Abstract

Background

Increased levels of inflammation in cancer patients and survivors can make them more prone to muscle wasting and sarcopenia. Diet can be an appropriate treatment for alleviating patient complications. Therefore, this study was performed to determine the association between sarcopenia and its components with the dietary inflammatory index (DII) among breast cancer survivors.

Methods

A total of 223 female breast cancer survivors were included in this research at the Cancer Prevention Research Center of Seyyed Al-Shohada Hospital and the Iranian Cancer Control Charity Institute (MACSA). Forty-three items of dietary inflammatory index (DII) were extracted from the Food Frequency Questionnaire. Sarcopenia detection was performed according to the Asian criteria. The linear and binary logistic regression was used to assess the association between sarcopenia and its components with DII.

Results

Participants in the highest DII quartile had significantly elevated risk of impaired hand grip strength and calf circumference in both crude and adjusted models. Moreover, individuals consuming a more pro-inflammatory diet displayed a greater risk of abnormal appendicular skeletal muscle index in the crude model. After controlling for potential confounders, participants in the top quartile of DII had a 2.992-fold greater risk of possible sarcopenia than those in the bottom quartile (P value = 0.035). In addition, a decreasing linear trend was observed between higher DII score and 0.059 and 0.349- units lower in appendicular skeletal muscle mass index and hand grip strength variables in the crude Model (P-value < 0.05).

Conclusion

Diets with more pro-inflammatory features might be associated with increased risk of possible sarcopenia, as well as its components especially muscle mass and strength in women recovering from breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Dietary inflammatory index, Hand grip strength, Muscle mass, Sarcopenia

Background

Abnormalities in physical performance, muscle mass and function are features of a disorder called sarcopenia [1–3]. As individuals age, the risk of sarcopenia increases, with an estimated 50% of elderly individuals older than 80 years experiencing sarcopenia [4, 5]. Health background, the presence of other diseases, dietary intake, and lifestyle habits such as smoking or inactivity can influence the prevalence of sarcopenia [6–8]. In addition to aging, inflammation is a well-known cause of sarcopenia, as it disrupts normal protein turnover and leads to muscle wasting [9, 10]. Increased production of inflammatory cytokines due to tumor activity [11, 12] and cancer therapies such as chemotherapy and its side effects can further augment the risk of muscle wasting and sarcopenia in cancer patients, including survivors [13–15]. Untreated sarcopenia can ultimately affect quality of life [16], mortality rate (even in survivors) [15, 17], drug toxicity [18], increased risk of infection, and hospitalization [19].

One approach to managing sarcopenia is through proper exercise planning and addressing inflammation, as these are effective treatments [20]. Muscle health may be guaranteed by sufficient intake of nutrients such as protein, vitamin D, vitamin C, omega3, calcium, magnesium, selenium, polyphenols and other nutrients through inflammation modification [21, 22]. Among the nutrients mentioned above, it seems normal intake of protein has the best effect on sarcopenia risk reduction [23, 24]. However, the impact of individual nutrients on diet-induced inflammation can vary, with some nutrients increasing inflammation while others lowering inflammation markers [25]. Therefore, dietary intake should be considered comprehensively as a dietary pattern, taking into account the specific effects of different nutrients simultaneously [26]. In this context, dietary inflammatory index (DII) was introduced to quantified the pro-inflammatory properties of dietary intakes [25]. As claimed by a referenced study, a more positive DII represents a greater pro-inflammatory potential of the diet, while a more negative score suggests a better anti-inflammatory characteristic of the diet [25].

A recent review suggested a potential link between dietary inflammatory index and chronic diseases such as metabolic syndrome, cancer, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [27]. A previous cohort study demonstrated that a dietary pattern characterized by low inflammatory properties is related to better physical function and skeletal muscle mass in Australian men [28]. An observational study in older Australians revealed a significant relationship between a higher DII score and abnormal muscle function and mass, both in crude and adjusted models [29]. Although another observational study did not detect a relationship between DII score and sarcopenia components, it did identify a significant correlation between a more positive DII score and a greater risk of sarcopenia among elderly population [10].

Breast cancer has the highest incidence rate among other cancers [30], and to date, evaluating the relationship of DII score with sarcopenia has not been addressed by researchers in this specific target group. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the relationship between DII and sarcopenia indices in BCSs. The results of prior studies, particularly cross-sectional studies on the relationship between DII and sarcopenia and its components, have yielded inconclusive findings. Hence, the objective of our study was to ascertain the potential association between DII and sarcopenia components in Iranian BCSs.

Methods

Participants and study design

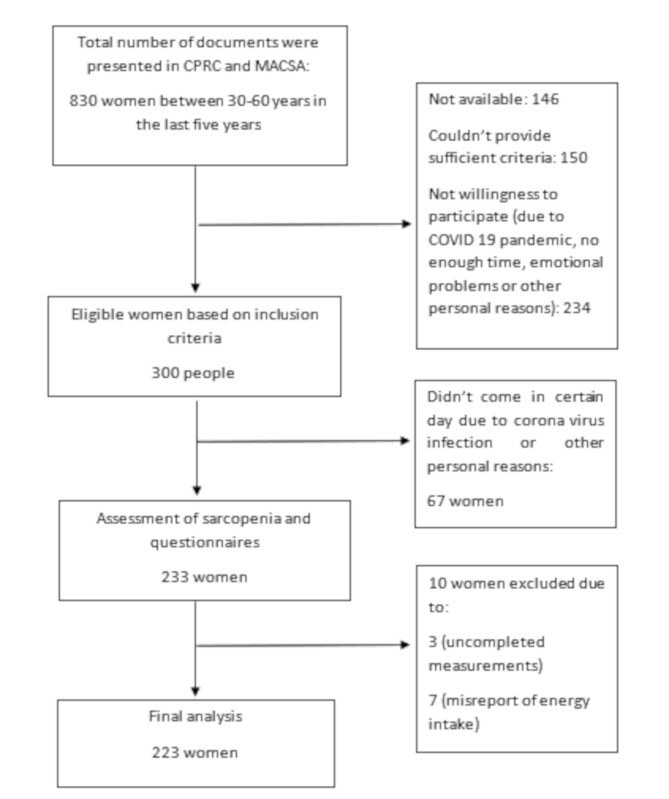

The setting of this cross-sectional study was the Cancer Prevention Research Center of Seyyed Al-Shohada Hospital (CPRC) and Iranian Cancer Control Charity (MACSA) in Isfahan between February 2022 and January 2023. The study recruited breast cancer survivors (BCSs) women who were on anti-estrogen therapy (tamoxifen, letrozole, exemestane), between 30 and 60 years and diagnosed within the last five years by their oncologist. The selection of BCSs was made based on the recorded documents in the hospital and charity that showed the patients had gotten breast cancer in the last 5 years and finished their chemotherapy and radiotherapy at the time of participation in the study. In addition, the eligible participants were women without (1) organ failure, (2) chronic diseases such as autoimmune diseases, such as AIDS, multiple sclerosis, lupus, hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, end-stage renal disease, kidney diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neurodegenerative diseases, myocardial infarction and stroke, any types of active cancers, (3) being on the chemo-radiotherapy regimes, (4) malignancies, (5) artificial organs who could not walk and (6) a planned diet in the last three months. The exclusion criteria included incomplete measurements and questionnaires and energy intake reports of less than 800 kcal or more than 4200 kcal. Based on the findings of a previous study [31], which considered skeletal muscle mass index (SMI) as the main outcome with SD equal 1, a 95% confidence interval, d equal 0.15 and the suitable formula [Z1−α × SD/d]2 and a 20% rate of loss, 205 BCSs were invited to participate in the research via a convenient sampling method. Figure 1 has depicted the selection process of BCSs. Before the start of the study, all individuals provided informed written consent. Anthropometric measurements and body composition analysis were performed for all participants. Physical activity and dietary intakes of BCSs were assessed using International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) and food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), respectively. Demographic information was also recorded. Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences assessed and approved the present study (code: IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1400.308), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Fig. 1.

