ABSTRACT

Objectives: To explore the experience of post-traumatic growth among parents of children with biliary atresia undergoing living-related liver transplantation.

Methods: Participants were recruited within 2 weeks of their child's transplant surgery using purposive sampling. Transcripts were analyzed using Colaizzi's descriptive analysis framework, with collaborative analysis conducted using NVivo 12 software and a post-traumatic growth model.

Results: Five themes were identified: (a) experiencing a devastating blow, (b) cognitive reconstruction under overwhelming pain, (c) an arduous journey of decision-making, (d) rebirth in adversity and (e) post-traumatic growth. Parents undergo significant post-traumatic responses to their child's diagnosis of biliary atresia and liver transplantation, marking two major traumatic events. During the diagnostic stage, parents experience intense post-traumatic reactions characterized by emotional fluctuations and intrusive thoughts. The early treatment phase represents a crucial time for parents to transition from `denial of reality' to `accepting diseases'. The process of liver transplantation is also a significant traumatic event, accompanied by a final hope. Parents in the stable period after liver transplantation feel fortunate, hopeful and grateful, and their post-traumatic growth manifests gradually.

Conclusions: Parents' experience of post-traumatic growth involves dynamic changes. Tailored intervention strategies should be developed for different stages to enhance their post-traumatic growth and psychological well-being. During the early treatment stage, mental health professionals could provide cognitive interventions to encourage parents to express their negative emotions and guide them to develop positive cognition toward traumatic events. The coping strategies and increasing personal growth are also important. In the postoperative stage, mental health professionals need to fully evaluate the coping styles of parents, and encourage them to establish effective internal coping strategies, while classic gratitude interventions could be given during the post-traumatic growth stage. Future research could involve a longitudinal qualitative study to explore parents' post-traumatic growth experiences at different stages of their children's transplantation process.

KEYWORDS: Post-traumatic growth, biliary atresia, living-related liver transplantation, experiences, mental health nursing, descriptive phenomenology

HIGHLIGHTS

The experience of post-traumatic growth among parents of paediatric living related liver transplantion presenting dynamic changes, and different responses were displayed in each stage, the child’s diagnosis with biliary atresia and receiving liver transplantation treatment are both two major traumatic events for parents, with significant post-trauma response.

A positive reassessment of traumatic event is the key for parents to perform active cognitive reconstruction, achieve a transformation from ‘denial of reality’ to ‘accepting diseases’ and move towards growth, and healthcare providers should guide them to develop positive cognition towards traumatic events.

We highlighted the importance of coping strategies and gaining personal growth. Healthcare providers should fully evaluate the coping styles of parents and encourage them to establish effective internal coping strategies, and provide targeted psychological interventions at different stages to improve their post-traumatic growth level and psychological well-being, especially those served as both donors and primary caregivers.

Abstract

Objetivos: Explorar la experiencia del crecimiento postraumático en padres de niños con atresia biliar sometidos a trasplante hepático de donante vivo.

Métodos: Se utilizó un muestreo intencional para reclutar participantes dentro de las 2 semanas posteriores a la cirugía de trasplante de sus hijos. Se empleó el marco de análisis descriptivo de Colaizzi para analizar las transcripciones. Se utilizó el software NVivo 12 y un modelo de crecimiento postraumático para el análisis colaborativo.

Resultados: Se identificaron cinco temas: (a) experimentar un golpe devastador, (b) reconstrucción cognitiva bajo un dolor abrumador, (c) un arduo camino de toma de decisiones, (d) renacer en la adversidad y (e) crecimiento postraumático. Para los padres, el diagnóstico de atresia biliar de sus hijos y el tratamiento mediante trasplante hepático, son dos eventos traumáticos significativos que implican una respuesta postraumática considerable. La etapa de diagnóstico es el periodo en el que los padres presentan las reacciones postraumáticas más intensas, con fluctuaciones emocionales extremas y deliberación intrusiva. La etapa inicial del tratamiento es un periodo crítico para que los padres logren una transformación de la “negación de la realidad” a la “aceptación de la enfermedad”. El proceso de trasplante hepático es otro evento traumático significativo para los padres, acompañado de una esperanza final. En el periodo estable después del trasplante, los padres se sienten afortunados, esperanzados y agradecidos, y su crecimiento postraumático se manifiesta gradualmente.

Conclusiones: La experiencia del crecimiento postraumático en los padres presentó cambios dinámicos, mostrando diferentes respuestas en cada etapa. Es fundamental formular estrategias de intervención específicas para cada etapa para mejorar el nivel del crecimiento postraumático y el bienestar psicológico de los padres. Durante la etapa inicial del tratamiento, los profesionales de la salud mental podrían proporcionar intervenciones cognitivas para alentar a los padres a expresar sus emociones negativas y guiarlos a desarrollar una cognición positiva hacia los eventos traumáticos. También es importante fomentar estrategias de afrontamiento y el crecimiento personal. En la etapa postoperatoria, los profesionales de la salud mental deben evaluar plenamente los estilos de afrontamiento de los padres, alentarlos a establecer estrategias internas efectivas de afrontamiento y considerar intervenciones clásicas de gratitud durante la etapa de crecimiento postraumático.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Fenomenología descriptiva, crecimiento postraumático, atresia biliar, trasplante hepático de donante vivo, experiencias, enfermería de salud mental

1. Background

Research has shown that 60% to 80% of newborns develop jaundice in the first week of life. Most neonatal jaundice is benign and quickly relieves without sequelae (Sanchez-Valle et al., 2017). However, there are some infants at risk of developing obstructive jaundice. Biliary atresia is one of the most common causes of blockage in the bile ducts and the buildup of bile in newborn babies. It is a devastating neonatal disease typically observed within 1 month after birth. Biliary atresia results in blockage of bile duct systems within and outside the liver, presenting clinically as jaundice, porcelain white stools, a darkened urine colour and the enlargement of liver and spleen (Lendahl et al., 2021). There are significant ethnic differences in its incidence, with 1/20,000 in European and American countries and 1/5000 in Asian countries (Cavallo et al., 2022; Chung et al., 2020). Left untreated, biliary atresia invariably leads to death from end-stage liver disease in the first two years of life (Zagory et al., 2019). However, despite its frequency and serious consequences, the causes and pathogenesis of biliary atresia remain unknown (Sundaram et al., 2017). The current preferred treatment method is Kasai portoenterostomy (KPE), a surgical procedure aimed at treating biliary atresia by establishing a new pathway for bile flow from the liver to the intestine. However, it does not halt the disease progression, and nearly 60% of patients encounter postoperative complications (Wan & Zheng, 2018). Ultimately, 60% to 70% of patients need liver transplantation before the age of 2 to save their lives (Nizery et al., 2016; Sundaram et al., 2017).

Paediatric liver transplantation is an effective treatment for children with end-stage liver disease, metabolic/genetic conditions and acute liver failure (Smith & Miloh, 2022). More than 10,000 paediatric liver transplantation procedures have been carried out worldwide over the last five years, and biliary atresia is the most common indication (Rodriguez-Davalos et al., 2023). By 2020, China had the highest number of cases of paediatric liver transplantation in the world, and the majority of paediatric liver transplantation recipients were infants and young children (under 3 years old) (Xia & Zhu, 2022). It is worth noting that living-related liver transplantation in children has become the main surgical method for paediatric liver transplantation due to its advantages of a favourable prognosis, high survival rate, reduced waiting time for the liver and occurrence of rejection reactions, decreased treatment costs, and ability to choose surgery according to changes in the recipient's condition (Kehar et al., 2019). With advances in surgical technology, organ preservation, the optimization of immunosuppression protocols and the treatment of complications, the survival of patients undergoing liver transplantation has increased considerably, with 5-year and 10-year survival rates of 95.5% and 93.7%, respectively (Ekong et al., 2019; Rawal & Yazigi, 2017).

