Abstract

Non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is a markedly heterogeneous disease, with its underlying molecular mechanisms and prognosis prediction presenting ongoing challenges. In this study, we integrated data from multiple public datasets, including TCGA, GSE31210, and GSE13213, encompassing a total of 867 tumor samples. By employing Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis, machine learning techniques, and comprehensive bioinformatics approaches, we conducted an in-depth investigation into the molecular characteristics, prognostic markers, and potential therapeutic targets of LUAD. Our analysis identified 321 genes significantly associated with LUAD, with CENP-A, MCM7, and DLGAP5 emerging as highly connected nodes in network analyses. By performing correlation analysis and Cox regression analysis, we identified 26 prognostic genes and classified LUAD samples into two molecular subtypes with significantly distinct survival outcomes. The Random Survival Forest (RSF) model exhibited robust prognostic predictive capabilities across multiple independent cohorts (AUC > 0.75). Beyond merely predicting patient outcomes, this model also captures key features of the tumor immune microenvironment and potential therapeutic responses. Functional enrichment analysis revealed the complex interplay of cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, immune response, and metabolic reprogramming in the progression of LUAD. Furthermore, we observed a strong correlation between risk scores and the expression of specific cytokines, such as CCL17, CCR2, and CCL20, suggesting novel avenues for developing cytokine network-based therapeutic strategies. This study offers fresh insights into the molecular subtyping, prognostic prediction, and personalized therapeutic decision-making in LUAD, laying a critical foundation for future clinical applications and targeted therapy research.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-85471-8.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma, LUAD; Mendelian randomization; Molecular subtypes; Machine learning prognostic model; Multi-omics integrative analysis

Subject terms: Lung cancer, Genetics

Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading global public health challenges. According to the American Cancer Society’s 2022 statistics, the three most common cancers among men in 2021 were prostate cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer, accounting for 46% of all male cases. The leading causes of cancer-related deaths were lung cancer, prostate cancer, and colorectal cancer, respectively1. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents approximately 85% of all lung cancer cases. Despite advancements in early screening and diagnosis, lung cancer remains a leading cause of cancer mortality, with high incidence and death rates2,3. The survival rate of NSCLC is closely related to the stage of the disease, decreasing as the tumor progresses. Patients diagnosed at stage I or II have a 5-year survival rate of up to 70% following surgical resection; however, approximately 75% of patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 25%4–6. The main challenges in NSCLC treatment include insufficient early screening, a high proportion of late-stage diagnoses, and issues related to drug resistance2,7–10. With a deeper understanding of the disease’s biology, the application of predictive biomarkers, and advancements in therapeutic strategies, significant progress has been made in the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC, particularly in the areas of targeted therapy11 and immunotherapy12,13, offering new treatment options for some patients and greatly improving prognosis14,15. The detection of EGFR, BRAF, and MET mutations, as well as the analysis of ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK rearrangements, have been incorporated into the standard diagnostic criteria for NSCLC, with corresponding kinase inhibitors being routinely used in clinical practice16. Moreover, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently approved several new drugs and treatment regimens, including therapies targeting specific genetic mutations and combination therapies involving chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

Recent studies have identified several novel genes associated with NSCLC, providing new targets for future therapeutic strategies. For instance, the RUNX2 gene plays a critical role in tumor metastasis, angiogenesis, proliferation, and resistance to anticancer drugs, and is associated with cancer stem cell characteristics, making it a potential therapeutic target17. The role of ferroptosis-related genes in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) has also been elucidated, with these genes’ expression closely linked to drug resistance, tumor microenvironment infiltration, and cancer stem cell traits18. Research indicates that tumor cells develop multidrug resistance (MDR) by modulating apoptotic pathways, with the Bcl-2 superfamily proteins, inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAP) family members, and their regulators, such as p53, playing pivotal roles in MDR development19. Moreover, interactions within the tumor microenvironment (TME), particularly the factors secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts, can inhibit cancer cell apoptosis and reduce the efficacy of anticancer drugs. This finding underscores the importance of understanding and modulating the immunosuppressive cells within the TME to overcome treatment resistance19–23.

With the advancements in genomics, increasing evidence suggests that genetics plays a crucial role in the etiology of diseases24. Mendelian randomization (MR) is a statistical method based on genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that utilizes genetic variants closely associated with the exposure of interest, which are not influenced by confounding factors, as instrumental variables (IVs). Summary data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) further integrates the principles of Mendel’s laws and randomized trials to assess the effects of genes on specific traits or diseases25,26. SMR infers the impact of particular genes on traits or diseases by analyzing large-scale individual data and comparing the relationship between genotypes and phenotypes. This approach aids in uncovering gene-trait associations, understanding the role of genetic factors in diseases, and providing critical insights for personalized medicine.

Materials and methods

Data collection and preprocessing

The data for this study were sourced from multiple publicly available databases. RNA sequencing data and corresponding clinical information for the TCGA-LUAD cohort, comprising 524 tumor samples, were obtained from the UCSC-XENA database (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/). Additionally, the GSE31210 dataset (226 tumor samples) and the GSE13213 dataset (117 tumor samples) were downloaded from the GEO database. Data preprocessing and normalization were performed using the “limma”27 and “sva”28 packages in R (version 4.2.2), including the removal of batch effects. The final integrated dataset comprised 15,888 genes and 867 samples, among which 321 genes were identified as LUAD-associated through SMR analysis. Of these, 206 genes showed clear expression in the expression profile.

SMR analysis

We utilized lung adenocarcinoma data from the Finnish R9 database (https://storage.googleapis.com/finngen-public-data-r9/summary_stats/finngen_R9_C3_NSCLC_ADENO_EXALLC.gz) as the study outcome. This dataset includes 1,553 non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) cases and 287,137 controls. The Summary data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR) method was employed to assess the impact of genes on lung adenocarcinoma. During the HEIDI (Heterogeneity in Dependent Instruments) analysis, genes with P(HEIDI) < 0.05 were excluded.

Network analysis, survival analysis, and gene screening

Based on the 321 genes identified through the SMR method, univariate Cox regression analysis (p-value < 0.001) was performed, using the Wald test to assess the association between each gene and survival. Significantly prognostic genes were identified through this process. Correlation coefficients and significance levels for gene pairs were calculated using the corr.test function from the psych R package. Gene pairs with significant correlations (p-value < 0.0001) were selected to construct a co-expression network.The edge weights were determined by the absolute values of correlation coefficients, while edge colors represented the correlation direction (positive correlations in pink, negative correlations in blue). Node attributes included the gene’s risk category (high-risk or protective factor), Cox regression hazard ratio (HR) values, and their significance levels (p-values). Node sizes were scaled according to the significance of p-values, and border colors distinguished risk categories. The network was visualized using a circular layout in the igraph R package(https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=igraph), and the node and edge attribute files were exported as network.node.txt and network.edge.txt, respectively. The final network diagram (network.pdf) illustrated key genes and their interactions.Additionally, 26 significantly different genes (p < 0.05) were identified. Survival analysis using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test was performed to determine genes significantly associated with prognosis.

Tumor subtyping

Unsupervised clustering analysis was performed using the “ConsensusClusterPlus”29 package in R, based on the 26 significantly different genes, to classify the samples into two subtypes. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was then conducted to compare survival differences between the subtypes, and a heatmap was generated to visualize the differential gene expression across the subtypes.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

We employed the Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) method to evaluate pathway activity in LUAD samples. The RNA sequencing expression matrix was normalized after removing duplicate genes. The pathway gene sets were obtained from the MSigDB database (file: h.all.v2023.1.Hs.symbols.gmt), encompassing key tumor-related pathways. GSVA was performed using the gsva function from the GSVA30 R package (version 2.1.2), with parameters min.sz = 10 and max.sz = 500 to filter out overly small or large gene sets.The GSVA scores were integrated with subtype data and analyzed using the limma package to identify differentially active pathways between subtypes. A linear model was applied to compare pathway activity, and pathways with significant differences were identified based on the criteria |logFC| > 0.1 and adj.P.Val < 0.05. The expression patterns of significantly different pathways were visualized using heatmaps (created with the pheatmap tool), providing an intuitive representation of pathway differences between subtypes. The results of this analysis were used to explore the biological differences underlying the molecular subtypes of LUAD.

