Abstract

Tumor microenvironment activatable therapeutic agents and their effective tumor accumulation are significant for selective tumor treatment. Herein, we provide an unadulterated nanomaterial combining the above advantages. We synthesize a perylene diimide (PDI) molecule substituted by glutamic acid (Glu), which can self-assemble into small spherical nanoparticles (PDI-SG) in aqueous solution. PDI-SG can not only be transformed into nanofibers at low pH conditions but also be reduced to PDI radical anion (PDI·‒), which exhibits strong near-infrared absorption and excellent photothermal performance. More importantly, PDI-SG can also be reduced to PDI·‒ in hypoxic tumors to ablate the tumors and minimize the damage to normal tissues. The morphological transformation from small nanoparticles to nanofibers makes for better tumor accumulation and retention. This work sheds light on the design of tumor microenvironment activatable therapeutics with precise structures for high-performance tumor therapy.

Key words: Perylene diimide, Morphological transformation, Radical anion, Hypoxia, Tumor-specific, Photothermal therapy, Nanofiber, Amino acid

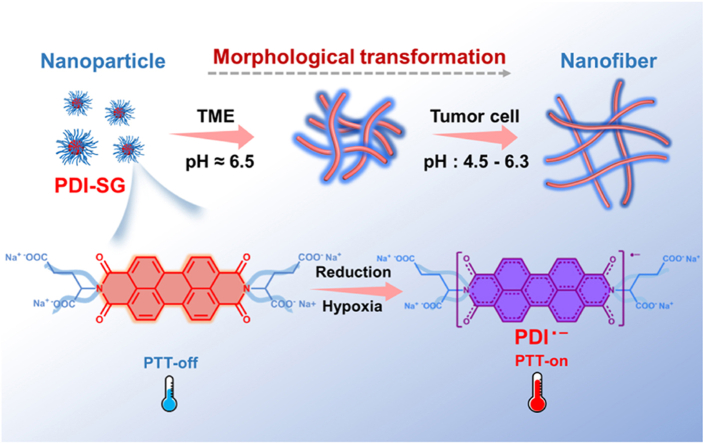

Graphical abstract

The morphological transformation and the hypoxia-induced generation of radical anions endow the glutamic acid functionalized perylene diimide with high photothermal therapeutic effect toward tumors.

1. Introduction

The research for safe and effective strategies to treat tumors remains a challenge. Hypoxia, reducibility, and low pH are important features of the tumor microenvironment (TME)1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. The complex TME may confine the therapeutic outcome of some tumor therapies but can also be employed to design tumor-specific drug delivery systems8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13. In addition, both the accumulation and retention ability of nanomaterials in tumor tissues play crucial roles in the therapeutic outcome and are closely connected with their dimensions and morphologies14,15. Small nanoparticles are conducive to rapid accumulation at the tumor sites but easily escape from the tumor tissues. In contrast, nanofibers can prolong the retention time due to the restriction on diffusion in tumor tissues16. Therefore, the development of responsive nanostructures with transformable morphology is a promising strategy17, 18, 19, 20, 21.

Photothermal therapy (PTT) as an emerging treatment for tumor ablation has many prominent advantages, such as low invasiveness, high specificity, and simple operation22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27. An ideal photothermal agent (PTA) should switch on the photothermal activity only in tumor tissues to eliminate the damage to normal tissues28,29. Relative to the most frequently used PTAs, radicals have been gradually developed for photothermal conversions30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36. Perylene diimides (PDIs), as a class of important organic fluorescent dyes, possess many beneficial features, such as high fluorescence intensity, excellent thermal stability, and easy functionalization37, 38, 39, 40. It has been reported that PDIs can be reduced by some reductants such as Na2S2O441,42 and KO243 to generate PDI radical anions. The near-infrared (NIR) absorption and the excellent photothermal conversion performance of PDI radical anions have attracted extensive attention from researchers42. However, most reported PDI radical anions were utilized to inhibit the growth of Escherichia coli because the facultative anaerobic bacteria can provide a highly reductive environment44, 45, 46, 47. Recently, the application scope of PDI radical anions as PTAs has been extended to ablation of solid tumors by Wang et al48. They have demonstrated that PDI supramolecules could also be reduced to PDI radical anions in the tumors.

In this work, a glutamic acid (Glu) functionalized PDI (PDI-Glu) was synthesized. PDI-SG can be obtained by self-assembly of PDI-Glu in the aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide and reduced to PDI radical anion (PDI·‒) by Na2S2O4. The introduced Glu not only optimizes the solubility of PDI but also interferes with the π–π stacking of PDI-Glu to maintain the stability of PDI·‒ as an isolating group44. Furthermore, PDI-SG can transform from spherical nanoparticles to short nanofibers in the TME and continue to grow into elongated nanofibers in tumor cells, which could achieve high tumor accumulation and long retention simultaneously (Scheme 1). PDI-SG can be reduced to PDI·‒ in hypoxic tumors but not in normal tissues. The hypoxia-induced PDI·‒ exhibits a potent photothermal effect, high specificity, and significant inhibition capability toward tumors.

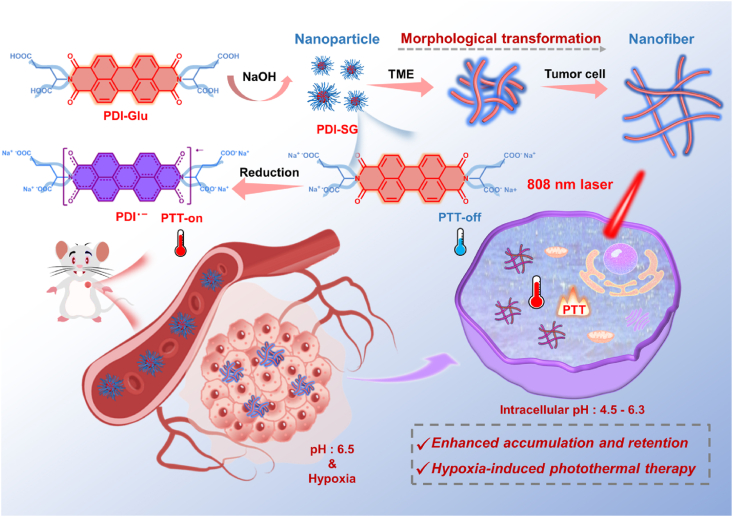

Scheme 1.