The long-term course of illness, functional deficiencies, economic pressure and living burden caused by rehabilitation in children may overwhelm the emotional, cognitive, or physical coping abilities of the primary caregivers, and caregivers’ subjective reactions influence the extent to which these are traumatic or stressful events for them (van der Merwe & Hunt, 2019). Liver transplantation is a major operation associated with significant postoperative complications, such as biliary complications, infection, immune rejection, and liver failure, which makes care extremely complex and challenging for primary caregivers (Ruan et al., 2023). Moreover, children in this age group have not yet developed the cognitive abilities to understand their condition or treatment, and they require long-term care from caregivers in various aspects, such as medication management, infection control, and nutritional support; as the primary caregivers, parents always shoulder a heavy burden (Batsis et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2018). Therefore, the hospitalization of a child with a liver transplantation treatment is often a traumatic experience for parents, which may affect their mental health. Emotional involvement and the financial burden expose these parents to various physical and psychological challenges, including high treatment costs, fear of disease recurrence, feelings of helplessness and loss of control, as well as the undergoing of adverse medical procedures that might include pain and suffering (Wu et al., 2018).

Previous studies on the experience of parents of children undergoing liver transplantation, focusing mostly on the presence of their psychological distress, which includes a range of symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress (Annunziato et al., 2020; Bowden et al., 2015). Sahin et al. (2016) found that up to 65.7% of parents of children undergoing liver transplantation have psychological disorders, with depression accounting for 18.4% and anxiety accounting for 47.3%. These findings regarding the experience of stress by parents align with the definition of medical trauma (Price et al., 2016;Springer et al., 2023), which can be elucidated through the lens of the Enduring Somatic Threat model (Edmondson, 2014). However, it is broadly assumed that exposure to traumatic situations may also lead to positive psychological changes, enabling traumatized individuals to rebuild their understanding of life and themselves; conceptualized as post-traumatic growth, which may exist alongside the experience of distress (Zhang, Chang, et al., 2023). Post-traumatic growth was first proposed by Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996). It refers to the positive psychological changes that individuals experience after experiencing traumatic or stressful events (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Studies have shown post-traumatic growth is often present among parents of children with chronic illnesses, including parents of children with autism spectrum disorder, cancer, developmental intellectual disability, mixed congenital diseases or chronic pain (Alon, 2019;Byra et al., 2017; Farhadi et al., 2022;Hullmann et al., 2014). Studies have found that post-traumatic growth can effectively promote good social relationships, alleviate stress, and enhance self-efficacy, prompting individuals to adopt optimistic and problem-centred positive coping strategies to address challenges (Li et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). Therefore, exploring the post-traumatic growth of caregivers among parents of paediatric patients undergoing living-related liver transplantation may provide a new path for psychological adjustment, which is very important for maintaining their physical and mental health.

The chronic illness trajectory model was first proposed by Corbin and Strauss in 1991 (Corbin & Strauss, 1991) and was subsequently updated in 1998 (Corbin, 1998). This model holds that chronic diseases themselves are a long process, and the experiences and needs of chronic disease patients and their caregivers may vary dynamically with changes in different stages of the disease. Therefore, nursing interventions should make targeted changes according to different stages of the disease (Corbin, 1998). The treatment, care, and rehabilitation of biliary atresia are complex processes, so the experiences of parents may change dynamically with the disease stage. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the experience of post-traumatic growth among parents at different stages of treatment for children with biliary atresia to help healthcare providers pay more attention to this specific subgroup of individuals. This research will provide a basis for the development of appropriate, specific and targeted psychological interventions for this group of people at different stages.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

Descriptive phenomenological research in the tradition of the philosophy of Edmund Husserl was conducted within a constructivist paradigm (Paley, 1997). This approach was chosen to understand post-traumatic growth among parents of children with biliary atresia undergoing living-related liver transplantation by exploring their feelings, experiences, and perceptions. A phenomenological stand was adopted to explore the phenomenon as it appeared in the consciousness of the participants. The study design focused on the experience of post-traumatic growth among parents throughout the child’s diagnosis of biliary atresia to living-related liver transplantation, with a specific focus on the stage of liver transplantation, as it is a significant traumatic event for parents. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) reporting guidelines were used (Supplementary File S1) (Squires & Dorsen, 2018).

2.2. Setting and participants

This study was conducted in a liver transplant centre at a tertiary hospital in Hangzhou, China, from February 2024 to April 2024. Yearly, more than 200 children undergo liver transplantation, with the majority being diagnosed with biliary atresia on admission. A purposive sampling method was used to select the participants, and maximum variation in terms of demographic characteristics was considered. Most children in this liver transplant centre could reach a stable condition within two weeks after surgery. Therefore, to reduce the impact of post transplant time on parents’ psychological status, we recruited parents within two weeks after the child's surgery and before discharge. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed by combining team discussions and expert consultations (1 psychology professor and 1 nursing professor). The inclusion criteria for the children were (a) aged 0–3 years, (b) diagnosed with biliary atresia through laparoscopy, and (c) receiving living-related liver transplantation with stable postoperative conditions (daily evaluated after liver transplantation surgery by medical staffs through vital signs, liver function indicators, and imaging examinations). The inclusion criteria for parents were (a) aged ≥ 18 years; (b) having post-traumatic growth experience (evaluated between two weeks after the child's surgery and before discharge), which means a score of over 70 on the Chinese-Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (Tong et al., 2007); (c) primary caregivers for the child, with a daily care time of ≥ 6 h; (d) normal communication and expression skills in Chinese; and (e) volunteered to participate in this study and provided informed consent. The exclusion criteria were (1) experiencing other trauma or stress events within the first month prior to the interview and (2) having a previous or existing mental health condition or cognitive impairment.

2.3. Data collection

Face-to-face semistructured interviews were conducted in a separate, quiet consultation room near the liver transplant centre at a tertiary hospital in Zhejiang Province. Based on the chronic disease trajectory model, combined with the treatment characteristics of biliary atresia, five stages were identified: the diagnosis stage (from disease occurrence to diagnosis through biliary exploration), early treatment stage (from diagnosis to seeking preliminary treatments), decision-making stage (from decision-making to receiving liver transplantation surgery), early postoperative stage (within one week after liver transplantation), and postoperative stable stage (stable postoperative conditions). A semistructured interview protocol was drafted after consultations with two experts in paediatric liver transplant care and two experienced psychology professors. The preliminary interviews were conducted with two parents who met the inclusion criteria. The initial interview protocol was refined based on the preliminary interview findings, and a formal interview guideline was ultimately developed. Table 1 shows the interview guidelines. All of the researchers had received specific training in conducting qualitative research. The interviews were conducted in the participant’s native language (Chinese). The interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min.

Table 1.

Examples of the thematic process.

| Meaningful units | Subtheme | Main theme |

|---|---|---|

| P4: I felt like the sky was about to collapse, and I had a big lump in my heart | 1.1 Fear and despair | Theme 1: Experiencing a devastating blow |

| P6: I can't accept it. I wash my face with tears every day | ||

| P10: I lived in fear and worry every day, afraid that my child would not be cured as described online and that I would not be able to survive | ||

| P8: I can't sleep at all. As soon as I close my eyes, I will have nightmares | ||

| P12: When he was diagnosed with biliary atresia, I felt like the sky is falling |

The first author invited parents who met the inclusion criteria to participate. A total of 34 potential parents were approached. Among these, approximately half (n = 16) refused to participate in this interview because they were too upset to share their experience and wanted to focus only on caring for their children. Two mothers declined to participate since they had no time or thought it useless. Therefore, the remaining 16 parents were included in the study. The sample size was determined when saturation was reached and no new themes or concepts were identified through the data collection (Trotter, 2012). Data saturation was achieved when the data were collected from the 16th mother.

