Abstract

Background

Topical steroids are widely used in dermatology for their anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects, but misuse can cause skin thinning and systemic issues. In Ethiopia, where skin conditions are common, understanding how topical steroids are prescribed and used is essential for ensuring their safe and effective use.

Objective

The study aimed to assess topical steroids’ prescription and utilization pattern in Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DCSH) from February 1 to May 30, 2024.

Methodology

The study used a descriptive, cross-sectional design with a quantitative approach, analyzing data from 175 patient records on prescription and utilization patterns of topical steroids at DCSH. Participants were selected using a random sampling technique. Data were categorized and analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2010, with findings presented through descriptive statistics, including tables and figures.

Result

Eczematous dermatitis (31.49%) was the most common skin disease observed, followed by dermatophytosis (12.15%). Out of 304 drugs prescribed, averaging 1.73 per prescription, clobetasol (44.4%) and betamethasone (25.0%) were the most common topical corticosteroids. These steroids were primarily prescribed for eczema, dermatitis, pigmentary disorders, psoriasis, urticaria, and lichen planus. The commonly prescribed drugs were topical steroids 108[35.53%]. Generic names were used for 54.63% of the 108 topical steroids prescribed.

Conclusion

The study found that dermatitis and eczema are the most common skin conditions treated in dermatology clinics, with topical steroids being the main treatment. However, many prescriptions lacked details on the application site, treatment duration, and quantity. To improve safety and effectiveness, the study recommends community education, better dermatological services, and increased oversight in professional training.

Keywords: Prescription pattern, Topical steroids, Skin diseases

Introduction

The skin, the largest organ of the integumentary system [1], serves numerous functions beyond containing the body’s internal structures [2]. Skin diseases, affecting 30–70% of the global population, are a major public health concern and the most common reason for medical consultations [3]. These conditions pose significant financial and psychological burdens, causing high morbidity but relatively low mortality [4]. The prevalence and types of skin diseases vary by region due to ecological factors, genetics, hygiene, and social customs [5]. While skin disorders are common globally, they are particularly prevalent in developing countries, where infectious dermatoses comprise a significant portion of cases, including Tanzania and Ethiopia [6]. Understanding the epidemiology of skin diseases is crucial for effective healthcare resource allocation [7].

Steroidal hormones are secreted by the adrenal cortex located at the upper region of both kidneys and are majorly of two types, glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids [8]. In dermatology, the three effects of corticosteroids of primary importance are anti-inflammatory, ant-proliferative, and immune suppressive effects [9]. The mechanism of action of topical corticosteroids (TCs) exhibits anti-inflammatory, vasoconstrictive, anti-proliferative (anti-mitogenic), and immunosuppressive properties [10].

TCs are classified into four classes based on their potency or efficacy. Class one represents the weakest potency, while class four represents the strongest potency [9]. The classification helps healthcare professionals to determine the appropriate corticosteroid strength for various skin conditions. Since its introduction in the early 1950s, TCs have become the most prescribed drugs by dermatologists in an outpatient setting. These agents form the mainstay of treatment for many skin conditions. If used appropriately, they are safe and effective, and side effects are rare [11]. Topical corticosteroids act primarily by binding to glucocorticoid response elements in host DNA [12].

The absorption and effects of topical corticosteroids depend on factors like drug properties, concentration, application site, patient age, skin condition, and occlusion. While percutaneous absorption is better understood, cutaneous metabolism remains largely unclear [12]. The introduction of ultrahigh-potency topical corticosteroids has proved of important benefit for some hitherto corticoid-resistant dermatoses, but local side effects, unlike systemic ones, are relatively frequent and becoming even more with the introduction of the ultrahigh-potency topical corticosteroids [13]. Topical steroids are the most widely used over-the-counter medication in dermatological practice [14]. This can cause a wide range of side effects depending on the strength of the steroid used, the length of time it is used, and the area of skin treated [15].

