Abstract

Dielectric capacitors are vital for modern power and electronic systems, and accurate assessment of their dielectric properties is paramount. However, in many prevailing reports, the fringing effect near electrodes and parasitic capacitance in the test circuit were often neglected, leading to overrated dielectric performances. Here, the serious impacts of the fringing effect and parasitic capacitance are investigated both experimentally and theoretically on different dielectrics including Al2O3, SrTiO3, etc. The deviations are more critical for the measurements of capacitors using asymmetric electrodes with different areas and for dielectrics with a lower dielectric constant, and differences tested in silicone oil and air environments should be noticed. A method to calibrate the parasitic capacitance of the test circuit is also raised for ensuring the accuracy of measured dielectric performances. Enlarging the electrode diameter and/or thinning the sample can reduce the above deviations, and thus a general standard of setting capacitor configurations is proposed for the measurement validity. Our study clearly demonstrates that it is necessary to mitigate the fringing effect and subtract the parasitic capacitance to solve the problem on overrated dielectric performances, which is very important for the development of the dielectric research in a healthy and orderly way.

Subject terms: Energy storage, Ferroelectrics and multiferroics

The authors find that the dielectric performance of capacitors will be significantly overestimated due to the influences of fringing effect and parasitic capacitance. Methods to solve the problem are proposed to ensure measurement validity.

Introduction

Dielectric materials based on ceramics or polymers are insulators that can be polarized by an electric field1–3. This capability is essential for capacitors with broad applications, ranging from consumer electronics to renewable energy systems and electric vehicles4,5. In the quest to improve energy density of capacitors, research over the past two decades has focused on enhancing the dielectric properties of various materials including linear dielectrics, ferroelectrics, relaxor ferroelectric, and antiferroelectric materials, etc6–10. Unfortunately, in some publications, the claimed advance may be related to factitious factors, and their validity is questionable. For example, it is well known that the breakdown field of a capacitor is inversely related to the electrode area, as shown in Fig. 1a, b7,11. This is often contributed to the less defects covered by a smaller electrode. In fact, a small number of free carriers in a smaller electrode flowing through the weak point will also reduce the possibility of breakdown. Recently, small electrodes have often been used for investigating energy storage performances, and the breakdown field and the corresponding energy density show unpractical high values (see Fig. 1c, d)12,13. More seriously, unsuitable experiment setup can even lead to incorrect evaluation of dielectric constant, one of the most important figure-of-merit, which can significantly affect the energy storage density of capacitors.

Fig. 1. Breakdown strength and energy density of samples with different electrode diameters.

Breakdown strength as a function of electrode diameter for a the pristine polyetherimide (PEI), PEI/ITIC, and PEI/boron nitride nanosheets (BNNS) films11 and b the PEI and PEI-0.2 wt% phosphotungstic acid subnanosheets (PWNS) films7 measured at 200 °C. c Recoverable energy density with associated efficiency under 2 MV m−1 at room temperature (RT) for ferroelectric BaTiO3 ceramics with various d/t13. d and t refer to the electrode diameter and sample thickness, respectively. d Energy storage performance of 1.0 wt% calcium niobate@metal-organic framework/polyimide (CNO@MOF/PI) with different electrode diameters at 150 °C12. Images and corresponding data are adapted from ref. 7,11–13 with permission.

A parallel-plate capacitor configuration with the dielectric material sandwiched by top and bottom conducting electrodes is typically fabricated for the measurement of the dielectric properties (see Supplementary Fig. S1). The capacitance (C) is tested to calculate the dielectric constant (εr) based on the following equation for ideal parallel-plate capacitors:

| 1 |

where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, A is the area of the electrode, and t is the thickness of the dielectric sample. One of the significant challenges in accurately measuring dielectric properties is the impact of fringing effect14,15, which can result in a bigger measured capacitance than the expected value for a given electrode area and thus overestimate the measured dielectric constant. This is because the fringing electric field will stray from the edge of the electrode to the surrounding atmosphere and the dielectric outside the electrode coverage area, and thus lead to an effectively larger area than actual electrode area. This issue is particularly pronounced in configurations where the ratio of electrode diameter (d) to sample thickness (t) is small16. However, in the hot research field of dielectric materials, this effect has received little prior attention, and many publications reported their “exciting” values of dielectric constant and energy density which are actually overrated17–21.

