Abstract

Introduction and importance

Sturge Weber Syndrome (SWS) is a congenital neurocutaneous disorder that affects several organs. Abnormal ocular findings are typically on the same side as the SWS. These changes can affect various parts of the eye, including the eyelid, front chamber, cornea, choroid, and retina. To our knowledge, this is first documented case in the peer review literature of foveal Coloboma in SWS. This case report highlights this important finding in special cases of secondary open angle glaucoma related to SWS.

Case presentation

A 5 month old baby girl, known to have SWS. Presented to our ER with high Intraocular pressure (IOP). Upon external examination, the child had port wine stain on the left side of her face. The dilated fundus exam revealed foveal coloboma which is not known as ocular clinical feature in cases of SWS. The fundus exam also showed diffuse choroidal hemangioma nasal to the disc. The case was managed with Micropulse Cyclophotocoagulation. The IOP was stable during 2 years of follow up.

Discussion

Choroidal colobomas can be vision threatening due macular and optic disc involvement. Choroidal colobomas increase the risk of retinal detachment, and subfoveal choroidal neovascularization. They can occur as a part of genetic disorders such as CHARGE syndrome. In our case the foveal location of the coloboma and the anisometropic amblyopia both led to the decrease of vision and amblyopia in that eye.

Conclusions

Reporting a macular coloboma in a patient with SWS. After conducting a literature review on foveal Coloboma utilizing PubMed, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library and ScienceDirect using the key words (Foveal coloboma, Macula coloboma, Sturge Weber Syndrome), we did not find any prior reports of foveal Coloboma in SWS.

Keywords: Case report, Coloboma, Fovea, Sturge Weber Syndrome, Secondary glaucoma

Highlights

-

•

Management of secondary glaucoma in SWS can be challenging.

-

•

Macular coloboma have not been associated with SWS before.

-

•

Macular coloboma can complicate the management in cases of SWS.

-

•

Macular coloboma can lead to retinal detachment and patient poses risks should be followed closely.

1. Introduction

Sturge–Weber syndrome (SWS) is a congenital neurocutaneous disorder that affects several organs. The classic triad includes leptomeningeal hemangioma, facial angiomatosis and ocular hemangiomas. Phacomatoses such as neurofibromatosis, Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel–Lindau syndrome, are rare and sporadic conditions that arise from neural crest anomalies [[1], [2], [3]]. The incidence of SWS is 1:50,000 infants, with no gender predilection [4]. The clinical diagnosis of SWS is based on the presence of at least two of the three classic triads. However, clinical findings of SWS may vary between patients, showing variable neural signs with the absence of or varying degree of ocular involvement [5,6]. Roughly half of individuals with SWS exhibit abnormal ocular findings, typically on the same side as the SWS. These changes can affect various parts of the eye, including the eyelid, front chamber, cornea, choroid, and retina [6]. Glaucoma in SWS is mostly unilateral, and it is associated with the presence of port wine stain in the same side [7]. Choroidal hemangiomas are an important posterior segment clinical feature and can be clinically divided into localized and diffuse forms, but it is the diffuse (DCH) form that typically occurs in SWS patients [5,8]. Choroidal hemangioma is present in 20 % to 70 % of SWS cases, and its presence increases the risk of developing glaucoma [6]. Other ocular features in SWS include retinal degeneration, retinal serous detachment, cystoid macular edema, tortuous retinal vessels, and optic disc coloboma [[6], [7], [8]]. We present a unique finding of macula coloboma in SWS.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Case report

A 5 month old baby girl with SWS, who was the product of a full term pregnancy presented to our emergency room with high intraocular pressure (IOP) of 27 mm Hg in the left eye. She was using combined Dorzolamide/Timolol twice daily in the same eye. On external examination, the child had port wine stain on the left side of her face and the same stain was apparent on the left side of her chest. The child's visual behavior was to fixate and follow the targets presented to her. The child needed examination under anesthesia (EUA) for full ocular assessment.

