Abstract

The release of allelochemicals is one of the contributing factors to the success of invasive plants in their non-native ranges. It has been hypothesised that the impact of chemicals released by a plant on its neighbours is shaped by shared coevolutionary history, making natives more susceptible to “new” chemicals released by introduced plant species (novel weapons hypothesis). We explored this hypothesis in a New Zealand system where the two invasive plants of European origin, Cytisus scoparius (Scotch broom) and Calluna vulgaris (heather) cooccur with natives like Chionochloa rubra (red tussock) and Leptospermum scoparium (mānuka). We characterised the chemical composition of root extracts of broom, heather, red tussock and mānuka using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and then investigated the influence of aqueous root extracts at different concentrations (0.1%, 1%, 5%, 50% and 100% v/v) on mānuka seed germination and seedling growth (root and shoot length and biomass), using deionised water as control. The results show clear distinctions in the chemical composition of the four plants’ root extracts, with 4-O-methylmannose dominating the broom extract and (E)-pinocarveol the heather extract, while 16-kaurene and methyl palmitate were abundant in both mānuka and tussock extracts. We found a significant effect of invasive plant (heather and broom) root extracts on mānuka germination at all concentrations tested, and adverse effects on seedling growth and biomass only at higher concentrations (≥ 5%). Broom displayed stronger allelopathic effects than heather at the highest concentration (100%). For extracts of conspecific and other native species (mānuka and red tussock) allelopathic effects were only observed at very high concentrations (50 and 100%) and were generally weaker than those observed for invasive plants. These results show that while both native and invasive plants produce chemicals with allelopathic potential, native species are likely to be more vulnerable to the allelopathic effects of species they did not co-evolve with, supporting the novel weapons hypothesis. However, this study also highlights differences in allelopathic potential between invasive species.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10886-024-01550-6.

Keywords: Allelochemicals, Allelopathy, Alien species, Biological invasion, Indigenous species, Novel weapons hypothesis

Introduction

Invasive plants pose significant threats to native biodiversity, with this predicament worsening due to increased global trade, human travel, and climate change (Chapman et al. 2016; Pimentel et al. 2001; Van Der Wal et al. 2008). Relative to natives, most invasive plant species possess advantageous traits related to physiology, leaf-area allocation, shoot allocation, growth rate, and size; bolstering their performance and dominance (Van Kleunen et al. 2010) through exploitative competition (i.e., the use of resources by one species reduces their availability to others). However, invasive plants may also prevent native species’ access to resources via interference competition (i.e., by affecting the resource-attaining behavior of other individuals), through the use of allelochemicals (Amarasekare 2002).

The novel weapons hypothesis (NWH) posits that some plants release biochemicals that highly suppress receiver organisms in their invaded ranges, with which they didn't co-evolve (Callaway and Ridenour 2004). These chemicals can be volatile and semi-volatile compounds from leaves and roots or non-volatile compounds from foliar leachates, decaying litter, and root exudates (Clavijo McCormick et al. 2023; Inderjit and Duke 2003; Inderjit et al. 2011). The available evidence supports that biochemicals released through the roots of many invasive plants are effective in inhibiting native competitors’ germination and growth, e.g., (Li and Jin 2010; Qu et al. 2021; Rudrappa et al. 2007; Thorpe et al. 2009).

Interestingly, NWH further suggests that plant allelochemicals are less effective against natural competitors in the emitter’s native range because of shared coevolutionary history (Callaway and Ridenour 2004). The species-specific nature of allelopathy highlights the need for multi-species experimental designs to understand the complexity of chemical warfare in invasion scenarios. For example, the invasive Centaurea diffusa had a weaker negative effect on grass species from its native communities than those from North America, which was attributed to differential effects of C. diffusa root exudates on these species (Callaway and Aschehoug 2000). Similarly, ( ±)-catechin in the root exudate of Centaurea maculosa did not affect plants in its native range in Romania but reduced the growth of plants in USA, where C. maculosa is invasive (Thorpe et al. 2009).

Like in other parts of the world, numerous plants introduced to New Zealand have established and spread, becoming invasive. Scotch broom (henceforth broom) Cytisus scoparius (Leguminosae) and heather, Calluna vulgaris (Ericaceae) are among the most dominant noxious weeds on the Central Plateau of the North Island, home to the Tongariro National Park, a UNESCO dual world heritage site (Buddenhagen 2000; Chapman and Bannister 1990), endangering this unique ecosystem. The spread of heather and broom in the area has caused a significant decline in native plants and changes in arthropod distribution, e.g., (Chapman and Bannister 1990; Effah et al. 2020a, b; Keesing 1995; Pearson et al. 2024). Two native plants, which are particularly affected by the spread of invasive weeds are red tussock (henceforth tussock), Chionochloa rubra (Poaceae) and mānuka, Leptospermum scoparium (Myrtaceae).

Previous studies suggest that both heather and broom possess some chemical weapons affecting their competitors. For example, there are studies reporting the inhibition of red clover root and hypocotyl growth (Ballester et al. 1982) and prevention of Scots pine seeds germination (Hille and Den Ouden 2005) by aqueous extracts of heather leaves. Analogously, chemical compounds present in flowering broom foliar extracts were phytotoxic for agricultural weeds (Pardo-Muras et al. 2018, 2020b). Heather foliar volatiles are known to inhibit volatile emissions of a New Zealand native plant (mānuka), potentially impacting its interactions with herbivores and pollinators (Effah et al. 2020b, 2022a). However, these studies involve above-ground tissues, and root allelochemicals and their effect on native plants’ germination and growth, remain poorly understood for these species.

