Abstract

Background

Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (SFRP1) inhibits Wnt signaling and is differentially expressed in human hair dermal papilla cells (DPCs). However, the specific effect of SFRP1 on cell function remains unclear. Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) representing telomerase activity was found highly active around the hair dermal papilla. TERT levels can be enhanced by activation of the Wnt pathway in cancer cells and embryonic stem cells. Whether this regulatory mechanism is still present in DPCs has not been studied so far.

Methods

In this study, DNA plasmids and siRNAs were constructed against the SFRP1 gene and transfected into DPCs cultured in vitro. We detected the viability, proliferation, and migration of DPCs by Calcein/PI fluorescence, CCK-8, trans-well, or cell scratch experiments, and the expression of potential target genes was also determined through quantitative detection of RNA and protein.

Results

The results demonstrate a significant difference in SFRP1 levels from the control group, suggesting successful transfection of the DNA plasmid and siRNA of SFRP1 into IDPCs. Also, SFRP1 regulates the cell proliferation capacity of IDPCs and reduces their migration functions. The DPCs' living activity, proliferation, and migration function exhibited a negative correlation with the level of SFRP1. SFPR1 also inhibits the protein or RNA expression of β-catenin and TERT in DPCs.

Conclusion

It was proven that in human DPCs, different levels of SFRP1 change how cells work and control Wnt/β-catenin signaling or telomerase activity. This means that blocking SFRP1 could become a new way to treat hair loss diseases in the future.

Keywords: Dermal papilla cell, Hair growth, Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (SFRP1), Telomerase, Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), Wnt/β-catenin

1. Introduction

Hair diseases are constantly evolving, and hair loss is one of the major anxious and discussed issues. The psychological impact of hair growth disorders can be severe. However, effective therapies to promote hair growth are currently limited, so finding new therapeutic targets and measures is necessary.

Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (SFRP1) belongs to the secretory glycoprotein SFRP family, and has been identified to be a physiologically important suppression of Wnt molecular activity [1,2]. The Wnt/β-catenin signal is considered one of the most critical and important signals that control hair follicle (HF) formation and proliferation [3]. The expression of SFRP1 was also detected in HFs, whose antagonists can effectively enhance ex vivo hair growth [4]. Hair dermal papilla cells (DPCs) are specialized fibroblasts that originate from dermal mesenchymal, which are reservoirs of pluripotent stem cells and various factors, and HFs signal primarily through DPCs [5,6]. In the previous study by our research team, we found that the SFRP1 level in DPCs in androgenetic alopecia (AGA) patients was significantly higher than in normal people [7]. As AGA is an important component of non-cicatricial alopecia, the increase in SFRP1 levels is consistent with the previous conclusion that SFRP1 may inhibit hair growth [8].

There is evidence that telomerase activity plays a significant role in the biology of HF [9]. As early as 1997, high telomerase activity was detected concentrated in the bulb area of the HF during the anagen phase, where DPCs are located [10]. The main component of telomerase is telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), which adds specific short repeating DNA sequences to the telomeres [11]. The TERT determinant controls the activity of telomerase, so quantification of TERT expression can be partly representative of telomerase activity [12]. Increasing TERT levels appears to be an effective way to promote hair growth, according to recent studies [13,14].

During the year 2012, the research team led by Hoffmeyer made a discovery and released a publication stating that the β-catenin protein forms a connection with the TERT promoter, thereby enhancing the expression and function of telomerase in mouse embryonic stem cells and human cancer cells [15]. However, this regulatory relationship has not been validated in human DPCs. Research on hair regrowth is critical, thus it is important to investigate whether the regulation of DPC development by the Wnt inhibitor SFRP1 is connected with changing TERT levels. This is something that should be investigated. SFRP1 is explored in this study for its effects on cell survival, proliferation, and migration, as well as its impacts on Wnt signal and TERT levels in DPCs. Specifically, the study focuses on the development of DPCs.

2. Material and methods

2.1. DPC culture and IDPC construction

Hair follicles were extracted from the occipital scalp of a male AGA patient who underwent hair transplantation surgery at the Department of Dermatology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University has approved this process (Approved No. 2019-SRFA-149).

