Abstract

Specific gene silencing has been demonstrated in a number of organisms by the introduction of antisense RNA. Mutagenesis of host-encoded factors has begun to unravel the mechanism of several forms of RNA-mediated gene silencing and has suggested that it may have been conserved through evolution. This has led to the identification of certain host genes, which, when mutated, abrogate this phenomenon. Conversely, the identification of other factors that, when co-expressed or overexpressed, can enhance gene inhibition is equally important for both elucidating the mechanism of this process and enhancing gene silencing in recalcitrant systems. We have taken such a dominant genetic approach to identify several host-encoded factors that dramatically enhance target gene silencing when co-expressed with antisense RNA in fission yeast. The transcription factor thi1 and, surprisingly, the ATP-dependent RNA helicase ded1 were initially shown to enhance gene silencing in this system. Additionally, screening of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe cDNA library identified four novel antisense-enhancing sequences (aes factors) all of which are homologous to genes encoding proteins with natural affinities for nucleic acids. These findings demonstrate the utility of this strategy in identifying host-encoded factors that can modulate gene silencing when co-expressed with antisense RNA and possibly other forms of gene-silencing activators.

INTRODUCTION

Gene silencing has been demonstrated in a number of organisms by the intracellular expression of antisense RNA (1). The application of this strategy often results in only partial suppression, depending upon the gene being targeted or the organism in which it is employed (2). This is also true for other forms of post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) such as double-stranded (ds)RNA-mediated gene silencing and RNA interference (RNAi) (3). The reasons for this variability of RNA-mediated gene silencing may include (i) the secondary structure of the complementary RNAs and target site accessibility, (ii) the stability of the antisense RNA molecule, (iii) the ratio of antisense and target RNA, (iv) the metabolic state of the cell, (v) the co-localisation of the complementary RNAs within the cell and (vi) the presence or absence of host factors that are part of the gene-silencing pathway(s) (4,5).

RNA structure, annealing dynamics and stability are dependent on RNA-binding proteins (2,6). Additionally, there are many proteins that bind to duplexed RNA which may affect antisense RNA-mediated gene inhibition, including ADAR, PKR, RNA helicases and RNase III (7). Several cellular proteins have been identified as facilitators of RNA duplex formation (8). These include the ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) (9–11), the tumor suppressor protein p53 (12,13) and the yeast initiation factor TifIII (14). These RNA-binding proteins may act to facilitate RNA hybridisation through various mechanisms. For example, the heterogenous nuclear ribonuceloprotein hnRNP A1 has been shown to strongly enhance RNA:RNA duplex formation through protein–protein interactions (9,11) and has thus been a candidate for modulating antisense RNA efficacy. It is reasonable to expect that alternative proteins would exist in fission yeast that act in a similar fashion to hnRNPs.

RNA helicases have roles in transcription, pre-mRNA splicing, RNA maturation, RNA transport and translation and RNA degradation (15). It is likely that unwinding of RNA duplexes also affects gene silencing. This could result in inhibition of the antisense effect by resolving dsRNA or it is conceivable that such helicases could enhance gene silencing if an RNAi-like mechanism was active where dsRNA was the catalytic molecule (16). Recently, the RNA helicases SDE3 (17), DICER (18) and MUT6 (19) have been shown to be central to dsRNA-mediated gene silencing in Arabidopsis thaliana, Drosophila melanogaster and the alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, respectively.

Mutagenesis of host-encoded factors has begun to unravel the mechanism of PTGS and has suggested that it may have been conserved through evolution (20). This has led to the identification of certain non-essential factors that, when down-regulated, affect the efficiency of gene silencing. In addition to RNA helicases, these genes include ones encoding an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [qde-1 (21), sde1 (22) and ego-1 (23)], a RecQ DNA helicase [qde-3 (24)], an RNase D homologue [mut-7 (25)], an RNase III homologue (18) and a putative translation initiation factor [rde-1 (26), qde-2 (27) and ago1 (28)]. Clearly, there may be several additional factors, in particular genes that are essential for cell viability, which are involved in gene silencing that, as yet, have not been identified.

In comparison with mutagenesis strategies, the identification of other factors that, when overexpressed, can enhance gene silencing is equally important for both elucidating the mechanism of these processes and enhancing gene silencing in recalcitrant systems. Here we present a genetic screening approach to identify several host-encoded factors that dramatically enhance target gene silencing when co-expressed with antisense RNA in fission yeast. These factors were named antisense-enhancing sequences (to be referred to as aes factors). We discuss the utility of this genetic strategy for identifying cofactors capable of modulating the efficacy of RNA-mediated gene regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Schizosaccharomyces pombe media and manipulations

All yeast manipulations were performed as previously described (5). Yeast strains were maintained on standard YES or EMM medium (29) and transformed with plasmid DNA by electroporation (30). Repression of nmt1 transcription was achieved by the addition of thiamine to EMM medium at a final concentration of 4 µM.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe strain and plasmid construction

The construction of the target strain RB3-2 has been previously described (31). The long lacZ antisense (pGT2), short 5′ antisense (pGT59) and short 3′ antisense (pGT61) containing episomal plasmids have also been described elsewhere (32). Plasmid pREP4-lacZAs was generated by subcloning the lacZ BamHI fragment contained in pGT2 into the plasmid pREP4 (33). pREP4 is identical to pREP1 except that the Saccharomyces cerevisiae LEU2 gene has been replaced with the Schizosaccharomyces pombe ura4 selectable marker. The lacZ vector encoding sense lacZ incapable of producing functional β-galactosidase was generated by end-filling the ClaI site of pGT2 and re-ligating (pGT62) (32). This fragment was subcloned into the BamHI site of pREP4 to generate the plasmid pM54-3.

