Abstract

Laminin is a multifunctional heterotrimeric protein present in extracellular matrix where it regulates processes that compose tissue architecture including cell differentiation. Laminin γ1 is the most widely expressed laminin chain and its absence causes early lethality in mouse embryos. Laminin γ1 chain gene (LAMC1) promoter contains several GC/GT-rich motifs including the bcn-1 element. Using the bcn-1 element as a bait in the yeast one-hybrid screen, we cloned the gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor (GKLF or KLF4) from a rat mesangial cell library. We show that GKLF binds bcn-1, but this binding is not required for the GKLF-mediated activation of the LAMC1 promoter. The activity of GKLF is dependent on a synergism with another Kruppel-like factor, Sp1. The LAMC1 promoter appears to have multiple GKLF- and Sp1-responsive elements which may account for the synergistic activation. We provide evidence that the synergistic action of GKLF and Sp1 is dependent on the promoter context and the integrity of GKLF activation and DNA-binding domain. GKLF is thought to participate in the switch from cell proliferation to differentiation. Thus, the Sp1–GKLF synergistic activation of the LAMC1 promoter may be one of the avenues for expression of laminin γ1 chain when laminin is needed to regulate cell differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

Laminin is a high molecular weight multifunctional protein present in extracellular matrix. It consists of three polypeptide chains, α, β and γ, held together by dilsulfide bonds forming a cruciform structure (1). There are five α chains (α1–5), three β chains (β1–3) and three γ chains (γ1–3), which account for the 12 known laminin trimeric assemblies (Laminin 1–12). Laminins not only function as structural components, but also bind cell surface receptors such as integrins and α-dystroglycan. Laminin-mediated interactions play a key role in forming cellular architecture through processes such as cell adhesion, spreading and migration (1–3). Laminins also regulate cell differentiation (2,4–7).

The γ1 chain, found in 10 out of the 12 known trimeric laminin isoforms, is the most widely expressed laminin chain (1). Laminin γ1 is required for basement membrane formation and its absence causes early lethality in mouse embryos (8,9). These observations suggest that the synthesis of γ1 chain is essential for the laminin heterotrimeric assembly. Because its role is so important, regulation of laminin γ1 chain (LAMC1) gene expression has generated considerable interest (7,10–14). LAMC1 gene expression is responsive to a multitude of extracellular signals, including glucose (14), IGF (14), IL-1β, TGF-β, phorbol esters (11) and retinoic acid (10). Considering the fact that laminin is a multifunctional protein, it is not surprising that LAMC1 gene expression is responsive to many signals.

Cloning of the 5′ region of the LAMC1 gene revealed that the human and rodent promoters of these genes do not have TATA or CAAT boxes, but contain several GC/GT motifs, an arrangement commonly seen in TATA-less promoters (13,15). The LAMC1 promoter contains binding sites for several transcription factors including NF-κB (16,17), retinoic acid receptor (7,10), AP-2 (17), Sp1 (18) and TFE3 (19). This assortment of transcriptional elements renders the LAMC1 promoter responsive to multiple extracellular signals. The multiplicity of the transcriptional elements allows the LAMC1 gene to respond to various extracellular signals that call for laminin expression to fulfill one of its many specific cellular functions.

One of the highly conserved GC/GT-rich motifs within the LAMC1 promoter is the transcriptionaly active bcn-1 element (11,12). We used the yeast one-hybrid screen (20) to identify transcription factors from mesangial cells that regulate activity of the bcn-1 element. The screen identified several cognate transcription factors including GKLF/KLF4. We demonstrate that GKLF regulates LAMC1 gene promoter activity in several cell lines. We provide evidence that the action of GKLF is exerted through its synergistic action with Sp1. This synergism depends on the promoter context, the integrity of the GKLF activation and DNA-binding domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

Rat mesangial cell, SI–MC cells, were cultured and maintained as described previously (21). HeLa cells and Drosophila melanogaster Shnider SL2 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone). SL2 cells were maintained at 27°C in M3 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma) and antibiotics.

Construction of rat mesangial cell cDNA–activation domain (AD) fusion library for yeast one-hybrid screen

The rat mesangial cell line used for construction of the library was established from collagenase-treated glomeruli, and cells were characterized (16,22) and maintained as described previously (12). Total cellular RNA was prepared from phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-treated (1 h) rat mesangial cells as described previously (23). Poly(A)+ RNA was reverse transcribed using an oligo(dT) primer with a XhoI site. The RNA strand of the mRNA–cDNA hybrid was replaced with the corresponding DNA strand by using Escherichia coli RNase H, E.coli DNA polymerase I and E.coli DNA ligase (23), and the cDNA was ligated to EcoRI linkers after both termini were blunt ended. After cleavage with EcoRI and XhoI, the cDNA was ligated to EcoRI/SalI-digested yeast expression plasmid pGAD424 (2µ, Leu 2) (Clontech). The ligation products were purified by ethanol precipitation, and electro-transformed into E.coli DH10B (Gibco) with E.coli Pulser (Bio-Rad) to generate the pGAD-MC cDNA library.

Yeast one-hybrid screen

Yeast one-hybrid screen was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol (MATCHMAKER One-Hybrid System; Clontech). Briefly, three tandem copies of the 17 bp bcn-1 motif (5′-ccccgcccacctcgcgc-3′) were inserted upstream of the HIS3 reporter gene by designing two antiparallel 3¥ bcn-1 oligonucleotides with EcoRI and XbaI or SalI sites at the ends. Sense and antisense oligonucleotides were annealed and sub-cloned into the EcoRI/XbaI digested pHISi-1 reporter plasmids (Clontech) or EcoRI/SalI digested pLacZi (Clontech). Inserts were sequenced to confirm the presence and integrity of the bcn-1 elements. Both bcn-1-reporter constructs were integrated into the genome of YM4271 strain to generate bcn-1 reporter strains. Background HIS3 activity was ablated using 10 mM 3-aminotrizole (3AT) (Sigma). Screening bcn-1 reporter strains with pGAD-MC cDNA library identified genes encoding bcn-1 binding proteins. Plasmids were isolated from yeast clones capable of growing in the presence of 10 mM 3AT in (–) leucine and (–) histidine media. Plasmids from these clones were transformed into competent DH5α bacteria (Gibco) and each cDNA insert was sequenced and compared with known sequences in the GenBank database.

