Abstract

Objective

To test the effectiveness of, and explore interactions between, three interventions to prevent falls among older people.

Design

A randomised controlled trial with a full factorial design.

Setting

Urban community in Melbourne, Australia.

Participants

1090 aged 70 years and over and living at home. Most were Australian born and rated their health as good to excellent; just over half lived alone.

Interventions

Three interventions (group based exercise, home hazard management, and vision improvement) delivered to eight groups defined by the presence or absence of each intervention.

Main outcome measure

Time to first fall ascertained by an 18 month falls calendar and analysed with survival analysis techniques. Changes to targeted risk factors were assessed by using measures of quadriceps strength, balance, vision, and number of hazards in the home.

Results

The rate ratio for exercise was 0.82 (95% confidence interval 0.70 to 0.97, P=0.02), and a significant effect (P<0.05) was observed for the combinations of interventions that involved exercise. Balance measures improved significantly among the exercise group. Neither home hazard management nor treatment of poor vision showed a significant effect. The strongest effect was observed for all three interventions combined (rate ratio 0.67 (0.51 to 0.88, P=0.004)), producing an estimated 14.0% reduction in the annual fall rate. The number of people needed to be treated to prevent one fall a year ranged from 32 for home hazard management to 7 for all three interventions combined.

Conclusions

Group based exercise was the most potent single intervention tested, and the reduction in falls among this group seems to have been associated with improved balance. Falls were further reduced by the addition of home hazard management or reduced vision management, or both of these. Cost effectiveness is yet to be examined. These findings are most applicable to Australian born adults aged 70-84 years living at home who rate their health as good.

What is already known on this topic

Multiple interventions are known to prevent falls among older people, but the relative importance of the different strategies is unknown

What this study adds

A weekly exercise programme focusing on balance, plus exercises at home, can help to prevent falls among Australians aged 70 years and over living at home and in good health

Home hazard management and vision screening and referral are not markedly effective in reducing falls when used alone but add value when combined with the exercise programme

Introduction

The prevention of falls among older people living in their own homes is an established priority in many countries. The focus of falls prevention research has most recently been on testing interventions. Randomised trials of single interventions among older people living at home have shown that exercise,1 medication reduction,2 support services arranged by trained volunteers,1 and home modifications arranged by occupational therapists3 are all effective interventions. Trials of multiple interventions among older people living at home have also shown reductions in the risk of falling.1

None of the designs of these trials, except one,2 permitted examination of the effects of each component separately or of any interactive effect between components. The main aim of this randomised controlled trial was to test the effectiveness of, and to explore any interactions between, three interventions to reduce falls among older people.

Methods

Setting and subjects

The study was conducted in the City of Whitehorse, a mainly middle class area of Melbourne, the second largest city in Australia. Potential participants were people aged 70 years and over living in their own home.