Selection of study participants flow diagram

CPRC: Cancer Prevention Research Center, MACSA: Iranian Cancer Control Charity

Anthropometric measurements

Weight (kg) was quantified using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) (TANITA, MC-780MA) to the nearest 0.1 kg. Height (cm) was measured in a standing position and barefoot to the nearest 0.1 cm. Waist circumference was measured between the lower rib and iliac crest when individuals breathed normally, while hip circumference was measured at the widest part of the hips. BMI (Body mass index) was computed using the appropriate formula.

Sarcopenia measurements

According to Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) 2019 [8], the first screening for sarcopenia detection was impaired calf circumference (CC). Women stood with their legs wide apart to measure CC, and the largest part of both calves was measured twice using inelastic tape [32]. The mean of the two measurements was included in the analyses. Impaired CC was diagnosed when the value was less than 33 cm for females [8]. For muscle mass assessment, Appendicular Skeletal Muscle mass (ASM) was computed by summing the muscle masses of the upper and lower extremities using BIA (TANITA, MC-780MA) and dividing it by the height squared. Amounts less than 5.7 kg/m2 were categorized as abnormal muscle mass in females [8]. Based on the protocol described previously Krause and Mahanʼs food and nutrition care process [33] and the TANITA MC-780MA instruction manual, participants were banned from food intake (4–6 h of fasting), any strenuous exercise, wearing jewelry or clock, over hydration and dehydration. Women with any pacemaker in their body were not invited to the study. For accurate measuring, the hands and legs had to be separate. Based on the manual suggestion, using a towel between the legs can help to measure more accurately. Although no recommendation was given about measurements during the menstrual cycle in the manual, we asked the participants not to be during their menstrual cycle due to possible weight changes.

Muscle strength was measured using the Smedley handgrip dynamometer (springer-SH5002 dynamometer). A new dynamometer was purchased for this study. For participants’ convenience, the wheel under the indicator was used to adjust the handle size. Participants stood in a standing position with their arms placed next to the body without touching the body [34]. Each hand was tested twice with a 30-second rest time between each measurement. The highest recorded value was reported. According to AWGS 2019, hand grip strength (HGS) values less than 18 kg for females indicate low muscle performance [8]. Based on the AWGS 2019, the five-time chair stand test (5-CST) and usual gait speed (GS) were performed to detect any abnormalities in muscle function. Impaired performance on the 5-CST and GS tests was diagnosed when the cutoff points were ≥ 12 s and less than 1 m/s, respectively. Each trial was performed twice, and the average of the measurements was calculated [8]. Possible sarcopenia was defined as low muscle strength (hand grip test < 18 kg) and/or low physical performance (5-CST ≥ 12 s) [8].

Physical activity and dietary intake assessment

Dietary intake of BCSs was evaluated using a validated 147-item semi-quantitative FFQ. An educated dietitian completed and analyzed the questionnaire using nutritionist IV software [35]. Additional questions about spice intake were also included. A validated IPAQ-short form [36–38] was used to assess the physical activity level of BCSs during the last 7 days. Three categories were determined for physical activity: low (metabolic equivalent of task (MET).min/week < 600), moderate (600 ≤ MET.min/week < 3000), and intense (MET.min/week ≥ 3000).

Dietary inflammatory index

The DII was computed based on Shivappa 2014 [25]. The DII requires 45 food items, but in this study, 43 of the 45 items (excluding alcohol and eugenol) were used. The average amount of each item was calculated using the Iranian database [39] and USDA [40, 41] to calculate the DII. In the first step, the global mean of each item was subtracted from the individual’s consumption mean for a special item, divided by the global standard deviation (SD) to compute the z score, and turned to a percentile to reduce the effect of right skewing; the central percentile was obtained using the formula (percentile * 2) − 1. The overall food parameter-specific inflammatory effect score was then multiplied by the percentile to calculate the DII for each specific item. Finally, all DII scores were collected to determine the overall DII score. The overall DII ranged from − 8.87 (the most anti-inflammatory score) to + 7.98 (the most pro-inflammatory score) [25, 42].

Other variables

Some demographic information was collected, including age, marital and menstrual status, socioeconomic status (SES), smoking, alcohol consumption, disease and drug use, supplements, and specific data about cancer and its treatment approach. The range of SES was categorized as poor (seven to twelve), moderate (thirteen to fifteen), or good (sixteen to twenty six) based on tertiles created by SPSS.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 20, and a p value < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance. The normality of the distribution of the variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test and histogram diagrams. The mean ± SD, number, and percentage are reported for quantitative and qualitative variables, respectively. DII quartiles were used in all analyses, with the first quartile of the score considered the reference group. Analysis of covariance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests were used to compare quantitative and qualitative variables across DII quartiles.

To determine the relationships between DII and possible sarcopenia and its components, logistic regression analysis was used. The Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported for crude and adjusted age and kcal models (Model 1); age, kcal, menstrual status, socioeconomic status, IPAQ, Zoladex and Herceptin usage; cancer treatment medicine; and general medicine and supplementation and history of chemotherapy (Model 2); and all the confounders adjusted in Model 2 plus BMI (Model 3). Considering that no participants in the present study had either an abnormal calf circumference or lower appendicular skeletal muscle mass. Therefore, to quantify the potential association between these variables and DII, values lower than the median, were considered to indicate impairment and were included in the analysis. Univariate and multiple linear regression tests (adjusted for age, energy intake, SES, and IPAQ in model 1 and age, energy intake, SES, IPAQ and BMI for model 2) were applied to assess the relationship between DII, sarcopenia components.

Results

A total of 233 women were invited to participate in the study. Ten participants were excluded from the statistical analysis owing to insufficient time (n = 3) or over reporting of energy intake (n = 7). Finally, data from 223 participants were included in the analyses. The total range of dietary inflammatory index in the current study was − 6.07 to 4.04.