The thi1 open reading frame (ORF) (accession no. 6523770) was initially PCR amplified from genomic DNA (strain 1913; NCYC) using the 5′ primer 5′-ATG AGA TCT GTG GTT GGT ATT CTA GAG AGA-3′ and the 3′ primer 5′-ATG AGA TCT AAC AAA GAC CTG CAA AAA ACC-3′ to generate an amplicon with BglII ends. The ded1 ORF (accession no. AJ237697) was amplified from the same genomic DNA to give it BamHI ends using the forward primer 5′-Atg gga tcc caa cca aac act tca act cag-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-Atg gga tcc tca gaa gcc tgt gca taa cac-3′. The PCR products for thi1 and ded1 were each subcloned into the BamHI site of pREP4 in the sense orientation to produce pREP4-thi1 and pREP4-ded1, respectively. The ded1 ORF was also subcloned into the BamHI site of the pREP2 vector in the sense orientation to generate pREP2-ded1.

Northern analysis

Nucleic acid electrophoresis and membrane transfer was performed as described (34). Northern blots were hybridised using ExpressHyb solution according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech Laboratories). DNA probes were 32P labelled using the Megaprime labelling kit (Amersham). A 2.2 kb PstI/SacI nmt1 fragment was used as a probe and radioactive signals were detected by autoradiography and quantitated by phosphorimager analysis (ImageQuant; Molecular Dynamics).

Isolation of S.pombe cDNA clones that modulate the efficacy of antisense RNA

The S.pombe cDNA library was originally constructed in pREP3Xho by Bruce Edgar and Chris Norbury (35). The vector pREP3Xho is derived from pREP3, which contains the LEU2 marker and inserts are under control of the conditional nmt1 promoter (33). A total of 5 µg library DNA was transformed into the strain RB3-2 containing the episomal antisense lacZ vector pREP4-lacZAS and grown in EMM liquid medium to mid-logarithmic phase. Transformants were then plated on EMM solid medium and grown at 30°C for 3 days. Colonies were overlayed with medium containing 0.5 M sodium phosphate, 0.5% agarose, 2% dimethylformamide, 0.01% SDS and 500 µg/ml X-gal (Progen, Australia) (31). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 h and colonies of interest recovered and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. To remove antisense plasmids from co-transformants, strains were plated on EMM containing limiting uracil and 1 mg/ml 5-fluoroorotic acid (29). Strains were then replica-plated on both selective and non-selective media. Those colonies that did not grow on selective medium were identified as having lost the ura4-containing antisense plasmid.

β-Galactosidase assays

Expression of the lacZ gene-encoded product, β-galactosidase, was quantitated using a cell permeabilisation protocol as previously described (5). A semi-quantitative overlay assay was employed for rapid screening of yeast transformants (31).

Plasmid segregation

Raw data were normalised to account for plasmid segregation following cell division (36). Strains were plated on both selective and non-selective media. The number of colonies grown on non-selective medium (YES) was taken as the total number of viable cells in the cell population. Cells in the population harbouring either ura4- or LEU2-containing plasmids were identified by plating onto EMM + leucine and EMM + uracil, respectively. The ratio of the number of colonies grown on selective medium to the total number of viable colonies was used as a quantitative measure of the proportion of plasmid-containing cells. It was found that ∼73% of the cell population contained LEU2-based plasmids, while ∼69% of the cell population contained both ura4- and LEU2-based plasmids.