Design

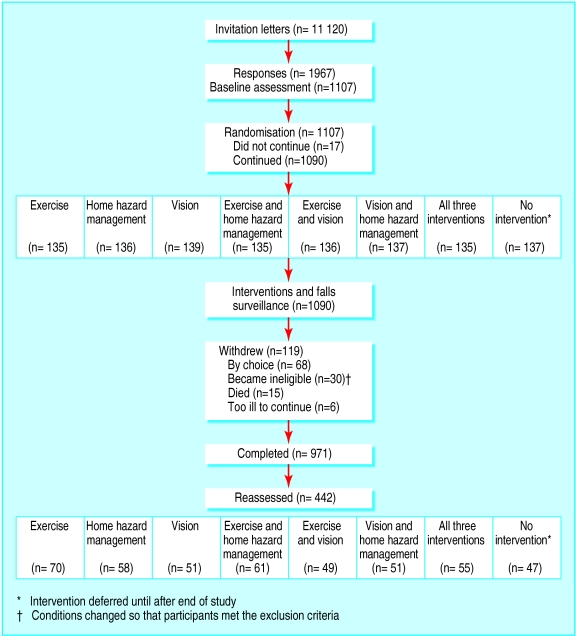

The targeted risk factors were strength, balance, poor vision, and presence of home hazards. The selection of the first three risk factors was justified by strong research evidence and their being amenable to intervention through local government. The widespread existence of home hazard modification programmes (albeit with no strong evidence base) justified inclusion of the fourth. A full factorial design was used, with eight distinct groups defined according to the presence or absence of each of the three interventions (fig 1). Seven groups received at least one intervention; the eighth received no intervention until after the study had ended. Participants were randomly assigned by an “adaptive biased coin” technique, rather than simple equiprobable randomisation, to ensure balance of group numbers.4 Approval was obtained from the Monash University's standing committee on ethics in research involving humans.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing stages in study protocol and numbers of participants

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants had to be living in their own home or apartment or leasing similar accommodation and allowed to make modifications. Potential participants were excluded if they did not expect to remain in the area for two years (except for short absences); had participated in regular to moderate physical activity with a balance improvement component in the previous two months; could not walk 10-20 metres without rest, help, or having angina; had severe respiratory or cardiac disease; had a psychiatric illness prohibiting participation; had dysphasia; had had recent major home modifications; had an education and language adjusted score >4 on the short portable mental status questionnaire5; or did not have the approval of their general practitioner.

Sample size

To detect a 25% relative reduction (or more) in the annual fall rate, with 5% significance level and power of 80%, 914 individuals were needed.6 A 25% reduction was considered achievable on the basis of other multifactorial studies,7 and would be of public health significance. The calculation assumed a non-intervention annual rate of 35 falls per 100 people and a “main effects” two-group comparison for each intervention. Allowing for a 20% dropout rate, 1143 subjects were needed.

Recruitment

We sent invitation letters and made follow up telephone calls to 11 120 people aged 70 years and over and registered on the Australian electoral roll for the area (96% of eligible voters in this age group are registered8). All Australian citizens aged over 18 years and “of sound mind” are required by law to be registered on the electoral roll. The electoral roll therefore includes almost all older people, some of whom would not be eligible according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria. We could not estimate the eligible number owing to the nature of these criteria. Local publicity and recruitment by general practitioners supported the main strategy.

When compared with data from the national census and health survey for Australians aged over 70 living at home, the study group differed as follows: a higher proportion (46.0% v 42.8%) were aged 70-74 years and a lower proportion (7.3% v 9.8%) aged over 85 years old; a higher proportion (77.3% v 66.7%) were Australian born; a higher proportion (53.8% v 32.7%) were living alone; and a lower proportion (46.8% v 52.3%) were married. Study participants rated their health status considerably higher (very good to excellent, 62.6% v 30.7%), and a higher proportion (13.8% v 9.0%) reported taking antidepressant and hypnotic medication.

Assessment

Participants received a home visit by a trained assessor, who was initially blinded to group assignment. After informed consent was obtained, a baseline questionnaire was completed covering demographic characteristics; ability to perform basic activities and instrumental (more complex) activities of daily living9; use of support services; social outings and interests; the modified falls efficacy scale10; self rated health; and falls and medical history. Current prescription and over the counter drugs were recorded from containers at the participants' homes.

The targeted risk factors were assessed by using the methods outlined in table 1. Participants were then assigned (by computer generated randomisation) to an intervention group by an independent third party via telephone.

Table 1.

Risk factor assessment

| Risk factor and test used

|

Description

|

Measure

|

|---|---|---|

| Quadriceps strength: | ||

| Spring gauge11 | Leg extension while seated, with hip and knee angles at 90° with gauge attached by strap around leg 10 cm above ankle | Weight (kg)—best of three attempts on each leg |

| Balance: | ||

| Postural sway11 | Two conditions, standing in bare feet: (a) on floor in bare feet and (b) on polyether-urethrane foam pad (8.5 x 70 x 62 cm, 23 kg/m3), using Lord swaymeter to record body displacement at waist level | Log of product of maximal anterior-posterior and lateral sway in each period of 30 s |