Another critical issue in dielectric measurements is the presence of parasitic capacitance from equipment and test circuits. When the measured sample has low capacitance, parasitic capacitance in parallel with the sample can even lead to more significant measurement deviation than the fringing effect. The parasitic capacitance should be different for different equipment, and it is especially significant for ferroelectric testers which are widely used for evaluating capacitive energy density and charge-discharge efficiency based on the measurement of electric displacement versus electric field. An overlook of parasitic capacitance will cause an overestimation of the dielectric constant and capacitive energy density. For example, in a report on the polyimide-poly(amic acid) copolymer-based composite film which is a linear dielectric, the dielectric constant from electric displacement-electric field (D-E) tested by a ferroelectric tester is ~63% larger than that tested by an impedance analyzer with a very small parasitic capacitance (see Supplementary Fig. S2)22. Understanding and mitigating fringing effect and parasitic capacitance are crucial for accurate dielectric characterization and the development of dielectric materials.

In this work, an in-depth exploration into the impacts of the fringing effect and parasitic capacitance on dielectric measurements was conducted by varying the capacitor configurations, the sample or surrounding dielectric constant, and the asymmetry degree of top and bottom electrode areas. General rules to minimize the fringing and parasitic capacitance effects were proposed. These insights are valuable not only for the accurate measurement of dielectric properties but also for the design and development of advanced dielectric materials with validated energy storage capabilities.

Results and discussion

Fringing effect in dielectric measurements

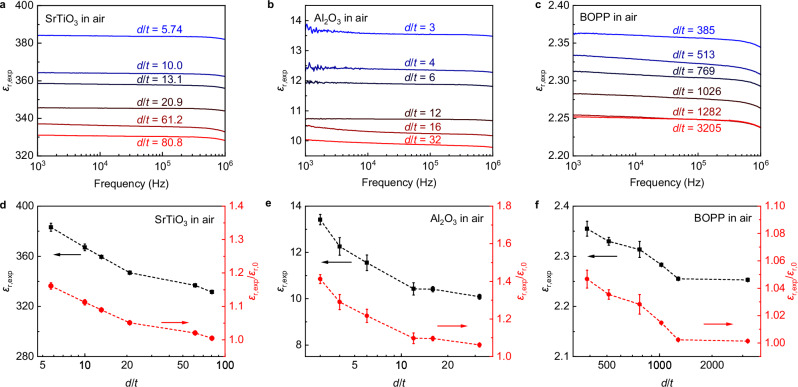

The ratio of the electrode diameter (d) against the sample thickness (t), d/t, can be regarded as a suitable parameter for scaling the geometric characteristics of the tested sample. The capacitances of SrTiO3, Al2O3, and biaxially oriented polypropylene (BOPP) with different d/t ratios were measured by an impedance analyzer, and the dielectric constants were calculated according to Eq. (1). Figure 2a–c shows the frequency dependences of the measured (or apparent) dielectric constants (εr,exp) of SrTiO323–25, Al2O326,27, and BOPP28 samples with various d/t ratios. The dielectric constant spectra of these samples show excellent frequency stability. As summarized in Fig. 2d–f, with increasing the ratio of d/t, all samples exhibit a decreasing trend in εr,exp at 1 kHz. Taking Al2O3 as an example, as d/t increases from 3 to 24, εr,exp decreases from 13.4 to 10.1, as shown in Fig. 2e. The ratio of εr,exp/εr,0 can be used to evaluate the deviation of tested results from the intrinsic dielectric constant of εr,0, and a value of εr,exp/εr,0 closer to 1 indicates a smaller deviation. Here, εr,0 is 330, 9.5, and 2.25 for SrTiO3, Al2O3, and BOPP, respectively. In the range of d/t from 3 to 24, the ratio of εr,exp/εr,0 is consistently greater than 1, demonstrating the overestimation of dielectric constant. Moreover, with increasing d/t ratio, the value of εr,exp/εr,0 decreases gradually from 1.41 to 1.06. Similar trend is also obtained for SrTiO3 and BOPP samples, as shown in Fig. 2d, f, respectively. This indicates that the overestimation of the dielectric constant can be mitigated by increasing d/t ratio.

