Abstract

Background

Vaginal colonization by Candida can lead to vulvovaginal candidiasis, which is the second most prevalent vaginal condition globally. It is frequently associated with sepsis and adverse neonatal outcomes in pregnant women. This issue is worsening in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Ethiopia. However, evidence of the existing problem is very scarce yet crucial. Thus, this study aimed to determine the vaginal colonization and vertical transmission of Candida species and their associated factors among pregnant women and their neonates in public health facilities of northeast Ethiopia.

Methods

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted at selected public health facilities in Dessie town from April 1 to June 30, 2023, among 348 pregnant women and their newborns, using convenience sampling techniques. Socio-demographic, and clinical-related data were collected using a pre-tested, semi-structured questionnaire. Vaginal swab samples from pregnant women and pooled swabs from the external ear, nasal area, and umbilical areas of the newborns were collected and transported using Amies transport media. The samples were inoculated into Sabouraud Dextrose Agar for isolation, followed by inoculation onto a standard CHROM agar Candida plate for species identification, and a germ-tube test confirmed pseudophyphae of C.albicans. Data was entered into Epi Data version 4.6.0 software and exported and analyzed by SPSS version 25.0. A stepwise logistic regression model was used to identify the associated factors. Variables with p < 0.05 and their 95% confidence interval were considered statistically significant.

Result

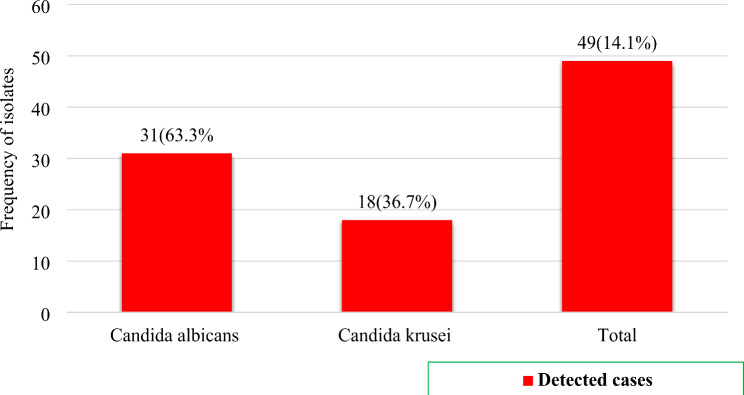

A total of 348 pregnant women attending vaginal delivery were included in the study. The maternal and neonatal colonization rates of Candida species were 14.1% (49/348) and 6.3% (22/348), respectively. The overall proportion of vertical transmission of Candida species was 44.9% (22/49, 95% CI: 41.2, 49.7). Among Candida isolates, 63.3% (31/49) were C. albicans and 36.7% (18/49) were C. krusei. Gestational diabetes mellitus (AOR: 4.2, 95% CI: 1.23–38.6, P = 0.047) and HIV (AOR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.11–6.12, P = 0.049) were independently associated with maternal colonization of Candida species. Moreover, rural residence (AOR = 3.6, 95% CI: 1.37–9.5, P = 0.010) and maternal age above 28 years (AOR = 2.39, 95% CI: 1.97–5.89, P = 0.048) were independently associated with vertical transmission of Candida species.

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight the need for effective screening and treatment of Candida colonization during antenatal care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-024-07103-9.

Keywords: Candida, Ethiopia, Neonatal colonization, Pregnant women, Vaginal colonization, Vertical Transmission

Introduction

Candida is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that comprises over 350 heterogeneous species, but only a small number have been linked to human disease [1]. Candida albicans (C. albicans) is the most common fungal pathogen, accounting for 90% of candidiasis cases, while Candida glabrata (C. glabrata) is responsible for the majority of the remaining instances [2]. Candida is the most common pathogen causing fungal cervicovaginal infections in pregnant women, affecting up to 30% of them, with a potential risk of reaching 50% in the third trimester [3].

Pregnancy alters the vaginal environment and raises the risk of candidiasis due to elevated levels of progesterone and estrogen hormones. Thus, maternal vaginal colonization by Candida can lead to vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), which is a major risk factor for Candida colonization of the newborn. Thus, vertical transmission of Candida can occur as a result of contamination of neonates when mothers with vaginal Candida colonization give birth as well as through contact with medical staff within the first days of life [4, 5]. These fungal cervicovaginal infections can lead to common complications such as endometritis, intrauterine infection, and chorioamnionitis [6]. The chance of spontaneous preterm birth (PTB) and late miscarriage due to candidiasis in women with asymptomatic vaginal thrush is still under study. Moreover, evidence has shown the risk of infant transmission during childbirth among women with debilitating Candida infections [7]. Along with unfavorable pregnancy outcomes such as preterm labor and chorioamnionitis, premature rupture of membranes is another concern. On the other hand, congenital cutaneous infections have been documented for decades as uncommon occurrences throughout pregnancy. Preterm births occurred more frequently in women with untreated asymptomatic candidiasis compared to those without the condition [8–10].

Vaginal colonization of Candida is typically unrecognized or asymptomatic, but it leads to an imbalance in the vaginal microbiome and overgrowth of yeasts in the vaginal mucus membrane. This can further result in vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), which is characterized by symptoms such as burning, itching, painful urination, vaginal discharge, and an inflammatory immune response. VVC progresses through multiple stages of development: the fungal attachment to epithelial cells, invasion, biofilm formation, and release of virulence factors. Approximately 75% of women will experience VVC at some point in their life; globally, 8% will experience VVC on a recurrent basis. VVC is a common form of vaginitis [11–13].

The risk of VVC is increased not only by the pregnancy condition itself but also by the co-existence of comorbidities such as diabetes, immunosuppression, HIV infection, contraception, and antibiotic use, including corticosteroid medications. Furthermore, pregnancy-related factors such as decreased cell-mediated immunity, elevated vaginal mucosal glycogen synthesis, and elevated estrogen levels will result in both asymptomatic colonization and a higher risk of VVC [14, 15]. Therefore, early detection and management of VVC during pregnancy are essential to prevent unwanted pregnancy outcomes [16].