RESULTS

Overexpression of a host-encoded factor enhances antisense RNA efficacy

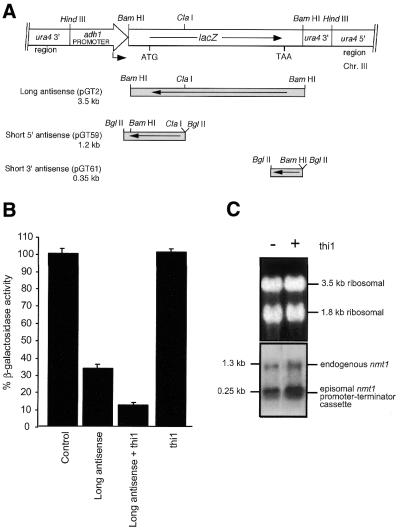

We have recently established a fission yeast model for examining antisense RNA-mediated regulation of the lacZ reporter gene (5,31,32). We use the fission yeast strain RB3-2 containing the chromosomally expressed target lacZ gene under control of the constitutive adh1 promoter and antisense lacZ genes under control of the conditionally regulated nmt1 promoter (Fig. 1A). In this system, we showed that antisense RNA-mediated gene silencing is dose dependent (5). To demonstrate that a dominant genetic approach could be used to identify factors that enhance gene silencing by antisense RNA, we initially overexpressed the thi1 gene in this model. This transcriptional activator has previously been shown to up-regulate transcription of the thiamine-repressible promoter nmt1 (37) and, as such, we hypothesised that activation of the nmt1-driven antisense gene would enhance lacZ inhibition. The plasmid pREP4-thi1 was transformed into strain RB3-2 containing the antisense lacZ plasmid pGT2 and β-galactosidase assays were performed. Raw data were then normalised to account for plasmid segregation. As predicted, lacZ suppression in the thi1-expressing strain was enhanced when compared with a strain expressing antisense RNA alone (Fig. 1B). When pREP4-thi1 was introduced into RB3-2 in the absence of the antisense plasmid, no down-regulation of β-galactosidase activity was observed. As expected, northern analysis demonstrated that overexpression of thi1 resulted in an increased level of steady-state nmt1 RNA (Fig. 1C). This was shown for both the endogenous nmt1 gene and the episomal nmt1 promoter which is contained in the control vector. These results indicate that the transcriptional activator, thi1, could increase the intracellular dose of the antisense RNA that, in turn, enhances gene silencing. Furthermore, it suggests that additional rate-limiting host-encoded factors are present which may affect the robustness of RNA-mediated gene silencing.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of the transcriptional activator thi1. (A) The long (pGT2), short 5′ (pGT59) and short 3′ (pGT61) lacZ antisense constructs are shown in relation to the target lacZ cassette. The adh1-driven target lacZ gene is integrated at the ura4 locus on chromosome III of the fission yeast strain RB3-2. (B) thi1 was co-expressed with the long lacZ antisense gene in the strain RB3-2 (long antisense + thi1) and co-transformants were assayed for β-galactosidase activity. RB3-2 expressing the antisense lacZ (long antisense) or thi1 (thi1) genes only were also analysed. The control strain was RB3-2 transformed with pREP2 and pREP4 (control). Three independent colonies were assayed in triplicate for each strain. (C) Northern blot analysis of RB3-2 containing the pREP2 and pREP4 (–) or pREP2 and pREP4-thi1 (+) plasmids. RNA was probed with the nmt1 promoter fragment to detect all transcripts driven by the nmt1 promoter including the endogenously expressed nmt1 gene (1.3 kb) and the episomally expressed nmt1 promoter and terminator cassette (0.25 kb). This latter cassette is transcribed from the control vectors pREP2 and pREP4. The ethidium bromide-stained gel showing the rRNA bands indicates equal RNA loading.

Co-expression of the ded1 helicase enhances antisense RNA-mediated gene silencing

Since RNA duplex formation can directly inhibit translation, RNA helicases were originally proposed to decrease antisense RNA-mediated gene inhibition as overexpression of an RNA helicase would enhance unwinding of the RNA duplex. However, recent evidence has shown that RNA helicases are required for other forms of RNA-mediated gene silencing, such as PTGS and RNAi (17–19). We therefore tested the ability of the S.pombe ATP-dependent RNA helicase gene, ded1 (38), in modulating antisense RNA efficacy by co-expressing it with various antisense genes in fission yeast (Fig. 1A). This particular RNA helicase was chosen because (i) it has been shown to be involved in translation initiation in S.pombe (38) and might therefore be a candidate for unwinding a mRNA-containing duplex, and (ii) ded1 is an essential gene and therefore an ideal candidate RNA helicase to test by the dominant genetic approach.

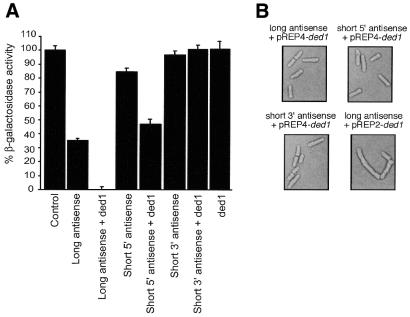

Surprisingly, co-expression of ded1 from the pREP4 plasmid and the long antisense lacZ (pGT2) from the pREP2 plasmid demonstrated complete inhibition of β-galactosidase activity following normalisation for plasmid segregation (Fig. 2A). When ded1 was overexpressed in the absence of the antisense lacZ vector, β-galactosidase activity was comparable with control strains, indicating that the ded1 effect was dependent on the presence of antisense RNA. The ded1 vector was also co-expressed with a short 5′ antisense lacZ plasmid (pGT59) which was previously shown to be less effective than the full-length antisense gene (32). Again, overexpression of ded1 stimulated antisense RNA-mediated lacZ inhibition. However, when the ded1 gene was co-expressed with a short 3′ antisense lacZ plasmid (pGT61), which demonstrates negligible suppression (32), no enhancement of gene silencing was observed. When ded1 was expressed from a ura4-based plasmid (pREP4) there was no impact on the phenotype of the transformed strain (Fig. 2B). However, in agreement with previous observations (39), ded1 expression from the weakly complementing LEU2-based plasmid (pREP2) caused aberrant morphology of transformed cells (Fig. 2B). This is most likely due to differences in copy number of ura4- and LEU2-based plasmids (36,40). As LEU2-based plasmids are usually maintained at a higher copy number than ura4-based plasmids there would be a consequent increase in the steady-state level of ded1, which would produce a threshold of the protein that impacts on the cell cycle. In addition, we have observed an increased steady-state level of gene expression from LEU2-based plasmids compared with ura4-based plasmids (data not shown). The above observations confirmed that the ded1 ORF was generating functional ded1 protein. In conclusion, these data indicate that the host-encoded ATP-dependent RNA helicase, ded1, can enhance antisense RNA efficacy when co-expressed with effective antisense RNA molecules.

Figure 2.

Co-expression of antisense lacZ genes and ded1. (A) β-Galactosidase assay of antisense lacZ and ded1 co-transformants. The pREP4-ded1 plasmid was co-expressed with the pREP2 plasmid containing different antisense lacZ constructs. Three colonies were assayed in triplicate for each strain. Strains were co-transformed with the appropriate control plasmid to complement auxotrophy. (B) Light microscopic analysis of ded1 transformants. The strain RB3-2 was co-transformed with the plasmids indicated and grown to mid-logarithmic phase before examination.

