Abstract

To determine relationships between Helicobacter pylori geographical origin and type II methylase activity, we examined 122 strains from various locations around the world for methylase expression. Most geographic regions possessed at least one strain resistant to digestion by each of 14 restriction endonucleases studied. Across all of the strains studied, the average number of active methylases was 8.2 ± 1.9 with no significant variation between the major geographic regions. Although seven pairs of isolates showed the same susceptibility patterns, their cagA/vacA status differed, and the remaining 108 strains each possessed unique patterns of susceptibility. From a single clonal group, 15 of 18 strains showed identical patterns of resistance, but diverged with respect to M.MboII activity. All of the methylases studied were present in all major human population groupings, suggesting that their horizontal acquisition pre-dated the separation of these populations. For the hpyV and hpyAIV restriction-modification systems, an in-depth analysis of genotype, indicating extensive diversity of cassette size and chromosomal locations regardless of the susceptibility phenotype, points toward substantial strain-specific selection involving these loci.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori are Gram-negative curved bacteria that persistently colonize the gastric mucosa of the majority of the world’s population. The presence of H.pylori leads to chronic inflammation, which increases risk for gastric and duodenal ulcers, gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric lymphoma (1,2).

Analysis of genomic sequences of H.pylori strains 26695 and J99 has identified 25 (3,4) and 28 (5) genes likely to encode DNA methyltransferases (methylases), respectively. The specificities of 11 active methylases identified in strain 26695 are consistent with frequent methylation of the H.pylori genome at both adenine and cytosine residues (4). Helicobacter pylori strain-specific methylases have been identified (6,7), often, but not always, associated with strain-specific restriction endonucleases (REs). Such strain-specificity can result from mutation, truncation or absence of methylase genes; analysis of the sequenced genomes provides evidence for all three phenomena (3,5,8,9).

DNA methylation is involved in important cellular processes, including host-specific defence mechanisms (10), DNA mismatch repair (11), regulation of gene transcription (12,13), DNA transposition (14) and initiation of chromosomal replication (15). Helicobacter pylori strains possess a significantly greater number of active methylases than REs (4,8), suggesting that the methylases might fulfill other functions. For example, induction of transcription of iceA by H.pylori–host cell contact enhances expression of the downstream methylase, hpyIM (16). iceA exists as two distinct genotypes, iceA1, which demonstrates strong homology to an RE (nlaIIIR in Neisseria lactamica), and iceA2; only iceA1 RNA is induced following adherence in vitro. The presence of iceA2, an open-reading frame (ORF) with no homology to known REs, directly upstream of hpyIM, is associated with reduced and differentially expressed hpyIM activity compared with iceA1 strains (17), suggesting that differential methylase regulation might be involved in bacterium–host interactions.

Helicobacter pylori strains from different geographic origins vary in their genotypes (18–21). Since particular cagA, babA and vacA genotypes are associated with specific clinical outcomes (22–27), their host backgrounds may be important. Examining geographic characteristics of specific genes increases both our understanding of their evolution and of H.pylori co-evolution with humans (28). hpyIIIM, a methylase recognizing the sequence GATC (29), shows geographic character, as does iceA1, an RE that is always adjacent to hpyIM (30), indicating that further characterization of H.pylori methylase activity in relation to geographic origins may be warranted.

To determine whether H.pylori geographical origins and the prevalence of particular type II methylases are related, we examined 122 strains from various locations of the world for methylase expression, and performed a more in-depth analysis of genotype for two representative enzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

In this study, 122 H.pylori isolates from North America (n = 22), South America (n = 27), Europe (n = 28), Africa (n = 3) and the Asia-Pacific region (n = 42) were examined (Table 1). All strains were obtained from a stock collection of H.pylori isolates from the NYU Helicobacter/Campylobacter strain reference center and stored at –70°C in our laboratory. Eighteen isolates from The Netherlands were obtained from eight members of an extended family, consisting of a father (subject 1), mother (subject 2) and six adult daughters (subjects 3–8) (31). Antral mucosal biopsies had been obtained from each patient by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and multiple single H.pylori colonies were then stored at –70°C, as described (20,32). After thawing, all H.pylori strains were grown on trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood (BBL, Cockeysville, MD) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 48 h.

Table 1. Sources of the 122 H.pylori strains studied and their cagA and vacA status.

| Geographic region | Country | N | Number (%) cagA+ | Number (%) of specified vacA genotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1a | s1b | s1c | s2 | m1 | m2a | m2b | ||||

| Asia-Pacific | China | 15 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Japan | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Korea | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maori | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Thailand | 7 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | |

| Bangladesh | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sub-total | 42 | 36 (86) | 4 (10) | 1 (3) | 37 (88) | 0 | 29 (69) | 9 (24) | 4 (10) | |

| North America | Inuit | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mexico | 10 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 0 | |

| USA | 10a | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Sub-total | 22 | 9 (41) | 2 (9) | 13 (59) | 0 | 7 (32) | 12 (55) | 9 (41) | 1 (5) | |

| South America | Argentina | 10 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Columbia | 7 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | |

| Peru | 10 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 0 | |

| Sub-total | 27 | 16 (59) | 1 (4) | 20 (74) | 0 | 6 (22) | 18 (67) | 9 (33) | 0 | |

| Europe | Belgium | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Finland | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Italy | 12 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 0 | |

| The Netherlands | 10 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 0 | |

| UK | 1b | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sub-total | 28 | 17 (61) | 16 (57) | 4 (14) | 0 | 8 (29) | 12 (43) | 15 (54) | 0 | |

| Africa | Eritrea | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Morocco | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Zaire | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Sub-total | 3 | 2 (67) | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 2 (67) | 0 | 3 (100) | 0 | |

| Total | 122 | 80 (66) | 23 (19) | 39 (32) | 37 (30) | 23 (19) | 72 (59) | 45(37) | 5 (4) | |