Differential gene expression and enrichment analysis

The Wilcoxon test was used to compare gene expression differences between the subtypes, identifying significant genes (|LogFC| > 1, FDR < 0.05). The “clusterProfiler”29 package in R was employed to perform GO and KEGG enrichment analyses on the differentially expressed genes, highlighting significant pathways in biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF).

Immune cell and microenvironment analysis

The R package IOBR(https://github.com/IOBR/IOBR) was utilized to assess immune cell infiltration, employing 8 different methods: MCPcounter, EPIC, xCell, CIBERSORT, IPS, quanTIseq, ESTIMATE, and TIMER. The ssGSEA function from the GSVA package was used to calculate immune cell infiltration scores, and differences between the subtypes were compared.

Mutation analysis, chemokine analysis, and immunotherapy prediction

Mutation differences between the two sample subtypes were analyzed using the R package maftools31, with waterfall plots generated to illustrate the mutation spectra of each group. Comparative analysis of the mutated genes in the high- and low-risk groups was performed to identify significantly different mutations. The relationship between model scores and chemokines, as well as their receptors, was evaluated. Correlation analysis was used to compare differences in chemokine expression between the high- and low-risk groups. The TIDE (Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion) database was used to predict TIDE scores and the effectiveness of immunotherapy in LUAD patients. Higher TIDE scores indicate poorer therapeutic outcomes. Differences in immune exclusion scores and TIDE scores between the high- and low-risk groups were also analyzed.

Drug sensitivity prediction

The R package oncoPredict(https://github.com/OncoPredict/OncoPredict) was employed to predict the IC50 values of various anticancer drugs for each sample, and differences between the high- and low-risk groups were compared. A higher IC50 indicates lower sensitivity to the treatment.

Machine learning modeling

Based on the results of the GSVA scores, multiple machine learning methods were employed to construct prognostic models. We integrated 10 classic algorithms: Random Survival Forest (RSF), Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), Survival Support Vector Machine (Survival-SVM), Supervised Principal Components (SuperPC), Ridge Regression, Partial Least Squares Regression for Cox (plsRcox), CoxBoost, Stepwise Cox, and Elastic Net (Enet). The TCGA dataset was used as the training set, while the GSE31210 and GSE13213 datasets were used for validation to assess the prognostic capabilities of the models.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) experiment

Total RNA was extracted from cell samples using an RNA extraction kit (Servicebio, Cat# G3013), and quantified with a Nanodrop 2000. RNA (200 ng/µL) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using SweScript All-in-One RT SuperMix (Cat# G3337) under the following conditions: 25 °C for 5 min, 42 °C for 30 min, and 85 °C for 5 s. qPCR was performed on a Bio-rad CFX Connect system with a reaction volume of 15 µL, including 2× SYBR Green Master Mix (Cat# G3326), primers, cDNA, and nuclease-free water. ACTIN was used as the internal reference, and the target genes were GAPDH, RRM2, ANLN, CDCA5, and OIP5. The primer sequences were: ACTIN (forward: 5’-CACCCAGCACAATGAAGATCAAGAT-3’, reverse: 5’-CCAGTTTTTAAATCCTGAGTCAAGC-3’); GAPDH (forward: 5’-GGAAGCTTGTCATCAATGGAAATC-3’, reverse: 5’-TGATGACCCTTTTGGCTCCC-3’); RRM2 (forward: 5’-ACTTGGTGGAGCGATTTAGCC-3’, reverse: 5’-CCATAGGTAGCCTCTTTGTCCC-3’); ANLN (forward: 5’-AGCCACAAGCAGCAGATACCA-3’, reverse: 5’-ATGGCATTGGTGAGAAGAGTGAG-3’); CDCA5 (forward: 5’-CCGAGCATCCTCCCTGAAAT-3’, reverse: 5’-CAAGAAAAAGGAAATCCTAGGGC-3’); OIP5 (forward: 5’-GATTGCAGAGCTGAAAGAGAAGATA-3’, reverse: 5’-AGACAGCAATAAAGCCTGAACCT-3’). The qPCR conditions were 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 30 s, with a melt curve analysis at the end. Data were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method, and all experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the risk score served as an independent prognostic factor. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank tests were used to compare survival differences between groups. The predictive performance of the models was assessed using ROC curves and time-dependent ROC curves.

Results

Gene expression network analysis reveals key prognostic genes in LUAD

To identify key genes and potential molecular mechanisms associated with the prognosis of non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), we conducted a comprehensive analysis of 867 LUAD samples derived from the GSE31210, GSE13213, and TCGA-LUAD datasets. By integrating Mendelian randomization (MR) and differential expression analysis, we identified 26 significantly associated genes and constructed an interaction network for these genes (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Network analysis highlighted CDCA3, C4BPA, NICN1, and AMT as central nodes, suggesting that these genes may play crucial roles in the initiation and progression of LUAD. Notably, CDCA3, a cell cycle regulator, has been previously linked to tumor progression and prognosis in various cancers32. C4BPA (Complement Component 4 Binding Protein Alpha), involved in the regulation of the complement system, may have an underexplored role in tumor immunity33.

Fig. 1.

Integrated multi-dataset analysis and survival curves of prognostic genes in lung adenocarcinoma. (A) Expression profiles were derived from the integration of three datasets—GSE31210 (226 tumor samples), GSE13213 (117 tumor samples), and TCGA-LUAD (524 tumor samples)—with batch effects removed, resulting in a final dataset comprising 15,888 genes across 867 samples. The figure displays correlation analysis of 206 genes selected from the 321 identified in Sup-Table 3. Purple circles on the right represent risk factors for prognosis, while green circles indicate protective factors, with circle size proportional to the P-value. Lines denote significant correlations between metabolism-related pathways (P < 0.0001). (B–Z) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for tumor subtypes identified based on 26 genes with P-values < 0.05 in Cox regression analysis. Genes with log-rank test P-values < 0.001 are shown. Red lines indicate the high-expression group, blue lines indicate the low-expression group, and shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals. The number of samples at each time point is shown below the horizontal axis.

Survival analysis further confirmed the clinical relevance of these genes (Fig. 1B). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of 26 representative genes revealed significant survival differences for several genes (p < 0.001). For instance, high expression of AMT, CLDN18, CYP4B1, and SGCG was associated with better overall survival (OS), whereas high expression of CENPN, OPN3, and MRPS7 correlated with poorer OS.

Identification of molecular subtypes and their clinical characteristics

Based on the expression profiles of the prognostic genes, we employed consensus clustering to classify LUAD samples into two distinct molecular subtypes (Fig. 2A). The optimal clustering was observed at k = 2, indicating that LUAD patients may exhibit two predominant molecular characteristic patterns. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed a significant survival difference between these two subtypes (p < 0.001, Fig. 2B), with subtype A showing higher overall survival, whereas subtype B was associated with a poorer prognosis. We observed differential expression of a range of genes between the two subtypes (Fig. 2C), and these subtypes also differed in clinical features such as TNM stage, age, and gender. Boxplot analysis (Fig. 2D) further quantified the expression differences of key genes between the subtypes; for instance, CDCA3 and C4BPA were highly expressed in subtype A and lowly expressed in subtype B, potentially explaining the observed survival differences. Functional enrichment analysis (Fig. 2E) demonstrated that the differentially expressed genes were primarily involved in critical biological processes such as the proteasome, cell cycle, DNA replication, and repair. KEGG and Reactome pathway analyses revealed potential regulatory roles of these genes in apoptosis, ATM, and p53 pathways. Additionally, HALLMARK gene set analysis further indicated that these differential genes were closely associated with several hallmark processes of cancer, including the G2M checkpoint, E2F targets, mitotic spindle, and DNA repair.