The residue around the hair follicles was trimmed, and the primary DPCs were isolated by 0.2 % collagenase and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 20 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1 % Penicillin-streptomycin. The immortalized DPCs (IDPCs) were constructed by the Newgainbio company, which provided the technology to transfect primary DPCs with simian virus 40T (SV40T) antigen by lentivirus to become IDPCs. DMEM with 10 % FBS and 1 % Penicillin-streptomycin was used to culture IDPCs at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 environment. According to the literature, SV40T-transformed IDPCs can proliferate and maintain the trait up to around passage 25 [16]. As a result, 10–15 generations of IDPCs were used in our experiment. Furthermore, all IDPCs were stained with ALP to ensure their hair-induced cellular properties because ALP activity is a critical indicator of human DPC trichogenic inductivity.

2.2. SFRP1 plasmids and small interfering RNA (siRNA)

Through EcoRI and NotI sites, the amplified gene of interest fragment is cloned onto the overexpression vector pcDNA3.1. The overexpression plasmids of pcDNA3.1-SFRP1 and pcDNA3.1-NC were purchased from Corues Biotechnology. High- performance liquid chromatography was used to synthesize and purify double-stranded siRNAs for the SFRP1 target gene (Gene Pharma). Sequences are listed as Table 1.

Table 1.

Synthesis sequences were used for SFRP1 and negative control.

| Name | Sence | Antisense |

|---|---|---|

| SFRP1 | 5′-GAGAUGCUUAAGUGUGACATT-3′ | 5′-UGUCACACUUAAGCAUCUCTT -3′ |

| Negative control mRNAs | 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ | 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′ |

2.3. Cell transfection

IDPCs in 6-well plates or other types of plates were transfected with SFRP1 plasmid and siRNA using Lipofectamine™ 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). The operation was carried out following the manufacturer's protocol. All transfections were performed 24 h after cell seeding, with a cell density of 70–90 %. The incubated IDPCs were then collected, and the cell transfection efficiency was analyzed from the mRNA and protein levels by PCR and Western blot test.

2.4. Calcein/PI cell viability assay

IDPCs were seeded at a density of 10 × 104 cells/well on six-well plates and set in an incubator for 24 h before SFRP1 plasmid and siRNA transfection. After 48 h of transfection, a cell dead-and-die staining assay was performed using a Calcein/PI Cell Viability Assay Kit (C2015S, Beyotome) to assess the viability of IDPCs in different intervention groups. Image J software was used to quantify fluorescence images taken with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus). Finally, a percentage of live cells (green) versus dead cells (red) was used to represent cell viability as: cell viability (%) = number of live cells/(number of live cells + number of dead cells) × 100 [17].

2.5. Cell counting kit-8 assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 4000 cells/well in 96-well plates. A cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8, C0038, Beyotime) was used following the instructions provided by the merchant. From the completion of transfection, add 10 μl of CCK-8 to 100 μl of medium in the wells every 24 h and continue incubating for 3 h, testing the optical density (OD) at 450 nm with a microplate reader (Multiskan FC). Cell proliferative viability (%) = [(As-Ab)/(Ac-Ab)] × 100, As: absorbance in the experimental group, Ab: absorbance in the blank group, Ac: absorbance in the control group [18].

2.6. Trans-well assay

The cell trans-well assay is one of the methods used to assess the migration capacity of IDPCs. After 24 h of cell serum starvation, IDPCs underwent digestion and washing, and were resuspended to a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml. 200 μl cell suspension (2 × 104 cells) were seeded into the upper chamber of the 24-well trans-well polycarbonate membrane cell culture inserted with an 8 μm pore size (Corning). 600 μl DMEM containing 15 % FBS were added to the lower chamber and allowed IDPCs to migrate in the incubator for 24 h. 4 % paraformaldehyde was used to fix the cells for 30 min, then Crystal Violet Staining Solution (C0121, Beyotime) was used to stain them, and the non-migrated cells were removed using cotton swabs. Migrated IDPCs were observed and photographed under the microscope (Olympus-CKX53). Image J software was used for specific count analysis.

2.7. Cell scratch assay

The scratch assay is another experiment that measures the ability of cell migration. IDPCs were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. 48 h after transfection, serum was removed from the medium, and the plates were scratched with the tip of a 200 μl-sterile pipette. The scratched area was photographed under the microscope (Olympus-CKX53) and analyzed with Image J software, and the width of the area was measured at 0, 12, and 24 h after scratching. Cell migration rate is calculated by the following formula: Migration rate (%) = (initial scratch blank area - scratch area at the time point)/initial scratch blank area × 100.

