Abstract

The hammerhead ribozyme is generally accepted as a well characterized metalloenzyme. However, the precise nature of the interactions of the RNA with metal ions remains to be fully defined. Examination of metal ion-catalyzed hammerhead reactions at limited concentrations of metal ions is useful for evaluation of the role of metal ions, as demonstrated in this study. At concentrations of Mn2+ ions from 0.3 to 3 mM, addition of the ribozyme to the reaction mixture under single-turnover conditions enhances the reaction with the product reaching a fixed maximum level. Further addition of the ribozyme inhibits the reaction, demonstrating that a certain number of divalent metal ions is required for proper folding and also for catalysis. At extremely high concentrations, monovalent ions, such as Na+ ions, can also serve as cofactors in hammerhead ribozyme-catalyzed reactions. However, the catalytic efficiency of monovalent ions is extremely low and, thus, high concentrations are required. Furthermore, addition of monovalent ions to divalent metal ion-catalyzed hammerhead reactions inhibits the divalent metal ion-catalyzed reactions, suggesting that the more desirable divalent metal ion–ribozyme complexes are converted to less desirable monovalent metal ion–ribozyme complexes via removal of divalent metal ions, which serve as a structural support in the ribozyme complex. Even though two channels appear to exist, namely an efficient divalent metal ion-catalyzed channel and an inefficient monovalent metal ion-catalyzed channel, it is clear that, under physiological conditions, hammerhead ribozymes are metalloenzymes that act via the significantly more efficient divalent metal ion-dependent channel. Moreover, the observed kinetic data are consistent with Lilley’s and DeRose’s two-phase folding model that was based on ground state structure analyses.

INTRODUCTION

The past few years have seen a considerable increase in our understanding of catalysis by naturally occurring ribozymes (1–15). The biological functions of RNA molecules depend upon their adoption of appropriate three-dimensional structures. RNA structure has a very important electrostatic component, which results from the presence of charged phosphodiester bonds, and metal ions are almost always required for stabilization of the folded structures (16,17). Catalytic RNAs provide useful systems for studies of ion-induced transitions in RNA structure because folding can be correlated with functional activity, which can be monitored as the rate of a particular substrate cleavage. Naturally existing hammerhead ribozymes were originally identified in some RNA viruses and they act in cis during viral replication by the rolling circle mechanism. The ribozymes have been engineered such that they act in trans against other RNA molecules and catalyze cleavage of phosphodiester bonds at a specific site to generate products with a 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate and a 5′-hydroxyl group (18–21).

Experiments with ribozymes in vitro demonstrated that divalent metal cations are required for their activity (22–34). These observations were consistent with the view that ribozymes are metalloenzymes that require divalent cations for catalysis and they suggested, moreover, that all ribozymes might operate by a basically similar mechanism. In the case of hammerhead ribozymes, a large body of evidence indicates that the P9/G10.1 site binds a metal ion with high affinity (33–45), with other metal ion-binding sites being located around the G5 nucleobase and A13 phosphate near the site of cleavage (46,47). Other more recent experiments have indicated that some ribozymes, for example hairpin ribozymes, can catalyze reactions by mechanisms that do not involve divalent metal ions (15,48–51). Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that hammerhead ribozymes are active in the presence of very high concentrations of monovalent cations (52–54). These observations raise the possibility that the hammerhead ribozyme should not be classified as a metalloenzyme and the possibility that a nucleobase of the ribozyme might act as the catalyst (52–54).

Our own analysis, based on kinetic solvent isotope effects, demonstrated that proton transfer occurs in reactions catalyzed by a 32mer hammerhead ribozyme (R32, Fig. 1A) in the presence of high concentrations of monovalent NH4+ ions without metal ions (55), whereas no such proton transfer occurs in reactions catalyzed by R32 in the presence of divalent metal ions (3,5,56). This conclusion was based on the fact that the intrinsic isotope effect for NH4+-mediated R32-catalyzed reactions was two, whereas the corresponding value for Mg2+-mediated reactions was one. These results could be explained by the mechanism shown in Figure 1B. In the case of NH4+-mediated R32-catalyzed reactions, an NH4+ ion neutralizes the developing negative charge in the transition state by transferring a proton to the leaving 5′-oxygen. In contrast, in the case of the Mg2+-mediated R32-catalyzed reactions, a Mg2+ ion neutralizes the developing negative charge in the transition state by coordinating directly with the leaving 5′-oxygen, as shown in Figure 1B. These kinds of multiple channels have also been reported in the case of HDV genomic ribozyme-catalyzed reactions (57).

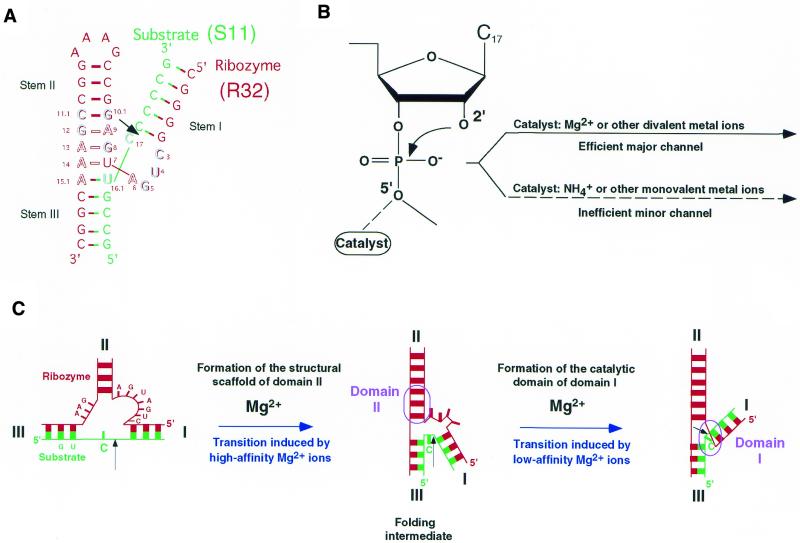

Figure 1.