2.4. Data analysis

The recordings were transcribed word for word within 24 hours after the interview. Data analysis was conducted using NVIVO software (QST International, Cambridge, MA, USA). This study adopted the Colaizzi descriptive analysis framework (Colaizzi, 1978) divided into six analytical steps: (1) reading of interviews by two researchers who reread the transcripts several times to become immersed in the data. (2) Identifying significant statements related to parents’ experiences of post-traumatic growth. (3) Extracting meaningful fragments through team discussions. (4) Organizing each significant statement into meaningful units and subthemes into major themes. (5) Linking themes closely to the research phenomena and providing a detailed explanation of them. (6) Providing feedback on the results to participants to ensure the authenticity of the content. Examples of the thematic process are given in Table 1.

2.5. Bracketing, reflexivity, and rigour

We ensured that the interview questions were neutral and open-ended to allow participants to share their views on their experiences. The first author, who is an experienced PhD-qualified nurse conducting research in the paediatric liver transplantation area and is interested in mental health among parents of children undergoing liver transplantation, performed the interviews. Relationships between the interviewers and participants were established when enrolling them in the study. The two authors analysed the data and differences in interpretations were resolved by team discussion until a consensus was achieved. Therefore, the risk of imposing personal opinions on the analysis was reduced. The credibility and originality of the analysis were preserved by collecting rich, in-depth data from the interviews, transcribing verbatim using the participants’ own words, and ensuring that our interpretations of the data were extracted from and evidenced by paradigm extracts from the interview data (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outline of the interview.

| Interview questions |

|---|

| (1) What are your experience and feelings of your child being diagnosed with biliary atresia? |

| (2) What are your experience and feelings during the early process of your child’s treatment? What psychological changes did you experience during this time? Have you made any positive changes? |

| (3) What are your experience and feelings about your child receiving liver transplantation treatment? What psychological changes did you experience during this time? Have you made any positive changes? |

| (4) In the process of experiencing a family illness, what are some of the difficulties and pressures you have experienced, and how do you deal with them? what psychological changes did you experience during this time? |

| (5) What is the most important thing for you now? |

| (6) What are your plans for the future? |

| (7) If you encounter parents with similar experiences to you, what advice do you have for them? |

3. Results

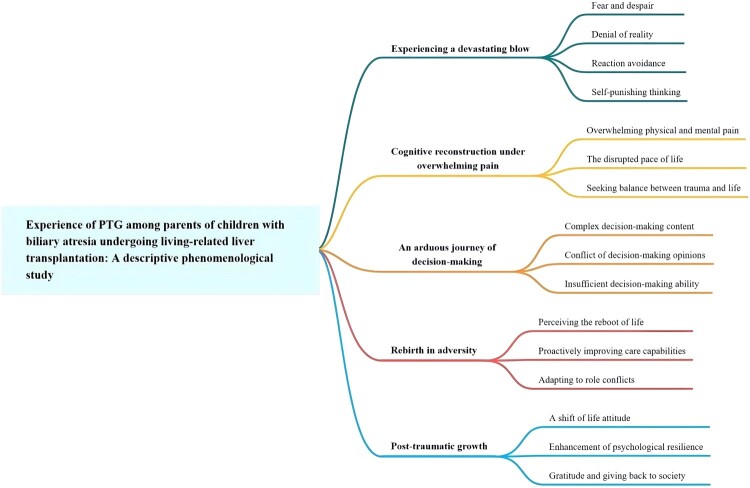

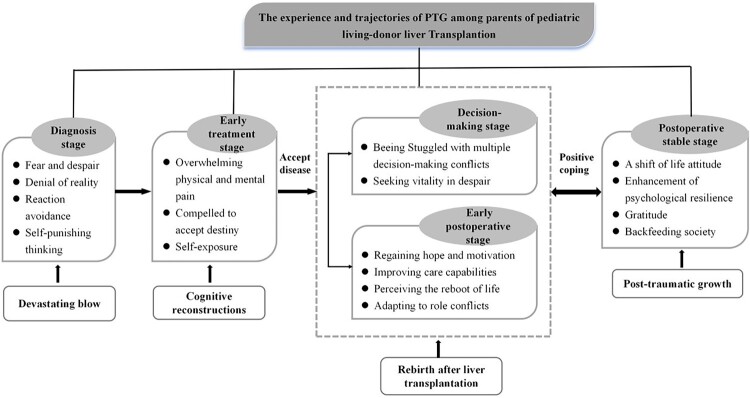

A total of 16 participants were interviewed, including 14 mothers and 2 fathers. The median age was 30.25 ± 3.86 years, and 87.5% of the patients were donors. The post-traumatic growth score of the parents ranges from 70 to 82, with an average score of 75.12 ± 3.36. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 3. Figure 1 provides a summary of the key themes and subthemes identified in relation to the experiences in this research. The following experiences and processes of post-traumatic growth (Figure 2) were formed according to the experiences of the participants. A traumatic response was observed throughout almost the entire research process. The cognitive reconstruction started roughly in the early treatment stage, which is an important stage for parents to ‘accept the disease’. Positive coping usually starts in the early stage after living-related liver transplantation surgery and gradually manifests during the postoperative stable period.

Table 3.

Sociodemographics of participants.

| No. | Relationship | Education | Age (years) | Donor | Occupation | Marital status | Average monthly income (Yuan) | Age (months) | KPE | Length of diagnosis | Time post-transplant | Post-traumatic growth score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Mother | Middle school education | 32 | Yes | Private sector employee | Married | 3000–5000 | 9M | Yes | 8M | 6d | 70 |

| P2 | Father | High school diploma | 22 | Yes | Unemployed | Single | 3000–5000 | 7M | No | 7M | 9d | 74 |

| P3 | Mother | Middle school education | 32 | Yes | Unemployed | Married | <3000 | 7M | No | 6M | 8d | 71 |

| P4 | Mother | Junior college | 35 | Yes | Private sector employee | Married | <3000 | 12M | Yes | 12M | 10d | 76 |

| P5 | Mother | High school diploma | 34 | Yes | Unemployed | Married | 5000–7000 | 8M | Yes | 6M | 12d | 73 |

| P6 | Mother | High school diploma | 28 | Yes | Farmer | Married | 3000–5000 | 7M | Yes | 6M | 11d | 76 |

| P7 | Mother | High school diploma | 26 | No | Unemployed | Married | 3000–5000 | 9M | Yes | 9M | 8d | 78 |

| P8 | Mother | Junior college | 29 | Yes | Private sector employee | Married | 3000–5000 | 18M | Yes | 16M | 10d | 71 |

| P9 | Mother | Undergraduate | 32 | Yes | Unemployed | Married | 5000–7000 | 9M | Yes | 8M | 7d | 82 |

| P10 | Mother | High school diploma | 26 | Yes | Others | Married | 3000–5000 | 8M | No | 6M | 10d | 75 |

| P11 | Father | High school diploma | 30 | Yes | Unemployed | Married | 5000–7000 | 9M | No | 7M | 9d | 75 |

| P12 | Mother | Junior college | 28 | No | Private sector employee | Married | <3000 | 10M | No | 9M | 8d | 72 |

| P13 | Mother | Postgraduate | 31 | Yes | Unemployed | Married | >7000 | 6M | No | 6M | 6d | 74 |

| P14 | Mother | Junior college | 35 | Yes | Others | Married | 3000–5000 | 12M | Yes | 12M | 7d | 77 |

| P15 | Mother | High school diploma | 28 | Yes | Unemployed | Single | <3000 | 14M | Yes | 14M | 9d | 78 |

| P16 | Mother | Undergraduate | 36 | Yes | Civil servant | Married | 3000–5000 | 8M | No | 6M | 8d | 80 |

Figure 1.

Summary of themes and subthemes.

Figure 2.

The experience and processes of post-traumatic growth among parents of children with biliary atresia undergoing living related liver transplantation.

3.1. Theme 1: experiencing a devastating blow

When the doctor declared that the child had been diagnosed with biliary atresia, the parents’ psychological defense line instantly collapsed, and the child was surrounded by negative emotions, including fear, despair, shock, doubt, helplessness, and worry, resulting in a series of psychological stress stages such as denial of reality, avoidance reactions and self-punishing thinking.

