural and socio-economic context. Our study hypotheses were as follows:

H1: Loneliness and neuroticism are positively correlated.

H2: Loneliness and extraversion exhibit a negative correlation.

H3: Loneliness and agreeableness demonstrate a negative correlation.

H4: There is a positive correlation between loneliness and depression.

H5: Loneliness and anxiety show a positive correlation.

H6: Self-esteem is negatively correlated to loneliness.

Methods

Participants

The research involved adult participants who responded through a digital survey managed by the Olomouc University Social Health Institute (OUSHI). Their involvement was completely voluntary, allowing them the freedom to exit the survey whenever they chose. It was mandatory for participants to acknowledge their understanding of the consent information before proceeding with the survey. Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from Palacký University’s Theology Faculty’s Ethics Board (No. 2020/4).

Sample 1

Data were gathered between September 2022 and May 2023, utilizing the snowball sampling technique. The data gathering was integrated into university coursework, where students actively participated not merely for academic credits but also as a part of their educational curriculum. In order to ensure the high quality of the data, we removed respondents that answered at least 3 questionnaires used in this study in the same way (n = 870), i.e., participants who indicated a pattern of responses such as deliberately rating themselves with response option 1, across at least 3 questionnaires, resulting in 10,232. Moreover, we excluded respondents whose responses to questionnaire items on weight, height, and age deviated beyond the specified tolerance thresholds. These thresholds were set to: weight = 2 kg, height = 2 centimeters, age = 1 year (n = 2282), and respondents with an age lower than 18 years old (n = 3491), resulting in 4459 participants. These quality control questions were integrated into the survey always at the beginning and at the very end to detect inconsistently responding participants and in turn improve the quality of the data. Participants whose answered values for their weight, height, and age at the beginning deviated from values at the end by pre-set thresholds mentioned above were ultimately excluded. We also excluded participants who did not respond to a single TILS item (n = 120) and were not of Czech nationality (n = 123), resulting in 4216 respondents. Finally, we excluded subjects (n = 1030) who seemed to be the result of repeated questionnaire filling by the same student in order to get credit. Identification of these subjects was based on the following two formulas:

Every student who was tasked to recruit new participants was given a unique code that each respondent inputs into the survey upon starting. Afterwards, in order to avoid repeated questionnaire filling, browser type and version was tracked to detect how many surveys with particular unique code were completed using the same browser type and version. In the equation above, p is the probability of matching the browser type and version for each student x_ji is the number of rows where there is a match between the i-th element from the code column of the recruiting student and the j-th element from the type and version row of the browser on which the questionnaire was completed. n is the number of rows in the matrix. A tolerance limit was then calculated based on the match probabilities:

In the second equation, m is the number of questionnaires completed by the interviewer, and q is the label for the student. For a more detailed explanation regarding the data exclusion process see supplementary material 1 online.

After the exclusion of respondents based on the criterion defined by the two equations, the final number of participants was 3186 (Age: M = 31.38, range 18–80, SD = 12.96; Females: 66.82%). Missing data screening indicated the following degree of missing values in scales used in our study: BFI-N = 6.72%; BFI-O = 7%; BFI-C = 7.31%; BFI-A = 7.85%; BFI-E = 7.5%; OASIS = 8.44%; ODSIS = 8.66%; RSES = 10.64%; TILS = 0%. The missing data patterns were evaluated using the Little MCAR test, which indicated that the data were missing completely at random. Due to the large number of participants, it was decided to exclude cases with missing data listwise instead of imputing the missing values. In the final step, we conducted outlier screening using Median Absolute Deviation (MAD). This screening indicated that across the scales used in the present study, there were 386 outliers. Screening of these outlying values did not suggest that respondents answered a large number of items across questionnaires used in the same way. Thus, these respondents were retained in the dataset.

Sample 2

To assess the test-retest reliability, we conducted an online survey among 50 Czech adults from September to November 2021. Participants filled out the same survey again after two weeks. The data was collected using a convenience sampling approach. Our choice of sample size aligns with established practices in loneliness research, as evidenced by relevant studies demonstrating reliability using samples of 30 [46] and 50 [47] participants in validating loneliness measurement instruments. Initially, there were 61 participants. Outlier screening using the MAD method indicated that none of the respondents provided highly consistent responses across a significant number of survey items. Additionally, participants who responded inconsistently to control questions were excluded (n = 11), leaving a total of 50 participants (Age: Mean = 31.96, SD = 9.30, Females: 60%).

Measures

Three item loneliness scale (TILS)

The TILS, also known as the UCLA-3 or the UCLA Loneliness Scale Short Form, is a simplified version of longer University of California, Los Angels (UCLA) Loneliness Scale, designed by Hughes et al. [40] to measure feelings of loneliness and social isolation. The Three Item Loneliness consists of the following three questions: (1) “How often do you feel that you lack companionship?”; (2) “How often do you feel left out?“; (3) “How often do you feel isolated from others?” each rated on a 3-point scale ranging from Hardly ever (1) to Often (3) with higher scores indicating greater feelings of loneliness.

Big five inventory (BFI)

The BFI is one of the most widely used measures of personality traits [48]. This 44-item tool consists of five sub-scales assessing five personality factors: neuroticism (BFI-N), extraversion (BFI-E), openness (BFI-O), agreeableness (BFI-A), and conscientiousness (BFI-C). Each item is presented as a statement and is rated on a five-point scale ranging from ‘Strongly Disagree’ (1) to ‘Strongly Agree’ (5). After reversing the scores of several items, a higher score indicates a higher degree of the trait. For this study, we utilized the Czech version [49] of the instrument. The internal consistency of all BFI subscales was satisfactory: BFI-N: Cronbach’s = 0.89, 95% CI[0.88–0.89] and McDonald’s = 0.89, 95% CI[0.88–0.89]; BFI-O: Cronbach’s = 0.86, 95% CI[0.85–0.87] and McDonald’s = 0.86, 95% CI[0.85–0.87]; BFI-A: Cronbach’s = 0.78, 95% CI[0.77–0.80] and McDonald’s = 0.78, 95% CI[0.77–0.80]; BFI-C: Cronbach’s = 0.85, 95% CI[0.84–0.86] and McDonald’s = 0.85, 95% CI[0.84–0.86]; BFI-E: Cronbach’s = 0.88, 95% CI[0.88–0.89] and McDonald’s = 0.88, 95% CI[0.88–0.89].

Overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS)

The OASIS is used to assess the severity and impact of anxiety symptoms [50]. It consists of five questions examining the frequency, intensity, and interference of anxiety symptoms in everyday life, including work and social situations. Respondents choose answers on a scale from ‘never’ (0) to ‘all the time’ (4). The total score ranges from 0 to 20, with higher values indicating a greater level of anxiety. We utilized the Czech version of this scale based on the validation conducted by Sandora et al. [51]. In this study, Cronbach’s was 0.90, 95% CI[0.90–0.91] and McDonald’s = 0.90, 95% CI[0.89–0.91].

Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale (ODSIS)

The ODSIS is an instrument developed to assess how severe depression is and how it affects an individual’s normal functioning [52]. Participants rate their experience of depressive symptoms over the past week on a scale ranging from ‘never’ (0) to ‘all the time’ (4). The responses are coded and interpreted in the same manner as the OASIS. For our study, we used the Czech version of the ODSIS [51]. Internal consistency of the ODSIS was found to be excellent in our study: Cronbach’s = 0.96, 95% CI[0.96–0.97] and McDonald’s = 0.96, 95% CI[0.96–0.97].

Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (RSES)

Self-esteem was assessed using the RSES [53], a 10-item self-report instrument. This tool evaluates individual self-esteem on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly agree’ (1) to ‘strongly disagree’ (4). After reversing the positively worded items, the total RSES score was calculated, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem. For this study, we used the Czech version of the RSES [54]. The internal consistency of the RSES was good: Cronbach’s = 0.88, 95% CI[0.88–0.89] and McDonald’s = 0.89, 95% CI[0.88–0.89].

De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (DJGLS)

The DJGLS [32], one of the most utilized loneliness scale worldwide [4], measures overall loneliness, as well as its social and emotional facets. The scale has two subscales: the social loneliness subscale (DJGLS-S, five positively formulated items) and the emotional loneliness subscale (DJGLS-E, six negatively formulated items). Each from 11 statements is rated by possible answers: ‘yes’ (1), ‘more or less’ (2), and ‘no’ (3). Processing of responses involves converting the three categories into dichotomous responses, with one point assigned to the response indicating a feeling of loneliness. The middle category ‘more or less’ is assumed to indicate a feeling of loneliness. This procedure results in a total DJGLS score ranging from 0 to 11 [55]. We utilized the Czech version of the DJGLS [56]. Internal consistency of both subscales was good: DJGLS-E: Cronbach’s = 0.90 95% CI[0.90–0.91] and McDonald’s = 0.90 95% CI[0.90–0.91]; DJGLS-S: Cronbach’s = 0.89 95% CI[0.88–0.89] and McDonald’s = 0.89 95% CI[0.88–0.89].

Data analysis

Classical test theory analysis

The reliability in terms of internal consistency of the scale was evaluated using McDonald’s and Cronbach’s . To further explore the reliability of the TILS, we used the two-way mixed effects intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to assess the temporal stability of the TILS scores. Due to the insufficient degrees of freedom preventing the application of Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), alternative approaches commonly employed before Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) were adopted to analyse the TILS’s structure. Specifically, parallel analysis [57] based on a polychoric correlation matrix, was applied. This approach allowed us to determine the quantity of factors derived from the actual data in contrast to those obtained from random data.

Item response theory analysis

Psychometric evaluation of the TILS incorporated the use of Item Response Theory (IRT). To verify IRT prerequisites we conducted the following steps: first, we tested local independence i.e. assumption that items will be independent of each other after taking into account latent variable. This assumption was tested by checking local dependence matrix based on the , As indicated by Harmsen et al. [58] standardized , values below 10 indicates that local independence assumption holds. Second, we tested monotonicity assumption (probability of achieving a higher score on an item increases as the latent trait increases) using “check.monotonicity” function in mokken package [59]. Finally, we checked unidimensionality assumption (only one latent trait underlays responses on items) using parallel analysis. For the IRT model’s estimation, the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) algorithm was implemented. For IRT analyses, we chose the Generalized Partial Credit IRT Model, which calculates three parameters of each item: (1) item slope/gradient (α) and (2) two threshold parameters determining the level of difficulty (β). A steeper gradient denotes more accurate differentiation among participants concerning the underlying trait () [60]. The parameter indicates the overall item difficulty [61]. We used both of these parameters to create the item-information curve (IIC), which determines the amount of information provided by an item. In a similar way, we also constructed the test information function to determine the measurement precision of the TILS.

Differential Item Functioning

Differential Item Functioning (DIF) was examined between socio-demographic groups (for rationale, see Supplementary Material 2 online). This examination helps to reveal whether the scale measures consistently regardless of potential differences in how loneliness manifests or is experienced by males and females. To evaluate potential Differential Item Functioning (DIF) across gender, we employed the SIBTEST method, specifically the Crossing-SIBTEST procedure [62] which is appropriate for detecting nonuniform DIF in polytomous items. We specified the type of DIF effect as nonuniform to investigate potential interactions between gender and the latent trait of loneliness. We also explored uniform DIF. Following recommendations by Kim and Oshima [63], p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate. No anchor items were specified.

Construct and concurrent validity

In the final stage, we examined construct validity. Since the TILS total score did not meet the assumption of normality, we employed the zero-order Spearman correlation coefficient to investigate the relationship between depression, anxiety, loneliness and personality traits. The personality traits (as measured by the Big Five) were also used to evaluate the psychometric properties of the TILS in related studies where all dimensions showed significant associations with the loneliness score [43]. Therefore, comparable results might be expected in the present study.

Concurrent validity of the TILS was explored via associations with the two components of the DJGLS: (a) social loneliness and (b) emotional loneliness. Consequently, we used the Williams t-test [64] to explore whether the association between the TILS and the emotional component of loneliness will be significantly different as compared with the association between the TILS and social component of loneliness. All statistical analyses were performed in the R programming environment, primarily utilizing the following packages: psychtoolbox [65], ufs [66], mirt [67], lavaan [68], papaja [69], and psych [70], difR [71] .

Results

Parallel analysis, reliability and item statistic

Parallel analysis supported unidimensionality of the scale. The reliability of TILS was good: Cronbach’s = 0.81, 95% CI[0.80–0.82] and McDonald’s = 0.82, 95% CI[0.81–0.83]. Correlations between individual TILS items, their means, standard deviations, item-total correlations, and other item statistics such as Skewness and kurtosis can be found in Table 1.Test-retest reliability examination indicated that temporal stability of the TILS was satisfactory: r = 0.71, 95% CI [0.54–0.82] p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistic and correlations between TILS items (sample 1, n = 3186)

| Item | 1 | 2 | M | SD | ITC | Skewness | kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. TILS-1 | - | 1.82 | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.18 | −0.63 | |

| 2. TILS-2 | 0.36*** | - | 1.78 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.33 | −0.93 |

| 3. TILS-3 | 0.52*** | 0.51*** | 1.69 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.50 | −0.83 |

TILS Three Item Loneliness Scale, ITC item-total correlation

*** p < 0.001

Item Response Theory results

Differential Item Functioning

The DIF analysis was conducted to examine whether the items of the TILS function differently across various demographic groups (see Table 2). The groups analyzed included gender (man vs. woman), education level (higher vocational school or lower vs. university), religiosity (religious vs. not religious), employment status (non-working vs. working), and age category (18–49 vs. 50 and older).