Since their introduction in the 1950s, topical corticosteroids have revolutionized dermatological therapy, offering new possibilities for managing skin disorders effectively. Despite being the most useful drug for such treatment, they are known to produce serious local, systemic, and psychological side effects when overused or misused [16]. The available range of formulations and potency gives the flexibility to treat all groups of patients, different phases of disease, and different anatomic sites [15]. The cost of such irrational drug use is enormous in developing countries in terms of both scarce resources and the adverse clinical consequences of therapies that may have real risks, other than the side effects these classes of drugs cause [17]. The over-the-counter availability and affordability of potent topical corticosteroids have led to widespread misuse, resulting in significant adverse effects. Despite its prevalence, research on this issue remains limited, primarily focusing on facial misuse and its associated side effects [18].

In Ethiopia, the irrational use of TCs is quite common due to the unrestricted availability and use of TCs not only by the public but also by physicians and chemists. This practice is highly prevalent and sought after, owing to the quick relief of symptoms in different dermatological conditions and its nature of enhancing beauty for a certain period [19]. Although the use of topical steroids is not well documented in Ethiopia, it is evident that these drugs are widely used for cosmetic purposes and are sold in pharmacies, drug stores, rural drug vendors, and even cosmetic shops [20].

The utilization pattern of topical steroids in clinical settings is also not well documented in Ethiopia. Evaluating the utilization pattern of these drugs helps to make appropriate changes in the prescribing pattern to increase the therapeutic benefits and reduce adverse effects. Examining the OTC use of these drugs will also provide policymakers with the magnitude of the abuse of these drugs, which helps to design an intervention program. The study was conducted in the DCSH dermatology clinic.

This study aims to characterize the utilization and prescription patterns of topical steroids in DCSH Hospital. Evaluating the utilization patterns of commonly prescribed drugs is critical to enhancing therapeutic efficacy, reducing adverse effects, and providing feedback to prescribers. Therefore, the findings of this study will be useful in promoting rational drug use of topical steroids and improving the standards of medical care. The objective of the study is to evaluate the prescription and utilization pattern of topical steroids in DCSH.

Methods

Study area and period

The study was conducted in the dermatology clinic of Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DCSH), located in Dessie town, 401 km northeast of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Established in 1954, DCSH serves around 5 million people in the Amhara region and neighboring Afar region. With over 700 medical professionals and 250 administrative staff, the hospital provides inpatient and outpatient care, serving nearly half a million patients annually. DCSH has 15 wards, including Medical, Surgical, Paediatrics, and more, with an average of 170 patients visiting the dermatology clinic each month. The study analyzed dermatological cases from patient records at DCSH from February 1 to May 30, 2024.

Study design and population

A retrospective cross-sectional study design was utilized to assess the prescription and utilization pattern of TCs in DCSH. All outpatients treated in the dermatology clinic of DCSH, northeast Ethiopia were used as the source population in this study. All skin disease patients who visited the OPD dermatology clinics of DCSH during the data collection period which fulfills the inclusion criteria were part of the study.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

The sample size was determined or calculated by using the single population proportion formula. The sample size for the study was determined using a single population proportion formula by assuming a 95% confidence level, 5% marginal error, and 25% proportion of appropriate systemic steroidal prescription pattern.

|

According to a study done to assess the prescribing pattern for skin disease in dermatology OPD at Boru Meda Hospital, northeast, Ethiopia in the year 2018, the prevalence of topical steroid utilization was 25% [21]. This value was taken as a p-value to determine the sample size. Since the total number of dermatologic patients is less than 10,000 the following correctional formula was used.

nf = n/1 + n/N nf = ni×N /ni + N.

Where ni = initial sample size which was 288., nf = actual sample size, N = total number of Dermatologic patients who attend the dermatology outpatient clinic of DCSH, (N = 355).

|

By adding 10% contingency, a total of 175 patients were sampled.

Therefore, the sample size for the study was set at 175 patient medical charts containing topical prescriptions. A simple random sampling method was employed to select these charts.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patient medical charts with topical prescriptions were included in the study until the required sample size of 175 was reached. Patients’ medical records which were found to be incomplete, or completely lost were excluded from the study.

Study variables

The independent variables in the study were the patients’ demographic characteristics, including sex, age, and drug characteristics (dosage form). The dependent variables were the types of topical steroids utilized and the extent of topical steroid use.

