Summary

Background

Previous prediction models for adiposity gain have not yet achieved sufficient predictive ability for clinical relevance. We investigated whether traditional and genetic factors accurately predict adiposity gain.

Methods

A 5-year gain of ≥5% in body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) from baseline were predicted in mid-late adulthood individuals (median of 55 years old at baseline). Proportional hazards models were fitted in 245,699 participants from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort to identify robust environmental predictors. Polygenic risk scores (PRS) of 5 proxies of adiposity [BMI, WHR, and three body shape phenotypes (PCs)] were computed using genetic weights from an independent cohort (UK Biobank). Environmental and genetic models were validated in 29,953 EPIC participants.

Findings

Environmental models presented a remarkable predictive ability (AUCBMI: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.68–0.70; AUCWHR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.74–0.77). The genetic geographic distribution for WHR and PC1 (overall adiposity) showed higher predisposition in North than South Europe. Predictive ability of PRSs was null (AUC: ∼0.52) and did not improve when combined with environmental models. However, PRSs of BMI and PC1 showed some prediction ability for BMI gain from self-reported BMI at 20 years old to baseline observation (early adulthood) (AUC: 0.60–0.62).

Interpretation

Our study indicates that environmental models to discriminate European individuals at higher risk of adiposity gain can be integrated in standard prevention protocols. PRSs may play a robust role in predicting adiposity gain at early rather than mid-late adulthood suggesting a more important role of genetic factors in this life period.

Funding

French National Cancer Institute (INCA_N°2019-176) 1220, German Research Foundation (BA 5459/2-1), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Miguel Servet Program CP21/00058).

Keywords: Adiposity gain, Prediction, Polygenic risk scores, Environmental factors

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Previous research has shown that environmental prediction models incorporating socio-demographic and lifestyle factors lack the predictive accuracy necessary for clinical relevance in forecasting adiposity gain. While genetic factors are known to contribute to obesity, their combined predictive ability with environmental factors has not yet been thoroughly evaluated.

Added value of this study

This study leverages data from the extensive European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort to evaluate both environmental and genetic predictors of adiposity gain. By employing proportional hazards models and polygenic risk scores (PRS) derived from the UK Biobank, we assessed the predictive capabilities of these factors over a 5-year period. Our findings highlight that environmental models alone offer significant predictive ability for BMI and WHR gain. However, the integration of PRSs shows considerable predictive ability specifically for BMI gain in early adulthood, though it remains ineffective in mid-late adulthood.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our study underscores the importance of integrating robust environmental models into standard adiposity prevention protocols, as these models can effectively identify individuals at higher risk of adiposity gain. The limited predictive ability of PRSs in mid-late adulthood suggests that genetic factors may play a more crucial role in early adulthood. These insights emphasize the need for age-specific approaches in using genetic data for predicting adiposity, paving the way for more tailored prevention strategies across different life stages. This research supports the potential for personalized prevention programs that account for both environmental and genetic factors, enhancing the overall effectiveness of obesity prevention efforts.

Introduction

Obesity is characterized by excess body fat and is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2. In the WHO European Region, approximately 23% of adults are living with obesity, and the prevalence is projected to increase to 30% by 2030.1 Obesity has substantial economic and societal impacts, it is a major determinant of disability, and 22% of preventable deaths result from a high BMI in the European region.1

Among the main drivers of obesity are environmental factors that favour a positive energy balance and weight gain2; however, individual predisposition to obesity also has a heritable and genetic basis.3,4 Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified thousands of genetic loci associated with obesity-related anthropometric traits,3,4 including body shape phenotypes.5 A single genetic locus has a minimal impact on complex traits; however, the cumulative genetic risk can be substantial.6 Polygenic risk scores (PRS) have been progressively investigated to predict individuals at higher risk of a particular condition.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 In addition, PRS have also been used to assess the genetic contribution to the European regional differences in anthropometric traits.12 Recently developed Bayesian approaches for building PRS allow modelling linkage disequilibrium (LD) between genetic variants to generate genome-wide infinitesimal models that outperform the traditional approach of pruning by LD followed by P value threshold.13 Thus, Bayesian-based PRS on anthropometric traits could improve the predictive ability beyond environmental models.

Several attempts to identify individuals that are more prone to weight gain have been made in the last years, but with little success or generalizability.14,15 For instance, Steffen et al. developed a predictive score for substantial weight gain (10% or more) over 5 years among European adults from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort.14 This model included 13 socio-demographic, dietary, and lifestyle factors that showed a rather low predictive ability. Therefore, discovery of other relevant predictors beyond those previously examined is needed. Whether PRS of obesity could improve prediction of adiposity gain has not been investigated.