To fill this knowledge gap, we designed a series of experiments to explore chemicals in the root extracts of native and invasive species, and their effect on the germination and seedling growth of a native plant (mānuka) on the Central Plateau. Mānuka was selected as target species due to its cultural and economic importance to New Zealand, linked to the unique medicinal properties of the plant and its honey (Bil et al. 2016; Effah et al. 2022b; Patel and Cichello 2013). First, we characterised the chemical composition of the root extracts of invasive (heather and broom) and native species (mānuka and tussock). We then tested the effects of aqueous root extracts on the seed germination and seedling growth (root length, shoot length and biomass) of mānuka. We explored a range of concentrations (0.1%, 1%, 5%, 50% and 100% v/v), to reflect natural situations, where compound concentrations will vary depending on the distance between emmiting and receiving plants, the soil matrix, the chemical properties of the compounds, and compound interactions among other factors (Blum 2006).

Methods and Materials

Collection of Root Materials

In April 2021, roots of mānuka, tussock, broom and heather were collected from three locations on the Central North Plateau (Long. 175.74525–Lat. −39.3023; Long. 175.739466– Lat. −39.3118; Long. 175.7395–Lat. −39.311783). Each location had a natural population of all four plants. Five individuals of each plant species were sampled at each location. The collected samples were immediately wrapped with aluminium foil and stored in a portable cooler for transport. Later on the same day, the samples were stored at −20 °C for four days before further processing.

Preparation of Root Extracts for GC–MS Analysis

To explore the chemical composition of root extracts, root samples were thoroughly washed separately with tap water, followed by deionised water. 5 g of each plant’s root material was chopped into small sizes and soaked in 20 ml of methanol (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich) with 10 ng mL−1 nonyl acetate as an internal standard for 48 h at 24 °C. Extracts were then centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected, sieved with a 0.2 µ syringe filter and stored at −80 °C. Fifteen extracts were prepared and analysed for each plant species, with 5 extracts per site per species.

For chemical analysis, 200 µ of extracts were transferred into GC–MS vials and analysed using gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (QP2010; GCMS Solution version 2.70, Shimadzu Corporations, Kyoto, Japan), with a 30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm TG-5MS capillary column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and helium as the carrier gas. The carrier gas parameters were as follows; pressure 53.5 kPa, total flow 14.0 mL/min, column flow 1.0 mL/min, linear velocity 36.3 cm/s and purge flow 3.0 mL/min. The temperature programme was; initial oven temperature of 50 °C held for 3 min, then increased to 180 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min and then to 240 °C at 10 °C/min. The injection temperature was 250 °C, and injection was done in a splitless mode. Using the Shimadzu postrun analysis software, compounds were tentatively identified by comparing target spectra to the mass spectra supplied by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Chromatographic analyses were performed in scan mode, and peaks were quantified relative to the internal standard, then divided by the fresh weight of plant material.

Seed Germination and Growth Trials

Effects of the four plants’ root extracts on mānuka seed germination and seedling growth were tested in the laboratory. Mānuka seeds were purchased from NZseeds (nzseeds.co.nz), and full seeds were sorted for the trials. A stock extract was separately prepared for each plant by homogenising the fresh root materials collected from the three locations. Aqueous extracts were prepared in the same manner as the GC–MS analysis but with deionised water (DW) as a solvent instead of methanol and stored at −80 °C for a week. To investigate seed germination and seedling growth, Petri dishes were lined with filter paper and moistened with 1.5 ml of one of the prepared solutions. Ten mānuka seeds were placed in the Petri dish, covered, and sealed with parafilm. Petri dishes were kept in a temperature-controlled room (24 °C), with 16/8 h of light/dark period.

Two sets of germination trials were performed. In the first trial, low concentrations (0.1% and 1% v/v) of extract were prepared from the stock and applied to mānuka seeds. This trial was conducted in November 2021, and seedlings were harvested after 25 days. A follow-up trial was conducted in January 2022, with higher concentrations (5%, 50% and 100% v/v), and seedlings were harvested after 10 days. The number of replicates (petri dishes) per treatment was 7 for the first and 5 for the second trial. Mānuka seeds tested in both trials belonged to the same seed batch.

Germination rates were estimated in the first 12 and 10 days for the first and second trials, respectively. Inconsistency in days was due to COVID-19 regulations on laboratory visitation. Germinated seeds were recorded daily when possible. At the end of each trial, seedlings were harvested and their root and shoot lengths were measured. Roots and shoots were then separated and oven-dried (60 °C) for 48 h to estimate below and aboveground biomass.

We acknowledge that the chemical composition of the extracts used for the chemical analyses and germination trials may vary due to the differences in solubility of compounds in methanol and water.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using R V.4.1.0 (R Core Team 2021). The chemical composition of root extracts was explored using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). PCA was performed with transformed data (log10x + 1) using the “FactoMiner” package (Lê et al. 2008).

The non-parametric Kaplan–Meier estimate was used to determine the likelihood of mānuka seeds germinating under the respective treatments. We chose this approach for its predictive capacity to analyse time-to-event and ability to use non-normally distributed data without transformation (Romano and Stevanato 2020). This analysis was performed using the “survfit” function in the “survival” package (Therneau and Lumley 2015), followed by the log-rank test to investigate the differences between groups (Goel et al. 2010).

Shoot and root length and biomass were compared between treatments using generalised linear models (GLMs), assuming log-normal distribution. GLMs were separately performed for each concentration, with extracts (mānuka, tussock, broom, heather and DW) as explanatory variable. The significance of predictors was estimated using the likelihood ratio test, and when significant, the “relevel” function was used to perform a series of contrasts between groups.

We used all data (germination, shoot and root length and biomass) to calculate the allelopathic response index (RI) of aqueous root extracts on mānuka. RI was determined based on Williamson and Richardson (1988), with negative values indicating inhibition and high positive values suggesting a potential stimulatory effect. The allelopathic response index was calculated using the formulas; when T ≥ C, RI = 1-C/T; when T < C, RI = T/C-1. Where RI is the allelopathic response index, T is the treatment value, and C is the control value.