Fig. 2. Measured dielectric constants for samples with different d/t ratios.

Dielectric spectra, measured dielectric constants (εr,exp) at 1 kHz and the ratios of εr,exp/εr,0 for (a, d) SrTiO3, (b, e) Al2O3 and (c, f) BOPP with different d/t ratios. Here, the intrinsic dielectric constants εr,0 are 330 for SrTiO3, 9.5 for Al2O3, and 2.25 for BOPP, respectively. Error bars represent the standard deviations.

Furthermore, asymmetric top and bottom electrodes with different diameters (suppose dtop < dbot, see Supplementary Fig. S1b) were frequently employed in dielectric measurements29,30. In this configuration, dtop (<dbot) is the electrode diameter (d) for calculating dielectric constant from measured capacitance. Figure 3a shows the measured dielectric constant of Al2O3 samples with dtop = 3 mm and dbot from 3 to 8 mm. For dtop/t = 12 (dtop = 3 mm, t = 0.25 mm), εr,exp rises from 11.4 to 13.5 with increasing dbot from 3 to 8 mm, and the εr,exp/εr,0 ratio increases from 1.20 to 1.42, as shown in Fig. 3b. This phenomenon can be dilated for a smaller dtop/t ratio of 3 with asymmetric electrodes. It implies that samples with asymmetrical electrodes exhibit greater deviations in tested dielectric constant compared to samples with symmetrical electrodes.

Fig. 3. Measured dielectric constants for Al2O3 samples with asymmetric electrodes in air and in silicone oil.

a Dielectric spectra of Al2O3 samples with a fixed top electrode diameter (dtop) of 3 mm and various bottom electrode diameters (dbot) from 3 to 8 mm. b Comparison of εr,exp for Al2O3 samples with asymmetric and symmetric electrodes at different d/t ratios. c Dielectric spectra of Al2O3 samples in silicone oil with various d/t ratios. d Comparison of εr,exp for Al2O3 samples with different d/t ratios in air and silicone oil. Error bars represent the standard deviations.

Beside testing capacitors in air, samples are often immersed in highly insulating silicone oil for dielectric measurements under high electric fields. Figure 3c displays the frequency dependent dielectric constant of Al2O3 ceramic measured in silicone oil. As the d/t ratio increases from 3 to 32, the value of εr,exp decreases from 14.9 to 10.6, and the εr,exp/εr,0 ratio decreases from 1.56 to 1.16, showing larger deviations than those measured in air, as depicted in Fig. 3d. This suggests that conducting dielectric measurements in silicone oil can exacerbate overestimations of the dielectric constant and capacitive energy density. Using large electrode diameter and/or reducing sample thickness to increase d/t ratio are critically important to diminish the errors.

FEM simulations on the fringing effect

To reveal the underlying mechanism of fringing effect on the dielectric measurements, finite element method (FEM) simulations were carried out. Figure 4a, b displays the electric field distributions on the surface and cross-section, respectively, for Al2O3 samples with symmetric electrodes in air. The electric field is relatively uniform within the sample area covered by the electrode, but it becomes highly concentrated at the edge of electrode. This higher local electric field can increase the electric displacement, resulting in a bigger apparent capacitance. More importantly, fringing electric fields are also present in the sample outside the electrode coverage area as well as in the air surroundings, which will result in an effectively larger area and increase the measured capacitance. As shown in Fig. 4c, the electric field in the region covered by the electrode in the center of the sample (L2) is almost unchanged around the given electric field of 5 MV m−1, while a significant peak appears at the edge of the electrodes on the sample surface (L1). The electric field in the area not covered by the electrode decays with increasing horizontal distance from the edge of the electrode, and even in the air surroundings, low fringing electric fields still exist. These fringing electric fields will contribute to the total electrostatic energy and total capacitance of the system, and the proportion of its contribution to the total capacitance decreases with increasing d/t. The equivalent dielectric constant εr, FEM can be calculated by Eqs. 2–4 discussed in the method section. As summarized in Fig. 4d, when the d/t ratio increases from 2 to 40, the εr,FEM/εr,0 ratio decreases from 1.62 to 1.04, which is in good agreement with experimental values. Consistent with the tendency obtained in experiments, using a larger electrode diameter or reducing sample thickness helps to achieve a more accurate dielectric constant. It is worth mentioning that sufficient surrounding sphere diameter and distance between the electrode and sample edge are utilized in FEM simulations, so that the simulated results will almost not be affected by the variations of these two factors, as shown in Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4.

