Abstract

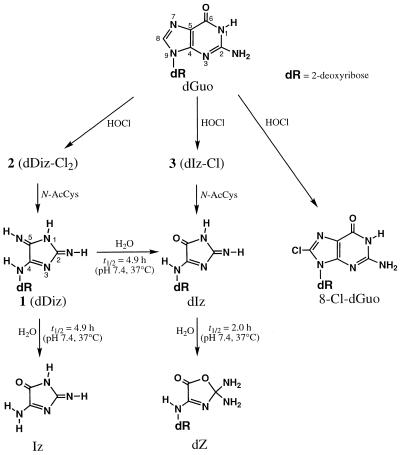

Hypochlorous acid (HOCl), generated by myeloperoxidase from H2O2 and Cl–, plays an important role in host defense and inflammatory tissue injury. We report here the identification of products generated from 2′-deoxyguanosine (dGuo) with HOCl. When 1 mM dGuo and 1 mM HOCl were reacted at pH 7.4 and 37°C for 15 min and the reaction was terminated with N-acetylcysteine (N-AcCys), two products were generated in addition to 8-chloro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-Cl-dGuo). One was identified as an amino-imidazolone nucleoside (dIz), a previously reported product of dGuo with other oxidation systems. The other was identified as a novel diimino-imidazole nucleoside, 2,5-diimino-4-[(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-2H,5H-imidazole (dDiz) by spectrometric measurements. The yields were 1.4% dDiz, 0.6% dIz and 2.4% 8-Cl-dGuo, with 61.5% unreacted dGuo. Precursors of dDiz and dIz containing a chlorine atom were found in the reaction solution in the absence of termination by N-AcCys. dDiz, dIz and 8-Cl-dGuo were also formed from the reaction of dGuo with myeloperoxidase in the presence of H2O2 and Cl– under mildly acidic conditions. These results imply that dDiz and dIz are generated from dGuo via chlorination by electrophilic attack of HOCl and subsequent dechlorination by N-AcCys. These products may play a role in cytotoxic and/or genotoxic effects of HOCl.

INTRODUCTION

Myeloperoxidase is the most abundant protein in neutrophils, accounting for up to 5% of their dry weight (1–3). Myeloperoxidase generates hypochlorous acid (HOCl) as an endogenous product of the respiratory burst from H2O2 and Cl– (4,5). HOCl generated by myeloperoxidase is of central importance in immune surveillance and host defense mechanisms (3). However, the HOCl formed also has potential to harm normal tissue and contribute to inflammatory injury. Chemicals containing hypochlorite (OCl–), the conjugated base of HOCl, are widely used in sanitization of foods, swimming pools and household applications and as a bleaching agent in paper and textile production (6). Moreover, tap water contains small amounts of hypochlorite generated from chlorine (Cl2) added as a disinfectant (7). Hypochlorite is mutagenic in Salmonella typhimurium (8). It has also been shown to be a potential co-carcinogen in a mouse skin tumor carcinogenesis system (9). Since hypochlorous acid is a weak acid with a dissociation constant of pKa = 7.5 at 35°C (10), hypochlorite exists as a mixture of HOCl and OCl– in neutral solution. It is generally believed that HOCl is the active species when hypochlorite is used (11). It has been reported that three types of reaction, i.e. chlorine substitution, addition of HOCl and oxidation, occur between HOCl and organic compounds such as amines, proteins and unsaturated fatty acids (12). The Cl atom in HOCl behaves like Cl+, a strong electrophile, and combines with a pair of electrons in the substrate. In addition, it has been reported that singlet oxygen (1O2) is generated in neutral and mildly acidic solutions of HOCl (13). Moreover, in the presence of superoxide (O2– •) or reduced metal ions, HOCl may generate hydroxyl radicals (•OH) (14,15).

HOCl has been reported to react with nucleic acid bases, resulting in formation of various compounds such as N-chloramine, 5-chloro, 5-chloro-6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydro and 5-hydroxy derivatives from cytosine, a 5-chloro-6-hydroxy derivative and thymine glycol from thymine, N-chloramine and 8-chloro derivatives and parabanic acid from adenine (16–21). However, studies of the reaction of guanine (Gua) with HOCl have been extremely limited, probably due to its complexity. Hayatsu et al. (17) reported formation of several unidentified products in the reaction of guanosine (Guo) with HOCl. Hoyano et al. (19) identified parabanic acid generated from Gua under drastic conditions of two equivalents of HOCl and 1 week incubation. Recently, our group showed that 8-chloroguanosine (8-Cl-Guo) and 8-chloro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-Cl-dGuo) were generated from Guo and 2′-deoxyguanosine (dGuo), respectively, with mild treatment of one equivalent of HOCl in neutral solution at room temperature for 15 min (22). A myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system and activated human neutrophils also generated 8-Cl-(d)Guo from (d)Guo. Moreover, addition of a physiologically relevant dose of tertiary amines such as nicotine or trimethylamine dramatically increased the yield of 8-Cl-(d)Guo in these systems. 8-Cl-(d)Guo was also generated in isolated DNA and RNA following exposure to HOCl. These results suggest that, in cells, the 8-chloro derivative of Gua would be an important DNA/RNA lesion formed by exogenous and endogenous HOCl. Recently, we reported that 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dGuo), an oxidation product of dGuo, reacted readily with the reagent HOCl and the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system to form a spiroiminodihydantoin nucleoside (dSph) almost exclusively (23). More recently, we showed that dSph is also generated by the reaction of dGuo with the reagent HOCl via 8-oxo-dGuo (24). In this reaction, dSph was formed as a major product with low concentrations of HOCl, but the yield of 8-oxo-dGuo was extremely low. The total yield of 8-Cl-dGuo, 8-oxo-dGuo and dSph in the reaction of dGuo with HOCl accounts for at most ∼30% of the consumption of dGuo, so it is clear that some other products are formed in the reaction. We report here the identification and characterization of several novel products formed by the reaction of dGuo with the reagent HOCl and the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

dGuo was purchased from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). 8-Cl-dGuo was purchased from Biolog Life Institute (Bremen, Germany). Human myeloperoxidase (EC 1.11.1.7) was obtained from Alexis (San Diego, CA). All other chemicals of reagent grade were purchased from Fluka, Sigma (St Louis, MO) or Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) and used without further purification. Chloride-free NaOCl was prepared according to a previously reported method (25). The concentration of NaOCl was determined spectrophotometrically at 290 nm using a molar extinction coefficient of 350 M–1 cm–1 (10).

HPLC conditions

The HPLC system consisted of an HP1050 series pumping system (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA). On-line UV spectra were obtained with a Spectra Focus UV-visible photodiode array detector (Spectra Physics, San Jose, CA). For reversed phase HPLC (RP-HPLC), an Ultrasphere octadecylsilane (ODS) column (4.6 × 250 mm, particle size 5 µm; Beckman, Fullerton, CA) was used. The eluent used was 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing acetonitrile. The acetonitrile concentration was increased from 0 to 15% over 20 min in linear gradient mode. The column temperature was 30°C and the flow rate 1 ml min–1.