In this work, we aimed to develop and validate a prediction model for adiposity gain based on environmental predictors and evaluate the added value of PRS in 275,652 EPIC participants across 8 European countries. We first built environmental models to predict 5-years BMI and WHR gain. Second, we computed Bayesian-based PRSs for anthropometric traits (BMI, WHR, and three distinct body shapes). Third, we fitted the PRSs in 47,014 individuals from UK Biobank and assessed their predictive ability beyond the environmental models.

Methods

Study population: EPIC cohort

The EPIC study is a European prospective multicentre cohort that recruited approximately 520,000 men and women between 1992 and 2000.16,17 Most of the participants were aged between 35 and 65 at baseline and were selected from the general population, with few exceptions (Supplemental text), of Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Exclusion criteria were based on individuals with cancer, unrealistic anthropometric traits measurements, and from Greece and Norway due to administrative reasons (Fig. S1). Sample was divided into two groups: development (N = 245,699) and validation (N = 29,953) depending on the availability of genetic data to compare the different prediction models in the same group of individuals. Further details on exclusions and sample sizes are included in Supplemental text and Fig. S1.

Anthropometry and lifestyle factors

At baseline, weight, height, waist, and hip circumference were measured by trained personnel following standard protocols, except France and UK–Oxford, where these traits were self-reported (Supplemental text).18 At follow-up, anthropometric traits were self-reported, except for UK–Norfolk and NL-Doetinchem, where they were measured. The mean time difference between baseline and assessments was 7.4 years across study centres, ranging between 3.3 and 11.9 years. Data on self-reported weight at age 20 years was also collected.

At baseline, information on socio-demographic and lifestyle factors, and medical history were collected using questionnaires.17 Further, participants reported their average food consumption over the past year. Food intake (gram/day) was obtained considering the frequency intake as well as the portion size.

Statistics–environmental models

We developed prediction models for a ≥5% gain in BMI and WHR over a 5-year period. The ≥5% threshold was selected to avoid random anthropometric trait variation and for its clinical importance.19 A total of 245,699 and 44,190 EPIC participants with repeated measurements of BMI and WHR data, respectively, were used to train the environmental models. Mann–Whitney U and chi-squared tests were performed to evaluate differences between development and validation samples. Predictors included in the proportional hazard model were selected using a stepwise forward model selection based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Potential predictors available in EPIC included 40 socio-demographic characteristics such as age, country, sex and level of education, as well as lifestyle factors including the anthropometric trait at baseline, smoke (status and intensity), physical activity, alcohol intake (at recruitment and pattern) and up to 30 different food groups (alcoholic beverages; cakes and biscuits; carbonated/soft/isotonic drinks, diluted syrups; cereal and cereal products; coffee, tea, herbal teas; condiments and sauces; dairy products; egg and egg products; fat; fish and shellfish; fruit and vegetable juices; fruits, nuts and seeds; legumes; meat and meat products; miscellaneous; non-alcoholic beverages; potatoes and other tubers; soups, bouillons; sugar and confectionary; USDA Alcohol, ethyl (g); USDA Carbohydrate, by difference (g); USDA Energy (kcal); USDA Protein (g); USDA Total lipid (fat) (g); vegetables; waters; and the four NOVA groups which assess the level of food processing). Food groups were measured in grams per day (g/day), unless otherwise indicated. Predictors presenting a beta estimate lower than 0.001 (both sides) were removed to achieve a simpler model with the strongest predictors. Correlations between selected predictors were estimated to assess potential multicollinearity. A model excluding the predictor country was further assessed to enhance generalizability.

We used Cox proportional hazard regression to estimate the coefficients for the predictors and to account for the time of reaching BMI and WHR gain. An event was defined as a ≥5% gain between baseline and second assessment of BMI or WHR, respectively. Time to event for cases assumed a linear BMI or WHR gain. Non-cases were censored at the end of follow-up.

Five-year absolute risks were estimated by combining the relative risk estimates from the Cox regression with the baseline survivor function (Supplemental text).20,21 The predictive ability of all models was evaluated in the validation sample of 29,953 (11% of the whole sample) and 6456 (13%) EPIC participants for BMI and WHR gain, respectively, through cumulative/dynamic time-dependent AUC at time 5 years.22, 23, 24

Statistical analyses were performed using timeROC package25 in R 4.2.1 and RStudio.26,27

Genome-wide data

Genetic data was available from 29,953 EPIC participants (validation prediction sample) from 20 case–control studies. DNA samples were genotyped through different genotyping platforms. Details on genotyping platforms, and sample sizes for each case–control study can be found in Supplemental text and Table S1. Genetic data were normalized, centralised, and imputed at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Normalization across studies was performed to complete information on chromosome, position, and allele codes, harmonize the genome build version between studies, fix the strand orientation on the positive strand, and standardize the genetic variants annotation. Centralisation was based on the following exclusions: sample and genetic variants call rate (cut off >90%), sex discrepancies between genotype and phenotype, close relatives (>0.8), and population outliers to mitigate the variance introduced by diverse ancestries. Imputation was performed by the Michigan imputation server using the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 v528 as reference panel in the Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37. Finally, post-imputation quality control was performed keeping the genetic variants by minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.01 and imputation info-score >0.3.