2.8. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

FastPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit V2 (Vazyme) was used following the manufacturer's instructions to extract RNA from IDPCs 48 h after transfection. RNA concentration was determined by a microUV spectrophotometer (Nano-drop). A total of 1000 ng of RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the HiScript® II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR kit (R222, Vazyme), and the final volume is 100 μl. The sequences of the primers are shown in Table 2, all purchased from GenScript. qPCR was performed using the 2 × SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix kit (Bimake) in a final reaction volume of 20 μl following the instruction [19,20].

Table 2.

Primer sequences for qPCR.

| Gene | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| SFRP1 | GCCCGAGATGCTTAAGTGTG | ACAGAGATGTTCAATGATGGCC |

| β-catenin | TGTACGAGCACATCAGGACA | GGAATGGTATTGAGTCCTCGG |

| TERT | GTGCTACGGCGACATGGAGAAC | GTTGAAGGTGAGACTGGCTCTGATG |

| GAPDH | TCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGT | sTGAAGGGGTCATTGATGGCA |

2.9. Western blot assay

A lysis buffer containing 0.1 mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; keyGENE BioTECH) was used to lyse IDPCs on ice 72 h after transfection. By collecting the lysate, centrifuging and removing the pellet, the protein concentration was determined separately using the BCA protein assay kit (P0012, Beyotime). Bicolor SDS-PAGE Sample Loading Buffer (1 × ) (P0296, Beyotime) was added to the protein and heated at 95 °C for 5 min to denature. The extracted proteins were isolated using a 10 % sodium dodecyl sulfate PAGE (SDS-PAGE) gel, followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were soaked in QuickBlock™ Western blocking buffer (P0252, Beyotime) for 50 min, then washed three times with a TBS-T buffer, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against β-actin (Servicebio), SFRP1 (Abcam), β-catenin (Cell Signaling Technology) and TERT (Abcam). The next day, membranes were washed with TBST again 3 times and treated with goat anti-rabbit IgG (Proteintech) for at least 1 h. Reactive proteins were visualized by Ultrasensitive ECL Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Biosharp). Gel imaging system (ChemiDoc XRS+, Bio-Rad) was used for observation and photographing, and the images were analyzed by image J software [21,22].

2.10. Statistical analysis

The experiment was repeated at least in triplicate. Data were analyzed by Graphpad prism 8.0 software and were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Specific data analysis was performed by an unpaired t-test and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

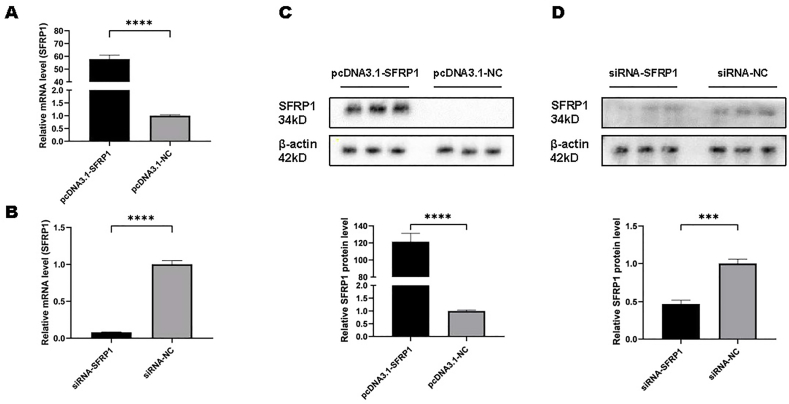

3.1. SFRP1 plasmids and siRNA were successfully transfected to IDPCs

IDPCs were collected 48 h and 72 h after cell transfection, then mRNA and protein levels were measured respectively. Among them, the levels of SFRP1 were significantly different from the control group in both mRNA (Fig. 1A and B) and protein (Fig. 1C and D) expression, indicating that the DNA plasmid and siRNA of SFRP1 were successfully transfected into IDPCs.

Fig. 1.

Expression levels of SFRP1 mRNA and protein in IDPCs after transfection of SFRP1-specific DNA plasmids and siRNAs compared with the corresponding negative control. (A) mRNA level of SFRP1 after pcDNA3.1-SFRP1 transfection; (B) mRNA level of SFRP1 after siRNA-SFRP1 transfection; (C) protein level of SFRP1 after pcDNA3.1-SFRP1 transfection; (D) protein level of SFRP1 after siRNA-SFRP1 transfection. ∗∗∗∗P<0.0001, ∗∗∗P<0.001.