Schematic representation of the preparation and the morphological transformation of PDI-SG as well as the hypoxia-induced generation of PDI·‒ for tumor-specific PTT.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. EPR spectra of PDI-SG and PDI·‒

First, PDI-SG solution was added into an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) sample tube, and then the EPR signal of PDI-SG was characterized after the air inside the sample tube was replaced by inert gas. Na2S2O4 was added into the sample tube to obtain PDI·‒, and the concentration of Na2S2O4 was 10 times that of PDI-SG. After PDI-SG solution and Na2S2O4 were mixed for 30 min, the EPR signal of PDI·‒ was measured.

2.2. Morphological transformation of PDI-SG

PDI-SG solutions were diluted with water and buffer solutions at pH 6.5 and 5.0, respectively. The three solutions were left at room temperature for 12 h and then dripped onto silicon wafers, air-dried at room temperature, and observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

2.3. The photothermal effect of PDI·‒

PDI-SG can be easily reduced to PDI·‒ by Na2S2O4, and the concentration of Na2S2O4 is ten times that of PDI-SG. After PDI-SG solution and Na2S2O4 were mixed for 30 min, PDI·‒ from various concentrations (0.10–0.20 mmol/L) of PDI-SG solution was subjected to 808 nm laser irradiation. For PDI-SG at a fixed concentration of 0.15 mmol/L, the temperature of PDI·‒ under irradiation (0.8–1.2 W/cm2) was also recorded.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation and characterization of PDI-SG

PDI-Glu was synthesized in one step from perylene-3,4,9,10-tetracarboxylic acid dianhydride and l-Glu with the presence of imidazole (Scheme 2)49. The structure of PDI-Glu was validated by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Supporting Information Fig. S1). PDI-Glu can self-assemble in the aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide to obtain PDI-SG. First, the chirality of PDI-SG was studied by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S2, significant cotton effects of PDI-SG can be observed. As shown in Fig. 1A, PDI-Glu in N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) has three absorption peaks at 460, 490, and 525 nm. Compared with the absorption spectrum of PDI-Glu in DMF, that of PDI-SG in water exhibits an obvious red shift of about 10 nm, which might be due to the aggregation of molecules. What is unexpected is that PDI-SG in water displays enhanced fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1B). Meanwhile, the green fluorescence of PDI-Glu in DMF changes to the orange fluorescence of PDI-SG in water under the excitation of the same 365 nm light (inset in Fig. 1B). As shown in Supporting Information Figs. S3 and S4, the fluorescence spectra of PDI-SG differ substantially between the lower concentrations and the higher concentrations. The luminescence lifetime of PDI-SG in water (4.34 ns) is slightly longer than that of PDI-Glu in DMF (4.13 ns) (Fig. 1C). These results confirm the formation of nanoscale aggregates. The size distribution and stability of the PDI-SG were investigated. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S5, PDI-SG has a size of 63.5 nm and exhibits excellent stability in water and PBS.

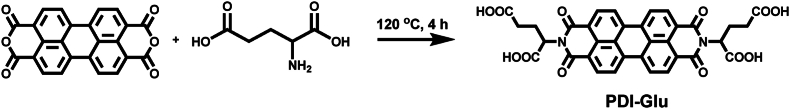

Scheme 2.

The synthetic route of PDI-Glu.

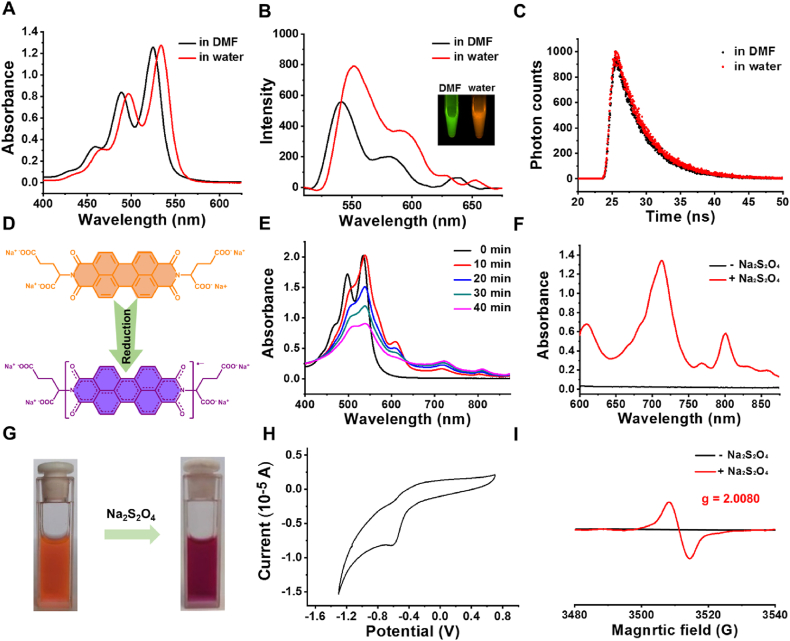

Figure 1.

(A) Absorption spectra of PDI-Glu (20 μmol/L) in DMF and PDI-SG (20 μmol/L) in water. (B) Fluorescence spectra and fluorescence images of PDI-Glu (1 μmol/L) in DMF and PDI-SG (1 μmol/L) in water. (C) Fluorescence lifetimes of PDI-Glu in DMF and PDI-SG in water. (D) Changes of the chemical structure of PDI-SG to PDI·‒. (E) Changes of the absorption spectra of PDI-SG after the addition of Na2S2O4 (20 μmol/L) for different times. (F) The amplified absorption spectra (600–900 nm) of PDI-SG before and after the addition of Na2S2O4 for 1 h. (G) Colour change of PDI-SG solution after the addition of Na2S2O4 under inert conditions. (H) CV of the aqueous solution of PDI-SG. (I) EPR spectra of PDI-SG before and after the addition of Na2S2O4.