Library screen for antisense-enhancing plasmids

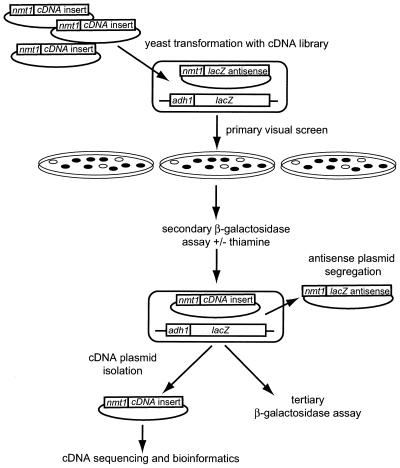

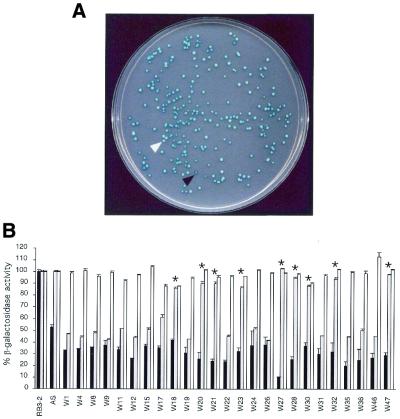

Next, a S.pombe cDNA library was overexpressed in the antisense lacZ-expressing fission yeast strain to screen for novel host-encoded factors that would enhance gene silencing in the current system (Fig. 3). A S.pombe cDNA library was transformed into RB3-2 containing the episome-based long lacZ antisense plasmid (pGT2). The cDNA transformants are under control of the nmt1 promoter and have the ability to be translated. From 12 000 transformants screened, 48 were initially identified as having a reduced blue phenotype compared with background transformants (Fig. 4A). Each of these transformants was independently isolated from the primary screen. Transformants also displaying an increased blue phenotype were identified, but these were not analysed further. Clearly, this system can also be employed to screen for host-encoded factors that, when overexpressed, inhibit antisense RNA efficacy. Quantitative analysis using the liquid β-galactosidase assay showed that 25 of the 48 transformants displayed a reproducible reduction in β-galactosidase activity compared with the antisense strain alone (Fig. 4B). The control strain, RB3-2, transformed with the lacZ antisense construct, consistently demonstrated ∼55% of control β-galactosidase activity (prior to normalisation for plasmid segregation). The antisense lacZ gene and the host factor cDNA were both driven by the conditional nmt1 promoter. Repression of the nmt1 promoter by addition of thiamine to the culture medium resulted in a reversion to control levels of β-galactosidase activity. This indicated that the observed enhancement of suppression in these transformants was dependent on expression of the antisense RNA and/or the host factor cDNA and that this effect was not due to other events such as lacZ target gene mutations or modification of protein stability.

Figure 3.

Overexpression screening strategy for antisense RNA-modulating factors. A target strain containing the integrated lacZ gene under control of the adh1 promoter and the episomal vector containing the nmt1-driven lacZ antisense gene was transformed with a S.pombe cDNA library. Library fragments were driven by the nmt1 promoter. Transformants were individually screened for a change in the lacZ-encoded blue-colour colony phenotype and then transformants of interest were further characterised by quantitative β-galactosidase assay and sequence analysis of antisense enhancing sequences.

Figure 4.

Co-expression screen using a S.pombe cDNA library. (A) Transformants were grown on minimal medium plates and overlaid with X-gal-containing medium. Those that showed a reduced blue-colour phenotype (white arrow) were analysed further. Transformants demonstrating an enhanced blue-colour phenotype were also identified (black arrow). (B) Transformants that showed a visual reduction in the blue phenotype were assayed for β-galactosidase activity in liquid culture in the absence of thiamine (black histograms). Thiamine was added to the medium to repress expression of the antisense and cDNA cassettes (white histograms). Transformants were again assayed for β-galactosidase activity following antisense vector segregation (grey histograms). Asterisks indicate transformants showing an antisense-dependent enhancement of gene silencing. One colony was assayed in triplicate for each transformant.

Following segregation of the antisense lacZ plasmid from these strains, 9 of the 25 transformants returned to the level of β-galactosidase activity observed in the control strain (Fig. 4B). Together with the above data, this indicates that the enhanced gene silencing observed in these nine strains was dependent on expression of antisense lacZ RNA. The cDNAs expressed in these transformants were therefore named antisense-enhancing sequences (aes factors). The remaining 16 transformants retained a suppressed level of β-galactosidase activity, indicating that the reduced blue phenotype of these transformants was not dependent on the presence of lacZ antisense RNA and that the cDNA encoded proteins in these strains were modulating lacZ gene expression by an alternative mechanism. It is possible that these factors are affecting the rate of lacZ transcription or the stability of the β-galactosidase protein. Although these were not further characterised it will be of interest to determine their nature and mode of action on lacZ gene expression.

