Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a gas signaling molecule with versatile bioactivities; however, its exploitation for disease treatment appears challenging. This study describes the design and characterization of a novel type of H2S donor–drug conjugate (DDC) based on the thio-ProTide scaffold, an evolution of the ProTide strategy successfully used in drug discovery. The new H2S DDCs achieved hepatic co-delivery of H2S and an anti-fibrotic drug candidate named hydronidone, which synergistically attenuated liver injury and resulted in more sufficient intracellular drug exposure. The potent hepatoprotective effects were also attributed to the H2S-mediated multipronged intervention in lipid peroxidation both at the whole cellular and lysosomal levels. Lysosomal H2S accumulation and H2S DDC activation were facilitated by the hydrolysis through the specific lysosomal hydrolase, representing a distinct mechanism for lysosomal targeting independent of the classical basic moieties. These findings provided a novel pattern for the design of optimally therapeutic H2S DDC and organelle-targeting functional molecules.

Key words: ProTide prodrug, Hydrogen sulfide donor, Drug conjugate, Cellular pharmacokinetics, Liver fibrosis, Lipid peroxidation, Lysosomal targeting, Prodrug activation

Graphical abstract

The thio-ProTides, as novel H2S donor–drug conjugates, enabled the co-delivery of H2S with pharmacologically active molecules. Their lysosomal H2S accumulation potentially enhanced the mitigation of hepatic lipotoxicity and fibrosis.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is among the three musketeers of gas signaling molecules, along with nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO), due to its diverse and rich physiological and fascinating pharmacological activities1, 2, 3, including pivotal antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic functions through a myriad of biological signaling pathways4,5. More recently, the involvement of H2S in the post-translational modification of protein sulfhydryl groups has also been revealed as a second important function6. The diverse biological activities are the basis for the conviction that H2S is a potential candidate for the treatment of diseases with complex mechanisms7,8. Considerable progress has been made in developing H2S donors with multiple chemical innovations that can release H2S under different conditions9, 10, 11, 12. However, assigning greater therapeutic value to H2S donors remains pending. To achieve this goal, one feasible and clinically validated approach to achieve is to design H2S donor–drug conjugates (DDCs), like their clinically successful counterpart NO DDCs13.

H2S DDCs could achieve the co-release of H2S with certain drugs through innovative chemical structure design. H2S is believed to counteract the side effects of drug molecules or synergize with functional molecules to enhance biological activity. Recent advances in this field have been well reviewed14,15. Carbonyl sulfide (COS)-based DDCs are one of the few strategies currently available to balance the controlled release of H2S with the on-demand drug delivery (Fig. 1A). The COS is generated with the drug under specific conditions and then converted to H2S via carbonic anhydrase catalysis. Anetholedithiolethione (ADT) is a classic class of H2S donors that slowly release H2S in the presence of microsomal monooxygenases (Fig. 1A). Compared to COS-based DDCs, controllable release of H2S at specific sites and rates is more challenging with ADT-based DDCs because the H2S release from ADT does not depend on drug coupling or linker cleavage (decoupling). Nevertheless, more H2S DDCs with novel and diverse structures are still needed to offer more possibilities to assess the therapeutic value of H2S.

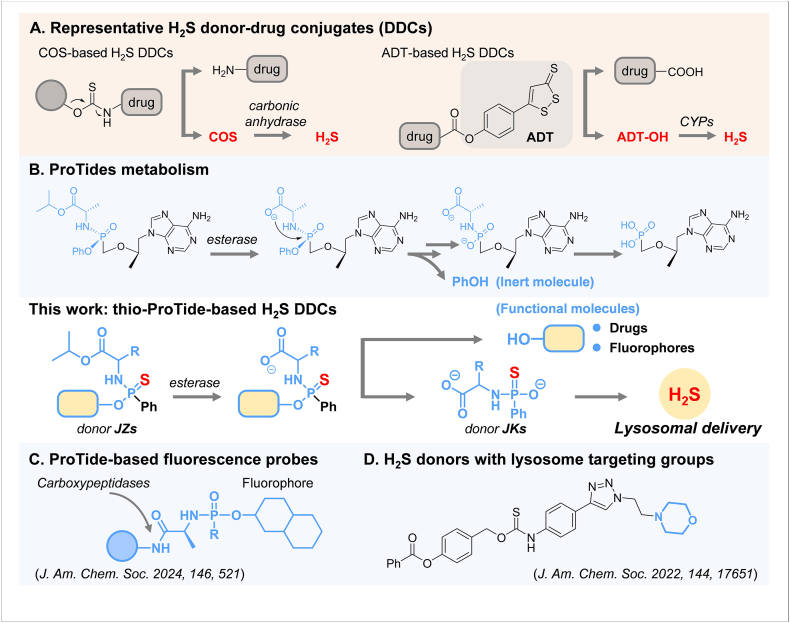

Figure 1.

Our thio-ProTide-based H2S donor–drug conjugates (DDCs) is structurally distinct from conventional DCCs (A) or other ProTide-based molecules (B, C), providing H2S without lysosomal targeting groups (D).

We believe the ProTide prodrug is a superior approach for designing H2S DDCs. Phosphoramidate prodrugs based on ProTide chemistry were pioneered by Prof. Chris McGuigan (Cardiff, UK) and have achieved great success in the clinic16, 17, 18. The blockbuster drugs sofosbuvir19 and tenofovir alafenamide20 (Fig. 1B) using the ProTide strategy have demonstrated significant therapeutic efficacy in treating viral hepatitis caused by HCV and HBV, respectively. In particular, the activation process of ProTide prodrugs tends to occur specifically in the liver due to the susceptibility of the ester bonds in the ProTide structures to cleavage by liver hydrolases and the resistance to pre-hepatic metabolism21,22. This strategy has also proven to be a powerful technology in the efficient intracellular delivery of various active molecules23. Most recently, a modular design platform for carboxypeptidase-targeting fluorescence probes was established based on ProTide chemistry (Fig. 1C)24. However, such a presumably liver-targeted approach has not yet been applied to the design of H2S donors and H2S DDCs.

This work presents a new class of H2S DDCs containing phosphoramidothioate, referred to as the thio-ProTide-based H2S DDCs (Fig. 1), designed by replacing the phosphoryl oxygen atom with a sulfur atom and the phenol group with functional molecules in the ProTide backbone. The current phosphorothioate-based donors25, 26, 27, such as GYY413728 and JK-129, exhibit distinct release responses to varying pH levels. Developing phosphorothioate-based donors with novel structures and activation mechanisms is imperative to achieve more precise controllability at the tissue, cellular, and subcellular levels. Notably, the novel H2S DDC enables hepatic delivery of an anti-fibrotic molecule while releasing H2S, in contrast to conventional ProTides that produce only a single inert phenol, demonstrating a potent effect against hepatic fibrosis. The generation of H2S was proven to occur via a reported donor JK-429 as an intermediate, which has not been previously employed in any H2S–donor hybrid designs. In contrast to the existing H2S donors that rely on basic groups to achieve lysosomal capture (Fig. 1D)30, the thio-ProTide strategy may undergo a targeting moiety-free mode. The potential of this DDC lies in its ability to advance H2S for synergistic therapeutic applications, and its expandable features will help to provide new design ideas for co-administration, diagnostic, and subcellular targeting studies involving H2S.

2. Results and discussion

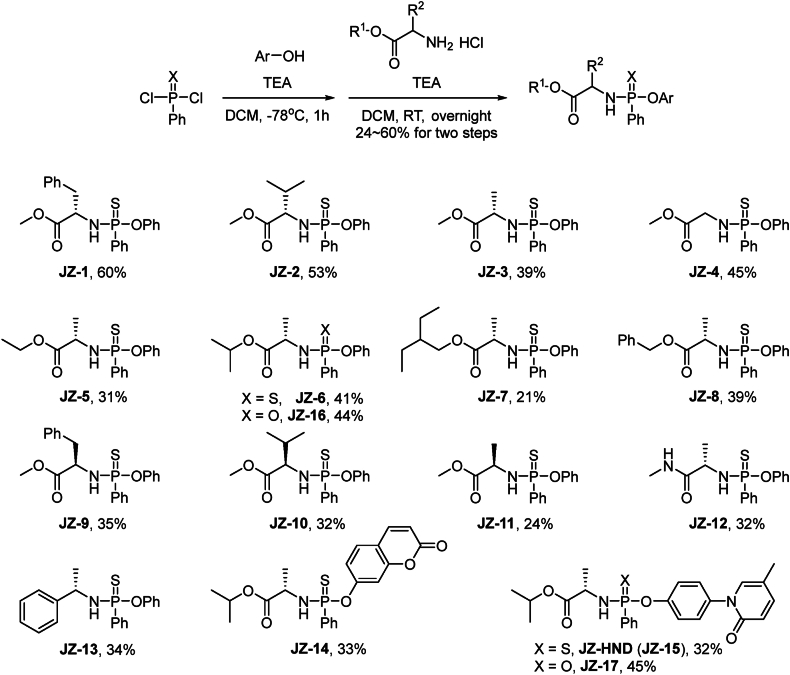

We designed fifteen H2S donors with different amino acid side chains and ester groups based on the ProTide prodrug structure. In brief, phenylthiophosphoryl dichloride was reacted with phenol and amino acid esters hydrochloride in sequence in the presence of triethylamine to obtain H2S donors JZ-1–JZ-13 with yields of 24%–60% (Scheme 1). Furthermore, we synthsized a donor called JZ-14 that contains a fluorophore to facilitate the determination of kinetic parameters during donor activation. We also designed a H2S DDC molecule JZ-HND (JZ-15), which carried hydronidone (HND), an antifibrotic drug candidate31,32, to explore the activity and mechanism of the synergistic donor–drug release pattern. Additionally, non-thio compounds JZ-16 and JZ-17 were synthesized as a control molecule. All compounds were fully characterized (Supporting Information Schemes S1–S7).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of H2S donors JZs and H2S donor–drug conjugate (DDC) JZ-HND.