Results

Composition of Root Extracts

Forty-two compounds, including terpenoids, phenolics, alkaloids, alcohols, and esters, were tentatively identified in the root extracts of all four plants, with some compounds being species-specific, while others were present in two or more plant species in varying quantities (Supplementary Table S1). For example, the three most dominant compounds in heather root extract were (E)-pinocarveol, alloaromadendrene, and methyl palmitate, while 4-O-methylmannose, hexaglycerol, and methyl palmitate were detected in higher quantities in the broom extract. Higher amounts of 16-kaurene, methyl palmitate, and spathulenol were identified in mānuka root extract, while that of tussock was dominated by methyl palmitate, alloaromadendrene, and 16-kaurene (Supplementary Table S1).

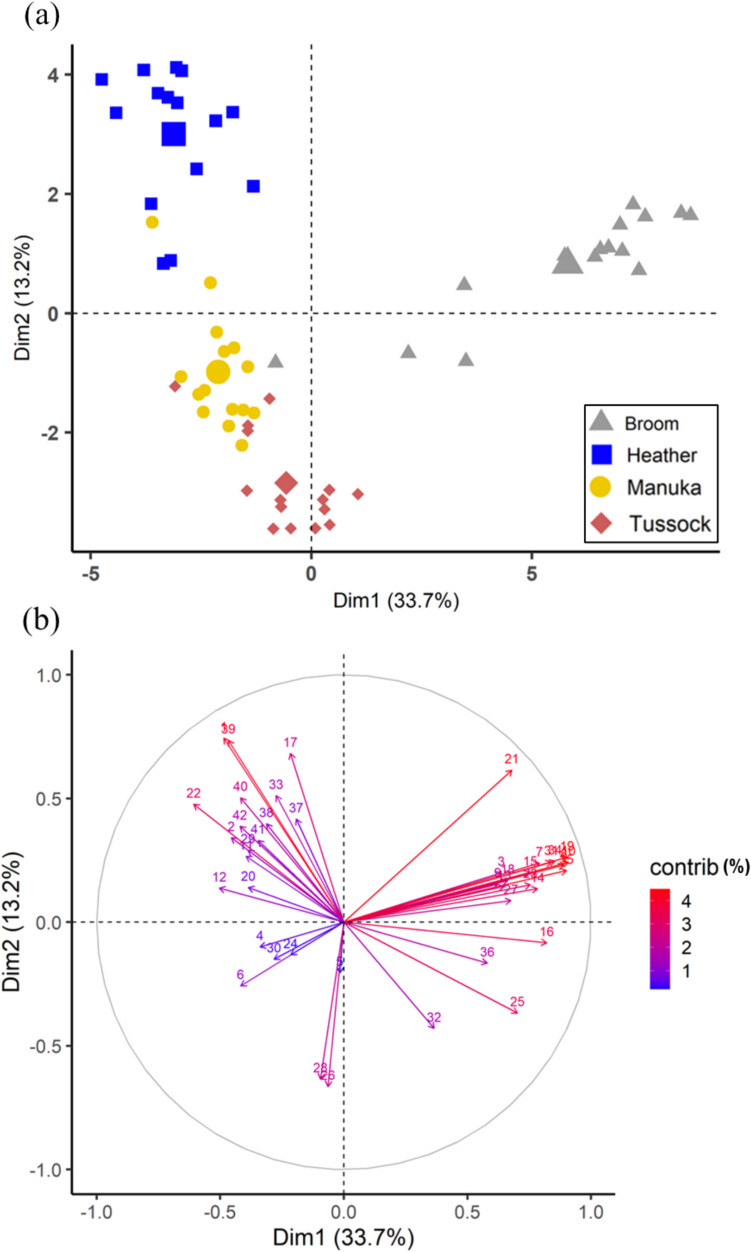

Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), we classified the four plants based on the chemical composition of their root extracts. The first two components explained over 45% of the observed variation, and these dimensions showed a clear separation between plant species (Fig. 1a). The first component was characterised mostly by compounds in high quantities in broom’s extract, such as 4-O-methylmannose (the most aboundant compound in broom extracts), and others such as 3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyran-4-one, 3-methylisoquinoline, cyclosativene, glycerol, hexaglycerol, linolenic acid, methyl linoleate, nonadecanol, octadecanol and octopamine. Whereas compounds, including (E)-pinocarveol (the most abundant compound in heather extracts), thymol, nopol, nonanol, methyl palmitoleate, methyl oleate, methyl docosanoate and guaiacol had a high contribution to the second component, with higher quantities of these compounds often identified in the heather extract (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table S1 and S2).

Fig. 1.

Principal component analysis based on the chemical compounds identified in the root extracts of mānuka, tussock, broom and heather (n = 15). (a) score plot of individuals, (b) loading plot of chemical compounds, with colours representing their contributions (contrib)

Numbers in the graph represent the following compounds; (1) (E)-pinocarveol, (2) (E)-β-caryophyllene, (3) 1-(4-pentenyl)pyrrolidine, (4) 16-kaurene, (5) 2,3-dihydroxy-3-phenyl propanoic acid, (6) 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol, (7) 3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-2,3-dihydro-4H-pyran-4-one, (8) 3-methylisoquinoline, (9) 4-(6-methoxy-3-methyl-2-benzofuranyl)−3-buten-2-one, (10) 4-O-methylmannose, (11) alloaromadendrene, (12) borneol, (13) copaene, (14) coumarine-3-carbohydrazide, N2-(1-methylethenylideno), (15) cyclosativene, (16) glycerol, (17) guaiacol, (18) hexadecanol, (19) hexaglycerol, (20) limonene, (21) linolenic acid, (22) methyl docosanoate, (23) methyl linoleate, (24) methyl linolenate, (25) methyl octadecanoate, (26) methyl oleate, (27) methyl palmitate, (28) methyl palmitoleate, (29) methyl salicylate, (30) methyl tetradecanoate, (31) nonadecanol, (32) nonanol, (33) nopol, (34) octadecanol, (35) octopamine, (36) oxime-methoxy-phenyl, (37) pinocamphone, (38) spathulenol, (39) thymol, (40) α-patchoulene, (41) α-terpineol, (42) γ-elemene.