Characterisation of antisense-enhancing sequences

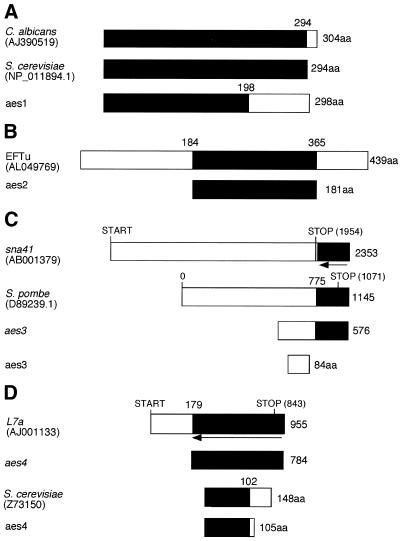

The library plasmids were recovered from the aes-containing strains and their cDNA inserts sequenced using primers specific for the nmt1 expression cassette (5; see Supplementary Material). BLASTN and BLASTP analyses were performed on the sequenced cDNA inserts using the NCBI GenBank facility. Four unique aes factors were characterised. The extent of homology for each of these is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic alignment of aes factors with known nucleotide and protein sequences. Regions of identity are shaded black. The length of protein sequences is followed by aa (amino acids). (A) Protein alignment of aes1 with C.albicans hypothetical protein and S.cerevisiae TS protein. (B) Region of S.pombe EFTu that aligns with the aes2-encoded protein. (C) Nucleotide sequence of aes3 aligns with the antisense strand of S.pombe sna41 (indicated by an arrow) and the sense strand of a S.pombe hypothetical protein (partial 3′ sequence shown). The putative aes3-encoded protein is indicated. The absence of complete homology to the sna41 sequence indicates that this factor may be a chimera. (D) Nucleotide alignment of aes4 with the antisense strand of S.pombe L7a (arrow). Possible aes4-encoded protein alignment with S.cerevisiae hypothetical protein. Accession numbers are shown in brackets.

BLASTN analysis identified the cDNA in the transformants W18, W20 and W30 (named aes2) as part of the mitochondrial elongation factor EFTu (accession no. AL049769). EFTu is the mitochondrial analogue of the eukaryotic EF1α, which acts in the cytoplasm transporting tRNA to the A site in the ribosome for peptide elongation (41). The aes2 sequence corresponded to 181 amino acids of the central portion of the encoded protein (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the absence of the 5′ end of this protein may allow aes2 to act within the cytoplasm as the mitchondrial signal peptides, which allow for transportation from the cytosol to the mitochondria, are found in the N-terminus of mitochondrial proteins (42).

Approximately 50% of the cDNA sequence in transformants W21, W23 and W32 (named aes3) had complete identity to the 3′ end of a putative protein (accession no. D89239) that was previously identified in a screen for fission yeast ORFs (43). This portion of aes3 also had complete homology to the antisense strand of the 3′-untranslated region of the fission yeast gene sna41 (accession no. AB001379). The protein encoded by sna41 was previously shown to be involved in DNA replication and has low homology (31% identity) with the S.cerevisiae protein CDC45 (44). In addition, analysis of aes3 showed that its 5′ end was comprised of an ORF which could be translated into an 84 amino acid protein containing a string of 36 arginine–glutamic acid repeats. These types of amino acid repeats are often found in transcription factors, which lends further credence that this factor is acting directly on nucleic acids. Finally, it should be noted that the aes3 sequence is possibly a chimera generated by library construction since the 5′ portion of this sequence is not homologous to the 5′ end of the S.pombe sna41 gene.

The cDNA in transformant W47 (named aes4) was completely homologous to the antisense strand of the S.pombe ribosomal protein L7a (accession no. AJ001133), a component of the 60S ribosomal subunit. Interestingly, several antisense transcripts have been identified in ribosomal loci (45,46). Additionally, a genome-wide screen has found complementarity between many mRNAs and rRNAs (47), while more recently it has been shown that such RNA duplex formation may function as a mechanism of translational control (48). aes4 also contained a small ORF (105 amino acids) of unknown biological function. This protein sequence shared 52% identity with a hypothetical protein in S.cerevisiae (accession no. Z73150).

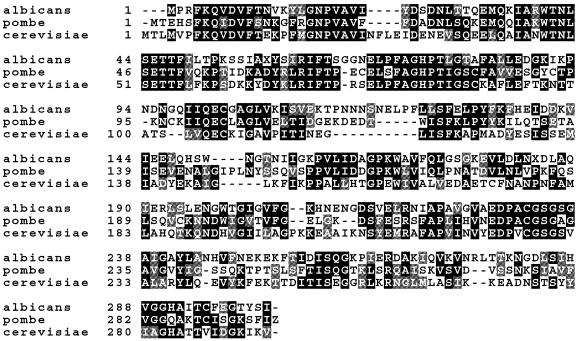

BLASTP analysis showed that the inserts in transformants W27 and W28 (named aes1) shared 43% identity with amino acids 4–202 of a Candida albicans hypothetical protein (accession no. AJ390519) which was identified in a screen for genes essential for cell growth (M. De Backer, personal communication). It also shared weak homology (39% identity) with the S.cerevisiae thymidylate synthase (TS) protein (accession no. NP_011894.1). TS is required for the de novo synthesis of thymidine 5′-monophosphate (dTMP) and also has RNA-binding properties (49). The degree of homology between the S.pombe aes1 protein and the S.cerevisiae and C.albicans proteins is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Sequence alignment of the aes1 protein with related proteins. Sequences displayed are S.pombe (aes1), C.albicans (AJ390519) and S.cerevisiae (NP_011894.1). Identical residues are shown in black and conservative substitutions are indicated in grey. The Clusta1W algorithm was used for the alignment and the PrettyBox program (Wisconsin Package v.10.0; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI) was used for display.