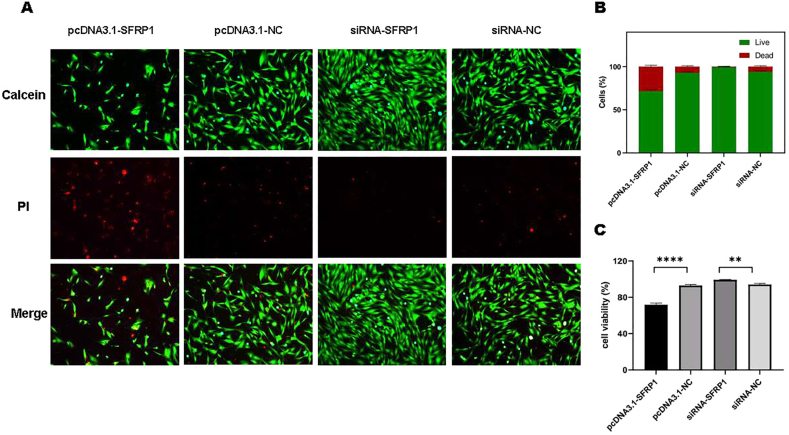

3.2. SFRP1 regulates the viability of IDPCs

Calcein/PI staining is used as an assay for live or dead IDPCs. As shown in the fluorescence images (Fig. 2A) and associated statistical charts (Fig. 2B and C), compared with the respective control groups, SFRP1 overexpression reduced cell viability and increased cell death significantly. While after inhibiting SFRP1 expression by siRNA, IDPCs’ survival rate increased. It can be concluded that the expression level of SFRP1 can regulate the cell activity and viability of IDPCs.

Fig. 2.

IDPCs' cell viability assay presented by Calcein/PI staining. (A) Fluorescence images show that cells are live (green) or dead (red); (B) Comparison chart of live/dead IDPCs; (C) Cell viability (proportion of live cells) count plot. ∗∗∗∗P<0.0001, ∗∗P<0.01.

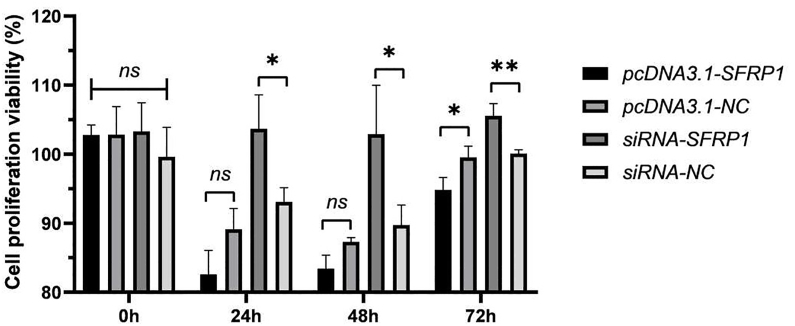

3.3. SFRP1 regulates the proliferation of IDPCs

The cell proliferation effects of IDPCs at different time points (0, 24, 48, 72 h after transfection) were tested by CCK-8 assay. Fig. 3 shows that there was no difference in cell proliferation activity between the groups of IDPCs at the time of transfection. At 72 h after transfection, the results of the CCK8 assay of IDPCs overexpressing SFRP1 by plasmids were significantly reduced compared with the control group, namely the cell proliferation ability was reduced. Conversely, the proliferation capacity of IDPCs that inhibit SFRP1 by siRNA was significantly enhanced from 24 h after transfection. Overall, SFRP1 regulates the cell proliferation capacity of IDPCs.

Fig. 3.

The proliferative ability of IDPCs was determined by CCK-8 assay. ns: no significance, ∗P<0.05, ∗∗P<0.01.