| Maximal balance range11 | Leaning forwards and backwards without bending at hips, as far as possible, using Lord swaymeter to record anterior-posterior distance moved at waist level | Distance (cm)—best of three attempts |

| Coordinated stability11 | With Lord swaymeter attached at waist level and in participant's view, adjust balance by moving upper body (but not feet) to make tracing within convoluted track printed on paper on adjustable height table | Sum of number of times pen tracing failed to stay within track, plus 5 points for each corner cut |

| Timed “up and go”12 | Stand from chair with no arms, walk three metres, then walk back and sit down | Time (s) |

| Vision: | ||

| Visual acuity13 | Dual visual acuity chart (Australian Vision Charts14); uniocular measurement with distance glasses, seated in best lit room, 2 m from chart; reading low contrast letters then high contrast letters | LogMAR calculated from smallest visual angle correctly perceived (line or part line of smallest letters correctly read) |

| Stereopsis:15 | ||

| Random dot stereo butterfly test | Identification of butterfly configuration hidden in random dot pattern | Able/not able to identify |

| Crossed disparity circles | Identification of decreasingly disparate circles | No of last correctly identified set of circles |

| Field of view1617 | OKP glaucoma screening test: series of numbers in spiral configuration with black stimulus spot in middle; uniocular measurement requiring reading of numbers in consecutive order, and identification of any numbers viewed where black spot disappears | Sum of the number of points where black spot disappears; the result is abnormal if any number(s) make the spot disappear |

| Home hazards: | ||

| Home hazard assessment tool | Walk-through checklist for rooms used in a normal week; focus on steps and stairs, floor surfaces, lighting, bathroom fittings, furniture | Number of hazards |

After 18 months, the risk factor assessments were repeated in a proportion of participants (n=442) randomly selected by an assessor blinded to the intervention group (we used only a proportion of the participants because resources to reassess the whole study group were not available and this assessment was of secondary importance to the study's main goal). Strength and balance were also measured at the final exercise class of the first 177 participants to complete the 15 week programme, 79 of whom were among the 442 subsequently selected for final reassessment.

Interventions

We sent all participants a letter outlining their assigned interventions, advising of necessary actions.

Strength and balance—

Participants attended a weekly exercise class of one hour for 15 weeks, supplemented by daily home exercises. The exercises were designed by a physiotherapist to improve flexibility, leg strength, and balance, and 30-35% of the total content was devoted to balance improvement. Exercises could be replaced by a less demanding routine, depending on the participant's capability. Transport was provided where necessary.

Home hazards—

Home hazards were removed or modified either by the participants themselves or via the City of Whitehorse's home maintenance programme. Home maintenance staff visited the home, providing a quotation for the work, including free labour and materials up to the value of $A100 (£37; $54; €60).

Vision—

If a participant's vision tested below predetermined criteria and if he or she was not already receiving treatment for the problem identified, the participant was referred to his or her usual eye care provider, general practitioner, or local optometrist, to whom the vision assessment results were given. Participants not receiving the vision intervention were provided with the Australian Optometrist Association's brochure on eye care for those aged over 40.

Outcome measures

Participants reported falls using a monthly postcard calendar system to record daily falls outcome. Participants not returning their calendar within five working days of the end of each month, and those recording a fall, were followed up by telephone by a research assistant blinded to group assignment.

Analyses

We calculated changes in levels of risk factor by comparing measures at baseline with those at the end of the study for the 442 randomly selected participants. We calculated mean scores for each of the strength and balance measures, number of hazards in the home, and vision measures. Analysis followed the main effects model such that those who were assigned a particular intervention were compared with those who were not—for example, exercise versus no exercise.

We used three way and two way mixed factorial analysis of variance models to determine changes in quadriceps strength and balance measures.18 We used Fisher's test of exact probability to determine differences in the stereopsis measure between the groups that received vision intervention and those that did not.18 Paired samples t tests were used to assess changes in the remaining measures.18

We analysed the time from randomisation to a participant's first fall using Cox's proportional hazards model. Within the factorial design, alternative models were considered and goodness of fit checked using the Grambsch and Therneau test.19 Effects on the annual fall rate were estimated within the Cox model, confidence intervals being determined using the bias corrected and accelerated bootstrap, with 1000 bootstrap replications for each confidence interval. Analyses were done in EGRET and S-PLUS.