According to recent evidence, approximately 75% of women have had at least one episode of VVC, with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) occurring in 5–10% of cases. Additionally, an estimated 138 million women are affected by RVVC annually worldwide [12, 17]. This condition also imposes a significant healthcare cost burden and productivity risks, with the problem worsening in low- and middle-income countries, including Ethiopia. However, the scarcity of data on Candida infections among pregnant women in Ethiopia, especially in the context of vaginal colonization and vertical transmission, hampers effective interventions to address associated risks. Understanding the prevalence and factors contributing to Candida colonization is crucial for developing targeted screening and management strategies to safeguard the health of pregnant women and their neonates in the region. Therefore, comprehensive data on maternal vaginal Candida colonization and its correlation with vertical transmission to neonates are important in light of the lack of available evidence to make informed decisions and provide evidence-based public health interventions. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind in Ethiopia. Thus, the aim of the present study was to determine the magnitude of vaginal colonization, vertical transmission rate, and associated factors of Candida species among pregnant women and their neonates at public health facilities in northeastern Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study area, design and period

This facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted from April 1 to June 30, 2023 in public health facilities in Dessie town, located 401 km from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. The total population of the town is estimated to be 257,126; 49.5% are females and 23.47% are of reproductive age. Dessie town has seven public health centers and one specialized hospital, Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DCSH), which provides different healthcare services for eastern-Amhara and Afar. DCSH has a total of 707 healthcare workers, of whom 79 work in the obstetrics and gynecology ward. Likewise, Dessie Health Center (DHC) obstetrics and gynecology ward has five healthcare workers, including MSc, BSc, and diploma midwives. According to the 2022 annual report of Dessie town Health Department, 13,177 (661 from DHC and 12446 from DCSH) delivery services were documented while other health facilities have reported low delivery service compared to DHC and DCSH. Thus, DCSH and DHC were selected for this study based on their high client flow for delivery services.

Population and eligibility

Among pregnant women who were attending their antenatal care (ANC) service in the selected health facilities, those who were admitted at DCSH and DHC for vaginal delivery service and their newborns were considered eligible for inclusion in the study. Furthermore, pregnant women who were taking antimicrobial drugs within two weeks prior to recruitment to the study and those who gave birth via cesarean-section delivery were excluded. Neonates were included in this study to assess the burden of maternal to neonatal transmission of Candida species, and to assess the association between maternal vaginal colonization and vertical transmission of Candida species.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula considering 25% prevalence of Candida species reported from pregnant women in Debre Markos [15], a 0.05 margin of error (d), and a 95% confidence interval.

Where n = minimum sample size required for the study; Za/2 =1.96, (95% confidence interval), P = proportion of the problem (0.25), and d = margin of error (5%).

= 288

= 288

Considering a 10% non-response rate, the minimum sample size was 317, which was proportionally allocated into DCSH and DHC based on their last year’s delivery service performance in March, April and May, 2022. However, to increase the generalizability of the findings we used 348 pregnant women and their newborn pairs in the final analysis considering the proportional allocation based on the available resources to undertake the laboratory investigation. A convenience sampling technique was used to select the study participants.

Study variables

The outcome variables of this study were vaginal colonization (categorized as 1 = Yes and 0 = No) and vertical transmission of Candida species (categorized as 1 = Yes and 0 = No). Additionally, socio-demographic characteristics (age, residence, marital status, educational status, occupation, source of drinking water, domestic animal in the house, sex and weight of the newborn, 5-minute APGAR score, and status of newborn at delivery), obstetrics-related characteristics (gestational age, number of current ANC visits, history of antibiotic use during the current pregnancy, current gestational hyperbaton, current gestational DM, type of gravida, history of abortion, history of stillbirth, premature rupture of membrane, duration of labor, fever during labor, and meconium stained amniotic fluid) and clinical characteristics (history of hospitalization in the past 3 months, HIV status, syphilis status, history of urinary tract infection (UTI) at current pregnancy, presence of vaginal discharge, and history of sexually transmitted infection at current pregnancy) were considered as explanatory variables.

Data collection techniques and procedure

Socio-demographic and clinical data collection

Socio-demographic, obstetric, and clinically related data from pregnant women and their newborns were collected using a pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire through face-to-face interviews by attending midwives. This was complemented with a medical record review after obtaining informed consent and assent (Supplementary File 1). Data regarding HIV and syphilis status were obtained from the women’s follow-up medical records.

Specimen collection and transportation

Swab samples were taken from the lower vagina region of pregnant mothers during labor by the attending midwife using a sterile cotton swab (JL180201, JOYMED, China) in accordance with the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [18] and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [19]. The swab was carefully inserted into the vagina, avoiding contamination from the cervical mucus. Then, it was gently pressed against the vaginal walls and rotated to ensure a thorough coating. The midwives exercised caution in removing the swab to avoid contact with the skin and the anal area. Similarly, pooled swabs from the external ear, nasal area, and umbilical areas of the newborn were collected within 15 min after delivery to asses vertical transmission. Both swabs were placed in Amies transport medium without charcoal (CM0425, OXOID, UK) and transported in a cold temperature of 4–8 °C within 4 h to the microbiology laboratory of the Amhara Public Health Institute (APHI) Dessie branch for processing.

Specimen processing and identification

A swab was inoculated on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) (CM0041, Oxoid, UK), and incubated at 37 °C for 24 to 48 h. After growth was observed on SDA, white, creamy colonies were identified and streaked on a CHROM agar Candida plate (BBL257480, BD Company, Belgium), which was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Different Candida species were identified based on the reaction between their specific enzymes and a chromogenic substrate, resulting in the formation of different colored colonies. Green colonies were identified as C. albicans and pink colonies with a whitish border were identified as C. krusei [20]. Furthermore, a germ-tube test was performed to differentiate C. albicans from nonalbicans Candida species. A single pure colony was mixed with 0.5 ml of calf serum and incubated at 37 °C for 2 to 4 h. A drop of serum was transferred to a microscopic slide followed by covering with a coverslip, and it was examined microscopically under 10X and 40X objectives using Olympus CX23 binocular microscope. Finally, the presence of a short filamentous structure (hyphae) extending laterally from the yeast cells with no constriction at the point of origin was considered a positive germ tube and the yeast was identified as C. albicans. A negative germ tube result was noted when there was no filamentous structure (hyphae) arising from the yeast cells, or when short hyphal extensions with constriction at the point of origin were present, identifying the yeast as C. krusei [21].

Confirmation of identified Candida species

green-colonies on CHROM agar and positive for germ tube were identified as C. albicans while pink and spreading colonies were identified as C. krusei.

Operational definition

CandidaColonization: Is defined as the presence of any Candida species isolated from vaginal swab cultures of pregnant women, regardless of symptoms.