Fig. 2.

Identification and clinical characterization of LUAD molecular subtypes. (A) Consensus clustering analysis based on 26 prognostic genes classified LUAD samples into two molecular subtypes (k = 2). The consensus matrix shows the classification results of samples within the two subtypes.(B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrate the survival differences between the two subtypes. Patients in subtype A (orange) have significantly higher overall survival than those in subtype B (blue) (P < 0.001). (C) The heatmap displays the expression patterns of the 26 genes across the two subtypes, with different colors representing varying levels of gene expression. (D) Box plots present the expression differences of key genes between the two subtypes. Genes such as CDCA3 and C4BPA are highly expressed in subtype A and lowly expressed in subtype B. (E) The heatmap of pathway activity differences based on GSVA analysis shows the pathways with significant differences between the two subtypes, including the proteasome, cell cycle, DNA replication, and repair.

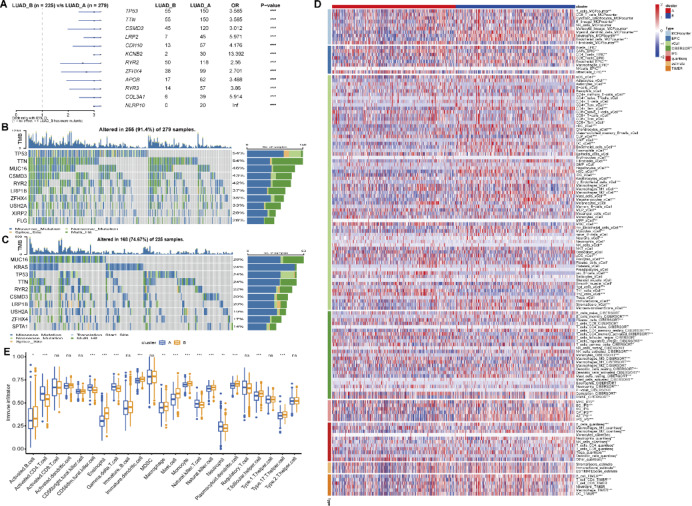

Association analysis of LUAD genomic variations and molecular subtypes with immune microenvironment characteristics

Whole-genome sequencing analysis revealed a complex landscape of genomic variations in LUAD. TP53, TTN, and MUC16 were identified as the most frequently mutated genes in LUAD, with mutations detected in 64%, 54%, and 46% of samples, respectively (Fig. 3B and C). Certain gene mutations were significantly associated with specific molecular subtypes; for instance, mutations in CSMD3 and LRP1B were more prevalent in subtype A, whereas TP53 and TTN mutations were more commonly observed in subtype B (Fig. 3A-C). This association suggests that distinct subtypes may possess unique oncogenic mechanisms and evolutionary trajectories.

Fig. 3.

Molecular subtype analysis of genomic variations and immune microenvironment characteristics in LUAD. (A) Analysis of gene mutation differences between the two molecular subtypes. Blue indicates mutations more common in subtype A, while green indicates mutations more common in subtype B. (B) Waterfall plot of gene mutations in subtype A, showing the distribution of major mutated genes such as TP53, TTN, and MUC16 across samples. (C) Waterfall plot of gene mutations in subtype B, displaying the distribution of subtype B-specific mutated genes. (D) Heatmap showing the relationship between molecular subtypes and immune cells in the immune microenvironment. Immune cell infiltration was assessed using eight methods: MCPcounter, EPIC, xCell, CIBERSORT, IPS, quanTIseq, ESTIMATE, and TIMER. (E) Immune cell infiltration scores calculated using the ssGSEA function from the R package GSVA, comparing the differences in immune cell infiltration levels between subtype A and subtype B.

To further understand the characteristics of the tumor microenvironment, we employed the R package IOBR to evaluate the association between molecular subtypes and various immune cell types in the immune microenvironment, using 8 different methods (MCPcounter, EPIC, xCell, CIBERSORT, IPS, quanTIseq, ESTIMATE, and TIMER) (Fig. 3D). Additionally, we utilized the ssGSEA function from the R package GSVA to calculate immune cell infiltration scores and compared the differences in immune cell infiltration between the subtypes (Fig. 3E). The results indicated that subtype B generally exhibited higher levels of immune cell infiltration, with significantly higher infiltration of activated B cells, CD4 + T cells, and macrophages compared to subtype A (p < 0.001). However, certain immune cell types, such as activated dendritic cells and regulatory T cells, did not show significant differences between the subtypes. These selective differences in immune cell infiltration may reflect distinct immune regulatory mechanisms inherent to each subtype.

Functional characteristics, gene networks, and key prognostic genes of LUAD molecular subtypes

We conducted an in-depth analysis of the functional characteristics and prognostic assessments of the two previously identified LUAD molecular subtypes. Principal component analysis (PCA) further confirmed the significant differences between these subtypes (Fig. 4A). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis revealed that cell cycle-related processes, such as nuclear division, chromosome segregation, and mitosis, were significantly enriched in these subtypes (Fig. 4B-D). GO Biological Processes (GO-BP) highlighted the importance of nuclear division and chromosome segregation, while GO Cellular Components (GO-CC) emphasized the enrichment of the spindle and chromosomal regions. GO Molecular Functions (GO-MF) pointed out the significance of glycosaminoglycan binding and microtubule binding. The functional network constructed based on differentially expressed genes displayed several key functional modules (Fig. 4E). For example, in the cell cycle module, the high connectivity of genes such as CCNB1, CDC20, and CDK1 was consistent with the GO analysis results. Additionally, the enrichment of genes like COL1A1 and COL5A1 in the extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor interaction module underscored the potential importance of the tumor microenvironment in LUAD progression.

Fig. 4.

Functional characteristics and gene network analysis of LUAD molecular subtypes. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot showing the distribution of LUAD samples, further confirming the significant differences between the two molecular subtypes. (B–D) GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes, displaying significant pathways in Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF). Gene enrichment is sorted by GeneRatio, with circle size representing the number of enriched genes and color indicating the P-value. (E) KEGG pathway analysis based on differentially expressed genes, illustrating the top 5 pathways and their associated genes.

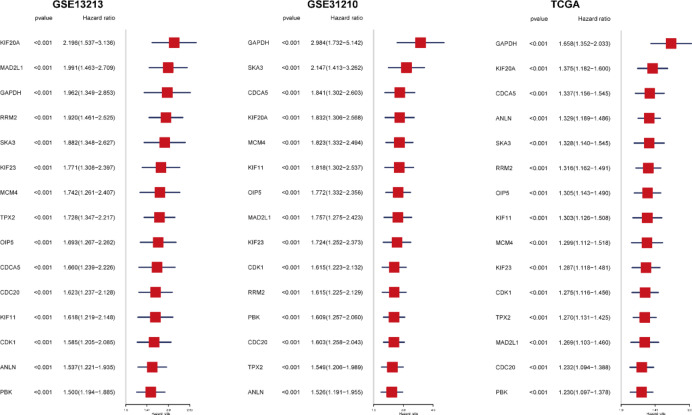

To validate the clinical significance of these key genes, we performed machine learning modeling on 1,383 genes and conducted Cox regression analysis in three independent cohorts (GSE13213, GSE31210, and TCGA) (Fig. 5). Genes with a p-value < 0.001 and a hazard ratio (HR) > 1 were defined as poor prognostic genes, ultimately identifying 15 genes consistently associated with poor prognosis across all datasets. Genes such as GAPDH, KIF20A, CDCA5, and SKA3 demonstrated significant prognostic relevance in all datasets (p < 0.001). Notably, KIF20A exhibited the highest hazard ratio in the GSE13213 cohort (HR = 2.196, 95% CI: 1.537–3.136), while GAPDH showed the strongest prognostic correlation in the GSE31210 cohort (HR = 2.984, 95% CI: 1.732–5.142). Although GAPDH had a relatively lower hazard ratio in the TCGA dataset, it remained a significant prognostic marker (HR = 1.658, 95% CI: 1.352–2.033). These consistent findings underscore the reliability of our discoveries and highlight the importance of these genes as potential prognostic markers. In particular, several genes related to cell cycle regulation, such as CDC20, CDK1, and MAD2L1, were also among the 15 poor prognostic genes, further supporting the targeting of cell cycle regulatory pathways as a potential direction for LUAD therapy.