Data on 47,014 individuals from UK Biobank with at least two measurements of BMI and WHR were extracted. UK Biobank is a prospective cohort study with over 500,000 individuals from 22 study centres in England, Scotland, and Wales. Participants between 38 and 73 years old were recruited between 2006 and 2010. Data on anthropometry, lifestyle, health-related indicators, and biological samples were collected.29 Individuals were genotyped using either a custom Affymetrix UK Biobank Axiom Array chip or a custom Affymetrix UK BiLEVE Axiom Array chip.29,30

Statistics–genome-wide models

To develop Bayesian-based PRSs, we obtained summary statistics from large GWAS on BMI, WHR, and three body shapes. Body shape phenotypes are derived from principal component (PC) analyses of 6 anthropometric traits (height, weight, BMI, waist and hip circumferences, and WHR). It is observed that the first 3 PCs (PC1-3) are independent and genetically capturing additional adiposity than BMI and WHR. PC1 characterized overall adiposity. In contrast to previous publications,5,31,32 the PRS of PC2 was reversed defining short individuals with central adiposity. PC3 described tall individuals with central adiposity. Further details can be found in Supplemental text. PRSs in EPIC were computed for these 5 proxies of adiposity using the LDPred2-auto computation algorithm.33 LDpred2-auto is a Bayesian approach that showed improved predictive performance for PRSs, though the performance may vary depending on the specific trait.33 LDpred2-auto estimates the regional LD structure using GWAS summary level statistics and a LD reference panel based on 1,444,196 genetic variants from HapMap3 (Supplemental text).33 PRS were standardized through z-score transformation to enhance interpretability. The geographic distribution of PRS across EPIC countries was assessed and compared with the geographic distribution of similar PRS of 396 European participants from the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 (UK [N = 89], Finland [N = 96], Italy [N = 107], and Spain [N = 104]).28

We assessed the association between PRSs and BMI and WHR gain, separately, using Cox proportional hazard models. These were adjusted for age at baseline, country, sex, first ten genetic PCs, batch, and BMI or WHR at baseline. Analyses were performed by sex, North and South Europe, and above and below median baseline age (55 years) (Supplemental text). Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare models with and without multiplicative interaction terms between PRSs and sex, PRSs and European region, and PRSs and age. PRSs and Cox proportional hazard models were also derived and fitted in UK Biobank sample to independently estimate the coefficients of the PRSs in relation to BMI and WHR gain.

The predictive ability of the 5 PRSs was validated in EPIC (N = 29,953 and 6456 for BMI and WHR gain, respectively) individually and combined with the environmental models. Specifically, for BMI gain, we combined the environmental model with each of the PRS for BMI and the three body shape phenotypes. Likewise, for WHR gain, we combined the environmental model with the PRS of WHR and PC1-3. Correlations between individuals’ scores of the environmental models and the PRSs were further investigated. Lastly, we assessed the predictive ability of PRS of BMI for BMI gain at age 20 years.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding individuals who developed conditions such as diabetes or cardiovascular diseases, or who were under hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after 1 year following the follow-up assessment. Additionally, a 10-fold cross-validation was performed on the validation samples to ensure results were not influenced by differences between the development and validation groups. Further sensitivity analyses included assessing BMI and WHR as continuous variables, as well as restricting the follow-up period between 5 and 9 years.

Ethics statement

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. EPIC was approved by the Ethics Committee of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (ref IEC 14–02), Lyon, France, as well as the local ethics committees of the study centres. All participants provided written informed consent for data collection and storage as well as individual follow-up.

The UK Biobank study was approved by the Northwest Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (reference for UK Biobank is 16/NW/0274) and all participants provided written informed consent to participate in the UK Biobank study. This research has been conducted using the UKB Resource under Application Number 55870.

Role of funders

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation or writing of this report.

Results

The mean age (SD) of the study participants (68% women) at baseline in EPIC was 51 (7.4) years. In UK Biobank, the mean age of the study participants (49% women) at baseline was 55 (7.5) years. Further baseline characteristics are shown in Table S2.

Environmental models

After a median follow-up of 5.3 years (IQR: 4.0–9.0) and 8.8 years (IQR: 5.1–11.1), 66,360 (27.0%) and 25,429 (57.5%) of the individuals experienced BMI and WHR gain, respectively.