3.2. Formation and characterization of PDI·‒

PDI-SG can be easily reduced to PDI·‒ by Na2S2O4 (Fig. 1D), and the formation of PDI·‒ is time- and Na2S2O4 concentration-dependent (Fig. 1E and Supporting Information Fig. S6). As shown in the absorption spectra in Fig. 1E and F, new absorption peaks appear at 609, 715, and 804 nm and exhibit increasing absorbance with the decrease of the absorbance of PDI-SG at 466, 497, and 534 nm. In a visual sense, the orange color of PDI-SG in water turned purple because of the generation of PDI·‒ (Fig. 1G). The purple color of the solution turned pink when exposed to the air due to the quenching of PDI·‒ by oxygen (Supporting Information Fig. S7). The fluorescence of PDI-SG was quenched when it was reduced to PDI·‒, but it was partially recovered when the solution was exposed to the air (Supporting Information Fig. S8). The zeta potentials of PDI-SG and PDI·‒ are −13 and −46.5 eV, respectively (Supporting Information Fig. S9). As shown in Fig. 1H, the reduction peak of PDI-SG assigned to the one-electron reduction process of PDI/PDI·‒ is −0.63 V in the cyclic voltammogram (CV). To directly prove that PDI-SG could be reduced to PDI·‒ by Na2S2O4, EPR spectroscopy of PDI-SG before and after the addition of Na2S2O4 was studied. As shown in Fig. 1I, the EPR signal of PDI-SG after reduction was observed with a g-factor of 2.0080, suggesting the formation of PDI·‒. To our delight, the absorbance of PDI·‒ at 808 nm remained almost unchanged after storage at 37 °C for 6 h, which demonstrated that PDI·‒ was highly stable under inert conditions (Supporting Information Fig. S10).

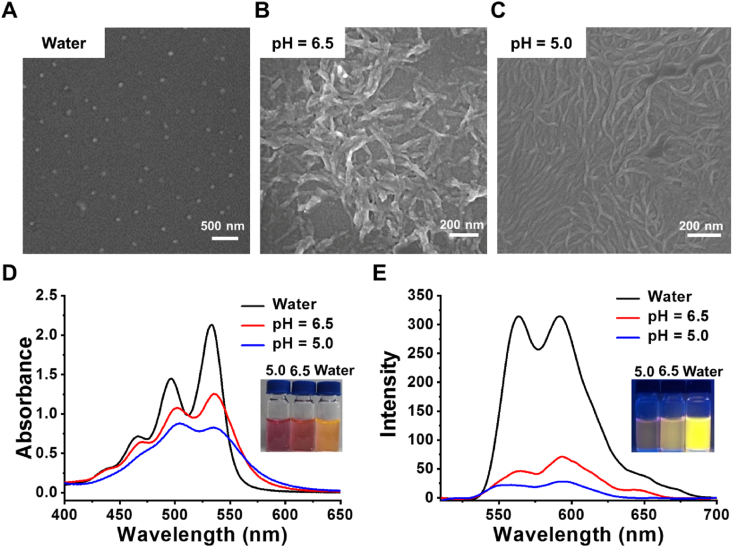

3.3. Morphological transformation of PDI-SG

Both TME and tumor cells have an acidic environment, and the pH of the lysosomes is lower than the extracellular pH of tumor cells. The acidic environment of TME and lysosomes was simulated by using buffer solutions to investigate the pH-triggered morphological transformations of PDI-SG. As observed in Fig. 2A, SEM results show that PDI-SG exists in the form of small spherical nanoparticles with sizes of around 60 nm, which is beneficial to the accumulation of tumors. The spherical nanoparticles can transform into short nanofibers at pH 6.5 (Fig. 2B) and continue to grow into elongated nanofibers at pH 5.0 (Fig. 2C). This transition will prolong the retention time of PDI-SG in the tumors. UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy was also utilized to examine the aggregation behaviors of PDI-SG under acidic conditions. As shown in Fig. 2D, PDI-SG possesses characteristic absorption peaks at 534 and 497 nm, which are put down to the 0 → 0 and 0 → 1 bands in the π → π∗ vibronic transition, respectively. The absorbance of the two characteristic peaks of PDI-SG decreased sharply at pH 6.5, and the value ratio of the two characteristic peaks (1.16) at pH 6.5 is lower than that of PDI-SG itself (1.47), which implies the occurrence of acid-induced morphological transformation behaviour45,50. The value ratio of the two characteristic peaks drops to 0.94 at pH 5.0, which indicates that the morphological transformation of PDI-SG is further enhanced by increased acidity. The sharply decreased fluorescence intensity of PDI-SG in Fig. 2E also confirms the changes in the aggregation states of fluorophores under acidic conditions.

Figure 2.

SEM images of PDI-SG (A) in water, at (B) pH 6.5 and (C) pH 5.0. (D) Absorption and (E) fluorescence spectra of PDI-SG under different conditions.