Fig. 5.

Cox regression analysis of poor prognostic genes in LUAD molecular subtypes. Cox regression analysis was performed on 1383 genes using machine learning modeling across three independent datasets (GSE13213, GSE31210, and TCGA). The figure presents the results of univariate regression analysis for 15 genes identified as poor prognostic markers (P-value < 0.001, HR > 1) in all three datasets. In the forest plot, red squares represent the hazard ratio (HR), with horizontal lines indicating the 95% confidence intervals.

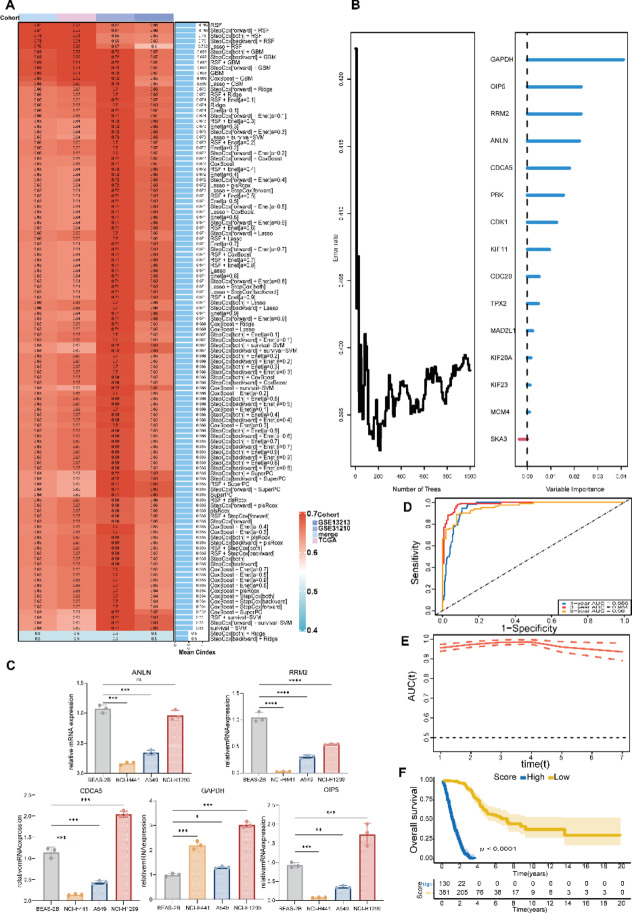

Construction of the machine learning model and evaluation of its predictive performance

Based on the identified key genes, we developed a machine learning model to predict the prognosis of LUAD patients. After comparing the performance of 10 different machine learning algorithms, the Random Survival Forest (RSF) model exhibited the best performance across multiple evaluation metrics (Fig. 6A). Figure 6B shows the importance ranking of variables in the RSF model, with genes such as GAPDH, OIP5, and RRM2 identified as the most significant contributors to prognostic prediction. We selected the top five genes for qPCR analysis (Fig. 6C), and the results revealed significant differences in expression between normal alveolar epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) and lung cancer cell lines. CDCA5 and OIP5 were significantly overexpressed in the NCI-H1299 cell line but showed lower expression levels in NCI-H441 and A549. GAPDH was highly expressed across all lung cancer cell lines, with the highest levels observed in NCI-H1299 and H441. In contrast, ANLN and RRM2 exhibited higher expression in normal cells compared to most lung cancer cell lines. These findings indicate distinct expression patterns of the target genes between normal and cancer cells. These results further validate the critical role of these genes in the prognosis of LUAD. In the training cohort (TCGA-LUAD). RSF model achieved AUC values of 0.82, 0.80, and 0.79 for predicting 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival, respectively (Fig. 6D), demonstrating excellent performance. The time-dependent ROC curves for the RSF model show consistently high AUC values of 0.82, 0.80, and 0.79 for 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year predictions, highlighting the model’s stability and reliability in long-term prognostic prediction(Fig. 6E). Based on the risk scores predicted by the model, patients were stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed a significant difference in survival rates between the two groups (p < 0.001, Fig. 6F), confirming the clinical relevance and potential application of this predictive model.

Fig. 6.

Construction and evaluation of the prognostic model for LUAD patients. (A) Prognostic models were constructed using 10 machine learning algorithms and their combinations, with TCGA data as the training set and other datasets as validation sets. The C-index for each model is presented, showing that the Random Survival Forest (RSF) model outperformed others across multiple evaluation metrics. (B) The contribution of key genes was determined based on variable importance rankings within the RSF model, and a prognostic scoring model was developed. (C) qPCR analysis of gene expression in different cell lines. (D) The prognostic performance of the RSF model was assessed in the TCGA training set. ROC curves display predictive performance at different time points (1-year, 3-year, and 5-year), with the area under the curve (AUC) indicating the accuracy of the model’s predictions. (E) Time-dependent ROC curves further evaluate the model’s predictive ability across various time points. (F) Patients were stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on risk scores predicted by the model, and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted, showing a significant difference in survival rates between the two groups (P < 0.001).

To validate the generalizability of the RSF model, we conducted external validation in two independent cohorts (GSE13213 and GSE31210). The TCGA dataset, used exclusively for model training and parameter optimization, was not employed as an independent validation cohort. The results showed that the RSF model had significant predictive power in both external validation cohorts (Fig. 7A-C). Further analysis indicated that the risk score was significantly associated with tumor stages, T stage (p < 0.001), N stage (p < 0.001), and M stage (p < 0.001) across the independent cohorts (Fig. 7D-G). However, no significant associations were observed between the risk score and patients’ age (Fig. 7H) or recurrence and metastasis status (Fig. 7I).

Fig. 7.

External validation and clinical correlation analysis of the prognostic model for LUAD patients. (A–C) The prognostic predictive ability of the RSF model was evaluated in the GSE31210, GSE13213, and MERGE datasets. For each dataset, the left panel shows the ROC curve, the middle panel presents the time-dependent ROC curve, and the right panel displays the Kaplan-Meier survival curve based on model predictions, illustrating the survival differences between the high-risk and low-risk groups. (D-I) The relationship between the risk scores predicted by the RSF model and clinical characteristics of patients was analyzed in the GSE31210, GSE13213, and MERGE datasets. Clinical characteristics include tumor stage (Stage), T stage, N stage, M stage, gender (Gender), and recurrence/metastasis status (Recurrence/Metastasis). Each group shows the differences in risk scores across various clinical characteristics and the corresponding distribution of patients.

