Abstract

A variety of medical specialities undertake percutaneous drainage but understanding of device performance outside radiology is often limited. Furthermore, the current catheter sizing using the “French” measurement of outer diameter is unhelpful; it does not reflect the internal diameter and gives no information on flow rate. To illustrate this and to improve catheter selection, notably for chest drainage, we assessed the variation of drain performance under standardised conditions. Internal diameter and flow rates of 6Fr.-12Fr. drainage catheters from 8 manufacturers were tested to ISO 10555-1 standard: Internal diameters were measured with Meyer calibrated pin-gauges. Flow rates were calculated over a period of 30s after achieving steady state. Evaluation demonstrated a wide range of internal diameters for the 6Fr., 8Fr., 10Fr. and 12Fr. catheters. Mean measurements were 1.49 mm (SD:0.07), 1.90 mm (SD:0.10), 2.43 mm (SD:0.11) and 2.64 mm (SD:0.03) respectively. Mean flow rates were 128 mL/min (SD:37.6), 207 mL/min (SD: 55.1), 291 mL/min (SD:36.7) and 303 mL/min (SD:20.2) respectively. There was such variance that there was overlap between catheters of different size: thin-walled 10Fr. drains performed better than 12Fr. “Seldinger” chest drains. Better understanding of drain characteristics and better declaration of performance data by manufacturers are required to allow optimum drain choice for individual patients and optimum outcomes.

Subject terms: Lung cancer, Materials for devices

Introduction

Percutaneous drainage of pleural effusions and other fluid collections is a common minimally invasive procedure which has the potential for immediate symptom relief and can be life-saving.1,2 It is a procedure used by radiologists, physicians and surgeons for different purposes, but different specialties have developed different philosophies, notably about the size of the drainage catheter. However, understanding the properties of different catheters is vital in putting them to best use.

Categorising drains into “small” and “large” is entirely arbitrary. The unit “French”, in urinary catheters also called “Charrière”, is named after Joseph-Frédéric-Benoît Charrière, a 19th Century Parisian cutler and reflects the outer diameter of the drain multiplied by three.3,4 This means a 12 Fr. drain has a 4mm diameter and a 9 Fr. catheter a 3mm diameter. It is crucial to understand that this reflects the outer diameter of drain only, and does not contain any information on the size of the inner lumen, which represents the actual drainage channel. Hagen-Poiseuille’s law dictates that the resistance and flow through a pipe is related by the fourth exponent to the radius, which means that a small change in diameter results in a marked change of resistance and flow5. It has to be taken into account that this applies to non-compressible ideal fluids passing in a laminar flow through a straight pipe and that there is significant variation in viscosity of bodily fluids6. Nevertheless this highlights the importance of an adequate lumen. The pitfall in drain sizing is that the French system used does not consider the wall thickness of the catheter and therefore gives no or misleading information on the actual drainage potential. As a consequence, it has been called unfit for purpose7.

The vast majority of drains used by radiologists are self-retaining pigtail drains, whereas other specialties still prefer straight surgical drains under the assumption that these result in better drainage, notably for evacuation of pleural fluid. Unfortunately, there has been little cross-disciplinary collaboration to bring together the expertise of the chest physician in pleural disease and the device expertise of the interventional radiologist.

This article aims to improve the understanding of different drain types available, individual benefits and drawbacks and most of all a comparison of some of the commoner drain types with regards to inner diameter and flow.