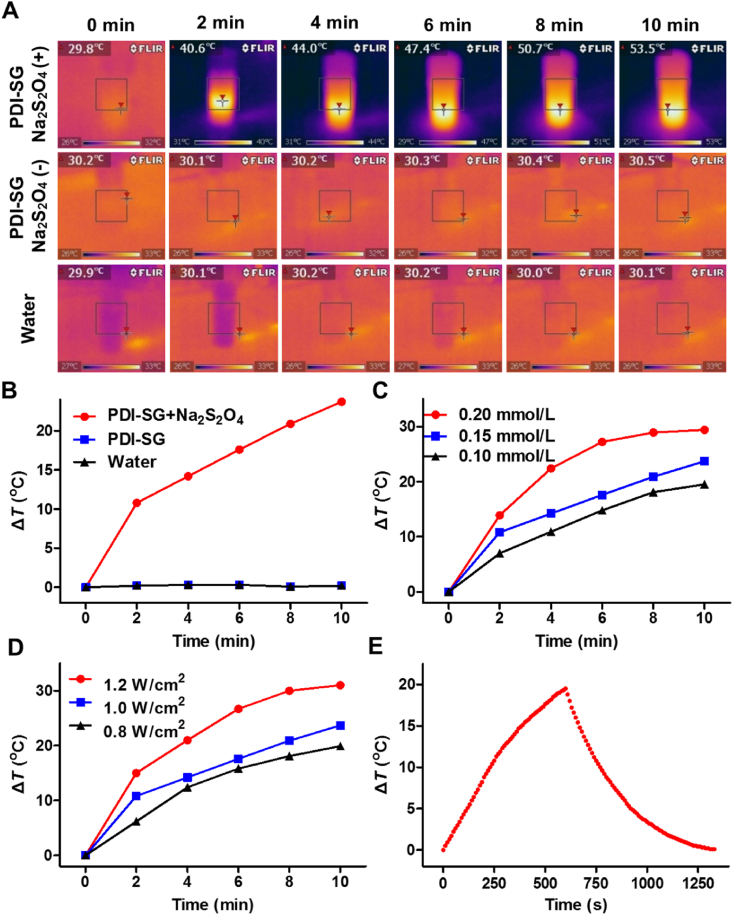

3.4. In vitro photothermal effect of PDI·‒

First, the PDI-SG solution (0.15 mmol/L) and that treated with Na2S2O4 were irradiated by an 808 nm laser. As observed in Fig. 3A and B, there is almost no temperature increase in the PDI-SG solution without Na2S2O4 or in water, while the temperature of the PDI-SG solution after the addition of Na2S2O4 substantially increases by 23.7 °C. When different concentrations of PDI-SG treated with Na2S2O4 are irradiated by an 808 nm laser, the temperature rises more rapidly with increasing concentrations of PDI-SG (Fig. 3C and Supporting Information Fig. S11). Similarly, PDI-SG at a constant concentration (0.15 mmol/L) was treated with Na2S2O4 and irradiation. The higher the laser power densities are, the higher the temperature can be reached (Fig. 3D and Supporting Information Fig. S12). The photothermal conversion efficiency of PDI·‒ was determined to be 20.1% (Fig. 3E and Supporting Information Fig. S13).

Figure 3.

(A) The infrared thermal images of PDI-SG treated with or without Na2S2O4 and water under irradiation (1.0 W/cm2). The interval between infrared thermal images was 2 min. (B) Photothermal heating curves of PDI·- from PDI-SG (0.15 mmol/L) under irradiation with water and PDI-SG as the references. Photothermal properties of (C) PDI·‒ from various concentrations (0.10–0.20 mmol/L) of PDI-SG subjected to irradiation (1.0 W/cm2) and (D) PDI·‒ from a fixed concentration of PDI-SG (0.15 mmol/L) under irradiation of varying laser power densities (0.8–1.2 W/cm2). (E) Photothermal heating curve of PDI·‒ from 0.10 mmol/L of PDI-SG under the irradiation followed by natural cooling.

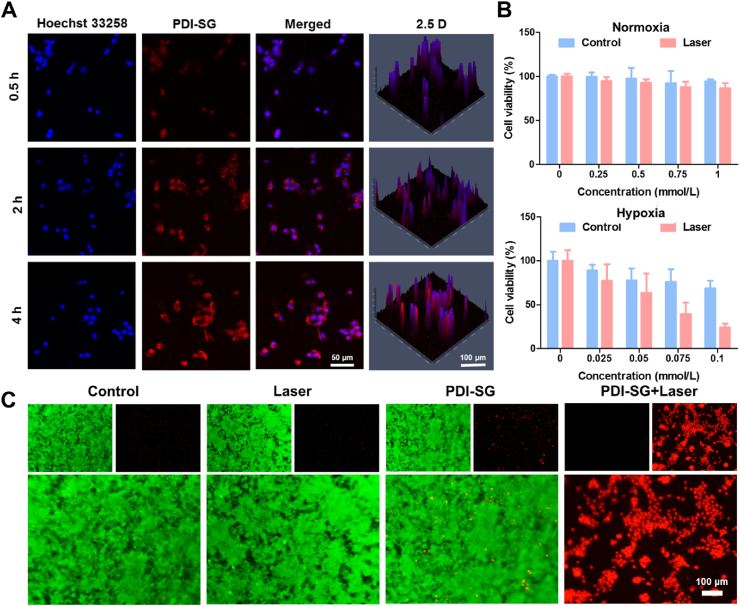

3.5. Internalization of PDI-SG and cytotoxicity of PDI·‒

To evaluate the photothermal antitumor effect of PDI·‒, the internalization of PDI-SG by mouse breast cancer (4T1) and human cervical carcinoma (HeLa) cells was first investigated. The enhancement of fluorescence intensity is time-dependent from 0.5 to 4 h in the confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images (Fig. 4A and Supporting Information Fig. S14). The efficient internalization of PDI-SG is a prerequisite for the PTT effect of PDI·‒.

Figure 4.

(A) CLSM images of 4T1 cells incubated with PDI-SG at 37 °C for 0.5, 2, and 4 h. (B) Cytotoxicity of PDI-SG toward 4T1 cells under normoxia and hypoxia conditions without or with irradiation (1.0 W/cm2, 10 min). (C) Live/dead staining assays of 4T1 cells incubated with PDI-SG or culture medium under hypoxic conditions with or without irradiation.