Secondary structures, proposed two channels and folding scheme of hammerhead ribozymes. (A) The Y- or γ-shaped secondary structures of the hammerhead ribozyme (red; R32) and substrate (green; S11) used in this study. The black arrow indicates the cleavage site. Outlined letters are conserved bases. (B) Schematic representation of the proposed effects of monovalent and divalent ions at the cleavage phosphate and on the reaction that the ribozyme catalyzes. Two different channels are indicated. The major channel involves divalent metal ions working as a catalyst at the leaving 5′-oxygen, the minor channel involves monovalent ions working as the catalyst. Another catalyst for deprotonation of the 2′-hydroxyl group is omitted. (C) The two-stage folding scheme for the hammerhead ribozyme, as proposed by Lilley’s group (58–61). The ribozyme and its substrate are colored in red and green, respectively. The black arrow indicates the cleavage site. The scheme consists of two steps to generate the Y- or γ-shaped ribozyme–substrate complex. The higher affinity of Mg2+ is related to formation of domain II (structural scaffold, non-Watson–Crick pairings between G12·A9, A13·G8 and A14·U7 forming a coaxial stack between helices II and III that runs through G12A13A14) and the lower affinity of Mg2+ to formation of domain I (catalytic domain, formation by the sequence C3U4G5A6 and C17 with rotation of helix I into the same quadrant as helix II) (59).

In the present study of reaction kinetics, we observed an unusual phenomenon when we analyzed the activity of a hammerhead ribozyme as a function of the concentration of Na+ ions on a background of a low concentration of either Mn2+ or Mg2+ ions. At lower concentrations of Na+ ions, Na+ ions had an inhibitory effect on ribozyme activity, whereas at higher concentrations, Na+ ions had a rescue effect. We propose that these observations can be explained if we accept the existence of two kinds of metal-binding site that have different affinities. Our data also support the ‘two-phase folding theory’ (58–61; Fig. 1C), in which divalent metal ions in the ribozyme–substrate complex have lower and higher affinities, as proposed by Lilley’s group on the basis of their observations of ribozyme complexes in the ground state. Our data also warn us of the importance of analyzing ribozyme reactions in the presence of NaCl since Na+ ions can influence the rate of cleavage in divalent metal ion-mediated ribozyme-catalyzed reactions. We demonstrate herein that our kinetic data are pertinent to the ‘two-phase folding theory’, which is based on results obtained by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and other techniques, and that there exist at least two channels, namely a divalent metal ion-dependent channel and a divalent metal ion-independent channel. Moreover, at physiological concentrations of divalent metal ions, the divalent metal ion-dependent channel is the major channel of hammerhead ribozyme-catalyzed reactions. Thus, the hammerhead ribozyme can be classified as a true metalloenzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of the hammerhead ribozyme and substrate

The ribozyme (R32) and its substrate (S11), with the sequences shown in Figure 1A, were synthesized on a DNA/RNA synthesizer (model 394; PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using phosphoramidic chemistry with 2′-t-butyldimethylsilyl protection. Chemically synthesized oligonucleotides were deprotected in 25% ammonia/ethanol (3:1) solution at 55°C for 8 h, evaporated to dryness, redissolved in 1 ml of 1 M tetrabutylammonium fluoride (Aldrich) at 25°C for 12 h and, after addition of 1 ml of water, desalted on a gel filtration column (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Fully deprotected oligonucleotides were purified by gel electrophoresis in 20% polyacrylamide containing 7 M urea. Corresponding bands were excised and extracted from the gel with water. The oligonucleotides were recovered by ethanol precipitation and then desalted using a gel filtration column (TSK-GEL G3000PW; Tosoh, Japan) by HPLC with ultrapure water.

S11 was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase (Takara, Japan). The 5′-32P-labeled S11 was purified in a 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea and then purified by standard procedures with desalting using a gel filtration column (NAP‘-10 column; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) (36).

Measurements of the ribozyme reactions

All R32-catalyzed reactions were performed under single-turnover conditions, in a solution that contained a trace mount of 5′-32P-labeled S11 and 50 mM MES buffer at pH 6.0 and 28°C. The pH of all 1.25× pre-stock MES buffers containing appropriate metal ions (metal ion buffer) were adjusted with KOH/HCl to pH 6.0 at 28°C and it was confirmed that these buffers showed the appropriate pH under the reaction conditions. Reactions were initiated by addition of the ribozyme to a mixture of metal ion buffer and substrate and aliquots were removed from the reaction mixture at appropriate intervals. These aliquots were then mixed with an equal volume of a solution that contained 100 mM MES (pH 5.8), 100 mM EDTA, 7 M urea, 0.1% xylene cyanol and 0.1% bromophenol blue. Uncleaved substrates and 5′-cleaved products were separated on a 20% polyacrylamide gel that contained 7 M urea. The extent of each cleavage reaction was quantified using an image analyzer (Storm 830; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Reaction conditions

The catalytic activity of hammerhead ribozymes increases with an increase in the concentration of divalent metal ions, and studies of the kinetics in vitro are usually performed with an excess of metal ions at 10 mM or more. We reported previously that, even at lower concentrations, divalent metals can still support catalysis and that Mn2+ is more effective than Mg2+ in initiating ribozyme-catalyzed reactions (28,62). Metal ions at a low concentration can be easily absorbed by added ribozymes and, in our titration studies, unless otherwise noted, we mainly added different amounts of ribozyme (R32) to a solution of 0.3 mM Mn2+ ions at pH 6.0 under single-turnover conditions.