Spectrometric measurements

NMR spectra were measured using a Bruker DRX-500 spectrometer. NMR spectra were obtained in DMSO-d6 or D2O at 20°C. The chemical shifts (p.p.m.) were referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS) for DMSO-d6 solutions and 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid, sodium salt (TSP-d4) for D2O solutions as external standards. The signal assignments were performed by COSY.

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS)

ESI-MS measurements were performed on a Quattro LC triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, UK). The purified sample was dissolved in 10% methanol containing 0.1% formic acid. The sample was directly infused into the MS system by a syringe pump without a column at a flow rate of 3 µl min–1 and was analyzed in positive ion mode with an electrospray capillary potential of 3.0 kV and a cone potential of 21 V. Collision-induced dissociation of the protonated molecular ions was carried out with a collision energy of 21 V at an argon collision cell pressure of 4.7 × 10–4 kPa.

Preparation of authentic dIz

Authentic 2-amino-5-[(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl) amino]-4H-imidazol-4-one (dIz) was prepared by irradiating a solution of 5 mM dGuo containing 0.6 mM riboflavin with UV light at 366 nm for 2 h at room temperature under aerated conditions (26,27). dIz was isolated from the reaction mixture by RP-HPLC.

Preparation of authentic dSph

Authentic dSph was prepared by the incubation of 1 mM 8-oxo-dGuo with 1 mM NaOCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 15 min (23). dSph was isolated from the reaction mixture by normal phase HPLC (23).

Reaction of dGuo with the reagent HOCl

An aliquot of 1 mM dGuo was incubated with 1 mM NaOCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by incubation with 2 mM N-acetylcysteine (N-AcCys) at 37°C for 1 min.

Reaction of dGuo with the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system

An aliquot of 1 mM dGuo was incubated with 50 nM myeloperoxidase, 200 µM H2O2 and 100 mM NaCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 4.7) at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by incubation with 400 µM N-AcCys at 37°C for 1 min.

Spectrometric data for 2,5-diimino-4-[(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-2H,5H-imidazole (dDiz) (1)

1H NMR (500 MHz, in DMSO-d6 at 20°C): δ (p.p.m./TMS) 8.19 (br, 1H, NH), 7.95 (br, 1H, NH), 7.68 (br, 1H, NH), 5.62 (dd, 1H, H1′), 4.89 (br, 2H, 3′- and 5′-OH), 4.10 (m, 1H, H3′), 3.67 (m, 1H, H4′), 3.41 (ABX, 2H, H5′,5″), 2.06 (ddd, 1H, H2′ or 2″), 1.63 (ddd, 1H, H2′ or 2″). 1H NMR (500 MHz, in D2O at 20°C): δ (p.p.m./TSP-d4) 5.79 (dd, 1H, H1′), 4.39 (m, 1H, H3′), 4.01 (m, 1H, H4′), 3.71 (ABX, 2H, H5′,5″), 2.35 (ddd, 1H, H2′ or 2″), 2.01 (ddd, 1H, H2′ or 2″). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6 at 20°C): δ (p.p.m./TMS) 179.9, 171.7, 162.0, 90.0, 86.4, 71.4, 62.5, 41.4. ESI-MS (positive) m/z: 228 [M + H]+; ESI-MS/MS (positive, daughter ions of m/z 228) m/z: 117 [Mdeoxyribose fragment]+, 112 [Mbase fragment]+; HR-MS (FAB, positive) m/z: 228.109 62 [M + H]+ (calculated for C8H14N5O3, 228.109 66). UV: λmax 255 and 334 nm (pH 7.0).

Spectrometric data for authentic dIz

The spectrometric data for an authentic sample of dIz, obtained from dGuo by riboflavin photosensitization, were essentially identical to the values reported previously (26,27). 1H NMR (500 MHz, in DMSO-d6 at 20°C): δ (p.p.m./TMS) 9.21 (br, 1H, NH), 8.96 (br, 1H, NH), 8.86 (br, 1H, NH), 5.70 (dd, 1H, H1′), 5.11 (br, 1H, 3′- or 5′-OH), 4.81 (br, 1H, 3′- or 5′-OH), 4.21 (m, 1H, H3′), 3.71 (m, 1H, H4′), 3.39 (ABX, 2H, H5′,5″), 2.19 (ddd, 1H, H2′ or 2″), 2.00 (ddd, 1H, H2′ or 2″). ESI-MS (positive) m/z: 229 [M + H]+; ESI-MS/MS (positive, daughter ions of m/z 229) m/z: 117 [Mdeoxyribose fragment]+, 113 [Mbase fragment]+. UV: λmax 252 and 320 nm (pH 7.0).

Spectrometric data for authentic 8-Cl-dGuo

An authentic sample of 8-Cl-dGuo purchased from Biolog Life Institute was examined spectrometrically. 1H NMR (500 MHz, in DMSO-d6 at 20°C): δ (p.p.m./TMS) 10.87 (br, 1H, NH), 6.56 (br, 2H, NH2), 6.17 (dd, 1H, H1′), 5.28 (br, 1H, 3′- or 5′-OH), 4.87 (m, 1H, H3′), 4.38 (br, 1H, 3′- or 5′-OH), 3.78 (m, 1H, H4′), 3.54 (ABX, 2H, H5′,5″), 3.08 (ddd, 1H, H2′ or 2″), 2.11 (ddd, 1H, H2′ or 2″). ESI-MS (positive) m/z: 302 [M(35Cl) + H]+, 304 [M(37Cl) + H]+; ESI-MS/MS (positive, daughter ions of m/z 302) m/z: 117 [Mdeoxyribose fragment]+, 186 [Mbase fragment]+. UV: λmax 256 nm (pH 7.0).

Quantitative procedures

The concentrations of products were evaluated from integrated peak areas of HPLC chromatograms and molar extinction coefficients at 260 nm. The value of ɛ260 = 1.15 × 104 M–1 cm–1 was used for dGuo (28). The values of ɛ260 were estimated as 1.60 × 104 M–1 cm–1 for dDiz, 1.99 × 104 M–1 cm–1 for dIz and 1.54 × 104 M–1 cm–1 for 8-Cl-dGuo from integration of the H1′ proton signal and the RP-HPLC peak area detected at 260 nm relative to those of dGuo. The ɛ value of 8-Cl-dGuo obtained by this method was consistent with the previously reported value for 8-chloroguanosine 5′-monophosphate of 1.53 × 104 M–1 cm–1 at 261 nm and pH 7 (29). The concentrations of chlorinated precursors were estimated assuming that the precursors were converted to dDiz or dIz exclusively by incubation with N-AcCys.