Fig. 4. FEM simulations on Al2O3 capacitors with different d/t ratios.

a Electric field distribution on the surface of Al2O3 sample. b Electric field distribution on cross-section of Al2O3 with different d/t ratios in air. Dashed lines represent the edge position of the electrode. c Electric field distributions along the L1 and L2 in x-direction across the surface and center of the cross-section of Al2O3 in air, respectively. Light red, gray, and blue areas refer to the sample under electrode coverage, the sample outside electrode converge and surroundings, respectively. d Comparison between the εr,FEM/εr,0 (line) and εr,exp/εr,0 (dots) ratios of Al2O3 capacitors with various d/t ratios. Error bars represent the standard deviations.

The deviation in dielectric measurements is also closely linked to the dielectric constant of samples. Figure 5a illustrates the electric field distribution along the x-direction across the center of the cross-section along the x-direction with d/t = 6 for the dielectrics with different permittivities. As the permittivity decreases from 1000 to 1, there is a significant enhancement in the electric field within samples beyond the electrode coverage area (gray area in Fig. 5a), leading to an increase of the εr,FEM/εr,0 ratio from 1.16 to 1.50, as shown in Fig. 5b. This implies that the measurement deviation induced by fringing effect will be more prominent in samples with low dielectric constants.

Fig. 5. FEM simulations on samples with different dielectric constants, with symmetric and asymmetric electrodes and in surroundings with different dielectric constants.

a Electric field distributions along the x-direction across the center of the cross-section of samples with different εr,0 in air, for the d/t = 6. b εr,FEM/εr,0 versus εr,0 of sample. c Electric field distributions along the x-direction across the center of the cross-section of Al2O3 in air with different dbot, for the dtop/t = 6. d εr,FEM/εr,0 versus dbot of sample. e Electric field distributions along the x-direction across the center of the cross-section of Al2O3 with d/t = 6 in different surroundings. f εr,FEM/εr,0 versus εr,surr of surroundings.

To further explore the impact of asymmetrical electrode diameters on dielectric measurements, FEM simulation was carried out. As shown in Fig. 5c, when the top electrode diameter (dtop) is fixed at 3 mm, increasing the bottom electrode diameter (dbot) from 3 to 6 mm results in a significant increase in the fringing field. When dtop/t = 6, with the dbot rising from 3 to 6 mm, the value of εr,FEM/εr,0 increases from 1.19 to 1.38, see Fig. 5d. The enhanced asymmetry raises the fringing electric field effect, which will lead to a higher measured dielectric constant.

Figure 5e illustrates FEM simulated electric field distributions for a dielectric tested in surroundings with different dielectric constants (εr,surr). One can see that the electric field outside the electrode coverage area in Al2O3 (d/t = 6) increases slightly with the rise of surrounding dielectric constant, while that in the surroundings remains almost unchanged. With increasing the surrounding dielectric constant from 1 to 3, the εr,FEM/εr,0 ratio increases from 1.20 to 1.27, as shown in Fig. 5f. This indicates that conducting dielectric measurements in silicone oil (dielectric constant of ~2.88) rather than air will result in a higher measured dielectric constant. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 5b, d, f, increasing the d/t ratio is beneficial for reducing the measurement deviation.