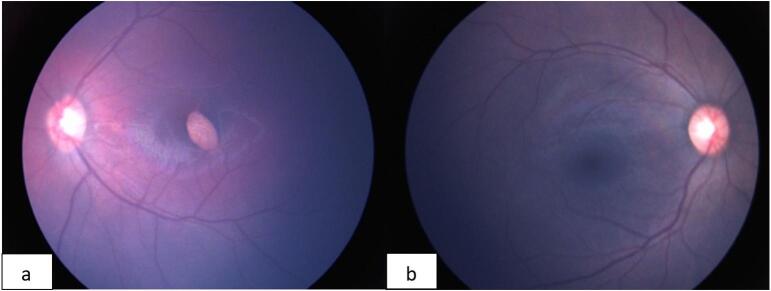

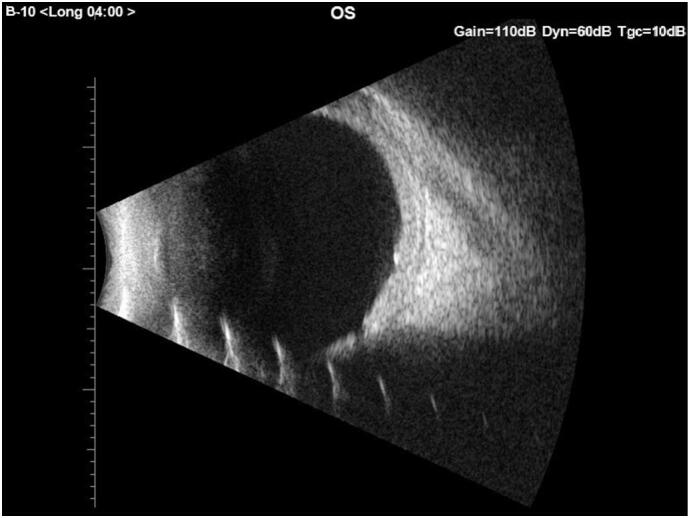

EUA revealed an IOP of 14 mm Hg in the right eye and 20 mm Hg in the left eye. Corneal diameter as 12 mm in the right eye and 13 mm in the left eye. The axial length was 20.13 mm in the right eye and 21.75 mm in the left eye. The ocular examination in the left eye indicated a clear enlarged cornea with a quiet eye (Fig. 1). The anterior chamber was deep and quiet with a clear lens in the left eye. In the left eye, dilated fundus exam showed foveal coloboma which to our knowledge has not been reported before in cases of SWS. The fundus exam also showed diffuse choroidal hemangioma nasal to the disc. Retcam (Natus Medical, Inc., Pleasanton, CA USA) was used to obtain bilateral fundus photos for documentation and follow up (Fig. 2A,B) The discs had 0.5 vertical cup-to-disc ratios (Fig. 2A,B). The patient's cycloplegic refraction was +2.5 D in the right eye and −5.5 D in the left eye. B-scan was performed on the left eye and that confirmed the foveal coloboma (Fig. 3). As an option to reduce her IOP we elected to preform micropulse cyclophotocoagulation (MPCPC) in the left eye. We proceeded with MPCPC only in the inferior hemisphere with power of 2500 mw and duration of 80 s. The superior hemisphere was avoided in case the patient required filtration surgery in the future. To address her amblyopic left eye and fixation preference, patient was given glasses and patching on her latest follow up visit with pediatrics.

Fig. 1.

Clear enlarged cornea with mild injection of the conjunctiva in a patient with Sturge Weber Syndrome (SWS).

Fig. 2.

Wide-field fundus photos of both eyes in a patient with Sturge Weber Syndrome (SWS). Left eye show a foveal coloboma (Fig. 2a). Right eye shows a normal fundus photo (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 3.

B scan ultrasonography of the left eye showing a foveal coloboma and no other significant findings.

The child was followed for almost 2 years with serial of EUAs which indicated a stable disease course and an IOP ranging from 10 to 16 mm Hg on one anti-glaucoma medication in the left eye. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [15].

3. Discussion

Glaucoma and neurologic complications which include seizures and developmental delay, are common in SWS [5]. It is mandatory to closely monitor glaucoma in these patients. In children with SWS, other parameters such as axial length and corneal diameter are important to detect progression. Magnetic resonance imaging might be useful to detect thickening of the eyes as a consequence of DCH. It is fundamental to do a complete ophthalmic examination at each follow-up in SWS patients in order to detect visual function loss, which is frequently related to progression of glaucoma, and also to detect the onset of retinal complications [6]. The three main theories on the pathogenesis of developing glaucoma in SWS includes:

-

1-

Dysgenesis of the anterior chamber angle leading to increase resistance to aqueous humor (AH) outflow [7].

-

2-

Elevated episcleral venous pressure due to arteriovenous shunts into the episcleral hemangioma. This theory is associated with more severe glaucoma [9].

-

3-

Hypersecretion of AH by either the ciliary body or the choroidal hemangioma [10].