3.1.1. Fear and despair

Because the incidence rate of biliary atresia is low, parents lack knowledge of this disease. At the initial stage of diagnosis, the parents are full of fear and despair. Most parents used ‘feeling the sky is falling’ and ‘washing their face with tears’ to describe their despair and helplessness at the time of diagnosis.

I have never heard of biliary atresia. The hospital we checked in had only our child with biliary atresia in the entire building. I felt like the sky was about to collapse, and I had a big lump in my heart. (Par 4)

I can't accept it. I wash my face with tears every day. Since I knew he was diagnosed, I couldn’t sleep for a while. When I slept, I felt flustered and scared. (Par 6)

Faced with descriptions such as ‘incurable’, ‘terminal disease’ and ‘unable to survive for a year’ of biliary atresia on the internet, parents pessimistically believe that the child has no hope of survival and they become trapped in multiple negative emotions that they cannot extricate themselves from. The parents experience symptoms such as anxiety, insomnia, and weight loss, leading to physical and mental exhaustion.

Less than ten days of her diagnosis, I lost about 10 pounds. I lived in fear and worry every day, afraid that my child would not be cured as described online and that I would not be able to survive. (Par 10)

It is said online that this disease is very serious. If don't have a liver transplant, the baby may not live to be one year old. I am really afraid that the baby will suddenly leave me. During that time, I can't sleep at all. As soon as I close my eyes, I will have nightmares. (Par 8)

3.1.2. Denial of reality

From the joy of having a child to learning that the child has been diagnosed with biliary atresia and must undergo liver transplant surgery to have any hope of survival, parents found it difficult to accept, resulting in complaints, paranoia, and other manifestations.

All the examinations are normal. Since he was born, except for a slightly yellowish skin, everything has been normal. My eldest son also had physiological jaundice at that time. We never expected him to suffer from this disease. (Par 10)

Serious descriptions from doctors and the internet cause parents to instinctively reject the diagnosis of suspected biliary atresia. Some parents expressed that they prayed before diagnosis, hoping that it was a doctor’s misdiagnosis and praying that their baby did not suffer from biliary atresia.

During the first examination, the doctor told us that the baby was suspected of biliary atresia and needed abdominal puncture to be diagnosed. We did not believe, so we went to other large hospitals for consultation. Every time I hold onto a glimmer of hope. (Par 7)

3.1.3. Reaction avoidance

Children with biliary atresia present with systemic jaundice, especially their eyes, which darkens over time and is known as the ‘Minions’. Moreover, the child's body is thin and small, and in severe cases, the condition can lead to liver and spleen enlargement, resulting in abdominal distension. Due to differences in appearance from that of normal children and insufficient awareness of biliary atresia, some parents have reported that their children have always been subjected to unusual looks from neighbours, elderly individuals, and members of society after birth.

At that time, my baby was very yellow, and no one dared to hold her. Once, I carried her out, others pointed at her, and they didn't dare to approach the baby, as if afraid of being infected. (Par 11)

To avoid social prejudice and discrimination against their children, parents instinctively refused to mention their child’s illness to others, chose to avoid social activities, and even left society.

We didn't dare to tell others that our child had this disease, fearing that they would be discriminated against. When we said that our child had this disease, they were afraid of being infected and didn't even dare to let their children come to your house to play. (Par 14)

A few days ago, a charity fundraiser asked me to post a message on my social media to raise funds, but I didn't agree. I was worried that when my child grew up, it would be a big blow for them if they found out that he had this disease. (Par 5)

Some parents felt a sense of shame due to the illness of their child, fearing that others may look down on them and have different opinions.

I have a strong sense of self-esteem and don't want others to know that my child has this kind of illness, sympathizing with me, and being afraid of being laughed at. Every time the doctor talks about my child's condition in the presence of others, I feel like others are looking at me with a strange gaze. (Par 3)

3.1.4. Self-punishing thinking

Because biliary atresia is a congenital disease and its initial symptoms are similar to those of physiological jaundice, it is difficult to identify early. Most parents treated it as physiological jaundice and easily attributed delayed medical treatment to themselves, leading to negative emotions of guilt and self-blame.

At first, I thought it was physiological jaundice, so I didn't take it to heart or take her to the hospital for examination in a timely manner. If only I could take her for treatment earlier, maybe she wouldn't be so serious. (Par 16)

The cause of biliary atresia is unknown, the incidence rate is low, and the diagnosis is made after the birth of the child. The parents could not find the cause of the disease; they began to doubt and deny themselves, often falling into repetitive and confused thinking.

All of my tests are normal, including DNA testing. I suspected that there might have been some issues with taking care of him, whether it was due to my husband smoking and drinking, whether it was eating anything unhealthy during pregnancy that caused the child to not develop properly. Others said it may have been due to breastfeeding, so I really regretted breastfeeding him. If I hadn't insisted on breastfeeding him, wouldn't the baby have been like this. (Par 11)

3.2. Theme 2: cognitive reconstruction under overwhelming pain

In the early stages of treatment, parents sought and compared authoritative experts in the field of biliary atresia from all over the country, hoping to determine the best treatment plan. However, the parents lost confidence over and over and experienced despair and fatigue along with the repeated worsening of the child’s condition, continuously struggling and hesitating in choosing to give up or continue treatment. The pain was overwhelming at this stage, but parents’ perception of the disease became more objective through a series of cognitive reconstructions, such as downward comparison, self-exposure, and reduced expectations to achieve a transformation from ‘desperate collapse’ to ‘gradually accepting disease’.

3.2.1. Overwhelming physical and mental pain

Given the unknown factors and uncertainty of diseases, some parents may have faced the problem of short-term or ineffective treatment effects. Due to the uncontrollable conditions, parents may experience negative emotions such as anxiety and irritability and eagerly hope that the child's illness will be relieved as soon as possible.

In fact, I was quite anxious and anxious throughout the treatment process. I hoped the baby will recover soon. I didn't want to see the child suffer like this all the time. (Par 9)

For most parents, in the early stages of treatment, kasai portoenterostomy provides hope for a cure, but many children experience recurrence after a period of postoperative relief. For parents, the hopes they once had are shattered, they feel fearful, and they may become pessimistic and desperate due to the repeated relapses of the child’s condition. Faced with the unknown factors and uncertainty of diseases, most parents expressed the dual burdens of physical and psychological pressure in caring for their children.

The recovery was quite good one month after the kasai portoenterostomy surgery. At that time, we thought the baby would recover soon, but then there was a fever. Then he repeatedly developed cholangitis and was hospitalized repeatedly. At that time, I was really desperate. If it weren't for my husband being by my side, I really couldn't hold on. (Par 2)

In this study, more than half of the respondents stated that the sick child is not an only child, and parents tended to focus most of their time and energy on the sick baby while neglecting the care of their other children, resulting in feelings of guilt.

Since my second child fell ill, we have been fully focused on him, and her brother has been ignored. I didn't have time to manage his studies, and I didn't participate in his school activities. I actually feel very guilty about my eldest child. (Par 15)

3.2.2. The disrupted pace of life

The original lifestyle of the parents was disrupted by the onset and treatment of the child’s illness, and they had to gradually change their previous lifestyle to adapt to the child's treatment. This mainly included two aspects: ‘delaying work’ and ‘being forced to isolate from society’.

Some parents expressed that to better care for their babies, they took frequent leave or were forced to resign, or they had no choice but to change their job.

I took a leave of absence from the company after discovering that my baby was abnormal. If the baby does not recover in the future, I can only temporarily resign from work. (Par 1)

Due to the limitations of the child’s illness and work delays, parents began to have a different pace with others, their social status changed, and they gradually became ‘forced to isolate themselves from society’.