It is necessary to lay down a standard of suitable d/t for limiting deviations of dielectric constant within 5%, i.e., with εr,FEM/εr,0 ratio smaller than 1.05. In Fig. 6, fringing effect induced deviations for samples with varying dielectric constant under both symmetric and asymmetric electrode configurations in air and silicone oil are simulated. For Al2O3 samples with symmetric electrodes, a d/t > 28 can reduce the measuring deviation to be <5%, as shown in Fig. 6a. For example, for Al2O3 samples with a thickness of 0.2 mm, the electrode diameter must exceed 5.6 mm for <5% deviation control. When testing with asymmetrical electrodes in silicone oil, a much bigger d/t > 83 is required to reduce the measuring deviation to be <5% (see Fig. 6d). Furthermore, for samples with lower dielectric constants like those found in many polymer dielectrics such as BOPP (εr,0 ~2.25)25, cyclic olefin copolymer (εr,0 ~2.4)31, and polyimide (εr,0 ~3.0)25, larger d/t values are necessary to ensure the desired measurement validity.

Fig. 6. Standard for test accuracy control according to FEM simulations.

εr,FEM/εr,0 for samples with different εr,0 and d/t ratios using a symmetric electrodes in air, b symmetric electrodes in silicone oil, c asymmetric electrodes with dtop/dbot ~ 0.3 in air and d asymmetric electrodes with dtop/dbot ~ 0.3 in silicone oil. The black and yellow solid lines represent the 5% and 1% contour lines, respectively. For the FEM simulation related to asymmetric electrodes, enough asymmetry with dtop/dbot ~ 0.3 is used so that the asymmetry-induced error has reached saturation region.

Fringing effect and parasitic capacitance in dielectric energy storage

In addition to the fringing effect, the parasitic capacitance coming from the equipment and circuits cannot be ignored. For an impedance analyzer after careful fixture compensation following the instrument instructions, the effect of parasitic capacitance is negligible. While for a ferroelectric analyzer which is widely used for D-E measurements for calculation of energy storage density and charge-discharge efficiency, the parasitic capacitance can be calibrated by standard capacitors, and a ferroelectric analyzer generally has a parasitic capacitance of 2–40 pF that depends on the test circuit setup (see Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6). This parasitic capacitance is in parallel with the sample capacitance, and thus serious overestimations of measured capacitance and energy density will be observed.

Figure 7a, b illustrates the experimental D-E curves of a linear dielectric Al2O3 in silicone oil before and after subtracting the parasitic capacitance (~2 pF as calibrated in our testing circumstance). Al2O3 samples with different capacitances by changing d and/or t were used for testing D-E curves. After subtracting the parasitic capacitance, the electric displacement under the same electric field is significantly reduced towards its actual value. Suppose the capacitance is even smaller than the parasitic capacitance. In that case, the measured electric displacement will be irrationally higher than the actual value due to the influence of parasitic capacitance, and thus is a wrong result. As summarized in Fig. 7c, for an Al2O3 sample (d ~3 mm, t ~1 mm) with capacitance ~0.86 pF (tested by an impedance analyzer) even smaller than the parasitic capacitance (~2 pF) of the measurement system of ferroelectric tester, the energy density calculated from D-E curves reaches up to ~7.3 mJ cm−3 before subtracting the parasitic capacitance, which leads to an unbelievable overrated energy density ~560% higher than the intrinsic value of ~1.1 mJ cm−3 (Ue,0 = 0.5ε0εr,0E2, where Ue,0 refers the intrinsic value, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S7). After subtracting parasitic capacitance, the calculated energy density of 3.8 mJ cm−3 is still much larger than the intrinsic value of 1.1 mJ cm−3 owing to the fringing effect. When the Al2O3 sample (d ~6 mm, t ~0.25 mm) capacitance tested by impedance analyzer reaches 10.4 pF, the energy density before and after subtracting the parasitic capacitance are 1.4 mJ cm−3 and 1.2 mJ cm−3, respectively. This is because the contribution of parasitic capacitance to the total decreases with increasing the dielectric capacitance.

Fig. 7. Effect of parasitic capacitance on electric displacement-electric field curves.