Data collection instrument and technique

Quantitative data were collected using a data abstraction format. This format was designed to gather information on socio-demographic characteristics, diagnosis, history of self-prescribed steroid use, number of drugs prescribed, qualifications of prescribers, classes of drugs prescribed, whether topical steroids were included, names, dosage forms, strengths of the topical steroids, application frequency, treatment duration, application sites, and any treatment shifts in patients using topical corticosteroids from medical charts of patients. Health professionals from the dermatology clinic’s outpatient department at DCSH were recruited to review patient records, leveraging their expertise with the clinical record system, disease diagnoses, and interpretation of medication names and dosages.

Data quality assurance and analysis

The data abstraction format was pretested to ensure completeness and clarity. Data collectors received appropriate training before data collection began. The principal investigator supervised the data collection process to address any inconsistencies promptly. The quantitative data were manually cleaned, grouped, and entered into Microsoft Excel 2010. Analysis was conducted using simple descriptive statistics, including tables and figures.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of patients

175 patient records were taken using a Simple random sampling method and reviewed, revealing that patients were treated with drug therapy. As shown in Table 1, of the 175 patients, 106(60.57%) were from Dessie, and 69(39.43%) were from another area eastern Amhara region. Most patients were females accounting for 98(56.0%) and the males accounted for 77(44.0%). The minimum age observed was 2 days and the maximum was 86 years. The majority 44(25.14%) of patients were in the age group of 21–30 years followed by 40 (22.86%) from the age group of 0–10 years and 32(18.28%) from the age group 31–40 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of patients in DSCH, 2024 (n = 175)

| Characteristics | Frequency (n = 175) | Percent (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 77 | 44 | |||||

| Female | 98 | 56 | |||||

| age group | |||||||

| 0–10 year | 40 | 22.86 | |||||

| 11–20 year | 22 | 12.57 | |||||

| 21–30 year | 44 | 25.14 | |||||

| 31–40 year | 32 | 18.28 | |||||

| 41–50 year | 16 | 9.14 | |||||

| > 50 year | 21 | 12 | |||||

| Address | |||||||

| Dessie | 106 | 60.57 | |||||

| Out of Dessie | 69 | 39.43 | |||||

Out of the 175 patients included in the study, 169(96.57%) patients were diagnosed with a single skin disease and 6(3.43%) patients were diagnosed with two skin conditions hence 181 dermatoses were documented. Out of all skin diseases documented during the study period, the most single common skin diseases observed were eczema & dermatitis 57(31.49%), tinea (dermatophytosis) 22(12.15%), pigmentary disorder 18(9.94%), psoriasis 14(7.73%), urticaria 11 (6.08%), Lichen planus 4(2.21%), acne 4(2.21%), tinea versicolor 4(2.21%), altogether accounting for about 134(74.03%). Among eczema and dermatitis, the most common skin diseases were atopic dermatitis 24(42.1%) followed by eczema 12(21.0%), contact dermatitis 11(19.2%), and seborrheic dermatitis 7(12.2%). And lichen simplex chronicus 1(1.75%). The others were pityriasis Alba 2(3.5%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Skin disease patterns and frequency among the study population in, DCSH, 2024

| Disease | Frequency(n = 181) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| eczema and dermatitis | 57 | 31.49 |

| Tinea (dermatophytosis) | 22 | 12.15 |

| Pigmentary disorder | 18 | 9.94 |

| Psoriasis | 14 | 7.73 |

| Urticaria | 11 | 6.08 |

| Lichen planus | 4 | 2.21 |

| Acne | 4 | 2.21 |

| Tinea versicolor | 4 | 2.21 |

| Others* | 47 | 25.97 |

| total | 181 | 100 |

Others* include vasculitis, herpes zoster, Rosacea, discoid lupus erythematous, sweating disorder, leishmaniasis, scabies, folliculitis, carbuncle, cellulitis, legcorn, suppurative hidradenitis, genital wart, keratosis, dry face, chicken pox, onchomycosis, Impetigo, discoid lupus erythematous, malasma, keloid, hyperhydrosis