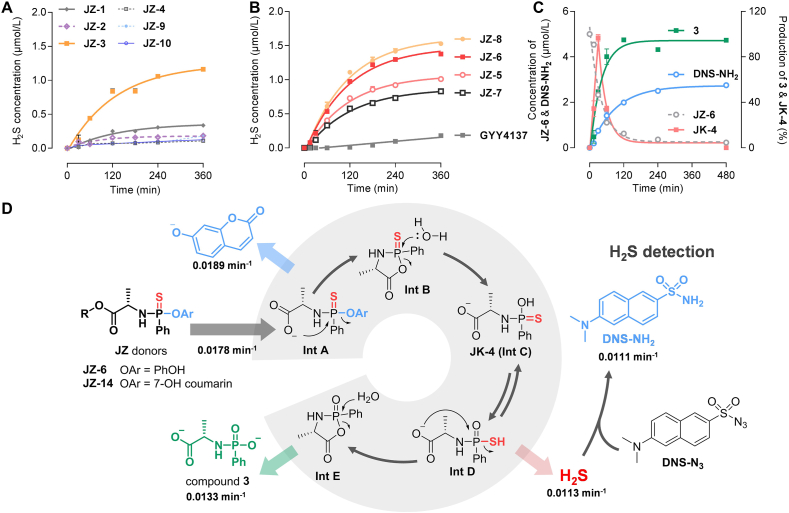

After preparing the H2S donors, we tested their H2S release properties in an enzymatic system. Carboxypeptidase Y (CPY) is a serine protease with high structural and functional similarity to human carboxypeptidase, which has been widely utilized in mechanistic studies of ProTide prodrugs33,34. CPY was employed for validating prodrug activation and screening the H2S release performance of donor JZs. On the other hand, the methylene blue method is commonly used for classical H2S detection, but it requires strong acidic conditions. However, the acidic environment may accelerate the degradation of the phosphorothioate and the cleavage of the P–N bond in the ProTide structure20,29. Therefore, it is recommended to select alternative H2S detection methods. The fluorescent probe DNS-N3 (Fig. 2D, Supporting Information Scheme S6)35, which has a sulfonyl azide structure, demonstrated exclusive sensitivity to H2S with excellent linear correlation (Supporting Information Fig. S1). As a result, this probe was chosen as a practical tool for the quantitative detection of H2S.

Figure 2.

H2S release and activation mechanism of JZ donors. (A, B) Enzyme-catalyzed H2S release. Reaction conditions: donors (5 μmol/L), CPY (60 ng/mL), DNS-N3 (10 μmol/L) in TBS (with 1% acetonitrile and 1% menthol, pH 7.4, 37 °C), followed by fluorescence intensity measurement (λex/λem = 325 nm/450 nm). H2S release from JZ-6: k = 0.0113 min−1, t1/2 = 61.6 min. (C) Generation of compound 3, JK-4 and DNS-NH2 after JZ-6 (5 μmol/L) activation by CPY (60 ng/mL) in TBS (with 1% menthol, pH 7.4, 37 °C), followed by LC–MS/MS quantification. Degradation of JZ-6: k = 0.0178 min−1, t1/2 = 38.9 min; generation of 3: k = 0.0133 min−1, t1/2 = 52.2 min; generation of DNS-NH2: k = 0.0111 min−1, t1/2 = 62.7 min. (D) Proposed mechanism of donor activation. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). The half-life is calculated from the equation, t1/2 = 0.693/k, where k (the rate constant) is obtained by curve fitting with a single-exponential function.

In the presence of CPY, the amount of H2S produced by the JZ donors (5 μmol/L) was determined (Fig. 2A and B). The results demonstrated an intriguing structure–activity relationship, most notably manifested in the influence of amino acid side chains. In comparison to the alanine backbone of JZ-3, the introduction of an overly large alkyl side chain at the α-position (JZ-1 with benzyl and JZ-2 with isopropyl) or an underly small one (JZ-4 without an α-alkyl side chain) resulted in a notable reduction in H2S production. The JZ-3 with methyl exhibited an H2S release of 1.16 μmol/L over 6 h (Fig. 2A). Comparison of JZ-1–JZ-3 and JZ-9–JZ-11 with the same α-alkyl group showed that the configuration of the α-alkyl group also had a significant effect on H2S release, with the amino acid as the natural L-configuration being more favorable for H2S release. Subsequently, the structure of the amino acid ester was also demonstrated to be a key factor influencing the H2S donation (Fig. 2B). JZ-6 and JZ-8 demonstrated superior performance, with H2S releases of 1.37 and 1.42 μmol/L, respectively, over 6 h. The results indicated that CPY has a precise mechanism for recognizing the steric conformation and size of the α-position and ester group of amino acids in the donors. This mechanism affects the activation of donors and the release of H2S. Furthermore, the release behavior of JZ-12 was inadequate, indicating that hydrolysis of the ester bond is a prerequisite for donor activation. JZ-13 exhibited minimal H2S release, suggesting that a phosphamide structure alone is insufficient for effective release. The phosphorothioate donor GYY4137 released a low amount of H2S at 6 h in the reaction system of this study, which may be attributed to the fact that this donor is characterized by slow H2S release.

The activation pathway of the donor was verified by following a series of steps. First, CPY cleaved the ester bond, generating a carboxylate anion that triggered the first nucleophilic addition–elimination reaction, resulting in the formation of phenol (Fig. 2D, Supporting Information Scheme S8). To gain a detailed understanding of this step, we designed a compound JZ-14 with a coumarin structure, which allowed us to describe the kinetic characteristics of this activation step by measuring changes in fluorescence intensity. Compound JZ-14 was synthesized by replacing the phenolic group with 7-hydroxycoumarin. The rate of fluorescence intensity increase was dependent on enzyme concentration, and a concentration of 60 ng/mL was selected for subsequent experiments (Supporting Information Fig. S2A). To distinguish between enzymatic degradation and non-enzymatic decomposition as the cause of donor release over time, a stability evaluation was also conducted using JZ-14. The study found that the stability of the donors was satisfactory in buffers without enzymes and even in simulated gastric and intestinal fluids (Fig. S2C).

The cyclic intermediate Int B (Fig. 2D) underwent hydrolysis to form a tautomeric pair (Int C/JK-4 and Int D). Subsequently, the pair then underwent a second nucleophilic addition–elimination reaction, releasing H2S and generating the final metabolic byproduct 3 via the cyclic intermediate Int E hydrolysis pathway. The process was investigated using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) (Fig. 2C). DNS-NH2 was considered a suitable quantitative mass spectrometry probe for monitoring H2S generation, which is the product of the reaction between H2S and the probe DNS-N3. Compound 3 was also synthesized for quantification. As illustrated in Fig. 2C, JZ-6 was rapidly degraded in the CPY-catalyzed reaction system, with a half-life of 38.9 min (k = 0.0178 min−1), which is nearly identical to the release of 7-hydroxycoumarin from JZ-7, as indicated by the observed rate constant (k = 0.0189 min−1, Fig. 2B). This suggested that the cyclization of Int A may coincide with the degradation of the donor. Furthermore, DNS-NH2 was detected in the reaction system, with a maximum concentration of 1.84 μmol/L and kinetic parameters (t1/2 = 63.1 min, k = 0.01098 min−1) consistent with the fluorescence response of H2S in Fig. 2A. The key H2S donor, JK-4, was detected in the reaction system as an intermediate, exhibiting a tendency to increase and then decrease (Supporting Information Scheme S9, Figs. S3 and S4). Compound 3 was also generated at a similar rate to the release of H2S. The above results demonstrated that the postulated enzymatic activation pathway for the donors is aligned with that for the ProTide prodrugs.

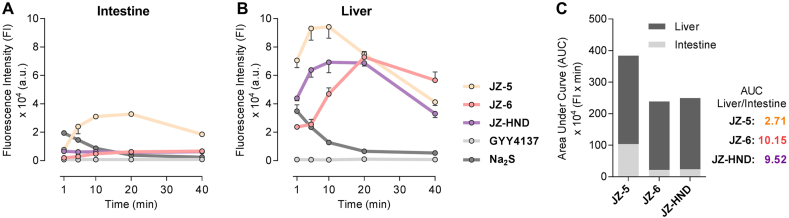

The yield of active metabolites in tissue homogenates reflects the efficiency of prodrug activation in target organs, which is crucial for assessing pharmacological activity and druggability. The degradation of JZ-6 and the production of metabolite 3 in the homogenates were verified using LC–MS/MS (Supporting Information Fig. S6). The H2S yields of donors JZ-3 and JZ-6 were measured in rat intestine and liver homogenates, as well as JZ-HND, a DDC derivative, and Na2S (bolus H2S) and GYY4137 (sustained-releasing H2S) were selected as control donors. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to determine the accumulation of H2S in the homogenate within 40 min, and it was found that these five donors exhibited distinct release behavior in homogenates. As depicted in Fig. 3, Na2S resulted in a rapid and short-lived release of H2S in both homogenates. The formation of H2S in the GYY4137 group was almost undetectable during the co-incubation time. In comparison to the control donors, the H2S production of JZ-3, JZ-6, and JZ-HND was biphasic and lasted longer (Fig. 3A and B). The release of H2S by JZ-3 was slightly higher in intestinal homogenates than in liver homogenates, with a liver/intestine AUC ratio of 2.71. The release behavior of JZ-HND is similar to that of JZ-6, with both releasing significantly less H2S than JZ-5 in intestinal homogenates. However, in liver homogenates, the yield of H2S is comparable to that of JZ-3. Consequently, JZ-6 and JZ-HND have a higher liver/intestine AUC ratio, reaching values of 10.15 and 9.52, respectively (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that JZ-6 and JZ-HND are promising for the specific release of H2S in hepatic tissues. The liver-targeting property of JZ-6 and JZ-HND may be attributed to the fact that they are structurally more susceptible to hydrolysis by carboxylesterase 1 (CES1), which is highly expressed in the liver and prefers to hydrolyze the ester substrates containing a small alcohol group and a bulky acyl group21,22,36,37. In the intestine, only CES2 is present and highly expressed, which tends to hydrolyze esters with a smaller acyl group36,37. Structurally, the JZs, including JZ-6 and JZ-HND, may not be ideal substrates for CES2. Furthermore, the isopropyl ester of JZ-6 is more favorable for intestinal metabolic resistance than the methyl ester of JZ-3. In conclusion, JZ-6 and JZ-HND displayed their potential for sufficient H2S release in the liver and resistance to first-pass elimination in the intestine, which may contribute to maintaining H2S homeostasis in the liver.

Figure 3.

Liver-specific H2S release of JZ-6 and JZ-HND. (A, B) H2S release from JZ-3, JZ-6, JZ-HND, GYY4137 and Na2S in the rat intestine homogenates (A) and liver homogenates (B). Donors (250 μmol/L) were incubated in homogenates (0.1 g/mL) in PBS (with 2.5% menthol, pH 7.4, 37 °C), then reacted with DNS-N3 (250 μmol/L), followed by fluorescence intensity measurement (λex/λem = 325/450 nm). Data represent the average ± SD (n = 3). (C) AUC ratio of the H2S levels of JZs in intestine and liver homogenates.