All analyses were performed on an intention to treat basis.

Results

A total of 1107 participants received a baseline assessment and group assignment (fig 1). Demographic characteristics and baseline risk factor measures in the eight study groups were similar (tables 2 and 3). The distribution of group assignment among the 442 participants who were randomly selected for reassessment was representative of the combined study group (fig 1), and demographic characteristics and baseline risk factor measures were similar to those of the combined study group (tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants at baseline

| Characteristic

|

All participants (n=1090)

|

Range across intervention groups (n=1090)*

|

Reassessed participants (n=442)†

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 76.1 (5.0) | 75.4-76.5 (4.7-5.5) | 75.9 (4.9) |

| No (%) of women | 652 (59.8) | 77-93 (55.4-68.4) | 261 (59.0) |

| No (%) of participants living alone | 586 (53.8) | 68-83 (50.0-61.0) | 230 (52.0) |

| No (%) of participants who had a fall in past month | 69 (6.3) | 5-11 (3.7-8.1) | 31 (7.0) |

| Mean (SD) score for activities of daily living‡ | 5.3 (1.1) | 5.2-5.4 (0.92-1.2) | 5.3 (1.1) |

| Mean (SD) No of medications | 3.4 (2.6) | 3.1-3.6 (2.4-2.9) | 3.3 (2.6) |

SD=standard deviation.

Highest and lowest recorded among the eight groups. Measures for the remaining groups fall within the range.

Participants randomly selected for reassessment at end of follow up.

Score for instrumental activities of daily living, plus bathing.

Table 3.

Targeted risk factor measures at baseline. Values are means (standard deviation)

| Measure

|

All participants (n=1090)

|

Range across intervention groups (n=1090)*

|

Reassessed participants (n=442)†

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadriceps strength in stronger leg (kg) | 22.6 (10.5) | 21.3-24.0 (9.6-11.8) | 23.2 (10.7) |

| Postural sway on foam pad (log) | 2.8 (0.35) | 2.7-2.8 (0.32-0.40) | 2.7 (0.37) |

| Maximal balance range (cm) | 13.3 (4.5) | 13.0-13.7 (4.2-5.0) | 13.5 (4.7) |

| Coordinated stability (sum of errors) | 12.4 (8.4) | 11.4-13.0 (7.6-9.2) | 11.6 (8.0) |

| Timed “up and go”(s) | 11.7 (5.3) | 10.9-12.3 (3.6-6.2) | 11.6 (5.6) |

| High contrast acuity in best eye (logMAR) | 0.08 (0.19) | 0.05-0.11 (0.18-0.21) | 0.06 (0.19) |

| Low contrast acuity in best eye (logMAR) | 0.38 (0.19) | 0.34-0.42 (0.17-0.20) | 0.38 (0.19) |

| Dot pattern (No of patterns identified) | 5.8 (3.2) | 5.5-6.1 (3.1-3.4) | 6.0 (3.1) |

| Field of view in best eye (No of correct identifications) | 25.2 (3.0) | 24.8-25.5 (1.9-4.5) | 25.4 (2.7) |

| Home Hazards (No identified) | 9.3 (4.8) | 8.3-10.1 (4.3-5.4) | 9.6 (4.7) |

Highest and lowest recorded among the eight groups. Measures for the remaining groups fall within the range.

Participants randomly selected for reassessment at end of follow up.

Intervention compliance

Of the 541 participants receiving the exercise intervention, 401 started a class. The mean number of sessions attended was 10 (SD 3.8), and 328 participants attended more than 50% of their sessions. The mean number of additional home exercise sessions was nine a month.