Vertical Transmission: Is defined as the detection/isolation of the identical Candida species both in neonates and the mothers’ vaginal cultures obtained during pregnancy in cases of vaginal delivery.

Quality assurance

All quality control measures were conducted, starting from the development of a semi-structured questionnaire in the English language and translating it into the local language (Amharic). Then, it was translated back to the English language to assure consistency followed by a pre-test on 5% of the total sample size at Kombolcha General Hospital, and modifications to questions were made accordingly. Additionally, half-day training was given to the data collectors. Furthermore, content and face validity were performed by field experts. Standard operating procedures and the manufacturer’s instructions for media preparation and handling were strictly followed during specimen collection, transportation, and processing. The collected data were checked daily for consistency and accuracy. A swab specimen not labeled, delayed beyond 24 h, or not transported at the appropriate temperature was rejected. The sterility of culture media was checked by incubating 5% of the media without inoculation [22]. Moreover, visual inspections were applied to prepare and store media for holes, uneven filling, signs of freezing, bubbles, and corrosion.

Data processing and statistical analysis

The data were coded and entered into Epi Data version 4.6.0 software and exported and analyzed by SPSS version 25.0 (IMB, USA). Descriptive statistics were computed to describe relevant variables and presented in tables and figures. The reliability coefficient was checked using Cronbach’s alpha (p = 0.877). Bi-variable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the possible associated factors with outcome variables. Then, variables with a p-value ≤ 0.3 were further entered into the multivariable analysis. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test was computed, and indicated a good fitting model for analysis(P > 0.05). Finally, variables with an adjusted odd ratio and p-value less than 0.05 with a 95% CI were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The study was ethically approved by the Bahir Dar University College of Medicine and Health Science Ethical Review Board (Protocol number 749/2023). After explaining the purpose of the study, DCSH and DHC granted a permission letter. Written informed consent was obtained from the pregnant mother along with assents for the newborns, prior to the commencement of the study. This included an explanation of the purpose, the benefits, and the possible risks of the study. To maintain confidentiality, personal identifiers were utilized, and data were retrieved only for the purpose of the study. For each confirmed positive result, the clinician responsible for the participant was informed to treat the positive cases based on the findings using an appropriate treatment protocol.

Result

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of pregnant women

A total of 348 pregnant women attending vaginal delivery were included in this study. The age of the mothers ranged from 19 to 39 years, with a median and interquartile range of 28.1 ± 5.08 years. More than half (54.9%, 191/348) were aged 28 or younger, 263/348 (75.6%) were urban dwellers, 311/348 (89.4%) were married, 123/348 (35.3%) had a high-grade education level, 225/348 (64.7%) were housewives, 302/348 (86.8%) used public tap water as a source of drinking water, and 271/348 (77.9%) had no domestic animals in their households. Regarding the clinical characteristics, 21/348 (6.0%), 14/348 (4%), 10/348 (2.9%), and 48/348 (13.8%) pregnant women had a history of hospitalization in the past 3 months, were positive for HIV, positive for syphilis, and had a history of UTI during the current pregnancy, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of pregnant women attending public health facilities in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023 (N = 348)

| Variables | Category | Frequency (N) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health facility | DCSH | 255 | 73.3 |

| DHC | 93 | 26.7 | |

| Age | ≤ 28yrs | 191 | 54.9 |

| > 28yrs | 157 | 45.1 | |

| Residence | Urban | 263 | 75.6 |

| Rural | 85 | 24.4 | |

| Marital status | Single | 19 | 5.5 |

| Married | 211 | 60.6 | |

| Divorced | 14 | 4.0 | |

| Widowed | 4 | 1.1 | |

| Educational status | Unable to read & write | 27 | 7.8 |

| Primary | 95 | 27.3 | |

| Secondary | 103 | 29.6 | |

| Tertiary | 123 | 35.3 | |

| Occupation | Civil servant | 40 | 11.5 |

| Student | 14 | 4.0 | |

| Farmer | 18 | 5.2 | |

| House wife | 225 | 64.7 | |

| Merchant | 36 | 10.3 | |

| Daily labor | 15 | 4.3 | |

| Source of drinking water | Public tape water | 302 | 86.8 |

| Spring tape water | 21 | 6.0 | |

| Private tape water | 25 | 7.2 | |

|

Domestic animal in the house |

Yes | 77 | 22.1 |

| No | 271 | 77.9 | |

| History of hospitalization | Yes | 21 | 6.0 |

| No | 327 | 94.0 | |

| HIV status | Yes | 14 | 4.0 |

| No | 334 | 96.0 | |

| Syphilis status | Yes | 10 | 2.9 |

| No | 338 | 97.1 | |

| History of UTI at current pregnancy | Yes | 48 | 13.8 |

| No | 300 | 86.2 | |

| Vaginal discharge | Yes | 3 | 0.9 |

| No | 345 | 99.1 | |

| History of STI | Yes | 8 | 2.3 |

| No | 340 | 97.7 |

Key: DCSH: Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, DHC: Dessie Health Center, UTI: Urinary Tract Infection, STI: Sexually Transmitted Infection, and HIV: Human Immune deficiency Virus

Obstetrics-related characteristics and vaginal colonization of Candida

Of 348 women, 50 (14.4%) delivered before 37 weeks of gestation; 29 (8.3%) and 19 (5.5%) had a history of abortion and stillbirth in their respective orders. Of the total pregnant women, 36 (10.3%) and 23(6.6%) had experienced PROM and meconium-stained amniotic fluid during delivery, respectively. The percentage of Candida species colonization among pregnant women was 30% (3/10), 50.0% (2/4), and 20.9% (9/43), respectively among women with current gestational hyperbaton, gestational DM, and fever during labor (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetrics-related characteristics and colonization of Candida species among pregnant women in Public Health Facilities of Dessie Town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023

| Variables | Category | Number of pregnant women, N (%) | Mothers culture positives, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gestational age Gestational age |