Table 2.

Differential Item Functioning Analysis results (sample size: 3186)

| Uniform DIF | Non-Uniform DIF | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Variable | Item | β | χ² | df | Adjusted p | Focal Group | Reference Group | β | χ² | df | Adjusted p | Focal Group | Reference Group |

| Gender | TILS_1 | −0.003 | 0.014 | 1 | p = 0.905 | Man | Woman | 0.036 | 2.461 | 2 | p = 0.438 | Man | Woman |

| TILS_2 | 0.062 | 4.971 | 1 | p = 0.077 | Man | Woman | 0.062 | 4.971 | 1 | p = 0.077 | Man | Woman | |

| TILS_3 | −0.013 | 0.272 | 1 | p = 0.903 | Man | Woman | 0.013 | 0.272 | 1 | p = 0.602 | Man | Woman | |

| Education | TILS_1 | 0.011 | 0.194 | 1 | p = 0.660 | Higher vocational school or lower | University | 0.019 | 0.633 | 2 | p = 0.729 | Higher vocational school or lower | University |

| TILS_2 | −0.114 | 15.136 | 1 | p < 0.001 | Higher vocational school or lower | University | 0.114 | 15.136 | 1 | p < 0.001 | Higher vocational school or lower | University | |

| TILS_3 | 0.172 | 43.173 | 1 | p < 0.001 | Higher vocational school or lower | University | 0.172 | 43.173 | 1 | p < 0.001 | Higher vocational school or lower | University | |

| Religiosity | TILS_1 | −0.014 | 0.271 | 1 | p = 0.602 | Religious | Not Religious | 0.014 | 0.271 | 1 | p = 0.602 | Religious | Not Religious |

| TILS_2 | 0.025 | 0.733 | 1 | p = 0.588 | Religious | Not Religious | 0.054 | 3.693 | 2 | p = 0.473 | Religious | Not Religious | |

| TILS_3 | −0.023 | 0.863 | 1 | p = 0.588 | Religious | Not Religious | 0.023 | 0.863 | 1 | p = 0.529 | Religious | Not Religious | |

| Employment_status | TILS_1 | −0.043 | 3.069 | 1 | p = 0.080 | Non-working | Working | 0.043 | 3.069 | 1 | p = 0.080 | Non-working | Working |

| TILS_2 | −0.056 | 4.382 | 1 | p = 0.054 | Non-working | Working | 0.056 | 4.382 | 1 | p = 0.054 | Non-working | Working | |

| TILS_3 | 0.087 | 13.654 | 1 | p < 0.001 | Non-working | Working | 0.087 | 13.654 | 1 | p < 0.001 | Non-working | Working | |

| Age_category | TILS_1 | −0.068 | 4.148 | 1 | p = 0.125 | 18–49 | 50 and older | 0.068 | 4.148 | 1 | p = 0.125 | 18–49 | 50 and older |

| TILS_2 | −0.009 | 0.049 | 1 | p = 0.824 | 18–49 | 50 and older | 0.009 | 0.049 | 1 | p = 0.824 | 18–49 | 50 and older | |

| TILS_3 | 0.032 | 0.886 | 1 | p = 0.520 | 18–49 | 50 and older | 0.032 | 0.886 | 1 | p = 0.520 | 18–49 | 50 and older | |

β Beta coefficient, χ²chi-square, df degrees of freedom, Adjusted p p-value adjusted for multiple comparisons

Significant uniform and non-uniform DIF were observed for items TILS_2 and TILS_3 with respect to education level. Specifically, participants with a higher vocational school education or lower differed from those with a university education in their responses to these items. For TILS_2, the negative beta value indicates that individuals with lower education were less likely to endorse the item compared to those with higher education, after controlling for overall loneliness levels. Conversely, for TILS_3, the positive beta value suggests that individuals with lower education were more likely to endorse the item than those with higher education. The effect size of the DIF was small, however.

For employment status, significant uniform, and non-uniform DIF were detected for item TILS_3. The positive beta value indicates that non-working individuals were more likely to endorse this item compared to working individuals, after controlling for overall loneliness levels. The Magnitude of beta values was, however, small. No significant DIF was found for gender, religiosity, or age category across any of the TILS items.

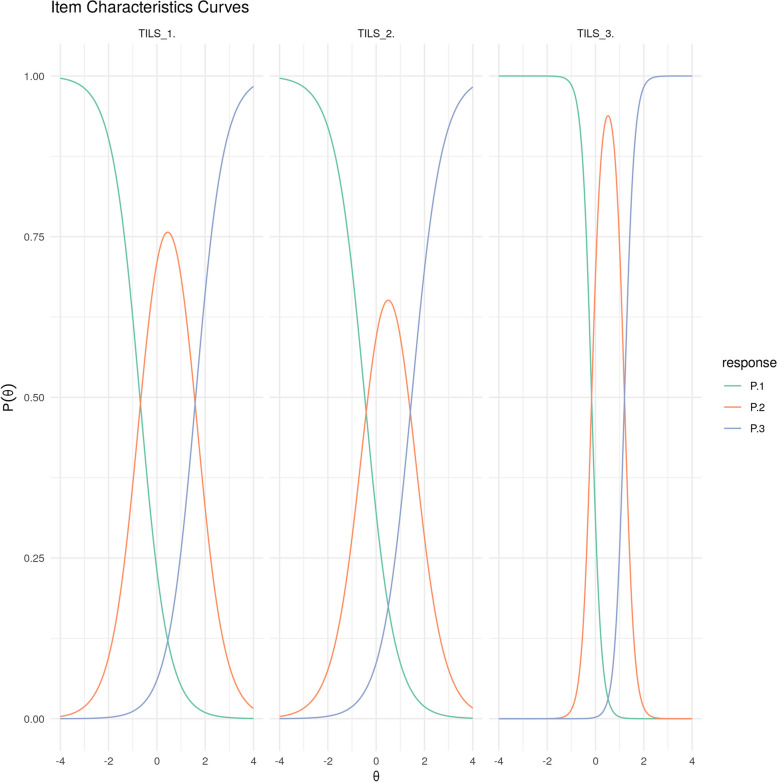

Discrimination and Thresholds of TILS ItemsAs the single-factor model of the TILS was supported, it was possible to perform the IRT analysis. Results revealed that the TILS items have a high discrimination overall. The lowest discrimination parameter had item 2 (“How often do you feel left out?”), and the highest discrimination had item 3 (“How often do you feel isolated from others?”). Regarding item difficulty, Item 1 (How often do you feel that you miss the company of others? ) had the lowest first threshold, indicating it was the easiest item for respondents to endorse beyond ‘Hardly ever.’ However, it also had the highest second threshold, making it the most difficult item for respondents to endorse ‘Often’ compared to the other items (see Table 3). Figure 1 shows the option response function and the information function of the TILS items: The highest precision of the measurement was achieved in individuals with a lower-average degree of loneliness and in individuals with an above-average degree of loneliness. More detailed results concerning threshold parameters and items difficulty can be found in the Table 3.