The cytotoxicity of PDI-SG toward 4T1 and HeLa cells was further studied through 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays. For 4T1 and HeLa cells in normoxia conditions, no apparent cytotoxicity was observed when the concentration of PDI-SG was up to 1 mmol/L (Fig. 4B and Supporting Information Fig. S15). However, PDI-SG exhibited a potent killing effect on tumor cells under hypoxia conditions at a low concentration of 0.1 mmol/L. At the same time, similar results were obtained from the bright field images of cells (Supporting Information Fig. S16). Under hypoxic conditions, the cells only treated with irradiation remained intact, but the morphologies of the cells incubated with increasing concentrations of PDI-SG were destroyed gradually after irradiation. Nearly all the cells were dead in spherical shapes when the concentration of PDI-SG reached 0.1 mmol/L. The PTT effect of PDI-SG after reduction was further demonstrated by live/dead cell-staining assays toward 4T1 and HeLa cells under hypoxic conditions. It is apparent that only the cells treated by PDI-SG with 808 nm laser irradiation under hypoxic conditions are in red fluorescence, and the proportion of the red fluorescence increases with the concentrations of PDI-SG (Fig. 4C and Supporting Information Fig. S17). However, the green fluorescence of live cells dominates the field of vision in the cells treated with only PDI-SG or irradiation (Fig. 4C and Fig. S17). Flow cytometry results (Supporting Information Fig. S18) show that the cells in the PDI-SG + Laser group die mainly through necrosis.

3.6. In vivo photothermal therapeutic effect of PDI·‒ after intratumoral injection

4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice were selected to study the production of PDI·‒ in the tumors. All experimental procedures were executed according to the protocols approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Approved No. 2022-0006). The robust fluorescence brightness of PDI-SG will be quenched when PDI-SG is reduced to PDI·‒. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S19, PDI-SG disperses throughout the tumor after intratumoral injection. The fluorescence signal of the tumor decreased sharply after 1 h of injection and completely disappeared 12 h later, which should be attributed to the generation of PDI·‒ and the morphological transformation of PDI-SG.

After intratumoral injection of PDI-SG for 2, 3, 4, and 5 h, the tumors were irradiated, respectively (Supporting Information Fig. S20). After the injection of PDI-SG for 4 h, the temperature increase of the tumors under laser irradiation reached the maximum (Supporting Information Fig. S21A). The temperature changes of the tumors indicate that PDI-SG could be reduced to PDI·– in the TME, and PDI·‒ has good photothermal performance in vivo. Therefore, 4 h post-injection should be selected as the optimum treatment time for the photothermal therapeutic experiments.

The normal tissues in the symmetrical positions of the tumors were subcutaneously injected with PDI-SG and irradiated after injection for 4 h. As shown in Fig. S21B, the temperatures of the normal tissues only increase by 3.7 °C, much lower than the temperature changes of the tumors (16.3 °C). These results demonstrate that PDI-SG could be reduced to PDI·‒ in the hypoxic TME but not in the normal tissues. The specificity of the hypoxia-induced photothermal properties prevents the normal tissues around the tumors from being damaged during irradiation.