DNA methods

Chromosomal DNA from H.pylori was prepared using a phenol extraction method (33) and was subjected to digestion by the following REs: MboI (HpyAIII), MboII (HpyAII), HinfI (HpyAIV), HpaII, DdeI (HpyAVIB), FokI, HaeIII, TaqI (HpyV), Hpy99I, HpyCH4III, HpyCHIV, HpyCHV, Hpy188I and NlaIII (HpyAI). These enzymes had been selected because resistance to digestion for each had been previously identified in at least one H.pylori strain (4,6–8). To determine susceptibility to digestion, 1 µg of DNA was digested with 5 U of the specified RE for 2 h in 10 µl of buffer as recommended by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). DNA samples at concentrations >200 ng/µl were used and the final 10 µl volume was reached by addition of distilled water. For all strains, chromosomal DNA that was identically treated, but without endonuclease added was used as a negative control. Chromosomal DNA from cells of Escherichia coli DH5α or Campylobacter jejuni strain 11168 was used to assess the activity of each enzyme at least once for each preparation of the DNA samples. Digestion products were electrophoresed at 120 V for 2 h in 0.7 or 1.0% agarose gels containing 0.5 µg of ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light. For samples in which results were unclear, the DNA was re-purified and digestion repeated at least once. The genotyping of strains based on vacA s- and m-region alleles and the presence of the cytotoxin-associated gene (cagA) were determined by line probe assays (34). Portions of cagA, as well as portions of the s- and m-regions of vacA, were amplified with biotin-labeled PCR primers and the products were subsequently analyzed by a single-step reverse hybridization line probe assay of reference sequences, as described (34). PCR was generally carried out in 50-µl volumes containing 100 ng of template DNA, 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (Qiagen) and 0.5 µmol of each primer (Table 2). Cycling conditions were usually 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 45°C for 1 min and 72°C for a period dependent on the expected product size (1 min per kb).

Table 2. Helicobacter pylori oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

| Primer designation | Gene designation | Nucleotide positiona | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26695 | J99 | |||

| HP0259Fb | HP0260 | JHP0244 | –63 to –43 | ATTTTGAGCGTGGATAGGGTG |

| HP0260F | HP0260 | JHP0244 | +62 to +83 | TGAAATCGTGTTTTGATACCCC |

| HP0260R | HP0260 | JHP0244 | +1114 to +1135 | CATGGAAGCTTTGGAGTGTTTG |

| HP0261R | HP0261 | JHP0245 | +48 to +66 | GAACAAGAGCTTATCAATC |

| HP0262R | HP0261 | JHP0245 | +653 to +674 | CGCGTAAAAAACCTGCAAAAAC |

| HpyIVAF1 | HP1351 | JHP1270 | –132 to –111 | GCCCATTCATTCACTCATTTTG |

| HpyIVAR1 | HP1352 | JHP1271 | +1307 to +1328 | GCTCTAAAGTAAGCCCCATTTC |

| HpyIVAF2 | HP1352 | JHP1271 | +5 to +26 | GTCCCTTTGGCAGATATAACGC |

| HpyIVAR2 | HP1352 | JHP1271 | +898 to +918 | AAGGCGTTGAGGATCATTGGG |

| HpyIVAF3 | HP1350 | JHP1269 | +61 to +81 | TTCACCACCATGCAAACTCAC |

| HpyIVAR3 | HP1352 | JHP1271 | –280 to –259 | TGCCTAATCTCGCTCTCATTTG |

aLocation refers to position in relation to ORF in strain 26695. – or +, position upstream or downstream of first nucleotide of the translation initiation codon.

bF, forward; R, reverse.

Analysis of HpyV and HpyAIV restriction-modification (R-M) systems

The ORFs and flanking regions of the HpyV and HpyAIV R-M systems were examined in detail in strains J99 and 26695, using the TIGR database (www.tigr.org) and NCBI BLAST searches for mapping and alignment. Using the GCG program REPEAT, the target regions containing these R-M systems were assessed for the presence of repeats, and the level of similarity between the repeats was determined using GCG GAP. The G+C content of the HpyAIV R-M was determined using GCG COMPOSITION. Primers were selected in regions within the ORF of the methylases as well as in regions flanking the repeats. PCR was performed to determine the characteristics of the R-M system in both susceptible and resistant strains.

Sequence analyses

PCR products were purified using a Qiagen Gel Extraction kit (Valencia, CA) and sequenced at the New York University Medical Center core sequencing facility. All sequences were analyzed using SEQUENCHER 3.1.1 and aligned using GCG PILEUP and PRETTY.

Mathematical calculation

For N strains, digested with j endonucleases, the probability of finding exactly k matching pairs was calculated as follows:

PN(k) = (![]() * CN2 * CN – 22 *...* C2N – 2k + 2 *

* CN2 * CN – 22 *...* C2N – 2k + 2 * ![]() ) /2jN

) /2jN

where Cab is the combination of a susceptibilities taken b at a time, and Pab is the permutation of a susceptibilities taken b at a time.