I am currently working full-time at home to take care of my baby. Sometimes my friends ask me to go shopping, but I dare not go out because once I go out, there is no one to take care of my child. (Par 16)

I saw that many babies were infected with the cytomegalovirus, and I was very worried. So, to avoid infection, we didn't dare to take her out during that time. We also try to avoid going out, because we are afraid that we may carry the virus and infect the baby. (Par 15)

3.2.3. Seeking balance between trauma and life

With their increasing understanding of the disease, the parents had become increasingly aware that the disease cannot be avoided and has changed. Some parents believed that the illness is a fate arranged by heaven. Since it has already happened, they can only accept it, revealing a powerless sense of destiny that ‘cannot be changed’ and ‘can only be accepted’.

It is destined to go through this disaster, and there is no way to complain. We can only accept it. We don't know how far we can treat it, but now we can only take one step at a time. All I can do now is to check up on time, follow the doctor's advice, and do my best to take care of the baby. (Par 6)

They constantly sought a balance between trauma and life. Mothers typically used downward comparisons, comparing their situation to those of mothers they knew who were in less favourable positions, in confirming that overall, they felt lucky. (Par 7)

I saw that some babies have much more severe symptoms than my baby on the internet, but they are all actively receiving treatment, which made me suddenly enlightened. (Par 4)

With the increase in disease awareness, parents realized that their children had at least hope for treatment; therefore, their attention began to shift from ‘rarely diagnosed diseases’ to ‘hope for treatment’.

Now the medical technology is very advanced. I didn't know how long he can live after surgery, but it's always better than not having surgery. As long as he can live, it's the best, at least it gives him hope. (Par 9)

Some parents sought comfort and confidence by seeking positive information.

I have seen some examples of successful treatment online and in patient groups, where they could eat and go to school like normal children, and some even get married and have children. I felt confident and believed that my baby can also recover well. (Par 6)

To transfer and alleviate negative emotions such as pain, sadness, and fear, some parents adopted various methods of psychological adjustment, such as sharing their experiences with family and friends and shifting their attention.

When I'm sad or under a lot of pressure, I go talk to my sister. Every time I finish talking, I feel a little better and have more courage to face it. (Par 1)

3.3. Theme 3: an arduous decision-making journey

Although liver transplantation is an effective treatment for biliary atresia, due to its enormous trauma and their insufficient knowledge, parents consider it the last resort in the face of no alternative. As liver transplantation decisions involve significant changes in the lives and well-being of the child, parents may face various decision-making conflicts and experience anxiety, pain, and conflicting emotions.

3.3.1. Complex decision-making content

The decision-making involved in liver transplantation mainly included whether to undergo liver transplantation surgery, the selection of the surgical time, the selection of organ sources, and the evaluation of surgical risks and effects. Because most of these children are under 1 year old, parents are overly worried about whether the child can tolerate surgery and the postoperative prognosis, especially for those who have previously undergone surgery with Kasai portoenterostomy.

She has already undergone surgery once before, how can she bear it? I heard that it may not necessarily improve after it is done. We are very contradictory, as we are really afraid that the child will suffer again but finally not recover well. (Par 10)

The choice of surgical method-‘waiting for a cadaver liver’ or ‘living related liver’ increased their decision-making uncertainty. Compared with a cadaver liver, living-related liver transplantation has the advantages of shortening the liver transplant waiting time, reducing rejection reactions, and increasing survival rates. However, it may have certain impacts on the donor’s health and life. Most parents are trapped in the process of analysing, comparing, and evaluating the risks and benefits of different treatment methods, making it difficult to make decisions.

If we use a cadaver liver, it will take a long time to wait, and we are also concerned about whether there is a defect of the liver. However, if I give her part of my liver, I am also worried about whether it will affect my work. I do physical labor, and what should I do if I lose my job? It is very contradictory and anxious. I don't know how to make a decision. (Par 12)

The selection of transplant donors increases the difficulty of decision-making, making it difficult for family members to make decisions.

My family didn't agree me as the donator. They were worried that I had just finished a cesarean section and my body can't bear another surgery. My parents in law wanted to donate their liver, but they might be too old to withstand the surgical trauma and their liver might not be good. (Par 9)

I wanted to transplant my liver, but due to disagreements with my wife, she left for a long time. At that time, I was a bit tempted to give up. (Par 11)

3.3.2. Conflicts of decision-making opinions

Before undergoing liver transplantation, parents and family members usually comprehensively considered factors such as the child’s health status, the success and risk of the surgery, and the family’s economic capacity and weighed the pros and cons. Family members were prone to different opinions, which increased the degree of decision-making conflict.

This is a life, we can't just give ups. I insist on treating, but my parents in law are unwilling. They say that even after surgery, the child may not be able to recover, and the child will continue to suffer in the future. My husband is also wavering now. (Par 2)

My family advised us not to treat him anymore. Only me who insists on treating him, and no one supports me. I feel helpless and suffocated. (Par 8)

Living-related liver transplantation often involves decisions from two families, and due to a lack of awareness, most families, especially elderly people, believe that it is a ‘life for life’ procedure.

At first, both my parents and my parents in law did not agree us to donor the baby a liver, they thought that we were still young and could still regenerate, but my wife could not accept. If transplantation, the child is suffering, and we are also suffering. This decision is too difficult … For so long, his mother and I are really losing our support. (Par 10)

No one could understand why you chose to donor part of your liver, thinking that I had to exchange my own life for his own. (Par 3)

Due to the complexity of treatment, complications may occur in children undergoing liver transplantation, resulting in high hospitalization costs for families. Even during the stable period, the child will still need regular follow-up and long-term medication. This enormous economic burden led to parents becoming more conflicted and anxious when making decisions.

After liver transplantation, the regular follow-up examinations, hospitalization, and medication were all significant costs. If she had serious complications, the treatment cost would be astronomical for us, and we couldn't afford. (Par 14)

3.3.3. Insufficient decision-making ability

The information sources for liver transplantation treatment and prognosis are extensive, and due to limited channels and time for obtaining professional information through medical staff, the information obtained is not comprehensive, making it difficult for parents to make effective decisions.

The doctor gave us a rough overview of liver transplant treatment, but didn't say much. We were still very confused, but it's also impossible to go to the hospital and ask the doctor every time. (Par 6)

Some parents expressed that they would obtain more information through communication with friends and peers, the internet, and other means. However, due to the complexity of the treatment and the diversity of information, parents found it difficult to obtain accurate information.

Some relatives and friends suggested going to this hospital for treatment, while others suggested going to another hospital. We have visited many hospitals and added many doctors on WeChat, but different doctors gave us different treatment plans, and we didn't know which one is the best. (Par 9)

The influence of cases plays a suggestive role in the decision-making process, and whether it is a successful or failed treatment case will become a reference for parents when making decisions.

One mother told us that her baby has recovered very well after living-donor liver transplantation. However, we have also seen many cases of poor prognosis online, and we have been unable to make up our minds whether to do the transplantation or not. (Par 2)

3.4. Theme 4: rebirth under adverse conditions

After receiving living-related liver transplantation, the child’s condition gradually improved, and the jaundice gradually subsided. Parents believed it as the beginning of a child’s second life and regained hope and motivation. With the support of family, friends, peers, and society, the parents actively coped with the multiple pressures of taking care of their children, adjusted themself at the psychological and behavioural levels, and promoted the process of adaptation.

3.4.1. Perceiving the reboot of life

After liver transplantation surgery, as the jaundice gradually subsided and the indicators of liver function gradually returned to normal, parents realized that their baby is ‘no different from a normal child’ and regained hope and motivation.

As the examination indicators gradually improve, I feel that my baby is gradually becoming normal. Now I think this disease doesn't seem so scary anymore. I am now full of confidence. In the future, all I need to do is listen to the doctor and take good care of the child. (Par 7)

Parents viewed the living-related liver transplantation surgery as a turning point in the child’s and their own ‘second life’ and as an important part of their own life meaning.