Table 3.

Item fit, threshold (β) parameters, item discrimination (α) and frequency of responses of TILS items across the sample 1, n = 3186

| Item | α | β1 | β2 | Hardly ever | Some of time | Often | χ2 | df | P value | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TILS-1 | 1.71 | −0.70 | 1.61 | 31.1% | 56.06% | 12.84% | 46.58 | 3.00 | p < 0.001 | 0.07 |

| TILS-2 | 1.60 | −0.47 | 1.47 | 37.66% | 46.67% | 15.66% | 17.62 | 3.00 | p = 0.002 | 0.04 |

| TILS-3 | 5.06 | −0.16 | 1.20 | 44.22% | 42.91% | 12.87% | 26.31 | 3.00 | p < 0.001 | 0.05 |

TILS Three Item Loneliness Scale, χ2 Signed chi-squared test statistic, df Degrees of Freedom, RMSEA Root Mean Square Approximation

Fig. 1.

Item characteristics curves. Notes: The x-axis reflects the degree of a latent trait - Loneliness - - standardized in Z-scores. The Y-axis – on the left - indicates the likelihood of endorsing one of the responses on the three-point Likert scale. Each of the coloured lines represents the response option of the different point on the scale: “Hardly ever” - green line - to “Some of the time” - middle green line -, “Often” - violet line on the right -

IRT analysis of the scale

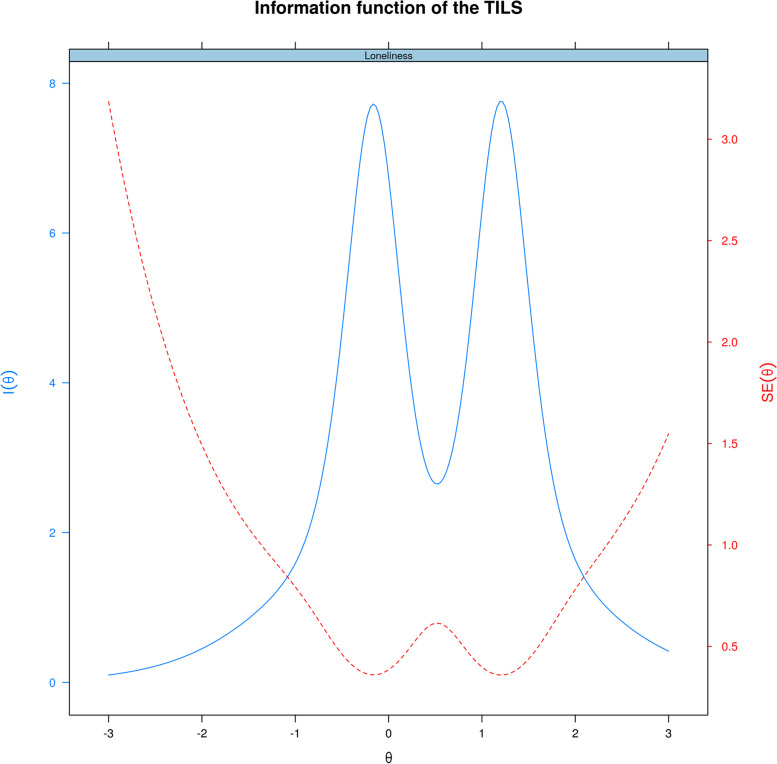

In line with option response function curves, the test information function plot (Fig. 2) suggests that the measurement precision of the TILS is highest in individuals with an average degree of loneliness and in individuals with an above-average degree of loneliness (2). The measurement window between the average and above-average degrees of loneliness shows a decrease in measurement precision. The frequencies of the responses to the TILS items are depicted in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

The test information function of the TILS. Notes: The x-axis refers to the degree (standardized to Z - scores) of loneliness (). The y-axis (right) depicts the standard error of a measurement, while the left side of the y-axis represents the degree of information () obtained during the assessment of different parts of loneliness

Socio-demographic results

Table 4 presents the means and standard deviations of the TILS score across socio-demographic groups (Sample 1). Results of descriptive statistics indicated that the most of the participants were working, not religious, in partnership, reached higher vocational school or lower education, and were female. The socio-demographic table for the second sample is presented in Supplementary Material 3 online.

Table 4.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants (sample 1: 3186)

| variable | n(%) | TILS M(SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age category | ||

| 1 18–49 | 2802 (87.95) | 5.34(1.65) |

| 2 50 and older | 384 (12.05) | 4.9(1.45) |

| Education | ||

| 1 Higher vocational school or lower | 2249 (70.59) | 5.41(1.64) |

| 2 University | 937 (29.41) | 4.98(1.57) |

| Employment status | ||

| 1 Non-working | 1391 (43.66) | 5.62(1.64) |

| 2 Working | 1795 (56.34) | 5.02(1.57) |

| Family status | ||

| 1 Single | 1213 (38.07) | 5.6(1.71) |

| 2 In relationship | 1973 (61.93) | 5.09(1.55) |

| Gender | ||

| 1 Man | 1057 (33.18) | 5.23(1.63) |

| 2 Woman | 2129 (66.82) | 5.31(1.63) |

| Religiosity | ||

| 1 Religious | 998 (31.32) | 5.29(1.65) |

| 2 Not Religious | 2188 (68.68) | 5.28(1.62) |

TILS Three Item Loneliness Scale, M mean, SD Standard Deviation, n number of participants