Of the 543 participants receiving the home hazard management intervention, 478 participants were advised to have modifications in their homes; 363 of these participants received help to do these modifications, which included hand rails fitted (275 participants), modifications to floor coverings (72), contrast edging fitted to steps (72), and maintenance to steps or ramps (66).

Of the 547 participants receiving the vision intervention, 287 were recommended for referral, of whom 186 had either recently visited or were about to visit their eye care practitioner. Of the remaining 101 participants, 97 took up the referral, resulting in 26 having some form of treatment—new or modified prescription glasses (20) or surgery (6).

Risk factors for falls

The measures of strength and balance undertaken at the final exercise class of the first 177 participants showed significant improvements in mean number of errors made during coordinated stability testing (12.2 v 9.7, t=4.45(df=164), P<0.001) and in maximal balance range (13.3 cm v 15.1 cm, t=5.26 (df=164), P<0.001). Quadriceps strength improved in weaker legs (18.7 v 23.6, t=8.61 (df=161), P<0.001) and stronger legs (21.9 v 24.6, t=5.01 (df=161), P<0.001). The differential improvement between weaker and stronger legs was significant (F=36.25 (df=1, 161), P<0.001).

After 18 months, maximal balance range showed little change in the participants receiving the exercise intervention (decrease of 0.64 cm from mean of 13.7 cm) but decreased over time among the control group (decrease of 1.8 cm from mean of 13.6 cm) (F=6.78 (df=1, 391), P=0.01). This suggests that the exercise intervention slowed the rate of age related deterioration. There were no other significant improvements in the strength and balance measures.

The mean average number of hazards in the participants receiving home hazards intervention decreased from 10.2 to 7.4, compared with a decrease from 9.1 to 7.9 in the control group (F=42.87 (df=1, 440), P<0.001).

Visual acuity (high contrast) improved marginally among the non-intervention group (difference in mean value of 0.046) but remained largely unchanged in the intervention group (F=4.69, (df=1, 406), P=0.03). No other differences were seen in the vision measures.

Falls outcome

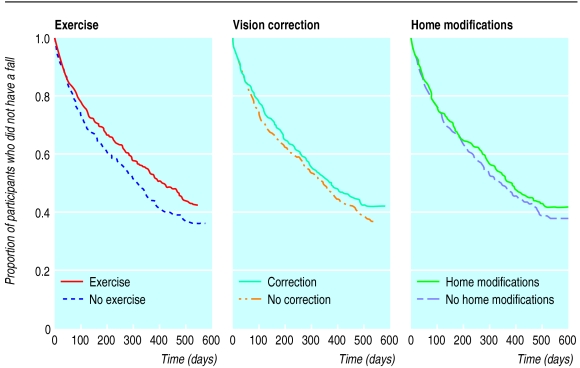

Falls outcome analysis was based on Cox's proportional hazards model, with the three interventions fitted as binary factors. After fitting a main effects model, the higher order interactions between the three interventions were not significant (three way interaction: P=0.9; two way interactions, combined test: P=0.8), so only results based on a main effects model are reported. The Grambsch and Therneau goodness of fit test for the main effects model was not significant (P>0.9). Therefore we based our inferences on this model, in which the effects of the interventions are additive on the log hazard scale. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves for the intervention and non-intervention groups for the three main effects separately. Owing to the factorial design, all subjects contributed to each of the three plots in figure 2. The estimates of the rate ratios, annual fall effects, and number needed to treat to prevent one fall for the single and combined interventions are shown in table 4. For example, the use of exercise and vision correction is estimated to reduce the fall rate by a factor of 0.73 (95% confidence interval 0.58 to 0.91), and the reduction in falls during one year is estimated at 11.1% (2.2% to 18.5%). Nine people would need to be treated with the exercise and vision intervention to prevent one fall a year.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots showing the probability of remaining fall-free, for each of the three interventions separately. All participants are represented in each of the three graphs

Table 4.