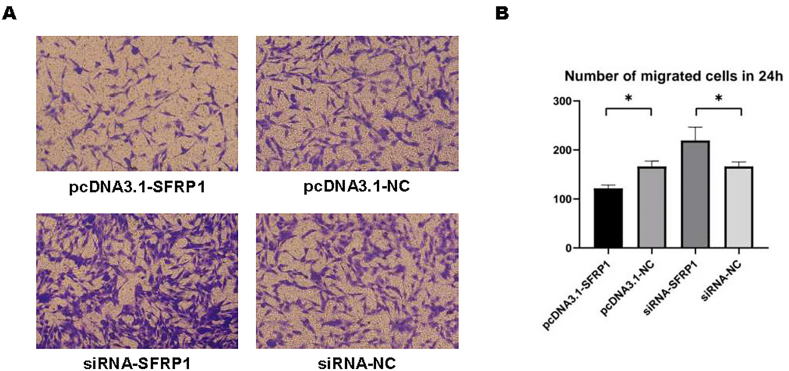

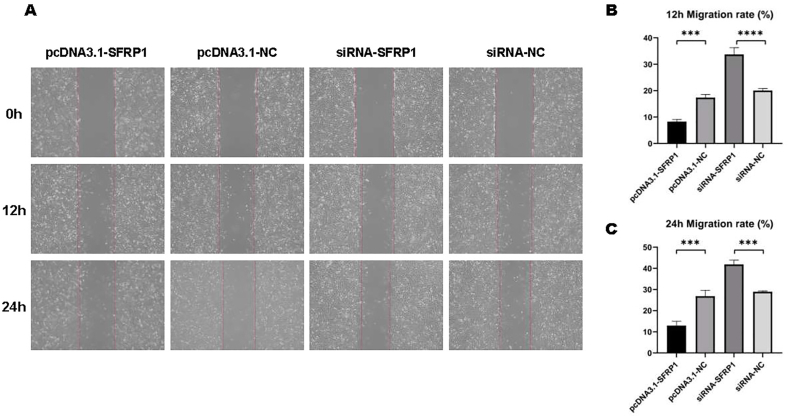

3.4. SFRP1 regulates the migration of IDPCs

48 h after transfection, we measured the migration capacity of IDPCs by trans-well and cell scratch assay. As shown in Fig. 4, the trans-well experiment determined the number of migrated IDPCs within 24 h, and this number in the SFRP1 overexpression group was lower than that of the control group. However, the value was significantly higher after inhibiting SFRP1 expression compared with whose control. The results of the cell scratch assay are the same. At both 12 h (Fig. 5A and B) and 24 h (Fig. 5A–C) time points, the migration rate of IDPCs can be seen with corresponding changes. Both experiments confirmed that SFRP1 reduces the migration function of IDPCs, and inhibition of SFRP1 helps to improve cell migration.

Fig. 4.

Trans-well migration of IDPCs. (A) The migrated IDPCs were stained by crystal violet and presented under the microscope; (B) Counting and analysis of migrating cells within 24 h. ∗P<0.05.

Fig. 5.

The migration capacity of IDPCs analyzed by cell scratch experiment. (A) Microscopic images of the migration of IPDCs towards the center of the scratch at 0, 12, 24 h; Cell migration rate obtained by scratch area difference analysis at (B) 12 h and (C) 24 h. ∗∗∗P<0.001, ∗∗∗∗P<0.0001.

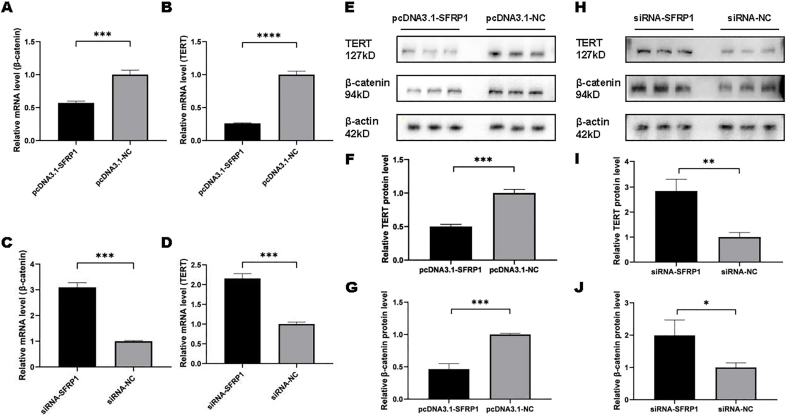

3.5. SFRP1 negatively affects β-catenin and TERT expressions in IDPCs

To explore whether SFRP1 affects β-catenin and TERT expression, the mRNA and protein levels of β-catenin and TERT in IDPCs were determined after transient transfection. As a result, SFRP1 overexpression significantly reduced mRNA β-catenin (Fig. 6A) and TERT (Fig. 6B) compared to the negative control group. However, when SFRP1 was specifically inhibited, the mRNA expression of β-catenin (Fig. 6C) and TERT (Fig. 6D) in IDPCs was significantly increased. Trends in detection results at the protein level were consistent with mRNA results (Fig. 6E–J). In addition, the corresponding SFRP1 levels can be found in Fig. 1. These data further confirm that SFRP1 negatively regulates the expression of β-catenin and TERT levels in IDPCs, and inhibition of SFRP1 can reverse this result.

Fig. 6.