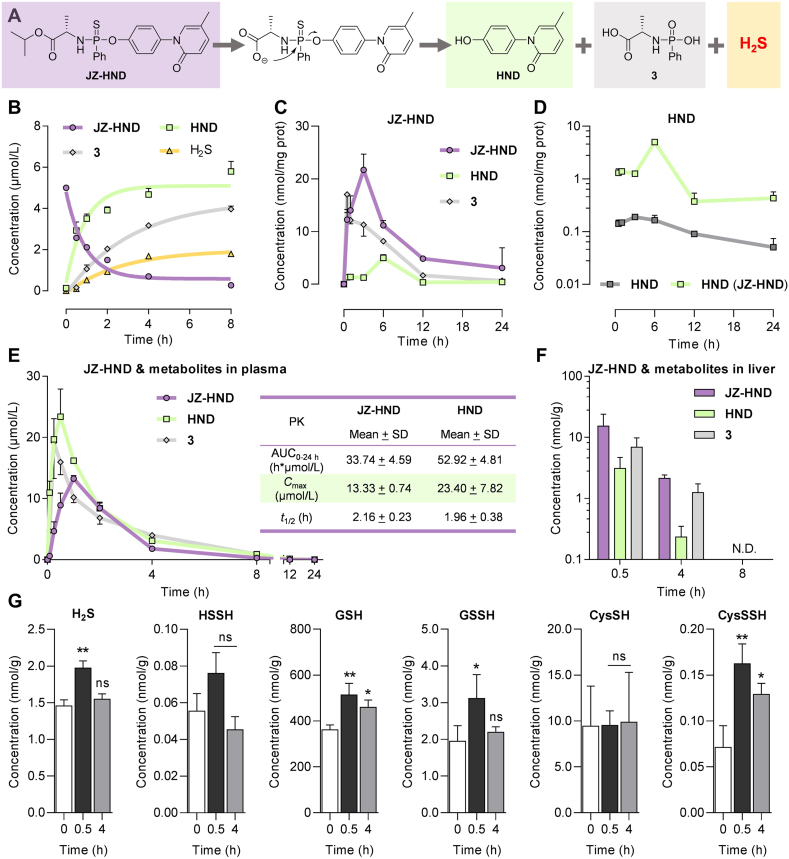

The intracellular pharmacokinetics are crucial for evaluating and optimizing drug efficacy38,39. In this study, we investigated the cellular metabolism of JZ-HND, which releases the active molecule HND, metabolite 3, and H2S when catalyzed by the intracellular hydrolases (Fig. 4A). The kinetic behavior of JZ-HND was characterized by quantifying HND and 3 using LC–MS/MS. Similar to JZ-6 (Fig. 2C), JZ-HND was gradually degraded and produced HND and 3 when catalyzed by recombined CPY (Fig. 4B). JZ-HND underwent a two-phase metabolic activation in HepG2 cells, accompanied by the generation of 3 and HND (Fig. 4C). HND is a promising drug candidate for treating liver fibrosis in the clinic. This study designed the first prodrug of HND and compared the intracellular generation of HND by JZ-HND with the intracellular uptake of HND after direct co-incubation with the cells. It was found that JZ-HND increased intracellular concentration of HND (Fig. 4D) by nearly 10-fold, indicating that thio-ProTide strategy could improve drug uptake and enhance its therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 4.

JZ-HND enables co-release of HND and H2S. (A) The release of HND from JZ-HND was accompanied by the production of H2S and 3. (B) Generation of HND, 3, and H2S after JZ-HND (5 μmol/L) activation by CPY (60 ng/mL) in TBS (with 1% menthol, pH 7.4, 37 °C), followed by LC–MS/MS quantification and H2S detection. Degradation of JZ-HND: k = 1.085 h−1, t1/2 = 38.3 min; generation of HND: k = 1.090 h−1, t1/2 = 38.2 min; generation of 3: k = 0.3133 h−1, t1/2 = 132.7 min; generation of H2S: k = 0.3748 h−1, t1/2 = 110.9 min. (C) Intracellular levels of JZ-HND, HND and 3 in HepG2 cells after continuous incubation with JZ-HND (50 μmol/L) for 24 h. (D) JZ-HND increases the intracellular exposure of HND. Intracellular levels of HND in HepG2 cells after continuous incubation with JZ-HND (50 μmol/L, green line) or HND (50 μmol/L, gray line) for 24 h. (E, F) In vivo Concentration−time profiles of JZ-HND and its metabolites in mice plasma (E) and livers (F) after oral administration of JZ-HND (1.0 mmol/kg). The table included a list of representative pharmacokinetic parameters. (G) Levels of H2S and related sulfur-containing species (HSSH, GSH, GSSH, CysSH, CysSSH) in liver tissue at different time points (0.5 and 4 h) after oral administration of JZ-HND (1.0 mmol/kg) or before administration (0 h). Data represent the average ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗P < 0.05 versus 0 h group; ns, not significant.

Subsequently, in vivo pharmacokinetic studies were conducted in mice. Following the oral administration of JZ-HND, the undegraded prodrug, the active metabolite HND, and its metabolic byproduct 3 were detected in plasma and liver tissue (Fig. 4E and F, Supporting Information Tables S6 and S7). The plasma half-lives of the prodrug and HND were determined to be 2.2 and 2.0 h, respectively. The maximum plasma concentrations of both were 13 and 23 μmol/L, respectively; the maximum intrahepatic concentrations appeared half an hour after administration, with values of 15 and 3 μmol/L, respectively; and the prodrug and metabolite were not detected in the liver after 8 h of administration.

To ensure accurate quantification of H2S production and endogenously formed persulfides in the mouse liver following the administration of JZ-HND, β-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl iodoacetamide (HPE-IAM) was selected as the trapping agent to promote the formation of S-alkylated derivatives of sulfur-containing species, which can indirectly reflect the amount of H2S and endogenous sulfur species, as well as their changes. Notably, H2S was also detected in the liver tissue, with the highest levels at half an hour and a significant increase compared to the pre-dose level (point 0) (Fig. 4G). The results indicate that the prodrug has the potential to facilitate the co-delivery of HND and H2S in the liver tissue. The formation of persulfides has been proposed to understand the cellular signaling mechanisms and the cytoprotective effects of H2S6,40,41. Therefore, our study further explored how an increase in intrahepatic H2S levels, as described above, would alter the composition of sulfur-containing species (Fig. 4G). The results showed that in parallel with H2S delivery, significant increases in the levels of glutathione (GSH), glutathione persulfide (GSSH), and cysteine persulfide (CysSSH) were observed at 0.5 h. In contrast, no significant change was observed in the levels of hydrogen persulfide (HSSH) and cysteine (CysSH).

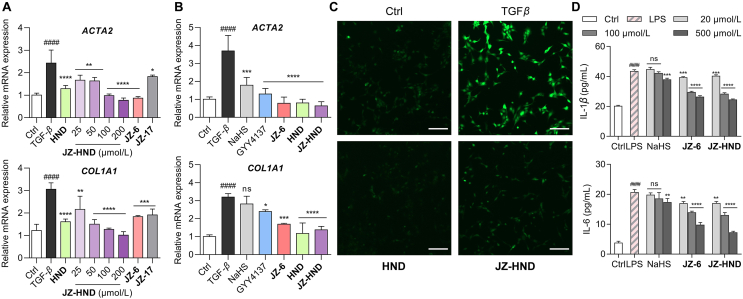

To investigate the bioactivities of JZ-HND, the antifibrotic effects on transforming growth factor (TGF-β1)-induced fibrosis in human hepatic stellate LX-2 cells were examined (Fig. 5A). The mRNA levels of ACTA2 and COL1A1, two representative markers of LX-2 cell activation, were significantly increased upon stimulation of LX-2 cells with TGF-β1. After treating cells with TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL) for 72 h, JZ-HND dose-dependently inhibited the mRNA expression of ACTA2 and COL1A1. Its activity was superior to that of the positive control HND. Moreover, both the H2S-only releasing donor JZ-6 and the HND-only releasing prodrug JZ-17 did not inhibit the expression of pro-fibrotic genes as much as JZ-HND, suggesting the possibility of a synergistic effect of the cascade-released HND and H2S. Notably, the thio-ProTide-based donors JZ-6 and JZ-HND showed more effective inhibition of the pro-fibrotic gene expression compared to the classical donors NaHS and GYY4137 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

JZ-HND and JZ-6 combined multiple protections at the cellular level, including antifibrosis, antioxidation, and inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. (A, B) JZ-HND attenuated TGFβ1-induced cellular fibrosis through the synergistic effect of H2S with HND. Relative ACTA2 and COL1A1 mRNA expression in LX-2 cells. Gene expression was normalized to ACTB mRNA levels. LX-2 cells were incubated with TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) and HND (200 μmol/L), JZ-HND (25, 50, 100, and 200 μmol/L), JZ-6 (200 μmol/L), JZ-10 (200 μmol/L), NaHS (200 μmol/L), or GYY4137 (200 μmol/L) for 72 h. (C) Reduction of ROS levels induced by TGF-β1 in LX-2 cells. Cells were treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL) and HND (100 μmol/L) or JZ-HND (100 μmol/L) for 24 h, then ROS were detected by fluorescence imaging using DCFH-DA (10 μmol/L); Scale bars = 200 μm. (D) Effects on LPS-induced IL-1β and IL-6 release in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of NaHS, JZ-6, or JZ-HND for 1 h prior to incubation with LPS (1 μg/mL). After incubation for 24 h, the levels of IL-1β and IL-6 present in the supernatants were measured using ELISA kits. Data represent mean ± SD of independent experiments (n = 3). ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗P < 0.05 versus model group and ####P < 0.0001 versus control group. ns, not significant.

Oxidative stress may contribute to the induction and persistence of TGF-β1 induced fibrosis42. The study illustrated that JZ-HND or HND significantly inhibited high levels of ROS induced by TGF-β1 in LX-2 cells (Fig. 5C). Additionally, we assessed the levels of two typical pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 (Fig. 5D) in mouse RAW264.7 macrophages. Significant elevation of IL-1β and IL-6 was observed in the culture media of LPS-stimulated cells. NaHS only showed a modest inhibitory effect on cytokine secretion in the high-concentration group (500 μmol/L). However, JZ-6 and JZ-HND exhibited significant inhibition of the cytokine secretion in a dose-dependent manner. These results suggest that JZ-HND, combining its two active metabolites, has therapeutic potential for alleviating liver injury due to its anti-fibrotic, anti-oxidative, and anti-inflammatory effects.