General information

Table 1 shows the demographic features of the study sample, presented as the mean ± SD and N (%) for continuous variables and categorical variables, respectively. Across the DII quartiles, no significant differences were found between participants, except for HER-2 (P = 0.005), Herceptin (P = 0.017), and SES (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic information of BCSs across DII quartiles

| VARIABLES | Q1)N = 55) (-6.07 to -2.31) |

Q2(N = 56) (-2.27 to -0.73) |

Q3(N = 56) (-0.7 to 1) |

Q4(N = 56) (1.01 to 4.04) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 47.51(6.95) | 47.77(6.32) | 47.36(7.88) | 49.41(6.31) | 0.368 | |

| Smoke (N) | No | 54(98.2%) | 56(100%) | 56(100%) | 55(98.2%) | 0.565 |

| Yes | 1(1.8%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 1(1.8%) | ||

| Alcohol (N) | No | 54(98.2%) | 55(98.2%) | 56(100%) | 56(100%) | 0.565 |

| Yes | 1(1.8%) | 1(1.8%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||

| Marriage | Single | 3(5.5%) | 2(3.6%) | 3(5.4%) | 3(5.4%) | 0.386 |

| Married | 41(74.5%) | 47(83.9%) | 50(89.3%) | 43(76.8%) | ||

| Other | 11(20%) | 7(12.5%) | 3(5.4%) | 10(17.9%) | ||

| Menstrual | Post menopause | 51(92.7%) | 46(82.1%) | 48(85.7%) | 44(78.6%) | 0.195 |

| Perimenopause | 4(7.3%) | 10(17.9%) | 8(14.3%) | 12(21.4%) | ||

| SES category | Low | 23(41.8%) | 11(19.6%) | 7(12.5%) | 20(35.7%) | 0.001 |

| Moderate | 14(25.5%) | 24(42.9%) | 36(64.3%) | 22(39.3%) | ||

| Good | 18(32.7%) | 21(37.5%) | 13(23.2%) | 14(25%) | ||

|

IPAQ Category (Met. min/week) |

< 600 | 34(61.8%) | 35(62.5%) | 40(71.4%) | 39(69.6%) | 0.852 |

| 600–3000 | 19(34.5%) | 20(35.7%) | 14(25%) | 15(26.8%) | ||

| ≥ 3000 | 2(3.6%) | 1(1.8%) | 2(3.6%) | 2(3.6%) | ||

| Chemotherapy (N) | Negative history | 5(9.1%) | 5(8.9%) | 7(12.5%) | 11(19.6%) | 0.28 |

| Positive history | 50(90.9%) | 51(91.1%) | 49(87.5%) | 45(80.4%) | ||

| Radiotherapy (N) | Negative history | 3(5.5%) | 1(1.8%) | 2(3.6%) | 3(5.4%) | 0.729 |

| Positive history | 52(94.5%) | 55(98.2%) | 54(96.4%) | 53(94.6%) | ||

| ER (N) | Negative | 20(36.4%) | 13(23.2%) | 18(32.1%) | 21(37.5%) | 0.358 |

| Positive | 35(63.6%) | 43(76.8%) | 38(67.9%) | 35(62.5%) | ||

| PR (N) | Negative | 25(45.5%) | 17(30.4%) | 23(41.1%) | 25(44.6%) | 0.339 |

| Positive | 30(54.5%) | 39(69.6%) | 33(58.9%) | 31(55.4%) | ||

| HER2 (N) | Negative | 39(70.9%) | 49(87.5%) | 40(71.4%) | 32(57.1%) | 0.005* |

| Positive | 16(29.1%) | 7(12.5%) | 16(28.6%) | 24(42.9%) | ||

| Zoladex (N) | Negative | 34(61.8%) | 35(62.5%) | 39(69.6%) | 43(76.8%) | 0.287 |

| Positive | 21(38.2%) | 21(37.5%) | 17(30.4%) | 13(23.2%) | ||

| Herceptin (N) | Negative | 43(78.2%) | 50(89.3%) | 50(89.3%) | 39(69.6%) | 0.017* |

| Positive | 12(21.8%) | 6(10.7%) | 6(10.7%) | 17(30.4%) | ||

| Cancer drug (N) | Nothing | 15(27.3%) | 12(21.4%) | 11(19.6%) | 25(44.6%) | 0.135 |

| Tamoxifen | 24(43.6%) | 27(48.2%) | 25(44.6%) | 20(35.7%) | ||

| Letrozole | 14(25.5%) | 15(26.8%) | 15(26.8%) | 10(17.9%) | ||

| Exemestane | 2(3.6%) | 2(3.6%) | 5(8.9%) | 1(1.8%) | ||

| Other Medicine (N) | Nothing | 24(43.6%) | 32(57.1%) | 33(58.9%) | 34(60.7%) | 0.243 |

| Metabolic | 22(40.0%) | 11(19.6%) | 13(23.2%) | 16(28.6%) | ||

| Hypothyroidism | 8(14.5%) | 10(17.9%) | 7(12.5%) | 6(10.7%) | ||

| combination | 1(1.8%) | 3(5.4%) | 3(5.4%) | 0(0%) | ||

| NSAID (N) | No | 43(78.2%) | 46(82.1%) | 48(85.7%) | 45(80.4%) | 0.77 |

| Yes | 12(21.8%) | 10(17.9%) | 8(14.3%) | 11(19.6%) | ||

| Supplement (N) | Not use | 10(18.2%) | 8(14.3%) | 8(14.3%) | 10(17.9%) | 0.715 |

| Vitamin D | 4(7.3%) | 7(12.5%) | 9(16.1%) | 11(19.6%) | ||

| CA + vitamin D | 21(38.2%) | 20(35.7%) | 24(42.9%) | 17(30.4%) | ||

| Other | 20(36.4%) | 21(37.5%) | 15(26.8%) | 18(32.1%) | ||

| History of disease(N) | Nothing | 16(29.1%) | 15(26.8%) | 23(41.1%) | 18(32.1%) | 0.553 |

| Metabolic | 10(18.2%) | 5(8.9%) | 4(7.1%) | 8(14.3%) | ||

| Hypothyroidism | 8(14.5%) | 6(10.7%) | 3(5.4%) | 7(12.5%) | ||

| Fatty liver disease | 5(9.1%) | 6(10.7%) | 5(8.9%) | 7(12.5%) | ||

| Combination | 16(29.1%) | 24(42.9%) | 21(37.5%) | 16(28.6%) | ||

Abbreviations: Q: quartile, DII: dietary inflammatory index, BCSs: breast cancer survivors, SES: socioeconomic status, IPAQ: International Physical Activity Questionnaire, ER: estrogen receptor, PR: progesterone receptor, HER-2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, NSAID: nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drug

*p value < 0.05 was considered significant

Dietary intake of participants

The DII score range in each quartile was as follow: -6.07 to -2.31 for Q1, -2.27 to -0.73 for Q2, -0.7 to 1 for Q3, and 1.01 to 4.04 for Q4. Table 2 shows the dietary intake of BCSs (mean (SD)) across DII quartiles. The mean values for all macronutrients and food groups were significantly different across DII quartiles, except for animal fat and grain intake (P = 0.534 and 0.055, respectively). By increasing DII score, dietary intakes of energy, fiber sources such as fruits and vegetables, nuts and seeds, legumes, dairy products, vegetable oils, mono unsaturated fatty acid(MUFA) and poly unsaturated fatty acid(PUFA) as the features of a healthy-rich diet were decreased. In addition, lower intakes of protein, meat and its substitute, the total amount of carbohydrates and fat were observed in the more pro-inflammatory group.