The GNAQ gene was identified to be associated with the development of glaucoma in SWS. This gene stimulates the proliferation of cells and inhibits apoptosis [11]. Management of glaucoma in SWS is a wide ranging starting from medical management alone, surgical intervention or combined management. When medical treatment fails to control glaucoma progression, surgical intervention is warranted. Trabeculectomy is used to create a new pathway for drainage, yet it carries high risk of developing choroidal hemorrhage. Almobarak et al. reported the efficacy of deep sclerectomy in 11 patients in SWS-related glaucoma [2]. MPCPC was found to have lower success rates in children with glaucoma related to SWS. Lee et al. reported 4 cases of children with SWS and only 1 was controlled with MPCPC during the 12 month follow up [12]. Over the duration of follow-up in the last 24 months, our patient's IOP was well controlled with a single glaucoma medication after MPCPC was performed when she was 6 months old.

Coloboma of the choroid, retina or optic nerve results from failure of posterior closure of the embryonic fissure [13]. Choroidal colobomas can be vision-threatening due macular and optic disc involvement. Choroidal colobomas increase the risk of retinal detachment (RD), and subfoveal choroidal neovascularization during the lifetime of the individual. Prophylactic laser treatment might be indicated to decrease the chance of developing RD. It can cause chronically poor vision due to uncorrected refractive error, amblyopia, and foveal involvement [14]. They can occur as a part of genetic disorders such as CHARGE syndrome (coloboma, heart defects, choanal atresia, retarded growth and development, genital abnormalities, and ear anomalies) or in isolation as in our case. The association between SWS and macular coloboma has not described in the peer review literature. In our case the foveal location of the coloboma and the anisometropic amblyopia both led to the decrease of vision and amblyopia in that eye.

In conclusion, the ocular clinical features are important to diagnose in patient with SWS. The clinical features vary between patients. To our knowledge this unique finding of macula coloboma has never been reported in an SWS patient.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Basil Alhussain: Writing the manuscript and publication.

Hamad Alsubaie: Supervision and review.

Ohoud Owaidhah: Supervision and review.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents/legal guardian for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval for this study was provided by the Ethical Committee in King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital in 24 Jan 2024. Ethical approval number: RD/26001/IRB/0028-24.

Guarantor

Basil Alhussain.

Funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors have no financial disclosures.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

This case report was not submitted nor presented in any conference.

References

- 1.Comi A.M. Presentation, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment of the neurological features of Sturge-Weber syndrome. Neurologist. 2011;17:179–184. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e318220c5b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almobarak F.A., Alobaidan A.S., Alobrah M.A. Outcomes of deep sclerectomy for glaucoma secondary to Sturge–Weber Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2023;12:516. doi: 10.3390/jcm12020516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdolrahimzadeh S., Scavella V., Felli L., Cruciani F., Contestabile M.T., Recupero S.M. Ophthalmic alterations in the Sturge-Weber Syndrome, Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome, and the Phakomatosis Pigmentovascularis: an independent group of conditions? Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/786519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collettini F., Diederichs G., Gebauer B., Poellinger A. Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2011;47:80. doi: 10.1159/000329631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baselga E. Sturge-Weber syndrome. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2004;23:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantelli F., Bruscolini A., La Cava M., Abdolrahimzadeh S., Lambiase A. Ocular manifestations of Sturge-Weber syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016;10:871–878. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S101963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan T.J., Clarke M.P., Morin J.D. The ocular manifestations of the Sturge-Weber syndrome. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus. 1992;29:349–356. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19921101-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinawat S., Auvichayapat N., Auvichayapat P., Yospaiboon Y., Sinawat S. 12-year retrospective study of Sturge-Weber syndrome and literature review. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2014;97:742–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phelps C.D. The pathogenesis of glaucoma in Sturge Weber syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1978;85:27686. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(78)35667-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharan S., Swamy B., Taranath D.A., Jamieson R., Yu T., Wargon O., Grigg J.R. Port-wine vascular malformations and glaucoma risk in Sturge-Weber syndrome. J. AAPOS. 2009;13:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirley M.D., Tang H., Gallione C.J., Baugher J.D., Frelin L.P., Cohen B., North P.E., Marchuk D.A., Comi A.M., Pevsner J. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;23(368):1971–1979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J.H., Shi Y., Amoozgar B., Aderman C., De Alba Campomanes A., Lin S., Han Y. Outcome of micropulse laser transscleral cyclophotocoagulation on pediatric versus adult Glaucoma patients. J. Glaucoma. 2017;26:936–939. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan T.A., Liaqat T., Shahid M., Janjua T.A., Rauf A. Isolated chorioretinal coloboma: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14 doi: 10.7759/cureus.28048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lingam G., Sen A.C., Lingam V., Bhende M., Padhi T.R., Xinyi S. Ocular coloboma-a comprehensive review for the clinician. Eye (Lond.) 2021;35:2086–2109. doi: 10.1038/s41433-021-01501-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2023;109(5):1136. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]