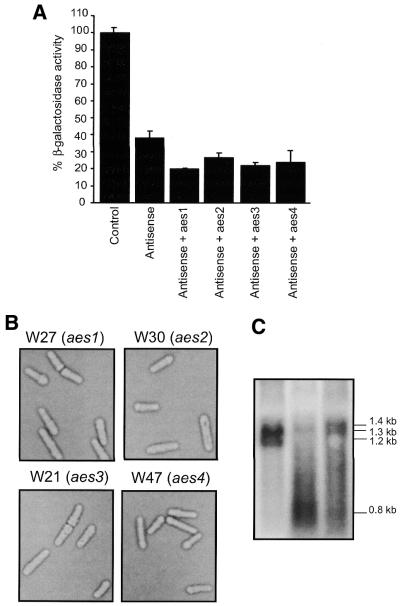

A tertiary β-galactosidase assay showed that these cofactors enhanced antisense suppression by up to 50% when co-expressed with antisense RNA in the lacZ strain (Fig. 7A). In this assay three individual colonies of transformants W27 (aes1), W30 (aes2), W21 (aes3) and W47 (aes4) were assayed in triplicate and normalised for plasmid segregation. All of the aes-expressing strains displayed normal growth rates and cellular morphologies, indicating that overexpression of the exogenous cDNAs did not affect general metabolism (Fig. 7B). Northern analysis also confirmed RNA expression of selected aes factors in these strains, while transcripts of predicted sizes were observed (Fig. 7C). These results demonstrated that overexpression of a cDNA library was an effective way of identifying novel cofactors that magnify the suppressive effect mediated by antisense RNA.

Figure 7.

Expression of aes factors. (A) Co-expression of the unique aes factors with the long antisense lacZ plasmid in RB3-2. Three colonies were assayed in triplicate for each transformant. In this tertiary assay data were normalized to account for plasmid segregation. (B) Microscopic analysis of transformants expressing aes factors. Transformants were examined at mid-logarithmic phase. (C) Northern analysis of aes-containing strains. RNA was fractionated on a 1% MOPS/formaldehyde agarose gel and transferred to a nylon membrane. RNA was then probed with the nmt1 fragment. The endogenous nmt1 fragment fractionates at 1.3 kb. W30 contains aes2 (∼1.2 kb), W21 contains aes3 (∼0.8 kb) and W27 contains aes1 (∼1.4 kb).

DISCUSSION

A common genetic strategy for analysing the cellular function of a gene is to examine phenotypes associated with reduced gene expression levels. Previous studies have used mutagenesis approaches to identify proteins involved in different categories of RNA-mediated gene silencing. For example, a screen of Neurospora mutants that were defective in quelling of an endogenous gene (50) identified several proteins involved in PTGS, including an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (21) and a RecQ DNA helicase (24). A similar screen in Arabidopsis also identified mutants impaired in co-suppression (51), while mutagenesis of C.elegans strains have identified genes that are involved in RNAi (25,26). A common outcome of these approaches was that all of the genes identified were non-essential for cell viability. Clearly, one reason for this is that genes essential for cell growth or proper development will be selected against if their expression is perturbed.

‘Dominant genetics’ is an alternative approach to elucidate gene function based on increasing the intracellular concentration of an endogenous gene’s encoded product and examining the resulting phenotype (52). This may result in either supplementation of the protein or in its inhibition via a transdominant negative effect. Here a unique overexpression strategy was developed for the identification of novel host-encoded factors that enhance antisense RNA-mediated gene silencing in fission yeast. It overcomes the major limitation of the mutagenesis approaches enabling genes that are both essential and non-essential for cell growth to be selected. It must be considered, however, that overexpression of certain genes can also be deleterious to the cell and, as a result, this screening strategy may also fail to identify a subset of host genes involved in gene silencing. It is therefore suggested that this approach should be used to complement mutagenesis strategies.

The first gene that was tested in modulating antisense RNA-mediated gene regulation in the present model was the S.pombe transcription factor thi1. As expected, overexpression of this gene up-regulated nmt1-driven antisense lacZ transcription. Since antisense RNA-mediated gene silencing is dose-dependent in this system (5), co-expression of thi1 with the nmt1-driven antisense lacZ gene resulted in enhanced lacZ gene silencing. This result validated our approach of co-expressing host-encoded genes with antisense RNA for identifying factors that enhance gene silencing. To further validate this system we wished to co-express a gene that might inhibit gene silencing. To this end we chose the ATP-dependent RNA helicase gene ded1 (38). ded1 is an essential gene which has previously been characterised as a suppressor of sterility (39), a suppressor of checkpoint and stress responses (53) and a general translation initiation factor (38). If antisense RNA mediates gene silencing by forming an RNA duplex with mRNA, thereby sterically hindering translation, it might be a reasonable assumption that overexpression of an RNA helicase that is involved in translation initiation would interfere with antisense action, thereby increasing the level of lacZ gene activity.

Surprisingly, co-expression of the ded1 gene from the ura4 plasmid with the long antisense lacZ gene significantly enhanced antisense RNA-mediated lacZ inhibition by a further 50% compared with control strains. When ded1 was co-expressed with an ineffective antisense plasmid no enhancement was observed. These results suggest that ded1-mediated augmentation of gene silencing was dependent on an antisense RNA that was capable of some partial gene inhibition. This could be due to the absence of RNA duplex formation with the ineffective antisense RNA and the consequent lack of a substrate for the RNA helicase. This would be consistent with the role of an RNA helicase in dsRNA-mediated gene silencing. Interestingly, DICER in C.elegans (18), MUT6 from the unicellular green alga C.reinhardtii (19) and SDE3 in Arabidopsis (17), all of which contain RNA helicase motifs, have recently been shown to be involved in dsRNA-mediated gene silencing. It will be interesting to examine whether homologues of these helicases also increase the efficacy of antisense RNA in fission yeast. We further address the possibility that antisense RNA is acting through a dsRNA-mediated gene silencing pathway in another study (M.Raponi and G.M.Arndt, manuscript submitted).