RESULTS

Detection and identification of reaction products of dGuo with the reagent HOCl

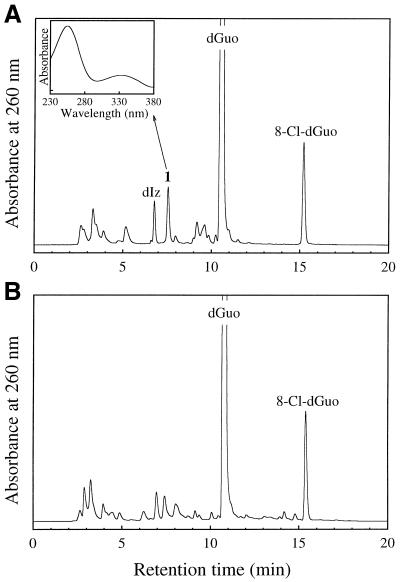

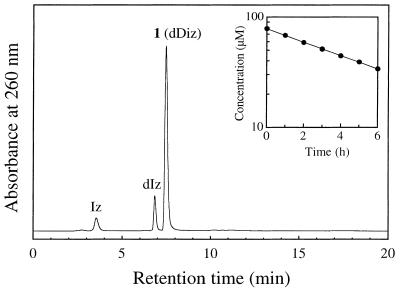

When 1 mM dGuo was reacted with 1 mM HOCl at pH 7.4 and 37°C for 15 min and the reaction was terminated by addition of 2 mM N-AcCys, several peaks were detected on the RP-HPLC chromatogram in addition to unreacted dGuo (Fig. 1A). A product with a retention time (tR) of 15.2 min exhibited an on-line UV spectrum with λmax = 256 nm. Positive ion ESI-MS of the isolated product showed signals at m/z 302 and 304 with relative intensities of 3:1. This product was identified as 8-Cl-dGuo, since the retention time on RP-HPLC, the UV spectrum and the mass spectrum for the product were identical to those for authentic 8-Cl-dGuo. The peak at tR = 6.8 min showed an on-line UV spectrum with λmax = 252 and 320 nm. Positive ion ESI-MS of the isolated product showed a peak at m/z 229. This product was identified as an amino-imidazolone nucleoside, dIz, since the retention time, the UV spectrum and the mass spectrum for the product in the peak were identical to those of authentic dIz. Authentic dSph was eluted near the chromatographic void volume (tR = 2.7 min) by RP-HPLC analysis. We could not quantify dSph in the reaction mixture, since several broad peaks were eluted near the void volume and overlapped one another. Authentic 8-oxo-dGuo was eluted at tR = 11.6 min. 8-oxo-dGuo was not detected in the reaction mixture by RP-HPLC analysis (detection limit 0.1 µM).

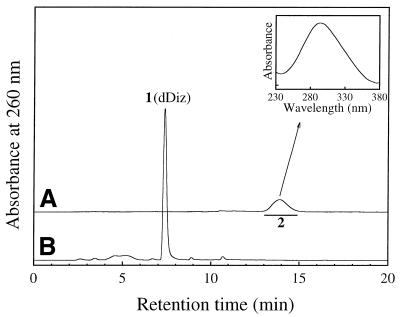

Figure 1.

RP-HPLC chromatogram of dGuo reacted with HOCl with (A) or without (B) termination by N-AcCys. dGuo (1 mM) was incubated with 1 mM NaOCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 15 min. The samples with or without further addition of 2 mM N-AcCys were separated on an ODS column (4.6 × 250 mm). The eluent was 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing acetonitrile. The acetonitrile concentration was increased from 0 to 15% over 20 min in linear gradient mode. The column temperature was 30°C and the flow rate 1 ml/min. (Inset) On-line UV spectrum of 1.

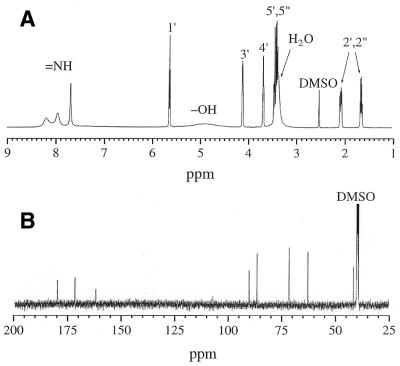

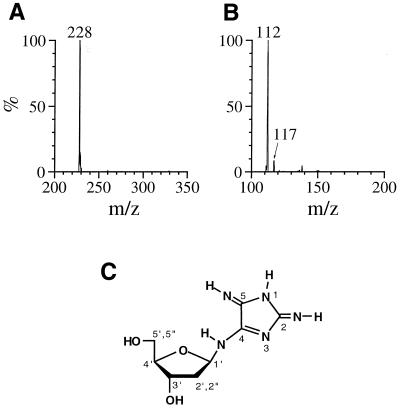

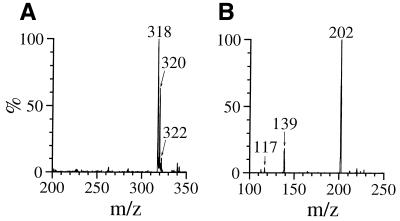

An unknown product (referred to as 1) was eluted as a peak at tR = 7.5 min, which showed a UV spectrum analogous to that of dIz with λmax = 256 and 334 nm (Fig. 1A, inset). Product 1 was isolated by preparative RP-HPLC. Its 1H NMR spectrum in DMSO-d6 showed a set of signals for the intact 2-deoxyribose moiety and three broadened proton signals around 8 p.p.m. (Fig. 2A). All the broadened signals were attributed to exchangeable protons since they disappeared in D2O. The 13C NMR spectrum contained eight resonances (Fig. 2B), of which three were in the aromatic region. Positive ion ESI-MS showed a signal with m/z 228 as the protonated molecular ion of 1 (Fig. 3A). Collision-induced dissociation of the protonated molecular ion produced two major signals at m/z 112 and 117 attributable to the base and the intact 2-deoxyribose fragment ions, respectively (Fig. 3B). High resolution mass spectrometry measurement of the protonated molecular ion of 1 indicated a mass of 228.10962, which agrees with the theoretical molecular mass for the composition of C8H14N5O3 within 0.2 p.p.m. Product 1 was gradually hydrolyzed to dIz and the base moiety of dIz (Iz) at physiological pH and temperature (vide infra). Combining these data, we have tentatively identified 1 as a diimino-imidazole nucleoside, dDiz (Fig. 3C). We observed only three imino proton signals derived from dDiz, although four imino protons were expected for this structure. It is likely that the fourth imino proton signal was completely obscured by further broadening, probably due to exchange with residual water contained in the sample.

Figure 2.

(A) 1H NMR and (B) 13C NMR spectra of product 1 in DMSO-d6 at 20°C. The numbers by the peaks designate the position numbers in the structure of 1 (see Fig. 3C). The signal assignments were performed by COSY.

Figure 3.

(A) Positive ion electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) spectrum of 1. (B) Tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) spectrum of 1 for the parent ion at m/z 228. (C) The structure of product 1, 2,5-diimino-4-[(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-2H,5H-imidazole (dDiz).

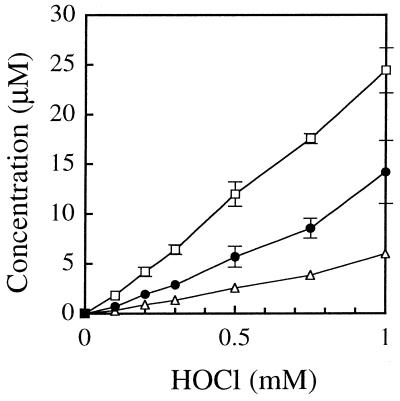

Figure 4 shows the yields of dDiz, dIz and 8-Cl-dGuo when 1 mM dGuo was reacted with various concentrations of HOCl at 37°C for 15 min and the reaction was terminated by addition of one molar excess of N-AcCys. When the HOCl concentration was 1 mM, the concentrations of reaction products were 14.2 µM dDiz, 6.0 µM dIz and 24.4 µM 8-Cl-dGuo, while 615 µM (61.5%) dGuo remained unchanged. Thus, the yields were 1.42% dDiz, 0.60% dIz and 2.44% 8-Cl-dGuo relative to the HOCl added.