Table 2.

Dietary intake of BCSs across DII quartiles

| variable | Q1(N = 55) (-6.07 to -2.31) |

Q2(N = 56) (-2.27 to -0.73) |

Q3(N = 56) (-0.7 to 1) |

Q4(N = 56) (1.01 to 4.04) |

P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (Kcal/d) | 2532.21(532.96) | 2061.37(553.49) | 1841.13(469.38) | 1499.67(378.66) | < 0.001 | |

| Protein(gr/d) | 87.21(20.25) | 69.12(18.32) | 61.73(18.52) | 49.54(13.72) | < 0.001 | |

| Carbohydrate(gr/d) | 406.45(102.88) | 341.28(108.11) | 298.23(83.28) | 242.11(68.44) | < 0.001 | |

| Fat(gr/d) | 72.05(23.19) | 54.08(20.49) | 49.86(20.27) | 40.80(18.01) | < 0.001 | |

| Saturated fat(gr/d) | 19.05(6.33) | 15.21(6.56) | 14.39(6.60) | 11.96(6.86) | < 0.001 | |

| MUFA(gr/d) | 20.90(8.46) | 16.67(7.02) | 15.94(7.90) | 12.91(5.29) | < 0.001 | |

| PUFA(gr/d) | 15.58(7.26) | 10.78(5.70) | 10.06(5.45) | 8.41(4.20) | < 0.001 | |

| Grains (gr/d) | 431.27(186.48) | 357.33(288.05) | 356.28(174.87) | 325.69(157.67) | 0.055 | |

| Fruits (gr/d) | 716.80(300.31) | 615.16(363.35) | 450.63(215.74) | 280.95(165.95) | < 0.001 | |

| Nonstarchy vegetable (gr/d) | 477.42(244.67) | 371.21(201.87) | 258.37(121.08) | 170.43(77.71) | < 0.001 | |

| Starchy vegetable (gr/d) | 36.35(27.54) | 31.05(21.30) | 24.80(27.25) | 17.68(18.63) | < 0.001 | |

| Dairy products (gr/d) | 345.98(227.80) | 291.79(246.94) | 223.84(203.84) | 175.22(138.66) | < 0.001 | |

| Meat and substitute (gr/d) | 91.13(39.50) | 71.02(29.79) | 71.57(35.59) | 49.31(26.84) | < 0.001 | |

| Nuts and seeds(gr/d) | 22.63(16.85) | 12.88(9.56) | 10.55(6.41) | 8.72(9.48) | < 0.001 | |

| Legumes (gr/d) | 92.50(76.62) | 66.20(68.84) | 40.76(28.41) | 42.69(31.09) | < 0.001 | |

| Animal Fats (gr/d) | 6.49(11.41) | 4.66(8.32) | 3.90(9.04) | 5.47(9.61) | 0.534 | |

| Vegetable oils (gr/d) | 9.58(7.47) | 9.69(7.46) | 10.16(10.77) | 6.37(5.25) | 0.050 | |

| Sweets (gr/d) | 91.46(93.86) | 72.19(92.29) | 54.72(52.32) | 40.00(36.25) | 0.002 | |

| Other ♦ | 953.15(751.93) | 708.30(462.59) | 634.77(472.97) | 591.40(467.10) | 0.003 | |

Abbreviations: Q: quartile, BCSs: breast cancer survivors, DII: dietary inflammatory index, MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acid, PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acid

One-way ANOVA was used for data analysis

*P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance

♦Other foods include spices, tea and coffee, pickles, snacks, dressers, and organs

Anthropometric and sarcopenia measurements

Table 3 shows the anthropometric characteristics and sarcopenia measurements of the study population. As reported in Table 3, individuals in the highest quartile of DII had a body composition pattern more typical of classic malnutrition i.e., lower weight, BMI, waist and hip circumferences than those in the first quartile (P < 0.05). Additionally, women in the more pro-inflammatory quartile were more likely to have a lower calf circumference (crude and adjusted Model 1), and ASM and ASMI (appendicular skeletal muscle mass index) (crude model) than women in the first quartile (P < 0.05). Individuals in the highest DII quartile had a higher risk of impaired calf circumference, ASMI, and handgrip strength (p value < 0.05). The overall prevalence rates of possible sarcopenia, impaired calf circumference, ASMI, gait speed, five-time chair stand test, and hand grip strength were 57%, 48.4%, 49.8%, 72.6%, 48.9%, and 20.6%, respectively. The prevalence rate distributions of these items across DII quartiles are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Anthropometric and sarcopenia measurements across DII quartiles among BCSs

| variable | Q1(N = 55) (-6.07 to -2.31) |

Q2(N = 56) (-2.27 to -0.73) |

Q3(N = 56) (-0.7 to 1) |

Q4(N = 56) (1.01 to 4.04) |

P

value |

P value1 | P value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(y) | 47.51(6.95) | 47.77(6.32) | 47.36(7.88) | 49.41(6.31) | 0.368 | |||

| Weight(kg) | 75.15(11.10) | 72.27(11.29) | 72.14(10.20) | 67.09(7.94) | 0.001 | |||

| Height(cm) | 158.55(5.23) | 159.52(6.08) | 157.50(5.65) | 157.02(5.15) | 0.081 | |||

| BMI(kg/m 2 ) | 29.98(4.85) | 28.41(4.22) | 29.11(4.01) | 27.23(3.12) | 0.005 | |||

| Possible sarcopenia | Normal | 22(40%) | 30(53.6%) | 26(46.4%) | 18(32.1%) | 0.126 | ||

| impaired | 33(60%) | 26(46.4%) | 30(53.6%) | 38(67.9%) | ||||

| CC | Normal | 34(61.8%) | 28(50%) | 34(60.7%) | 19(33.9%) | 0.011 | ||

| impaired | 21(38.2%) | 28(50%) | 22(39.3%) | 37(66.1%) | ||||

| ASMI | Normal | 37(67.3%) | 22(39.3%) | 31(55.4%) | 22(39.3%) | 0.006 | ||

| impaired | 18(32.7%) | 34(60.7%) | 25(44.6%) | 34(60.7%) | ||||

| HGS | Normal | 47(85.5%) | 49(87.5%) | 43(76.8%) | 38(67.9%) | 0.041 | ||

| impaired | 8(14.5%) | 7(12.5%) | 13(23.2%) | 18(32.1%) | ||||

| 5-CST | Normal | 25(45.5%) | 33(58.9%) | 34(60.7%) | 22(39.3%) | 0.064 | ||

| impaired | 30(54.5%) | 23(41.1%) | 22(39.3%) | 34(60.7%) | ||||

| GS | Normal | 16(29.1%) | 14(25%) | 17(30.4%) | 14(25%) | 0.885 | ||

| impaired | 39(70.9%) | 42(75%) | 39(69.6%) | 42(75%) | ||||

| WC(cm) | 92.84(9.42) | 91.03(9.84) | 90.92(8.48) | 87.14(7.79) | 0.008 | |||

| HC(cm) | 108.33(8.46) | 105.63(8.27) | 107.29(8.22) | 103.08(5.95) | 0.003 | |||