Experimental electric displacement-electric field (D-E) curves before and after subtracting parasitic capacitance (Cpara) and the measured energy density of (a–c) Al2O3 and (d–f) P(VDF-TrFE-CTFE) with different capacitances tested in silicone oil.

Besides the linear dielectrics discussed above, relaxor ferroelectrics as nonlinear dielectrics have been extensively studied as capacitive energy storage materials because of their high dielectric constant and slim D-E curves. Similar to the linear dielectrics, a larger d/t is necessary to obtain more accurate dielectric constant for a typical relaxor ferroelectric P(VDF-TrFE-CTFE), as shown in Supplementary Figs. S8–S12. For P(VDF-TrFE-CTFE) with d/t ranging from 27 to 73, the difference between the energy densities before and after subtracting parasitic capacitance is relatively small, as shown in Fig. 7d–f. This is due to that the capacitance of P(VDF-TrFE-CTFE) sample (~22–146 pF, tested by an impedance analyzer) is much higher than that of parasitic capacitance.

These findings clearly indicate that for samples with a small d/t ratio or a low capacitance, the parasitic capacitance can lead to additional measurement deviations even beyond the fringing effect. Hence, during dielectric testing, the following two aspects are prioritized: (i) the measured sample should have high enough capacitance for conducting D-E curve tests, and (ii) calibrating the parasitic capacitance in advance is always necessary. In addition, it is worth mentioning that a poorly designed experimental setup could also overmeasure the charge-discharge efficiency, even >100%, and contradicting the laws of physics, as observed in certain Sawyer-Tower circuit measurements.

In summary, both experimental results and FEM simulations reveal that the measured dielectric constant increases with decreasing d/t ratios. The electric field distribution analysis confirms that the fringing electric fields outside the electrode area contribute to the measured capacitance. The measurement deviations are more pronounced in dielectrics with lower permittivities, by using asymmetric electrodes with different areas, or testing in silicone oil rather than in air. Furthermore, the parasitic effect from measuring system should be carefully subtracted. A general standard of selecting d/t ratio and a method of calibrating parastic capacitance were raised for achieving validated dielectric performance, which is important for the development of research on capacitive energy storage of not only linear dielectrics but also (relaxor) ferroelectrics as well as antiferroelectric materials.

Methods

Materials and preparation

BOPP, Al2O3, SrTiO3, and P(VDF-TrFE-CTFE) were studied due to their contrasting dielectric constants. BOPP films with a thickness of 7.8 µm were provided by Anhui Tongfeng Electronics. Al2O3 ceramic sheets and SrTiO3 single crystal sheets were purchased from Jingwei Special Ceramics Co., LTD and Hefei Kejing Material Technology Co., LTD, respectively. The thickness of Al2O3 sheets ranges from 0.25 to 1.0 mm, and that of SrTiO3 sheets ranges from 0.1 to 0.5 mm. P(VDF-TrFE-CTFE) powders were purchased from Arkema, and corresponding films (thickness of ~110 µm) were prepared through solution casting. The P(VDF-TrFE-CTFE) films were annealed at 110 °C to enhance its relaxor ferroelectricity. Circular Au electrodes with different diameters of 3–8 mm were deposited on two sides of the specimen for electrical characterizations.

Characterization

The dielectric spectra were tested by a precision impedance analyzer (Agilent 4294 A LCR meter) under an AC voltage of 0.5 V. Electric displacement-electric field curves were measured using a Radiant Technologies Precision Premier II equipped with a TREK MODEL 609B high-voltage amplifier. The voltage waveform for the electric displacement-electric field measurements was a triangular unipolar pulse with a period of 10 ms.

Finite element method simulation

The FEM simulation was carried out using Comsol Multiphysics software. A 3D capacitor model based on a cylindrical dielectric with thin circular disk electrodes attached to its top and bottom surfaces was established to simulate the measured samples (see Supplementary Fig. S1). d and t refer to the diameter of disk electrode and the thickness of dielectric sample, respectively. In the FEM simulations, the surrounding sphere diameter was set to 40 mm, and the sample diameter was set to 10 mm. The distance between the electrode and the edge of the sample is maintained at 1 mm or more, which is significantly greater than the thickness of the sample. The tetrahedral elements with edge lengths of 20 μm were used to mesh the FEM models, ensuring a sufficient simulation accuracy.