We chose this low pH in order to slow down the R32-catalyzed reactions and to improve the accuracy of our kinetic measurements under single-turnover conditions. In this work, the ribozyme activities were expressed as a quasi-rate constant (% min–1). One might think that there is a risk that estimating a single point would underestimate the rates, especially for the faster reactions. However, we took care of these concerns and all of the experimental points were collected at a fixed early time in the reaction, not near end-points. Thus, although we did not calculate the observed rate, kobs (min–1), in each case, the resulting profiles can be used to check and judge whether inhibition or enhancement occurs upon addition of a second metal ion. In some cases, we confirmed that the profiles based on the quasi-rate constant (% min–1) are basically the same as those that were based on the observed rate constant (kobs).

Inhibition of the ribozyme-catalyzed reaction by the R32 ribozyme

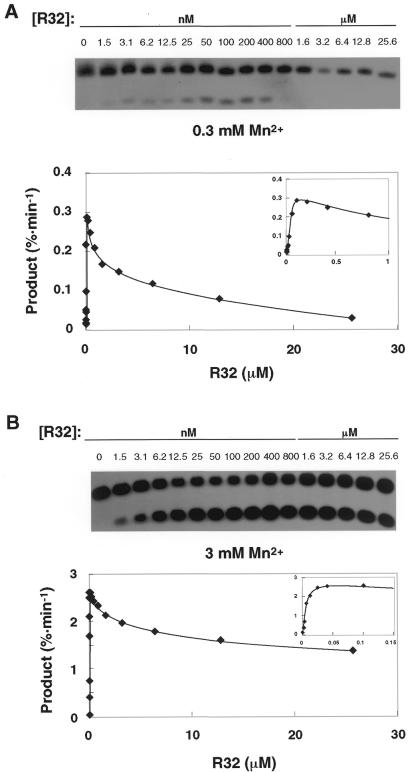

We performed titrations in the presence of a low concentration of Mn2+ ions (0.3 or 3 mM), adding different concentrations of R32 (0.0015–25.6 µM) to a reaction mixture that contained the substrate (S11) and Mn2+ ions (Fig. 2A). The activity of the hammerhead ribozyme increased linearly, as expected, until the concentration reached ∼0.1 µM, when the activity reached a maximum. Further increases in the amount of R32 inhibited cleavage activity. Thus, in the presence of 0.3 mM Mn2+ ions at ∼26 µM R32 the ribozyme exhibited a significant loss of catalytic activity (Fig. 2A). An increase in the concentration of Mn2+ ions from 0.3 to 3 mM increased the maximum activity of R32 (Fig. 2B). A similar pattern, an increase and a decease in activity, was also observed in the presence of 3 mM Mn2+ ions.

Figure 2.

Titration of ribozyme-mediated activity. The cleavage rate is plotted as a function of the concentration of the hammerhead ribozyme, which was varied from 1.5 nM to 25.6 µM. (Inset) Data for low concentrations of ribozyme. (A) Incubation for 90 min in the presence of 0.3 mM Mn2+ ions. (B) Incubation for 30 min in the presence of 3 mM Mn2+ ions.

The observed inhibition of the ribozyme-catalyzed reaction by the ribozyme itself suggests that more than an optimal number of divalent metal ions is required for proper folding of the ribozyme and catalysis (see below). When the concentration of R32 exceeds the concentration that can be accommodated by that number of metal ions, additional R32 starts to withdraw structural and catalytic metal ions from the optimal R32–Mn2+ ion complexes, with a resultant decrease in their activity. In other words, a hammerhead ribozyme with a pocket(s) that traps metal ions can function as a kind of chelator of divalent metal ions.