Seed Germination

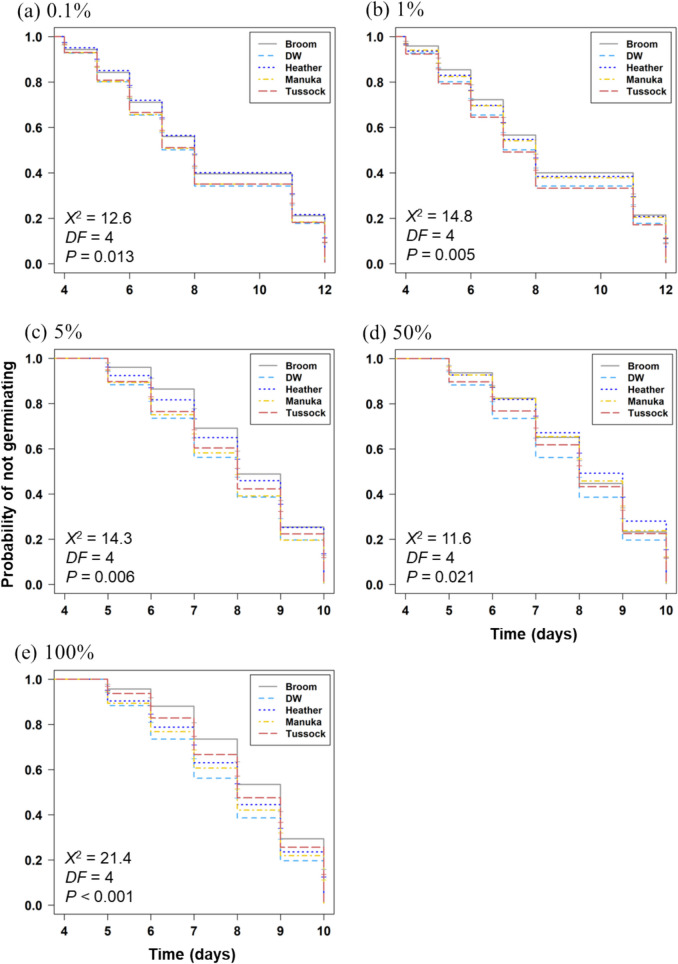

The number of germinated seeds was recorded and analysed using Kaplan–Meier estimates, with the log-rank test for differences. There was a significant difference between the tested extracts at all concentrations (Fig. 2). At 0.1% and 5% concentration, the estimates show a higher probability of seeds treated with heather and broom extract not germinating at any measured time (Fig. 2a and c). Applying 1% broom extract also consistently delayed germination (Fig. 2b). Seeds treated with 50% broom, heather and mānuka extracts had similar negative effects on germination on day 5 and 6, which diverged from day 7 with heather extracts application resulting in much higher delays (Fig. 2d). Regarding 100% extracts, broom was linked to the highest probability of seeds not germinating at all measured times (Fig. 2e). For extracts of conspecifics (mānuka) and other native species (tussock), a significant difference from the control treatment (deionised water) was only observed at higher concentrations (50 and 100%).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of germination by mānuka seeds treated with broom, heather, mānuka and tussock aqueous root extracts and deionised water (DW). Curves showing 95% confidence intervals of seeds not germination in response to treatment. Chi-square value (X2), degree of freedom (DF) and P – value (P) are presented in each figure

Seedling Length and Biomass Estimates

The 0.1% and 1% concentrations had no significant effect on seedling length. These results and test statistics for pairwise comparisons are presented in Supplementary Table S3 and S4. Application of 5% extracts did not have significant effects on root length (LRT; X2 = 6.95, df = 4, P = 0.138) and shoot length (LRT; X2 = 7.60, df = 4, P = 0.107), although broom and heather extracts had marginal negative effects. Seeds treated with 50% of extracts showed significant differences in their root length (LRT; X2 = 12.87, df = 4, P = 0.012) and shoot length (LRT; X2 = 14.96, df = 4, P = 0.005), with broom and heather extracts significantly reducing root and shoot length compared to deionised water. This was also true for 100% extracts, with significant differences in root (LRT; X2 = 29.48, df = 4, P < 0.001) and shoot length (LRT; X2 = 15.46, df = 4, P = 0.004), with broom extract significantly inhibiting root and shoot growth (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 3.

Seedling length of mānuka treated with different concentrations of broom, heather, mānuka and tussock aqueous root extracts, with deionised water as a control. Y-axis shows mean ± SE length, and x-axis represents applied concentrations. Series of contrasts between groups performed using the relevel functions and asterisks and letters indicate significant differences (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001)

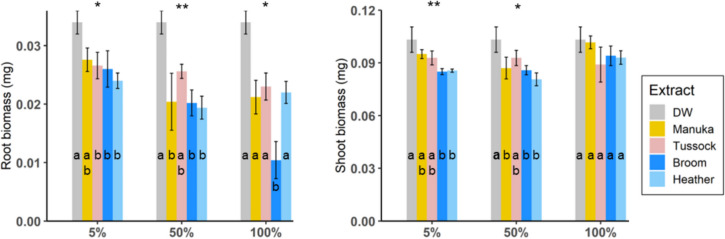

Root and shoot biomass were also compared between treatments as described (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S3). 0.1% and 1% concentration of extracts had no significant effect on biomass (Supplementary Table S4). 5% extracts significantly affected root biomass (LRT; X2 = 10.32, df = 4, P = 0.035) and shoot biomass (LRT; X2 = 14.53, df = 4, P = 0.006), with heather and broom extracts often having negative effects on biomass. Similarly, root biomass (LRT; X2 = 15.00, df = 4, P = 0.005) and shoot biomass (LRT; X2 = 10.94, df = 4, P = 0.027) differed significantly between seeds treated with 50% of extracts (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S3). Compared with deionised water, seeds treated with 50% manuka, broom and heather extracts had significantly lower biomass. Application of 100% extracts caused significant differences in root biomass (LRT; X2 = 11.50, df = 4, P = 0.022), with broom extracts significantly reducing biomass in comparison with the remaining treatments. Shoot biomass was not affected by the application of 100% extracts (LRT; X2 = 4.83, df = 4, P = 0.305).