The correlation coefficients of all possible pairs of enzymes (except for NlaIII, for which the correlation coefficients were undefined due to resistance in all tested strains), were calculated to assess the relationships between the activities of the individual methyltransferases.

RESULTS

Background genotypes of the studied H.pylori strains

To characterize the population of strains studied, we examined their cagA and vacA status, since these are both polymorphic, well studied, and linked to virulence differences (27,28). To determine cagA and vacA status, line probe assays were performed on all 122 strains studied (Table 1). In the Asia-Pacific region, 86% of strains were cagA+ while in other regions, 53% were cagA+, a difference that is consistent with previous reports (18,35). In the Asia-Pacific region, most isolates were vacA s1c, in South America s1b, and in Europe s1a, as expected for these populations (18). The distribution of m1 and m2 types was more balanced in the various regions, also as expected (18). Thus, the strains studied may be considered to be broadly representative of those colonizing diverse human populations.

DNA modification status in H.pylori strains from different regions

To assess diversity in DNA methylation among H.pylori, all 122 strains were digested with the 14 specified REs (Table 3); susceptibility indicates lack of methylation involving the RE recognition site, whereas resistance indicates the presence of an active methylase with an identical or highly similar recognition sequence. The resistance to digestion by these REs was broad, ranging from 100% (NlaIII) to 2% (FokI) (Table 3). Most geographic regions possessed at least one strain resistant to digestion by a given endonuclease, with the exception of Africa (n = 3). FokI resistance was observed in only one strain from Japan and in one from the USA (Table 3). One strain from a New Zealand Maori was resistant to 13 of the 14 REs examined, while a strain from Korea was resistant to only three, demonstrating the wide range of modification status present in H.pylori among the REs tested. Nevertheless, across all of the strains studied, the average number of active methylases (defined by the number of REs to which a given strain was resistant) was 8.2 ± 1.9 (mean ± SD), and there was no significant variation between the major geographic regions (Table 3). However, the mean number of active methylases was significantly higher among the strains from the relatively isolated Asian-Pacific Maori (10.8 ± 4.2) and North American Inuit (9.7 ± 3.0) populations than in the other populations (7.9 ± 3.7) (P < 0.01, Mann–Whitney U-test). Although seven pairs of the isolates showed the same susceptibility patterns, their cagA/vacA status differed, indicating that they had different genetic backgrounds. The probability of finding seven matching pairs of patterns in a set of 122 strains digested with 13 REs was determined to be a minimum of P122(7) = 2.09 × 10–5, assuming equal probabilities of susceptibility and digestion (NlaIII was excluded from this calculation since all strains were resistant to its digestion). The remaining 108 strains each possessed unique patterns of susceptibility to digestion by these 14 REs. There was no consistent relationship between cagA/vacA status and resistance to digestion, and there was no significant correlation between the activities of individual methyltransferases (maximum correlation coefficient = 0.21; data not shown).

Table 3. Resistance of 122 H.pylori strains to digestion by 14 REs, by geographic origin of the strain.

| H.pylori methyltransferase | RE examined | Percent of strains resistant to the specified RE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia-Pacific (n = 42) | North America (n = 22) | South America (n = 27) | Europe (n = 28) | Africa (n = 3) | Total (n = 122) | ||

| M.HpyAI | NlaIII | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| M.HpyAIII | MboI | 95 | 100 | 100 | 96 | 100 | 98 |

| M.HpyAII | MboII | 55 | 36 | 63 | 57 | 33 | 53 |

| M.HpyAIV | HinfI | 64 | 45 | 44 | 61 | 33 | 55 |

| M.HpyVIII | HpaII | 76 | 68 | 67 | 54 | 67 | 67 |

| M.HpyAVIB | DdeI | 60 | 36 | 22 | 57 | 0 | 45 |

| M.Hpy178VI | FokI | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| M.Hpy178VI | TaqI | 90 | 91 | 93 | 71 | 67 | 86 |

| M.HpyV | HaeIII | 43 | 32 | 48 | 29 | 0 | 38 |

| M.HpyCH4III | HpyCH4III | 50 | 73 | 30 | 50 | 100 | 51 |

| M.HpyCH4IV | HpyCHIV | 76 | 77 | 81 | 61 | 67 | 74 |

| M.HpyCH4V | HpyCH4V | 64 | 82 | 70 | 75 | 67 | 71 |

| M.Hpy188I | Hpy188I | 21 | 23 | 22 | 14 | 67 | 21 |

| M.Hpy99I | Hpy99I | 57 | 73 | 67 | 57 | 67 | 62 |

| Number of resistances | Mean ± SD | 8.4 ± 1.9 | 8.3 ± 2.1 | 8.0 ± 1.6 | 8.0 ± 1.8 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | 8.2 ± 1.9 |