Preparation of nuclear extracts and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs)

EMSA was performed as described previously (11) with some modification. Briefly, oligonucleotides used for EMSAs were synthesized commercially (Gibco). EMSA probes were generated by end labeling 1 pmol double-stranded oligonucleotides with 10 µCi [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) (DuPont NEN) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Gibco). Labeled nucleotides were purified from unincorporated nucleotides using Micro Bio-spin p-30 Chromatography columns (Bio-Rad). Binding reactions were performed in 10 µl volumes containing 10 fmol (50 000–200 000 c.p.m.) of labeled probe, 2 µg of recombinant GKLF protein and 0.5 µg of poly(dI-dC) in binding buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 4% glycerol]. Samples were incubated for 20 min at room temperature and then separated by electrophoresis on a 6% polyacrylamide gel [19:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide (Bio-Rad)] in 0.5× TBE (25 mM Tris, 24 mM Borate and 0.5 mM EDTA).

Plasmid constructs

The LAMC1 promoter fragment spanning the –1077 to –20 region of the gene (relative to the first codon), designated –1077/–20 LAMC1, was constructed by PCR amplification of the LAMC1 –1104/+35 5′-flanking promoter region (13). The deletion constructs of LAMC1 promoter, –506/–20 LAMC1, –293/–20 LAMC1, –506/–197, –310/–197 LAMC1 and –293/–197 LAMC1, were generated by PCR using appropriate primers and the –1077/–20 LAMC1 promoter as template. The PCR products were ligated into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and digested by SacI and BglII. The SacI–BglII fragments were ligated into pGL3 basic vector cut with SacI–BglII using Rapid DNA Ligation Kit (Roche). The construction of –370/–20 LAMC1 and –370/–197 LAMC1 was carried out by digesting –506/–20 LAMC1 or –506/–197 LAMC1 with MluI and BglII, and the fragments were subcloned into MluI and BglII digested pGL3 basic vector. The construction of –239/–20 LAMC1 was carried out by digesting with XhoI and BglII and the fragments were subcloned into XhoI and BglII digested pGL3 basic vector.

The mammalian expression vectors containing full length mouse GKLF (pMT3-GKLF) (24), pMT3-GKLF(E93/95/96V) or pMT3-GKLF(D99/102/104V) (kindly provided by Dr Vincent Yang) were described previously (25). The pPac-0 and pPac-Sp1 were described previously (26,27). The GKLF constructs in pPac-GKLF, pPac-GKLF(1–401) and pPac-GKLF(350–483), pPac-GKLF(E93/95/96V) or pPac-GKLF(D99/102/104V), were generated by PCR using pMT3-GKLF, pMT3-GKLF(E93/95/96V) or pMT3-GKLF(D99/102/104V), as a template, respectively. PCR products were ligated to pGEM-T Easy vector and digested with BamHI and XhoI. The fragments were ligated in BamHI- and XhoI-digested pPac-0. To generate pGEX-GKLF, full length GKLF was amplified by PCR using pMT3-GKLF as template. The PCR products were subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector and digested with BamHI and EcoRI. The digested fragment and BamHI- and EcoRI-digested pGEX-KT (28) were ligated as above.

All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transient transfections and luciferase reporter gene assay

SI–MC cells and HeLa cells were plated at 4 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates and incubated in RPMI-1640 or DMEM, respectively, with FBS for 24 h. Cells were transiently transfected (in duplicates) with 1 µg of reporter plasmid, effector expression plasmid (indicated in each experiment) and 0.1 µg of pRL-null (Promega) using SuperFect transfection reagent (Qiagen). Cell extracts were prepared 48 h later in lysis buffer (Promega), and luciferase activity was assayed by Dual Reporter Assay System (Promega) (29). SL2 cells were plated at 2 × 106 cells per well in 6-well plates with 600 µl serum-free media and transfected with 1 µg of reporter plasmid, effector expression plasmid (indicated in each experiment) and 0.1 µg of pRL-null using Cellfectin reagent (Gibco). After 5 h incubation, 300 µl medium with 30% serum was added. After 24 h, 1 ml of medium with 10% serum was added. Cell extracts were prepared 48 h after transfection and then luciferase activity was measured as above.

Production of recombinant proteins

GST–GKLF recombinant protein was produced in bacteria. A single colony of BL21(DE3) pLysS (Novagen) was transformed with pGEX-GKLF, and grown in 100 ml LB broth, containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol, to an optical density of 0.6 at 600 nm. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (0.1 mM) was then added. The incubation was continued for an additional 3 h, at which time the bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation. The pellets were washed in 30 ml PBS and then resuspended in 10 ml sodium Tris EDTA (STE) buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA and 150 mM NaCl, and incubated with 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme on ice for 30 min. After addition of 100 µl of 1 M DTT and 1.4 ml of 10% Sarkosyl, suspension was sonicated for 1 min. To bring the total volume to 20 ml, 4 ml 10% Triton X-100 with STE buffer was added. After removing debris by centrifugation, extracts were frozen and stored in aliquots at –70°C. To purify GST fusion proteins, 1 ml of the bacterial lysate was added to a 300 µl bed of Glutathione Sepharose (Sigma) in PBST (PBS, 1% Triton X-100, 1.0 mM DTT). Suspension was mixed for 1 h (4°C), and after two washes with 1 ml of PBST and one wash with 1 ml elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 9.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100), GST fusion proteins were eluted with 500 µl of elution buffer containing 20 mM reduced glutathione (Sigma) at 4°C for 1 h. The eluted solution was concentrated using Microcon YM-50 (Millipore) by centrifugation and then stored in aliquots at –70°C.

RESULTS

Cloning of the transcription factor GKLF, from a rat mesangial cell cDNA–AD fusion library, using the bcn-1 element as a bait in yeast one-hybrid screen