The enhanced gene silencing seen when antisense RNA was co-expressed with thi1 or ded1 established this system for the screening of novel factors that increase antisense RNA efficacy. Arndt et al. (31) previously described an in vivo screening strategy for identifying the most effective antisense constructs against any gene of interest using the lacZ fission yeast model. In that study, conditions were identified that established a link between the blue colour colony phenotype and the degree of lacZ-encoded β-galactosidase activity within fission yeast transformants. In the work presented here similar conditions were utilised to screen the impact of a fission yeast cDNA library on the degree of antisense RNA-mediated lacZ gene silencing. From 12 000 transformants 48 were initially found to have a reduced blue phenotype compared with background colonies. Approximately half of these showed a reproducible phenotype when analysed in a secondary assay. Notably, isolation of transformants that contained the same cDNA sequence verified the power of this screening strategy in that it demonstrated the reproducible nature of the visual screen. Two classes of gene-silencing modulators were observed. The first acted independently of antisense RNA and may function either at the transcriptional level or by modifying the stability of the lacZ encoded protein. The second class only functioned in the presence of antisense RNA and were therefore named antisense-enhancing sequences (aes factors).

Four novel aes factors were identified using this screen (named aes1–aes4); co-expression of these factors enhanced antisense RNA-mediated gene silencing by up to an additional 50%. Sequence analysis suggested that each of the aes factors has the potential to interact with nucleic acids. Although each of these factors has the ability to be translated, further studies will be required to demonstrate whether their proteins are being expressed. Interestingly, evidence exists showing that L7a and EFTu interact during biosynthesis (54). This suggests that aes2 and aes4 may act through a similar mechanism to enhance gene silencing. However, while it can be speculated as to how these factors might be functioning in the gene-silencing phenomenon, further work will be required to understand their precise mechanism of action.

Overall, by using a co-expression strategy in a lacZ fission yeast model, five novel genes that enhance antisense RNA-mediated gene silencing have been identified. The overexpression strategy described herein overcomes some limitations associated with mutagenesis by identifying several genes that are essential for cell viability and with a potential role in gene silencing. In addition, this strategy complements other systems by allowing the isolation of cellular factors that modify the efficacy of RNA-mediated gene inhibition in vivo. Furthermore, the co-expression of these factors with different forms of gene silencing activators, including sense RNA, antisense RNA or dsRNA, could be one way of enhancing the efficacy of these methods. This may be especially important for application of antisense RNA and dsRNA to mammalian cells and tissues or to genes that have been recalcitrant to these forms of regulation.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ian Dawes and David Atkins for helpful discussions on the fission yeast model. We are grateful to Chris Norbury for supplying the S.pombe cDNA library and Wayne Gerlach and Lun Quan Sun for helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray J. and Crockett,N. (1992) Antisense RNA; an overview. In Murray,J. (ed.), Antisense RNA and DNA. Wiley-Liss, New York, NY, pp. 1–49.