| Range | 3–13 | 4–12 | 4–11 | 4–12 | 7–9 | 3–13 | |

DNA modification status in H.pylori strains from the same family

To assess the conservation of methylase activity among closely related strains, we next examined the modification status of the 18 isolates from a single Dutch family. Both random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and PCR-RFLP patterns from all 18 strains were nearly identical, indicating a similar origin (31). Ten strains from unrelated persons in The Netherlands (Table 1) were used as controls to assess the background distribution of susceptibility to RE digestion in the community. All 18 isolates from the family showed identical patterns of resistance except for three, which were digested by MboII (data not shown). Several colonies had been isolated from the mother (subject 2), one of which was resistant to MboII digestion (2a) and another that was susceptible (2b). Similar results were obtained for subjects 4 and 6 who possessed both MboII-resistant (4b, 6a and 6b) and MboII-sensitive strains (4a and 6c). The HpyII R-M system is an isoschizomer of the Moraxella bovis R-M system, MboII (6,32). Direct repeats flanking the R-M system allow for its deletion from the chromosome (32). PCR analysis of MboII-susceptible strains 2b, 4a and 6c using primers specific to hpyIIM identified a full-length gene in 4a but only an empty site product in strains 2b or 6c (data not shown). These results indicate that clonally related isolates can differ in methylase phenotype and genotype. The complement of active methylases in each strain is easily distinguishable from that of 10 control Dutch isolates (data not shown).

hpyVM and hpyAIVM genotypes

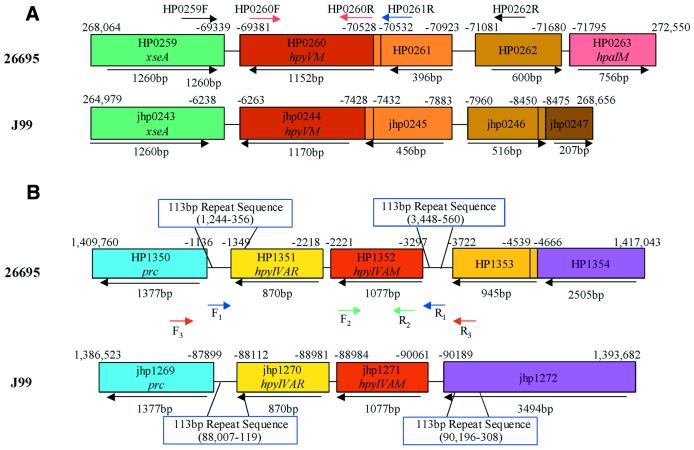

To examine whether the observed variability of methylase activity is related to differences in genotype, PCR was performed using primers for genes related to the hpyV- and hpyAIV-specific methylases, which are active in 86 and 55% of strains studied, respectively (Table 3). Both hpyVM and hpyAIVM nucleotide sequences are highly conserved in strains J99 and 26695 (Fig. 1). Flanking the hpyAIVRM system in both strains are 113 bp direct repeats; within 26695 and J99, the repeats have 96.4 and 95.8% identity, respectively. Between the two strains, the repeats upstream of the hpyAIVRM cassette are 93.8% identical and repeats downstream of the cassette are 92.9% identical. Analysis of the 500 bp sequences flanking the hpyVM/HP0261 (JHP0245) cassette identified no repeats >12 bp.

Figure 1.

Schematic of hpyVM (A), hpyAIVM (B) and flanking genes in H.pylori strains 26695 and J99. Corresponding colors indicate homology of ORFs between strains. PCR primers are indicated with colored arrows. Numbers above boxes indicate nucleotide positions in the genomic sequences, arrows and numbers below the boxes indicate size of the ORF (in bp) and direction of transcription.

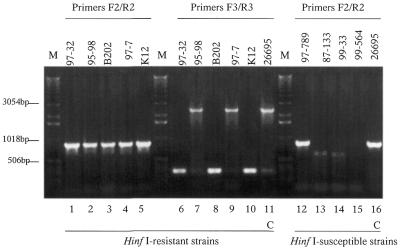

PCR analysis of 10 TaqI-resistant strains using primers within the methylase gene yielded products consistent with the expected hpyVM (1156 bp) size for all strains (Table 4). In contrast, PCR performed with primers that flank hpyVM and its adjacent ORF (HP0261/JHP0245) yielded products of larger than, or smaller than the expected size, and for three strains no product was amplified. In control strains 26695 and J99, the PCRs amplified all of the expected products (data not shown). PCR analysis of 16 TaqI-susceptible strains using primers within hpyVM yielded products of the expected size (n = 7), that were truncated (n = 3) or yielded no products (n = 6). Using primers that flank the two-ORF (HP0260/HP0261) cassette in 26695, either expected size or no products were observed. In total, of the 26 strains examined, eight different combinations of genotype and phenotype were observed (Table 4). For all 10 HinfI-resistant strains examined, PCR using primers specific for hpyAIVM amplified products of the expected size (Fig. 2). However, for these same strains, primers flanking the hpyAIVRM repeats amplified expected size, truncated or no products (Table 4). PCR analysis of 55 HinfI-susceptible strains using hpyAIVM-specific primers identified 21 expected size, two larger and seven truncated products; for 25 other strains no product was amplified. PCR using primers that flank the hpyAIVRM repeats on these 55 HinfI-sensitive strains yielded products consistent with the presence of a full R-M system from 12 strains, no product from nine strains, and truncated products (consistent with an ‘empty site’ product resulting from the deletion of the hpyAIVRM system and one copy of the 113 bp repeat) from 34 strains (Fig. 2). These latter products were identical in size to the four truncated products amplified from HinfI-resistant strains. Sequence analysis of the truncated PCR products from four strains showed that, as expected, each contained only a single copy of the repeat flanked by the sequences that surround the HpyAIV R-M system in strain 26695 (data not shown). In the PCR analyses, there were five strains for HpyV and four strains for HpyAIV that showed ‘no’ methylase product and ‘expected’ R-M product (Table 4). This result may be due to a small deletion or mutation affecting one of the primer sites for the methylase gene PCR.