RS confirmed as an independent prognostic factor

To evaluate the independence of the risk score (RS) in predicting the prognosis of LUAD patients, we conducted univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses (Fig. 8A and B). Univariate analysis showed that RS was significantly associated with overall survival (HR = 1.034, 95% CI: 1.020–1.038, p < 0.001). Multivariate analysis, after adjusting for age, gender, TNM stage, and other factors, further confirmed the independent prognostic value of RS (HR = 1.046, 95% CI: 1.028–1.064, p < 0.001). When patients were stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median RS, we compared the mutational profiles between these two groups (Fig. 8C and D). In the high-risk group (n = 149), TP53 (48%), TTN (46%), and MUC16 (39%) were the most frequently mutated genes, while these mutation frequencies were lower in the low-risk group (n = 342) (TP53: 38%, TTN: 38%, MUC16: 37%). Further analysis revealed that mutations in genes such as COL22A1 and PLXDC2 were significantly enriched in the high-risk group (Fig. 8E). For instance, the mutation frequency of COL22A1 was significantly higher in the high-risk group compared to the low-risk group (OR = 2.924, p < 0.001), and PLXDC2 also showed significant enrichment (OR = 10.872, p < 0.001). Additionally, genes such as TAAR5 and ZNF264, which had no mutations in the low-risk group, exhibited 6 mutations each in the high-risk group, indicating their potential importance.

Fig. 8.

Independent prognostic value of rs score and gene mutation analysis in high- and low-risk groups. (A) Univariate Cox regression analysis assessed the correlation between the RS score and overall survival, demonstrating that the RS score is significantly associated with overall survival in LUAD patients (P < 0.001). (B) Multivariate Cox regression analysis, adjusted for factors such as age, gender, and TNM stage, further validated the RS score as an independent prognostic factor (P < 0.001). (C,D) Patients were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median RS score, and the gene mutation profiles of each group were presented. In the high-risk group, genes such as TP53, TTN, and MUC16 showed higher mutation frequencies, while these mutations were relatively less frequent in the low-risk group. (E) Comparative analysis of gene mutation differences between high-risk and low-risk groups revealed significant enrichment of specific gene mutations in the high-risk group, such as COL22A1 and PLXDC2. These mutations were either not detected or were less frequent in the low-risk group.

To further understand the biological significance of RS, we analyzed the correlation between RS and gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 1A and 1B). A heatmap displayed the top 50 positively and negatively correlated genes with RS. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) results indicated that RS-related7 genes were enriched in several cell cycle-related processes, including chromosome organization, DNA replication, and sister chromatid segregation (Supplementary Fig. 1 C). These findings suggest that RS may influence LUAD progression and patient prognosis by affecting cell cycle regulation.

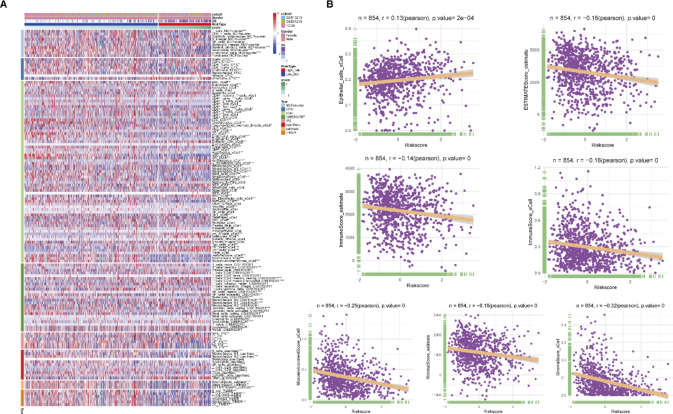

RS reflects the heterogeneity of the tumor immune microenvironment

To explore the relationship between the tumor immune microenvironment and the risk score (RS), we analyzed the immune cell infiltration levels in the high- and low-risk groups. The results showed significant differences in various immune cell types and functions between the risk groups (Fig. 9A), with patients in the high-risk group exhibiting lower levels of immune cell infiltration. The immune cell infiltration in the high-risk group was significantly lower, particularly in T cells, B cells, and NK cells, suggesting possible immune suppression, which may lead to tumor immune evasion. Correlation analysis further revealed that RS was generally negatively correlated with components of the tumor microenvironment, including immune cells and stromal cells, suggesting that higher risk may be associated with lower immune/stromal cell infiltration. As RS increases, immune activity and stromal content in the tumor microenvironment may decrease. Notably, epithelial cells (r = 0.13, p < 0.001) were weakly positively correlated with RS, possibly reflecting a proliferative advantage of tumor cells in high-risk patients, which may be related to tumor progression and immune evasion mechanisms (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Analysis of the relationship between rs score and tumor immune microenvironment. (A) The heatmap shows the relationship between RS score and the infiltration levels of various immune cells. Different colors in the heatmap represent the immune cell infiltration levels in the high- and low-risk groups. (B) Correlation analysis between RS score and tumor microenvironment-related scores, illustrating the associations between RS score and different components of the tumor microenvironment, including immune cells and stromal cells. In the scatter plots, each point represents a sample, and the regression line indicates the trend between RS score and tumor microenvironment scores.

RS is closely associated with the expression of key cytokines and receptors

To further understand the molecular basis of the RS score, we analyzed its relationship with cytokine and receptor expression. Heatmap analysis revealed significant differences in the expression of various cytokines and receptors between the high- and low-risk groups (Fig. 10A). Quantitative analysis further demonstrated that CCL17 (r = -0.24, p < 0.001), CCR2 (r = -0.23, p < 0.001), and CCR4 (r = -0.2, p < 0.001) were significantly negatively correlated with RS, indicating higher expression of these factors in the low-risk group. Conversely, CCL20 (r = 0.2, p < 0.001) was positively correlated with RS and was more highly expressed in the high-risk group (Fig. 10B). CCL17, CCR2, and CCR4 are typically associated with T cell recruitment and activation, and their higher expression in the low-risk group may reflect a stronger anti-tumor immune response. In contrast, the elevated expression of CCL20, which has been reported to be associated with tumor invasiveness and poor prognosis, aligns with its upregulation in the high-risk group. These findings suggest that the RS score may influence tumor progression and patient prognosis through specific patterns of cytokine and receptor expression, providing potential targets for the development of cytokine network-based therapeutic strategies.

Fig. 10.

Analysis of the relationship between rs score and the expression of chemokines and their receptors. (A) The heatmap illustrates the relationship between RS score and the expression levels of various chemokines and their receptors. Different colors represent the expression levels of these factors in the high- and low-risk groups. (B) Correlation analysis between RS score and specific chemokines and their receptors. The scatter plots display the correlation between RS score and the expression of factors such as CCL17, CCR2, CCR4, and CCL20. Each point represents a sample, and the regression line indicates the trend between RS score and the expression levels of these factors.