Effect on falls outcome, single and combined interventions

| Intervention

|

No (%) having at least one fall

|

Rate ratio

|

% estimated reduction in annual fall rate (95% CI)

|

No needed to treat to prevent 1 fall

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI)

|

P value

|

||||

| No intervention* | 87/137 (63.5) | Reference (1.00) | |||

| Exercise | 76/135 (56.3) | 0.82 (0.70 to 0.97) | 0.02 | 6.9 (1.1 to 12.8) | 14 |

| Vision | 84/139 (60.4) | 0.89 (0.75 to 1.04) | 0.13 | 4.4 (−1.5 to 10.2) | 23 |

| Home hazard management | 78/136 (57.4) | 0.92 (0.78 to 1.08) | 0.29 | 3.1 (−2.0 to 9.7) | 32 |

| Exercise plus vision | 66/136 (48.5) | 0.73 (0.58 to 0.91) | 0.01 | 11.1 (2.2 to 18.5) | 9 |

| Exercise plus home hazard management | 72/135 (53.3) | 0.76 (0.60 to 0.95) | 0.02 | 9.9 (2.4 to 17.9) | 10 |

| Vision plus home hazard management | 78/137 (56.9) | 0.81 (0.65 to 1.02) | 0.07 | 7.4 (−0.9 to 15.2) | 14 |

| Exercise plus vision plus home hazard management | 65/135 (48.1) | 0.67 (0.51 to 0.88) | 0.004 | 14.0 (3.7 to 22.6) | 7 |

No intervention until after the study had ended.

These results show a significant benefit for exercise alone, and a significant effect (P<0.05) for all interventions in which exercise was combined with other interventions. The strongest effect was observed for all three interventions together.

Discussion

This trial examined the individual contribution of, and interaction between, three interventions to reduce falls. However, no interactive effect of the interventions on falls outcome was observed; rather, the interventions were additive. A study of withdrawal from psychotropic drug treatment combined with exercise also found no interactive effect.2

Unlike most previous studies of exercise among unselected older people living in their own homes,1 these results show that a supervised exercise programme for this group for one hour a week for 15 weeks, supplemented with home exercise for up to 12 months, can reduce falls. The reduction occurred despite relatively poor compliance with the home exercise sessions, which were intended to be daily, but in fact were performed twice weekly on average. This is the shortest programme of the lowest intensity shown to reduce falls. Other successful trials of exercise alone have ranged from group classes twice a week for 15 weeks (supplemented with daily exercise) to home based sessions three times a week for two years.2,20,21 There was a greater reduction in falls in the programmes with more intense exercise regimes.

The reduction in falls among participants receiving the exercise intervention was associated with improved balance, most prominent on completion of the exercise programme. However, the falls reduction in this group may also have been mediated via social interaction or behavioural change, or both of these, as a result of heightened awareness engendered during the classes.

The limited effect of the other two interventions on falls outcome may be partly related to insufficient intensity of the interventions. The modifications of home hazards may not have been large enough, or may have been of the wrong type, to have affected falls outcome. Certainly, home modifications facilitated by occupational therapists have been shown to reduce the risk of falling among older people with a falls history who live at home.3

The relatively low numbers of participants who received vision improvement treatment, and the marginal improvement in visual acuity among the non-intervention group, may explain the limited effect on falls outcome among this intervention group. The population studied may already have had many visual problems addressed in the free public healthcare system, since 48% of the intervention group did not require referral. Furthermore, study participants may have been alerted to the potential benefits of the interventions. This would be more likely to influence the results for vision and home hazard management than for exercise, which would have been difficult to replicate without detailed instructions.

As the participants were not blinded to group assignment, the possibility of differences in self reporting bias exists. Participants in the intervention groups may have under-reported falls, and those receiving a more intense intervention, such as the group based exercise programme, may have been even more inclined to under-report. The observed changes in some targeted risk factors supports the conclusion, however, that at least some of the falls reduction was mediated by the interventions.

As the participants differed somewhat from the general older population living at home, the findings are most applicable to older adults living at home with similar characteristics—namely, Australian born, aged 70-84, and rating their health as good to excellent. Other complementary trials may be needed to examine the effectiveness of falls interventions among people living at home who are aged over 85, in poorer health, or from non-English speaking backgrounds.