Titration of the ribozyme-catalyzed reaction with monovalent cations

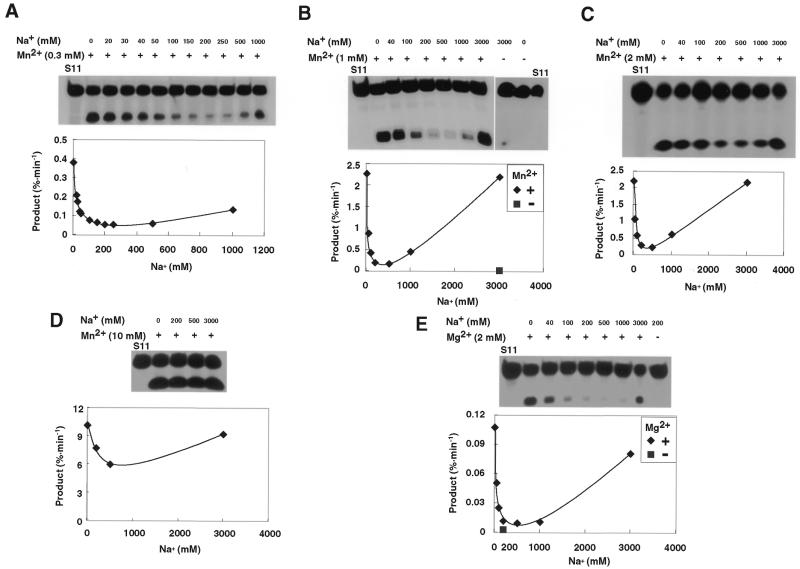

To examine the effects of monovalent cations on the reaction catalyzed by R32, we performed a titration experiment with NaCl in the presence of a low concentration of Mn2+ ions. The concentration of Na+ ions was varied from 0 to 1000 or 3000 mM on a background of 0.3–10 mM MnCl2 or on a background of 2 mM MgCl2. The results in Figure 3 show that, at lower concentrations of Na+ ions up to ∼200 mM, ribozyme activity decreased linearly, reaching a minimum. In general, the extent of inhibition by Na+ ions was greater when the concentration of divalent metal ions was lower. At significantly higher concentrations of Na+ ions, the reduced activity was restored. As shown in Figure 3B, the R32-catalyzed reaction proceeds in the presence of 3 M Na+ ions and the absence of Mn2+ ions. However, in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+ ions on a background of 3 M Na+ ions, ribozyme activity increases ∼300-fold, and the increase is mediated by the presence of 1 mM Mn2+ ions. The results of only a single set of experiments are shown in Figure 3. However, three independent sets of experiments were performed by three independent individuals using their own independently prepared reagents and the results were almost identical in each case. Beside these experiments, we checked the profile of kobs versus the concentration of Na+ ions on a background of 1 mM Mn2+ ions under the same conditions as for Figure 3B, in which each observed rate constant was calculated from seven points by fitting to a pseudo-first order equation (data not shown). This profile was basically the same as that shown in Figure 3B. The reversed bell-shaped titration curves were also observed in Bis–Tris buffers whose pH was adjusted by HCl (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of the monovalent Na+ cation on the ribozyme reaction in the presence of the divalent cation Mn2+ or Mg2+. The concentration of ribozyme was 120 nM and the concentration of Na+ was varied from 0 to 1000 or 3000 mM. (A) Incubation for 90 min in the presence of 0.3 mM Mn2+ ions at various concentrations of Na+ ions. (B) Incubation for 15 min in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+ ions at various concentrations of Na+ ions or no Mn2+ ions at 3000 mM Na+ ions. (C) Incubation for 15 min in the presence of 2 mM Mn2+ ions at various concentrations of Na+ ions. (D) Incubation for 5 min in the presence of 10 mM Mn2+ ions at various concentrations of Na+ ions. (E) Incubation for 240 min in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ ions at various concentrations of Na+ ions or no Mg2+ ions at 200 mM Na+ ions.

We observed a similar phenomenon when we performed titration studies in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ ions, although the effects were less marked (Fig. 3E). Thus, when divalent ions, such as Mg2+ and Mn2+ ions, coexist with monovalent ions, as occurs under physiological conditions, divalent metal ions should be more effective cofactors than monovalent ions in ribozyme-catalyzed reactions (Fig. 3B and E). However, paradoxically, it appears from our data that monovalent ions might suppress the maximum intrinsic cleavage activity of hammerhead ribozymes in vivo because of the inhibitory effects of Na+ ions (intracellular concentrations of Mg2+ and monovalent ions such as K+/Na+ ions have been estimated to be ∼2–3 and 100–200 mM, respectively).

The role of metal ions in hammerhead ribozyme-catalyzed reactions

The structures of hammerhead ribozymes change with changes in concentrations of metal ions (58–61,63,64). The results presented above show that the reaction mediated by R32 is strongly dependent on the ratio of metal ions to ribozymes. It is likely that a series of intermediates exists whose levels depend on the number and nature of the metal ions in the reaction mixture. The hammerhead ribozyme R32 appears to catalyze the efficient cleavage of RNA only if the number of bound divalent metal ions exceeds a threshold value, as indicated in Figure 2. When further ribozyme molecules are added, they competitively bind metal ions to form active intermediates and free metal ions in solution are consumed as more ribozymes are added. When there are insufficient free metal ions, the newly added ribozymes steal from active ribozymes the bound metal ions that have been playing a structural and/or catalytic role, thereby inhibiting the activity of the previously active ribozymes (Fig. 2). Clearly, divalent metal ions play a significant role in promoting folding of the hammerhead ribozyme into its active conformation and in its catalytic function.

While hammerhead ribozymes have generally been characterized as typical metalloenzymes (22–34), this characterization has become somewhat ambiguous. Recent findings indicate that hammerhead ribozymes might operate via a variety of cleavage mechanisms, depending on the conditions of the reaction. It is clear from our discussion that for active structural folding the hammerhead ribozyme requires divalent cations at levels above a certain molar ratio. RNA molecules are extended polyanions that are not easily folded upon themselves unless substantial charge neutralization occurs. Divalent metal ions are effective counterions for neutralization of charges on phosphate groups and they occupy specific metal-binding sites. To clarify the contribution of divalent metal ions to RNA folding, we performed titrations in the presence of monovalent Na+ cations. Our titration studies showed that, instead of having a coordinated stimulatory effect on cleavage activity, Na+ ions at lower concentrations inhibited divalent ion-mediated ribozyme reactions. Hendry and McCall (65) also reported the existence of an inhibitory effect of Na+ ions in the presence of a low concentration of Mg2+ ions in a hammerhead ribozyme reaction. The EPR spectroscopic measurements of DeRose’s group revealed the numbers of Mn2+ ions in a hammerhead ribozyme–substrate complex and the affinities of Mn2+ ions for the ribozyme in these complexes in the presence of different concentrations of NaCl (66). They reported that addition of Na+ ions caused the release of Mn2+ ions that had been bound to the ribozyme complex and suggested that it is likely that non-specific charge screening interactions can be satisfied by either monovalent or divalent cations (see below for details).

At a given concentration, divalent metal ions should be better able than monovalent cations to bridge separate strands of RNA and to twist them by binding to anionic groups while, at the same time, neutralizing negative charge. When, at lower concentrations, monovalent cations competitively neutralize the charges on RNA, replacing divalent metal ions, they are unable to maintain the optimal active conformation of the ribozyme that is supported by divalent cations. Higher concentrations of monovalent cations can rescue the reaction because, at higher concentrations, Na+ ions might not only occupy sites that bind divalent ions but might also occupy other sites within the ribozyme, providing sufficient positive charge and producing an active structure. The reversed bell-shaped titration curves obtained with Na+ ions demonstrate that Na+ ions can also maintain R32 in an active configuration.

Comparative analysis of present and previous results

The reversed bell-shaped titration curves can be explained in terms of metal ion-dependent changes in the ribozyme structure (58–61), metal ion affinities for the ribozyme complex (66) and the existence of two reaction channels (see below for detailed discussion).