Materials and methods

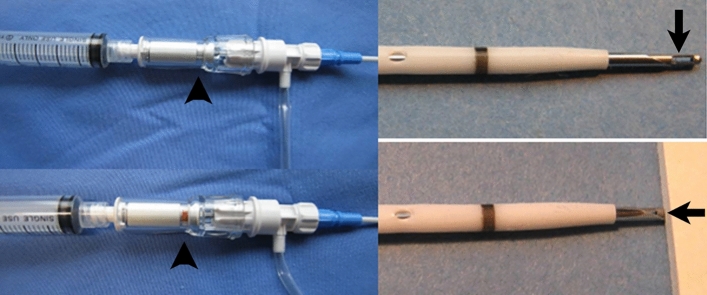

Catheters of four different French sizing; 6Fr., 8Fr., 10Fr. and 12Fr. from eight different manufacturers (models in brackets): Angiotech (Skater), Bard (Navarre), Bioteq (Neo-Hydro), Boston-Scientific (Flexima), Carefusion (SafTcentesis), Cook (Mac-Loc multipurpose catheter), KMC&R Co. Ltd (K-drain), Rocket (Seldinger Drain), were tested to industry standard for their internal lumen diameters and flow rates. Devices included straight chest drains, locked pigtail catheters and unlocked safety catheters (Fig. 1). All catheters can be used with their enclosed trocar for ‘single-stab’ technique.

Fig. 1.

(a) 12Fr. “Seldinger” chest drain. (b) 10Fr. pigtail catheters with locking string (arrow) and plastic and metal stiffener. (c) 8Fr. Safety drain with safety trocar (arrowhead) and integrated side-arm with 3-way tap.

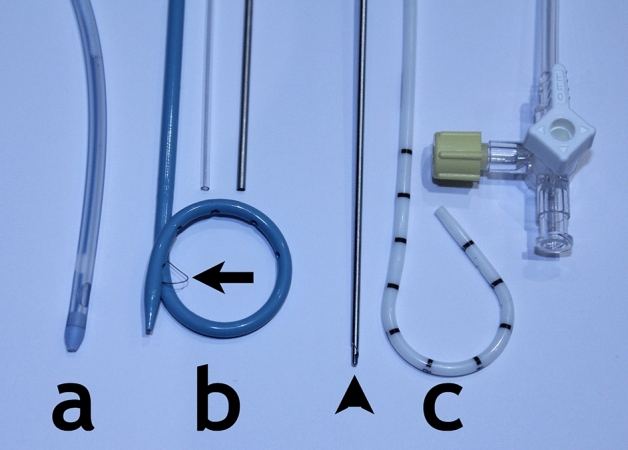

Internal lumen diameters were measured with Meyer calibrated pin gauges, calibrated by a UKAS accredited test house, with an accuracy of ± 5%.Flow rates were determined using the ISO 10,555–1 Standard8. These were calculated volumetrically by using distilled or deionized water (22 ± 5 ºC) to flow through the catheter. Water was filled in a constant-level tank with a Luer taper fitting providing water at a flow rate of 525 ± 25mL in the absence of an attached test catheter (Fig. 2). To ascertain the flow rate, we measured the volume of fluid collected in a calibrated cylinder over a period of 30 s after a steady state was achieved, to the nearest millilitre (mL). This was repeated for three trials for each catheter to obtain the mean flow rate.

Fig. 2.

Set-up for flow measurements with calibrated header tank. Insert: catheter in steady state flow.

This study was performed in an industry standard laboratory, not requiring Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval or patient consent.

Results

Internal diameter and flow rates amongst catheters of the same French sizing varied substantially (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Box and whisker plots to demonstrate the (A) internal diameter and (B) flow rates of catheters of different French sizing.

Table 1.

Internal lumen diameters and flow rates of catheters of different sizes.

| Tube | Internal lumen diameter (mm) (3 s.f) | Flow rate ± 5% (mL/min) (3.sf) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Brand (model) | ||