Expression levels of β-catenin and TERT mRNA and protein after transfection of SFRP1-specific DNA plasmids and siRNAs compared with the corresponding negative control. (A) mRNA level of β-catenin after pcDNA3.1-SFRP1 transfection; (B) mRNA level of TERT after pcDNA3.1-SFRP1 transfection; (C) mRNA level of β-catenin after siRNA-SFRP1 transfection; (D) mRNA level of TERT after siRNA-SFRP1 transfection; (E, F, G) protein levels of β-catenin and TERT after pcDNA3.1-SFRP1 transfection; (H, I, J) protein levels of β-catenin and TERT after siRNA-SFRP1 transfection. ∗P<0.05, ∗∗P<0.01, ∗∗∗P<0.001, ∗∗∗∗P<0.0001.

4. Discussion

Today, regenerative medicine and therapy as well as drug novel therapy has attracted the attention of scientist in different disease [23,24]. SFRP1 is a gene belonging to the secreted glycoprotein SFRP family found on chromosome 8p11.21 [25]. It has been established that SFRP1 is a negative regulator of the Wnt pathway and plays a tumor-suppressive role [25]. Wnt can induce cell response by regulating cell activity, proliferation, migration, differentiation, and other aspects mainly of cancer cells [26,27]. Furthermore, hair growth is also facilitated by Wnt signaling in DPCs [28].

In this study, although the hair follicles and DPCs originated from a patient with AGA, they were taken from the occipital scalp anagen hair, which was considered normal hair rather than pathological. We used SV40T-transformed human IDPCs, which have been shown to fully retain primary DPC properties and maintain passage morphology [16]. ALP expression is a biomarker of DPC, whose activity is closely related with the HF induction performance and hair growth promotion ability of DPCs [29]. The IDPCs used in our experiments were ALP-active (Supplementary Material 1), further indicating that they all retained their follicle inducing properties. Changes in indicators based on initial levels are also scientifically significant. The activity and proliferation of DPCs determine their growth rate and mitotic index, and their effects can indicate hair growth promotion or inhibition [30]. Previously, our team's research has confirmed that SFRP1 is present in human DPCs and its expression is significantly elevated in AGA patients [7]. Through a series of molecular experiments, we confirmed the negative regulation effect of SFRP1 on the survival viability, proliferation, and migration of DPCs after transient transfection of plasmids. These cell properties were all enhanced reversely by siRNA targeted inhibition of SFRP1, which means that the decrease of SFRP1 in human DPCs showed better ability to promote cell viability, proliferation, and migration.

β-catenin is the core component of the Wnt pathway, and its level is generally used to quantify the activity of the Wnt pathway [31]. The levels of β-catenin in DPCs were found to be negatively correlated with the expression of SFRP1 in this experiment. Combined with the results of the previous experiments on the function of DPCs, the corresponding changes in the level of β-catenin are also consistent with the revealed induced regulation of Wnt signaling on some cancer cell function, indicating that this conclusion is also applicable in DPCs [26]. As the hair dermal papilla is universally acknowledged as the signaling guide center for HF growth and proliferation, it is not difficult to show that the SFRP1 expressed in it has a strong correlation with hair growth by regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling [32].

HF aging is thought to be one of the causes of hair loss. Telomerase high activity was initially discovered in the bulb region at the base of the human HF, where the dermal papilla is located [10]. Our previous literature review revealed that positive regulation of telomerase or TERT levels helps to combat HF aging and promote hair regeneration [33]. However, at present, there are relatively few studies on the expression and role of telomerase in HFs, and further molecular studies on upstream regulation of telomerase are very scarce. As previously stated, the conclusion that the β-catenin protein positively regulates telomerase activity in mouse intestinal tumor models and human cancer cells has been confirmed [15]. Then, starting from the newly discovered Wnt regulator SFRP1 in hair dermal papilla, our results found that SFRP1 has not only a negative regulatory effect on β-catenin protein, but also a negative regulatory relationship with the expression level of TERT. This will further confirm that in human DPCs, there is a high probability of the negative regulatory axis of 'SFRP1-Wnt/β-catenin signaling-TERT', which is likely to be an important link in the hair growth process and hair diseases such as AGA. The improvement of the DPCs’ living viability, proliferation, and migration ability in experiments after the inhibition of SFRP1, namely the activation of the Wnt pathway, may also be related to the increase of TERT levels and the improvement of cell anti-aging ability. But in any case, the specific molecular mechanism of how telomerase regulates anti-aging and regeneration of DPCs is also worthy of further research and verification.