Lilley’s group analyzed the global structure of the hammerhead ribozyme–substrate complex in terms of ion-induced folding transitions by electrophoresis in non-denaturing gels and FRET (58–60). They detected two sequential ion-dependent transitions (Fig. 1C). The first transition was the formation of domain II, resulting in coaxial stacking of helices II and III, which was induced by binding of a higher affinity Mg2+ ion(s) (with a lower, submillimolar dissociation constant, Kd) to the ribozyme–substrate complex. The second transition was formation of the catalytic domain [folding of domain I, consisting of the sequence C3U4G5A6 (‘uridine turn’) and the cleavage site C17] of the ribozyme with resultant movement of stem I toward stem II, which is induced by binding of a lower affinity Mg2+ ion(s) (with a higher, millimolar Kd). Such ion-induced folding of the ribozyme was also confirmed by recent NMR analysis (61). It is assumed that the ribozyme reaction proceeds in accordance with this scheme, with completion of the second transition by formation of domain I and subsequent chemical cleavage of the scissile phosphodiester bond, with or without addition of a further divalent metal ion(s).

DeRose’s group analyzed the Mn2+-binding properties of hammerhead ribozyme–substrate complexes by EPR (66). They found two classes of metal-binding sites with higher and lower affinity, respectively, by monitoring the number of bound Mn2+ ions per hammerhead ribozyme–substrate complex at various concentrations of NaCl. They observed, in the presence of a constant ion concentration of Mn2+ ions, a sudden decrease in the number of bound low affinity Mn2+ ions at a lower concentration of NaCl, followed by a slow decrease in or a plateau value of the number of bound high affinity Mn2+ ions at a higher concentration of NaCl. For example, in the absence of NaCl and in the presence of either 0.3 or 1 mM Mn2+ ions, the number of bound Mn2+ ions per hammerhead ribozyme–substrate complex was approximately 14. Addition of NaCl at lower concentrations (0–60 mM) reduced this number dramatically, to approximately 7. As the concentration of NaCl was increased above 60 mM, the number of bound Mn2+ ions decreased slowly (on a background of 0.3 mM Mn2+ ions) down to 1 or remained constant (on a background of 1 mM Mn2+ ions) at 7. These results indicate that there are two types of bound Mn2+ ion with different affinities for the ribozyme–substrate complex and that the bound Mn2+ ion(s) with lower affinity can easily be removed from the complex by Na+ ions at lower concentrations.

Our data indicate that ribozyme activity in a low concentration of divalent metal ions decreases dramatically at lower concentrations of NaCl (Fig. 3). This inhibitory effect of NaCl can be explained on the basis of the data from DeRose’s group described above. The Na+ ions remove Mn2+ ions from the lower affinity site(s) of the ribozyme–substrate complex, which is somehow involved in ribozyme activity. When Lilley’s group used Mg2+ ions in their NMR analysis, they noticed that the apparent Kd for the lower affinity Mg2+ ions depended on the concentration of Na+ ions. An increase in the background concentration of NaCl from 10 to 50 mM weakened the affinity of Mg2+ ions for the complex. Their observations also reconcile with the observed inhibition by Na+ ions, in this study, with competitive removal of Mg2+/Mn2+ ions from the ribozyme–substrate complex. Thus, inhibition by Na+ ions is, in general, weaker when higher concentrations of divalent metal ions are present in the reaction mixture (Fig. 3A–D).

As the concentration of NaCl is increased after ribozyme activity has reached a minimum, the activity of the ribozyme is restored (Fig. 3). This rescue cannot be explained in terms of the number of bound Mn2+ ions since the number does not increase at higher concentrations of NaCl, according to DeRose’s group, as described above. It is likely that at higher concentrations, Na+ ions can work to fold the complex into the active structure and, as a result, more efficient Mn2+ ions, even at limited concentrations, can work as the catalyst (see below for details). As we would anticipate from the structural role and inefficient catalytic activity of Na+ ions, several groups have reported that ribozyme-mediated cleavage reactions can occur even in the absence of divalent metal ions provided that the concentration of monovalent ions, such as Na+ ions, is extremely high (52–54).

As shown in Figure 3, the cleavage reaction is clearly much more efficient in the presence of a small number of divalent metal ions and a high concentration of NaCl than in the presence of the same high concentration of NaCl without any divalent metal ions. This difference in activity can be explained by the existence of two channels in the reaction. In the presence of Mn2+ ions, the efficient major channel is operative (Fig. 1B), with a Mn2+ ion(s) working as the catalyst. On the other hand, in the presence of only Na+ ions, the inefficient minor channel is operative, with an inefficient Na+ ion(s) working as the catalyst (Fig. 1B; 55). In the presence of only inefficient Na+ ions, high concentrations of the ions support active folding of the complex and the ribozyme reaction proceeds by the minor channel. As a result, the activity is very low. In the presence of both Na+ and Mn2+ ions, the reaction proceeds by the major channel. Therefore, the activity is significantly higher than that in the presence of only Na+ ions. The activity in the major channel can change, depending on the concentration of Na+ ions. This idea, the existence of two channels in hammerhead ribozyme reactions, is strongly supported by different experimental data based on analysis of intrinsic isotope effects (55). On the basis of kinetic solvent isotope effects, proton transfer occurs in reactions catalyzed by the hammerhead ribozyme in the presence of high concentrations of monovalent NH4+ ions without metal ions, whereas no such proton transfer occurs in reactions catalyzed by R32 in the presence of divalent metal ions (3,5,56). Furthermore, a multiple channel model has also been proposed for reactions catalyzed by a HDV genomic ribozyme in which a base catalyst or its equivalence changes according to the surrounding conditions of the ribozyme (57).