| 6 Fr (2.0 mm) | Carefusion* (SafTcentesis) | 1.56 | 170 |

| Bard (Navarre) | 1.48 | 115 | |

| Angiotech (Skater) | 1.42 | 98 | |

| Mean | 1.49 | 128 | |

| Standard deviation | ± 0.07 | ± 37.6 | |

| 8 Fr (2.67 mm) | Bard (Navarre) | 2.02 | 206 |

| Bioteq (Neo-hydro) | 1.92 | 210 | |

| Carefusion* (SafTcentesis) | 1.92 | 260 | |

| Boston scientific (Flexima) | 1.74 | 150 | |

| Mean | 1.90 | 207 | |

| Standard deviation | ± 0.10 | ± 55.1 | |

| 10 Fr (3.33 mm) | Bard (Navarre) | 2.54 | 320 |

| Bioteq (Neo-Hydro) | 2.32 | 304 | |

| Boston scientific (Flexima) | 2.42 | 250 | |

| Mean | 2.43 | 291 | |

| Standard deviation | ± 0.11 | ± 36.7 | |

| 12 Fr (4.0 mm) | Bard (Navarre) | 3.14 | 360 |

| Bioteq (Neo-Hydro) | 2.70 | 352 | |

| Boston scientific (Flexima) | 2.52 | 250 | |

| Cook (Mac-Loc multipurpose catheter) | 2.56 | 265 | |

| KMC&R Co. Ltd. (K-Drain) | 2.58 | 290 | |

| Rocket@ (Seldinger Drain) | 2.36 | 302 | |

| Mean | 2.64 | 303 | |

| Standard deviation | ± 0.03 | ± 20.2 | |

All drains locked pigtail catheters except: *Unlocked safety catheter, @"Seldinger" chest drain

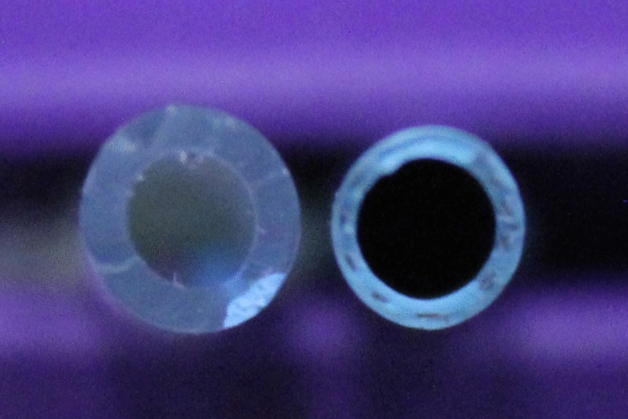

This was most significant in catheters of 8Fr. with a standard deviation of 55.1 mL/min from the mean (range: 150-260mL/min). Due to the differences in drain wall thickness, there was overlap between sizes, whereby the best performing 10Fr. pigtail catheters had a greater internal diameter and flow rate than the 12Fr. catheters, including the “Seldinger” drain (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of wall thickness on catheter lumen. Left: 12 Fr. “Seldinger” drain, Right: 10Fr. pigtail drain.

Note: A caveat to consider with catheters of larger sizes is that connecters, some Luer hubs and notably 3-way taps become limiting factors to flow rates. Therefore, connectors and long extensions negate the perceived benefits of greater flow rates for drains with larger diameters.

Discussion

This manuscript is focused on non-traumatic, “simple” pleural effusions, but applies equally to evacuation of other serous fluid collections such as paracentesis and nephrostomy. The guidelines of the British Thoracic Society suggests that for simple effusions a “small” drain of 10–12 Fr. is adequate, but does not deliver any consideration of the drain characteristics1. Our results show that a nitinol reinforced, thin-walled 10 Fr. pigtail catheter has a larger drainage lumen and therefore delivers a higher flow rate than three of the tested 12 Fr. drains, including two straight “Seldinger drains”. The added value of a thin-walled stent diminishes with increasing drain diameter.

One important other consideration is the drainage speed one would want to obtain. In the vast majority of cases drainage is undertaken by a “start and stop method” where 500-1000mL increments are drained off in one go and the drain is then turned off with a tap to give the patient a break. There are two things wrong with this approach:

The rapid evacuation of larger volumes is the part of the procedure which carries the risk of re-expansion oedema to the lung.

In order to modulate the drainage, the drain needs to be fitted with a tap.

However, the inner bore of many standard 3-way taps is similar to that of a 6–7 Fr. drain, causing a focal restriction in diameter and flow. It therefore does not make much sense to oversize the drain by a large amount. Continuous drainage with a controlled flow rate of 10-15ml/min would be much preferable, but this is currently not standard practice.