Prescribing pattern of dermatological drugs DCSH

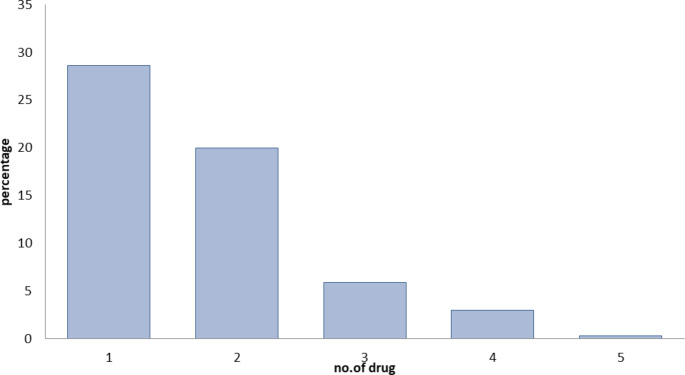

The total number of drugs prescribed for the patients included in the study was 304, with an average of 1.73 drugs per prescription. From these, 87(28.6%), 61(20.0%), 18(5.92%), 9(2.96%), and 1(0.33%) patients were prescribed 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 drugs, respectively (Fig. 1). Out of all the drugs prescribed, 222(73.0%) were prescribed to be administered by the topical route, and 82(26.97%) by the oral route.

Fig. 1.

Number of drugs per prescription in DCSH, 2024

As shown in Table 3, from the total of 304 drugs, the commonly prescribed drugs were topical corticosteroids (alone and combined) 108(35.53%) followed by antibacterial 41(13.49%), anti-fungal 31(10.19%), emollients and moisturizers 30(9.87%), keratolytic 20(6.58%), and antihistamines 14(4.6%).

Table 3.

The pattern of dermatological drugs prescribed in DCSH, 2024

| Drug group | Frequency (N = 304) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Topical steroids | 108 | 35.53 |

| Anti-bacterial | 41 | 13.49 |

| Anti-fungal | 31 | 10.19 |

| Emollients/moisturizers | 30 | 9.87 |

| Keratolytics | 20 | 6.58 |

| Antihistamine | 14 | 4.60 |

| Others* | 60 | 19.74 |

Others* include vitamin A derivatives, systemic steroids, scabicides, cleansing agents, anti-helminthic, antivirals, anti-pruritic and AlCl3 solutions, Protectants and astringents, and Bleaching agents

Skin conditions topical steroids were prescribed for in DCSH

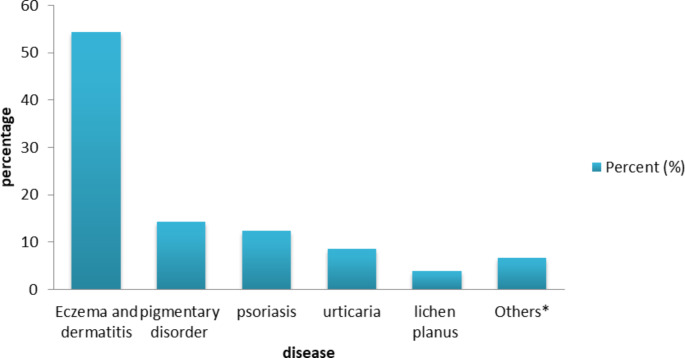

There were a total of 105 patients with skin conditions for which topical steroids were prescribed in the study period. The most common skin conditions of these were eczema/dermatitis 57(54.2%), pigmentary disorder 15(14.28%), psoriasis 13(3.0%), urticaria 9(3.0%) and lichen planus 4(5.3%), accounting for 86.6% of all the skin diseases topical corticosteroids were prescribed for (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The pattern of skin diseases topical steroids were prescribed for in DCSH, 2024. Others* include pityriasis Alba, hyperhidrosis, discoid lupus erythematous, malasma, keloid, and scabies

Prescribing pattern of topical steroids in DCSH

Out of the 175 patients included in the study, 105 (60.0%) patients were treated with topical corticosteroids. Out of all the topical steroids prescribed (108), about 56(51.85%) of the topical steroids were prescribed to male patients and the rest 52(48.14%) were prescribed to female patients. Of the 105 patients that received topical corticosteroid treatment, 102(97.14%) were prescribed only one topical corticosteroid and the remaining 3(2.86%) were prescribed 2 topical corticosteroids. There were no patients who received more than two topical steroids on one prescription. Hence, the total number of topical corticosteroids prescribed was 108, all the drugs prescribed in the dermatology clinic and all the topical steroids prescribed, were prescribed by dermatologists.