After the selection procedure, BMI and WHR gain models included, respectively, 14 and 10 socio-demographic, lifestyle, and dietary predictors. Both models included sex, country, BMI/WHR at baseline, level of education, smoking status, physical activity, consumption of condiments and sauces, and meat and meat products. The BMI gain model further included age at baseline, alcohol intake, and consumption of cake and biscuits, egg and egg products, fish and shellfish, and processed culinary ingredients (NOVA 2) such as table sugar, oils, and salt. The WHR gain model additionally selected consumption of fat and potatoes. Low correlation estimates were found between the predictors selected in each model (Fig. S2). Beta estimates of associations of the selected predictors with BMI and WHR gain including and excluding country are presented in Table S3 and Table S4.

The AUC in the validation sample for BMI gain was 0.687 (95% CI: 0.679–0.696) (Fig. 1 and Table S5). Estimates were similar in men and women (Table S5) and by BMI category (Table S6). The predictive ability of the model decreased after removing country (AUC: 0.642, 95% CI: 0.634–0.651). In contrast, the model performed better in southern (AUC: 0.774, 95% CI: 0.758–0.791) than in northern European regions (AUC: 0.649, 95% CI: 0.638–0.659) (Table S5). For WHR gain, the AUC was 0.752 (95% CI: 0.738–0.766) for the overall population, being similar by sex (Fig. 1 and Table S5). Removing country from the model only marginally affected the predictive ability (AUC: 0.741, 95% CI: 0.727–0.755). The AUC was higher in southern (AUC: 0.766, 95% CI: 0.750–0.782) than in northern European regions (AUC: 0.719, 95% CI: 0.690–0.747) (Table S5).

Fig. 1.

Time-dependent Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the prediction of BMI and WHR gain in a period of 5 years for the environmental model, PRS of BMI, WHR, and body shape phenotypes (PC1-3), and environmental and PRS models combined. Environmental models for BMI and WHR gain were developed in 245,699 and 44,190 individuals, respectively. All models were validated in 29,953 for BMI gain and 6456 for WHR gain. BMI, body mass index; PC, principal component; PRS, polygenic risk score; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

Polygenic risk scores

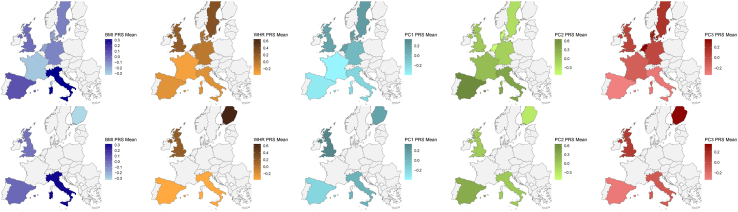

The geographic distribution of the PRS for BMI and PC2 (short, high WHR) showed higher mean values in southern than northern European countries (Fig. 2). In contrast, the geographic distribution of PRS for WHR, PC1 (overall adiposity), and PC3 (tall, high WHR) presented higher mean values in northern rather than in southern European countries (Fig. 2). All patterns were consistently replicated in the 1000 Genomes sample (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Genetic predisposition by European country to BMI (dark blue), WHR (orange), PC1 (light blue), PC2 (green), and PC3 (red) in the EPIC cohort (top) and 1000 Genomes Project (bottom). PRS were developed in 29,953 and 396 EPIC and 1000 Genomes Project individuals, respectively. BMI, body mass index; PC, principal component; PRS, polygenic risk score; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

After a median follow-up of 5.16 years (IQR: 3.58–6.95) and 8.82 years (IQR: 5.38–11.18), 6619 (22.1%) and 3503 (54.3%) of the individuals experienced BMI and WHR gain, respectively.

All PRSs were positively associated with BMI and WHR gain except PC3 PRS that showed an inverse association with BMI gain (Fig. 3 and Table S7). Associations between PRS of PC2 and PC3 and WHR gain were less robust (Fig. 3 and Table S7). Results were consistent in UK Biobank, by sex, European region, and age (threshold at 55 years) (Fig. 3 and Tables S7–S9). Evidence of interactions between PRSs and sex, demographic regions, or sex was not found (Tables S8 and S9).

Fig. 3.

Associations between the polygenic risk scores of BMI, WHR, and body shape phenotypes (PC1—3) and BMI and WHR gain in EPIC (dark purple) and UK Biobank (light purple). Associations were performed in 29,953 for BMI gain and 6456 for WHR gain. BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PC, principal component; PRS, polygenic risk score; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

For BMI and WHR gain, PRSs showed null predictive ability (Fig. 1 and Table S10). Similar results were observed by European regions and by sex (Table S10). PRS for BMI and PC1 showed a stronger predictive ability for BMI gain in early adulthood (∼20 years old) (AUCPRS BMI: 0.618, 95% CI: 0.606–0.631; AUCPRS PC1: 0.601, 95% CI: 0.589–0.613) (Fig. 4 and Table S10). When environmental and PRSs were combined, the predictive ability did not improve for either BMI or WHR gain (Fig. 1 and Table S11).