Other factors that influence drain choice are the number and size of the side-holes in the catheter and the consistency and viscosity of the fluid to be drained6, in particular, whether it is a uniform solution or contains particulate matter such as white cells (pus), bloods clots or tissue debris. Furthermore, the advantages of a self-retaining pigtail catheter versus the additional need for skin sutures, the dwell time, mechanical stress on the drain and the skill required for removal of the drain need to be considered.

Traditionally, chest drain placement was undertaken with large, trocar-mounted straight surgical catheters. In most cases, currently, drains are inserted by feeding it over a guidewire that has been inserted into the pleural space through a needle, known as the “Seldinger technique”, originally described for using a guide wire to place a catheter into an artery9. Radiologists will almost universally use a pigtail catheter for percutaneous drainage. The name derives from the curled end, which can be “locked” in the curled position by a suture running through the drain itself and exiting through a side hole. These catheters can either be placed mounted on their enclosed trocar (“pig on a stick”) or be fed over a guide wire which has previously been placed through a puncture needle, however the former carries a higher risk of complications. The locked pigtail acts as an internal retaining mechanism to avoid displacement of the catheter.

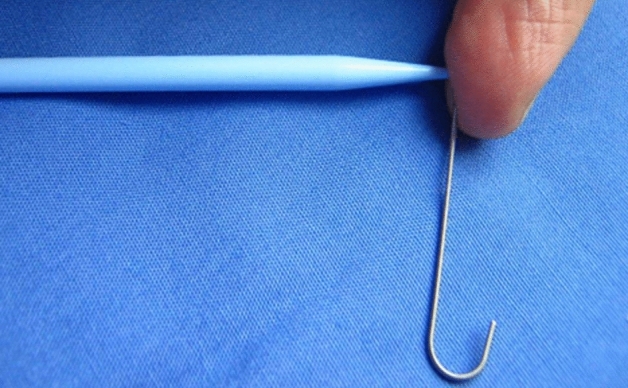

In contrast, most British chest physicians use a “Seldinger drain™”. The “Seldinger drain™”, marketed by two different companies in the UK consists of a puncture needle, a low rigidity guide wire, a very stiff dilator and a straight surgical catheter which has been adapted with an internal tube to fit over the guide wire. The standard size is 12Fr., which—considered by some as “small”—nevertheless requires pre-dilation to insert it through the intercostal space. The original 14Fr. tissue dilator was extremely rigid and would not be deflected from the mediastinum by the guide wire, presenting a risk of injury to the mediastinal structures (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Potential mechanism for injury resulting from the use of a 12Fr. “Seldinger” system. The guidewire is too soft to deflect the 14Fr. dilator around an obstacle.

Previous patient safety alerts have repeatedly outlined severe and fatal complications from the use of “Seldinger drains™”10–13. To address this, the length of the dilators supplied with “Seldinger drains™” have been reduced over recent years to minimise the risk of organ injury, but must still be used with great care.

Our samples also included a 6Fr and 8Fr single-stab safety catheter, which is inserted without guidewire like a large intravenous cannula. These are mounted on a safety trocar with an inner spring-loaded blunt obturator. This protrudes beyond the trocar tip but is pushed back by pressure during insertion through the chest wall (Fig. 6). Once it enters the pleura, the obturator springs forward, protecting the lung from the needle tip and an indicator window confirms intrapleural position. At that point an unlocked pigtail catheter is advanced into the effusion, similar to an intravenous cannula being advanced over the needle into the vein. These are quick, simple and safe to use, notably in pneumothorax. Air in the pleural space renders ultrasound useless and the catheter has to be inserted “blind”, with an increased risk of lung injury. Furthermore, the viscosity of air is about 1/100 of water, therefore a 6 Fr drain is adequate in uncomplicated cases. The speed and simplicity of insertion is a bonus in patients with tension pneumothorax.

Fig. 6.

Pigtail catheter with safety trocar: Without resistance the cutting needle tip is protected by a spring-loaded blunt obturator (arrow) and the indicator (arrowhead) is white. When pushed into tissue the needle tip is exposed and can be advanced, the indicator turns red. Once the pleural/peritoneal space is entered the blunt obturator “clicks” forward again and protects the lung/bowel; the indicator returns to white.