RS model predicts immunotherapy response and drug sensitivity

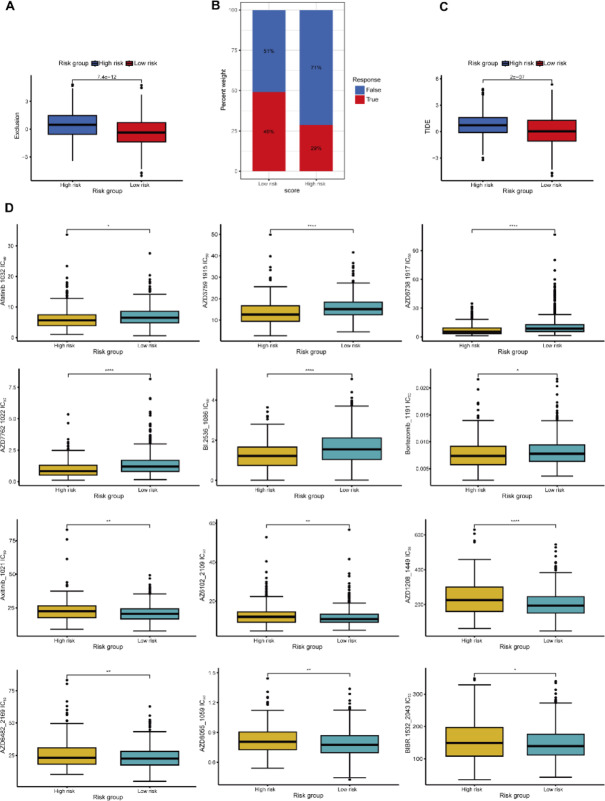

To evaluate the potential of the risk score (RS) model in guiding treatment decisions, we conducted analyses on immunotherapy response and drug sensitivity. Using the TIDE algorithm, we found that patients in the high-risk group had significantly higher immune exclusion scores compared to those in the low-risk group (p = 7.4e-12, Fig. 11A), indicating a lower predicted response rate to immunotherapy (29% vs. 49%, Fig. 11B) and higher TIDE scores (p = 2e-07, Fig. 11C). These findings suggest that patients classified as high-risk by the RS model may have a poorer response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. In the anticancer drug sensitivity prediction analysis using the oncoPredict package, we observed significant differences in IC50 values between high- and low-risk groups for several drugs (e.g., A-20292, AZD7762, BI-2536) (Fig. 11D). Notably, Bortezomib exhibited a lower IC50 value in the high-risk group, suggesting that these patients may be more sensitive to this drug. However, for some drugs, such as Axitinib, the IC50 differences between the two groups were not significant, indicating that the RS model may have limitations in predicting sensitivity to certain drugs.

Fig. 11.

Application of the RS model in predicting immunotherapy response and drug sensitivity analysis. (A-C) The TIDE database was used to predict TIDE scores and immunotherapy efficacy in LUAD patients. Panel (A) shows the differences in immune exclusion scores between high- and low-risk groups, panel (B) illustrates the proportion of immunotherapy responders in each risk group, and panel (C) displays the differences in TIDE scores between the high- and low-risk groups. (D) The R package oncoPredict was used to predict the IC50 values of various anticancer drugs, comparing drug sensitivity differences between the high- and low-risk groups. Each subplot presents the distribution of IC50 values for a specific drug, with higher IC50 values indicating lower treatment sensitivity.

Discussion

Lung cancer remains one of the most prevalent and deadly malignancies worldwide, with lung adenocarcinoma being the primary subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)34. In recent years, extensive research into the molecular mechanisms of lung cancer has deepened our understanding of its initiation, progression, and prognosis35,36. Genomic studies have identified numerous driver gene mutations in lung adenocarcinoma, such as EGFR, KRAS, ALK, and ROS1, which not only play critical roles in tumor development but are also closely associated with patient treatment response and prognosis37,38. Targeted therapies against these mutations, such as EGFR-TKIs and ALK inhibitors, have significantly improved the survival outcomes for some lung adenocarcinoma patients39. However, heterogeneity and the complex interplay of molecular pathways further complicate treatment strategies40. In this study, by integrating multi-omics data and bioinformatics approaches, we thoroughly explored the molecular characteristics, prognostic markers, and potential therapeutic targets of non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). Our study innovatively combines Mendelian Randomization (SMR) with machine learning methods, achieving a breakthrough by integrating gene expression, mutation, and clinical data. By incorporating causal inference to identify key genes and utilizing machine learning to construct more accurate prognostic models, our study represents a significant advancement in this field.

Through Mendelian randomization (MR) and differential expression analysis, we identified 206 genes significantly associated with LUAD. Among these, CDCA3, C4BPA, NICN1, and AMT exhibited high connectivity within the interaction network, suggesting that they may play critical roles in the development and progression of LUAD. Notably, CDCA3, a cell cycle regulator, has been reported to be associated with tumor progression and prognosis in various cancers43. Based on the expression profiles of these key genes, we successfully classified LUAD patients into two molecular subtypes with significant survival differences. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that these differentially expressed genes are primarily enriched in processes such as cell cycle regulation, DNA replication, and repair.

Our study also uncovered the complex genomic variation landscape in LUAD and identified specific gene mutations that are significantly associated with particular molecular subtypes. For instance, mutations in TP53 and TTN were more prevalent in the B subtype, which is associated with poorer prognosis, suggesting that different subtypes may have distinct oncogenic mechanisms and evolutionary trajectories. This finding further supports the critical role of TP53 mutations in LUAD44. In terms of the immune microenvironment, we observed that the B subtype exhibited higher levels of immune cell infiltration, particularly of activated B cells, CD4 + T cells, and macrophages. This difference may reflect subtype-specific immune regulatory mechanisms. Through stringent selection criteria and multi-cohort validation, we ultimately identified 15 genes that consistently acted as poor prognostic markers across all datasets, including GAPDH, KIF20A, CDCA5, and SKA3. Notably, KIF20A and GAPDH demonstrated significant prognostic relevance in different cohorts, underscoring the importance of these genes as potential prognostic biomarkers. It is also noteworthy that several genes related to cell cycle regulation, such as CDC20, CDK1, and MAD2L1, were among these 15 poor prognostic genes, further reinforcing the potential of targeting cell cycle regulatory pathways as a therapeutic direction for LUAD45.

Based on these key genes, we developed a machine learning model to predict the prognosis of LUAD patients. The Random Survival Forest (RSF) model outperformed other methods across multiple evaluation metrics and was validated in three independent cohorts. This model not only excelled in prognostic prediction but also highlighted the significant contributions of genes such as GAPDH, OIP5, and RRM2 to prognosis prediction. The qPCR results suggest that the elevated expression of CDCA5 and OIP5 in NCI-H1299 cells may be associated with malignant proliferation in lung cancer46. The widespread upregulation of GAPDH reflects its critical role in tumor metabolism47. In contrast, ANLN and RRM2 exhibit higher expression in normal epithelial cells but are suppressed in most lung cancer cell lines, suggesting that they may play important roles in maintaining normal cellular homeostasis while being influenced by specific regulatory mechanisms during malignant transformation. These differences in gene expression patterns highlight the complex roles of the tumor microenvironment and transcriptional regulation in cancer development. These differences reveal the complex regulatory mechanisms of gene expression and provide new perspectives for studying the molecular mechanisms of lung cancer and developing targeted therapies.

Our study also found that the risk score (RS) was negatively correlated with immune activity and stromal components in the tumor microenvironment, suggesting that high-risk patients may possess an immunosuppressive microenvironment, which could be a contributing factor to poor prognosis. Additionally, RS was closely associated with the expression of specific cytokines and receptors, such as CCL17, CCR2, and CCR4, which were significantly negatively correlated with RS, while CCL20 was positively correlated with RS. CCL17, CCR4, and CCR2 regulate immune responses in the tumor microenvironment by recruiting and activating T cells and macrophages, thereby enhancing anti-tumor immunity48–50. Inhibitors targeting CCR2, in particular, M2-type tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) derived from CCR2 play a pivotal role in promoting tumor immune suppression and angiogenesis51. The combination of CCR4 inhibitors with immune checkpoint inhibitors (CPI) holds significant clinical potential in enhancing anti-tumor immunity, particularly by reducing the role of Tregs in tumor immune evasion50. The overexpression of CCL20 is associated with tumor cell aggressiveness and poor prognosis. High levels of CCL20 are linked to tumor metastasis and more invasive phenotypes52. Therefore, therapeutic strategies targeting CCL20 or its receptor CCR6 hold promise in reducing tumor invasiveness and metastatic potential, thereby inhibiting tumor progression and laying the groundwork for the development of anti-CCL20 antibodies or small-molecule inhibitors. These findings suggest that RS may influence tumor progression and patient prognosis by reflecting specific cytokine networks, providing potential targets for the development of cytokine network-based therapeutic strategies.

Finally, our study explored the potential of the RS model in guiding treatment decisions. Using the TIDE algorithm, we predicted that patients in the high-risk group might have a poorer response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, which aligns with recent findings on the relationship between the tumor immune microenvironment and immunotherapy response53. This discovery provides new evidence for developing personalized immunotherapy strategies. Additionally, drug sensitivity analysis revealed differences in drug sensitivity between high- and low-risk groups, offering potential guidance for individualized pharmacotherapy based on the RS model.