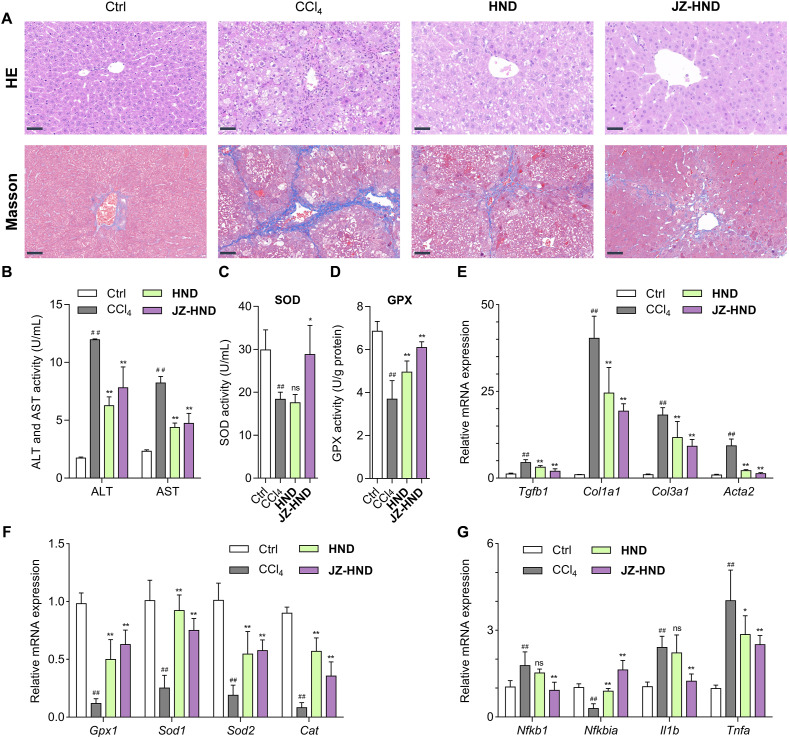

The liver protection effect of JZ-HND was investigated in vivo using a mouse liver injury model induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) (Fig. 6), following the confirmation of its versatile effects in cells. The mice received intraperitoneal injections of 20% CCl4 (10 mL/kg, dissolved in soybean oil) three times per week for four weeks. CCl4-treated mice were subjected to JZ-HND (1 mmol/kg) or HND (1 mmol/kg) treatment by daily gavages. Microscopy analysis of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed that the model group exhibited hepatocyte damage induced by CCl4; however, treatment with JZ-HND and HND significantly reduced the CCl4-induced hepatic ballooning and inflammatory cell infiltration in the mouse livers (Fig. 6A, upper panel). In addition, Masson's trichrome staining demonstrated that JZ-HND and HND treatment significantly slowed collagen fiber accumulation in mice exposed to CCl4 (Fig. 6A, lower panel).

Figure 6.

JZ-HND attenuated CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. (A) Effects of JZ-HND and HND on histology of the liver were measured by H&E and Masson's trichrome staining. Scale bars = 50 μm. (B) Serum ALT and AST levels. (C) Serum SOD levels. (D) Glutathione peroxidase (GPX) activity in liver. (E–G) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the transcript levels of genes related to (E) fibrosis (Tgfb1, Col1a1, Col3a1, and Acta2), (F) oxidative stress (Gpx1, Sod1, Sod2, and Cat), and (G) inflammation (Nfkb1, Nfkbia, Il1b, and Tnfa). Gene expression was normalized to Actb mRNA levels. The mice were intraperitoneally injected with 20% CCl4 (10 mL/kg, dissolved in soybean oil) three times per week for 4 weeks. JZ-HND (1 mmol/kg) or HND (1 mmol/kg) were orally administered once a day for 4 weeks. Data represent mean ± SD of independent experiments (n = 6). ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗P < 0.05 versus CCl4 group, and ##P < 0.01 versus control group.

Next, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities were measured to indicate hepatocellular injury. The serum levels of ALT and AST were consistently lower in the JZ-HND-treated mice compared to the control group (Fig. 6B). The serum superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was significantly lower in the JZ-HND group than in the control and HND groups (Fig. 6C). The study found a significant increase in hepatic tissue glutathione peroxidase (GPX) activity in mice with JZ-HND and HND compared to the control group (Fig. 6D). Moreover, representative genes in liver were examined using quantitative real-time PCR assays. The treatment of JZ-HND and HND resulted in reversals of the increased gene levels of fibrotic markers (Tgfb1, Col1a1, Col3a1, and Acta2) (Fig. 6E). The model group exhibited reduced hepatic expression of genes (Gpx1, Sod1, Sod2, and Cat) that combat oxidative stress, while these genes rebounded in the JZ-HND and HND groups (Fig. 6F). Treatment with JZ-HND and HND strongly suppressed mRNA levels related to the pro-inflammatory factor Nfkb1 and cytokines Il1b and Tnfa, while increasing the levels of Nfkbia (Fig. 6G). Collectively, both in vitro and in vivo findings indicate that JZ-HND treatment protects mice from hepatic injury induced by CCl4 and may be a superior candidate over HND in multiple aspects of anti-fibrosis, anti-oxidation, and anti-inflammation.

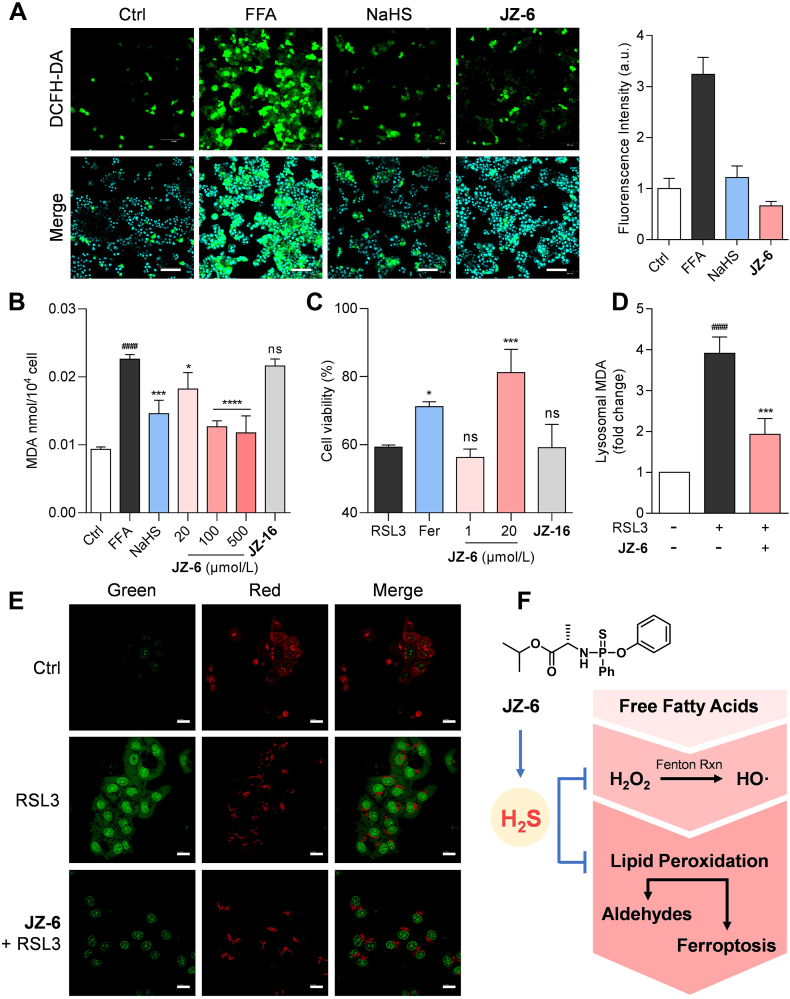

The therapeutic advantage of H2S DDC JZ-HND is believed to stem from the thio-ProTide-driven release of extra H2S compared to HND. Therefore, we explored the potential mechanisms involved in the hepatoprotective effects of H2S. The primary cause of liver injury induced by CCl4 is lipid peroxidation (LPO) initiated by its hepatic free radical metabolites43. Moreover, LPO caused by viral infections or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a central culprit in the process of hepatic fibrosis44,45. Thus, we utilized the donor JZ-6 as a probe molecule to examine the reduction of LPO by H2S (Fig. 7). To establish an in vitro model of LPO, we exposed HepG2 cells to free fatty acids (FFA), including palmitate and oleate (Supporting Information Fig. S16). As illustrated in Fig. 7A, bright fluorescence signals were observed in HepG2 cells after FFA treatment, indicating an increase in intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are the main initiators of LPO. The preventive interventions of JZ-6 and NaHS strikingly reduced the cellular fluorescence signal, demonstrating their effectiveness in alleviating cellular ROS accumulation. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is the final product and representative biomarker of LPO46. The impact of H2S donors on MDA levels was assessed in HepG2 cells treated with FFA (Fig. 7B). The MDA levels in the model group exhibited a significant increase compared to the control group. The ROS aggregation was alleviated by high concentrations (500 μmol/L) of NaHS. Notably, lower concentrations of JZ-6 achieved a more complete depletion of MDA compared to NaHS. Cells were also treated with JZ-9, a phosphonate analog of JZ-6 that cannot release H2S due to the absence of the sulfur atom. At a high concentration of 500 μmol/L, it showed minimal positive activity. We believe that introducing sulfur atoms and the thio-ProTide-based H2S delivery are responsible for the scavenging of aldehydes.

Figure 7.

H2S donors JZ-6 mitigates cellular lipotoxicity. (A) JZ-6 attenuated the ROS accumulation induced by free fatty acids (FFA). Representative fluorescent images of ROS and quantitative analysis of DCFH-DA fluorescent probe. Fluorescence intensity depicted as a ratio compared to the control group; Scale bars = 100 μm. (B) Lipid peroxidation levels (MDA levels) of steatosis HepG2 cells pretreated with NaHS (500 μmol/L), JZ-6 (20, 100, and 500 μmol/L), JZ-8 (20, 100, and 500 μmol/L) and JZ-9 (500 μmol/L). (C) Inhibition of ferroptosis induced by RSL3 (4 μmol/L) in HepG2 cells. (D) Reduction of lysosomal MDA levels. (E) Determination of lysosomal membrane permeabilization in HepG2 cells with acridine orange staining. Scale bars = 20 μm. (F) Schematic diagram showing multidimensional protection against lipotoxicity of JZ-6. Data represent mean ± SD of independent experiments (n = 6). ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗P < 0.05 versus model group and ####P < 0.0001 versus control group. ns, not significant.