Fig. 4.

Time-dependent Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the prediction of BMI gain in a period of 5 years in mid-late and early adulthood for the PRS of BMI. Models were validated in 29,953 and 12,386 for mid-late and early adulthood, respectively. BMI, body mass index; PRS, polygenic risk score.

All the sensitivity analyses showed similar results (Table S12). Additionally, individuals’ environmental model scores and PRSs were not correlated (Table S13).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study across eight European countries, we developed and validated environmental prediction models of BMI and WHR gain over a period of 5-years at mid-late adulthood. We combined an environmental prediction model with genetic factors by adding PRSs for BMI, WHR, and 3 body shapes phenotypes. We found that the environmental model achieved a remarkable predictive ability, which could help to risk-stratify middle-aged men and women for adiposity gain. Adding the PRSs for BMI, WHR, or three body shape phenotypes did not improve the predictive ability of the environmental models. In addition to our main findings, we reported differences in the European genetic distribution of these anthropometric traits showing that individuals from northern countries are genetically more susceptible to higher adiposity than from southern European countries when height is not relevant for the trait.

A high-performance adiposity gain prediction model is key to identify individuals at high risk of obesity and, consequently, at high risk of numerous comorbidities and health outcomes. Previous work did not attain sufficient predictive ability (AUC = 0.57),14 or was restricted to a particular country,15 challenging the evaluation of its transferability across Europe. Our work adds insights in the usefulness of genetics for adiposity gain prediction models, suggests relevant environmental predictors, and provides a validated model applicable to European individuals. The improvement in adiposity gain prediction in our study (AUC = 0.69 vs AUC = 0.57) was not due to the addition of a PRS of adiposity related anthropometric traits, but is rather explained by a larger number of candidate predictors (40 vs 21 items) and a larger sample size (245,699 vs 53,758), which may contribute to a more precise characterization of the distinct patterns that lead to adiposity gain, regardless the different dietary patterns across European countries.34 Main differences between predictors included a more refined characterization of diet and the inclusion of country which improved the predictive ability of the BMI gain model (AUCwithout country = 0.64). To avoid individuals that experienced normal weight fluctuations35 being classified as cases and to give a clinical meaning to our analysis,19 we set a threshold of BMI gain at ≥5% than BMI at baseline. Previous studies used a 10% of weight gain threshold (almost two SD of gain phenotypes) which makes the comparison between models less straightforward.14,15

Our results showed a better predictive performance for WHR gain (AUC = 0.75). WHR, as a proxy for body fat distribution, may be less influenced by other factors that can bias the adiposity assessment (e.g., lean mass or height) than BMI. Thus, WHR may not only reflect more precise metabolic characteristics (e.g., hormonal regulation) relevant to adiposity gain, but also be more consistent across populations enhancing adiposity gain prediction. Additionally, our WHR gain model performed better than a previous model for central adiposity gain (proxied by waist circumference adjusted on BMI) among German individuals (AUC = 0.70),15 however, the improved performance of our model is likely explained by differences in study population and design, but not by adding PRS for WHR gain.

A recent study concluded that PRSs performed poorly in individual risk prediction after assessing 926 PRSs for 310 diseases.36 Although our results are in line with this study as we showed that none of the PRSs of adiposity related traits improved the predictive ability of our models, the BMI and PC1 PRSs presented a higher predictive ability for 5-years BMI gain in early adulthood. Therefore, our analysis suggests that the genetic background could have a higher effect on early rather than mid-late adulthood and the PRSs usefulness may be lifetime dependent. This is supported by a twin pairs study which indicated that the role of genetic factors becomes relatively less important with ageing, whereas environmental effects become stronger.37 Also relevant may be the time-varying effect of BMI-related genetic variants. Although both environmental factors38 and PRSs39 are known to influence weight gain trajectories, further evidence highlights differences in the effect sizes of BMI-associated genetic variants across age groups. Specifically, studies have shown that the impact of certain genetic variants on BMI tends to be stronger in younger adults and diminishes in older populations.40 Furthermore, some genetic variants have been associated with changes in BMI and weight over time, indicating a dynamic genetic influence.41 Potential mechanisms underlying these age-dependent effects may involve differences in metabolic rate, hormonal changes, and shifts in body composition that occur with ageing.42 For instance, genetic variants influencing energy expenditure, fat distribution, or appetite regulation may exert their strongest effects during periods of higher metabolic activity, such as early adulthood. However, future research is needed to further elucidate these mechanisms.