< 37 | 50(14.4) | 5(10) |

| ≥ 37 | 298(85.6) | 44(14.8) | |

| Number of ANC visit | < 4 | 115(33) | 14(12.2) |

| ≥ 4 | 233(67) | 35(15.0) | |

| History of antibiotic use during the current pregnancy | Yes | 18(5.2) | 0(0) |

| No | 330(94.8) | 49(14.8) | |

| Current gestational hyperbaton | Yes | 10(2.9) | 3(30.0) |

| No | 338(97.1) | 46(13.6) | |

| Current gestational DM | Yes | 4(11) | 2(50.0) |

| No | 344(98.9) | 47(13.7) | |

| Type of gravida | Primigravida | 108(31.0) | 12(11.1) |

| Multigravida | 240(69.0) | 37(15.4) | |

| History of abortion | Yes | 29(8.3) | 2(8.3) |

| No | 319(91.7) | 47(14.5) | |

| History of stillbirth | Yes | 19(5.5) | 3(18.8) |

| No | 329(94.5) | 46(13.9) | |

| PROM | Yes | 36(10.3) | 8(18.6) |

| No | 312(89.7) | 41(13.4) | |

| Duration of labor (in hour) | ≤ 12 | 202(58.0) | 26(12.9) |

| > 12 | 146(42.0) | 23(15.8) | |

| Fever during labor | Yes | 43(12.4) | 9(20.9) |

| No | 305(87.6) | 40(13.1) | |

| Meconium-stained amniotic fluid | Yes | 23(6.6) | 2(8.7) |

| No | 325(93.4) | 47(14.5) |

Key: ANC: Ante-natal care, DM: Diabetes mellitus, PROM: Premature rupture of membrane

Socio-demographic characteristics and Candida colonization of newborns

Of the 348 newborns, 182 (52.3%) were female, and 56 (16.1%) had low birth weight (≤ 2500 g). The percentage of Candida species colonization was higher among those with < 2.5 kg birth weights (7/56, 12.5%) vs. > 2.5 kg (15/292, 5.1%), and 5/31(16.1%) had an APGAR score of < 7. Moreover, newborns who had a Candida species colonization were alive (Table 3).

Table 3.

Socio-demographic characteristics and colonization of Candida species among newborns in Public Health Facilities in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023

| Variable | Category | Frequency of newborns, N(%) | Fungal culture positive Newborns, N(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of newborn | Male | 166 (47.7) | 13(7.8) |

| Female | 182 (52.3) | 9(4.9) | |

| Weight of newborns (Grams) | < 2500 | 56 (16.1) | 7(12.5) |

| ≥ 2500 | 292 (83.9) | 15(5.1) | |

| 5th minute APGAR score | < 7 | 31 (8.9) | 5(16.1) |

| 7–10 | 317 (91.1) | 17(5.4) | |

| Status of newborn at birth | Alive | 346 (99.4) | 22(6.4) |

| Dead | 2 (0.6) | 0(0.0) |

APGAR: appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, respiration

Vaginal colonization and associated factors of Candida species among pregnant women

The magnitude of maternal colonization of Candida species was 14.1% (n = 49; 95% CI: 10.8, 18.2%). Only two Candida spp. namely, C. albicans and C. krusei were detected in the present study with 63.3% and 36.7%, respective prevalence rates among the culture positive women (Fig-1).

Fig. 1.

Vaginal colonization of Candida species among pregnant women in public health facilities in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023

The proportion of vaginal colonization of Candida species among pregnant women with a history of current gestational HTN was 30% (3/10). Similarly, based on residence the proportion of colonization rate was 13.3% and 16.5%, respectively among urban and rural resident women. Of the pregnant women with vaginal colonization of Candida species, 18.8% had a history of stillbirth and 8.3% had a history of abortion. Furthermore, bivariate and multivariable analyses were performed to identify the factors associated with vaginal colonization of Candida species. In bivariate analysis, only one variable i.e., HIV status was associated with vaginal colonization. However, after computing six factors (such as age group, current gestational HTN, type of gravida, fever during labor, HIV status and gestational DM) with a P-value less than 0.3, gestational DM (AOR: 4.2, 95% CI: 1.23–38.6, P = 0.047) and HIV (AOR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.11–6.12, P = 0.049) showed statistically significant association with maternal Candida colonization. The likelihood of vaginal colonization with Candida spp. among HIV-positive pregnant women was 1.58 times higher than HIV-negative women. Likewise, the odds of Candida spp. vaginal colonization among pregnant women with gestational DM was 4.2 times higher than those without gestational DM (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with vaginal colonization of Candida species in public health facilities of Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023

| Factors | Vaginal colonization of Candida species | COR (95% CI) | P-value | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |||||||

| Age (Year) | ≤ 28 | 23(12.0) | 168(88.0) | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 28 | 26(16.6) | 131(83.4) | 1.45(0.79–2.66) | 0.23 | 1.39(0.75–2.56) | 0.291 | ||

| Residence | Urban | 35(13.3) | 228(86.7) | 1 | ||||

| Rural | 14(16.5) | 71(83.5) | 1.28(0.65–2.52) | 0.467 | ||||

| Educational status | Unable to read and write | 4(14.8) | 23(85.2) | 1.2(0.4–3.8) | 0.803 | |||

| Elementary | 12(12.6) | 83(87.4) | 0.9(0.4–2.2) | 0.934 | ||||

| Secondary | 17(16.5) | 86(83.5) | 1.3(0.6–2.7) | 0.459 | ||||

| High grade | 16(13.0) | 107(87.0) | 1 | |||||

| Gestational age (week) | < 37 | 5(10.0) | 45(90.0) | 0.64(0.24–1.7) | 0.373 | |||

| ≥ 37 | 44(14.8) | 245(85.2) | 1 | |||||

| Number of ANC visit | < 4 | 14(12.2) | 101(87.8) | 0.78(0.4–1.5) | 0.473 | |||

| ≥ 4 | 35(15.0) | 198(85.0) | 1 | |||||

| Current gestational HTN | Yes | 3(30.0) | 7(70.0) | 2.7(0.67–10.89) | 0.152 | 2.8(0.7–11.3) | 0.143 | |

| No | 46(13.6) | 292(86.4) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Type of gravida | Primigravida | 12(11.1) | 96(88.9) | 1 | 0.287 | |||

| Multigravida | 37(15.4) | 203(84.6) | 1.46(0.73–2.92) | 1.1(0.45–2.65) | 0.834 | |||

| History of abortion | Yes | 2(8.3) | 22(91.7) | 0.54(0.1–2.35) | 0.409 | |||

| No | 47(14.5) | 277(85.5) | 1 | |||||

| History of still birth | Yes | 3(18.8) | 13(81.2) | 1.4(0.4–5.2) | 0.584 | |||

| No | 46(13.9) | 286(86.1) | 1 | |||||

| PROM | Yes | 8(18.6) | 35(81.4) | 1.47(0.64–3.39) | 0.365 | |||

| No | 41(13.4) | 264(86.6) | 1 | |||||

| Fever during labor | Yes | 9(20.9) | 34(79.1) | 1.75(0.78–3.93) | 0.172 | 1.39(0.58–3.36) | 0.463 | |