Fig. 4.

Biomass of mānuka treated with different concentrations of broom, heather, mānuka and tussock aqueous root extracts, with deionised water as a control. Y-axis shows mean ± SE biomass, and x-axis represents applied concentrations. Series of contrasts between groups were performed using the relevel functions and asterisks and letters indicate significant differences (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001)

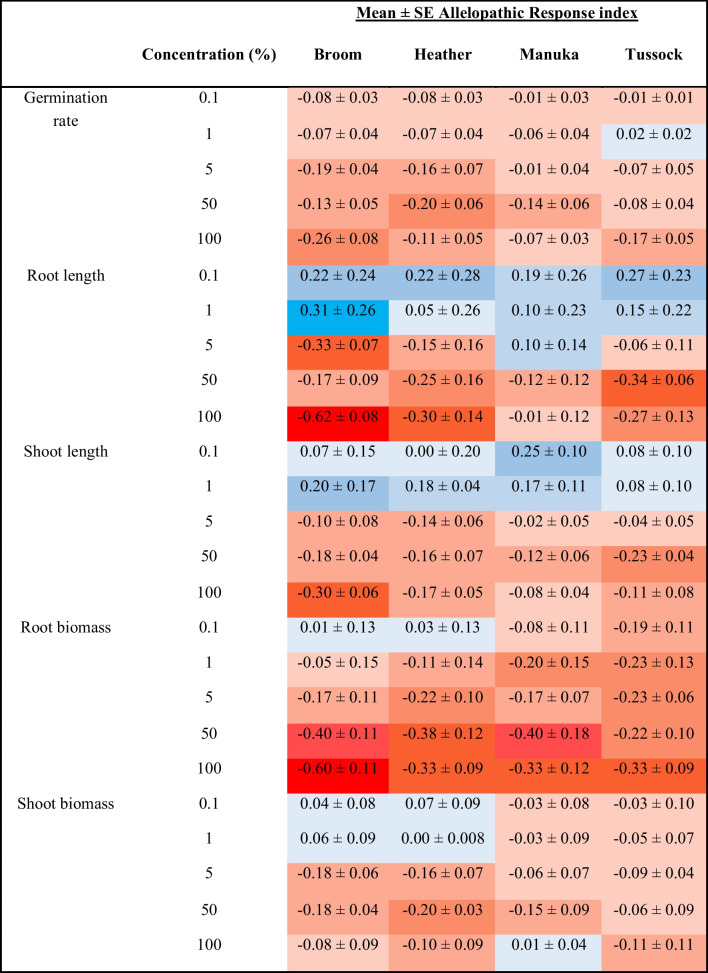

The allelopathy response index (Table 1) summarises the impact of root aqueous extracts of different species and concentrations on mānuka.

Table 1.

Allelopathic response index of aqueous root extracts on manuka. Deep red means the index is more than −0.5 (signalling strong inhibition), and deep blue means ≥ 3 (potential stimulatory effect)

Discussion

Allelopathy is one of the most studied phenomena in plant competition, and it has been explored in agricultural settings (Bhadoria 2010; Cheng and Cheng 2015) and biological invasions (Chengxu et al. 2011; Inderjit and Bhowmik 2002). The present study showed high variation in the chemical composition of invasive (heather and broom) and native (mānuka and tussock) root extracts, with polysaccharide 4-O-methylmannose and terpenoid (E)- pinocarveol being the dominant compounds in the broom and heather extracts, respectively.

Mannose-containing lectins are common in legumes, contributing to their low digestibility, and have been long known to mediate self vs non self-recognition, and plant–microbe interactions (Barre et al. 2019; Chrispeels and Raikhel 1991; Etzler 1985; Sequeira 1978). Lectins have been shown to inhibit seed germination by inducing changes in the mitotic state of plant cells (Nikitina et al. 2004). Therefore, it is plausible that 4-O-methylmannose is related to the observed allelopathic activity of broom. (E)- pinocarveol has also been previously associated with allelopathic effects in other species as reviewed in (Verdeguer et al. 2020). The phytotoxic action of terpenoids has been attributed to multiple mechanisms including interference with cellular processes such as mitosis and cellular respiration, membrane depolarization and ion leakage, and oxidative damage among others (Inderjit and Duke 2003; Mushtaq et al. 2020; Verdeguer et al. 2020). Therefore, these and other compounds would be good candidates for further exploration of their inhibition activities on native plants. It is also plausible that the interactive effects of compounds are important to the biological activity of these extracts, so exploration of compound blends is encouraged. We also suggest future studies to explore the exudate concentrations in the soil at different distances from the emitting plant.

We found differences between the activity of invasive species’ extracts and those of conspecific and other native plants, with invasive species extracts having stronger allelopathic effects and biological activity at lower concentrations. Lower concentrations (0.1% and 1%) of invasive plants root extracts had a significant impact on germination but not on seedling growth or biomass. In contrast, higher doses (≥ 5%) of heather and broom root extracts had strong adverse effects on seed germination, seedling length and biomass, while mānuka and tussock extracts often had weaker effects, generally at very high doses (50 and 100%) (as supported by the allelopathy response index in Table 1). However, broom displayed a stronger allelopathic effect than heather at the highest tested concentration (100%), highlighting differences in allelopathic potential between invasive species.