Figure 4.

Formation of dDiz (closed circles), dIz (open triangles) and 8-Cl-dGuo (open squares) by the reaction of dGuo with different concentrations of HOCl. dGuo (1 mM) was incubated with 0–1 mM NaOCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 15 min and subsequently incubated with one molar excess of N-AcCys. The concentration of the products was quantified by RP-HPLC analysis. The data points are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3).

Effect of addition of C2H5OH, D2O or nicotine on the dGuo/HOCl system

To obtain information on the reactive species generating dDiz, dIz and 8-Cl-dGuo, dGuo was reacted with HOCl at pH 7.4 in the presence of ethanol (C2H5OH), a scavenger of hydroxyl radicals (•OH), D2O, an enhancer of singlet oxygen (1O2) reactions, or nicotine, a catalyst of HOCl reactions (22). The results are summarized in Table 1. The reaction was not affected when carried out in the presence of C2H5OH or D2O, indicating that •OH and 1O2 do not participate. On the other hand, nicotine increased both the consumption of dGuo and the yields of all the products, suggesting a contribution of HOCl.

Table 1. Effects of C2H5OH, D2O and nicotine on the reaction of dGuo with HOCla.

| Additive | dDiz (µM) | dIz (µM) | 8-Cl-dGuo (µM) | dGuo (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 14.2 ± 3.2 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 24.4 ± 2.3 | 615 ± 2 |

| C2H5OH (2%) | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 22.5 ± 0.1 | 611 ± 9 |

| D2O (50%) | 11.3 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 22.9 ± 0.2 | 592 ± 9 |

| Nicotine (50 µM) | 29.9 ± 1.4 | 9.9 ± 0.6 | 71.8 ± 5.2 | 498 ± 18 |

adGuo (1 mM) was incubated with 1 mM NaOCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in the presence of 2% C2H5OH, 50% D2O or 50 µM nicotine at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of 2 mM N-AcCys. The reaction mixture was analyzed by RP-HPLC. Means ± SD (n = 3) are presented.

Effects of termination of the reaction of dGuo with HOCl by addition of N-AcCys

We used N-AcCys to terminate the reaction of dGuo with HOCl. N-AcCys not only scavenges HOCl and H2O2 but also dechlorinates N-chloramines (30). To clarify the effects of N-AcCys on the formation of the products, the reaction mixtures with or without N-AcCys were analyzed. Table 2 shows the yields of the products and the concentrations of unreacted dGuo with or without N-AcCys termination. A small aliquot of the reaction mixture was immediately injected onto a RP-HPLC column without addition of N-AcCys (Fig. 1B). While many unknown broad peaks were detected in addition to the 8-Cl-dGuo peak, neither dDiz nor dIz was detected. Although several peaks with retention times similar to those of dDiz and dIz appeared in the chromatogram, the UV spectra of the peaks were different from those of dDiz and dIz. The yield of 8-Cl-dGuo was similar to that seen after termination by N-AcCys. The concentrations of unreacted dGuo were similar with or without termination by N-AcCys. These results suggest that the precursors for dDiz and dIz were formed in the reaction mixture before the addition of N-AcCys and subsequently converted into dDiz and dIz by the reaction with N-AcCys.

Table 2. Effects of termination by addition of N-AcCys on the reaction of dGuo with HOCla.

| Condition | DDiz (µM) | dIz (µM) | 8-Cl-dGuo (µM) | dGuo (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +N-AcCys | 14.2 ± 3.2 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 24.4 ± 2.3 | 615 ± 2 |

| –N-AcCys | <0.1 | <0.1 | 22.4 ± 0.5 | 647 ± 13 |

adGuo (1 mM) was incubated with 1 mM NaOCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction mixture was analyzed by RP-HPLC after termination by addition of 2 mM N-AcCys (+N-AcCys) or without termination (–N-AcCys). Means ± SD (n = 3) are presented.

Isolation and characterization of a precursor of dDiz

We attempted to isolate the precursors from the reaction mixture using RP-HPLC. dGuo (1 mM) was reacted with 1 mM HOCl at pH 7.4 and 37°C for 15 min and the reaction mixture was injected immediately into a RP-HPLC column in order to separate various fractions, which were then incubated with N-AcCys. The resulting incubation mixtures were analyzed by RP-HPLC. Incubation with N-AcCys of a RP-HPLC fraction of tR ≈ 14 min gave rise to dDiz. Figure 5A shows the RP-HPLC chromatogram of the purified product of tR = 13.9 min (referred to as 2). The inset shows the on-line UV spectrum of 2 with λmax = 294 nm. The incubation of a RP-HPLC fraction containing 2 with 0.5 mM N-AcCys at pH 7.4 and 37°C for 5 min gave rise to dDiz exclusively and no 2 was detected (Fig. 5B). As shown in Figure 6A, ESI-MS for 2 showed a set of signals with m/z 318, 320 and 322 with relative intensities of 9:6:1, attributable to a molecule containing two chlorine atoms (31). Collision-induced dissociation of the ion of m/z 318 led to signals at m/z 202, attributable to the base fragment ion, and at m/z 117 and 139, attributable to intact 2-deoxyribose and its sodium adduct ion, respectively (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that 2 has a structure with two chlorine atoms substituted in the base moiety of dDiz and we tentatively designated it dDiz-Cl2. The major ion at m/z 318 should be a sodium adduct of dDiz-35Cl2. To examine whether or not dDiz-Cl2 can be generated from dDiz by reaction with HOCl, 1 mM dDiz was incubated with 1 mM NaOCl at pH 7.4 and 37°C for 15 min without termination by N-AcCys. Although four unknown product peaks appeared in the HPLC chromatogram of the reaction mixture, dDiz-Cl2 was not detected (data not shown).

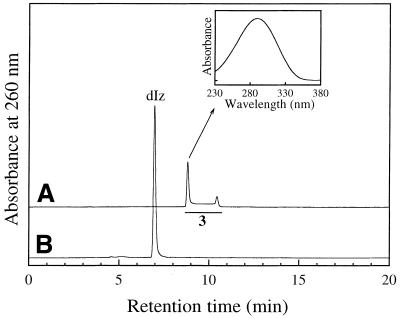

Figure 5.

RP-HPLC analyses for a precursor of dDiz. (A) RP-HPLC chromatogram of purified 2 (dDiz-Cl2), which was isolated by RP-HPLC from the reaction mixture of dGuo (1 mM) incubated with 1 mM NaOCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 15 min without termination with N-AcCys. (Inset) On-line UV spectrum of 2. (B) RP-HPLC chromatogram of a solution of purified 2 incubated with N-AcCys. The isolated 2 was incubated with 0.5 mM N-AcCys in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 5 min and the reaction mixture was injected onto a RP-HPLC column. RP-HPLC conditions were as described in Figure 1.

Figure 6.

(A) Positive ion electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) spectrum of 2. (B) Tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) spectrum of 2 for the parent ion at m/z 318.