After the surgery, my baby began to turn white. I saw him so white for the first time since he was born, and as him gradually return to normal, I felt like giving my baby a second life. (Par 4)

The first time I went to the intensive care unit to visit my baby, I saw her smiling at me. I felt like she was saying thank you, Mom. At that moment, I think everything I did was worth it. (Par 1)

3.4.2. Proactively improving care capabilities

The care of children after liver transplantation is complex and challenging, especially in the early postoperative period when there are often multiple channels in the child’s body, including gastric and abdominal drainage tubes, and there are strict restrictions on feeding and medication. Faced with multiple caregiving burdens, parents relied on experience and effort to make adjustments and changes, thereby enhancing their caregiving abilities.

The dosage and time of medication for babies after surgery are relatively fixed, which is difficult for us to control at first. When the nurse told us, our brain was quite dizzy, and it was a bit difficult to remember too much medication. Later on, we gradually came up with a solution, took notes, set the alarm, and gradually adapted to it. (Par 12)

Some parents reported that they would learn disease-related knowledge and actively seek help to prevent the occurrence of complications.

The doctor said that in the first three months after surgery, it is important to avoid infection as much as possible. Therefore, I learned some information on preventing infection and pay attention to various examination indicators every day. At first, I couldn't understand the baby’s examination indicators at all. After the doctor explained it, I still didn't quite understand it. So I kept learning the information on the internet. (Par 14)

3.4.3. Adapting to role conflicts

Considering that the fathers were the main source of family income, mothers were the main donors of living-related liver transplants. For mothers, liver transplantation is also an undeniable surgical trauma. However, due to a lack of caregivers or concerns about inadequate care from other caregivers after surgery, they must personally take care of their children, ignoring their own donor identity, resulting in conflicts between the roles of donors and caregivers.

At the beginning, there was a slight pain in my waist, and I couldn't stand for a long time. My body was easily fatigued, and sitting for a long time would also cause pain. (Par 11)

Some parents actively responded to the role conflict of the donor by changing their communication attitude, understanding each other, and supporting each other.

My husband and I will listen to each other and guide each other. After the operation, he is basically taking care of the baby. If he is too tired, I will say some caring words. Sometimes when he is in a good mood, I will also confide in him. (Par 7)

3.5. Theme 5: post-traumatic growth

The diagnosis of biliary atresia and receiving liver transplantation surgery, two major traumatic events that cause pain and hardship to parents, is also an opportunity to encourage them to use their own resources, reconstruct their sense of meaning and self-worth through a series of cognitive processes and psychological adjustments, and ultimately achieve post-traumatic growth. This mainly manifested in ‘a shift of life attitude’, ‘enhancement of psychological resilience’, and ‘gratitude and giving back to society’.

3.5.1. A shift in life attitude

After experiencing these traumatic events, parents changed their attitude toward life and rearranged their priorities. Some parents talked about adjusting their original focus of life, shifting from career to health and family.

Now I think it's good for children to be healthy and safe. Health is really more important than money and education. You can earn money even after it's gone, but health only comes once and cannot be exchanged by money. (Par 3)

I have decided to make good arrangements for my work and rest. Spending more time taking care of myself and my family is more important than spending time on work. (Par 7)

Some parents believed that ‘living is value’ and no longer insisted on pursuing their children's other values.

Since my second son fell ill, I feel that it’s enough for my eldest son to be healthy and alive. I don't have such high expectations of him anymore. In the past, I used to force him to study and enroll him in various tutoring classes, but now I don't force him anymore. (Par 9)

3.5.2. Enhancement of psychological resilience

In the process of struggling with their children's illnesses, parents gradually enhanced their psychological resilience and became stronger, more positive and more optimistic.

At first, when she drew blood, I cried every time. Later on, I gradually got used to it and my ability to handle it became stronger. Now I can watch him draw blood. (Par 11)

I now feel that everything is hopeful and there is a possibility of change. When facing difficulties, I will take the initiative to adjust and overcome them. The fact is that I can only adapt to it. There is always hope and a way to change it. (Par 8)

Some parents stated that their temper and personality gradually changed, becoming more patient.

I used to have a quick temper, but now I have become more patient and won’t always complain like before. (Par 10)

3.5.3. Gratitude and giving back to society

Taking care of the child became a common goal for family members in order promote their recovery. For this reason, family members supported each other and strengthened their communication. Parents conveyed that they had closer relationships with family members and that they cherished their families more after their experiences.

My mother-in-law and I used to have a very bad relationship. Since the child fell ill, our communication has increased and our relationship has also eased. (Par 13)

In the present study, the parents were grateful to their family, friends, peers, medical staff and society.

We are particularly grateful for the hospital's funding support, which has helped us solve a great economic problem. The doctors here are really good, even if our baby has a fever and sends messages to him, they always reply to me as soon as they have time. (Par 6)

In addition, parents sympathized with other families with similar experiences, actively helped them acquire disease knowledge, reduced their care pressure, encouraged them to bravely face the disease, and helped them avoid detours in the process of disease treatment.

When encountering inexperienced mothers or fathers, I will actively share my baby’s treatment and care experiences with them, telling them what to pay attention to. Previously, there was a mother whose baby was getting yellow and thinner, and she cried every day. I told her to have a good mindset, not to worry or be afraid, and focus on taking care of the baby. (Par 3)

4. Discussion

This study revealed that the psychological experiences of parents underwent dynamic changes during 5 stages from their child’s diagnosis of biliary atresia to the stable period after liver transplantation. These various stages were not fixed, as the parents experienced diverse and complex emotions in most stages of the process, which is consistent with the theory of post-traumatic growth. The themes we generated represented common psychological responses over a certain period.

Consistent with previous research (Zhang, Hu, et al., 2023), the initial diagnosis stage is the period when the parents had the strongest post-trauma response, and the parents usually had strong emotional fluctuations that generally manifested as experiencing negative emotions, denying reality, reaction avoidance and self-punishing thinking. With low public awareness of biliary atresia, families received less understanding and support from society in the early stages, and parents were prone to experiencing negative psychological emotions such as fear, helplessness, self-blame, and stigma. The low incidence of biliary atresia, its similar symptoms to neonatal jaundice, its complex diagnosis and insufficient awareness make it difficult to identify it earlier and normally cause delays in diagnosis and treatment. Research has shown that early diagnosis and surgery performed in infants <60 days old results in better outcomes, specifically improving survival in infants with a native liver (Superina et al., 2011; Zhang, Chang, et al., 2023). Paediatric healthcare providers are responsible for the timeliness of the workup and referral of biliary atresia patients, yet surveys have demonstrated an overall gap in the knowledge of diagnosing, evaluating and managing biliary atresia among paediatricians (Fawaz et al., 2017). Therefore, to decrease morbidity and healthcare costs and increase survival, improvements should be made to improve awareness of the guidelines on cholestatic jaundice and the appropriate timing of testing and referral to identify biliary atresia in a timely fashion.

Previous studies have shown that post-traumatic growth often coexists with significant psychological distress (Hasosah, 2021; Wang et al., 2022). The results of this study showed that the early treatment stage was considered to be the darkest and most difficult by most parents. At the early stage of treatment, parents endured overwhelming physical and mental pain, and pessimism, irritability, despair, fatigue and anxiety were the most common psychological manifestations of this period. Under such high-intensity psychological pressure, parents gradually changed their attitudes toward the disease. They sought a balance between trauma and life through a series of cognitive reconstructions, such as downward comparison, self-exposure, and reduced expectations, and developed a consciousness of fighting against the disease in their children. The ABC theory of emotions holds that trauma or stress events are not directly related to negative emotions; rather, incorrect subjective judgment and cognition of the event are the main reasons for negative emotions (Abdollahpour et al., 2018), which indicates that a positive reassessment of traumatic events is the key for parents to accept reality and move toward growth. Therefore, more attention should be given to the negative psychological experiences of parents, and cognitive interventions such as narrative writing and mindfulness therapy can be carried out by mental health professionals to encourage them to make appropriate self-disruptions of their traumatic reactions and express their painful emotions. Moreover, parents should be guided to develop positive cognition toward traumatic events and promote psychological growth through relevant awareness and education, including the citing of successful cases and shared peer experiences.