| No | 40(13.1) | 265(86.9) | 1 | |||||

| Meconium-stained amniotic fluid | Yes | 2(8.7) | 21(91.3) | 0.56(0.13–2.48) | 0.448 | |||

| No | 47(14.5) | 278(85.5) | 1 | |||||

| History of hospitalization in the past 3 months | Yes | 4(19.0) | 17(81.0) | 1.48(0.47–4.58) | 0.502 | |||

| No | 45(13.8) | 282(86.2) | 1 | |||||

| HIV status | Positive | 3(21.4) | 11(78.6) | 1.71(1.12–6.35) | 0.042 | 1.58(1.11–6.12) | 0.049* | |

| Negative | 46(13.8) | 288(86.2) | 1 | |||||

| Gestational DM | Yes | 2(50.0) | 2(50.0) | 6.3(0.97–45.9) | 0.056 | 4.2(1.23–38.6) | 0.047* | |

| No | 47(13.7) | 297(86.3) | 1 | |||||

| History of UTI at current pregnancy | Yes | 9(18.8) | 39(81.2) | 1.5(0.67–3.3) | 0.319 | |||

| No | 40(13.3) | 260(86.7) | 1 | |||||

| History of STI | Yes | 1(12.5) | 7(87.5) | 0.87(0.11–7.22) | 0.897 | |||

| No | 48(14.1) | 292(85.9) | 1 | |||||

Key: ANC: Ante Natal Care, DM: Diabetes Miletus, HIV: Human Immune Virus, PROM: Premature rupture of membrane, STI: Sexually Transmitted Disease, UTI: Urinary Tract infection, (*): significant at P-value < 0.05, 1: reference category, AOR: Adjusted Odd Ratio, COR: Crude Odds Ratio, CL: confidence interval

Vertical transmission and associated factors of Candida species among newborns

The magnitude of neonatal colonization of Candida species was 6.3% (n = 22; 95% CI: 25.34.2, 9.4%). The overall proportion of vertical transmission of Candida spp. was 44.9% (22/49, 95% CI: 41.2, 49.7). The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) showed a positive association between maternal colonization and the vertical transmission rates of Candida spp. with r > 0.50 and P < 0.001. Maternal age group, residence, educational status, type of gravida, weight of newborns, gestational age, number of ANC visits and 5-minute APGAR score were computed in multivariable logistic regression analysis. Finally, only maternal age and residence were significantly associated with the vertical transmission of Candida spp. The likelihood of Candida spp. vertical transmission to newborns was 3.6 times (AOR = 3.6, 95% CI: 1.37–9.5, P = 0.010) higher for those newborns delivered by a pregnant mother whose age was > 28 years old. On the other hand, the odds of Candida spp. vertical transmission were 2.39 times (AOR = 2.39, 95% CI: 1.97–5.89, P = 0.048) higher for those newborns born in rural areas when compared to their counterparts (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with vertical transmission of Candidaspecies to the newborns in public health facilities in Dessie town, Northeast Ethiopia, 2023. (n = 193)

| Factors | Vertical transmission | COR (95% CI) | P-value | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||||||||

| Age (Year) | ≤ 28 | 6(3.1) | 185(96.9) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| > 28 | 16(10.2) | 141(89.8) | 3.49(1.3–9.17) | 0.011 | 3.6(1.37–9.5) | 0.010* | |||||||

| Residence | Urban | 13(4.9) | 250(95.1) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Rural | 9(10.6) | 76(89.4) | 2.27(1.94–5.53) | 0.069 | 2.39(1.97–5.89) | 0.048* | |||||||

| Educational status | Unable to read and write | 4(14.8) | 23(85.2) | 4.1(1.02–16.5) | 0.046 | 1.26(0.26–6.25) | 0.775 | ||||||

| Elementary | 6(6.3) | 89(93.7) | 1.59(0.47–5.4) | 0.455 | 1.02(0.28–3.68) | 0.976 | |||||||

| Secondary | 7(6.8) | 96(93.2) | 1.7(0.5–5.59) | 0.367 | 1.67(0.49–5.71) | 0.413 | |||||||

| High grade | 5(4.1) | 118(95.9) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Gestational age (Week) | < 37 | 5(10.0) | 45(90.0) | 1.84(0.65–5.23) | 0.264 | 2.25(0.75–6.74) | 0.146 | ||||||

| ≥ 37 | 17(5.7) | 281(94.3) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Number of ANC visit | < 4 | 5(4.3) | 110(95.7) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| ≥ 4 | 17(7.3) | 216(92.7) | 1.7(0.6–4.8) | 0.293 | 1.95(0.67–5.66) | 0.220 | |||||||

| Current gestational HTN | Yes | 1(10.0) | 9(90.0) | 1.67(0.2-13.87) | 0.631 | ||||||||

| No | 21(6.2) | 317(93.8) | 1 | ||||||||||

| Type of gravida | Primigravida | 2(1.9) | 106(98.1) | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Multigravida | 20(8.3) | 220(91.7) | 4.8(1.1–20.9) | 0.036 | 1.9(0.58–6.23) | 0.288 | |||||||

| History of abortion | Yes | 1(4.2) | 23(95.8) | 0.6(0.08–4.8) | 0.656 | ||||||||

| No | 21(6.5) | 303(93.5) | 1 | ||||||||||

| Duration of labor (Hour) | ≤ 12 | 13(6.4) | 189(93.6) | 1.05(0.4–2.5) | 0.918 | ||||||||

| > 12 | 9(6.2) | 137(93.8) | 1 | ||||||||||

| History of hospitalization in the past 3 months | Yes | 1(4.8) | 20(95.2) | 0.73(0.1–5.69) | 0.763 | ||||||||

| No | 21(6.4) | 306(93.6) | 1 | ||||||||||

| HIV status | Positive | 1(7.1) | 13(92.9) | 1.15(0.14–9.19) | 0.898 | ||||||||

| Negative | 21(6.3) | 313(93.7) | 1 | ||||||||||

| History of UTI at current pregnancy | Yes | 4(8.3) | 44(91.7) | 1.3(0.17–10.7) | 0.763 | ||||||||

| No | 18(6.0) | 282(94.0) | 1 | ||||||||||

| Weight of newborns (Gram) | < 2500 | 7(12.5) | 49(87.5) | 2.64(1.02–6.8) | 0.045 | 1.78(0.64–4.97) | 0.272 | ||||||

| ≥ 2500 | 15(5.1) | 277(94.9) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 5th minute APGAR score | < 7 | 5(16.1) | 26(83.9) | 3.4(1.16–9.9) | 0.026 | 2.1(0.65–6.8) | 0.215 | ||||||

| 7–10 | 17(5.4) | 300(94.6) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