Out of all the patient records that had topical corticosteroids prescribed, the frequency of application was indicated in 60(55.55%). However, the site of application and duration were mentioned in 35(32.41%) and 57(52.78%) of the patient records, respectively. Almost 49(45.37%) of the topical steroids were prescribed using brand names and 59(54.63%) were prescribed using generic names of the drugs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Information included on prescriptions for topical steroids in DCSH, 2024

| Parameter | Frequency (N = 108) | Percent (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic | 59 | 54.63 | |||

| Brand | 49 | 45.37 | |||

| Site of application | 35 | 32.41 | |||

| Frequency of application | 60 | 55.55 | |||

| Duration of application | 57 | 52.78 | |||

From all the topical corticosteroids prescribed, 72(66.6%) were ointments, 8(7.4%) were creams, 2(1.85%) were in lotion form and 26(24.07%) were in powder form to be prepared extemporaneously with other drugs (Table 5).

Table 5.

Type of dosage forms of topical steroid used in DCSH, 2024

| type of dosage form | Frequency(108) | Percent (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ointments | 72 | 66.67 | ||

| Cream | 8 | 7.41 | ||

| Lotion | 2 | 1.85 | ||

| Powder | 26 | 24.07 |

Types of the topical corticosteroids in DCSH

The most prescribed topical corticosteroids were clobetasol propionate 48(44.4) and betamethasone dipropionate 27(25.0%), which are usually classified as very potent topical corticosteroids. These were followed by mometasone furoate 23(21.29%) and hydrocortisone acetate 4(3.7%), which are potent and mild topical corticosteroids, respectively. The other topical corticosteroids prescribed were Clocortolone pivalate (Cloderm) 5(4.63%), and methylprednisolone aceponate 1(0.92%) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Distribution of types of topical steroids and combinations prescribed in DCSH, 2024

| Topical steroid | Frequency(N = 108) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Clobetasol propionate | 48 | 44.44 |

| Betamethasone dipropionate | 27 | 25 |

| Mometasone furoate | 23 | 21.29 |

| Hydrocortisone acetate | 4 | 3.70 |

| Clocortolone pivalate | 5 | 4.63 |

| methylprednisolone aceponate | 1 | 0.92 |

Combined and concomitantly prescribed drugs with the topical steroids in DCSH

Out of all the topical corticosteroids prescribed, 82(75.92%) were prescribed alone and the rest 26(24.07%) were prescribed in combination with other classes of drugs (Table 7).

Table 7.

Form of the topical steroids prescribed in DCSH, 2024

| Form | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Alone | 82 | 75.92 |

| Combined | 26 | 24.07 |

| Total | 108 |

Topical steroid-induced skin diseases documented in DCSH

There were two cases of topical steroid-induced skin diseases documented from the patient records reviewed. Out of the two cases, one was steroid-induced acne caused by using Beprosone® (betamethasone dipropanoate 0.05%), a potent topical steroid. It was not specified whether the Beprosone® was prescribed by a health professional or if it was bought OTC. The other steroid-induced rosacea was the second steroid-induced skin disease, which was caused using a topical corticosteroid, but the name and source of the drug were not indicated in the patient history record.

OTC use of topical steroids and their consequences in DCSH

The use of topical steroids is a very common practice in the community and in the patients they encounter. They also pointed out that it is the young female in urban areas, within the reproductive age group that commonly use these products without prescription. Out of 175 patients, 15 of them, 13 are females and 2 are males had a history of previous OTC topical steroid use in the study period.

Discussion

The present study focused on dermatology, particularly in the prescription and utilization pattern of topical steroid agents in the dermatology clinic in DCSH. Additionally, the study covers common skin diseases using quantitative methods.