In the decision-making stage, the enormous trauma of surgery, complexity of treatment, uncertainty of prognosis, and high cost of treatment may cause parents to struggle with treatment decisions and experience negative emotions of anxiety, pain, and contradiction (Thys et al., 2015). Previous studies have shown that the level of health literacy of parents is an important factor affecting their treatment decisions, as well as their expectations for disease treatment and quality of care (Townsend et al., 2018). In terms of information support, the transplantation team needs to accurately evaluate parents’ health literacy; provide them with information about treatment plans, procedures, risks, complications, and prognosis; and provide them with treatment plans and suggestions accurately (Luo & Zou, 2019). Decision aids presented in the form of manuals, websites, apps, and decision coaches have been proven to provide patients and their families with information on the pros and cons of different treatment options, help clarify personal preferences and values, and promote their participation in clinical decision-making, which can be further explored in the future (Goldschmidt et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2016). At the family level, transplant families should be encouraged to actively participate in treatment decision-making and provided with material and emotional support to reduce the psychological burden of parents, especially the donors (Dong et al., 2022; Kregel et al., 2023).

In the postoperative stage, the jaundice of the child obviously subsides, the condition improves, and the positive emotions of the parents gradually manifest. This study revealed that parents experienced significant physical and mental pressure during postoperative care, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Annunziato et al., 2020). Those who act as both donors and primary caregivers often beard a greater level of psychological pressure due to role adaptation conflict. Research conducted by Dong et al. (2022) has shown that these patients not only suffer from physical symptoms such as lack of sleep, fatigue, and pain but they also have a heavy psychological burden. Schaefer et al. (2018) noted that the key to realizing post-traumatic growth depends on individuals’ inner psychological resources. A positive coping style pointing to the future is an extremely valuable psychological resource for patients when dealing with trauma, which is conducive to their reconstruction of social functions and reintegration into society (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Mental health professionals need fully evaluate the coping styles of caregivers and encourage them to establish effective internal coping strategies through positive self-psychological suggestions, cognitive regulation, and attention diversion. Meanwhile, enhanced support systems are a key factor in promoting positive coping among caregivers, and a support network that integrates family, hospitals, and society may alleviate the care burden of caregivers (Kregel et al., 2023).

Previous studies have shown that moderate levels of post-traumatic growth were found even 4 years after trauma events (Schaefer et al., 2018). Therefore, we should also attach importance to the post-traumatic growth stage, as it is the most common positive psychological change for people who have experienced trauma (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Dong et al. (2022) demonstrated that caregivers of children undergoing liver transplantation exhibited certain positive psychological changes, such as giving back to society, regaining hope in life, actively learning and acquiring disease care knowledge, and actively facing life. In this study, parents realized the preciousness of life and were very lucky to donate their liver to the child, giving them a second life. They gained positive growth experiences, mainly manifested in three dimensions: a shift in life attitude, enhanced psychological resilience, gratitude and giving back to society. The gratitude extension-construction theory suggests that gratitude, as a positive psychological resource, can promote post-traumatic growth and construct psychological and social resources that individuals can utilize. The stronger an individual's gratitude is, the easier it is to promote post-traumatic growth (Krosch & Shakespeare-Finch, 2016). This study revealed that parents’ gratitude to their family, peers, doctors and society was crucial for achieving post-traumatic growth. Classic gratitude interventions, including gratitude diaries, gratitude visits, and gratitude education (Fredrickson, 2004), could be useful for activating gratitude and facilitating growth.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we recruited only parents whose children received a living-related liver transplant, and we could not determine whether the mental health of parents with cadaveric liver transplants were different. In addition, to avoid heterogeneity, we recruited only parents of children diagnosed with biliary atresia, so we cannot explore other children with end-stage liver disease who require liver transplantation, such as those with Alagille syndrome or cholestatic cirrhosis. Second, the recruitment of recipients took place at a single site, which may limit the external validity of the findings. Third, the study predominantly included female participants, there are fathers’s perspectives that were not captured and experiences that may not be known. Finaly, the experiences of post-traumatic growth were divided roughly and preliminarily according to the 16 participating parents. The psychological status of the participants in our study may have differed to a certain degree due to differences in the severity of the child's condition, the time post-transplant, and family conditions (see Table 3). A longitudinal qualitative research is required to judge whether the psychological experiences are representative of all parents’ post-traumatic growth experiences at different stages of their children’s transplantation process.

6. Conclusion

This qualitative study revealed dynamic changes in post-traumatic growth among parents during 5 stages from the child’s diagnosis of biliary atresia to the stable period after living-related liver transplantation. It is necessary for more healthcare providers to be aware of the significant psychological impacts and changes that trauma causes for parents, and formulate targeted intervention strategies at different stages to improve their psychological well-being, especially those who serve as both donors and primary caregivers. During the early treatment stage, cognitive interventions such as narrative writing and mindfulness therapy could be carried out by mental health professionals to encourage parents to express their negative emotions, and guided them to develop positive cognition toward traumatic events by citing successful cases and shared peer experiences. Moreover, we highlighted the importance of coping strategies and increasing personal growth. In the postoperative stage, mental health professionals need fully evaluate the coping styles of parents, encourage them to establish effective coping strategies through positive self-psychological suggestions, cognitive regulation, and attention diversion. Classic gratitude interventions could be given during the post-traumatic growth stage to improve parents’s post-traumatic growth level. In the future, a longitudinal qualitative research could be adopted to investigate the post-traumatic growth experience of parents at different stages of the transplantation process of their children, providing reference for mental health professionals to develop phased psychological intervention programmes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the active participation and contribution of the 16 parents in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, HFW. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study (approval number: IIT20240223B-R2) was obtained from the Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) where the study was undertaken.

Credit author statement

ZhiRu Li: Conceived the study, analysed the data, collected the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft. FangYan Lu: Conceived the study, analysed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper and approved the final draft. Li Dong: Conceived the study, analysed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper and approved the final draft. Li Zheng: Conceived the study, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper and approved the final draft. JingYun Wu: Prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft. SiYuan Wu: Prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft. Yan Wang: Authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft. HuaFen Wang: Conceived the study, audited the initial analyses and interpretation, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