Since we have previously confirmed that the expression of SFRP1 in the hair papilla of people with AGA is significantly increased [7], combined with the results of this experimental analysis, it is not difficult to believe that if such alopecia patients can be treated according to SFRP1 targeting, there may be a chance to fight HF aging and reverse hair loss, which will be a clinically significant novel treatment plan.

5. Conclusion

SFRP1 was found higher in human hair papilla in AGA patients than in the normal population. Through IDPCs cultured in vitro, we found that after differential expression of SFRP1, the living viability, proliferation, and migration functions of cells, as well as the levels of Wnt pathway core protein β-catenin and telomerase core protein TERT, all showed corresponding negative changes. Thus, the negative role of SFRP1 in the growth of DPCs was revealed, and it was believed that reduction of SFRP1 could improve the various functions of human DPCs, activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, increase TERT expression or telomerase activity, play a role in anti-aging of HFs, and promote hair growth. In short, inhibition of the molecular target SFRP1, is expected to become a new therapeutic direction for reversing hair loss represented by AGA.

Author contributions

Chaofan Wang: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, software, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. Yimei Du: Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, writing-review & editing. Changpei Lu: Investigation, software, visualization, writing-review & editing. Lingbo Bi: Methodology, software, visualization, writing-review & editing. Yunbu Ding: Formal analysis, methodology, writing-review & editing. Weixin Fan: Conceptualization, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing - review & editing.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Approved No. 2019-SRFA-149). We declared that the study was based on the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association.

Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

Funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Jiangsu Province Hospital Core Facility Center for providing the experimental platform, Peking Union Medical College Library for providing the literature search platform, and all the researchers who made contributions to this study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reth.2024.12.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Pehlivan M., Caliskan C., Yuce Z., Sercan H.O. sFRP1 expression regulates Wnt signaling in chronic myeloid leukemia K562 cells. Anti Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2022;22:1354–1362. doi: 10.2174/1871520621666210524162145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang P., Wei K., Chang C., Zhao J., Zhang R., Xu L., et al. SFRP1 negatively modulates pyroptosis of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis: a review. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.903475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J., Zhao B., Dai Y., Zhang X., Chen Y., Wu X. Exosomes derived from dermal papilla cells mediate hair follicle stem cell proliferation through the Wnt3a/β-catenin signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/9042345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkshaw N.J., Hardman J.A., Haslam I.S., Shahmalak A., Gilhar A., Lim X., et al. Identifying novel strategies for treating human hair loss disorders: cyclosporine A suppresses the Wnt inhibitor, SFRP1, in the dermal papilla of human scalp hair follicles. PLoS Biol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y., Guerrero-Juarez C.F., Xiao F., Shettigar N.U., Ramos R., Kuan C.H., et al. Hedgehog signaling reprograms hair follicle niche fibroblasts to a hyper-activated state. Dev Cell. 2022;57:1758–1775.e1757. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2022.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu K., Han Q., Ma Z., Yan Q., Pei Y., Shi P., et al. Injectable platelet rich fibrin facilitates hair follicle regeneration by promoting human dermal papilla cell proliferation, migration, and trichogenic inductivity. Exp Cell Res. 2021;409 doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2021.112888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou L.B., Cao Q., Ding Q., Sun W.L., Li Z.Y., Zhao M., et al. Transcription factor FOXC1 positively regulates SFRP1 expression in androgenetic alopecia. Exp Cell Res. 2021;404 doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2021.112618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alessandrini A., Bruni F., Piraccini B.M., Starace M. Common causes of hair loss - clinical manifestations, trichoscopy and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:629–640. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone R.C., Aviv A., Paus R. Telomere dynamics and telomerase in the biology of hair follicles and their stem cells as a model for aging research. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramirez R.D., Wright W.E., Shay J.W., Taylor R.S. Telomerase activity concentrates in the mitotically active segments of human hair follicles. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:113–117. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dratwa M., Wysoczańska B., Łacina P., Kubik T., Bogunia-Kubik K. TERT-regulation and roles in cancer formation. Front Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.589929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun D., Li X., Nie S., Liu J., Wang S. Disorders of cancer metabolism: the therapeutic potential of cannabinoids. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;157 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan X., Larsson C., Xu D. Mechanisms underlying the activation of TERT transcription and telomerase activity in human cancer: old actors and new players. Oncogene. 2019;38:6172–6183. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0872-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogawa M., Udono M., Teruya K., Uehara N., Katakura Y. Exosomes derived from fisetin-treated keratinocytes mediate hair growth promotion. Nutrients. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/nu13062087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmeyer K., Raggioli A., Rudloff S., Anton R., Hierholzer A., Del Valle I., et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates telomerase in stem cells and cancer cells. Science. 2012;336:1549–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.1218370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwack M.H., Yang J.M., Won G.H., Kim M.K., Kim J.C., Sung Y.K. Establishment and characterization of five immortalized human scalp dermal papilla cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang C., Xie N., Sun T., Ma W., Zhang B., Li W. Xanthohumol inhibits TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts activation via mediating PTEN/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:5431–5439. doi: 10.2147/dddt.S282206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai L., Qin X., Xu Z., Song Y., Jiang H., Wu Y., et al. Comparison of cytotoxicity evaluation of anticancer drugs between real-time cell analysis and CCK-8 method. ACS Omega. 2019;4:12036–12042. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b01142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farahzadi R., Fathi E., Mesbah-Namin S.A., Vietor I. Granulocyte differentiation of rat bone marrow resident C-kit(+) hematopoietic stem cells induced by mesenchymal stem cells could be considered as new option in cell-based therapy. Regen Ther. 2023;23:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2023.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee R.-Y., Koo J.-Y., Kim N.-I., Kim S.-S., Nam J.-H., Choi Y.-D. Usefulness of the human papillomavirus DNA chip test as a complementary method for cervical cytology. CytoJournal. 2023;20 doi: 10.25259/Cytojournal_40_2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng F., Wu J., Chi Q., Wang S., Liu W., Yang L., et al. Lactylome analysis unveils lactylation-dependent mechanisms of stemness remodeling in the liver cancer stem cells. Adv Sci. 2024;11 doi: 10.1002/advs.202405975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu G., Ding J., Yang N., Ge L., Chen N., Zhang X., et al. Evaluating the pro-survival potential of apoptotic bodies derived from 2D-and 3D-cultured adipose stem cells in ischaemic flaps. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:333. doi: 10.1186/s12951-024-02533-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyu Z., Xin M., Oyston D.R., Xue T., Kang H., Wang X., et al. Cause and consequence of heterogeneity in human mesenchymal stem cells: challenges in clinical application. Pathol Res Pract. 2024;260 doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2024.155354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma X., Cheng H., Hou J., Jia Z., Wu G., Lü X., et al. Detection of breast cancer based on novel porous silicon Bragg reflector surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy-active structure. Chin Opt Lett. 2020;18 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baharudin R., Tieng F.Y.F., Lee L.H., Ab Mutalib N.S. Epigenetics of SFRP1: the dual roles in human cancers. Cancers. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/cancers12020445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayat R., Manzoor M., Hussain A. Wnt signaling pathway: a comprehensive review. Cell Biol Int. 2022;46:863–877. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashrafizadeh M., Dai J., Torabian P., Nabavi N., Aref A.R., Aljabali A.A.A., et al. Circular RNAs in EMT-driven metastasis regulation: modulation of cancer cell plasticity, tumorigenesis and therapy resistance. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81:214. doi: 10.1007/s00018-024-05236-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gentile P., Garcovich S. Advances in regenerative stem cell therapy in androgenic alopecia and hair loss: Wnt pathway, growth-factor, and mesenchymal stem cell signaling impact analysis on cell growth and hair follicle development. Cells. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/cells8050466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F., Liu H., Wu X., Song Z., Tang H., Gong M., et al. Tetrathiomolybdate decreases the expression of alkaline phosphatase in dermal papilla cells by increasing mitochondrial ROS production. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24 doi: 10.3390/ijms24043123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madaan A., Verma R., Singh A.T., Jaggi M. Review of Hair Follicle Dermal Papilla cells as in vitro screening model for hair growth. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:429–450. doi: 10.1111/ics.12489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z., Li Z., Ji H. Direct targeting of β-catenin in the Wnt signaling pathway: current progress and perspectives. Med Res Rev. 2021;41:2109–2129. doi: 10.1002/med.21787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houschyar K.S., Borrelli M.R., Tapking C., Popp D., Puladi B., Ooms M., et al. Molecular mechanisms of hair growth and regeneration: current understanding and novel paradigms. Dermatology. 2020;236:271–280. doi: 10.1159/000506155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C., Bi L., Du Y., Lu C., Zhao M., Lin X., et al. The role of telomerase in hair growth and relevant disorders: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22:2925–2929. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.