Isolation and characterization of a precursor of dIz

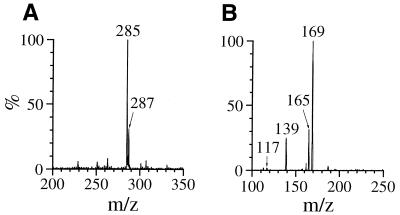

RP-HPLC fractions with tR ≈ 9 min from the reaction mixture gave rise to dIz when incubated with N-AcCys. Figure 7A shows the result of RP-HPLC analysis of the purified product (referred to as 3). Whereas a single product of tR = 8.8 min was isolated and injected into a RP-HPLC column, the chromatogram showed a broadened absorption area ranging from 8.6 to 10.7 min with two distinct peaks at the start (8.8 min) and end (10.4 min) of the range. The on-line UV spectra over this range were closely similar. The inset of Figure 7 shows the on-line UV spectrum at tR = 8.8 min with λmax = 290 nm. Incubation of the RP-HPLC fraction containing 3 with 0.5 mM N-AcCys at 37°C for 5 min gave rise to dIz exclusively and no 3 was detected (Fig. 7B). As shown in Figure 8A, ESI-MS for 3 showed a pair of signals with m/z 285 and 287 with relative intensities of 3:1, attributable to a molecule containing one chlorine atom. Collision-induced dissociation of the ion with m/z 285 led to signals at m/z 169, attributable to the base fragment ion, and at m/z 117 and 139, attributable to intact 2-deoxyribose and its sodium adduct ion, respectively (Fig. 8B). The data suggest that 3 has a structure with one chlorine atom substituted in the base moiety of dIz and we tentatively designated it dIz-Cl. The major ion at m/z 285 should be a sodium adduct of dIz-35Cl. The result of RP-HPLC analysis indicates that 3 is in some kind of equilibrium in neutral solution at 37°C, although it is unclear what structures are involved. To examine whether or not dIz-Cl can be generated from dIz by reaction with HOCl, 1 mM dIz was incubated with 1 mM HOCl at pH 7.4 and 37°C for 15 min without termination by N-AcCys. dIz-Cl was detected in the HPLC chromatogram of the reaction mixture as a major peak (data not shown).

Figure 7.

RP-HPLC analyses for a precursor of dIz. (A) RP-HPLC chromatogram of purified 3 (dIz-Cl) from a reaction mixture of dGuo with HOCl without final N-AcCys treatment. Product 3 was isolated by RP-HPLC from the reaction mixture of dGuo (1 mM) incubated with 1 mM NaOCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 15 min. (Inset) On-line UV spectrum of 3. (B) RP-HPLC chromatogram of a solution of purified 3 incubated with N-AcCys. The isolated 3 was incubated with 0.5 mM N-AcCys in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 5 min and the reaction mixture was injected onto a RP-HPLC column. RP-HPLC conditions were as described inFigure 1.

Figure 8.

(A) Positive ion electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) spectrum of 3. (B) Tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) spectrum of 3 for the parent ion at m/z 285.

Other possible routes for formation of dDiz and dIz

In order to determine whether dDiz and/or dIz are formed via 8-Cl-dGuo, we analyzed the reaction products of authentic 8-Cl-dGuo with HOCl. When 1 mM 8-Cl-dGuo was reacted with 1 mM HOCl at pH 7.4 and 37°C for 15 min and the reaction was terminated by addition of N-AcCys, only trace amounts of dDiz and dIz (both <1% of the starting 8-Cl-Guo) were detected by RP-HPLC (data not shown). This result indicates that 8-Cl-dGuo is not on a major pathway of formation of either dDiz or dIz. There is another possibility for the formation of dIz, i.e. a pathway via dDiz and/or its precursor dDiz-Cl2, since the structure of dIz is that of oxidized dDiz and HOCl is an oxidant. To examine this possibility, we reacted purified dDiz or dDiz-Cl2 with HOCl. When either 1 mM dDiz or ∼5 µM dDiz-Cl2 was reacted with 1 mM HOCl at pH 7.4 and 37°C for 15 min and the reaction was terminated by addition of N-AcCys, no dIz was detected by RP-HPLC (data not shown). These results indicate that dIz is formed from dGuo via neither dDiz nor dDiz-Cl2 under the reaction conditions employed.

Stability of dDiz, dIz, 8-Cl-dGuo, dDiz-Cl2 and dIz-Cl

To evaluate their stability, the products and precursors were incubated in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C and the reaction was monitored by RP-HPLC. When 80 µM dDiz was used in the reaction, dDiz gradually disappeared, giving rise to two products. Figure 9 shows the RP-HPLC chromatogram of the reaction mixture after incubation for 2 h. The third peak (tR = 7.5 min) comprises unreacted dDiz. The second peak (tR = 6.8 min) was attributed to dIz, since the on-line UV (λmax = 252 and 320 nm) and ESI-MS spectra (m/z 229) of the purified peak were identical to those of authentic dIz. The first peak (tR = 3.5 min) is attributable to the base moiety of dIz, denoted Iz, since its on-line UV (λmax = 246 and 318 nm) and ESI-MS spectra (m/z 113) were essentially identical to the published values (32). The plot of concentration of dDiz against incubation time followed first order kinetics (Fig. 9, inset). The rate constant (k1) was evaluated as 3.9 × 10–5 s–1 [half-life (t) = 4.9 h]. The stabilities of other products and precursors were similarly evaluated. dIz disappeared with incubation time with t = 2.0 h. On the other hand, 8-Cl-dGuo was fairly stable, decomposing very slowly with t = 1100 h. dDiz-Cl2 and dIz-Cl, the precursors of dDiz and dIz, were relatively stable with t = 27 h and t = 25 h, respectively, when incubated without any additive such as N-AcCys. Table 3 shows the first-order rate constants and the half-lives of the products and the precursors at pH 7.4 and 37°C.

Figure 9.

RP-HPLC chromatogram of dDiz incubated in neutral solution. dDiz (80 µM) was incubated in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 2 h. (Inset) Exponential plot of the concentration of dDiz as a function of incubation time. The concentration was determined by RP-HPLC analysis.

Table 3. First order rate constants (k1) and half-lives (t) of the products and precursors at pH 7.4 and 37°Ca.

| k1 (s–1) | t (h) | |

|---|---|---|

| dDiz | 3.9 × 10–5 | 4.9 |

| dIz | 9.7 × 10–5 | 2.0 |

| 8-Cl-dGuo | 1.7 × 10–7 | 1100 |

| dDiz-Cl2 | 7.0 × 10–6 | 27 |

| dIz-Cl | 7.7 × 10–6 | 25 |

aEach solution of the products (dDiz, dIz and 8-Cl-dGuo, all 80 µM) and the precursors (dDiz-Cl2 and dIz-Cl, ∼5 µM each) was incubated in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C. The reaction was monitored by RP-HPLC.

Reaction products of dGuo with the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system

In order to examine whether dDiz is formed under physiological conditions, we carried out the reaction of dGuo with myeloperoxidase in the presence of H2O2 and Cl–. When 1 mM dGuo was incubated with 50 nM myeloperoxidase in the presence of 200 µM H2O2 and 100 mM NaCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 4.7) at 37°C for 30 min and the reaction was terminated with 400 µM N-AcCys, dDiz, dIz and 8-Cl-dGuo were formed at concentrations of 1.10, 3.71 and 1.20 µM, respectively. Thus, the yields were 0.55% dDiz, 1.86% dIz and 0.60% 8-Cl-dGuo relative to the H2O2 added.