The limited improvement in the performance of the prediction models when combining PRS with environmental factors may not be attributed solely to biological considerations. Several methodological and population characteristics could also play a role. These include the possibility of model overfitting due to the large number of predictors, the absence of interaction effects, which were intentionally excluded to maintain a straightforward model, and the unique characteristics of the study population. For instance, the dietary variability among EPIC participants may far exceed their genetic variability, potentially masking any synergistic effects between genetic and environmental factors. Whether the joint contribution of environmental and genetic factors improves the prediction of adiposity gain in early adulthood remains as a question mark and should be further investigated.

The PRSs of BMI, WHR, and three body shape phenotypes were also used to investigate the geographic distribution of genetic predisposition to adiposity across European regions. A previous study depicted genetic patterns for height and BMI showing higher predisposition in northern than southern European countries and an inverse trend, respectively. These contradictory patterns were explained by the process of natural selection on genetic variants for height that are also used to predict BMI.12 Accordingly, our study showed higher genetic predispositions for a higher BMI and higher values of PC2 (short, centrally obese) in southern as compared to northern countries, as height is negatively driving these traits. Our study also reported the distribution of genetically predicted WHR and PC1 which presented higher values in northern than southern countries. The genetic analysis of PC1 identified genetic variants not previously associated with BMI which led to a different genetic characterization of adiposity.5 Therefore, the genetic components of WHR and PC1 could better characterize adiposity regional differences than the BMI genetic component.

The main strength of this work is that our prediction models were developed and validated in a large sample from diverse European countries, broadly representing European regions. The results of our analysis need to be interpreted with the following limitations. First, although standardized protocols to measure anthropometric traits were applied in the different EPIC centres, some of the measurements were self-reported. However, the accuracy of these anthropometric measures was improved by using prediction equations.18 Second, time to achieve BMI and WHR gain was estimated assuming linearity through lifetime as only two measurement points in mid-late adulthood were available for this work. Prior research in a subgroup of EPIC participants suggested that weight gain over an 8-year follow-up period can be well approximated linearly at a population level.43 Third, while models that predict gain in obesity parameters at the distribution's extremes are needed due to their unique metabolic consequences, the cohort in this study is not suitable for training such models. This is because most participants (>70%) have a BMI between 20 and 30 units. Finally, although previous research has shown that weight gain may depend on cultural background,44,45 no information about ethnicity of the study participants was available. To account for it, we used level of education as a proxy of socio-economic position as it has been shown to explain part of the potential weight change differences between ethnicities.46 Additionally, EPIC participants showing extreme genetic differences have been removed from our study sample.

Our environmental prediction models for BMI and WHR gain may be useful to discriminate individuals at high risk of adiposity gain within a period of 5 years at mid-late adulthood. While genetic factors were not relevant at this stage of life, better predictive performance of genetic factors has been observed in early adulthood. These findings suggest a more important role of genetics in early-adulthood adiposity gain and highlight the importance of preventing adiposity gain through modifiable environmental factors in mid-late adulthood.

Contributors

Conceptualisation: R.C.-T., formal analysis: L.P.-N., M.B., and R.C.-T., funding acquisition: H.B., H.F., and R.C.-T., investigation: L.P.-N. and R.C.-T., methodology: L.P.-N., J.A., K.S.-B., and R.C.-T., resources: C.C.D., A.T., R.K., M.B.S., G.M., S.S., P.A., M.-D.C., P.F., M.J.G., A.A, H.F., and R.C.-T., supervision: N.D., M.J.G., H.F., and R.C.-T., validation: L.P.-N. and R.C.-T., visualisation: L.P.-N. and R.C.-T., writing—original draft: L.P.-N. and R.C.-T., and writing–review & editing: all authors, accessed and verified the underlying data: L.P.-N. and R.C.-T. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

EPIC data are available for investigators who seek to answer important questions on health and disease in the context of research projects that are consistent with the legal and ethical standard practices of IARC/WHO and the EPIC centres. The primary responsibility for accessing the data belongs to IARC and the EPIC centres. For information on how to submit an application for gaining access to EPIC data and/or biospecimens, please follow the instructions at https://epic.iarc.fr/access/.

The UK Biobank resource is available to bona fide researchers for health-related research in the public interest. All researchers who wish to access the research resource must register with UK Biobank by completing the registration form in the Access Management System (AMS- https://bbams.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ams/). The UK Biobank data can be provided by UK Biobank Limited pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement.

Summary statistics concerning the anthropometric traits used to derive the PRSs are open access and can be found in https://zenodo.org/records/1251813#.XCLJ7vZKhE4. and in GWAS Catalog.