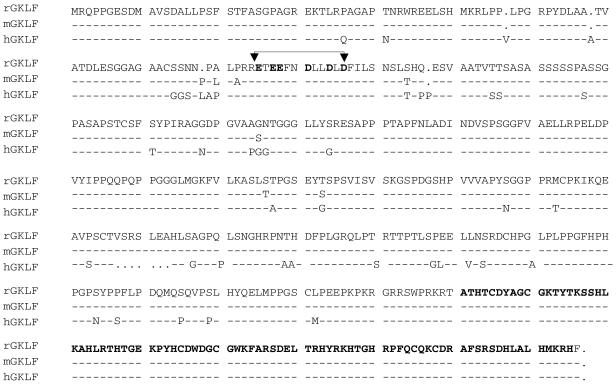

The rodent and human LAMC1 promoter contains a transcriptional element, bcn-1, that binds nuclear proteins from mesangial cells (11–13). We screened a cDNA fusion library, generated from rat mesangial cells, for a screen using the bcn-1 element as a bait in the yeast one-hybrid system. Two true positive cDNA clones represented the rat ortholog of the gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor (GKLF/KLF4) (24,30). Both of the clones, HL1012 and HL1022, were missing the poly(A) tail and the polyadenylation signal. As the rat GKLF cDNA had not been previously cloned, we used PCR to obtain the missing 3′ fragment of the cDNA. The final ORF potentially encodes a 482 amino acid protein with a mass of 52 kDa. The consensus sequence for polyadenylation, AATAAA (31), is found 16 bp upstream of the poly(A) tail. The deduced amino acid sequences of the rat and mouse GKLF are nearly identical (99%) and both share 89% similarity to the human sequence (Fig. 1). The deduced amino acid sequence predicts three tandem zinc finger motifs at the carboxyl end of the C2H2 type found in the Kruppel family of proteins (32). The rat, mouse and human GKLF zinc fingers and the acidic residue clusters within the transcription activation domain (25) are identical. The rat and mouse GKLF zinc finger domains share 58% similarity to the zinc finger domains of Sp1 from these species. There is also a high level of similarity to the zinc finger domains of other transcription factors such as Egr-1 (33), BTEB2/IKLF (34), KKLF (35) and ZF9/CPBP (36).

Figure 1.

The deduced amino acid sequence of rat GKLF and its similarity to the mouse and human sequences. The acidic residue clusters within the activation domain (arrows) and the predicted three tandem zinc finger motifs at the carboxyl end of the C2H2 type found in the Kruppel family of proteins (32) (bold) are identical in the three species.

Northern and western blot analyses showed that GKLF mRNA and protein are expressed in rat mesangial cells grown in culture (data not shown).

Recombinant GKLF binds the bcn-1 motif in vitro

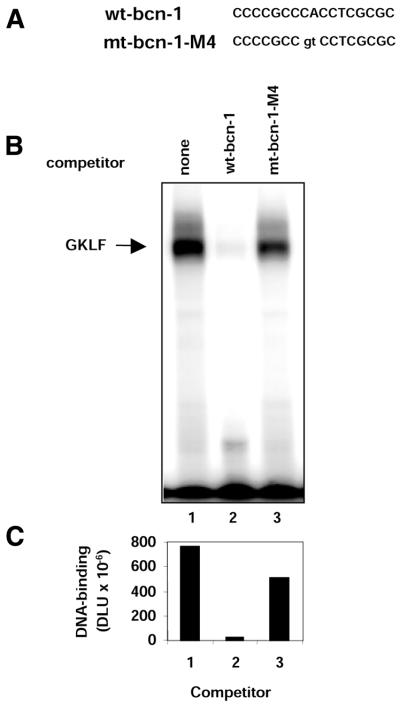

To determine if GKLF directly binds to the bcn-1 motif, we synthesized GST–GKLF fusion protein in E.coli and tested its binding to 32P-labeled double-stranded bcn-1 oligonucleotide in EMSA. The gel shift assay revealed that GST–GKLF bound to 32P-labeled wild-type bcn-1 oligonucleotide (Fig. 2). To map the GKLF binding motif within the bcn-1 sequence, we tested a series of oligonucleotides in which two bases were mutated at a time. This analysis revealed that mutation of any one pair of bases in the middle of the CCCGCCCACCTCGCGC sequence abrogated the GST–GKLF binding (data not shown). To confirm the specificity of GKLF binding to the bcn-1 element we carried out competition experiments in which binding to the 32P-labeled wild-type bcn-1 element was carried out in either the absence or presence of synthetic oligonucleotide containing either wild-type (CCCGCCCACCTGCCGC) or mutated (CCCGCCgtCCTCGCGC) bcn-1 element (Fig. 2). This experiment showed that an excess of oligonucleotide bearing the wild-type bcn-1, but not the mutated motif, abrogated the binding of GKLF to the 32P-labeled wild-type bcn-1. This confirms that GKLF binds in vitro to the bcn-1 element with a high degree of specificity. This result also suggests that the integrity of the CCCAC box, which is known to interact with Kruppel-like factors (37), is critical for the binding of bcn-1 to GKLF.

Figure 2.

Binding of recombinant GKLF to the bcn-1 motif in vitro. (A) The sequence of double-stranded synthetic oligonuleotide containing either wild-type or mutated bcn-1 element that was used as a competitor in the binding reaction. (B) Autoradiograph of the gel from EMSA. DNA-binding reaction was carried out in 10 µl binding buffer containing recombinant rat GST–GKLF and 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide containing wild-type bcn-1 element in the presence of either no competitor (none, lane 1), or 500-fold molar excess of double-stranded oligonucleotide containing either wild-type or mutated bcn-1 sequences as shown in (A). (C) Graph of the densitometric measurements of the shifted bands (B) expressed in digital light units (DLU).

Expression of GKLF activates LAMC1 promoter in rat mesangial and human HeLa cells

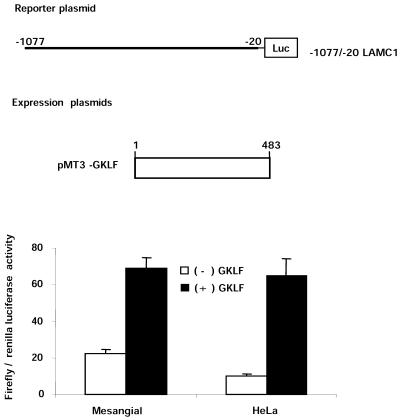

GKLF contains both transcription activation and repression domains and is known to activate and repress gene expression (25,37,38). To test if GKLF activates or represses the LAMC1 promoter, rat mesangial cells were transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter gene driven by the –1077/–20 LAMC1 promoter. Figure 3 shows that expression of GKLF increased the activity of the –1077/–20 LAMC1 promoter construct 3-fold.

Figure 3.

GKLF-mediated activation of LAMC1 promoter in rat mesangial and human HeLa cells. Subconfluent rat mesangial and human HeLa cells were transiently transfected with firefly luciferase gene driven by the rat –1077/–20 LAMC1 promoter fragment with either pMt3 expression vector [(–) GKLF] or expression vector containing GKLF cDNA, pMt3-GKLF [(+) GKLF]. Renilla luciferase plasmid was used as a control for transfection efficiency. Forty-eight hours following transfection, cells were harvested and firefly and renilla luciferase activities were measured. Data are shown as mean ± SD of the ratios of firefly to renilla luciferase activities (n = 4).

GKLF is expressed constitutively in mesangial cells (data not shown), thus the activation mediated by exogenous GKLF might be blunted. HeLa cells do not express GKLF (39), so we next tested the effect of GKLF on the LAMC1 promoter in this cell line. In HeLa cells, exogenous GKLF was a more potent activator of the LAMC1 promoter, where it increased activity of the –1077/–20 LAMC1 promoter 7.7-fold (Fig. 3).