Table 4 shows the effect of termination by N-AcCys on the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system. The yield of dDiz without N-AcCys was about half the level obtained with N-AcCys. However, the yields of both 8-Cl-dGuo and dIz were unaffected by the presence of N-AcCys. Requirements for the reaction of dGuo with the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system were investigated by omitting individual components (myeloperoxidase, H2O2 or Cl–) from the myeloperoxidase system. In each case, there was no detectable formation of dDiz, dIz and 8-Cl-dGuo (<0.01 µM), indicating that all components of the system are required for generation of these products. Formation of these products was also inhibited by addition to the complete myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system of N3–, a heme enzyme inhibitor, methionine, a scavenger of HOCl and H2O2, or catalase, which decomposes H2O2 (data not shown).

Table 4. Effects of termination by addition of N-AcCys on the formation of dDiz, dIz and 8-Cl-dGuo from dGuo by the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– systema.

| Condition | dDiz (µM) | dIz (µM) | 8-Cl-dGuo (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| +N-AcCys | 1.10 ± 0.04 | 3.71 ± 0.16 | 1.20 ± 0.03 |

| –N-AcCys | 0.66 ± 0.01 | 3.91 ± 0.06 | 1.21 ± 0.05 |

adGuo (1 mM) was incubated with myeloperoxidase (50 nM) in the presence of H2O2 (200 µM) and NaCl (100 mM) in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 4.7) at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction mixture was analyzed by RP-HPLC after termination by addition of 400 µM N-AcCys (+N-AcCys) or without termination (–N-AcCys). Means ± SD (n = 3) are presented.

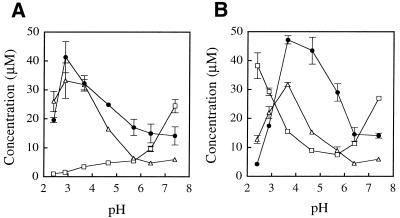

Figure 10 illustrates the effects of varying reaction conditions on the formation of the products from dGuo by the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system. The yields of the products increased in a dose-dependent manner with increasing concentration of either H2O2 or Cl– (Fig. 10A and B, respectively). The optimal concentration of H2O2 for formation of dDiz, dIz and 8-Cl-dGuo was 300 µM. The optimal concentration of NaCl for formation of dDiz and dIz was 150 mM, i.e. close to human plasma concentrations. Figure 10C shows the pH dependence of the yields of the products. Although at pH 7.4 the yields of the products were extremely low, they increased at lower pH. The optimal pH for formation of dDiz and dIz was 4.7, whereas that for the formation of 8-Cl-dGuo was ∼3.7.

Figure 10.

Change in yield of dDiz (closed circles), dIz (open triangles) and 8-Cl-dGuo (open squares) from dGuo with the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system. An aliquot of 1 mM dGuo was incubated with 50 nM myeloperoxidase in the presence of H2O2 (200 µM) and NaCl (100 mM) in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 4.7) at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of one molar excess of N-AcCys. The H2O2 concentration (A), the NaCl concentration (B) or the pH value (C) was varied. The pH values were determined at the end of the incubation prior to N-AcCys addition. The yields of the products were determined by RP-HPLC analysis. The data points are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3).

pH dependence of the dGuo/HOCl system without and with NaCl

For the reaction of dGuo with the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system, the optimal pH for product formation was in the acidic region. Under acidic conditions, chloride (Cl–) can react with HOCl and H+ to generate Cl2, another chlorinating species. To obtain information on the contribution of Cl2, we examined the pH dependence of the reaction of dGuo and the reagent HOCl without or with NaCl under neutral and acidic conditions. Figure 11A and B shows the effects of pH on the yields of the products formed by the dGuo/HOCl system in the absence and presence of NaCl, respectively. At neutral pH, NaCl did not affect the yield of any product, indicating no contribution of Cl2. Below pH 5, the yield of 8-Cl-dGuo increased with lower pH in the presence of NaCl, whereas the yields of dDiz and dIz decreased under acidic conditions (pH < 3) even in the presence of NaCl. These results suggest that Cl2 is involved only in 8-Cl-dGuo formation and not in dDiz and dIz formation under acidic conditions.

Figure 11.

pH dependence of the yields of dDiz (closed circles), dIz (open triangles) and 8-Cl-dGuo (open squares) on the dGuo/HOCl system in the absence (A) and presence (B) of NaCl. dGuo (1 mM) was incubated with 1 mM NaOCl in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer of various pH at 37°C for 15 min in the absence and presence of NaCl (100 mM) and subsequently incubated with 2 mM N-AcCys. The concentration of the products was quantified by RP-HPLC analysis. The data points are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

We have found that two products in addition to 8-Cl-dGuo are generated by the reaction of dGuo with HOCl terminated by N-AcCys at neutral pH and physiological temperature. One product was identified as a novel diimino-imidazole nucleoside (dDiz) from the spectrometric data. Since addition of ethanol or D2O did not affect the reaction, a contribution of •OH or 1O2 to the formation of dDiz was ruled out. Addition of nicotine enhanced the reaction, indicating a contribution of HOCl, since nicotine catalyzes HOCl reactions, probably via formation of a reactive nicotine–Cl+ adduct (22). The results on the pH dependence of the yield of dDiz suggest that Cl2 is not involved. A precursor (dDiz-Cl2) containing two chlorine atoms was isolated from the reaction mixture of dGuo and HOCl when the reaction was not terminated with N-AcCys. dDiz-Cl2 was converted to dDiz by incubation with N-AcCys. 8-Cl-dGuo was not a major precursor of dDiz. These reaction paths are summarized in Scheme 1. HOCl is generated by protonation of OCl–. dGuo may be substituted on its base moiety by two chlorine atoms via electrophilic attack of HOCl, giving rise to dDiz-Cl2, the precursor of dDiz containing two chlorine atoms. The chlorine atoms on dDiz-Cl2 are removed by N-AcCys, resulting in dDiz. The other product was an amino-imidazolone nucleoside (dIz) which has the structure of dDiz with one imino group replaced by an oxygen atom. dIz has been reported as a major product formed from dGuo with •OH and one-electron oxidation in the presence of molecular oxygen or with 1O2 (25,27,33,34). However, since addition of ethanol or D2O to the dGuo/HOCl system did not affect the yield of dIz, a contribution of •OH or 1O2 to the formation of dIz was ruled out. Neither dIz nor Iz was generated from isolated dDiz by HOCl treatment. The results of addition of nicotine and the pH dependence of the yield of dIz suggest the involvement of HOCl but not Cl2. A precursor (dIz-Cl) containing a chlorine atom was isolated from the reaction of dGuo and HOCl when the reaction was not terminated with N-AcCys. dIz-Cl was converted to dIz by incubation with N-AcCys. dIz-Cl was also formed from dIz by HOCl. 8-Cl-dGuo was not a major precursor of dIz. Thus, dIz could be generated from dGuo by electrophilic attack of HOCl through dIz-Cl and subsequent release of a chlorine atom by N-AcCys (Scheme 1). In contrast to dDiz and dIz, 8-Cl-dGuo was generated directly in the dGuo/HOCl system without incubation with N-AcCys. A mechanism for formation of 8-Cl-dGuo including a Cl+ adduct at N7 of dGuo and migration of Cl to C8 has been proposed (22).