The equivalent capacitance of the 3D model can be calculated from the global electrostatic energy UFEM using:

| 2 |

where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, and εr (x, y, z) and E (x, y, z) are the relative dielectric constant and the electric field locating at (x, y, z) in the model, respectively32. For an isotropic linear dielectric, εr can be considered as a scalar independent of the electric field. The equivalent capacitance CFEM was calculated by:

| 3 |

where V is the applied voltage between the top and bottom electrodes to set a given electric field (V/t) of 5 MV m−1. The equivalent dielectric constant εr,FEM can be calculated by:

| 4 |

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A2066 (X.G.L.), 52125204 (Y.W.Y.), 52422209 (S.C.S.), and U24A20203 (X.G.L.)), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFB3807604 (X.G.L.), 2022YFB3807602 (S.C.S.) and 2024YFA1208601 (Y.W.Y.)); this work was partially carried out at the USTC Center for Micro and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication as well as the Instruments Center for Physical Science, USTC. The calculations in this paper were performed on the supercomputing system at the Supercomputing Center of the University of Science and Technology of China.

Author contributions

Song Ding: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft. Jiangheng Jia: Investigation, Formal analysis. Bo Xu: Investigation, Formal analysis. Zhizhan Dai: Formal analysis. Yiwei Wang: Formal analysis. Shengchun Shen: Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing. Yuewei Yin: Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing. Xiaoguang Li: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Haixue Yan and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All the data supporting the findings of this study are provided within the article and the Supplementary Information file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Song Ding, Jiangheng Jia, Bo Xu.

Contributor Information

Shengchun Shen, Email: scshen@ustc.edu.cn.

Yuewei Yin, Email: yyw@ustc.edu.cn.

Xiaoguang Li, Email: lixg@ustc.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-55855-5.

References

- 1.Su, R. et al. Dielectric screening in perovskite photovoltaics. Nat. Commun.12, 2479 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li, T. R. et al. A native oxide high-κ gate dielectric for two-dimensional electronics. Nat. Electron.3, 473–478 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu, Y. S. et al. Scalable integration of hybrid high-κ dielectric materials on two-dimensional semiconductors. Nat. Mater.22, 1078–1084 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong, Z., Mansouri, S. A., Huang, S., Rezaee Jordehi, A. & Tostado-Véliz, M. The role of smart communities integrated with renewable energy resources, smart homes and electric vehicles in providing ancillary services: a tri-stage optimization mechanism. Appl. Energy351, 121897 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsharif, A., Tan, C. W., Ayop, R., Dobi, A. & Lau, K. Y. A comprehensive review of energy management strategy in vehicle-to-grid technology integrated with renewable energy sources. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess.47, 101439 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan, H. et al. Ultrahigh energy storage in superparaelectric relaxor ferroelectrics. Science374, 100–104 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang, M. Z. et al. Roll-to-roll fabricated polymer composites filled with subnanosheets exhibiting high energy density and cyclic stability at 200 °C. Nat. Energy9, 143–153 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang, J. et al. Ultrahigh energy storage density in lead-free relaxor antiferroelectric ceramics via domain engineering. Energy Storage Mater.43, 383–390 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang, Z. B., Wang, D. H., Litt, M. H., Tan, L. & Zhu, L. High‐temperature and high‐energy‐density dipolar glass polymers based on sulfonylated poly(2,6‐dimethyl‐1,4‐phenylene oxide). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.57, 1528–1531 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva, J. P. B. et al. High‐performance ferroelectric–dielectric multilayered thin films for energy storage capacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater.29, 1807196 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan, C. et al. Polymer/molecular semiconductor all-organic composites for high-temperature dielectric energy storage. Nat. Commun.11, 3919 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, X. X. et al. Atomic‐level matching metal‐ion organic hybrid interface to enhance energy storage of polymer‐based composite dielectrics. Adv. Mater.36, 2402239 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll, E. L., Killeen, J. H., Feteira, A., Dean, J. S. & Sinclair, D. C. Influence of electrode contact arrangements on polarisation-electric field measurements of ferroelectric ceramics: a case study of BaTiO3. J. Materiomics 100939 (2024).