Our results generally support the novel weapons hypothesis, suggesting that native species are more vulnerable to the allelochemicals of plants they did not coevolve with. The observed effects for conspecific extracts at higher concentrations indicate potential autotoxicity as reported for other systems (Bonanomi et al. 2005; Inderjit and Duke 2003; Singh et al. 1999; Xiang et al. 2022). Autotoxicity is a form of negative intraspecific allelopathy, and it is likely to increase in the vicinity of the emitter plant (at higher concentrations) to reduce intra-competition, self-perpetuation, and regulate population density (Singh et al. 1999). The impact of the other native species (tussock) was very modest, although other plants in the Poaceae family are known to possess allelopathic properties (Favaretto et al. 2018; Sánchez-Moreiras et al. 2003; Tantiado and Saylo 2012).

The allelopathic activities of Ericaceae have been demonstrated in the past, with findings being consistent with this study. For instance, in laboratory assays, aqueous extracts of heather drastically inhibited root and hypocotyl growth of red clover, with less impact on germination (Ballester et al. 1982). Similarly, aqueous extract of young heather leaves prevented the germination of Scots pine, with the effect being more pronounced in seeds treated with higher concentrations of extract (Hille and Ouden 2005). Other studies have also documented the chemical constituents of heather extracts and their negative impact on intra- and interspecific competitors (Jalal and Read 1983; Jalal et al. 1982; Robinson 1972).

Broom is also known to suppress competitors using volatile and non-volatile allelochemicals (Pardo-Muras et al. 2019, 2018, 2020a, 2020b). For instance, broom-invaded soil suppressed Douglas-fir growth, with the effect inhibited by activated charcoal addition (Grove et al. 2012), while soil mixed with fresh flowering broom material significantly reduced the emergence and biomass of five weeds (Pardo-Muras et al. 2020b). Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) of broom also have herbicidal effects and have synergistic effects when combined with those of another invasive plant (Ulex europaeus, gorse) (Pardo-Muras et al. 2019).

Broom and heather VOCs can also disrupt ecological interactions among native species. For instance, previous studies conducted in New Zealand in connection with this work show that exposure to above-ground heather and broom VOCs resulted in reduced VOC emissions by mānuka, presumably affecting its ability to attract pollinators and natural enemies of their herbivores; while heather VOCs disrupted the attraction of the native mānuka beetle (Pyronota festiva) to its food plant (Effah et al. 2020b, 2022a). This evidence supports the role of VOCs in plant competition and invasion (Clavijo McCormick et al. 2023; Effah et al. 2019). However, further studies on invasive plant root volatiles would be useful in elucidating the allelopathic effects of below-ground VOCs.

Allelochemicals have direct effects on competing plants by interfering with various essential physiological processes such as cell division and respiration (Inderjit and Duke 2003; Mushtaq et al. 2020; Verdeguer et al. 2020). However, in nature, allelochemicals can also have indirect effects on neighbouring plants through alterations in soil properties and microbial populations (Blum 2006; Cipollini et al. 2012; Scavo et al. 2019; Weidenhamer and Callaway 2010). For example, Caustis blakei enhanced its nutrient acquisition by exuding carboxylate, which increased acid phosphatase activity levels (Playsted et al. 2006). Regarding microorganisms-mediated interactions, many studies have demonstrated antimicrobial activities of invasive plant allelochemicals, particularly on beneficial arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, impairing receiving plants’ competitiveness (Bainard et al. 2009; Kato-Noguchi 2021; Stinson et al. 2006; Zhu et al. 2020).

The allelochemicals of both heather and broom have antimicrobial properties. Heather-dominated soil contains many compounds, including nonanoic acid, which are toxic to fungi (Jalal and Read 1983). Another study investigating fungitoxic metabolites in heather also found its root exudates were toxic to certain mycorrhizal fungi (Robinson 1972). Similarly, under greenhouse conditions, Douglas-fir seedlings grown in broom-invaded soils had lower ectomycorrhizal fungi than those in uninvaded-forest soils (Grove et al. 2012). In a follow-up experiment where the impact of deforestation was considered, lower ectomycorrhizal fungi were again recorded in broom-invaded soils (Grove et al. 2017). Exploring the indirect effects of heather and broom root allelochemicals on native plants of the North Island Central Plateau of New Zealand, will be another step towards understanding the complex chemical ecology of these noxious weeds. Future studies could also explore the impacts of native species (mānuka and tussock) allelochemicals on invasive weeds.

Conclusion

This study explored the chemical composition of the root extracts of heather, broom, mānuka and tussock and investigated their effects on seed germination and seedling growth of mānuka. The results clearly distinguish between constituents of the four plants’ extracts with broom extracts being dominated by 4-O-methylmannose and heather extracts by (E)-pinocarveol. 16-kaurene and methyl palmitate were the most abundant compounds in mānuka and tussock root extracts respectively, and both compounds were present in high amounts in both native plants. This is the first time the chemical constituents of mānuka and tussock root extracts have been reported. The results showed a strong allelopathic effect of invasive species (heather and broom) extracts on germination, seedling length and biomass of a native plant (mānuka) at both low and high concentrations; with broom showing stronger effects than heather at the highest tested concentration (100%). In contrast, conspecific (mānuka) and other native’s (tussock) extracts only had effects at very high concentrations (50% and 100% v/v) and these were generally weaker than those of invasive plants. The results support the novel weapons hypothesis, suggesting that native plants are more vulnerable to the allelochemicals of plants they did not co-evolve with. We encourage further studies to elucidate the direct and indirect roles of below-ground volatile and non-volatile allelochemicals to further our understanding of invasive plants’ chemical ecology and to support their management.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

AA secured funding for the project. Both authors contributed to the study conception and experimental design. EE collected and analysed the data. Both authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded through a Marsden Fast Start Grant of the Royal Society of New Zealand - Te Apārangi - awarded to Andrea Clavijo McCormick for the project “Plant Communication in Times of Rapid Environmental Change”.