References

- Abdollahpour, I., Nedjat, S., & Salimi, Y. (2018). Positive aspects of caregiving and caregiver burden: A study of caregivers of patients with dementia. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 31(1), 34–38. 10.1177/0891988717743590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon, R. (2019). Social support and post-crisis growth among mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder and mothers of children with Down syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 90, 22–30. 10.1016/j.ridd.2019.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziato, R. A., Stuber, M. L., Supelana, C. J., Dunphy, C., Anand, R., Erinjeri, J., Alonso, E. M., Mazariegos, G. V., Venick, R. S., Bucuvalas, J., & Shemesh, E. (2020). The impact of caregiver post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms on pediatric transplant outcomes. Pediatric Transplantation, 24(1), e13642. 10.1111/petr.13642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batsis, I., Bucuvalas, J., Eisenberg, E., Lau, J., Squires, J. E., Feng, S., & Perito, E. R. (2023). Immunosuppression after pediatric liver transplant: The parents’ perspective. Clinical Transplantation, 37(4), e14931. 10.1111/ctr.14931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, M. R., Stormon, M., Hardikar, W., Ee, L. C., Krishnan, U., Carmody, D., Jermyn, V., Lee, M. M., O'Loughlin, E. V., Sawyer, J., Beyerle, K., Lemberg, D. A., Day, A. S., Paul, C., & Hazell, P. (2015). Family adjustment and parenting stress when an infant has serious liver disease: The Australian experience. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 60(6), 717–722. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byra, S., Zyta, A., & Cwirynkało, K. (2017). Posttraumatic growth in mothers of children with disabilities. Hrvatska Revija za Rehabilitacijska Istraˇzivanja, 53(Supplement), 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, L., Kovar, E. M., Aqul, A., McLoughlin, L., Mittal, N. K., Rodriguez-Baez, N., Shneider, B. L., Zwiener, R. J., Chambers, T. M., Langlois, P. H., Canfield, M. A., Agopian, A. J., Lupo, P. J., & Harpavat, S. (2022). The epidemiology of biliary atresia: Exploring the role of developmental factors on birth prevalence. The Journal of Pediatrics, 246, 89–94.e2. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, P. H. Y., Zheng, S., & Tam, P. K. H. (2020). Biliary atresia: East versus west. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery, 29(4), 150950. 10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2020.150950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaizzi, P. F. (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In Valle R. S. & King M. (Eds.), Existential-phenomenological alternatives for psychology (pp. 48–71). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J. M. (1998). The Corbin and Strauss chronic illness trajectory model: An update. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 12(1), 33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1991). A nursing model for chronic illness management based upon the trajectory framework. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 5(3), 155–174. 10.1891/0889-7182.5.3.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L., Lu, F., Lu, F., & Song, Y. (2022). Caring experience of donors and caregivers of pediatric living related liver transplantation: A qualitative study. Chinese Journal of Nursing, 57(12), 1494–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, D. (2014). An enduring somatic threat model of posttraumatic stress disorder due to acute life-threatening medical events. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(3), 118–134. 10.1111/spc3.12089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekong, U. D., Gupta, N. A., Urban, R., & Andrews, W. S. (2019). 20- to 25-year patient and graft survival following a single pediatric liver transplant-analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing database: Where to go from here. Pediatric Transplantation, 23(6), e13523. 10.1111/petr.13523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhadi, A., Bahreini, M., Moradi, A., Mirzaei, K., & Nemati, R. (2022). The predictive role of coping styles and sense of coherence in the post-traumatic growth of mothers with disabled children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12888-022-04357-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawaz, R., Baumann, U., Ekong, U., Fischler, B., Hadzic, N., Mack, C. L., McLin, V. A., Molleston, J. P., Neimark, E., Ng, V. L., & Karpen, S. J. (2017). Guideline for the Evaluation of Cholestatic Jaundice in Infants: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology. Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 64(1), 154–168. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1377. 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, I., Migal, K., Rückert, N., van Dick, R., Pfister, E. D., Becker, T., Richter, N., Lehner, F., & Baumann, U. (2015). Personal decision-making processes for living related liver transplantation in children. Liver Transplantation: Official Publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society, 21(2), 195–203. 10.1002/lt.24064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasosah, M. (2021). Knowledge and practice of pediatric providers regarding neonatal cholestasis in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Medicine & Medical Sciences, 9(3), 248–253. 10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_462_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hullmann, S. E., Fedele, D. A., Molzon, E. S., Mayes, S., & Mullins, L. L. (2014). Posttraumatic growth and hope in parents of children with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 32(6), 696–707. 10.1080/07347332.2014.955241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehar, M., Parekh, R. S., Stunguris, J., De Angelis, M., Van Roestel, K., Ghanekar, A., Cattral, M., Fecteau, A., Ling, S., Kamath, B. M., Jones, N., Avitzur, Y., Grant, D., & Ng, V. L. (2019). Superior outcomes and reduced wait times in pediatric recipients of living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation Direct, 5(3), e430. 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kregel, M., Evans, N., Wooten, B., Campbell, C., de Ribaupierre, S., & Andrade, A. (2023). A shared decision-making process utilizing a decision coach in pediatric epilepsy surgery. Pediatric Neurology, 143, 13–18. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2023.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krosch, D., & Shakespeare-Finch, J. (2016). Grief, traumatic stress, and posttraumatic growth in women who have experienced pregnancy loss. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(4), 425–433. 10.1037/tra0000183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendahl, U., Lui, V. C. H., Chung, P. H. Y., & Tam, P. K. H. (2021). Biliary Atresia - emerging diagnostic and therapy opportunities. EBioMedicine, 74, 103689. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Lu, X., & Fu, Z. (2022). The current status and impact factors of post-traumatic growth among parents of pediatric renal transplantation recipients. Practice Journal of Transplantation, 10(01|1), 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X., & Zou, P. (2019). Medical decision-making difficulties among parents of children with biliary atresia. Chinese Journal of Nursing, 54(11), 1630–1633. 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2019.11.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nizery, L., Chardot, C., Sissaoui, S., Capito, C., Henrion-Caude, A., Debray, D., & Girard, M. (2016). Biliary atresia: Clinical advances and perspectives. Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology, 40(3), 281–287. 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paley, J. (1997). Husserl, phenomenology and nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(1), 187–193. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997026187.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, J., Kassam-Adams, N., Alderfer, M. A., Christofferson, J., & Kazak, A. E. (2016). Systematic review: A reevaluation and update of the integrative (trajectory) model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41(1), 86–97. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal, N., & Yazigi, N. (2017). Pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 64(3), 677–684. 10.1016/j.pcl.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Davalos, M. I., Lopez-Verdugo, F., Kasahara, M., Muiesan, P., Reddy, M. S., Flores-Huidobro, M. A., Xia, Q., Hong, J. C., Niemann, C. U., Seda-Neto, J., Miloh, T. A., Yi, N. J., Mazariegos, G. V., Ng, V. L., Esquivel, C. O., Lerut, J., & Rela, M. (2023). International liver transplantation Society Global Census: First look at pediatric liver transplantation activity around the world. Transplantation, 107(10), 2087–2097. 10.1097/TP.0000000000004644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, W., Galvan, N., Dike, P., Koci, M., Faraone, M., Fuller, K., Koomaraie, S., Cerminara, D., Fishman, D. S., Deray, K. V., Munoz, F., Schackman, J., Leung, D., Akcan-Arikan, A., Virk, M., Lam, F. W., Chau, A., Desai, M. S., Hernandez, J. A., & Goss, J. A. (2023). The multidisciplinary pediatric liver transplant. Current Problems in Surgery, 60(11), 101377. 10.1016/j.cpsurg.2023.101377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, Y., Virit, O., & Demir, B. (2016). Depression and anxiety in parents of children who are candidates for liver transplantation. Arquivos de gastroenterologia, 53(1), 25–30. 10.1590/S0004-28032016000100006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Valle, A., Kassira, N., Varela, V. C., Radu, S. C., Paidas, C., & Kirby, R. S. (2017). Biliary atresia: Epidemiology, genetics, clinical update, and public health perspective. Advances in Pediatrics, 64(1), 285–305. 10.1016/j.yapd.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, L. M., Howell, K. H., Schwartz, L. E., Bottomley, J. S., & Crossnine, C. B. (2018). A concurrent examination of protective factors associated with resilience and posttraumatic growth following childhood victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 85, 17–27. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. K., & Miloh, T. (2022). Pediatric liver transplantation. Clinics in Liver Disease, 26(3), 521–535. 10.1016/j.cld.2022.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer, F., Friedrich, M., Kuba, K., Ernst, J., Glaesmer, H., Platzbecker, U., Vucinic, V., Heyne, S., Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A., & Esser, P. (2023). New progress in an old debate? Applying the DSM-5 criteria to assess traumatic events and stressor-related disorders in cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology, 32(10), 1616–1624. 10.1002/pon.6213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires, A., & Dorsen, C. (2018). Qualitative research in nursing and health professions regulation. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 9(3), 15–26. 10.1016/S2155-8256(18)30150-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram, S. S., Mack, C. L., Feldman, A. G., & Sokol, R. J. (2017). Biliary atresia: Indications and timing of liver transplantation and optimization of pretransplant care. Liver Transplantation: Official Publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society, 23(1), 96–109. 10.1002/lt.24640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]