Key: ANC: Ante Natal Care, DM: Diabetes Miletus, HIV: Human Immune Virus, PROM: Premature rupture of membrane, STI: Sexually Transmitted Disease, UTI: Urinary Tract Infection, (*): significant at P-value < 0.05, 1: reference category, AOR: Adjusted Odd Ratio, COR: Crude Odds Ratio, CL: confidence interval

.4. Discussion

Pathogens that colonize the vagina during pregnancy can affect the female reproductive tract, leading to vaginal discharge and related complications. Therefore, early detection of maternal vaginal colonization with Candida species plays a significant role in preventing neonatal morbidity and mortality. In the present study, the maternal vaginal colonization of Candida species was 14.1% (95% CI: 10.8%, 19.1%), which was higher than the study conducted in Iran (9.8%) [23]. Although we identified the species of Candida, their proportions were determined from the total species, which is unlikely to align with the findings of Iran, where the colonization rate was due to C. albicans only. This methodological approach could explain the discrepancy. Furthermore, the prevalence of Candida among pregnant women in this study was lower than findings reported as 43.05% from S. Africa [24], 72.37% from India [25], 30% from Nigeria [26] and 42.7% from Kenya [27] as well as 27.9%, 28.1% and 38.2% Candida colonization using wet mount, microscopy of Gram-stain smears and qPCR, respectively in Democratic Republic of Congo [28]. This discrepancy might be associated with the difference in immune status of women included in the study, awareness, hygienic practices and the presence of underlying comorbidities such as DM and HIV.

In the current study, the prevalence of C. albicans was 63.3%, consistent with previous evidence that C. albicans is the most frequent causative agent of vaginal Candida infection [24, 29–31]. However, this finding contradicts other studies where non-albicans Candida are the predominant yeasts causing vaginal infections [25, 27, 29, 32]. This inconsistency could be attributed to variations in geographic areas or settings related to growth factors such as climatic factors and hygienic practices; the immune response of infected individuals; differences in the presence and type of comorbidities; and methodological issues in studies. Moreover, the present study showed the importance of considering non-albicans Candida during the management of candidiasis. Thus, the prevalence of C. krusei (36.7%) implies the need for proper selection of antifungal drugs, as the resistance level of this species is high. This also indicates the need to use alternative antifungal agents; the possibility of recurrent infections; and the potential impacts on pregnancy, including preterm labor. Additionally, it has significant public health implications, like the potentially increased rate of nosocomial infections, the risk of spread in the community, the need for public health surveillance and strengthening of infection control practices [33].

The overall magnitude of vertical transmission of Candida species was 44.9% (22/49, 95% CI: 41.2, 49.7). This finding implies that for every ten neonates, at least four neonates can develop vertically transmitted Candida infection. Therefore, efforts must be made to enhance the surveillance system and strengthen infection control practices. These activities are critical to mitigating the impacts of vertical transmission of Candida and ensuring effective intervention strategies in clinical areas. Moreover, this finding highlights the need for a coordinated multi-sectoral collaboration to improve maternal and child health, as well as the need to establish and improve diagnostic facilities and microbiology laboratories.

Furthermore, there was a strong positive association between maternal vaginal colonization and overall vertical transmission of Candida species (r = 0.64, P < 0.001). This finding provides significant insight into the dynamics of Candida transmission, suggesting maternal vaginal colonization significantly increases the risk of neonates acquiring Candida species. Thus, maternal vaginal colonization is a strong predictor of vertical transmission. Therefore, neonatal health and the risk of vertical transmission can be mitigated through appropriate management and monitoring of maternal vaginal colonization, requiring tailored interventions to prevent neonatal Candida infection.

Recognizing the risk factors for vaginal colonization in pregnant women and vertical transmission to newborns is crucial for lowering the morbidity and mortality associated with vaginal candidiasis. In the current study, most of the women who tested positive for Candida were HIV-positive. This finding was supported by studies conducted in Nigeria [34, 35], Brazil [36], and Tanzania [37]. Despite the complex interaction between HIV status and the vaginal colonization of Candida, HIV status is an independent factor affecting the Candida colonization rate among pregnant women. This could be due to the fact that immunosuppression increases a woman’s vulnerability to Candida overgrowth and fungal infection, and is strongly correlated [35] with reduced cell-mediated immunity [38, 39]. Thus, HIV infection is the major factor contributing to the development of vaginal candidiasis; the pathogenesis is controlled by proteinase activity, which increases in women living with HIV, making her more vulnerable than HIV-negative women [39]. Furthermore, a pregnant woman’s immune system is likely to be weakened by the stress of pregnancy combined with HIV infection, making them more susceptible to Candida infections. While vaginal candidiasis has been linked to a common pregnancy infection [40], it is more frequent in pregnant women living with HIV.

The association between diabetes mellitus and vaginal colonization of Candida observed in the present study was supported by existing evidence [41]. This could be due to several underlying mechanisms. Hyperglycemia in the mucus membrane favors the rapid growth of yeast and leads to structural and functional changes in the vaginal epithelium that promote vaginal colonization [42]. The likelihood of Candida colonization can be enhanced through glucosuria, which provides nutrients and exacerbates the virulence of Candida [43]. The hormonal changes such as higher progesterone and estrogen levels during pregnancy, increase vulnerability to vulvovaginal candidiasis [44]. Additionally, high glucose levels can impair neutrophil function, leaving the Candida unphagocytosed. Likewise, the synthesis of antimicrobial peptides decreases, exacerbating susceptibility [45]. Furthermore, alteration of the vaginal microbiome in women with diabetes leads to a decrease in beneficial pathogens such as lactobacilli with an increase in pathogenic organisms as a result of the impairment of the host’s first line of defense against invading pathogens [46, 47].