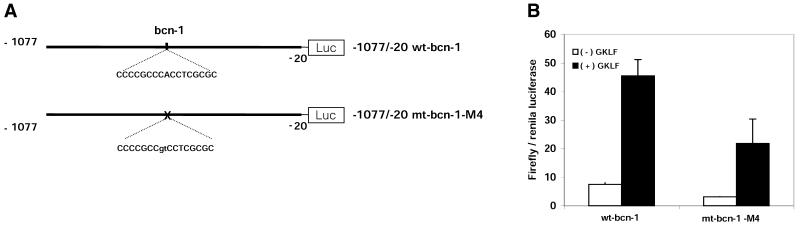

Above we identified mutations of the bcn-1 element that abrogate binding of GKLF (Fig. 2). We mutated these bases within the LAMC1 promoter to test the role of bcn-1 in the GKLF-mediated activation of this promoter. As before, expression of GKLF activated the wild-type LAMC1 promoter in HeLa cells 6-fold. Mutation of the core bases within bcn-1 decreased the baseline activity of the LAMC1 promoter by 50%, but expression of GKLF still increased the activity of the mutated promoter 7-fold (Fig. 4). This suggests that bcn-1 is not required for the GKLF-mediated activation of the LAMC1 promoter in this cell line.

Figure 4.

The bcn-1 element is not required for the GKLF-mediated activation of the LAMC1 promoter in human HeLa cells. (A) Diagram of firefly luciferase reporter gene constructs that were used in transfection of HeLa cells. The sequences of the wild-type (wt-bcn-1) and mutated (mt-bcn-1-M4) bcn-1 located at –495 to –479 within the LAMC1 promoter are shown. (B) Firefly luciferase gene driven by LAMC1 promoter containing either wild-type (wt-bcn-1) or mutated (mt-bcn-1-M4) bcn-1 element fragments was co-transfected in HeLa cells with either pMt3 expression vector [(–) GKLF] or expression vector containing GKLF cDNA, pMt3-GKLF [(+) GKLF]. The renilla luciferase plasmid was used as a control for transfection efficiency. Forty-eight hours following transfection, cells were harvested and firefly and renilla luciferase activities were measured. Data are shown as mean ± SD of the ratios of firefly to renilla luciferase activities (n = 6 ).

Synergistic activation of LAMC1 by GKLF and Sp1 in the Drosophila SL2 cells

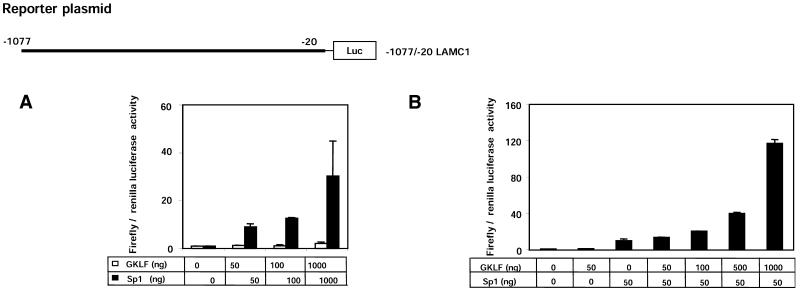

Sp1 activates LAMC1 promoter in hepatocellular carcinomas (18). Expression of exogenous Sp1 increased the activity of LAMC1 promoter in HeLa cells by <2-fold (data not shown). The small effect in response to the exogenous expression of Sp1 may reflect either lack of responsiveness of the LAMC1 promoter to Sp1 in these cells or the fact that these cells already express high endogenous levels of Sp1. We used Drosophila SL2 cells (Fig. 5), which do not express Sp1 (26), to circumvent the potential interference by endogenous Sp1. Co-transfection of LAMC1-luciferase reporter construct into SL2 cells, with as little as 50 ng of the expression vector bearing Sp1 cDNA, increased the activity of the promoter 9-fold (Fig. 5A). With 1000 ng of transfected Sp1 DNA, the increase was >30-fold. These data show that the LAMC1 promoter is activated by Sp1. Unlike Sp1, expression of GKLF in SL2 cells had only a weak effect, where transfection of 1000 ng of expression plasmid bearing GKLF cDNA increased the LAMC1 promoter activity 2-fold (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Synergistic activation of rat LAMC1 promoter by GKLF and Sp1. The Drosophila SL2 cells were transiently co-transfected with rat –1077/–20 LAMC1 promoter-luciferase reporter plasmid with given amounts (ng) of either pPac-GKLF (GKLF), pPac-Sp1 (Sp1) or both expression plasmids. The expression plasmid, pPac-O, containing no insert, was used to adjust the total amount of DNA. Renilla luciferase reporter gene was also included to correct for transfection efficiency. Forty-eight hours following transfections, cells were harvested and luciferase activities in cell lysates were measured. (A) Cells transfected with increasing amounts (0, 50, 100, 1000 ng) of either pPac-GKLF (open columns) or pPac-Sp1 (closed columns). (B) Cells transfected with either pPac-O alone, pPac-GKLF (50 ng), pPac-Sp1 (50 ng) or pPac-Sp1 (50 ng) plus increasing amounts of pPac-GKLF (50–1000 ng). Data are shown as mean ± SD of the ratios of firefly to renilla luciferase activities (n = 4).

The LAMC1 promoter is induced by and contains several putative GKLF- and Sp1-binding sites (TFSEARCH). Thus, we wondered whether these transcription factors cooperate in the regulation of the LAMC1 promoter. Sp1 expression plasmid (50 ng) increased LAMC1 promoter activity 10-fold in SL2 cells (Fig. 5A). The Sp1-mediated effect was potentiated by co-transfection of increasing amounts of expression plasmid bearing GKLF (Fig. 5B). For example, co-transfection of 50 ng Sp1 and 1000 ng GKLF DNA increased the LAMC1 promoter activity >100-fold. These results suggest that GKLF and Sp1 activate the LAMC1 promoter synergistically, meaning that the effect seen with GKLF and Sp1 co-transfection is greater than the sum of the effects seen when either GKLF or Sp1 is expressed alone [(GKLF&Sp1/GKLF + Sp1)>1] (Fig. 6). These results indicate that the GKLF-mediated activation of the LAMC1 promoter depends on the presence of Sp1.

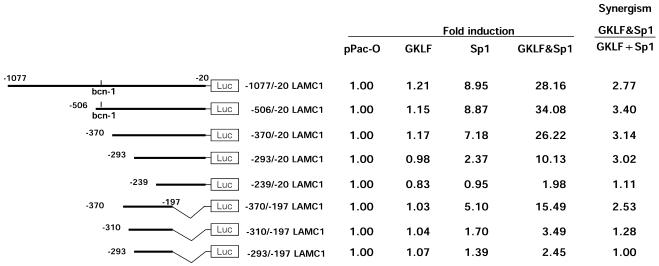

Figure 6.