Despite the significant findings of this study, several limitations remain to be addressed. First, although the model was validated across multiple independent cohorts, its clinical utility requires further confirmation through prospective clinical trials. Second, while this study identified potential therapeutic targets and prognostic markers, their underlying molecular mechanisms need to be further elucidated through functional experiments. Additionally, the public datasets used in this study include heterogeneous clinicopathological characteristics and treatment strategies, which may introduce inconsistencies in patient management and impact the reliability of survival analysis.Furthermore, this study utilized integrative multi-omics data and expression feature analysis to uncover the molecular heterogeneity and key prognostic genes of LUAD. However, analyzing mutation co-occurrence and mutual exclusivity is critical for exploring oncogenic driving mechanisms and their prognostic implications54–57.Future research will focus on validating the expression and clinical relevance of the gene set in a proprietary cohort with standardized treatment protocols using immunohistochemistry (IHC). Additionally, we plan to investigate the associations between the gene set and clinicopathological features, therapeutic responses, and clinical outcomes to enhance its translational potential.Finally, we aim to build upon the key gene expression features identified in this study to further explore the complex relationships among mutation patterns, molecular subtypes, and patient prognosis in LUAD. Such integration will facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of LUAD’s oncogenic mechanisms and provide more specific guidance for optimizing individualized therapeutic strategies. This also offers a promising direction for future research to delve deeper into the molecular characteristics of LUAD at the genomic variation level.

In conclusion, this study, through multi-omics integrative analysis, not only revealed the molecular heterogeneity and key prognostic genes of LUAD but also developed a risk score model that shows promise for guiding personalized treatment and prognostic prediction. These findings offer new perspectives and potential strategies for the precise diagnosis and treatment of LUAD. Future research should aim to further validate the clinical applicability of these findings and explore the underlying molecular mechanisms to advance LUAD therapy.

Conclusion

This study, through the integration of multi-omics data, thoroughly explored the molecular characteristics, prognostic markers, and potential therapeutic targets of non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). By utilizing Mendelian randomization and differential expression analysis, we identified 206 key genes significantly associated with LUAD and successfully classified LUAD patients into two molecular subtypes with significant survival differences based on the expression profiles of these genes. Additionally, the Random Survival Forest (RSF) model we developed demonstrated excellent performance across multiple independent cohorts, providing high accuracy in prognostic prediction and revealing the crucial roles of key genes such as GAPDH, OIP5, and RRM2 in LUAD prognosis. Furthermore, we discovered that the risk score (RS) was negatively correlated with immune activity and stromal components in the tumor microenvironment, suggesting that high-risk patients may have an immunosuppressive microenvironment, which could be a critical factor contributing to poor prognosis. RS was also closely associated with the expression of specific cytokines and receptors, indicating that RS may influence tumor progression and patient prognosis through specific cytokine networks. This study offers new perspectives for the precision diagnosis and treatment of LUAD and provides potential targets for developing cytokine network-based therapeutic strategies. Future research should aim to further validate the clinical applicability of these findings and explore the underlying molecular mechanisms to advance the treatment of LUAD.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

(I) Conception and design: Baozhen Wang, Yichen Yin, Jing Chen and Tao Li; (II) Administrative support: Jing Chen and Tao Li; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: Jing Chen and Tao Li; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Baozhen Wang, Yichen Yin, Anqi Wang, Weidi Liu; (V) Data analysis: Baozhen Wang and Yichen Yin (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060663, 82260716), the Key Research and Development Program of Ningxia (2023BEG02010).

Data availability

Data Availability Statement: The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are publicly available in the following repositories:1. TCGA-LUAD (524 tumor samples): This dataset was used in Figs. 1, 2, 5, 6 and 7, and 8 for integration with other datasets and to train the prognostic models. It is available from the UCSC-XENA repository, accessible at https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/0.2. GSE31210 (226 tumor samples) and GSE13213 (117 tumor samples): These datasets were used in Figs. 1, 2, 5 and 6, and 7 for external validation and molecular subtype analysis, and are available in the GEO repository, accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/0.3. Finnish R9 lung adenocarcinoma dataset: This dataset, used for survival analysis in Sup-Table 1 and gene mutation analysis in Figs. 8 and 9, and 10, includes 1,553 NSCLC adenocarcinoma patients and 287,137 controls. It is available at https://storage.googleapis.com/finngen-public-data-r9/summary_stats/finngen_R9_C3_NSCLC_ADENO_EXALLC.gz.All datasets are publicly accessible and can be obtained through the provided links. No restrictions apply to the availability of these datasets.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the final manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Baozhen Wang and Yichen Yin contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jing Chen, Email: 20040009@nxmu.edu.cn.

Tao Li, Email: lit1979@163.com.