Excessive LPO leads to ferroptosis, a newly identified programmed cell death implicated in various diseases, including NAFLD and liver fibrosis47,48. RSL3 can increase LPO by inhibiting glutathione peroxidase (GPX4) activity, which in turn triggers ferroptosis49. In this study, we chose RSL3 as a potential inducer of cellular LPO in HepG2 cells (Fig. 7C)50. Treatment with ferrostatin-1 (Fer), a well-established ferroptosis inhibitor51, attenuated RSL3-induced cytotoxicity. JZ-6 at 20 μmol/L significantly improved the cell viability. Similarly, even high concentrations of JZ-9 were unable to counteract the cytotoxicity caused by RSL3. LPO also occurs in various types of organelle membranes52. In particular, ferroptosis-related organelle damage has received much attention53. We found that RSL3 treatment significantly increased MDA contents in lysosome-enriched fractions of HepG2 cells. Pre-administration of JZ-6 effectively reduced the lysosomal MDA levels (Fig. 7D). LPO is the major biochemical and metabolic event leading to plasma membrane damage53. Lysosomal LPO drives lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) and the subsequent lysosomal cell dysfunction54,55. Herein, the occurrence of LMP was investigated using acridine orange (AO) staining (Fig. 7E). AO accumulates in lysosomes, resulting in red fluorescence upon excitation. Leakage of AO from the lysosomes into the cytosol resulted in green fluorescence56. AO staining experiments revealed that normal HepG2 cells exhibited bright red fluorescence in lysosomes after staining. After pretreatment with RSL3 for 1 h, the lysosomal red fluorescence weakened, and the nucleus and cytoplasm showed extensive green fluorescence, indicating a significant change in lysosomal permeability. Treatment with JZ-6 resulted in a considerable regression of red fluorescence, indicating improved lysosomal integrity.

Excess free fatty acids (FFA) in the liver can lead to hepatic lipotoxicity57, primarily caused by the uncontrolled generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during mitochondrial and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation58. ROS, including hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and H2O2, are the grand initiators of LPO58. During the propagation of LPO, ROS attack the carbon–carbon double bonds of unsaturated fatty acids, leading to the formation of highly reactive aldehydes such as MDA. This process also triggers ferroptosis by disrupting cellular and subcellular membranes53. Our donor JZ-6 was shown to alleviate LPO-mediated lipotoxicity at both cellular and subcellular levels, restoring normal cellular function in a multidimensional manner (Fig. 7F).

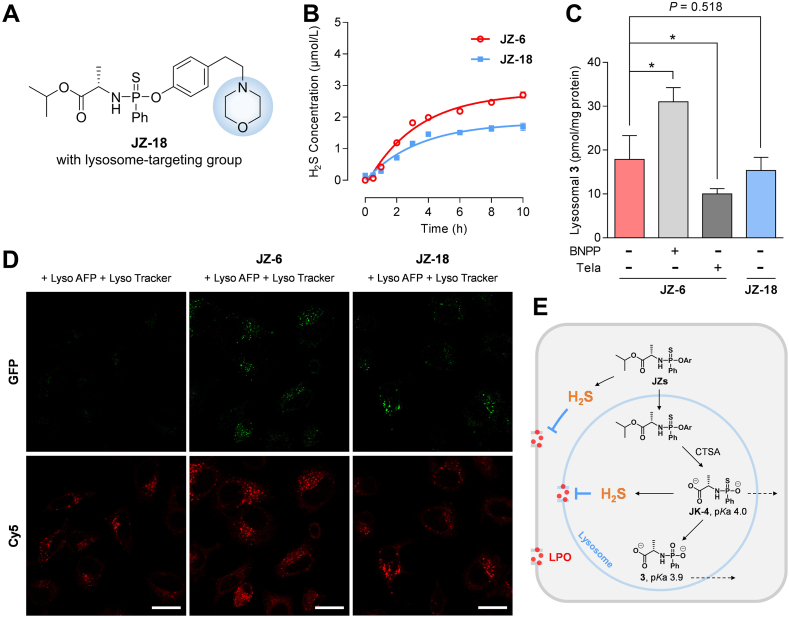

The protective role of our H2S donors at the subcellular level is noteworthy, encouraging a preliminary investigation of their lysosomal enrichment and potential mechanism from a cellular drug metabolism perspective in the present study (Fig. 8). Cathepsin A (CTSA) is a multifunctional serine protease that is primarily expressed in the liver, kidney, and lung. Its primary subcellular site of function is the lysosome59. CTSA exhibits significantly higher hydrolysis activity than other hydrolases responsible for the in vivo activation of ProTide prodrugs21,22,60. Therefore, CTSA-triggered donors are believed to be more inclined to achieve lysosomal targeting activation and subsellluarly precise H2S release. To test this hypothesis, we designed and synthesized the donor JZ-18 as a control compound, which contains a morpholine group, the conventional lysosome-targeting moiety (Fig. 8A). We investigated the H2S production of JZ-6 and JZ-18 under CTSA catalysis (Fig. 8B). The CTSA-promoted H2S release from JZ-6 was slower than the CPY-catalyzed reaction shown in Fig. 2A. We extended the incubation time to 10 h and the H2S yield of JZ-6 was approximately 55%. JZ-18 also released H2S, with a lower yield of approximately 37%. We also described the kinetic changes of DNS-NH2 generation and the degradation of JZ-6 or JZ-18 (5 μmol/L) by CTSA (250 ng/mL) in the reaction system using LC–MS/MS (Supporting Information Fig. S5). These findings suggested that modifying the phenolic structure of the donors preserved their H2S-releasing properties.

Figure 8.

JZ-6 achieves lysosomal delivery of H2S without the aid of a targeting moiety, due to its innate targeting. (A) Structure of JZ-18, an analog of JZ-6 with a lysosome-targeting moiety. (B) CTSA-catalyzed H2S release of JZ-6 and JZ-18. Reaction conditions: donors (5 μmol/L), CTSA (250 ng/mL), DNS-N3 (10 μmol/L) in TBS (with 1% acetonitrile and 1% menthol, pH 7.4, 37 °C), followed by fluorescence intensity measurement (λex/λem = 325/450 nm). H2S released from JZ-6: k = 0.3105 h−1, t1/2 = 2.2 h; from JZ-18: k = 0.2978 h−1, t1/2 = 2.3 h. (C) Effect of CES1 inhibitor BNPP, CTSA inhibitor telaprevir, and lysosome-targeting moiety on formation of compound 3 in lysosomes. HepG2 Cells were incubated with JZ-6 or JZ-18 (25 μmol/L), with or without the presence of BNPP (20 μmol/L) and telaprevir (5 μmol/L), and harvested at 6 h post-compound addition. Lysosomes were separated and the amount of compound 3 in lysosomes was determined. ∗P < 0.01 indicates statistically significant difference by ANOVA test. (D) Confocal images of lysosome-localized H–2S delivery in Hela cells. Endogenous H2S and lysosome-localized H–2S delivery from JZ-6 or JZ-18 in the presence of Lyso-AFP (10 μmol/L, λex = 488 nm, λem = 535 nm) and Lyso Tracker (50 nmol/L, λex = 577 nm, λem = 590 nm). Scale bars = 10 μm. (E) Schematic illustration of the lysosomal targeting mechanism. Data represent mean ± SD of independent experiments (n = 3).

Next, we compared the distribution of JZ-6 and JZ-18 within the lysosome in HepG2 cells. Compound 3, a metabolite shared by both donors, has a lower calculated pKa value of 3.9, which falls below the lysosome acidity window (with the pH range from 4.5 to 5.5). This suggests that 3 may exist as a negative ion upon generation and be restricted within the lysosome (Fig. 8E). Therefore, 3 was selected as a LC–MS/MS marker probing lysosomal distribution. To achieve lysosomal targeting of molecules, the introduction of targeting groups into the structure is a classical strategy. The most commonly used targeting groups are tertiary amine structures, such as N-alkylated morpholines. Surprisingly, the conversion of JZ-18 to 3 in lysosomes was even slightly lower than that of JZ-6 (P = 0.518) (Fig. 8C), suggesting that the morpholine moiety did not assist JZ-18 in achieving more effective lysosomal targeting. Furthermore, this indicated that JZ-6 could achieve lysosomal activation without reliance on classical lysosomal targeting moieties. We speculated that the lysosomal enrichment of JZ-6 is associated with lysosomal CTSA-mediated activation. Donors can be metabolized by cytosolic esterases and lysosomal CTSA. We treated cells with bis(p-nitrophenyl) phosphate (BNPP)61,62, an inhibitor of cytoplasmic carboxylesterase 1, and found an increase in lysosomal 3 (Fig. 8C). In contrast, after switching to telaprevir, a CTSA-specific inhibitor61,62, a significant decrease in detectable 3 in lysosomes was observed (Fig. 8C). The results suggest that CTSA is involved in the lysosomal enrichment of JZ-6. This lysosomal targeting depended on the ester moiety of the donor itself responding to the subcellular enzyme, rather than the targeting moiety redundantly modified to the donor.

To characterize the intracellular H2S production, we performed live-cell imaging of H2S using fluorescent probes in HeLa cells. Organelle-targeted probes, like Lyso-AFP, have proven to be more sensitive and practical for detecting cellular H2S production and localization30,63. We synthesized Lyso-AFP (Supporting Infromation Scheme S7) to analyze lysosomal H2S production and used the typical lysosomal marker dye, LysoTracker, for co-localization. In this study, NaHS (100 μmol/L) was used as a positive control, and a strong fluorescence signal was also observed that overlapped with the signal from LysoTracker (Supporting Information Figs. S14 and S15), demonstrating that Lyso-AFP is a viable probe for lysosomal H2S localization. Weak fluorescence was observed from endogenous H2S in Lyso-AFP-treated cells compared to cells without the probe (Fig. 8D and Fig. S14). The cells were pretreated with JZ-6 or JZ-18 (100 μmol/L) for 3 h, followed by incubation with LysoTracker (50 nmol/L) and Lyso-AFP (10 μmol/L) for 30 min. Bright fluorescence responses were observed after pretreatment with JZ-6 or JZ-18. The fluorescence signals from Lyso-AFP overlapped with those from LysoTracker with a high Pearson's coefficient (0.76 and 0.80, respectively) (Fig. 8D, Figs. S14 and S15). These results illustrated that introducing the thio-ProTide scaffold could enhance the lysosomal activation of donors and the subcellular H2S accumulation. Upon lysosomal entry, the thio-ProTide-based donor JZs are converted to the metabolic intermediate Int C (also known as JK-4, Fig. 2D) catalyzed by CTSA (Fig. 8E). It is noteworthy that JK-4 is a H2S donor reported by Xian's group29 inclined to release H2S to the greatest extent under weakly acidic conditions, which aligned with the lower pH of the lysosomal interior. On the other hand, JK-4, similar to compound 3, has a lower predicted pKa value (around 4.0), resulting in lysosomal restriction. These characteristics undoubtedly favor the lysosomal release of H2S. Of course, H2S tends to exist in lysosomes as a membrane-permeable formation, facilitating its membrane shuttling and slowing down the disintegration of membrane structures caused by LPO.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have confirmed that the thio-ProTide strategy has the potential to intervene in hepatic dysfunction through the combined release of pharmacologically active molecules and H2S, based on the observed intrahepatic release and lysosomal activation, as well as the mitigation of hepatic fibrosis and cellular/subcellular lipid peroxidation exhibited by the H2S DCC JZ-HND and the H2S donor JZ-6. The release of H2S from the thio-ProTide-based donors is spatially progressive, undergoing a “hepatic-cellular-lysosomal” cascade. In the future, the structural diversity of the thio-ProTides is worth being further enriched to achieve a more liver-specific release and confer more on-demand targeting properties. Introducing diverse ester and phenolic groups into the thio-ProTide backbone, which is synthetically easy, will facilitate continued optimization. To achieve lysosomal targeting design, excavating enzymes located in the lysosome for prodrug activation via ester hydrolysis is a promising alternative. Furthermore, to enhance the efficiency of H2S release and provide more diverse and appealing functions, it will achieved by introducing potentiating phenolic groups with additional pharmacological activities, targeting groups for tissue/organelle-specific delivery, or physicochemical property-improving moieties.