In the current study, the likelihood of vertical transmission of Candida species was nearly 2.4 times (AOR = 2.39, 95% CI: 1.97–5.89, P = 0.048) higher in neonates born to mothers older than 28 years compared to younger counterparts (i.e., less than 28 years old). This could be explained by a decrease in lactobacilli due to an age-related decline in estrogen, leading to the dominance of pathogenic flora, including Candida [48], which can be transmitted to their newborn. Additionally, vaginal pH increases with age and leads to the loss of natural epithelial defenses. Age-related attenuation of the immune response and a reduced natural immune defense exacerbate vaginal colonization, subsequently increasing the risk of vertical transmission [49–51]. Likewise, the odds of vertical transmission were 3.6 times (AOR = 3.6, 95% CI: 1.37–9.5, P = 0.010) higher in neonates born to rural dwelling mothers than those born to urban dwelling mothers. This could be due to limited healthcare access, awareness and education, limited hygiene practices and the presence of underlying medical conditions. Thus, this finding enhances the need for community-based interventions with culturally tailored approaches through participatory early diagnosis to improve the health of rural populations. Empowering women and promoting family health or family medicine will be crucial targets for improving universal health coverage in rural areas.

The findings of this study imply a potential threat to maternal and neonatal health, highlighting the need for effective screening and management strategies. The generalizability of the present research findings was ensured by utilization of appropriate statistical analysis, rigorous methodology and a larger sample size of paired samples taken from pregnant women and their newborns. However, this study has certain limitations. Since the focus of the study was on maternal vaginal colonization and vertical transmission of Candida, the health impacts or outcomes of neonates born from the study participants were not assessed. This might limit the comprehensive understanding of the potential complications of Candida colonization during pregnancy. Additionally, anti-fungal susceptibility was not performed due to a lack of resources, where the potential treatment options for Candida infections were not identified.

Conclusion

The vaginal colonization and vertical transmission of Candida species is a concerning maternal and neonatal health problem. Only two opportunistic yeasts, C. albicans and C. krusei, were detected, with a predominancy of C. albicans. Vaginal colonization of Candida species was significantly higher among women with gestational diabetes mellitus and HIV, whereas the magnitude of vertical transmission of Candida species was significantly higher among rural dwellers and mothers older than 28 years. The findings highlight the need for effective screening and treatment of Candida colonization during antenatal care to reduce the risk of pregnancy-related maternal and neonatal complications.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants, data collectors, Amhara Public Health Institute Dessie Branch staffs, and Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital and Dessie Health center staffs for their support and unreserved cooperation in making this study to be a fruitful work.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal Care

- APGAR

Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration

- DCSH

Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- DHC

Dessie Health Center

- HIV

Human Immune Deficiency Virus

- PROM

Premature rupture of membrane

- STI

Sexually Transmitted Infection

- UTI

Urinary Tract Infection

- VVC

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Author contributions

Alemu Gedefie, Getnet Shimeles, Chalachew Genet, Hilina Motbainor and conceived and designed the study, prepared the proposal, supervised data collection, analyzed, and interpreted the data. Alemu Gedefie, Getnet Shimeles, and Brhanu Kassanew had participated in data collection, analysis and interpretation of the result. Alemu Gedefie drafted and prepared the manuscript for publication. Getnet Shimeles, Chalachew Genet, Hilina Motbainor, and Brhanu Kassanew critically reviewed the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was materially supported by Bahir Dar University, Wollo University and Amhara Public Health Institute, Dessie Branch.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review Board of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University (Protocol number 749/2023). Permission for the study was granted in a letter from DCSH and DHC, where the study was conducted. After briefly describing the significance of the study, written informed consent from the pregnant mother and assent for the newborns were obtained. Confidentiality of the data was maintained. Finally, based on a microbiologically confirmed positive result, the clinician responsible for the participant was informed and the participant was treated with an appropriate treatment protocol. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Williams DW, Kuriyama T, Silva S, Malic S, Lewis MA. Candida biofilms and oral candidosis: treatment and prevention. Periodontol 2000. 2011;55(1). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Makanjuola O, Bongomin F, Fayemiwo SA. An update on the roles of non-albicans Candida species in vulvovaginitis. J Fungi. 2018;4(4):121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godoy-Vitorino F, Romaguera J, Zhao C, Vargas-Robles D, Ortiz-Morales G, Vázquez-Sánchez F, et al. Cervicovaginal fungi and bacteria associated with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and high-risk human papillomavirus infections in a hispanic population. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulik C, Sobel J, Nailor M. Susceptibility profile of vaginal isolates of Candida albicans prior to and following fluconazole introduction–impact of two decades. Mycoses. 2011;54(1):34–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zisova LG, Chokoeva AA, Amaliev GI, Petleshkova PV, Miteva-Katrandzhieva T, Krasteva MB, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis in pregnant women and its importance for candida colonization of newborns. Folia Medica. 2016;58(2):108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maki Y, Fujisaki M, Sato Y, Sameshima H. Candida Chorioamnionitis leads to preterm birth and adverse fetal-neonatal outcome. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2017;2017(1):9060138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mother Safe Royal Hospital for Women. Thrush and Pregnancy. NSW Health 2021 [Available from: https://www.seslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/groups/Royal_Hospital_for_Women/Mothersafe/documents/thrushpreg2021 (accessed on 03 August 2024).

- 8.Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, Hviid A, Pasternak B. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315(1):58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meizoso T, Rivera T, Fernández-Aceñero M, Mestre M, Garrido M, Garaulet C. Intrauterine candidiasis: report of four cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:173–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts CL, Rickard K, Kotsiou G, Morris JM. Treatment of asymptomatic vaginal candidiasis in pregnancy to prevent preterm birth: an open-label pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Cássia Orlandi Sardi J, Silva DR, Anibal PC, de Campos Baldin JJCM, Ramalho SR, Rosalen PL, et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiology and risk factors, pathogenesis, resistance, and new therapeutic options. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2021;15:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denning DW, Kneale M, Sobel JD, Rautemaa-Richardson R. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(11):e339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalia N, Singh J, Kaur M. Microbiota in vaginal health and pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal infections: a critical review. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguin TJ, Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidiasis in pregnancy. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015;17:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsega A, Mekonnen F. Prevalence, risk factors and antifungal susceptibility pattern of Candida species among pregnant women at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levina J, Ocviyanti D, Adawiyah R. Management of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in pregnancy. Indonesian J Obstet Gynecol. 2024:115–21.