References

- 1.Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12 (1), 31–46. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araghi, M. et al. Recent advances in non-small cell lung cancer targeted therapy; an update review. Cancer Cell. Int.23 (1), 162. 10.1186/s12935-023-02990-y (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu, S. Y. M. et al. Emerging evidence and treatment paradigm of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol.16 (1), 40. 10.1186/s13045-023-01436-2 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstraw, P. et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol.11 (1), 39–51. 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He, S. et al. Survival of 7311 lung cancer patients by pathological stage and histological classification: a multicenter hospital-based study in China. Transl. Lung Cancer Res.11 (8), 1591–1605. 10.21037/tlcr-22-240 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimner, A. et al. The International Association for the study of lung cancer thymic epithelial tumors staging project: an overview of the central database informing revision of the forthcoming (ninth) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumors. J. Thorac. Oncol.18 (10), 1386–1398. 10.1016/j.jtho.2023.07.008 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duma, N., Santana-Davila, R. & MolinaJR Non–small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc.94 (8), 1623–1640. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.013 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, M., Herbst, R. S. & Boshoff, C. Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med.27 (8), 1345–1356. 10.1038/s41591-021-01450-2 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, M. Y., Liu, L. Z. & Dong, M. Progress on pivotal role and application of exosome in lung cancer carcinogenesis, diagnosis, therapy and prognosis. Mol. Cancer20 (1), 22. 10.1186/s12943-021-01312-y (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horvath, L., Thienpont, B., Zhao, L., Wolf, D. & Pircher, A. Overcoming immunotherapy resistance in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) - novel approaches and future outlook. Mol. Cancer19 (1), 141. 10.1186/s12943-020-01260-z (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He, J., Huang, Z., Han, L., Gong, Y. & Xie, C. Mechanisms and management of 3rd–generation EGFR–TKI resistance in advanced non–small cell lung cancer (review). Int. J. Oncol.59 (5), 90. 10.3892/ijo.2021.5270 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedlaender, A. et al. Role and impact of immune checkpoint inhibitors in neoadjuvant treatment for NSCLC. Cancer Treat. Rev.104, 102350. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102350 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, Y., Gao, M., Huang, Z., Yu, J. & Meng, X. SBRT combined with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in NSCLC treatment: a focus on the mechanisms, advances, and future challenges. J. Hematol. Oncol.13 (1), 105. 10.1186/s13045-020-00940-z (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thai, A. A., Solomon, B. J., Sequist, L. V., Gainor, J. F. & Heist, R. S. Lung cancer. Lancet398 (10299), 535–554. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00312-3 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zugazagoitia, J. et al. Biomarkers associated with beneficial PD-1 checkpoint blockade in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) identified using high-plex digital spatial profiling. Clin. Cancer Res.26 (16), 4360–4368. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0175 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imyanitov, E. N., Iyevleva, A. G. & Levchenko, E. V. Molecular testing and targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: current status and perspectives. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol.157, 103194. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103194 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin, X. et al. RUNX2 recruits the NuRD(MTA1)/CRL4B complex to promote breast cancer progression and bone metastasis. Cell. Death Differ.29 (11), 2203–2217. 10.1038/s41418-022-01010-2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pirooznia, M. et al. Recent advances in the molecular genetics and precision medicine of lung carcinoma. Front. Genet.15, 1369247. 10.3389/fgene.2024.1369247 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neophytou, C. M., Trougakos, I. P., Erin, N. & Papageorgis, P. Apoptosis deregulation and the development of cancer multi-drug resistance. Cancers13 (17), 4363. 10.3390/cancers13174363 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, Z., Song, W., Rubinstein, M. & Liu, D. Recent updates in cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive review and perspective of the 2018 China Cancer Immunotherapy Workshop in Beijing. J. Hematol. Oncol.11 (1), 142. 10.1186/s13045-018-0684-3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monteran, L. & Erez, N. The dark side of fibroblasts: cancer-associated fibroblasts as mediators of immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol.10, 1835. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01835 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erin, N., Grahovac, J., Brozovic, A. & Efferth, T. Tumor microenvironment and epithelial mesenchymal transition as targets to overcome tumor multidrug resistance. Drug Resist. Updates. 53, 100715. 10.1016/j.drup.2020.100715 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao, X. et al. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer. 20 (1), 131. 10.1186/s12943-021-01428-1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennan, P., Hainaut, P. & Boffetta, P. Genetics of lung-cancer susceptibility. Lancet Oncol.12 (4), 399–408. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70126-1 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, K. & Han, S. Effect of selection bias on two sample summary data based mendelian randomization. Sci. Rep.11 (1), 7585. 10.1038/s41598-021-87219-6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishnamoorthy, S., Li, G. H. Y. & Cheung, C. Transcriptome‐wide summary data‐based mendelian randomization analysis reveals 38 novel genes associated with severe COVID‐19. J. Med. Virol.95 (1), e28162. 10.1002/jmv.28162 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.43 (7), e47. 10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leek, J. T. & Storey, J. D. Capturing heterogeneity in gene expression studies by surrogate variable analysis. PLoS Genet.3 (9), 1724–1735. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030161 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkerson, M. D. & Hayes, D. N. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics26 (12), 1572–1573. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq170 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform.14, 7. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayakonda, A., Lin, D. C., Assenov, Y., Plass, C. & Koeffler, H. P. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res.28 (11), 1747–1756. 10.1101/gr.239244.118 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchida, F. et al. Overexpression of cell cycle regulator CDCA3 promotes oral cancer progression by enhancing cell proliferation with prevention of G1 phase arrest. BMC Cancer. 12, 321. 10.1186/1471-2407-12-321 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ricklin, D., Hajishengallis, G., Yang, K. & Lambris, J. D. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat. Immunol.11 (9), 785–797. 10.1038/ni.1923 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics. : GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71(3), 209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Herbst, R. S., Morgensztern, D. & Boshoff, C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature553 (7689), 446–454. 10.1038/nature25183 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rotow, J. & Bivona, T. G. Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in NSCLC. Nat. Rev. Cancer17 (11), 637–658. 10.1038/nrc.2017.84 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skoulidis, F. & Heymach, J. V. Co-occurring genomic alterations in non-small-cell lung cancer biology and therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer19 (9), 495–509. 10.1038/s41568-019-0179-8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pao, W. & Girard, N. New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol.12 (2), 175–180. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70087-5 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Remon, J. et al. Advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer: advances in thoracic oncology 2018. J. Thorac. Oncol.14 (7), 1134–1155. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.03.022 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jamal-Hanjani, M. et al. Tracking the evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl. J. Med.376 (22), 2109–2121. 10.1056/NEJMoa1616288 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirsch, F. R. et al. Lung cancer: current therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet389 (10066), 299–311. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30958-8 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Passaro, A. et al. Recent advances on the role of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the management of NSCLC with uncommon, non exon 20 insertions, EGFR mutations. J. Thorac. Oncol.16 (5), 764–773. 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.12.002 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, Y. et al. CDCA3 is a potential prognostic marker that promotes cell proliferation in gastric cancer. Oncol. Rep.41 (4), 2471–2481. 10.3892/or.2019.7008 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavin, Y. et al. Innate immune landscape in early lung adenocarcinoma by paired single-cell analyses. Cell169 (4), 750–765e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.014 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park, W. H. Ebselen inhibits the growth of lung cancer cells via cell cycle arrest and cell death accompanied by glutathione depletion. Molecules28 (18), 6472. 10.3390/molecules28186472 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen, M. H. et al. Phosphorylation and activation of cell division cycle associated 5 by mitogen-activated protein kinase play a crucial role in human lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Res.70 (13), 5337–5347. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4372 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yun, J. et al. Vitamin C selectively kills KRAS and BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH. Science350 (6266), 1391–1396. 10.1126/science.aaa5004 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maeda, S. et al. BRAFV595E mutation associates CCL17 expression and regulatory T cell recruitment in urothelial carcinoma of dogs. Vet. Pathol.58 (5), 971–980. 10.1177/0300985820967449 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson, J. J. et al. Discovery of a potent and selective CCR4 antagonist that inhibits Treg trafficking into the tumor microenvironment. J. Med. Chem.62 (13), 6190–6213. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00506 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marshall, L. A. et al. Tumors establish resistance to immunotherapy by regulating Treg recruitment via CCR4. J. Immunother Cancer8 (2), e000764. 10.1136/jitc-2020-000764 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gambardella, V. et al. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in gastric cancer development and their potential as a therapeutic target. Cancer Treat. Rev.86, 102015. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102015 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kadomoto, S., Izumi, K. & Mizokami, A. The CCL20-CCR6 axis in cancer progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21 (15), 5186. 10.3390/ijms21155186 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma, P., Hu-Lieskovan, S., Wargo, J. A. & Ribas, A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell168 (4), 707–723. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.El Tekle, G. et al. Co-occurrence and mutual exclusivity: what cross-cancer mutation patterns can tell us. Trends Cancer7 (9), 823–836. 10.1016/j.trecan.2021.04.009 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li, G. et al. Mutual exclusivity and co-occurrence patterns of immune checkpoints indicate NKG2A relates to anti-PD-1 resistance in gastric cancer. J. Transl. Med.22 (1), 718. 10.1186/s12967-024-05503-1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scharpf, R. B. et al. Genomic landscapes and hallmarks of mutant RAS in human cancers. Cancer Res.82 (21), 4058–4078. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-1731 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vokes, N. I. et al. ATM mutations associate with distinct co-mutational patterns and therapeutic vulnerabilities in NSCLC. Clin. Cancer Res.29 (23), 4958–4972. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-23-1122 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability Statement: The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are publicly available in the following repositories:1. TCGA-LUAD (524 tumor samples): This dataset was used in Figs. 1, 2, 5, 6 and 7, and 8 for integration with other datasets and to train the prognostic models. It is available from the UCSC-XENA repository, accessible at https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/0.2. GSE31210 (226 tumor samples) and GSE13213 (117 tumor samples): These datasets were used in Figs. 1, 2, 5 and 6, and 7 for external validation and molecular subtype analysis, and are available in the GEO repository, accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/0.3. Finnish R9 lung adenocarcinoma dataset: This dataset, used for survival analysis in Sup-Table 1 and gene mutation analysis in Figs. 8 and 9, and 10, includes 1,553 NSCLC adenocarcinoma patients and 287,137 controls. It is available at https://storage.googleapis.com/finngen-public-data-r9/summary_stats/finngen_R9_C3_NSCLC_ADENO_EXALLC.gz.All datasets are publicly accessible and can be obtained through the provided links. No restrictions apply to the availability of these datasets.