4. Experimental

4.1. General information

General experimental information is provided in the Supporting Information.

4.2. Synthesis

4.2.1. Synthesis of isopropyl ((4-(5-methyl-2-oxopyridin-1(2H)-yl)phenoxy) (phenyl)phosphorothioyl)-l-alaninate (JZ-HND)

1-(Benzyloxy)-4-bromobenzene (1578 mg, 6.0 mmol) and 5-methylpyridin-2-ol (545 mg, 5.0 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF (10 mL), to this solution was added anhydrous K2CO3 (1380 mg, 10 mmol) and CuI (190 mg, 0.10 mmol) under an Ar atmosphere. The reaction was stirred at 160 °C for 8 h. The reaction was diluted with 50 mL saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution then extracted by EA (100 mL × 3), the organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under vacuum. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography (PE/EA = 1:1) to afford the benzyl-protected HND (Bn-HND) as a white solid (958 mg, 65.8%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.57–7.26 (m, 9H), 7.15–7.07 (m, 2H), 6.40 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 5.17 (s, 2H), 2.04 (s, 3H).

Bn-HND (873 mg, 3 mmol) and 10% Pd/C (87.3 mg) were dissolved in THF, the reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight under H2 atmosphere. The reaciton was filtered with celite, and the reaction solution was concentrated under vacuum. The crude product was washed with EA to obtain HND as a white solid (4.92 g, 81.5%). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.38 (dd, J = 9.3, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.05–6.96 (m, 2H), 6.73–6.62 (m, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H).

Phenylphosphonothioic dichloride (422 mg, 2 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DCM (5 mL). To this solution was added HND (402 mg, 2 mmol) and TEA (304 μL, 2.2 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (2 mL) under an Ar atmosphere at −78 °C. The reaction was stirred at −78 °C for 1 h. l-Alanine isopropyl ester hydrochloride (334 mg, 2 mmol) and TEA (608 μL, 4.4 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (5 mL) was added subsequently. The reaction was stirred overnight at room temperature. The mixture was diluted with DCM (10 mL), washed with water (30 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under vacuum. The crude material was purified by flash chromatography (DCM/MeOH = 50:1) to afford the product JZ-HND as a yellow solid (300 mg, 32%). JZ-HND was a mixture of two inseparable diastereomers. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.08–7.95 (m, 2H), 7.61–7.47 (m, 3H), 7.35–7.27 (m, 4H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.12 (s, 1H), 6.64 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (m, 1H), 4.23–4.06 (m, 1H), 4.00 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 2.10 (s, 3H), 1.30 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.25–1.16 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 173.17 (dd), 160.94, 150.15 (dd), 143.57, 137.91 (d), 136.61, 135.93, 134.77, 132.40, 131.14 (d), 131.04 (d), 128.89 (t), 128.23, 122.73 (d), 122.31 (d), 120.68, 114.56, 68.46, 51.12 (d), 21.92 (d), 21.89 (d), 20.17 (dd), 16.80; 31P NMR (202 MHz, DMSO) δ 76.56, 74.59; HRMS (ESI) for C24H27N2NaO4PS [M+Na]+ Calcd. for 493.1321, Found 493.1327.

The synthesis and characterization data of other compounds including H2S donors, probes and relevant compounds are provided in the Supporting Information

4.3. Validation of H2S release by fluorescent probe

Enzyme-catalyzed: The solution of carboxypeptidase Y (CPY, C3888, Sigma–Aldrich) was prepared in deionized water (6 μg/mL) and the solution of recombinant human cathepsin A (CTSA, Cl11, Novoprotein, Suzhou, China) was prepared in deionized water (25 μg/mL). CTSA was activated with the method similar to that from a previous report64. 10 μL of the donor JZs solution (500 μmol/L in menthol) and 10 μL of probe DNS-N3 solution (1 mmol/L in acetonitrile) were added sequentially to a mixture containing 970 μL of TBS buffer (10 mmol/L, pH = 7.4) and 10 μL of enzyme solution. After incubation of the reaction solution for indicated time at 37 °C, 100 μL of reaction solution was transferred into black 96-well plate containing 100 μL of ACN (n = 3).

Released within tissue homogenates: Liver or intestine homogenates (0.1 g/mL) were prepared from Sprague–Dawley rats in PBS buffer (10 mmol/L, pH = 7.4). 25 μL of donor solution (500 μmol/L in methanol) was added to 975 μL of liver homogenates or intestine homogenates at 37 °C. After incubation for the indicated time (at 1, 10, 20, 30, and 40 min), 25 μL of reaction solution was mixed with 25 μL of probe DNS-N3 (1 mmol/L in acetonitrile) and vortexed for 5 min. The resulting mixed solution was diluted 100 times with ACN and added to a black 96-well plate. The Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) protein assay kit (P0012S, Beyotime, China) was used for the quantification of total protein in homogenates.

The fluorescence intensity was measured (Ex = 325 nm, Em = 450 nm) using a plate reader (BioTek SYNERGY-H1 multi-mode reader, Winooski, VT, USA). All experimental results were obtained by subtracting the background of the control group from the fluorescence values of the experimental group. The above assays were repeated in triplicate and reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three experiments. The results are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 8B.

4.4. H2S donor activation monitored by LC–MS/MS

The solition of probe DNS-N3, donor and enzymes were prepared as mentioned above. 20 μL of donor solution (final concentration = 5 μmol/L) and 20 μL of probe solution (final concentration = 10 μmol/L) were added into 1940 μL of TBS buffer (10 mmol/L, pH = 7.4) with 20 μL of CPY stock solution (60 ng/mL) or 10 μL of CTSA stock solution (125 ng/mL) at 37 °C. At 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h, 50 μL reaction solution was added into 200 μL ACN containing 200 ng/mL of 4-methylumbelliferone as internal standard. The mixture was centrifuged twice at 18,000 rpm (Biofuge Stratos, Thermo Scientific, Osterode, Germany) at 4 °C for 5 min to remove invisible impurities, and 80 μL of supernatant was used as sample for LC–MS/MS (Supporting Informaton Tables S1–S4, Figs. S7–S11). The concentration was calculated based on calibration curve. HPLC condition, MS condition, representative calibration curves, and other experimental information were provided in the Supporting Information This assay was repeated in triplicate and recorded as the mean ± SD (n = 3).

4.5. Cell culture

The immortalized human hepatic stellate cell line LX-2, HeLa cell lines and macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 was acquired from the Cell Bank of Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Hepatocarcinoma cell line HepG2 were provided by KeyGEN BioTECH (Nanjing, China). Cells were maintained in complete high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Genetimes Technology Inc., Shanghai, China) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) in an incubator containing 95% humidified air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. In LX-2 cell assay, a recombinant human TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL; Solarbio, Beijing, China) was added with compounds to the cell culture for 24 h for detection of fibrosis factors. All tested compounds showed no cytotoxicity to cells (Supporting Information Fig. S12).

4.6. Subcellular fractionation

Lysosomal fractionation was performed as described previously in our group with minor modifications65,66. Briefly, the cells were scraped, collected by centrifugation (600 × g, 5 min, 4 °C), and washed twice with ice-cold PBS. Break the cells with Dounce homogenizer and centrifuge the sample at 1000 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was transferred and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min to afford the crude lysosomal fraction (CLF). CLF was re-suspended in a OptiPrep™ density gradient medium solution. The solution was separated by density gradient centrifugation (100,000 × g for 1 h), and the top band was collected as the lysosome fractions.

4.7. Cellular pharmacokinetics

Cellular pharmacokinetics was performed as described previously in our group with minor modifications65,67. HepG2 cells were seeded in 6-well cell culture plates (2 × 105 cells/well) and grown to 90% confluence. The cells were treated with JZ-HND or HND at 37 °C for the designated time. Then, the medium was removed. The cells were washed with ice-cold PBS three times and lysed in cold 70% methanol solution. The mixture was vortexed for 5 min for more complete analyte abstract and protein precipitation, and then centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 5 min. An aliquot (100 μL) of the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, diluted with acetonitrile solution containing IS, and recentrifuged at 18,000 rpm before LC–MS/MS analysis (Section 4.4, Supporting Informaton Tables S1–S4, Fig. S13). Lysosomal uptake of compound 3 was determined in the presence or absence of inhibitors. The cells were treated with JZ-6 (25 μmol/L)/BNPP (20 μmol/L), JZ-6 (25 μmol/L)/talaprevir (5 μmol/L), JZ-6 (25 μmol/L) or JZ-11 (25 μmol/L) for 6 h. Then lysosomes were separated as mentioned above (Section 4.6). The fractions were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in cold 70% methanol solution. The mixture was vortexed for 5 min and centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 5 min. The aliquots were used to determine drug concentrations by LC–MS/MS. HPLC condition, MS condition, representative calibration curves, and other experimental information were provided in the Supporting Information Cellular and lysosomal accumulations were calibrated by protein content, which was determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, China). All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

4.8. Cell imaging

4.8.1. H2S release in cellular lysosome

HeLa cells were inoculated into 12-well plates and cultured overnight. Cells were co-incubated with 100 μmol/L of the donors at 37 °C for 3 h or NaHS (100 μmol/L) for 0.5 h, and washed with PBS buffer to remove extracellular donors. Cells were then co-incubated with the H2S-responsive fluorescent probe Lyso-AFP (10 μmol/L) dissolved in DMEM (with 0.1% pluronic F-127) and commercially available LysoTracker (50 nmol/L) dissolved in DMEM at 37 °C in the dark for 0.5 h and washed with PBS buffer. Cells were then co-incubated with Hoechst 33342 (1:1000 dilution) dissolved in DMEM for 10 min and washed with PBS buffer. Intracellular fluorescence in cells was monitored using a confocal laser scanning microscope (OLYMPUS FV300). Ex/Em: 346 nm/460 nm for Hoechst 33342. Ex/Em: 488 nm/535 nm for Lyso-AFP. Ex/Em: 577 nm/590 nm for LysoTracker.