Scheme 1.

In the present study, dDiz, dIz and 8-Cl-dGuo were also produced from dGuo by the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system under mildly acidic conditions. The myeloperoxidase system required both H2O2 and Cl– to generate the products. Recently, we have reported that 8-oxo-dGuo was converted to a further oxidized product, dSph, by a myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system (23). In contrast to dGuo, the reaction of 8-oxo-dGuo occurred almost quantitatively with the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system at neutral pH. Moreover, a significant amount of dSph was generated by the myeloperoxidase system even in the absence of Cl–. Ground-state myeloperoxidase uses H2O2 as a substrate, oxidized by two electron equivalents to form a redox intermediate termed compound I (3). Oxidation of Cl– by compound I occurs through a single two-electron transfer reaction to generate HOCl. The reaction of 8-oxo-dGuo could occur either by direct oxidation with compound I itself or by electrophilic attack of HOCl generated from Cl– and compound I. A previous kinetic study of oxidation of Cl– by compound I revealed that at pH 7 the second-order rate constant was two orders of magnitude less than at pH 5 (35). The optimal pH for formation of HOCl by the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system was in the mildly acidic region and was dependent on the ratio of H2O2 to Cl– (36). In the present study, the reaction of dGuo with the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system required Cl– and had an optimal pH in the mildly acidic region. These findings imply that formation of HOCl is essential for the reaction with dGuo. In addition to HOCl, another possible reactive species is molecular chlorine (Cl2), another chlorinating reagent, in the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system under acidic conditions, since HOCl is in equilibrium with Cl2 in acidic solution in the presence of Cl– (37). Recently, Henderson et al. (38) have reported the formation of 5-chloro-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Cl-dCyd) from 2′-deoxycytidine (dCyd) by a myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system and the reagent HOCl under mildly acidic conditions. The yield of 5-Cl-dCyd increased at higher H+ concentration in the presence of Cl– in the reaction of dCyd with the reagent HOCl. From this result, they concluded that the oxidizing intermediate for generation of 5-Cl-dCyd is a Cl2-like species but not HOCl itself. Our group has reported the formation of 8-Cl-dGuo from dGuo by a myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system and the reagent HOCl (22). The yield of 8-Cl-Guo with the reagent HOCl increased at lower pH (below pH 5) in the presence of Cl–, suggesting the involvement of a Cl2-like species as a reactive intermediate below pH 5. However, in contrast to 5-Cl-dCyd, the yield of 8-Cl-Guo increased irrespective of the level of Cl– with an increase in pH from neutral to basic, suggesting that the reactive intermediate generating 8-Cl-dGuo is HOCl under neutral conditions. In the present study, the optimal pH for formation of dDiz and dIz (pH 4.7) was different from that for 8-Cl-dGuo (pH ∼3.7) in the reaction of dGuo with the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system (Fig. 10C). The results for pH dependence of the dGuo/HOCl system suggest that the reactive species generating dDiz and dIz is HOCl but not Cl2 even under acidic conditions (Fig. 11). It is likely that the optimal pH of 4.7 for dDiz and dIz formation by the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system corresponds to the reaction with HOCl and that the optimal pH of 3.7 for 8-Cl-dGuo formation corresponds to the reaction with Cl2 generated from HOCl by the reaction with Cl– and H+.

In the reaction of dGuo with HOCl, chlorinated precursors, dDiz-Cl2 and dIz-Cl, were initially generated. Both these precursors were relatively stable with half-lives of ∼1 day at pH 7.4 and 37°C (Table 3). dDiz-Cl2 and dIz-Cl were immediately converted into dDiz and dIz, respectively, by N-AcCys at neutral pH and at physiological temperature. Since the concentrations of Cys in healthy humans are 110 µM in plasma and 180 µM in intracellular skeletal muscle fluid (39), if the same precursors were generated in humans, they should be immediately converted to dDiz and dIz by the reaction with inter- and intracellular Cys. The conversion of dIz from the chlorinated precursors with the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system under mildly acidic conditions proceeded equally without N-AcCys, whereas only half the amount of dDiz was generated in the absence of N-AcCys (Table 4). It is likely that dechlorination of the precursors also proceeds in the presence of protein under mildly acidic conditions, although we cannot rule out involvement of direct formation of dDiz and/or dIz from dGuo by reaction with 1O2 or •OH generated in the myeloperoxidase–H2O2–Cl– system. The half-life of dDiz was 4.9 h at pH 7.4 and 37°C giving rise to dIz and its base moiety, Iz (Scheme 1). If a similar conversion occurs in DNA, it will result in a dIz moiety and an abasic site, which is potentially mutagenic (40), in the DNA strand. dIz decomposed with a half-life of 2.0 h at pH 7.4 and 37°C. It has been reported that dIz is hydrolyzed in neutral solution to form a diamino-oxazolone nucleoside (dZ) (Scheme 1) that is stable under physiological conditions (27). The present results and previous data suggest that once the chlorinated precursors are formed from dGuo, two reaction sequences [dDiz-Cl2 → dDiz → dIz (+ Iz) → dZ and dIz-Cl → dIz → dZ] proceed in parallel. Recently, it has been shown that dZ in an oligodeoxynucleotide induces mainly dAMP insertion by DNA polymerases (41). Thus, the formation of dZ in DNA should lead to a G→T transversion if the lesion is not repaired. On the other hand, no information is currently available for the other lesions, such as dDiz, dIz, dDiz-Cl2 and dIz-Cl, on cytotoxicity or genotoxicity. To elucidate the biological implications of these lesions as well as 8-Cl-dGuo, further studies are necessary.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr J. Cheney for editing the manuscript. We also thank Mr D. Bouchu and Ms L. Rousset of the Centre de Spectrométrie de Masse of the Université Lyon 1 for acquiring the high resolution mass spectrum. The work reported in this paper was undertaken during the tenure of a Special Training Award granted to T.S. by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agner K. (1941) Verdoperoxidase: a ferment isolated from leucocytes. Acta Physiol. Scand., 2 (suppl. VIII), 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schultz J. and Kaminker,K. (1962) Myeloperoxidase of the leucocyte of normal human blood. I: content and localization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 96, 465–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kettle A.J. and Winterbourn,C.C. (1997) Myeloperoxidase: a key regulator of neutrophil oxidant production. Redox Rep., 3, 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison J.E. and Schultz,J. (1976) Studies on the chlorinating activity of myeloperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem., 251, 1371–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foote C.S., Goyne,T.E. and Lehrer,R.I. (1983) Assessment of chlorination by human neutrophils. Nature, 301, 715–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. International Agency of Research on Cancer (1991) Hypochlorite salt. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol. 52, Chlorinated Drinking-water; Chlorination By-products; Some Other Halogenated Compounds; Cobalt and Cobalt Compounds. IARC, Lyon, pp. 159–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Schmittinger P. (2000) Uses of chlorine. In Schmittinger,P. (ed.), Chlorine–Principles and Industrial Practice. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, pp. 159–222.