Table 4. Heterogeneity of PCR products related to the H.pylori hpyV and hpyIVA R-M systems, according to strain phenotype.

| Phenotypic susceptibility to RE | No. of strains examined | Methylase product | Number of strains by size of RM productb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sizea | Number of strains | Expected | Truncatedc | None | ||

| TaqI (R.HpyV)-resistant | 10 | Expected | 10 | 4d | 3e | 3 |

| -susceptible | 16 | Expected | 7 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

| Truncated | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||

| None | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | ||

| HinfI (R.HpyIVA)-resistant | 10 | Expected | 10 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| -susceptible | 55 | Larger | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Expected | 21 | 7 | 11 | 3 | ||

| Truncated | 7 | 0 | 4 | 3 | ||

| None | 25 | 4 | 18 | 3 | ||

aUsing primers HP0260/HP0261 for hpyVM, expected = 1156 bp; using primers F2/R2 for hpyAIVM, expected = 914 bp.

bUsing primers HP0259/HP0262 for hpyVRM region, expected = 1889 bp; using primers F3/R3 for hinfIRM, expected = 2524 bp.

cUsing primers F3/R3 for the hpyAIVRM system, all 38 truncated products are ∼200 bp, which is the size of the ‘empty site’ product.

dFor strain 60190, which has known R.TaqI (R.HpyV) activity, the product is the expected 2.1 kb.

eUsing primers HP0259F and HP0262R for the hpyVRM system, all three truncated products are ∼250 bp, which is the size of the ‘empty site’ product.

Figure 2.

PCR products for H.pylori strains that are HinfI-resistant (lanes 1–11) or -susceptible (lanes 12–15). Primers: HpyIVA F2 and R2 (lanes 1–5 and 12–16), HpyIVA F3 and R3 (lanes 6–11). M, molecular weight marker.

Southern hybridizations

To determine the reliability of the PCR findings in which phenotype and genotype appeared to be highly variable, Southern hybridizations were performed using hpyVM or hpyAIVM probes with 10 representative H.pylori strains, including strains 26695 and J99 as controls. As expected, strains 26695 and J99, which are both resistant to TaqI and HinfI digestion and from which PCR products of the expected size had been amplified, showed the expected hybridizing fragments for hpyAIVM and hpyVM (Table 5). That hpyVM in strain 96-27 and hpyAIVM in strain 97-32 were identified by Southern hybridization but not by PCR primers flanking the putative R-M loci indicates either different chromosomal locations for these R-M systems in these strains or a small mutation in one of the PCR priming sites. From TaqI-susceptible strain 00-205, PCR products were consistent with the presence of a complete hpyVM/HP0261 (JHP045) cassette in the usual location, and Southern hybridization confirmed its presence. Parallel observations were made for the hpyAIVRM in strain 97-701 (Table 5).

Table 5. Southern hybridization analysis of H.pylori hpyV and hpyIVA R-M systems.

| H.pylori methyltransferase | RE | Strain designation | Genotype (PCR) | Phenotypec | Southern hybridizationd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-Ma | Mb | |||||

| hpyV | TaqI | 26695 | +e | +f | R | + |

| J99 | + | + | R | + | ||

| 96-27 | Truncatedf | + | R | + | ||

| 00-205 | + | + | S | + | ||

| 00-336 | None | None | S | – | ||

| 00-165 | None | Truncated | S | – | ||

| hpyIVA | HinfI | 26695 | + | + | R | + |

| J99 | + | + | R | + | ||

| 97-701 | + | + | S | + | ||

| 99-33 | No | Truncated | S | – | ||

| 97-789 | + | + | R | + | ||

| 97-32 | Empty | + | R | + | ||

aBased on primers HP0259F/HP0262R for hpyV; F3/R3 for hpyAIVRM.

bBased on primers HP0260/HP0261 for hpyVM; F2/R2 for hpyAIVM.

cPhenotype refers to resistance (R) or susceptibility (S) to digestion of chromosomal DNA by the indicated RE.

dProbe is the PCR product amplified by primers HP0260/HP0260R for hpyVM (1074 bp) and primers F2/R2 for hpyAIVM (914 bp). +, hybridizing fragment of the specified size; –, no fragment was identified.

e+, expected size (1889 bp for hpyVRM and 2524 bp for hpyAIVRM).

fThe truncated product was ∼400 bp.

g+, expected size (1156 bp for hpyVM and 914 bp for hpyAIVM).

DISCUSSION

Helicobacter pylori strains possess a large number of methylase genes (3–5,8,9), many of which are strain-specific (6,36). Our survey of H.pylori strains from around the world confirms that many of these methylases are active, and that strains differ substantially in their number and identity. hpyIM was the only methylase whose activity was present among all strains, suggesting strong selection for this phenotype. Its universality, despite the absence or inactivity of its cognate endonuclease [R.HpyI (iceA1)] from the great majority of strains (16,30), suggests that its function may extend beyond host defense, a hypothesis supported by its differential transcription among isolates (17). The presence of M.HpyIII activity in 97% of the strains we studied, despite the much lower prevalence of an active R.HpyIII (4,29) suggests a parallel function for this methylase as well. Interestingly, the recognition sequence of M.HpyIII, GATC, is identical to those for the dam-enzyme with important regulatory and virulence functions in Enterobacteriaceae (37).

Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of methylases of closely related strains shows that diversification can occur within individual hosts, through multiple mechanisms (32). Our analysis of the hpyAIVRM and hpyVM loci show that absence of methylase activity may be due to mutations in, truncation, or deletion of the methylase gene or of the entire RM cassette. The genetic diversity of H.pylori (5,36,38,39), which are naturally competent organisms (40–44), results from repeated horizontal gene transfers (45) and a high level of point mutation (39,46). That nearly every H.pylori strain possesses a different complement of active methylases (considering only the 14 we studied), indicates differing donor DNA susceptibilities to RE-digestion during inter-strain transfer. During co-colonization of a single individual by multiple H.pylori strains, diversity in R-M systems might prevent one strain from completely subverting the genome of another strain through recombination (7), while still allowing for gene transfer to a more limited extent.

Deamination of methylcytosines is responsible for G:C→A:T transitions (47), suggesting that cytosine methylation may provide a substrate for the increased mutation rates observed in H.pylori (46). Our analyses of the hpyAIVRM and hpyVM loci of closely related Dutch strains are consistent with prior reports (5,32,48) showing that H.pylori may regulate methylase function in a population of cells by mutation. The direct repeats flanking the hinfAIVRM cassette parallel those reported for other H.pylori R-M systems (32,48,49) and are consistent with the hypothesis that H.pylori R-M systems may be horizontally acquired from other H.pylori cells by transformation (32). In some strains the methylase genes are present at chromosomal loci that differ from the sequenced strains, suggesting either their independent acquisition or intrachromosomal rearrangement; this observation also supports the hypothesis that RM gene complexes are mobile genetic elements (50).

Each of the methylases studied was present in all major human population groupings (with the exception of Africa from which we had a very small sample size), suggesting that their horizontal acquisition pre-dated the separation of these populations and that they have been part of the H.pylori gene pool for at least 30 000 years. The presence of seven pairs of strains which showed the same methyltransferase pattern, an event with a minimum probability of 2.09 × 10–5, and the fact that all of the pairs had different different cagA/vacA genotypes also support the hypothesis that the acquisition of the methylases by H.pylori pre-dated the diversification of the cagA/vacA genotypes which are thought to have emerged after human migrations (1). Another possibility is that relatively clonal H.pylori strains have been spread by horizontal transmission between humans, perhaps along trade routes between distant human populations long before these 122 samples were collected. The significantly higher number of active methylases in the isolated Asian-Pacific Maori and North American Inuit strains suggests either selection for methylase activity in these smaller, more homogeneous populations, or merely reflects founder effects stemming from population bottlenecks. Despite substantial interstrain variation in the number of active methylases (Tables 3 and 4), that in each geographic region the mean number of activities present was relatively constant is a striking finding. This observation is consistent with the hypothesis that individual H.pylori strains are a part of a dynamic panmictic population (45,51) that is actively exchanging genes and alleles, and that exists in an equilibrium with its human hosts (28,52). Individual strains substantially vary in both the number and identity of the active methylases they possess, but the populations of strains sampled in each region are relatively constant in the average total numbers of methylases present (Table 4) indicating strong selection for these values. Whether the methylases facilitate further horizontal gene transfer, or intragenomic regulatory functions, or both, remains to be determined.

Helicobacter pylori genetic diversity enables distinguishing strains from one another. Of 122 strains studied, all were distinguishable by their complement of the 14-methylase activities and their cagA/vacA status. Current typing techniques such as RFLP, RAPD and sequencing are often time consuming and costly, and isolates may need to be studied simultaneously so that technical differences do not obscure results, inhibiting comparison of strains from different labs. The use of RE-digestion as a typing method is both rapid and inexpensive. Loss or inactivation of particular methylases may occur, even among highly related strains, indicating that such a typing system would not be completely stable, but may offer a first approximation of relatedness.