Correlational analysis

It was found that there is a significant negative association between loneliness and personality traits. In more detail, loneliness was negatively associated with agreeableness, extroversion (supporting H2 and H3), and consciousness. There was also a positive association between loneliness and neuroticism, supporting H1. There was a small significant association between openness and loneliness. The strength of these relationships ranged from small to medium - Table 5. In addition, there was also a positive association between anxiety, depression, and loneliness (supporting H4 and H5). The strength of the relationship was medium for both anxiety and depression. Furthermore, a significant positive association between the TILS score and loneliness (assessed by the DJGLS) was found. However, the strength of this association varied when we looked at the emotional versus social aspects of loneliness. Specifically, the association between the TILS and the emotional aspects of loneliness was much stronger than the association between the TILS and the social aspects of loneliness (t = −20.23, df = 3183, p < 0.001). Finally, in line with our hypothesis (H6), the results revealed a negative association between loneliness and self-esteem.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix of the TILS with personality traits, depression, anxiety and socio-demographic variables (sample 1, n = 3186)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | M(SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. TILS | - | 5.28 (1.63) | |||||||||||

| 2. DJGLS-E | 0.63*** | - | 1.67 (1.69) | ||||||||||

| 3. DJGLS-S | 0.33*** | 0.44*** | - | 2.76 (1.71) | |||||||||

| 4. RSES | − 0.48*** | − 0.44*** | − 0.26*** | - | 27.93 (4.56) | ||||||||

| 5. BFI-A | − 0.17*** | − 0.21*** | − 0.24*** | 0.17*** | - | 3.56 (0.56) | |||||||

| 6. BFI-O | − 0.04* | − 0.07*** | − 0.13*** | 0.17*** | 0.17*** | - | 3.49 (0.65) | ||||||

| 7. BFI-E | − 0.28*** | − 0.25*** | − 0.24*** | 0.33*** | 0.17*** | 0.21*** | - | 3.17 (0.76) | |||||

| 8. BFI-N | 0.42*** | 0.35*** | 0.14*** | − 0.55*** | − 0.15*** | − 0.10*** | − 0.29*** | - | 3.12 (0.81) | ||||

| 9. BFI-C | − 0.26*** | − 0.26*** | − 0.12*** | 0.36*** | 0.21*** | 0.10*** | 0.17*** | − 0.32*** | - | 3.35 (0.64) | |||

| 10. OASIS | 0.42*** | 0.39*** | 0.15*** | − 0.47*** | − 0.12*** | 0.02 | − 0.23*** | 0.52*** | − 0.26*** | - | 12.66 (4.48) | ||

| 11. ODSIS | 0.41*** | 0.41*** | 0.17*** | − 0.46*** | − 0.17*** | 0.02 | − 0.16*** | 0.43*** | − 0.24*** | 0.69*** | - | 10.59 (5.14) | |

| 12. Age | − 0.23*** | − 0.20*** | 0.07*** | 0.26*** | 0.11*** | − 0.03 | 0.04* | − 0.25*** | 0.28*** | − 0.20*** | − 0.20*** | - | 31.38 (12.96) |

| 13. Gender | 0.03 | − 0.02 | − 0.05** | − 0.13*** | 0.16*** | − 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.19*** | 0.07*** | 0.14*** | 0.04* | 0.03 |

SD Standard deviation, M Mean, TILS Three Item Loneliness Scale, DJGLS-S De Jong Gierveld Lonelines Scale – social loneliness, DJGLS-E De Jong Gierveld Lonelines Scale – emotional loneliness, BFI-N Big Five Inventory - Neuroticism, BFI-O Big Five Inventory - Openness, BFI-E Big Five Inventory - Extraversion, BFI-C Big Five Inventory - Conscientiousness, OASIS Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale, ODSIS Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

*** p < 0.001

Discussion

The main objective of this investigation was to assess the psychometric properties of the TILS, with an emphasis on measurement precision, dimensionality internal consistency, Differential Item Functioning, and test-retest reliability. Additionally, the study aimed to investigate the correlations between loneliness (as measured by TILS) and various personality traits, depression, anxiety, and socio-demographic variables. It was revealed that the TILS demonstrates adequate internal consistency, good temporal stability as well as a unidimensional structure. Moreover, the scale exhibits the highest precision in measuring loneliness for individuals with average to above-average degrees of loneliness. However, Differential Item Functioning was observed for certain items across education levels and employment status. Finally, the construct validity of the TILS was supported by associations with personality traits such as, anxiety, depression, and loneliness measured by the DJGLS. However, a significantly stronger association was observed between the TILS and emotional loneliness assessed by the DJGLS as compared with social loneliness.

The TILS demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha 0.81. This result aligns with the scale’s originator, Hughes [40], and subsequent studies conducted on Japanese and Spanish samples, which indicated a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.72 to 0.82 [40, 43, 44, 72].

The parallel analysis further confirmed the unidimensionality of the TILS, in line with studies [42, 73], thus simplifying the interpretation of the scale [43]. Test-retest reliability showed that the TILS provided consistent measurements over time, which corresponds with the previous research demonstrating test-retest reliability coefficients of 0.83 or above [41, 44]. In terms of slope parameters, Item 3 exhibited the highest discrimination, aligning with the findings of Igarashi [43]. Although the difficulty parameter (β2) value of this item was the lowest among all TILS items, it was located in an above-average degree of loneliness. This suggests that the highest measurement accuracy is reached in individuals with average or above-average levels of loneliness. Conversely, Item 2 possessed the lowest discrimination parameter, warranting a closer examination of this item by future studies [43].

In terms of measurement precision, similar results that were found for item 3 seem to also hold for the entire scale: the TILS seems to precisely measure loneliness in individuals with an average and above-average degree of loneliness, but its measurement quality is considerably decreased in individuals with a higher average degree of loneliness. Given that Igarashi [43] provided similar results on the Japanese sample, it is quite unlikely that our findings can be primarily explained by factors related to our study setting, such as socio-cultural environment etc. Instead, this consistency between the results of this study and the study of Igarashi [43] suggests that it might be the construction of items that could be the primary cause of decreased measurement precision in individuals with a higher average degree of loneliness. This finding also suggests that many studies on loneliness could find significant relationships if the measurement precision of the TILS could be higher in individuals with a higher average degree of loneliness. Nevertheless, the results of the DIF analysis suggest caution should be exercised when comparing rates of loneliness across different employment groups and educational levels using TILS_2 and TILS_3 items. The significant DIF for education suggests that individuals with different educational backgrounds may interpret or respond to certain loneliness items differently. Specifically, lower-educated individuals were less likely to endorse TILS_2 but more likely to endorse TILS_3 compared to higher-educated individuals. This pattern may reflect differences in how education levels influence social experiences and perceptions of loneliness.