In our test these performed average with regards to inner lumen and flow rate.

There is a paucity in the existing literature with regard to the appropriateness of French sizing in medical devices. Interestingly, a study by Kibriya et al. investigated the uniformity of length and diameter across 200 units of interventional radiology equipment7. They reported variation up to 0.79mm in devices represented by French sizing, however they did find consistency within devices from the same manufacturer (variation up to 0.05 mm)7. This demonstrates variation in the interpretation of French sizing amongst manufacturers, which perhaps would not occur with the strict use of a standardized unit of measurement. There are no previous studies investigating the impact on flow rates subsequent to these variations.

Limitations of this study

The sample size was small and random, but the study was only designed to illustrate the problem of drain sizing, not to test all available devices

Laboratory conditions do not fully reflect clinical scenarios and other factors, such as particulate and complex fluids were not tested

In summary, operators need to understand the intricacies of their devices and match their characteristics to the requirements of the patient. Manufacturers need to be more transparent with the functional parameters of their products to help achieve the best possible outcome.

Summary

What is known: The current standardized measuring system for catheters is the French system, however this only accounts for the outer diameter and does not reflect clinical performance.

What is the question: Do catheters of the same nominal size perform similarly in their ability to drain fluid collections?

What was found: There was large variation in the inner size of catheters of the same nominal outer size and consequently marked differences in performance.

What is the implication for practice now: Operators need to be critical in selecting appropriate devices to achieve best possible outcome. The internal diameter of catheters and their flow rates should be adopted as standard parameters.

Author contributions

Study Design: HUL, DWE, DPdS. Performance of Tests: GDM. Manuscript preparation: KD, HUL. Proofing: GDM, DWE, DPdS. Approval of final version: All.

Funding

This work was funded by Minnova Medical Foundation CIC.

Data availability

The laboratory data are available for scrutiny upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Prof. Hans-Ulrich Laasch.

Competing interests

HUL and DPdS have acted as specialist advisors to Cook Medical. No industry funding or other input was received for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hooper, C., Lee, Y. G. & Maskell, N. Investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax65(Suppl 2), ii4–ii17 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiménez, D. et al. Etiology and prognostic significance of massive pleural effusions. Respir. Med.99(9), 1183–1187 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iserson, K. V. J.-F.-B. Charrière: The man behind the “French” gauge. J. Emerg. Med.5(6), 545–548 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborn, N. K. & Baron, T. H. The history of the “French” gauge. Gastrointest. Endosc.63(3), 461–462 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutera, S. P. & Skalak, R. The history of Poiseuille’s law. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech.25(1), 1–20 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celik, E. et al. Evaluation of viscosities of typical drainage fluids to promote more evidence-based catheter size selection. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-023-49160-8 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kibriya, N., Hall, R., Powell, S., How, T. & McWilliams, R. G. French sizing of medical devices is not fit for purpose. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol.36(4), 1073–1078 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ISO 10555–1:2013 [Internet]. ISO. 2014 [cited 2022Nov13]. https://www.iso.org/standard/54884.html.

- 9.Seldinger, S. I. Catheter replacement of the needle in percutaneous arteriography; a new technique. Acta Radiologica39(5), 368–376. 10.3109/00016925309136722.PMID13057644 (1953). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooper, C. & Maskell, N. British Thoracic Society national pleural procedures audit 2010. Thorax66(7), 636–637 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akram, A. R. & Hartung, T. K. Intercostal chest drains: A wake-up call from the National Patient Safety Agency rapid response report. J. R. Coll. Phys. Edinb.39(2), 117–120 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maskell, N. A., Medford, A. & Gleeson, F. V. Seldinger chest drain insertion: simpler but not necessarily safer. Thorax65(1), 5–6 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies, H. E., Merchant, S. & McGOWN, A. A study of the complications of small bore ‘Seldinger’ intercostal chest drains. Respirology13(4), 603–607 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The laboratory data are available for scrutiny upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Prof. Hans-Ulrich Laasch.