In conclusion, our studies demonstrate the wide presence of numerous methylase activities among H.pylori strains. Their ubiquity, wide range in numbers/strains, high level of diversity, and multiple mechanisms of regulation suggest that these enzymes play an important role in H.pylori biology, possibility though their effects on genetic diversity.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Yasuaki Harasaki for the mathematical calculations. Supported in part by NIH (R01GM62370) and by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Japan Clinical Pathology Foundation for International Exchange, and Yoshida Scholarship Foundation (to T.T.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Covacci A., Telford,J.L., Del Giudice,G., Parsonnet,J. and Rappuoli,R. (1999) Helicobacter pylori virulence and genetic geography. Science, 284, 1328–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peek R.M. and Blaser,M.J. (2002) Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nature Rev. Cancer, 2, 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomb J.F., White,O., Kerlavage,A.R., Clayton,R.A., Sutton,G.G., Fleischmann,R.D., Ketchum,K.A., Klenk,H.P., Gill,S., Dougherty,B.A., Nelson,K., Quackenbush,J., Zhou,L., Kirkness,E.F., Peterson,S., Loftus,B., Richardson,D., Dodson,R., Khalak,H.G., Glodek,A., McKenney,K., Fitzegerald,L.M., Lee,N., Adams,M.D. and Venter,J.C. (1997) The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature, 388, 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitkute J., Stankevicius,K., Tamulaitiene,G., Maneliene,Z., Timinskas,A., Berg,D.E. and Janulaitis,A. (2001) Specificities of eleven different DNA methyltransferases of Helicobacter pylori strain 26695. J. Bacteriol., 183, 443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alm R.A., Ling,L.S., Moir,D.T., King,B.L., Brown,E.D., Doig,P.C., Smith,D.R., Noonan,B., Guild,B.C., deJonge,B.L., Carmel,G., Tummino,P.J., Caruso,A., Uria-Nickelsen,M., Mills,D.M., Ives,C., Gibson,R., Merberg,D., Mills,S.D., Jiang,Q., Taylor,D.E., Vovis,G.F. and Trust,T.J. (1999) Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature, 397, 176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Q., Morgan,R. Roberts,R. and Blaser,M.J. (2000) Identification of type II restriction and modification systems in Helicobacter pylori reveals their substantial diversity among strains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 9671–9676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ando T., Xu,Q., Torres,M., Kusugami,K., Israel,D.A. and Blaser,M.J. (2000) Restriction-modification system differences in Helicobacter pylori are a barrier to interstrains plasmid transfer. Mol. Microbiol., 37, 1052–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin L., Posfai,J., Roberts,R.J. and Kong,H. (2001) Comparative genomics of the restriction-modification systems in Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 2740–2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong H., Lin,L.F., Porter,N., Stickel,S., Byrd,D., Posfai,J. and Roberts,R.J. (2000) Functional analysis of putative restriction-modification system genes in the Helicobacter pylori J99 genome. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3216–3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson G.G. (1991) Organization of restriction-modification systems. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 2539–2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modrich P. (1989) Methyl-directed DNA mismatch repair. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 6579–6600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barras F. and Marinus,M.G. (1989) The great GATC:DNA methylation in E. coli. Trends Genet., 5, 138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Woude M., Hale,W.B. and Low,D.A. (1998) Formation of DNA methylation patterns: nonmethylated GATC sequences in gut and pap operons. J. Bacteriol., 180, 5913–5920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts D., Hoopes,B.C., McClure,W.R. and Kleckner,N. (1985) IS10 transposition is regulated by DNA adenine methylation. Cell, 43, 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messer W. and Noyer-Weidner,M. (1988) Timing and targeting: the biological function of Dam methylation in E. coli. Cell, 54, 735–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peek R.M. Jr, Thompson,S.A., Donahue,J.P., Tham,K.T., Atherton,J.C., Blaser,M.J. and Miller,G.C. (1998) Adherence to gastric epithelial cells induces expression of a Helicobacter pylori gene, iceA, that is associated with clinical outcome. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians, 110, 531–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Q. and Blaser,M.J. (2001) Promoters of the CATG-specific methyltransferase gene hpyIM differ between iceA1 and iceA2 Helicobacter pylori strains. J. Bacteriol., 183, 3875–3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Doorn L.J., Figueiredo,C., Megraud,F., Pena,S., Midolo,P., Queiroz,D.M., Carneiro,F., Vanderborght,B., Pegado,M.D., Sanna,R., De Boer,W., Schneeberger,P.M., Correa,P., Ng,E.K., Atherton,J., Blaser,M.J. and Quint,W.G. (1999) Geographic distribution of vacA allelic types of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology, 116, 823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Doorn L.J., Figueiredo,C., Sanna,R., Blaser,M.J., and Quint,W.G. (1999) Distinct variants of Helicobacter pylori cagA are associated with vacA subtypes. J. Clin. Microbiol., 37, 2306–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ando T., Peek,R.M., Pride,D., Levine,S.M., Takata,T., Lee,Y.-C., Kusugami,K., van der Ende,A., Kuipers,E.J., Kusters,J.G. and Blaser,M.J. (2002) Polymorphisms of Helicobacter pylori HP0638 reflect geographic origin and correlate with cagA status. J. Clin. Microbiol., 40, 239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pride D.T., Meinersmann,R.J. and Blaser,M.J. (2001) Allelic variation within Helicobacter pylori babA and babB. Infect. Immun., 69, 1160–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaser M.J., Perez-Perez,G.I., Kleanthons,M. and Cover,T.L. (1995) Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing CagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adnocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res., 55, 2111–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cover T.L., Glupczynski,Y., Lage,A.P., Barette,A., Tummuru,M.K., Perez-Perez,G.I. and Blaser,M.J. (1995) Serologic detection of infection with CagA Helicobacter strains. J. Clin. Microbiol., 33, 1496–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuipers E.J., Perez-Perez,G.I., Meuwissen,S.G. and Blaser,M.J. (1995) Helicobacter pylori and atrophic gastritis: importance of CagA status. J. Natl Cancer Inst., 87, 1777–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiang Z., Bugnoli,M., Ponzetto,A., Mogrando,A., Figura,N., Covacci,A., Petracca,R., Pennatini,C., Censini,S., Armellini,D. and Rappuoli,R. (1993) Detection in an enzyme immunoassay of an immune response to a recombinant fragment of the 128 kDa (CagA) of Helicobacter pylori. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., 12, 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerhard M., Lehn,N., Neumayer,N., Boren,T., Rad,R., Schepp,W., Miehlke,S., Classen,M. and Prinz,C. (1999) Clinical relevance of the Helicobacter pylori gene for blood-group antigen-binding adhesin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 12778–12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atherton J.C., Peek,R.M.,Jr, Tham,K.T., Cover,T.L. and Blaser,M.J. (1997) Clinical and pathological importance of heterogeneity in vacA, the vacuoloatin cytotoxin gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology, 112, 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blaser M.J. and Berg,D.E. (2001) Helicobacter pylori genetic diversity and risk of human disease. J. Clin. Invest., 107, 767–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ando T., Wassenaar,T.M., Peek,R.M., Aras,R.A., Kusugami,K., van Doorn,L. and Blaser,M.J. (2001) hypX shares a genomic locus with the restriction endonuclease gene hpyIIIR in Helicobacter pylori. Int. J. Med. Microbiol., 291 (Suppl. 31), D04. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Figueiredo C., Quint,W.G., Sanna,R., Sablon,E., Donahue,J.P., Xu,Q., Miller,G.G., Peek,R.M.,Jr, Blaser,M.J. and van Doorn,L.J. (2000) Genetic organization and heterogeneity of the iceA locus of Helicobacter pylori. Gene, 246, 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Ende A., Rauwa,E.A.J., Feller,M., Mulder,C.J.J., Tytgat,G.N.J. and Dankert,J. (1996) Heterogeneous Helicobacter pylori isolates from members of a family with a history of peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology, 111, 638–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aras R.A., Takata,T., Ando,T., van der Ende,A. and Blaser,M.J. (2001) Regulation of the HpyII restriction-modification system of Helicobacter pylori by gene deletion and horizontal reconstitution. Mol. Microbiol., 42, 369–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson K. (1987) Miniprep of bacterial genomic DNA. In Ausubel,F.A., Brent,R., Kingsoton,R.E., Moore,D.D. and Sidman,J.G. (eds), Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Green Publishing and Wiley-Interscience, New York, pp. 241–242.