4.8.2. Acridine orange (AO) staining

HepG2 cells were seeded in a laser confocal dish and pretreated with JZ-6 (50 μmol/L) with or without RSL3 (20 μmol/L) for 1 h. Then, the cells were incubated with AO (5 μg/mL, MCE HY-101879) for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. After washing, the cells were observed by a confocal laser scanning microscope OLYMPUS FV300 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). AO: Ex = 488 nm, Em1 = 530 nm (Green), Em2 = 640 nm (Red).

4.8.3. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection

ROS was detected using a ROS Assay Kit (R253; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). LX-2 or HepG2 cells were incubated in a 12-well plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and cultured overnight. In LX-2 cells, cells were co-treated with compounds (100 μmol/L) and TGF-β1 (10 ng/mL) for 24 h. In HepG2 cells, cells were pretreated with compounds (100 μmol/L) for 8 h before FFA solution (1 mmol/L) treatment for 24 h. The cells were then incubated with 10 μmol/L of DCFH-DA for 30 min and Hoechst 33342 (1:1000 diluted) for 10 min at 37 °C. The images were obtained with a fluorescence microscope (BioTek Lionheart FX, USA) using DIC for brightfield imaging and GFP filter cube for fluorescence imaging (Figure 5, Figure 7A). DCFH-DA: Ex = 488 nm, Em = 517 nm, Hoechst (33342): Ex = 346 nm, Em = 460 nm. The fluorescence intensity was analyzed from a series of images using Image J Software.

4.9. Gene expression analysis (qPCR assay)

Total RNA from LX-2 cells or liver tissue was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen), and 2 μg of total RNA was used for reverse transcription using the One Step TB Green™ PrimeScript™ RT-PCR Kit II (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using a SYBR Green Supermix kit (Takara). Reactions were performed in triplicate for each sample. Relative expression was normalized to the expression levels of beta-actin. The primer sequences were discribed in Supporting Information Table S5.

4.10. Malondialdehyde (MDA) measurement

HepG2 cells were inoculated into 6-well plates at a density of 7 × 105 cells/well and cultured overnight. The cells were co-incubated with FFA (1 mmol/L) or plus JZ-6 (20, 100, and 500 μmol/L), JZ-9 (500 μmol/L), NaHS (500 μmol/L) for 24 h. For lysosomal MDA measurement, the cells were pretreated with RSL3 (1 μmol/L) for 2 h and then treated with culture medium or JZ-6 (100 μmol/L) for 24 h. The cell lysates or pelleted crude lysosomal fractions (lysed in 50 mmol/L Tris HCl (pH 8), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 3% glycerol) were collected. MDA was then measured according to the manufacture's recommended protocol using the Lipid Peroxidation (MDA) Assay Kit (Sigma–Aldrich). The fluorescence intensity at excitation/emission wavelengths of 532 nm/553 nm was measured on a microplate reader. The MDA concentration was normalized with cell counts. This assay was repeated in three independent experiments and recorded as the mean ± SD.

4.11. Ferroptosis rescue experiments

In the ferroptosis rescue experiments, HepG2 cells were inoculated into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well and cultured overnight. The cells were pretreated with RSL-3 (4 μmol/L) for 2 h and then treated with culture medium or JZ-6 (20 μmol/L), JZ-9 (20 μmol/L), and Fer-1 (1 μmol/L) for 24 h. 100 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and the cells were incubated for a further 2–4 h at 37 °C. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy H1 Hybrid Multi-Mode Reader, BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). The results are expressed as the percentage of cell viability (%) with respect to the control (medium-treated cells). This assay was repeated in three independent experiments and recorded as the mean ± SD.

4.12. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The RAW 264.7 cells were inoculated into 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well and cultured overnight. The cells were pretreated with JZ-6 (20, 100, and 500 μmol/L), JZ-HND (20, 100, and 500 μmol/L) or NaHS (20, 100, and 500 μmol/L) for 1 h before treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 1 μg/mL). Thereafter, the cell culture supernatant was collected. The concentrations of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in the cell culture supernatant were quantified using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Dakewe Biotech, China). This assay was repeated in three independent experiments and recorded as the mean ± SD.

4.13. Animal experiments

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (2024-07-058). Male BALB/c mice (Six-week-old) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Animal Technology Co., Ltd. Mice were housed in pathogen-free conditions in a temperature-controlled environment at 22–24 °C with a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle. The mice were randomly divided into 4 groups (n = 6 in each group) as follows: control group, CCl4-treated model group, JZ-HND group (1 mmol/kg), and HND group (1 mmol/kg). CCl4-treated mice were injected intraperitoneally with 20% CCl4 (10 mL/kg of body weight) diluted in soybean oil three times per week for 4 weeks. JZ-HND (1 mmol/kg) or HND (1 mmol/kg) were orally administered once a day for 4 weeks.

The liver tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution. The haematoxylin & eosin (HE) and Masson trichrome staining was performed on paraffin-embedded liver sections according to standard procedures. Histological images of section tissues were captured with a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) for morphological analysis and for visualizing collagen expression.

4.14. Enzymatic assays in tissues

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels were measured using commercial kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (BC555 for ALT, BC1565 for AST, and S104195 for SOD, Solarbio, Beijing, China).

Hepatic tissue glutathione peroxidase (GPX) activity were measured using commercial kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (BC1195, Solarbio, Beijing, China).

4.15. Animal pharmacokinetics

The BALB/c mice were fasted for 12 h without water before the animal pharmacokinetics experiment. The mice were randomly divided into 3 groups (n = 3 in each group), each group were intragastric administration with JZ-HND (1 mmol/kg, 0.5% CMC-Na).

Blood samples (approximately 60 μL) were collected from retro-orbital plexus under light isoflurane anesthesia such that the samples were obtained at eight time points post dose: 5, 15, 30 min and 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. Blood samples were collected at each time point into labeled microcentrifuge tubes containing sodium heparin as anticoagulant. Plasma was collected after centrifugation at 8000 rpm × 5 min (Biofuge Stratos, Thermo Scientific, Osterode, Germany). Stored below −40 °C until LC–MS/MS analysis.

Liver samples were collected at 0.5, 4, 8 h post dose. Liver samples were homogenized using PBS buffer containing 70% MeOH in a ratio of 10:1 buffer to liver, this portion of sample was used to analyses JZ-HND and its metabolites in liver. Liver sample were homogenized using HPE-IAM solution (20 mmol/L, in MeOH) in a ratio of 10:1 buffer to liver. This portion of sample was used to analyses the H2S and sulfur compound levels and the resulting homogenates were stored below −40 °C until LC–MS/MS analysis. Pharmacokinetic parameters of JZ-HND and HND in mice plasma were provided in Tables S6 and S7.

4.16. Detection of sulfur-containing species in mouse liver

HPE-IAM-based sulfur-containing derivatives were synthesized according reported methods (Supporting Information Scheme S10)68. The analytical method including HPLC condition, MS condition, representative calibration curves, and other experimental information were provided in the Supporting Information Tables S8, S9, and S10).

4.17. Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software) was used for statistical analysis. One-way ANOVA was used to test statistical significance between groups as appropriate; nonlinear regression was used to analyze drug disappearance curve; linear regression was used to analyze calibration curves. Pearson correlation coefficient analysis and intracellular fluorescence was used to evaluate the correlation by Image J. Data were expressed as mean ± SD where applicable.

Author contributions

Haowen Jin: Methodology, Writing - Original Draft. Jie Ma: Validation, Investigation. Bixin Xu: Methodology, Investigation. Sitao Xu: Methodology. Tianyu Hu: Methodology. Xin Jin: Methodology. Jiankun Wang: Formal analysis, Visualization. Guangji Wang: Resources, Funding acquisition. Le Zhen: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 82173686), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2021-I2M-5-011, China), Leading Technology Foundation Research Project of Jiangsu Province (BK20192005, China), and Outstanding Youth Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20200081, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2024.10.017.

Contributor Information

Guangji Wang, Email: guangjiwang@hotmail.com.

Le Zhen, Email: i_m_zhenle@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary information

The following is the Supporting Information to this article:

References

- 1.Cirino G., Szabo C., Papapetropoulos A. Physiological roles of hydrogen sulfide in mammalian cells, tissues, and organs. Physiol Rev. 2023;103:31–276. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao X., Ding L., Xie Z-z, Yang Y., Whiteman M., Moore P.K., et al. A review of hydrogen sulfide synthesis, metabolism, and measurement: is modulation of hydrogen sulfide a novel therapeutic for cancer?. Antioxid Redox Signaling. 2019;31:1–38. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu X., Xiao Y., Sun J., Ji B., Luo S., Wu B., et al. New possible silver lining for pancreatic cancer therapy: hydrogen sulfide and its donors. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:1148–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ono K., Akaike T., Sawa T., Kumagai Y., Wink D.A., Tantillo D.J., et al. Redox chemistry and chemical biology of H2S, hydropersulfides, and derived species: implications of their possible biological activity and utility. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;77:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahdinloo S., Kiaie S.H., Amiri A., Hemmati S., Valizadeh H., Zakeri-Milani P. Efficient drug and gene delivery to liver fibrosis: rationale, recent advances, and perspectives. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:1279–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filipovic M.R., Zivanovic J., Alvarez B., Banerjee R. Chemical biology of H2S signaling through persulfidation. Chem Rev. 2018;118:1253–1337. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace J.L., Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics: exploiting a unique but ubiquitous gasotransmitter. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:329–345. doi: 10.1038/nrd4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:917–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Y., Biggs T.D., Xian M. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) releasing agents: chemistry and biological applications. Chem Commun. 2014;50:11788–11805. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00968a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell C.R., Dillon K.M., Matson J.B. A review of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donors: chemistry and potential therapeutic applications. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;149:110–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Z.N., Zheng Y.Q., Wang B.H. Prodrugs of hydrogen sulfide and related sulfur species: recent development. Chin J Nat Med. 2020;18:296–307. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(20)30037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Y., Ji X., Ji K., Wang B. Hydrogen sulfide prodrugs—a review. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinreb R.N., Sforzolini B.S., Vittitow J., Liebmann J. Latanoprostene bunod 0.024% versus timolol maleate 0.5% in subjects with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension: the APOLLO study. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:965–973. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levinn C.M., Cerda M.M., Pluth M.D. Development and application of carbonyl sulfide-based donors for H2S delivery. Acc Chem Res. 2019;52:2723–2731. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wen S., Cao C., Ge J., Yang W., Wang Y., Mou Y. Research progress of H2S donors conjugate drugs based on ADTOH. Molecules. 2023;28:331. doi: 10.3390/molecules28010331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pradere U., Garnier-Amblard E.C., Coats S.J., Amblard F., Schinazi R.F. Synthesis of nucleoside phosphate and phosphonate prodrugs. Chem Rev. 2014;114:9154–9218. doi: 10.1021/cr5002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehellou Y., Rattan H.S., Balzarini J. The proTide prodrug technology: from the concept to the clinic. J Med Chem. 2018;61:2211–2226. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehellou Y., Balzarini J., McGuigan C. Aryloxy phosphoramidate triesters: a technology for delivering monophosphorylated nucleosides and sugars into cells. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:1779–1791. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sofia M.J., Bao D., Chang W., Du J., Nagarathnam D., Rachakonda S., et al. Discovery of a β-d-2′-deoxy-2′-α-fluoro-2′-β-C-methyluridine nucleotide prodrug (PSI-7977) for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7202–7218. doi: 10.1021/jm100863x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami E., Wang T., Park Y., Hao J., Lepist E.I., Babusis D., et al. Implications of efficient hepatic delivery by tenofovir alafenamide (GS-7340) for hepatitis B virus therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:3563–3569. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00128-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y., Sun S., Li J., Wang W., Zhu H.J. Cell-dependent activation of ProTide prodrugs and its implications in antiviral studies. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2023;6:1340–1346. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.3c00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray A.S., Fordyce M.W., Hitchcock M.J.M. Tenofovir alafenamide: a novel prodrug of tenofovir for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus. Antivir Res. 2016;125:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alanazi S., James E., Mehellou Y. The ProTide prodrug technology: where Next?. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2019;10:2–5. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuriki Y., Sogawa M., Komatsu T., Kawatani M., Fujioka H., Fujita K., et al. Modular design platform for activatable fluorescence probes targeting carboxypeptidases based on ProTide chemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;146:521–531. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nin D.S., Idres S.B., Song Z.J., Moore P.K., Deng L.W. Biological effects of morpholin-4-ium 4 methoxyphenyl (morpholino) phosphinodithioate and pther phosphorothioate-based hydrogen sulfide donors. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020;32:145–158. doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng W., Teo X.-Y., Novera W., Ramanujulu P.M., Liang D., Huang D., et al. Discovery of new H2S releasing phosphordithioates and 2,3-dihydro-2-phenyl-2-sulfanylenebenzo[d][1,3,2]oxazaphospholes with improved antiproliferative activity. J Med Chem. 2015;58:6456–6480. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park C.M., Zhao Y., Zhu Z., Pacheco A., Peng B., Devarie-Baez N.O., et al. Synthesis and evaluation of phosphorodithioate-based hydrogen sulfide donors. Mol Biosyst. 2013;9:2430–2434. doi: 10.1039/c3mb70145j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li L., Whiteman M., Guan Y.Y., Neo K.L., Cheng Y., Lee S.W., et al. Characterization of a novel, water-soluble hydrogen sulfide–releasing molecule (GYY4137): new insights into the biology of hydrogen sulfide. Circulation. 2008;117:2351–2360. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.753467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang J., Li Z., Organ C.L., Park C.M., Yang Ct, Pacheco A., et al. pH-controlled hydrogen sulfide release for myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:6336–6339. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert A.K., Pluth M.D. Subcellular delivery of hydrogen sulfide using small molecule donors impacts organelle stress. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144:17651–17660. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c07225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu X., Guo Y., Luo X., Shen Z., Sun Z., Shen B., et al. Hydronidone ameliorates liver fibrosis by inhibiting activation of hepatic stellate cells via Smad7-mediated degradation of TGFβRI. Liver Int. 2023;43:2523–2537. doi: 10.1111/liv.15715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai X., Liu X., Xie W., Ma A., Tan Y., Shang J., et al. Hydronidone for the treatment of liver fibrosis related to chronic hepatitis B: a phase 2 randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:1893–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slusarczyk M., Lopez M.H., Balzarini J., Mason M., Jiang W.G., Blagden S., et al. Application of ProTide technology to gemcitabine: a successful approach to overcome the key cancer resistance mechanisms leads to a new agent (NUC-1031) in clinical development. J Med Chem. 2014;57:1531–1542. doi: 10.1021/jm401853a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kadri H., Taher T.E., Xu Q., Sharif M., Ashby E., Bryan R.T., et al. Aryloxy diester phosphonamidate prodrugs of phosphoantigens (propagens) as potent activators of Vγ9/Vδ2 T-cell immune responses. J Med Chem. 2020;63:11258–11270. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng H., Cheng Y., Dai C., King A.L., Predmore B.L., Lefer D.J., et al. A fluorescent probe for fast and quantitative detection of hydrogen sulfide in blood. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9672–9675. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang D., Zou L., Jin Q., Hou J., Ge G., Yang L. Human carboxylesterases: a comprehensive review. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8:699–712. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laizure S.C., Herring V., Hu Z., Witbrodt K., Parker R.B. The role of human carboxylesterases in drug metabolism: have we overlooked their importance?. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33:210–222. doi: 10.1002/phar.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou F., Zhang J., Li P., Niu F., Wu X., Wang G., et al. Toward a new age of cellular pharmacokinetics in drug discovery. Drug Metab Rev. 2011;43:335–345. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.560607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J., Qiu Z., Zhang Y., Wang G., Hao H. Intracellular spatiotemporal metabolism in connection to target engagement. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2023;200 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2023.115024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimura H. Signalling by hydrogen sulfide and polysulfides via protein S-sulfuration. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:720–733. doi: 10.1111/bph.14579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lau N., Pluth M.D. Reactive sulfur species (RSS): persulfides, polysulfides, potential, and problems. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2019;49:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuchida T., Friedman S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Unsal V., Cicek M., Sabancilar I. Toxicity of carbon tetrachloride, free radicals and role of antioxidants. Rev Environ Health. 2021;36:279–295. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2020-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamane D., McGivern D.R., Wauthier E., Yi M., Madden V.J., Welsch C., et al. Regulation of the hepatitis C virus RNA replicase by endogenous lipid peroxidation. Nat Med. 2014;20:927–935. doi: 10.1038/nm.3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi J., Kim J.W., Zhou Z., Lim C.W., Kim B. Ferroptosis affects the progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis via the modulation of lipid peroxidation-mediated cell death in mice. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayala A., Munoz M.F., Argueelles S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cel Longevity. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/360438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu J., Wang Y., Jiang R., Xue R., Yin X., Wu M., et al. Ferroptosis in liver disease: new insights into disease mechanisms. Cel Death Discov. 2021;7:276. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00660-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo P., Liu D., Zhang Q., Yang F., Wong Y.K., Xia F., et al. Celastrol induces ferroptosis in activated HSCs to ameliorate hepatic fibrosis via targeting peroxiredoxins and HO-1. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:2300–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang W.S., SriRamaratnam R., Welsch M.E., Shimada K., Skouta R., Viswanathan V.S., et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Asperti M., Bellini S., Grillo E., Gryzik M., Cantamessa L., Ronca R., et al. H-ferritin suppression and pronounced mitochondrial respiration make hepatocellular carcinoma cells sensitive to RSL3-induced ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;169:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skouta R., Dixon S.J., Wang J., Dunn D.E., Orman M., Shimada K., et al. Ferrostatins inhibit oxidative lipid damage and cell death in diverse disease models. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4551–4556. doi: 10.1021/ja411006a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Krusenstiern A.N., Stockwell B.R. Determining the role of peroxidation of subcellular lipid membranes in ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2023;19:674–675. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-01250-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen X., Kang R., Kroemer G., Tang D. Organelle-specific regulation of ferroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:2843–2856. doi: 10.1038/s41418-021-00859-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang F., Gomez-Sintes R., Boya P. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cell death. Traffic. 2018;19:918–931. doi: 10.1111/tra.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhardwaj M., Lee J.J., Versace A.M., Harper S.L., Goldman A.R., Crissey M.A.S., et al. Lysosomal lipid peroxidation regulates tumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2023;133 doi: 10.1172/JCI164596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Denamur S., Tyteca D., Marchand-Brynaert J., Van Bambeke F., Tulkens P.M., Courtoy P.J., et al. Role of oxidative stress in lysosomal membrane permeabilization and apoptosis induced by gentamicin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1656–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geng Y., Faber K.N., de Meijer V.E., Blokzijl H., Moshage H. How does hepatic lipid accumulation lead to lipotoxicity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease?. Hepatol Int. 2021;15:21–35. doi: 10.1007/s12072-020-10121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arroyave-Ospina J.C., Wu Z., Geng Y., Moshage H. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: implications for prevention and therapy. Antioxidants. 2021;10:174. doi: 10.3390/antiox10020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Birkus G., Wang R., Liu X., Kutty N., MacArthur H., Cihlar T., et al. Cathepsin A is the major hydrolase catalyzing the intracellular hydrolysis of the antiretroviral nucleotide phosphonoamidate prodrugs GS-7340 and GS-9131. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:543–550. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00968-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J.P., Liu S.H., Shi J., Wang X.W., Xue Y.L., Zhu H.J. Tissue-specific proteomics analysis of anti-COVID-19 nucleoside and nucleotide prodrug-activating enzymes provides insights into the optimization of prodrug design and pharmacotherapy strategy. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:870–887. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.1c00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li R., Liclican A., Xu Y., Pitts J., Niu C., Zhang J., et al. Key metabolic enzymes involved in remdesivir activation in human lung cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00602-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li J., Liu S., Shi J., Zhu H.J. Activation of tenofovir alafenamide and sofosbuvir in the human lung and its implications in the development of nucleoside/nucleotide prodrugs for treating SARS-CoV-2 pulmonary infection. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:1656. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13101656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qiao Q., Zhao M., Lang H., Mao D., Cui J., Xu Z. A turn-on fluorescent probe for imaging lysosomal hydrogen sulfide in living cells. RSC Adv. 2014;4:25790–25794. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murakami E., Tolstykh T., Bao H., Niu C., Steuer H.M.M., Bao D., et al. Mechanism of activation of PSI-7851 and its diastereoisomer PSI-7977. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34337–34347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.161802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]