Skin diseases rank as the fourth most prevalent human disease, impacting nearly one-third of the global population. Despite their visibility, the burden they impose is often underestimated [22]. This issue is particularly severe in resource-limited countries, where skin diseases are among the most common reasons for hospital visits [23]. Although these conditions generally have low mortality rates, their morbidity is significant. This is partly due to the limited resources allocated to skin healthcare and the insufficient number of dermatologists available to handle the growing number of cases [24]. Similarly, this study has shown that dermatologists face a very high workload due to their inadequate numbers.

In this study, the female-to-male ratio was found to be 1.27:1. This result aligns with findings from research conducted at Addis Alem Primary Hospital in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia [25], as well as numerous other studies from various countries [26]. The higher number of female patients in the clinic could be due to women’s greater awareness and concern for health-related matters [27].

The epidemiology of skin diseases has been periodically studied and assessed. These studies have been used to examine and analyze the prescribing patterns of medications for various skin conditions in dermatology departments [28]. In Ethiopia, skin diseases affect individuals of all ages, with children being particularly vulnerable [29]. However, this study found that adults aged 21–30 years were the most affected group, followed closely by children aged 0–10 years, with no significant difference between these groups. A similar pattern was documented in research conducted at Boru Meda Hospital [21].

The most frequently observed skin conditions were eczema and dermatitis, followed by infectious diseases. This pattern is consistent with findings from studies conducted at Finote Selam Hospital in the West Gojjam Zone, ALERT Hospital in Addis Ababa, Boru Meda Hospital [30, 31 & 21], and other countries [32].

In this study, the most frequently prescribed drug group was topical steroids and their combinations, followed by antibacterial and antifungal medications. Similar results were observed in Boru Meda Hospital and other study conducted at Ayder Referral Hospital [19, 21]. The analysis of patient records revealed that inflammatory skin conditions, particularly eczema and dermatitis, were the most common diagnoses (31.49%). This explains the high usage of topical steroids, as they are the primary treatment for reducing inflammation in eczema and dermatitis [10]. Antibacterial medications were the second most prescribed drug class in this study. However, a study conducted in India reported different findings, with antifungals (23.15%) being the most prescribed drugs, followed by steroids (19.61%) and antibiotics (16.72%) [33].

In the current study, the average number of drugs prescribed per prescription was 1.73. This figure is lower compared to studies conducted at Borumeda Hospital [21] and in other countries [34, 35]. The findings suggest that the DSCH dermatology clinic aims to minimize the number of drugs per prescription, thereby reducing the potential risk of side effects from drug interactions.

In this study, most drugs were prescribed via the topical route, followed by oral administration. A similar trend was observed in a study conducted in India [34]. The high percentage of topical prescriptions can be attributed to the advantages of this route, such as avoiding systemic toxicity and side effects, making it the preferred method in dermatology [21, 34, 35].

The study found that topical corticosteroids were the most frequently prescribed drugs for outpatients at DCSH dermatology clinics (35.53%). Similar studies at Borumeda Hospital and Ayder Referral Hospital [19, 21] reported comparable results. Among the prescribed topical steroids, clobetasol was the most common, followed by betamethasone dipropionate, mometasone, and hydrocortisone. This pattern aligns with findings from an Indian Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital and the Dermatology Department at Azeezia Institute of Medical Sciences and Research [32, 35].

In this study, 75.93% of topical corticosteroids were prescribed as single drugs, while the remainder were combined with other medications. Keratolytics were the most frequently combined drug group, as they help reduce hyperkeratosis and enhance the absorption of different treatments [36]. This differs from findings at the Dermatology Department of Azeezia Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, India [32].

Drugs should be prescribed by their generic names to avoid confusion and reduce costs. The current study found that 54.63% of prescriptions were nonproprietary, while 45.37% used brand names for outpatients. This result is consistent with findings from a study conducted at the Dermatology Department of Azeezia Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, India [32].

The frequency of topical steroid application was recorded in 55.55% of patient records, which is lower than Boru Meda Hospital [21] but higher than the Dermatology Department at Azeezia Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, India [32]. The analysis revealed that prescribing information was often inadequate. The duration of application was specified in 52.78% of records, lower than studies in both a tertiary care hospital in India [34] and Boru Meda Hospital [21]. The site of application was indicated in 32.4% of cases, lower than Boru Meda Hospital [21] but higher than the Azeezia Institute study [32].