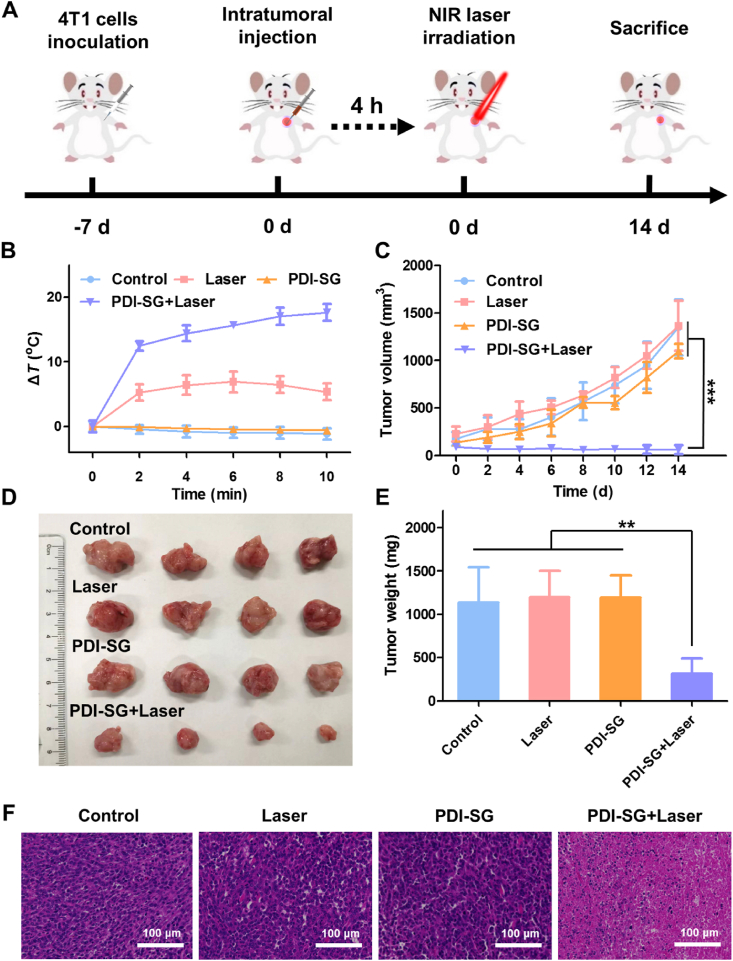

The 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice were randomly divided into four groups, including Control, Laser, PDI-SG, and PDI-SG + Laser. As illustrated in Fig. 5A, the mice in PDI-SG and PDI-SG + Laser groups were intratumorally administered with PDI-SG (1 mmol/L, 50 μL), and the mice in Laser and PDI-SG + Laser groups were irradiated after injection for 4 h. The temperature changes of the tumors in the PDI-SG + Laser group were superior compared with those in other groups, demonstrating the specific and excellent photothermal effect of PDI·‒ in vivo (Fig. 5B and Supporting Information Fig. S22). As described in Fig. 5C, remarkable tumor inhibition can be observed in the PDI-SG + Laser group. On the contrary, the tumor volumes of the mice in other groups are on the rise within 14 days, indicating that laser irradiation or PDI-SG alone negligibly inhibits tumor growth. 14 days after various treatments, the mice were sacrificed, and the tumors were excised and photographed. Compared with the other three groups, the mice in the PDI-SG + Laser group had the smallest tumors (Fig. 5D). A similar result can be obtained from the tumor weights (Fig. 5E). Thereafter, staining was also performed to study the tumors. Moreover, there is a prominent reduction of tumor cells in the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining image of the PDI-SG + Laser group (Fig. 5F), which further evidence that PDI-SG combined with 808 nm laser irradiation has a strong inhibitory effect on tumor cells. The body weights of the mice maintained stable throughout the PTT period (Supporting Information Fig. S23). Furthermore, the H&E staining images of the major organs (Supporting Information Fig. S24) and the results of the complete blood panels of the mice in the PDI-SG + Laser group (Supporting Information Fig. S25) show negligible differences from those in other groups, which proves that PDI-SG combined with 808 nm laser irradiation has no obvious systemic toxicity.

Figure 5.

(A) Schematic representation of the animal experiments for evaluation of the photothermal therapeutic effect of PDI·‒ after intratumoral injection. (B) Temperature changes of the tumor with different treatments versus time. (C) Changes in the average tumor volumes of the mice after different therapies. (D) Photos of the excised tumor. (E) Average weights of the tumor collected from the mice. (F) H&E staining of the tumor tissues from the mice sacrificed after 14 days post treatments. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 4). ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

3.7. In vivo photothermal therapeutic effect of PDI·‒ after intravenous injection

The photothermal performance of PDI-SG in vivo after intravenous injection was further studied. After PDI-SG was intravenously injected for 4, 6, 8, and 12 h, respectively, the increase of tumor temperatures after 808 nm laser irradiation was monitored. As displayed in Supporting Information Figs. S26 and S27A, the temperatures of the tumors after 6 h of injection reach a maximum after laser irradiation, indicating that the concentration of the generated PDI·‒ is the highest at that time. After 8 or 12 h, the temperature elevations are nearly the same, implying that PDI·‒ remains stable in the tumor regions.

The normal tissues on the opposite side of the tumors were also irradiated after intravenous injection of PDI-SG for 6 h to assess the biocompatibility of the intravenously injected PDI-SG during laser irradiation. As shown in Fig. S27B, normal tissues produce only negligible temperature changes compared to the tumors. That is, the photothermal activity of PDI-SG is turned off during blood circulation, and PDI·‒ is generated only in the tumors, which greatly enhances the safety of the PTA.

Inspired by the morphological transformation and the tumor-specific photothermal activity of PDI-SG, we explored the antitumor efficiency of PDI-SG after intravenous injection into the 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice (Fig. 6A). The tumors of the mice in Laser and PDI-SG + Laser groups were irradiated (0.8 W/cm2, 10 min) after intravenous administration of PDI-SG for 6 h. As illustrated in Fig. 6B, the temperatures of the tumor tissues of the mice in the PDI-SG + Laser group are much higher than those in the Laser group. Ultimately, the mice in the PDI-SG + Laser group had much smaller tumors than those in other groups (Fig. 6C and D), indicating that PDI-SG exerted excellent photothermal antitumor effect after being reduced to PDI·‒. The photograph and weighing of tumors further demonstrated the superior photothermal suppression effect of PDI-SG toward tumors under laser irradiation (Supporting Information Figs. S28 and S29). Moreover, the morphological transformation of PDI-SG in vivo was visually verified by bio-TEM. In the TEM images of the tumor slices of the PDI-SG-treated mouse after intravenous injection, nanofibers are distinctly observed inside the tumor cells (Fig. 6E), providing more convincing evidence for the advantage of PDI-SG in tumor treatment. During the whole treatment period, there were negligible changes in the body weights of the mice (Supporting Information Fig. S30). The haematological data of the mice in the treatment groups are similar to those in the control group (Supporting Information Fig. S31). In addition, the H&E staining results of tumors and major organs further demonstrate that PDI-SG exerts a potent photothermal effect only in the tumors without causing obvious systemic toxicity (Supporting Information Figs. S32 and S33). The biodistribution of PDI-SG in major organs was studied after the mice were intravenously injected with PDI-SG for 48 h. As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S34, relatively stronger fluorescence can be detected in the kidneys.

Figure 6.

(A) Schematic representation of the animal experiments for evaluation of the photothermal therapeutic effect of PDI·‒ after intravenous injection. (B) Temperature changes of the tumor with different treatments versus time. (C) Growth curves of the tumor volumes of each mouse. (D) Changes in the average tumor volumes. (E) TEM images of the tumor tissue slices of the mouse after intravenously injected with PDI-SG for 12 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5).∗∗∗P < 0.001.

4. Conclusions

In summary, an activatable PTA was developed for the selective treatment of tumors. The aggregates of the Glu-substituted PDI (PDI-SG) have been successfully obtained, and they could transform from spherical nanoparticles to nanofibers in the tumors for enhanced tumor retention. In addition, PDI-SG could be reduced to PDI·‒ with robust NIR absorption under hypoxic conditions. The hypoxia-induced PDI·‒ exhibits excellent PTT efficiency and biological safety toward the 4T1 tumor-bearing mice, and at the same time, it can minimize the damage to the normal tissues surrounding the tumors during laser irradiation. The construction of hypoxia-induced radical anions and morphologically transformable nanomaterials sheds light on the development of hypoxia-specific phototherapeutic agents for tumors or other diseases.

Author contributions

Hongyu Wang: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Dengyuan Hao: Methodology, Investigation. Qihang Wu: Methodology, Investigation. Tingting Sun: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Zhigang Xie: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52003267 and 51973214) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (YDZJ202101ZYTS027, China). We are grateful to Xueyanhui Scientific Research Platform for help in characterizing EPR.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2024.09.017.

Contributor Information

Tingting Sun, Email: suntt@ciac.ac.cn.