- 8.Wlodkowski T.J. and Rosenkranz,H.S. (1975) Mutagenicity of sodium hypochlorite for Salmonella typhimurium. Mutat. Res., 31, 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayatsu H., Hoshino,H. and Kawazoe,Y. (1971) Potential cocarcinogenicity of sodium hypochlorite. Nature, 233, 495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris J.C. (1966) The acid ionization constant of HOCl from 5 to 35°. J. Phys. Chem., 70, 3798–3805. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wojtowicz J.A. (1979) Chlorine oxygen acids and salts: chlorine monoxide, hypochlorous acid and hypochlorites. In Mark,H.F., Othmer,D.F., Overberger,C.G., Seaborg,G.T. and Grayson,M. (eds), Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 3rd Edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, Vol. 5, pp. 580–611.

- 12.Brezonik P.L. (1994) Chemical Kinetics and Process Dynamics in Aquatic Systems. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 236–237.

- 13.Khan A.U. and Kasha,M. (1994) Singlet molecular oxygen evolution upon simple acidification of aqueous hypochlorite: application to studies on the deleterious health effects of chlorinated drinking water. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 12362–12364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Candeias L.P., Patel,K.B., Stratford,M.R.L. and Wardman,P. (1993) Free hydroxyl radicals are formed on reaction between the neutrophil-derived species superoxide anion and hypochlorous acid. FEBS Lett., 333, 151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candeias L.P., Stratford,M.R.L. and Wardman,P. (1994) Formation of hydroxyl radicals on reaction of hypochlorous acid with ferrocyanide, a model iron(II) complex. Free Radic. Res., 20, 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patton W., Bacon,V., Duffield,A.M., Halpern,B., Hoyano,Y., Pereira,W. and Lederberg,J. (1972) Chlorination studies. I. The reaction of aqueous hypochlorous acid with cytosine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 48, 880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayatsu H., Pan,S.-K. and Ukita,T. (1971) Reaction of sodium hypochlorite with nucleic acids and their constituents. Chem. Pharm. Bull. Jpn, 19, 2189–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whiteman M., Jenner,A. and Halliwell,B. (1997) Hypochlorous acid-induced base modifications in isolated calf thymus DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 10, 1240–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoyano Y., Bacon,V., Summons,R.E., Pereira,W.E., Halpern,B. and Duffield,A.M. (1973) Chlorination studies. IV. The reaction of aqueous hypochlorous acid with pyrimidine and purine bases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 53, 1195–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernofsky C., Bandara,B.M.R. Hinojosa,O. and Strauss,S.L. (1990) Hypochlorite-modified adenine nucleotides: structure, spin-trapping and formation by activated guinea pig polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Free Radic. Res. Commun., 9, 303–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteman M., Jenner,A. and Halliwell,B. (1999) 8-Chloroadenine: a novel product formed from hypochlorous acid-induced damage to calf thymus DNA. Biomarkers, 4, 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masuda M., Suzuki,T., Friesen,M.D., Ravanat,J.-L., Cadet,J., Pignatelli,B., Nishino,H. and Ohshima,H. (2001) Chlorination of guanosine and other nucleosides by hypochlorous acid and myeloperoxidase of activated human neutrophils: catalysis by nicotine and trimethylamine. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 40486–40496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki T., Masuda,M., Friesen,M.D. and Ohshima,H. (2001) Formation of spiroiminodihydantoin nucleoside by reaction of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine with hypochlorous acid or a myeloperoxidase-H2O2-Cl– system. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 14, 1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki T. and Ohshima,H. (2002) Nicotine-modulated formation of spiroiminodihydantoin nucleoside via 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine in 2′-deoxyguanosine–hypochlorous acid reaction. FEBS Lett., 516, 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hazen S.L., Hsu,F.F., Gaut,J.P., Crowley,J.R. and Heinecke,J.W. (1999) Modification of proteins and lipids by myeloperoxidase. Methods Enzymol., 300, 88–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cadet J., Berger,M., Buchko,G.W., Joshi,P.C., Raoul,S. and Ravanat,J.-L. (1994) 2,2-Diamino-4-[(3,5-di-acetyl-2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-5-(2H)-oxazolone: a novel and predominant radical oxidation product of 3′,5′-di-acetyl-2′-deoxyguanosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 116, 7403–7404. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raoul S., Berger,M., Buchko,G.W., Joshi,P.C., Morlin,B., Weinfeld,M. and Cadet,J. (1995) 1H, 13C and 15N nuclear magnetic resonance analysis and chemical features of the two main radical oxidation products of 2′-deoxyguanosine: oxazolone and imidazolone nucleosides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 371–381. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 29.Lassota P., Stolarski,R. and Shugar,D. (1983) Conformation about the glycosidic bond and susceptibility to 5′-nucleotidase of 8-substituted analogues of 5′-GMP. Z. Naturforsch., 39c, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peskin A.V. and Winterbourn,C.C. (2001) Kinetics of the reactions of hypochlorous acid and amino acid chloramines with thiols, methionine and ascorbate. Free Radic. Biol. Med., 30, 572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLafferty F.W. and Turecek,F. (1993) Interpretation of Mass Spectra, 4th Edn., University Science Books, Mill Valley, CA, pp. 19–34.

- 32.Vialas C., Pratviel,G., Meyer,A., Rayner,B. and Meunier,B. (1999) Obtention of two anomers of imidazolone during the type I photosensitized oxidation of 2′-deoxyguanosine. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchko G.W., Wagner,J.R., Cadet,J. Raoul,S. and Weinfeld,M. (1995) Methylene blue-mediated photooxidation of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1263, 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raoul S. and Cadet,J. (1996) Photosensitized reaction of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine: identification of 1-(2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)cyanuric acid as the major singlet oxygen oxidation product. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 118, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakkenist A.R.J., de Boer,J.E.D., Plat,H. and Wever,R. (1980) The halide complexes of myeloperoxidase and the mechanism of the halogenation reactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 613, 337–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furtmüller P.G., Burner,U. and Obinger,C. (1998) Reaction of myeloperoxidase compound I with chloride, bromide, iodide and thiocyanate. Biochemistry, 37, 17923–17930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hazen S.L., Hsu,F.F., Mueller,D.M., Crowley,J.R. and Heinecke,J.W. (1996) Human neutrophils employ chlorine gas as an oxidant during phagocytosis. J. Clin. Invest., 98, 1283–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henderson J.P., Byun,J. and Heinecke,J.W. (1999) Molecular chlorine generated by the myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-chloride system of phagocytes produces 5-chlorocytosine in bacterial RNA. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 33440–33448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergström J., Fürst,P., Norée,L.-O. and Vinnars,E. (1974) Intercellular free amino acid concentration in human muscle tissue. J. Appl. Physiol., 36, 693–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loeb L.A. and Preston,B.D. (1986) Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Annu. Rev. Genet., 20, 201–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duarte V., Gasparutto,D., Jaquinod,M. and Cadet,J. (2000) In vitro DNA synthesis opposite oxazolone and repair of this DNA damage using modified oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1555–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]