- 34.van Doorn L.J., Figueiredo,C., Rossau,R., Jannes,G., van Asbroek,M., Sousa,J.C., Carneiro,F. and Quint,W.G. (1998) Typing of Helicobacter pylori vacA gene and detection of cagA gene by PCR and reverse hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol., 36, 1271–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Ende A., Pan,Z.J., Bart,A., van der Hulst,R.W., Feller,M., Xiao,S.D., Tytgat,G. N. and Dankert,J. (1998) cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori populations in China and The Netherlands are distinct. Infect. Immun., 66, 1822–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akopyanz N., Bukanov,N.O., Westblom,T.U., Kresovich,S. and Berg,D.E. (1992) DNA diversity among clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori detected by PCR-based RAPD fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 5137–5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reisenauer A., Kahng,L.S., McCollum,S. and Shapiro,L. (1999) Bacteria DNA methylation: a cell cycle regulator? J. Bacteriol., 181, 5135–5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujimoto S., Marshall,B. and Blaser,M.J. (1994) PCR-based restriction fragment polymorphism typing of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol., 32, 331–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang G., Humayun,M.Z. and Taylor,D.E. (1999) Mutation as an origin of genetic variability in Helicobacter pylori. Trends Microbiol., 7, 488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nedenskov-Sorensen P., Bukholm,G. and Bouvre,K. (1990) Natural competence for genetic transformation in Campylobacter pylori. J. Infect. Dis., 161, 365–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segal E.D. and Tompkins,L.S. (1993) Transformation of Helicobacter pylori by electroporation. Biotechniques, 14, 225–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuda M., Karita,M. and Nakazawa,T. (1993) Genetic transformation in Helicobacter pylori. Microbiol. Immunol., 37, 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y., Roos,K.P. and Taylor,D.E. (1993) Transformation of Helicobacter pylori by chromosomal metronidazole resistance and by a plasmid with a selectable chloramphenicol resistance marker. J. Gen. Microbiol., 139, 2485–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Israel D.A., Lou,A.S. and Blaser,M.J. (2000) Characteristics of Helicobacter pylori natural transformation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 15, 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suerbaum S., Smith,J.M., Bapumia,K., Morelli,G., Smith,N.H., Kunstmann,E., Dyrek,I. and Achtman,M. (1998) Free recombination within H. pylori. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 12619–12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bjorkholm B., Sjolund,M., Falk,P.G., Berg,O.G., Engstrand,L. and Andersson,D.I. (2001) Mutation frequency and biological cost of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 14607–14612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poole A., Penny,D. and Sjoberg,B.M. (2001) Confounded cytosine! Tinkering and the evolution of DNA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol., 2, 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Q., Stickel,S., Roberts,R.J., Blaser,M.J. and Morgan,R.D. (2000) Purification of the novel endonuclease, Hpy188I, and cloning of its restriction-modification genes reveal evidence of its horizontal transfer to the Helicobacter pylori genome. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 17086–17093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nobusato A., Uchiyama,I. and Kobayashi,I. (2000) Diversity of restriction-modification gene homologues in Helicobacter pylori. Gene, 259, 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi I. (2001) Behavior of restriction-modification systems as selfish mobile elements and their impact on genome evolution. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 3742–3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Falush D., Kraft,C., Taylor,N.S., Correa,P., Fox,J.G., Achtman,M. and Suerbaum,S. (2001) Recombination and mutation during long-term gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori: estimates of clock rates, recombination size, and minimal age. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 15056–15061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blaser M.J. and Kirschner,D. (1999) Dynamics of Helicobacter pylori colonization in relation to the host response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 8359–8364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]