Functional mapping of the region responsible for the Sp1–GKLF-mediated synergistic activation of rat LAMC1 promoter in SL2 cells. The Drosophila SL2 cells were transiently co-transfected with a series of LAMC1 promoter deletion constructs in combination with 50 ng of either pPac-O (pPac), pPac-GKLF (GKLF), pPac-Sp1 (Sp1) or both expression (GKLF&Sp1) plasmids. Forty-eight hours following transfections, cells were harvested and both firefly and renilla luciferase activities in the cell lysates were measured. Activities of the promoter constructs were calculated as ratios of firefly to renilla luciferase activity (mean of n = 4). The numbers shown for each construct represent values that were normalized by dividing each firefly luciferase activity by the renilla luciferase activity measured in pPac alone. Synergism was calculated as the activity obtained when cells were co-transfected with both Sp1 and GKLF divided by the sum of the activities measured when Sp1 and GKLF were expressed alone, GKLF&Sp1/GKLF + Sp1, where a ratio >1.0 reflects synergistic activation.

Functional mapping of LAMC1 promoter in SL2 cells

To identify the regions required for the synergistic activation by Sp1 and GKLF, we tested the activity of a series of LAMC1 promoter deletion mutants in SL2 cells luciferase reporter assay without and with expression of Sp1 and/or GKLF. With 50 ng of expression plasmid, the –1077/–20 and –506/–20 fragments of the rat LAMC1 promoter were activated by Sp1 nearly 9-fold (Fig. 6). In contrast, expression of GKLF had only a marginal effect: 15–20% increase. When Sp1 and GKLF were expressed together, the activity of these fragments were increased 28–34-fold, a 3-fold synergism. The –370/–20 LAMC1 promoter fragment, which lacks the bcn-1 element, exhibited a similar level of Sp1–GKLF-mediated synergism (3.14-fold) as was seen with the –506/–20 LAMC1 fragment. This similarity indicates that the bcn-1 element might not be essential for the synergistic Sp1–GKLF activation of the LAMC1 promoter.

With further 5′ deletion, –293/–20 LAMC1 promoter fragment, there was a decrease in Sp1-mediated activation, but the degree of Sp1–GKLF-mediated synergism (3.02-fold) was maintained. This result suggests that the region between –370 and –294 might contain an Sp1-responsive element(s) that is not needed for synergism. With 5′ deletion of another 54 nt, the Sp1 responsiveness and Sp1–GKLF synergism was abrogated. This result suggests that the stretch between –293 and –239 contains an element(s) that is critical for Sp1 and the synergistic Sp1–GKLF activation of the LAMC1 promoter. Next we tested several fragments of the LAMC1 promoter lacking a portion of the 3′ end. The –370/–197 fragment exhibited diminished, but still potent, Sp1 and Sp1–GKLF responses compared with the –370/–20 fragment; Sp1-mediated increase was 5-fold compared with 7-fold, and Sp1–GKLF-mediated increase was 15-fold compared with 26-fold. These results suggest that the –196 to –20 fragment contains an Sp1-responsive element(s), but this motif(s) does not appear to be important for the synergism. In contrast, 5′ deletion of 60 nt from this fragment, –310/–197 LAMC1, greatly reduced the Sp1 response and the Sp1–GKLF synergism. Taken together these results suggest that the full Sp1–GKLF synergistic activation requires a core –293/–239 region in conjunction with either a 5′ or a 3′ adjacent domain, that is –370/–310 or –196/–20 fragments.

The deletion analysis (Fig. 6) suggests there is no single GKLF- and Sp1-responsive element within the LAMC1 promoter that can completely account for the cooperative activation of this promoter by these factors. Instead, there are likely multiple overlapping and non-overlapping GKLF- and Sp1-binding sites in the –370/–239 region that permit synergistic activation.

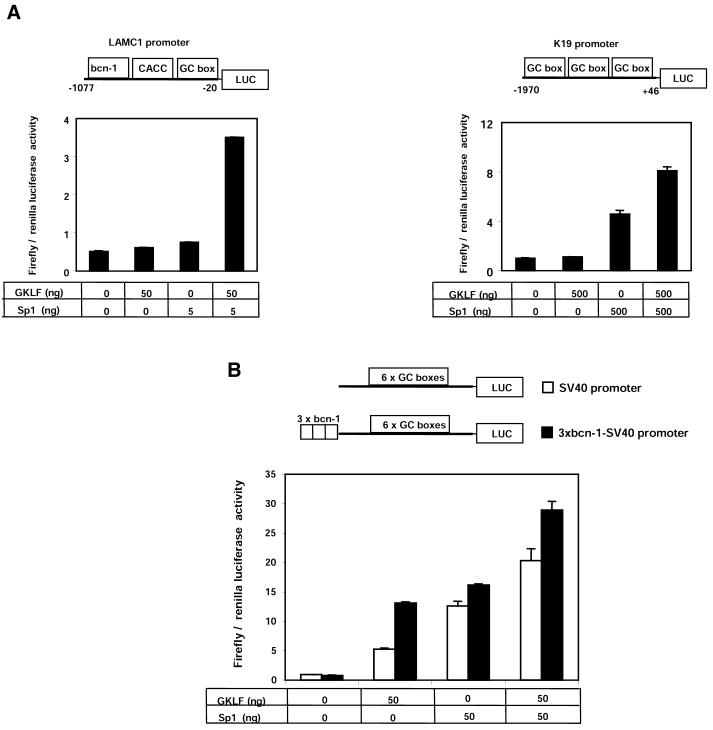

The Sp1–GKLF synergistic activation depends on the promoter context

Many gene promoters that are regulated by Sp1 and GKLF have multiple recognition sites for these factors, including the Keratin 19 (K19) promoter (39). We investigated the Sp1–GKLF synergism with other promoters that have multiple elements recognized by these transcription factors. Individual transfections of either 5 ng pPac-Sp1 or 50 ng pPac-GKLF had no effect, but when co-transfected the activity of the LAMC1 promoter increased 7-fold (Fig. 7A). Transfection of Sp1 (500 ng) DNA into SL2 cells activated the K19 promoter 5-fold (Fig. 7B). By itself GKLF (500 ng) had no effect, but when co-expressed with Sp1 the K19 promoter activity increased >8-fold. This indicates synergistic activation of the K19 promoter, but compared with the LAMC1 promoter the magnitude of the synergism was much lower (Fig. 7B). The SV40 promoter contains six GC-boxes that are responsive to Sp1. Exogenous Sp1 (14-fold) and, to a lesser extent, GKLF (6-fold) activated the synthetic promoter in SL2 cells, but when used together their effect was merely additive (20-fold induction) (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the Sp1–GKLF-mediated synergistic activation of LAMC1, K19 and SV40 promoters in SL2 cells. SL2 cells were transiently transfected with expression vector containing no insert pPac-O, pPac-GKLF or pPac-Sp1 together with firefly luciferase reporter gene driven by either LAMC1 or K19 promoters (A), or SV40 promoter with or without three tandem repeats of the bcn-1 element (B). The tables below the graphs show amounts of pPac-GKLF and pPac-Sp1 expression plasmids used (ng). Data are shown as mean ± SD of ratios of firefly to renilla luciferase activities (n = 4).