In Lilley’s two-phase folding model (Fig. 1C), the values of Kd for Mg2+ ions are ∼100 µM and 1 mM (59). DeRose’s values of Kd for binding of Mn2+ ions to the ribozyme complex are 4 µM and 0.5 mM even in the presence of 0.1 M NaCl (66). Since Mn2+ ions have higher affinity than Mg2+ ions for the ribozyme–substrate complex (67), it is reasonable that the two Kd values for Mn2+ ions should be smaller than those for Mg2+ ions by about one order of magnitude under similar conditions. Thus, it is possible that the higher affinity Mn2+ ions contribute to the formation of domain II, as do the higher affinity Mg2+ ions (induction of the first transition) and that the lower affinity Mn2+ ions contribute to the formation of domain I, as do the lower affinity Mg2+ ions (induction of the second transition). Lilley’s group pointed out that at a relatively low concentration (50 mM), NaCl cannot even promote the formation of domain II (on the basis of an analysis by non-denaturing gel electrophoresis methods; 58). However, our kinetic data suggest that high concentrations of NaCl can induce further folding (the second folding transition) of the first folding intermediate, which is most probably generated by the limited number of divalent ions, to yield the final active form, namely the Y- or γ-shaped hammerhead ribozyme complex. If this is the case, formation of domain I should be detectable by gel electrophoresis or FRET at a low concentration of divalent metal ions, such as Mg2+ or Mn2+ ions, and a high concentration of monovalent ions, such as Na+ ions.

Taken together, the data suggest the following mechanism. In the presence of a small amount of Mn2+ or Mg2+ ions and the absence of Na+ ions, the Mn2+ or Mg2+ ions act not only as a structural support but also as the catalyst in the ribozyme reaction. Upon addition of a low concentration of Na+ ions, the Mn2+ or Mg2+ ions that had functioned as a structural support are forced out of the ribozyme complex, with a resultant reduction in ribozyme activity due to disruption of the active conformation. Addition of Na+ ions at a higher concentration converts the disrupted ribozyme complex to an active conformation. In the presence of Mn2+ or Mg2+ ions, it is these divalent ions, rather than Na+ ions, that always act as the real catalyst(s), no matter what the concentration of Na+ ions. Moreover, our observed kinetic data are consistent with the two-phase folding model based on the ground-state structures analyzed by Lilley’s and DeRose’s groups (58–61,66,67).

CONCLUSION

Previous observations suggested that metal ions, in particular divalent cations, might play several roles in catalysis by ribozymes. A metal ion coordinated to a hydroxide might activate a hydroxyl or water nucleophile by deprotonation or, alternatively, a divalent ion might directly coordinate with the nucleophilic oxygen, rendering the oxygen more susceptible to deprotonation by hydroxide ions. Metal ions might also stabilize the transition state by direct inner sphere coordination with the pentavalent scissile phosphate group and might stabilize the leaving group by protonating or directly coordinating with the leaving oxygen atom. Finally, metal ions might also stabilize the transition state structure electrostatically by donating positive charge (68).

Current research is reshaping basic theories about the roles of metal ions in reactions catalyzed by hammerhead ribozymes and such ribozymes are no longer viewed as true metalloenzymes. The activity of a hammerhead ribozyme in the presence of monovalent ions has been used to argue against the hypothesis that metal ions could induce the deprotonation of 2′-OH or stabilize the leaving group directly or indirectly. The activity of a hammerhead ribozyme in the presence of Co(NH3)63+ also showed that inner-sphere coordination is not necessary (53). Despite the variations in the properties of divalent metal ions, monovalent metal ions, exchange-inert metal ions and even ammonium ions, all have positive charge in common. An appropriate ratio of charge to the hammerhead ribozyme seems to be a condition for activity. In general, it now seems likely that the presence of a relatively dense positive charge, rather than of any particular metal ions, is the general fundamental requirement; it now seems less important whether or not the positive charge plays a role in the chemical process.