Topical corticosteroids were primarily prescribed to manage skin conditions such as eczema/dermatitis, pigmentary disorders, psoriasis, urticaria, and lichen planus. This finding aligns with studies conducted at an Indian Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital and other research in India [35, 37].

Topical steroid-induced skin conditions are frequently reported, with many patients acquiring corticosteroids over the counter [38]. In a study involving community pharmacies and cosmetic shops, over two-thirds of participants obtained topical corticosteroids OTC, mainly for beautification purposes (59.8%). More than half of these individuals experienced adverse drug events, primarily affecting the face [20]. Our study identified two cases of steroid-induced skin conditions: one with acne and another with rosacea, out of 175 patients. Additionally, 15 patients (13 females and 2 males) reported a history of OTC topical steroid use during the study period.

Limitations of this study

This study on the utilization and prescription patterns of topical steroids at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital may have limitations, including restricted generalizability due to its single-site design, limited sample size, potential inaccuracies in retrospective data, and lack of patient adherence or clinical outcome analysis. Socioeconomic influences could affect the findings, highlighting the need for more broader and comprehensive future studies.

Conclusion

Most records for prescribed topical steroids lacked sufficient details on the application site, duration, and quantity, and often used generic names. Clobetasol dipropionate and betamethasone dipropionate were the most frequently prescribed, mainly for conditions like eczema, dermatitis, pigmentary disorders, psoriasis, urticaria, and lichen planus. Despite their critical role in dermatological care, topical steroids are often misused due to their easy availability. To address this issue, increased awareness among healthcare professionals and the public and regulatory measures to limit over-the-counter access are essential. Healthcare providers should focus on allergic conditions and infections, improving record-keeping with detailed patient information, ensuring steroids are dispensed only with prescriptions, and enhancing community education on proper steroid use.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital and the participants for their cooperation.

Author contributions

all authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; participated in the drafting of the article or critically reviewing it for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be responsible for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No funding was received for this manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before data collection began, the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Wollo University College of Medicine and Health Sciences. An official permission letter was obtained from the same institution. To maintain confidentiality, patient names were not used; instead, Medical Record Numbers (MRNs) were utilized. Patient confidentiality was strictly upheld, with no names recorded in the data collection format. Additionally, patients were informed that their medical information would not be disclosed to any external parties, ensuring confidentiality during data abstraction from medical records.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pathak AK et al (2016) Study of drug utilization pattern for skin diseases in dermatology OPD of an Indian tertiary care hospital-A prescription survey. J Clin Diagn Res 10(2):01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vary JC, O’Connor KM (2014) Common Dermatol Conditions Med Clin 98(3):445–485 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Richard M et al (2022) Prevalence of most common skin diseases in Europe: a population-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 36(7):1088–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain S et al (2016) Prevalence of skin diseases in rural Central India: a community-based, cross-sectional, observational study. J Mahatma Gandhi Inst Med Sci 21(2):111–115 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aman S et al (2017) Pattern of skin diseases among patients attending a tertiary care hospital in Lahore, Pakistan. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 12(5):392–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basnet B et al (2015) Burden of skin diseases in Western Nepal: a hospital-based study. AJPHR 3(5):64–66 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dlova NC et al (2015) The spectrum of skin diseases in a black population in D urban, K waZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Dermatol 54(3):279–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohana C et al (2022) Rev Misuse Topical Corticosteroids IJMS 6(1):2

- 9.. Kraft, M., Soost, S., Worm, M. (2018). Topical and Systemic Corticosteroids. In: John, S., Johansen, J., Rustemeyer, T., Elsner, P., Maibach, H. (eds) Kanerva’s Occupational Dermatology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40221-5_92-2