Declaration of interests

L.M. discloses that an immediate family member holds stocks in Novo Nordisk. The other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all EPIC participants and staff for their outstanding contribution to the study. They further acknowledge the use of data from the EPIC-Bilthoven, EPIC-Utrecht, EPIC-Asturias, EPIC-Norfolk, and of EPIC-Ragusa cohorts, for their contribution and ongoing support to the EPIC Study.

UKB is an open access resource. Bona fide researchers can apply to use the UKB dataset by registering and applying at http://ukbiobank.ac.uk/register-apply/. This research has been conducted using the UKB Resource under Application Number 55870 and we express our gratitude to the participants and those involved in building the resource.

Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organisation, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organisation.

This work was supported by the French National Cancer Institute (INCA_N°2019-176) 1220 and the German Research Foundation (BA 5459/2-1). R.C.T. was supported by the Miguel Servet Program CP21/00058, funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and co-funded by the European Union, and is part of the AGAUR SGR 01366.

The coordination of EPIC-Europe is financially supported by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and also by the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London which has additional infrastructure support provided by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

The national cohorts are supported by: Danish Cancer Society (Denmark); Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, Institut Gustave-Roussy, Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale (MGEN), Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), French National Research Agency (ANR, reference ANR-10-COHO-0006), French Ministry for Higher Education (subsidy 2102918823, 2103236497, and 2103586016) (France); German Cancer Aid, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbruecke (DIfE), Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (Germany); Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro-AIRC-Italy, Italian Ministry of Health, Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), Compagnia di San Paolo (Italy); “Europe against Cancer” Programme of the European Commission (DG SANCO); Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), (The Netherlands); UiT The Arctic University of Norway; Health Research Fund (FIS)–Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Regional Governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia and Navarra, and the Catalan Institute of Oncology–ICO (Spain); Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Research Council and County Councils of Skåne and Västerbotten (Sweden); Cancer Research UK (C864/A14136 to EPIC-Norfolk; C8221/A29017 to EPIC-Oxford), Medical Research Council (MR/N003284/1, MC-UU_12015/1 and MC_UU_00006/1 to EPIC-Norfolk; MR/Y013662/1 to EPICOxford) (United Kingdom).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105510.

Contributor Information

Heinz Freisling, Email: freislingh@iarc.who.int.