However, our recent findings (55) and the present data suggest that there exist more than one channel for reactions catalyzed by the R32 hammerhead ribozyme (Fig. 1B) and the role of metal ions can be assigned to a specific chemical process. With respect to the two different channels, it is clear that the divalent metal ion-catalyzed reaction is significantly more efficient than the monovalent metal ion-catalyzed reaction. Thus, extremely high concentrations of metal ions are required for the monovalent metal ion-catalyzed reaction. Indeed, as can be seen in Figure 3A–D, rates of reaction in 1 and 3 M NaCl can be enhanced (>100-fold) by addition of a small amount of divalent ions. Therefore, it is likely that, under physiological conditions, hammerhead ribozymes use divalent ions as the catalytic cofactor and, thus, they act as true metalloenzymes in vivo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cech T.R., Zaug,A.J. and Grabowski,P.J. (1981) In vitro splicing of the ribosomal RNA precursor of Tetrahymena: involvement of a guanosine nucleotide in the excision of the intervening sequence. Cell, 27, 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerrier-Takada C., Gardiner,K., Marsh,T., Pace,N. and Altman,S. (1983) The RNA moiety of ribonuclease P is the catalytic subunit of the enzyme. Cell, 35, 849–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou D.-M. and Taira,K. (1998) The hydrolysis of RNA: from theoretical calculations to the hammerhead ribozyme-mediated cleavage of RNA. Chem. Rev., 98, 991–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott W.G. (1998) RNA catalysis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 8, 720–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takagi Y., Warashina,M., Stec,W.J., Yoshinari,K. and Taira,K. (2001) Recent advances in the elucidation of the mechanisms of action of ribozymes. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 1815–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noller H.F., Hoffarth,V. and Zimniak,L. (1992) Unusual resistance of peptidyl transferase to protein extraction procedures. Science, 256, 1416–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nissen P., Hansen,J., Ban,N., Moore,P.B. and Steitz,T.A. (2000) The structural basis of ribosome activity in peptide bond synthesis. Science, 289, 920–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muth G.W., Ortoleva-Donnelly,L. and Strobel,S.A. (2000) A single adenosine with a neutral pKa in the ribosomal peptidyl transferase center. Science, 289, 947–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cech T.R. (2000) Structural biology. The ribosome is a ribozyme. Science, 289, 878–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polacek N., Gaynor,M., Yassin,A. and Mankin,A.S. (2001) Ribosomal peptidyl transferase can withstand mutations at the putative catalytic nucleotide. Nature, 411, 498–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferré-D’Amaré A.R., Zhou,K. and Doudna,J.A. (1998) Crystal structure of a hepatitis delta virus ribozyme. Nature, 395, 567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perrotta A.T., Shih,I. and Been,M.D. (1999) Imidazole rescue of a cytosine mutation in a self-cleaving ribozyme. Science, 286, 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakano S., Chadalavada,D.M. and Bevilacqua,P.C. (2000) General acid-base catalysis in the mechanism of a hepatitis delta virus ribozyme. Science, 287, 1493–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih I. and Been,M.D. (2001) Involvement of a cytosine side chain in proton transfer in the rate-determining step of ribozyme self-cleavage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 1489–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earnshaw D.J. and Gait,M.J. (1998) Hairpin ribozyme cleavage catalyzed by aminoglycoside antibiotics and the polyamine spermine in the absence of metal ions. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 5551–5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKay D.B. (1996) Structure and function of the hammerhead ribozyme: an unfinished story. RNA, 2, 395–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wedekind J.E. and McKay,D.B. (1998) Crystallographic structures of the hammerhead ribozyme: relationship to ribozyme folding and catalysis. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 27, 475–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uhlenbeck O.C. (1987) A small catalytic oligoribonucleotide. Nature, 328, 596–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haseloff J. and Gerlach,W.L. (1988) Simple RNA enzymes with new and highly specific endoribonuclease activities. Nature, 334, 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchins C.J., Rathjen,P.D., Forster,A.C. and Symons,R.H. (1986) Self-cleavage of plus and minus RNA transcripts of avocado sunblotch viroid. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 3627–3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koizumi M., Hayase,Y., Iwai,S., Kamiya,H., Inoue,H. and Ohtsuka,E. (1989) Design of RNA enzymes distinguishing a single base mutation in RNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 7059–7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahm S.C., Derrick,W.B. and Uhlenbeck,O.C. (1993) Evidence for the role of solvated metal hydroxide in the hammerhead cleavage mechanism. Biochemistry, 32, 13040–13045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uchimaru T., Uebayasi,M., Tanabe,K. and Taira,K. (1993) Theoretical analyses on the role of Mg2+ ions in ribozyme reactions. FASEB J., 7, 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steitz T.A. and Steitz,J.A. (1993) A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 6498–6502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pyle A.M. (1993) Ribozymes: a distinct class of metalloenzymes. Science, 261, 709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott W.G., Murray,J.B., Arnold,J.R.P., Stoddard,B.L. and Klug,A. (1996) Capturing the structure of a catalytic RNA intermediate: the hammerhead ribozyme. Science, 274, 2065–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warashina M., Takagi,Y., Sawata,S., Zhou,D.-M., Kuwabara,T. and Taira,K. (1997) Entropically driven enhancement of cleavage activity of a DNA-armed hammerhead ribozyme: mechanism of action of hammerhead ribozymes. J. Org. Chem., 62, 9138–9147. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou D.-M., Zhang,L.-H. and Taira,K. (1997) Explanation by the double-metal-ion mechanism of catalysis for the differential metal ion effects on the cleavage rates of 5′-oxy and 5′-thio substrates by a hammerhead ribozyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 14343–14348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pontius B.W., Lott,W.B. and von Hippel,P.H. (1997) Observations on catalysis by hammerhead ribozymes are consistent with a two-divalent-metal-ion mechanism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 2290–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lott W.B., Pontius,B.W. and von Hippel,P.H. (1998) A two-metal-ion mechanism operates in the hammerhead ribozyme-mediated cleavage of an RNA substrate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 542–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuimelis R.G. and McLaughlin,L.W. (1998) Mechanisms of ribozyme-mediated RNA cleavage. Chem. Rev., 98, 1027–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres R.A. and Bruice,T.C. (1998) Molecular dynamics study displays near in-line attack conformations in the hammerhead ribozyme self-cleavage reaction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 11077–11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S., Karbstein,K., Peracchi,A., Beigelman,L. and Herschlag,D. (1999) Identification of the hammerhead ribozyme metal ion binding site responsible for rescue of the deleterious effect of a cleavage site phosphorothioate. Biochemistry, 38, 14363–14378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torres R.A. and Bruice,T.C. (2000) The mechanism of phosphodiester hydrolysis: near in-line attack conformation in the hammerhead ribozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 122, 781–791. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maderia M., Hunsicker,L.M. and DeRose,V.J. (2000) Metal–phosphate interactions in the hammerhead ribozyme observed by 31P NMR and phosphorothioate substitutions. Biochemistry, 39, 12113–12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshinari K. and Taira,K. (2000) A further investigation and reappraisal of the thio effect in the cleavage reaction catalyzed by a hammerhead ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1730–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peracchi A., Beigelman,L., Scott,E.C., Uhlenbeck,O.C. and Herschlag,D. (1997) Involvement of a specific metal ion in the transition of the hammerhead ribozyme to its catalytic conformation. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 26822–26826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knöll R., Bald,R. and Fürste,J.P. (1997) Complete identification of nonbridging phosphate oxygens involved in hammerhead cleavage. RNA, 3, 132–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamatsu Y., Warashina,M., Kuwabara,T., Tanaka,Y., Yoshinari,K. and Taira,K. (2000) Significant activity of a modified ribozyme with N7-deazaguanine at G10.1: the double-metal-ion mechanism of catalysis in reactions catalysed by hammerhead ribozymes. Genes Cells, 5, 603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peracchi A., Beigelman,L., Usman,N. and Herschlag,D. (1996) Rescue of abasic hammerhead ribozymes by exogenous addition of specific bases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 11522–11527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peracchi A., Karpeisky,A., Maloney,L., Beigelman,L. and Herschlag,D. (1998) A core folding model for catalysis by the hammerhead ribozyme accounts for its extraordinary sensitivity to abasic mutations. Biochemistry, 37, 14765–14775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray J.B. and Scott,W.G. (2000) Does a single metal ion bridge the A-9 and scissile phosphate groups in the catalytically active hammerhead ribozyme structure? J. Mol. Biol., 296, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka Y., Morita,E.H., Hayashi,H., Kasai,Y., Tanaka,T. and Taira,K. (2000) Well-conserved tandem G·A pairs and the flanking C·G pair in hammerhead ribozymes are sufficient for capture of structurally and catalytically important metal ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 122, 11303–11310. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzumura K., Warashina,M., Yoshinari,K., Tanaka,Y., Kuwabara,T., Orita,M. and Taira,K. (2000) Significant change in the structure of a ribozyme upon introduction of a phosphorothioate linkage at P9: NMR reveals a conformational fluctuation in the core region of a hammerhead ribozyme. FEBS Lett., 473, 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka Y., Kojima,C., Morita,E.H., Kasai,K., Ono,A., Kainosho,M. and Taira,K. (2002) Identification of the metal ion binding site on an RNA motif from hammerhead ribozymes using 15N-NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 4595–4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen M.R., Simorre,J.P., Hanson,P., Mokler,V., Bellon,L., Beigelman,L. and Pardi,A. (1999) Identification and characterization of a novel high affinity metal-binding site in the hammerhead ribozyme. RNA, 5, 1099–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feig A.L., Panek,M., Horrocks,W.D. and Uhlenbeck,O.C. (1999) Probing the binding of Tb(III) and Eu(III) to the hammerhead ribozyme using luminescence spectroscopy. Chem. Biol., 6, 801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hampel A. and Cowan,J.A. (1997) A unique mechanism for RNA catalysis: the role of metal cofactors in hairpin ribozyme cleavage. Chem. Biol., 4, 513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nesbitt S., Hegg,L.A. and Fedor,M.J. (1997) An unusual pH-independent and metal-ion-independent mechanism for hairpin ribozyme catalysis. Chem. Biol., 4, 619–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young K.J., Gill,F. and Grasby,J.A. (1997) Metal ions play a passive role in the hairpin ribozyme catalysed reaction. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3760–3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fedor M.J. (2000) Structure and function of the hairpin ribozyme. J. Mol. Biol., 297, 269–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Rear J.L., Wang,S., Feig,A.L., Beigelman,L., Uhlenbeck,O.C. and Herschlag,D. (2001) Comparison of the hammerhead cleavage reactions stimulated by monovalent and divalent cations. RNA, 7, 537–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curtis E.A. and Bartel,D.P. (2001) The hammerhead cleavage reaction in monovalent cations. RNA, 7, 546–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray J.B., Seyhan,A.A., Walter,N.G., Burk,J.M. and Scott,W.G. (1998) The hammerhead, hairpin and VS ribozymes are catalytically proficient in monovalent cations alone. Chem. Biol., 5, 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takagi Y. and Taira,K. (2002) Detection of a proton-transfer process by kinetic solvent isotope effects in NH4+-mediated reactions catalyzed by a hammerhead ribozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 3850–3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sawata S., Komiyama,M. and Taira,K. (1995) Kinetic evidence based on solvent isotope effects for the nonexistence of a proton-transfer process in reactions catalyzed by a hammerhead ribozyme: implication to the double-metal-ion mechanism of catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 117, 2357–2358. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakano S., Proctor,D.J. and Bevilacqua,P.C. (2001) Mechanistic characterization of the HDV genomic ribozyme: assessing the catalytic and structural contributions of divalent metal ions within a multichannel reaction mechanism. Biochemistry, 40, 12022–12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bassi G.S., Møllegaard,N.E., Murchie,A.I., von Kitzing.,E. and Lilley,D.M. (1995) Ionic interactions and the global conformations of the hammerhead ribozyme. Nature Struct. Biol., 2, 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bassi G.S., Murchie,A.I., Walter,F., Clegg,R.M. and Lilley,D.M. (1997) Ion-induced folding of the hammerhead ribozyme: a fluorescence resonance energy transfer study. EMBO J., 16, 7481–7489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bassi G.S., Møllegaard,N.E., Murchie,A.I. and Lilley,D.M. (1999) RNA folding and misfolding of the hammerhead ribozyme. Biochemistry, 38, 3345–3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hammann C., Norman,D.G. and Lilley,D.M. (2001) Dissection of the ion-induced folding of the hammerhead ribozyme using 19F NMR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 5503–5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sawata S., Shimayama,M., Komiyama,M., Kumar,P.K.R., Nishikawa,S. and Taira,K. (1993) Enhancement of the cleavage rates of DNA-armed hammerhead ribozymes by various divalent metal ions. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 5656–5660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orita M., Vinayak,R., Andrus,A., Warashina,M., Chiba,A., Kaniwa,H., Nishikawa,F., Nishikawa,S. and Taira,K. (1996) Magnesium-mediated conversion of an inactive form of a hammerhead ribozyme to an active complex with its substrate. An investigation by NMR spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 9447–9454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Menger M., Tuschl,T., Eckstein,F. and Porschke,D. (1996) Mg2+-dependent conformational changes in the hammerhead ribozyme. Biochemistry, 35, 14710–14716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hendry P. and McCall,M.J. (1995) A comparison of the in vitro activity of DNA-armed and all-RNA hammerhead ribozymes. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 3928–3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Horton T.E., Clardy,D.R. and DeRose,V.J. (1998) Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopic measurement of Mn2+ binding affinities to the hammerhead ribozyme and correlation with cleavage activity. Biochemistry, 37, 18094–18101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hunsicker L.M. and DeRose,V.J. (2000) Activities and relative affinities of divalent metals in unmodified and phosphorothioate-substituted hammerhead ribozymes. J. Inorg. Biochem., 80, 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Doherty E.A. and Doudna,J.A. (2000) Ribozyme structures and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 597–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]