- 10.Uva L et al (2012) Mechanisms of action of topical corticosteroids in psoriasis. Int J Endocrinol 1:561018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das A, Panda S (2017) Use of topical corticosteroids in dermatology: an evidence-based approach. Indian J Dermatology 62(3):237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta AB et al (2016) Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatology Venereol Leprology 82:371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher DA (1995) Adverse effects of topical corticosteroid use. West J Med 162(2):123 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dey VK (2014) Misuse of topical corticosteroids: a clinical study of adverse effects. Indian Dermatology Online J 5(4):436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathi SK, Paschal D (2012) Rational and ethical use of topical corticosteroids based on safety and efficacy. Indian J Dermatology 57(4):251–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coondoo A et al (2014) Side-effects of topical steroids: a long overdue revisit. Indian Dermatology Online J 5(4):416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Souza P, Rathi SK (2018) Rational Use of Topical Corticosteroids. A Treatise on Topical Corticosteroids in Dermatology: Use, Misuse and Abuse: 117–127

- 18.Nagesh T, Akhilesh A (2016) Topical steroid awareness and abuse: a prospective study among dermatology outpatients. Indian J Dermatology 61(6):618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zewdu FT et al (2017) Topical corticosteroid misuse among females attending at dermatology outpatient department in Ethiopia. Trichol Cos-metol Open J 1(1):33–36 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsegaye M et al (2018) Prevalence of topical corticosteroids related adverse drug events and associated factors in selected community pharmacies and cosmetic shops of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Sudan J Med Sci 13(1):62–77 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tegegne A, Bialfew F (2018) Prescribing pattern for skin diseases in dermatology OPD at Borumeda hospital. Northeast, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flohr C, Hay R (2021) Putting the burden of skin diseases on the global map. Blackwell Publishing Ltd Oxf UK 184:189–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paek SY et al (2012) Skin diseases in rural Yucatan. Mexico Int J Dermatology 51(7):823–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olanrewaju F et al (2018) Clinical spectrum of skin diseases in a newly established dermatology clinic in south-western Nigeria: a preliminary study. Niger J Med 27(4):300–305 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asressie M (2022) Proportion of Skin Diseases and Associated Factors in Addis Alem Primary Hospital from June 2020-May 2021, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study (Doctoral dissertation)

- 26.Lindberg M et al (2014) Self-reported skin diseases, quality of life and medication use: a nationwide pharmaco-epidemiological survey in Sweden. Acta dermato-venereological 94(2):188–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madla CM et al (2021) Let’s talk about sex: differences in drug therapy in males and females. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 175:113804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rekha M et al (2015) Study on prescribing pattern in skin Department of a Teaching Hospital. Exec Editor 6(4):146 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mengist Dessie A et al (2022) Prevalence of Skin Disease and Its Associated Factors Among Primary Schoolchildren: A Cross-Sectional Study from a Northern Ethiopian Town. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology: 791–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Aynalem SW (2017) Pattern of skin disease among clients attending dermatologic clinic at Finote Selam Hospital, West Gojjam Zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Am J Health Res 5:178–182 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gimbel DC, Legesse TB (2013) Dermatopathol Pract Ethiopia Archives Pathol Lab Med 137(6):798–804 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Bylappa BK et al (2015) Drug prescribing pattern of topical corticosteroids in dermatology unit of a tertiary-care hospital. Int J Med Sci Public Health 4(12):1702

- 33.Bijoy K et al (2012) Drug prescribing and economic analysis for skin diseases in dermatology OPD of an Indian tertiary care teaching hospital: a periodic audit. Indian J Pharm Pract 5(1)

- 34.Tikoo D et al (2011) Evaluation of drug use pattern in dermatology as a tool to promote rational prescribing. JK Sci 13(3):128 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukherjee S (2016) Assessment of corticosteroid utilization pattern among dermatology outpatients in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Eastern India. Int J Green Pharm 10(04)

- 36.Chiricozzi A, Chimenti S (2012) Effective topical agents and emerging perspectives in the treatment of psoriasis. Expert Rev Dermatology 7(3):283–293 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karekar SR et al (2020) Use of topical steroids in dermatology: a questionnaire-based study. Indian Dermatology Online J 11(5):725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kijima T et al (2023) Adrenal Insufficiency Following Prolonged Administration of Ultra-high Topical Steroid: a case of refractory dermatitis. Cureus 15(4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.