Robert Carreras-Torres, Email: rcarreras@idibgi.org.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.World Obesity Federation . 2022. World obesity atlas 2022. London. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2024. Fact sheet: obesity and overweight.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulit S.L., Stoneman C., Morris A.P., et al. Meta-Analysis of genome-wide association studies for body fat distribution in 694 649 individuals of European ancestry. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locke A.E., Kahali B., Berndt S.I., et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518 doi: 10.1038/nature14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peruchet-Noray L., Sedlmeier A.M., Dimou N., et al. Tissue-specific genetic variation suggests distinct molecular pathways between body shape phenotypes and colorectal cancer. Sci Adv. 2024;10 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adj1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timpson N.J., Greenwood C.M.T., Soranzo N., Lawson D.J., Richards J.B. Genetic architecture: the shape of the genetic contribution to human traits and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19 doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mars N., Koskela J.T., Ripatti P., et al. Polygenic and clinical risk scores and their impact on age at onset and prediction of cardiometabolic diseases and common cancers. Nat Med. 2020;26 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0800-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham G., Havulinna A.S., Bhalala O.G., et al. Genomic prediction of coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2016;37 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khera A.V., Chaffin M., Aragam K.G., et al. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat Genet. 2018;50 doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mavaddat N., Michailidou K., Dennis J., et al. Polygenic risk scores for prediction of breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seibert T.M., Fan C.C., Wang Y., et al. Polygenic hazard score to guide screening for aggressive prostate cancer: development and validation in large scale cohorts. BMJ. 2018;360 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson M.R., Hemani G., Medina-Gomez C., et al. Population genetic differentiation of height and body mass index across Europe. Nat Genet. 2015;47 doi: 10.1038/ng.3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilhjálmsson B.J., Yang J., Finucane H.K., et al. Modeling linkage disequilibrium increases accuracy of polygenic risk scores. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steffen A., Sørensen T.I.A., Knüppel S., et al. Development and validation of a risk score predicting substantial weight gain over 5 years in middle-aged European men and women. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachlechner U., Boeing H., Haftenberger M., et al. Predicting risk of substantial weight gain in German adults-A multi-center cohort approach. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riboli E. The EPIC project: rationale and study design. European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26 doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.s6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riboli E., Hunt K., Slimani N., et al. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5 doi: 10.1079/phn2002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haftenberger M., Lahmann P., Panico S., et al. Overweight, obesity and fat distribution in 50- to 64-year-old participants in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) Public Health Nutr. 2002;5 doi: 10.1079/phn2002396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens J., Truesdale K.P., McClain J.E., Cai J. The definition of weight maintenance. Int J Obes. 2006;30 doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan L.M., Massaro J.M., D'Agostino R.B. Presentation of multivariate data for clinical use: the Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat Med. 2004;23 doi: 10.1002/sim.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLernon D.J., Giardiello D., Van Calster B., et al. Assessing performance and clinical usefulness in prediction models with survival outcomes: practical guidance for Cox proportional hazards models. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176 doi: 10.7326/M22-0844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uno H., Cai T., Tian L., Wei L.J. Evaluating prediction rules for t-year survivors with censored regression models. J Am Stat Assoc. 2007;102 doi: 10.1198/016214507000000149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung H., Chiang C.T. Optimal composite markers for time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves with censored survival data. Scand J Stat. 2010;37 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9469.2009.00683.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamarudin A.N., Cox T., Kolamunnage-Dona R. Time-dependent ROC curve analysis in medical research: current methods and applications. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0332-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanche P., Dartigues J.F., Jacqmin-Gadda H. Estimating and comparing time-dependent areas under receiver operating characteristic curves for censored event times with competing risks. Stat Med. 2013;32 doi: 10.1002/sim.5958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Team RC R: a language and environment for statistical computing v. 3.6. 1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2019) Sci Rep. 2021:11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.RStudio Team . PBC; Boston, MA: 2022. RStudio: integrated development environment for R. RStudio.http://www.rstudio.com/ URL. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Auton A., Abecasis G.R., Altshuler D.M., et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526 doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sudlow C., Gallacher J., Allen N., et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bycroft C., Freeman C., Petkova D., et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562 doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ried J.S., Jeff J.M., Chu A.Y., et al. A principal component meta-analysis on multiple anthropometric traits identifies novel loci for body shape. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedlmeier A.M., Viallon V., Ferrari P., et al. Body shape phenotypes of multiple anthropometric traits and cancer risk: a multi-national cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2023;128 doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-02071-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Privé F., Albiñana C., Arbel J., Pasaniuc B., Vilhjálmsson B.J. Inferring disease architecture and predictive ability with LDpred2-auto. Am J Hum Genet. 2023;110:2042–2055. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slimani N., Fahey M., Welch A., et al. Diversity of dietary patterns observed in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) project. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5 doi: 10.1079/phn2002407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orsama A.L., Mattila E., Ermes M., Van Gils M., Wansink B., Korhonen I. Weight rhythms: weight increases during weekends and decreases during weekdays. Obes Facts. 2014;7 doi: 10.1159/000356147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hingorani A.D., Gratton J., Finan C., et al. Performance of polygenic risk scores in screening, prediction, and risk stratification: secondary analysis of data in the Polygenic Score Catalog. BMJ Medicine. 2023;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjmed-2023-000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silventoinen K., Jelenkovic A., Sund R., et al. Differences in genetic and environmental variation in adult BMI by sex, age, time period, and region: an individual-based pooled analysis of 40 twin cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.153643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silventoinen K., Kaprio J. Genetics of tracking of body mass index from birth to late middle age: evidence from twin and family studies. Obes Facts. 2009;2 doi: 10.1159/000219675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahl A.K., Reynolds C.A., Fall T., Magnusson P.K.E., Pedersen N.L. Multifactorial analysis of changes in body mass index across the adult life course: a study with 65 years of follow-up. Int J Obes. 2014;38 doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winkler T.W., Justice A.E., Graff M., et al. The influence of age and sex on genetic associations with adult body size and shape: a large-scale genome-wide interaction study. PLoS Genet. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venkatesh S.S., Ganjgahi H., Palmer D.S., et al. Characterising the genetic architecture of changes in adiposity during adulthood using electronic health records. Nat Commun. 2024;15:5801. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49998-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer A.K., Jensen M.D. Metabolic changes in aging humans: current evidence and therapeutic strategies. J Clin Invest. 2022;132 doi: 10.1172/JCI158451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Ruesten A., Steffen A., Floegel A., et al. Trend in obesity prevalence in European adult cohort populations during follow-up since 1996 and their predictions to 2015. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burke G.L., Bild D.E., Hilner J.E., Folsom A.R., Wagenknecht L.E., Sidney S. Differences in weight gain in relation to race, gender, age and education in young adults: the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Ethn Health. 1996;1 doi: 10.1080/13557858.1996.9961802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan M.M., Bush T., Lovejoy J.C., et al. Race differences in predictors of weight gain among a community sample of smokers enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of a multiple behavior change intervention. Prev Med Rep. 2021;21 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chor D., Faerstein E., Kaplan G.A., Lynch J.W., Lopes C.S. Association of weight change with ethnicity and life course socioeconomic position among Brazilian civil servants. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.