Data Availability

All relevant datasets are available upon request.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Amarasekare P (2002) Interference competition and species coexistence. Proc R Soc Lond B 269:2541–2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainard L, Brown P, Upadhyaya M (2009) Inhibitory effect of tall hedge mustard (Sisymbrium loeselii) allelochemicals on rangeland plants and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Weed Sci 57:386–393 [Google Scholar]

- Ballester A, Vieitez A, Vieitez E (1982) Allelopathic potential of Erica vagans, Calluna vulgaris, and Daboecia cantabrica. J Chem Ecol 8:851–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barre A, Bourne Y, Van Damme EJ, Rougé P (2019) Overview of the structure–function relationships of mannose-specific lectins from plants, algae and fungi. Int J Mol Sci 20:254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadoria P (2010) Allelopathy: a natural way towards weed management. Am J Exp Agric 1:7–20 [Google Scholar]

- Bil G, Kapferer E, Koch A, Sedmak C (2016) Between Māori and modern? The case of mānuka honey. In: Appreciating Local Knowledge. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, pp 61–76

- Blum U (2006) Allelopathy: a soil system perspective Allelopathy: a physiological process with ecological implications. Springer, Dordrecht:299–340

- Bonanomi G, Legg C, Mazzoleni S (2005) Autoinhibition of germination and seedling establishment by leachate of Calluna vulgaris leaves and litter. Community Ecol 6:203–208 [Google Scholar]

- Buddenhagen CE (2000) Broom Control Monitoring at Tongariro National Park. Department of Conservation Wellington, New Zealand,

- Callaway RM, Aschehoug ET (2000) Invasive plants versus their new and old neighbors: a mechanism for exotic invasion. Science 290:521–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway RM, Ridenour WM (2004) Novel weapons: invasive success and the evolution of increased competitive ability. Front Ecol Environ 2:436–443 [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DS et al (2016) Modelling the introduction and spread of non-native species: International trade and climate change drive ragweed invasion. Glob Change Biol 22:3067–3079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman HM, Bannister P (1990) The spread of heather, Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull, into indigenous plant communities of Tongariro National Park. New Zealand J Ecol 7–16

- Cheng F, Cheng Z (2015) Research progress on the use of plant allelopathy in agriculture and the physiological and ecological mechanisms of allelopathy. Front Plant Sci 6:1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengxu W, Mingxing Z, Xuhui C, Bo Q (2011) Review on allelopathy of exotic invasive plants. Procedia Engineering 18:240–246 [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels MJ, Raikhel NV (1991) Lectins, lectin genes, and their role in plant defense. Plant Cell 3:1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipollini D, Rigsby CM, Barto EK (2012) Microbes as targets and mediators of allelopathy in plants. J Chem Ecol 38:714–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavijo McCormick A, Effah E, Najar-Rodriguez AJ (2023) Ecological aspects of volatile organic compounds emitted by exotic invasive plants. Front Ecol Evol 11:1059125 [Google Scholar]

- Effah E, Holopainen JK, McCormick AC (2019) Potential roles of volatile organic compounds in plant competition. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst 38:58–63 [Google Scholar]

- Effah E, Barrett DP, Peterson PG, Potter MA, Holopainen JK, Clavijo McCormick A (2020a) Effects of two invasive weeds on arthropod community structure on the Central Plateau of New Zealand. Plants 9:919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effah E, Barrett DP, Peterson PG, Potter MA, Clavijo HJK, McCormick A (2020b) Seasonal and environmental variation in volatile emissions of the New Zealand native plant Leptospermum scoparium in weed-invaded and non-invaded sites. Sci Rep 10:11736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effah E, Svendsen L, Barrett DP, Clavijo McCormick A (2022a) Exploring plant volatile-mediated interactions between native and introduced plants and insects. Sci Rep 12:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effah E, Min Tun K, Rangiwananga N, Clavijo McCormick A (2022b) Mānuka clones differ in their volatile profiles: Potential implications for plant defence, pollinator attraction and bee products. Agronomy 12:169 [Google Scholar]

- Etzler ME (1985) Plant lectins: molecular and biological aspects. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 36:209–234 [Google Scholar]

- Favaretto A, Scheffer-Basso SM, Perez NB (2018) Allelopathy in Poaceae species present in Brazil. A Rev Agronomy Sustain Dev 38:1–12 [Google Scholar]

- Goel MK, Khanna P, Kishore J (2010) Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate International. J Ayurveda Res 1:274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove S, Haubensak KA, Parker IM (2012) Direct and indirect effects of allelopathy in the soil legacy of an exotic plant invasion. Plant Ecol 213:1869–1882 [Google Scholar]

- Grove S, Parker IM, Haubensak KA (2017) Do impacts of an invasive nitrogen-fixing shrub on Douglas-fir and its ectomycorrhizal mutualism change over time following invasion? J Ecol 105:1687–1697 [Google Scholar]

- Hille M, Den Ouden J (2005) Charcoal and activated carbon as adsorbate of phytotoxic compounds–a comparative study. Oikos 108:202–207 [Google Scholar]

- Inderjit, Bhowmik PC (2002) Allelochemicals phytotoxicity in explaining weed invasiveness and their function as herbicide analogues. In: Chemical ecology of plants: allelopathy in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Springer, Basel, pp 187–197

- Inderjit, Duke SO (2003) Ecophysiological aspects of allelopathy. Planta 217:529–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inderjit et al (2011) Volatile chemicals from leaf litter are associated with invasiveness of a neotropical weed in Asia. Ecology 92:316–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalal M, Read D (1983) The organic acid composition of Calluna heathland soil with special reference to phyto-and fungitoxicity: I. Isolation and identification of organic acids. Plant Soil 70:257–272 [Google Scholar]

- Jalal MA, Read DJ, Haslam E (1982) Phenolic composition and its seasonal variation in Calluna vulgaris. Phytochemistry 21:1397–1401 [Google Scholar]

- Kato-Noguchi H (2021) Allelopathy of knotweeds as invasive plants. Plants 11:3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesing VF (1995) Impacts of invasion on community structure: habitat and invertebrate assemblage responses to Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull invasion, in Tongariro National Park, New Zealand: a thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology at Massey University, Palmerston North. Massey University