| CC(cm) | 38.44(3.57) | 37.80(3.37) | 38.63(3.08) | 36.87(2.57) | 0.017 | 0.025 | 0.521 | |

| ASM(kg) | 19.05(2.01) | 18.56(2.12) | 18.35(1.86) | 17.61(1.70) | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.114 | |

| ASMI(kg/m 2 ) | 7.59(0.85) | 7.30(0.77) | 7.40(0.72) | 7.14(0.62) | 0.016 | 0.163 | 0.630 | |

| HGS(kg) | 22.41(5.12) | 21.95(4.49) | 21.69(5.09) | 19.96(5.33) | 0.057 | 0.146 | 0.206 | |

| 5-CST(s) | 12.40(3.01) | 12.01(4.43) | 11.80(3.24) | 12.68(3.79) | 0.587 | 0.593 | 0.425 | |

| GS(m/s) | 0.97(0.31) | 0.93(0. 25) | 0.93(0. 17) | 0.93(0. 19) | 0.776 | 0.897 | 0.966 | |

One-way ANOVA and ANCOVA were used for the analysis

Abbreviations: Q: quartile, DII: dietary inflammatory index; BCSs: breast cancer survivors, BMI: body mass index, WC: waist circumference, HC: hip circumference, CC: calf circumference, ASM: appendicular skeletal muscle mass, ASMI: appendicular skeletal muscle mass index, HGS: hand grip strength, 5-CST: 5-time chair stand test, GS: gait speed

A P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance

1 adjusted for age, kcal, SES, and IPAQ

2 adjusted for age, kcal, SES, IPAQ score, and BMI

Linear relationship between DII and sarcopenia indices

Based on results reported in Table 4, by increasing 1-unit in diet score, 0.059-unit ASMI and 0.349-unit HGS were decreased in crude model. No significant relationship was observed in the multiple linear Models in any sarcopenia indices.

Table 4.

Linear relationship between DII and Sarcopenia indices

| variable | Univariate | Multiple1 | Multiple2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | |

| CC | -0.195 | 0.101 | 0.054 | -0.198 | 0.130 | 0.129 | -0.045 | 0.076 | 0.556 |

| ASMI | -0.059 | 0.023 | 0.012 | -0.033 | 0.03 | 0.271 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.575 |

| HGS | -0.349 | 0.158 | 0.028 | -0.38 | 0.196 | 0.054 | -0.358 | 0.197 | 0.071 |

| 5-CST | 0.065 | 0.115 | 0.576 | 0.238 | 0.139 | 0.087 | 0.261 | 0.139 | 0.061 |

| GS | -0.007 | 0.007 | 0.329 | -0.006 | 0.009 | 0.480 | -0.005 | 0.009 | 0.565 |

Abbreviations: DII: dietary inflammatory index, CC: calf circumference, ASMI: appendicular skeletal muscle mass index, HGS: hand grip strength, 5-CST: 5-time chair stand test, GS: gait speed

♦linear logistic regression was used for the analysis

a P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance

1 Multiple linear regression was adjusted for age, kcal, SES, IPAQ

2 Multiple linear regression was adjusted for age, kcal, SES, IPAQ, BMI

OR and 95%CI between DII and sarcopenia

Table 5 shows the relationships between DII quartiles and components of sarcopenia before and after adjustment. The logistic regression results showed that participants in the last group of the DII had the greatest risk of impaired calf circumference compared to the crude and adjusted Model 1 and 2. However, after additional adjustments for confounders, this significant association disappeared in fully-adjusted model. The risk of impaired ASMI was significantly greater in the top quartile of the DII than in the reference group in crude model. According to the CC and ASMI analyses, all participants were within the normal cutoff point range (CC > 33 cm, ASMI > 5.7 kg/m2). Therefore, to determine the relationship between either CC and ASMI and the DII, the median CC and ASMI values were used. Furthermore, BCSs in the last DII group were more likely to experience impaired HGS than individuals in the reference group (crude, Models 2 and 3). After controlling for confounders, we found that BCSs who consumed a more pro-inflammatory diet than those in the first group were more likely to suffer from possible sarcopenia (p value = 0.035).

Table 5.

ORs and 95% CIs of the impaired sarcopenia components across DII quartiles among BCSs

| Variables | Q1 (N = 55) (-6.07 to -2.31) |

Q2 (N = 56) (-2.27 to -0.73) |

Q3 (N = 56) (-0.7 to 1) |

Q4 (N = 56) (1.01 to 4.04) |

P for trend♦ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | Crude | 1 | 1.619(0.761–3.445) | 1.048(0.488–2.249) | 3.153(1.451–6.849) | 0.016 |

| Model11 | 1 | 1.847(0.825–4.137) | 1.260(0.532–2.988) | 4.247(1.597–11.296) | 0.014 | |

| Model22 | 1 | 1.610(0.699–3.707) | 1.123(0.459–2.744) | 3.825(1.374–10.652) | 0.036 | |

| Model33 | 1 | 1.024(0.316–3.323) | 1.145(0.330–3.969) | 2.894(0.699–11.982) | 0.134 | |

| ASMI | Crude | 1 | 3.177(1.460–6.914) | 1.658(0.767–3.585) | 3.177(1.460–6.914) | 0.025 |

| Model1 | 1 | 3.065(1.349–6.964) | 1.559(0.656–3.706) | 2.979(1.132–7.839) | 0.137 | |

| Model2 | 1 | 2.845(1.217–6.651) | 1.446(0.592–3.534) | 2.907(1.050–8.053) | 0.182 | |

| Model3 | 1 | 2.982(0.558–15.926) | 2.281(0.415–12.534) | 1.845(0.262–12.971) | 0.849 | |

| HGS | Crude | 1 | 0.839(0.282–2.497) | 1.776(0.671-4.700) | 2.783(1.091–7.097) | 0.010 |

| Model1 | 1 | 0.791(0.250–2.507) | 1.660(0.547–5.039) | 2.342(0.704–7.789) | 0.064 | |

| Model2 | 1 | 0.858(0.262–2.804) | 1.715(0.539–5.455) | 2.883(0.809–10.276) | 0.047 | |

| Model3 | 1 | 0.864(0.264–2.825) | 1.717(0.541–5.447) | 2.962(0.824–10.651) | 0.045 | |

| 5-CST | Crude | 1 | 0.581(0.274–1.232) | 0.539(0.254–1.147) | 1.288(0.606–2.739) | 0.567 |

| Model1 | 1 | 0.768(0.340–1.733) | 0.848(0.357–2.017) | 2.373(0.892–6.313) | 0.076 | |