- 17.San Juan Galán J, Poliquin V, Gerstein AC. Insights and advances in recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. PLoS Pathog. 2023;19(11):e1011684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease:revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and …. [PubMed]

- 19.Filkins L, Hauser JR, Robinson-Dunn B, Tibbetts R, Boyanton BL, Revell P. American Society for Microbiology provides 2020 guidelines for detection and identification of group B Streptococcus. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;59(1):01230–20. 10.1128/jcm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babić M, Hukić M. Candida albicans and non-albicans species as etiological agent of vaginitis in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Bosnian J Basic Med Sci. 2010;10(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinicalsci. Germ tube test accessed June 29. 2029 [Available from: https://clinicalsci.info/germ-tubetest/

- 22.Monica C. Microbiological tests: district laboratory practice in tropical countries. Chapter. 2006;2:670. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rad ZA, Esmaeilzadeh S, Mojaveri MH, Bagherzadeh M, Javanian M. Maternal recto-vaginal organisms and surface skin colonization in infants. Iran J Neonatology. 2018;9(3).

- 24.Sukali G. Characterization of Candida isolates from South African pregnant and non-pregnant women 2023.

- 25.Hynniewta BC, Chyne WW, Phanjom P, Donn R. Prevalence of Vaginal Candidiasis among pregnant women attending Ganesh Das Government Maternity and Child Health hospital, Shillong, Meghalaya, India. Shillong, Meghalaya, India. 2019.

- 26.Okonkwo N, Umeanaeto P. Prevalence of vaginal candidiasis among pregnant women in Nnewi Town of Anambra State, Nigeria. Afr Res Rev. 2010;4(4).

- 27.Nelson M, Wanjiru W, Margaret MW. Prevalence of vaginal candidiasis and determination of the occurrence of Candida species in pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic of Thika District Hospital, Kenya. Open Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2013;2013.

- 28.Mulinganya MGDKK, Mongane IJ, Kampara MFDVA, Boelens J, Duyvejonck HHE, Kujirakwinja BY, Bisimwa BGRA, Vaneechoutte M, Callens S, Cools P. Second trimester vaginal Candida colonization among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Bukavu, Democratic Republic of the Congo: prevalence, clinical correlates, risk factors and pregnancy outcomes. Front Glob Womens Health 2024;5(1339821). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Altayyar IA, Alsanosi AS, Osman NA. Prevalence of vaginal candidiasis among pregnant women attending different gynecological clinic at South Libya. Eur J Experimental Biology. 2016;6(3):25–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanagal D, Vineeth V, Kundapur R, Shetty H, Rajesh A. Prevalence of vaginal candidiasis in pregnancy among coastal south Indian women. J Womens Health Issues Care. 2014;3(6):2. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Hatami SMM, Al-Moyed KAA, Al-Shamahy HA, Al-Haddad AM, Al-Ankoshy AAM. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: prevalence, species distribution and risk factors among non-pregnant women, in Sana’a, Yemen. Universal Journal of Pharmaceutical Research; 2021.

- 32.Kombade SP, Abhishek KS, Mittal P, Sharma C, Singh P, Nag VL. Antifungal profile of vulvovaginal candidiasis in sexually active females from a tertiary care hospital of Western Rajasthan. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(1):398–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seyoum E, Bitew A, Mihret A. Distribution of Candida albicans and non-albicans Candida species isolated in different clinical samples and their in vitro antifungal suscetibity profile in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sagay AS, Kapiga SH, Imade GE, Sankale J, Idoko J, Kanki P. HIV infection among pregnant women in Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2005;90(1):61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Umeh E, Umeakanne B. HIV/vaginal candida coinfection: risk factors in women. J Microbiol Antimicrobials. 2010;2(3):30–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliveira PM, Mascarenhas RE, Lacroix C, Ferrer SR, Oliveira RPC, Cravo EA, et al. Candida species isolated from the vaginal mucosa of HIV-infected women in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Brazilian J Infect Dis. 2011;15:239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Namkinga L, Matee M, Kivaisi A, Moshiro C. Prevalence and risk factors for vaginal candidiasis among women seeking primary care for genital infections in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. East Afr Med J. 2005;82(3). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Mtibaa L, Fakhfakh N, Kallel A, Belhadj S, Belhaj Salah N, Bada N, et al. Les candidoses vulvovaginales: etiologies, symptomes et facteurs de risque. J De Mycol Medicale. 2017;27(2):153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foessleitner P, Petricevic L, Boerger I, Steiner I, Kiss H, Rieger A, et al. HIV infection as a risk factor for vaginal dysbiosis, bacterial vaginosis, and candidosis in pregnancy: a matched case-control study. Birth. 2021;48(1):139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheesbrough M. District laboratory practice in tropical countries, part 2. Cambridge University Press; 2006.

- 41.Rodrigues CF, Rodrigues ME, Henriques M. Candida sp. infections in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Clin Med. 2019;8(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Catalano PM, Hauguel-De Mouzon S. Is it time to revisit the Pedersen hypothesis in the face of the obesity epidemic? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):479–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Liao Q, Wang F, Li D. Association of gestational diabetes mellitus and abnormal vaginal flora with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Medicine. 2018;97(34):e11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boselli F, Chiossi G, Garutti P, Matteelli A, Montagna MT, Spinillo A. Preliminary results of the Italian epidemiological study on vulvo-vaginitis. Minerva Ginecol. 2004;56(2):149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atabek ME, Akyürek N, Eklioglu BS. Frequency of vagınal candida colonization and relationship between metabolic parameters in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26(5):257–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amabebe E, Anumba DO. The vaginal microenvironment: the physiologic role of lactobacilli. Front Med. 2018;5:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valenti P, Rosa L, Capobianco D, Lepanto MS, Schiavi E, Cutone A, et al. Role of lactobacilli and lactoferrin in the mucosal cervicovaginal defense. Front Immunol. 2018;9:376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshikata R, Yamaguchi M, Mase Y, Tatsuzuki A, Myint KZY, Ohta H. Age-related changes, influencing factors, and crosstalk between vaginal and gut microbiota: a cross-sectional comparative study of pre-and postmenopausal women. J Women’s Health. 2022;31(12):1763–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gameiro CM, Romão F, Castelo-Branco C. Menopause and aging: changes in the immune system—a review. Maturitas. 2010;67(4):316–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.García-Closas M, Herrero R, Bratti C, Hildesheim A, Sherman ME, Morera LA, et al. Epidemiologic determinants of vaginal pH. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(5):1060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisberg E, Ayton R, Darling G, Farrell E, Murkies A, O’Neill S, et al. Endometrial and vaginal effects of low-dose estradiol delivered by vaginal ring or vaginal tablet. Climacteric. 2005;8(1):83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.