The observed DIF for employment status on item TILS_3 implies that non-working individuals are more likely to endorse this item than working individuals, after controlling for overall loneliness. This result is difficult to compare with past studies since the present study is the first (to the best of our knowledge) to examine DIF in employment status using TILS. One explanation for the DIF in TILS_3 is that employment status influences responses to certain loneliness items, possibly due to differences in daily social interactions or feelings of isolation associated with not working.It is important to note that although DIF was detected in TILS_2 and TISL_3, this might not undermine the scale validity due to the following reasons: First, the magnitude of the DIF effects is small according to traditional guidelines [74], indicating minimal practical significance. Thus, the differences in item responses are not substantial enough to bias the overall assessment of loneliness across groups. Second, the potential impact of DIF is mitigated by the phenomenon of DIF cancellation [75, 76], where the effects of DIF in different directions across items offset each other at the scale level. This means that any slight bias introduced by one item is counterbalanced by another, resulting in a minimal effect on total score.

Significant associations with loneliness were found for neuroticism and extraversion traits, consistent with prior research [43, 77–80]. There was also a significant association between the Czech version of TILS with depression and anxiety, mirroring findings in a Spanish setting [72]. In addition, these findings are also consistent with theoretical works linking the often-discussed connection in literature between depression and anxiety with loneliness [20, 81–85]. Additionally, positive correlations with anxiety and depression emphasize the well-known link between loneliness and adverse mental health outcomes [86, 87].

The significant relationship was found between openness and loneliness. This is contrasting with results from a recent meta-analysis, which also did not find a significant relationship [88]. Other studies found a weaker association between loneliness and openness compared to the other Big Five traits [78, 89]. Lastly, the negative correlation with self-esteem aligns with existing literature suggesting that feelings of loneliness can undermine self-worth [90–92].

Lastly, a significant positive relationship was found between TILS score and loneliness measured by the DJGLS. However, the strength of this correlation differed, with a significantly stronger association observed between the TILS and emotional loneliness in contrast to the TILS association with social loneliness. Therefore, the TILS seems to principally assess the emotional component of loneliness instead of social component of loneliness. This finding was unexpected since the TILS is a short version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale which primarily captures social loneliness [33, 93]. This unexpected finding suggests that the TILS, in its brevity, might be emphasizing different dimensions of loneliness than the original version of the UCLA. It implies that while both the TILS and the full UCLA scale measure loneliness, they may not be directly interchangeable. This divergence points to the need for careful consideration of which scale is most appropriate depending on the context and whether the focus is on emotional or social aspects of loneliness. Altogether, this suggest that different versions of the UCLA might assess different aspects of loneliness [3, 33, 93].

Implications for Practice

The TILS emerges as a psychometrically sound instrument for evaluating loneliness. Its unidimensionality, robust internal consistency, satisfactory test-retest reliability, and robust IRT parameters render it a valuable tool for field practitioners [41, 73]. The advantage of this scale is the initial detection of people suffering from loneliness when used by field social workers or when communicating remotely with the client (telephone, online connection). In terms of correlations with many other problems, e.g., depression and anxiety, we can provide follow-up support and assessment by a psychologist or other specialist.

Implications for Research

The TILS as a simplified measure of loneliness can be used in a large test battery (e.g., during online data collection) as it poses a small response burden to participants. However, for a more in-depth examination of loneliness, the original 20-item UCLA or its abbreviated 10-item variant developed by Russell is recommended [73]. Moreover, due to decreased measurement precision in individuals with a higher average degree of loneliness, future research should either modify one of the TILS items or add a new item that would assess loneliness in these participants. This could consequently lead to increased sensitivity of the scale. Additionally, future studies should also explore the concurrent validity of TILS with the original 20-item UCLA.

Strengths and Limitations

Given that this constitutes an initial phase in the development of a loneliness scale within Czechia, several limitations are present. The scale has thus far been evaluated solely based on an online sample. Although the sample was extensive and diverse, further research on a representative sample of the Czech population is essential to generalize the current factor structures and validate the scale’s applicability. Additionally, smaller retest sample of only 50 participants might pose a limitation regarding the instrument stability a generalizability of responses. Next limitation lies in the absence of analysing of concurrent validity with original unabbreviated version of UCLA.

Since TILS is a self-reported scale, it would be very useful to compare high loneliness scores with cortisol levels. The association between diurnal cortisol, an index of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA), and the loneliness axis has been highlighted by a number of published studies [94, 95].

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrated that the TILS is a concise, valid, and reliable instrument, possessing the necessary properties in terms of factor structure and construct validity for assessing loneliness among the Czech population in a streamlined manner. The utilization of this scale may be particularly advantageous in online surveys or situations where the time and effort of respondents are crucial considerations for the research. The TILS is a valuable tool for practical applications, especially for the swift identification of loneliness in field settings or remote interactions. Further refinement of the TILS through modification or addition of items could enhance its sensitivity for nuanced research inquiries.

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt thanks to the numerous students who contributed to the data collection phase of our research. A comprehensive roster of these individuals can be accessed via the following URL: https://osf.io/mnjes/.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease

- TILS

Three Items Loneliness Scale

- UCLA

University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale

- CLS

Children's Loneliness Scale

- RTLS

Rasch-Type Loneliness Scale

- DJGLS

De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale

- SELSA

Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults

- DLS

Differential Loneliness Scale

- LACA

Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents

- RPLQ

Relational Provisions Loneliness Questionnaire

- PNDLS

Peer Network and Dyadic Loneliness Scale

- MASLO

Meta-Analytic Study of Loneliness

- OUSHI

Olomouc University Social Health Institute

- SD

Standard deviation

- BFI

Big Five Inventory

- BFI-N

Neuroticism sub-scale of the Big Five Inventory

- BFI-O

Openness sub-scale of the Big Five Inventory

- BFI-C

Conscientiousness sub-scale of the Big Five Inventory

- BFI-A

Agreeableness sub-scale of the Big Five Inventory

- BFI-E

Extraversion sub-scale of the Big Five Inventory

- OASIS

Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale

- ODSIS

Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale

- RSES

Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale

- CI

Confidence interval

- MAD

Median Absolute Deviation

- ICC

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- CFA

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- EFA

Exploratory Factor Analysis

- df

degrees of freedom

- CFI

Comparative Fit Index

- TLI

Tucker-Lewis index

- RMSEA

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

- SRMR

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual

- IRT

Item Response Theory

- BFGS

Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno algorithm

- HPA

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

Authors’ contributions

The authors made the following contributions. ZM: Conceptualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing; LN: Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing, statistical analysis; JH: Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing; PL: Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing; PT: Writing - Review & Editing, Writing - Original Draft Preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported from ERDF/ESF project DigiWELL (No. CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004583).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study, the study code, the Czech version of the Three Items Loneliness Scale, as well as supplementary materials are available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DM9KA.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Theology at Palacký University in Olomouc, Czech Republic, granted approval for the study design (Approval No. 2020/4). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research, and therapy. New York: Wiley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Dulmen MHM, Goossens L. Loneliness trajectories. J Adolesc. 2013;36:1247–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss R. Loneliness: the experience of emotional and social isolation. MIT Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maes M, Qualter P, Lodder GMA, Mund M. How (not) to measure loneliness: a review of the eight most commonly used scales. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19: 10816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surkalim DL, Luo M, Eres R, Gebel K, van Buskirk J, Bauman A, et al. The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;376:e067068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fokkema T, De Jong Gierveld J, Dykstra PA. Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. J Psychol. 2012;146:201–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiovitz-Ezra S, Ayalon L. Use of Direct Versus Indirect approaches to measure loneliness in later life. Res Aging. 2012;34:572–91. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demarinis S. Loneliness at epidemic levels in America. Explore (NY). 2020;16:278–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baarck J, d’Hombres B, Tintori G. Loneliness in Europe before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy. 2022;126:1124–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berlingieri F, Colagrossi M, Mauri C. Loneliness and social connectedness: insights from a new EU-wide survey. JRC Publications Repository; 2023. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC133351. Accessed 4 Feb 2024.

- 11.Hawkley LC. Loneliness and health. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8:22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Berntson GG. The anatomy of loneliness. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodfellow C, Willis M, Inchley J, Kharicha K, Leyland AH, Qualter P, et al. Mental health and loneliness in Scottish schools: a multilevel analysis of data from the health behaviour in school-aged children study. Br J Educ Psychol. 2023;93:608–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Victor CR, Yang K. The prevalence of loneliness among adults: a case study of the United Kingdom. J Psychol. 2012;146:85–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cacioppo JT, Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Alone in the crowd: the structure and spread of loneliness in a large Social Network. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97:977–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging. 2006;21:140–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erzen E, Çikrikci Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: a meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64:427–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luchetti M, Terracciano A, Aschwanden D, Lee JH, Stephan Y, Sutin AR. Loneliness is associated with risk of cognitive impairment in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35:794–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chau AKC, Zhu C, So SH-W. Loneliness and the psychosis continuum: a meta-analysis on positive psychotic experiences and a meta-analysis on negative psychotic experiences. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31:471–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Wang A, Eichi HR, Liebenthal E, Schutt R, Ongur D, et al. Loneliness of Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients in a multi-year mHealth study. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89:S222. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Relationship between loneliness, social isolation and modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a latent class analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75:749–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102:1009–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Algren MH, Ekholm O, Nielsen L, Ersbøll AK, Bak CK, Andersen PT. Social isolation, loneliness, socioeconomic status, and health-risk behaviour in deprived neighbourhoods in Denmark: a cross-sectional study. SSM Popul Health. 2020;10:100546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hajek A, König H-H. Asymmetric effects of obesity on loneliness among older germans. Longitudinal findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25:2293–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeytinoglu M, Wroblewski KE, Vokes TJ, Huisingh-Scheetz M, Hawkley LC, Huang ES. Association of Loneliness with falls: a study of Older US Adults Using the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2021;7:2333721421989217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet. 2018;391:426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter D. Practice: loneliness: a public health issue. Perspect Public Health. 2012;132:153–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML. Developing a measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess. 1978;42:290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asher SR, Hymel S, Renshaw PD. Loneliness in children. Child Dev. 1984;55:1456–64. [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Jong Gierveld J, Kamphuis F. The development of a rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 1985;9:289–99. [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiTommaso E, Spinner B. The development and initial validation of the Social and emotional loneliness scale for adults (SELSA). Pers Individ Dif. 1993;14:127–34. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt N, Sermat V. Measuring loneliness in different relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44:1038–47. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marcoen A, Goossens L, Caes P. Lonelines in pre-through late adolescence: exploring the contributions of a multidimensional approach. J Youth Adolescence. 1987;16:561–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomson LKH. The development of the relational provision loneliness questionnaire for children. Waterloo: University of Waterloo; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoza B, Bukowski WM, Beery S. Assessing peer network and dyadic loneliness. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2000;29:119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hays RD, DiMatteo MR. A short-form measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess. 1987;51:69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. A brief measure of loneliness suitable for use with adolescents. Psychol Rep. 1993;72 3 Pt 2:1379–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two Population-Based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26:655–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Czerwiński SK, Atroszko PA. A solution for factorial validity testing of three-item scales: an example of tau-equivalent strict measurement invariance of three-item loneliness scale. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:1652–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin C-Y, Tsai C-S, Jian C-R, Chao S-R, Wang P-W, Lin H-C, et al. Comparing the Psychometric properties among three versions of the UCLA loneliness scale in individuals with Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Igarashi T. Development of the Japanese version of the three-item loneliness scale. BMC Psychol. 2019;7:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trucharte A, Calderón L, Cerezo E, Contreras A, Peinado V, Valiente C. Three-item loneliness scale: psychometric properties and normative data of the Spanish version. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:7466–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Novak L, Malinakova K, Mikoska P, van Dijk JP, Dechterenko F, Ptacek R, et al. Psychometric analysis of the Czech Version of the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaafar MH, Villiers-Tuthill A, Lim MA, Ragunathan D, Morgan K. Validation of the malay version of the De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale. Australas J Ageing. 2020;39:e9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang B, Guo L. Reliability and validity of the Chinese Version of the De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale. Chin Gen Pract. 2019;22:4110–5. [Google Scholar]

- 48.John OP, Naumann LP, Soto CJ. Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and conceptual issues. In: Handbook of personality: theory and research. 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. p. 114–58.

- 49.Hřebíčková M, Jelínek M, Blatný M, Brom C, Burešová I, Graf S, et al. Big five inventory: Základní psychometrické charakteristiky české verze BFI-44 a BFI-10. Cesk Psychol. 2016;60:567–83. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Norman SB, Cissell SH, Means-Christensen AJ, Stein MB. Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:245–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sandora J, Novak L, Brnka R, van Dijk JP, Tavel P, Malinakova K. The abbreviated overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS) and the abbreviated overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale (ODSIS): Psychometric properties and evaluation of the Czech versions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18: 10337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bentley KH, Gallagher MW, Carl JR, Barlow DH. Development and validation of the overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale. Psychol Assess. 2014;26:815–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blatný M. Rosenbergova škála sebehodnocení: struktura globálního vztahu k sobě. Cesk Psychol. 1994;38:481–8. [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Jong Gierveld J, van Tilburg T. Manual of the loneliness scale. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buchta O, Malinakova K, Novak L, Juklova K, Meier Z, Tavel P. Psychometric analysis of the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale in Czech Republic. 2024. 10.31234/osf.io/u78ey.