| Model2 | 1 | 0.815(0.341–1.945) | 0.887(0.354–2.222) | 2.538(0.869–7.414) | 0.106 | |

| Model3 | 1 | 0.822(0.343–1.972) | 0.889(0.355–2.226) | 2.572(0.873–7.575) | 0.105 | |

| GS | Crude | 1 | 1.231(0.532–2.849) | 0.941(0.417–2.125) | 1.231(0.532–2.849) | 0.797 |

| Model1 | 1 | 0.986(0.389–2.499) | 0.649(0.243–1.733) | 0.887(0.295–2.665) | 0.658 | |

| Model2 | 1 | 1.056(0.377–2.962) | 0.783(0.259–2.366) | 0.961(0.273–3.392) | 0.815 | |

| Model3 | 1 | 1.003(0.356–2.827) | 0.762(0.253–2.297) | 0.852(0.238–3.056) | 0.693 | |

| Possible sarcopenia | Crude | 1 | 0.578(0.272–1.227) | 0.769(0.362–1.633) | 1.407(0.646–3.065) | 0.295 |

| Model1 | 1 | 0.762(0.338–1.717) | 1.218(0.512–2.898) | 2.570(0.949–6.964) | 0.032 | |

| Model2 | 1 | 0.769(0.323–1.827) | 1.205(0.482–3.013) | 2.776(0.936–8.234) | 0.042 | |

| Model3 | 1 | 0.803(0.335–1.927) | 1.209(0.481–3.035) | 2.992(0.997–8.979) | 0.035 | |

Abbreviations: Q: quartile, DII: dietary inflammatory index; BCSs: breast cancer survivors, CC: calf circumference, ASMI: appendicular skeletal muscle mass index, HGS: hand grip strength, 5-CST: 5-time chair stand test, GS: gait speed

♦Binary logistic regression was used for the analysis

a P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance

1Model 1 adjusted for age and kcal

2Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 and IPAQ, SES, menstrual status, Zoladex, Herceptin, cancer medicine, other medicine, chemotherapy, supplement

3Model 3 was adjusted for Model 2 and BMI

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrated that consuming a diet with greater inflammatory characteristics may be linked to a greater risk of impairment in certain components of sarcopenia such as reduced muscle mass, physical performance, and muscle strength. After controlling the potential confounders, this significant association was held only for hand grip strength. Furthermore, individuals may experience a greater risk of possible sarcopenia after covariate adjustments. Also, a negative linear association was observed between DII, ASMI and HGS, but adjusting made these associations disappear. To our knowledge, this research is the first to examine the associations between DII scores and sarcopenia and its components in Iranian BCSs. The results of the present study confirmed this hypothesis that consuming an anti-inflammatory dietary pattern; no single anti-inflammatory nutrients; may decline the speed loss of muscle strength and possible sarcopenia as shown in fully adjusted Models.

Inflammatory cytokines can disrupt muscle development and increase protein degradation, leading to muscle loss [43]. Muscle mass loss may occur at a faster rate in cancer patients than in healthy individuals due to the complications of treatment, such as anorexia, inadequate energy, and nutrient intake [14]. Moreover, chemical medications can trigger the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and contribute to muscle atrophy [13]. Additionally, individuals suffering from sarcopenia are at greater risk of fracture [44], mortality [45], and cardiovascular disease [46] and have a lower quality of life [16]. Treatment approaches such as physical activity, which reduces inflammation [20]; consumption of certain drugs; supplements consumption such as essential fatty acids and protein; and a healthy diet can be recommended for patients suffering from sarcopenia [7].

Different nutrients can either trigger or relieve inflammation and can impact the concentrations of inflammatory cytokines [25]. The combined effect of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory nutrients on inflammatory status may be effectively assessed using an index known as the dietary inflammatory index. This approach is useful for understanding how diet and inflammation interact.

In our research, individuals in the top quartile were shown to be at increased risk of possible sarcopenia after covariate adjustment (OR = 2.992 in a fully adjusted model, P value < 0.05). In line with the results of the current study, previous observational studies have confirmed this association. Studies investigating the relationship between DII and sarcopenia, regardless of its components, have reported that patients with Crohn´s disease who consume diets with greater inflammatory potential may have a greater risk of sarcopenia (defined as low muscle mass and muscle strength) in the fully adjusted Model (OR = 9.59; p value < 0.05) [47]. Another study assessing patients with chronic kidney disease revealed that individuals in the highest tertile of DII had a 1.98 times greater risk of sarcopenia than did those in the first tertile according to the fully adjusted model (p < 0.05) [48]. In a cross-sectional study of elderly individuals in Iran, individuals in the highest DII tertile were found to be 2.18 times more likely to suffer from sarcopenia than individuals in the first tertile [10]. Although these studies have indicated an association between DII and sarcopenia, it cannot be confirmed whether different components used to detect sarcopenia are affected by DII. In summary, the results concerning the association between DII and the components are contradictory.

According to the results of the current study, a higher DII was linked to decreased muscle mass before adjustment and hand grip strength before and after adjustment in both linear and logistic regression analyses. In a recent study of patients with Crohn´s disease, individuals with higher DII had a greater odd ratio (OR) for lower muscle mass according to crude and adjusted Models. The highest C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were detected in the top DII quartile (15.55 ± 25.36 vs. 3.43 ± 7.68 mg/L, respectively). However, no significant relationship between DII and HGS results was observed in this study [47]. In patients suffering from chronic kidney disease, a higher DII was associated with higher CRP levels and lower appendicular lean mass (ALM). A 1-unit increase in DII was related to a decrease in appendicular lean mass of -0.59 kg before adjustment and − 0.5 kg in the fully adjusted model [48]. Among older Chinese individuals consuming diets with a higher inflammatory profile, greater abnormalities in muscle mass and impairments in 5-CST and GS were observed both before and after adjustment [49]. In contrast to previous studies that found an association between DII and one or more components of sarcopenia, an observational study conducted on elderly individuals in Iran found no association between diet and sarcopenia components after controlling for covariates [10]. The results of different studies on different sample sizes and groups showed that individuals with higher consumption of pro-inflammatory nutrients may be more susceptible to sarcopenia or impairment of different components.

Several explanations can mediate the potential association between inflammation induced by diet and sarcopenia. Overall, these studies have shown that a diet with fewer inflammatory features might have therapeutic effects for patients [50]. Individuals with a higher inflammatory index in their diet may also experience other problems such as a higher risk of food insecurity [51] which may be associated with sarcopenia [52]. A study on the relationship between DII, food insecurity, and hand grip strength in the Korean population indicated a dose-response relationship between DII and food insecurity. Participants at a higher risk of food insecurity experienced lower muscle strength, and as the level of food insecurity increased, the amount of hand grip strength decreased [53].

In our study, by increasing the score of DII, the intake of unsaturated fats, fruits and vegetables, grains, nuts and legumes as sources of fiber, antioxidants, and polyphenols were decreased. It was observed that regulation of oxidative stress and inflammation could be performed by polyphenols [21, 54], antioxidant agents [55, 56] and dietary fiber. A healthier diet may affect muscle through inflammation regulation that results from gut microbiota and gut-muscle axis modification [57, 58].