Zhigang Xie, Email: xiez@ciac.ac.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary information

The following is the Supporting data to this article:

References

- 1.Song L., Hao Y., Wang C.J., Han Y.K., Zhu Y.J., Feng L.Z., et al. Liposomal oxaliplatin prodrugs loaded with metformin potentiate immunotherapy for colourectal cancer. J Control Release. 2022;350:922–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y., Wang P.S., Shi R.H., Zhao Z., Xie A.J., Shen Y.H., et al. Design of the tumor microenvironment-multiresponsive nanoplatform for dual-targeting and photothermal imaging guided photothermal/photodynamic/chemodynamic cancer therapies with hypoxia improvement and GSH depletion. Chem Eng J. 2022;441 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Z.Y., Zhang Y.F., Dai X.X., Zhang W.Y., Foda M.F., Zhang J., et al. Selective thrombosis of tumor for enhanced hypoxia-activated prodrug therapy. Adv Mater. 2021;33 doi: 10.1002/adma.202104504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng P.L., Fan M., Liu H.F., Zhang Y.H., Dai X.Y., Li H., et al. Self-propelled and near-infrared-phototaxic photosynthetic bacteria as photothermal agents for hypoxia-targeted cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2021;15:1100–1110. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c08068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C., Cao F.J., Ruan Y.D., Jia X.D., Zhen W.Y., Jiang X.E. Specific generation of singlet oxygen through the Russell mechanism in hypoxic tumors and GSH depletion by Cu-TCPP nanosheets for cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58:9846–9850. doi: 10.1002/anie.201903981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L., Xiao Y., Yang Q.C., Yang L.L., Wan S.C., Wang S., et al. Staggered stacking covalent organic frameworks for boosting cancer immunotherapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan Y.C., Luan X.W., Zeng F., Wang X.Y., Qin S.R., Lu Q.L., et al. Logic-gated tumor-microenvironment nanoamplifier enables targeted delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 for multimodal cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14:975. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.09.016. 807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X.N., Zhao Q., Yang J.J., Wang T.X., Chen F.B., Zhang K. Tumor microenvironment-triggered intratumoral in-situ biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials for precise tumor diagnostics. Coord Chem Rev. 2023;484 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L.S., Sun J.W., Huang W.C., Zhang S.K., Deng X.L., Gao W.P. Hypoxia-triggered bioreduction of poly(n-oxide)–drug conjugates enhances tumor penetration and antitumor efficacy. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145:1707–1713. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao Y., Wang D.D., Luo B., Chen X., Yao Y.Z., Song C., et al. In-situ synthesis of melanin in tumor with engineered probiotics for hyperbaric oxygen-synergized photothermal immunotherapy. Nano Today. 2022;47 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang K.K., Yu G.C., Tian R., Zhou Z.J., Deng H.Z., Li L., et al. Oxygen-evolving manganese ferrite nanovesicles for hypoxia-responsive drug delivery and enhanced cancer chemoimmunotherapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;31 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z.C., Ding C.W., Sun T.D., Wang L., Chen C.X. Tumor therapy strategies based on microenvironment-specific responsive nanomaterials. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202300153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L.L., He S.S., Liu R., Xue Y., Quan Y., Shi R.Y., et al. A pH/ROS dual-responsive system for effective chemoimmunotherapy against melanoma via remodeling tumor immune microenvironment. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;14:2263–2280. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong Z.Y., Zhou B.L., Liu X.Y., Cao J.J., Hong Z.X., Wang J.Y., et al. Enzyme-induced transformable peptide nanocarriers with enhanced drug permeability and retention to improve tumor nanotherapy efficacy. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2021;13:55913–55927. doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c17917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun X.S., Xu X.X., Wang J., Zhang X.Y., Zhao Z.T., Liu X.C., et al. Acid-switchable nanoparticles induce self-adaptive aggregation for enhancing antitumor immunity of natural killer cells. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:3093–3105. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao J.J., Liu X.Y., Yuan X.M., Meng F.H., Sun X.Y., Xu L.Z., et al. Enzyme-induced morphological transformation of self-assembled peptide nanovehicles potentiates intratumoral aggregation and inhibits tumor immunosuppression. Chem Eng J. 2023;454 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia H.R., Zhu Y.X., Liu X., Pan G.Y., Gao G., Sun W., et al. Construction of dually responsive nanotransformers with nanosphere–nanofiber–nanosphere transition for overcoming the size paradox of anticancer nanodrugs. ACS Nano. 2019;13:11781–11792. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b05749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu L., Wang Y.T., Zhu C.Q., Ren S.J., Shao Y.R., Wu L., et al. Morphological transformation enhances tumor retention by regulating the self-assembly of doxorubicin–peptide conjugates. Theranostics. 2020;10:8162–8178. doi: 10.7150/thno.45088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng D.B., Zhang X.H., Gao Y.J., Ji L., Hou D., Wang Z., et al. Endogenous reactive oxygen species-triggered morphology transformation for enhanced cooperative interaction with mitochondria. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:7235–7239. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b07727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X.H., Cheng D.B., Ji L., An H.W., Wang D., Yang Z.X., et al. Photothermal-promoted morphology transformation in vivo monitored by photoacoustic imaging. Nano Lett. 2020;20:1286–1295. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b04752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun C., Wang Z.Y., Yang K.K., Yue L.D., Cheng Q., Ma Yl, et al. Polyamine-responsive morphological transformation of a supramolecular peptide for specific drug accumulation and retention in cancer cells. Small. 2021;17 doi: 10.1002/smll.202101139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang M.X., Zhang X., Chang Q., Zhang H.F., Zhang Z.B., Li K.L., et al. Tumor microenvironment–mediated NIR-I-to-NIR-II transformation of Au self-assembly for theranostics. Acta Biomater. 2023;168:606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2023.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang M.X., Xue F.F., An L., Wu D., Sha S., Huang G., et al. Photoacoustic-imaging-guided photothermal regulation of calcium influx for enhanced immunogenic cell death. Adv Funct Mater. 2024 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu D.D., Dai X.L., Zhang W., Zhu X.Y., Zha Z.B., Qian H.S., et al. Liquid exfoliation of ultrasmall zirconium carbide nanodots as a noninflammatory photothermal agent in the treatment of glioma. Biomaterials. 