- 57.Horn JL. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30:179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harmsen R, Helms-Lorenz M, Maulana R, van Veen K, van Veldhoven M. Measuring general and specific stress causes and stress responses among beginning secondary school teachers in the Netherlands. Int J Res Method Educ. 2019;42:91–108. [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Ark LA. Mokken Scale Analysis in R. J Stat Softw. 2007;20:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang Y, Lee J, Chen Z, Perry M, Cheung JH, Wang M. An item-response theory approach to safety climate measurement: the Liberty Mutual Safety Climate Short scales. Accid Anal Prev. 2017;103:96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim J, Wilson M. Polytomous item explanatory item response theory models. Educ Psychol Meas. 2020;80:726–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chalmers RP. Improving the crossing-SIBTEST statistic for detecting non-uniform DIF. Psychometrika. 2018;83:376–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim J, Oshima TC. Effect of multiple testing adjustment in Differential Item Functioning detection. Educ Psychol Meas. 2013;73:458–70. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams EJ. The comparison of regression variables. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 1959;21:396–9. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Novak L. psychtoolbox: tools for psychology research and psychometrics. 2022.

- 66.Peters GJ. Userfriendlyscience (UFS). 2017. 10.17605/OSF.IO/TXEQU.

- 67.Chalmers RP. Mirt: a Multidimensional Item Response Theory Package for the R environment. J Stat Softw. 2012;48:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R Package for Structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aust F, Barth M. papaja: Prepare reproducible APA journal articles with R Markdown. 2022.

- 70.Revelle W. psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. 2024.

- 71.Magis D, Béland S, Tuerlinckx F, De Boeck P. A general framework and an R package for the detection of dichotomous Differential Item Functioning. Behav Res Methods. 2010;42:847–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pedroso Chaparro M, del S, Márquez-González M, Fernandes-Pires JA, Gallego-Alberto Martín L, Jiménez-Gonzalo L, Nuevo R, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the three-item loneliness scale. Stud Psychol. 2022;43:311–31. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Elphinstone B. Identification of a suitable short-form of the UCLA-Loneliness Scale. Aust Psychol. 2018;53:107–15. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nieminen P. Application of standardized regression coefficient in Meta-Analysis. BioMedInformatics. 2022;2:434–58. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oliveri ME, Olson BF, Ercikan K, Zumbo BD. Methodologies for investigating item- and Test-Level Measurement Equivalence in International large-scale assessments. Int J Test. 2012;12:203–23. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wyse AE. DIF cancellation in the Rasch model. J Appl Meas. 2013;14:118–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Freilich CD, Mann FD, South SC, Krueger RF. Comparing phenotypic, genetic, and Environmental associations between personality and loneliness. J Res Pers. 2022;101: 104314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Freilich CD, Mann FD, Krueger RF. Comparing associations between personality and loneliness at midlife across three cultural groups. J Pers. 2023;91:653–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li S, Kong K, Zhang K, Niu H. The relation between college students’ neuroticism and loneliness: the chain mediating roles of self-efficacy, social avoidance and distress. Front Psychol. 2023;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wieczorek LL, Humberg S, Gerstorf D, Wagner J. Understanding loneliness in adolescence: a test of competing hypotheses on the interplay of Extraversion and Neuroticism. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chau AKC, So SH, Sun X, Zhu C, Chiu C-D, Chan RCK, et al. The co-occurrence of multidimensional loneliness with depression, social anxiety and paranoia in non-clinical young adults: A latent profile analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:931558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Igbokwe CC, Ejeh VJ, Agbaje OS, Umoke PIC, Iweama CN, Ozoemena EL. Prevalence of loneliness and association with depressive and anxiety symptoms among retirees in Northcentral Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Steiner JF, Ross C, Stiefel M, Mosen D, Banegas MP, Wall AE, et al. Association between changes in loneliness identified through screening and changes in depression or anxiety in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70:3458–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sun J-J, Chang Y-J. Associations of problematic binge-watching with Depression, Social Interaction anxiety, and loneliness. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang H-H, Jiang Y-Y, Rao W-W, Zhang Q-E, Qin M-Z, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of Depression among empty-nest Elderly in China: a Meta-analysis of Observational studies. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11: 608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bessaha M, Mushonga D, Fedina L, DeVylder J. Association between Loneliness, Mental Health Symptoms, and treatment use among emerging adults. Health Soc Work. 2023;48:133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lyyra N, Thorsteinsson EB, Eriksson C, Madsen KR, Tolvanen A, Löfstedt P, et al. The Association between Loneliness, Mental Well-Being, and self-esteem among adolescents in four nordic countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18: 7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Buecker S, Maes M, Denissen JJA, Luhmann M. Loneliness and the big five personality traits: a Meta–analysis. Eur J Pers. 2020;34:8–28. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Erevik EK, Vedaa Ø, Pallesen S, Hysing M, Sivertsen B. The five-factor model’s personality traits and social and emotional loneliness: two large-scale studies among Norwegian students. Pers Individ Dif. 2023;207:112115. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moksnes UK, Bjørnsen HN, Ringdal R, Eilertsen M-EB, Espnes GA. Association between loneliness, self-esteem and outcome of life satisfaction in Norwegian adolescents aged 15–21. Scand J Public Health. 2022;50:1089–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ti Y, Wei J, Hao Z. The longitudinal association between loneliness and self-esteem among Chinese college freshmen. Pers Individ Dif. 2022;193:111613. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Trong Dam VA, Do HN, Thi Vu TB, Vu KL, Do HM, Thi Nguyen NT, et al. Associations between parent-child relationship, self-esteem, and resilience with life satisfaction and mental wellbeing of adolescents. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1012337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cramer KM, Barry JE. Conceptualizations and measures of loneliness: a comparison of subscales. Pers Individ Dif. 1999;27:491–502. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jopling E, Rnic K, Tracy A, LeMoult J. Impact of loneliness on diurnal cortisol in youth. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;132: 105345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schutter N, Holwerda TJ, Stek ML, Dekker JJM, Rhebergen D, Comijs HC. Loneliness in older adults is associated with diminished cortisol output. J Psychosom Res. 2017;95:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study, the study code, the Czech version of the Three Items Loneliness Scale, as well as supplementary materials are available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DM9KA.