We wondered if Sp1–GKLF synergism could be observed if three tandem repeats of the bcn-1 sequence were inserted upstream of the SV40 promoter. We chose the SV40 promoter since it contains multiple Sp1-binding sites (40). The activity of the 3¥ bcn-1–SV40 synthetic promoter construct was similarly responsive to both GKLF (16-fold increase) and Sp1 (20-fold increase). When GKLF and Sp1 were co-expressed, the activity of the 3¥ bcn-1–SV40 synthetic promoter increased 37-fold, an additive effect rather than a synergistic response. Together these results suggest that the promoter context could be a key determinant of the Sp1–GKLF synergism of those target promoters that have multiple binding sites for these factors.

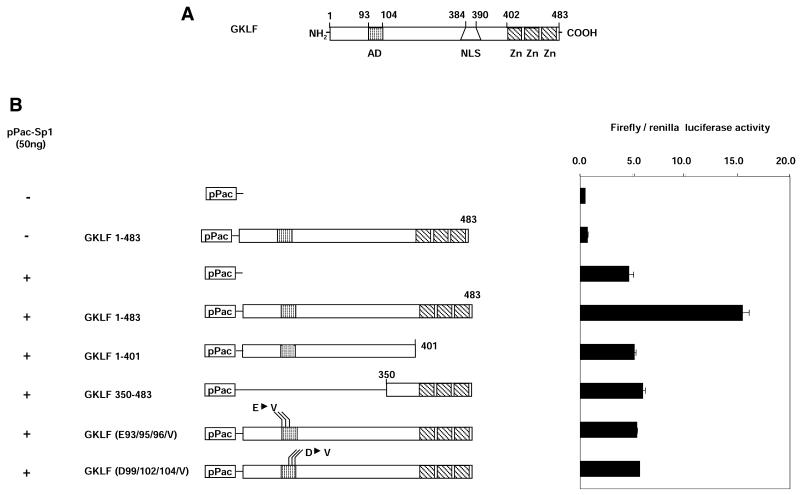

The GKLF activation domain and zinc fingers are required for the Sp1–GKLF synergistic induction of the LAMC1 promoter in SL2 cells

As is the case with most transcription factors, the GKLF structure is modular. GKLF contains two clusters of acidic residues in the AD (25) and a region that harbors three zinc fingers (Fig. 8A). Several deletion and point mutants of GKLF were used in transfections of SL2 cells to define the domains that are required for the synergistic activation of LAMC1 promoter by GKLF and Sp1. As before, expression of the full-length GKLF (GKLF 1–483) potentiated the Sp1-induced activation of the LAMC1 promoter. In contrast, the GKLF deletion construct that lacked the C-terminus, GKLF 1–401, did not stimulate the Sp1-mediated activation of the LAMC1 promoter (Fig. 8B). These results indicate that the GKLF zinc fingers are required for the synergistic action of Sp1 and GKLF and that GKLF might need to bind to DNA for the synergism to be observed.

Figure 8.

The GKLF activation and zinc finger domains are required for the synergistic activation of LAMC1 promoter in SL2 cells. (A) Diagram of rat GKLF. Putative activation domain (AD), nuclear localization signal (NLS) and the three zinc fingers (Zn) are shown. (B) pPac-Sp1 (50 ng) and a series of pPac-GKLF mutants were co-transfected with the LAMC1 promoter-firefly and renilla luciferase reporter gene constructs. Activity of the LAMC1 promoter upstream of firefly luciferase was assessed in transient co-transfection experiments in SL2 cells as before. Results are shown as the mean ratio of firefly to renilla luciferase activity ± SD (n = 4).

A lack of synergism was also observed with the deletion of the N-terminal part of GKLF (GKLF 350–483). This deletion of GKLF removed the transcriptional AD, a highly acidic region. Two clusters of acidic residues within the AD are required for GKLF transcriptional activity (25). To test if the AD of GKLF is required for the synergism, we used two GKLF constructs where the residues within either the glutamic or aspartic acid clusters within the AD were mutated to valines. Co-transfection of either of the two AD GKLF mutant constructs had no effect on the Sp1-mediated activation of LAMC1 promoter. These results suggest that the GKLF AD is also required for the synergistic activation.

DISCUSSION

We provide evidence that GKLF and Sp1 synergistically activate the LAMC1 promoter, a cooperative process not previously described between two members of the Sp/XKLF transcription factor family (Figs 5–8). Although the precise molecular mechanism of the Sp1–GKLF synergism in the activation of the LAMC1 promoter remains to be elucidated, we have identified several components that appear to be required. First, we show that the GKLF DNA-binding domain is required (Fig. 8). Since recruitment of factors to promoters is the key determinant of the rate of transcription (41), the requirement for DNA binding suggests that GKLF may aid in the recruitment of other factors to the LAMC1 promoter that are needed for the synergism. This may include co-activators such as CBP or even Sp1 itself, both known to physically interact with GKLF (25,42). Indeed, CBP appears to participate in the synergistic activation of LAMC1 promoter by GKLF and Sp1 (data not shown). Second, mutations within the GKLF AD abrogate the Sp1–GKLF synergism (Fig. 8). This result suggests that the AD interacts with another factor(s) that is necessary for the activation of the LAMC1 promoter. The logical candidate here is the co-activator CBP. Third, the LAMC1 promoter has several CACCC and CG-rich GKLF- and Sp1-putative binding sites (18), suggesting the LAMC1 promoter may simultaneously recruit GKLF and Sp1, and thus be synergistically activated. However, as illustrated by the low level of cooperative Sp1–GKLF activation of the K19 promoter (Fig. 7), the mere simultaneous recruitment of GKLF and Sp1 to multiple sites may not be sufficient for effective synergistic activation. Thus, promoter context is also a key determinant. That means the arrangement of the GKLF-, Sp1- and other binding sites within the promoter is a key determinant that defines the overall topology of the promoter bound to cognate transcription factors and determines the strength of coupling to the general transcriptional apparatus. Since the C-terminal domain of Sp1 binds GKLF (42), a direct physical interaction between GKLF and Sp1 is also suggested for the synergistic activation. It is conceivable that there are several adjacent GKLF and Sp1 binding sites within the core domain responsible for the synergism that allow formation of Sp1–GKLF heterodimers resulting in a promoter topology conducive to cooperative activation.