This study has several strengths. First, this is the first study to assess sarcopenia and its components specifically among Iranian BCSs, filling an important gap in the existing research. Second, the study considered the history of treatment approaches, and well-known confounders, which helps control for potential confounding factors. Furthermore, compared with the European guidelines, the use of Asian guidelines for sarcopenia assessment is considered more appropriate and compatible for the Iranian population. This consideration ensures that the findings are more applicable and relevant to the studied population. The choice of a validated semi quantitative FFQ is commendable. This instrument helps in obtaining more reliable data about participants’ food consumption patterns. Moreover, the effort made to utilize almost all the components of the DII (43 of 45 components were used) enhanced the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the study’s findings. However, despite these strengths, there are certain limitations that should be addressed. The primary limitation lies in the study’s cross-sectional design. As an observational study, it is unable to establish a causal relationship between variables. This design restricts the ability to draw definitive conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships. Another limitation arises from the use of an FFQ, which may be susceptible to recall bias and potential misclassification of participants. Additionally, the lack of laboratory tests for measuring inflammatory biomarkers hinders the assessment of the link between DII and inflammatory biomarkers and its potential impact on the risk of sarcopenia impairment. Incorporating such tests in future research would add valuable insights to the study. In addition, dietary consulting at diagnosis time, the type of tumor and the grade of disease might affect muscle mass and body composition. So, adjusting these variables in future studies is suggested to achieve more valuable results. Furthermore, it is crucial to acknowledge that the results of this study might be generalizable to all breast cancer survivors with similar conditions. It is recommended that further research involving other kinds of chronic diseases be conducted to gain a more comprehensive understanding of sarcopenia in diverse patient populations. For future studies to have better accuracy and strength, increasing the sample size is recommended. This approach will enhance the statistical power and enable more precise estimations of the associations between variables.

Conclusion

A more pro-inflammatory profile of diet may be related to an increased risk of impairments in physical performance, muscle mass, and strength. Incorporating more fruits, vegetables, and other foods with more anti-inflammatory features into the diet may be a beneficial strategy to prevent or delay the onset of these disabilities. However, further research is needed to fully determine the relationship between dietary inflammatory index and sarcopenia components, as The results of previous studies have not been conclusive. Additionally, larger sample sizes and studies on different populations are recommended to obtain more accurate and comprehensive results. Moreover, BCSs may be at higher risk of sarcopenia in the future when they are older or in different situations (with active metastatic disease undergoing chemotherapy). So, it would be interesting to collect medical data for several consecutive years among this population. Future research should also consider utilizing appropriate laboratory tests to measure inflammatory biomarkers and gather more detailed information about Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status at the time of participation of the sample, as well as the Tumor, Node, Metastasis (TNM) staging at baseline to reveal more accurate data. Longitudinal studies will help establish causal relationships between variables.

Acknowledgements

This study was extracted from the Msc dissertation, which was approved by the School of Nutrition and Food Science, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1400.308). We thank the Cancer Prevention Research Center of Seyyed Al-Shohada Hospital and the Iranian Cancer Control Charity Institute (MACSA), who helped us perform this study.

Abbreviations

- ASMI

Appendicular skeletal muscle mass index

- BCSs

Breast cancer survivors

- CC

Calf circumference

- CI

Confidence interval

- DII

Dietary inflammatory index

- ER

Estrogen

- FFQ

Food frequency questionnaire

- GS

Gait speed

- HC

Hip circumference

- HER-2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HGS

Hand grip strength

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IPAQ

International physical activity questionnaire

- OR

Odds ratio

- PR

Progesterone

- SD

Standard deviation

- SES

Socioeconomic status

- WC

Waist circumference

- 5-CT

5-time chair stand test

Author contributions

SSB and GA contributed to conceptualization. KSH, MK, and SSB contributed to the methodology. KSH and MSH contributed to the investigations. KSH and SSB contributed to the formal analyses, data interpretation, and writing—the original draft preparation. MSH and MK contributed resources. KSH contributed to the data curation. SSB contributed to supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. KSH, GA, MSH, MK, and SSB contributed to the writing, review and editing.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Grant number: 3400543).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1400.308). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Santilli V, Bernetti A, Mangone M, Paoloni M. Clinical definition of Sarcopenia. Clin Cases Min Bone Metab. 2014;11(3):177–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papadopoulou SK. Sarcopenia: a Contemporary Health Problem among older adult populations. Nutrients. 2020;12(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Anjanappa M, Corden M, Green A, Roberts D, Hoskin P, McWilliam A, et al. Sarcopenia in cancer: risking more than muscle loss. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2020;16:50–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Haehling S, Morley JE, Anker SD. An overview of Sarcopenia: facts and numbers on prevalence and clinical impact. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2010;1(2):129–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marhold M, Topakian T, Unseld M. Sarcopenia in cancer—a focus on elderly cancer patients. memo - Magazine Eur Med Oncol. 2021;14(1):20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rom O, Kaisari S, Aizenbud D, Reznick AZ. Lifestyle and sarcopenia-etiology, prevention, and treatment. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2012;3(4):e0024–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(3):300–e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bano G, Trevisan C, Carraro S, Solmi M, Luchini C, Stubbs B, et al. Inflammation and sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2017;96:10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagheri A, Soltani S, Hashemi R, Heshmat R, Motlagh AD, Esmaillzadeh A. Inflammatory potential of the diet and risk of Sarcopenia and its components. Nutr J. 2020;19(1):129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tenuta M, Gelibter A, Pandozzi C, Sirgiovanni G, Campolo F, Venneri MA et al. Impact of Sarcopenia and Inflammation on Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NCSCL) Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs): A Prospective Study. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Bossi P, Delrio P, Mascheroni A, Zanetti M. The Spectrum of Malnutrition/Cachexia/Sarcopenia in Oncology according to different Cancer types and settings: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2021;13(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Davis MP, Panikkar R. Sarcopenia associated with chemotherapy and targeted agents for cancer therapy. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8(1):86–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodera Y. More than 6 months of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy results in loss of skeletal muscle: a challenge to the current standard of care. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18(2):203–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villaseñor A, Ballard-Barbash R, Baumgartner K, Baumgartner R, Bernstein L, McTiernan A, et al. Prevalence and prognostic effect of Sarcopenia in breast cancer survivors: the HEAL Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(4):398–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nipp RD, Fuchs G, El-Jawahri A, Mario J, Troschel FM, Greer JA, et al. Sarcopenia is Associated with Quality of Life and Depression in patients with Advanced Cancer. Oncologist. 2018;23(1):97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang XM, Dou QL, Zeng Y, Yang Y, Cheng ASK, Zhang WW. Sarcopenia as a predictor of mortality in women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prado CM, Baracos VE, McCargar LJ, Reiman T, Mourtzakis M, Tonkin K, et al. Sarcopenia as a determinant of chemotherapy toxicity and time to tumor progression in metastatic breast cancer patients receiving capecitabine treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(8):2920–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieffers JR, Bathe OF, Fassbender K, Winget M, Baracos VE. Sarcopenia is associated with postoperative infection and delayed recovery from colorectal cancer resection surgery. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(6):931–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicklas BJ, Brinkley TE. Exercise training as a treatment for chronic inflammation in the elderly. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2009;37(4):165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S, Zhang L, Li S. Advances in nutritional supplementation for Sarcopenia management. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1189522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dronkelaar C, van Velzen A, Abdelrazek M, van der Steen A, Weijs PJM, Tieland M, Minerals. The role of Calcium, Iron, Magnesium, Phosphorus, Potassium, Selenium, Sodium, and zinc on muscle Mass, muscle strength, and physical performance in older adults: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(1):6–e113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coelho-Junior HJ, Calvani R, Azzolino D, Picca A, Tosato M, Landi F, et al. Protein Intake and Sarcopenia in older adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni Lochlainn M, Bowyer RCE, Welch AA, Whelan K, Steves CJ. Higher dietary protein intake is associated with Sarcopenia in older British twins. Age Ageing. 2023;52(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hussey JR, Hébert JR. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(8):1689–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natarajan TD, Ramasamy JR, Palanisamy K. Nutraceutical potentials of synergic foods: a systematic review. J Ethnic Foods. 2019;6(1):27. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips CM, Chen LW, Heude B, Bernard JY, Harvey NC, Duijts L et al. Dietary inflammatory index and non-communicable disease risk: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2019;11(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Davis JA, Mohebbi M, Collier F, Loughman A, Staudacher H, Shivappa N et al. The role of diet quality and dietary patterns in predicting muscle mass and function in men over a 15-year period. Osteoporos Int. 2021:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Gojanovic M, Holloway-Kew KL, Hyde NK, Mohebbi M, Shivappa N, Hebert JR et al. The Dietary Inflammatory Index is Associated with low muscle Mass and low muscle function in older australians. Nutrients. 2021;13(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasimi N, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Sohrabi Z. Nutritional status and body fat mass: determinants of Sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2019;122:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S, Kim M, Lee Y, Kim B, Yoon TY, Won CW. Calf circumference as a simple screening marker for diagnosing Sarcopenia in older Korean adults: the Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study (KFACS). J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(20):e151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrow JLRK. Krause and Mahan’s Food and the Nutrition Care process 16th Edition. Elsevier; 2023.