- 2.Sczakiel G. (1997) The design of antisense RNA. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev., 7, 439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fire A., Xu,S., Montgomery,M., Kostas,S., Driver,S. and Mello,C. (1998) Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans.Nature, 391, 806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denhardt D. (1992) Mechanism of action of antisense RNA. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., 662, 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raponi M., Atkins,D., Dawes,I. and Arndt,G. (2000) The influence of antisense gene location on target gene regulation in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe.Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev., 10, 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pontius B. (1993) Close encounters: why unstructured, polymeric domains can increase rates of specific macromolecular association. Trends Biochem. Sci., 18, 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fierro-Monti I. and Mathews,M. (2000) Proteins binding to duplexed RNA: one motif, multiple functions. Trends Biochem. Sci., 25, 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertrand E. and Rossi,J. (1994) Facilitation of hammerhead ribozyme catalysis by the nucleocapsid protein of HIV-1 and the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1. EMBO J., 13, 2904–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pontius B. and Berg,P. (1990) Renaturation of complementary DNA strands mediated by purified mammalian heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 protein: implications for a mechanism for rapid molecular assembly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 8403–8407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munroe S. and Dong,X. (1992) Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 catalyzes RNA.RNA annealing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 895–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portman D. and Dreyfuss,G. (1994) RNA annealing activities in HeLa nuclei. EMBO J., 13, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu L., Bayle,J., Elenbaas,B., Pavletich,N. and Levine,A. (1995) Alternatively spliced forms in the carboxy-terminal domain of the p53 protein regulate its ability to promote annealing of complementary single strands of nucleic acids. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nedbal W., Frey,M., Willemann,B., Zentgraf,H. and Sczakiel,G. (1997) Mechanistic insights into p53-promoted RNA–RNA annealing. J. Mol. Biol., 266, 677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altmann M., Wittmer,B., Methot,N., Sonenberg,N. and Trachsel,H. (1995) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae translation initiation factor Tif3 and its mammalian homologue, elF-4B, have RNA annealing activity. EMBO J., 14, 3820–3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de la Cruz J., Kressler,D. and Linder,P. (1999) Unwinding RNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: DEAD-box proteins and related families. Trends Biochem. Sci., 24, 192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond S.M., Caudy,A.A. and Hannon,G.J. (2001) Post-transcriptional gene silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nature Rev. Genet., 2, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalmay T., Horsefield,R., Braunstein,T.H. and Baulcombe,D.C. (2001) SDE3 encodes an RNA helicase required for post-transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis. EMBO J., 20, 2069–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein E., Caudy,A.A., Hammond,S.M. and Hannon,G.J. (2001) Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature, 409, 363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu-Scharf D., Jeong,B., Zhang,C. and Cerutti,H. (2000) Transgene and transposon silencing in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by a DEAH-box RNA helicase. Science, 290, 1159–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cogoni C. and Macino,G. (2000) Post-transcriptional gene silencing across kingdoms. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 10, 638–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogoni C. and Macino,G. (1999) Gene silencing in Neurospora crassa requires a protein homologous to RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Nature, 399, 166–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalmay T., Hamilton,A., Rudd,S., Angell,S. and Baulcombe,D. (2000) An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene in Arabidopsis is required for posttranscriptional gene silencing mediated by a transgene but not by a virus. Cell, 101, 543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smardon A., Spoerke,J., Stacey,S., Klein,M., Mackin,N. and Maine,E. (2000) EGO-1 is related to RNA-directed RNA polymerase and functions in germline development and RNA interference in C. elegans.Curr. Biol., 10, 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cogoni C. and Macino,G. (1999) Posttranscriptional gene silencing in Neurospora by a RecQ DNA helicase. Science, 286, 2342–2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ketting R., Haverkamp,T., van Luenen,H. and Plasterk,R. (1999) mut-7 of C. elegans, required for transposon silencing and RNA interference, is a homolog of Werner Syndrome helicase and RNaseD. Cell, 99, 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabara H., Sarkissian,M., Kelly,W., Fleenor,J., Grishok,A., Timmons,L., Fire,A. and Mello,C. (1999) The rde-1 gene, RNA interference and transposon silencing in C. elegans. Cell, 99, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Catalanotto C., Azzalin,G., Macino,G. and Cogoni,C. (2000) Gene silencing in worms and fungi. Nature, 404, 245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fagard M., Boutet,S., Morel,J.-B., Bellini,C. and Vaucheret,H. (2000) AGO1, QDE-1 and RDE-1 are related proteins required for post-transcriptional gene silencing in plants, quelling in fungi and RNA interference in animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 11650–11654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno S., Klar,A. and Nurse,P. (1991) Molecular and genetic analysis of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol., 194, 795–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prentice H. (1992) High efficiency transformation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe by electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arndt G., Patrikakis,M. and Atkins,D. (2000) A rapid genetic screening system for identifying gene-specific suppression constructs for use in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arndt G., Atkins,D., Patrikakis,M. and Izant,J. (1995) Gene regulation by antisense RNA in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Gen. Genet., 248, 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maundrell K. (1993) Thiamine-repressible expression vectors pREP and pRIP for fission yeast. Gene, 123, 127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 35.Moreno S. and Nurse,P. (1994) Regulation of progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle by the rum1+ gene. Nature, 367, 236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heyer W.-D., Sipiczki,M. and Kohli,J. (1986) Replicating plasmids in Scizosaccharomyces pombe: improvement of symmetric segregation by a new genetic element. Mol. Cell. Biol., 6, 80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frankhauser H. and Schweingruber,M. (1994) Thiamine-repressible genes in Schizosaccharomyces pombe are regulated by a Cys6 zinc-finger motif-containing protein. Gene, 147, 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grallert B., Kearsey,S., Lenhard,M., Carlson,C., Nurse,P., Boye,E. and Labib,K. (2000) A fission yeast general translation factor reveals links between protein synthesis and cell cycle control. J. Cell Sci., 113, 1447–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forbes K., Humphrey,T. and Enoch,T. (1998) Suppressors of Cdc25p overexpression identify two pathways that influence the G2/M checkpoint in fission yeast. Genetics, 150, 1361–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brun C., Dubey,D. and Huberman,J. (1995) pDblet, a stable autonomously replicating shuttle vector for Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene, 164, 173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Condeelis J. (1995) Elongation factor 1a, translation and the cytoskeleton. Trends Biochem. Sci., 20, 169–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glick B. and Schatz,G. (1991) Import of proteins into mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Genet., 25, 21–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshioka S., Kato,K., Nakai,K., Okayama,H. and Nojima,H. (1997) Identification of open reading frames in Schizosaccharomyces pombe cDNAs. DNA Res., 31, 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyake S. and Yamashita,S. (1998) Identification of sna41 gene, which is the suppressor of nda4 mutation and is involved in DNA replication in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Cells, 3, 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams T., Yon,J., Huxley,C. and Fried,M. (1988) The mouse surfeit locus contains a very tight cluster of four “housekeeping” genes that is conserved through evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 3527–3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belhumeur P., Lussier,M. and Skup,D. (1988) Expression of naturally occurring RNA molecules complementary to the murine L27′ ribosomal protein mRNA. Gene, 72, 277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mauro V. and Edelman,G. (1997) rRNA-like sequences occur in diverse primary transcripts: implications for the control of gene expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 422–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tranque P., Hu,M.-Y., Edelman,G. and Mauro,V. (1998) rRNA complementarity with mRNAs: a possible basis for mRNA–ribosome interactions and translational control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 12238–12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chu E. and Allegra,C. (1996) The role of thymidylate synthase as an RNA binding protein. Bioessays, 18, 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cogoni C. and Macino,G. (1997) Isolation of quelling-defective (qde) mutants impaired in posttranscriptional transgene-induced gene silencing in Neurospora crassa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 10233–10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elmayan T., Balzergue,S., Beon,F., Bourdon,V., Daubremet,J., Guenet,Y., Mourrain,P., Palauqui,J., Vernhettes,S., Vialle,T., Wostrikoff,K. and Vaucheret,H. (1998) Arabidopsis mutants impaired in cosuppression. Plant Cell, 10, 1747–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramer S., Elledge,S. and Davis,R. (1992) Dominant genetics using a yeast genomic library under the control of a strong inducible promoter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 11589–11593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawamukai M. (1999) Isolation of a novel gene, moc2, encoding a putative RNA helicase as a suppressor of sterile strains in Schizosaccharomyces pombe.Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1446, 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gudkov A. (1997) The L7/L12 ribosomal domain of the ribosome: structural and functional studies. FEBS Lett., 407, 253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.