2023;292 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ge R.L., Yan P.N., Liu Y., Li Z.S., Shen S.Q., Yu Y. Recent advances and clinical potential of near infrared photothermal conversion materials for photothermal hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H.J., Xuan X.Y., Wang Y.P., Qi Z.J., Cao K.X., Tian Y.M., et al. In situ autophagy regulation in synergy with phototherapy for breast cancer treatment. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14:2317–2332. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Y.N., Yang L., Li M., Shu H.Z., Jia N., Gao Y.Z., et al. Anti-osteosarcoma trimodal synergistic therapy using NiFe-LDH and MXene nanocomposite for enhanced biocompatibility and efficacy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14:1329–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun B.B., Guo X.P., Feng M., Cao S.P., Yang H.W., Wu H.L., et al. Responsive peptide nanofibers with theranostic and prognostic capacity. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202208732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L., Wu Y., Yin X.B., Zhu Z., Rojalin T., Xiao W.W., et al. Tumor receptor-mediated in vivo modulation of the morphology, phototherapeutic properties, and pharmacokinetics of smart nanomaterials. ACS Nano. 2021;15:468–479. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c05065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y.G., Liu G.L., Tan P., Gu C., Li J.J., Liu X.Q., et al. Near-infrared light triggered release of ethane from a photothermal metal-organic framework. Chem Eng J. 2021;420 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lü B.Z., Chen Y.F., Li P.Y., Wang B., Müllen K., Yin M.Z. Stable radical anions generated from a porous perylenediimide metal-organic framework for boosting near-infrared photothermal conversion. Nat Commun. 2019;10:767. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08434-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Z.J., Zhou J.W., Zhang Y.H., Zhu W.Y., Li Y. Accessing highly efficient photothermal conversion with stable open-shell aromatic nitric acid radicals. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202113653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao J.Z., Jiang Y., He F.F., Jiang L.L., Zhu X.M., Ke H. Photo-induced organic radical species in naphthalenediimide-based metal-organic framework for reversible photochromism and near-infrared photothermal conversion. Mater Today Chem. 2023;27 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao H., Wu F., Zhao Y., Zhi X., Sun Y.F., Shen Z. Highly stable neutral corrole radical: amphoteric aromatic–antiaromatic switching and efficient photothermal conversion. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144:3458–3467. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c11716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang B.H., Li W.L., Chang Y.C., Yuan B., Wu Y.K., Zhang M.T., et al. A supramolecular radical dimer: high-efficiency NIR-II photothermal conversion and therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58:15526–15531. doi: 10.1002/anie.201910257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mi Z., Yang P., Wang R., Unruangsri J., Yang W.L., Wang C.C., et al. Stable radical cation-containing covalent organic frameworks exhibiting remarkable structure-enhanced photothermal conversion. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:14433–14442. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b07695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Würthner F., Saha-Möller C.R., Fimmel B., Ogi S., Leowanawat P., Schmidt D. Perylene bisimide dye assemblies as archetype functional supramolecular materials. Chem Rev. 2015;116:962–1052. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J., Li P.Y., Fan M.Y., Zheng X., Guan J., Yin M.Z. Chirality of perylene diimides: design strategies and applications. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202202532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Z.H., Wang X.J., Chen Q., Ma F.Y., Huang Y.W., Gao Y.J., et al. Regulating twisted skeleton to construct organ-specific perylene for intensive cancer chemotherapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60:16215–16223. doi: 10.1002/anie.202105607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Z., Fan W.P., Zou J.H., Tang W., Li L., He L.C., et al. Precision cancer theranostic platform by in situ polymerization in perylene diimide-hybridized hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:14687–14698. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b06086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H., Wenger O.S. Photophysics of perylene diimide dianions and their application in photoredox catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202110491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J.Q., Li F., Xu Z.W., Zang M.S., Liu S.D., Li T.H., et al. Bacteria-triggered radical anions amplifier of pillar[5]arene/perylene diimide nanosheets with highly selective antibacterial activity. Chem Eng J. 2022;444 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jalilov A.S., Nilewski L.G., Berka V., Zhang C.H., Yakovenko A.A., Wu G., et al. Perylene diimide as a precise graphene-like superoxide dismutase mimetic. ACS Nano. 2017;11:2024–2032. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b08211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Y.C., He P., Wang Y.X., Bai H.T., Wang S., Xu J.F., et al. Supramolecular radical anions triggered by bacteria in situ for selective photothermal therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:16239–16242. doi: 10.1002/anie.201708971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang F., Li R., Wei W., Ding X.W., Xu Z.Z., Wang P., et al. Water-soluble doubly-strapped isolated perylene diimide chromophore. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202202491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun J., Cai X.T., Wang C.J., Du K., Chen W.J., Feng F.D., et al. Cascade reactions by nitric oxide and hydrogen radical for anti-hypoxia photodynamic therapy using an activatable photosensitizer. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143:868–878. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c10517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang S.B., Liu X.H., Li B., Fan J.X., Ye J.J., Cheng H., et al. Bacteria-assisted selective photothermal therapy for precise tumor inhibition. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H., Xue K.F., Yang Y.C., Hu H., Xu J.F., Zhang X. In situ hypoxia-induced supramolecular perylene diimide radical anions in tumors for photothermal therapy with improved specificity. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144:2360–2367. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c13067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Araújo R.F., Silva C.J.R., Paiva M.C., Franco M.M., Proença M.F. Efficient dispersion of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in aqueous solution by non-covalent interaction with perylene bisimides. RSC Adv. 2013;3 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keum C., Hong J., Kim D., Lee S.Y., Kim H. Lysosome-instructed self-assembly of amino-acid-functionalized perylene diimide for multidrug-resistant cancer cells. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2021;13:14866–14874. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.