- Lê S, Josse J, Husson F (2008) FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Softw 25:1–18 [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Jin Z (2010) Potential allelopathic effects of Mikania micrantha on the seed germination and seedling growth of Coix lacryma-jobi. Weed Biol Management 10:194–201 [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq W, Siddiqui MB, Hakeem KR (2020) Allelopathy. Springer [Google Scholar]

- Nikitina V, Bogomolova N, Ponomareva E, Sokolov O (2004) Effect of Azospirilla lectins on germination capacity of seeds. Biol Bull Russian Acad Sci 31:354–357 [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Muras M, Puig CG, López-Nogueira A, Cavaleiro C, Pedrol N (2018) On the bioherbicide potential of Ulex europaeus and Cytisus scoparius: Profiles of volatile organic compounds and their phytotoxic effects. PLoS ONE 13:e0205997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Muras M, Puig CG, Pedrol N (2019) Cytisus scoparius and Ulex europaeus produce volatile organic compounds with powerful synergistic herbicidal effects. Molecules 24:4539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Muras M, Puig CG, Souto XC, Pedrol N (2020a) Water-soluble phenolic acids and flavonoids involved in the bioherbicidal potential of Ulex europaeus and Cytisus scoparius. S Afr J Bot 133:201–211 [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Muras M, Puig CG, Souza-Alonso P, Pedrol N (2020b) The phytotoxic potential of the flowering foliage of gorse (Ulex europaeus) and scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius), as pre-emergent weed control in maize in a glasshouse Pot experiment. Plants 9:203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Cichello S (2013) Manuka honey: an emerging natural food with medicinal use. Nat Prod Bioprospect 3:121–128 [Google Scholar]

- Pearson BM, Minor MA, Robertson AW, Clavijo McCormick AL (2024) Plant invasion down under: exploring the below-ground impact of invasive plant species on soil properties and invertebrate communities in the Central Plateau of New Zealand. Biol Invasions 26:4215–4228 [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel D et al (2001) Economic and environmental threats of alien plant, animal, and microbe invasions. Agr Ecosyst Environ 84:1–20 [Google Scholar]

- Playsted CW, Johnston ME, Ramage CM, Edwards DG, Cawthray GR, Lambers H (2006) Functional significance of dauciform roots: exudation of carboxylates and acid phosphatase under phosphorus deficiency in Caustis blakei (Cyperaceae). New Phytol 170:491–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu T, Du X, Peng Y, Guo W, Zhao C, Losapio G (2021) Invasive species allelopathy decreases plant growth and soil microbial activity. PLoS ONE 16:e0246685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team R (2021) R: A language and environment for statistical computing

- Robinson R (1972) The production by roots of Calluna vulgaris of a factor inhibitory to growth of some mycorrhizal fungi. J Ecol 60:219–224 [Google Scholar]

- Romano A, Stevanato P (2020) Germination data analysis by time-to-event approaches. Plants 9:617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudrappa T, Bonsall J, Gallagher JL, Seliskar DM, Bais HP (2007) Root-secreted allelochemical in the noxious weed Phragmites australis deploys a reactive oxygen species response and microtubule assembly disruption to execute rhizotoxicity. J Chem Ecol 33:1898–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Moreiras A, Weiss O, Reigosa-Roger M (2003) Allelopathic evidence in the Poaceae. Bot Rev 69:300–319 [Google Scholar]

- Scavo A, Abbate C, Mauromicale G (2019) Plant allelochemicals: Agronomic, nutritional and ecological relevance in the soil system. Plant Soil 442:23–48 [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira L (1978) Lectins and their role in host-pathogen specificity. Annu Rev Phytopathol 16:453–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Batish DR, Kohli R (1999) Autotoxicity: concept, organisms, and ecological significance. Crit Rev Plant Sci 18:757–772 [Google Scholar]

- Stinson KA et al (2006) Invasive plant suppresses the growth of native tree seedlings by disrupting belowground mutualisms. PLoS Biol 4:e140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantiado RG, Saylo MC (2012) Allelopathic potential of selected grasses (family Poaceae) on the germination of lettuce seeds (Lactuca sativa). International J Biol Sci Biol Technol 4

- Therneau TM, Lumley T (2015) Package ‘survival’. R Top Doc 128: 28–33.Thorpe AS, Thelen GC, Diaconu A, Callaway RM (2009) Root exudate is allelopathic in invaded community but not in native community: field evidence for the novel weapons hypothesis. J Ecol 641–645

- Thorpe AS, Thelen GC, Diaconu A, Callaway RM (2009) Root exudate is allelopathic in invaded community but not in native community: field evidence for the novel weapons hypothesis. J Ecol 97:641–645 [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Wal R, Truscott AM, Pearce IS, Cole L, Harris MP, Wanless S (2008) Multiple anthropogenic changes cause biodiversity loss through plant invasion. Glob Change Biol 14:1428–1436 [Google Scholar]

- Van Kleunen M, Weber E, Fischer M (2010) A meta-analysis of trait differences between invasive and non-invasive plant species. Ecol Lett 13:235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdeguer M, Sánchez-Moreiras AM, Araniti F (2020) Phytotoxic effects and mechanism of action of essential oils and terpenoids. Plants 9:1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenhamer JD, Callaway RM (2010) Direct and indirect effects of invasive plants on soil chemistry and ecosystem function. J Chem Ecol 36:59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GB, Richardson D (1988) Bioassays for allelopathy: measuring treatment responses with independent controls. J Chem Ecol 14:181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang W, Chen J, Zhang F, Huang R, Li L (2022) Autotoxicity in Panax notoginseng of root exudates and their allelochemicals. Front Plant Sci 13:1020626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Li X, Xing F, Chen C, Huang G, Gao Y (2020) Interaction between root exudates of the poisonous plant Stellera chamaejasme L. and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the growth of Leymus Chinensis (Trin.) Tzvel. Microorganisms 8:364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant datasets are available upon request.