- 34.Benavides-Rodríguez L, García-Hermoso A, Rodrigues-Bezerra D, Izquierdo M, Correa-Bautista JE, Ramírez-Vélez R. Relationship between Handgrip Strength and muscle Mass in female survivors of breast Cancer: a mediation analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Esfahani FH, Asghari G, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Reproducibility and relative validity of food group intake in a food frequency questionnaire developed for the Tehran lipid and glucose study. J Epidemiol. 2010;20(2):150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sjöström M, Ainsworth B, Bauman A, Bull F, Hamilton-Craig C, Sallis J, editors. Guidelines for data processing analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) - Short and long forms2005.

- 37.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moghaddam MHB, Aghdam F, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Allahverdipour H, Nikookheslat S, Safarpour S. The Iranian version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in Iran: content and construct validity, factor structure, internal consistency and Stability. World Appl Sci J. 2012;18:1073–80. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nutritionist I. N-squared computing. Silverton: Nutritionist IV; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.David B, Haytowitz XW, Bhagwat S. USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods, Release 3.3 2018 [Available from: http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata

- 41.Haytowitz SBaDB. USDA Database for the Isoflavone Content of Selected Foods, Release 2.1 2015 [Available from: http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata

- 42.WILLETT W, STAMPFER MJ. TOTAL ENERGY INTAKE: IMPLICATIONS FOR EPIDEMIOLOGIC ANALYSES. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(1):17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Costamagna D, Costelli P, Sampaolesi M, Penna F. Role of inflammation in muscle homeostasis and Myogenesis. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:805172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeung SSY, Reijnierse EM, Pham VK, Trappenburg MC, Lim WK, Meskers CGM, et al. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(3):485–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu J, Wan CS, Ktoris K, Reijnierse EM, Maier AB. Sarcopenia is associated with mortality in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontology. 2022;68(4):361–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao K, Cao LF, Ma WZ, Gao YJ, Luo MS, Zhu J, et al. Association between Sarcopenia and cardiovascular disease among middle-aged and older adults: findings from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;44:101264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bian D, Liu X, Wang C, Jiang Y, Gu Y, Zhong J et al. Association between Dietary Inflammatory Index and Sarcopenia in Crohn’s Disease Patients. Nutrients. 2022;14(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Huang Y, Zeng M, Zhang L, Shi J, Yang Y, Liu F, et al. Dietary inflammatory potential is Associated with Sarcopenia among chronic kidney Disease Population. Front Nutr. 2022;9:856726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bian D, Xuan C, Li X, Zhou W, Lu Y, Ding T, et al. The association of dietary inflammatory potential with Sarcopenia in Chinese community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papadopoulou SK, Detopoulou P, Voulgaridou G, Tsoumana D, Spanoudaki M, Sadikou F et al. Mediterranean Diet and Sarcopenia features in apparently healthy adults over 65 years: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2023;15(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Daneshzad E, Ghorabi S, Hasani H, Omidian M, Jane Pritzl T, Yavari P. Food Insecurity is positively related to Dietary Inflammatory Index in Iranian high school girls. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2020;90(3–4):318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lynch DH, Petersen CL, Van Dongen MJ, Spangler HB, Berkowitz SA, Batsis JA. Association between food insecurity and probable sarcopenia: data from the 2011–2014 National Health and nutrition examination survey. Clin Nutr. 2022;41(9):1861–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim SM, Park YJ, Kim H, Kwon O, Ko KS, Kim Y et al. Associations of Food Insecurity with Dietary Inflammatory potential and risk of low muscle strength. Nutrients. 2023;15(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Aslan A, Beyaz S, Gok O, Erman O. The effect of ellagic acid on caspase-3/bcl-2/Nrf-2/NF-kB/TNF-α /COX-2 gene expression product apoptosis pathway: a new approach for muscle damage therapy. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(4):2573–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ji LL. Antioxidants and oxidative stress in exercise. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;222(3):283–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cesare MM, Felice F, Santini V, Di Stefano R. Antioxidants in Sport Sarcopenia. Nutrients. 2020 Sep 19;12(9):2869. 10.3390/nu12092869. PMID: 32961753; PMCID: PMC7551250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Kao C-C, Yang Z-Y, Chen W-L. The association between dietary fiber intake and sarcopenia. J Funct Foods. 2023;102:105437. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ticinesi A, Lauretani F, Milani C, Nouvenne A, Tana C, Del Rio D, et al. Aging gut microbiota at the cross-road between nutrition, physical frailty, and Sarcopenia: is there a gut–muscle axis? Nutrients. 2017;9(12):1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.