GKLF belongs to the family of Sp/XKLF transcription factors that is composed of at least 16 different mammalian proteins (43). In addition to Sp1 (44) and GKLF, this class of factors also includes Sp2-4, EKLF, LKLF, BKLF, UKLF, BTEB and others. Although these factors are structurally similar and bind similar DNA sequences, their respective gene targets are diverse. This diversity can, in part, be explained by the ability of these proteins to interact with other factors of the same or different family of activators. For example, there are several reports describing the functional relationship between members of the Sp/XKLF family of factors, particularly those interactions involving Sp1. One of the better known examples is that of Sp1 and Sp3. In the regulation of several viral and cellular promoters, Sp3 represses Sp1 activity by competing for the same binding site (45). Similarly, GKLF has been shown to suppress the cytochrome P-450IA1 (CYP1A1) promoter in a manner that is both Sp1- and Sp3-dependent, an observation that, in part, could be explained by the physical interaction between these factors (42). The cooperative effects exhibited by GKLF and Sp1 (Figs 5–8), illustrate how synergism (determined by promoter context), recruitment of a co-activator(s), protein–DNA and protein–protein interaction, could explain specificity of gene induction and the diversity of physiological effects exhibited by closely related transcription factors such as members of the Sp1/XKLF family of proteins.

As illustrated in SL2 cells, Sp1 can activate the LAMC1 promoter, but its effectiveness is increased by GKLF (Figs 5 and 7). The same may be true for HeLa cells that express high levels of endogenous Sp1 but have little endogenous GKLF. As a result, exogenous GKLF is a potent activator of the LAMC1 promoter in these cells (Figs 3 and 4). Thus, GKLF may provide a specific avenue for potent activation of the LAMC1, but only in cells that also express Sp1. What could be the physiological settings for deployment of GKLF to activate the LAMC1 gene? It is thought that GKLF has a role in regulating genes whose expression is found in differentiated cells (37,46). The repertoire of genes activated in differentiating cells may include laminin, which is known to regulate cell differentiation (3,47). GKLF may mediate cell differentiation through the activation of the LAMC1 gene followed by the assembly of laminin. Thus, identification of GKLF as a regulator of LAMC1 gene expression may reflect a pathway for induction of γ1 chain when laminin is needed to regulate cell differentiation. Chang et al. (7) have demonstrated that there are enhancer elements within the first intron of the LAMC1 gene which greatly activate the LAMC1 promoter during retinoic acid induced differentiation of F9 cells. These observations suggest that the role of the LAMC1 gene in cell differentiation can be induced by several pathways.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs Oleg Denisenko and Takaaki Hayashi for their help in various aspects of this work. This work was supported by NIH DK45978 and GM45134, the Northwest Kidney Foundation and the American Diabetes Association (K.B.). Y.K. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association Northwest Affiliate.

DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF390546

REFERENCES

- 1.Tunggal P., Smyth,N., Paulsson,M. and Ott,M.C. (2000) Laminins: structure and genetic regulation. Microsc. Res. Tech., 51, 214–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen K. and Abrass,C.K. (1999) Role of laminin isoforms in glomerular structure. Pathobiology, 67, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deutzmann R. (1995) Laminin. In Schlondorff,D. and Bonventre,J.V. (eds), Molecular Nephrology. Kidney Function in Health and Disease. Dekker, New York, pp. 41–59.