- 14.Wang, Y. L. & Chung, D. D. L. Effect of the fringing electric field on the apparent electric permittivity of cement-based materials. Compos. Part B Eng.126, 192–201 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathur, D., Bhatnagar, S. K. & Sahula, V. Nondestructive method for measuring dielectric constant of sheet materials. In Proc.TENCON 2011–2011IEEE Region 10 Conference 1105–1109 (IEEE, Bali, Indonesia, 2011).

- 16.Kidner, N. J., Homrighaus, Z. J., Mason, T. O. & Garboczi, E. J. Modeling interdigital electrode structures for the dielectric characterization of electroceramic thin films. Thin Solid Films496, 539–545 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haydoura, M. et al. Perovskite (Sr2Ta2O7)100−x(La2Ti2O7)x ceramics: from dielectric characterization to dielectric resonator antenna applications. J. Alloy. Compd.872, 159728 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaman, A., Uddin, S., Mehboob, N. & Ali, A. Structural investigation and improvement of microwave dielectric properties in Ca(HfxTi1−x)O3 ceramics. Phys. Scr.96, 025701 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goulas, A. et al. Microstructure and microwave dielectric properties of 3D printed low loss Bi2Mo2O9 ceramics for LTCC applications. Appl. Mater. Today21, 100862 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortés, J. A., Moreno, H., Orrego, S., Bezzon, V. D. N. & Ramírez, M. A. Dielectric and non-ohmic analysis of Sr2+ influences on CaCu3Ti4O12-based ceramic composites. Mater. Res. Bull.134, 111071 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanchevskii, O. Z., V’yunov, O. I., Belous, A. G. & Kovalenko, L. L. Dielectric properties of CaCu3Ti4O12 ceramics doped with aluminium and fluorine. J. Alloy. Compd.874, 159861 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai, Z. Z. et al. Scalable polyimide‐poly(amic acid) copolymer based nanocomposites for high‐temperature capacitive energy storage. Adv. Mater.34, 2101976 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takashima, H., Wang, R., Kasai, N., Shoji, A. & Itoh, M. Preparation of parallel capacitor of epitaxial SrTiO3 film with a single-crystal-like behavior. Appl. Phys. Lett.83, 2883–2885 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinbara, H., Harigai, T., Kakemoto, H., Wada, S. & Tsurumi, T. Temperature dependence of dielectric permittivity of perovskite-type artificial superlattices. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control54, 2541–2547 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu, C. et al. Flexible temperature‐invariant polymer dielectrics with large bandgap. Adv. Mater.32, 2000499 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen, L.-Y. Temperature dependent dielectric properties of polycrystalline aluminum oxide substrates with various impurities. In Proc.20078th International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology 1–6 (IEEE, Shanghai, China, 2007).

- 27.Thakur, Y. et al. Enhancement of the dielectric response in polymer nanocomposites with low dielectric constant fillers. Nanoscale9, 10992–10997 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng, W. W. et al. Temperature resistant amorphous polyimides with high intrinsic permittivity for electronic applications. Chem. Eng. J.436, 135060 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein, A. Interface properties of dielectric oxides. J. Am. Ceram. Soc.99, 369–387 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, M. & Deng, C. Y. Orientation and electrode configuration dependence on ferroelectric, dielectric properties of BaTiO3 thin films. Ceram. Int.45, 22716–22722 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bao, Z. W. et al. Significantly enhanced high-temperature capacitive energy storage in cyclic olefin copolymer dielectric films via ultraviolet irradiation. Mater. Horiz.10, 2120–2127 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurimoto, M. et al. Finite element modeling of effective permittivity in nanoporous epoxy composite filled with hollow nanosilica. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul.26, 1434–1440 (2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting the findings of this study are provided within the article and the Supplementary Information file. Source data are provided with this paper.