The combined effect of all three interventions produced the largest outcome observed. However, the results for the single and dual intervention groups indicate that the exercise programme made the major contribution. On the basis of this and the results of a t'ai chi trial,1 exercise programmes with a balance improvement component could be considered for wider implementation among unselected older people living at home. Vision correction and home hazard management may be less effective interventions or may be more effective among specifically targeted groups. Cost effectiveness studies of exercise and other successful interventions would provide important information on which to base resource allocation for the prevention of falls among older people living at home.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Sandra Hills, Fiona McRae, and Elizabeth Fowler, City of Whitehorse, for project coordination; Barbara Fox, Kate Edwards-Coghill, Maria McKinnon, Renee Bush, Dianne Clay, and Sue Morton for home visits and assessments; Sue Vincent for developing and supervising the exercise programme and the leaders of the exercise class for implementing it; Margaret Stevens and Nicole Bennet of the Injury Control Council of Western Australia for providing the Falls Project Home Hazard Assessment protocols; City of Whitehorse home maintenance staff for help with home modifications; Jane Matthews of the Statistical Centre and Peter MacCallum of the Cancer Institute, Melbourne, for use of the RANDOM software; and study participants for their contribution.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care), Victorian Department of Human Services (Aged Care), City of Whitehorse, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, Rotary, and the National Safety Council.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Feder G, Cryer C, Donovan S, Carter Y.on behalf of the guidelines' development group. Guidelines for the prevention of falls in people over 65 BMJ 20003211007–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell AJ, Robertson CM, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Buchner DM. Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home based exercise programme to prevent falls: a randomised controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:850–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummings RG, Thomas M, Szonyi G, Salkeld G, O'Neill E, Westbury C, et al. Home visits by an occupational therapist for assessment and modification of environmental hazards: a randomised trial of falls prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1397–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith J, Laidlaw C, Matthews J. RANDOM. Computer program. Melbourne: Statistical Centre, Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfieffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casagrande JT, Pike MC, Smith PG. An improved approximate formula for calculating sample sizes for comparing two binomial distributions. Biometrics. 1978;34:483–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, Claus EB, Garrett P, Gottschalk M, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:821–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallett B. Youth participation in Australia. Stockholm: Institute For Democracy And Electoral Assistance; 1999. . (International forum on youth and democracy.) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawton MP, Moss M, Fulcomer M, Kleban MH. A research and service oriented multilevel assessment instrument. J Gerontol. 1982;37:91–99. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill KD, Schwarz JA, Kalogeropoulos AJ, Gibson SJ. Fear of falling revisited. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1025–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lord SR, Ward JA, Williams P. The effect of exercise on dynamic stability in older women: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:232–236. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Podsialdo D, Richardson S. The timed “up and go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1981;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lord SR, Clark RD, Webster IW. Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity in relation to falls in an elderly population. Age Ageing. 1991;20:175–181. doi: 10.1093/ageing/20.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verbaken J. Dual contrast visual acuity chart, chart 5. Melbourne, Victoria: Australian Vision Charts; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Random dot stereo butterfly test. Chicago: Stereo Optical; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.OKP glaucoma screening test. Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire: Merck Sharp and Dohme Ophthalmic Services; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domato BE, Ahmed J, Allen D, McClure E, Jay JL. The detection of glaucomatous visual field defects by oculokinetic perimetry: which points are best for screening? Eye. 1989;3:727–731. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maxwell SE, Delaney HD. Designing experiments and analysing data. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grambsch P, Therneau T. Proportional hazard tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchner DM, Cress ME, de Lateur BJ, Esselman PC, Margherita AJ, Price R, et al. The effect of strength and endurance training on gait, balance, fall risk, and health services use in community-living older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M218–M225. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.4.m218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell AJ, Robertson CM, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Tilyard MW, Buchner DM. Randomised controlled trial of a general practice programme of home based exercise to prevent falls in elderly women. BMJ. 1997;315:1065–1069. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]