- 4.Simon-Assmann P., Lefebvre,O., Bellissent-Waydelich,A., Olsen,J., Orian-Rousseau,V. and De Arcangelis,A. (1998) The laminins: role in intestinal morphogenesis and differentiation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., 859, 46–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gudas L.J., Grippo,J.F., Kim,K.W., Larosa,G.J. and Stoner,C.M. (1990) The regulation of the expression of genes encoding basement membrane proteins during the retinoic-acid associated differentiation of murine teratocarcinoma cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., 580, 245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan M. and Christiano,A. (1996) The functions of laminins: lessons from in vivo studies. Matrix Biol., 15, 369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang H.S., Kim,N.B. and Philips,S.L. (1996) Positive elements in the laminin γ1 gene synergize to activate high level transcription during cellular differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 1360–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smyth N., Vatansever,H.S., Murray,P., Meyer,M., Frie,C., Paulsson,M. and Edgar,D. (1999) Absence of basement membranes after targeting the LAMC1 gene results in embryonic lethality due to failure of endoderm differentiation. J. Cell Biol., 144, 151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray P. and Edgar,D. (2000) Regulation of programmed cell death by basement membranes in embryonic development. J. Cell Biol., 150, 1215–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogawa K., Burbelo,P.D., Sasaki,M. and Yamada,Y. (1988) The laminin B2 chain promoter contains unique repeat sequences and is active in transient transfection. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 8384–8389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki H., O’Neill,B.C., Suzuki,Y., Denisenko,O.N. and Bomsztyk,K. (1996) Activation of a nuclear DNA-binding protein recognized by a transcriptional element, bcn-1, from the laminin B2 chain gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 18981–18988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki H., Denisenko,O.N., Suzuki,Y., Schullery,D.S. and Bomsztyk,K. (1998) Inducible transcriptional activity of bcn-1 element from laminin g1-chain gene promoter in renal and nonrenal cells. Am. J. Physiol., 275, F518–F526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Neill B.O., Suzuki,H., Loomis,W.P., Denisenko,O. and Bomsztyk,K. (1997) Cloning of the rat laminin γ1-chain gene promoter reveals motifs for recognition of multiple transcription factors. Am. J. Physiol., 273, F411–F420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips S.L., DeRubertis,F.R. and Craven,P.A. (1999) Regulation of the laminin C1 promoter in cultured mesangial cells. Diabetes, 48, 2083–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briggs M.R., Kadonaga,J.T., Bell,S.P. and Tjian,R. (1986) Purification and biochemical characterization of the promoter-specific transcription factor, Sp1. Science, 234, 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson C.A., Gordon,K.L., Couser,W.G. and Bomsztyk,K. (1995) IL-1β increases laminin B2 chain mRNA levels and activates NF-κB in rat glomerular epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol., 268, F273–F278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kedar V., Freese,E. and Hempel,F.G. (1997) Regulatory sequences for the transcription of the laminin B2 gene in astrocytes. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res., 47, 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lietard J., Musso,O., Theret,N., L’Helgoualc’h,A., Campion,J.-P., Yamada,Y. and Clement,B. (1997) Sp1-mediated transactivation of LamC1 promoter and coordinated expression of laminin-γ1 and Sp1 in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Am. J. Pathol., 151, 1663–1672. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawata Y., Suzuki,H., Higaki,Y., Denisenko,O.N., Schullery,D., Abrass,C. and Bomsztyk,K. (2002) bcn-1-element-dependent activation of the laminin g1 chain gene by the cooperative action of TFE3 and Smad proteins. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 11375–11384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang M.M. and Reed,R.R. (1993) Molecular cloning of the olfactory neuronal trasncription factor Olg-1 by genetic selection in yeast. Nature, 364, 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abrass C.K. (1988) Pathogenesis of membranous nephropathy . Annu. Rev. Med., 39, 517–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adler S., Baker,P.J., Johnson,R.J., Ochi,R.F., Pritzl,P. and Couser,W.G. (1986) Complement membrane attack complex stimulates production of reactive oxygen metabolites by cultured rat mesangial cells. J. Clin. Invest., 77, 762–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okayama H., Kawaichi,M., Brownstein,M., Lee,F., Yokota,T. and Arai,K. (1987) High-efficiency cloning of full-length cDNA; construction and screening of cDNA expression libraries for mammalian cells. Methods Enzymol., 154, 3–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shields J.M., Christy,R.J. and Yang,V.W. (1996) Identification and characterization of a gene encoding a gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor expressed during growth arrest. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 20009–20017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geiman D.E., Ton-That,H., Johnson,J.M. and Yang,V.W. (2000) Transactivation and growth suppression by the gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor (Kruppel-like factor 4) are dependent on acidic amino acid residues and protein–protein interaction. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1106–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du Q., Melnikova,I.N. and Gardner,P.D. (1998) Differential effects of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K on Sp1 and Sp3-mediated transcriptional activation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor promoter. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 19877–19883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krasnow M.A., Saffman,E.E., Kornfeld,K. and Hogness,D.S. (1989) Transcriptional activation and repression by Ultrabithorax proteins in cultured Drosophila cells. Cell, 57, 1031–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Seuningen I., Ostrowski,J., Bustelo,X., Sleath,P. and Bomsztyk,K. (1995) The K protein domain that recruits the IL-1-responsive K protein kinase lies adjacent to a cluster of Src- and Vav-SH3-binding sites. Implications that K protein acts as a docking platform. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 26976–26985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shnyreva M., Schullery,D.S., Suzuki,H., Higaki,Y. and Bomsztyk,K. (2000) Interaction of two multifunctional proteins. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K and Y-box binding protein. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 15498–15503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garrett-Sinha L.A., Eberspaecher,H., Seldin,M.F. and de Crombrugghe,B. (1996) A gene for a novel zinc-finger protein expressed in differentiated epithelial cells and transiently in certain mesenchymal cells. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 31384–31390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Proudfoot N.J. and Brownlee,G.G. (1976) 3′ non-coding region sequences in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature, 263, 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris J.F., Hromas,R. and Rauscher,F.J. (1994) Characterization of the DNA-binding properties of the myeloid zinc finger protein MZF1: two independent DNA-binding domains recognize two DNA consensus sequences with common G-rich core. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 1786–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sukhatme V.P., Cao,X.M., Chang,L.C., Tsai-Morris,C.H., Stamenkovich,D., Ferreira,P.C., Cohen,D.R., Edwards,S.A., Shows,T.B., Curran,T., LeBeau,M.M. and Adamson,E.D. (1988) A zinc finger-encoding gene coregulated with c-fos during growth and differentiation and after cellular depolarization. Cell, 53, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sogawa K., Imataka,H., Yamasaki,Y., Kusume,H., Abe,H. and Fujii-Kuriyama,Y. (1993) cDNA cloning and transcriptional properties of a novel GC box-binding protein, BTEB2. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 1527–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uchida S., Tanaka,Y., Ito,H., Saitoh-Ohara,F., Inazawa,J., Yokoyama,K.K., Sasaki,S. and Marumo,F. (2000) Transcriptional regulation of the CLC-K1 promoter by myc-associated zinc finger protein and kidney-enriched Kruppel-like factor, a novel zinc finger repressor. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 7319–7331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okano J., Opitz,O.G., Nakagawa,H., Jenkins,T.D., Friedman,S.L. and Rustgi,A.K. (2000) The Kruppel-like transcriptional factors Zf9 and GKLF coactivate the human keratin 4 promoter and physically interact. FEBS Lett., 473, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shie J.L., Chen,Z.Y., Fu,M., Pestell,R.G. and Tseng,C.C. (2000) Gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor represses cyclin D1 promoter activity through Sp1 motif. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 2969–2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adam P.J., Regan,C.P., Hautmann,M.B. and Owens,G.K. (2000) Positive- and negative-acting Kruppel-like transcription factors bind a transforming growth factor beta control element required for expression of the smooth muscle cell differentiation marker SM22alpha in vivo. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 37798–37806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brembeck F.H. and Rustgi,A.K. (2000) The tissue-dependent keratin 19 gene transcription is regulated by GKLF/KLF4 and Sp1. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 28230–28239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gidoni D., Dynan,W.S. and Tjian,R. (1984) Multiple specific contacts between a mammalian transcription factor and its cognate promoters. Nature, 312, 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ptashne M. and Gann,A. (1997) Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature, 386, 569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang W., Shields,J.M., Sogawa,K., Fujii-Kuriyama,Y. and Yang,V.W. (1998) The gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor suppresses the activity of the CYP1A1 promoter in an Sp1-dependent fashion. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 17917–17925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Philipsen S. and Suske,G. (1999) A tale of three fingers: the family of mammalian Sp/XKLF transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2991–3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kadonaga J.T., Carner,K.R., Masiarz,F.R. and Tjian,R. (1987) Isolation of cDNA encoding transcription factor Sp1 and functional analysis of the DNA binding domain. Cell, 51, 1079–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lania L., Majello,B. and De Luca,P. (1997) Transciptional regulation by the Sp family proteins. Int.J. Biochem. Cell Biol., 29, 1313–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Segre J.A., Bauer,C. and Fuchs,E. (1999) Klf4 is a transcription factor required for establishing the barrier function of the skin. Nature Genet., 22, 356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abrahamson D.R. and John,P.L.S. (1993) Laminin distribution in developing glomerular basement membranes. Kidney Int., 43, 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]